1. Introduction

Code-switching (CS), defined as “the alternative use by bilinguals of two or more languages in the same conversation” (Milroy & Muysken, Reference Milroy and Muysken1995, p. 7), is a rule-governed phenomenon (e.g., Belazi et al., Reference Belazi, Rubin and Toribio1994; Di Sciullo et al., Reference Di Sciullo, Muysken and Singh1986; MacSwan, Reference MacSwan1999; Mahootian, Reference Mahootian1993; Myers-Scotton, Reference Myers-Scotton1993; Poplack, Reference Poplack1980; Sankoff & Poplack, Reference Sankoff and Poplack1981). This study investigates word-internal CS through the lens of Mandarin Chinese (henceforth Chinese)-English bilingualism. According to the classic free morpheme constraint (FMC) in (1) (Poplack, Reference Poplack1980; Sankoff & Poplack, Reference Sankoff and Poplack1981), word-internal CS – where a bound morpheme attaches to a lexical item from another language – is prohibited.

As illustrated in (2), Spanish-English mixed segments involving an English base eat and a Spanish inflectional suffix are unacceptable.Footnote 2

Although the FMC has received considerable support (e.g., Bentahila & Davies, Reference Bentahila and Davies1983; Berk-Seligson, Reference Berk-Seligson1986; Clyne, Reference Clyne1987; MacSwan, Reference MacSwan1997, Reference MacSwan1999, Reference MacSwan2000), numerous counterexamples have emerged (e.g., Alexiadou & Lohndal, Reference Alexiadou and Lohndal2018; Bokamba, Reference Bokamba1989; Chan, Reference Chan1999; Grimstad et al., Reference Grimstad, Riksem, Lohndal and Åfarli2018; Halmari, Reference Halmari1997; Hlavac, Reference Hlavac2003; Legendre & Schindler, Reference Legendre and Schindler2010; López et al., Reference López, Alexiadou and Veenstra2017; MacSwan, Reference MacSwan1999, Reference MacSwan2000; Myers-Scotton, Reference Myers-Scotton1993; Nartey, Reference Nartey1982; Redouane, Reference Redouane, Cohen, McAlister, Rolstad and MacSwan2005; Riksem, Reference Riksem2018). In particular, cases like (3) show that a switch between a base and a bound inflectional morpheme can be acceptable.

However, existing literature has largely focused on inflectional morphology, leaving derivational morphology relatively underexplored. This raises a key question: Do derivational morphemes also defy the FMC, or are such violations limited to inflectional morphology?

To address this, we examine instances of word-internal CS in which English words are combined with Chinese inflectional morphemes – le (perfective marker), zhe (progressive marker), and guo (experiential marker) – as well as derivational morphemes – zhe ‘-er,’ hua ‘-ize,’ and jia ‘-ist.’ Our findings reveal a striking asymmetry: English words readily combine with Chinese inflectional morphemes, but tend to resist derivational ones. To account for this asymmetry, we adopt MacSwan’s (Reference MacSwan, Bullock and Toribio2009) phonetic form (PF) interface condition (PFIC), applying it within our own weak lexicalist implementation of the minimalist framework. Specifically, we argue that CS is possible when morphological structure is assembled after spell-out, at PF, but disallowed when constructed before spell-out, in the lexicon or syntax. In this view, the FMC remains relevant for lexically or syntactically formed words, but not for PF-assembled structures. This conclusion both supports the PFIC – where every syntactic head must be phonologically parsed at spell-out – and provides a new perspective on so-called counterexamples to the FMC, treating them as part of a broader pattern rather than exceptions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews previous research and outlines the empirical scope of the study. Section 3 introduces the research questions, experimental design, and results. Section 4 presents MacSwan’s (Reference MacSwan, Bullock and Toribio2009) minimalist model and highlights points where its predictions diverge from the observed inflection–derivation asymmetry. Section 5 develops a lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation, demonstrating that, when reframed within this architecture, the PFIC can account for the asymmetry. Section 6 considers alternative accounts and assesses their limitations. Section 7 offers concluding remarks.

2. Gaps in the literature and motivation for empirical study

While much of the CS literature has examined the FMC, empirical investigations have concentrated primarily on inflectional morphology. Numerous studies have shown that switching between a lexical base and an inflectional morpheme – though traditionally deemed ungrammatical – can nonetheless be acceptable (e.g., Choi, Reference Choi1991; Grimstad et al., Reference Grimstad, Riksem, Lohndal and Åfarli2018; Halmari, Reference Halmari1997; Legendre & Schindler, Reference Legendre and Schindler2010; Myers-Scotton, Reference Myers-Scotton1993; Redouane, Reference Redouane, Cohen, McAlister, Rolstad and MacSwan2005). See example (3). This raises an important theoretical issue: If inflectional morphemes from one language can attach to bases from another, can derivational morphemes from the same language do so as well? Do they exhibit comparable patterns of acceptability, or are they subject to tighter constraints?

To explore this, we conducted an experimental study focusing on word-internal CS involving English words and Chinese bound morphemes. We specifically examined whether inflectional and derivational morphemes differ in their compatibility with English words and whether such differences align with existing grammatical constraints like the FMC.

3. Research questions and experimental design

We designed an acceptability judgment experiment targeting mixed words formed from English words and Chinese bound morphemes. Contributing to the growing body of experimental work on grammatical constraints in CS (e.g., González-Vilbazo et al., Reference González-Vilbazo, Bartlett, Downey, Ebert, Heil, Hoot and Ramos2013), the study aims to assess not only the acceptability of these forms, but also their implications for bilingual word formation.

Specifically, we ask:

-

a) Is there a systematic asymmetry between Chinese inflectional and derivational morphemes in their compatibility with English bases in word-internal CS?

-

b) If such an asymmetry exists, to what extent can the FMC account for it?

-

c) What might this potential contrast reveal about the grammatical architecture underlying bilingual word formation?

3.1. Participants

A total of 35 Chinese-English bilinguals, aged 18 to 34 (with one exception aged 60), participated in the study. All participants acquired Chinese by approximately age four. With one exception (a participant who began learning English at age 13 and lived in an English-speaking country for nine years), all acquired English before the end of the critical period. These age figures reflect the linguistic profiles of respondents, not recruitment criteria. All participants reported sustained, active exposure to Chinese and English.

Participants completed a bilingual proficiency self-assessment, rating their skills in listening, speaking, reading, and writing in both languages. While self-reports have limitations (Scholl et al., Reference Scholl, Fontes and Finger2021), they are widely used in bilingualism research (Brantmeier et al., Reference Brantmeier, Vanderplank and Strube2012; Li et al., Reference Li, Sepanski and Zhao2006, Reference Li, Zhang, Yu and Zhao2020; Marian et al., Reference Marian, Blumenfeld and Kaushanskaya2007), including CS studies (e.g., Besset, Reference Besset2017; Pérez-Leroux et al., Reference Pérez-Leroux, O’Rourke, Sunderman and MacSwan2014; Poplack, Reference Poplack1980). In total, 26 participants (74%) self-identified as fluent or very fluent in both languages across all modalities, while the remaining 9 reported high but slightly variable proficiency (e.g., lower literacy in written Chinese). No participant reported limited ability in either language. Based on these profiles, our sample represents a population of highly proficient bilinguals, aligning with the “ideal code-switcher” profile described in Toribio (Reference Toribio2001, p. 215) (see also Aguirre, Reference Aguirre1985; Poplack, Reference Poplack1980; Zentella, Reference Zentella1997): “a balanced adult bilingual” with “native-like abilities” in both languages. Adopting this position, we maintain that speakers with high bilingual proficiency are best suited for investigating grammatical constraints on CS. As demonstrated in previous research (e.g., MacSwan, Reference MacSwan2000; Muysken, Reference Muysken2000; Toribio, Reference Toribio2001), such speakers tend to exhibit more systematic CS behavior and greater sensitivity to grammatical constraints. Accordingly, we consider our participant sample appropriate and reliable for studying structural properties of bilingual CS. This study complies with the ethical standards of relevant institutional committees and the Helsinki Declaration (1975, rev. 2008).

To assess participants’ attitudes toward Chinese-English CS, we included two Likert-scale items and one open-ended questionFootnote 3 as part of a broader post-task background survey (see Section 3.3 for details). Results indicated that most participants viewed CS as both common and natural in their sociolinguistic environment. Open-ended comments largely supported this view, characterizing CS as a pragmatic and contextually appropriate communicative strategy. A few remarked that CS might come across as “affected” when overused for stylistic purposes – such as to appear cosmopolitan. Nevertheless, they still regarded it as a valid and useful linguistic resource. To ensure that acceptability judgments were based on linguistic intuition rather than social attitudes, we excluded three individuals who expressed strongly negative views from the final analysis.

3.2 Experimental materials

All Chinese content throughout the experiment – including test stimuli, task instructions, and the background survey – was presented in Chinese characters (not Pinyin or romanized forms), to reflect native reading conventions and avoid orthographic interference. The judgment task consisted of 30 sentences: 14 test items, 8 control sentences, and 8 supplementary CS sentences. The test items target two categories of Chinese morphemes: (i) aspectual inflectional morphemes (e.g., -le ‘perfective,’ -zhe ‘durative,’ -guo ‘experiential’) and (ii) derivational morphemes (e.g., -zhe ‘-er,’ -hua ‘-ize,’ -jia ‘-ist’). Aspectual morphemes in Chinese are inflectional elements that combine with the verb base to form a single verb, indicating whether an action is completed (-le), ongoing (-zhe), or previously experienced (-guo) (Dai, Reference Dai1992; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Li and Li2009; Packard, Reference Packard2000).

By contrast, derivational morphemes, including -zhe ‘-er,’ -hua ‘-ize,’ and -jia ‘-ist,’ serve word-forming functions (Li & Thompson, Reference Li and Thompson1981; Packard, Reference Packard2000). The suffix -zhe ‘-er’ attaches to verbs or adjectives to form nouns that denote agents or individuals engaged in an action or possessing a particular quality (e.g., yanjiu-zhe ‘researcher’).Footnote 4 -Hua ‘-ize’ transforms adjectives or nouns into verbs (e.g., xiandai-hua ‘modernize’). -Jia ‘-ist’ derives nouns referring to experts or professionals in a given field (e.g., kexue-jia ‘scientist’). These morphemes correspond functionally to English derivational affixes -er, -ize, and -ist, respectively.

Based on these three inflectional and three derivational morphemes, a total of 14 test sentences were constructed: (4) shows combinations of Chinese inflectional morphemes with English verbs, while (5) illustrates combinations of Chinese derivational morphemes with English words.

In addition to the test items, eight control CS sentences were included as baseline stimuli. These were drawn or adapted from naturally occurring data reported in previous corpus-based studies (Guo, Reference Guo2006, Reference Guo2007; Wei, Reference Wei, Cohen, McAlister, Rolstad and MacSwan2005), illustrated in (6). Incorporating attested examples as control items helps ground participants’ acceptability judgments in empirically validated linguistic patterns, thereby enhancing the validity of the task.

To increase syntactic diversity and avoid overexposing participants to a single structure type, we included eight supplementary CS sentences. These items were designed to balance the stimulus set and promote more nuanced acceptability judgments. Drawing on proposed universal constraints, they featured configurations predicted to be ungrammatical. For instance, (7a–c) involve switches to closed-class elements (e.g., possessive ’s, pronouns they, you), violating Joshi’s (Reference Joshi, Dowty, Karttunen and Zwicky1985) closed-class constraint (CCC) in (8). Example (7d) contains an English verb within a Chinese V-V compound, a structure argued to be universally disallowed (MacSwan, Reference MacSwan1999, p. 221). As shown in the next subsection, these items received low acceptability ratings, in line with theoretical predictions.

3.3 Procedure

The experiment was conducted in a quiet room using a paper-based, written format, consisting of two parts: a sentence judgment task followed by a bilingual background survey. The entire session lasted approximately 15–20 minutes. All experimental stimuli were presented exclusively in written form, with no auditory input. This design follows a well-established tradition in CS research, particularly in grammaticality judgment tasks, where orthographic input is typically used without spoken stimuli (Bartlett & González-Vilbazo, Reference Bartlett and González-Vilbazo2013; Liceras et al., Reference Liceras, Fuertes, Perales, Pérez-Tattam and Spradlin2008; Pérez-Leroux et al., Reference Pérez-Leroux, O’Rourke, Sunderman and MacSwan2014; Stadthagen-González et al., Reference Stadthagen-González, Parafita Couto, Párraga and Damian2019; Toribio, Reference Toribio2001).Footnote 5 To minimize potential order effects, all items were randomized and distributed across six questionnaire versions, with each participant randomly assigned to one version.

The questionnaire began with an instruction section, and participants were given an oral walkthrough of this section before the experiment started. They were asked to evaluate each sentence individually, without skipping or returning to previous items. Sentence acceptability was rated on a four-point Likert scale,Footnote 6 adapted from Kitagawa and Yoshida (Reference Kitagawa, Yoshida and Eom2009), with the following options presented in Chinese: (A) keyi jieshou ‘acceptable,’ (B) shang ke jieshou ‘marginally acceptable,’ (C) bu tai zhengque ‘somewhat unacceptable,’ and (D) bu neng jieshou ‘unacceptable.’ To ensure consistent interpretation of these scale points, the instructions included bilingual explanatory descriptions.Footnote 7 In addition, participants were shown four illustrative examples before beginning the task: two that would typically fall under ‘acceptable’ or ‘marginally acceptable’ (see (9)) and two that would be judged as ‘somewhat unacceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’ judgments (see (10)).Footnote 8

After completing the judgment task, participants filled out a bilingual background questionnaire documenting their demographic and linguistic profile, including age, place of birth, gender, age of language acquisition, parental language input, education languages, self-rated proficiency, language dominance, social network composition, and language attitudes. Some items used a mixed Chinese-English format, reflecting participants’ bilingual competence.

Responses on the Likert scale were numerically coded from 4 (most acceptable) to 1 (least acceptable) for statistical analysis. Background data were used to assess participant eligibility and to contextualize their judgment patterns.

3.4 Results and discussion

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team, 2009) and RStudio (RStudio Team, 2012). Prior to presenting the results from the ordinal mixed-effects regression, we first report descriptive statistics to illustrate overall patterns of acceptability across sentence types.

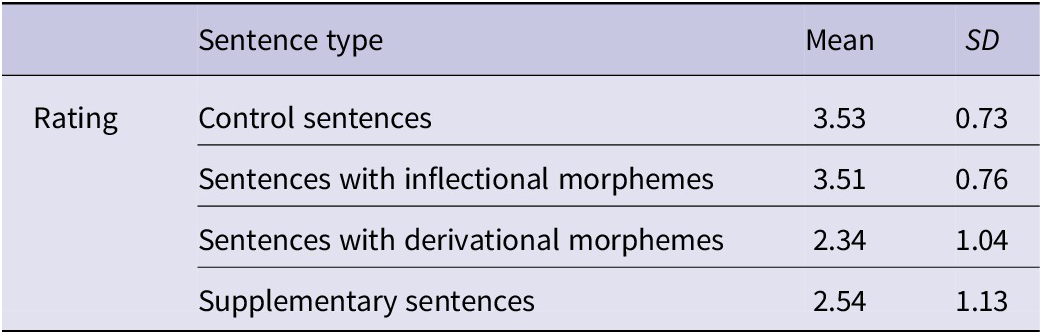

As shown in Table 1, control sentences received the highest mean rating (M = 3.53, SD = 0.73), indicating strong acceptability. Sentences containing inflectional morphemes were rated similarly (M = 3.51, SD = 0.76), suggesting no meaningful difference in perceived acceptability. In contrast, sentences with derivational morphemes received substantially lower ratings (M = 2.34, SD = 1.04), reflecting a marked decline in acceptability. Supplementary CS sentences also showed reduced ratings (M = 2.54, SD = 1.13), consistent with their more structurally marked or theoretically dispreferred status. While these items are not central to the study’s main research question, their low ratings align with prior theoretical accounts (e.g., Joshi, Reference Joshi, Dowty, Karttunen and Zwicky1985; MacSwan, Reference MacSwan1999) concerning constraints on acceptable CS configurations.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of mean ratings and standard deviations

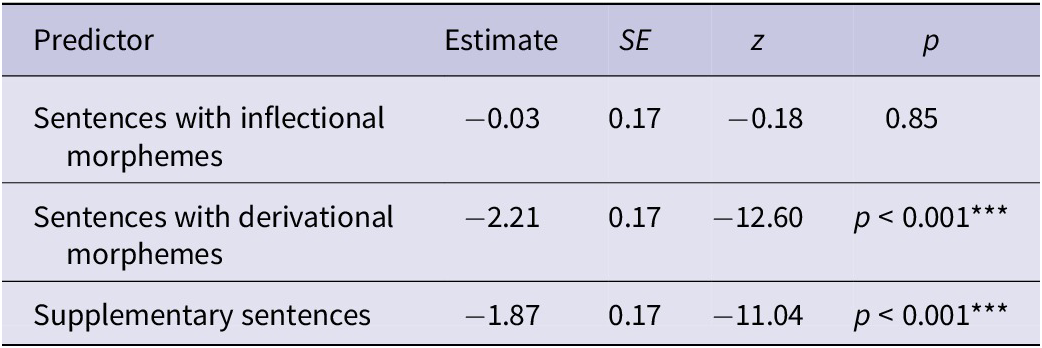

These patterns were statistically confirmed through an ordinal mixed-effects regression analysis,Footnote 9 with sentence type as a fixed effect, and participant and item as random effects. Control sentences served as the reference category.

As shown in Table 2, sentences containing inflectional morphemes did not differ significantly from controls (estimate = −0.03, p = 0.85), in line with their nearly identical mean ratings. In contrast, derivational morpheme sentences were rated significantly lower (estimate = −2.21, p < 0.001), confirming the substantial negative effect observed descriptively. Supplementary CS sentences also received significantly lower ratings (estimate = −1.87, p < 0.001), corroborating their limited acceptability.

Table 2. Summary of ordinal regression model coefficients

Overall, these findings indicate a clear asymmetry between inflectional and derivational morphology in CS contexts. Inflectional morphemes are rated as acceptable but pose a challenge to the FMC, whereas derivational morphemes lead to a robust and statistically significant decline in acceptability judgments,Footnote 10 as predicted by the constraint. This discrepancy between empirical judgments and theoretical expectations highlights the need to reassess how current models of bilingual morphosyntax account for such asymmetries. To that end, we now turn to MacSwan’s minimalist model of CS and examine whether its core assumptions, including the PFIC, can adequately account for the observed patterns.

4. MacSwan’s minimalist model and its limits

One of the most influential generative accounts of CS is MacSwan’s minimalist framework (Reference MacSwan1997, Reference MacSwan1999, Reference MacSwan2000, Reference MacSwan2005, Reference MacSwan, Bullock and Toribio2009), which integrates Chomsky’s (Reference Chomsky1995) minimalist program into the analysis of bilingual grammar. This model seeks to explain CS phenomena using the general architecture of syntactic theory, without appealing to CS-specific mechanisms.

The inflection–derivation asymmetry observed in word-internal CS, however, calls for a closer examination of how the minimalist approach handles such morphosyntactic configurations. As will be discussed, MacSwan’s account, while theoretically elegant, does not fully capture the specific pattern identified in our data – namely the differential acceptability of inflectional and derivational morphology.

MacSwan adopts the standard minimalist architecture of the language faculty, which posits a computational system for human language composed of three fundamental syntactic operations: Select, Merge, and Move. Select draws lexical items from the lexicon to form numeration. Merge then combines these items into hierarchical syntactic objects, and Move applies to the output of Merge to generate further syntactic structures. Crucially, these operations must ensure that all lexically encoded features are properly matched throughout the derivation. At a certain stage, the spell-out operation transfers the derived structure to two interface levels: logical form (LF), where interpretive (covert) operations occur, and PF, where phonological operations are executed. A derivation is well-formed – or said to converge – only if it satisfies the condition of full interpretation (FI) at both interfaces.

Within this framework, MacSwan endorses the FMC as a descriptively accurate generalization but reformulates it as follows:

This restriction, he argues, stems from the architecture of the phonological component. Drawing on Chomsky’s (Reference Chomsky1995) claim that all X⁰ elements are direct inputs to PF, MacSwan contends that bilinguals maintain separate phonological systems for each language in order to avoid ranking paradoxes. Consequently, switching is permitted between syntactic heads (X⁰) but not within them, since each head must be phonologically parsed at spell-out and mapped to PF in a single derivational step.

To formalize this view, MacSwan introduces the PFIC:

The PFIC accounts for both the ill-formed classic FMC paradigms in (2) and CS involving complex words, as illustrated in (13). In cases like (2), switching occurs within a single syntactic head – a configuration schematized in (14a) – and is therefore banned. Likewise, the complex forms in (13) also involve single-head domains: had visto in (13a) is derived via reanalysis, and the clitic–verb sequence in (13b) results from head movement. Both cases correspond structurally to (14b), which schematically represents the single-head configurations that give rise to the ungrammaticality of (13a) and (13b).

(MacSwan, Reference MacSwan, Bullock and Toribio2009, p. 329, example (35))

In both structures in (14), CS below X⁰ is ruled out by the PFIC, as it would require switching phonological systems within a word, an operation incompatible with the requirement that each X⁰ be uniformly parsed at PF.

While the PFIC has been shown to account for certain types of word-internal CS behaviors reported in the literature, its application to the inflection–derivation asymmetry observed in our Chinese-English bilingual data is less straightforward. MacSwan’s minimalist framework, grounded in pre-syntactic lexicalism (e.g., 2009), assumes that both inflectional and derivational morphology are assembled in the lexicon before entering syntax. The PFIC, as formulated, requires that all syntactic heads be phonologically well formed at spell-out. Under these assumptions, morpheme–base combinations involving either inflectional or derivational morphology should be uniformly banned – contrary to our empirical findings. This discrepancy highlights the need for a revised model that distinguishes between types of morphological operations.

5. Explaining the inflection–derivation asymmetry in CS

To address this problem, we propose an alternative account that retains the core insight of the PFIC but adopts a lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation, in which morphologically complex words may be assembled at PF rather than exclusively in the lexicon. This shift explains the observed asymmetry: inflectional morphemes, which can attach post-syntactically, do not violate the PFIC, whereas derivational morphemes, which must be lexically assembled with their bases, render intra-word switching ungrammatical.

The remainder of this section develops the proposal in three parts. Section 5.1 outlines the theoretical foundation for a lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation, situating our proposal in relation to MacSwan’s pre-syntactic approach. Section 5.2 applies this model to intra-word CS between Chinese and English. Section 5.3 extends the account to additional domains, including cross-linguistic patterns in Urban Wolof and predictions for compounding.

5.1 Developing a lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation

In traditional generative frameworks, pre-syntactic lexicalist models posit that both inflectional and derivational morphology are assembled entirely in the lexicon before entering syntax (Halle, Reference Halle1973; Lapointe, Reference Lapointe1980; Lieber, Reference Lieber1980; Williams, Reference Williams1981). The outputs of these processes – fully formed words – are treated as atomic X⁰ elements in the syntactic derivation.

In contrast, we adopt a lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation, where inflectional morphology may be introduced in the syntax (via V-to-T movement or T-lowering), realized post-syntactically at PF through operations such as PF merger, or derived in the lexicon. This architecture has been articulated in both foundational work (e.g., Anderson, Reference Anderson1982; Aronoff, Reference Aronoff1976; Bobaljik, Reference Bobaljik, Harley and Phillips1994; Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1957; Emonds, Reference Emonds1978; Halle & Marantz, Reference Halle, Marantz, Hale and Keyser1993; Pollock, Reference Pollock1989) and more recent studies (e.g., Baker, Reference Baker2003; Bošković, Reference Bošković2014; Harley, Reference Harley, Cheng and Corver2013; Harwood, Reference Harwood2014; Lasnik, Reference Lasnik, Campos and Kempchinsky1995, Reference Lasnik2003).

Support for post-syntactic affixation comes from VP ellipsis diagnostics. In English, tense affixes surface post-syntactically, as seen in Lasnik (Reference Lasnik, Campos and Kempchinsky1995, Reference Lasnik2003):

In both (15a) and (15b), VP ellipsis in the second conjunct applies before inflection attaches to the verb in the first conjunct, showing that tense morphology is not part of the verb at the point where ellipsis takes place and instead attaches post-syntactically at PF.

A parallel distinction can be observed in Chinese, where we argue inflectional and derivational morphemes attach to their bases at different grammatical levels. Aspectual morphemes such as -guo ‘experiential’ and -le ‘perfective’ exhibit post-syntactic behavior similar to English tense affixes, while derivational morphemes like -hua ‘-ize’ and -zhe ‘-er’ must be formed lexically with their bases before entering the syntax, supported by the empirical diagnostic of VP ellipsis.

Focusing first on Chinese aspectual morphemes, such as -guo ‘experiential’ and -le ‘perfective,’ we follow Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Li and Li2009) in assuming that aspect heads (Asp⁰) project above vP. They argue that the surface verb–aspect cluster cannot be derived by movement of the verb to Asp, as this would yield incorrect word order. Previous analyses of these morphemes include Dai (Reference Dai1992), who assumes a pre-syntactic lexicalist view, and Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Li and Li2009), who consider both pre- and post-syntactic possibilities.Footnote 12 We adopt the post-syntactic affixation view, aligning Chinese aspectual morphology with English inflectional affixes. In what follows, we demonstrate Chinese patterns with English in permitting VP ellipsis, thereby allowing comparable diagnostics for post-syntactic affixation.

Merchant (Reference Merchant, Cheng and Corver2013) shows that in English, A’-extraction from VP ellipsis sites is grammatical (16a), whereas similar extraction from non-ellipsis contexts yields ungrammaticality (16b). This contrast is taken as evidence for the presence of a genuine ellipsis site:

A similar pattern is observed in Chinese (17),Footnote 13 where A’-movement from ellipsis sites is permitted, indicating that Chinese licenses VP ellipsis:

Having shown that VP ellipsis exists in Chinese, we now consider aspectual verbs such as ku-guo ‘cry-ASP’ in (18a). The compatibility of such surface forms with VP ellipsis indicates that the verb and aspectual morpheme do not constitute a morphologically unified unit prior to PF. Rather, as represented in the PF derivation in (18b), the aspectual morpheme attaches post-syntactically – mirroring the behavior of English tense affixes in (15).

These patterns parallel Lasnik’s (Reference Lasnik, Campos and Kempchinsky1995, Reference Lasnik2003) observations for English tense morphology and support the view that Chinese aspectual affixes are likewise attached post-syntactically.Footnote 14

This analysis can be made explicit using the AspP structure proposed in Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Li and Li2009, p. 102), with -guo occupying Asp. The derivation of ku-guo ‘cry-ASP’ in (19a) is shown in (19b–c). In overt syntax, the verb raises to v (19b). At PF, the aspectual affix lowers from Asp to v and attaches to the verb (19c).

In contrast to aspectual morphemes, derivational morphemes in Chinese, such as -hua ‘-ize’ and -zhe ‘-er,’ attach in the lexicon, forming morphological words with their bases. As such, they are not subject to PF operations like ellipsis. Consider ziyou-hua ‘free-ize, liberalize’ derived from the base ziyou ‘free’ and the suffix -hua ‘-ize.’ As shown in (20), ziyou-hua denotes the liberalization of policies or systems – not individuals. While ziyou ‘free’ can appear independently (20a), it cannot be separated from -hua ‘-ize’ by VP ellipsis (20b). If the two morphemes were independent at PF, ellipsis should be possible, as with aspectual morphology; see (18a). The ungrammaticality of (20b) reflects a semantic mismatch: renmin ‘people’ cannot plausibly undergo liberalization. In contrast, huobi liutong ‘currency circulation’ in (20c) yields an acceptable reading, as it denotes a valid target of policy reform.

The contrast between (20b) and (20c) shows that -hua ‘-ize’ cannot be stranded, indicating that ziyou-hua ‘free-ize’ is a preassembled unit. This contrasts with ku-guo ‘cry-ASP,’ where the verb and aspectual morpheme remain separate prior to PF.

These facts support the view that derivational affixes in Chinese are lexically assembled, like their English counterparts. For example, du-zhe ‘reader’ is derived from a verb and the agentive suffix -zhe ‘-er,’ parallel to English reader. Under Aronoff’s (Reference Aronoff1976, p. 50) lexicalist framework, such forms can be represented as:

Alternatively, Packard’s (Reference Packard2000, p. 176) X-bar-based model, building on Selkirk (Reference Selkirk1982), analyzes derivational affixes as morphological heads (Xʷ) within a hierarchical word-internal structure, where X-0 represents a full word. For example, hong-hua ‘red-ize, redden’ is structured as:

Both accounts converge on the view that derivational morphology yields morphologically complete X⁰ elements prior to syntax. We take the VP ellipsis asymmetry between inflectional and derivational morphology to confirm that derivational morphemes attach in the lexicon, whereas aspectual morphemes are post-syntactic.

This grammatical distinction supports a lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation, where lexical items – whether full words or affixes – are selected into the numeration. This stands in contrast to MacSwan’s pre-syntactic lexicalist model, which assumes that syntactic heads (X⁰) enter the derivation only as fully formed words. By contrast, we propose a more flexible view, where X⁰s are not restricted to complete words. As shown in (23), an X⁰ may consist of a single word or affix (23a), or it may involve a complex structure that incorporates, or is reanalyzed with, another head (e.g., Y0) (23b).

By allowing affixes to function as syntactic heads, we preserve the insight of the PFIC while broadening the range of structures that it can account for.

In sum, we have argued that inflectional and derivational morphemes attach at different grammatical levels in Chinese and that this distinction requires a flexible view of what may count as a syntactic head. This revised architecture sets the stage for our analysis in Section 5.2, where we show how the interaction of the PFIC with this updated view of X⁰ explains the observed asymmetry in intra-word CS.

5.2 Accounting for the inflection–derivation asymmetry under a lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation

Building on the discussion in Section 5.1, we now apply our lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation to the asymmetry observed in word-internal CS between inflectional and derivational morphology. As shown in Section 3.4, our experimental results reveal a robust pattern: mixed words combining a Chinese inflectional morpheme with an English verb, such as email-guo ‘email-ASP,’ were generally accepted, whereas combinations involving a Chinese derivational morpheme and English base material, such as modern-hua ‘modern-ize,’ consistently received low acceptability ratings. We argue that this asymmetry can be accounted for by the PFIC, provided that inflectional morphemes are treated as syntactically independent heads, while derivational morphemes are introduced as part of lexically preassembled words.

Under the lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation outlined in Section 5.1, inflectional morphemes such as experiential aspect marker -guo can enter the derivation as independent syntactic heads. In email-guo ‘email-ASP,’ the English verb email raises to v in overt syntax (24a), while the aspectual affix -guo lowers from Asp to v at PF, where it attaches to the English verb (24b). This derivation complies with the PFIC, which requires that “every syntactic head be phonologically parsed at Spell-Out” (MacSwan, Reference MacSwan, Bullock and Toribio2009, p. 331): since both email and -guo remain distinct heads at spell-out, each is parsed within its own phonological system, thereby permitting switching between them.

Crucially, the attachment in (24b) occurs at PF. If -guo were to combine with the English verb in the syntax – through head movement or overt affixation – the resulting head would span two phonological systems at spell-out, thereby violating the PFIC. Locating inflectional attachment in the post-syntactic component ensures that morphemes remain phonologically independent at spell-out and can be parsed separately at the interface.

By contrast, when a Chinese derivational morpheme combines with an English base, as in modern-hua ‘modern-ize,’ the resulting structure (25) under Packard’s X-bar-based approach is assembled in the lexicon and enters the syntax as a morphologically complete X⁰, representing one implementation of the lexicalist framework (cf. Aronoff, Reference Aronoff1976).

According to the PFIC, such X⁰s must be phonologically parsed as unified elements in a single language. Since modern-hua ‘modern-ize’ straddles two phonological systems, the structure violates the PFIC and is ruled out.

This distinction between post-syntactic and pre-syntactic (lexical) attachment offers a principled explanation for the observed asymmetry: email-guo ‘email-ASP’ is well-formed because each morpheme is parsed independently at spell-out, whereas modern-hua ‘modern-ize’ is predicted to be ill-formed at the interface, as it constitutes a mixed-language head before spell-out.

In short, word-internal CS appears to be permitted only when the morphemes involved enter the derivation as separate syntactic heads and are parsed independently at PF. In contrast, when morphemes are preassembled in the lexicon prior to syntax – as is typically the case with derivational morphology – CS across their boundary is disfavored or ruled out under current interface conditions. This analysis retains the core insight of the PFIC without altering its theoretical content. Rather, it builds on a revised understanding of what constitutes a syntactic head, as motivated by the lexicalist model that permits post-syntactic affixation developed in Section 5.1.

This revised architecture clarifies how the grammar constrains cross-linguistic morpheme combinations. The asymmetry observed in word-internal CS is not accidental but results from the distribution of morphology across components and its interaction with the PFIC. This way, the PFIC functions as an interface condition on bilingual word formation, whose effects depend on how the timing and status of morpheme attachment are specified.

5.3 Word-internal CS beyond Chinese-English: cross-linguistic evidence and compounding predictions

The analysis presented here reframes the application of the PFIC, permitting word-internal CS under a lexicalist model that allows for post-syntactic affixation. On this account, the PFIC functions as an interface condition on the mapping from syntax to phonology and does not preclude intra-word switching, provided that the relevant morphemes are not combined prior to spell-out. This way, PF is recognized as a legitimate site for assembling morphologically complex forms that span language boundaries.

Our proposal shares partial ground with Bandi-Rao and den Dikken (Reference Bandi-Rao, den Dikken and MacSwan2014, p. 170), who acknowledge that CS may occur in phonologically complex words. However, they explicitly maintain that such switching is only permitted when the morphemes involved do not belong to the same morphosyntactic head (X⁰). Even if the word is assembled post-syntactically, they uphold a categorical ban on intra-X⁰ CS. In contrast, we argue that this restriction applies only to structures assembled before spell-out. If a complex X⁰ or phonological word is formed post-syntactically, word-internal CS is not only possible but also predicted. Such post-syntactically assembled structures may span language boundaries and still be licit. This perspective offers a principled reinterpretation of empirical patterns previously seen as violations of the FMC or the PFIC (see Section 1).

Additional empirical support comes from Urban Wolof, where French verb bases combine with Wolof inflectional morphology – such as tense, agreement, or negation – producing mixed forms like monter-woon-naa “I set it up” (Legendre & Schindler, Reference Legendre and Schindler2010).

Legendre and Schindler (Reference Legendre and Schindler2010) argue that these affixes operate at the word rather than the phrasal level and should, in principle, fall under the jurisdiction of the PFIC. However, they present empirical evidence that appears to challenge the PFIC: the French verb base can trigger ATR vowel harmony in the Wolof suffix. This cross-linguistic phonological interaction suggests, in their view, that the PFIC may be too restrictive.

We adopt a different view, following Zribi-Hertz and Diagne (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Diagne2002), who argue that such verb complexes are assembled post-syntactically at PF, via head movement (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1999) or cliticization (Klavans, Reference Klavans1985). On this analysis, the morphemes are not combined in the lexicon or syntax, but at PF.Footnote 15 The Wolof suffix and the French verb base can thus be parsed as a phonological word at spell-out. Vowel harmony and other phonological interactions are therefore expected consequences of PF-level formation and do not violate the PFIC under our proposal.

This post-syntactic view of word formation also bears on the status of compound words.Footnote 16 Traditionally, compounds have been viewed as products of lexical word formation (e.g., Di Sciullo & Williams, Reference Di Sciullo and Williams1987; Meibauer, Reference Meibauer2007). However, more recent work has proposed that compounding may also occur outside the lexicon, either in syntax (Delfitto & Melloni, Reference Delfitto and Melloni2009) or post-syntactically (Lieber & Scalise, Reference Lieber and Scalise2006). Under our proposal, this variation in derivational timing predicts divergent behavior with respect to internal CS within compounds. Compounds formed before spell-out – whether in the lexicon or in syntax – are expected to resist internal switching, whereas those constructed post-syntactically at PF may be parsed as phonological words and could potentially permit switching between their internal constituents. This distinction supports a testable typology of bilingual compounds and illustrates how our approach extends to other word-level domains beyond inflectional and derivational morphology.

6. Alternative accounts and their limitations

While our analysis brings to light the asymmetry between mixed forms like email-guo ‘email-ASP’ and modern-hua ‘modern-ize,’ it is worth exploring whether alternative accounts could offer equally compelling explanations. This section evaluates two such proposals: the borrowing approach and the block-transfer hypothesis (BTH) put forward by López et al. (Reference López, Alexiadou and Veenstra2017). We argue that neither adequately accounts for the empirical patterns observed in our data or the broader typology of bilingual word formation.

6.1 Limitations of the borrowing approach

A central challenge in bilingual research is to distinguish between borrowing and CS. While surface forms may appear similar, borrowed elements are typically fully integrated into the recipient language’s phonological and morphosyntactic systems (MacSwan, Reference MacSwan2000; Sankoff et al., Reference Sankoff, Poplack and Vanniarajan1990). In contrast, code-switched elements retain structural properties from the source language (MacSwan, Reference MacSwan2000; for a related perspective, see Bhatt, Reference Bhatt1997). Despite certain areas of overlap, borrowing and CS represent fundamentally distinct linguistic processes (MacSwan, Reference MacSwan2000; Muysken, Reference Muysken2000; González-Vilbazo & López, Reference González-Vilbazo and López2011).

A borrowing-based account might interpret the English-origin elements in our mixed words as borrowings, akin to parqueando in Spanish-English bilingualism, where park is fully adapted to Spanish phonology and morphology (MacSwan, Reference MacSwan2000, p. 46). However, our empirical and structural findings challenge such a characterization.

First, our experimental results reveal a consistent asymmetry: Chinese aspectual morphemes readily combine with English verbs, while derivational morphemes are significantly less acceptable in comparable contexts. A pure borrowing account would predict full morphological integration – that is, the productive availability of both inflectional and derivational morphology. If English bases can combine seamlessly with Chinese inflectional morphemes, it is unclear why combinations with derivational morphology are dispreferred. The observed restriction – inflection being allowed, derivation being dispreferred – raises questions for the borrowing approach, which would need to explain why only inflectional morphology is readily permitted. By contrast, an account grounded in the PFIC offers a principled explanation for this asymmetry, deriving it from interface conditions that govern the mapping from syntax to phonology.

Second, syntactic patterns further challenge the borrowing-based analysis. In constructions such as email-guo ta ‘emailed him’ in (4f), the verb email selects a recipient without an overt theme – an argument structure permissible in English (27a) but not in Chinese (27b). As illustrated in (27c), Chinese transfer verbs like ji ‘mail’ obligatorily require both recipient and theme arguments. This cross-linguistic divergence in argument realization supports the view that email in (4f) retains its English syntactic properties rather than having been reanalyzed as a Chinese verb.

Third, phonological evidence further supports the view that the English-origin verbs in these mixed forms are not borrowings. For example, the verb email retains the final [l], a coda segment disallowed in native Mandarin phonology. Borrowed items typically undergo adaptation to conform to the recipient language’s phonotactic constraints (e.g., Seoul → shou-er), yet no such adaptation is observed here. This persistence of English phonology suggests that the embedded verb retains its source-language structure – consistent with CS, but not with borrowing.

Taken together, the morphological, syntactic, and phonological properties of our mixed forms reveal asymmetries that the borrowing hypothesis cannot adequately explain. These forms exhibit partial integration inconsistent with the profile of fully assimilated borrowings and instead reflect bilingual CS, where two grammatical systems contribute jointly to the morphological and syntactic properties of the resulting forms. We therefore conclude that such patterns are best analyzed as CS, regulated by interface conditions such as the PFIC rather than by the mechanisms of lexical borrowing.

6.2 Limitations of the BTH approach

The BTH proposed by López et al. (Reference López, Alexiadou and Veenstra2017), presented in (28), offers a phase-based account of CS formulated within the minimalist framework, adopting distributed morphology (DM) as its morphosyntactic architecture.Footnote 17

Unlike lexicalist models that assume early lexical insertion (e.g., MacSwan, Reference MacSwan2000), the BTH assumes late insertion, with post-syntactic vocabulary realization. Building on phase theory (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriagereka2000), it posits that material is transferred to the interfaces in a single unit per phase, thereby constraining CS to phase boundaries and ruling out intra-phase switching. This model is intended to account for key generalizations in the CS literature, including the FMC and the principle of functional restriction (González-Vilbazo, Reference González-Vilbazo2005), and is claimed to surpass earlier accounts in empirical scope.

While conceptually elegant, the BTH faces two significant empirical challenges. First, it fails to account for the observed asymmetry between inflectional and derivational morphology in intra-word CS. According to López et al. (Reference López, Alexiadou and Veenstra2017), it is possible to code-switch between a root and a derivational morpheme, but not between a derivational and an inflectional morpheme. This pattern is illustrated in (29), where the Spanish root cabre ‘anger’ combines with a German verbalizer -ier and a German participial suffix -t in (29a), yielding an acceptable mixed form. In contrast, replacing -t with the Spanish participial -ado results in ungrammaticality, as shown in (29b).

In their analysis, derivational morphemes are realizations of categorizing heads (e.g., v or n) and thus belong to a separate phase from the root (Arad, Reference Arad2003; Embick & Marantz, Reference Embick and Marantz2008). This permits CS between the root and the categorizer. Inflectional morphemes, however, are transferred together with the categorizer in the same phase and must therefore be in the same language. The structure for cabreiert ‘angered’ in (29a) is shown in (30), where -t (inflection) and -ier (v) are phase-mates, while the Spanish root cabre originates in a separate phase.

(López et al., Reference López, Alexiadou and Veenstra2017, p. 12)

This analysis, however, has difficulty accounting for the asymmetry exemplified by forms such as email-guo ‘email-ASP’ and modern-hua ‘modern-ize.’ Under standard BTH and DM assumptions, both forms might be expected to be well-formed. In the case of email-guo ‘email-ASP,’ we can posit a covert Chinese verbalizer under v in (31a), mirroring the structure in (30). Here, the English verb email occupies a separate phase from both -guo and the categorizer. On this account, the BTH correctly predicts the acceptability of email-guo ‘email-ASP.’ A parallel derivation can be proposed for modern-hua ‘modern-ize,’ in which -hua functions as a verbalizer and modern as its root complement, as in (31b). While the BTH would treat this configuration as acceptable, our experimental results suggest that modern-hua ‘modern-ize’ is consistently dispreferred by participants, exhibiting notably lower acceptability ratings than email-guo ‘email-ASP.’

Second, the broader empirical adequacy of the BTH is undermined by attested cases that violate phase-boundary constraints. Under López et al.’s (Reference López, Alexiadou and Veenstra2017) model, material within the complement of a phase head – such as TP – must be transferred as a unit and originate from the same language. This includes VP adverbs generated as being adjoined to vP or v’, which are predicted to surface in the same language as the verb and subject. However, this prediction is not supported by empirical data. As shown in (32), drawn from Hebblethwaite (Reference Hebblethwaite2010), really – which he analyzes as a VP adverb – can occur in code-switched utterances even when the surrounding structure is monolingual. Notably, the presence of pa (assumed to be Neg) before really supports its position inside the VP. This pattern contradicts BTH predictions and undermines the general applicability of phase-based constraints on CS.

In sum, while the BTH offers a principled explanation for phase-based constraints on CS, it does not adequately account for the asymmetry between inflectional and derivational morphology in our data. It also faces broader empirical challenges, including attested cases of intra-phase switching, such as adverb insertion. These issues suggest that, in its current form, the BTH falls short of capturing the full range of bilingual word formation phenomena.

7. Conclusion

This study investigates a robust asymmetry in bilingual word formation: English bases readily combine with Chinese inflectional morphemes but systematically resist Chinese derivational ones. We argue that this contrast cannot be fully explained by borrowing-based accounts or phase-based constraints, nor does it necessitate abandoning the FMC. Building on MacSwan (Reference MacSwan1997, Reference MacSwan1999), we assume that the FMC applies to X⁰-level words formed prior to spell-out. Apparent violations, we suggest, can instead be systematically derived from the PFIC, assuming that word formation is permitted in the post-syntactic component. Within a framework that permits post-syntactic affixation (Harwood, Reference Harwood2014; Lasnik, Reference Lasnik, Campos and Kempchinsky1995, Reference Lasnik2003), this analysis offers a unified account of the morphological asymmetries observed, without appealing to language-specific stipulations.

The central theoretical contribution of this study lies in demonstrating that the PFIC can be productively reinterpreted within a lexicalist framework that incorporates post-syntactic affixation. In contrast to MacSwan’s pre-syntactic model, our approach allows affixation at PF rather than restricting it to the lexicon, thereby reinforcing the viability of lexicalist accounts that distinguish between derivation in the lexicon and inflection at the post-syntactic level.

This analysis also has broader implications. First, it underscores that constraints on CS must be evaluated in light of derivational timing and grammatical architecture – not merely surface well-formedness. Second, it expands the typology of bilingual word formation by showing that word-internal CS is not categorically excluded but may be licensed under specific conditions of affix attachment. Third, it highlights the role of interface conditions in shaping cross-linguistic word formation, suggesting avenues for comparison with other domains such as compounding.

At the same time, certain methodological limitations warrant consideration. This study relies on offline grammaticality judgment tasks, which – while standard in syntactic research – may be influenced by performance factors such as metalinguistic awareness or task-specific strategiesFootnote 18 (Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2005). Future work would benefit from a multi-task approach (Gullberg et al., Reference Gullberg, Indefrey, Muysken, Bullock and Toribio2009) that combines offline and online methods. Real-time methods such as reaction time, self-paced reading, and event-related potentials (ERPs) can illuminate the processing demands of different affixation types, while auditory presentation may clarify how prosodic and phonological cues shape acceptability. The present findings offer both a theoretical framework and an empirical point of departure for future research on the morphological structure of bilingual grammar.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Hong-lin Li for his statistical assistance and for advice on the experimental design. I also thank Yu-Yin Hsu and Shiao-hui Chan for their insightful suggestions on designing and presenting the experimental results. I am indebted to James Myers for his input on framing the research question and to Yafei Li for valuable discussions and comments on an earlier draft. I would also like to thank the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, for the opportunity to conduct research as a visiting scholar in 2013. I thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their constructive feedback, which greatly improved the clarity and framing of this article. Earlier versions of this work were presented at the Symposium on Language Contact: The State of the Art (Helsinki, 2014), the 25th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics (IACL-25, Budapest, 2017), and the joint ACBLPE & SPCL 2019 conference (Lisbon), where I benefited from audience feedback. All remaining errors are my own.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSC 102–2410-H-003-022-MY2; NSTC 114–2410-H-003-032).

Competing interests

The author declares none.