Impact statement

Long-term monitoring is essential for assessing the current status and trend of environmental resources. Monitoring is critically important in the world’s rangelands, where grazing and climate are major drivers of ecosystem change. We assessed rangeland change over 40 years at a research station in arid eastern Australia. Our study reveals marked declines in plant community structure and environmental quality, and the capacity of the landscape to support livestock. Such long-term studies are few, yet extremely valuable if we are to understand how rangelands change across long time scales.

A contribution to the Special Issue on the work of Professor Walt Whitford

This manuscript is a contribution to the Special Issue dedicated to the work of Professor Walt Whitford. During the latter part of his career, Walt was employed with the US Environmental Protection Agency where he undertook research to develop monitoring tools for drylands and deserts, and where he used long-term data to explore questions about deserts and their biota. Given his interests in monitoring and long-term data sets, it is appropriate that this study forms part of the Special Issue dedicated to his work.

Introduction

Rangelands cover more than half of Earth’s terrestrial ice-free land surface, support about 40% of its human population and provide animal products (meat, milk, hide and a form of currency) to millions of people worldwide (Godde et al., Reference Godde, Boone, Ash, Waha, Sloat, Thornton and Herrero2020). Yet, rangelands are at risk, from land-use intensification such as overgrazing, land clearing, timber harvesting and fossil fuel extraction, to climate-induced changes that lead to soil degradation, loss of productive potential and unsustainable livelihoods (Boone et al., Reference Boone, Conant, Sircely, Thornton and Herrero2018; Godde et al., Reference Godde, Boone, Ash, Waha, Sloat, Thornton and Herrero2020; Angerer et al., Reference Angerer, Fox, Wolfe, Tolleson, Owen and Ramesh2023). These effects are often incremental, disguising long-term changes that go unnoticed across generations (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair2005). Managing rangelands requires a long-term perspective, often over half a century, to capture changes in how they function and their likely temporal trajectory (e.g., Kleinhesselink et al., Reference Kleinhesselink, Kachergis, McCord, Shirley, Hupp, Walker, Carlson, Morford, Jones, Smith, Allred and Naugle2023). Given the close connection between climate and pastoralism, the predominant land use in rangelands (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Poore, Ruiz‐Colmenero, Letnic and Soliveres2016), resource monitoring is critical to provide managers with evidence that allows them to adapt to climatic and environmental fluctuations.

Australia’s rangelands have undergone substantial change in the relatively short period since European colonisation (~230 years). This has largely been due to land management practices that are not aligned with best practice rangeland science, and increases in exotic species such as goats, rabbits and, more recently, deer (Noble and Tongway, Reference Noble, Tongway, Russell and Isbell1987; Ludwig and Tongway, Reference Ludwig, Tongway, McKenzie, Hyatt and McDonald1992; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Poore, Ruiz‐Colmenero, Letnic and Soliveres2016). Sustained, long-term monitoring of rangeland quality (status) and trend (trajectory of change) has often been hampered by poor planning, high cost and a lack of sustained government and industry support (e.g., Vanderpost et al., Reference Vanderpost, Ringrose, Matheson and Arntzen2011), and is often limited to studies carried out by dedicated individuals (Kingsford, Reference Kingsford1999) or institutions over only a few decades (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair2005; McAlpine et al., Reference McAlpine, Thackway and Smith2014). Australia has a variable history of successful long-term rangeland monitoring programmes (McAlpine et al., Reference McAlpine, Thackway and Smith2014). For example, the Western Australian Rangeland Monitoring System (WARMS) with its complex of more than 1,600 sites (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Novelly and Thomas2007) was downgraded, and the Centralian Range Assessment Program in the Northern Territory (Bastin, Reference Bastin1977) has morphed into a multi-tiered system of monitoring the status of pastoral resources on more than 2,200 sites (Owen, Reference Owen2009) and long monitoring (NT 2009). Monitoring programmes are costly to sustain and rely heavily on infrastructural support from governments (Watson and Novelly, Reference Watson and Novelly2004; Novelly et al., Reference Novelly, Watson, Thomas and Duckett2008). There is now a move to replace extensive multi-site, state-based monitoring programmes with broad national programmes (e.g., TERN, Sparrow et al., Reference Sparrow, Foulkes, Wardle, Leitch, Caddy-Retalic, van Leeuwen, Tokmakoff, Thurgate, Guerin and Lowe2020) that are unlikely to be able to answer important questions about rangeland change simply because they lack sufficient replication in space and time.

Two rangeland programmes aimed to examine the status of rangelands in eastern Australia, across about 42% of the land area of New South Wales (NSW). These were the Western Lands Lease Management Plan scheme (WLLMP) and the NSW Rangeland Assessment Program (RAP). Much of the arid and semi-arid rangelands in NSW is held under leasehold tenure, with ownership vested in the Crown. In the mid-1960s, the Western Lands Commission engaged the NSW Soil Conservation Service to undertake detailed surveys of all pastoral leases in the Western Division of NSW. These surveys included an assessment of biophysical resources (plants, soils and erosion) and the condition of property infrastructure (roads, fences and watering points) to assess and map ‘safe carrying capacity’ for livestock (sensu Condon, Reference Condon and Stewart1968). The WLLMP surveys amassed considerable information on the status of pastoral leases at the time of the survey, but involved only a one-off survey.

In the late 1980s, the NSW Soil Conservation Service developed and operationalised a rangeland monitoring programme (NSW RAP, Green et al., Reference Green, Hart and Prior1994) to assess the condition of the main rangeland vegetation communities in the Western Division of NSW to enable land managers to make informed decisions about current and future management of rangelands. The term ‘condition’ is highly value-laden and context-dependent. For example, good condition sites for grazing might be characterised by a high biomass of palatable grasses. Conversely, good conditions for conservation might involve a mixture of woody plants and grasses, with lower biomass of palatable species. In this manuscript, we avoid the term condition or health, and focus on the status of the vegetation and soils. Under the RAP programme, annual measurements were made of plant community composition and production, woody plant density and cover, and the status of the soil at about 350 sites. Both the WLLMP and RAP programmes were discontinued in the early 2010s due to waning government support. Information from both programmes has subsequently been used to assess changes in woody plant density and cover (Booth and Barker, Reference Booth and Barker1979), bladder saltbush (Atriplex vesicaria) dieback (Clift et al., Reference Clift, Semple and Prior1987), to examine long-term trends in vegetation in the semi-arid woodlands (Eldridge and Koen, Reference Eldridge and Koen2003) and to report on the status and trend of Australia’s rangelands (Eyre et al., Reference Eyre, Fisher, Hunt and Kutt2011).

Here we report on a study in 2022 and 2025, where we reassessed a suite of biophysical attributes (plants, soils and erosion) of rangelands at Fowlers Gap, a pastoral property managed by the University of NSW, at two spatial scales (across the entire station and in one paddock). We subsequently compared our results with information collected: (1) once in 1982 across the whole station (WLLMP at scale of 1:50,000), (2) once in 1986 at a scale of 1:10,000 in one paddock only (North Mandleman’s Paddock) and (3) 20 times between 1990 and 2022 (as part of the RAP; 300 m × 300 m site). All reassessments used the same procedures as those used in the original surveys. We used Fowlers Gap as our model system to explore changes over a relatively long time because it has a long history of undertaking arid zone research, and maintains long-term stocking rate and climatic data (Hannah, Reference Hannah1984; Macdonald, Reference Macdonald2000). By comparing contemporary information on plants, soils and environments, we aimed to acquire a better understanding of long-term ecological change in the rangelands of western NSW.

Methods

Study area

The Fowlers Gap Arid Zone Research Station occupies 39,200 ha about 110 km north of Broken Hill, NSW, Australia (−31.30o, 141.71o). The climate is arid (aridity index = 0.17, Harwood et al., Reference Harwood, Donohue, Harman, McVicar, Ota, Perry and Williams2016) with most of the 240 mm average annual rainfall (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Stewart, Sutton and Eldridge2024) falling in summer. Temperatures range from 11.5 °C in winter to 27.3 °C in summer.

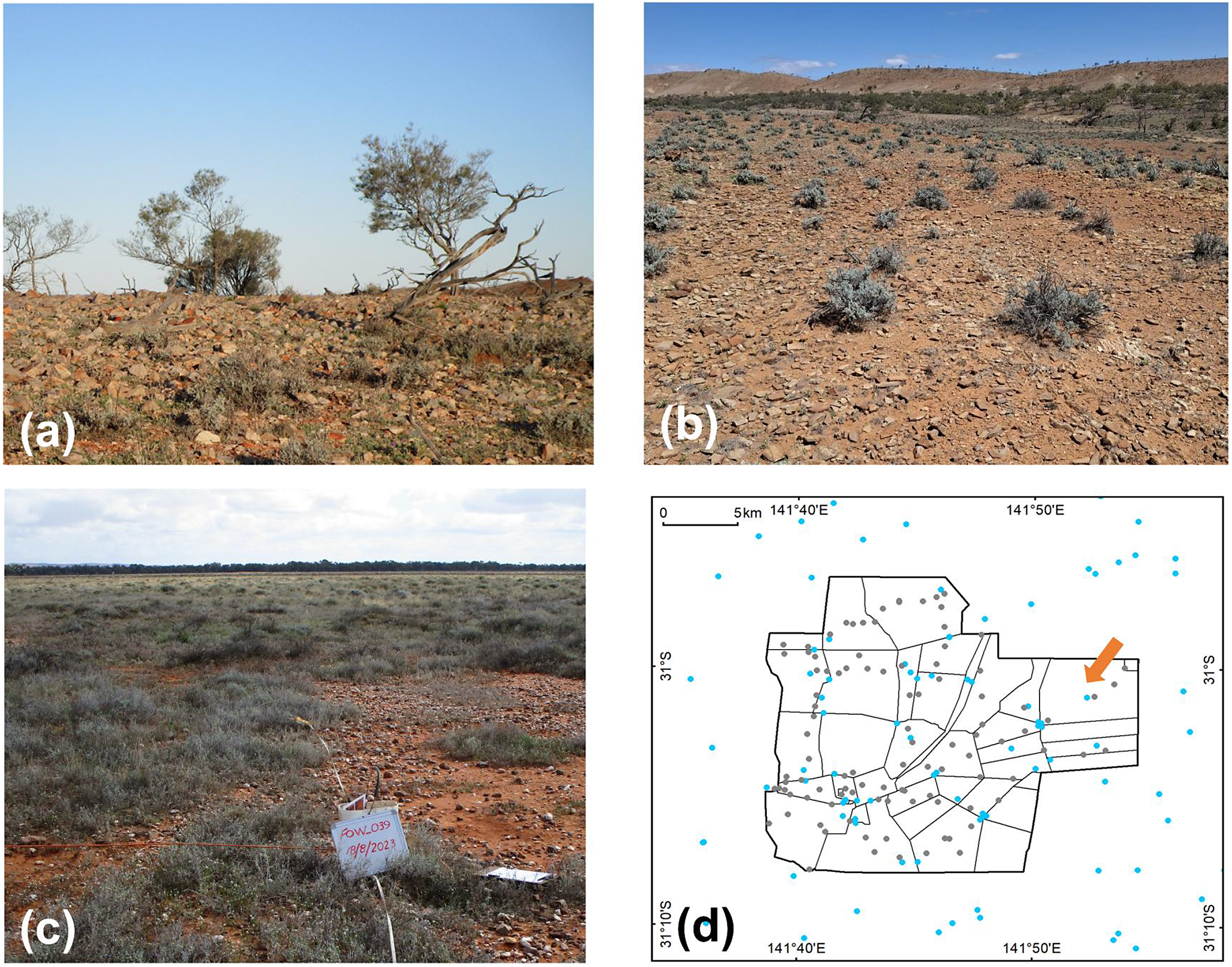

The geology comprises steeply dipping (up to 70°) Precambrian metasediments (overlain by Tertiary and Quaternary sediments and alluvium). Geomorphologically, the area comprises three broad landform types: (1) ranges and hills (Figure 1a), (2) undulating footslopes and terraces (Figure 1b) and (3) extensive alluvial plains (Figure 1c, Mabbutt, Reference Mabbutt and Mabbutt1972; Akpokodje, Reference Akpokodje1987). Soils of the ranges are generally shallow sandy loams, while the footslopes and terraces are dominated by red clay soils with a variable cover of quartz gibbers (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Fink, Chappell and Melville2014). The alluvial plains dominate the eastern side of the ranges, are dissected by floodouts and are subject to periodic flooding. Their soils are dominated by a mixture of clay soils and red duplex clay loams (Eldridge, Reference Eldridge1988). The vegetation represents a gradient in pastoral productivity from low productivity in the ranges to high productivity on the plains (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Stewart, Sutton and Eldridge2024).

Figure 1. Clockwise from top-left. (a–c) Images of the Ranges, Footslopes, and Plains. (d) Map of Fowlers Gap station showing the distribution of livestock watering points. The arrow indicates North Mandleman’s Paddock. Photographs: DJ Eldridge.

The vegetation is characterised by low woody and open shrub-steppe (Burrell, Reference Burrell and Mabbutt1973) dominated by shrubs and sub-shrubs of the family Chenopodiaceae. The dominant species on the ranges and footslopes are the tree Acacia aneura, shrubs Maireana astrotricha, A. vesicaria and Maireana pyramidata, and groundstorey plants Sclerolaena spp. The plains are dominated by Maireana aphylla and perennial grasses such as Astrebla spp. Patches of the shrub Acacia victoriae are scattered across the station, particularly along drainage lines.

Mapping the biophysical features: WLLMP Program

The WLLMP Scheme commenced in 1967 to assess the ‘safe carrying capacity’ of grazing leases in western NSW. This calculation of safe carrying capacity was based on the status of attributes that are known to influence carrying capacity. These included biophysical attributes, such as rainfall amount and seasonality, slope, soil type, the extent to which an area of land receives additional water from upslope (redistributed runoff), the type and degree of erosion and the characteristics of the vegetation (type, palatability and cover) across different parcels of land (land classes).

To assess carrying capacity, the characteristics of a given land class were compared with those on a well-managed property (the ‘base’ property) for which long-term data on carrying capacity were available. This base property, located in north-western NSW, received an average annual rainfall of 254 mm, with a typical land class (area of similar topography, soils and vegetation) having a gently undulating topography with deep red sandy soils dominated by open mulga (A. aneura) woodlands with woolly butt (Eragrostis eriopoda) pastures of moderate to high palatability and productivity. Long-term stocking records for the base property revealed that this land class supported 20 dry sheep equivalents (DSE) per 100 ha on average, with an average annual rainfall of 254 mm (Condon, Reference Condon and Stewart1968). The physical and biological attributes (rainfall, slope, topography, vegetation, erosion, etc.) of this particular land class were all given an index value of 1.0. So, for example, soils that were inherently less fertile, had lower moisture retention or higher erodibility than soils on the base landclass were assigned rating values <1.0. Conversely, rating values for plants that were considered superior in palatability, forage value or perenniality, or provided drought forage were given a rating value >1.0 (Condon, Reference Condon and Stewart1968).

Extensive rating tables were developed based on differences in rainfall, slope, soil fertility, water holding capacity and erodibility, the presence of additional run-off water, type, cover and density of different tree species (Condon, Reference Condon and Stewart1968). Rating tables were used directly by the NSW Soil Conservation Service to assign values to those factors for any land class being assessed. The rating values for all of the factors were then multiplied by the base rating of 20 to provide an overall ‘safe carrying capacity’ for a particular land class, assuming that the whole site is within the watering range of livestock (Condon, Reference Condon and Stewart1968). This required an assessment of the distribution of livestock watering points (Figure 1d). By mapping different land classes with different combinations of biophysical and biological attributes and calculating their safe carrying capacity, the Soil Conservation Service was able to derive a total number of livestock that they considered ‘safe’ for the whole property. Rating values produced using this procedure (Condon, Reference Condon and Stewart1968) were about 10% lower than the average DSE values run in the district; in other words, most pastoralists were running 10% more livestock than would be assessed under the WLLMP scheme.

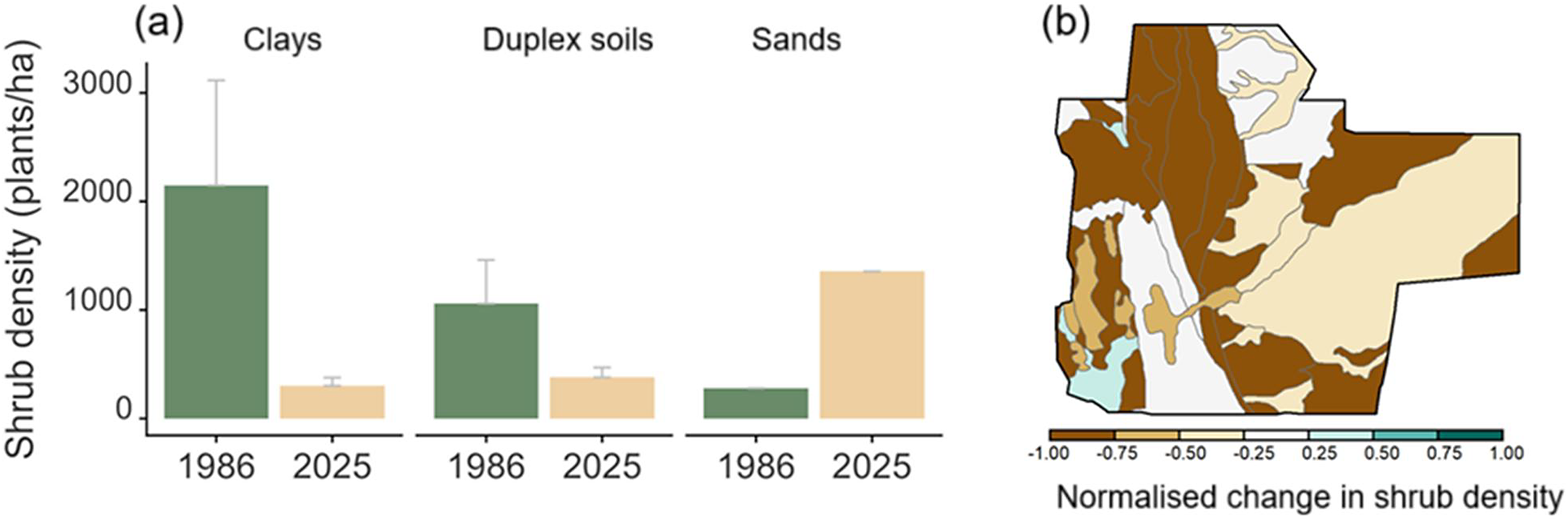

We undertook two reassessments at Fowlers Gap using the same WLLMP procedure. In 2022, we reassessed 105 sites across the whole station using the same land class boundaries identified in 1982 at a scale of 1:50,000. The same rating tables were used to update information on the biophysical and biological characteristics of each land class. Second, in 2025, we reassessed changes in shrub density at a finer scale of 1:10,000 in North Mandelman’s Paddock (Plains). This paddock was originally assessed in by the first author in 1986 to determine pastoral loads across three soil types (clays, duplex soils and sands). The paddock was revisited in 2025 to determine shrub density at 72 locations across 17 land units using the same basic criteria used in the WLLMP procedure described above. In all WLLMP assessments, we are unable to present data for different shrub species (from the family Chenopodiaceae) as the original methodology lumped Maireana spp. and A. vesicaria shrubs together.

Monitoring rangelands: the RAP

In the mid-1980s, the NSW Soil Conservation Service launched the RAP. The programme aimed to determine the status of the main vegetation communities across large grazing leases in western NSW in order to make sound environmental decisions on rangeland management (Green et al., Reference Green, Hart and Prior1994). The programme emphasised the capacity of rangelands to produce forage and sustain grazing; therefore, in the context of grazing, preferred sites would be floristically diverse, dominated by perennial grasses, abundant plant biomass, little erosion and a lack of woody plant encroachment (Green et al., Reference Green, Hart and Prior1994). Thus, from a pastoral perspective, ‘healthy’ sites would be productive sites for livestock.

At each of about 350 sites, 52 quadrats of 0.5 m2 were placed along four transects centrally located within large plots of 300 m × 300 m. Annual measurements were made of plant species composition by biomass using the comparative yield, dry weight rank procedures (Friedel et al., Reference Friedel, Chewing and Basin1988) with photostandards (Friedel and Bastin, Reference Friedel and Bastin1988), the status of the soil, and the cover and density of woody plants, including both palatable and unpalatable. Two sites were established at Fowlers Gap, one in each of North Sandstone (Footslopes, Figure 1b) and Conservation (Plains, Figure 1c) paddocks. The sites were measured 16 times between 1990 and 2011, and again in 2022. In 2022, we measured the same features using the same protocols at 52 quadrats at both sites.

Statistical analyses

Differences among years and sites were examined using linear models with lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in the R statistical package (R 4.4.1 version, R Core Team, 2025). We used the JWileymisc package in R for general diagnostics (Wiley, Reference Wiley2025).

Results

Temporal changes in biophysical attributes and safe carrying capacity

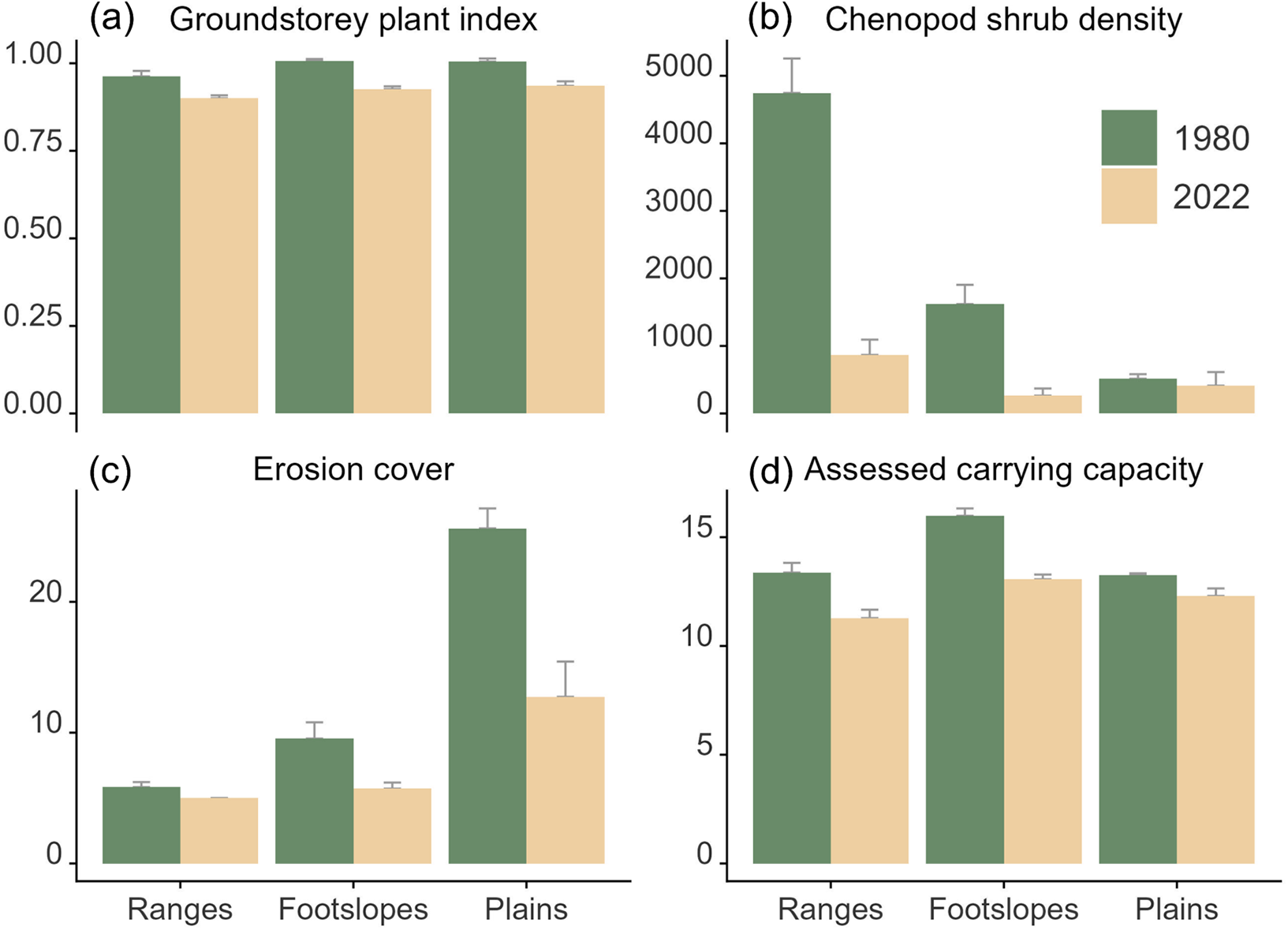

We detected substantial changes over the 40-year period for both station and paddock surveys. For the station-wide WLLMP survey, the pasture rating index declined by an average of 8%, consistently across ranges, lowlands and plains (Figure 2a). This pasture rating index was based mainly on the palatability of different species to livestock and, to a lesser extent, their ability to provide a stable soil surface. The density of shrubs from the family Chenopodiaceae (Maireana and Atriplex) declined markedly (78%), particularly on the ranges (145%; Figure 2b). Declines in shrub density were unrelated to the original density, that is, sites with high density did not necessarily show the greatest declines. Surprisingly, the extent of erosion (percentage cover) also declined across all landscape types (43%), but most notably on the plains (Figure 2c). This was largely due to reductions in the extent of wind and water erosion (wind sheeting and scalding).

Figure 2. Differences in (a) the index of groundstorey plant cover (unitless, see Methods), (b) density of shrubs from the family Chenopodiaceae (shrubs ha−1), (c) cover of erosion (%), and (d) assessed livestock carrying capacity between 1982 and 2022 (dry sheep equivalents per 100 ha).

Overall, assessed ‘safe carrying capacity’ declined by 14.6% across the station, from 14.5 to 12.4 DSE per 100 ha. These declines were evident on the ranges and on the footslopes, but not on the plains (Figure 2d). We acknowledge, however, that in the 1982 study, 1,366 ha were considered ungrazed, that is, out of the grazing range of sheep (>3 km from water). However, when we accounted for these areas that are now fully watered (North Mandleman’s and Salt Paddocks), there is a slightly greater decline (11.9 dry sheep equivalents per 100 ha).

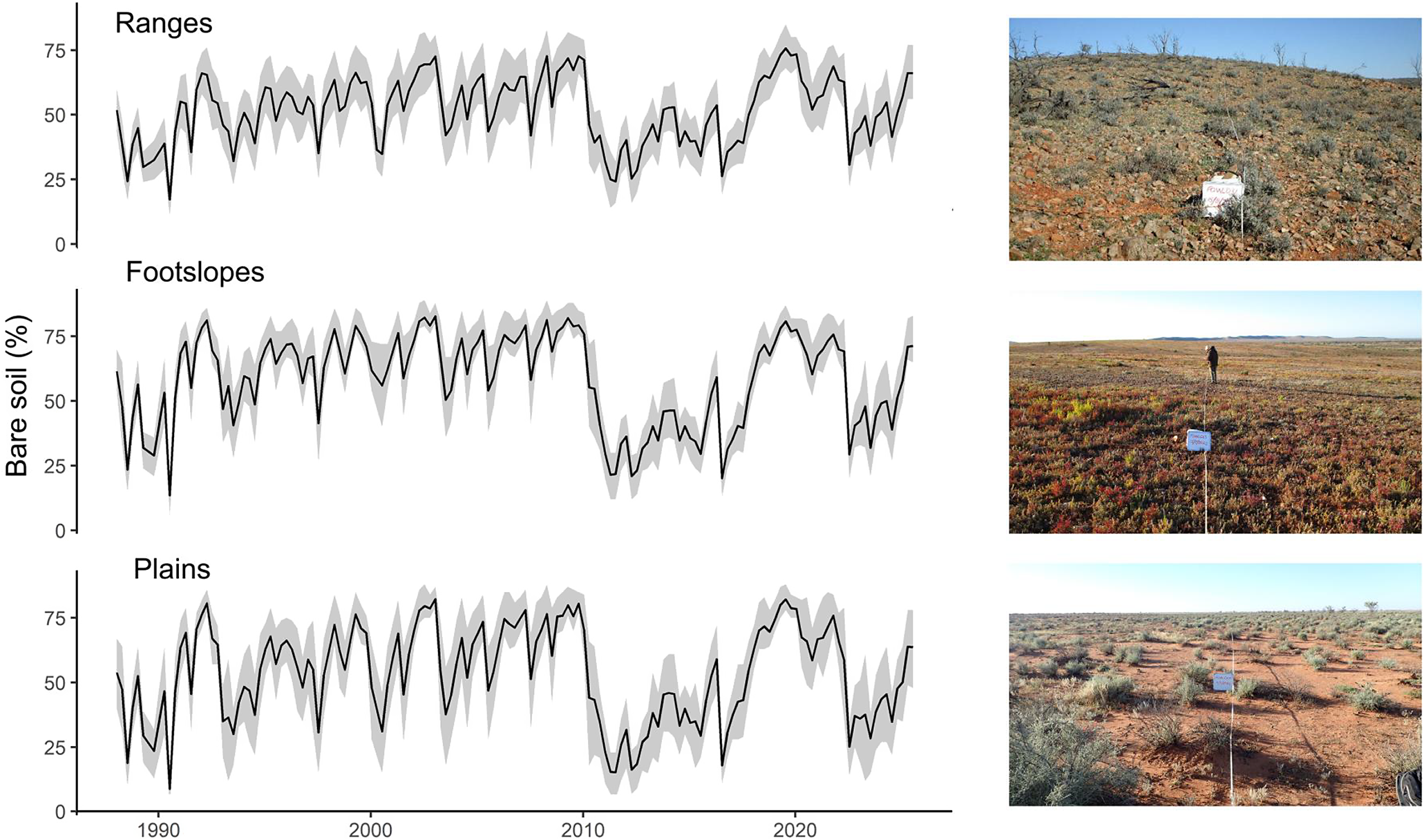

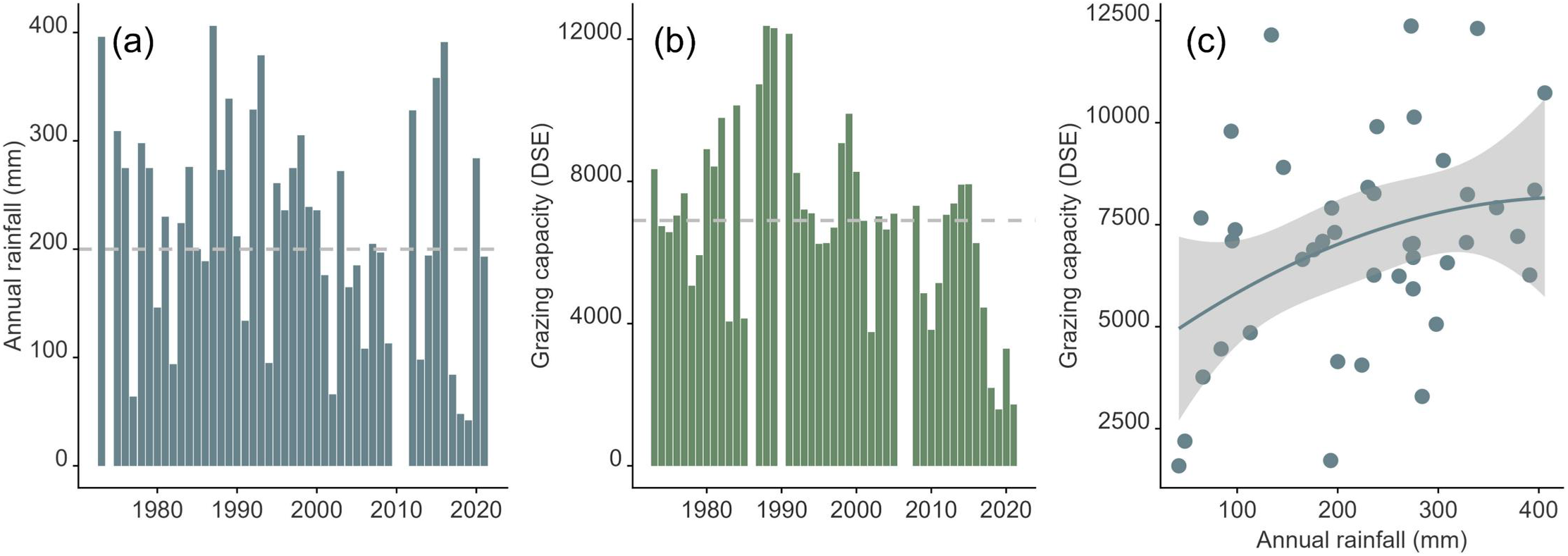

The percentage cover of bare soil changed markedly over the period of the study (Figure 3), particularly on the plains (Figure 3c), and this was closely related to rainfall (Figure 4a). For example, the cover of bare soil declined in 2011 with the marked increase in rainfall after a couple of very dry years, and vice versa for the period 2016–2020. Annual rainfall for Fowlers Gap was highly temporally variable, ranging from generally above-average between before 2000, to below-average rainfall in the second two decades (2000–2020). There were larger rainfall events in 2012, 2015 and 2016 (Figure 4a).

Figure 3. Temporal changes in the cover of bare soil (%) from 1985 to 2026 for ranges, footslopes and plains.

Figure 4. (a) Annual rainfall, (b) assessed grazing capacity, and (c) the relationship between grazing capacity and annual rainfall.

Examination of stocking records indicates average livestock numbers of 6,930 ± 2,583 (mean ± SD) dry sheep equivalents (Figure 4b) and a generally weak, though positive, relationship with increasing rainfall (R 2 = 0.12; Figure 4c). Long-term data on densities of residual herbivores (kangaroos and goats) indicated an average of 18.9 (± 6.0) grey and red kangaroos km−2 between 1990 and 2022 (based on aerial surveys by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service). About 27,000 feral goats were removed from Fowlers Gap between 2009 and 2022. The number of livestock run on the station overall increased steadily until 1985, after which marked declines were apparent (Figure 4d).

The resurvey of North Mandelman’s Paddock also revealed major declines in shrub density over the 40 years (Figure 5a), consistent with the station-wide survey described above (Figure 5b). Specifically, the density of shrubs in the family Chenopodiaceae (Maireana species, A. vesicaria) declined by 86% on cracking and scalding clays, and 64% on duplex soils, but there was no change on sandy soils (Figure 5a). Importantly, extensive stands of A. vesicaria recorded in 1986 were completely absent in 2025. The presence of dead shrubs and woody hummocks suggests their demise over the past decade. Consistent with the station-wide survey, the cover of eroded soil declined by an average of 15% over the 40 years for sands (5%), clays (14%) and duplex soils (26%), though the high variability between 2010 and 2020 is noteworthy (Figure 3).

Figure 5. (a) Mean + SD in shrub density for North Mandleman’s Paddock on clay, duplex and sandy soils in 1986 and 2025. Data for 1986 include Maireana spp. and Atriplex vesicaria. 2025 data are for Maireana spp. only. (b) Normalised changes in station-wide shrub density. Negative values indicate substantial reductions, in shrub density, and vice versa.

Vegetation changes between 1990 and 2022

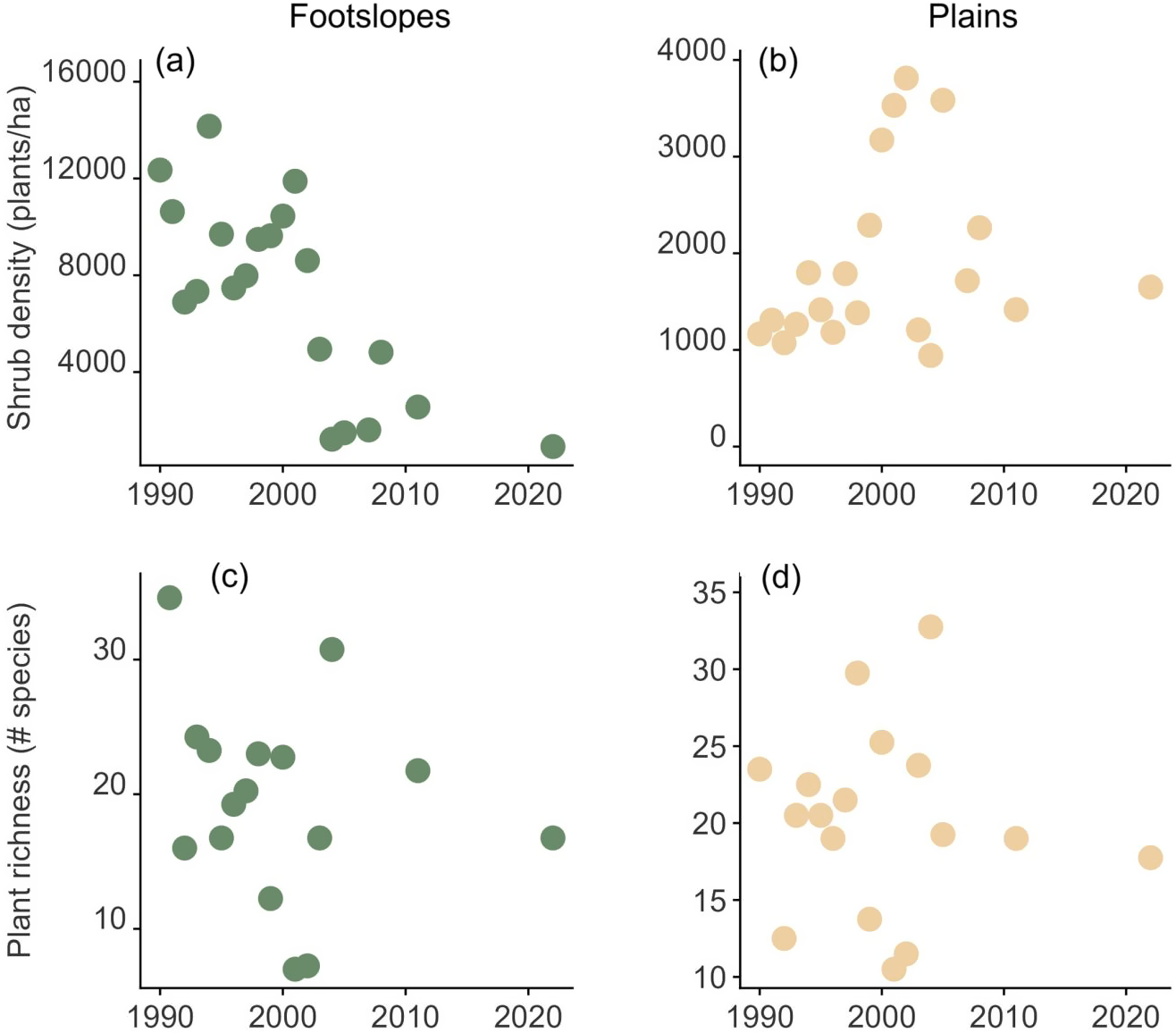

Using data from the RAP, we found marked declines in shrub density after about 2003 on the footslopes, and 2006 in the plains (Figure 6a and 6b). Plant richness showed marked fluctuations on both footslopes and plains (Figure 6c and 6d). There was a general, though non-significant trend of increasing plant richness with average annual rainfall at both sites (P > 0.05). We found a weak increase in plant richness with increasing shrub density (R 2 = 0.16), but only on the plains.

Figure 6. Changes in shrub density (a, b) and plant richness (c, d) at the Footslopes and Plains sites of the Rangeland Assessment Program.

Discussion

There were three major results of our study. First, livestock carrying capacity declined markedly (~15%) over the period, consistent with declines in rainfall and recent increases in the density of feral goats. Second, there were substantial reductions in both the cover and density of shrubs from the family Chenopodiaceae, indicating potential declines in habitat value and drought forage value for livestock. This was apparent at both the station level and the scale of an individual paddock. Finally, levels of erosion declined, consistent with improved land management at Fowlers Gap, where there has been a focus on smaller paddocks and more extensive watering points. Our study provides important insights into moderately long-term changes in rangeland attributes and reinforces the importance of using long-term rangeland data to assess environmental change as large areas of Earth move towards hotter and drier climates.

Marked declines in chenopod shrub density

Shrub cover declined markedly, particularly on the ranges, and for A. vesicaria, with strong reductions in cover and density. Shrubs are critically important components of rangeland ecosystems. They are known to form fertile islands in drylands (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Ding, Dorrough, Delgado-Baquerizo, Sala, Gross, le Bagousse-Pinguet, Mallen-Cooper, Saiz, Asensio, Ochoa, Gozalo, Guirado, García-Gómez, Valencia, Martínez-Valderrama, Plaza, Abedi, Ahmadian, Ahumada, Alcántara, Amghar, Azevedo, Ben Salem, Berdugo, Blaum, Boldgiv, Bowker, Bran, Bu, Canessa, Castillo-Monroy, Castro, Castro-Quezada, Cesarz, Chibani, Conceição, Darrouzet-Nardi, Davila, Deák, Díaz-Martínez, Donoso, Dougill, Durán, Eisenhauer, Ejtehadi, Espinosa, Fajardo, Farzam, Foronda, Franzese, Fraser, Gaitán, Geissler, Gonzalez, Gusman-Montalvan, Hernández, Hölzel, Hughes, Jadan, Jentsch, Ju, Kaseke, Köbel, Lehmann, Liancourt, Linstädter, Louw, Ma, Mabaso, Maggs-Kölling, Makhalanyane, Issa, Marais, McClaran, Mendoza, Mokoka, Mora, Moreno, Munson, Nunes, Oliva, Oñatibia, Osborne, Peter, Pierre, Pueyo, Emiliano Quiroga, Reed, Rey, Rey, Gómez, Rolo, Rillig, le Roux, Ruppert, Salah, Sebei, Sharkhuu, Stavi, Stephens, Teixido, Thomas, Tielbörger, Robles, Travers, Valkó, van den Brink, Velbert, von Heßberg, Wamiti, Wang, Wang, Wardle, Yahdjian, Zaady, Zhang, Zhou and Maestre2024), assembling critical resources such as water, sediment, seed, nutrients and organic matter beneath their canopies across different geomorphic contexts, that is, from ranges to alluvial plains (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Stewart, Sutton and Eldridge2024). Shrubs act as nurse plants for understorey protégé plant species (Soliveres et al., Reference Soliveres, Eldridge, Hemmings and Maestre2012) and a range of invertebrates and vertebrates (Shelef and Groner, Reference Shelef and Groner2011; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Zuliani, Goldgisser and Lortie2024). Shrubs are also critical for enhancing hydrological function and increasing soil carbon and nitrogen (Marquart et al., Reference Marquart, Eldridge, Geissler, Lobas and Blaum2020). A. vesicaria and Maireana spp., our main focal shrubs, are also important drought reserves for sheep (Graetz, Reference Graetz1976; Revell et al., Reference Revell, Norman, Vercoe, Phillips, Toovey, Bickell, Hulm, Hughes and Emms2013), depending on the salinity of sheep drinking water (Wilson, Reference Wilson1966). The loss or decline of a functional shrub community, therefore, represents a decline in habitat value, soil function, drought fodder reserve and ecosystem stability. At Fowlers Gap, this decline was strongest in the ranges where they comprise the main perennial structures due to the loss of other perennial woody plants, such as the tree A. aneura, through extensive tree removal to support the historic mining industry (Jones, Reference Jones2016). Goat browsing is focused on ranges, which are not preferred by sheep. It is likely, therefore, that grazing-induced loss of shrubs is due to goats, possibly exacerbated by a lack of summer rainfall.

Reinstatement of viable populations of A. vesicaria is likely to be difficult. The lack of summer rainfall has been shown to affect the germination and survival of A. vesicaria and Maireana spp. populations that require summer rainfall to recruit and establish juvenile plants (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Travers, Facelli, Facelli, Keith and Keith2017). A. vesicaria is also susceptible to grazing-induced disturbance, particularly during droughts (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Westoby and Stanley1990), where excessive defoliation prevents resprouting and leads to plant death (Leigh and Mulham, Reference Leigh and Mulham1971). Our observations at Fowlers Gap show that complete extirpation of A. vesicaria can be rapid. For example, Atriplex densities of >10,000 shrubs ha−1 were recorded in the footslopes during the RAP annual site visit in 2000, but by 2020, densities had crashed to around 1,500. By 2022, there was no evidence of any live A. vesicaria at the site. Previous studies have documented massive death of A. vesicaria at Fowlers Gap due to droughts, with only 30% regeneration (Westohy and Rice, Reference Westohy and Rice1979). We have no firm conclusion about when A. vesicaria disappeared from extensive areas in North Mandleman’s paddock, but it is likely to have been over the past decade, consistent with observations from other areas of the station.

The implications of substantial shrub decline are far-reaching as the station enters a new era as an experimental site designed to examine changes in soils and vegetation following the removal of all livestock in 2024. Studies are now underway to examine soil seedbanks of key species, such as A. vesicaria and A. aneura, and regeneration will likely require a combination of both engineering works and the reintroduction of viable seed. The station has a long history of restoration by the NSW Soil Conservation Service in the 1950s and 1960s, and more recently in the 1990s. Techniques tested included water ponding, ripping and pitting (Hannah, Reference Hannah1984), with best results at Fowlers Gap with contour furrowing (Wakelin-King, Reference Wakelin-King2011). Soil seedbanks in A. vesicaria are typically short-lived (Hunt, Reference Hunt2001) so that re-establishment in the absence of seed supplementation is likely to be protracted (Eldridge and Ding, Reference Eldridge and Ding2023). The lack of a viable soil seedbank will present huge obstacles to the successful reintroduction of A. vesicaria. Similarly, re-establishment of Maireana spp. is likely to be patchy, even with mechanical treatment (Haby, Reference Haby2017).

Long-term declines in erosion

Despite generally lower rainfall over the second two decades, the degree of erosion was substantially less in 2022 than in 1982. There are a number of potential explanations for this. First, a greater use of portable livestock watering troughs and flexible piping made from polyethylene has seen an increase in the number and distribution of livestock watering points since 1982, as the station sought to reduce grazing pressure around water (Macdonald, Reference Macdonald2000). In 1982, the NSW Soil Conservation Service estimated that 5.1% of the area of Fowlers Gap was unwatered, that is, further than 3 km from water, which is considered outside the watering range of sheep (Condon, Reference Condon and Stewart1968). There are now additional watering points on the eastern side of the station (Figure 1a and 1b). Second, the station has been consistently running sheep in smaller flocks. A combination of smaller flocks and more watering points has resulted in the reduction of large areas of scalding and clay pans, particularly on the plains. Finally, the level of erosion recorded in 1980 is likely a consequence of flow-on effects from early periods of degradation, much of which occurred around the margins of the creeks and alluvial fans (Walker, Reference Walker1991). The reductions in large-scale erosion observed during the last 40 years are consistent with observations elsewhere of regional declines in erosion, particularly large-scale declines across clay pans and other extensive rangeland areas (McKeon et al., Reference McKeon, Hall, Henry, Stone and Watson2004).

Conclusions

Our study reinforces the importance of long-term datasets to understand the nature of biotic and abiotic change in rangelands over relatively longer time periods. Australia’s rangelands occupy almost three-quarters of the terrestrial land area, yet we have relatively few long-term studies that can be used to track environmental change. Rangeland monitoring programmes, such as WARMS (Holm et al., Reference Holm, Burnside and Mitchell1987; Watson and Novelly, Reference Watson and Novelly2004; Novelly et al., Reference Novelly, Watson, Thomas and Duckett2008) and RAP (Eldridge and Koen, Reference Eldridge and Koen2003), and inventory programmes from the South Australian Pastoral Board have been substantially reduced in intensity or frequency or discontinued altogether, and few studies are running longer than 10 years, other than the Koonamore study in arid South Australia (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Specht and Eardley1964; Sinclair, Reference Sinclair2005) or those carried out by individual researchers. Information from studies such as this or similar (e.g., Lay and Lay, Reference Lay and Lay2025) represents an important repository of information that can be a useful tool to gauge changes in Australia’s rangelands against a backdrop of dramatic change.

Open peer review

For open peer review materials, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2026.10018.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request from the senior author. No artificial intelligence tools were used in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Science Faculty, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Author contribution

Conceptualization and writing of initial draft: D.J.E. Graphics and modification: A.F. and D.J.E. Review and editing: D.J.E. and A.F.

Financial support

This study was supported by the University of New South Wales.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear editors

We would be grateful if you would consider our manuscript, which describes a long-term changes in vegetation at a research Institute in eastern Australia over 40 years.

Our manuscript details the extensive decline in shrubs and the resulting decline in safe carrying capacity for livestock across a 40 year period.

Our manuscript, if selected by the journal, would be best placed in the Special Issue dedicated to the work of Walter Whitford. Doctor Whitford was a keen supporter of monitoring in rangelands, so it is appropriate that this manuscript forms part of the special issue.

I am happy to provide further information if required.

Sincerely

David Eldridge