In 1808, the Catholic bishop John Milner (1752–1826) published An inquiry into certain vulgar opinions concerning the Catholic inhabitants and the antiquities of Ireland, in a series of letters from thence, addressed to a Protestant gentleman in England. This book takes the form of a travelogue, in which Milner pays special attention to the exemplary character and actions of the Irish Catholic clergy, describes the curriculum and progress of the seminary at Maynooth, and reflects on questions of Catholic doctrine, history, education, superstition and religious practices across the country. Milner's interest in architecture is evident throughout, and in a letter on that subject he wrote that he could hardly recollect half the places where he saw ‘new and elegant chapels, either built or in the act of building’.Footnote 1 He included a list of the Catholic places of worship that particularly struck his memory, including ‘Timolin, Castle Dermot, Tullow, Carlow, Thurles, Cashel, Cahir, Our Lady's at Cork, Carrick on Suire [sic], and St. Nicholas at Waterford’.Footnote 2 Milner was describing a wave of ambitious Catholic building enabled by the Catholic relief acts that had been instituted since the 1770s.Footnote 3

Prior to this, Catholic ‘penal chapels’ tended to be ‘simple structures built in the vernacular tradition without architectural pretensions’, with some more interior decoration introduced from the mid eighteenth century.Footnote 4 They were typically sited in unobtrusive locations. The chapel of St James in Grange, County Louth, dated c.1762, and the Tullyallen Mass House in County Tyrone, built in 1768, provide good rural examples.Footnote 5 There was considerable variation around the country, as Nuala Burke demonstrated in her work on the decorated interiors of Dublin chapels.Footnote 6 St Patrick's chapel in Waterford city, c.1740, reflects the desire of upwardly mobile urban Catholics to create a beautiful interior, but in a building which was largely concealed from public view in Jenkin's Lane.Footnote 7

Catholic architecture in Ireland had been restricted in several ways by the penal laws. Firstly, limitations on leasing and owning land meant that it was difficult to find sites on which to build and fiscally perilous to invest in buildings on sites with short-term leaseholds. While the legislative changes in 1778 allowing Catholics to hold longer leases on properties were particularly important in relation to building projects, legal restrictions remained in situ even throughout this period of increasing relief.Footnote 8 The 1782 act explicitly noted that any ‘popish ecclesiastic’ who officiated in a church or chapel with a steeple or bell would be exempt from the relief measures of that act.Footnote 9 The legal restriction was not on the building as such, but on the rights available to the priest associated with it. This act exemplifies the careful negotiation of toleration and visibility in the public sphere that Catholics had to contend with during the final decades of the eighteenth century. While many remaining legal disabilities were removed by subsequent acts, several restrictions remained in place, forming what has been described as a ‘maze of inconsistent legislation’.Footnote 10 Indeed, the passage of the Roman Catholic Relief Act, 1829 (10 George IV, c. 7), known as ‘Catholic emancipation’, introduced new several anti-Catholic restrictions, particularly in relation to the male religious orders.Footnote 11 In 1806, the Catholic archbishops of Dublin and Cashel shared a legal opinion that prohibitions remained on bells and steeples.Footnote 12 However, when in 1843 the Protestant Operative Association attempted to take a legal challenge against the bells of St Paul's Church on Arran Quay in Dublin, it was told that ‘a prosecution could not be maintained against a Roman Catholic clergyman for officiating in a chapel which has a steeple and bells’.Footnote 13 These restrictions, therefore, contributed to an atmosphere of legal uncertainty around building.

In 1812, the writer and lawyer Denys Scully (1773‒1830) highlighted the continuing restrictions on Catholic building, including the fact that Catholic clergy were legally barred from receiving ‘any endowment or public provision’ for either their own support or their houses of worship, and that charitable bequests of money were also subject to confiscation if they were considered to be supporting ‘superstitious’ institutions.Footnote 14 Despite this, such bequests and donations clearly did take place, particularly from Protestant landowners to their Catholic tenants, reflecting the distance between toleration as practised and the anti-Catholic letter of the law. Scully also highlighted the legal difficulty of members of the Catholic hierarchy taking leases, given that ‘the Law does not recognise the Catholic Bishops, or Priest, and his successors, as a body corporate, for any purpose whatsoever’.Footnote 15 Although ecclesiastical titles were commonly used in Ireland, it was against the law for a Catholic to assume the name, style or title of a bishop or archbishop associated with a specific diocese.Footnote 16 Scully also pointed to the financial burden of tithes on Catholics which meant that they first had to contribute to the Established Church before they could support their own.Footnote 17 This situation was changed by the Tithe Rentcharge (Ireland) Act of 1838, which made landowners rather than individual tenants liable for the charge and reduced the overall amount to be paid.Footnote 18 The buildings discussed in this article were designed and constructed in this environment of legal precarity and uncertainty, which persisted beyond 1829. During this period, Catholic places of worship were referred to as ‘chapels’, and this terminology is used throughout this article.Footnote 19

These new building projects in the era of Catholic relief can be broadly categorised into three types. The first type is the extended Mass house or ‘designed chapel’, typically on a T-shaped or cruciform plan, with one or more galleries, pointed windows, and some decorative elements inside such as plasterwork on the ceiling. The Ordnance Survey Memoirs include a number of measured drawings of these chapels, such as the Mayo chapel in Clonallan parish, County Down.Footnote 20 The parish church of the Blessed Sacrament in Golden, County Tipperary, is a good extant example of this first type, albeit with later additions.Footnote 21 The second type is the landlord chapel built as part of a planned or improved townscape, with investment in design evident as part of the creation of the broader architectural character of its environs. St Patrick's Chapel in Slane, County Meath, originally the ‘Mount Charles chapel’, provides a good, extant example.Footnote 22 The third type is the building of institutional expansion. These tended to be spear-headed by groups of parishioners together with members of the clergy and were more architecturally ambitious than the first type. The ‘Great Chapel’ at Waterford, now the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, is the most important example of this third type.Footnote 23 The ‘new and elegant chapels’ listed by Milner are mainly examples of this third type, with Timolin (Moone), County Kildare providing an interesting example of the first type.Footnote 24 There are overlapping characteristics across these three types — for example, the sites were often donated by a local (typically Protestant) landowner, and the building projects were funded by a combination of parish fundraising over time and larger individual donations.

While these chapels were major investments for their communities when first constructed, many of the chapels from this pre-emancipation wave of construction were replaced throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Of the first type, the buildings were very often extended if not entirely replaced over time. Important examples of the second type have also been lost — Francis Johnston's design for the Catholic chapel in Kells, County Meath was substantially extended by the late nineteenth century and rebuilt entirely in the 1960s.Footnote 25 The ‘Great Chapel’, later the Cathedral of the Assumption, at Thurles, County Tipperary, was entirely replaced by a grand Lombardic Romanesque building designed by James Joseph McCarthy in the 1860s.Footnote 26 Our Lady's at Cork, mentioned by Milner as his favourite due to its Gothic style, is now the Cathedral of St Mary and St Ann in Shandon, and was reworked following damage by fire in 1820, and then again substantially renovated in the 1960s and in the 1990s.Footnote 27

The patchy survival of Catholic buildings from this period is reflected in the scholarship on the topic, with relatively few detailed studies of the initial architectural developments prior to emancipation. The works of Seán Connolly and Dáire Keogh provide valuable political and social context for understanding architectural and spatial developments.Footnote 28 Important studies of the building culture of this period include David Fleming's analysis of Catholic places of worship in the eighteenth century and Christopher O'Dwyer's work on mid-eighteenth-century visitation records.Footnote 29 Nigel Yates and Finbar McCormick have both explored the liturgical arrangements in late-eighteenth-century chapels, and Kevin Whelan has considered Catholic social and economic developments, including architecture, in Munster during this period.Footnote 30 Individual buildings have also been the subject of local history studies, and community-led projects and conservation reports.Footnote 31 Brendan Grimes, Nuala Burke and Cormac Begadon have also explored the changing material contexts of Catholic worship during this period in Dublin, as well as a recent study of the Whitefriar Street church.Footnote 32 However, despite these studies, this period has been largely overshadowed by the sheer scale of Catholic building activity that commenced from the 1830s, by the impact of Pugin, and later by the expansion from 1860 onwards.Footnote 33 While there are relatively scant sources, and comparatively few surviving examples of this pre-emancipation period of building, it is nonetheless an important period of initial development and experimentation in relation to Catholic architecture in Ireland and the first phase of post-Reformation Catholic building in the public sphere.

This article aims to address this gap in the scholarship through a study of one of the buildings mentioned in Milner's list — the chapel, now parish church, of St John the Baptist on Friar Street in Cashel, County Tipperary (figure 1).Footnote 34 While it has been subject to some changes, it retains enough of its original footprint, interior fittings and structural form to provide a valuable example of this first wave of pre-1829 building. It is an example of the third type identified above — the architecture of institutional expansion. It also provides a valuable case study in regional Irish classicism at the end of the eighteenth century. In order to assess the significance of the building, it will be examined in terms of its site, architectural style and the social and political contexts for its construction. Close attention to one building allows for an exploration of the changing footprint of Catholic worship in Cashel, an urban landscape with many layers of ecclesiastical development and engagement.

Figure 1. Exterior of St John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church, Cashel. Author's photograph, 2022.

I

On 5 April 1794, a short notice was published in Finn's Leinster Journal to let the building community know that ‘proposals for building a chapel in Cashel will be received from different tradesmen, until 20th April next, by Rev. Doctor Cormac, Edmund Scully, and John Harrington, Esqs’.Footnote 35 This is a valuable reference to the commencement of the building work. A carved dedication at the entrance states that ‘Edmundus McCormack’ took care to build the church in 1795, perhaps reflecting the initial stages of work or the laying of a foundation stone. This new chapel represented a change in location for Catholic worship in Cashel. Prior to its construction, Catholic worship took place within or beside the medieval Dominican abbey in the town, located closer to St Patrick's Rock and its ensemble of medieval ecclesiastical buildings.

Thomas Campbell (1733–95), the writer, Church of Ireland clergyman and chancellor of St McCartin's Cathedral in Clogher, County Fermanagh, published a travelogue in 1777, which included an account of his visit to Cashel in 1775. Campbell's text took the form of a series of letters and paid close attention to the conditions of Catholic worship, which took place in a thatched chapel next to the abbey. He wrote that ‘you would be amazed, considering how thinly the country is inhabited, at the number of Romanists I saw on Sunday assembled together’.Footnote 36 He noted that ‘round the altar were several pictures, which, being at the distance of a very long nave of an old monastery, I went round to the door of one of the transepts, to see them more distinctly’. He described the way that ‘people made way for me, and some offered to conduct me to where the quality sat’, reflecting how clearly social status was spatially performed and made visible even in quite modest buildings.Footnote 37

Campbell also commented on the material culture of worship in this Catholic chapel. He wrote that candles burned on the altar and that ‘the priest was very decently habited, in vestments of party-coloured silk, with a large cross embroidered, on the outside a garment which hung down behind’.Footnote 38 The evidence in Campbell's 1777 text is supported by an earlier account of the conditions of Catholic worship in the diocese of Cashel recorded in the visitation books of Archbishop Butler I (1691–1774). As Christopher O'Dwyer has noted, these records provide a ‘picture of a church materially poor but well organised and improving’, with worship and education taking place in the same small, usually thatched buildings.Footnote 39 These had minimal furnishings, usually including an altar of deal boards with an altar stone, a crucifix or a painting of the crucifix and stone cisterns for holy water. Butler's visitations demonstrate his concern with the externals of religion, including proper vestments in liturgically correct colours, altar stones and cloths, chalices and altar plate.

Butler visited Cashel on 16 July 1759, which was then in the care of Rev. Timothy Fogarty. The visitation record notes the ‘chappel of Cassel is built at ye Dominican abby erected by ye sd pastor Tim Fogarty with assistance he got from ye naibouring gentlemen & parishioners & is in right good order’.Footnote 40 Butler was satisfied with the vestments, which are described in detail and are likely to be the same as those observed in use by Campbell some sixteen years later. These descriptions of the spaces used by Catholics in Cashel are useful when considering the construction of St John the Baptist, as they provide evidence of the fact that the chapel at the Dominican abbey had been relatively recently constructed, as well as valuable insight into the step-change that the new building represented for parishioners.

An album of newspaper cuttings compiled by Theobald Fitzwalter Butler in the late 1870s includes an article from the 1868 Cashel Gazette on the transition from the old to the new chapel. The article notes that the ‘old chapel’ was razed to the ground c.1798, by the then parish priest, the Very Rev. Edmond Cormac V.G.Footnote 41 Although this account was written seventy years after the events had taken place, the article was produced within living memory and is, therefore, a source for the emotions or perspectives that parishioners may have had at that time. Insufficient space was given as the reason for the demolition. However, this account noted: ‘The Rev. Mr. Cormac sought to impress upon his flock the necessity of building a larger one; but strange to say, they were alike deaf to persuasion and entreaty — nay, even strenuously opposed to the idea.’ Despite this opposition, the plan proceeded and, following the levelling of the ‘sacred edifice’, Cormac ‘improvised a barn on the Green, belonging to a man named Madden, to serve the purpose of a house of prayer, until the completion of the new one’.Footnote 42

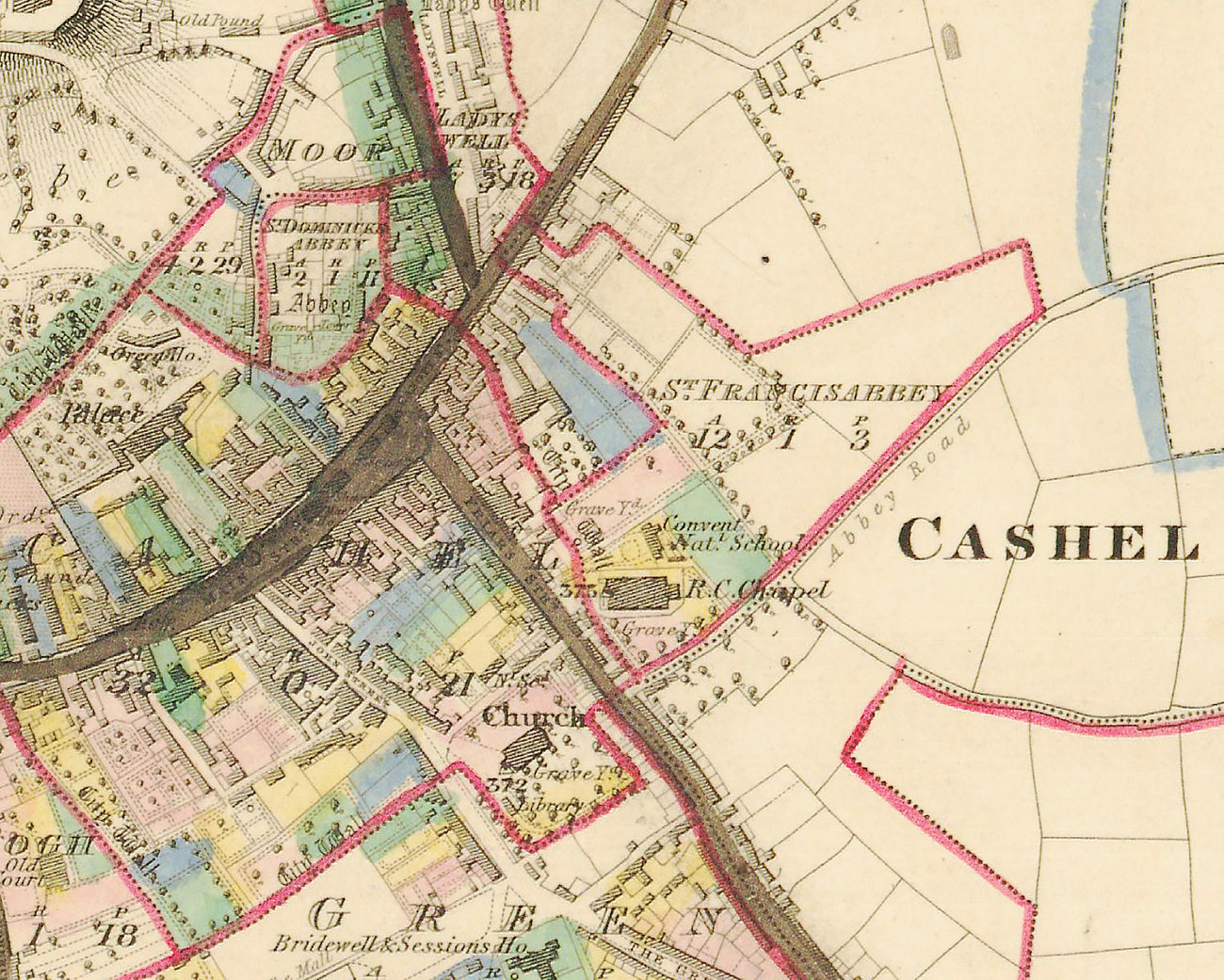

The site for the new chapel was also connected to the medieval ecclesiastical heritage of Cashel, but effectively moved the place of Catholic worship into the recently developed Georgian quarter of the city (figure 2). This was occupied by two impressive and architecturally significant buildings — the Church of Ireland archbishop's palace, designed by Edward Lovett Pearce and built in the 1730s, and the Church of Ireland cathedral, the completion of which predated the new Catholic chapel by two decades.Footnote 43 Comparisons between both Church of Ireland and Catholic places of worship by the end of the century framed and informed the construction and development of both. At the end of his commentary on the thatched chapel at Cashel, Thomas Campbell remarked that ‘yet, even here, it is possible that God may be worshipped in spirit in truth, for “he dwelleth not in temples made by hands, as if he needed any thing’”. However, he continued:

this argues not … that true religion should let her temples fall into ruin and decay. Much, very much, depends upon a decent exterior. What else has the church of Rome to support herself upon? Even that beggarly display of outward elements, exhibited in this old abbey of Cashel, has somewhat to engage the imagination, and somewhat to engage the imagination, and even to mend the heart.Footnote 44

Figure 2. Extract from the six-inch Ordnance Survey Map of Ireland (OS-Tipperary-1:10560-Sheet61-(Surv1838)-1843), showing the location of the old Dominican abbey, the R.C. Chapel and the Church of Ireland cathedral. Reproduced from a map in Trinity College Library, Dublin, with the permission of the Board of Trinity College, Dublin.

Campbell's reflections on Catholic worship can be understood as a critique of the contemporary state of Church of Ireland worship at Cashel. Construction on the Church of Ireland Cathedral of St John the Baptist had begun in the 1760s but had stalled by the time Campbell visited Cashel. This new building was the replacement for the medieval cathedral on St Patrick's Rock, which had been dismantled and unroofed in 1749, an action attributed to Archbishop Arthur Price.Footnote 45 A. P. W. Malcolmson provides a comprehensive account of the new cathedral's completion in his biography of Archbishop Charles Agar (1735–1809). The foundations for the new building had been laid in 1761, on the demolished site of the pre-existing church of St John, and it was not roofed until 1781. Malcolmson, citing Mark Bence-Jones, notes the different architects working in Cashel at the time, who may be responsible for the design of the new building.Footnote 46 Richard Morrison has been identified as the architect of the spire, with Bence-Jones suggesting that he may have been engaged for this commission on the strength of his father's earlier involvement. During Campbell's visit in 1775, worship was being conducted in a ‘sorry room, where the country courts are held’ and ‘a new church of ninety feet by forty-five was begun’, but it had been ‘raised as high as the wall plates’, and ‘in that state it has stood for near twenty years’.Footnote 47 When completed, it formed part of an elegant ensemble of Georgian buildings that was further enhanced by the construction of the Bolton Library in the 1830s (figure 3).Footnote 48

Figure 3. Cathedral of St. John (C.o.I.), Cashel, under construction in 1767, spire completed by 1807. Bolton Library, 1830s, located beside the cathedral. Author's photograph.

If the humble yet dignified thatched Catholic chapel was held up as an unflattering mirror to the established church with its unfinished cathedral, it is likely that the completion of that new cathedral then acted as a spur and motivation to the Cashel Catholics in deciding to build the new parish chapel of St John the Baptist. While the rationale of inadequate space was given in the 1868 Cashel Gazette, the decision to build a Catholic chapel on a prominent site in the newly established ecclesiastical centre in a similar architectural style and on a similar scale to the cathedral of the established church was likely to have been motivated in part by a desire to keep pace across the denominations.

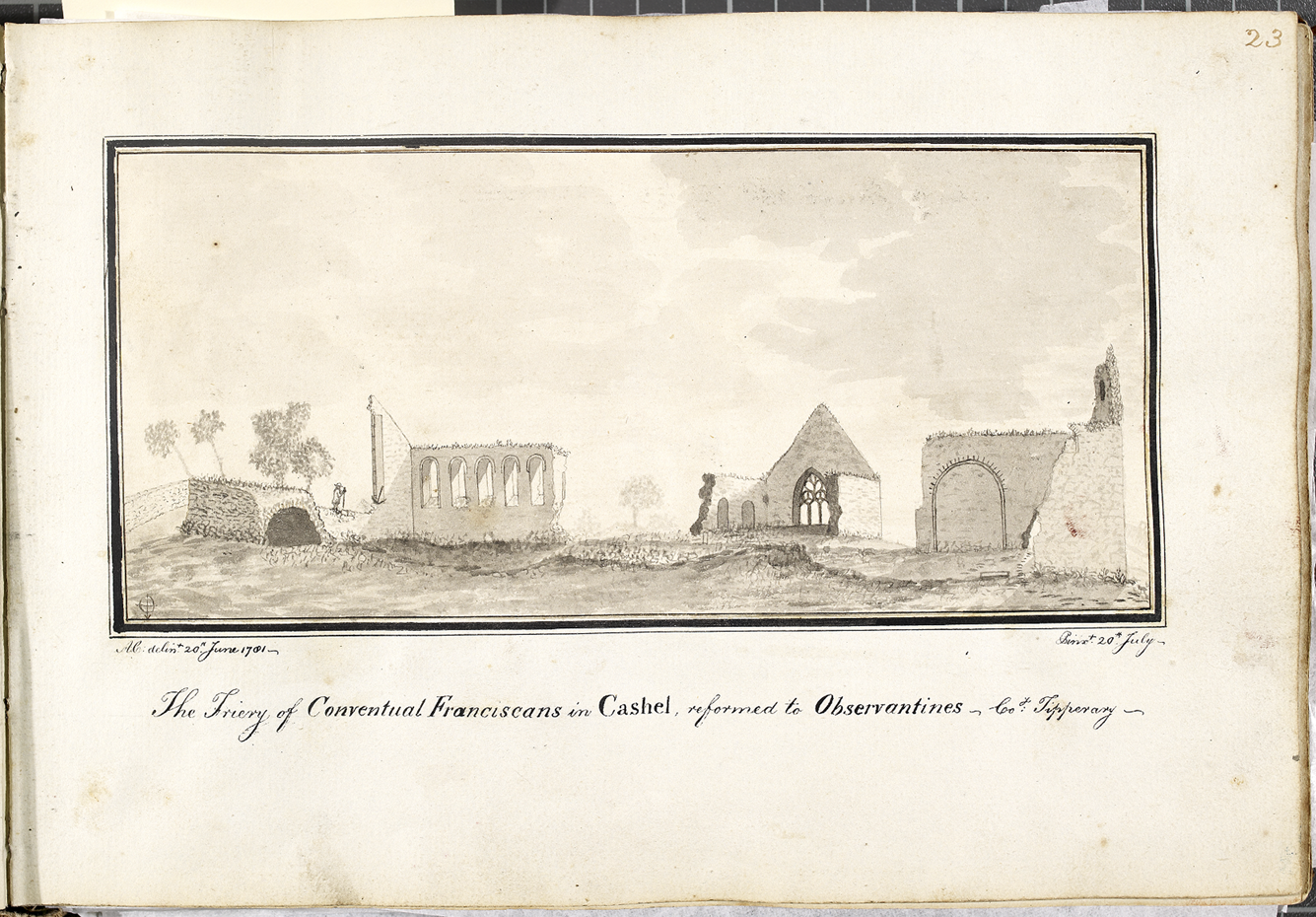

The new Catholic chapel was built on the site of the Franciscan friary, known as ‘Hacket's Abbey’, on Friar Street. Malcolmson notes that the ruins belonged to Joseph Damer, first earl of Dorchester (1718–89), who granted a lease for the new chapel.Footnote 49 The papers of Archbishop Thomas Bray (1746/7–1820) include a lease from 1815 for parts of St Francis Abbey for 999 years after the death of John Kyffin, made between Lady Caroline Damer and Fr Richard Wright, Cormac's successor and parish priest at St John the Baptist between 1804 and 1821. It is likely that this was the lease for land behind the chapel for the new school and convent included in the first Ordnance Survey map.Footnote 50 A similar lease was probably taken for the chapel, between the Damer family and either Cormac or Bray himself, who was parish priest before becoming archbishop and was succeeded by Cormac. A drawing by the Tipperary antiquarian Samuel Cooper depicts Mr Kyffin or one of his workmen in the process of levelling the medieval Franciscan friary in 1781 (figure 4). While the building had been badly damaged in 1757, the ruins were ultimately cleared to make way for the new parish church of St John the Baptist.Footnote 51 Malcolmson notes Agar's support for the project through donations and through his permission for a lane to be created (‘Agar's Lane’), connecting the two sites on Friar Street and John Street, despite his lack of support for Catholic emancipation.Footnote 52

Figure 4. Austin Cooper, ‘The Friery [sic: Friary] of Conventual Franciscans in Cashel, reformed to Observantines, Co.y Tipperary A:C: delint. 20th June 1781 ; Pinxt. 20th. July’, 1781, Coo 2122 TX (1) 23. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Consideration of the site of the new chapel demonstrates the extent to which late-eighteenth-century ecclesiastical infrastructure inhabited the pre-existing medieval urban footprint of Cashel. It also provides a useful example of the interrelationship between denominational architectural developments, and the progress of the construction, requiring the use of interim places of worship, over a number of decades. By the turn of the nineteenth century, the ecclesiastical centre of gravity in Cashel had been recentred on the triangle of buildings between the Church of Ireland archbishop's palace, the Church of Ireland cathedral on John Street and the new Catholic chapel on Friar Street.

II

In his 1808 account of the ‘new and elegant’ chapels being built across Ireland, Milner paid quite close attention to questions of scale and style. The facade of the ‘principal chapel, or rather church’ at Waterford is described as having an ‘extensive and lofty facade, with massive, but regular pillars, pilasters, entablature, and pediment, the latter surmounted with an ornamented cross’ (figure 5).Footnote 53 As already mentioned, his personal favourite, for its use of the Gothic style, was ‘Our Lady's at Cork’, and he noted that Thurles might exceed both ‘in exterior and interior grandeur and elegance’ when completed.Footnote 54 He criticised Irish architects for their ‘incongruous mixtures of different orders and styles of architecture’, combining Grecian style with pointed arches.Footnote 55 Milner's fluency in discussing architecture reflects his own great interest in the area — he published studies on Gothic architecture and commissioned architect John Carter to build his new chapel of St Peter in Winchester in an early ‘Strawberry Hill’ Gothic Revival style.Footnote 56 While Milner was perhaps more interested than most in style and design, his text provides valuable evidence of an awareness in late-eighteenth-century Ireland around stylistic choice and the meaning and significance of engaging specific styles over others.

Figure 5. ‘Catholic Cathedral, Waterford’, eng. & pub. by Newman & Co., 48 Watling St., London. Between 1860–80, ET A733. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

There are few references to style in episcopal records for Cashel during the period that the new chapel was being planned and built, with the main documentary evidence focused on leases and adequate accommodation through the construction of galleries. There is evidence, however, that architects were commissioned on the design of contemporary Catholic chapels, particularly on projects of the third type outlined in the introduction.Footnote 57 The ‘Carrickman's diary’ was written by James Ryan in Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary between 1787 and 1809.Footnote 58 Ryan recounts the building of the new chapel there in some detail, mentioning that an architect was engaged on the project. Francis Johnston, architect of what was the most prestigious ecclesiastical design commission of the period — the new Viceregal Chapel at Dublin Castle — also designed Catholic chapels in Drogheda and Kells in County Meath, and John Roberts was the architect of the Catholic ‘Grand Chapel’ at Waterford and of the Church of Ireland Cathedral in that city.Footnote 59

The examples of Johnston and Roberts reflect the engagement of professional architectural expertise across denominations, and this is continued into the early decades of the nineteenth century by figures like Thomas A. Cobden (1794‒1842) and James Pain (c.1780‒1877).Footnote 60 The clear attribution of Catholic projects to Johnston and Roberts is exceptional, however, and most pre-emancipation projects are not linked to a specific designer. John Roberts has been mentioned as the architect of the chapel at Cashel.Footnote 61 However, this is not substantiated by any documentary or archival sources and are not borne out by the evidence of the building itself. While Roberts may not have been the architect directly responsible for the Cashel chapel, it is highly likely that the example of his ‘Great Chapel’ at Waterford influenced its design. As is outlined below, Roberts's direct experience of London introduced an Anglo-Baroque strain to the ecclesiastical architecture of late-eighteenth-century Munster.

The chapel of St John the Baptist at Cashel was subject to several renovation programmes following its initial construction, and these are outlined in a brass plaque installed in the nave. The cut-stone front and the organ were added during the tenure of James McConnell, parish priest between 1830 and 1855. In his Topographical dictionary, Samuel Lewis described the ‘chapel of St John's’ as ‘a spacious and elegant structure, now undergoing extensive alteration and repair, including the erection of a spire’, as well as being ‘faced with hewn stone’.Footnote 62 Lewis also mentioned the Presentation convent behind the chapel. The planned spire was never completed. As parish priest between 1887‒1913, Thomas Kinane erected altars and the pulpit and added pews in the nave, as well as directing works to the windows and roof. Dean Innocent Ryan is noted on the plaque as having ‘remodelled’ and ‘remade’ galleries and added the mortuary chapel, the grotto, heating and electric light. Between 1914 and 1941, he also initiated works to the windows (front and galleries) and the organ, and added pews in the aisles.

Newspaper reports add further detail about these various works — for instance, in 1892 the Freeman's Journal published a detailed description of the ‘massive marble pulpit’ in the Renaissance style designed by W. G. Doolin, who had supervised the renovation of the church. The pulpit had been donated by Mr James O'Connor of Mountcashel, Clapham and was one of several additions during this period listed in the article, including a high altar, a Communion rail and stained glass by both Meyer of Munich and Cox and Buckley of London.Footnote 63 The colourful mosaic decorations were added to the exterior in the 1930s, as part of the programme led by Dean Ryan.Footnote 64

The church as it exists today, therefore, has been shaped by these different interventions and changes. However, photographs exist which provide valuable evidence of its interior condition before and after the Kinane works at the turn of the twentieth century. The photograph taken after the Kinane renovations is part of the Lawrence Collection in the National Library of Ireland, by Robert French, and has a date range of 1865–1914 (figure 6). It shows the marble pulpit in situ, but with the side aisles still unseated and, therefore, can be securely dated after 1892. The major changes made to the original fabric of the building by 1892 include the ornate wooden ceiling carried through over the galleries and the three-light round-headed windows above the altar. An earlier photograph, also by French and taken at least before 1892, is an important record of the interior prior to these works (figure 7). Given that the works undertaken in the 1830s seem to have been largely exterior, as described by Lewis, it is reasonable to assume that the majority of the features visible in the earlier photograph are part of the original interior scheme for the chapel.

Figure 6. St John the Baptist, Cashel, Co. Tipperary, taken between 1892 and 1914. The Lawrence Collection, L_CAB_09198. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Figure 7. St John the Baptist, Cashel, County Tipperary, view of the interior prior to renovations of the 1890s. The Lawrence Collection, L_ROY_00018. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

In plan, the chapel is essentially a rectangle, similar in many respects to the nearby Church of Ireland cathedral, which has an apse and entrance porch as later additions. As demonstrated by figure 7, the original interior included a shallow barrel vault ceiling with painted decoration, stone flags on the floor, and a wooden classical reredos behind the altar. This featured Corinthian pilasters and engaged columns, a broken segmental pediment, a ‘glory’ sunburst with the tetragrammaton motif and a frieze with putti and swags. The Baroque sunburst or ‘glory’ was a popular Tridentine Catholic motif.Footnote 65 It is more typically associated with the ‘IHS’ monogram over the altar, as seen in the classical interior of the mid-eighteenth-century chapel at Jenkin's Lane in Waterford (figure 8). Milner focused on the preferred decoration for altars in his 1808 text, noting ‘angels in the act of adoration, or of the monogram of JESUS, or of CHRIST surrounded by rays’.Footnote 66 The sunburst with tetragrammaton is, however, quite common in Catholic book illustration from this period.Footnote 67

Figure 8. Plaster sunburst with ‘IHS’ and putti above the altar in St Patrick's, Jenkin's Lane, Waterford. Author's photograph, 2022.

In form and style, the reredos at Cashel is a truncated, simplified version of that at St Ann's Church of Ireland on Dawson Street in Dublin, built in 1719, and is also similar in style to the reredos by Christopher Wren in the Temple Church, London from 1682‒89 (figure 9). The Church of Ireland church of St Catherine on Thomas Street in Dublin (c.1765) also has a reredos with a broken segmental pediment, with the break framing the centre of a Diocletian window. While not as close a comparison as that at St Ann's, it reflects the popularity of this reredos design. Unlike these exemplars, Cashel has a large painting of the crucifix at the centre, a characteristic of many Catholic chapels and churches before the 1850s, when altar paintings started to be replaced by large, decorated marble altarpieces, mosaic-work and stained-glass windows.

Figure 9. Wooden altar reredos, St Ann's Church (C.o.I.), Dawson Street, Dublin. Author's photograph, 2023.

The double-height galleries at Cashel are a significant original feature, with supporting piers, Ionic columns and terminating pilasters articulating the first-floor gallery. The Doric piers on the ground floor have a correct architrave and frieze, with triglyphs and metopes. The Ionic columns above meet a trabeated lintel, with corresponding entablature with a decorated frieze and dentil ornament. There is also a gallery above the doorway, which continues the entablature but curves forward. This gallery over the entrance now houses the organ and is supported by piers. Galleries were an important feature of most Catholic chapels of scale throughout this period but are typically located to the rear above the main door, in the transepts, or in both locations, and had relatively simply flat panels with minimal decoration and slim supporting columns (figure 10).

Figure 10. Typical early nineteenth-century wooden gallery in Golden, County Tipperary. Author's photograph, 2023.

The use of galleries with a classically detailed entablature running the length of the nave is quite unusual for the period, adding to the chapel's impressive and imposing classical character, and certainly reflecting a major change from the thatched mass house by the Dominican abbey. This type of arrangement would have been more common in Church of Ireland churches, such as those at St Werburgh's Church in Dublin (built 1715‒19 and partially rebuilt c.1759‒64). The Church of Ireland cathedral at Cashel also originally had galleries, of which only the section over the entrance door now remains following reordering.

Given the prominence of the ‘Great Chapel’ at Waterford designed by John Roberts, it is very likely that this building had a strong impact on other enterprising religious personnel interested in developing their own new, ‘elegant’ buildings. This is clear in the ‘Carrickman's diary’ — an entry relating to the building of the new chapel in Carrick-on-Suir noted that ‘the front of the galleries to be done in pannel work’ which was ‘to be done like the new chapel of Waterford’.Footnote 68 Roberts's wooden galleries at his Catholic ‘Great Chapel’ are remarkably elegant and are used to great effect in managing to articulate a somewhat awkward site and plan with a strong horizontal axis (figure 11).Footnote 69 They are single-height and are carried on wooden Ionic columns, rather than the piers found at Cashel. The galleries of the transepts to the left and right of the altar have a central outward curve that echoes the curving vaults of the ceiling. The ceiling is supported by giant Corinthian pillars. The panelling of the gallery acts as an extended frieze intersected by a giant order, echoing the arrangement of the exterior facade of the building that was so admired by Milner.Footnote 70

Figure 11. View of the wooden galleries to the right of the altar, Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity, Barronstrand, Waterford. Author's photograph, 2023.

However, in the interior, Roberts very effectively used the giant order to create depth and to clearly delineate the transept area from the wide nave. He did so by using a tripartite giant order — engaged Corinthian pilasters behind the gallery, then the central giant order intersecting the plane of the gallery panel, and then a third giant column which steps forward in front of the gallery, creating a three-dimensional ‘forest of columns’ effect from what is typically a more integrated, planar arrangement. This tripartite treatment of the giant order allows these classical elements more depth. With the Ionic columns supporting the wooden gallery, Roberts also allows orders of different scale to interact together across the space of the transepts, resulting in a spatially complex and innovative dynamic.

This is quite different to the elegant, yet much more traditional, arrangement used by Roberts at the earlier Christ Church cathedral, located nearby. While the interior at this Church of Ireland cathedral was altered at the end of the nineteenth century by architect Thomas Drew (1838–1910), a print from 1806 depicts the original box pews and straight double-height gallery (figure 12).Footnote 71 The ground floor piers are encased in what looks like wood carved to simulate rusticated masonry. These piers carry the panels of the gallery, which has Corinthian columns that meet the vaults of the ceiling. The columns intersect the plane of the gallery boards, with bases resting on the rusticated piers below. It is a very elegant, but much more traditional, arrangement than that at Barronstrand. As William Fraher has observed in his study of Roberts, both Waterford buildings clearly reflect the influence of his time articled in London and his experience of the Anglo-Baroque churches by James Gibbs (1682–1754).Footnote 72 Key elements of Gibbs's design, such as the use of the giant order intersecting the gallery panels at St Martin-in-the-Fields, are present in both of Roberts's Waterford cathedrals. The influence of Gibbs on Roberts is particularly evident in his treatment of how the columns meet the rib-vaulted ceilings in both Waterford cathedrals, with their distinctive block entablatures, again referencing the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields from the 1720s.

Figure 12. Inside the Cathedral of Christ-Church, Waterford, 1806, London: published by Edward Orme, 59 Bond St., 1806, ET C415. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

When the inventiveness and complexity of the gallery and treatment of the orders at Barronstrand are taken into account, it is highly unlikely that Roberts would have followed this project with the comparatively flat and more conventional gallery at Cashel, illustrated in figures 6 and 7. Key differences include the trabeated entablature at Cashel rather than the sculptural vaulting at both Waterford buildings and the absence of the giant order spanning the height of the building from capital to base at Barronstrand. While the gallery at Christ Church Cathedral is closer to that at Cashel in form, differences include the use of masonry piers (rather than recognisably Doric piers at Cashel) and Corinthian rather than Ionic columns for the upper storey.

The gallery at Cashel is closer to the more traditional triple-height arrangement at the ‘Sardinian Chapel’ in London, than Roberts's Gibbs-influenced designs.Footnote 73 The confident handling of the classical detailing at Cashel, however, does suggest a competent architect, and it is worth noting that there would have been experienced designers and craftsmen in the area following the completion of the cathedral, as well as other major civic building projects during this period such as the courthouse in Clonmel, built c.1800 by Richard Morrison.Footnote 74 The level of detail may also reflect the use of illustrated architectural books, such as James Gibbs's 1728 Book of architecture in the creation of fashionable and elegant interior.Footnote 75 The layers of paint over the wooden carving mean that the quality of the original carving cannot be assessed.Footnote 76

While Roberts's signature handling of classical elements is not present at Cashel, there are several other potential architects who could have been involved in the design of the chapel. These include the aforementioned Richard Morrison, as well as Oliver Grace who worked in Tipperary for Agar on several projects in the 1780s. Grace had designed a number of churches, and had submitted designs for the reworking of St Werburgh's Church in Dublin in 1756.Footnote 77 However, no archival sources have been found to date that would secure an attribution.

Having assessed the architectural features of the chapel at Cashel, and considered its potential attribution, it is worth exploring the implications of the stylistic decisions that were taken in this grand new Catholic building. Firstly, in plan and style, it clearly echoes the neighbouring Cashel Church of Ireland cathedral. This architectural dynamic of very similar development across denominations is also evident at Waterford, with the Barronstrand ‘Great Chapel’ following the style established by the Church of Ireland cathedral there and even engaging the same architect. While the archbishop of Cashel had moved his residence to Thurles by the middle of the eighteenth century, with its own grand chapel that would later become the metropolitan cathedral, the chapel at Cashel operates at contemporary cathedral scale in the medieval cathedral city.Footnote 78

Secondly, the level of classical detail reflects a confident use of the classical language of architecture across regional Ireland during this period, as well as in the urban centres. It is revealing that the elegant new chapels at Cashel and Carrick-on-Suir engage the Anglo-Baroque idiom promoted by Gibbs in London, which had been expertly translated in Waterford by Roberts. Cashel represents a highly competent regional translation of some of the most fashionable and innovative ecclesiastical designs of the period.Footnote 79

Finally, attention to architectural style, and to possible models and influences, allows for a consideration of the intended impact of these Catholics buildings and to see them as examples of Catholic building in a participatory mode. Architecture was one of the major expressions of status and civic leadership in eighteenth-century Ireland and had largely been dominated by the Protestant ascendancy class.Footnote 80 The construction of church buildings of scale and ambition, however, was one arena in which Catholics could begin to express their position in the public sphere and in public space. The classical language of architecture was aligned with the buildings of the state and with the operation of colonial government in Ireland. These buildings, therefore, can signal a co-opting by Catholics of means and ambition of available forms of power in this period of Catholic relief.

III

A comprehensive consideration of the social and political contexts for the chapel at Cashel could result in a detailed network analysis of the place and its people, but that is beyond the scope of this architectural case study. However, while this article is primarily focused on architectural rather than social themes, there are three salient contexts that illuminate the building in particular, involving religious personnel, members of the laity who were involved, and devotional and liturgical reforms. Firstly, it is noteworthy that the religious personnel who led these building projects were educated in the grand architectural environments of European colleges in Rome, Salamanca and Paris. Tadhg Ó hAnnracháin notes that the religious transformation of early modern Ireland was ‘mediated by figures who had an intense experience of transnational travel at a vital and formative stage of their lives’, and this pertains to architecture and religious space as much as other aspects of religious life.Footnote 81 Lay Catholic elites who were educated in continental schools and colleges would also have had experiences of grand architectural liturgical environments.Footnote 82 Their experiences in these cities must have shaped their architectural imagination and their understanding of the appropriate spaces for Catholic worship.

Edmund Cormac was the individual priest most closely associated with the project.Footnote 83 The 1868 Cashel Gazette article which described his ‘razing’ of the existing chapel to the ground in order to build the new edifice also stated that Cormac covered the cost of the new building himself. The paper published a translation of a Latin epitaph for Cormac, which reiterated that idea that the ‘sacred pile’ was ‘unaided raised, with his own purse’.Footnote 84 An earlier source for Cormac's role in financing the project is found in the Irish Magazine and Monthly Asylum of 1811, which noted that it was ‘to the private purse, and public exertions of this worthy clergyman, the Catholics of Cashel are beholden for the magnificent chapel’.Footnote 85 The mention of ‘public exertions’ suggests that Cormac had been responsible for marshalling funds, as well as providing them personally. Archbishop Agar's letters record requests for support by Cormac for the new building.Footnote 86 The discourse delivered during the 1821 funeral for the Catholic archbishop Thomas Bray noted that ‘his purse and his labour left Cashel a cathedral’, suggesting that, while Cormac may have been instrumental, the project was enabled by wider range of donors.Footnote 87

In her short biographical sketch of Cormac, Claude Meagher noted that he was a native of Thurles, was educated in Paris and was ordained in the Church of St Nicholas du Chardonnet in Paris in May 1770. He lived in Palmer's Hill House while in Cashel and opened an academy in Thurles in 1791.Footnote 88 He was related to Archbishop Butler I of Cashel and worked closely with Archbishop Butler II, being left £20 in his will.Footnote 89 The church of St-Nicholas-du-Chardonnet was rebuilt between 1656 and 1763 and, therefore, would have been a site of architectural interest and innovation to those who experienced it.Footnote 90 The fact that Cormac seems to have been able to donate a significant substantial amount to the new chapel himself, and lived in a substantial house in Cashel, suggests that he was a man of considerable means.Footnote 91 In the absence of archival records providing an insight into Cormac's personal views on architecture, these biographical details are useful in reconstructing some sense of his experiences and the influences that certain buildings may have had on him, as well as his capacity to lead the construction of new projects.

The Catholic archbishops of Cashel that Cormac encountered were also involved in architectural expansion.Footnote 92 Archbishop Butler II spent some of his inheritance on a new episcopal residence in Thurles. Butler's successor was Thomas Bray, born in Fethard, who was Catholic archbishop of Cashel and Emly at the time that the new chapel in Cashel was being built.Footnote 93 Bray's papers include a request for the dimensions of Kells chapel to be sent to him, which had been drawn up by the fashionable architect Francis Johnston.Footnote 94 His papers also include several leases for chapel grounds, as well as references to the provision of galleries in various churches and an incident of Protestant protest against the plan to build a Catholic chapel next to the Church of Ireland building in Bansha, County Tipperary.Footnote 95 As well as the reference to Cashel, noted above, the funeral discourse for Bray pointed to his architectural involvement with the chapel at Thurles. The speaker, Rev. Michael Laffin, noted that ‘you are now, my reverend brethren, sitting in the centre of his charitable donations’, and that ‘this chapel tells forth his zeal, his labour, and his means; though not built according to the strictest rules of architecture’.Footnote 96 The personal records of the Catholic archbishops of Cashel, however, are for the most part heavily dominated by the pressing issues of the day, in particular questions of succession, the veto controversy, and engagement with the various colleges on the continent. Therefore, despite some passing references to building practices and charitable donations, the lack of any real evidence of engagement with architecture in episcopal papers suggests that it was low on the agenda at the turn of the century even of ambitious archbishops and largely left to parish priests.

Finn's Leinster Journal listed Cormac as parish priest, alongside two men who can be presumed to be members of the laity — John Harrington and Edmund Scully. While Harrington has proved elusive, Edmund Scully is most likely to be the brother of James Scully of Kilfeacle and uncle of Denys Scully.Footnote 97 The involvement of the Scully family reflects, perhaps, the practice at the time for fundraising and development of new chapels to be led by a committee comprised of a parish priest with members of the laity. While the Scully archives are reticent on Edmund's life, and the political affiliations of one family member cannot be taken as representative of all, the Scullys were a well-established and wealthy family in the locality.Footnote 98 In his political pamphlets, Denys Scully strongly promoted the idea that Catholic loyalty to the monarchy would be the surest way to secure full Catholic emancipation.Footnote 99

Returning to the idea that chapels in the Anglo-Baroque style can be interpreted as an ‘architecture of participation’, the involvement of the Scullys points to the role of these buildings as signalling Catholic respectability and reliability in an era of revolution, and chapels were very often the location of loyalist, pro-union petitions and addresses during this period.Footnote 100 Together with the role of galleries in clearly making social class and status visible, many of these chapels seem to have been spaces where a particular anti-revolutionary and respectable Catholic identity was performed. If identity can broadly be understood through practices of belonging, the development of elegant chapels like St John the Baptist at Cashel is one such practice, signalling a desire to belong to those groups in society with political as well as social and economic power.

Finally, the fact that the closing decades of the eighteenth century were a period of determined Catholic reform, as well as political relief, helps us to understand the function and significance of the chapel at Cashel. Dáire Keogh has argued that by the 1780s, ‘energetic and reforming bishops’ were focused on reviving liturgical practice across the country.Footnote 101 If the sources for the period are quiet on matters of architectural style, they do confirm the renewed importance of the chapel building as the centre of devotional and parochial life. Key reform practices included the keeping of parochial baptism and marriage records, as well as attempts to stem unruly behaviours at patterns and wakes.Footnote 102 For example, Thomas Bray was a keen reformer, editing the statues and regulations of the diocese and publishing the Statuta synodalia pro unitis diocesibus Cassel. et Imelac in two volumes in 1813. This emphasised regularity of attendance at parish churches, and the importance of sacraments, holy days and events such as the stations of the cross. All clergy, whether secular or regular, were strictly charged ‘not to celebrate Mass at the wake-house’, and heads of families were strictly charged not to ‘suffer lascivious plays, or prophane amusements at wakes in their houses’. ‘All unnatural screams and shrieks’, ‘tuneful cries and elegies at wakes’ and ’the savage custom of howling and bawling at funerals’ were condemned, together with ‘plays and amusements’ which were in ‘mock-imitation of the sacred rites of the church’.Footnote 103

Bray's text included detailed instructions on how parishioners were to comport themselves in their new environment for worship, describing the precise way that they should receive Holy Communion. They should ‘kneel upright with the head erect and steady; keep the Communion-cloth or towel extended from under the chin; your eyes modestly looking down; the mouth wide open’.Footnote 104 This emphasis on the correct physical engagement and decorum suggests that these new chapels were intended to be spaces for quite a different experience of Catholic devotional life than parishioners may have hitherto encountered. The construction of chapels like St John the Baptist at Cashel was intended, therefore, to accommodate these reformed liturgical and devotional practices for Catholics of all social classes, and to be compelling and attractive environments for parishioners.

IV

By the final decades of the nineteenth century, many of the chapels built during this initial period of Catholic relief and reform were being replaced by much grander designs. The triumphalist and celebratory rhetoric at consecration and dedication ceremonies gives us an insight into how these earlier buildings were perceived less than a century after they had been built. While the ‘grand chapel’ at Thurles had been considered one of the most impressive of its day, by 1879 its demolition was described thus:

bit by bit the time-worn walls of the old chapel were effaced, its humble plan began to expand into the stately aisles and transepts, its low-browed roof was outtopped with towering arcades of pillars, until its last vestiges were incorporated in the north transept walls, and from its ashes, as it were, arose the present grand Cathedral pile in fresh young beauty.Footnote 105

David Fleming has argued that the enduring image of the Mass Rock in the eighteenth century can be linked to the fact that it is a ‘tangible icon, and a symbol of suffering and persecution that transcended time’.Footnote 106 In a similar rhetorical dynamic, the description of the old chapel at Thurles as being ‘humble’ and ‘low-browed’ perhaps suggests the desire to forget many aspects of the late-eighteenth-century Catholic experience in favour of a narrative of communal struggle against a shared oppressor.

The fact that the chapels at Thurles and Cashel were evidence of a Catholic community that was frequently loyalist and anti-revolutionary in their political allegiance, and highly aware of class status and prestige, was at odds with the emotive narratives of triumph over past adversity that motivated much Catholic architectural expansion by the late nineteenth century. Indeed, the public rituals around these late-nineteenth-century churches and cathedrals explicitly focused attentions of parishioners on a shared history of struggle during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, rather than the different experiences of the more recent past.Footnote 107 However, the evidence of these pre-emancipation chapels contributes to the ongoing scholarly reassessment of the era of the penal laws and provides an important insight into the variety of experiences during a period of change for Catholics in Ireland.Footnote 108