Introduction

Aneuploidy primarily originates during the first meiotic division in oocytes and is a major contributor to implantation failure and developmental abnormalities. The frequency of chromosome segregation errors increases with maternal age, leading to impaired fertilization and embryo viability (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Ma, Zhu and Schultz2008, Hassold and Chiu, Reference Hassold and Chiu1985). This segregation process is regulated by the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which delays cell cycle progression until all kinetochores are properly attached to spindle microtubules and chromosomes are aligned at the metaphase plate (Sun and Kim, Reference Sun and Kim2012; Izawa and Pines, Reference Izawa and Pines2015). Upon SAC inactivation, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) is activated to initiate chromosome segregation (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Barbosa, Nascimento, Faria, Reis and Bousbaa2011). In oocytes from aged females, SAC activity is reduced, diminishing this protective mechanism (Peters, Reference Peters2006; Marangos et al., Reference Marangos, Stevense, Niaka, Lagoudaki, Nabti, Jessberger and Carroll2015). Loss of SAC function can lead to premature sister chromatid separation and chromosomal instability, often resulting in cell death (McGuinness et al., Reference McGuinness, Anger, Kouznetsova, Gil-Bernabé, Helmhart, Kudo, Wuensche, Taylor, Hoog, Novak and Nasmyth2009; Lane et al., Reference Lane, Yun and Jones2012, Jones and Lane, Reference Jones and Lane2013). Recent studies have demonstrated that modulating the SAC–APC/C axis can enhance chromosomal stability. For instance, Vazquez-Diez et al. (Reference Vazquez-Diez, Paim and FitzHarris2019) showed that partial APC/C inhibition decreases chromosome segregation errors in cultured mouse embryos.

Monopolar spindle 1 kinase (Mps1) is a key upstream regulator of the SAC that phosphorylates kinetochore components and suppresses APC/C activity (Musacchio and Salmon, Reference Musacchio and Salmon2007). Reversine, a small-molecule inhibitor of Mps1, disrupts SAC function by preventing Mps1-mediated phosphorylation (Hiruma et al., Reference Hiruma, Koch, Dharadhar, Joosten and Perrakis2016). In early mouse embryos, reversine treatment has been shown to bypass the SAC and induce frequent chromosome segregation errors in blastomeres (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Graham, Van der Aa, Kumar, Theunis, Fernandez Gallardo, Voet and Zernicka-Goetz2016). However, whether reversine induces similar aneuploidy during oocyte maturation remains unclear.

In contrast, proTAME, a cell-permeable prodrug, functions as a reversible inhibitor of APC/C activity. In somatic cells lacking SAC function, treatment with moderate concentrations of proTAME has been shown to prolong mitosis and reduce chromosome segregation errors (Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Sigoillot, Gaur, Choi, Pfaff, Oh, Hathaway, Dimova, Cuny and King2010). Similarly, low-dose APC/C inhibition in mouse embryos extends mitotic duration, providing additional time for proper chromosome alignment and thereby decreasing segregation errors without impairing blastocyst development (Vazquez-Diez et al., Reference Vazquez-Diez, Paim and FitzHarris2019). However, high concentrations of proTAME during mouse oocyte maturation can arrest the first meiotic division (Radonova et al., Reference Radonova, Svobodova, Skultety, Mrkva, Libichova, Stein and Anger2019). Collectively, these findings suggest that low-dose proTAME treatment may help reduce aneuploidy by fine-tuning APC/C activity.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether SAC inhibition by reversine induces aneuploidy during mouse oocyte maturation and to evaluate whether partial APC/C inhibition using proTAME can mitigate such chromosome segregation errors.

Materials and methods

Oocyte collection and in vitro maturation (IVM)

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at Niigata University, Japan (Protocol No. SA01354). Female ICR mouse older than eight weeks were intraperitoneally injected with 10 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG; Asuka Animal Health, Tokyo, Japan) to stimulate follicle development. After 48 h, mouse were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and ovaries were collected. Germinal vesicle (GV)-stage oocytes were isolated from follicles in TYH medium, and oocytes with visible nuclear membranes were selected as GV oocytes. For initial experiments, GV oocytes were cultured in TYH medium supplemented with 0, 5 or 10 nM reversine (Cayman Chemical, MI, USA) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 16 h. Cumulus cells were removed using hyaluronidase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Maturation rates and aneuploidy were assessed via chromosome analysis. In subsequent experiments, GV oocytes were treated with 5 nM reversine for 0, 3, 5 or 7 h, washed, and transferred to TYH medium containing 0, 1, 2.5 or 5 nM proTAME (Boston Biochem, Cambridge, USA) for an additional 16-hour incubation. The effects of proTAME alone were also evaluated by treating oocytes with 2.5 nM proTAME without prior reversine exposure. Additionally, each experiment in Tables 3 to 5 was conducted sequentially, with the design of each subsequent experiment informed by the results of the previous one. Each experimental condition, including control groups, was independently repeated at least three times on separate days using newly collected GV-stage oocytes. For every replicate, oocytes were obtained from different female mouse and cultured under freshly prepared media and identical handling conditions. This biological replication approach was applied consistently across all experiments to ensure reproducibility and to reduce variability caused by batch effects. The number of mouse used for each condition is indicated in parentheses in the tables. To minimize inter-experimental variation, all procedures related to oocyte collection, IVM, reversine and proTAME treatment, and chromosome analysis were rigorously standardized.

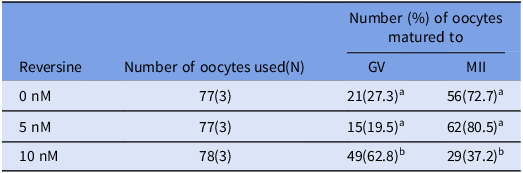

Table 1. Oocyte maturation rates under different concentrations of reversine concentrations

a-b Values with different superscriptions within each column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

GV = germinal vesicle; MII = Metaphase II; N = Number of female mouse.

The number in parentheses indicates the number of independent biological replicates, each performed on separate days using oocytes collected from different mouse.

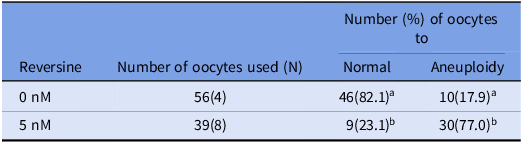

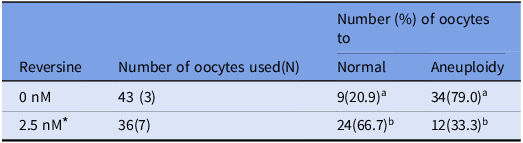

Table 2. Percentage of aneuploidy chromosome numbers in reversine-treated matured mouse oocytes

a-b Values with different superscriptions within each column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

N = Number of female mouse oocytes.

Oocytes for which chromosome number could not be determined were removed.

The number in parentheses indicates the number of independent biological replicates, each performed on separate days using oocytes collected from different mouse.

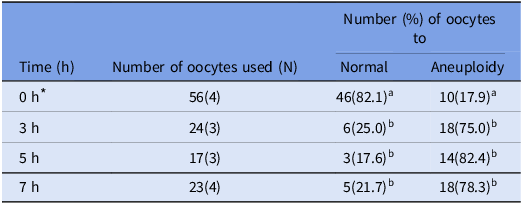

Table 3. Percentage of aneuploid chromosome numbers in matured mouse oocytes after different hours of reversine treatment

a-b Values with different superscriptions within each column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

N = Number of female mouse oocytes.

Oocytes for which chromosome number could not be determined were removed.

* These values correspond to the control group shown in the first row of Table 2.

The number in parentheses indicates the number of independent biological replicates, each performed on separate days using oocytes collected from different mouse.

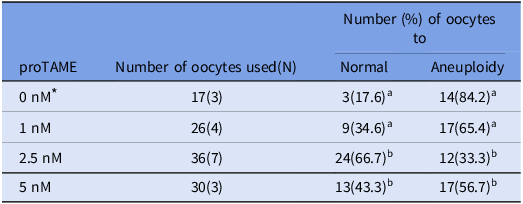

Table 4. Percentage of aneuploid chromosome numbers in matured mouse oocytes after 5 h of reversine treatment followed by different concentrations of proTAME

a-c Values with different superscriptions within each column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

N = Number of female mouse oocytes.

Oocytes for which chromosome number could not be determined were removed.

* These values correspond to the control group shown in the third row of Table 3.

The number in parentheses indicates the number of independent biological replicates, each performed on separate days using oocytes collected from different mouse.

Table 5. Percentage of aneuploid chromosome numbers in matured mouse oocytes with and without 5 h of reversine treatment followed by 2.5 nM proTAME

a-cValues with different superscriptions within each column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

N = Number of female mouse oocytes.

Oocytes for which chromosome number could not be determined were removed.

* These values correspond to the control group shown in the third row of Table 4.

The number in parentheses indicates the number of independent biological replicates, each performed on separate days using oocytes collected from different mouse.

Chromosome specimen preparation by premature chromosome condensation (PCC) method

Metaphase II (MII) oocytes obtained through IVM were treated with protease (Sigma) at room temperature to remove the zona pellucida and polar bodies. The oocytes were then incubated in TYH medium supplemented with 50 nM calyculin A (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 1 hour (Miura et al., Reference Miura, Nakata, Kasai, Nakano, Abe, Tsushima, Ossetrova, Yoshida and Blakely2014).

Following calyculin A treatment, 300 µL of hypotonic solution (1:1 mixture of 30% foetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% sodium chloride (NaCl; Sigma)) was added to a 4-well multidish (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan), and oocytes were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, 30 µL of the first fixative (methanol:acetic acid:hypotonic solution = 1:1:2) was added for initial weak fixation. This was followed by the addition of 300 µL of Carnoy’s fixative (methanol:acetic acid = 3:1) for 10 min.

Oocytes were then placed onto glass slides with a small amount of Carnoy’s fixative. A third fixative (methanol:acetic acid:water = 3:3:1) was dropped onto the oocytes for re-fixation. After air drying, chromosome spreads were stained with 3% Giemsa solution (prepared with Gurr buffer and Giemsa stain; Wako) for 15 min. Slides were rinsed, dried, sealed with Marinol cover glass (Muto Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) and examined under a light microscope.

Oocytes with overlapping, fragmented or poorly spread chromosomes were excluded from analysis. The aberration rate was calculated as the percentage of oocytes exhibiting abnormal chromosome numbers. All chromosome spreads were prepared by the same investigator using a standardized PCC protocol, with consistent exclusion criteria applied across all experimental groups.

Statistical analyses

More than three mouse were used in each treatment. All data are expressed as mean. Data were subjected to one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparison test method (Tables 1,3, 4 and 5) and Student T-test (Table 2) implemented in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Examination of the concentration of reversine during the oocyte maturation process

To determine the optimal concentration of reversine for mouse oocyte maturation, oocytes were cultured with 0 nM, 5 nM or 10 nM reversine (Table 1). The proportion of oocytes remaining at the GV stage was significantly higher in the 10 nM group compared to the other concentrations (p < 0.05). The percentages of oocytes reaching the MII stage were 72.7%, 80.5% and 37.2% for the 0 nM, 5 nM and 10 nM treatments, respectively. The MII maturation rate in the 10 nM group was significantly lower than those observed in the 0 nM and 5 nM groups (p < 0.05). Based on these results, 5 nM reversine was selected for use in subsequent experiments.

Chromosome preparation in mouse matured oocytes

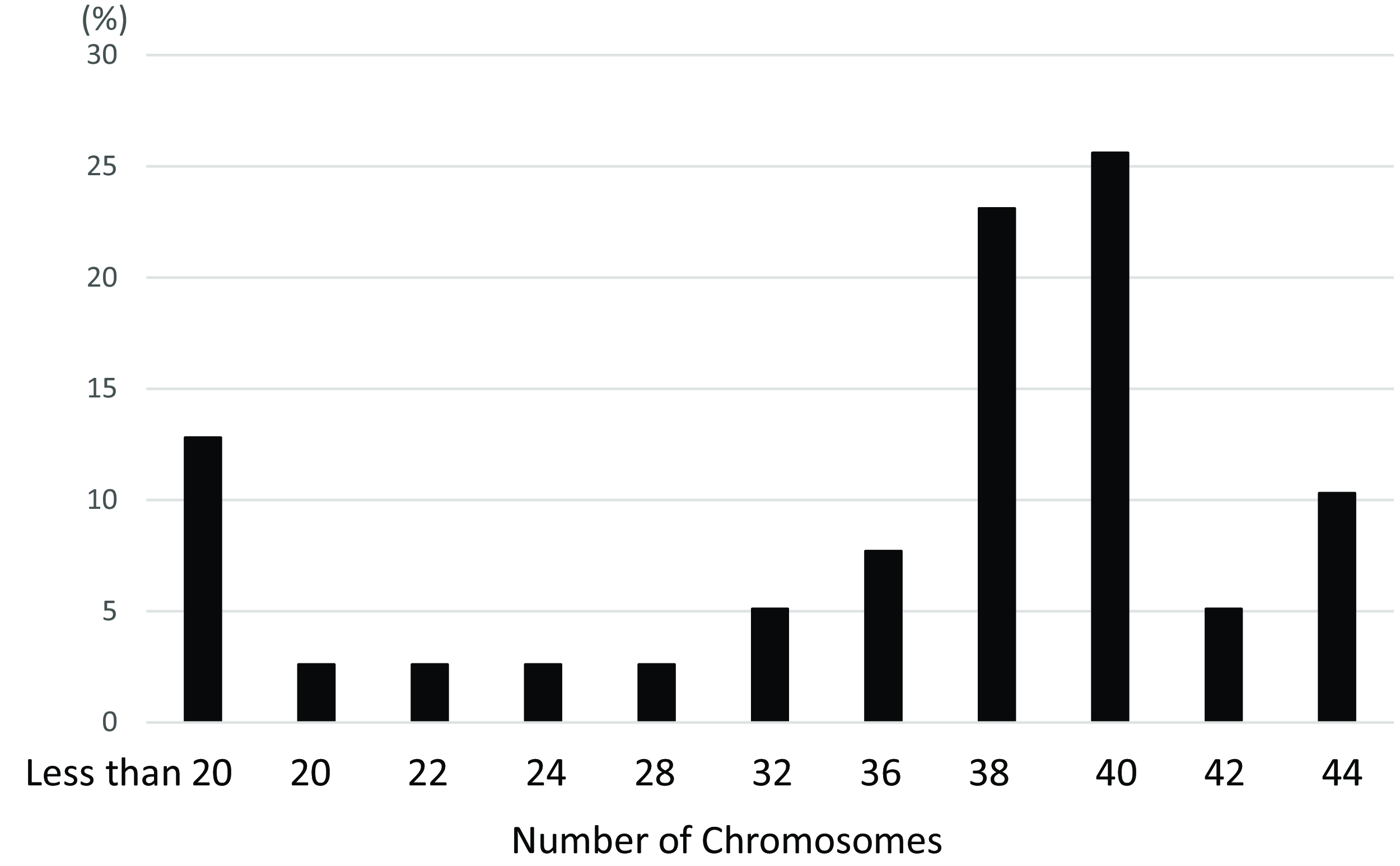

Chromosome spreads were prepared from matured oocytes to assess aneuploidy rates in control and reversine-treated groups (Figure 1A, B). In the control group, 82.1% of oocytes exhibited a normal chromosome number, while 17.9% were aneuploid (Table 2). In contrast, the reversine-treated group showed a significantly higher aneuploidy rate of 77.0%, with only 23.1% of oocytes displaying a normal chromosome count (p < 0.05). Although the normal mouse chromosome number is 2n = 40, the most frequently observed abnormal count was 2n = 38 (detailed distribution shown in Figure 2).

Figure 1. Chromosome spreads from matured mouse oocytes. (A) Control; (B) Reversine-treated. (a) Representative Giemsa-stained chromosome images of matured oocytes; (b) Chromosomes arranged in order of length. Magnification ×1000.

Figure 2. Distribution of chromosome numbers in reversine-treated mouse oocytes.

A small proportion of oocytes were excluded from analysis due to unscorable chromosome spreads. Although the overall number of excluded oocytes was not recorded in detail, exclusion was based on clearly defined morphological criteria and applied uniformly across all treatment groups.

Investigation of the processing time of reversine during the oocyte maturation process

To investigate whether proTAME treatment during mouse oocyte maturation could rescue aneuploidy, we aimed to administer proTAME prior to the onset of chromosome segregation errors. Therefore, we assessed the optimal duration of 5 nM reversine treatment required to induce aneuploidy (Table 3).

During IVM of mouse oocytes, GVBD typically occurs within approximately 2 h (Terret et al., Reference Terret, Wassmann, Waizenegger, Maro, Peters and Verlhac2003), followed by APC/C activation around 6 h later (Radonova et al., Reference Radonova, Svobodova, Skultety, Mrkva, Libichova, Stein and Anger2019). In reversine-treated oocytes, the transition from metaphase to anaphase is shortened by 2–3 h (Kolano et al., Reference Kolano, Brunet, Silk, Cleveland and Verlhac2012). Based on this, we hypothesized that telophase would be reached within 5–6 h in reversine-treated oocytes. Accordingly, oocytes were treated with reversine for 3, 5 or 7 h. After treatment, oocytes were transferred to reversine-free TYH medium, and chromosome spreads were prepared for analysis.

In all treatment groups, the percentage of oocytes exhibiting aneuploidy was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that in the control group, indicating that reversine induced aneuploidy regardless of treatment duration (Table 3, Figure 3). However, the 3-hour treatment group showed a lower aneuploidy rate compared to the 5-hour group. In the 7-hour group, some oocytes had already extruded polar bodies, suggesting that prolonged exposure exceeded the optimal window for potential rescue by proTAME. Based on these observations, a 5-hour reversine treatment was selected for subsequent experiments, considering that the critical transition from metaphase to telophase likely occurs within this timeframe in reversine-treated oocytes.

Figure 3. Chromosome spreads from mouse oocytes treated with reversine for different durations. (A) 3 h; (B) 5 h; (C) 7 h. (a) Representative Giemsa-stained chromosome images of matured oocytes; (b) Chromosomes arranged according to length. Magnification ×1000.

Investigation of proTAME concentration during oocyte maturation process

To evaluate the effect of proTAME on reducing chromosomal aberrations, oocytes were exposed to 5 nM reversine for 5 h during maturation, followed by treatment with varying concentrations of proTAME. Chromosome spreads were prepared and analyzed (Figure 4). In the 1.0 nM proTAME-treated group, the percentage of oocytes with a normal chromosome number showed an increasing tendency compared to the control group (Table 4). Notably, treatment with 2.5 nM proTAME resulted in a significantly higher proportion of oocytes with a normal chromosome number (66.7%) compared to the control (17.6%) (p < 0.05). Additionally, the aneuploidy rate in the 2.5 nM group was significantly lower (33.3%) than that observed in the control group (84.2%) (p < 0.05). However, in the 5.0 nM proTAME-treated group, the aneuploidy rate increased to 56.7%, suggesting a potential concentration-dependent effect at higher proTAME doses, which may contribute to increased chromosomal abnormalities.

Figure 4. Chromosome spreads from mouse oocytes treated with different concentrations of proTAME following 5-hour reversine exposure. (A) 1 nM; (B) 2.5 nM; (C) 5 nM. (a) Representative Giemsa-stained chromosome images of matured oocytes; (b) Chromosomes arranged in order of length. Magnification ×1000.

Investigation of proTAME alone treatment during oocyte maturation process

The effect of proTAME treatment alone, without prior reversine exposure, was evaluated in terms of oocyte maturation rate and aneuploidy rate. Oocytes were treated with 2.5 nM proTAME throughout maturation without the initial 5-hour reversine treatment. The maturation rate to the MII stage was 53.9%. The aneuploidy rate in the 2.5 nM proTAME-only group was 79.0%, which was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than the aneuploidy rate observed in oocytes treated with 5 h of reversine followed by 2.5 nM proTAME (33.3%) (Table 5).

Discussion

Aneuploidy in female gametes increases with maternal age and remains a leading cause of early miscarriage in humans (Gruhn et al., Reference Gruhn, Zielinska, Shukla, Blanshard, Capalbo, Cimadomo, Nikiforov, Chan, Newnham, Vogel, Scarica, Krapchev, Taylor, Kristensen, Cheng, Ernst, Bjørn, Colmorn, Blayney, Elder and Hoffmann2019, Nabti et al., Reference Nabti, Grimes, Sarna, Marangos and Carroll2017). Most cell types safeguard against aneuploidy through the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which coordinates kinetochore–microtubule attachment with cell cycle progression (Musacchio, Reference Musacchio2015). Additionally, partial inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) has been reported to reduce segregation errors in embryos. Despite the clear association between maternal age and fertility decline, the molecular mechanisms underlying age-related deterioration of oocyte quality are not yet fully elucidated (Blengini et al., Reference Blengini, Nguyen, Aboelenain and Schindler2021).

In this study, we investigated whether pharmacological bypass of the SAC via reversine induces aneuploidy during mouse oocyte maturation. We further evaluated whether proTAME, a mild APC/C inhibitor known to prolong mitosis, could mitigate reversine-induced aneuploidy. To determine a reversine concentration that would not impair oocyte maturation, we tested 0 nM, 5 nM and 10 nM. While 10 nM reversine significantly reduced MII maturation rates, no difference was observed between the control and 5 nM groups. Chromosomal analysis using the PCC method revealed abnormal chromosome numbers in both control and 5 nM reversine-treated oocytes; however, the incidence was significantly higher following reversine treatment, confirming its role in inducing aneuploidy during maturation. Based on these findings, 5 nM reversine was selected for subsequent experiments due to its ability to induce aneuploidy without compromising maturation efficiency. Fu et al. (Reference Fu, Cheng, Hou and Zhu2014) demonstrated that oocytes collected from young CD-1 mouse (6 weeks old) exhibited a baseline aneuploidy rate of 10% following superovulation and IVM. Importantly, it is well established that IVM conditions can further increase chromosomal instability compared to in vivo maturation. Although Fu et al. focused on in vivo matured oocytes, their findings highlight that even under optimal conditions, young CD-1 mouse display a measurable level of aneuploidy. This observation is consistent with other studies showing that MII oocytes from young CD-1 mice (6 weeks old) exhibit an aneuploidy rate exceeding 14%, indicating the presence of a background level of aneuploidy (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Li, Zhu, Zhou, Li, Lee and Shen2023). This supports the observation that a background rate of aneuploidy exists in IVM oocytes even from young CD-1 mice. IVM is known to impose additional stress on spindle organization and chromosome segregation, often leading to increased aneuploidy compared to in vivo matured oocytes (Sanfins et al., Reference Sanfins, Lee, Plancha, Overstrom and Albertini2003; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhao, Li, Yu and Qiao2014). Furthermore, extended in vitro culture durations can mimic aspects of post-ovulatory aging, which has been shown to impair spindle integrity and increase segregation errors (Sugano et al., Reference Sugano, Yazawa, Takino, Niimura and Yamashiro2016). These factors may contribute to the slightly elevated background aneuploidy observed in our control group. Given that our study employed extended IVM conditions, it is reasonable to observe a slightly higher background aneuploidy rate. The IVM process itself is known to impose additional stress on oocyte spindle dynamics and chromosome segregation, contributing to elevated aneuploidy rates even in oocytes derived from young mouse.

Our data demonstrated that treatment with 2.5 nM proTAME following 5 h of reversine exposure significantly reduced the incidence of aneuploidy compared to both 1.0 nM and 5.0 nM proTAME treatments, indicating a partial rescue of chromosome segregation errors during oocyte maturation. Previous studies have shown that culturing embryos from the 2-cell stage in varying concentrations of proTAME – a cell-permeable APC/C inhibitor – affects developmental outcomes. Higher concentrations inhibited progression to the blastocyst stage, whereas lower concentrations permitted normal development (Vazquez-Diez et al., Reference Vazquez-Diez, Paim and FitzHarris2019). These findings align with our results and support the concept that mild pharmacological inhibition of APC/C can prolong mitosis, providing additional time for proper chromosome alignment prior to anaphase, thereby reducing segregation errors. In contrast, proTAME treatment alone, without prior reversine exposure, led to a decreased maturation rate and a significantly increased aneuploidy rate compared to the sequential reversine–proTAME treatment. This suggests that APC/C inhibition by proTAME may be beneficial in the context of SAC dysfunction but detrimental to normal oocyte maturation processes.

The differential effects observed across proTAME concentrations likely reflect the balance between sufficient APC/C inhibition to delay cell cycle progression and excessive inhibition that impairs meiotic completion. Specifically, weak inhibition at 1.0 nM may have failed to prevent premature telophase entry, resulting in increased aneuploidy. Conversely, 5.0 nM proTAME likely exerted excessive inhibition, hindering meiotic progression. Our findings indicate that 2.5 nM represents an optimal concentration, effectively reducing chromosome segregation errors without compromising maturation. These results further support the potential of precisely timed and dosed APC/C inhibition to mitigate aneuploidy risk by extending the window for accurate chromosome alignment during oocyte maturation. Beyond the mechanistic insights into SAC–APC/C regulation, our findings may contribute to the development of novel strategies for assessing and improving oocyte quality in assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Aneuploidy remains a leading cause of implantation failure and miscarriage, particularly in oocytes from older women or those subjected to extended in vitro culture. The pharmacological modulation of SAC–APC/C activity, as demonstrated in this study, offers a potential approach to selectively suppress premature APC/C activation and reduce chromosome segregation errors.

In this study, the control group was consistently cultured for 16 h under all experimental conditions. As the primary aim of our investigation was not to evaluate the effect of culture duration per se, but to assess how pharmacological modulation of APC/C activity influences chromosome segregation, we did not include a 21-hour untreated control group. Furthermore, based on previous findings and biological rationale, we consider that extending IVM from 16 to 21 h under control conditions is unlikely to significantly affect aneuploidy rates. Therefore, a uniform 16-hour control was used across all experimental groups to maintain clarity in interpreting the treatment-dependent effects. We acknowledge, however, that this choice represents a potential limitation of the study, and our conclusions should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

One limitation of this study is that not all treatment groups were conducted concurrently. Instead, a sequential design was employed, in which each experiment was guided by the results of the preceding one. Although control groups were included in each experiment and all protocols were strictly standardized, the lack of concurrently treated internal controls may affect the statistical comparability of some experimental groups. We acknowledge this limitation and have interpreted our findings with appropriate caution.

In summary, this study demonstrates that proTAME treatment can effectively reduce aneuploidy induced by SAC inhibition with reversine, thereby mitigating chromosome segregation errors during the first meiotic division in mouse oocytes. These findings suggest that fine-tuned pharmacological regulation of APC/C activity may offer a strategy to improve oocyte quality by minimizing meiotic errors. Future studies using oocytes from aged mouse – where aneuploidy is more prevalent – could provide further insight into the therapeutic potential of this approach. Moreover, investigating post-treatment developmental outcomes, including fertilization success and embryo viability, will be essential for assessing the feasibility of complete aneuploidy rescue. While the present study was performed in mouse, the core concept of temporally regulating meiotic progression through APC/C modulation may be applicable to human in vitro maturation (IVM) protocols, provided that rigorous safety validations are in place. Taken together, our findings could contribute to the development of new strategies to assess and enhance oocyte quality, with promising implications for fertility preservation and assisted reproductive technologies.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by the KAKENHI grants B (22H02496) and Fostering Joint International Research B (19KK0176) from the JSPS. It was also supported by the Environmental Radioactivity Research Network Center of Hirosaki and Tsukuba University (F22-50).