Introduction

Political competition in established democracies has changed over the last decades. Issues such as immigration and transnational political integration have gained salience, and new, often right‐wing populist, parties have established themselves. A prominent line of reasoning sees globalization as the ultimate driver of these developments and uses cleavage theory to interpret and systematize them. Accordingly, the changes in the political domain indicate the emergence of a new political cleavage, which may give structure and stability to politics after a period of transformation (e.g., Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008).

Recent contributions to this research programme examine the group psychology of the new cleavage through the lens of identity (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; Helbling & Jungkunz, Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021; Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2022), bringing the general increased interest in the role of identity in politics (Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama2018; Noury & Roland, Reference Noury and Roland2020) to this specialized literature. This new line of research also brings to the forefront ideas that pervade classic cleavage theory (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2000; Bartolini & Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967), namely that identity both drives the formation of political cleavages and ensures their stability. This makes the study of psychological group formation an important task in understanding whether the globalization divides will develop into a full‐blown cleavage. Although recent research has made great strides in this regard (e.g., Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2022), fundamental questions have not yet been conclusively answered, such as which social categories form the basis of this psychological group formation and how advanced it is.

In this article, we contribute to this research programme by studying subjective losers – and winners – of globalization. By this we mean individuals who accept one of these labels for themselves or to use the appropriate term from social psychology (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987), who self‐categorize as losers or winners of globalization. These two categories figure prominently in the academic literature – in fact, the new divide is regularly characterized as a conflict between the ‘winners’ and ‘losers of globalization’ (e.g., de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Helbling & Jungkunz, Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2014). It is important that these are not only employed as analytical categories but that scholars assume that they are used in the real world and are politically relevant there. Kriesi and colleagues (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, p. 4), for example, argue that citizens ‘perceive these differences between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalization, and these categories are articulated by political parties’; according to Pappas (Reference Pappas2016, p. 26), antidemocratic parties thrive on those ‘who see themselves as ‘losers of globalization’; and Börzel and Zürn (Reference Börzel and Zürn2021, p. 286) see the liberal international order challenged by ‘those who perceive themselves as the losers of globalization’.

However, it has not yet been studied whether citizens actually accept these labels for themselves and whether such self‐categorizations are related to other building blocks of the globalization cleavage. This limits our understanding of the globalization cleavage in serious ways. Until this key element is examined, it remains unclear how convincing prominent explanations for some of the most important political developments of our time really are. If we found evidence of the existence of identities of the globalization winners and losers, we would better understand one mechanism of how citizens evaluate the political offer and how political entrepreneurs (can) attract voters – namely, by appealing to their perception of being losers or winners of globalization.

This article contributes descriptive evidence to close these knowledge gaps, drawing on a large (n > 10,000) survey dataset from Germany (GLES, 2019). Utilizing a question on whether individuals see themselves as losers or winners of globalization, we find evidence of a division between globalization losers and winners at the level of subjective group membership that is (partially) rooted in social structure and associated with issue attitudes and party choices. We thereby confirm many of the untested assumptions of previous research: Self‐categorization as loser of globalization is, for example, more likely among individuals with lower levels of formal education, low incomes and residing in poorer regions. Self‐categorization as globalization loser goes along with favouring demarcation regarding international trade, European Union (EU) integration and immigration as well as a high likelihood to vote for the radical‐right AfD. In this way, self‐categorization seems to mediate the effects of social structure to some extent. Yet, we also find that self‐categorizations exhibit shared variance with issue attitudes and party choice beyond the socio‐structural divide. Our findings thus suggest that self‐categorizations are an important phenomenon in their own right, worthy of further research.

Our findings contribute to the literature on social identity and new cleavages by examining, for the first time, self‐categorizations as globalization losers and winners. We do not claim that these categories are the most important – let alone the only relevant ones. But there is much to suggest that they are an important piece in the identity mosaic that is emerging in the context of the new cleavage. This is especially apparent regarding the subjective losers of globalization. Ceteris paribus, negatively valued categories are psychologically unattractive (Huddy, Reference Huddy2001; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979), but they can still be the basis of politically important identities. For example, political communication scholarship suggests that populist messages resonate among individuals only to the extent they identify with an in‐group of ‘deprived ordinary people’ (Hameleers et al., Reference Hameleers, Reinemann, Schmuck, Fawzi, Reinemann, Stanyer, Aalberg, Esser and de Vreese2019, p. 161, also see: Bos et al., Reference Bos, Schemer, Corbu, Hameleers, Andreadis, Schulz, Schmuck, Reinemann and Fawzi2020). Analogously, those who see themselves as losers of globalization might be attracted to parties sending similar messages.

In the next section, we situate our study in research on the globalization cleavage and discuss how self‐categorizations as globalization loser or winner are relevant to it. The subsequent empirical analysis is structured into an analysis of the socio‐structural characteristics of self‐categorized losers and winners of globalization, their issue attitudes and, finally, their vote choices. In the conclusion, we discuss implications, limitations and avenues for future research.

The globalization cleavage and self‐categorized losers versus winners of globalization

Identity plays an important role in the formation and durability of political cleavages (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2000; Bartolini & Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967). Accordingly, collective identities crucially contribute to holding cleavages together. They may glue together individuals with different social characteristics and facilitate ingroup communication. When citizens share, and are invested in, a common understanding of who they are, political elites may appeal to such identities, claiming to represent this collective. In effect, group‐based appeals can be just as important as parties’ policy differences for cleavage voting (Robison et al., Reference Robison, Stubager, Thau and Tilley2021; Thau, Reference Thau2021). In short, full‐fledged political cleavages are characterized by the existence of socio‐structurally rooted social identities that come with certain values, political attitudes and party loyalties.

Whether and how the globalization cleavage is rooted in social identity is not yet settled, despite significant progress that recent studies have made by addressing how different aspects of identity relate to other cleavage elements (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; Helbling & Jungkunz, Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021; Stubager, Reference Stubager2009, Reference Stubager2013; Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2022). This type of work starts out from the broadly accepted understanding of a political cleavage as encompassing a socio‐structural element, a cultural element including both political attitudes and group identity, and an organizational element, which manifests as party preference at the mass level (Bartolini & Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990, p. 215). Within this framework, Stubager (Reference Stubager2013) shows that low‐ and high‐educated Danes differ in their affective attachment to educational groups and that these attachments in turn shape party choice. Bornschier et al. (Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021) offer a sweeping approach, studying attachment to a broad list of 17 social categories in Switzerland (also see: Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2022). These authors document how both attachments to socio‐structural (e.g., educational groups) and culturally connoted social categories (e.g., ‘cosmopolitans’) are rooted in social structure. Relevant to our endeavour, they find that voting for the radical right becomes more likely when feeling close to ‘Swiss people’ and less likely when feeling close to ‘cosmopolitans’ – two categories linked to the notion of a globalization divide.

We contribute to this literature by studying how self‐categorizations as winners and losers of globalization are linked to other cleavage elements. We know little about their relevance to individual citizens, although these ingroup–outgroup categories: (1) feature in public discourse and, even without their salience in communication, (2) they seem like fairly obvious, intuitive categories in the context of globalization to be examined as candidates for identities to develop around. Finally, (3) there are numerous statements in the academic literature that seem to assume their real‐world relevance without studying them empirically, as we will discuss below. By focusing on these categories, we do not mean to suggest that they are the only relevant or even the most relevant ones. We merely claim that their study contributes to our understanding of the identity component of the globalization cleavage.

Before moving on, a conceptual clarification is in order. Following the social identity approach (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987), one should think of social identity as a psychological construct comprised of cognitive, affective and evaluative components (Ashmore et al., Reference Ashmore, Deaux and McLaughlin‐Volpe2004; Ellemers et al., Reference Ellemers, Kortekaas and Ouwerkerk1999). A comprehensive study of globalization‐loser and ‐winner identities would hence entail accounting for all these subcomponents. We have a less ambitious agenda and focus on self‐categorization, the cognitive aspect of whether individuals believe that they themselves are part of a given category or group. Self‐categorization theory (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987) considers self‐categorization as the pre‐condition for developing other components of identity, and, hence, it seems the most reasonable place to start studying the relevance of these ingroup–outgroup categories. It means that we have to be careful when drawing conclusions about the overarching concept of identity, though. This limitation of selective accounting of identity components hampers current work on the identity component of cleavage identities more generally, an issue to which we will return in the conclusion.

References to winners and losers of globalization abound in recent work (e.g., de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Helbling & Jungkunz, Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2014). To substantiate this claim, we focus on Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008)’s pioneering work on the ‘integration‐demarcation cleavage’, in which the notion of a divide between losers and winners of globalization takes centre stage.

In a nutshell, Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) argue that processes of economic, political and societal internationalization affect individuals heterogeneously, thereby giving rise to a structural conflict between the winners and losers of these developments. Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, p. 8, 238) understand these ‘new groups of winners and losers of globalization’ to encompass ‘those social groups that may perceive the process of denationalization as a chance or as a threat, respectively’. Reflecting the multiple facets of globalization, winners and losers are defined in both economic and cultural terms: Globalization losers are individuals who are relative material losers of these transformations or individuals whose value orientations conflict with processes of denationalization (or both). These winners and losers of globalization would form policy preferences accordingly, demanding either integration or demarcation. Parties would take up these demands, appealing to losers or winners via their programmes and – based on these programmatic appeals – winners and losers of globalization would vote for different parties.

In their empirical analysis of this micro‐level argument, Kriesi and colleagues (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) use the socio‐structural markers of education and occupational classes to target globalization losers and winners. In support of their account, they find that those classified as losers of globalization – citizens with lower levels of formal education and unskilled workers – tend to oppose immigration and European integration and vote for parties of the radical right. Whether individuals see themselves as globalization losers or winners, and to what effect, is not part of the empirical analysis.

This omission might reflect a lack of data. In fact, Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) do suggest that citizens themselves make the winner–loser distinction and that parties may use this for their advantage. As one of the assumptions undergirding their analysis, they state ‘that citizens perceive these differences between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalization, and that these categories are articulated by political parties’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, p. 4). While the winner–loser distinction may also serve heuristic purposes, it is clear that whether individuals think of themselves as being affected positively or negatively by globalization is central to their argument.

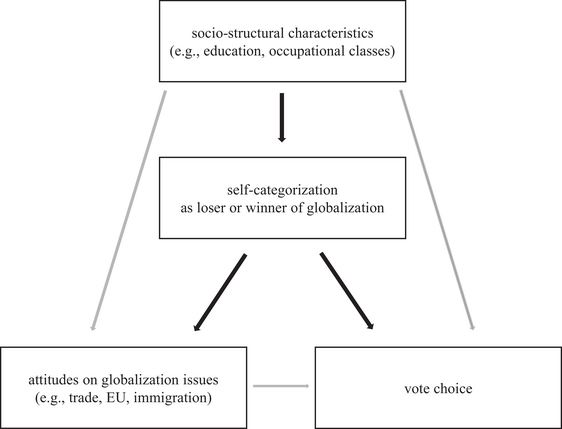

Following up on these ideas, Figure 1 spells out how a micro‐level model of the globalization cleavage, following Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), would look like when incorporating citizens’ self‐categorizations as either globalization losers or winners. Hence, it focuses on the role of these specific self‐categorizations and does not preclude that other self‐categorizations and identities in general, matter as well or that social structure influences attitudes and voting decisions in other ways. It (merely) specifies the idea that self‐categorizations as globalization losers and winners are grounded in socio‐structural divisions and, in turn, shape attitudes and vote choices. Thereby, they may contribute to gluing together socio‐structural roots and political manifestations of the new cleavage.

Figure 1. Self‐categorization as globalization loser/winner and the globalization cleavage.

Note: Model of how self‐categorizations as globalization losers/winners are linked to other elements of the globalization cleavage at the citizen level. Previous work has only assessed the grey arrows. We focus on the black arrows here.

A quantitative exploration further substantiates the claim that the idea of (self‐categorized) losers of globalization features prominently in current research. A Google Scholar search (on 16 November 2022) returns 5,250 hits for ‘losers of globalization’ or alternative spellings, of which more than half are from 2017 onwards. Browsing this literature from different disciplines reveals that scholars routinely write that individuals ‘experience’, ‘perceive’ or ‘see themselves’ as ‘losers of globalization’ (e.g., Beck & Sznaider, Reference Beck, Sznaider, Turner and Holton2010, p. 643; Börzel & Zürn, Reference Börzel and Zürn2021, p. 286; Pappas, Reference Pappas2016, p. 26; de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019, p. 18), thereby implying self‐awareness. No study we are aware of, however, actually tests whether individuals view themselves in these terms – and whether these self‐categorizations are linked to other building blocks of the alleged cleavage as suggested in Figure 1.

Before moving on, three objections are worth discussing. First, one might contend that individuals do not hold meaningful orientations on whether they are losers or winners of globalization. One such concern is that ‘globalization’ is an abstract concept that individuals do not understand.Footnote 1 Another concern applies to the loser category in particular: Given a universal human tendency to avoid ascribing to negatively connotated social categories (Huddy, Reference Huddy2001; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979), self‐categorization as a globalization loser may seem unlikely. In fact, Bornschier et al. (Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021) deliberately exclude negatively connoted ascriptive characteristics from their study on such grounds, assuming that ‘voters usually do not self‐identify as ‘low‐educated’ or as ‘modernization loser’ (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021, p. 2094) as ‘individuals construct their identities in more positive terms’ (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021, p. 2089). While these are important considerations, whether individuals subscribe to negatively valenced categories when confronted with them or not, may still be politically highly consequential. For example, scholars of populist communication claim that populist messages may resonate among individuals only to the extent they identify with such negatively valenced categories in the first place, that is, if they ‘experience a sense of belonging to a deprived in‐group’ (Hameleers et al., Reference Hameleers, Reinemann, Schmuck, Fawzi, Reinemann, Stanyer, Aalberg, Esser and de Vreese2019, p. 147; also see: Bos et al., Reference Bos, Schemer, Corbu, Hameleers, Andreadis, Schulz, Schmuck, Reinemann and Fawzi2020). Likewise, research on ‘rural resentment’ highlights that it might be the combination of identification with rural residents in combination with a perception of this group's relative deprivation that is key to grievance‐based political mobilization (Cramer, Reference Cramer2016; Munis, Reference Munis2022). Thus, before entirely dismissing the relevance of negatively connoted social categories such as the losers of globalization on theoretical grounds, it seems prudent to explore their relevance empirically.

A second objection to Figure 1 is that self‐categorizations are merely epiphenomena of the link between social structure and political attitudes and behaviour and that this link really comes about via a mechanism that is independent of self‐categorization. From this perspective, self‐categorizations as globalization losers/winners may be caused by issue attitudes and/or party preferences rather than affecting those, or both may be simultaneously determined. This objection is serious, in particular in the context of a study that analyses observational data. But there are theoretical considerations that make this charge in its radical version implausible. As discussed above, cleavage theory implies that identity processes are one mechanism why political preferences differ between social groups, and self‐categorizations can matter independently of social structure and policy preferences, for example, when political elites appeal to voters’ senses of being losers of globalization. Due to the limitations of the research design employed here, however, which – following the research design of similar studies (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; Stubager, Reference Stubager2013) – does not allow us to identify causal effects between attitudinal variables, we are unable to resolve the issue empirically. Our scope is more limited, that is, to test whether the data patterns are compatible with the account of Figure 1. We consider this a necessary first step, on which next steps aimed at a better understanding of the causal effects of self‐categorization can build, as outlined in the conclusion.

Third, one might argue that even if the model on the left‐hand side of Figure 1 is correct, it is ultimately not informative to study whether citizens see themselves as losers or winners of globalization. Assuming that self‐categorization is (almost) perfectly determined by social structure, and thus is not relevant beyond social structure in shaping political preferences, it would be enough to study the link between social structure and political attitudes and behaviour – as previous studies have done. This argument does not delegitimize explicit empirical tests of this assumption, though. Such tests may reveal that whether citizens consider themselves losers or winners of globalization may diverge from their objective status and may, as a more immediate cause, better account for divergent political preferences than socio‐structural categories like education, which are commonly used to classify individuals as losers or winners of globalization. If so, including self‐categorizations in our empirical analyses would fundamentally add to our understanding of the globalization cleavage.

In the following empirical analysis, we will show that this is the case. We first provide descriptive findings on self‐categorizations as globalization losers or winners. We then explore the three links suggested by the model on the left‐hand side of Figure 1, following the order suggested by the assumed flow of causality. Moving from top to bottom, we start with the socio‐structural roots of self‐categorizations, turn to their association with issue attitudes next and close with an analysis of regularities in vote choices. We refrain from proposing formal hypotheses here but shortly discuss expectations in each section.

Self‐categorized losers and winners of globalization in the 2017 German Campaign Panel

Our empirical analysis draws on the 2017 Campaign Panel of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES, 2019), which was carried out as an online panel survey in the context of the 2017 German Federal Election. The measure of self‐categorization was included in the last wave, which was in the field in March 2018 and completed by 12,021 respondents. We report results from weighted data, unless indicated otherwise, using a weight based on socio‐demographic information and respondents’ reported voting behaviour (including non‐participation) in the 2017 federal election to best approximate a representative sample of the German electorate.

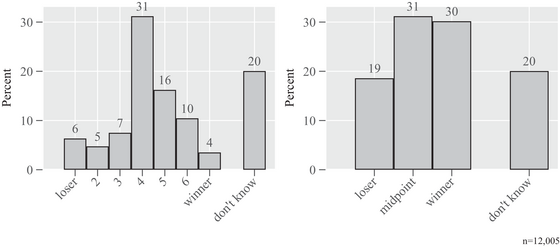

To measure self‐categorization, respondents were asked to answer the question, ‘Do you see yourself as a loser or a winner of globalization?’ using a numbered scale from 1 to 7 (endpoints were labelled 1 ‘loser’ and 7 ‘winner’) or choosing an explicit ‘don't know’ option. Asking individuals directly whether they see themselves as members of a given category, or set of categories, is a standard approach to measuring self‐categorization (Ashmore et al., Reference Ashmore, Deaux and McLaughlin‐Volpe2004, pp. 84–85). It directly captures the core meaning of the concept and can therefore claim content validity. By using a graduated response scale with a neutral middle category and explicitly offering a ‘don't know’ option, we give respondents different options of signalling that they are unable or unwilling to describe themselves as globalization losers or winners. At the same time, we acknowledge that a single‐item measurement cannot fully capture the complexity of self‐categorization. We also cannot rule out the possibility that other considerations than self‐categorization play a role in the formulation of the response. The development of valid measures for these and other components of globalization‐related identities is an important, largely untouched area of research that deserves greater attention in the future.

The measurement result is shown in Figure 2. The left‐hand panel shows the distribution of answers on the original scale. The right‐hand panel shows collapsed categories; answers above the midpoint are combined into a broad winner category, and answers below the midpoint constitute the loser category. About four in five respondents located themselves on the scale provided, while the rest chose the ‘don't know’ option. About half of the respondents provided answers indicating an association with either the losing or winning side. Among those, self‐categorized winners outnumber self‐categorized losers by a ratio of about 3:2.Footnote 2

Figure 2. Self‐categorization as loser or winner of globalization.

Overall, we can conclude that the share of respondents self‐categorizing as either winners or losers of globalization, when asked to do so in a survey, is substantial. This is most notable in the case of the self‐categorized losers, for two related reasons. First, it vindicates scholars’ assumptions that a substantial share of citizens thinks of themselves in these terms, at least when prompted. Second, this is especially remarkable as negatively connotated social categories – and the ‘loser’ label carries this connotation in a most obvious way – are psychologically unattractive. At the same time, it is important to emphasize that self‐categorized losers of globalization are a (sizeable) minority, at least in this German context.

While these descriptive results provide initial evidence that self‐categorizations as globalization losers (and winners) exist, it is a different matter whether they are politically meaningful, that is, whether they play the role stipulated in Figure 1. To address this question, the next three sections present evidence on the three linkages outlined there.

The socio‐structural roots of self‐categorizations

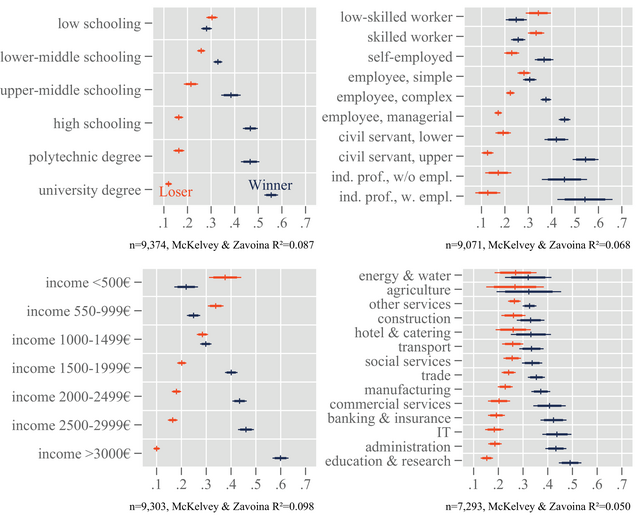

We first address how self‐categorizations are anchored in social structure. Of particular interest here is the correspondence between subjective and objective losers of globalization, as defined in prior work. We hence focus on core socio‐structural variables that, according to prior research, indicate citizens that actually experienced status loss due to globalization. We choose an inclusive approach and map the state of the art as comprehensively as possible (for a recent review, see Ford & Jennings, Reference Ford and Jennings2020). In effect, we look at four individual‐level characteristics (education, income, occupational classes, sector of employment) and one regional‐level variable (socio‐economic inequalities between regions). While this list of variables is still not exhaustive, we can reasonably claim to account for all major theoretical approaches to identifying objective losers of globalization.

First, scholars have used formal education as the key socio‐structural marker to classify individuals into winners and losers of globalization (e.g., de Vries, Reference de Vries2018; de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). Many studies show that citizens with high and low levels of formal education increasingly differ in their attitudes and electoral behaviour (e.g., Bovens & Wille, Reference Bovens and Wille2017; de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Hakhverdian et al., Reference Hakhverdian, van Elsas, van der Brug and Kuhn2013; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Stubager, Reference Stubager2009, Reference Stubager2013).Footnote 3 Partially overlapping with formal education is, second, the distinction of social classes based on individuals’ occupations. Here, scholars typically assume that workers, in particular lower‐skilled production workers, constitute the losers of globalization and that professionals in socio‐cultural, technical and managerial jobs are the winners (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2016; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Oesch & Rennwald, Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). Third, we account for (equivalized household) income as a classic indicator of socio‐economic status. While income has received less attention in studies on the globalization cleavage, arguments for why educational and occupational groups diverge in their views on globalization often point to the different income trajectories of these groups: It is because the low‐educated, or low‐skilled production workers, do (relatively) worse economically in the age of globalization that they dislike globalization, this argument goes (see note 3). As part of our comprehensive approach, we suggest to capture such effects directly by including income. Fourth, we consider the sector of the economy in which individuals work, as some studies suggest that globalization – international trade, in particular – produces winners and losers along sectoral lines (Hays et al., Reference Hays, Ehrlich and Peinhardt2005; Mayda & Rodrik, Reference Mayda and Rodrik2005).

To explore the role of these individual‐level factors in shaping self‐categorizations, we estimate ordered logistic regression models. The dependent variable distinguishes between self‐categorization as loser of globalization, the middle category, and self‐categorization as winner of globalization, with ‘don't know’ responses declared as missing values. As predictors, we distinguish between three levels of formal education, seven levels of income, nine occupational classes and 14 sectors of employment.Footnote 4 Due to the collinearity of the characteristics, we report separate models that account for only one of the four characteristics, respectively. It makes little sense to ask for the ceteris‐paribus effect of being a low‐skilled worker while holding income and education constant, for example, given that low‐skilled workers usually have a low income and lower degrees of formal education (see online Appendix I where we show this for the data at hand). As controls we include age, gender, living in the Eastern part of Germany, and being currently unemployed (see online Appendix A for details). We report the predicted probabilities of self‐categorizing as loser and as winner of globalization in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Social structure and self‐categorization as loser and as winner of globalization [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Predicted probabilities from four separate ordinal logistic regressions with 95 per cent (thin) and 85 per cent (thick) confidence intervals. Additional controls (not shown): age, gender, Eastern Germany, unemployment.

The results in Figure 3 show that those who have been classified as losers of globalization in previous research are also most likely to self‐categorize as such. We find that self‐categorization as globalization loser is more likely among citizens with little schooling, lower income and low‐skilled workers. Among these groups, self‐categorization as globalization loser is as likely or more likely than self‐categorization as winner. This contrasts with socio‐structural categories in which self‐categorization as winner is an order of magnitude more likely than self‐classification as loser: people with university degrees, employees with managerial tasks, and top earners. While sectoral differences are a bit less pronounced, some sectors – such as education and research – stand out with a high likelihood to self‐categorize as globalization winner.Footnote 5

To address the question of objective winners and losers still more comprehensively, we additionally follow recent studies on the political consequences of socio‐economic disparities between regions. These studies show how socio‐economic deprivation at the local level – driven by globalization‐induced and other types of structural economic change – may fuel globalization‐sceptic attitudes and right‐wing populist party success (Broz et al., Reference Broz, Frieden and Weymouth2021; Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Steiner & Harms, Reference Steiner and Harms2023). Evidence suggests that these types of reactions are to some extent sociotropic, taking place even among those individuals not personally affected by socio‐economic disadvantage.

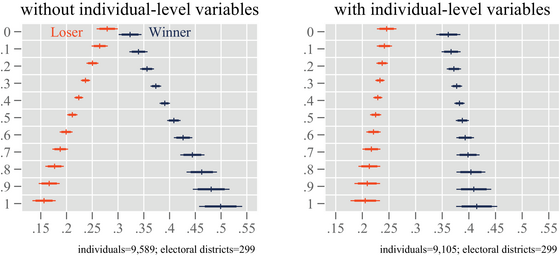

To incorporate the socio‐economic situation at the regional level, we merged – via an electoral district identifier included in the GLES Panel— – a dataset (Bundeswahlleiter, 2021) containing socio‐economic information on electoral districts. From these data, we constructed a principal component score of socio‐economic conditions based on disposable income per capita, gross domestic product per capita, unemployment rate, birth balance (crude birth rate minus mortality rate) and the number of employees subject to social insurance (for details, see online Appendix A). We rescaled this index to range from zero to one. It takes the highest value for München‐Land, covering the suburban parts around Munich and constantly won by CSU candidates since 1953. The lowest value is recorded for Görlitz, Germany's most Eastern electoral district, which was won by the AfD candidate in the 2017 and 2021 elections. We estimated multilevel ordinal logistic regressions, with random intercepts at the level of electoral districts and fixed effects for the federal states (see the regression table in online Appendix C). In Figure 4, we present predicted probabilities of self‐categorization as globalization loser and as globalization winner for different states of the regional socio‐economy.

Figure 4. Regional socio‐economic situation and self‐categorization as loser and as winner of globalization. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Predicted probabilities from multilevel ordinal logistic regressions with 95 per cent (thin) and 85 per cent (thick) confidence intervals.

The probabilities on the left‐hand side are from a multilevel model without individual‐level predictors, showing how the probabilities vary across districts without taking compositional differences into account. Given poor socio‐economic conditions at the local level, individuals are almost as likely to self‐categorize as losers as winners; when these conditions are excellent, individuals are 35 percentage points more likely to self‐categorize as winners. Thus, there are big differences in whether people see themselves as winners or as losers of globalization between more and less prosperous districts.

The probabilities on the right‐hand side are from a multilevel model with now all the individual‐level predictors from above included in addition. They reveal that much, but not all, of the differences between regions are accounted for by compositional effects. The coefficient does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p = 0.07), and the winner–loser gap widens much less. Still, with increasing regional prosperity individuals tend to become less likely to self‐categorize as losers, and more likely to self‐categorize as winners. These results tentatively suggest that the regional socio‐economic situation modestly affects individuals’ self‐categorization on top of their individual characteristics. This contributes to the large regional divides we see in self‐categorization, even though people's own situation plays the bigger role.

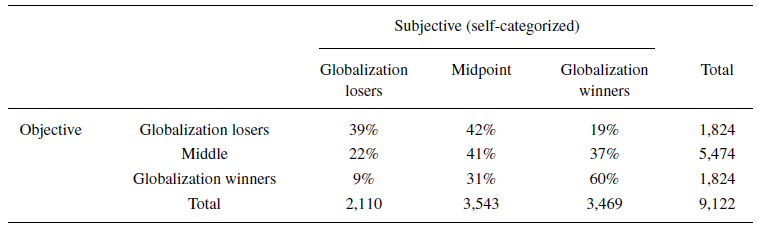

Overall, we can conclude that self‐categorization as globalization loser has social‐structural roots – in line with the left‐hand side of Figure 1. But the association is not perfect, even if we account for all the objective measures at once. We illustrate this with a simple cross‐tabulation (Table 1). We classified respondents as objective losers and winners of globalization based on all the structural variables and crossed this classification with subjective self‐categorization.Footnote 6 Table 1 shows that there are both objective losers that do not see themselves as such and objective winners that do not self‐categorize as winners. We will return to this distinction between objective losers and winners below to contrast differences between subjective versus objective losers and winners of globalization. This allows us to see whether utilizing self‐categorization yields additional leverage in accounting for issue attitudes and party preferences vis‐à‐vis a comprehensive objective classification.

Table 1. Objective versus subjective (self‐categorized) losers and winners of globalization

Note: Entries are row percentages. Objective losers and winners are classified by a regression method that combines education, income, occupational class, sector of employment and the local socio‐economic situation in the electoral district.

Issue attitudes of self‐categorized losers and winners of globalization

The next association of interest is the link between self‐categorization and issue attitudes. The globalization‐cleavage account depicted on the left‐hand side of Figure 1 suggests that self‐categorized losers and winners of globalization primarily differ in their attitudes on issues associated with globalization, that is, international trade and market integration, European integration, and immigration. Relying on objective socio‐economic markers to classify individuals as losers or winners of globalization, previous studies have shown that those with less formal education, as well as production workers, tend to be more globalization‐sceptic across these different facets of globalization (e.g., Bovens & Wille, Reference Bovens and Wille2017; de Vries, Reference de Vries2018; de Wilde et al., Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; on the causal nature of this education divide, also see: Kunst et al., Reference Kunst, Kuhn and van de Werfhorst2020; Kunst, Reference Kunst2022).

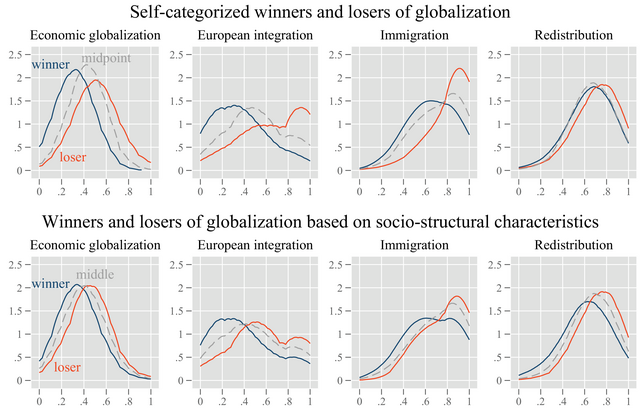

We add to this literature by studying how attitudes vary among self‐categorized globalization losers and winners. Because we are not just interested in differences in means, but in the extent of overlap across groups, we plot distributions of attitudes for the different groups. To do so, we computed mean indices based on items that capture attitudes on three globalization‐related domains – economic globalization (against market integration, restrict imports, against foreign investment), European integration (EU unification) and immigration (restrict immigration, upper limit on refugees, deport economic refugees, foreigners should assimilate). As a point of comparison, we also computed a mean index based on attitudes towards redistribution issues (higher welfare benefits and taxes, reduce income differences, higher taxes for the rich).Footnote 7

Figure 5 plots the distributions of these indices via kernel density plots. The upper part distinguishes between self‐categorized losers and winners of globalization. It shows that attitudes on all three globalization‐related issues are sorted by individuals’ self‐categorizations as globalization losers or winners, with the middle group falling in between. These differences contrast with redistribution, where the differences are much smaller. Interestingly, although self‐categorized losers tend to be socio‐economically disadvantaged (see the previous section), they are only marginally more supportive of redistribution than self‐categorized winners. Very much in line with their self‐categorizations as losers or winners of globalization, these groups primarily differ in their attitudes on globalization issues. In the lower part of Figure 5, we repeat the analysis using the classification of objective losers and winners introduced above (see Table 1). While there are similar differences between losers and winners regarding attitudes on globalization‐related issues across all three domains based on the objective classification, they are less pronounced than with the subjective classification.

Figure 5. Issue attitudes (mean indices) of globalization losers versus winners. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Kernel density curves (Epanechnikov).

Vote choices of self‐categorized losers and winners of globalization

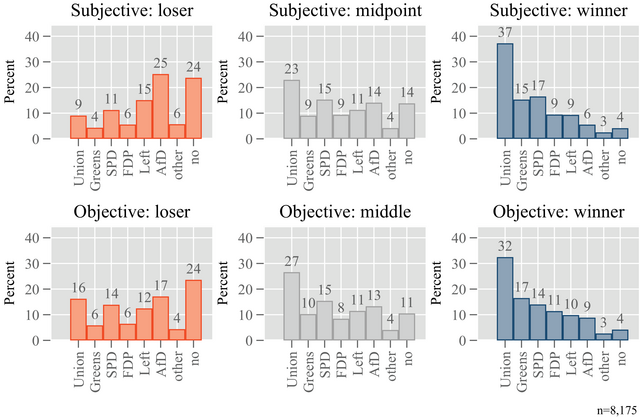

Turning to the third and last association, we study how self‐categorized globalization losers and winners differ in their vote choices. Based on previous studies (e.g., Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010; de Vries, Reference de Vries2018; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Mader et al., Reference Mader, Steiner and Schoen2020), self‐categorized losers of globalization are expected to favour the radical right – in the German context: the AfD – and to do so at the expense of the established mainstream parties. In contrast, the latter should be particularly popular among self‐categorized winners of globalization.

Party leaders, for example then chairman Gauland (Reference Gauland2018), have openly portrayed the AfD as a voice for those losing out from globalization. In an internal AfD strategy paper for the 2017 federal election campaign, ‘citizens with below average income (‘ordinary people’) in precarious districts […] who feel as losers of globalization’ (AfD, 2016, p. 4; authors’ translation and emphasis) are listed as one of the party's key target groups. Clearly, the party attempts to mobilize voters who can relate to such descriptions – and such appeals may resonate with voters who perceive themselves as losers of globalization.

The upper part of Figure 6 shows voting intentions by self‐categorization. The differences across the groups are large, especially in the case of the AfD: Its share is 19 percentage points higher among self‐categorized globalization losers than among self‐categorized winners. Among self‐categorized losers, the AfD is by far the strongest party; if they intend to vote, about a third opt for the AfD (33 per cent). Conversely, almost half of all AfD supporters self‐categorize as losers of globalization (45 per cent). Beyond the radical‐right vote, self‐categorized losers are also more likely to intend to vote for the socialist The Left and one of the other minor parties, as well as to report no intention to vote. In contrast, the mainstream parties, especially the Christian‐democratic CDU/CSU (Union) and the Greens are much stronger among self‐categorized globalization winners as compared to losers. Party preferences of those self‐categorizing in the middle fall in between self‐categorized losers and winners.Footnote 8

Figure 6. Vote intention by subjective (self‐categorized) and objective loser/winner status. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The lower part of Figure 6 reports analogous findings for objective losers and winners, drawing again on the distinction from above. There are similar patterns as among subjective losers and winners, yet the differences are less pronounced. For example, the AfD also is the most popular party among objective losers, but only marginally more popular than the CDU/CSU. Among self‐categorized losers, in contrast, there are almost three times more AfD than CDU/CSU supporters. As we have seen for issue attitudes above, the subjective distinction between self‐categorized losers and winners is much better able to account for divergent political preferences than an objective distinction based on socio‐structural characteristics, even if the latter encompasses several such characteristics.Footnote 9

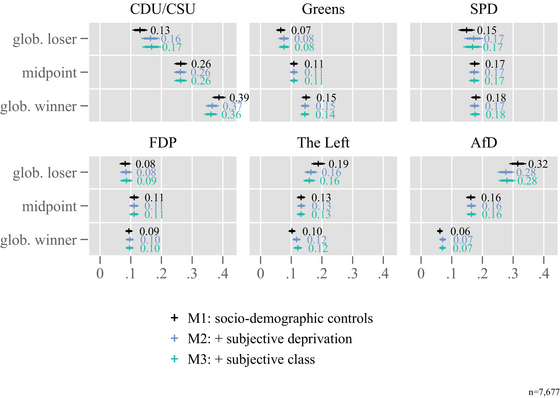

In the next step, we analysed voting intentions – excluding those without an intention to vote – using multinomial logistic regressions. Figure 7 displays the predicted probabilities for self‐categorized losers and winners from three models: model M1 includes all the socio‐demographic controls already used in section three, M2 adds subjective economic deprivation and M3 adds subjective class membership.

Figure 7. Vote probabilities by self‐categorization as globalization loser versus winner. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Predicted probabilities of vote intention with 95 per cent (thin) and 85 per cent (thick) confidence intervals from multinomial logistic regressions, where ‘other’ is another outcome category (not shown). Demographic controls: education, occupational class, income, sector of employment, socio‐economic situation in an electoral district, age, gender, Eastern Germany, and unemployment. McFadden Pseudo‐R 2 is 0.046 with the socio‐demographic controls only, 0.073 in Model 1, 0.084 in Model 2 and 0.088 in Model 3.

M1 mirrors the large differences in vote choices of self‐categorized globalization losers and winners reported in Figure 6. These are especially large in the case of the AfD: The probability of self‐categorized winners to vote for the AfD is 6 per cent, among self‐categorized losers it is 32 per cent. Here, too, the picture is reversed in terms of voting intentions for the Greens and the CDU/CSU. The addition of self‐categorization as globalization loser/winner almost doubles the model fit compared to a model containing only the socio‐demographic variables and – in line with the mediation argument – reduces the impact of the structural predictors.Footnote 10

Do the results for self‐categorizations merely reflect a general sense of where one stands in the societal hierarchy (cf. Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020), having little to do with globalization per se? The predicted probabilities from M2 and M3 suggest that this is not the case. Differences in vote probabilities remain large, especially in the case of the AfD, when we include an item on respondents’ assessments of whether they get a ‘fair share’ (M2). Moreover, while the two variables covary, there remains independent variance (see online Appendix F). The results remain stable even when we additionally control for subjective social class membership (M3). While self‐categorized globalization losers are more likely to see themselves as ‘lower’ or ‘working class’, this association is also far from perfect (as shown in online Appendix F). What is more, self‐categorization as globalization loser/winner is a stronger predictor of voting intentions than self‐categorized social class. In this sense, the ‘new’ globalization cleavage trumps the ‘old’ class cleavage.Footnote 11

Discussion and conclusion

One of the most important theories about contemporary political change in developed democracies is that a new cleavage is emerging between the winners and losers of globalization. The ‘losers’ have a special role in this account, as their reaction to the negative effects of globalization creates a particular potential for political change. But despite scholars’ frequent reference to this group, prior work has not studied whether people actually accept this label for themselves, and, if so, to what effect. This omission has rendered previous tests of this particular globalization cleavage thesis incomplete, as the existence of these self‐categorizations – and corresponding, fully developed identities – has only been conjectured, but never directly examined.

In this article, we contribute to closing this research gap. We find that a sizable minority of individuals – roughly a fifth of German eligible voters – self‐categorize as losers of globalization. We also find that these self‐categorizations are rooted in social structure, as suggested by previous research: Holding lower levels of education, earning low income, being a low‐skilled worker and, more tentatively, living in a poor region, all increase the likelihood of self‐categorizing as globalization loser. Self‐categorizations, in turn, seem to be politically relevant: Self‐categorized losers and winners hold distinctive positions on issues related to globalization, and they strongly differ in their party preferences. In the German context we studied, about a third of self‐categorized globalization losers with a vote intention support the radical‐right AfD, while only 6 per cent of the self‐categorized winners do so.

There are two broad lessons to be learned from our results. First, we confirm previous scholarship. Our findings are in line with ideas about the divide between winners and losers of globalization (see Figure 1). By explicitly examining self‐categorization, we can verify a number of untested assumptions of previous research – about who self‐categorizes as loser and winner of globalization, and how these groups differ in their political views. Overall, our results support the idea of a meaningful divide between these groups. In this account, identification with these categories glues socio‐structural characteristics, political attitudes and behaviour together and thereby provides structure and stability to an emerging globalization cleavage.

Second, we provide evidence suggesting an independent role of identity that has not been adequately addressed in prior research on the globalization cleavage. Our data show that the correlation between objective and subjective losers is not that high and that there is no deterministic link between social structure and self‐categorization. Moreover, the subjective distinction between losers and winners of globalization is better able to account for issue attitudes and party preferences than the objective distinction. All of this suggests that how citizens see themselves is not a mere epiphenomenon of social structure but can have independent effects in the political realm.

Our study hence underlines the importance of identity for the emergence of a globalization cleavage, a point made in a similar vein elsewhere recently (Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; Helbling & Jungkunz, Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2022). We have added to this emergent literature by studying a category pair that has been much discussed in academic research but has not received empirical scrutiny. Our results complement the findings of Bornschier et al. (Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021) and Zollinger (Reference Zollinger2022) that voting for the radical right is related to affective attachment to ‘Swiss nationals’ as well as to ‘down‐to‐earth’ and ‘simple’ people, and to feeling distant from ‘cosmopolitans’. How important the dichotomy of globalization winners and losers is relative to these other social categories remains an open empirical question. In any case, the dichotomy provides a bridge to the literature showing that radical right‐wing populists often mobilize voters who perceive themselves as disadvantaged (Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer, Reference Kurer2020). Our findings show that ‘globalization loser’ is a category that citizens may identify with and that political entrepreneurs can use to mobilize them.

The results of this study, as well as its limitations, provide several opportunities for future research. First, we need comparative research to ascertain whether our findings for Germany are generalizable. The conditions in Germany are not particularly conducive to a strong political divide between subjective losers and winners of globalization, which is why the general patterns we found in the German case should also apply in other countries.Footnote 12 But of course this case study is over‐determined – period effects such as the refugee crisis might influence our findings – and only more data from other cases (countries and time periods) will clarify this issue.

Second, future research should study the identification as globalization losers/winners, and related categories, more comprehensively. Our focus has been on self‐categorization, that is, the most fundamental (cognitive) identity component of awareness of belonging to a social group, which is a necessary but not sufficient condition for having a full‐blown identity. We would expect that not everybody who self‐categorizes as a loser of globalization feels deeply about this group membership, for example, and that those who do, exhibit stronger associations between identity components and party preferences. We also have no data on how respondents cognitively represent the losers and winners of globalization groups, that is, what they consider to be prototypical characteristics of category members. In sum, future research on the identity component of the globalization cleavage should draw more explicitly on conceptual insights of the social identity approach and utilize measurement instruments developed in that literature (for a review, see Ashmore et al., Reference Ashmore, Deaux and McLaughlin‐Volpe2004).

Third, future research should use causal identification strategies to make robust statements about what influences what. While the substantive questions we are interested in are of a causal nature, the cross‐sectional evidence presented here does not demonstrate causality. As such, the findings are in line with certain causal accounts without proving them. To do the latter, experiments could be devised to study the formation of these new, globalization‐related identities, as well as their activation, while holding constant other relevant factors, such as the issue positions of the political elites.

Fourth, future research should provide a comprehensive account of how self‐categorizations as winners and losers are formed. Why is it, for example, that some individuals who do not objectively qualify as losers of globalization still self‐categorize in that way? We suspect that such differences between subjective and objective losers result from an interaction between psychological traits of individuals and elite rhetoric that incites such perceptions. Providing such a comprehensive account also includes a clarification of the relationship between the identification as globalization losers and winners and more general perceptions of one's social status. We see this as part of a broader endeavour to fruitfully connect two major strands of literature on the rise of the radical right that have existed largely in parallel, namely the globalization cleavage perspective and studies on social status and right‐wing populism (e.g., Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer, Reference Kurer2020).

Fifth, and relatedly, we need a better understanding of political ‘identity leadership’ (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Reicher and Platow2020; Reicher et al., Reference Reicher, Haslam and Hopkins2005). Beyond the case of party identity, we know little about the role of elites in the formation and activation of identities in the political arena. Evidence of how party rhetoric stimulates cleavage voting via identity‐based mechanisms is only beginning to emerge (Robison et al., Reference Robison, Stubager, Thau and Tilley2021; Thau, Reference Thau2021) and is completely lacking with respect to the emerging globalization cleavage. Thus, while our results imply that political entrepreneurs may use the ‘globalization loser’ category to activate the diverse political potentials that structural changes associated with globalization have created (cf. Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), we lack a detailed understanding of how they do so and to what effect. The politically successful use of this designation may depend on a narrative that places the blame for low status – for belonging to a low‐status group – on outgroups such as elites or foreigners. There are well‐known examples of such rhetoric. In his 2017 inauguration speech, Donald Trump, for example, addressed the ‘the forgotten men and women of our country’, a middle class whose wealth ‘has been ripped from their homes and then redistributed all across the world’ (see Politico, 2017). Similar appeals are a cornerstone of Marine Le Pen's rhetoric who claims to represent ‘la France des oubliés’, the France of the forgotten (see Chrisafis, Reference Chrisafis2017). Such rhetoric may resonate with individuals who view themselves as losers of globalization and may even lead individuals to self‐categorize in that way. Yet, important questions remain about how such self‐categorizations develop into social identities and how exactly political entrepreneurs may use negatively valenced social categories to their advantage.

Funding Information

Harald Schoen has received funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) [SCHO 1358/4‐3].

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank participants of the 2021 Annual Meeting of the ‘Elections and Political Attitudes’ section of the German Political Science Association (DVPW) and the ‘Democracy Colloquium’ at JGU Mainz as well as EJPR's four anonymous reviewers for insightful and constructive comments on previous versions of this article. Larissa Böckmann and Tim Schmidt provided excellent research assistance.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability statement

Reproduction materials for this article are available at Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WIHAOV.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information