Introduction

The year 2022 was a politically dense one for the Italian political system. The three main happenings were the re-election of President Sergio Mattarella in January, the resignation of Mario Draghi as Prime Minister in July and, finally, the snap elections in late September. The victory of the centre-right coalition, and in particular the result obtained by Brothers of Italy/Fratelli d'Italia, a far-right party, caught the attention of the international press, wondering whether Italy was drifting towards more extreme conservative positions. This also raised some concerns about the relationship of Italy with EU institutions. The electoral outcome appears to be primarily due to the re-distribution of centre-right voters’ preferences across the parties traditionally composing this coalition, and to a highly fragmented center-left coalition, which did not manage to form a unified front.

Election report

Presidential elections

In Italy, the President of the Republic is elected for a seven-year mandate and it requires a qualified majority of two-thirds of Parliament. As the president elected in 2015, Sergio Mattarella, was approaching the end of his mandate, the political situation in Italy was marked by two main features. First, the government in office was a technocratic one (hence lacking a traditional political majority), with Mario Draghi as Prime Minister. Second, this government was still dealing with challenging circumstances due to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the vaccination campaign and the management of relations with the European Union regarding the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). As Fusaro (Reference Fusaro2023) noticed, ‘Presidential election outcomes have always been determined by the governing majority or variations thereof, or by alternative majorities that have had to be constructed—meaning that they have always been determined by precise political strategies made possible by the distribution of power in Parliament’ (p. 143). However, when the end of Sergio Mattarella's mandate started to approach, the Italian political landscape was highly fragmented.

Draghi's government, which had been in office since February 2021, was initially formed with the mandate of managing the COVID-19 emergency as well as the financial aid coming from the NextGenerationEU Recovery Fund (Russo & Valbruzzi Reference Russo and Valbruzzi2022). All political parties participated in this government, with the only exception of Fratelli d'Italia, which was the only party remaining in opposition (Russo et al. Reference Russo, Sandri and Seddone2022). Paradoxically, such a large majority contributed to increase fragmentation and polarisation across parties despite their involvement in government, as they needed to differentiate themselves in order to send signals to their voters (see Russo & Valbruzzi Reference Russo and Valbruzzi2022). One of the most evident elements of this fragmentation was that the centre-right coalition, as traditionally composed since 1993, was split, with League/Lega per Salvini Premier and Go Italy/Forza Italia being part of the government and Fratelli d'Italia being (the only one) out. Yet, centre-left parties were also facing challenges in terms of (future) alliances and ongoing divisions, which became manifest during the election campaign (see the section on Political Party Report).

In such a fragmented political landscape, finding an agreement among parties about the new name for the highest Italian office was particularly challenging. When asked, president Mattarella publicly excluded a second mandate. A second mandate is not prohibited by the Constitution, yet only his predecessor, Giorgio Napolitano, was elected a second time in 2013 (Ignazi Reference Ignazi2014) and stayed in office only for two years until 2015, when Mattarella was elected (Ignazi Reference Ignazi2016).

Some other high-profile names were considered, including in particular Mario Draghi. However, parties considered that it was essential that Draghi remained in the Prime Minister's office (Fusaro Reference Fusaro2023). Hence, after eight rounds of voting, Sergio Mattarella was re-elected for a second mandate on 29 January, with 759 votes (the second largest vote share ever, only second to the beloved figure of Sandro Pertini).

Parliamentary elections

Parliamentary elections took place on 25 September, following the toppling of Mario Draghi's government. As previously mentioned, the incumbent government included all Italian political parties but Fratelli d'Italia. The political context in which Draghi's government fell was very different from that of January, when Draghi was deemed as so indispensable as Prime Minister that his name could not be considered for the President of Republic office, despite his high profile. As the pandemic emergency declined (also due to the vaccination campaign being solidly set off), political parties felt the saliency of this topic drop. Moreover—given that the legislature, in any case, would be coming to its end in early 2023—parties in government started to undertake initiatives aimed to differentiate each other in a logic of permanent campaign. This dynamic was especially observable for the Five Stars Movement/Movimento 5 Stelle and Lega (for a detailed overview, see Russo & Vegetti Reference Russo and Vegetti2023), which were suffering from decreasing support in polls and thus needed to (re)mobilise their supporters in the run-up to the upcoming elections. The crisis was formally initiated by the Movimento 5 Stelle, although not with the specific purpose of toppling the government. Indeed, the government had to approve a legislative decree featuring some measures the Movimento 5 Stelle opposed (such as sending weapons to Ukraine, building an incinerator in Rome and adjustments to the minimum income guaranteed by the state, which was initially introduced by them during the yellow-green government experience). This decree was linked to a vote of confidence. Thus, the Movimento 5 Stelle decided to signal its discontent with some aspects of the decree by voting against it per se but still casting a vote of confidence for the government. This is, however, only possible in the Chamber of Deputies but not in the Senate, where both parts (content and confidence) are tied together. Yet, the Movimento 5 Stelle decided to vote against both. Thus, fulfilling a previous promise that he would resign if even just one government party cast a vote of no confidence, the Prime Minister announced his resignation. The President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, rejected this resignation, asking Mario Draghi to go back to the Senate. On 20 July, the Prime Minister addressed the parties with a speech depicting the ‘gradual crumbling of the majority’ with regard to reforms such as the ones affecting the real estate registry and the beach public concessions (both opposed by the centre-right parties) and he stated that ‘Italy does not need superficial trust, which vanishes in front of inconvenient measures’.Footnote 1 Mario Draghi asked for a vote of confidence based on this speech. The centre-left parties (The Democratic Party/Partito Democratico and Free and Equals/Liberi e Uguali), along with the centre parties, voted in support. The centre-right Lega and Forza Italia abstained, and the Movimento 5 Stelle did the same,Footnote 2 thus leading to the end of Draghi's government, and determining the need for a new general election.

For the first time since the Italian Constitution exists in its current form (hence since after the Second World War), parliamentary elections were held in late September. Thus far, that had been avoided because of the time needed for the drafting and discussion in Parliament of the national budget law,which needs to be approved by the end of the year.

Besides the date, the second element of novelty of the 2022 elections was that, for the first time, the existing electoral law (the Rosato Law—named after the MP who wrote it and also known as Rosatellum) was used to elect a reduced Parliament resulting from the 2020 constitutional referendum, which set the number of deputies at 400 and of senators at 200 (Russo et al. Reference Russo, Seddone and Sandri2021).

The Rosato Law establishes that 61 per cent of seats are allocated using a proportional system and 37 per cent are allocated using a plurality system, with the remaining 2 per cent referred to votes casted by Italians living abroad (these are allocated using a proportional system). The threshold to enter Parliament is 3 per cent for single parties and 10 per cent for coalitions. As all preceding electoral laws used from 1993 onwards (Mattarellum 1993; Porcellum 2005; Italicum 2015), the Rosato Law establishes a mixed electoral system featuring both a proportional and a plurality component. According to the new, reduced number of seats, the plurality component was accountable for the election of 147 deputies and 74 senators, and the proportional component for 245 deputies and 122 senators. As noted by Russo and Vegetti (Reference Russo and Vegetti2023), the aim of this—and preceding electoral laws as well—was to facilitate alliances and coalitions and to steer the system towards a two-poles structure that would ensure the country a higher degree of stability.

When the electoral campaign started, it soon became clear that competition was not structured around two but four main actors: the centre-left pole (composed by Partito Democratico and a Green-Left Alliance/Alleanza Verdi-Sinistra, plus two minor centre parties), the centre-right pole (as for previous elections composed by Forza Italia, Lega and Fratelli d'Italia, which re-joined its traditional allies after staying at the opposition), the Movimento 5 Stelle (which decided to run by itself) and a new party alliance called the Third Pole/ Terzo Polo (composed by two centre-left parties, Action/Azione and Italy Alive/Italia Viva). The secretary of the Partito Democratico, Enrico Letta, tried to enlarge the centre-left coalition by including the Movimento 5 Stelle and the Terzo Polo but to no avail (for a more detailed overview, see Russo & Vegetti Reference Russo and Vegetti2023).

Since the end of Draghi's government, the result of the upcoming elections could largely be predicted. The centre-right dominated the polls, primarily due to the impressive growth of Fratelli d'Italia, the only party that did not support the last government (Russo & Valbruzzi Reference Russo and Valbruzzi2022). Adding to this, the non-right parties were spread across three different coalitions. Nevertheless, some politicians implied that the reduced Parliament, in combination with the Rosatellum, was (at least partly) responsible for the foretold victory of the centre-right.

The predictable victory of Fratelli d'Italia created numerous tensions within the centre-right coalition, where Berlusconi and Salvini—once leading frontrunners—showed some resistance to recognising Meloni's leadership role. At the same time, the certainty of an easy victory forced the leader of Fratelli d'Italia to seek an ideological (re)positioning, at least on international policy issues. In particular, the Eurosceptic stances that characterised the party in the past were smoothed out to reassure the European institutions and international partners. In the same vein, Meloni reiterated her adherence to the United States and NATO positions on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which, incidentally, represented a quite controversial issue for her internal allies. On the other hand, the failure of the centre-left camp to forge a broad coalition led to a divisive and confrontational election campaign among parties that were (or tried to be) allies. Given their need to gain visibility and electoral strength, the Terzo Polo targeted the Partito Democratico with negative campaigning in an attempt to attract moderate voters. Likewise, the Movimento 5 Stelle campaigned on the issues of basic income and minimum wage, with the precise aim of undermining the Partito Democratico’s ownership of labour-related issues and increasing their support among segments of left-wing voters. For the Partito Democratico, therefore, the only option left was to run an electoral campaign emphasising the continuity of the Draghi government's experience—which continued to enjoy remarkable support according to polls. Moreover, the Partito Democratico stressed its ideological identity in order to mobilise electors against the risk of an extremist drift in the event of a victory by the center-right coalition, with Fratelli d'Italia at its helm.

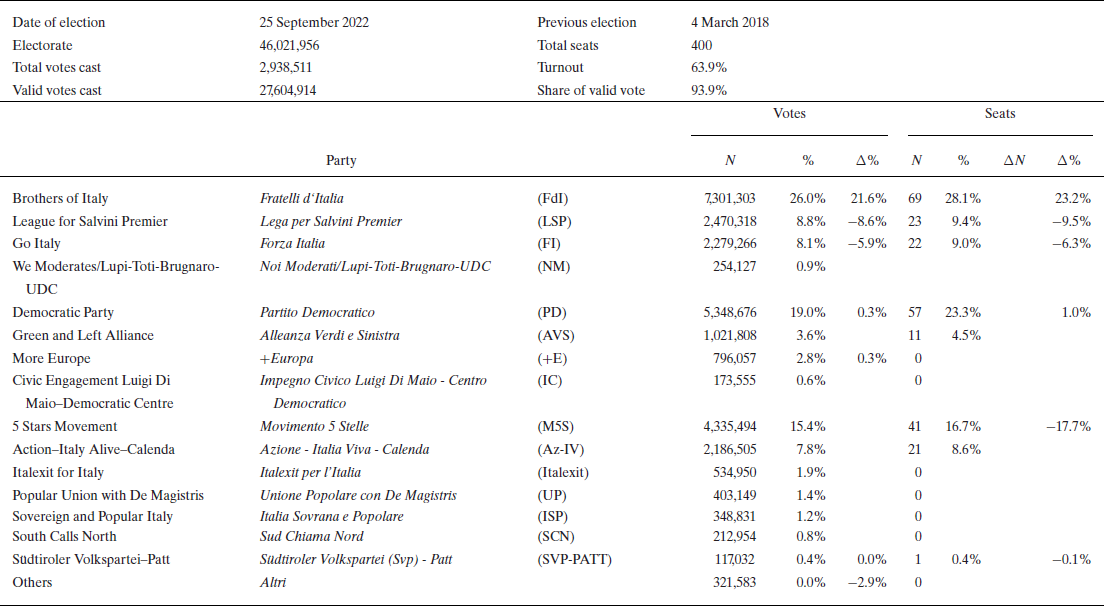

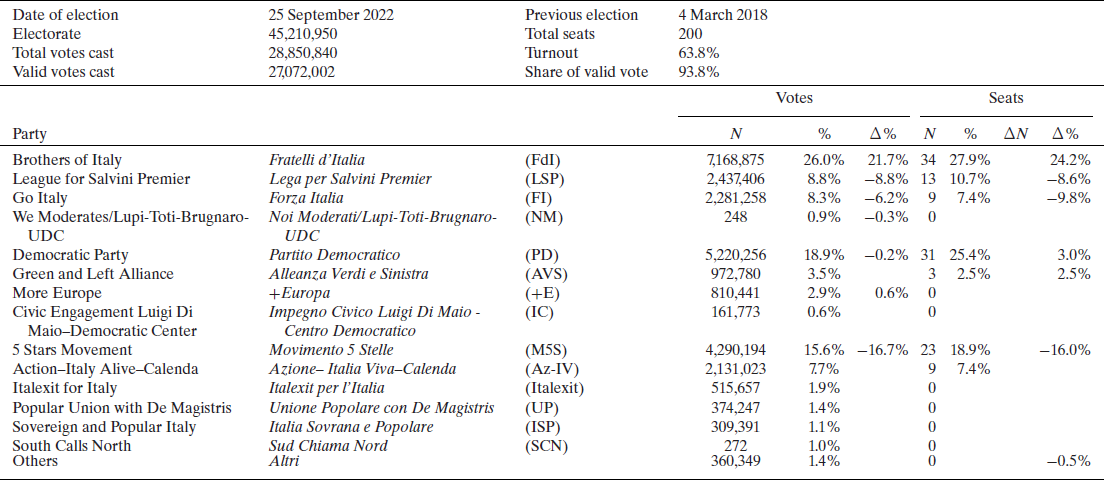

As Tables 1 and 2 show, the centre-right won with an ample majority, although some distortions due to the application of the electoral law are evident. In fact, considering the Chamber of Deputies, the centre-right coalition obtained 44 per cent of votes, which translated into 59 per cent (237) of available seats. The centre-left received 26 per cent of valid votes and 21 per cent of seats (84) and the 5 Stars Movement (M5S), 15 per cent of votes and 13 per cent of seats. As Russo and Vegetti (Reference Russo and Vegetti2023) show, these results are not due to the reduction of seats available (and, hence, the existence of larger electoral districts) but to the growth of Fratelli d'Italia (mainly at the expense of Lega and Forza Italia, reflecting a redistribution of votes within the centre-right coalition) and the fragmentation of the non-right political forces across three coalitions.

Table 1. Elections to the lower house of the Parliament (Camera dei Deputati) in Italy in 2022

Notes:

1. Results refer to the proportional vote quota (245 seats out of 400).

2. Data do not include the region Valle d'Aosta and Foreign district votes.

3. The comparison of the absolute number of seats obtained in 2018 general election is not reported due to the reduction of the total number of MPs according to Constitutional Reform (see Russo et al. Reference Russo, Seddone and Sandri2021).

4. We Moderates/Lupi-Toti-Brugnaro-UDC, Civic Engagement Luigi Di Maio–Democratic Centre and South Calls North are included because they won at least one seat under in a single-member district.

5. Officially, the Democratic Party ran with the following tag: Partito democratico–Italia Democratica e Progressista. It included (especially in single-member districts) candidates from the former party Liberi e Uguali/Articolo 1 (Free and Equals/Article 1), which, in 2018, had received 3.4% and 14 seats in proportional. The ∆% does not include this share of votes gained in 2018; it has been calculated only on PD votes.

6. The Südtiroler Volkspartei is a regional party running in Trentino Alto-Adige/South Tyrol. They also got two seats in single-member districts.

Source: Ministero degli interni (2023) (https://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it/).

Table 2. Elections to the upper house of the Parliament (Senato) in Italy in 2022

Notes:

1. Results refer to the proportional vote quota (122 seats out of 200).

2. Data do not include the region Valle d'Aosta and Foreign district votes.

3. The comparison of the absolute number of seats obtained in 2018 general election is not reported due to the reduction of the total number of MPs according to Constitutional Reform (see Russo et al. Reference Russo, Seddone and Sandri2021)

4. Officially, the Democratic Party ran with the following tag: Partito democratico–Italia Democratica e Progressista. It included (especially in single-member districts) candidates from the former party Liberi e Uguali/Articolo 1 (Free and Equals/Article 1), which, in 2018, had received 3.3% and four seats in proportional. The ∆% does not include this share of votes gained in 2018, it has been calculated only on PD votes.

Source: Ministero degli interni (2023) (https://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it/).

The victory of the centre-right coalition, with Fratelli d'Italia winning the most votes, made it possible for the leader of this party, Giorgia Meloni, to become the first woman Prime Minister in Italian history.

Regional elections

The only region holding elections in 2022 was Sicily. The centre-right coalition achieved a significant victory in the Sicilian regional election held on 25 September, the same day of the parliamentary elections, confirming their success in the previous election in 2017. Renato Schifani, the former president of the Senate, became the new regional president, succeeding Nello Musumeci, who did not run again due to internal conflicts within the centre-right coalition. Although Schifani's victory was clear-cut, it should be noticed that turnout was relatively low, despite the potential for increased mobilisation due to the simultaneous general elections taking place: less than 50 per cent of eligible voters participated in the election.

The centre-left candidate was Caterina Chinnici, while Nunzio di Paola represented the Five Star Movement. However, both Chinnici and di Paola were surpassed by an outsider candidate, Cateno De Luca, the former mayor of Messina, who secured second place with 24 per cent of the vote. The role of former Prime Minister Conte in the fall of Draghi's government, in which the Partito Democratico was a loyal partner, made an alliance between Partito Democratico and Movimento 5 Stelle impossible in Sicily (Emanuele Reference Emanuele2023).

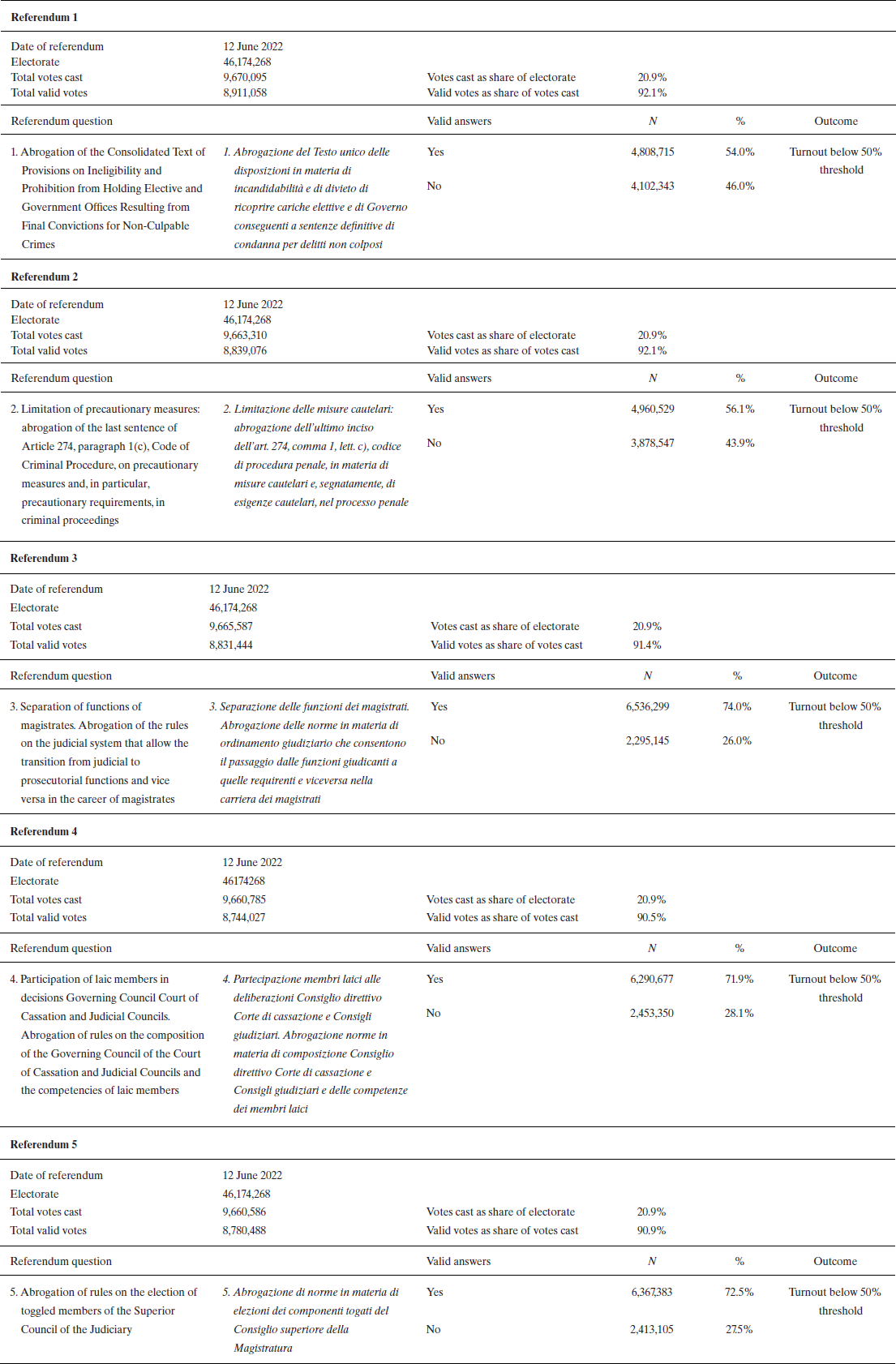

Referendum

In 2022, citizens were also called to vote on five referendum questions on the topic of justice reform. These were five referendum questions addressing diverse aspects of the Italian Judicial system concerning issues about: (a) the abrogation of the rules on the automatic ‘incandidability’ (inability to be appointed as candidate), ineligibility and debarring of those who have been definitively convicted of certain types of crimes, such as mafia involvement, terrorism or crimes against the public administration; (b) the limitation of precautionary measures for some crimes with lesser penalties and for the crime of illicit party financing; (c) the separation of functions of judicial officers, proposing the repeal of the rules allowing a magistrate to switch from the functions of a prosecutor to those of a judge, and vice versa; (d) the procedures for the evaluation of magistrates, allowing the participation of lay members—lawyers and professors—of the Council of the Court of Cassation (Consiglio direttivo della Corte di Cassazione) and Judiciary Councils (Consigli giudiziari); and (e) the rules for the selection of candidates for the High Council of the Judiciary (Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura).Footnote 3

The Lega was the primary party behind the promotion of these referenda. However, the low turnout resulted in the failure of all five referendum questions. The low participation rate was not surprising, as it is in line with a general trend of decreasing mobilisation around referenda (with the sole exception of the 2020 constitutional referendum). Yet, the low turnout can also be interpreted as a sign of the Lega’s weakened capacity to mobilise voters, despite the party engagement on this specific issue. Table 3 presents the result per each referendum question.

Table 3. Results of five referenda held on 12 June 2022 in Italy

Source: Ministero degli interni (2023) (https://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it/).

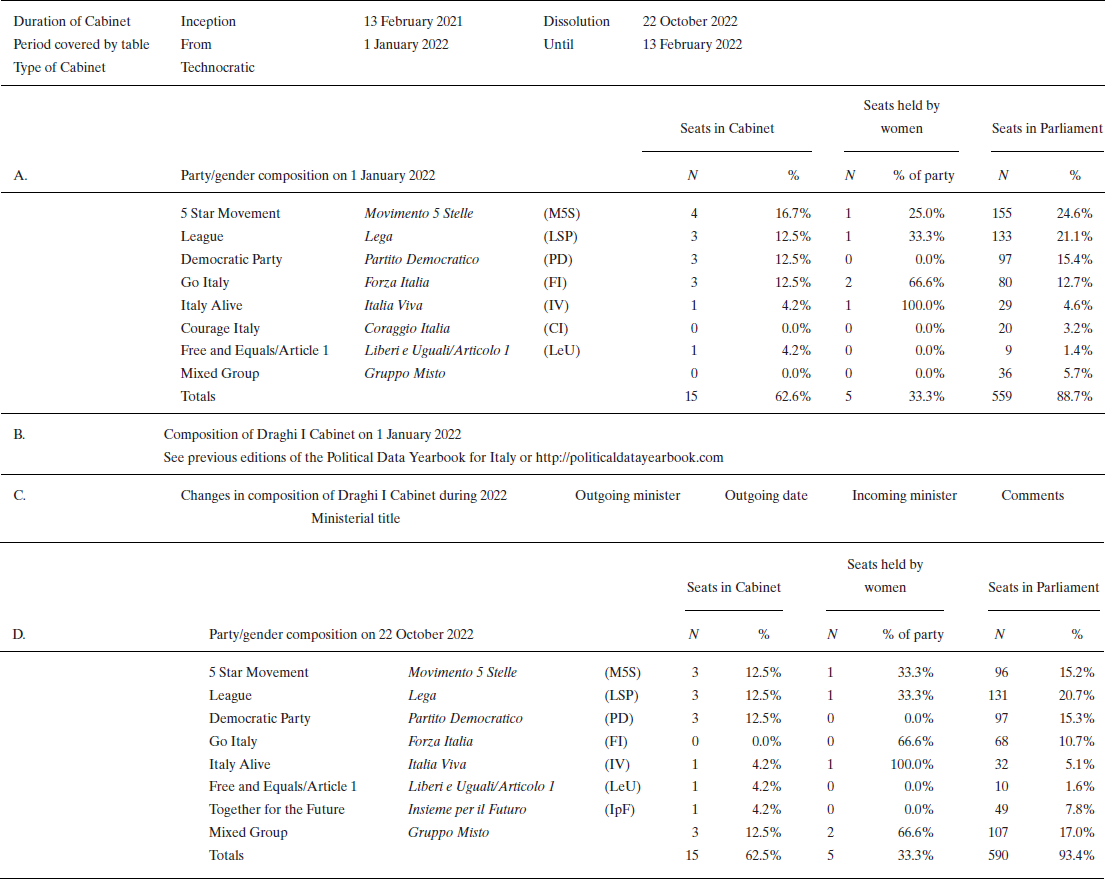

Cabinet report

Draghi's resignation in late July came rather unexpectedly as underlined above. Unlike the government crisis in summer 2019 and winter 2021 (see Russo et al. Reference Russo, Sandri and Seddone2022), indeed, there were no previous significant parliamentary events or changes within the government lineup that would have foreshadowed such an early end for the technocratic government. Notwithstanding the relatively positive results of the Draghi I Cabinet in managing the energy crisis and the related economic crisis, as well as the rollout of the NRRP, the government did not manage to achieve several important goals because of a lack of consensus among the governing parties. The reform of the judicial system was aborted. Draghi played an important role in the energy crisis and the negotiations at the European level on the control of gas prices in the summer of 2022 and participated in high-level meetings with the Ukrainian President Zelensky together with the German Chancellor and the French President. However, overall, the impact of the Italian government in the international political arena was limited and came to a halt, together with any significant debate about potential institutional reforms, in the fall of 2022, while the new government was being formed.

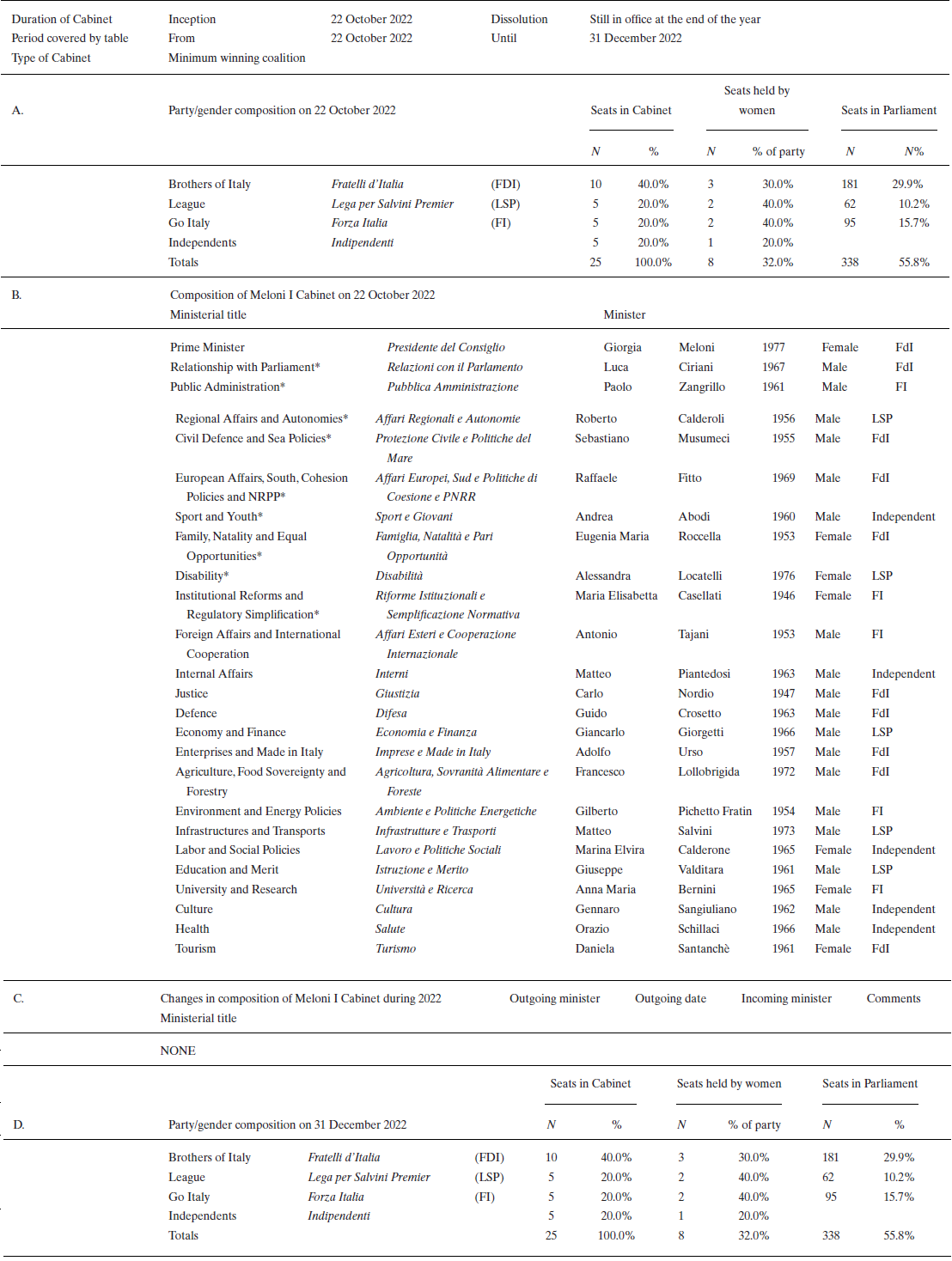

The new government that took office in October 2022 was markedly distinct in several respects. Fratelli d'Italia’s extraordinary electoral results enabled Giorgia Meloni to form a Cabinet relying on a vast parliamentary (hence political united) majority, albeit less impressive in the Senate. She established an exceptionally extensive team of government officials. The Prime Minister was accompanied by 24 ministers and 40 undersecretaries, thus reaching the maximum number of government members allowed by law. In this respect, it should be noticed that nine ministers are ‘senza portafoglio’ (without portfolio), meaning that they act on the direct delegation of the Prime Minister. This fact alone signals the intent of the major coalition partner to maintain control in order to contain any potential source of conflict from its allies while limiting their visibility. Likewise, if it is not surprising that Fratelli d'Italia holds the lead of the most important departments, it is worth mentioning that Meloni has strategically let down her allies’ demands for some crucial ministers. Indeed, Forza Italia was denied its request of leading the Minister of Health, while Salvini had to abandon his hopes of returning to the helm of the Ministry of the Interior, a role he had held during the coalition government with the Movimento 5 Stelle. In both cases, Giorgia Meloni entrusted these tasks to independents, albeit close to the centre-right political area. This choice is strategic and aimed at preventing government allies from taking ownership of these crucial agenda items.

Information on the composition of the Draghi and Meloni cabinets in 2022 can be found in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Draghi I in Italy in 2022

Notes:

1. See Russo et al. (Reference Russo, Sandri and Seddone2022) for the reasons to classify the Draghi Cabinet as technocratic.

2. Missing ministers were technocrats.

3. Formally, Renato Brunetta (21 July), Mariastella Gelmini (21 July) and Mara Carfagna (27 July) left Forza Italia parliamentary group to join the Mixed Group, but they maintained their role within the government . Likewise, Luigi Di Maio also maintained his role within the Cabinet, even if on 21 June 2022 he left the M5S to found a new political party named ‘Together for the Futur’ (Insieme per il Futuro/IpF).

Source: Governo Italiano. Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri (2022) (www.governo.it/it).

Table 5. Cabinet composition of Meloni I in Italy in 2022

Note: Ministers with * were ministers without portfolio.

Source: Governo Italiano. Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri (2022) (https://www.governo.it/it).

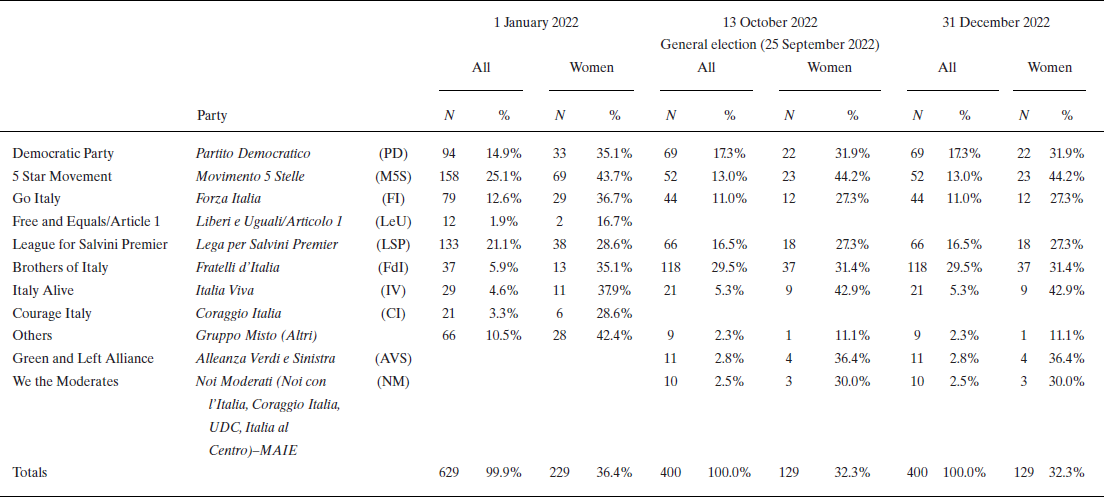

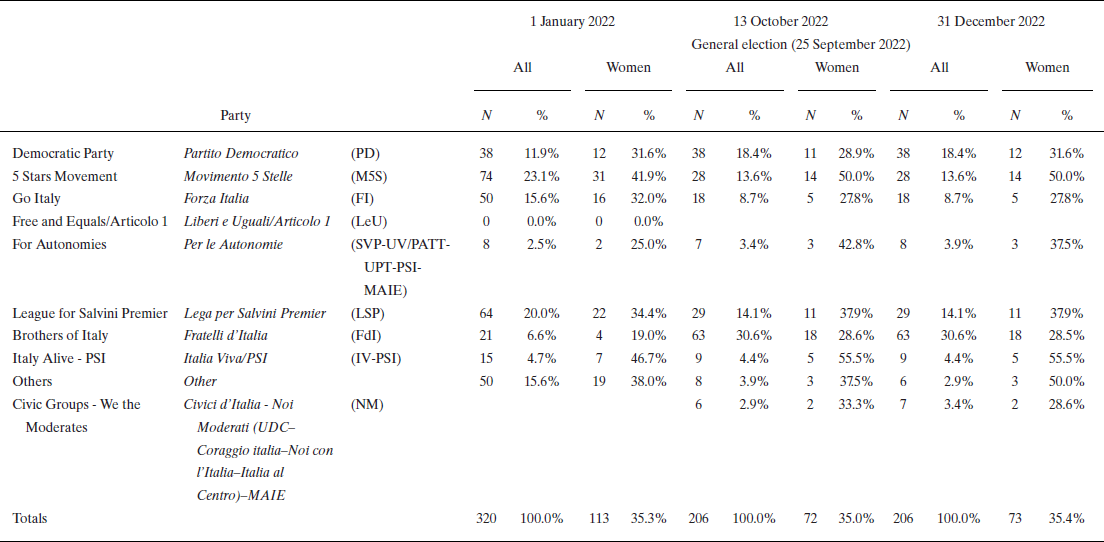

Parliament report

As mentioned above, Giorgia Meloni is the first female Prime Minister in Italy. As much as this aspect could be interpreted as an important element of renovation within Italian politics, it is imperative to look at the data closely in order to observe how the 2022 general elections signal a reduction in the female presence in the Italian Parliament. Data on the gender composition of the Italian Parliament have shown a constant growth in the number of women MPs, with a significant acceleration in the 2013 election bringing the proportion of women within the Italian Parliament even above the EU averages (Pansardi & Pedrazzani Reference Pansardi and Pedrazzani2022). However, the result of the 2022 general election determines a first-time inversion of this trend (EIGE 2022). Following the 2022 political election, a notable reduction in female representation was observed, particularly within the parliamentary groups of the Chamber of Deputies (Camera). Despite the presence of 36.4 per cent female MPs at the beginning of 2022, the new legislature marked a decrease of about 4 percentage points in the Camera. Conversely, there were no significant changes in the Senate in this respect. Notably, individual parliamentary groups displayed important differences in their composition. While centre-right parties, in particular, showed a decreased presence of female MPs in the Camera, the Movimento 5 Stelle reported a greater female presence in both chambers, with 44.2 per cent in the Chamber of Deputies and gender parity in the Senate, even surpassing the previous gender balance of the Movimento 5 Stelle parliamentary groups. An inclusive method of selecting candidates with rules aimed at ensuring greater female representation on electoral lists might have contributed to this outcome for the Movimento 5 Stelle (Venturino & Seddone, Reference Venturino and Seddone2017).

Moreover, the parliamentary composition has changed due to the emergence of new parliamentary groups, such as the Alleanza Verdi-Sinistra (comprising Italian Left/Sinistra Italiana and Green Europe/Europa Verde, among others) and Us Moderates/Noi Moderati (comprising Us with Italy/Noi con l'Italia, Union of the Centre/Unione di Centro and other centrist parties), who presented independent lists in the 2022 elections. Conversely, the Free and Equals-Article 1/Liberi e Uguali-Articolo 1 group ceased to exist since the party merged back into the Democratic Party.

The composition of both legislative chambers after the 2022 elections is shown in Tables 6 and 7.

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Camera dei Deputati) in Italy in 2022

Notes:

1. After the 2022 general elections, the parliamentary group of the PD was named Democratic Party-Democratic and Progressive Italy (Partito Democratico-Italia Democratica e Progressista).

2. After the 2022 general elections, the parliamentary group of FI was named Forza Italia-Berlusconi Presidente-PPR.

3. In the 2022 general elections, LeU ran within a cartel with the Partito Democratico, composing then a common parliamentary group.

4. In the 2022 general elections, Italy Alive ran within a cartel with Action (Azione); they formed a common parliamentary group named Action–Italy Alive–Renew Europe (Azione–Italia Viva–Renew Europe).

5. In 2022, Courage Italy ran within a cartel with other centrist parties, then they composed a common parliamentary group (see below).

6. We the Moderates is a cartel including centrist parties.

Source: Camera dei Deputati (2022) (https://storia.camera.it/).

Table 7. Party and gender composition of the upper house of the Parliament (Senato) in Italy in 2022

Notes:

1. After the 2022 general elections, the parliamentary group of For Autonomies was named Per le Autonomie (SVP-Patt, Campobase, Sud Chiama Nord).

2. After the 2022 general elections, the parliamentary group of the League for Salvini Premier was named Lega Salvini Premier-Partito Sardo d'Azione.

4. In the 2022 general elections, Italy Alive ran within a cartel with Action (Azione); they formed a common parliamentary group named Action–Italy Alive–Renew Europe (Azione–Italia Viva–Renew Europe).

Source: Senato della Repubblica (2022) (https://www.senato.it/home).

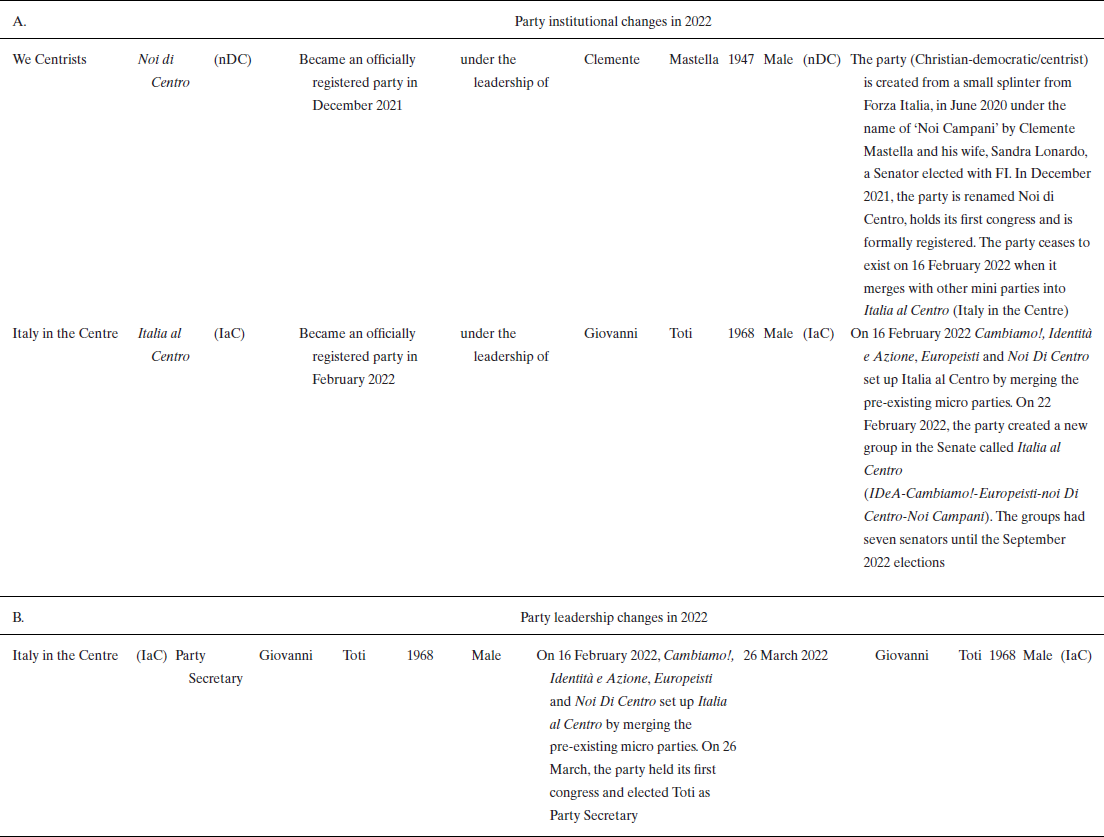

Political party report

The electoral campaign that shaped Italian politics from late spring to early fall 2022 took a toll on Italian parties. The electoral coalitions’ dynamics affected the political party system format during and after the elections and led to a reconfiguration of parties’ structures. Already in Spring 2022, the tensions regarding military aid to Ukraine following the 2022 Russian invasion caused conflicts within the M5S. The party split in June 2022 between a pro-government wing (led by the foreign affairs minister Di Maio, who then founded a small party called Civic Engagement/Impegno Civico, which obtained 0.6 per cent of the votes in the September elections) and a faction around ex-PM Giuseppe Conte, which exited the government. In the previous months, Conte, as leader of the ‘remaining’ Movimento 5 Stelle, restructured the party and emancipated it from Casaleggio, the private company that owned the online voting platform used for internal ballots, and hence the personal data of party members. While Forza Italia and Lega managed to create a shared electoral platform vague enough to overlook the different political choices they had made during the previous legislature, both parties emerged severely weakened from the 2022 elections. Berlusconi's party survived the polls with 8 per cent of the votes (but five ministers in the new Cabinet), and Salvini is now perceived as the main loser of the 2022 elections, as his party, Lega, dropped from 17 per cent to 9 per cent of the vote and his intra-party position was significantly weakened as a result. Leading members of the Lega’s traditional wing, rooted in Padanian nationalism, formed an internal faction called Comitato Nord (Northern Committee, CN) in December 2022.

The resignation of Letta, the incumbent leader of the main opposition party, the Partito Democratico, in September 2022, prompted an internal party struggle in the fall. At this juncture, the regional governor of Emilia-Romagna, Stefano Bonaccini, gained great visibility. He emerged as the prominent figure for local representatives of the party, especially mayors, who expressed their criticism towards the central party and advocated for a process of renewal within the party.

Besides the Movimento 5 Stelle, only very minor parties held internal leadership elections, and in all cases (Italian Republican Party/Partito Repubblicano Italiano; Italian Radicals/Radicali Italiani, Socialist Party/Partito Socialista, Article One/Articolo Uno, and Action/Azione) but two (Solidary Democracy/Democrazia Solidale and Italy at the Centre/Italia al Centro), the incumbent was re-elected (Table 8).

Table 8. Changes in political parties in Italy in 2022

Sources: Camera dei Deputati (2022) (https://storia.camera.it/); Newspaper Il Tempo (2021) (www.iltempo.it/politica/2021/11/24/news/noi-di-centro-clemente-mastella-manovra-quirinale-29558463/); Newspaper Il Tempo (2022) (www.iltempo.it/politica/2022/02/16/news/italia-al-centro-nuovo-movimento-giovanni-toti-gaetano-quagliariello-clemente-mastella-30505975/); Ansa (2022) (www.ansa.it/amp/liguria/notizie/2022/03/26/toti-lancia-italia-al-centro-per-le-comunali-e-per-il-2023_4ad65531-9e5b-415d-8cef-c54dacdd55ee.html).

Institutional change report

In Italy, there were no significant changes to the Constitution, the basic institutional framework, the electoral law or any other major reform in 2022.

Issues in national politics

The main looming issue in national politics in 2022 was the management of the stream of money from the European Recovery Fund by drafting and implementing Italy's NRRP. The centralised style of governance adopted by Draghi in the management and development of the NRRP, vis-à-vis both the governing parties and the regional governments, allowed for some of the necessary efficacy in managing the funds and in launching the main operational programs. The government managed to launch 102 goals and milestones planned for 2022 before its fall in July (Capano & Sandri 2022).

One of the most pressing issues in Italian politics in 2022 was the ongoing economic crisis, which was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the energy price crisis due to the war in Ukraine. In 2022, Italy struggled with high unemployment rates, sluggish economic growth, high inflation rates and a large national debt. Another important political issue in Italy in 2022 was immigration. The country was a major destination for migrants and refugees from Africa and the Middle East in 2022, as had been the case during the previous decade, leading to heated debates during the summer electoral campaign over issues such as border control, asylum policy and the integration of immigrants into Italian society.

Given the national and international context, utility bills and gas prices were the most discussed topics during the electoral campaign, followed by a related topic: energy transition and diversification of energy supply sources. Following her victory, Meloni launched immediate negotiations with the outgoing Premier, Draghi, about managing the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRPP) and responding to the ongoing oil, economic and pandemic crises.