Introduction

At the present day, elected officials, civil servants and other actors that are part of the machinery of national governments operate in a multilevel governance setting. They constantly interact with public and private actors from other levels of governance to ensure the political steering of complex societies and to deal with policy problems that cannot be solved through policy making on a single level (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003).

Several scholars have associated the age of multilevel governance with a gradual relocation of competences away from national governments (Ansell & Torfing, Reference Ansell and Torfing2016; Kohler‐Koch & Rittberger, Reference Kohler‐Koch and Rittberger2006). Parts of sovereignty have shifted upwards to the supranational level (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2019), downwards to sub‐national jurisdictions (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Chapman‐Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair‐Rosenfield2016) and sideways to independent regulators and private actors (Gilardi, Reference Gilardi2008). These processes have been interpreted as resulting in a loss of centrality for national governments (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003; Rhodes, Reference Rhodes1996; Slaughter, Reference Slaughter2004) and in the fragmentation of political authority (Abbott & Snidal, Reference Abbott, Snidal, Mattli and Woods2009; Enderlein et al., Reference Enderlein, Walti and Zürn2010; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2001; Jurado & Leon, Reference Jurado and León2021; Piattoni, Reference Piattoni2010; Zürn, Reference Zürn2000, Reference Zürn2003) – creating a situation commonly referred to as ‘denationalization’.

At the same time, however, it has been noted that national governments strive to reassert their political authority in multilevel polities (e.g., Goetz, Reference Goetz2008; Mayntz, Reference Mayntz and Benz2004, Reference Mayntz and Schuppert2005, pp. 271–272) by reclaiming control over fragmented policy fields (Christensen & Laegreid, Reference Christensen and Laegreid2007; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Lie, Lægreid, Christensen and Lægreid2007; Dahlström et al., Reference Dahlström, Guy Peters and Pierre2011). This process of recentring at the level of the central government is epitomised by reforms integrating public policies and coordinating or even merging public sector organisations across different policy sectors (6, Reference Perri2004; Peters, Reference Peters2015; Tosun & Lang, Reference Tosun and Lang2017).

In this article, we argue that these two apparently divergent phenomena are related. Above all, we aim at showing how denationalization in multilevel governance ultimately elicits the recentring of political authority at the national level. More specifically, we examine two dimensions: first, how the delegation of competencies to independent regulatory agencies, international organisations and sub‐national governments is ultimately associated with the passing of reforms that recentre the nation state through policy integration and administrative coordination. Second, we focus on how the capacity to act of these actors also shapes these recentring dynamics. Our analysis contributes to the literature in three ways. (1) From a theoretical perspective, we reconcile claims about denationalization with arguments on recentring under a unified framework grounded on the endogenous dynamics of multilevel governance. (2) Empirically, we provide the first study that analyses systematically the relationship between denationalization and recentring. (3) Regarding practical aspects, our analysis contributes to the discussion about the problem‐solving capacity of multilevel governance in an era when policy makers face societal demands to tackle emerging, super complex problems, such as the climate emergency and the global health crisis related to COVID‐19 (e.g., Ansell et al., Reference Ansell, Sørensen and Torfing2021). It is important to point out that, in our paper, ‘recentring’ is about internal coordination, that is, more central control over fragmented policy fields for the existing competences of central state, not about an additional centralisation of competencies.

To achieve these goals, we rely on different strands of literature in political research as starting points. First, we build on theories of multilevel governance to conceptualise the possible consequences of delegating political authority to task‐specific and general‐purpose jurisdictions (e.g., Bache et al., Reference Bache, Bartle, Flinders, Ansell and Torfing2016; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003; Reference Hooghe and Marks2015; Kübler, Reference Kübler, Braun and Maggetti2015). These consequences include, for instance, changes to party competition at the domestic level (e.g., Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009) and to accountability relationships (e.g., Papadopoulos, Reference Papadopoulos2007). Second, we rely on research on policy capacity to put forward expectations about how the competences attributed to the actors under investigation play out with respect to shifts in political authority (e.g., Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ramesh and Howlett2015). Third, we use insights from research on policy integration (PI) and administrative coordination (AC) to conceptualise the nature and scale of this phenomenon (6, Reference Perri2004; Christensen & Laegreid, Reference Christensen and Laegreid2007; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Lie, Lægreid, Christensen and Lægreid2007; Dahlström et al., Reference Dahlström, Guy Peters and Pierre2011; Jordan & Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010; Tosun & Lang, Reference Tosun and Lang2017). By combining these streams of literature, we derive expectations on how the delegation of competences to task‐specific and general‐purpose jurisdictions, as well as their capacity to act, impacts on recentring dynamics in nation states. In short, we argue that denationalization elicits processes that strengthen the reach of the central government over sectoral policies and public administrations. These dynamics are second‐order effects that are largely unintended, that is, unanticipated, by the architects of delegation; they are rather triggered by the problems generated by denationalization and at the same time shaped by new opportunities provided to actors in favour of recentring reforms, especially at the level of the central government.

To investigate our expectations empirically, we use an original dataset based on information about event data related to recentring, that is, PI and AC reforms. The data cover four diverse policy fields across 13 countries from 1985 to 2014. This multilevel data structure (policy fields nested in countries) allows us to investigate in a detailed manner whether and how denationalization results in the recentring of political authority through multilevel time‐series regression. We include a battery of control variables to account for alternative explanations, including the partisan composition of governments and problem pressure. In that regard, it is important to remark that we do not aim at reconstructing all the possible causes of recentring; rather, in line with an effect‐of‐cause approach, we want to systematically identify the net effect of different dimensions of denationalization on recentring.

Our empirical analysis indicates that especially the delegation of competences to task‐specific jurisdictions at the national level (sideways delegation) and at the European Union (EU) level (double delegation) positively affect the extent to which governments pass reforms that recentre political authority. Our analysis also suggests that such reforms become even more likely the greater the capacity to act attributed to these actors. Contrariwise, neither the delegation of competences to task‐specific non‐EU international jurisdictions, nor the attribution of capacity to act on them result in such reforms at the national level. Delegation to lower levels of governance makes such reforms even less likely.

How does denationalization affect the recentring of political authority?

In this article, we claim that denationalization can ultimately trigger the recentring of political authority. By denationalization, we refer to the process by which competences are delegated away from the central government to sub‐national governments, international organisations and independent agencies, as well as to the extent to which an actual capacity to act is attributed to these actors. We stress that this rebalancing is unintended, in sense that it is neither a purposive ex ante strategy nor a direct functional consequence of denationalization. Rather, the probability of recentring is expected to increase ex post, because denationalization – which follows its own dynamics – once in place, both creates new problems and provides new opportunities to actors in favour of recentring political authority at the level of the central government.

To conceptualise our dependent variable – reforms involving the recentring of political authority – we build on research on PI and AC. A burgeoning literature in public policy emphasises that governments increasingly pursue reforms that transcend specialised policy communities and whose goals and instruments span across policy sectors (Adelle & Russel, Reference Adelle and Russel2013; Candel & Biesbroek, Reference Candel and Biesbroek2016, pp. 211–231; Jochim & May, Reference Jochim and May2010; Jordan & Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010; Vandenbroucke et al., Reference Vandenbroucke, Hemerijck and Palier2011). In addition, public administration research has pointed for some time to the growing importance of reforms that change the relationship between sector‐specific organisations with the goal to improve their coordination (Bouckaert et al., Reference Bouckaert, Peters and Verhoest2010, pp. 36–40; Christensen & Lægreid, Reference Christensen and Laegreid2007, pp. 1059–1060), such as establishing specific coordinating agencies or transversal administrative units (6, Reference Perri2004, pp. 10, 108; 6 et al., Reference Perri, Leat, Setzler and Stoker2002; Bouckaert et al., Reference Bouckaert, Peters and Verhoest2010, pp. 29–346).

Our overarching argument is that denationalization – the delegation of competences away from the national government – creates momentum for recentring processes towards the national level through a rebalancing movement. These dynamics entail new coordination demands and provide new opportunities to actors to strengthen the centre through PI and AC reforms. For example, there is ample scholarship on how New Public Management reforms aiming at making public administration more efficient through delegation and performance management have generated new, unforeseen problems for interorganisational coordination such as silos mentalities, distrust and policy incoherence. These dynamics have ultimately created new demands to reassert the centre to regain control over policy making, countervail bureaucratic rivalries and ensure policy capacity (e.g., Christensen & Laegreid, Reference Christensen and Laegreid2007).

It is generally considered that denationalization consists of three processes pointing in different directions: upwards to international and supranational organisations (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2019), downwards to sub‐national entities (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Chapman‐Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair‐Rosenfield2016) and sideways to independent regulators (Gilardi, Reference Gilardi2008). Accordingly, national governments attribute (more) competences to both general‐purpose jurisdictions and task‐specific jurisdictions. Denationalization towards general‐purpose jurisdictions implies a loss of government's steering capacity, while denationalization towards task‐specific jurisdictions is more related to the sectoral fragmentation of political authority (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003, p. 236; see also Kübler, Reference Kübler, Braun and Maggetti2015). In the following, we will explain why both types of jurisdictions are likely to elicit recentring but for different reasons.

Our analysis unpacks denationalization into two dimensions: (1) the delegation of authority, and (2) the capacity to act attributed to the delegated body. The former can be conceived as a measure of the scope of delegation, that is, the extent of tasks and competencies that governments have delegated to international organisations, sub‐national entities and national and European agencies (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2015). The latter refers to the actual ability of the delegated bodies to make decisions in a relatively autonomous way (see for instance Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ramesh and Howlett2015). This capacity to act respectively comprises the pooling of authority with international organisations (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2015), the degree of shared rule between sub‐national governments and the national government (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hooghe and Schakel2008), as well as the degree of independence of executive or regulatory agencies (Thatcher, Reference Thatcher2002). Both the delegation of competences and the capacity to act should matter, but there are reasons for why they could matter differently (see the next section).

Against this background, we assume that when policy makers (high‐level bureaucrats, members of government and members of parliaments from governing parties) pursue reforms to recentre authority at the national level, they are policy‐seeking and power‐seeking at the same time (Strøm, Reference Strom1990). This assumption implies that reforms to recentre political authority may serve both instrumental goals (oriented towards problem‐solving) and strategic goals (oriented towards bureaucratic expansion and electoral politics). Yet, we also assume that actors make decisions in a way that is rationally bounded (Jones, Reference Jones1999). It follows that, at first, they cannot always foresee the consequences of their decisions, especially in complex settings such as multilevel polities, that is, of delegating competences away from the nation state. In this sense, reforms that recentre political authority can be understood as second‐order policy effects of multilevel governance dynamics.

General‐purpose jurisdictions

Upward delegation

Scholars of European integration and Europeanisation have long since recognised that participation to EU institutions and negotiations at the EU level provide opportunities to state actors to reinforce their role at national level with respect to other actors (Hix & Goetz, Reference Hix and Goetz2000; Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2012; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1994). In this light, it is plausible to expect that the governments of EU member states have a greater capability of passing these reforms, compared with executives in countries less integrated in general‐purpose jurisdictions. The motivation for such reforms can be twofold: (1) they are confronted with the need to increase their problem‐solving capacity by recentring political authority at the national level (e.g., because they need to implement EU policies); (2) or they pursue recentring to achieve their strategic political goals against other domestic actors.

Upward attribution of the capacity to act

A key measure of the capacity to act is the pooling of authority with a collective body at the international level wherein states relinquish their individual veto powers (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2015). Such pooling typically gives the leeway to international organisations to issue collective decisions to which states may have to comply, as the case of the EU demonstrates. The upward attribution of high capacity to act has two implications for policy making at the national level: On the one hand, extensive pooling of authority at the international level creates incentives for domestic actors to recentre political authority at the domestic level to ‘upload’ a coherent set of preferences to influence the policy process at the international level. On the other hand, when authority is pooled away from the nation state, governments must guarantee effective implementation of international decisions. Thus, they become more likely to devise a coherent national policy strategy through recentring reforms (Ruffing, Reference Ruffing2017; Scholten, & Scholten, Reference Scholten and Scholten2017). Therefore, overall, the motivations of governments to use their reform capability should increase even more, when a high capacity to act is attributed to the general‐purpose jurisdiction under consideration.

Downward delegation

The downward delegation of competences to general‐purpose jurisdictions might also result in recentring authority at the national level. The literature on decentralisation has shown how an increased self‐rule of sub‐national governments allows greater leeway for autonomous policy making at the sub‐national level (Lyall & Tait, Reference Lyall and Tait2004). Against this background, regions may act as ‘policy laboratories’ for other regions and the national government. To adjust to the consequences of newly acquired competencies at lower levels of government, national authorities might be inclined to recentre policy making, either to include some of the lessons learned at lower levels, or to curb sub‐national autonomy by other means. Specifically, policy makers at the national level might need to engage in recentring reforms to ensure the political management and control of sub‐national entities that rose in power (Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Graziano and Bassoli2015; Steurer & Clar, Reference Steurer and Clar2015; Stevenson & Richardson, Reference Stevenson and Richardson2003).

Downward attribution of the capacity to act

The collective capacity to act of sub‐national entities is materialised by mechanisms of informal or formal shared rule among sub‐national governments (Elazar, Reference Elazar1987). Examples of shared rule devices are intergovernmental councils or second chambers of parliament where sub‐national entities can make decisions together (Behnke & Mueller, Reference Behnke and Mueller2017; Stecker, Reference Stecker2016). Accordingly, a greater capacity to act attributed to jurisdictions at the lower level of government might increase the incentives for national governments to recentre authority to be able to deal coherently with these unified collective actors representing the interests of sub‐national units.

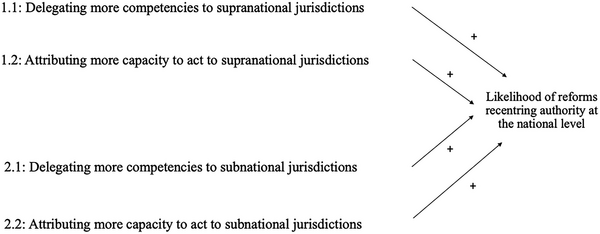

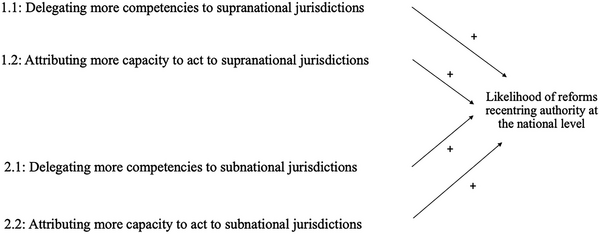

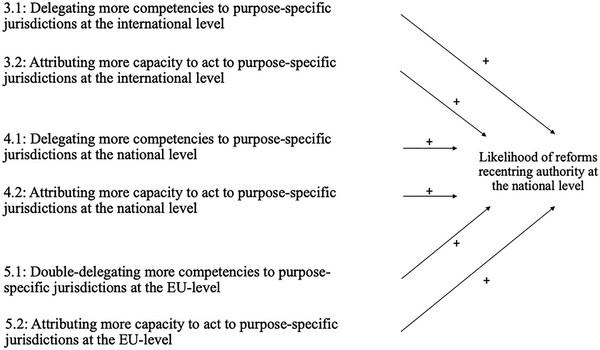

To sum up, we derive four expectations from the above‐discussed literature about what makes reforms recentring national‐level authority ‘more likely’. Figure 1 summarises them.

Figure 1. Expectations regarding general‐purpose jurisdictions.

Task‐specific jurisdictions

Upward delegation

Recent literature on international organisations points to a distinction between wide‐ranging, that is, general‐purpose, international organisations on the one hand and task‐specific ones on the other. The latter are highly specialised, issue‐oriented organisations that tend to develop a niche strategy with respect to their organisational environment (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Green and Keohane2016). The proliferation of these bodies in the last couple of decades has created a governance patchwork at the transnational level (Abbott & Snidal, Reference Abbott, Snidal, Mattli and Woods2009). Nation states have responded to this process by promoting the legalisation of many transnational rules, a process that reinforces the role of the state in transnational regulatory regimes (Bartley, Reference Bartley2014). In this context, delegating political competencies to these sector‐specific international actors creates a situation of fragmented authority and disaggregated sovereignty (Slaughter, Reference Slaughter2004) to which national governments may respond through the recentring of sectoral policies.

Upward attribution of the capacity to act

We also expect that the attribution of a higher capacity to act to task‐specific international organisations, such as the World Health Organisation, eventually results in reasserting the political authority of national governments. Indeed, a stronger capacity to act of such bodies – indicating their capability of making de facto binding decisions in the sectors at stake – will create additional pressures for compliance at the national level. National governments could respond to the trade‐offs associated with these sectoral pressures by enhancing the coherence of domestic governance arrangements through PI and AC reforms that aim at recentring their authority.

Sideways delegation

The delegation of competences to sector‐specific regulatory agencies at the domestic level represents one of the major changes in the structure of national polities during the last decades. These independent regulators have become key actors for refining, monitoring and implementing rules in one or more specific policy sectors (Jordana & Levi‐Faur, Reference Jordana and Levi‐Faur2004). One important consequence of such dynamics is the increased fragmentation of the public sector, resulting in policy silos, incoherence and problems of cooperation (Bouckaert et al., Reference Bouckaert, Peters and Verhoest2010; Christensen & Laegreid, Reference Christensen and Lægreid2006, p. 12). Therefore, as a by‐product of agencification (i.e., the creation of regulatory agencies), a greater demand emerged to overcome this fragmentation (Dahlström et al. 2011, pp. 15–18; Peters, Reference Peters2015, pp. 30–31; Verhoest et al., Reference Verhoest, Bouckaert and Peters2007, p. 332), to which governments might respond by recentring sectoral policies to achieve a more holistic governance style.

Sideways attribution of the capacity to act

Furthermore, governments should have even more incentives to recentre authority when these agencies enjoy a high degree of independence regarding their decisions, budget and management (Gilardi, Reference Gilardi2008; Thatcher, Reference Thatcher2005). Their formal independence from the parent ministry may indeed create a partially autonomous level of governance that deepens the problems associated with the fragmentation of political authority and could eventually trigger a counteraction of the ‘principal’ who delegated regulatory competencies to these agencies. Nevertheless, such a reaction does not entail cutting back agency independence, but aims at better coordinating independent agencies, which play an important role in the policy process and allow for playing blame games (Verschuere & Bach, Reference Verschuere and Bach2012). As agencies tend to act on behalf – and sometimes dominate – the policy field they are responsible for, more formal independence of agencies could result in more policy coordination efforts by the central government (Bouckaert et al., Reference Bouckaert, Peters and Verhoest2010; Peters, Reference Peters2015, pp. 30–31; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Reference Pollitt and Bouckaert2017).

Upward and sideways delegation

Likewise the national level, delegation to agencies also plays an important role at the supranational level, namely in the EU. The establishment of these agencies followed a double delegation process: vertically, from member states to EU institutions and horizontally, from EU institutions to agencies themselves (Coen & Thatcher, Reference Coen and Thatcher2008). They are best understood as networked organisations that largely rely on their national counterparts (Levi‐Faur, Reference Levi‐Faur2011) and act as ‘mini‐commissions’ (Schout & Pereyra, Reference Schout and Pereyra2011) while enjoying substantive autonomy from EU institutions (Busuioc et al., Reference Busuioc, Curtin and Groenleer2013; Ossege, Reference Ossege2015; Wonka & Rittberger, Reference Wonka and Rittberger2010). European agencies typically provide policy advice and support to EU institutions, but they also have extensive regulatory functions, and directly take part in policy‐making processes at the supranational level (Egeberg & Trondal, Reference Egeberg and Trondal2017). As such, they contribute to fostering regulatory cooperation and policy harmonisation among member states and to the implementation of EU policies. Against this background, it is possible that the establishment of an EU agency in a policy field magnifies governments’ incentives for recentring authority at the national level, as it increases the fragmentation of authority and at the same time it implies sector‐specific pressures for compliance, creating a multiplier effect.

Upward and sideways attribution of the capacity to act

The attribution of a high capacity to act to EU agencies should make the recentring of authority more likely. This effect is expected to stem from the capacity of EU agencies to act as brokers between levels of governance and to reconcile the need for coordination at the EU level with the need for coordination at the domestic level (Egeberg & Trondal, Reference Egeberg and Trondal2016). When EU agencies enjoy high independence from EU institutions, they are less constrained by bureaucratic bargaining on the supranational level and could be more impactful at the domestic level. National governments may respond by increasing their recentring efforts to cope with more intrusive top‐down pressures.

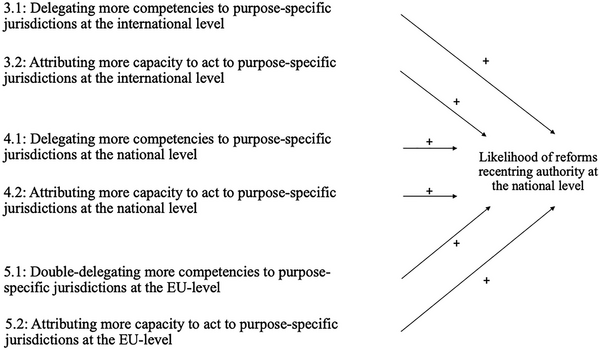

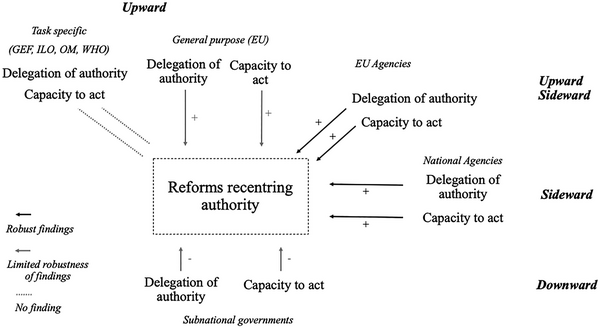

To sum up, we derive six additional expectations from the above‐discussed literature about what makes reforms recentring national‐level authority ‘more likely’. Figure 2 summarises them.

Figure 2. Expectations regarding task‐specific jurisdictions.

Alternative explanations

Although we purposely focus on the consequences of delegation and the attribution of the capacity to act, other possible explanations exist for why governments may pursue reforms recentring political authority. In our empirical analysis, we control for five alternative explanations. (1) The decision to recentre can be a consequence of a specific problem pressure (Herweg et al., Reference Herweg, Zahariadis, Zohlnhöfer, Weible and Sabatier2017), such as rising unemployment rates. (2) Governments led by left‐wing parties may engage more in recentring compared to right‐wing parties because the former typically prefer a more interventionist governing style, including the reshuffling of sectoral public policies (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013; Jordan & Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010; Prontera, Reference Prontera2016). (3) Coalition governments are more likely to put in place such reforms compared to single‐party governments because they are more inclined to change existing policy portfolios (Knotz & Lindvall, Reference Knotz and Lindvall2015; Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Meyer, Bäck, Ceron, Falcó‐Gimeno, Guinaudeau, Hanssen, Kolltveit, Louwerse, Müller and Persson2021). (4) A politicised bureaucracy should also oppose cross‐sectoral reforms to preserve their turf (Painter & Peters, Reference Painter, Peters, Painter and Peters2010). (5) Eventually, we account for the size of public debt; governments might indeed engage in reforms to integrate policies and coordinate public sector organisations to consolidate the public budget. We do not theorise these explanations further since the focus of this article is not to test additional competing expectations but to identify the net impact of denationalization on the recentring of political authority as outlined in the previous sections.

Data on reforms that recentre political authority

A multilevel measure

To examine our hypotheses empirically, we created an original dataset that collects information on reform events operationalizing the recentring of political authority – our dependent variable. Precisely, we use data that measure such reforms in four policy fields and 13 countries (see the Supporting Information for the details). The measurement of the dependent variable combines PI and AC reforms. PI measures changes in policy strategies, policy approaches and laws. AC contains changes in the coordination structure between public sector organisations. The focus of these reforms is above all on the horizontal dimension, but we also included pertinent reforms entailing recentring across levels of government (Trein & Maggetti, Reference Trein and Maggetti2020).

The dataset comprises four policy fields – environment, migration, health and unemployment policy – which represent a selection of diverse cases that differ according to their technical complexity and scope of integration and coordination. Environmental policy represents a case of a technically complex policy with a scope of recentring across policy fields. Reforms incorporate environmental concerns into adjacent policies or unhinge competencies from proximate policy fields and integrate them into a coherent environmental policy field (Jordan & Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010). They operate against a technically complex background (Chiras, Reference Chiras2011).Footnote 1Migration policy is a case of relatively limited technical complexity, combined with recentring across policy fields. Substantively, reforms include the integration and coordination of migration rules with migrant integration capacities related to social policy, for example, social assistance, labour market integration, or education (Entzinger & Biezeveld, Reference Entzinger and Biezeveld2003). Health policy is a configuration of technical complexity and a scope of recentring confined to a single policy field. Notably, we focus on recentring through PI and AC combining preventive and curative health policies broadly defined (Trein, Reference Trein2018). Unemployment policy is an example of a policy of limited technical complexity and a scope of recentring confined to a single policy field. In unemployment policy, such reforms entail the integration and coordination of employment promotion and activation services with cash transfers, for example, unemployment compensation payments and social assistance (Champion & Bonoli, Reference Champion and Bonoli2011). More details regarding the operationalisation can be found in the Supporting Information.

We collected data in 13 countries, which we selected according to their variation on the explanatory variables, notably the delegation of powers to general‐purpose and task‐specific jurisdictions, the type of government, parties in government, national debt, the politicisation of the bureaucracy and the problem pressure within the policy fields. The countries included in the analysis are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. We created a multilevel‐time series dataset, which includes reforms in years, policy domains and countries. The dataset starts in 1980, as after this year, the delegation of competencies to general‐purpose and task‐specific jurisdictions started to augment significantly (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Chapman‐Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair‐Rosenfield2016; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2019; Jordana et al., Reference Jordana, Levi‐Faur and Fernández i Marín2011; Levi‐Faur, Reference Levi‐Faur2011). The dataset ends in 2014.

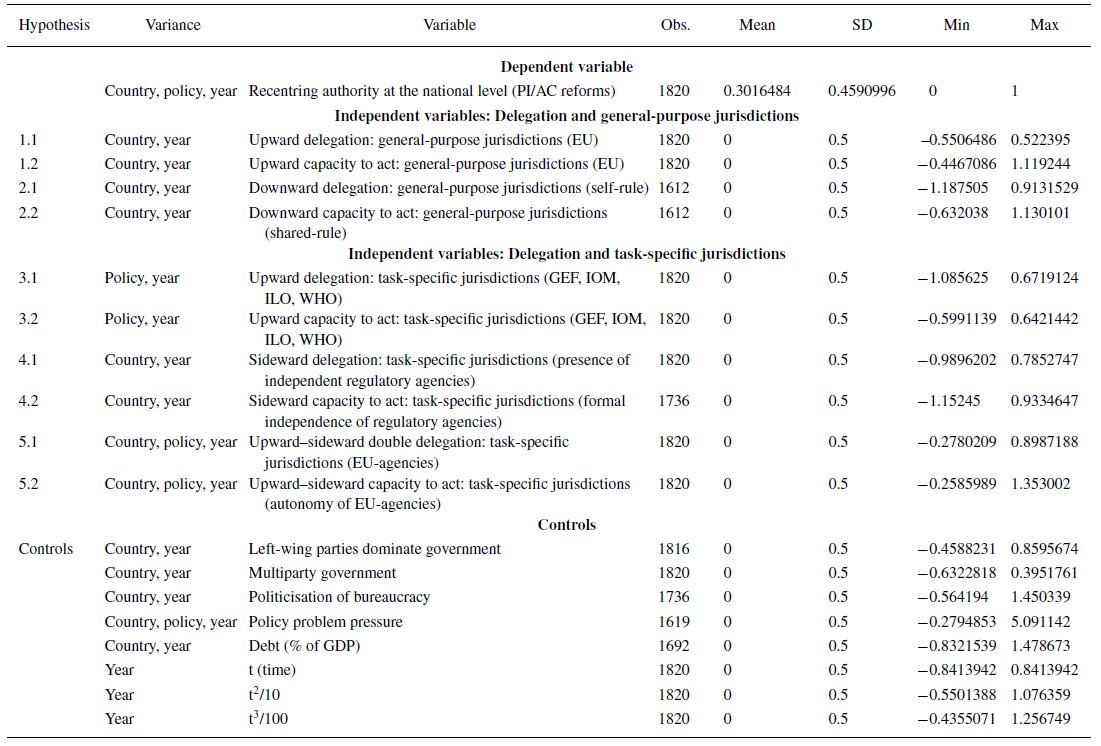

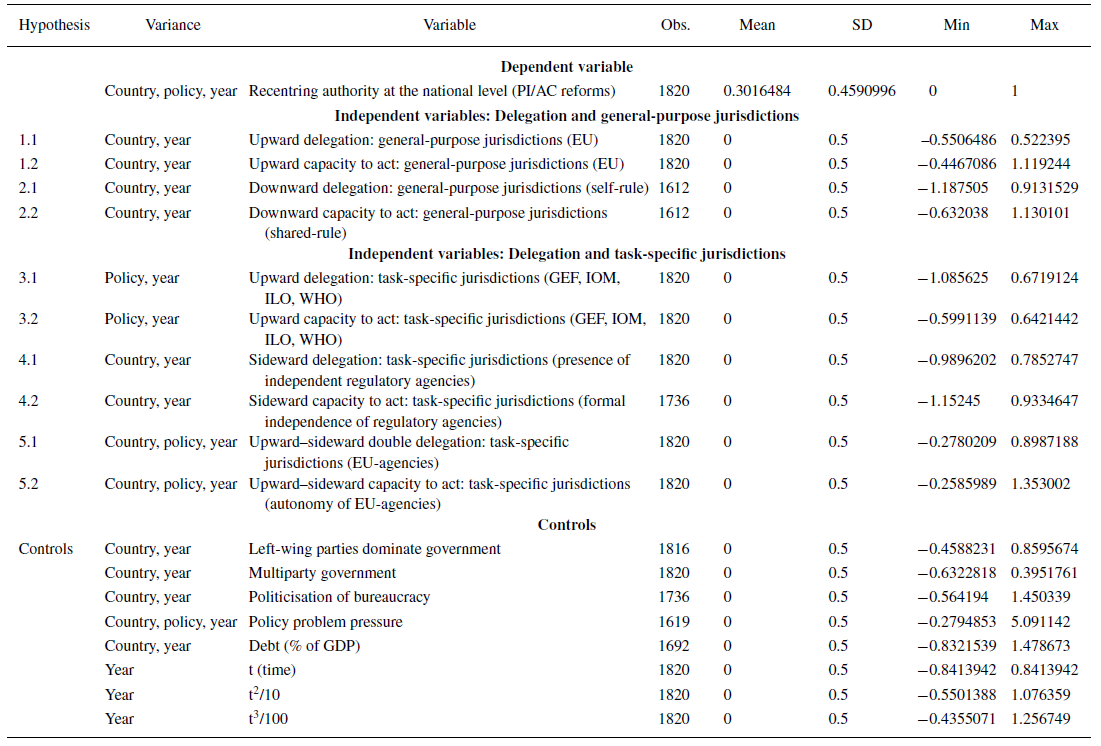

Our dependent variable accounts for recentring reforms with a binary measure (0/1) that records relevant policy and administrative changes per sector in a country and year, which results in a dataset with 1820 observations (Table 1). Therein, we observe 549 recentring events, which represent PI and/or AC reforms. This approach allows us to model the multilevel and diachronic structure of our object of analysis. This way, we created a dataset with reform activities per year that are nested in four fields and 13 countries (Rohlfing, Reference Rohlfing2008; Steenbergen & Jones, Reference Steenbergen and Jones2002). Substantially, we focus on reforms that meet the criteria of PI and AC as discussed in the previous paragraph. When coding the data, we focused on the broader goals of reforms. We did not include reform implementation, that is, to which extent policy makers put the reforms goals into practice. A detailed description of the operationalisation (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information) as well as some examples for such reforms can be found in the Supporting Information to this article.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Table 1 summarises the independent variables included in our analysis, starting with the main explanatory variables. To operationalise upward delegation to general‐purpose jurisdictions (Expectation 1.1), we create a variable that measures the delegation of competencies to the EU (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2019, p. 29, appendix to the book). We use the EU as an instance of delegation to a general‐purpose jurisdiction, as it is unique with respect to other general‐purpose jurisdictions, such as the Commonwealth of Nations or the Organization of American States, in terms of scope and influence on authority of its member states (Wunderlich, Reference Wunderlich2012). To operationalise upward attribution of capacity to act (Expectation 1.2), we use the measure for the pooling of competencies with the EU, which represents a distinct general‐purpose jurisdiction (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2019).Footnote 2

As a measure for downward delegation to general‐purpose jurisdictions (Expectation 2.1), we mobilise the variable measuring self‐rule from the Regional Authority Index, as it captures the extent to which sub‐national governments are autonomous from the central government (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Chapman‐Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair‐Rosenfield2016). To operationalise downward attribution of capacity to act (Expectation 2.2), we employ the measure for shared‐rule from the same dataset as it accounts for the extent to which sub‐national governments can collectively participate in national policy making.

We operationalise upward delegation to task‐specific jurisdictions (Expectation 3.1), in using again the measures on the delegation of authority from the dataset by Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2019) on International Organisations. We select one specific international organisation for each policy field. We use the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to represent the four policy fields. To measure upward attribution of capacity to act of task‐specific jurisdictions (Expectation 3.2), we use the measures for the pooling of authority within these organisations (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2019). For each country, we only coded the variables for those years when it was a member of the respective organisation.

Our operationalisation of sideways delegation to task‐specific jurisdictions (Expectation 4.1) measures the presence of independent regulatory agencies in different sectors, using the data by Jordana et al. (Reference Jordana, Levi‐Faur and Fernández i Marín2011). We create a count variable for the number of independent regulatory agencies over fifteen policy fields (competition, electricity, environment, financial services, food safety, gas, health services, insurance, pensions, pharmaceutics, postal services, security and exchange, telecommunications, water and work safety) that captures the scope of delegation across sectors. To assess the sideways attribution of the capacity to act of task‐specific jurisdictions (Expectation 4.2), we create a compound variable measuring the independence of domestic regulatory agencies. By using regression scores from a principal component analysis, we combine the presence of a civil law system, the age of the agency within the relevant policy field and the politicisation of senior civil servants. We chose these three elements as they appear the least contested ones in their power to predict the independence of agencies (Maggetti & Verhoest, Reference Maggetti and Verhoest2014, p. 248). Ideally, we would use a direct measure of regulatory agencies’ independence over time, but such a variable is not available. Therefore, we construct this proxy measure based on variables that existing research has shown to be strongly correlated with agencies’ independence (see the Supporting Information for the details).

To operationalise the upward‐sideways double delegation to task‐specific jurisdictions (Expectation 5.1), we use a binary variable (0/1) measuring the presence of an EU agency in the policy field. Precisely, if a country is an EU member we coded the variable ‘1’ as of 1990 for environment (since then the European Environmental Agency (EEA) became operational), as of 1993 for public health (in this year the European Medicines Agency (EM(E)A) started to work) and as of 2004 for migration (FRONTEX (European Border and Coast Guard Agency) started to operate). For employment, we did not identify a proper EU agency (Levi‐Faur, Reference Levi‐Faur2011, pp. 818–22). To operationalise upward–sideward attribution of the capacity to act in task‐specific jurisdictions (Expectation 5.2), we use information on the independence of EU agencies (Wonka & Rittberger, Reference Wonka and Rittberger2010, pp. 731–732).

To operationalise alternative explanations for reforms that recentre government, we mobilise several control variables (Table 1). As a measurement for the dominance of left‐wing parties in government, we use the variable gov_party from the Comparative Political Dataset (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Isler, Knöpfel, Weisstanner and Engler2016). To assess multiparty government, we created a binary variable, using the variable gov_type from the same dataset. The operationalisation of the politicisation of the bureaucracy contains regression scores from principal component analysis. Therefore, we created a simple index that ranks the bureaucracy of a country from weakly politicised to very politicised using the information on administrative traditions (Painter & Peters, Reference Painter, Peters, Painter and Peters2010). Subsequently, we use the variable on political corruption in the Quality of Government Dataset (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg, Holmberg, Rothstein, Khomenko and Svensson2017) and combined it with our politicisation index through principal component analysis.

To account for the differences between policy fields, we create a variable that measures the problem pressure that would ignite policy changes in that policy field, using one key indicator that is specific to each policy field. Notably, we focus on greenhouse gas emissions (OECD, 2016c) for environment policy, the number of migrants for migration policy (OECD, 2016b), the unemployment rate for employment policy (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Isler, Knöpfel, Weisstanner and Engler2016) and childhood mortality (OECD, 2016a) for public health. For reasons of comparability, we decided to focus on one key measure per policy field after considering and trying several compound variables for environment and public health. For each of these indicators, an increase in the measure signals higher problem pressure, which should make reforms more likely. Furthermore, we control for the national debt of a country (OECD, 2016d).

Our data measure repeated reform events over time. Thus, it is possible that after some years of increased reform activity the probability to observe further reforms decreases. To account for potential time dependency of the observations in our data, we insert three continuous time variables, starting in 1980: t, t2/10 and t3/100. This procedure is typical for political science analyses of event data (e.g., Gilardi, Reference Gilardi2010; de Francesco, Reference de Francesco2012). We standardise all variables around the mean by two standard deviations to make the measures easily comparable (Gelman, Reference Gelman2008; King, Reference King1986).

Method of analysis

To analyse our data, we estimate probit regression models.Footnote 3 Since our data have a multilevel structure (reforms per year, nested in four policy fields, nested in 13 countries) we fit multilevel models (Steenbergen & Jones, Reference Steenbergen and Jones2002), using the multilevel mixed‐effects regression estimator, which is built‐in into the Stata package (Rabe‐Hesketh & Skrondal, Reference Rabe‐Hesketh and Skrondal2012; Stegmueller, Reference Stegmueller2013). For the main analysis, we estimate two‐level multilevel models: the lower level are reform events per year, which are nested in the higher level of 52 policy fields, four in each country. We clustered the standard errors at the country level, which allows us to interpret the coefficients regarding policy decisions at the national level. The results are the same if we use three‐level models (reforms per year, nested policy fields, nested in countries).

Empirical results

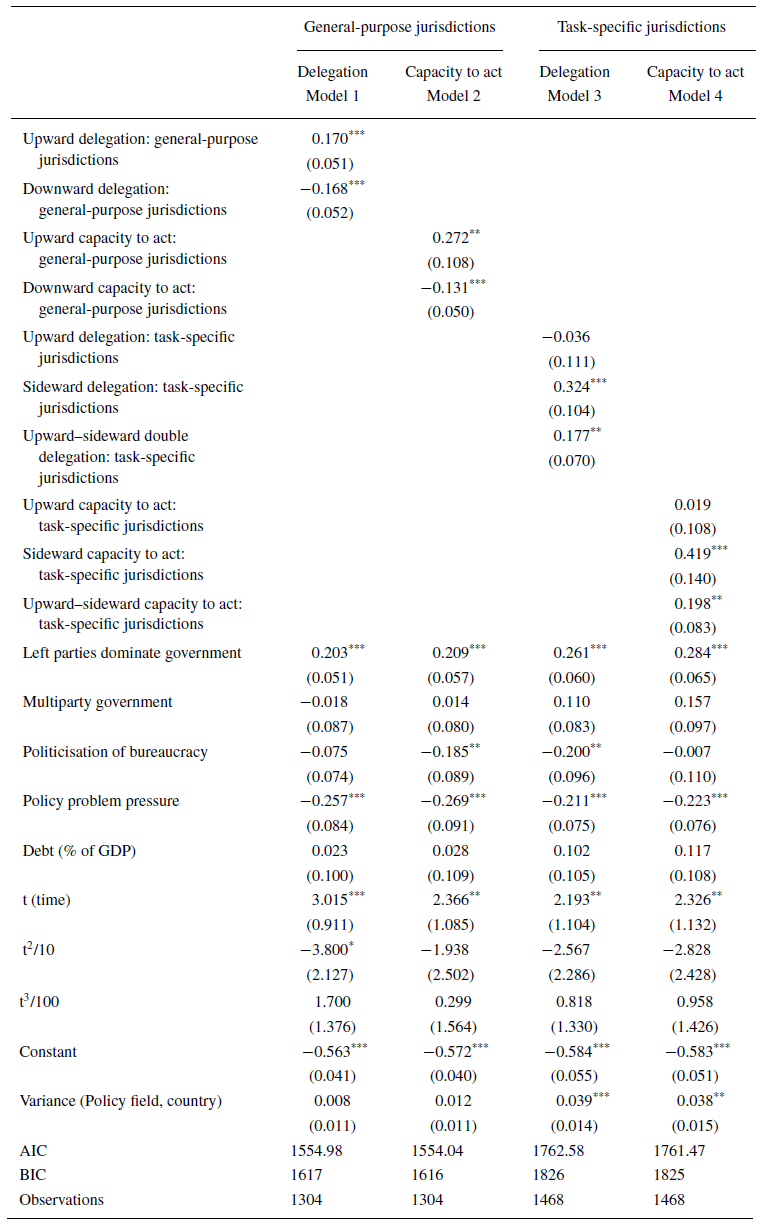

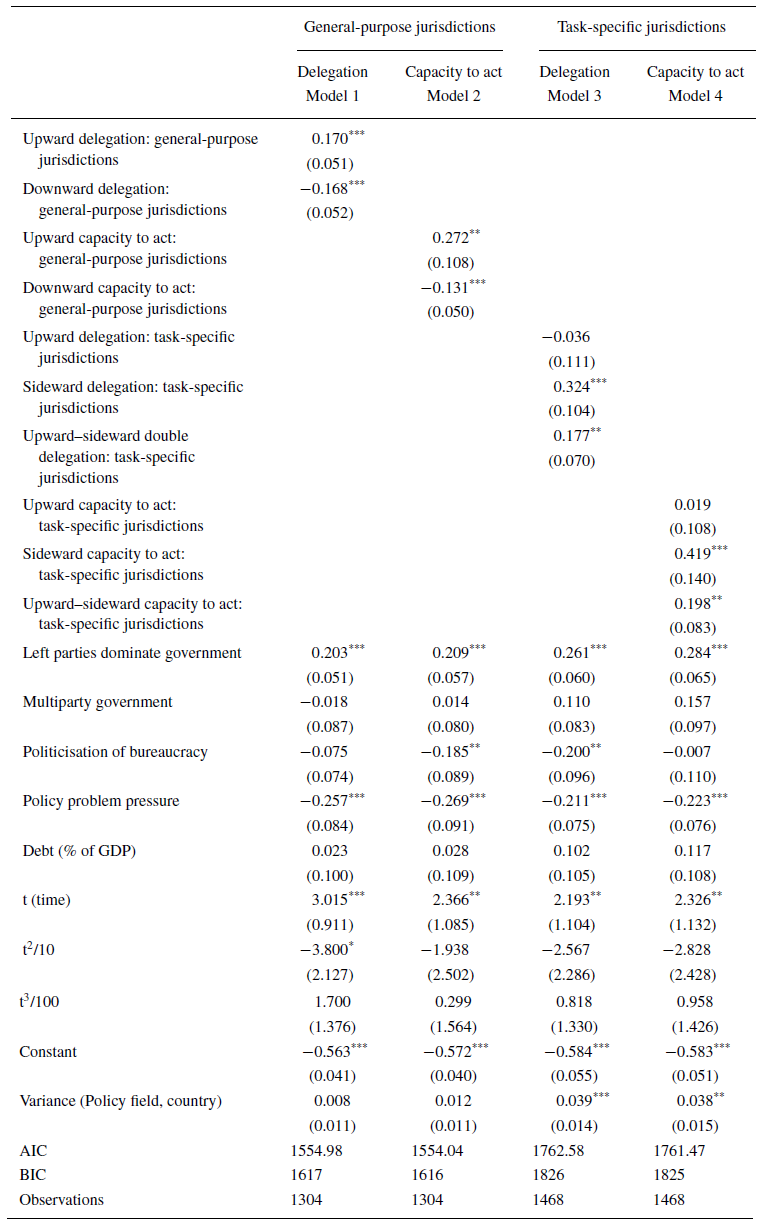

We estimate four regression models to account for the conceptual differences between general‐purpose and task‐specific jurisdictions, but also to account for the correlation between the various independent variables (Table S2 in the Supporting Information). Models 1 and 2 focus on delegation of authority and capacity to act in general‐purpose jurisdictions. Models 3 and 4 deal with task‐specific jurisdictions (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of multilevel regression models (standard errors in parentheses)

*p < 0.1;

**p < 0.05;

***p < 0.01.

The results show that the delegation of competencies to general‐purpose jurisdictions, that is, to the EU level, raises the probability of passing reforms that recentre political authority at the national level. Conversely, the delegation of competences to sub‐national general‐purpose jurisdictions decreases the probability of such reforms (Model 1, Table 2). Similarly, the upward attribution of the capacity to act has a positive effect on such reforms, while downward attribution through shared‐rule has a negative impact on recentring (Model 2, Table 2). The results for task‐specific jurisdictions show that upward delegation does not increase the probability of recentring. Nevertheless, sideways delegation to agencies at the national level and upward–sideward delegation to (EU) agencies result in more reforms recentring political authority (Model 3, Table 2). A higher capacity to act for agencies at the national level and at the European level also increases the likelihood of such reforms, whereas this does not seem to be the case for task‐specific international organisations (Model 4, Table 2). The control variables show that governments dominated by left‐wing parties have a clear preference for such reforms compared to right‐wing parties. What is more, over time, recentring reforms become more likely. Finally, strong problem pressure as well as a politicised bureaucracy reduce the likelihood of such reforms.

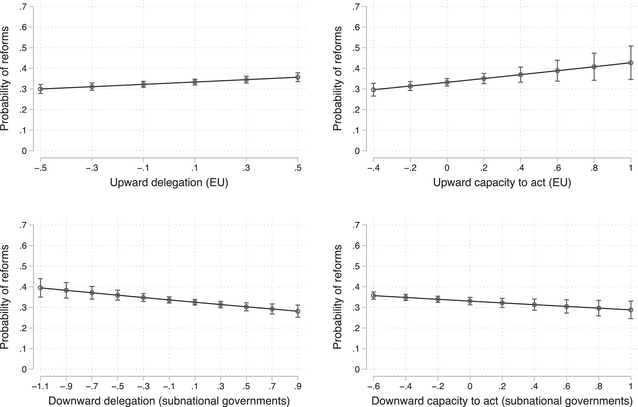

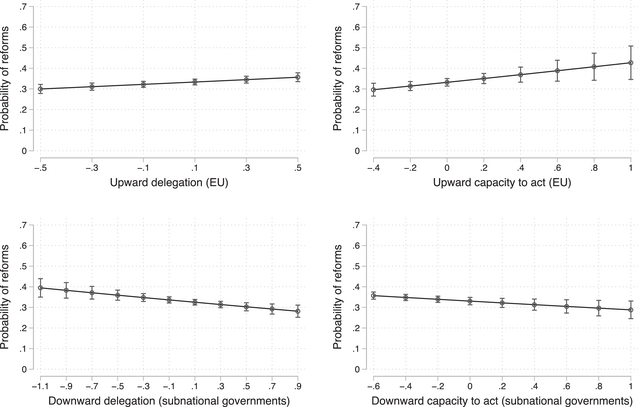

To deepen the analysis of our findings, we turn to a graphical presentation of the results. The graphs show the marginal effects for general‐purpose jurisdictions and illustrate how the delegation of competences to the EU increases the probability of reforms recentring political authority by around 6 per cent, when we compare the two extreme values of the variable. Our analysis of the capacity to act related to the EU shows that the probability of reforms even raises more than 10 per cent between the extremes of the variable. In this case, the 95 per cent confidence intervals are, however, much wider for the higher values of the capacity to act variables. These results support Expectations 1.1 and 1.2, which suggest that upward delegation to a general‐purpose jurisdiction, and the attribution of capacity to act, make the recentring of political authority more likely (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Marginal effects for general‐purpose jurisdictions (covariates balanced).

The graphs also show that delegation of competencies to general‐purpose jurisdictions at the sub‐national level decreases the probability for reforms recentring government by around 11 per cent when we compare the values at the extremes of the variable measuring self‐rule. In addition, the higher capacity to act for sub‐national governments reduces the likelihood of reforms by around 6 per cent between the extremes of the variable. These results disconfirm Expectations 2.1 and 2.2. More capacity of sub‐national governments to act on their own as well as an increased political clout of sub‐governments in the policy process at the national level do not trigger recentring reforms at the national level (Figure 3).

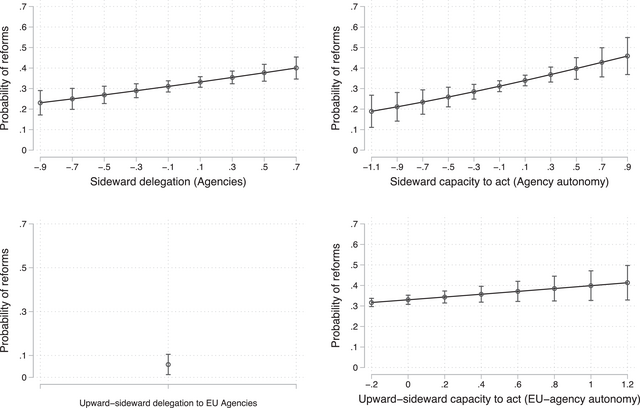

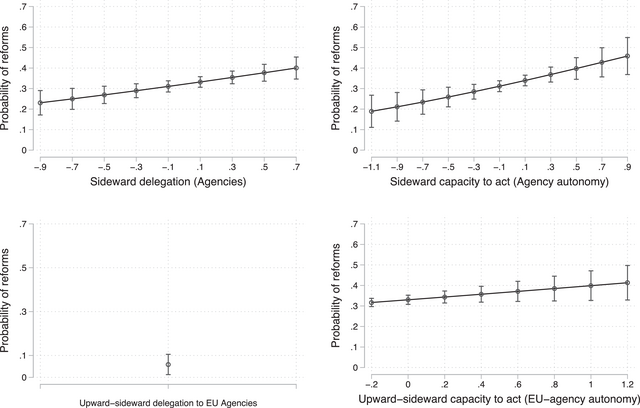

Concerning task‐specific jurisdictions, our findings suggest that the growth in number of independent regulatory agencies increases the likelihood of recentring reforms. Precisely, the probability of such policy changes doubles when we compare the extreme values of the variable. A higher capacity to act for agencies, that is, if they are more independent from their political ‘principal’, raises the probability of such reforms even more (from 21 to 45 per cent). These results support Expectations 4.1 and 4.2, according to which sideways delegation and sideways denationalization through capacity to act increases the likelihood of such reforms (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Marginal effects for task‐specific jurisdictions (covariates balanced).

Our findings also support Expectations 5.1 and 5.2, which hold that upward‐sideways double delegation as well as higher capacity to act for these agencies positively affect the adoption of reforms recentring political authority. Precisely, the results indicate the probability of reforms increases around 7 per cent if an EU agency is present in the policy field. Furthermore, the likelihood for reforms increases by around 10 per cent if we compare the extreme values of the measure indicating autonomy of the EU agency in the policy field (Figure 2).

To assess the ‘robustness’ of our findings, we pursue three avenues. First, we assess the substantial robustness of our operationalisation of the upward denationalization in general‐purpose jurisdictions, by using membership in international organisations for non‐EU members (Table S4 in the Supporting Information). Second, we conduct robustness checks with alternative estimation strategies. Since our data uses only 13 countries, the estimated country effects could be biased (Bryan & Jenkins, Reference Bryan and Jenkins2015). To account for this issue, we ‘jackknife’ the countries (van der Meer et al., Reference van der Meer, Te Grotenhuis and Pelzer2010) and we estimate linear probability models using the Satterthwaite's sample correction strategy (Elff et al., Reference Elff, Heisi, Schaeffer and Shikano2021) (Tables S5 and S6 in the Supporting Information). Third, we estimate additional models controlling for government effectiveness and include a categorical variable for the difference between policy fields (Tables S7 and S8 in the Supporting Information). Overall, the findings are robust to these additional tests.

Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we analyse how denationalization, understood as the delegation of competences to jurisdictions beyond the central government, as well as their capacity to act, may lead to formal policy changes that ultimately recentre political authority at the national level. We develop expectations on the mechanisms by which upward, downward and sideways delegation of competencies, as well as the attribution of capacity to act, may drive this recentring through PI and AC reforms. To investigate these expectations, we use an original dataset with information on such reforms in 13 countries and four policy fields over 34 years.

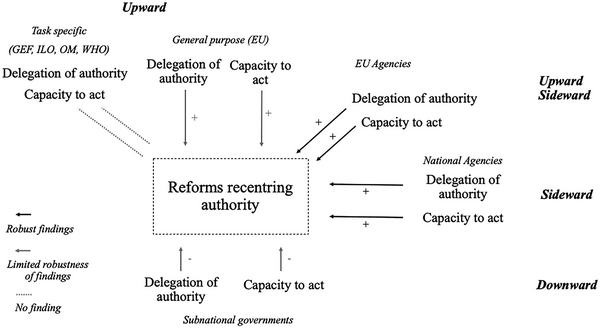

Our results (summarised in Figure 5) indicate that sideways delegation of competencies, notably to independent regulatory agencies, as well as upward‐sideways double delegation of competencies to EU agencies raises the probability that governments pass reforms recentring political authority. The findings also suggest – although with less statistical robustness – that upward delegation to a general‐purpose jurisdiction has a positive effect on the occurrence of such reforms. What is more, the higher the agencies’ capacity to act on their own – that is, the more independent they are from their ‘principal’ – the more national governments are likely to recentre political authority. This finding indicates that governments seek to countervail fragmentation and regain control over increasingly autonomous actors through integration and coordination efforts rather than by cutting back their power (be it because they will not or cannot do otherwise).

Figure 5. Summary of the results.

Our results also indicate that the delegation of competencies to general‐purpose jurisdictions at lower levels (that is, sub‐national governments) makes reforms that recentre political authority less likely. The same occurs if sub‐national governments enjoy greater rights to participate in the policy process at the national level. Under such conditions, recentring reforms are more likely to happen at the sub‐national level, but not at the national level. Moreover, the delegation of competencies to task‐specific jurisdictions at the international (non‐EU) level does not seem to influence reforms recentring political authority.

The focus of our analysis is on examining ways by which denationalization through delegation and the attribution of the capacity to act to jurisdictions beyond the nation state ultimately impacts on the recentring of political authority at the national level. We identify this connection by controlling for several alternative explanations; however, the scope of our research is explorative and geared towards theory building. Thereby, we do not engage in causal analysis stricto sensu by using a causal inference research design. We leave this task for future research.

Keeping this caveat in mind, our findings have four main implications for political research. First, the analysis points to a particularly significant role of the EU regarding the recentring of political authority at the domestic level. This insight deserves special attention and needs to be explored by further research. We expected that double delegation creates a multiplier effect that magnifies the incentives for national governments to recentre their political authority. The fact that sector‐specific EU agencies drive these reforms rather than EU membership per se corroborates this expectation. In this sense, the EU resembles a ‘policy state’ (Orren & Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2017) that evolves by creating legitimacy through new policies, which implies the necessity to engage in an increasingly higher level of policy maintenance for national governments (Mettler, Reference Mettler2016). Second, our results show that downward delegation makes the recentring of authority less likely, which is contrary to what we hypothesised. One potential explanation for this puzzling finding is that sub‐national governments can achieve a stronger veto position against recentring at the national level compared to agencies and international organisations. In any case, multilevel dynamics appear more complex than stylised accounts of multilevel governance.

Third, our research has implications for the contribution of the multilevel governance framework to policy process research. We have shown that denationalization ultimately induces domestic reforms that cut across policy sectors and administrative units, as for by a rebalancing movement. Denationalization creates a demand for policy action as it generates new problems to be solved and, at the same time, provides new opportunities to actors in favour of recentring authority at the level of the central government. Therefore, the dynamics at work in a multilevel polity challenge the policy sub‐system logic of policymaking of national governments. Innovative political entrepreneurship seems required to manage these challenges by actively combining – or even transcending – different sectoral policies. Fourth, denationalization is commonly understood as a hollowing out of the nation state. Our analysis indicates that denationalization triggers the recentring of political authority in multilevel governance, ultimately strengthening the role of the central government in terms of political steering. This is not a paradox, but a consequence of the unfolding of complex multilevel dynamics, involving unintended effects. As a matter of fact, multilevel governance does not necessary unravel the nation state, with respect to the role of the government; it may however create problems for democracy, as crucial reforms restructuring political authority at the national level appear to be largely determined by exogenous factors.

All in all, this article opens two main avenues for future research. First, there is a need to additionally theorise the relationships uncovered by this research. Future scholarship could focus on developing further the causal mechanisms that underpin the expectations developed in this article to better understand the goals and the strategies of different types of actors regarding reforms recentring political authority. Second, future research should examine whether such reforms improve the problem‐solving capacity of the nation state. In other words, do PI and AC reforms increase the ability of governments to instrumentally deal with pressing problems, such the climate emergency? Or, do these reforms turn out to be rather strategic adjustments to maintain the influence and functionality of the national government in times of denationalization?

Acknowledgements

We thank all colleagues who provide us with helpful comments on this paper, notably at EPSA 2017, MPSA 2018, ECPR General Conference 2019. We thank the editors of the journal and four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We are grateful to the Swiss National Science Foundation for generous financial support, Grant Number: 162832 + 185963.

Open access funding provided by Universite de Lausanne.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used for this article are available here: https://osf.io/upfb6/; Identifier: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/UPFB6. We deposited the dataset in .dta format as well as a Stata .do file to replicate Table 2, Figures 3 and Figure 4 in this paper as well as the regression analyses in the Supporting Information.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: