1 Introduction

1.1 With or Without the Idea of Organic Progress?

The word ‘progress’ comes from the Latin word pro-gradi, meaning to walk forward. In English, the term ‘progress’ was, until the sixteenth century, used in the axiologically neutral sense of walking, that is, travel and movement forward in space. However, starting from the seventeenth century, the word gained an additional meaning that is still in use today: change has a positive value, referring to something leading towards a better, more elevated state (Simpson and Wiener Reference Simpson and Wiener1989). Thus, in the notion of progress, there is both a descriptive element (change in time) and an axiological element – from the Greek word axios, valued – related to what is considered to be ‘good’ and ‘better’ (Goudge Reference Goudge1961).

The idea of progress has several domains of application. Applied to human civilization as a whole, the idea was central to the Enlightenment movement of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, before seeing a decline during the twentieth century (Wagar Reference Wagar1972). The idea of progress can also be applied more specifically to the technological domain (change towards better technical artefacts) and to the scientific domain (change towards better scientific theories). Another field of application of the idea of progress is the organic domain, where this change towards the ‘better’ refers to the evolutionary history of living beings. The application of the idea of progress to the organic domain raises questions about the complex relationship between organic progress and evolutionary theory, which is the main focus of this Element.

The historian of science John C. Greene sums up this question nicely: ‘Evolutionary biologists, it seems, can neither live with nor live without the idea of progress’ (Greene Reference Greene1990). The reasons why evolutionary biologists should not ‘live with’ organic progress are quite easy to understand. At first glance, ‘progress’ sounds like a non-scientific term: the axiological element seems to imply a subjective judgement, which should have no place in a scientific discipline. Indeed, in the past, organic progress underpinned a clearly anthropocentric view: humanity was considered the ‘best’ organism at the top of the progressive evolution (Ruse Reference 82Ruse1996), as in the representation of the ‘chain of being’ by Charles Bonnet (Bonnet Reference Bonnet1745).Footnote 1

The Darwinian revolution, however, should have once and for all rejected the anthropocentric perspective: Homo sapiens is just one branch of the tree of life, rather than the final product of the ‘chain of being’. Thus, we may think that detachment from the ‘men at the top’ perspective should also entail the idea of organic progress being abandoned starting with Darwin. Yet the history of biological thought shows that this is not the case. In his book Monad to Man: The Concept of Progress in Evolutionary Biology, Michael Ruse shows that the idea is present in Darwin’s thought and in the work of the authors of the Modern Synthesis across the twentieth century (Ruse Reference 82Ruse1996).

It is thus pertinent to ask why evolutionary biologists seem unable to ‘live without’ some idea of organic progress. Several options can be considered:

Because of some anthropocentric bias. There may be some influence of metaphysical remnants of the idea that man is at the top of the chain of being (despite the detachment that we should have today from these beliefs).

Because of some cultural bias. For example, the idea of ‘optimization’ as applied in human occidental societies (e.g., to production or technical artefacts) could lead biologists to overestimate the relevance of this notion as applied to organisms – see for example the arguments in Hamant (Reference Hamant2022).

Because there are good theoretical arguments that some ‘change towards the better’ is legitimate within evolutionary theory, for example, some conceptual implication of the theory. In that case, it should be possible to clearly identify these arguments and clarify this notion of ‘change towards the better’.

In contemporary evolutionary biology, the mainstream position seems to be that there are no good theoretical arguments for organic progress (Desmond Reference Desmond2021): I refer to the intuition against organic progress.Footnote 2 This intuition is often related to the arguments of Stephen Jay Gould, the main critic of organic progress in the twentieth century.

However, there are also some renowned biologists who have an intuition for a notion of organic progress, that is, believing there are good theoretical arguments in favour of a progress notion (e.g., George Gaylord Simpson, Richard Dawkins, and Geerat Vermeij). Evolutionary theory would conceptually imply something that can be labelled as a ‘change towards the better’. This discussion has been reopened recently and is ongoing (Rosenberg and McShea Reference Rosenberg and McShea2008, Desmond Reference Desmond2021).

This Element contributes to the debate by focussing on two main questions:

1) There is no unanimity on discarding organic progress from evolutionary biology. Why? Are there any theoretical arguments for using the normative terms ‘good’ and ‘better’ within evolutionary theory?

2) If there are, can we clarify the idea that some ‘change towards the better’ would be conceptually implied by evolutionary theory?

Since the conceptual question of organic progress is elusive, I will begin by presenting a tripartite distinction, before explaining the strategy to tackle these two main questions.

1.2 Cause, Criterion and Scope of Progress

This distinction between cause, criterion and scope of progress is inspired by the historian Warren Wagar (Reference Wagar1972), who proposed it for the progress of human civilization: the belief that human civilization has moved, is moving and will move in a desirable direction (Bury Reference Bury1920). Wagar distinguishes three key elements when considering the progress of civilization: agency, content and subject of progress (Wagar Reference Wagar1972, pp. 4–5). ‘Agency’ is the cause of this improvement, for example divine providence, collective human effort or ‘great men’. ‘Content’ is the criterion by which we judge whether there has been an improvement, for example material health, knowledge or wealth. What Wagar calls ‘subject’ corresponds to the extent or scope of progress, for example the whole cosmos, humanity or a single nation.

Let us now consider organic progress: the idea that during the history of life, there has been a change towards organic forms that are, in some respects, ‘better’ than preceding forms. Here it is possible to apply the distinction proposed by Wagar and raise three corresponding questions:

Cause: What is driving the improvement? As we will see, the mechanism of natural selection is generally considered by evolutionary biologists to be the cause of organic progress.

Criterion: Which properties are we referring to when talking about progress? It could be argued that complexity, intelligence or perception of the environment have improved during the history of life: these are criteria by which to judge a possible improvement. It could also be argued that ‘something’ is improving, but it is not necessarily related to a single property.

Scope: To which ‘range of life’ does the improvement apply? For example, organic progress might concern life as a whole (thereby having a global scope), or only certain specific lineages (thereby having a local scope). Thus, the scope concerns the ‘framing’ of organic progress in time and space.

1.3 Structure of the Element

In this Element, I start by tackling the question of natural selection as a potential cause of organic progress. In Section 2, I present the positions of two authors who have opposed intuition on this issue: Charles Darwin and Stephen Jay Gould. While Darwin’s intuition is that the mechanism of natural selection may cause some kind of change towards the better, Gould has devoted several works to claiming that the notion of progress has no legitimacy within evolutionary theory. Gould (Reference Gould1996) is well known for arguing that, at a global scale, the increase in complexity across evolutionary history might be due to a stochastic process rather than natural selection (for Gould’s argument of the ‘left wall’, see Section 8). Then, in Section 2, I present relevant arguments put forward by Gould against organic progress. In particular, I focus on the argument that any possible ‘change towards the better’ can, across evolution, be destroyed by mass extinctions (Gould Reference Gould1985, Reference Gould1989).

In Section 3, I consider Darwin’s intuition on organic progress and discuss whether it can be made more precise concerning the criterion and scope. I do so by drawing on Richard Dawkins. For Dawkins, the concept of adaptation by natural selection conceptually implies organic progress on small and medium timescales. This notion only allows us restricted comparisons between ancestors and descendants within a lineage. Even if this progress might be destroyed, Dawkins argues that it still counts as a betterment in the organisms’ ‘equipment for survival’. Although Dawkins offers more precise arguments for organic progress than Darwin, a significant objection remains unaddressed: are ‘normative’ terms (good, better) acceptable in the context of a scientific theory?

Section 4 is devoted to the previous question. Drawing on Rosenberg and McShea (Reference Rosenberg and McShea2008), I claim that there are theoretical arguments for defending a specific kind of instrumental value in evolutionary biology, which can be called ‘organic value’. Organic value has nothing to do with moral issues or with the notion of ‘intrinsic value’. It just implies the notion of relative value with respect to a means: ‘X is instrumentally valuable for the purpose of P’. After presenting this framework, I examine an objection to organic value: can we speak of purposes for organic entities other than human beings? Countering this objection, I claim that purposes can be understood with reference to the concept of ‘function’. I further argue that this concept implies an axiological polarity, while having a proper and legitimate place within biology. I answer with an affirmative to the first question (Are there any theoretical arguments for using the normative terms ‘good’ and ‘better’ within evolutionary theory?), provided that normative terms are clearly understood as referring to organic value.

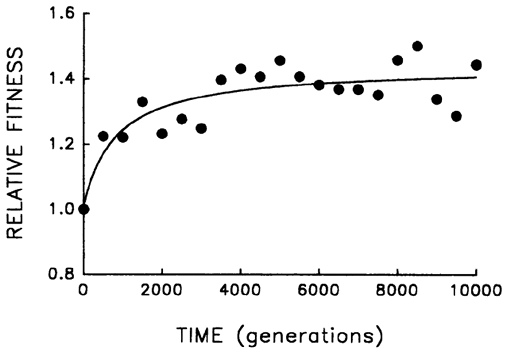

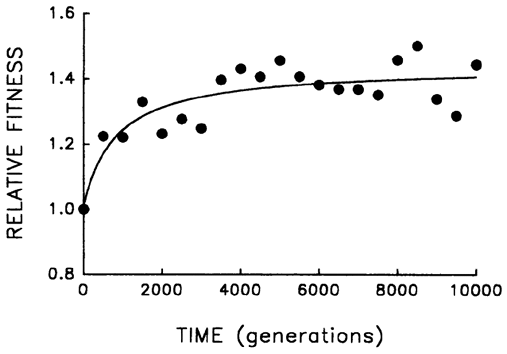

I then move to question two: can we further clarify Dawkins’ notion of local progress? I tackle this question in successive steps. In Section 5, I present two empirical cases from the fossil record for which there is a strong intuition that something is getting better. In Section 6, I draw on these two cases to propose a refinement of Dawkins’ notion. Based on this, I propose that adaptation conceptually implies that ‘something gets better’ in this specific sense: in the adaptive process, organic traits in a population get better with respect to a biological function, while the condition of ‘all other things being equal’ holds. I label this notion ‘Functional Improvement of Organic Traits’ (FIOT). This analysis leads me to propose a new way of looking at some classical issues in philosophy of biology, such as the relationship between organic structures, functions and the environment. Once the notion is refined, I consider whether there is more direct evidence for FIOT by looking at experimental evolution. In Section 7, I examine the results of the Long-Term Evolutionary Experiment by Richard Lenski and interpret these results based on my account.

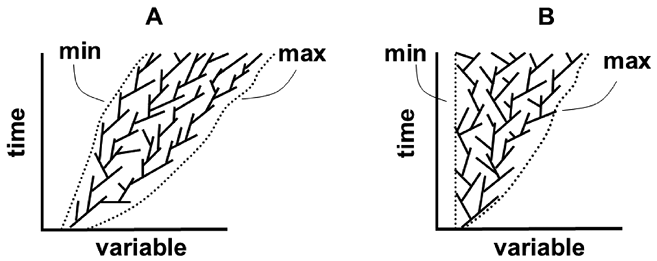

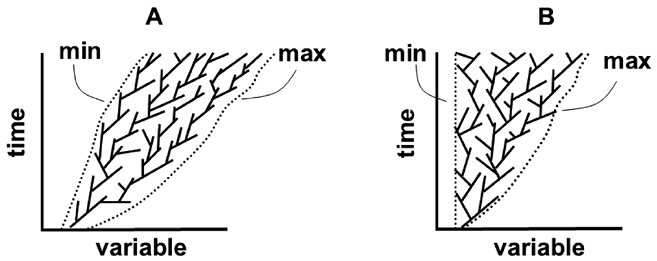

In Section 8, it is finally time to turn the discussion towards organic progress on a global scale. Despite Gould’s powerful criticism related to mass extinctions, I ask whether there may be good theoretical arguments to defend global progress. I start by clarifying what macroevolutionary trends are and that only natural selection allows us to speak of progressive trends. After briefly presenting the main candidates for progressive trends, I focus on complexity and I show, following the palaeobiologist Daniel McShea, that it is not a tenable criterion. This analysis allows me to highlight the requirements for a satisfactory criterion for global progress and thereby try another direction of inquiry. Following an insight of the French philosopher Georges Canguilhem, and based on the recent framework of Bourrat, Deaven et al. (Reference Bourrat, Deaven and Villegas2024), I suggest that robustness of adaptedness and evolvability are promising criteria for global progress, at least from a theoretical standpoint.

2 Rival Intuitions about Organic Progress

2.1 Darwin’s Intuition on ‘Competitive Highness’

Darwin’s attitude towards the question of organic progress is not straightforward: the father of evolutionary theory continually struggled with this ‘inextricable’ subject (Darwin Reference Darwin1858) and indeed he was quite embarrassed by it. The literature provides several interpretations of Darwin’s attitude; here I mainly follow the reconstructions of Ospovat (Reference Ospovat1981), Radick (Reference Radick2000) and Shanahan (Reference Shanahan2004). The main point that I focus on is that Darwin tried to characterize what linked the mechanism of natural selection with some kind of organic improvement, setting out for the first time the idea of progress in terms of competitive advantage.

On several occasions, Darwin wonders what naturalists mean by ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ organisms. In a passage in On the Origin of Species, he says that naturalists have not yet defined to each other’s satisfaction what is meant by high and low forms (Darwin Reference Darwin1859, p. 337). However, he adds, there seems to be one sense in which it is possible to talk about ‘higher’ organic forms:

But in one particular sense the more recent forms must, on my theory, be higher than the more ancient; for each new species is formed by having had some advantage in the struggle for life over other and preceding forms. If under a nearly similar climate, the Eocene inhabitants of one quarter of the world were put into competition with the existing inhabitants of the same or some other quarter, the Eocene fauna or flora would certainly be beaten and exterminated; as would a secondary fauna by an Eocene, and a palæozoic fauna by a secondary fauna.

Following the logic of his theory, the more recent forms have beaten the preceding forms in the struggle for survival, and thus they are ‘in one particular sense’ higher. In Darwin’s thought experiment, if Eocene forms were placed in competition with present forms, the latter would exterminate the former. It is relevant to note here the importance of the condition ‘under a nearly similar climate’, referring to the supposition of some constancy of the environment (see further discussion that follows). He concludes:

I do not doubt that this process of improvement has affected in a marked and sensible manner the organisation of the more recent and victorious forms of life, in comparison with the ancient and beaten forms; but I can see no way of testing this sort of progress.

Darwin believes that a kind of ‘improvement’ has taken place, but he acknowledges that this kind of progress is impossible to test as we do not have a ‘time machine’ to perform the experiment. Indeed, the word ‘improvement’ is present in the definition of natural selection itself from the second edition of On the Origin of Species:

This principle of preservation, I have called, for the sake of brevity, Natural Selection; and it leads to the improvement of each creature in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life.

In the basic Darwinian scheme, natural selection is the result of (1) organisms presenting variations (rendering them more or less fitted to their life conditions) and (2) a limitation of resources (Malthusian principle). Some organisms are fitter than others in relation to life conditions and, resources being limited, they therefore have a competitive advantage. This mechanism takes place over time. Let us consider, in a ‘quarter of the world’, an abstract organic community at time 1 and at time 1000. Can the organic community at t1000 be considered as somehow ‘better’ than the more ancient? Or, rather, should we say that the organic community t1000 is adapted to its life conditions exactly as the community at t1 was adapted to their own life conditions?

Darwin seems to think (despite the acknowledged difficulty of empirically testing) that the recent organic community should be considered somehow ‘better’. In the attempt to justify this position, he introduces the expression ‘competitive highness’ in a letter to his colleague and friend Joseph Dalton Hooker (Darwin Reference Darwin1858). With this, Darwin refers to forms whose superiority is expressed by the fact that they have won in the competition with other forms. This is true of recent forms compared to ancient forms in the same habitat, as in the thought experiment cited earlier. This is also true, for Darwin, for species inhabiting a very large area when compared to species in small areas. As explained to Hooker, Darwin believes that the larger the area, the larger the number of organic forms that are present and can interact, resulting in more severe competition (Darwin Reference Darwin1858). Organic forms that have withstood more severe competition are ‘superior’: the plants of Eurasia (large area) are the most ‘improved’ and thus are able to withstand the ‘less perfected’ Australian plants (Australia being a smaller area, with less intense competition).

It should be noted that, in Darwin’s thought experiment, the criterion ‘under a nearly similar climate’ is crucial. The intuitive idea is that, if the change in ‘life conditions’ is too dramatic between t1 and t1000, the axiological comparison between organisms cannot have any meaning: we should rather think that the t1000 organic community is adapted to its life conditions exactly as the t1 community was adapted to its own life conditions. The ‘life conditions’ of an organism may be inorganic (e.g., temperature and light exposure), or organic (e.g., symbionts, parasites, competing species, and predators). With the expression ‘under a nearly similar climate’, Darwin seems to presuppose a relative constancy of inorganic conditions of life. Inorganic conditions would be somehow ‘fixed’ and selective pressure mostly related to competition between organisms. Following Darwin’s reasoning, t1000 organic forms may be thought to be competitively better than those at t1, where ‘better’ is relative to the fixed abiotic conditions. However, it is unclear which kind of organic forms Darwin is considering here: is he comparing a whole extant organic community in a quarter of the world (e.g., the whole extant Australian fauna) with a whole Eocene organic community (e.g., the whole Eocene Australian fauna)? Before returning to the problems in Darwin’s reasoning exposed so far, it is important to note that ‘competitive highness’ is not the only notion of organic progress that is considered by Darwin, as will emerge in the next section.

2.2 Darwin on ‘Competitive Highness’ and Complexity

From the third edition of Origin (Darwin Reference Darwin1861), Darwin elucidates another sense in which it can be said that one organic form is superior to another: the morphological differentiation of parts and specialization to different functions. This is generally what is meant when biologists speak about ‘complexity’. Darwin explicitly refers to Karl Ernst Von Baer and Henri Milne-Edwards:

Von Baer’s standard seems the most widely applicable and the best, namely, the amount of differentiation of the different parts (in the adult state, as I should be inclined to add) and their specialisation for different functions; or, as Milne Edwards would express it, the completeness of the division of physiological labour.

Thus, there are two senses of progress in Darwin’s reasoning, which are clarified in a letter to Hooker (Darwin Reference Darwin1858). ‘Highness in the common acceptation of the word’ refers to complexity, while ‘competitive highness’ is related to success in the struggle for life and might also be related to ‘degradation of organization’. Darwin takes the example of the blind, degraded, worm-like snake that might supplant more complex forms of earthworms: the example shows that morphologically simple organisms can be competitively ‘better’ than complex ones.

Yet while Darwin clearly sees that the two senses of ‘highness’ can be in principle decoupled, he seems to claim that they usually go hand in hand. This claim depends on accepting a premise: that complexity is generally ‘an advantage to each being’ (Darwin Reference Darwin1861, p. 364). Once this premise is accepted, it can be affirmed that modern forms should be ‘higher’ than ancient forms with respect to both competitive success and morphological complexity. The ‘coupling’ of the two senses of ‘highness’ is clear in this passage of the third edition of Origin:

As the specialisation of parts and organs is an advantage to each being [complexity], so natural selection will constantly tend thus to render the organisation of each being more specialised and perfect, and in this sense higher; not but that it may and will leave many creatures with simple and unimproved structures fitted for simple conditions of life, and in some cases will even degrade or simplify the organisation, yet leaving such degraded beings better fitted for their new walks of life. In another and more general manner [competitive highness], we can see that on the theory of natural selection the more recent forms will tend to be higher than their progenitors; for each new species is formed by having had some advantage in the struggle for life over other and preceding forms. (…) So that by this fundamental test of victory in the battle for life [competitive highness], as well as by the standard of the specialisation of organs [complexity], modern forms ought on the theory of natural selection to stand higher than ancient forms.

It is interesting to note that, after this passage, Darwin raises the question: ‘is this the case?’ In the same edition from 1861, he writes:

Is this the case? A large majority of palaeontologists would certainly answer in the affirmative; but in my judgment I can, after having read the discussions on this subject by Lyell, and Hooker’s views in regard to plants, concur only to a limited extent. Nevertheless it may be anticipated that the evidence will be rendered more decisive by future geological research.

Darwin then changes this passage in the successive editions of Origin and seems to have increasing confidence in the reasoning. In 1866, he writes that he cannot look at the conclusion ‘as fully proved, though highly probable’ (Darwin Reference Darwin1866, p. 402). Three years later, he supposes that ‘the answer must be admitted as true, though difficult of full proof’ (Darwin Reference Darwin1869, p. 410).

Here I have briefly exposed Darwin’s reasoning about organic progress, which rests on two senses of ‘highness’: competitive highness and complexity. For my argument, I prefer to start by focussing on Darwin’s idea of competitive highness decoupled from the notion of complexity, which I will treat in Section 8. For the moment, let us focus on competitive highness and consider the opposite intuition about progress, put forward by Stephen Jay Gould.

2.3 Gould’s Intuition against Organic Progress

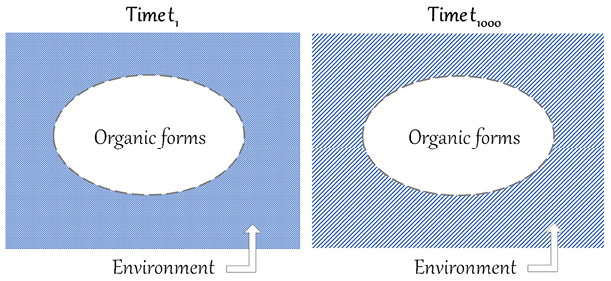

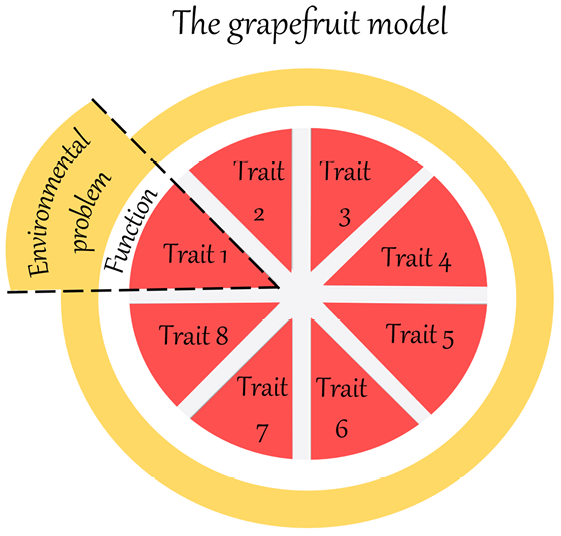

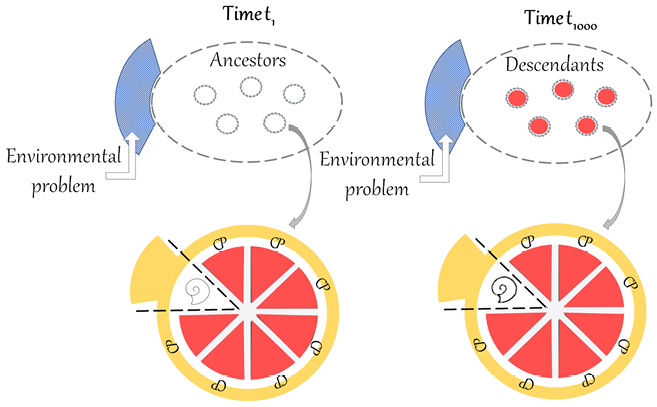

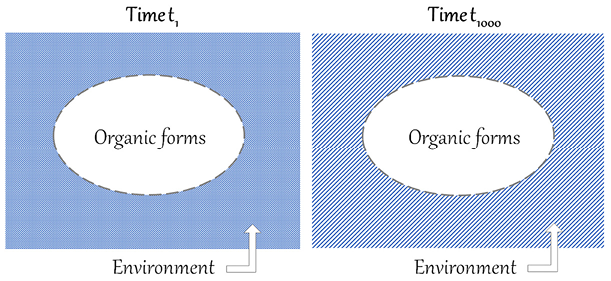

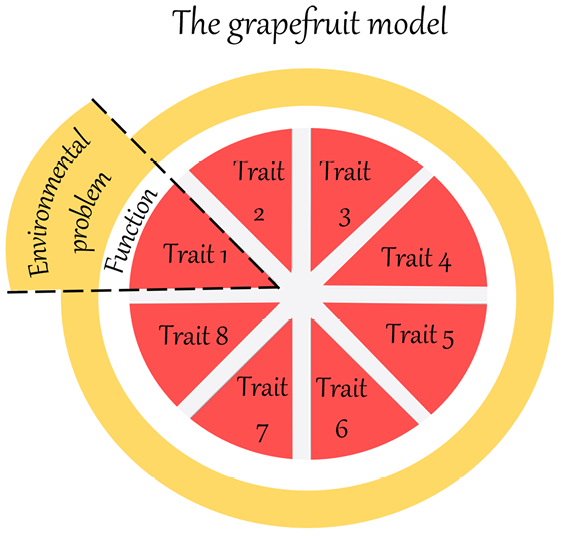

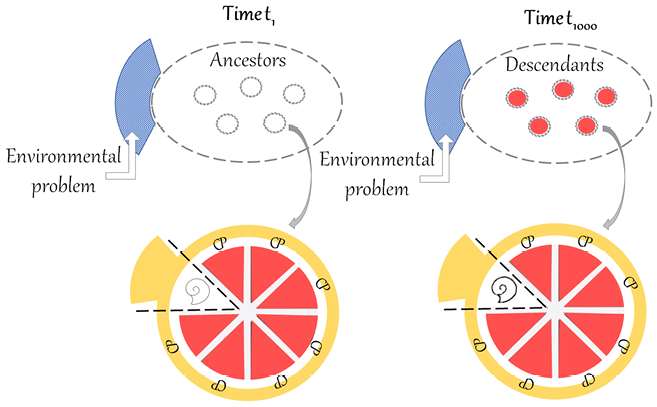

The American palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould has questioned Darwin’s reasoning on organic progress. The core of his criticism can be summed up by saying that natural selection is a mechanism that results in organisms that are adapted to changing local environments. Environments change in a non-directional and unpredictable manner, in line with the principles of Charles Lyell’s geology. Organisms that are not adapted to the new environments are eliminated, and organisms that stay alive are better adapted to local conditions, which can change again and again. In this ‘continuous dance of local adjustment’ (Gould Reference Gould2002, p. 468), the fitness of each organic form is always relative to particular conditions. Let us imagine that we can schematically represent organic forms with ovals and their environment with a rectangle enveloping them, and let us suppose that we can therefore compare the situation at time t1 with the situation at time t1000, as represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Comparison of t1 and t1000, illustrating Gould’s criticism of the incommensurability of organic forms in heterogenous environments. The oval represents organic forms and the rectangle the environment, which is heterogenous from t1 to t1000.

If the rectangle at t1000 is completely heterogenous from the rectangle at t1 (as represented by the different patterns), there is no common background against which organic forms can be compared. If the two situations are incommensurable, it is not legitimate to claim that recent forms are better than ancient ones. With the core of this criticism in mind, let us now examine Gould’s arguments against progress, starting with his texts from the 1980s.

2.4 The Paradox of the First Tier

The theory of punctuated equilibria was first formulated by Gould and Niles Eldredge in Reference Eldredge and Gould1972 (Eldredge and Gould Reference Eldredge and Gould1972) and further developed in the following years (Gould and Eldredge Reference Gould and Eldredge1977, Gould Reference Gould1982). The ways in which this theory dismantles the intuition for progress are made explicit in a text published by Gould in 1985, ‘The Paradox of the First Tier: An Agenda for Paleobiology’ (Gould Reference Gould1985). In this text, Gould proposes considering evolutionary time as structured following three levels or ‘tiers’.

The first tier includes evolutionary events ‘of the ecological moment’ (Gould Reference Gould1985, p. 2): this relates to very short timescales, generally referred to as microevolution.

The second tier refers to ‘trends within lineages and clades that occur during millions of years in ‘normal’ geological time between events of mass extinctions’ (Gould Reference Gould1985, pp. 2–3). For this tier, it is possible to use the term macroevolution.

The third tier is represented by the phenomenon of mass extinctions, whose importance had recently been discovered by palaeobiologists at the time when Gould was writing in 1985. Sometimes the term megaevolution is used to refer to this level (Huneman Reference Huneman, Huneman and Bouton2017).

Gould suggests that the Darwinian tradition – and namely the architects of the Modern Synthesis – deny this hierarchical structure of time by extrapolating from the first tier to the second and third tier. The extrapolation rests on the assumption that causal processes of the first tier (the mechanism of natural selection) can be used to explain what happens at the other tiers. Gould argues that this extrapolation is impossible because each tier has its own causal processes. Palaeobiology must be conceived as an autonomous discipline that studies the second and third tier, decoupling them from the first.

But in what way does this concern progress? Gould claims that the intuition for organic progress is related to the first tier. Darwin expects competitive highness because he is convinced that competition is a main driver of evolutionary change and because he believes that a biomechanical improvement is a way in which organisms adapt to local environments (Gould Reference Gould1985, p. 4). The paradox of the first tier can be described as follows: despite the fact that in theory we should expect organic progress (thus, despite Darwin’s intuition of competitive highness), no clear vector of cumulative progress can be found at larger timescales. In Gould (Reference Gould1985), two solutions are considered to solve this paradox, which I will label respectively ‘no theoretical reasons for progress at the first tier’ and ‘progress is reversed at the second and third tier’.

No theoretical reasons for progress at the first tier. At the short timescales related to the first tier, there are no good theoretical reasons to think that natural selection might cause progress. Darwin’s intuition has no internal foundation in evolutionary theory (it rather comes from a cultural bias).

Progress is reversed at the second and third tier. The theoretical justification for organic progress is valid at the first tier: at short timescales, natural selection may cause something that can meaningfully be called progress. However, this progress is reversed (diluted, undone) by specific processes taking place at the second and, more significantly, third tier.

Gould (Reference Gould1985) explicitly states that he wants to defend the second solution, even though he seems to be sympathetic to the first. Let us consider the two arguments by which Gould argues for the second solution, one relating to the macroevolutionary level, the other to the megaevolutionary level.

The first argument refers to the theory of punctuated equilibria. It is a central theme in Gould’s work that the importance of natural selection has been overestimated by the Darwinian tradition: ‘immediate adaptations of organisms within populations are not the only stuff of long-term evolution’ (Gould Reference Gould1985, p. 6). Gould’s claim is that at the macroevolutionary level there are some distinct causal processes, for example, species selection. The basic idea is that species are not sorted because of competitive success, but rather for properties at the species level, like propensity towards speciation. These complex issues, which I can only evoke here, are still debated today in palaeobiology (Vrba and Lieberman Reference Vrba and Lieberman2005).

The second argument is, as Gould himself admits, the most important one for rejecting the idea of organic progress (Gould Reference Gould1985, p. 7). The phenomenon of mass extinction was well documented from 1980, with the publication of the article ‘Extraterrestrial Cause for the Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction’ by Alvarez, Alvarez et al. (Reference Alvarez, Alvarez, Asaro and Michel1980). This new evidence supported the view that mass extinctions are frequent and rapid phenomena, qualitatively different in rates and effect from other phenomena of the history of life. From this perspective, extinctions are not always competitive replacements, as in a gradualist view of evolution; when mass extinctions occur, species survive or die by chance. In a catastrophic event like the Earth being hit by a meteorite, progress (as defined by adaptations to local environments) is of no utility for organisms.

2.5 Wheels and Wedges

Four years after the publication of ‘The Paradox of the First Tier: An Agenda for Paleobiology’, Gould returned to the question of the relationship between tiers of time and progress in the paper ‘The Wheel of Fortune and the Wedge of Progress’ (Gould Reference Gould1989). Here he insists still further on the megaevolutionary argument: mass extinctions are ‘the wheel of fortune’ that destroy ‘the wedge of progress’. The reference here is to the Darwinian metaphor of the wedge (Stauffer Reference Stauffer1975, p. 208) that would justify the idea of competitive highness. However, Gould’s position with respect to the macroevolutionary argument seems to be different in this paper. Gould appears here more sympathetic to the idea that a few cases of progressive trends can be observed at the macroevolutionary level. This appears clearly in the following passage:

I am persuaded that some cases in Darwin’s preferred mode of organic competition have been documented. Biologist Geerat Vermeij (…), for example, has demonstrated a geological trend for thicker and stronger crab claws matched by ever more efficient defenses (spines, knobs, and thick shells) in the snails that crabs love to eat. I accept the interpretation of this lock-step escalation as an ‘arms race.’

Here Gould refers to the researches of his colleague Vermeij and to his book Evolution and Escalation (Vermeij Reference Vermeij1987). By studying the fossil documentation in marine environments, Vermeij describes an ‘arms race’ between gastropods (prey) and shell-crushing crustaceans (predator). Gould admits that this example can count as a progressive trend, but he argues that we should not over-extrapolate from this because ‘one swallow does not make a spring’:

But (…) a case or two in the fossil record does not establish a pattern. Directional trends produced by wedging do occur, but they scarcely cry for recognition from every quarry and hillslope. The overwhelming majority of paleontological trends tell no obvious story of conquest in competition.

Thus, although a few progressive trends may exist, they do not represent a common pattern. And, even if they exist, mass extinctions could always end them. The history of life is thus reminiscent of the destiny of Sisyphus. Punished in Hades, the king of Corinth is forced to eternally roll a painfully heavy stone up a hill (moment of the wedge of progress through competition), the stone slipping back to the bottom every time he reaches the top (moment of the wheel of fortune that reverses progress) (Gould Reference Gould1989, p. 20).

2.6 No Progress in the Bare Bone Mechanics of Darwinian Theory

Gould returns relentlessly to the issue of progress in two of his books: his widely read Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin, and in his opus magnum, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (Gould Reference Gould2002). As Full House is rather focussed on complexity as a criterion for global progress – an issue that I will discuss in Section 8 – I will here focus on his arguments in the 2002 book and in particular on the interpretation that Gould gives of Darwin’s thought.

According to Gould’s interpretation, Darwin does not have any theoretical basis for defending his reasoning about progress. Darwin ‘stuck’ to progress solely for cultural reasons, related to the importance of the idea (especially when applied to human civilization) in the Victorian society (Gould Reference Gould2002, ch. 6). To do so, Darwin added some supplementary hypotheses to the ‘bare bones mechanics’ of his theory (Gould Reference Gould2002, p. 467). The two hypotheses mutually reinforce each other and can be summed up following the reconstruction of Radick (Reference Radick2000):

Selective factors related to the biotic environments are the most relevant ones in evolutionary processes when compared to causes related to abiotic environments. Here Gould refers to the metaphor of ‘wedges’ used by Darwin (Gould Reference Gould2002, ch. 6).

Independently of the oscillations related to abiotic factors, the Earth is more and more ‘crowded’ over time, thus competition between living forms intensifies.

Two main disagreements can be spotted between Darwin and Gould. First, for Gould, the Darwinian supposition of a stable abiotic environment is unacceptable. For Gould, the history of life undergoes drastic changes in abiotic environments, and species extinctions are mainly related to these events rather than to competitive replacements, as Darwin believes. Second, concerning biotic factors, Gould is sceptical about the idea that competition represents a major phenomenon in evolution. He cites, for example, the ideas of the Russian naturalist and anarchist Peter Kropotkin, according to whom environmental pressures favour intra-specific cooperation rather than competition (Gould Reference Gould2002, p. 471). For Gould, Darwin’s insistence on competition (the intensity of which would be directly proportional to the degree of kinship between individuals) does not have a scientific foundation. It would rather be related to an illegitimate extra-scientific influence connected with societal beliefs.

It should be noted that, in this interpretation, the solution to the paradox of the first tier seems to be ‘no theoretical reasons for progress at the first tier’, rather than ‘progress is reversed or undone at the second and third tier’. In fact, Gould argues here that Darwin’s reference to biotic competition as a main factor in evolutionary processes has an extra-scientific rationale rather than one that is ‘internal’ to evolutionary theory. This would mean that, even at short timescales, the mechanism of natural selection does not cause something that can be called progress.

Considering the different texts, we can say that Gould seems to oscillate between two positions. On the one hand, Gould (Reference Gould1985) and Gould (Reference Gould1989) favour the position ‘progress is reversed or undone at the second and third tier’ (even admitting in 1989 the possibility of some cases of progress at the second tier). On the other hand, although not explicitly argued, the position that there are ‘no theoretical reasons for progress at the first tier’ seems implicit in the interpretation of Darwin’s reasoning in Gould (Reference Gould2002).

2.7 Weighing Up the Two Rival Intuitions

What should we think about Gould’s intuition against organic progress? Should we accept it and consider Darwin’s reasoning on competitive highness as entirely unsound on a theoretical basis? In order to weigh up the two rival intuitions, I will make three remarks as follows.

First, it seems that the most convincing argument proposed by Gould is the one concerning mass extinctions. Since the first proposals on this in the 1980s (Alvarez, Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Alvarez, Asaro and Michel1980), the significance of these phenomena for the history of life has not been questioned. If mass extinctions regularly affect the history of life, then organic traits locally improved by natural selection are useless at the moment of the catastrophe. Hence, with the mass extinctions argument, Gould has shown that it is not possible to argue for organic progress having a global scope (concerning the whole history of life). In the same vein, Huneman (Reference Huneman, Huneman and Bouton2017) has recently suggested that the argument of mass extinctions is related to the contingency thesis (Beatty Reference Beatty1994), proposing that the randomness implied in mass extinctions goes against the possibility of extrapolating from microevolution to macroevolution and megaevolution (‘extrapolationist’ thesis, Huneman Reference Huneman, Huneman and Bouton2017). To sum up, I provisionally concede to Gould that, because of mass extinctions it is not straightforward to argue for progress at a global scale (but see Section 8 for a proposal of a promising candidate for global progress).

Second, a major question is opened by Gould’s reasoning. If organic progress having a global scope seems untenable, what about progress having a local scope, concerning short timescales? After all, we could consider that an improvement, even though it is undone at a later time, would still significantly count as an improvement in a given temporal interval. To modify Gould’s metaphor, we could think that Sisyphus has somehow advanced into a ramp phase, although his efforts are then subsequently nullified.

Third, Darwin’s intuition seems to rely on the fact that natural selection conceptually implies some kind of improvement. However, as formulated by Darwin, the reasoning for this raises various difficulties. As already mentioned, it is unclear which kind of organic forms Darwin is considering in the comparison between extant and ancient forms. In fact, it seems quite odd to compare a whole extant organic community (e.g., the whole extant Australian fauna) with a whole Eocene organic community (e.g., the whole Eocene Australian fauna). If this is what Darwin means, this is subject to the following objection: the extant organic community is adapted to its life conditions just as the ancient organic community was adapted to their own life conditions. As they are incommensurable, it is impossible to say that the recent one is better than the ancient. This leads us back to the problem raised with Figure 1. Is postulating the clause ‘under a nearly similar climate’ sufficient for defending his position?

In view of these three remarks, my proposal is as follows. Let us provisionally concede to Gould that, because of mass extinctions, it is not straightforward to argue for progress at a global scale. I thus suspend the judgement – applying a sort of sceptical epoché – and return to this issue in Section 8. For now, I propose giving Darwin’s intuition a chance, at least as far as organic progress with a local scope is concerned. Although Darwin’s reasoning presents several difficulties, let us consider the idea that drives his intuition: evolutionary theory conceptually implies that – under some circumstances – some kind of organic improvement can occur. Further, I attempt to give a clear and sound meaning to this idea as far as small timescales are concerned, drawing on the ideas of Richard Dawkins and then refining his notion.

3 Dawkins’ Account of Local Progress

3.1 Giving Darwin’s Intuition a Chance

To give Darwin’s intuition a chance, at least two issues need to be clarified.

First, clarification is needed concerning the scope of progress. What does local progress mean exactly? On the one hand, we could ask whether it is legitimate to compare Eocene forms with recent forms, as Darwin does in his thought experiment. This question refers to the restriction of temporal scale. On the other hand, we could ask which organisms can be compared at t1 and t1000. For example, are we making intra-specific comparisons, for example, comparing ancestors and descendants within the same lineage? Or are we rather referring to inter-specific comparisons, which would allow us to claim that a particular organic form X is better than a very different organic form Y?

Second, the criterion (or criteria) of improvement needs to be clarified. Admitting that ‘better’ organisms have a competitive advantage, do we think that this advantage is related to any specific organic property (e.g., complexity or intelligence) or might it be related to different properties? In this section, I try to clarify these issues by drawing on the ideas of Dawkins.

Richard Dawkins is a British biologist and ethologist. Along with Gould, he significantly contributed to popularizing evolutionary theory in the twentieth century. While the two biologists are on the same side in the defence of evolutionary theory with respect to creationism, they disagree on several major points regarding the interpretation of Darwinism (Shanahan Reference Shanahan and Delisle2017). After the publication of Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin (Gould Reference Gould1996), Dawkins wrote a review of Gould’s book, titled ‘Human Chauvinism’ (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1997). Dawkins states that Gould’s definition of progress in this book is a human-chauvinistic one, which makes it ‘too easy to deny progress in evolution’ (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1997, p. 1016). In fact, Gould’s treatment of progress in this large-audience book is quite different from the arguments that I have outlined in the previous section. In Full House, Gould mainly refers to progress as a tendency to increase relative to some criterion (e.g., anatomical complexity and neurological elaboration) concocted by human beings to place themselves ‘atop a supposed heap’ (Gould Reference Gould1996, p. 20). Dawkins proposes an alternative definition of progress, which he claims to be ‘less anthropocentric’ and ‘more biologically sensible’ (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1997, p. 1016); I will examine this further.

3.2 The Adaptationist Criterion of Local Progress

First, Dawkins suggests that the criterion for organic progress should not be related to the same property for all lineages, like for example complexity of intelligence. Improvements could occur in different lineages, but they might not be related to the same property in all of them. As Dawkins states:

This [my adaptationist definition of progress] (…) takes progress to mean an increase, not in complexity, intelligence or some other anthropocentric value, but in the accumulating number of features contributing towards whatever adaptation the lineage in question exemplifies.

Hence, for Dawkins, there is no single property related to Darwinian ‘competitive highness’. Organisms can accumulate ‘features’ that contribute to adaptation, but these do not have to be the same for the different lineages. Dawkins’ intuition presents some similarities with Darwin’s intuition. In both cases, the biotic aspect of selection is considered to be predominant over the abiotic aspect: Dawkins refers to the idea of an ‘arms race’ occurring among organisms (Dawkins and Krebs Reference Dawkins and Krebs1979). However, Dawkins also adds some important points to Darwin, which I think can be summed up as three main points:

The ‘equipment for survival’ gets better.

Comparisons are limited to ancestors-descendants within a lineage.

Organic progress takes place from short to medium term.

Let us start with the first point about the equipment for survival: Dawkins’ claim is not that more recent organisms ‘survive better’. As Dawkins puts it:

The participants in the race do not necessarily survive more successfully as time goes by – their “partners” in the coevolutionary spiral see to that (the familiar Red Queen Effect). But the equipment for survival, on both sides, is improving as judged by engineering criteria. In hard-fought examples we may notice a progressive shift in resources from other parts of the animal’s economy to service the arms race (Dawkins and Krebs Reference Dawkins and Krebs1979). And in any case the improvement in equipment will normally be progressive.

For Dawkins, what gets better is the ‘equipment for survival’, as judged by ‘engineering criteria’.

Second, Dawkins clarifies the Darwinian thought experiment regarding progress. In fact, the father of evolutionary theory does not clearly state which kinds of organisms are considered in the comparison. An example by Dawkins suggests that the comparisons concern traits of the same lineage, for example, the eyes in vertebrates. In Dawkins’ example, the initial eyes of earlier vertebrate ancestors are compared with the better-performing eyes of vertebrate descendants (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1997, p. 1018). By considering this branch of the tree of life, we can say that an improvement took place relative to the function of vision. However, continuing Dawkins’ line of reasoning, it seems less straightforward to compare the vertebrate eyes and the invertebrate eyes (e.g., bivalves’ ocelli, structures for perceiving light).

Third, Dawkins is more explicit than Darwin about the temporal scale of the comparison: he admits that progress only makes sense in the short to medium term.

Coevolutionary arms races may last for millions of years but probably not hundreds of millions. Over the very long timescale, asteroids and other catastrophes bring evolution to a dead stop, major taxa and entire radiations go extinct (…) The several arms races between carnivorous dinosaurs and their prey were later mirrored by a succession of analogous arms races between carnivorous mammals and their prey. Each of these successive and separate arms races powered sequences of evolution which were progressive in my sense. But there was no global progress over the hundreds of millions of years, only a sawtooth succession of small progresses terminated by extinctions. Nonetheless, the ramp phase of each sawtooth was properly and significantly progressive.

Thus, Dawkins concedes that Gould is right in his argument that mass extinctions undo progress at long temporal scales. However, he claims that we can meaningfully speak of organic progress at short and medium timescales, taking adaptation as a criterion (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1997, p. 1016).Footnote 4

These three points make it clear that the notion of organic progress that Dawkins defends is narrow and only applicable at a local scale. I will refer to this notion as the Dawkins notion of local progress.

3.3 Clarifying Dawkins’ Notion of Local Progress

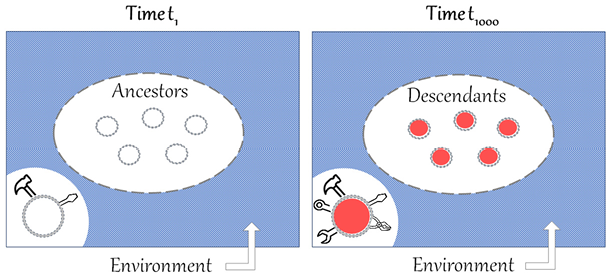

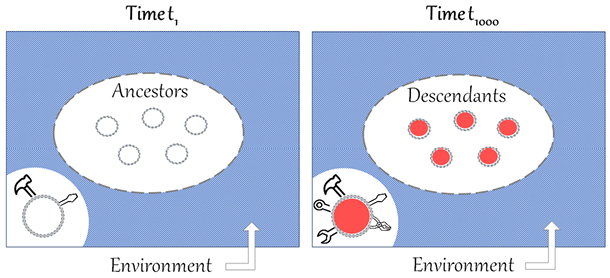

It can be useful to visualize Dawkins’ notion of local progress, as in Figure 2, and compare it to Figure 1.

Figure 2 Comparison of t1 and t1000, illustrating Dawkins’ account of local progress. The ovals represent populations of ancestors and descendants of the same lineage, the circles represent individual organisms of the populations and the rectangles represent the environment. The environment is supposed to be homogenous because the timespan between t1 and t1000 only represents short to medium timescales. Due to competition, the population of descendants would present a better ‘equipment for survival’ than the population of ancestors, here represented by a richer ‘toolkit’.

First, in Figure 2, the meaning of the ovals is clarified. They no longer represent generic organic forms, but rather an ancestor population at t1 and a descendant population at t1000, belonging to the same lineage. I suggest further representing individual organisms of the two populations as circles within the ovals. Second, another important difference in Figure 2 is that the environment is supposed to be homogenous at t1 and t1000 because the timespan only represents short to medium timescales. Finally, for Dawkins, what differentiates organisms at the two different times is the ‘equipment for survival’. For the moment, let us visually represent this difference with a richer ‘toolbox’ in the descendant population (see Section 6 for further clarification).

It should be stressed that, for Dawkins, evolutionary theory conceptually implies local progress. His reasoning can be described as consisting of two premises and a conclusion:

P1: Evolutionary theory conceptually implies the possibility that the process of adaptation by natural selection takes place.

P2: The process of adaptation by natural selection conceptually implies local progress.

C: Evolutionary theory conceptually implies the possibility of local progress.

The first premise is commonly accepted among evolutionary biologists. But what kind of explanation do we have for the existence of specialised morphological structures? Dawkins has in mind here the kind of biological cases that had already surprised Darwin, where biological structures give a strong impression of ‘tight correspondence’ or ‘fine tuning’ with the surrounding environment, as with the vertebrate eyes, the echolocation in bats and dolphins, and the sophisticated adaptations of orchids (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1997, p. 1018). If these specialized morphological structures are our explanandum, the most plausible explanans is that the process of adaptation by natural selection took place. Otherwise, we should assume that these structures appeared suddenly after one large mutation, which seems counterintuitive (and leaves space for creationist objectionsFootnote 5). Dawkins claims that even Gould should admit this is the only possible explanans.

According to the second premise, the process of adaptation by natural selection conceptually implies that some improvement occurs. It does not matter if this improvement is local and is ‘undone’ at a long temporal scale; it can nonetheless be labelled improvement, thus legitimating discussions of progress. As Dawkins puts it, we should admit this adaptationist notion of progress ‘without stirring from our armchair’ (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1997, p. 1018).

By this definition, adaptive evolution is not just incidentally progressive, it is deeply, dyed-in-the-wool, indispensably progressive. It is fundamentally necessary that it should be progressive if Darwinian natural selection is to perform the explanatory role in our world view that we require of it, and that it alone can perform.

Yet, the second premise of the reasoning (P2) is much more controversial, as I will now explain.

3.4 An Unanswered Question in Dawkins’ Account

Dawkins presents some ways of making Darwin’s intuition about progress much more precise, that is, the three main points discussed earlier. However, his reasoning relies on the acceptance of the second premise, according to which the process of adaptation by natural selection conceptually implies local progress.

The controversial point is as follows: local progress refers to the notion of ‘betterment’, which in turn presupposes the notion of ‘good’. But are these normative terms acceptable within a scientific theory? Are we not supposed to remain in the factual or descriptive realm, instead of the normative realm? Defenders of the value-free ideal of science might raise the objection that these terms are unacceptable in a scientific discipline. They may claim that evolutionary biology should be purged from terms such as ‘progress’ (as well as ‘teleology’ and ‘goal-directedness’) because they could damage the professional image of the discipline (McShea Reference McShea2023). I will try to argue that, if the precise meaning of normative terms is made explicit, they do not represent a problem in this sense. The next section will be devoted to tackling this point.

4 Normative Terms within Evolutionary Biology

4.1 Rosenberg and McShea’s Framework

In philosophy, it is common to distinguish what is normative from what is non-normative (i.e., natural or descriptive). Normative terms include good, bad, right, wrong, and mandatory. By contrast, examples of non-normative terms are blue, red, round, small, big, light, and heavy. The domain of philosophy that is especially concerned with normative terms is moral philosophy, dealing with what is generally categorized as axiological (referring to values) or deontic (referring to norms, e.g., what is permitted and required). So how could there possibly be normative terms in evolutionary biology?

In the context of their discussion of organic progress, Rosenberg and McShea (Reference Rosenberg and McShea2008) provide a useful framework for understanding in what sense value attributions are relevant to evolutionary biology. The authors start by identifying two ways in which the normative component of organic progress could be understood:

Now there are two ways in which an increase in some feature of organisms might be valuable. The feature could be valuable to us, to human beings. Or it could be valued by the evolutionary process, so to speak, valued in the sense of preserved or enhanced owing to its adaptive value, the contribution it makes to survival and reproduction. The more progressive organism could be the one that is better at surviving and reproducing, the one that is more fit, so that progress would be an increase in whatever features of organisms underlie increased fitness, over the history of life.

The first option is to consider the feature in question as valuable for human beings. This is considered problematic by virtue of the value-free ideal: human values should not be relevant ‘to the findings of science or to the process of determining what is true’ (Rosenberg and McShea Reference Rosenberg and McShea2008, p. 129). Thus, the authors propose examining the second option, ‘valued in the sense of preserved or enhanced owing to its adaptive value’. Here they introduce the distinction between ‘intrinsic’ and ‘instrumental’ value. Typically, the distinction refers to something to which one could attribute a value ‘in itself’ (e.g., friendship, happiness), as opposed to something that is only valuable as a means to something else (e.g., money). The opposition between intrinsic and instrumental value is classically introduced while discussing moral issues, although it has been noted – mainly by Korsgaard (Reference Korsgaard1983) – that the distinction can be misleading.Footnote 6 Intrinsic value is an especially important concept in axiology, although the questions ‘what is intrinsic value’ and ‘what has intrinsic value’ are far from having simple and uncontested answers. Some authors have even raised the question of whether intrinsic value exists at all (Zimmerman and Bradley Reference Zimmerman, Bradley, Zalta and Nodelman2019, Section 2).

Rosenberg and McShea claim that the value referred to in evolutionary biology is instrumental. If one argues that one item is better than another for achieving a purpose, the term ‘better’ is being used instrumentally. This is first illustrated by a technical example: ‘an electron microscope is better than a light microscope for the purpose of seeing the very small details of certain objects’ (Rosenberg and McShea Reference Rosenberg and McShea2008, p. 129). The axiological term ‘better’ here refers to the specific purpose of seeing small details. This has no implication for the question of whether an electron microscope is valuable in itself, in absolute terms. For Rosenberg and McShea, this would be a matter of moral or ethical value.

Then, by analogy, the authors apply the same distinction to a biological case:

Switching to a biological example, the theory of natural selection identifies the thick coat of the polar bear as instrumentally valuable for insulation, and insulation as instrumentally good for survival and reproduction. But science stops at this point. It does not identify some further good for which survival and reproduction are instrumentally valuable. Nor does it suggest that survival and reproduction are intrinsically good in themselves. It is silent on this matter owing to its value neutrality.

The authors claim that statements about instrumental value are ‘essential’ in evolutionary biology, while they make no reference to intrinsic value. They specify that the difference between the two can be made by virtue of the fact that instrumental value is subject to empirical testing once we stipulate the criteria of goodness we have in mind (e.g., efficiency and speed). By contrast, there is no test or experiment that would enable us to settle disputes over intrinsic value (Rosenberg and McShea Reference Rosenberg and McShea2008, p. 130).

By analysing the example used by Rosenberg and McShea, we can identify two kinds of axiological statements (see De Cesare Reference De Cesare2019):

(i) A thick coat is instrumentally good for the polar bear to achieve the particular organic purpose of keeping its body warm.

(ii) Keeping the body warm is instrumentally good for the polar bear to achieve the general organic purpose of survival and reproduction.

By generalizing the example, we obtain:

(i) An organic trait (x) is instrumentally good for an organic entity (O) to achieve the particular organic purpose P.

(ii) The particular organic purpose (P) is instrumentally good for an organic entity (O) to achieve the general organic purpose of survival and reproduction (P*).

I suggest calling this kind of value ‘organic value’. This requires further clarification comprising two points, which are presented as follows.

4.2 Two Remarks Concerning the Framework

First, the attribution of the instrumental value of a means does not imply the value of the end itself. Referring to P*, Rosenberg and McShea explicitly state that there is no need to attribute value to survival and reproduction. In fact, science ‘does not identify some further good for which survival and reproduction are instrumentally valuable’ (Rosenberg and McShea Reference Rosenberg and McShea2008, p. 129). Indeed, this position would lead to the strong metaphysical thesis that ‘life’ and ‘reproducing life’ are better than death. However, it should be noted that this end P*, even if it does not need to be value-laden, has a particular status of being the ‘endpoint’ of instrumental value attributions. One could argue that there are good reasons why biologists are particularly interested in what contributes to organisms’ survival and reproduction. In fact, organisms that are good with respect to survival and reproduction are expected to be (except in the case of unlucky catastrophic events) those that leave descendants and ‘go through’ evolutionary history. To explain why extant organisms are there and present certain characteristics, we might refer to the fact that ancestors in the lineage must have been ‘good enough’ at surviving and reproducing.

Second, with organic value, we find ourselves in a specific part of the normative realm, where objective assessments about what is better or worse relative to a specific purpose are possible. Once again, the notion of organic value does not imply any ethical considerations. The distinction between the goodness that is implied in the case of organic value versus goodness ‘as an end’ might be clarified by drawing on an insight from Ludwig Wittgenstein. In his Lecture on Ethics, Wittgenstein (Reference Wittgenstein1929) presents two kinds of goodness and discusses what is valued as a means under the label of ‘relative good’. He describes it as follows:

If for instance I say that this is a good chair this means that the chair serves a certain predetermined purpose and the word good here has only meaning so far as this purpose has been previously fixed upon. In fact the word good in the relative sense simply means coming up to a certain predetermined standard. Thus when we say that this man is a good pianist we mean that he can play pieces of a certain degree of difficulty with a certain degree of dexterity. (…) Used in this way these expressions don’t present any difficult or deep problems.

However, Wittgenstein argues that the kind of ‘good’ that is interesting in ethics is not this relative good, but rather absolute good. For example, in the statement ‘this is the right way to Granchester’ the reference is to relative good. Instead, if we speak of the ‘right road’, this would be ‘the road which everybody on seeing it would, with logical necessity, have to go, or be ashamed for not going’ (Wittgenstein Reference Wittgenstein1929). The difference can be spotted because, contrary to judgements about absolute value, judgements about relative value can be translated in descriptive terms:

Every judgment of relative value is a mere statement of facts and can therefore be put in such a form that it loses all the appearance of a judgment of value: Instead of saying “This is the right way to Granchester,” I could equally well have said, “This is the right way you have to go if you want to get to Granchester in the shortest time”; “This man is a good runner” simply means that he runs a certain number of miles in a certain number of minutes, etc.

Wittgenstein’s idea is that it is possible to translate statements implying relative value into factual terms. I think that this insight nicely complements a point by Rosenberg and McShea concerning organic value, according to which it is possible to empirically test statements about instrumental value. In brief, it is possible – at least in principle – to objectively assess that one jaguar is better than another jaguar if I decide to focus on the activity of running fast. In the same way, it is possible to assess which is the best road to get to Granchester with respect to the purpose of reaching Granchester in the shortest time. Note that, in both cases, the result of the test might change if I ‘set’ the purpose differently: for example, for jaguars, by focussing on the most effective technique for capturing prey; or, for roads, reaching Granchester while enjoying the nicest view. However, once the purpose is clearly identified, the relative good in the statements becomes empirically testable.

Thus, this notion of relative good refers to a specific domain within the normative realm, where it is possible to assess that ‘x is better than y for P’ without appealing to subjective appreciations. Despite the use of normative terms, it is possible at least in principle to refer to something objective, for example, assess the better jaguar with respect to running fast, or assess the better road with respect to arriving in Granchester as soon as possible.

4.3 An Objection: Can We Speak of Means for a Purpose within Biology?

I have defended the idea that, with the framework of Rosenberg and McShea, we have a coherent notion of organic value. However, an objection might be raised here. As I have presented it so far, the notion of instrumental organic value speaks of good/bad means towards some ‘end’. However, the terminology referring to purposes within biology might be accused of being finalistic, and thus unacceptable. This objection, which could be labelled the anti-teleological objection to organic value, has some strong historical roots, which are worth sketching briefly, partly following Colin and Neal (Reference 77Colin, Neal and Zalta2020).

It is a cornerstone idea of modern science that final causes should be entirely banished. With respect to the study of living beings, this position comes in opposition to ancient authors such as Aristotle and Galen, for whom biological explanation cannot be purely mechanistic. For example, it is impossible to explain an organ (e.g., the heart) without considering its organic purpose (‘telos’) or function within the organism. However, these influential views were strongly challenged during the scientific revolution starting from the sixteenth century. The use of mechanical analogies to explain living entities has become dominant (e.g., in the work of Harvey and Descartes) and Francis Bacon clearly banished final causes from scientific methodology.

At the end of the eighteenth century, this issue was famously discussed in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment (Kant Reference Kant1790 [2000]). Kant claims that humans unavoidably understand living beings, with their unique capacity to grow and reproduce, as being purposive. Can this purposiveness be reduced to causal-mechanistic explanations? Commenting on Kant, Ginsborg (Reference Ginsborg, Zalta and Nodelman2022) nicely explains the intricacy of this issue:

The mechanical inexplicability of organisms leads to an apparent conflict, which Kant refers to as an ‘antinomy of judgment’, between two principles governing empirical scientific enquiry. On the one hand, we must seek to explain everything in nature in mechanical terms; on the other, some objects in nature resist mechanical explanation and we need to appeal to teleology in order to understand them (§70, 387).

Some authors have interpreted Kant’s position on teleology as denying the possibility of biology as a causal science,Footnote 7 but see Teufel (Reference Teufel, Smith and Nachtomy2013) for a criticism of this interpretation. It should also be noted that the debate on how to interpret Kant’s legacy on the issue of teleology and biology is far from closed. A recent paper by Gambarotto and Nahas (Reference Gambarotto and Nahas2022) presents the debate in the following terms. Kant claims that we need to appeal to teleology to understand organic entities. But should we consider teleological explanations simply as heuristic tools? Or should we rather think that purposiveness is an intrinsic feature of biological systems? Gambarotto and Nahas (Reference Gambarotto and Nahas2022) label these approaches as heuristic and naturalistic, respectively.Footnote 8

However, let us go back to the brief historical sketch, and particularly to the context into which Darwin builds his view of evolution. Although his direct knowledge of Kantian philosophy was not ‘necessarily great’ (Stowell Reference Stowell2024, p. 523), Darwin probably knew about Francis Bacon’s negative assessment of final causes via the British philosopher William Whewell (Ruse Reference Ruse1975). Darwin was aware that, in a Baconian perspective, the standards of scientific methodology set by modern physics would require the banishment of final causes. However, interestingly, Darwin sometimes refers to purposes and ‘final causes’, while admitting in a personal note: ‘it is anomaly in me to talk of Final Causes: consider this!’ (cited in Lennox Reference Lennox1993, p. 411).

Does Darwinian theory reject teleology or not? When Origin was published in 1859, Darwin’s contemporaries considered him either as a teleologist or a non-teleologist, either with praise or blame (Lennox Reference Lennox1995). It is well known that Darwin’s intention was to explain organic features without appealing to the design of a benevolent creator, who would have intentionally created a feature to fit a purpose. This kind of divine purpose, at the core of natural theology of William Paley, is banished by Darwin. Still, does this mean that Darwin barred all kinds of teleology from evolutionary theory? Scholars disagree on this point. Micheal Ghiselin answers with an affirmative, claiming that Darwin purged biology from teleology (Ghiselin Reference Ghiselin1994), while James G. Lennox defends the idea that Darwin ‘re-invented teleology’, a selection-based teleology (Lennox Reference Lennox1993).

Alongside these divergencies on the interpretation of Darwin’s thought, the contemporary debate about the legitimacy of teleological notions in evolutionary biology is far from closed (Colin and Neal Reference 77Colin, Neal and Zalta2020). One of the main things that bothers the ‘anti-teleologists’ is that referring to purposes would be anthropomorphic. As human beings are purposive, they would be led to attribute purpose where there is none (Colin and Neal Reference 77Colin, Neal and Zalta2020). Moreover, they claim that there is no need to appeal to purposes if we can explain biological organisms in the same way that we explain physical objects: by identifying causes and effects. Rather than saying that X achieves a purpose, we can simply say that X causes an effect.

After having outlined the historical roots of the anti-teleological objection, I will try to respond to the criticism. The aim is to show that the objection does not dismantle the notion of organic value that I have previously presented.

4.4 First Step to Answering the Objection: Clarifying Teleology within Biology

First, let us clarify what teleology within biology is not. It is possible to exclude from the outset any notions of intentional design, spirit or entelechy, which would carry a strong metaphysical element, widely rejected in modern science (McShea Reference McShea2023). Drawing on McShea’s reflection, it is possible to distinguish two ways in which teleology comes into play in biology:

Concerning the evolutionary process. This question is about large-scale evolutionary trends. At the scale of lineages, is there a sense in which evolution is somehow goal-directed? This is the main issue discussed by McShea (Reference McShea2023).

Concerning the results or outcomes of the evolutionary process, that is, characteristics of organismal structures or behaviours. Consider the example of a bird’s behaviour of migrating south for the winter. Is the bird’s behaviour goal-directed?

Orthogonal to this distinction, I propose identifying several attitudes towards teleology within biology:

Teleology eliminativism. In looking at both processes and outcomes, biology should be teleology-free and only deal with mechanisms.

Weak defence of teleology – heuristic approach. In the biological disciplines, from an epistemic perspective, we need teleological explanations. This position, corresponding to the heuristic interpretation of Kant on teleology (Gambarotto and Nahas Reference Gambarotto and Nahas2022), equates to saying that we need to appeal to teleology in our way of understanding the organic world. This might include processes and/or outcomes. However, this position would not necessarily imply the ontological affirmation according to which there is purposiveness outside human minds.

Strong defence of teleology – naturalistic approach. Biological objects, whether processes or outcomes, are ontologically teleological. This idea corresponds to what Gambarotto and Nahas (Reference Gambarotto and Nahas2022) call the naturalistic interpretation of Kant on teleology. This can be applied either to the processes (there is some kind of goal-directedness in large-scale evolution) or to results (there is some kind of goal-directedness in organic features, be this in structure, organization or behaviours). According to this view, there is purposiveness independent of the human mind.

It would be interesting to analyse these three possible attitudes and confront them with the effective positions that can be found in the literature on teleology in biology, but this is not the aim of the current work. The question here is rather: what is the minimal notion of teleology (Pérez-Escobar Reference Pérez-Escobar2024) that we need to defend in order to secure the notion of organic value?

Recall the two kinds of statements implying organic value:

(i) An organic trait (x) is instrumentally good for an organic entity (O) to achieve the particular organic purpose P.

(ii) The particular organic purpose (P) is instrumentally good for an organic entity (O) to achieve the general organic purpose of survival and reproduction (P*)

To secure the notion of organic value, it is necessary to make sense of ‘organic purpose’ with reference to organismal activities, for example, flying or surviving. Thus, I am interested here in defending the idea that it is meaningful to speak of purposes concerning the outcomes of the evolutionary process, that is, living beings.

This being said, making sense of purposes can be done in several ways. It is possible to criticise teleology eliminativism, for example, by claiming that appealing to mechanisms is as anthropomorphic as appealing to purposes (Canguilhem Reference Canguilhem1952). It is also possible to adopt a strong defence and argue that, ontologically, organisms are goal-directed. This characteristic could be claimed to have internal sources, for example by drawing on an organizational account of teleology (Mossio and Bich Reference Mossio and Bich2017, Bich Reference Bich2024). Or it could be argued that teleology has external sources, as put forward by McShea (Reference McShea2023) in his novel account based on field theory.

Although I think there are good arguments for both criticising eliminativism and for defending the strong option of teleology, I will here stick to the weak option and argue for it by drawing on Lennox and Kampourakis (Reference Lennox, Kampourakis and Kampourakis2013).

4.5 Second Step in Answering the Objection: Functional Explanations for Organisms Imply an Axiological Polarity

A mountain’s slope can have a causal impact on rainfall. A bird’s wing, and an aeroplane’s wing, can have a causal action on flight (Lennox and Kampourakis Reference Lennox, Kampourakis and Kampourakis2013). What is the difference between these cases?

All of the cases can be understood as identifying a cause and an effect. However, the case of the bird and the aeroplane share a commonality that is not present in the case of the mountain. In both the organic and technical cases, the effect of ‘flying’ plays a particular role. Flying contributes to explaining why, over history, birds and aeroplanes came to present the structural feature of having wings. By contrast, in the case of inorganic entities, we do not appeal to the rainfall to explain the mountain’s slope.

However, as Lennox and Kampourakis (Reference Lennox, Kampourakis and Kampourakis2013) emphasize, we should also note an important difference between organisms and artefacts. In the case of artefacts, it is a conscious agent who identifies the most appropriate wing design, while in the biological case it is the unconscious process of natural selection. In biology, design-based teleological explanations are inappropriate because they appeal to the intention of a supernatural creator. On the other hand, natural selection-based teleological explanations are appropriate, referring to an unintentional process (the mechanistic ‘filtering’ by natural selection).

Despite this relevant difference, we are in the same situation for organisms and artefacts: we need teleological explanations in the sense of Larry Wright’s conception of teleological explanation, that is, consequence aetiology (Wright Reference Wright1976). According to this conception, a teleological explanation is one in which the presence of x (a property, process or entity) can be explained by appealing to a result or consequence that x brings about. Such teleological explanations can be presented by referring to the concept of function. Bird and aeroplane wings are said to have the function of flight, but a mountain’s slope does not have the function of producing rainfall, just the effect of producing rainfall.

In the past half century, the literature on teleology in biology has focussed on the concept of function (McShea Reference McShea2023). The debate has been structured around two contributions from the 1970s by the philosophers Larry Wright and Robert Cummins (Gayon and Petit Reference Gayon and Petit2018, p. 155). Wright (Reference Wright1973) provides the origin of etiological approaches of function, proposing a focus on the history of traits – whether they are organic traits or technological artefacts. Starting from Wright’s proposition, Karen Neander (Neander Reference Neander1991) proposes the following definition: a trait’s function is the effect for which this trait has been selected over evolutionary history. Opposing the idea that historical considerations are pertinent in defining function, Cummins (Reference Cummins1975) proposes the thesis that something has a function if it has a causal role within a system. Alongside the etiological and systemic accounts of function, a third approach can be distinguished (Wouters Reference Wouters2003): the life chances approach (e.g., Bigelow and Pargetter Reference Bigelow and Pargetter1987). According to this approach, functions are considered as the effects that enhance the chances of survival in those that bear them.

Regardless of the specific account that one prefers, there is a general feature that is common in functional language: claiming that x has a function implies that x can dysfunction. This normative dimension gives the functional discourse an axiological polarity. Trait x is supposed to do something. If it can do that effectively, it is functional; if not, it is dysfunctional. George Gaylord Simpson expresses a similar view about the relationships between function and organic goodness in Simpson (Reference Simpson and Tax1960) and (Reference Simpson1974) (see also De Cesare Reference De Cesare2019).

Thus, let us return to our statements about organic value and transform them in the following way: