In 2017, the authors supervised the recovery of a pre-Hispanic stone sculpture near the community of La Victoria, in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas, southern Veracruz, Mexico. Although similar monuments had been reported from the same area (e.g., Blom and La Farge Reference Blom and La Farge1926; Seler-Sachs Reference Seler-Sachs and Lehmann1922), this salvage project represented the first occasion to explore the in situ archaeological context of this sculptural corpus. As important, the fieldwork offered an excellent opportunity to wed governmental oversight and academic interests with the concerns of local stakeholders regarding the retrieval and final disposition of the monument.

We discuss this salvage project below, providing both historical context regarding its discovery as well as archaeological context involving its excavation. We begin with the initial reporting of the find, and we review prior research that speaks to the monument's importance. The sculpture, a solid basalt block with carved designs, may have served as a stela base (e.g., Arnold and Budar Reference Arnold, Budar, Englehardt and Carrasco2019; Budar et al. Reference Budar, Arnold and Becerra2024) and was originally positioned atop a small platform adjacent to a natural spring.

We then present the salvage project's research design and excavation strategy, underscoring the involvement of local residents. Archaeological research in southern Veracruz can have unintended political consequences (e.g., Grove Reference Grove2014), so this participation was crucial to the successful recovery of the monument. Finally, we detail the sculpture's ultimate relocation to a local community building, where it is currently housed and displayed. Taken together, this collaborative effort provided an extremely favorable occasion to investigate, conserve, and appreciate a hitherto poorly documented Early Classic–period (a.d. 300–450) sculptural tradition from the southern Gulf Lowlands of Mexico.

The fortuitous discovery

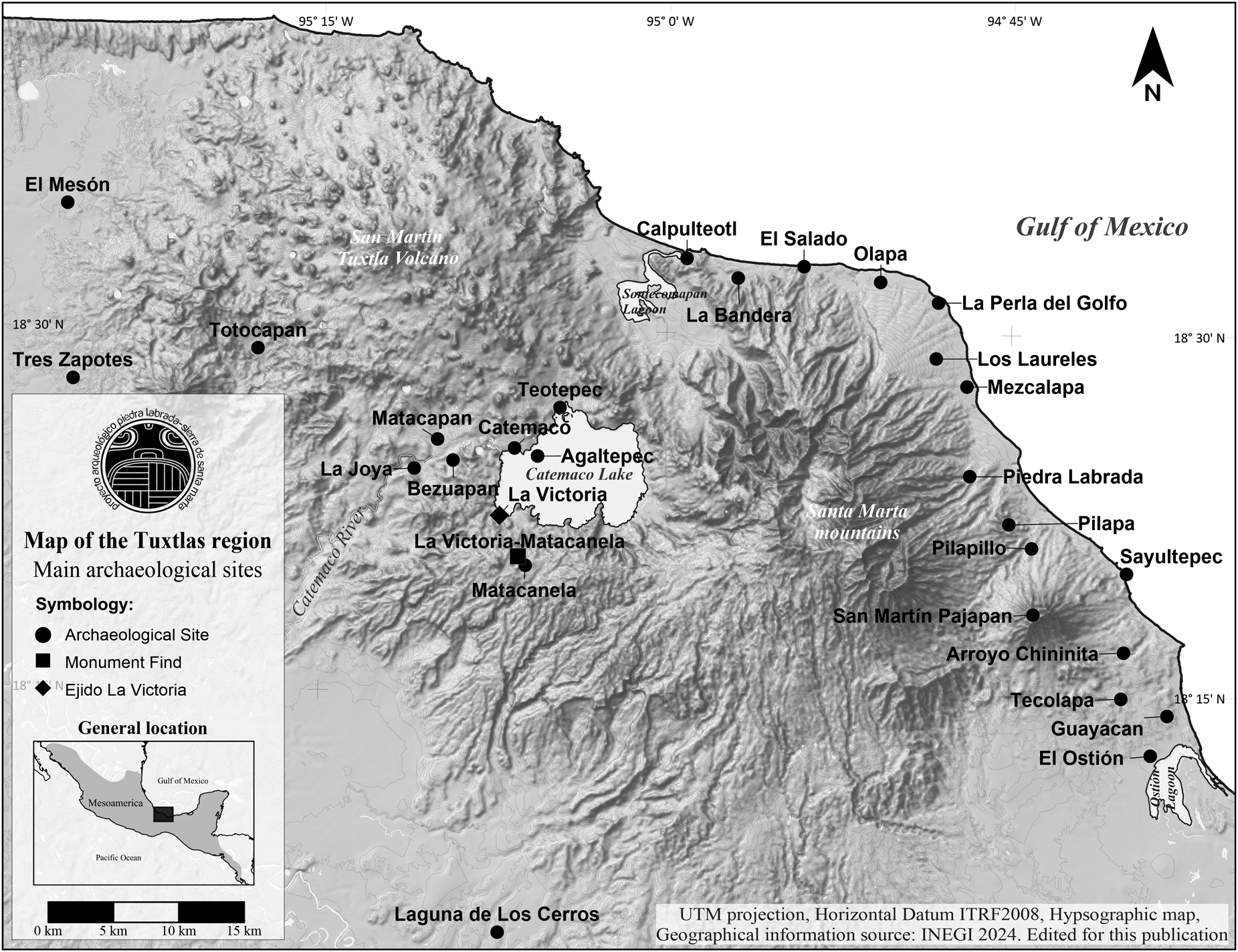

In the spring of 2017, the Veracruz, Mexico, office of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH Centro Veracruz) received word of a fortuitous discovery. This unexpected find involved a stone monument that was located on the communal ejido—a type of agrarian social property—lands of La Victoria, a small community located in the Catemaco Municipality of the Sierra de Los Tuxtlas in southern Veracruz (Figure 1). According to this report, field hands hired by the landowner had found the sculpture, and it was now at risk of destruction or looting. The news was immediately communicated to both the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia's (INAH) Consejo de Arqueología (Council of Archeology) and Marcie L. Venter of Murray State University, Kentucky. Venter was the director of the Matacanela Archaeological Project, and the monument was found only 200 m outside of the project boundaries that had been established for her investigation of the Matacanela archaeological site (Venter et al. Reference Venter, Shields and Cuevas Ordóñez2018).

Figure 1. Map of the region and the main archaeological sites. Edited by the authors.

Consequently, at the request of the INAH Centro Veracruz, and with Venter's knowledge and consent, Lourdes Budar of the Universidad Veracruzana, who was already conducting nearby field investigations as part of her Piedra Labrada-Sierra de Santa Marta-San Martín Pajapan Volcano Archaeological Project, carried out an inspection of the reported find site. Budar's conversations with the landowner confirmed the landowner's knowledge of the discovery and his desire to cooperate with INAH in order to mitigate the possibility of looting. Budar was also able to verify the condition and in situ context of the monument, which had been covered with dry vegetation in an attempt to conceal its location. Photographs were taken, and the monument was georeferenced, which established that no significant georeferencing had been performed, and that no significant contemporary damage to the sculpture had occurred. Budar used this information to generate a preliminary report to INAH Centro Veracruz as well as INAH́s national Consejo de Arqueología (Budar Reference Budar2018).

Consequently, INAH Centro Veracruz formally requested a meeting with the ejido authorities of La Victoria at which INAH lawyers would be present. The goal of this reunion was to insure that, at the conclusion of Budar's 2017 field season in the nearby Sierra de Santa Marta area, the salvage of the monument could take place. Therefore, the immediate response of the INAH authorities in conjunction with the initiative and collaboration of the La Victoria community enabled a team of archaeologists from the Universidad Veracruzana to implement a research strategy that would protect the monument and preserve its important contextual information.

The La Victoria-Matacanela sculptural complex: Historical background

Between 1887 and 1911, Eduard Seler and Caecilie Seler-Sach made six trips to explore archaeological sites throughout the Mexican Republic (Sepúlveda y Herrera Reference Sepúlveda y Herrera1992). Seler-Sach was in charge of keeping notes, taking photographs, and describing their trips and findings. All of these data were sent to Berlin, where they were kept for study and eventual publication. During their fifth trip, in 1907, the Selers visited several locations in the Tuxtlas region, which included spending two weeks at the Matacanela hacienda. While at Matacanela, they recorded five monuments (Seler-Sachs Reference Seler-Sachs and Lehmann1922), some of which are similar to the one that serves as the basis for the present discussion.

Almost two decades later, Walter Lehmann (Reference Lehmann1922) compiled and published much of the Selers’ work. The comments surrounding the Matacanela sculpture were written by Caecilie Seler-Sach; they include a photograph and a brief description of five pieces, which she associated with the Matacanela hacienda but for which she offered no additional information about their origin or context:

The Rancho Matacanela is located high above the pretty lake of Catemaco. We saw a number of stones there with petroglyphs. Besides several rather rough depictions of figures were other squared incisions with a mortice hole, as if they had been pedestals for figures. They had special kinds of decorations: some showed on each side three simple, deeply engraved circles or rings…and one was decorated on all four sides with two each mollusk shells, completely giving it the character of pieces of Renaissance workmanship [Seler-Sachs Reference Seler-Sachs, Thompson and Richardson1996:x–xi].

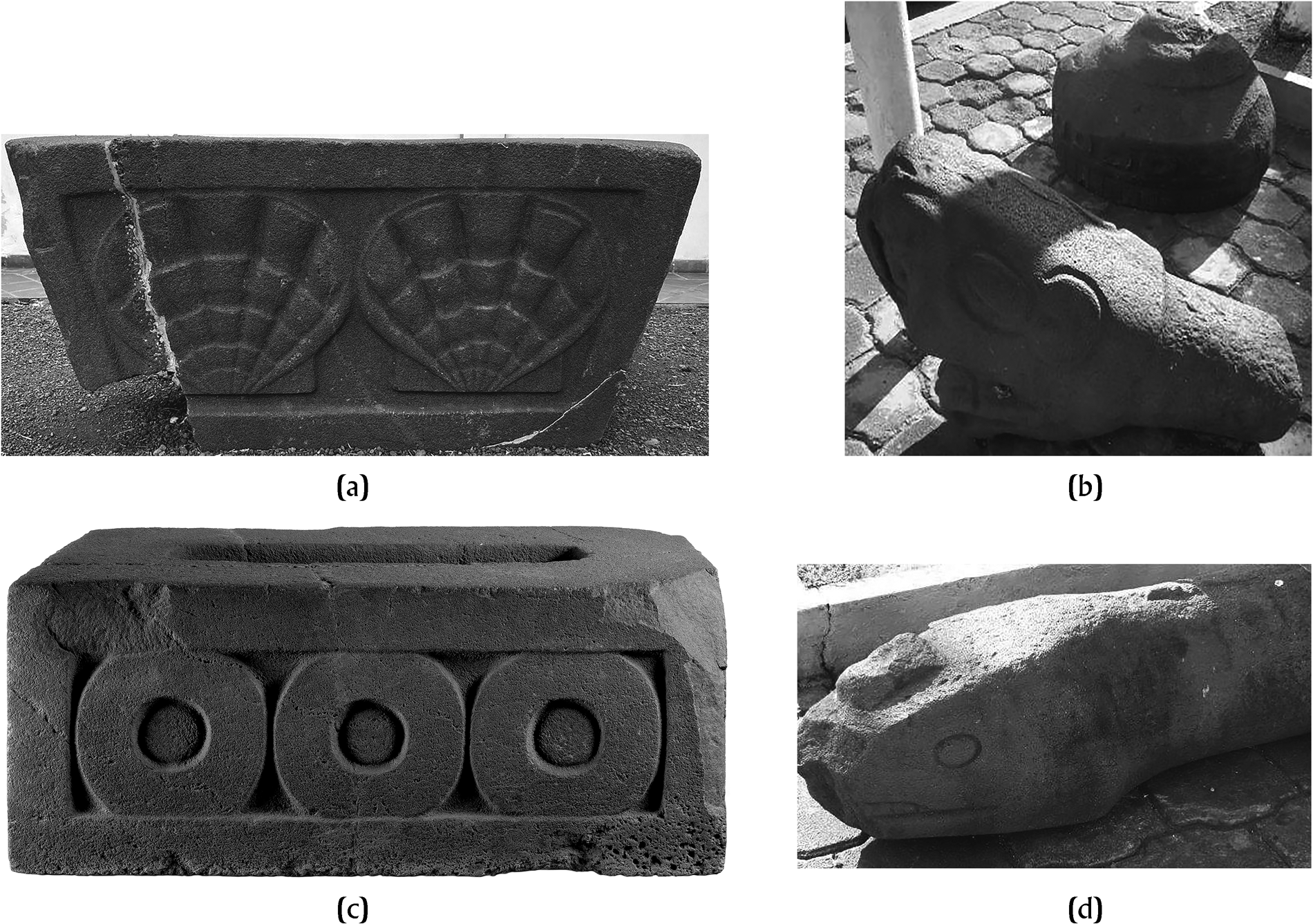

In 1925, Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge initiated their renowned Tulane Expedition, beginning their overland route in the Tuxtlas region. During this early part of their journey they photographed the five Matacanela sculptures and subsequently published them in their Tribes and Temples account (Blom and La Farge Reference Blom and La Farge1926) (Figure 2). They also included descriptions and comments about the sculptural corpus, including the following:

Sunday morning we got a small gasoline launch and crossed the lake [Catemaco] to Finca La Victoria […] At La Victoria on the east shore of the lake, Mr. Hagmaier had arranged for horses, and soon we were in the saddle on our way to Matacanela….The trail wound steeply up a mountain side, and the lake lay like a beautiful panorama below us. Then we crossed a small range and rode in high forests. Gradually climbing, after about half an hour's ride, we reached the small finca Matacanela, where Seler is reported to have made excavations, though we have not been able to locate a description of these. Mrs. Seler mentions some stone figures, and we found these in front of the main house. They had been brought there by some captain in the rebel army and set up very nicely, where they remained until a few years later when some government troops arrived and scattered them. We found several stone boxes, also a few pieces of sculpture. Among the latter was another rabbit, or at least the fore-part of a rabbit, with the legs and part of the body complete…The stone boxes were decorated on all four sides, one with some excellently carved bivalve shells (Pecten) and another with a row of circles…A crude stone serpent's head lay close to a small palm hut and with the stone boxes stood a circular stone altar on a base. All these objects have been carved out of volcanic rock, and they show unusual skill in the stone mason's art [Blom and La Farge Reference Blom and La Farge1926:22–23].

Figure 2. Contemporary photographs of sculptures reported by Blom and La Farge in Tribes and Temples (1926): (a) trapezoidal base with representation of shells, currently located in the Tuxteco Museum of Santiago Tuxtla, Veracruz; (b) architectural tenon in the shape of a rodent head and circular monument, currently located in front of the City Hall in Catemaco, Veracruz; (c) quadrangular base with representation of circles, currently located in the Xalapa Museum of Anthropology, Veracruz; (d) architectural tenon in the shape of a snake head, currently located in front of the City Hall in Catemaco, Veracruz. (after Budar Reference Budar2018:6) Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

Years later in 1938, Juan Valenzuela and Karl Ruppert spent two weeks at Matacanela conducting test excavations. Their ultimate goal was to understand the history and influences of the Mayan and Teotihuacan cultures in the Tuxtlas region, but they also mentioned the presence of these same stone monuments:

In this area, mounds of earth that form isolated groups are very abundant. The main system is made up of two large elongated mounds running from north to south, having all the characteristics of a ball court; they are closed to the north by a large conical mound and to the south by another elongated mound of very low height. In order to see if we could find some construction data in the elongated mounds, Mr. Karl Ruppert made some fairly deep trenches from east to west but he could not find any walls or ceramic objects…The area is very interesting, both for the number of mounds and for the very fine engraved stones that have been found there; some of them are now abandoned on the road between the La Victoria hacienda and Mata de Canela, and were made known by Blom, in his work Tribes and Temples [Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela1945:91; authors’ translation].

Consequently, during the first half of the twentieth century, three different research projects mentioned the suite of Matacanela monuments. It is also interesting that Blom and La Farge (Reference Blom and La Farge1926:23) suggested that the Selers may have carried out excavations at the site. If accurate, this comment implies that the sculptures themselves may have derived from an excavated context, although there is no published documentation of any such activity. In fact, Seler-Sachs's (Reference Seler-Sachs and Lehmann1922) own notes do not refer to excavations, although it should be remembered that her work appeared in a compendium later edited and published by Walter Lehmann (Reference Lehmann1922), who may have omitted some data that he considered extraneous (Thompson and Richardson Reference Thompson, Richardson and Comparto1996:xix, n1).

Blom and La Farge (Reference Blom and La Farge1926:23) indicated that the sculptures were moved to the entrance of the main house of the Matacanela hacienda by a “captain in the rebel army,” and were later “scattered” by “government troops,” whereas Valenzuela (Reference Valenzuela1945:91) pointed out that in 1938, the monuments were abandoned on the road between La Victoria and Matacanela. Seler-Sachs (Reference Seler-Sachs and Lehmann1922) only said that the monuments were on the plantation. In this regard, it is noteworthy that both Venter and our team from the Universidad Veracruzana conducted systematic surveys in an attempt to identify the foundations of the main Matacanela house mentioned by Blom and La Farge (Reference Blom and La Farge1926:23), but so far, we have been unsuccessful.

The historical archives in this case are of little help in locating the Matacanela house, because they identify the La Victoria hacienda, which was located on the shores of Lake Catemaco, but they do not specify Matacanela itself. However, all of the early twentieth-century researchers mentioned above agree that the archaeological site was located on the grounds of the La Victoria hacienda. Interestingly, there is no nearby locale currently named “Matacanela,” Instead, there is the contemporary town of Zapoapan de Cabañas, immediately adjacent to the archaeological site where Valenzuela and Ruppert—and more recently, Venter—worked. Some contemporary La Victoria residents claim that “the owner” of the old La Victoria hacienda had a family out of wedlock and built a simple wooden house for that family's use. According to this account, the common local directions to arrive at the house and associated fields involved going to the “cinnamon bush”—Mata de Canela (Matacanela)—precisely the name used by all of the early explorers to refer to the archaeological site.

In her analysis of historical archives, Rubí Pucheta (Reference Rubí Pucheta2021:81–83) was able to determine that the La Victoria hacienda was active from colonial times until the 1930s. Officially, the La Victoria hacienda had an area of just over 2,843 ha, and it was based on a mixed economy that included agriculture, livestock, and the extraction of fine wood for international trade. There was also a company store for a workforce that included indigenous laborers, mestizos, and Afro-descendants.

In the colonial era, the hacienda belonged to Manuel Pereyra, a Cuban national. It was later acquired by Juan Simón Rodríguez, and in 1892, it was sold to the brothers Ricardo and Ernesto Leoni—owners of the San Andrés Tobacco company. The Leoni brothers never lived there nor were they directly involved in the affairs of the La Victoria hacienda; instead, they delegated responsibilities to different administrators over time, all of German origin (Rubí Pucheta Reference Rubí Pucheta2021). Between 1892 and 1900, it was managed by Ricardo Erasmi, and between 1900 and 1927, it was overseen by Jacob Hagmaier. It was Hagmaier who received the Selers as well as Blom and La Farge. Jorge Weigelt was in charge from 1927 to 1936, and it was during his tenure that Mexico's agrarian reforms were instituted (Rubí Pucheta Reference Rubí Pucheta2021:81–83). When Valenzuela and Ruppert arrived in 1938, the area was in the midst of a major territorial and social readjustment that converted a nineteenth-century plantation into communal property. So it is possible that the main house of the Matacanela hacienda was built after 1907 and dismantled before 1937.

The collection of Matacanela sculpture reported by explorers remained in the area until the 1960s, at which point the monuments were moved to different locations. The precise dates and circumstances of these relocations are unknown; it has not been possible to find records or documentation like those that exist for other regional cases, including Monument 1 of San Martín Pajapan (Medellín Zenil Reference Medellín Zenil1968) and Stela 1 of Piedra Labrada (Zepeda et al. Reference Zepeda, Budar and de Guevara2010). We do know, however, that two of the documented “boxes” were transferred to museums: the one with shell-shaped relief was moved to the Tuxteco Museum of Santiago Tuxtla, and the one with circles went to Xalapa's Museum of Anthropology (MAX), which is part of the Universidad Veracruzana system. The best-preserved zoomorphic (rodent) monument was transported to San Andrés Tuxtla, and the remaining sculptures—including a snake, a rodent, and a circular column base—were placed along the main street of Catemaco, leaving the known sculptural corpus fully dispersed.

During the 1990s, the Mexican government implemented The Certification Program for Ejido Rights and Land Titling (PROCEDE), which was dedicated to: “providing certainty and legal security over the ownership of land of social origin, through the certification of parcel rights and common use, as well as the titling of urban plots”, (Reglamento de la Ley Agraria en materia de certificación de derechos ejidales y titulación de solares 1993). Starting in 1996, INAH participated in this federal program and oversaw the identification, registration, and zoning of archaeological sites located in the community ejidos throughout the country (Sánchez and Sánchez Reference Sánchez Nava and Sánchez Alaniz2001:18–19). In Veracruz, thousands of archaeological sites were registered and their areas delimited. Matacanela was catalogued as containing 15 monumental earthen structures distributed among the ejido lands of La Victoria, Pozolapan, Ahuatepec, and Zapoapan de Cabañas (Heredia Barrera Reference Heredia Barrera2007; Venter Reference Venter2014).

In 2014, Venter initiated the first systematic archaeological investigations at Matacanela. Venter's Matacanela Archaeological Project (MAP) was designed to “carry out the analysis of the social collapse that took place in the region of Los Tuxtlas during the Classic period and the reorganization that occurred during the Postclassic, through the systematic study of the site of Matacanela” (Venter Reference Venter2014:2). The MAP's systematic, controlled survey covered approximately 5.3 km2, and excavations were conducted in off-mound loci distributed mostly throughout the site's main architectural nucleus. These efforts also produced the first topographic map of the site, which documented 22 structures arranged around several plazas (Venter et al. Reference Venter, Shields and Cuevas Ordóñez2018). Excavations revealed that the site dated to at least the Middle Formative period (ca. 900 BC) with occupation continuing through the Late Classic (ca. AD 900) (Venter et al. Reference Venter, Budar, Arnold, Budar, Venter and de Guevara2017; Venter et al. Reference Venter, Arnold and Budar2019; Venter et al. Reference Venter, Pierce and Glascock2021).

In general, the reports of early explorers in the region concure in that they consider the origin of the sculpture to be Matacanela. The descriptions of the location are consistent with both the extant remains of monumental pre-Hispanic architecture and the body of archaeological evidence derived from fieldwork directed by Venter (2018, 2019). In the same way, it is possible to establish that Matacanela was not the head of a plantation but a hamlet that formed part of the hacienda of La Victoria, most likely located near or beneath the modern town of Zapoapan de Cabañas. Remains, including the walls, of the historic building of La Hacienda de La Victoria are still visible near the shore of Lake Catemaco in the modern town of La Victoria. Therefore, the accumulated data and reports show that Matacanela is the only archaeological site with monumental architecture, sculpture, and concentrations of other archaeological materials within the mountains south of Lake Catemaco. In addition, the similarity of Monument 1 of La Victoria-Matacanela to other sculptures, such as the quadrangular base (piece 10925) on display in the Museum of Anthropology of Xalapa and those kept in the municipal palace of Catemaco, shows consistency and implies the existence of a local sculptural tradition in this portion of Los Tuxtlas.

Finally, in the summer of 2017, the archaeological salvage discussed here was carried out on the land of the La Victoria ejido, half a kilometer from the main architectural complex of the Matacanela site. Along with the excavations, we initiated a community outreach program that dialogued with local stakeholders and afforded us opportunities to participate in various activities. We wanted to learn more about community interests in—and knowledge of—local history and their perceptions of archaeology. As a result of this initial outreach, community members sought additional information regarding the pre-Hispanic occupation of their lands. In response to this positive feedback, three additional seasons of research were carried out between 2018 and 2020, expanding the study area along the eastern shore of Lake Catemaco (Budar et al. Reference Budar, Becerra, Cuevas and Bellani2021)

La Victoria-Matacanela Monument 1

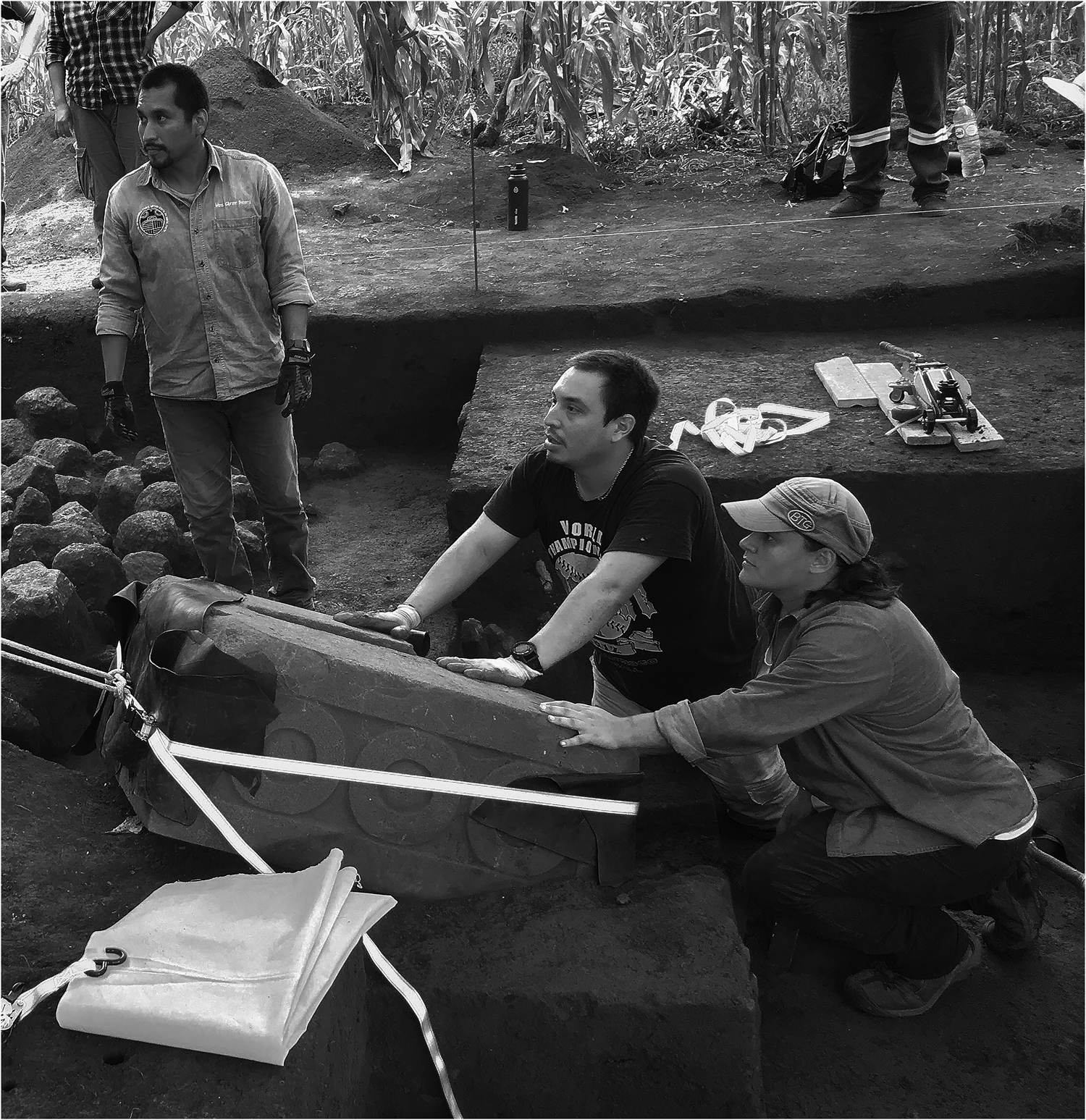

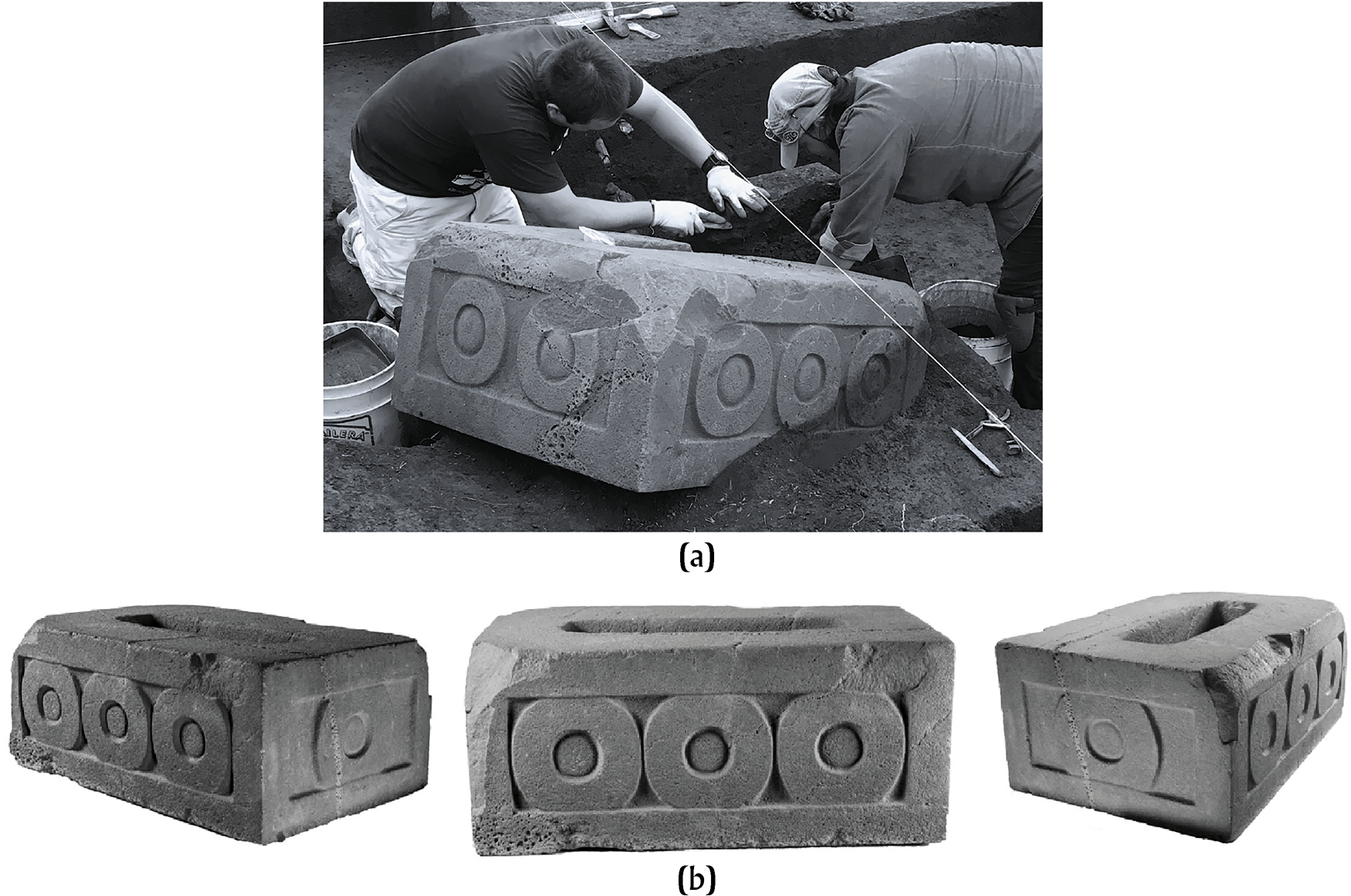

The sculpture discussed here is officially registered as La Victoria-Matacanela Monument 1 (LVM 1), given that it was the first monument in the immediate vicinity of La Victoria to have a defined archaeological context. It is a solid quadrangular block carved from vesicular basalt with relief decorations on its three intact sides; it measures 94 cm x 78 cm with a height of 43 cm (Figure 3). Each of its two longest sides displays three concentric circles, and two circles were carved on the existing end. LVM 1's upper surface contains an oblong opening (50 cm x 15 cm x 18 cm deep), and a 10 cm carved lip borders the bottom, inferior surface. This stone sculpture, fractured in one corner, is almost identical to the one moved to and currently housed in the MAX in Xalapa. The MAX sculpture was originally called a “box” or “water box” by early researchers (e.g., Blom and La Farge Reference Blom and La Farge1926:23; Seler-Sachs Reference Seler-Sachs and Lehmann1922; Stirling Reference Stirling and Willey1965:737), although more recent discussions have proposed that this and similar monuments are actually stela bases (as per Seler-Sachs's [1922:45] original comment regarding the “boxes” as possible “pedestals for figures”) (e.g., Arnold and Budar Reference Arnold, Budar, Englehardt and Carrasco2019; Budar et al. Reference Budar, Arnold and Becerra2024).

Figure 3. Image of the La Victoria-Matacanela 1 Monument in situ, and the archaeologists: Mtro. Gibránn Becerra (standing), Mtro. Mauricio Cuevas (center), and Dr. Lourdes Budar (right). (after Budar Reference Budar2018:38). Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

The lack of information regarding the context of the original Matacanela sculptures, along with their ultimate dispersal, fostered speculation regarding their cultural and chronological affiliations. Blom and La Farge (Reference Blom and La Farge1926:23) mentioned that the “boxes” were probably manufactured during the Postclassic period and associated them with the Aztec or Totonac, whereas Stirling (Reference Stirling and Willey1965:722, 737–738) suggests that the Matacanela sculptures were “quite late” in appearance, “possibly dating from Aztec or pre-Aztec times.” Although not referring to the monuments themselves, Michael Coe (Reference Coe and Willey1965:709–710) suggested that the Matacanela occupation likely dated to the Late Classic period.

Until the accidental discovery of LVM 1, and apart from these broad stylistic assessments, there were few opportunities to improve our understanding of the Matacanela sculptural corpus. For this reason, two main objectives guided our salvage efforts of the monument. The first ensured the adequate protection of LVM 1, always in accordance with Mexican federal regulations stipulating the management of archaeological heritage assets while simultaneously maintaining our commitment to collaborating with the local community. We especially sought to reduce the potential for the defacing or looting of LVM 1 and also wished to mitigate any potential destruction due to weathering or fire damage resulting from slash-and-burn cultivation. The second objective, of course, was to systematically document the sculpture's archaeological context and analyze its spatial and chronological relationships.

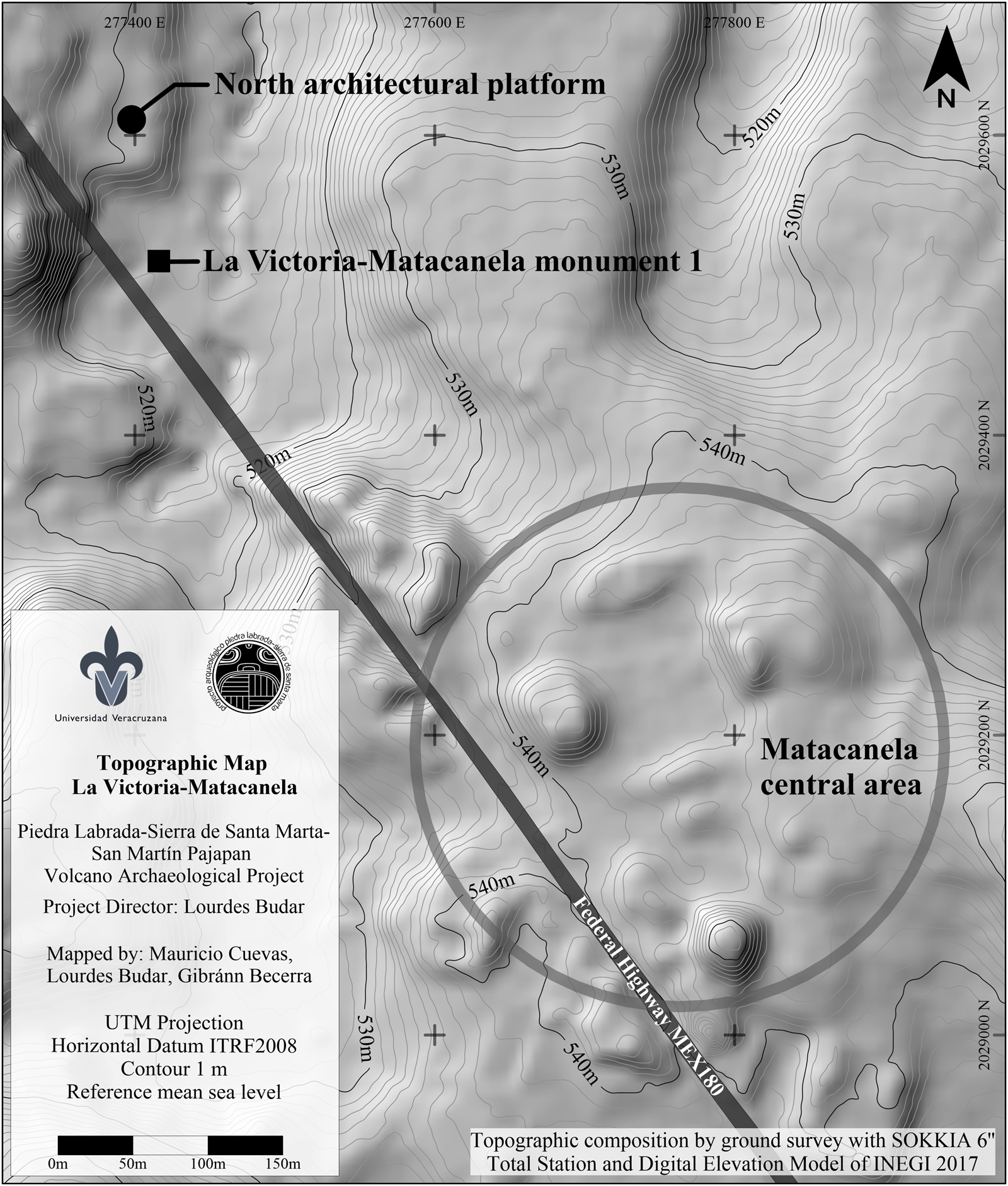

Based on these objectives we developed a strategy that included multiple phases: (a) a systematic surface survey in a radius of 500 m around the discovery site; (b) a topographical mapping program of the immediate area (Figure 4), designed to complement the survey carried out by Venter and colleagues (Reference Venter, Shields and Cuevas Ordóñez2018); (c) a program of systematic, horizontally controlled excavation that would end with the safe relocation of the monument to a secure facility; and (d) the detailed analysis of the archaeological materials recovered during the salvage work to provide information about the context of the monument and its correlation with the previously identified Matacanela sculpture.

Figure 4. Enlargement of the topographic map of La Victoria-Matacanela. The square indicates the recorded location of the monument, the small dark circle indicates the monumental architectural platform, and the large grey circle indicates the main complex of Matacanela, whose orientation differs from the building where the monument was located. Edited by the authors.

Excavating La Victoria-Matacanela Monument 1

The excavation of LVM 1 was carried out on a flat area between two hills in close proximity to Federal Highway 180. The stone sculpture was found partially exposed, although more than half of LVM 1 remained buried. No additional sculpture was found during our surface reconnaissance and mapping; however, some 50 m to the northeast of LVM 1, we identified a monumental earthen platform that formed part of an architectural complex. Additional fieldwork at this platform identified various structures, including internal rooms and a staircase, which suggested that this portion of the site may have housed an elite residence (Budar and Becerra Reference Budar and Becerra2021).

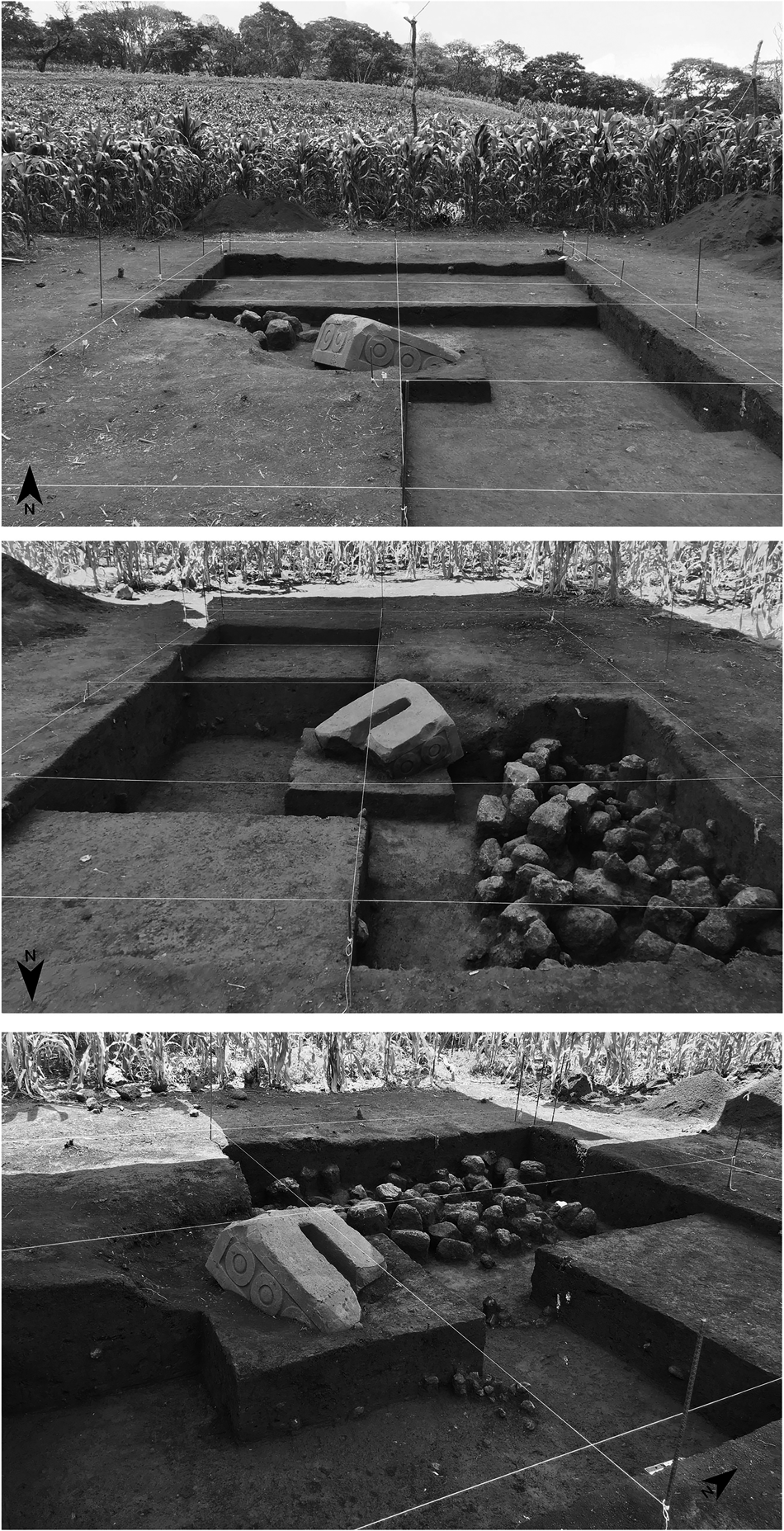

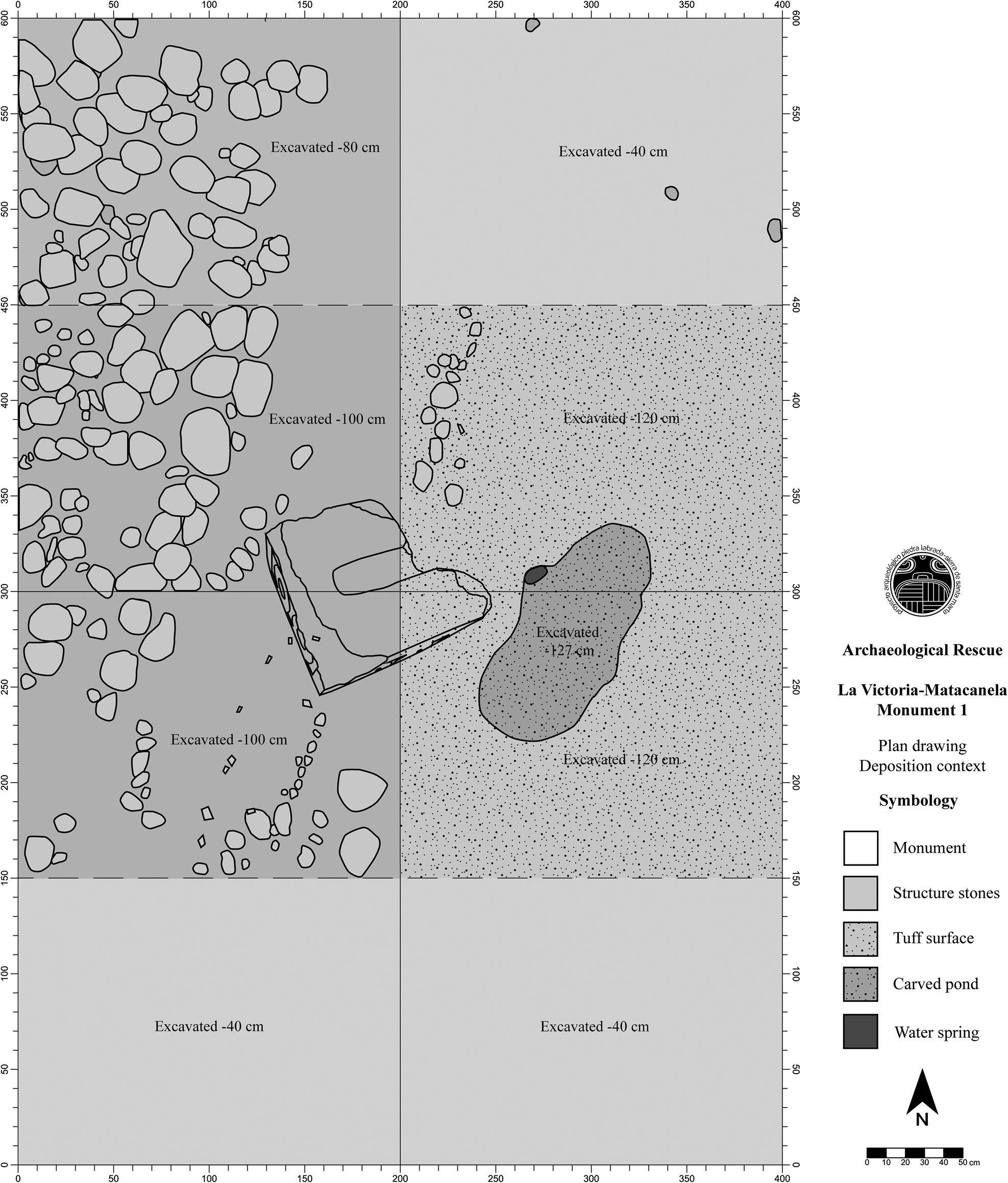

We established an excavation transect of 24 m2 (6 m x 4 m), ensuring that the sculpture remained in the center of this grid (Figure 5). Despite the salvage nature of our efforts, we sought to identify and systematically record undisturbed stratigraphic deposits that would yield information about occupational sequences, with an emphasis on collecting any carbonized material that might facilitate radiocarbon dating.

Figure 5. Salvage excavation in ejido lands of La Victoria, Catemaco, Ver. (after Budar Reference Budar2018:214). Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

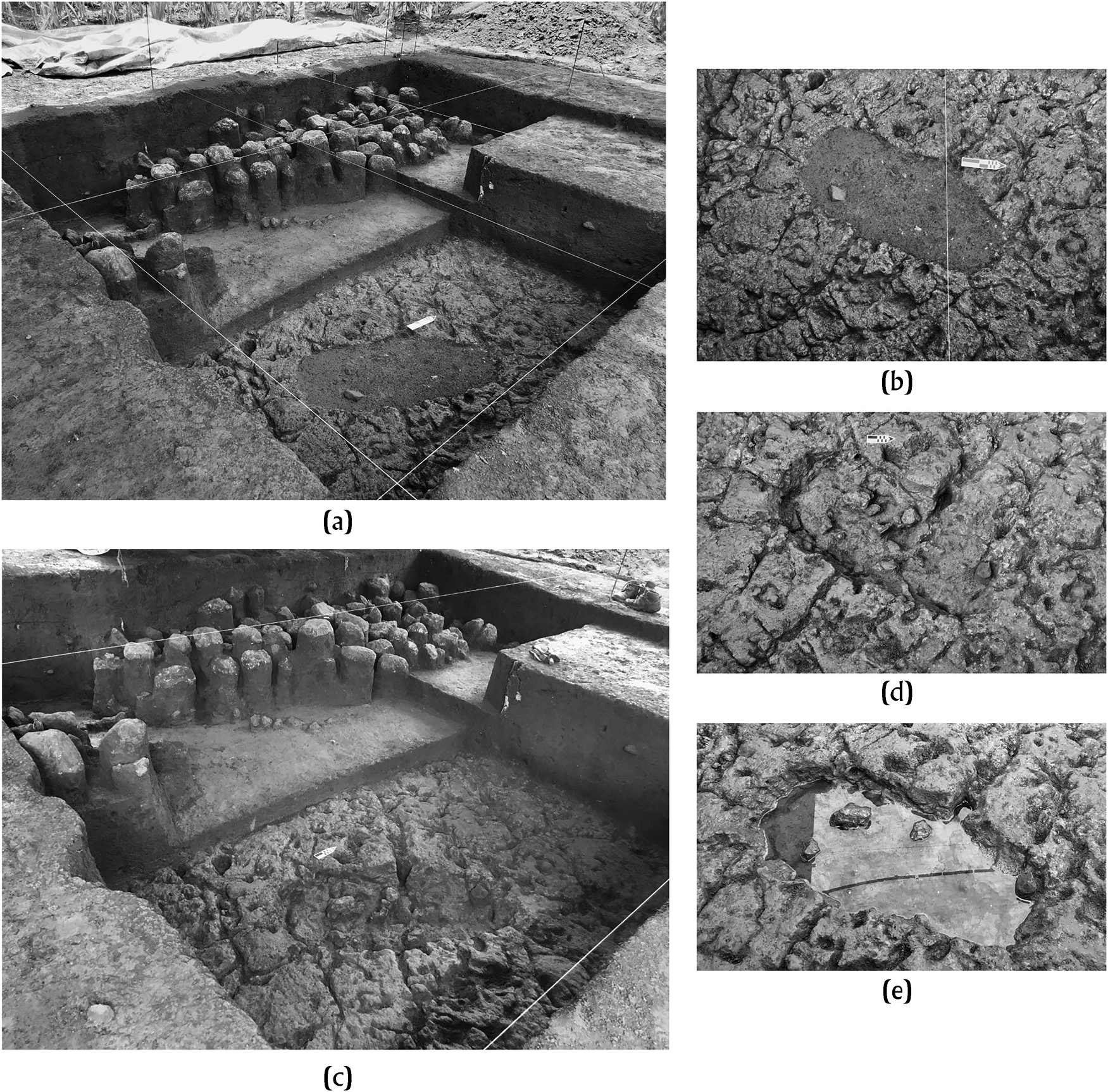

As a result of these activities, we were able to determine that LVM 1 was originally installed atop a structure at least 60 cm high, possibly a platform or shrine constructed from earthen fill, covered with a thin layer of rock and faced with basalt cobbles and slightly faceted igneous rocks. This low structure was exposed only within the spatial parameters of the established excavation transect, given that we were not authorized by the INAH Consejo de Arqueología to excavate beyond those boundaries. Consequently, we focused our excavation on revealing and cleaning the exterior of this structure, leaving the stone courses intact.

An apparent water feature (e.g., a small reservoir or pond) was located adjacent to the platform; the bottom of this feature had been carved into a lower layer of volcanic tuff, and a hole had been drilled through the tuff ultimately reaching a natural spring. Water from this spring apparently filled the excavated basin (Figure 6). On the bottom of this water feature—which remained sealed by some pebbles and the accumulated sediment until our excavation—we encountered stains of dark soil with charred organic remains, stone beads, slate sheets, obsidian blades, and a fragmented ceramic vessel. These objects showed no organized placement, nor could they be reassembled to form complete artifacts.

Figure 6. Intentionally modified surface excavated into the tuff layer (a, b, c). The resulting basin could be filled via a plugged perforation that tapped a natural spring (d, e). Source: the author. (after Budar Reference Budar2018:44). Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

We consider that the element excavated into the tuff floor was intentionally sealed at the end of the Early Classic period. The soil covering the small pond differed from the upper soils. It displays a darker shade of color (10 YR 2/2 Very Dark Brown), a higher concentration of materials, a more granular texture, and less compaction compared to both the clay-rich soils of the upper strata and the binder soil of the platform. In addition, the interior of the pond was obstructed with pebbles, and the main spring was covered by a stone that, when removed during excavation, caused water to gush out again and flood the pond. The integration of water sources or springs into pre-Hispanic architecture and sculpture is not uncommon in this type of context. In the coastal zone of Los Tuxtlas, some formal architectural complexes were built that integrated springs into the main plazas. On a broader scale, sites south of Los Tuxtlas, such as Estero Rabon, as well as Gulf Coast sites to the north, such as Cuajilotes or Yohualichan, provide examples of the architectural use of springs and canal systems in plazas containing sculpture.

An Accelerator Mass Spectrometry date from recovered carbon (1690 +/- 30 BP; Beta–524633; charred material; δ13C: -26.1%, 2-sigma) produced two calibrated ranges: a.d. 318–416 (79.1%) and a.d. 256–299 (16.3%), placing these materials within the Early Classic period of the regional chronology (e.g., Santley Reference Santley2007). No additional archaeological materials were recovered below this tuff layer, so it appears that the reservoir was excavated—or was at least already in use—during the Early Classic period.

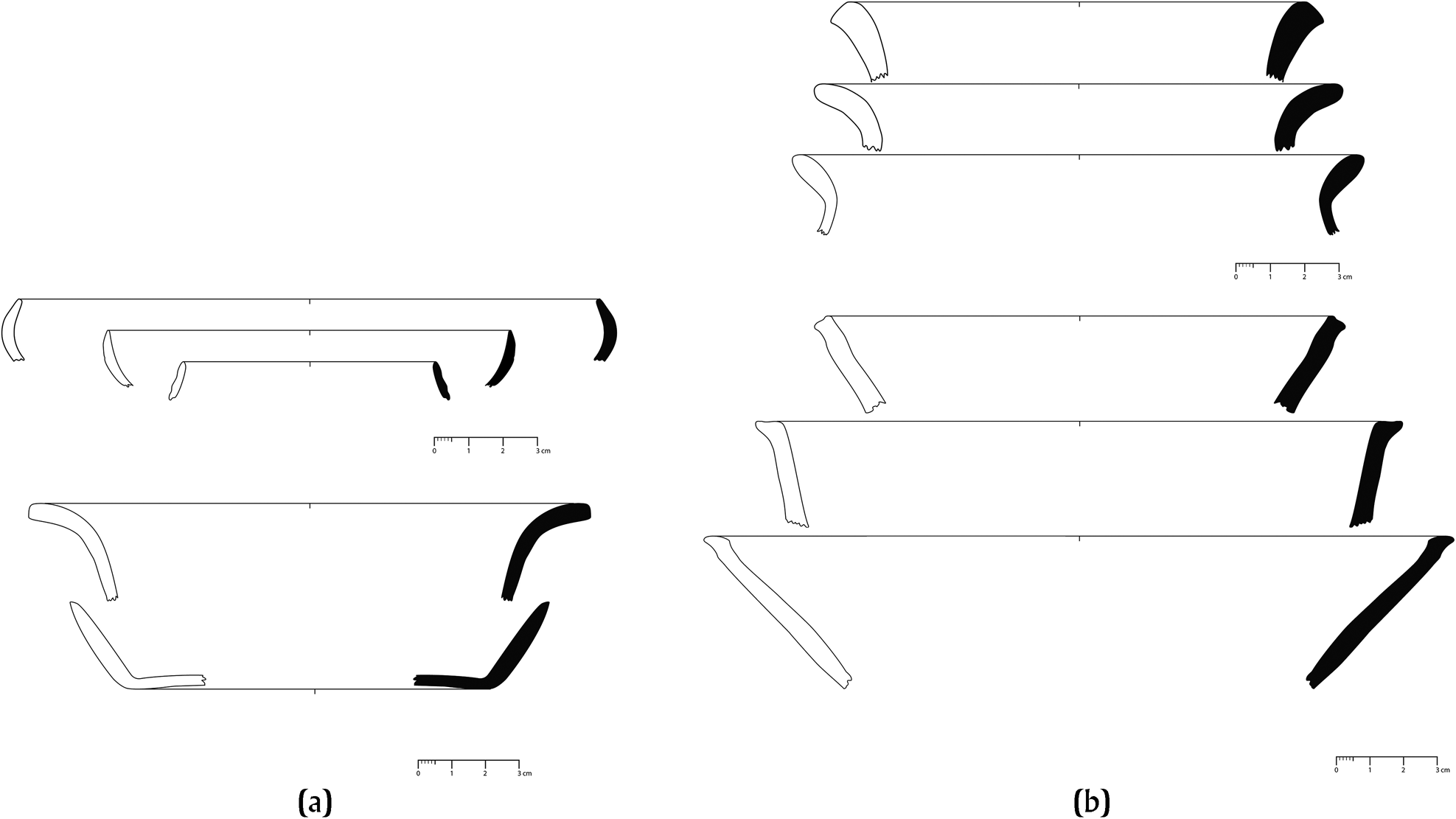

As noted above, we recovered a variety of artifacts from the stratum that directly overlaid the tuff concretion. Ceramics included untempered orange and gray pastes, which are common in the Tuxtlas region and strongly associate with the Early and Middle Classic periods (a.d. 300–600) (e.g., Ortiz and Santley Reference Ortiz C. and Santley2021; Santley Reference Santley2007). The most common vessel forms were cajetes (bowls) with curved, inward-leaning walls with a straight rim; cajetes with straight, outward-leaning walls and a straight rim; and cajetes with straight walls and an everted rim (Figure 7a). We also recovered brown and reddish coarse-paste ceramics in the form of cajetes, with straight, outward-leaning walls with a straight rim and olla (jar) rims with an everted rim (Figure 7b). These coarse-paste ceramics are notable for their volcanic ash and quartz/shell sand temper, a strong indicator of their local origin (e.g., Pool Reference Pool1990; Santley Reference Santley2007; Santley et al. Reference Santley, Arnold and Pool1989). Unfortunately, such utilitarian wares are ubiquitous in the region throughout much of the pre-Hispanic era and are rarely temporally diagnostic. We also recovered a few fragments of very deteriorated anthropomorphic figurines.

Figure 7. Ceramic forms recovered from the salvage excavation: (a) (left) fine pastes; (b) (right) coarse pastes. Scale in cm. Edited by the authors.

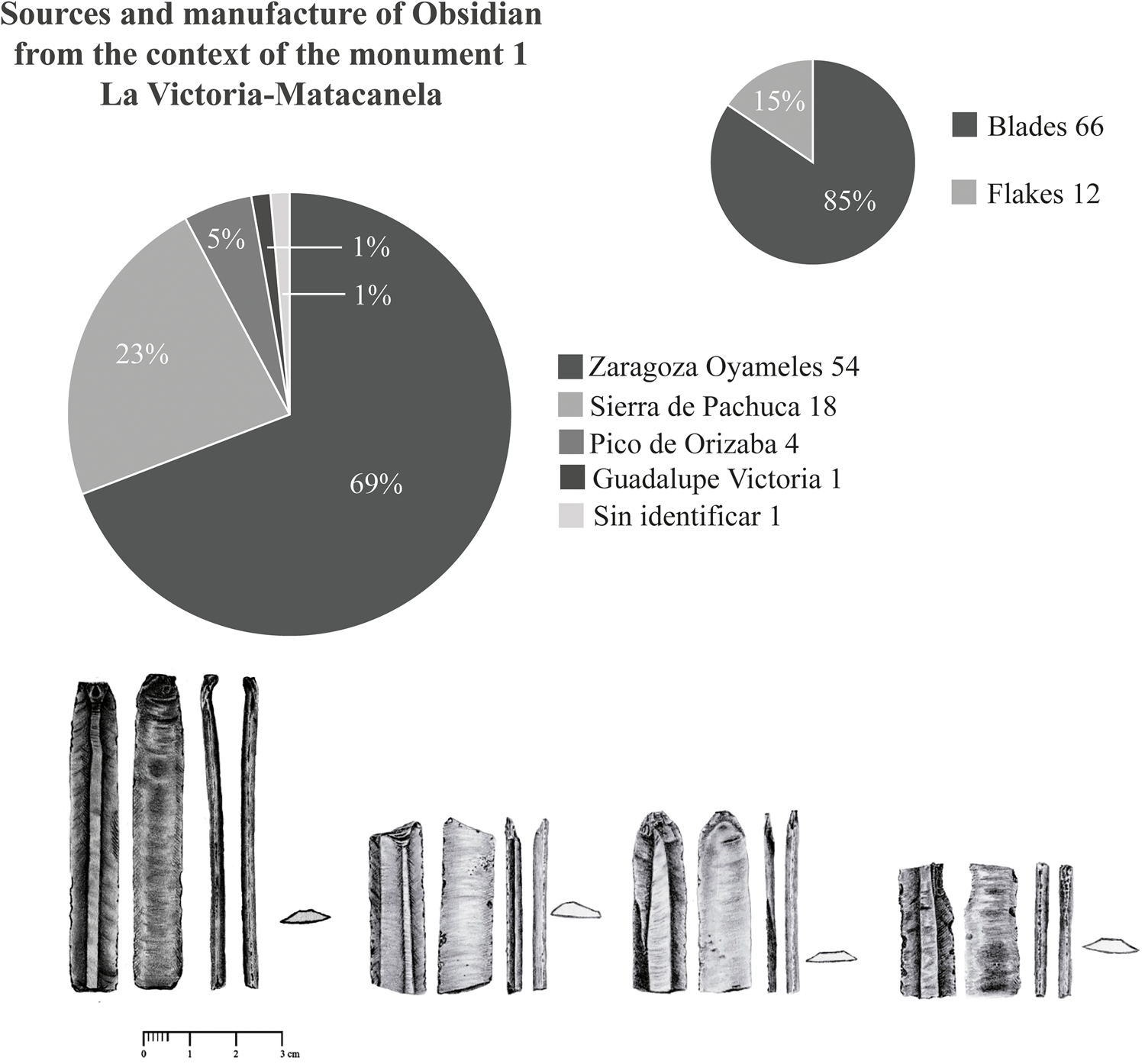

Obsidian recovered from the soil above the tuff floor also shows a connection with Early Classic exchange patterns in Los Tuxtlas. The recovered lithics included 78 obsidian fragments that were examined macroscopically to identify sources and determine artifact types (Figure 8, above). Despite its volcanic origins, the Tuxtlas contain no obsidian deposits, so all recovered volcanic glass is imported. The majority of the excavated assemblage derives from Zaragoza-Oyameles, although fragments from Sierra de Pachuca and, in smaller quantities, from Pico de Orizaba and Guadalupe Victoria are also present (e.g., Cobean Reference Cobean2002). The best condition and relatively high percentage of obsidian artifacts attributable to the Sierra de Pachuca source is noteworthy, in that sites within the Tuxtlas rarely exhibit double-digit percentages for lithics from this particular obsidian source (Barrett Reference Barrett2003; Santley Reference Santley2007). Although the exploitation and distribution of green obsidian from Pachuca was controlled by Teotihuacan during the Classic period, it is difficult to argue for either a direct connection or direct influence, considering the percentage of this material in the context. On the contrary, the presence of green obsidian blades is consistent with the regional pattern recognized in other sites such as Teotepec, Piedra Labrada, and even Matacapan (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, VanDerwarker, Wilson, Budar and Arnold2016). This points to regional redistribution mediated by some of the entities more closely linked to Teotihuacan networks in southern Veracruz, such as Matacapan or El Garro (Stoner and Marino Reference Stoner, Marino, Hirth, Carballo and Arroyo2020).

Figure 8. Obsidian lithics recovered during the archaeological salvage: (right) lithic artifact types and obsidian sources; (left) obsidian prismatic blades. (after Budar Reference Budar2018:116). Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

Prismatic blades make up 85 percent of this obsidian collection (Figure 8, below). Given that we recovered minimal evidence for obsidian reduction, it is likely that much of this material arrived on site in the form of premanufactured blades, a pattern noted by researchers at nearby Tuxtlas sites (e.g., Santley Reference Santley2007; Wilson and Arnold Reference Wilson, Arnold, Budar, Venter and de Guevara2017; Wilson and Glascock Reference Wilson and Glascock2020). The obsidian appears to have been discarded in the immediate vicinity of the low platform and ultimately washed into the reservoir after it was abandoned and eventually silted up

Based on the available evidence, we propose that the reservoir, spring, and the associated platform formed an architectural complex where LVM 1 was displayed. Although there is evidence of much earlier occupation at other portions of Matacanela (e.g., Venter et al. Reference Venter, Budar, Arnold, Budar, Venter and de Guevara2017), this locale appears to have been active during the Early Classic period and likely fell into disuse by the end of the Middle Classic period.

We suggest that LVM 1 was originally installed atop the low platform. The monument's final position, resting partially within the reservoir, likely resulted from an intentional displacement during the Middle Classic period. The fractured condition of LVM 1 may have either precipitated or resulted from this later abandonment.

We base this assessment on several lines of evidence that complement our archaeological data. First, during the region's Early Classic period, stela both with and without bases were installed atop shrines or low platforms (e.g., Arnold and Budar Reference Arnold, Budar, Englehardt and Carrasco2019). For example, along the coastal area of the Sierra Santa Marta, undecorated stela bases have been documented within monumental architectural spaces, as is the case with Stela 1 at Piedra Labrada (e.g., Zepeda et al. Reference Zepeda, Budar and de Guevara2010). The context around this in situ base was excavated in the 1970s by Marco Antonio Reyes López (Reference Reyes López1997), whose work revealed that this monument was located on the top of a structure that measured at least 9 m per side. The base was part of a larger sculptural complex that included not only Piedra Labrada Stela 1 but also a zoomorphic throne (jaguar), carved basalt columns, braziers, stone containers, and an offering of fine-paste ceramic vessels in shades of orange, yellow, and gray. As in the context of LVM 1, the sculptural complex of Piedra Labrada Stela 1 dates to the Early/Middle Classic period (a.d. 300–650) and is distinguished by the use of Teotihuacan-related iconography (e.g., Coe Reference Coe and Willey1965:704; Taube Reference Taube2001; von Winning Reference von Winning1961).

Interestingly, both the Matacanela and Piedra Labrada examples include the representation of concentric circles depicting beads or chalchihuis, which have been identified by López Corral (Reference López Corral2021) as Teotihuacan iconographic numerals that were used to calculate time. Also noteworthy is the similarity of LVM 1 to the bases of the stela markers in the ballgame scene identified by Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda (Reference Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda1963) and depicted in the Tepantitla murals at Teotihuacan.

The association of sculpture, architecture, and water features was also common in the Classic-period Tuxtlas. In fact, integrating aquatic references and mountainous landscapes was a constant practice in the region's pre-Hispanic architecture; sites such as Teotepec (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, VanDerwarker, Wilson, Budar and Arnold2016), Agaltepec (Arnold and Venter Reference Arnold and Venter2004), and Totocapan (Stoner and Pool Reference Stoner and Pool2015) incorporated such elements into their architectural plans (also see Stark Reference Stark, Grove and Joyce1999a). In the coastal area of the Sierra de Santa Marta, along the east Gulf coast of the Tuxtlas, at least seven groupings of monumental architecture integrate water features into their architectural configuration (Budar et al. Reference Budar and Becerra2021). In some instances, the space was designed in such a way that water emerged from the corner of a mound and flowed toward the center of the plaza, whereas in others, the output from a nearby spring was channeled to flow across the plaza. Water tanks or cisterns were often built adjacent to the site's main platform and would have remained full during the rainy season.

The incorporation of water features into architectural layouts was also common during the Classic period farther north along the Gulf Coast; sites such as Cuajilotes or Yohualichan (Ruiz Gordillo Reference Ruiz Gordillo, Budar and de Guevara2020) exhibit construction programs that included springs and watercourses as part of their architectural design. In central Veracruz, this aspect was realized in a monumental way. For example, in Cerro de Las Mesas, the central water repository was integrated into formal architectural complexes. In 1943, in one of the adjacent plazas, Stirling located the majority of the stelae and sculptures characteristic of this site (Stark Reference Stark1999b, Reference Stark2022; Stirling Reference Stirling1943). The cisterns of La Joya (Daneels Reference Daneels, Budar and de Guevara2020), located in the Rio Jamapa basin, and those of Tlalixcoyan (Stoner et al. Reference Stoner, Stark, VanDerwarker and Urquhart2021) are other examples of such combinations.

The destruction of monuments and the abandonment or restructuring of architectural space is not an anomaly within the pre-Hispanic Tuxtlas. At the same Matacanela site, Venter (Venter et al. Reference Venter, Budar, Arnold, Budar, Venter and de Guevara2017; Venter et al. Reference Venter, Arnold and Budar2019) documented a purposefully destroyed effigy stela associated with elements of ballgame paraphernalia that dates to the Late Classic period. In the western region of the Tuxtlas, this period was characterized by declines in agriculture, abandonment of centers, the emergence of low-population-density settlements, and the reconfiguration of political authority (e.g., Byrne and Horn Reference Byrne and Horn1989; Santley and Arnold Reference Santley and Arnold1996; Venter et al. Reference Venter, Arnold and Budar2019).

Given the above, it is not difficult to suppose that LVM 1 was installed on a platform and located adjacent to a water feature fed by a spring accessed via a perforation in the carved tuff floor (Figure 9). At the same time, this grouping was part of a broader architectural pattern that comprised terraced hills, structures on platforms and—slightly farther away on the main Matacanela site—formal plaza groups and monumental architecture.

Figure 9. Plan drawing of the context of monument 1 of La Victoria-Matacanela. The drawing depicts the monument's position relative to the spring, as the monument was displaced approximately 80 cm. (after Budar Reference Budar2018:48). Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

The extraction and relocation of La Victoria-Matacanela Monument 1

La Victoria-Matacanela Monument 1 (LVM 1) remained in situ until sufficient space was cleared to allow its safe extraction without affecting the stratigraphic record of the base and its immediate surroundings. After extensive discussions between the legal representatives of INAH Centro Veracruz and the La Victoria community assembly, it was decided to house LVM 1 in the Daniel White Fonseca ejido building of La Victoria. This location afforded the requisite security and adequate protection required by INAH regulations; not only was the space completely fenced and secure but both ejido authorities and community residents would be able to view the monument. In addition, the parties agreed to construct a base for LVM 1 and ultimately exhibit it in a covered corridor to mitigate potential erosion brought about by wind, rain, and exposure to the sun.

These outcomes were achieved thanks to the interest and cooperative efforts of the La Victoria community members. Initial consideration was given to housing the monument in one of the nearby regional museums, such as the Regional Museum of San Andrés Tuxtla or the Tuxteco Museum in Santiago Tuxtla. However, local stakeholders felt that it would be an affront to relocate the monument beyond their ejido territory. This situation became increasingly complicated as federal regulations involving the disposition of Mexican archaeological patrimony came into direct conflict with the community's desire to preserve and protect the archaeological heritage of their own local territory. Similar tensions arising from stakeholder interests are not uncommon in the history of archaeological research in southern Veracruz (e.g., Grove Reference Grove2014).

Nonetheless, open dialogue and the opportunity for collective participation in the salvage effort allowed for a collaborative agreement between the community, the archeological team, and the authorities of INAH Centro Veracruz. In this way, members of the ejido oversaw and participated in the monument's recovery alongside the Universidad Veracruzana archaeologists. Local community involvement was enthusiastic, and soon LVM 1 was transformed from a simple pre-Hispanic sculpture into an integrative icon of collective action and pride that united the ejidatarios and their families, local school groups, community authorities, and neighboring townsfolk who came to witness the salvage operations (Budar and Becerra Reference Budar and Becerra2021).

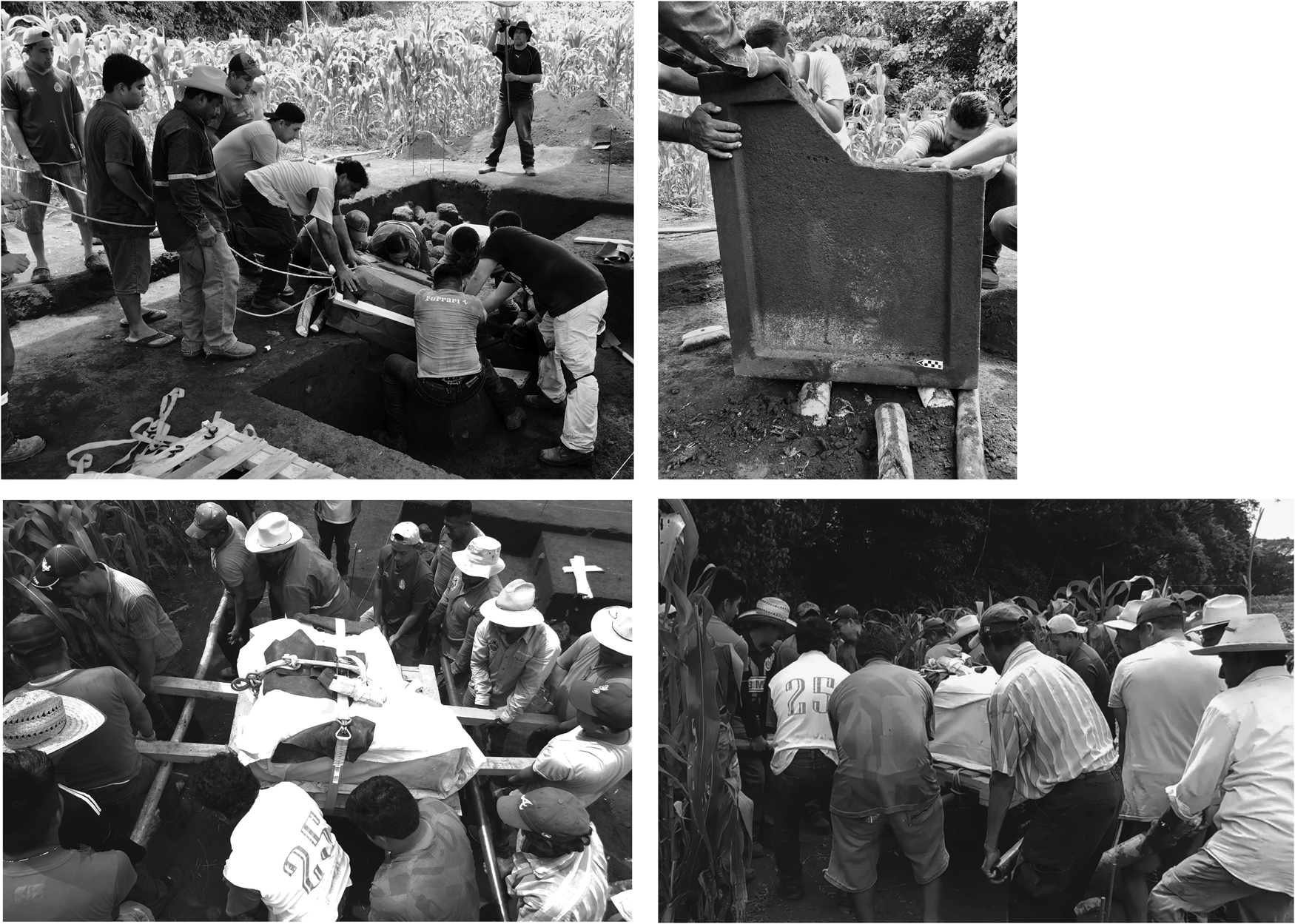

After LVM 1's context and associated archaeological materials were thoroughly documented, the monument was transported from the excavation site to the ejido hall of La Victoria. The base was carefully cleaned and then wrapped with cotton fabric and synthetic rubber while ratchet straps and cotton ropes were used to set the monument upon a wooden pallet that was reinforced with solid crossbars and galvanized steel supports.

The transfer of the monument from the excavation site to the transport vehicle was conducted solely using human labor and involved an uphill journey of approximately 100 m. Not surprisingly, several stops along the way were needed to allow the volunteer porters to rest and catch their breath. Once they arrived at the main road, the monument was loaded onto a truck and transported to the La Victoria community with an accompanying escort consisting of local authorities and community members (Figure 10). The collaboration of the ejido authorities and the community of La Victoria during this stage of the monument transfer was crucial to the project's success; without local support and cooperation the extraction of the monument would not have been feasible.

Figure 10. Transfer of Monument 1 of La Victoria-Matacanela with the help of the ejido members. (after Budar Reference Budar2018:229). Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

Conclusion: Revisiting the La Victoria-Matacanela sculptural complex

As mentioned above, most of the existing Matacanela sculptural corpus was initially documented in 1907 by the Selers. The circumstances in which these pieces were originally found are unknown, and it is not known whether they were encountered fully exposed or buried. However, the correspondence that Eduard Seler (Sepúlveda y Herrera Reference Sepúlveda y Herrera1992) sent from Finca La Constancia in the month of February 1907 would imply that the couple was in the Tuxtlas for only a few short weeks. Consequently, it is likely that the sculptures were already exposed and located near one another. Unfortunately, this lack of information limits our ability to know with certainty the exact conditions under which the Matacanela sculptures were first discovered.

Although Blom and La Farge in 1926 and Valenzuela and Ruppert in 1937 provided additional documentation regarding the sculptural assemblage, they did not provide additional information about possible associations with archaeological and/or architectural features. Their speculations about temporal and cultural affiliations were based on analogies and stylistic affinities with pre-Hispanic objects found outside the Tuxtlas and only served to delay further understanding. For example, the identification of the solid, rectangular sculptures as Postclassic “boxes” limited the possibility of recognizing these monuments as elements of a larger sculptural discourse that was integrated into the constructed landscape of Matacanela. Stelae anchored in decorated bases were less commonly known than stelae embedded directly into architectural platforms or with smooth bases, a fact that may have led Blom—who was already familiar with Mayan stelae—to exclude the Matacanela “boxes” from consideration as part of a stelae/base paring (e.g., Arnold and Budar Reference Arnold, Budar, Englehardt and Carrasco2019; Budar et al. Reference Budar, Arnold and Becerra2024). The earlier Matacanela stelae themselves were possibly destroyed or repurposed, as we now know occurred with the Late Classic effigy stela at Matacanela (Venter et al. Reference Venter, Budar, Arnold, Budar, Venter and de Guevara2017; Venter et al. Reference Venter, Arnold and Budar2019).

Prior to the discovery of LVM 1 in 2017, Budar (Reference Budar2015) posited that the monuments reported by early explorers were not originally located in the central plaza of Matacanela. The review of the display contexts of the sculptural elements of bases and stelae in the region allowed her to conclude that this type of sculpture was recurrently integrated into, and installed within, open plazas and courtyards of late Formative and Early Classic sites such as Tres Zapotes, Piedra Labrada, and Cerro de las Mesas. This association is distinct from other architectural patterns such as ballcourt or quadripartite plaza arrangements of the Middle and Late Classic periods. Considering these data and the fact that the Matacanela central complex comprises a plaza arrangement quite similar to what Daneels (Reference Daneels, Arnold and Pool2008) has named The Standard Plan, including a ballcourt (Venter et al. Reference Venter, Shields and Cuevas Ordóñez2018), Budar (Reference Budar2015) proposed that the sculptures were originally installed around the perimeter of the site, most likely in areas now obliterated by contemporary human activity. The archaeological documentation of LVM 1 reinforces this argument, given that it was placed within an architectural group located on the outskirts of the central architectural complex of the site.

The sculpted emblems on LVM 1 also provide potential information regarding the monuments’ original use context. Not only is LVM 1 almost identical in form to one of the bases registered by the Selers in 1907, but the carved circles are also quite similar in their morphological aspects of size, relief, and manufacture (Figure 11). Both quadrangular monuments exhibit three concentric circles on each of their respective sides; the main difference is that the monument recorded by the Selers displays a single element on each end, whereas LVM 1 contains two such elements on its existing end. Given López Corral's (Reference López Corral2021) identification of these chachihuis as numerical representations, it would seem that these two stela bases could well be read as a set—that is, a series with a numerical sequence.

Figure 11. A comparison between the two monuments: (a) La Victoria-Matacanela Monument 1 in situ, with representation of chalchihuis forming the numerical combination 3-2; (b) Matacanela quadrangular base registered in 1907 by Seler-Sachs (Reference Seler-Sachs and Lehmann1922), with representations of chalchihuis forming the numerical combination 3-1. Now in the Xalapa Museum of Anthropology. (after Budar Reference Budar2018:36). Of. INAH: 401.1S.3-2018/2228.

The archaeological information recovered by our salvage project strongly suggests that the sculptures recorded by the Selers date to the Early and Middle Classic periods. We cannot, however, presume that those monuments were located in close proximity to LVM 1, nor can we speculate as to the function of these additional pieces. It is quite possible, however, that LVM 1 played an important role in the visual discourse and architectural program of Matacanela during the Early/Middle Classic period.

Finally, the salvage of LVM 1 offers a valuable lesson regarding the importance of a community's right to manage its own historical interests (Budar and Becerra Reference Budar and Becerra2021). The participation of stakeholders and their advocacy for their own local heritage was crucial to the ultimate success of this project. Those interactions demonstrate that contemporary archaeology, both in Mesoamerica and elsewhere, is not simply about discovering the past; rather, it involves cooperation and dialogue, the collective construction of memory, and consideration of the past while we work together to envision a shared future.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude goes to the men and women of Ejido de La Victoria, Catemaco, Veracruz, for their consent to allow us to carry out archaeological research in their territory. In particular, we thank Gilberto Barrios†, Macario Cortés, Delia Zacarias, Bitilio Fonseca, Evaristo Rodríguez, Gloria Hernández; and we give very special recognition to Don Silvio Arguelles Xolo and his family. We thank the INAH Consejo de Arqueología and INAH Centro Veracruz, especially archaeologist Carmen Rodríguez. We also gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Mtro. Sergio Vázquez of the Universidad Veracruzana; Dr. Marcie L. Venter from Murray State University; Mtro. Gibránn Becerra and Dr. Nathan Wilson of the Universidad Veracruzana; and Dr. Philip J. Arnold, III of the Loyola University of Chicago. Thank you to the archaeologists who participated in this fieldwork: Gibránn Becerra, Mauricio Cuevas, Viridiana Madrid, Polo Segura, Rosa Velasquez, Antonio Lozano and Mariana Vargas. To our beloved Marimar Becerra Álvarez, forever young and smiling, who is always in our memories and our hearts.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Data availability statement

All data are available in the final project report on file with the Archivo Técnico de la Coordinación Nacional de Arqueología del INAH. https://arqueologia.inah.gob.mx/publico/especifico.php?id=MTU5

Funding statement

Funding for this project was provided by the Universidad Veracruzana by way of a collaborative agreement with the Administración Portuaria Integral de Veracruz (APIVER): API-GI-CS-62905-008-17.