Who wolde wene, or who wolde suppose, the wo that in myn herte was, and pyne?

[Who would believe, or who would suppose, the woe that in my heart was, and pain?]

Wife of Bath Prologue, The Canterbury Tales.

1. Introduction

The distinctive package of human biosocial adaptation has greatly expanded the species’ success including fertility and life expectancy. Yet it has come with a price imposed as risk to psychological well-being that differentially plagues females and males compounded by the paradox that females report more overall morbidity whereas males are more likely to die (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bann and Patalay2021; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Kyu, Aali, Abbafati, Abbas, Abbasgholizadeh, Abbasi, Abbasian, Abd Elhafeez, Abdelmasseh, Abd-Elsalam, Abdelwahab, Abdollahi, Abdoun, Abdullahi, Abdurehman, Abebe, Abedi, Abedi and Murray2024). Here, an adaptationist approach is applied to evaluate this paradox as it pertains specifically to women’s mental health. We begin by defining mental illness, briefly reviewing current data on global mental health, and cataloguing characteristics of mood disorders. We then survey what is known about risk factors that underlie mental conditions in females and proceed to consider various adaptationist theories to account for the predominance of mood disorders, specifically depression. Contemporary data necessarily do not reflect historic mental conditions, however, so we map out women’s life cycles in small-scale non-industrial societies along with the risks and challenges that confront them. We consider the thin ethnographic data about mental health from such societies, and conclude by integrating these streams of information into a dynamic schema characterizing differential female mental health.

1.1. What is mental illness?

Mental illness is relative, a condition of thinking, feeling, and/or behaviour that impairs one’s ability to function. This leads to the problem of defining normal functioning: How do we know if someone is ‘normal’? Here we come directly to social and cultural models that delineate the roles and statuses of individuals with the attendant norms and expectations for how those should be performed (Luhrmann, Reference Luhrmann2000). Intense sociality of humans adds expectations for appropriate patterns of speech, comportment, and social interactions. Every society differs along these dimensions, while sex and gender affect how they are configured. Gender norms and expectations are ubiquitous although societies vary widely in the forms they take. Flagrant digression from social norms swiftly conduces to stigmatization and marginalization, although some mental conditions that bend such norms may be tolerated or even valorized (Obeyesekere, Reference Obeyesekere1981). Wakefield’s influential, widely debated concept of harmful dysfunction regards ‘dysfunction’ as something that fails to accomplish its evolved purpose, whereas ‘harmful’ is more subjective because in some cases of dysphoria or anxiety emotion regulation systems may be doing just what they should (Faucher & Forest, Reference Faucher and Forest2021).

1.2. Sex differences in mental health: current evidence

Mental disorders have received increasing attention once the magnitude of their lifetime health burden was demonstrated (Murray & Lopez, Reference Murray and Lopez1996). Current global health tracking identifies them as increasingly prominent causes of suffering and disability, ranking among the top 10 worldwide sources of health burden. Indeed, cases increased by 50–80% between 1990 and 2021, by which time they affected over 80% of the global adult working population aged 16–65 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Zuo and Zhu2025; GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022). The influence of reduced stigma, increased screening, or actual increases in cases remains uncertain. The important advance was to recognize and evaluate lost healthy life, not merely mortality.

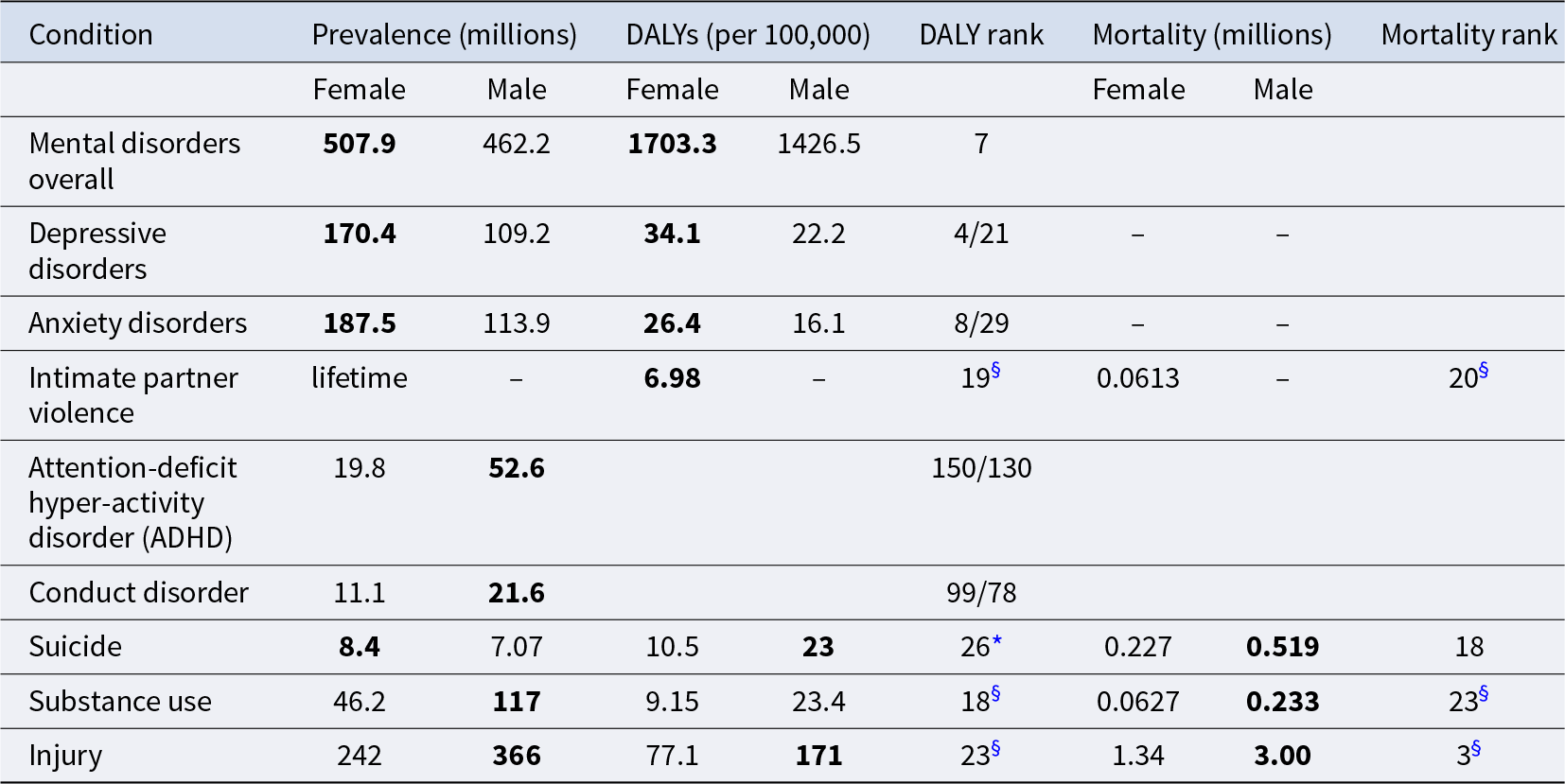

Gender differences in mental disorders follow distinctive patterns overall (Table 1), although they vary regionally and through time (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bann and Patalay2021). Prevalence of mood disorders, depression, and anxiety are high in both sexes but are 50% greater among females. The same is true of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs, where one DALY equals a one-year loss of full health), exacting a 50% greater mental health burden for women. Mood disorders exhibit a developmental pattern in females: a review of large data sets from 90 countries found female: male (F:M) odds ratio (OR) 2.37 for disorder at age 12, a peak at OR 3.02 ages 13–15, a decline to OR 2.69 ages 16–19, then stability in adulthood (Salk et al., Reference Salk, Hyde and Abramson2017). Depressive symptom prevalence, by contrast, is low ages 8–12, increases steeply in girls at ages 13–15, climbs even more ages 16–19, and declines ages 20–29, remaining stable thereafter at a F:M sex ratio of 1.71–2.02. Mood disorders may occur throughout life and are not direct sources of mortality; rather, they may contribute to shortened lifespan through effects on physical health and health-endangering behaviours. For instance, females attempt suicide more often than do males, although they are half as likely to succeed (Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Bland, Canino, Greenwald, Hwu, Joyce, Karam, Lee, Lellouch, Lepine, Newman, Rubio-Stipec, Wells, Wickramaratne, Wittchen and Yeh1999).

Table 1. Prevalence of prominent conditions and their health impact in 2019, by gender. (Source: GBD 2021 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022)

* Rank among Level 3 causes for global DALYs, both sexes combined.

§ Rank among attributable Level 2 risks for global deaths and DALYs in 2021 for box sexes combined. Males not included.

Numbers in bold indicate gender with greater prevalence, burden, or mortality.

Other mental conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, and conduct disorder are more prevalent among males, but have less impact on lifetime morbidity or direct mortality due to lower impairment or prevalence (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2024). However, males experience higher rates of substance use disorder (over double that in females) and mortality (nearly 4-fold that of females). Although not a mental disorder, note that injury morbidity and mortality is more than doubled among males over females, greatly contributing alongside substance use to gender differences in mortality.

Maternal depression in pregnancy and postpartum is ubiquitous although prevalence is variable. Antenatal rates of depression may match or exceed postnatal levels and vary widely among populations yet range significantly higher in low- and-middle income countries (LMIC) than in high-income countries (HIC), from 19% to 50% in LMICs against 7–20% in HICs (reviewed in Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Worthman, Norwood, le Roux and O’Connor2023). Likewise, prevalence of postpartum maternal depression ranges widely and is distinctly higher in LMICs than HICs, averaging over 20% in the former and around 10% in the latter. Compared to postnatal depression, maternal prenatal depression remains under-recognized and under-treated (Gelaye et al., Reference Gelaye, Rondon, Araya and Williams2016), yet it makes a large contribution to suffering and lost human potential through its deleterious effects on both mothers and their children.

In sum, global evidence shows that mood disorders levy a substantial health burden in females today (Piccinelli & Wilkinson, Reference Piccinelli and Wilkinson2000), distinct from some major sources of health burden for males (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Zhao, Xu, Wang, Zhu, Yang, Zou, Li, Liu, Ye, Shi, Wang, Song and Wang2025). Lifetime recall of episodes can be faulty, but estimates for U.S. lifetime risk are, minimally, depression 20%, anxiety 30%, and comorbidity 50%, with highest onsets at 14 and 13, respectively (Martel, Reference Martel2013). Women with either disorder suffer more impairment than men. Importantly, rates and sex differences differ across settings for reasons to be explored further on.

1.3. Characteristics of mood disorders (depression and anxiety)

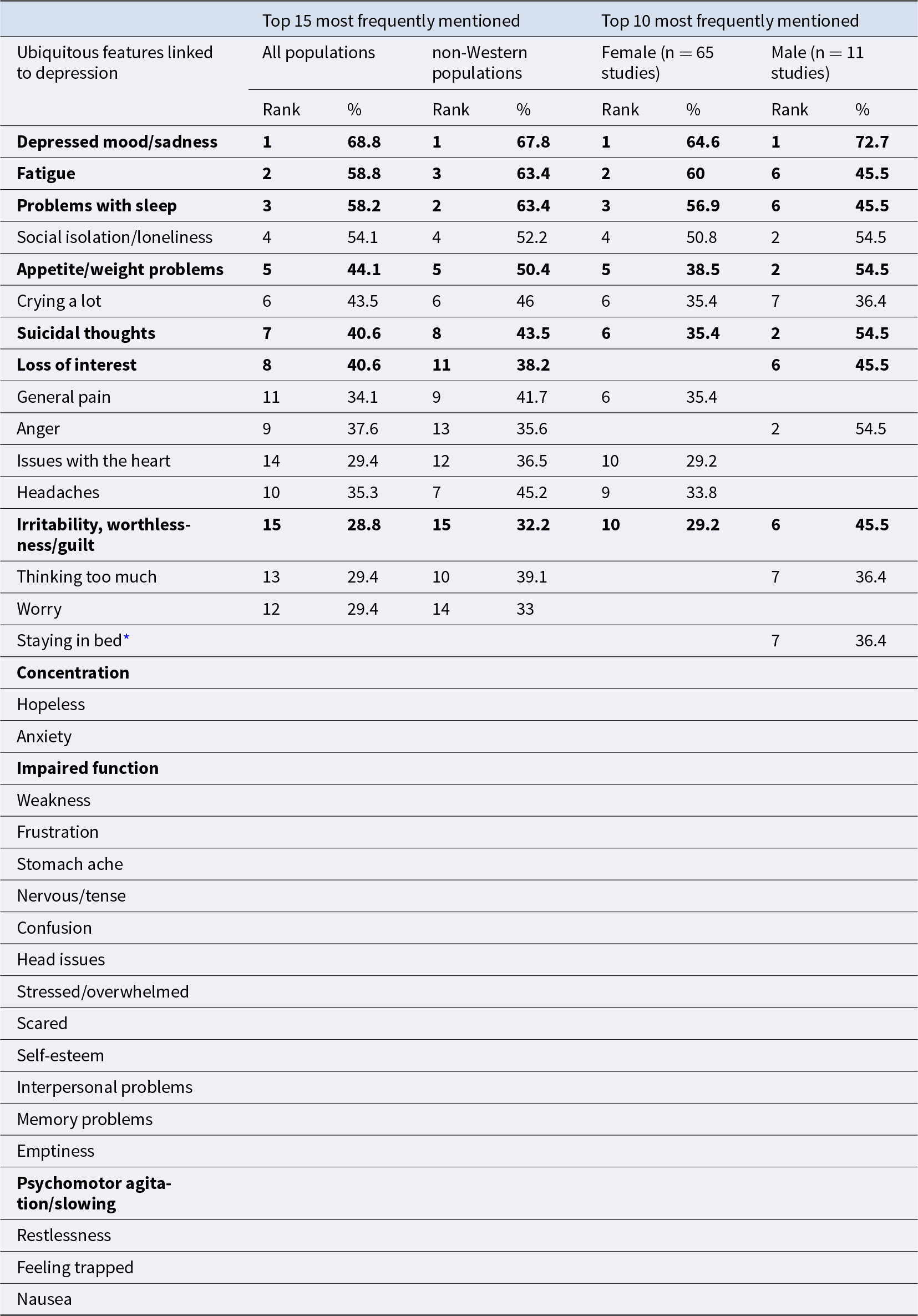

The outstanding mental illnesses among women are depression and anxiety, on which we will focus henceforth. Depictions of negative mood and melancholia feature in accounts across societies and the ages, and causal explanations and treatments exist in virtually every healing tradition. Allopathic diagnostic inventories such as iterations of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) have been developed for use in clinical and research settings. Demonstrations of cultural differences belatedly have spurred the global mental health effort to formulate assessments suitable for all human populations (Kirmayer et al., Reference Kirmayer, Gomez-Carrillo and Veissière2017). A survey of 170 qualitative studies of depression in 77 ethnicities/nationalities is summarized in Table 2, which lists 30 features of depression mentioned in all studies, along with the ranks of top 15 among all and among non-Western populations as well as the top 10 for women and men (Haroz et al., Reference Haroz, Ritchey, Bass, Kohrt, Augustinavicius, Michalopoulos, Burkey and Bolton2017). Note that 7 of the 15 relatively most frequent symptoms are included in the DSM-5 diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder, but four of the most frequently mentioned ubiquitous features (social isolation/loneliness, crying, anger, and general pain) are not. Conversely, other DMS-5 items (impaired function, problems with concentration, and psychomotor agitation or slowing) were infrequently reported. Despite commonalities across regions, prevalence varied, such that issues with heart predominated in South and Southeast Asian populations and thinking too much predominated in Southeast Asian and sub-Saharan regions. Many features of depression coincided with anxiety disorder symptoms, including worry, issues with breathing, irritability, problems with sleep, and restlessness. Depression and anxiety are distinct yet commonly are comorbid, sharing risk factors, neurocognitive features, and treatment modalities, while each disorder encompasses subtypes.

Table 2. Ubiquitous and major features of depression: global, non-Western, female, and male (source: Haroz et al., Reference Haroz, Ritchey, Bass, Kohrt, Augustinavicius, Michalopoulos, Burkey and Bolton2017)

Bold = diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder in the DSM-5.

* Prominent only among males.

Turning to gender differences, many more studies have investigated women than men. Moreover, women dominate the ranked prevalence of symptoms and, distinct from men, feature general pain, heart issues, and headaches, whereas men are distinct for equal prominence of anger, suicidal thoughts, social isolation, and appetite/weight problems. Additionally, the list of 30 symptoms mentioned in every one of the surveys suggests the wide variety of experiences that may attend depression. Importantly, some contend that of male-typical depressive symptoms (aggression, irritability, violence, substance abuse, risky behaviour, somatic complaints), those in bold are largely excluded from diagnostic inventories for depression and therefore skew the sex ratio of prevalence (Call & Shafer, Reference Call and Shafer2015).

2. Risk factors in mood disorders: distal to proximate

Mood disorders, and many other mental conditions, are a product of contextual, cultural, experiential, and biological factors that operate during development and across the lifespan. As extensive research has come to recognize, depression or anxiety rarely have a single cause; rather, they are outcomes of dynamics specific to each person’s circumstances and experiences. Consequently, intersectionality plays a role, as an individual’s unique configuration of identities (such as gender, race, clan, ethnicity, status) interact in the person’s circumstances and experiences.

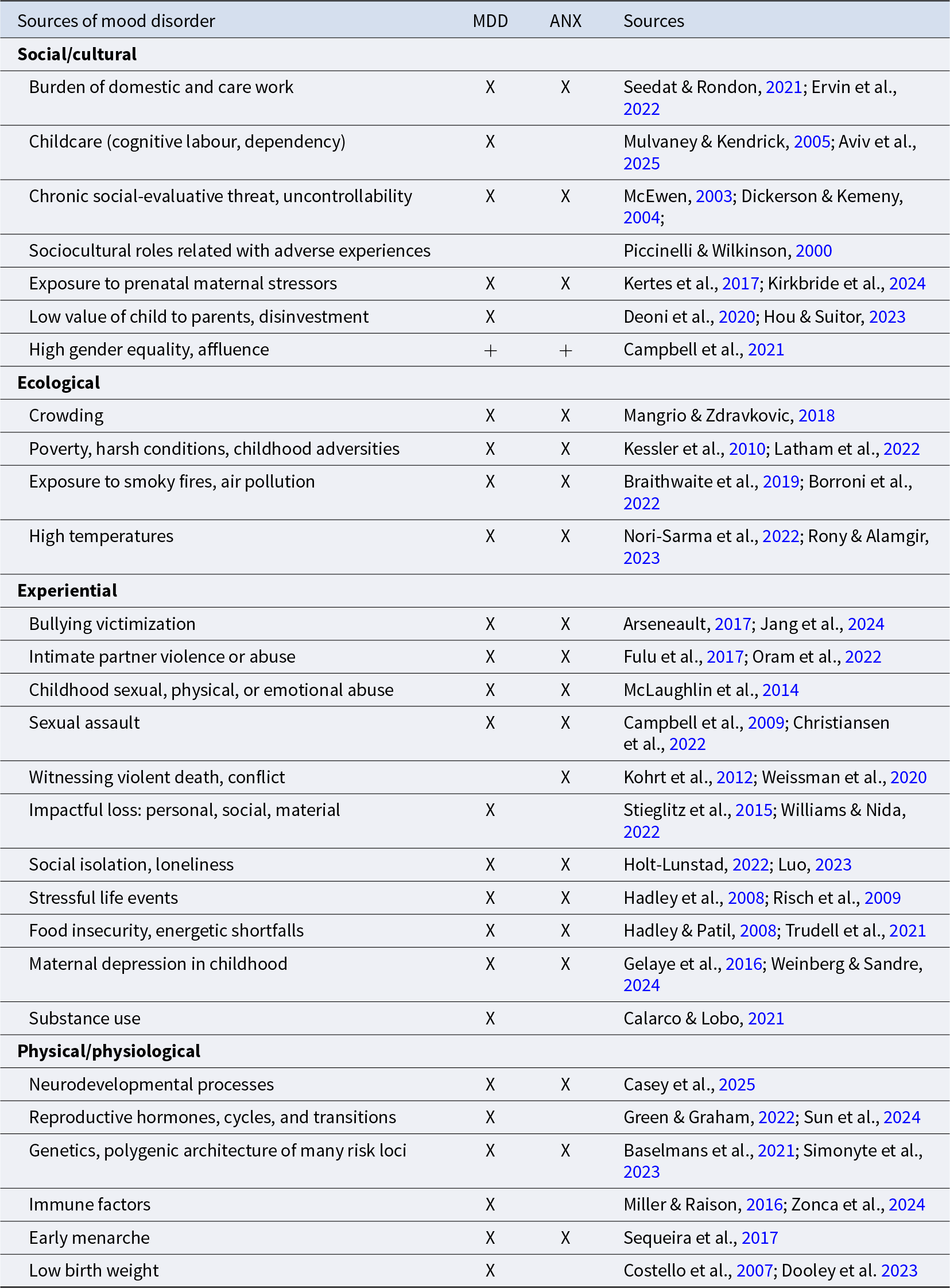

Epidemiological data flag that the most proximate factor predicting onset of depression is that something bad happens, often loss or conflict. But this event is merely a precipitating factor, the tip of interacting cumulative conditions and processes. As shown in Table 3, dimensions known to play roles in mood disorder range from the cultural and social to ecological, experiential, and physical and physiological. Each interacts with the others from conception across the life course to influence risk for disorder. In the following sections, please refer to Table 3 for supporting references.

Table 3. Conditions contributing to mood disorder

MDD = major depressive disorder; ANX = anxiety disorder. + = increases risk overall.

2.1. Cultural and social factors

Cultural and social factors include gendered social norms that designate women as homemakers and nurturers such that they take a disproportionate burden of domestic and caregiver responsibilities. Today, women undertake three-quarters of the world’s care and domestic work, more in LMIC and lower-income households overall (Seedat & Rondon, Reference Seedat and Rondon2021). Even in more egalitarian societies such as the USA, mothers perform more domestic labour, both physical and cognitive, than do their partners (Aviv et al., Reference Aviv, Waizman, Kim, Liu, Rodsky and Saxbe2025). Our highly immature and dependent children require provisioning, support, and protection well into the second decade. This exacts physical and cognitive loads that escalate as number of offspring increases, particularly when alloparental care is limited as in today’s nuclear households. Such unpaid work among employed adults has been linked to mood disorder and diminished life satisfaction in women but not men (Ervin et al., Reference Ervin, Taouk, Alfonzo, Hewitt and King2022). Depending on statuses and expectations of females at each life stage, they may be subject to levels of social-evaluative threat and uncontrollability known to be linked to stress and mood disorder. For instance, 78% of low-caste versus 40% of high-caste women in a rural Nepal population scored as depressed (43% overall versus 19% for men), and 71% versus 34% as anxious (45% overall versus 9% for men) (Kohrt & Worthman, Reference Kohrt and Worthman2009). Besides stressful life events and poverty, key factors included partner violence and disinvestment, high fertility and struggle for resources, widowhood, and reduced productivity with age. These conditions of conflict and adversity illustrate how cultural norms and social roles for females can constrain choice, impose competing social roles, or exact role overload to increase the risk for depression or anxiety.

The high cost of childbearing and rearing require support from others. Known stressors associated with depression in pregnancy and postpartum include partner lack or loss, domestic violence or history of abuse, and high perceived stress and adverse life events (Biaggi et al., Reference Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby and Pariante2016). Moreover, where a child is perceived to have low value to the parents by virtue of gender, existing number of children, and future prospects, childcare and long-term treatment are diminished accordingly (Hrdy, Reference Hrdy1990). Confoundingly, global mental health data show greater prevalence of mood disorders among females in both affluent countries and those ranking high on gender equality (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bann and Patalay2021).

2.2. Ecological factors

Ecological conditions shaping risk for mood disorder include crowding, poverty, harsh living conditions, and particularly childhood adversities that shape emotional development and erode resilience to stressors. Deprivation and threat differ: deprivation is the lack of environmental inputs and quality whereas threat comprises experiences that compromise one’s physical and emotional welfare (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014). Each has distinct impact on neurodevelopment that mediate long-term effects of adversity and contribute to risk for mood disorder. Threat is particularly subject to cultural influences that set the value, treatment, and expectations of girls.

A quite different but relevant aspect of human ecology is the use of fire. Humans have relied on solid fuels for cooking and heat over at least hundreds of thousands of years, and nearly 3 billion people still do so. However, it turns out that exposure to particulate matter generates 4 million annual premature deaths among children and adults from physical illness and also increases risk for depression, anxiety, and suicide (World Health Organization, 2014). Smoky household fires are important not only for cooking and heat, but also for fending off insects and predators, incurring health trade-offs. In their role as cooks and providers, women are most exposed, as are the children who hang around them, so that females experience greater lifetime exposure whereas men are most exposed early on. Then, of particular relevance given ongoing rapid global warming, high temperatures have been found to promote both anxiety and depression, along with irritability that can lead to domestic and general conflict with tangible societal impact (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Ali, Benmarhnia, Pearl, Massazza, Augustinavicius and Scott2021).

2.3. Experiential factors

A wide range of experiential factors is involved in mood disorders; most impactful from current global evidence are bullying victimization, intimate partner violence or abuse (IPV), and childhood sexual, physical, or emotional abuse (Arseneault, Reference Arseneault2017; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McLaughlin, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alhamzawi, Alonso, Angermeyer, Benjet, Bromet, Chatterji, de Girolamo, Demyttenaere, Fayyad, Florescu, Gal, Gureje and Williams2010; Oram et al., Reference Oram, Fisher, Minnis, Seedat, Walby, Hegarty, Rouf, Angenieux, Callard, Chandra, Fazel, Garcia-Moreno, Henderson, Howarth, MacMillan, Murray, Othman, Robotham, Rondon and Howard2022). Early abuse is distinct from other childhood adversities such as poor housing, precarity, or parent loss, and has enduring effects on behaviour, emotion regulation, and relationships based in part of their neurodevelopmental effects along with ongoing influences from the conditions that produced the abuse in the first place (McLaughlin, Weissman, et al., Reference McLaughlin, Weissman and Bitrán2019). Impact of early abuse is partially gender differentiated (more sexual abuse in females, more physical and overall abuse in males), and is strongly associated with subsequent depression and anxiety in females not males (Assari et al., Reference Assari, Najand and Donovan2025). Early life familial stress or abuse influences stress (hypothalamo-pituitary–adrenal [HPA]) axis function linked with depressive symptoms in young adulthood (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Adam, Bechayda and Kuzawa2020). Experience of early abuse also heightens vulnerability to another major source of mood disorder, IPV. In 2018, estimated global prevalence among ever-married or -partnered women aged 15–49 who had experienced IPV at least once was 27%, 13% in the past 12 months with highest incidence ages 15–40 but nonetheless present thereafter (World Health Organization, 2021). Women experience more mental health problems from experiencing abuse or IPV than do men (Oram et al., Reference Oram, Fisher, Minnis, Seedat, Walby, Hegarty, Rouf, Angenieux, Callard, Chandra, Fazel, Garcia-Moreno, Henderson, Howarth, MacMillan, Murray, Othman, Robotham, Rondon and Howard2022). For instance, a national survey of IPV in the USA found near gender equivalence in lifetime prevalence (47%:44% F:M), yet women (41%) reported more IPV with impact than men (26%) (Leemis et al., Reference Leemis, Friar, Khatiwada, Chen, Kresnow, Smith, Caslin and Basile2022). Some settings normalize these experiences as women’s lot and men’s prerogative (Badenes-Sastre et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Spencer, Alonso-Ferres, Lorente and Expósito2024), but that does not efface the relationship to risk for mood disorders. Sexual assault and rape occur outside marriage or partnership, across a wide range of settings from domestic to social disruption and war, and is strongly modulated by attitudes (gender role views, sexism, rape myths) shaping social perceptions of sexual violence that, in turn, inform their impact on victims (Trottier et al., Reference Trottier, Laviolette, Tuzi and Benbouriche2025). Relatedly, witnessing violent death or conflict in everyday, disaster, or war settings affects women’s risk for mood disorder.

Adverse events pose potent risks for depression among women, comprising personal, social, or material loss where the loss was unexpected, unwarranted, or violated norms and caused harm along a gradient from loss of status or social capital, shame, grief, impoverishment, or marginalization, for example widowhood and partner disinvestment. Also harmful are loss of capacities or roles that provide a sense of meaning, value to the community, and self-worth, as with ageing and diminution of productivity. Similarly, stressful life events that carry psycho-emotional weight are strongly implicated in risk for both depression and anxiety, as are social isolation and loneliness. Regarding material resource need and dependency, food insecurity induces depression and anxiety in adolescents and mothers. The impact can be substantial: food insecurity plagues over half of Africans and has dose–response effects on poor mental health, particularly in women (Trudell et al., Reference Trudell, Burnet, Ziegler and Luginaah2021). This association serves to fuel another important risk factor for depression and anxiety, namely experience of having a depressed mother in childhood which has consistently been correlated with risk for mood disorders. Impact of mothers on daughters who become mothers conduces to a cycle of intergenerational transmission of poor mental health (Goodman, Reference Goodman2020). Lastly, although substance abuse is less prevalent among women, use nonetheless comes with risk for depression, although youth may take up substance use to blunt dysphoria in the first place (Sung et al., Reference Sung, Erkanli, Angold and Costello2004).

2.4. Physical and physiological factors

The roles of physical and physiological risk factors in female’s mood disorders are increasingly well characterized. The advent of neuroimaging has generated an ever-clearer picture of neurodevelopmental processes and the pathways related to risk for psychopathology. Development of these pathways begins in gestation and continues throughout life, although two windows – the first 1000 days since conception, and adolescence – have emerged as important sensitive periods. Of note is the impact of reproductive hormones related to sex development which affect neurodevelopment (Rubinow & Schmidt, Reference Rubinow and Schmidt2019). Girls experience transiently high levels of estradiol ages 4–6 months, whereas testes of male fetuses are active 8–24 weeks in gestation with masculinizing effects, followed by an androgen peak 3–4 months after birth. Puberty brings another period of organizational (permanent, structural) and activational (initiating) effects of sex hormones (primarily oestrogens, and to some extent androgens in girls) that include brain organization and responses to the environment which alter behaviour, emotions, and thought (Dahl et al., Reference Dahl, Allen, Wilbrecht and Suleiman2018). The sexes differ in the timing, pace, and drivers of hormonal and neurodevelopmental changes that interact with stressors and likely induce the difference in depression including increasing depressive symptomatology beginning early in female puberty (Li & Graham, Reference Li and Graham2017).

Neuroendocrine reorganization in puberty also involves the HPA and stress reactivity. HPA activity increases during puberty, when girls develop increased cortisol reactivity (Gunnar et al., Reference Gunnar, Wewerka, Frenn, Long and Griggs2009) which, in turn, is associated with anxiety and depression. Prior experience matters: early life stress is associated with reduced cortisol reactivity in early puberty and predicts depression (Kircanski et al., Reference Kircanski, Sisk, Ho, Humphreys, King, Colich, Ordaz and Gotlib2019). By contrast, hyperreactivity in mid-pubertal girls predicts later depression (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Kircanski, Foland-Ross and Gotlib2015). Social environment (supports, stressors) have been found to moderate girls’ HPA functioning during puberty, for good or ill (Reid et al., Reference Reid, DePasquale, Donzella, Leneman, Taylor and Gunnar2021). Following puberty, ovarian cycles and reproductive transitions (pregnancy, postpartum, menopause) that entail endocrine shifts also are associated with mood disorders in women (Handy et al., Reference Handy, Greenfield, Yonkers and Payne2022).

Heritability of depression has spurred intensive investigation with the result that no single gene has been found responsible; rather, both depression and anxiety exist in diverse forms and are associated with polygenic architectures involving many loci. Likely epigenetic and experience–responsive genetic factors play roles as well and may come on line as vulnerabilities during critical developmental periods in adolescence (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Worthman, Adhikari, Luitel, Arevalo, Ma, McCreath, Seeman, Crimmins and Cole2016; Kuzawa & Thayer, Reference Kuzawa and Thayer2011). Functional genetic markers have been found to interact with context (family conflict, maltreatment, stressful life events, parental depression) to generate internalizing conditions such as depression, and context effects are greater in females (Martel, Reference Martel2013). Direct causality has been found for immune factors which are stress- and antigen-responsive and have potent central nervous system effects on mood and energy level (Zonca et al., Reference Zonca, Marizzoni, Saleri, Zajkowska, Manfro, Souza, Viduani, Sforzini, Swartz, Fisher, Kohrt, Kieling, Riva, Cattaneo and Mondelli2024).

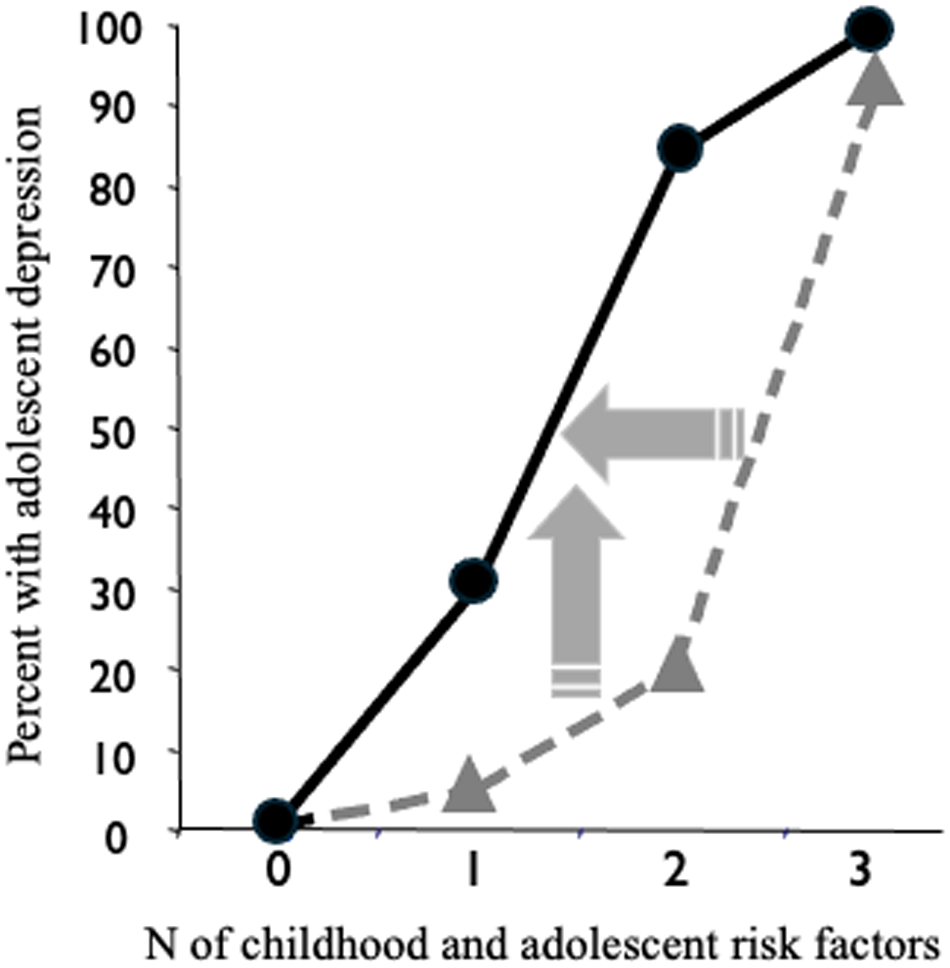

On a less granular level, early menarche is consistently associated with more depression symptoms and disorder, particularly against a background of childhood trauma (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Platt, Keyes, Sumner, Allen and McLaughlin2020). Depression risk increases with decreasing age at menarche (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009), which may contribute to the association between affluent countries and prevalence of female depression. However, a longitudinal population study in the UK recently found that girls with early menarche had more depressive symptoms at age 14 only, not at any teen age thereafter (Sequeira et al., Reference Sequeira, Lewis, Bonilla, Smith and Joinson2017). In terms of developmental effects, our large longitudinal study in North Carolina found that low birthweight (LBW) girls were highly sensitized to exposure to risk factors for depression (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Worthman, Erkanli and Angold2007). Indeed, the LBW effect largely explained the sex difference in depression rates in our sample ages 9–16. Given that 14.7% of newborns were LBW globally in 2020 (Okwaraji et al., Reference Okwaraji, Krasevec, Bradley, Conkle, Stevens, Gatica-Domínguez, Ohuma, Coffey, Estevez Fernandez, Blencowe, Kimathi, Moller, Lewin, Hussain-Alkhateeb, Dalmiya, Lawn, Borghi and Hayashi2024), it poses a potentially significant risk to women’s mental health.

3. Adaptationist theories of gender differences in mental disorders: ultimate causes

Depression is common, damaging, and heritable (Baselmans et al., Reference Baselmans, Yengo, van Rheenen and Wray2021); anxiety, likewise. Moreover, both conditions emerge before reproduction, can impair fitness, and therefore should be targets of natural selection. Why then have they not been selected against over the course of human history? This conundrum has challenged evolutionary-adaptationist thinkers to propose theories that explain the high prevalence of depression in terms of adaptation rather than pathology. These efforts are hampered by the paucity of mood and mental health data in history and prehistory and the need to rely on ethnographic records or current non-industrial populations. Proposals include, first, that depression is a protective mechanism, a signal triggered by adversities to stimulate adaptive responses initiated by low mood and sadness. Symptoms serve as a warning to the sufferer and others both that there is a problem or need, and that action or help is required to solve it (Hagen, Reference Hagen2011; Nesse, Reference Nesse2019; Schroder et al., Reference Schroder, Devendorf and Zikmund-Fisher2023). Second, some proposals build on the ruminative qualities of negative mood to suggest that it promotes analytic thinking and evolved as an adaptive response for solving complex problems such as challenges to resource management, social conflicts or losses, or physical difficulties (Andrews & Durisko, Reference Andrews, Durisko, DeRubeis and Strunk2017; Nesse, Reference Nesse2019). A third and related explanation is that depression represents normal and adaptive reactions to highly adverse conditions (Hunt & Jaeggi, Reference Hunt and Jaeggi2025). Adversity such as failures of life goals, low social capital, social defeat, or existential threat generate depressive mood that motivates avoidance of situations that reduce fitness, induce signals of distress to elicit support, and prompt rumination to tackle these problems (Nesse, Reference Nesse2000). Moreover, depression dampens risk-taking and competitiveness, thereby moderating social risk and stabilizing important social relationships (Allen & Badcock, Reference Allen and Badcock2003).

These explanations regard depression, including suicidality, as a costly signal of adversity that can be socially alienating but elicits support (Gaffney et al., Reference Gaffney, Adams, Syme and Hagen2022). In terms of strategies, a bargaining power model posits that depression in females is a ploy to compel aid under gendered inequity and adversity, gaining plausibility from evidence that female upper body strength largely mediates the effect of gender on depression (Hagen & Rosenström, Reference Hagen and Rosenström2016). Indeed, greater grip strength is associated with lower depression and use of anger in both sexes (Oh et al., Reference Oh, Kim, Lee, Yon, Lee, Smith, Kostev, Koyanagi, Solmi, Carvalho, Shin, Son and Lee2023; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Rosenström and Hagen2022), and proneness to anger in attractive women (Billingsley et al., Reference Billingsley, Goldwert and Lieberman2025). Hagen and Syme’s review highlights conflict and power asymmetries, concluding that ‘depression evolved, in part, as a form of psychological pain that functions to mitigate harm, credibly signal need, and coerce help when the powerless are in conflicts with powerful others’ (Hagen & Syme, Reference Hagen, Syme, Al-Shawaf and Shackelford2024, p. 1135). In that regard, suicidality is a potent signal of need in social conflicts, particularly evident under power asymmetries of parents and offspring contributing to depression and suicidality in adolescence (Syme et al., Reference Syme, Garfield and Hagen2016).

Fourth, sexual selection theory points to sex differences in development, with high androgen exposure in gestation and early infancy in males and high oestrogen exposure later in females, at puberty. In females, sex-differentiated behavioural and psychological dispositions fostered by differential developmental trajectories drive stress diathesis via rapid increases of estradiol in puberty alongside a neuroendocrine cascade including cortisol. This process greatly increases female sensitivity to inter- and intrapersonal stressors arising from physical changes, self-representations, and social responses (Christiansen et al., Reference Christiansen, McCarthy and Seeman2022; Martel, Reference Martel2013). Such pressing stressors trigger empathy, rumination, and self-blame or frustration that conduce to dysphoria with situationally and idiosyncratically constituted sequelae. Indeed, greater interpersonal sensitivity in females is linked both to greater emotional distress and to more adaptive social behaviour, a cost with a benefit (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Modi, Rudolph, Hupp and Jewell2020). Sociocultural contexts play important roles in the stress diathesis processes and outcomes as sex/gender status constrain and sculpt behaviour, affect, roles, statuses, and life options.

Fifth, a life-history framework points to gender differences in dynamics of the life course (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Steinberg and Draper1991), particularly trade-offs around mating versus parenting, quality and quantity of offspring, and current versus future reproduction (Del Giudice, Reference Del Giudice2014). Sex/gender and individual differences in resource allocation yield different life history strategies, as do developmental processes sensitive to resource availability, unpredictability, and extrinsic mortality. Women have a limited reproductive lifespan of 20–25 years whereas men, in principle, have nearly twice that. Moreover, the pace of reproduction is limited by gestation and lactation. Hence, trade-offs for current versus future reproduction are more urgent for women. This framework has yielded weak analytic traction: evidence identified depression at both ends of the fast–slow life-history continuum, likely related to distinct forms of depression, although fast life-history strategies (live fast, die young) appear associated with high dysphoria and somatic symptoms, especially in females.

Sixth, evolutionary mismatch may contribute to female risk for depression (Nesse, Reference Nesse2023). Nucleation of families and rise of single motherhood along with increased involvement of women in the workplace all may contribute to overload and conflict around ability to care adequately for offspring, resulting in anger, sadness, frustration, and risk for mood disorder (Aviv et al., Reference Aviv, Waizman, Kim, Liu, Rodsky and Saxbe2025; Seedat & Rondon, Reference Seedat and Rondon2021).

Seventh, and in a different vein, stress and physical illness are posited to be the most ancient triggers for depression, which confer adaptive value via their association with inflammatory activity that mobilizes sickness behaviour, conserves energy, and helps fight infection (Raison & Miller, Reference Raison and Miller2017, but see McDade et al., Reference McDade, Hoke, Borja, Adair and Kuzawa2013). Lastly, theorists concur that postpartum depression is an adaptation that responds to low social support, limited resources, and reduced perception of offspring viability (Hagen, Reference Hagen2011; Salmon & Hehman, Reference Salmon, Hehman, Weekes-Shackelford and Shackelford2021), although they do not address the elevated rates of depression in pregnancy.

Underlying all these theories is that depressive symptoms promote adaptation by orchestrating the physical, behavioural, and psychosocial reallocation of limited resources to meet persistent threats to fitness. Applying adaptationist accounts to explain why mood disorders are so much more prevalent among women, and why the rates vary across societies, requires consideration of the exposures, vulnerabilities, and reaction norms driving women’s mental health outcomes. Consistencies in sex/gender configurations of stressors and optimal responses to them will have acted as selection pressures that influenced female vulnerability to mood disorders and shaped norms of reaction to varying conditions. It is likely that the effects of sex differentiated developmental processes themselves have unavoidable yet tolerable impact on vulnerability to depression. A challenge for adaptationist explanations is that the great majority of extant evidence comes from western post-industrial settings. Accordingly, the next section offers a schema of the female life course in non-industrial societies and maps the associated adaptive demands and risks.

4. The female life course in non-industrial societies

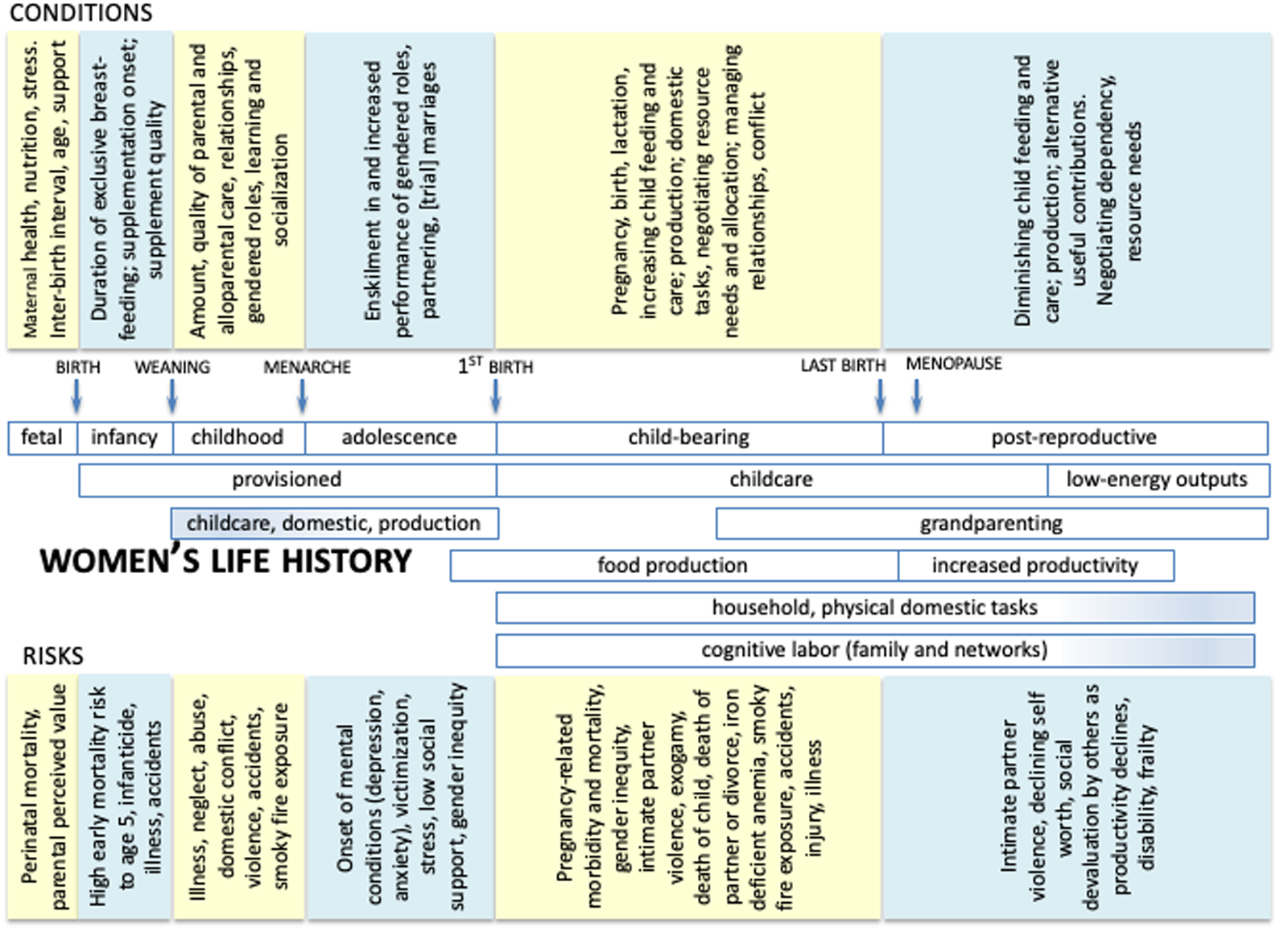

In our quest to probe the evolutionary bases for differential mental health of women, this and the following sections draw on life-history theory and ethnographic evidence from non-industrial societies. A chart of women’s life course (Fig. 1) plots phases established in life history literature. As discussed earlier, outcomes of mood disorder reflect ongoing interactions among biological, experiential, and contextual conditions and begins from the moment of conception (and possibly before in terms of epigenetics). For each period, we outline contents and risks in adaptationist terms.

Figure 1. Schematic timeline of women’s life history in pre-industrial societies.

4.1. Fetal

Fetal development is influenced by factors including maternal macro- and micronutrition, stress levels, and workload as well as maternal age, health, desire for the child, maternal depression, family size, and fear of complications and death in childbirth. If multiparous, interbirth interval and breastfeeding the previous infant during early months of pregnancy can affect the gestating child. Loss of partner, partner’s support, or sudden diminution of resources also can threaten survival and outcome of the fetus. In most non-industrial societies, pregnant women work until the birth of the child.

4.2. Infancy

This period is perilous. Recorded foraging groups averaged 26.8% infant mortality in the first year, and 48.8% child mortality to age 15 (Volk & Atkinson, Reference Volk and Atkinson2013). A survey of extant historical data of non-industrial agrarian populations from 500 bce to 1950 yielded similar averages, 26.9% infant mortality in the first year, and 46.2% child mortality to age 15. However, data from 20 contemporary agriculturalist societies identified an average 20.6% infant mortality in the first year, and 37.6% child mortality to age 15, but these may have benefited from availability of sanitation, medicines, food, education, and laws. The major sources of mortality to age 15 in all these groups was illness, infanticide or abandonment, and accidents. Infanticide or abandonment rates can vary widely: among Hiwi foragers of Venezuela, 12% of female infants died by infanticide (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Hurtado and Walker2007), while some high-caste north Indian groups historically kept almost none of their daughters (Dickemann, Reference Dickemann, Chagnon and Irons1979).

Early mortality threatens loss of reproductive investment from the high maternal costs of pregnancy and lactation, and surely is a matter for maternal anxiety, although mothers may terminate or reduce investment in offspring with poor future prospects. Mothers can increase survivorship by exclusive lactation (Wells, Reference Wells2006), well-timed supplementation with quality foods, good hygiene, and vigilance. Neurologically immature young require substantial cognitive work from mothers to support developmental needs. Daughters may be disadvantaged by gender norms that value sons over daughters, with increased risk to mortality. For instance, among forest-dwelling Ache foragers, F:M survivorship ratio to age 5 was 0.90 (females 74%, males 82%) (Hill & Hurtado, Reference Hill and Hurtado1996), compared to the current global survivorship ratio of 1.13 (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Masquelier, You, Hug, Liu, Sharrow, Rue, Ombao and Alkema2023; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Kyu, Aali, Abbafati, Abbas, Abbasgholizadeh, Abbasi, Abbasian, Abd Elhafeez, Abdelmasseh, Abd-Elsalam, Abdelwahab, Abdollahi, Abdoun, Abdullahi, Abdurehman, Abebe, Abedi, Abedi and Murray2024).

4.3. Childhood

Weaning marks transition to childhood and reliance on provisioning by parents and others. Quality of care and resources affects developmental trajectories. Contexts offering opportunities for observational learning and socialization are important routes to developing social competence and subsistence skills, including domestic skills in girls. During this period, major threats are abuse (physical, emotional, sexual), neglect, illness, violence, and accidents. Selection pressure remains high: over a third of children in non-industrial societies who survive the first year die before reaching age 15.

4.4. Adolescence

The ethnographic literature documents that physical changes of puberty in girls acted as social signals and were closely aligned with the social stage of adolescence (Worthman & Trang, Reference Worthman and Trang2018). Social pressures escalate during adolescence, including risk of rape and victimization. Menarche in non-industrial societies averaged 15–16 years and usually was celebrated ritually. Thereafter, processes of partnering and marriage began in earnest, with pressures of mate competition and conformity to expectations for being a good bridal prospect (demonstrating productivity, domesticity, fecundabilitiy) and, once married, to commence childbearing promptly. Postmenarcheal subfecundity delayed the first birth to age 18 or 19, which could create tremendous pressures on young women where expectations of prompt childbearing prevailed; first partnerings or marriage often were fragile until a child was born.

Psychosocial tasks include building new social cognitive skills, reconfigurations of social relationships, and reconciling with gender roles, expectations, and inequality. Daily survival relies on ‘fitting in’ socially, so maturation of social competence becomes particularly essential as girls mature and move into partnerships and adult roles. Patrilocal exogamy is practiced by a slim majority (53%) of societies in the ethnographic record (Murdock, Reference Murdock1949), disadvantaging the bride from loss of social ties, social capital, local knowledge, and social support, all of which they must rebuild in the new community (Hruschka et al., Reference Hruschka, Munira and Jesmin2023).

4.5. Childbearing

This phase commences with first birth and lasts around 20–25 years during which time women bear the combined energetic and time costs of production (food, household) and reproduction (pregnancy, lactation, childcare, and provisioning). Threats to fitness in this period include maternal morbidity and mortality, child mortality, lack of resources, overload from reduced interbirth interval, and poor child development portending poor future outcomes. Pregnancy is costly and risky. First births commonly are the most difficult and more likely to end in loss. A 9-month gestation requires 70,000 kcal (Butte & King, Reference Butte and King2005), and maternal capacity to process sufficient energy approaches its limit in the third trimester (Thurber et al., Reference Thurber, Dugas, Ocobock, Carlson, Speakman and Pontzer2019). Thereafter, lactation requires 330–500 kcal/day (Kominiarek & Rajan, Reference Kominiarek and Rajan2016). Exclusive breastfeeding for 5 months and partial from 6 to 24 months are rough averages, but mothers must navigate energy intake, energy stores, and labour demands, all of which influence timing and quality of supplementation and future fertility.

Therefore, provisioning by partner, kin, and others play essential roles in assisting mothers to meet all the demands of an increasing number of children plus the pressures for production, domestic tasks, and cognitive labour for dependent young, task management and planning, and relationship maintenance (Kramer, Reference Kramer2010). Because women wean early relative to other apes, provisioning promoted shorter interbirth intervals and thereby increased fertility (Hill & Hurtado, Reference Hill and Hurtado1996; Sear & Coall, Reference Sear and Coall2011). Together with slower development of young and a greatly expanded period of dependency, the burden of childrearing expanded and trade-offs of productivity versus childcare increased (Hurtado et al., Reference Hurtado, Hill, Kaplan and Hurtado1992). Hence, the flows of resources and support across these years is crucial (Hooper et al., Reference Hooper, Gurven, Winking and Kaplan2015). Among Tsimané forager-horticulaturalists, 31% of adults report food anxiety and 85% of women report IPV, largely provoked by conflict over partner disinvestment (Stieglitz et al., Reference Stieglitz, Jaeggi, Weinstein and Lane2014). Men are bigger than women; marital conflict and violence are common threats.

The realities of infant and child mortality imply that mothers must cope with the fear and facts of grief and fitness loss, although presence of at least one relative improves child survival (Sear & Mace, Reference Sear and Mace2008). Indeed, the highest survival chances of Ache children are having a secondary father (Hill & Hurtado, Reference Hill and Hurtado1996). Further, partner loss from death or divorce are disastrous for mothers and children. We know little about the emotional effects of such losses in these settings. To these psychosocial stressors are known risks for mood disorder from smoky fires, iron-deficient anaemia, accidents, injury, and illness.

4.6. Post-reproductive

Women live long after they stop reproducing at around ages 42–45. The post-reproductive period commences with the birth of the last child and can last 20–25 years (Gurven, Reference Gurven, Lemaître and Pavard2024). The key threat to fitness is continued ability to enhance offspring fitness. During this time, mothers continue to care for existing young and, as number of dependent children decreases, actually accelerate production (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Gurven, Winking, Hooper and Stieglitz2010). This apparently counterintuitive behaviour occurs because grandmothers have more time for production and can pivot to intergenerational transfer of support for offspring and grandchildren with resources, childcare and socialization, and information (Hawkes, Reference Hawkes2025). Indeed, their presence and contributions have been found to boost offspring fitness (Lahdenperä et al., Reference Lahdenperä, Lummaa, Helle, Tremblay and Russell2004).

With age, women must cope with diminished capacity and increasing frailty that can threaten their value as grandmothers and to the group as well as erode their feelings of self-worth and meaning in life. Such dysphoria may stimulate grandmothers to pursue low-energy, more sedentary yet valued activities such as weaving, basketry, or food preparation as well as storytelling, childminding, or healing.

5. Eco-evolutionary bases for mood disorder in women

Based on the previous discussions, we return to the question of why mood disorders are more prevalent in females than males. Tensions, competition, and relationships within and between the sexes around reproduction and resources drive evolutionary dynamics shaping fertility, fitness, and social organization (Page et al., Reference Page, Ringen, Koster, Borgerhoff Mulder, Kramer, Shenk, Stieglitz, Starkweather, Ziker, Boyette, Colleran, Moya, Du, Mattison, Greaves, Sum, Liu, Lew-Levy, Kiabiya Ntamboudila and Sear2024; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Hooper, Smith, Jaeggi, Smith, Gavrilets, Zohora, Ziker, Xygalatas, Wroblewski, Wood, Winterhalder, Willführ, Willard, Walker, von Rueden, Voland, Valeggia, Vaitla and Mulder2023). An extensive evolutionary literature attests to these tensions and potential for sexual asymmetries in power and dominance (Chen Zeng et al., Reference Chen Zeng, Cheng and Henrich2022; Davidian et al., Reference Davidian, Surbeck, Lukas, Kappeler and Huchard2022; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Natterson-Horowitz, Mueller and Alfaro2023). A combination of sex dimorphism and its bases, the organization and constraints on production and reproduction, and the conditions they produce generate pressures from risks for conflict and hardship. These arguably provide the bases of selection for vulnerability to depression among females and the forms that it takes. Adaptationist explanations often begin with the observation that mood disorder rises sharply through puberty, but the conditions contributing to risk for onset of mood symptoms and disorder begin in gestation and also have deep evolutionary roots. Consequently, we commence by examining the selective pressures to which females are subject across the lifespan. We then evaluate their potential effect on fitness, and how mood disorder might adaptively counter selection pressures and sustain fitness.

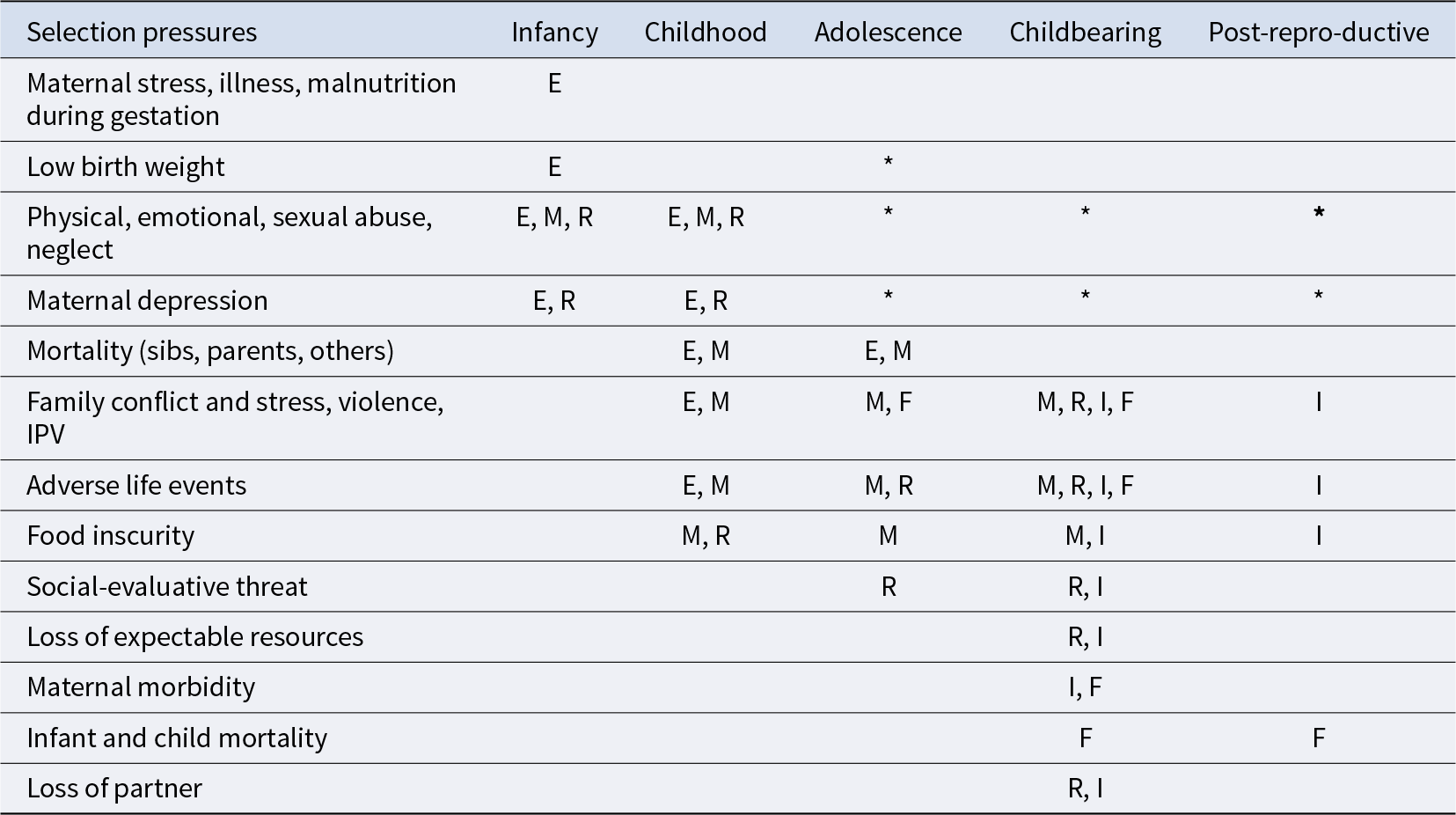

Selection pressures on females commence early on with mortality risk and impact of environmental quality (Table 4). Historically high infant and child mortality poses a strong selection pressure. Child attributes that engage caregiver solicitude, feeding, and protection can mitigate mortality risk. Females repeatedly have been found to be more sensitive than males to adverse events, social conflict, and abuse, experiencing more long-term sequelae from early adverse events (Mengelkoch & Slavich, Reference Mengelkoch and Slavich2024). Most of the selection pressures in Table 4 may be experienced by both sexes but perceived value of the child guides investment in offspring. When a daughter is relatively devalued, exposure to abuse, family conflict, adverse life events, food insecurity, and social-evaluative threat may be more likely or severe. The interaction of greater endogenous sensitivity to negative experiences along with the increased likelihood of experiencing them compounds the stress, conveying strong signals of poor environmental quality and survival threat, consequently engendering greater vulnerability to adversities in girls.

Table 4. Selection pressures from risk factors for mood disorder across the life course

E = environmental quality.

I = threat to ability to invest in grand/offspring.

M = mortality/survival threat.

F = direct loss of fitness.

R = threat to flow of resources.

* = long-term effect on risk.

Psychobehavioural dispositions that mitigate the threats to critical flows of resources and risk for harm are adaptive in these conditions. Indeed, as early as 3 years, daughters add value by helping their commensal group through childcare, domestic tasks, and foraging. Girls in small-scale societies consistently play less and devote more time to productive tasks that benefit mothers, sibs, and others (Kramer, Reference Kramer2010, Reference Kramer2023), thereby enhancing environmental quality and blunting mortality risk. Early exposure to adversity and maternal depression (Fig. 1) leads them to be more stress reactive, socially vigilant, and risk averse, all of which can drive motivation for cooperation and ‘fitting in’. Proactive cooperation by adding value may reduce selection pressures. Contrariwise, conflict (e.g., heavy childcare demands) and adverse conditions (e.g., illness) may prompt costly child signalling to elicit belief in need and investment (Gaffney et al., Reference Gaffney, Hlay, James, Syme, Arnocky, Blackwell, Hodges-Simeon and Hagen2025). Depression in pregnancy and postpartum are widespread (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Worthman, Norwood, le Roux and O’Connor2023); maternal depression during gestation and parenting transmits information about the environment and inculcates cognitive and emotion regulation dispositions to cope with it (Kuzawa & Thayer, Reference Kuzawa and Thayer2011). The affective, cognitive, interpersonal, and behavioural vulnerabilities and dysregulation in children of depressed mothers have been regarded as risks for psychopathology (Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children, 2009) but also might be viewed as adaptations to poor environments.

Onset of puberty alters the array of selection pressures and opens the passage to maturity. Neuroendocrine changes drive transformation of body, brain, affect, and cognition including social sensitivity, self perception, and social relations. Management of all these changes may be aided by symptoms of anxiety and depression, by adaptive strategies of (1) signalling need and eliciting action by self or others; (2) promoting reflection and analytic thinking to work through the complex web of shifting challenges; (3) motivating abandonment of failing strategies to avoid fitness loss; (4) reducing risk-taking and competitiveness; (5) sexually selected interpersonal sensitivity promoting more adaptive behaviour; (6) increasing bargaining power in unfavourable asymmetrical circumstances. As reviewed earlier, there is some evidence to support most of these proposed strategies; likely a combination of them operates in any given circumstance. However, symptoms and impact on quality of life (see Table 1) incur real trade-offs. Costly signals (fatigue, sleep problems, crying, loss of interest, appetite issues) can impede adequate functioning. As strategies, they may work for a while but levy costs over time, including erosion of social support if needed contributions to community life are jeopardized (Gaffney et al., Reference Gaffney, Adams, Syme and Hagen2022).

Maternal stress in utero influences offspring reactivity; low birth weight shifts sensitivity to adversity in adolescence; adversity – particularly abuse and neglect – is a potent risk for mood disorder in girls (Assari et al., Reference Assari, Najand and Donovan2025); and girls are more sensitive to negative experiences, especially social ones, than are boys (McLaughlin, Weissman, et al., Reference McLaughlin, Weissman and Bitrán2019). The advent of neuroendocrine, physical, psychological, and social changes of puberty operates with that history in place. Moreover, individual differences in stress reactivity interact with all these factors. The organizational and activational effects of oestradiol are particularly potent at puberty, unlike for boys who had experienced high levels of androgens early on. These effects are presaged by adrenarche and accompanied by a cascade of central and peripheral agents that effect brain developmental changes including emotion regulation, maturation of executive function, and attention bias to social reward and threat (Sequeira et al., Reference Sequeira, Silk, Jones, Forbes, Hanson, Hallion and Ladouceur2025). Furthermore, stress reactivity interacts with sexual maturation (Gunnar et al., Reference Gunnar, Wewerka, Frenn, Long and Griggs2009).

Heightened risk for mood disorders that commence in adolescence may be perpetuated into adulthood by a range of biological (menstrual cyclicity, pregnancy, birth), psychological (fear of partner loss or death, food insecurity, IPV, child loss, social dependence), and social (dependence and weak social support, social conflict) factors. Drawing from Table 2, likely core symptoms of female depression in small-scale societies include depressed mood, fatigue, sleep problems, appetite issues, crying, suicidal thoughts, general pain, heart issues, headaches, and irritability. In these settings, social isolation is unlikely albeit possible. These symptoms can impair daily function and are readily apparent to partner, children, and others. Factors crucial to essential flow of material and social resources, social relations, and social value and meaning in life depend on the society in which one lives. Hence, subjective well-being across the life course varies widely across societies (Gurven, Kaplan, et al., Reference Gurven, Kaplan, Trumble, Stieglitz, Burger, Lee and Sear2024), although data on mood disorders in non-industrial societies are rare. Tsimané forager-horticulturalists of Bolivia report regularly experiencing depressive symptoms, prevailing among 18% of females and 7% of men (Stieglitz et al., Reference Stieglitz, Schniter, von Rueden, Kaplan and Gurven2015). Despite resource pooling to buffer risk, 31% of adults report food anxiety, particularly among younger adults under age 35 (Stieglitz et al., Reference Stieglitz, Jaeggi, Weinstein and Lane2014). Moreover, depressed affect scores increase from age 20 onwards and are only weakly correlated within individuals over time, which suggests that depressed affect among Tsimané is acute rather than chronic, often linked to need or conflict. Regardless, depressive symptoms in women are more than twice that in males across the lifespan (Gurven, Buoro, et al., Reference Gurven, Buoro, Rodriguez, Sayre, Trumble, Pyhälä, Kaplan, Angelsen, Stieglitz and Reyes-García2024). Among elders, depression is associated with physical disability (higher in women from reproductive burden) and reduced subsistence activity (Stieglitz et al., Reference Stieglitz, Schniter, von Rueden, Kaplan and Gurven2015). In this and virtually all other ethnographic records, we lack good data about adolescent mood disorder.

The adaptive problems women face throughout the life course and the conditions listed in Table 3 favour low mood, the psychological equivalent of physical pain that signals difficulty and may mobilize responses. Hence, mood disorder such as depression or anxiety confers adaptive benefits overall although individuals differ in costs and trade-offs conditioned on circumstances. Notably, exposure to modest levels of adversity is associated with later resilience to stressors (Seery et al., Reference Seery, Holman and Silver2010). Childhood maltreatment, adverse parent–child bonding, and stressful life events have been found to predict different developmental reaction norms for subsequent depression as do combined effects of cumulative stressful experiences (Su et al., Reference Su, D’Arcy, Li, O’Donnell, Caron, Meaney and Meng2022). Hence, timing and type, not only number, of exposures influence phenotypic outcomes. Antecedent risk factors like prenatal stress or early life adversity can shift the slopes or intercepts of reaction norms, altering likelihood that individuals will express depressed mood states in response to environmental conditions (slopes) or in general (intercepts) (Stearns & Koella, Reference Stearns and Koella1986). For example, in our longitudinal sample in North Carolina, the phenotypic response to low birthweight (LBW) increased sensitivity to childhood and adolescent risk exposures, shifting intercepts on the reaction norm of presumed response to reduced birthweight differentiating low from normal birthweight girls (Fig. 2) (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Worthman, Erkanli and Angold2007). Consequently, 30% of LBW girls aged 15 were depressed contrasted with <5% of normal birthweight girls; nonetheless, over 90% of all girls exposed to three or more risk factors were depressed. The ‘reaction norm’ is hypothetical because the contrast involves a population of phenotypes rather than homogeneous genotypes and assumes that gestation conditions exert aggregate effects on correlated complexes of traits (Stearns et al., Reference Stearns, Byars, Govindaraju and Ewbank2010). Importantly, resilience factors such as supportive relationships, affluence, or social cohesion exert moderating effects on the matrix of risk/conflict, resources, and resultant phenotype (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021).

Figure 2. Birthweight, adversity, and depression in girls in the longitudinal Great Smoky Mountains Study, controlling for family psychiatric history. The horizontal arrow indicates marked change in sensitivity to adverse experiences, whereas the vertical arrow illustrates shifts along the reaction norm reflecting the presumed phenotypic responses to adversity that differentiate low from normal birth weight conditions. Birthweight: low ![]() ; normal

; normal ![]() (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Worthman, Erkanli and Angold2007).

(Costello et al., Reference Costello, Worthman, Erkanli and Angold2007).

6. Conclusion, challenges, and future directions

The dominant message from global epidemiology is that women suffer more whereas men die sooner. Sex/gender disparities in mental health form a piece of this puzzle that can be clarified by applying an adaptationist life-history framework. Hunt and Jaeggi (Reference Hunt and Jaeggi2025) have developed the DCIDE framework for systematic appraisal of evolutionary explanations for mental illnesses. It usefully mandates clear definition of the condition to be explained, exclusion of non-adaptive cases, delineation of the course of the condition and associated traits subject to selection, clear characterization of each alternate evolutionary explanation, and then critical evaluation of each for sufficiency to account for the available evidence. Hence, explanations for mood disorder focus on the potential adaptive effects, whereas our review of the many risk factors and life-history conditions that confront women with conflict and adversity amply demonstrate that women may commonly face conditions provoking depression with its potential trade-offs. Indeed, as we have proceeded through these steps, the above discussions show that the preponderance of mood disorder in females may be adaptive overall yet emerges from layered dynamics of a condition which is variable, heterogeneous, and based in an array of adaptive cost–benefit trade-offs. We have traced lines of sex differentiation and sexual selection that influence differential female vulnerability, while we also have seen how social contexts, cultural configurations of gender and related roles, norms, and values interact with sex-related needs and vulnerabilities as they operate across the life course to shape risk for mood disorder in women.

Limitations of this analysis begin with the skewness of research literature dominated by WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) populations (Sanches de Oliveira & Baggs, Reference Sanches de Oliveira and Baggs2023). Global mental health is developing apace including decolonization of mental health research and care. Local not merely global national-level data are being accumulated as expertise, methods, and resources for research are expanding globally (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Zuo and Zhu2025). Another major limitation is paucity of data from non-industrial populations of foraging and small-scale horticultural societies for understanding the range of selective pressures that shaped evolution of sex differences in development and function in those contexts. We furthermore lack sufficient data about outcomes related to mood and mental health in a variety of these settings. Stereotypes regarding sex and gender mark another limitation that cuts across symptoms and syndromes of mental distress and illness. The rise of psychiatry was heavily influenced by established western gender stereotypes including female hysteria. Moreover, cultures vary in configurations of symptomatology and diagnosis (including depression) (Wen et al., Reference Wen, Amir, Clegg, Davis, Dutra, Kline, Lew-Levy, MacGillivray, Pamei, Wang, Xu and Rawlings2025) and have morphed over time (Tasca et al., Reference Tasca, Rapetti, Carta and Fadda2012). Mentioned earlier was exclusion of putative male-typical symptoms from diagnostic inventories for depression (which scale best to women [Table 2]), which may distort our view of gender differences in mood disorder. A related limitation is the wide gulf between dominant market integrated, wage labour, urbanized populations and the different forms that households (multi-adult, multi-generational), childcare (cooperative breeding, alloparenting), and relationships (partnership bonds, emotional ties, loss) may take/have taken in small-scale societies and historic subsistence modes that affect well-being and mental health. Projecting back from present conditions to the evolutionary history of risk for mood disorders and the reasons for contemporary female preponderance is a challenging ongoing project.

In sum, female preponderance for mood disorders emerges as varied across settings and shaped by a range of biological, developmental, experiential, experiential, and sociocultural factors against a backdrop of evolutionary pressures in women’s life history that conferred overall yet variable adaptive benefits. Expansion and diversification of global mental health research with attention to sociocultural and situational conditions, particularly adversity and conflict, will help illuminate and mitigate the high prevalence and burden of mood disorders among women.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to colleagues in the Culture, Mind, and Brain Network with the Foundation for Psychocultural Research.

Author contributions

CMW solely conceived and conducted the work and wrote the article.

Financial support

Author mental health research reported herein was supported by MH57761, MH61584, DA011301, and MH083964-01.

Competing interests

None.

Research transparency and reproducibility

This manuscript does not rely on any data, code, or other resources.