1. Introduction

1.1. Modelling surface roughness in a transitionally rough regime

Flows over rough surfaces are critically important due to their extensive engineering applications. However, with the multitude of roughness topographies and the prohibitive costs associated with testing each of the surfaces, the accurate understanding of flow modifications and the prediction of the drag caused by the rough surfaces remain an important challenge. The uncertainties stemming from the limited knowledge of flow modifications due to rough surfaces and unreliable drag predictions result in significant financial losses, amounting to billions of dollars annually (Schultz et al. Reference Schultz, Bendick, Holm and Hertel2011; Stevens & Meneveau Reference Stevens and Meneveau2017; Chung et al. Reference Chung, Hutchins, Schultz and Flack2021). Consequently, an increasing number of numerical studies focus on rough-wall bounded turbulent flows. An approach is to consider the full geometry of the rough surfaces, so that all essential small-scale flow characteristics are captured (e.g. Leonardi et al. Reference Leonardi, Orlandi, Smalley, Djenidi and Antonia2003; Orlandi, Leonardi & Antonia Reference Orlandi, Leonardi and Antonia2006; Forooghi et al. Reference Forooghi, Stroh, Schlatter and Frohnapfel2018; Abderrahaman-Elena, Fairhall & García-Mayoral Reference Abderrahaman-Elena, Fairhall and García-Mayoral2019).

However, resolving the full texture of rough surfaces using direct numerical simulations (DNS) is prohibitively expensive. Another approach taken in the past is therefore based on the characterisation of the effects of rough surfaces by focusing on physically meaningful flow parameters rather than delving into the intricate details of the flow within the textured region. This is particularly useful for the low to intermediate range of transitional roughness (

![]() $5 \leqslant k_s^+ \leqslant 20$

, where

$5 \leqslant k_s^+ \leqslant 20$

, where

![]() $k_s^+$

is the equivalent sand-grain roughness, with the superscript

$k_s^+$

is the equivalent sand-grain roughness, with the superscript

![]() $+$

denoting the viscous inner scaling), in which changes in drag are primarily a consequence of the viscous modifications induced by the surface roughness. In doing this, the concepts of ‘protrusion height’ and ‘slip length’ were introduced. Bechert & Bartenwerfer (Reference Bechert and Bartenwerfer1989) observed a mean longitudinal flow over the riblet from a depth beneath the riblet tips, and called this distance from the riblets tips the ‘protrusion height’. Luchini, Manzo & Pozzi (Reference Luchini, Manzo and Pozzi1991) subsequently observed that the protrusion height of the cross-flow over the riblets was smaller than that of the longitudinal flow, with their resulting difference characterising the variations in drag. The ‘slip lengths’ have proven to be useful in modelling the effects of superhydrophobic surfaces on turbulent flows using the Navier slip boundary conditions (e.g. Lauga & Stone Reference Lauga and Stone2003; Min & Kim Reference Min and Kim2004; Busse & Sandham Reference Busse and Sandham2012; Fairhall, Abderrahaman-Elena & García-Mayoral Reference Fairhall, Abderrahaman-Elena and García-Mayoral2019). Later, it was established that the protrusion heights and slip lengths are conceptually equivalent (Luchini Reference Luchini2015; Garcia-Mayoral et al. Reference García-Mayoral, Gómez-de-Segura and Fairhall2019).

$+$

denoting the viscous inner scaling), in which changes in drag are primarily a consequence of the viscous modifications induced by the surface roughness. In doing this, the concepts of ‘protrusion height’ and ‘slip length’ were introduced. Bechert & Bartenwerfer (Reference Bechert and Bartenwerfer1989) observed a mean longitudinal flow over the riblet from a depth beneath the riblet tips, and called this distance from the riblets tips the ‘protrusion height’. Luchini, Manzo & Pozzi (Reference Luchini, Manzo and Pozzi1991) subsequently observed that the protrusion height of the cross-flow over the riblets was smaller than that of the longitudinal flow, with their resulting difference characterising the variations in drag. The ‘slip lengths’ have proven to be useful in modelling the effects of superhydrophobic surfaces on turbulent flows using the Navier slip boundary conditions (e.g. Lauga & Stone Reference Lauga and Stone2003; Min & Kim Reference Min and Kim2004; Busse & Sandham Reference Busse and Sandham2012; Fairhall, Abderrahaman-Elena & García-Mayoral Reference Fairhall, Abderrahaman-Elena and García-Mayoral2019). Later, it was established that the protrusion heights and slip lengths are conceptually equivalent (Luchini Reference Luchini2015; Garcia-Mayoral et al. Reference García-Mayoral, Gómez-de-Segura and Fairhall2019).

The concepts of protrusion height and slip length are primarily used to model the effect of the roughness texture on the velocity components parallel to the wall combining with the Navier slip boundary conditions. However, by construction, they do not appropriately capture the wall-normal momentum transport (Gómez-de-Segura et al. Reference Gómez-de-Segura, Fairhall, MacDonald, Chung and Garcia-Mayoral2018; Bottaro Reference Bottaro2019; Zampogna, Magnaudet & Bottaro Reference Zampogna, Magnaudet and Bottaro2019). To address this limitation, the transpiration-resistance model (TRM) for boundary conditions was recently proposed by Lācis et al. (Reference Lācis, Sudhakar, Pasche and Bagheri2020) and subsequently applied to turbulent flows over rough surfaces (Sudhakar et al. Reference Sudhakar, Lācis, Pasche and Bagheri2021; Khorasani et al. Reference Khorasani, Lācis, Pasche, Rosti and Bagheri2022). The TRM boundary conditions integrate the slip conditions for the wall-parallel velocity components with a transpiration condition for the wall-normal velocity, so that the changes in wall-normal velocity are coupled to the shear variations of the other two velocity components (Lācis et al. Reference Lācis, Sudhakar, Pasche and Bagheri2020). Furthermore, both Lācis et al. (Reference Lācis, Sudhakar, Pasche and Bagheri2020) and Sudhakar et al. (Reference Sudhakar, Lācis, Pasche and Bagheri2021) have shown that the TRM boundary conditions well capture the effects of real surface roughness in viscous-dominated flows. Utilising the TRM boundary model, Khorasani et al. (Reference Khorasani, Lācis, Pasche, Rosti and Bagheri2022) successfully reproduced the homogeneous geometrical roughness effects in low and intermediate ranges of the transitional rough regime.

1.2. Linear and quasi-linear modelling for wall-bounded turbulence

A growing number of linear modelling approaches have recently been developed for wall-bounded turbulent flows. Early studies considered the linearised Navier–Stokes equations around the turbulent mean velocity, typically linearly stable in wall-bounded turbulence, and studied the transient amplification mechanism to understand the origin of coherent structures (Butler & Farrell Reference Butler and Farrell1993; Chernyshenko & Baig Reference Chernyshenko and Baig2005; Del Alamo & Jimenez Reference Del Alamo and Jimenez2006; Pujals et al. Reference Pujals, García-Villalba, Cossu and Depardon2009). In a similar context, some variants of this approach have been formulated, and well-known examples include input–output analysis (Hwang & Cossu Reference Hwang and Cossu2010; McKeon & Sharma Reference McKeon and Sharma2010; Zare, Jovanović & Georgiou Reference Zare, Jovanović and Georgiou2017). These approaches have also been used for flows with surface manipulations, e.g. spanwise wall oscillation (Moarref & Jovanović Reference Moarref and Jovanović2012), opposition control (Luhar, Sharma & McKeon Reference Luhar, Sharma and McKeon2014) and riblets (Chavarin & Luhar Reference Chavarin and Luhar2020; Ran, Zare & Jovanović Reference Ran, Zare and Jovanović2021). Despite the successful applications for flow modelling, these approaches typically predict the flow behaviours mainly through the gain that characterises the amplification of the optimal input (initial condition or forcing) for the resulting output, not providing useful measures that can be obtained through DNS or experiments: e.g. drag reduction or changes in turbulence statistics. Some notable exceptions to this are those of Moarref & Jovanović (Reference Moarref and Jovanović2012) and Ran et al. (Reference Ran, Zare and Jovanović2021), where a Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) model is passively coupled, and Zampino et al. (Reference Zampino, Lasagna and Ganapathisubramani2022), who used linearised RANS equations coupled with the Spalart–Allmaras transport equation to investigate secondary currents in turbulent channel flow.

Recently, some new efforts have been made to incorporate the nonlinearity of the Navier–Stokes equations into the linear modelling approaches in a minimal manner using the framework of ‘quasi-linear’ approximation. This approach was introduced by Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and has been referred to as the ‘minimal quasi-linear approximation’ (MQLA). In this approach, the full nonlinear mean equation is considered, while the fluctuation equations are linearised around the mean velocity. The nonlinear self-interaction terms in the fluctuations equations are subsequently modelled using an empirical eddy viscosity model and stochastic forcing. Assuming that the mean velocity is empirically known (e.g. Cess Reference Cess1958), the stochastic forcing is determined self-consistently by making the Reynolds shear stresses from the fluctuation equations numerically identical to those from the mean velocity. This approach was shown to reproduce all the behaviours of second-order turbulence statistics qualitatively well even at extremely high Reynolds numbers (Skouloudis & Hwang Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022).

In MQLA, only spanwise variations in plane wavenumbers were considered, as it was originally intended to relate it to the classical attached eddy model of Townsend (Reference Townsend1976). Efforts for MQLA to include all plane wavenumbers were subsequently made (Holford, Lee & Hwang Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a ). Using the self-similarity in the velocity spectra with respect to the distance from the wall in the logarithmic region (Hwang Reference Hwang2015), the self-similar forcing spectra were assimilated from DNS data (Holford, Lee & Hwang Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2023). These forcings were then incorporated into the quasi-linear approximation framework of Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020). Compared to MQLA, this extended framework, referred to as the data-driven approximation (DQLA), provides significant quantitative improvements on the predictions of turbulence intensities with a largely reduced anisotropy (Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a ). It also offers the full two-dimensional (2-D) plane wavenumber spectra, the scaling behaviour of which is consistent with that from DNS (Hwang Reference Hwang2024).

1.3. Scope

Given the high computational demands to capture the roughness effects in the scale of the surface texture elements, the objective of the present study is to develop a quasi-linear approximation framework of Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a ) in the presence of (mildly) rough surfaces modelled by the TRM boundary conditions on the wall without detailed geometrical representations of the surface roughness. Particular attention is paid to model-based predictions for roughness functions, frequently used in the surface roughness research community (Chung et al. Reference Chung, Hutchins, Schultz and Flack2021), at a computational cost much lower than that of DNS with TRM boundary conditions. For this purpose, apart from considering both MQLA and DQLA, we further introduce a new variant of this approach designed to provide turbulence statistics better than those of MQLA at a computational cost much lower than that of DQLA. In this framework, an implicit assumption is imposed that the flow remains smooth-wall-like, with turbulent structures near the wall that are not largely modified. In this sense, the nonlinear self-interaction terms are modelled with the eddy viscosity model and stochastic forcing used for smooth walls. From the given modelling efforts, we will see that the proposed quasi-linear modelling approaches here offer encouraging predictions for the roughness functions compared to those of DNS (Khorasani et al. Reference Khorasani, Lācis, Pasche, Rosti and Bagheri2022) in the lower part of the transitional rough regime with moderate TRM boundary conditions.

This paper is organised as follows. In § 2, we briefly introduce the previous quasi-linear approximations for no-slip boundary conditions, and subsequently establish an approach to predict turbulence statistics and spectra with the TRM boundary conditions. In § 3, the roughness functions, turbulence statistics and velocity spectra predicted by the established quasi-linear approximations are compared with those from DNS (Khorasani et al. Reference Khorasani, Lācis, Pasche, Rosti and Bagheri2022), demonstrating the capability of the proposed modelling approaches here. Using the encouraging results in § 3, the behaviour of the roughness function for the mean velocity is explored in a wide range of parameter space in § 4. Finally, conclusions and perspectives of the present study are provided in § 5.

2. Problem formulation

2.1. Equations of motion

We begin by introducing the equations of motion for the quasi-linear approximation of Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) in fully-developed incompressible turbulent channel flow, bounded by two plates that are infinitely long and wide. Here, the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise coordinates are denoted as

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

, respectively, and the corresponding velocity vector is represented as

$z$

, respectively, and the corresponding velocity vector is represented as

![]() $\boldsymbol{u} = (u, v, w)$

. The channel half-height is set as

$\boldsymbol{u} = (u, v, w)$

. The channel half-height is set as

![]() $h$

, and the two plates are located at

$h$

, and the two plates are located at

![]() $y = 0, 2h$

, respectively. To implement the quasi-linear approximation, the velocity field is decomposed into a time-averaged mean

$y = 0, 2h$

, respectively. To implement the quasi-linear approximation, the velocity field is decomposed into a time-averaged mean

![]() $\boldsymbol{U} = (U(y), 0, 0)$

, and fluctuations about this mean

$\boldsymbol{U} = (U(y), 0, 0)$

, and fluctuations about this mean

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}' = (u', v', w')$

: i.e. the Reynolds decomposition. This yields the following coupled equations for the mean and fluctuations:

$\boldsymbol{u}' = (u', v', w')$

: i.e. the Reynolds decomposition. This yields the following coupled equations for the mean and fluctuations:

where

Here,

![]() $t$

denotes time and

$t$

denotes time and

![]() $\overline {({\cdot} )}$

represents the average in time and two homogeneous directions, with

$\overline {({\cdot} )}$

represents the average in time and two homogeneous directions, with

![]() $\tau _w$

the time-averaged wall shear stress,

$\tau _w$

the time-averaged wall shear stress,

![]() $p'$

the fluctuating pressure,

$p'$

the fluctuating pressure,

![]() $\rho$

the fluid density, and

$\rho$

the fluid density, and

![]() $\nu$

the kinematic viscosity. In the present study, the effects of roughness on near-wall turbulence are modelled with the TRM boundary conditions (e.g. Lācis et al. Reference Lācis, Sudhakar, Pasche and Bagheri2020). The boundary conditions for the turbulent mean velocity are written as

$\nu$

the kinematic viscosity. In the present study, the effects of roughness on near-wall turbulence are modelled with the TRM boundary conditions (e.g. Lācis et al. Reference Lācis, Sudhakar, Pasche and Bagheri2020). The boundary conditions for the turbulent mean velocity are written as

and the fluctuating velocities at the two boundaries

![]() $y=0,2h$

are defined as

$y=0,2h$

are defined as

where the coefficients

![]() $l_x$

,

$l_x$

,

![]() $l_z$

,

$l_z$

,

![]() $m_x$

and

$m_x$

and

![]() $m_z$

are slip and transpiration lengths, respectively. The TRM boundary conditions not only incorporate the Navier-slip boundary conditions for the streamwise and spanwise velocities, but also provide a transpiration condition for the wall-normal velocity that accounts for the wall-normal momentum transport associated with the surface texture through the transpiration lengths. It has been shown that these boundary conditions model well for the rough surfaces in the transitionally rough regime, which do not significantly modify the near-wall turbulence. From this perspective, it is ideal to test the modelling capacity of the quasi-linear approximations developed for smooth walls (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

).

$m_z$

are slip and transpiration lengths, respectively. The TRM boundary conditions not only incorporate the Navier-slip boundary conditions for the streamwise and spanwise velocities, but also provide a transpiration condition for the wall-normal velocity that accounts for the wall-normal momentum transport associated with the surface texture through the transpiration lengths. It has been shown that these boundary conditions model well for the rough surfaces in the transitionally rough regime, which do not significantly modify the near-wall turbulence. From this perspective, it is ideal to test the modelling capacity of the quasi-linear approximations developed for smooth walls (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

).

The mean equation (2.1a

) includes the Reynolds shear stress term that feeds back from the fluctuating velocity field. The equation for the fluctuating velocity (2.1b

) is of the form linearised about the mean velocity if the nonlinear term

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}$

is dropped. Following Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

), the nonlinear term

$\boldsymbol{N}$

is dropped. Following Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

), the nonlinear term

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}$

is modelled as

$\boldsymbol{N}$

is modelled as

where the eddy viscosity

![]() $\nu _t$

is adopted from the empirical expression of Cess (Reference Cess1958),

$\nu _t$

is adopted from the empirical expression of Cess (Reference Cess1958),

with

![]() $\eta = (y-h)/h$

, and

$\eta = (y-h)/h$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{f}'=(f'_u,f'_v,f'_w)$

is a stochastic forcing term whose amplitude and colour are to be determined. Here, the eddy viscosity parameters are set to

$\boldsymbol{f}'=(f'_u,f'_v,f'_w)$

is a stochastic forcing term whose amplitude and colour are to be determined. Here, the eddy viscosity parameters are set to

![]() $\kappa = 0.426$

and

$\kappa = 0.426$

and

![]() $A = 25.4$

, with which the best least squares fitting of the mean velocity profile of (2.1a

) is obtained with that of DNS at

$A = 25.4$

, with which the best least squares fitting of the mean velocity profile of (2.1a

) is obtained with that of DNS at

![]() $Re_{\tau }\approx 2000$

(Del Alamo & Jimenez Reference Del Alamo and Jimenez2006). The inclusion of the eddy viscosity term in (2.4a

) has been understood to significantly simplify the modelling process, and consolidates the key physical elements, as recently analysed in detail by Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

) through a comparison of spectral energy budgets between DNS and quasi-linear approximations. Furthermore, the eddy viscosity term has been consistently shown to enhance the capacity of (2.1b

) for the predictions of turbulent statistics and energy spectra, as well as for the performance of state estimations (Hwang Reference Hwang2016; Illingworth, Monty & Marusic Reference Illingworth, Monty and Marusic2018; Madhusudanan, Illingworth & Marusic Reference Madhusudanan, Illingworth and Marusic2019; Towne, Lozano-Durán & Yang Reference Towne, Lozano-Durán and Yang2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2023).

$Re_{\tau }\approx 2000$

(Del Alamo & Jimenez Reference Del Alamo and Jimenez2006). The inclusion of the eddy viscosity term in (2.4a

) has been understood to significantly simplify the modelling process, and consolidates the key physical elements, as recently analysed in detail by Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

) through a comparison of spectral energy budgets between DNS and quasi-linear approximations. Furthermore, the eddy viscosity term has been consistently shown to enhance the capacity of (2.1b

) for the predictions of turbulent statistics and energy spectra, as well as for the performance of state estimations (Hwang Reference Hwang2016; Illingworth, Monty & Marusic Reference Illingworth, Monty and Marusic2018; Madhusudanan, Illingworth & Marusic Reference Madhusudanan, Illingworth and Marusic2019; Towne, Lozano-Durán & Yang Reference Towne, Lozano-Durán and Yang2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2023).

As discussed earlier, the formulation of the quasi-linear approximations in this study requires a known mean velocity. Indeed, like RANS, (2.1) has a closure problem due to unknown

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}$

– if

$\boldsymbol{N}$

– if

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}$

is known, then (2.1) is solvable to obtain the mean and fluctuating velocities. Conversely, if part of the solution, say the mean velocity, is assumed to be known, then it is possible to construct

$\boldsymbol{N}$

is known, then (2.1) is solvable to obtain the mean and fluctuating velocities. Conversely, if part of the solution, say the mean velocity, is assumed to be known, then it is possible to construct

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}$

inversely, although

$\boldsymbol{N}$

inversely, although

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}$

is not necessarily unique (Skouloudis & Hwang Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022; see also § 2.2). This is the central theoretical element of the present quasi-linear approximations. In the present study, the construction of

$\boldsymbol{N}$

is not necessarily unique (Skouloudis & Hwang Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022; see also § 2.2). This is the central theoretical element of the present quasi-linear approximations. In the present study, the construction of

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}$

is performed using

$\boldsymbol{N}$

is performed using

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4), where the stochastic forcing term is determined with the known mean velocity. The mean velocity here is obtained by solving (2.1a

), with the well-known eddy-viscosity-based closure given by

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4), where the stochastic forcing term is determined with the known mean velocity. The mean velocity here is obtained by solving (2.1a

), with the well-known eddy-viscosity-based closure given by

![]() $-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {{\rm d}U}/{{\rm d}y}$

with

$-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {{\rm d}U}/{{\rm d}y}$

with

![]() $\nu _t$

in (2.4b

).

$\nu _t$

in (2.4b

).

2.2. Forcing models

To apply the framework of the stochastic linear dynamical system for (2.1b

) (Farrell & Ioannou Reference Farrell and Ioannou1993; Jovanović & Bamieh Reference Jovanović and Bamieh2005; Hwang & Cossu Reference Hwang and Cossu2010), we initially consider that the forcing is temporally white and spatially and componentwisely uncorrelated. Given the homogeneous nature in the wall-parallel directions, we perform the Fourier transform along the

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

directions,

$z$

directions,

where

![]() $\hat {(\cdot)}$

denotes the Fourier transformed state, and

$\hat {(\cdot)}$

denotes the Fourier transformed state, and

![]() $(k_x, k_z)$

is the considered wavenumber pair with the streamwise and spanwise wavelengths denoted as

$(k_x, k_z)$

is the considered wavenumber pair with the streamwise and spanwise wavelengths denoted as

![]() $\lambda _x = 2\pi /k_x$

and

$\lambda _x = 2\pi /k_x$

and

![]() $\lambda _z = 2\pi /k_z$

, respectively. The same definitions of the Fourier transform are used for the other flow variables. Then the spectral covariance matrix of the stochastic forcing is set to be given by

$\lambda _z = 2\pi /k_z$

, respectively. The same definitions of the Fourier transform are used for the other flow variables. Then the spectral covariance matrix of the stochastic forcing is set to be given by

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &E\left[\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'(t,y;k_x,k_z)\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'^H(t',y';k_x,k_z)\right]\\&= \begin{bmatrix} W_{u}(k_x,k_z) &0 &0\\[4pt] 0& W_{v}(k_x,k_z) &0\\[4pt] 0 &0 & W_{w}(k_x,k_z) \end{bmatrix} \delta (y-y')\,\delta (t-t'), \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &E\left[\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'(t,y;k_x,k_z)\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'^H(t',y';k_x,k_z)\right]\\&= \begin{bmatrix} W_{u}(k_x,k_z) &0 &0\\[4pt] 0& W_{v}(k_x,k_z) &0\\[4pt] 0 &0 & W_{w}(k_x,k_z) \end{bmatrix} \delta (y-y')\,\delta (t-t'), \end{aligned} \end{equation}

where

![]() $(\cdot)^H$

denotes the complex conjugate transpose,

$(\cdot)^H$

denotes the complex conjugate transpose,

![]() $E[\cdot]$

is the expectation operator on different stochastic realisations,

$E[\cdot]$

is the expectation operator on different stochastic realisations,

![]() $\delta (\cdot)$

is the Dirac delta function, and

$\delta (\cdot)$

is the Dirac delta function, and

![]() $W_{l}$

with

$W_{l}$

with

![]() $l=\{u,v,w\}$

are component weights as functions of

$l=\{u,v,w\}$

are component weights as functions of

![]() $k_x$

and

$k_x$

and

![]() $k_z$

, through which the amplitude of the stochastic forcing is determined in the streamwise and spanwise directions.

$k_z$

, through which the amplitude of the stochastic forcing is determined in the streamwise and spanwise directions.

The following spectral (spatial and componentwise) covariance matrix of velocity fluctuations can be computed by solving (2.1b ) in the Fourier space, if the stochastic forcing is specified:

Given the existence of a linear relationship between the velocity and forcing spectral covariance matrices,

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu}}(y,y'; k_x,k_z)$

is written as

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu}}(y,y'; k_x,k_z)$

is written as

where

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

is the velocity spectral covariance matrix corresponding to each component of the forcing with the unit amplitude (Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). In particular, using the linear nature of (2.4a

),

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

is the velocity spectral covariance matrix corresponding to each component of the forcing with the unit amplitude (Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). In particular, using the linear nature of (2.4a

),

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8) is obtained from the linear response to the white-in-time forcing with the unit amplitude (i.e. setting

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8) is obtained from the linear response to the white-in-time forcing with the unit amplitude (i.e. setting

![]() $W_{{l}}(k_x,k_z)=1$

for each

$W_{{l}}(k_x,k_z)=1$

for each

![]() $l\ (=u,v,w)$

). For instance,

$l\ (=u,v,w)$

). For instance,

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},u}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8) is the velocity spectral covariance matrix computed with the forcing

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},u}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8) is the velocity spectral covariance matrix computed with the forcing

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} E[&\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'(t,y;k_x,k_z)\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'^H(t',y';k_x,k_z)]= \begin{bmatrix} \delta (y-y') &0&0\\ 0& 0 &0\\ 0 &0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \delta (t-t'). \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} E[&\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'(t,y;k_x,k_z)\,\hat {\!\boldsymbol{f}}'^H(t',y';k_x,k_z)]= \begin{bmatrix} \delta (y-y') &0&0\\ 0& 0 &0\\ 0 &0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \delta (t-t'). \end{aligned} \end{equation}

The stochastic forcing in (2.6) serves as a starting point for the quasi-linear approximation approach here. With the pre-computed

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

, the remaining problem becomes the determination of

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

, the remaining problem becomes the determination of

![]() $W_l$

in such a way that the resulting Reynolds shear stress corresponds to that in (2.1) using the prescribed mean velocity (for the details, see Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). However, a forcing that is white in time and decorrelated in the wall-normal direction for each

$W_l$

in such a way that the resulting Reynolds shear stress corresponds to that in (2.1) using the prescribed mean velocity (for the details, see Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). However, a forcing that is white in time and decorrelated in the wall-normal direction for each

![]() $k_x$

and

$k_x$

and

![]() $k_z$

is physically unrealistic. Indeed, this kind of forcing covariance has previously been shown to generate a non-physical large energy response in the region close to the channel centre (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). It has been proposed that a simple ad hoc solution to this is considering some of the leading proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) modes from the response to the stochastic forcing, which can capture the primary energy-containing motions at integral length scales – the reader may refer to Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

), where the origin of the non-physical stochastic response, the effect of the number of the POD modes, and the related energetics are fully discussed for the quasi-linear approximations considered here. Employing this approach, the velocity spectral covariance matrix is further approximated by considering some of the leading POD modes from

$k_z$

is physically unrealistic. Indeed, this kind of forcing covariance has previously been shown to generate a non-physical large energy response in the region close to the channel centre (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). It has been proposed that a simple ad hoc solution to this is considering some of the leading proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) modes from the response to the stochastic forcing, which can capture the primary energy-containing motions at integral length scales – the reader may refer to Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

), where the origin of the non-physical stochastic response, the effect of the number of the POD modes, and the related energetics are fully discussed for the quasi-linear approximations considered here. Employing this approach, the velocity spectral covariance matrix is further approximated by considering some of the leading POD modes from

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8):

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8):

\begin{equation} \phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}^{\textit{POD}}(y,y';k_x,k_z) \approx \sum _{i=1}^{N_{\textit{POD}}} \sigma _i\, \hat {\boldsymbol{u}}_{i,POD}(y;k_x,k_z)\,\hat {\boldsymbol{u}}_{i,POD}^H(y';k_x,k_z), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}^{\textit{POD}}(y,y';k_x,k_z) \approx \sum _{i=1}^{N_{\textit{POD}}} \sigma _i\, \hat {\boldsymbol{u}}_{i,POD}(y;k_x,k_z)\,\hat {\boldsymbol{u}}_{i,POD}^H(y';k_x,k_z), \end{equation}

where

![]() $N_{\textit{POD}}$

is the number of the considered leading POD modes, and

$N_{\textit{POD}}$

is the number of the considered leading POD modes, and

![]() $\sigma _i$

and

$\sigma _i$

and

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{u}}_{i,POD}$

are the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the velocity spectral covariance matrix obtained from the white-in-time and spatially decorrelated forcing

$\hat {\boldsymbol{u}}_{i,POD}$

are the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the velocity spectral covariance matrix obtained from the white-in-time and spatially decorrelated forcing

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8). Based on previous findings (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

),

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8). Based on previous findings (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

),

![]() $N_{\textit{POD}} = 2$

is considered in this study.

$N_{\textit{POD}} = 2$

is considered in this study.

Following Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

), the forcing weight

![]() $W_{l}(k_x,k_z)$

for each component is further prescribed in the form

$W_{l}(k_x,k_z)$

for each component is further prescribed in the form

Here, the self-similar streamwise weight

![]() $W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

is used to account for the self-similar nature of the energy-containing part in the velocity and forcing spectra (i.e. the attached eddy hypothesis; for further details, see Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2023), and

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

is used to account for the self-similar nature of the energy-containing part in the velocity and forcing spectra (i.e. the attached eddy hypothesis; for further details, see Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2023), and

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is used to determine the forcing amplitude for each spanwise scale that varies from the near-wall (

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is used to determine the forcing amplitude for each spanwise scale that varies from the near-wall (

![]() $\lambda _z^+ \approx O(100)$

) to the outer one (

$\lambda _z^+ \approx O(100)$

) to the outer one (

![]() $\lambda _z/h \approx O(1)$

) (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020).

$\lambda _z/h \approx O(1)$

) (Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020).

We note that the streamwise weight

![]() $W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

is essentially a modelling choice for the quasi-linear approximations in the present study. This is because, for any arbitrary choice of

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

is essentially a modelling choice for the quasi-linear approximations in the present study. This is because, for any arbitrary choice of

![]() $W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

, there may well exist

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

, there may well exist

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

that provides the Reynolds shear stress identical to the one given by the prescribed mean velocity profile (for a further discussion, see Skouloudis & Hwang Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022). In the present study, therefore, three models for

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

that provides the Reynolds shear stress identical to the one given by the prescribed mean velocity profile (for a further discussion, see Skouloudis & Hwang Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022). In the present study, therefore, three models for

![]() $W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

are considered.

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

are considered.

-

(i) The MQLA model considers the form of the self-similar streamwise weight as

(2.12)for all \begin{equation} W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)=\tfrac{1}{3}\delta (k_x/k_z) \end{equation}

\begin{equation} W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)=\tfrac{1}{3}\delta (k_x/k_z) \end{equation}

$l$

(Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020). This is the simplest form of the quasi-linear approximations, since it completely ignores the statistical structure of the velocity spectra in the streamwise direction. For the same reason, it is computationally the cheapest option, since the covariance matrix

$l$

(Hwang & Eckhardt Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020). This is the simplest form of the quasi-linear approximations, since it completely ignores the statistical structure of the velocity spectra in the streamwise direction. For the same reason, it is computationally the cheapest option, since the covariance matrix

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

needs to be pre-computed only for

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

needs to be pre-computed only for

$k_x=0$

.

$k_x=0$

.

-

(ii) The DQLA model considers the streamwise weight

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

obtained by assimilating DNS data in the logarithmic region at

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

obtained by assimilating DNS data in the logarithmic region at

$Re_\tau =5200$

(Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). In the present study,

$Re_\tau =5200$

(Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). In the present study,

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

obtained for

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

obtained for

$k_z h=126$

in Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

) is used (see their figure 1). This is a spanwise wavenumber associated with the logarithmic region (i.e.

$k_z h=126$

in Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

) is used (see their figure 1). This is a spanwise wavenumber associated with the logarithmic region (i.e.

$100/Re_{\tau }\lesssim \lambda _z/h \lesssim 1.5$

). We note that in Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

),

$100/Re_{\tau }\lesssim \lambda _z/h \lesssim 1.5$

). We note that in Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

),

$k_z h=14,30,50,76,126$

were tested for

$k_z h=14,30,50,76,126$

were tested for

$Re_\tau =5200$

. The chosen

$Re_\tau =5200$

. The chosen

$k_z h=126$

corresponds to

$k_z h=126$

corresponds to

$\lambda _z^+=259$

at

$\lambda _z^+=259$

at

$Re_\tau =5200$

and is most relevant to the region near the wall among all the weights computed. By construction, DQLA offers the full 2-D spectra as a result of the non-zero streamwise weight. However, this improvement comes at a largely increased computational cost, as it requires pre-computations of the covariance matrix

$Re_\tau =5200$

and is most relevant to the region near the wall among all the weights computed. By construction, DQLA offers the full 2-D spectra as a result of the non-zero streamwise weight. However, this improvement comes at a largely increased computational cost, as it requires pre-computations of the covariance matrix

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

in the full range of

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

in the full range of

$k_x \ne 0$

for all velocity components – indeed, the computational cost of DQLA is typically a few hundred times greater than that of MQLA (see table 1).

$k_x \ne 0$

for all velocity components – indeed, the computational cost of DQLA is typically a few hundred times greater than that of MQLA (see table 1). -

(iii) The minimal two-mode quasi-linear approximation (M2QLA) model in the present study considers the following simple form of the streamwise weight

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

:(2.13)for all

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

:(2.13)for all \begin{equation} W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)=\tfrac{1}{3}\left [\delta (k_x/k_z)+ \delta (k_x/k_z \pm 0.5)\right ] \end{equation}

\begin{equation} W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)=\tfrac{1}{3}\left [\delta (k_x/k_z)+ \delta (k_x/k_z \pm 0.5)\right ] \end{equation}

$l$

. By construction, this model resembles MQLA, but includes a minimal variation in the streamwise direction. The first term on the right-hand side of (2.13) is designed to model long streaky structures in the near-wall, logarithmic and outer regions (

$l$

. By construction, this model resembles MQLA, but includes a minimal variation in the streamwise direction. The first term on the right-hand side of (2.13) is designed to model long streaky structures in the near-wall, logarithmic and outer regions (

$\lambda _x\gt 10 \lambda _z$

), while the second term is for the related streamwise wavy motions involving quasi-streamwise vortical strictures (

$\lambda _x\gt 10 \lambda _z$

), while the second term is for the related streamwise wavy motions involving quasi-streamwise vortical strictures (

$\lambda _x \approx 2 \lambda _z$

) (for a detailed discussion, see Hwang Reference Hwang2015). The computational cost of M2QLA is only a couple of times greater than that of MQLA, as it only requires pre-computations of

$\lambda _x \approx 2 \lambda _z$

) (for a detailed discussion, see Hwang Reference Hwang2015). The computational cost of M2QLA is only a couple of times greater than that of MQLA, as it only requires pre-computations of

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

for

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

for

$k_x=0$

and

$k_x=0$

and

$k_x/k_z=\pm 0.5$

.

$k_x/k_z=\pm 0.5$

.

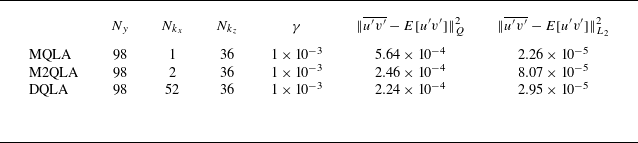

Table 1. Numerical and optimisation parameters used in the present study at

![]() $Re_{\tau }=180$

:

$Re_{\tau }=180$

:

![]() $N_y$

, the number of wall-normal collocation points;

$N_y$

, the number of wall-normal collocation points;

![]() $N_{k_x}$

, the number of streamwise wavenumbers;

$N_{k_x}$

, the number of streamwise wavenumbers;

![]() $N_{k_z}$

, the number of spanwise wavenumbers. Here,

$N_{k_z}$

, the number of spanwise wavenumbers. Here,

![]() $\|\cdot\|_Q^2 \equiv ({u_\tau ^2/h})\int _0^{2h}(\cdot)^2\, Q(y)\, {\rm d}y$

and

$\|\cdot\|_Q^2 \equiv ({u_\tau ^2/h})\int _0^{2h}(\cdot)^2\, Q(y)\, {\rm d}y$

and

![]() $\|\cdot\|_{L_2}^2\equiv ({u_\tau ^2/h})\int _0^{2h}(\cdot)^2\, {\rm d}y$

.

$\|\cdot\|_{L_2}^2\equiv ({u_\tau ^2/h})\int _0^{2h}(\cdot)^2\, {\rm d}y$

.

2.3. Quasi-linear approximations

Thus far, we have discussed how we construct the forcing for each

![]() $k_z$

, i.e. the self-similarity-based decomposition of

$k_z$

, i.e. the self-similarity-based decomposition of

![]() $W_l(k_x,k_z)=W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)\,W_{k_z}(k_z)$

, the form of

$W_l(k_x,k_z)=W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)\,W_{k_z}(k_z)$

, the form of

![]() $W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

, and the use of POD modes. Now, we discuss how the forcing structure for each

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

, and the use of POD modes. Now, we discuss how the forcing structure for each

![]() $k_z$

is used to determine

$k_z$

is used to determine

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

, which will make the fluctuations from (2.1b

) consistent with the mean equation (2.1a

).

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

, which will make the fluctuations from (2.1b

) consistent with the mean equation (2.1a

).

Given the discussion in § 2.2, the final form of the velocity covariance matrix in the Fourier space is written as

with the dimensions

![]() $3N_{y}\times 3N_{y}$

, for each

$3N_{y}\times 3N_{y}$

, for each

![]() $k_x$

and

$k_x$

and

![]() $k_z$

. Before applying the quasi-linear approximation for the TRM boundary condition in (2.2) and (2.3), we establish the solution procedure of the quasi-linear approximations for the no-slip boundary condition. Following the procedure documented in Willis, Hwang & Cossu (Reference Willis, Hwang and Cossu2010), the spectral covariance operator

$k_z$

. Before applying the quasi-linear approximation for the TRM boundary condition in (2.2) and (2.3), we establish the solution procedure of the quasi-linear approximations for the no-slip boundary condition. Following the procedure documented in Willis, Hwang & Cossu (Reference Willis, Hwang and Cossu2010), the spectral covariance operator

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8) is first obtained from the response of the linearised Navier–Stokes equations to white-in-time noise provided componentwise with the unit amplitude: for example,

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

in (2.8) is first obtained from the response of the linearised Navier–Stokes equations to white-in-time noise provided componentwise with the unit amplitude: for example,

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},u}^{\textit{POD}}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

is obtained by setting

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},u}^{\textit{POD}}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

is obtained by setting

![]() $W_u=1$

and

$W_u=1$

and

![]() $W_v=W_w=0$

. For this purpose, the eigenvalue problem from (2.1b

) with the nonlinear term model

$W_v=W_w=0$

. For this purpose, the eigenvalue problem from (2.1b

) with the nonlinear term model

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4a

) is first solved in terms of the primitive variables

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4a

) is first solved in terms of the primitive variables

![]() $(u',v',w',p')$

using a Chebyshev collocation method (Weideman & Reddy Reference Weideman and Reddy2000). The Lyapunov equation for the velocity spectral covariance operator

$(u',v',w',p')$

using a Chebyshev collocation method (Weideman & Reddy Reference Weideman and Reddy2000). The Lyapunov equation for the velocity spectral covariance operator

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

is subsequently formulated in the resulting eigenfunction space and is solved using the lyap function in MATLAB (see Appendix A for further details). Finally, the velocity spectral covariance operator

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

is subsequently formulated in the resulting eigenfunction space and is solved using the lyap function in MATLAB (see Appendix A for further details). Finally, the velocity spectral covariance operator

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

is further approximated using the two leading POD modes (i.e.

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}$

is further approximated using the two leading POD modes (i.e.

![]() $N_{\textit{POD}}=2$

), as discussed with (2.10).

$N_{\textit{POD}}=2$

), as discussed with (2.10).

Now,

![]() $\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}^{\textit{POD}}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

was determined as detailed above, and

$\phi _{\boldsymbol{\it uu},l}^{\textit{POD}}(y,y';k_x,k_z)$

was determined as detailed above, and

![]() $W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

was prescribed through § 2.2. Therefore, only the determination of

$W_{l,k_x}(k_x/k_z)$

was prescribed through § 2.2. Therefore, only the determination of

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

remains. For the determination of the spanwise weight

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

remains. For the determination of the spanwise weight

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

, an optimisation problem is formulated to minimise the difference between the Reynolds shear stress required for the mean profile

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

, an optimisation problem is formulated to minimise the difference between the Reynolds shear stress required for the mean profile

![]() $\overline {u'v'}(y)$

and that generated by the fluctuation equation

$\overline {u'v'}(y)$

and that generated by the fluctuation equation

![]() $E[{u}'{v}'](y)$

. In particular, the following optimisation problem for

$E[{u}'{v}'](y)$

. In particular, the following optimisation problem for

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is considered following Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

):

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is considered following Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

):

\begin{align} \min _{W_{k_z}} \left [\!\frac {\int _0^{2h}(\overline {u'v'}(y)-E[u'v'](y))^2\,Q(y)\,{\rm d}y}{\int _0^{2h}(\overline {u'v'}(y))^2\,Q(y)\,{\rm d}y} \!\right ]^{0.5}\!+\gamma \left [\! \int _0^{\infty }\!\left (\frac {{\rm d}^2W_{k_z}(k_z)}{{\rm d}(\ln k_z)^2}\right )^2\! R_{uv}(k_z)\,{\rm d}k_z\!\right ]^{0.5}\nonumber\\[4pt] \end{align}

\begin{align} \min _{W_{k_z}} \left [\!\frac {\int _0^{2h}(\overline {u'v'}(y)-E[u'v'](y))^2\,Q(y)\,{\rm d}y}{\int _0^{2h}(\overline {u'v'}(y))^2\,Q(y)\,{\rm d}y} \!\right ]^{0.5}\!+\gamma \left [\! \int _0^{\infty }\!\left (\frac {{\rm d}^2W_{k_z}(k_z)}{{\rm d}(\ln k_z)^2}\right )^2\! R_{uv}(k_z)\,{\rm d}k_z\!\right ]^{0.5}\nonumber\\[4pt] \end{align}

subject to

where

![]() $Q(y)=(1-|\eta |)^{-1}$

to place equal emphasis on wall-normal grid points via a logarithmic scaling with distance from the wall. The first term of (2.15a

) is a relative error in the Reynolds shear stress with the term introduced in its denominator, and the second term is a regularisation term for the generation of a smooth

$Q(y)=(1-|\eta |)^{-1}$

to place equal emphasis on wall-normal grid points via a logarithmic scaling with distance from the wall. The first term of (2.15a

) is a relative error in the Reynolds shear stress with the term introduced in its denominator, and the second term is a regularisation term for the generation of a smooth

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

in the logarithmic coordinate of

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

in the logarithmic coordinate of

![]() $k_z$

(see below for a further explanation). The combination of the two square-rooted quadratic functions of

$k_z$

(see below for a further explanation). The combination of the two square-rooted quadratic functions of

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

enables us to use the second-order cone programming (e.g. Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2023, Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). From this point of view, different forms of the optimisation problem can be formulated to achieve the same goal, as in Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Skouloudis & Hwang (Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022).

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

enables us to use the second-order cone programming (e.g. Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2023, Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). From this point of view, different forms of the optimisation problem can be formulated to achieve the same goal, as in Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Skouloudis & Hwang (Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022).

In (2.15), the weight function

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is constrained to be in the range between

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is constrained to be in the range between

![]() $ \lambda _z^+=10$

and

$ \lambda _z^+=10$

and

![]() $ \lambda _z=10h$

, with the values of

$ \lambda _z=10h$

, with the values of

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

at the smallest and largest spanwise wavelengths set to zero, i.e.

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

at the smallest and largest spanwise wavelengths set to zero, i.e.

![]() $W_{k_z}(\lambda ^+_z= 10) =W_{k_z} (\lambda _z = 10h) = 0$

. Given the spanwise scale typically varying from

$W_{k_z}(\lambda ^+_z= 10) =W_{k_z} (\lambda _z = 10h) = 0$

. Given the spanwise scale typically varying from

![]() $\lambda _z^+ \approx 100$

in the near-wall region to

$\lambda _z^+ \approx 100$

in the near-wall region to

![]() $\lambda _z \approx 1.5h$

in the outer region (Hwang Reference Hwang2015), such a constraint on

$\lambda _z \approx 1.5h$

in the outer region (Hwang Reference Hwang2015), such a constraint on

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is able to cover a full range of spanwise length scales, from near-wall motions to very large-scale motions in the outer layer. The Reynolds shear stress, denoted as

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

is able to cover a full range of spanwise length scales, from near-wall motions to very large-scale motions in the outer layer. The Reynolds shear stress, denoted as

![]() $\overline {u'v'}(y)$

, is solved by considering the classical mixing length model with the eddy viscosity in (2.4b

) for the mean momentum equation in (2.1a

):

$\overline {u'v'}(y)$

, is solved by considering the classical mixing length model with the eddy viscosity in (2.4b

) for the mean momentum equation in (2.1a

):

![]() $-\overline {u'v'}(y)=\nu _t {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

. The Reynolds shear stress

$-\overline {u'v'}(y)=\nu _t {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

. The Reynolds shear stress

![]() $E[u'v'](y)$

, generated from the fluctuation equation (2.1b

) with the incorporation of the nonlinear term model (2.4a

), is formulated using

$E[u'v'](y)$

, generated from the fluctuation equation (2.1b

) with the incorporation of the nonlinear term model (2.4a

), is formulated using

where

![]() $\phi _{uv}$

is from (2.1). The constraint

$\phi _{uv}$

is from (2.1). The constraint

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)\geqslant 0$

is given to ensure that the forcing covariance remains positive definite. Additionally,

$W_{k_z}(k_z)\geqslant 0$

is given to ensure that the forcing covariance remains positive definite. Additionally,

![]() $W_{k_z}$

must exhibit sufficient smoothness to prevent the existence of any non-physical flow features. To ensure this smoothness in the logarithmic

$W_{k_z}$

must exhibit sufficient smoothness to prevent the existence of any non-physical flow features. To ensure this smoothness in the logarithmic

![]() $k_z$

coordinate, a global regularisation term with the related second-order derivative of

$k_z$

coordinate, a global regularisation term with the related second-order derivative of

![]() $W_{k_z}$

is included in (2.15a

), with

$W_{k_z}$

is included in (2.15a

), with

![]() $\gamma$

controlling its relative importance, such that a set of physically plausible smooth velocity spectra can be achieved. The smoothness regularisation is further weighted by

$\gamma$

controlling its relative importance, such that a set of physically plausible smooth velocity spectra can be achieved. The smoothness regularisation is further weighted by

![]() $R_{uv}(k_z)$

, which is defined as

$R_{uv}(k_z)$

, which is defined as

\begin{equation} R_{uv}(k_z)=\frac {1}{2\pi }\int _h^{2h}\int _{-\infty }^{\infty } \sum _{{l}=u,v,w} W_{{l},k_x}(k_x/k_z)\, \phi _{uv,{l}}^{\textit{POD}} (y,y;k_x,k_z)\,{\rm d}k_x\,{\rm d}y, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} R_{uv}(k_z)=\frac {1}{2\pi }\int _h^{2h}\int _{-\infty }^{\infty } \sum _{{l}=u,v,w} W_{{l},k_x}(k_x/k_z)\, \phi _{uv,{l}}^{\textit{POD}} (y,y;k_x,k_z)\,{\rm d}k_x\,{\rm d}y, \end{equation}

and it tends to have large values at large spanwise wavelengths. Since spectra of the Reynolds shear stress contain large energy at large spanwise wavelengths, the regularisation term is more heavily weighted at such wavelengths. This weighting accounts for the rapid decay in Reynolds shear stress spectra observed in previous studies (Skouloudis & Hwang Reference Skouloudis and Hwang2022; Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a ). It prevents erroneous behaviours in velocity spectra at larger scales, encouraging a smoothly attached compact support at the large spanwise length scales.

The optimisation problem in (2.15) is discretised along the streamwise and spanwise wavenumber axis using a uniform logarithmic spacing, with

![]() $\varDelta (\ln k_xh) \leqslant 0.15$

for

$\varDelta (\ln k_xh) \leqslant 0.15$

for

![]() $\lambda _x/h \in [10/Re_\tau ,100]$

(DQLA) and

$\lambda _x/h \in [10/Re_\tau ,100]$

(DQLA) and

![]() $\varDelta (\ln k_zh) \leqslant 0.15$

for

$\varDelta (\ln k_zh) \leqslant 0.15$

for

![]() $\lambda _z/h \in [10/Re_\tau ,10]$

(

$\lambda _z/h \in [10/Re_\tau ,10]$

(

![]() $Re_\tau \equiv u_\tau h/\nu$

, where

$Re_\tau \equiv u_\tau h/\nu$

, where

![]() $u_\tau$

is the friction velocity). The integration with respect to the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers is conducted using the trapezoidal method in the logarithmic coordinates. The optimisation problem in (2.15) is formulated in a standard form of a second-order cone program, such that it can be efficiently solved with the MOSEK solver in MATLAB; for further details, the reader may refer to Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). Table 1 shows the details on the number of streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers, collocation points in the wall-normal direction, the value of the penalty

$u_\tau$

is the friction velocity). The integration with respect to the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers is conducted using the trapezoidal method in the logarithmic coordinates. The optimisation problem in (2.15) is formulated in a standard form of a second-order cone program, such that it can be efficiently solved with the MOSEK solver in MATLAB; for further details, the reader may refer to Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

). Table 1 shows the details on the number of streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers, collocation points in the wall-normal direction, the value of the penalty

![]() $\gamma$

in (2.15), and the associated errors in the

$\gamma$

in (2.15), and the associated errors in the

![]() $Q$

and

$Q$

and

![]() $L_2$

norms of the optimisation problem at

$L_2$

norms of the optimisation problem at

![]() $Re_{\tau }=180$

. Figure 1(a) shows the weight

$Re_{\tau }=180$

. Figure 1(a) shows the weight

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

obtained by solving (2.15) for M2QLA. Using this weight, an almost exact agreement can be achieved between the Reynolds shear stress profiles from the mean equation (2.1a

) and the fluctuation equations (2.1b

), as shown in figure 1(b). The same level of agreement is also obtained for

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

obtained by solving (2.15) for M2QLA. Using this weight, an almost exact agreement can be achieved between the Reynolds shear stress profiles from the mean equation (2.1a

) and the fluctuation equations (2.1b

), as shown in figure 1(b). The same level of agreement is also obtained for

![]() $W_{k_z}(k_z)$

for MQLA and DQLA (table 1).

$W_{k_z}(k_z)$

for MQLA and DQLA (table 1).

Figure 1. Outputs of M2QLA optimisation: (a) the spanwise weight of Fourier modes; (b) the Reynolds shear stress profiles from the mean equation (blue dashed line) and the fluctuating equations (red solid line). Here,

![]() $\gamma =0.001$

,

$\gamma =0.001$

,

![]() $Re_{\tau }=180$

and

$Re_{\tau }=180$

and

![]() $N_y=98$

.

$N_y=98$

.

Figure 2. Outputs of optimisation: (a)

![]() $u^{\prime }_{rms}/ u_{\tau }$

, (b)

$u^{\prime }_{rms}/ u_{\tau }$

, (b)

![]() $v^{\prime }_{rms}/u_{\tau }$

, (c)

$v^{\prime }_{rms}/u_{\tau }$

, (c)

![]() $w^{\prime }_{rms}/u_{\tau }$

, with MQLA (red), DQLA (blue) and M2QLA (green) at

$w^{\prime }_{rms}/u_{\tau }$

, with MQLA (red), DQLA (blue) and M2QLA (green) at

![]() $Re_{\tau }=180$

. The optimisation parameters are listed in table 1. The DNS results from Lee & Moser (Reference Lee and Moser2015) are also plotted for comparison (black).

$Re_{\tau }=180$

. The optimisation parameters are listed in table 1. The DNS results from Lee & Moser (Reference Lee and Moser2015) are also plotted for comparison (black).

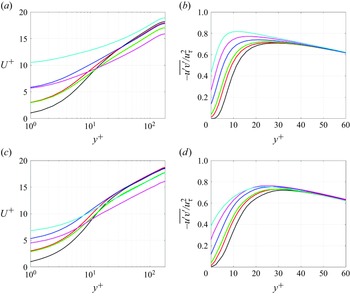

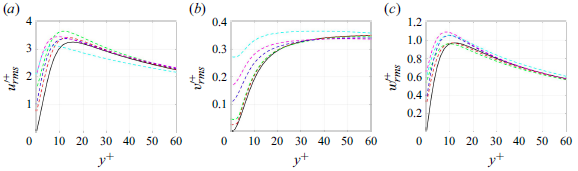

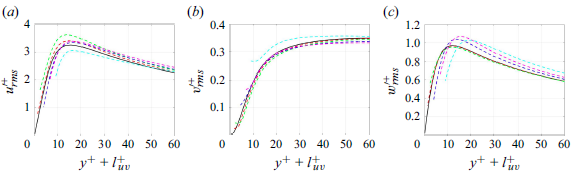

Figure 2 compares the velocity fluctuations from the present quasi-linear approximations with those of DNS (Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2015) at

![]() $Re_{\tau }=180$

. The MQLA shows the most anisotropic turbulent velocity fluctuations: the streamwise fluctuations are much greater than those of DNS, while the cross-streamwise ones are much smaller. This is because streamwise-dependent Fourier modes are excluded, preventing any energy transfer from the streamwise velocity to the rest through the streamwise pressure strain Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

,Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang

b

). Indeed, inclusion of an additional streamwise-varying Fourier mode improves this undesirable anisotropy, as seen in the velocity fluctuations from M2QLA. Finally, the anisotropy of DQLA is comparable to that of DNS, as expected. Despite the encouraging improvement in DQLA, its turbulence statistics still show some non-negligible differences from those of DNS, especially in the wall-normal and spanwise velocity fluctuations. This is because the simple nonlinear term model in (2.4a

) and the inclusion of only two leading POD modes do not correctly model the nonlinear processes involved in the pressure-strain transport, especially by slow pressure. For a detailed discussion, the reader may refer to Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

).

$Re_{\tau }=180$

. The MQLA shows the most anisotropic turbulent velocity fluctuations: the streamwise fluctuations are much greater than those of DNS, while the cross-streamwise ones are much smaller. This is because streamwise-dependent Fourier modes are excluded, preventing any energy transfer from the streamwise velocity to the rest through the streamwise pressure strain Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

,Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang

b

). Indeed, inclusion of an additional streamwise-varying Fourier mode improves this undesirable anisotropy, as seen in the velocity fluctuations from M2QLA. Finally, the anisotropy of DQLA is comparable to that of DNS, as expected. Despite the encouraging improvement in DQLA, its turbulence statistics still show some non-negligible differences from those of DNS, especially in the wall-normal and spanwise velocity fluctuations. This is because the simple nonlinear term model in (2.4a

) and the inclusion of only two leading POD modes do not correctly model the nonlinear processes involved in the pressure-strain transport, especially by slow pressure. For a detailed discussion, the reader may refer to Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

).

2.4. The TRM boundary conditions

Having established the quasi-linear approximations for no-slip boundary conditions, we now extend this framework for the case with TRM boundary conditions. The key task here is to develop a quasi-linear framework that predicts the change in the mean and fluctuation velocities by TRM boundary conditions subject to the equations of motion. We start by considering the steady mean momentum equation for a rough surface modelled by TRM boundary conditions:

where the subscript

![]() $r$

denotes the flow quantities over the rough surface, and

$r$

denotes the flow quantities over the rough surface, and

![]() ${\rm d}P_0/{\rm d}x$

is the applied streamwise pressure gradient. The mean velocity and Reynolds shear stress are first decomposed as

${\rm d}P_0/{\rm d}x$

is the applied streamwise pressure gradient. The mean velocity and Reynolds shear stress are first decomposed as

![]() $U_r=U_s+\delta U$

and

$U_r=U_s+\delta U$

and

![]() $\overline {u'v'}_{\!\!r}= \overline {u'v'}_{\!\!s} + \delta \overline {u'v'}$

, with the subscript

$\overline {u'v'}_{\!\!r}= \overline {u'v'}_{\!\!s} + \delta \overline {u'v'}$

, with the subscript

![]() $s$

representing the quantities on the smooth wall. Here, the applied streamwise pressure gradient is chosen to be unchanged in both rough- and smooth-wall cases. Substituting the decompositions into (2.18), and extracting the mean equation without roughness for the given streamwise pressure gradient, yields

$s$

representing the quantities on the smooth wall. Here, the applied streamwise pressure gradient is chosen to be unchanged in both rough- and smooth-wall cases. Substituting the decompositions into (2.18), and extracting the mean equation without roughness for the given streamwise pressure gradient, yields

Similarly, substituting the decomposition for mean velocity into (2.2) and extracting the boundary condition over the smooth wall lead to the boundary condition for

![]() $\delta U$

:

$\delta U$

:

In the absence of a streamwise pressure gradient term, (2.19) can be solved if

![]() $\delta \overline {u'v'}$

is given. Within the present quasi-linear approximation framework,

$\delta \overline {u'v'}$

is given. Within the present quasi-linear approximation framework,

![]() $\delta \overline {u'v'}$

will have to be obtained by solving the turbulent fluctuation (2.1b

) with

$\delta \overline {u'v'}$

will have to be obtained by solving the turbulent fluctuation (2.1b

) with

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4a

) subject to the TRM boundary conditions (2.3). However, (2.1b

) is also coupled with (2.19a

) through the mean velocity, indicating that (2.19a

) must be solved simultaneously with (2.1b

).

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4a

) subject to the TRM boundary conditions (2.3). However, (2.1b

) is also coupled with (2.19a

) through the mean velocity, indicating that (2.19a

) must be solved simultaneously with (2.1b

).

The quasi-linear approximations in Hwang & Eckhardt (Reference Hwang and Eckhardt2020) and Holford et al. (Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024a

) were about the self-consistent determination of the forcing term in (2.4a

), with the assumption that mean velocity is known prior. In contrast, the problem here is to predict the changes in mean and fluctuating velocities due to the TRM boundary condition. In this case, the form of

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

should be known prior to the determination of the changes in mean and fluctuations – otherwise, the problem will have a closure issue. A simple closure for

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

should be known prior to the determination of the changes in mean and fluctuations – otherwise, the problem will have a closure issue. A simple closure for

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

that we have chosen in the present study is to fix

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

that we have chosen in the present study is to fix

![]() $\nu _t$

in (2.4b

), and

$\nu _t$

in (2.4b

), and

![]() $W_l(k_x,k_z)$

in (2.6), for

$W_l(k_x,k_z)$

in (2.6), for

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4a

), and this is seen to perform well (see § 3) as long as the flow modification by the TRM boundary condition remains modest (i.e. the smooth-wall-like regime). This choice certainly deserves further discussion, which will be given at the end of this section.

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

in (2.4a

), and this is seen to perform well (see § 3) as long as the flow modification by the TRM boundary condition remains modest (i.e. the smooth-wall-like regime). This choice certainly deserves further discussion, which will be given at the end of this section.

Given the form of

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

, we now introduce the procedure to obtain the mean and fluctuating velocities. To solve (2.19a

), we introduce an artificial unsteady term, such that

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

, we now introduce the procedure to obtain the mean and fluctuating velocities. To solve (2.19a

), we introduce an artificial unsteady term, such that

with an artificial time

![]() $\tau$

, while obtaining

$\tau$

, while obtaining

![]() $\delta \overline {u'v'}$

by solving the algebraic (or steady) Lyapunov equation related to (2.1b

) with the boundary conditions in (2.3). Equation (2.20) is subsequently discretised with a mixed first-order Euler method, where the viscous term is treated implicitly, while the Reynolds shear stress term is done explicitly – we note that given the purpose of obtaining the steady solutions, the accuracy of the time integration here is not very important. At each time step, the Reynolds shear stress is obtained by solving the Lyapunov equation for (2.1b

) with the mean velocity

$\delta \overline {u'v'}$

by solving the algebraic (or steady) Lyapunov equation related to (2.1b

) with the boundary conditions in (2.3). Equation (2.20) is subsequently discretised with a mixed first-order Euler method, where the viscous term is treated implicitly, while the Reynolds shear stress term is done explicitly – we note that given the purpose of obtaining the steady solutions, the accuracy of the time integration here is not very important. At each time step, the Reynolds shear stress is obtained by solving the Lyapunov equation for (2.1b

) with the mean velocity

![]() $U_r$

, updated with

$U_r$

, updated with

![]() $\delta U$

in (2.20), and the boundary conditions (2.3). The initial condition for (2.20) is obtained by solving (2.19a

) with the mixing length model, where

$\delta U$

in (2.20), and the boundary conditions (2.3). The initial condition for (2.20) is obtained by solving (2.19a

) with the mixing length model, where

![]() $-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

, with

$-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

, with

![]() $\nu _t$

from (2.4b

). The time integration is performed with

$\nu _t$

from (2.4b

). The time integration is performed with

![]() $\Delta \tau\, u_\tau /h =0.003$

until it provides a well-converged solution for (2.19a

) with the given quasi-linear approximation framework in § 2.3. Further details on the algorithm described here are summarised in Algorithm1.

$\Delta \tau\, u_\tau /h =0.003$

until it provides a well-converged solution for (2.19a

) with the given quasi-linear approximation framework in § 2.3. Further details on the algorithm described here are summarised in Algorithm1.

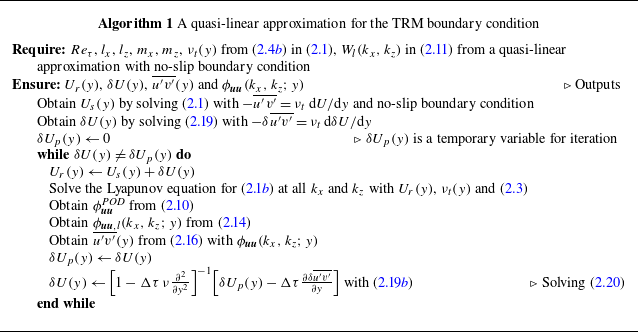

Algorithm 1 A quasi-linear approximation for the TRM boundary condition

Finally, some discussion about the form of

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

is necessary. At first glance, it appears that the form of

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

is necessary. At first glance, it appears that the form of

![]() $\nu _t$

in (2.4b

) would need to be updated as the mean velocity changes during the solution procedure in Algorithm1 – indeed, the form of

$\nu _t$

in (2.4b

) would need to be updated as the mean velocity changes during the solution procedure in Algorithm1 – indeed, the form of

![]() $\nu _t$

originates from the relation

$\nu _t$

originates from the relation

![]() $-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

. However, it is important to note that

$-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

. However, it is important to note that

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

is not for the mean velocity but for turbulent fluctuations. As such, in principle, there is no strict reason why

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

is not for the mean velocity but for turbulent fluctuations. As such, in principle, there is no strict reason why

![]() $\nu _t$

should be changed with the updated

$\nu _t$

should be changed with the updated

![]() $U_r(y)$

. In fact, the most important role of the eddy viscosity in

$U_r(y)$

. In fact, the most important role of the eddy viscosity in

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

is the removal of the fluctuation energy from the integral length scales, mimicking the energy transferred from the integral length scales to the Kolmogorov length scales in real flow (for a detailed discussion, see Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

). Therefore, the update of

$\boldsymbol{N}_{\nu _t,f}$

is the removal of the fluctuation energy from the integral length scales, mimicking the energy transferred from the integral length scales to the Kolmogorov length scales in real flow (for a detailed discussion, see Holford et al. Reference Holford, Lee and Hwang2024b

). Therefore, the update of

![]() $\nu _t$

according to the changes in

$\nu _t$

according to the changes in

![]() $U(y)$

through

$U(y)$

through

![]() $-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

is expected to significantly alter the amount of fluctuation energy removed from the integral length scales; in fact, our attempt to update

$-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

is expected to significantly alter the amount of fluctuation energy removed from the integral length scales; in fact, our attempt to update

![]() $\nu _t$

through

$\nu _t$

through

![]() $-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

yields blown-up solutions, which provides additional evidence that the eddy viscosity only acts as a sink term for dissipating fluctuation energy. To keep the amount of fluctuation energy removed from the integral length scales approximately at the same level, it is therefore decided to fix

$-\overline {u'v'}=\nu _t\, {\rm d}U/{\rm d}y$

yields blown-up solutions, which provides additional evidence that the eddy viscosity only acts as a sink term for dissipating fluctuation energy. To keep the amount of fluctuation energy removed from the integral length scales approximately at the same level, it is therefore decided to fix

![]() $\nu _t$

even with the TRM boundary conditions. If

$\nu _t$

even with the TRM boundary conditions. If

![]() $\nu _t$

is fixed, then the forcing weight

$\nu _t$

is fixed, then the forcing weight

![]() $W_l(k_x,k_z)$

in (2.6) should be kept at the same level. Therefore,

$W_l(k_x,k_z)$

in (2.6) should be kept at the same level. Therefore,

![]() $W_l(k_x,k_z)$

is also set to be fixed with the values obtained from the quasi-linear approximations with no-slip boundary conditions. These modelling choices appear to impose the implicit assumption that the flow operates in the smooth-wall-like regime so that the near-wall turbulent dynamics is not modified structurally. Therefore, they are expected to limit the quasi-linear approximations with TRM boundary conditions to be applicable when the slip and transpiration lengths are modest. In practice, the closure appears to work fairly well in a relatively wide range of transpiration and slip lengths, given the comparisons of the roughness functions modelled with the quasi-linear approximations with those from DNS (see § 3).

$W_l(k_x,k_z)$

is also set to be fixed with the values obtained from the quasi-linear approximations with no-slip boundary conditions. These modelling choices appear to impose the implicit assumption that the flow operates in the smooth-wall-like regime so that the near-wall turbulent dynamics is not modified structurally. Therefore, they are expected to limit the quasi-linear approximations with TRM boundary conditions to be applicable when the slip and transpiration lengths are modest. In practice, the closure appears to work fairly well in a relatively wide range of transpiration and slip lengths, given the comparisons of the roughness functions modelled with the quasi-linear approximations with those from DNS (see § 3).

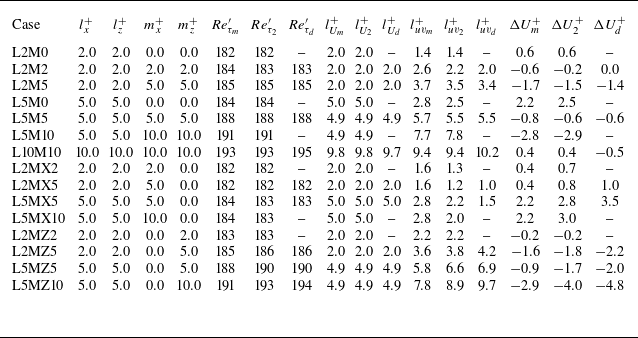

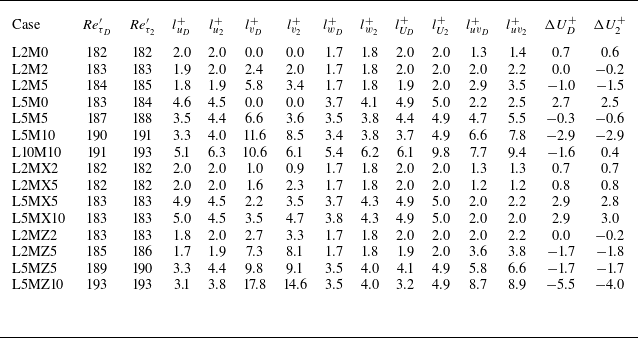

Table 2. Summary of the prediction results with various slip (

![]() $l_{x}^+$

,

$l_{x}^+$

,

![]() $l_{z}^+$

) and transpiration (

$l_{z}^+$

) and transpiration (

![]() $m_{x}^+$

,

$m_{x}^+$

,

![]() $m_{z}^+$

) lengths at

$m_{z}^+$

) lengths at

![]() $Re_{\tau }=180$

. The subscripts

$Re_{\tau }=180$

. The subscripts

![]() $m$

,

$m$

,

![]() $2$

and

$2$

and

![]() $d$

denote the quantities predicted with MQLA, M2QLA and DQLA, respectively. Here,

$d$

denote the quantities predicted with MQLA, M2QLA and DQLA, respectively. Here,

![]() $Re_{\tau }$

is based on

$Re_{\tau }$

is based on

![]() $u_{\tau }$

at

$u_{\tau }$

at

![]() $y=0$

, and

$y=0$

, and

![]() $Re_{\tau }$

with a prime is based on

$Re_{\tau }$

with a prime is based on

![]() $u_{\tau }$

at

$u_{\tau }$

at

![]() $y=-l_{uv}$

with

$y=-l_{uv}$

with

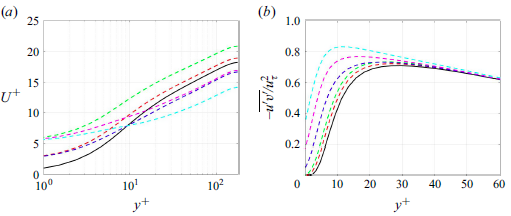

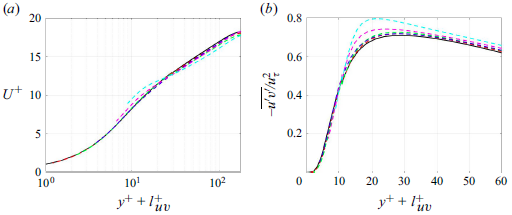

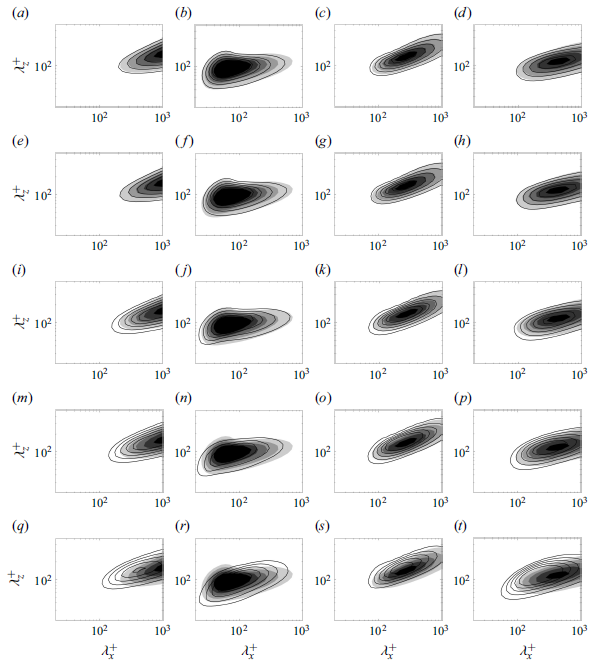

![]() $h'=h+l_{uv}$