Introduction

Cooperative organisations have ignited a burgeoning fascination within both academic and practical spheres, particularly in the light of the significance that underscores their impact in shaping economic dynamics and their substantial contribution to employment and income generation.

In academia, cooperatives have become a significant focus, with research areas that include governance structures (Borgström, Reference Borgström2013; Puusa & Saastamoinen, Reference Puusa and Saastamoinen2023), economic sustainability (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Gigli and Mariani2021; Borzaga et al., Reference Borzaga, Carini and Tortia2021), social impacts and welfare (Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Modena and Tortia2014; Testi et al., Reference Testi, Bellucci, Franchi and Biggeri2017). The significance of cooperatives in economic and societal development, as well as their member-driven structure and ownership, position them at a crossroads (Pansera & Rizzi, Reference Pansera and Rizzi2020), navigating between two contrasting paradigms (Cornforth, Reference Cornforth1995). On the one hand, the 'degeneration' thesis emphasises the inevitable adoption by cooperatives of capitalist-like structures for competitiveness; on the other hand, the 'regeneration' thesis argues for a process of renovating democratic principles through informal hierarchies and dynamic interactions, even in the face of competitive challenges (Cheney et al., Reference Cheney, Santa Cruz, Peredo and Nazareno2014). The debate about this conflicting thesis is still open, and this research attempts to join the discussion by offering a micro-level perspective.

This article examines the nuanced dynamics intrinsic to cooperatives, focusing on the internal challenges of sustaining a democratic governance that enables member participation. To do this, our study focuses on participation at the individual level in the workplace, an aspect often overlooked within cooperative literature (Camargo Benavides & Ehrenhard, Reference Camargo Benavides and Ehrenhard2021). We propose individual loyalty towards the cooperative as the basic premise for participation (Barnard, Reference Barnard1938; Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2006b) and member voice behaviours as its expression (Budd et al., Reference Budd, Gollan and Wilkinson2010). Literature suggests that loyalty tends to be high in worker cooperatives due to self-selection factors or the unique structural characteristics of cooperative businesses (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2006b). Moreover, members’ voluntary and open manifestation of ideas, suggestions and concerns about work—known in the literature as employee voice—play a crucial role in fostering cooperatives’ participative decision-making and success.

Notwithstanding the notable impact of voice on organisational outcomes, such as creativity and innovation (Guzman & Espejo, Reference Guzman and Espejo2019), in-depth research remains scarce in the context of cooperatives. Voice behaviours can bring relevant issues to light and offer a fresh approach to invigorating and enhancing member participation, reinforcing cooperatives’ principles (Hansmann, Reference Hansmann1999; Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970).

Cooperative members' participation reflects the intrinsic connection between ownership and governance (Camargo Benavides & Ehrenhard, Reference Camargo Benavides and Ehrenhard2021; Spear, Reference Spear2004) in which motives beyond profit are prioritised (Borgström, Reference Borgström2013) and relational and psychological processes rather than structural factors guide individual behaviours (Núñez-Nickel & Moyano-Fuentes, Reference Núñez-Nickel and Moyano-Fuentes2004). As such, this study takes a social perspective, aligning itself with the view that workplace relationships and processes are interdependent in cooperatives (Borzaga & Tortia, Reference Borzaga, Tortia, Michie, Blasi and Borzaga2017). This perspective stems from the foundational principle of mutualism (Yeo, Reference Yeo2002), which manifests in the form of cooperative objectives, including mutual advantages, benefits, better conditions than the market and obligations for both parties.

As a result, cooperatives are noted for a pronounced level of reciprocity (Poledrini, Reference Poledrini2015), a powerful determinant of human behaviours (Falk & Fischbacher, Reference Falk and Fischbacher2006). The theory of reciprocity thus sheds light on this research, which aims to provide theoretical and practical insights for cooperatives by revealing unexplored dimensions of individual-level workplace participation, delving into the connection between members’ loyalty and voice and underscoring their pivotal role in realising democratic ideals within cooperatives.

After this introduction, this article presents the theoretical framework, followed by the articulation of study hypotheses in section “Hypotheses development ”. The section “Research methodology ” provides an overview of the methodology employed in the analysis of nineteen WCs in Italy. Section “Results” describes the findings, which are then discussed in the section “Discussion”, offering theoretical and practical implications for cooperatives.

Theoretical Background on Cooperatives, Reciprocity and Social Exchange Theory

Participative democracy and open involvement through deliberative and social processes distinguish participative organisations like cooperatives, where individuals extensively participate in all aspects of organisational life (Spear, Reference Spear2004). Cooperatives are organisations owned and managed by members through democratic processes (Somerville, Reference Somerville2007). In greater detail, worker cooperatives (WCs) have a unique structure in which members serve as workers and actively participate in company governance and decision-making (Vieta et al., Reference Vieta, Quarter, Spear and Moskovskaya2016). WCs balance profitability with essential values and missions, occupying a middle ground between traditional businesses and nonprofit organisations (Cheney et al., Reference Cheney, Santa Cruz, Peredo and Nazareno2014).

Guided by democratic principles, managing the diversity amongst members and their objectives poses a complex challenge for WCs. Furthermore, as competitive pressures increase, some members may lack influence in decisions, compromising both member ownership and governance (Österberg & Nilsson, Reference Österberg and Nilsson2009; Somerville, Reference Somerville2007). This highlights the need to delve into workplace dynamics and factors influencing member participation to regenerate WC democracy.

In cooperatives, participation and relationship dynamics are not strictly tied to equivalence between individual contributions and economic outcomes; instead, they embody strong reciprocity (Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016; Poledrini, Reference Poledrini2015). According to the theory of reciprocity (Falk & Fischbacher, Reference Falk and Fischbacher2006), reciprocal responses result from perceived kindness or unkindness, signifying profound mutual exchange dynamics within cooperatives wherein individuals expect that cooperative actions yield reciprocal cooperation. This aligns with social exchange theory (SET, Blau, Reference Blau1964) in organisational theory, which explains workplace exchanges between individuals as part of the socialisation process. SET suggests that initiated actions often lead to reciprocating responses, fostering an increased prevalence of reciprocal behaviours (Cropanzano and Mitchell, Reference Cropanzano and Mitchell2016).

Building on this theoretical framework, this study explores how informal and formal relationships convey loyalty towards voice behaviours in WCs by examining two key mediators. The first involves leaders, serving as the cooperative's representatives and the primary channel for implementing organisational processes. By drawing on research demonstrating the benefits of integrating leaders into informal social networks (Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Walumbwa and Weber2008), we investigate the quality of the relationship between leaders and members (LMX), which is characterised by interpersonal exchanges that leverage social relations, mutual respect and reciprocal trust (Schriesheim et al., Reference Schriesheim, Castro and Cogliser1999). In addition, we built on the literature suggesting that leaders embedded in informal relationships with employees tend to use their formal positions to encourage employee voice (Venkataramani et al., Reference Venkataramani, Zhou, Wang, Liao and Shi2016) to propose that LMX affect formal integrative mechanisms (COORD) to coordinate work activities.

Exploring the mediating role of LMX and COORD offers a new interpretation that enriches our understating of relational dynamics at work (Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016) and sheds light on the multifaceted nature of the members’ loyalty–participation dynamics in cooperatives, thereby recognising the impact of interpersonal relationships and structural processes, as explored in previous research on individual and organisational dynamics at work (Nikulina et al., Reference Nikulina, Volker and Bosch-Rekveldt2022).

Hypotheses Development

Employee Loyalty and its Relationship with Different Voice Behaviours

Members are indispensable for any cooperative, and their loyalty and active participation are pivotal for organisational success (Bhuyan, Reference Bhuyan2007). Accordingly, our study proposes loyalty towards the cooperative as participation’s basic premise and voice behaviours as its expression (Budd et al., Reference Budd, Gollan and Wilkinson2010). At the heart, our framework lies Hirschman’s (Reference Hirschman1970) exit–voice–loyalty (EVL) theory, which posits that individuals facing an unsatisfactory situation can respond through voice, by expressing their concerns, or through exit, by leaving the organisation. Loyalty is crucial in this process. However, Hirschman’s loyalty conceptualisation lacked clarity, leading scholars to explore this concept from diverse angles, including it as a third option alongside voice and exit (Berntson et al., Reference Berntson, Näswall and Sverke2010) or as a contingency influencing individuals' choices between them (Graham et al., 1992; Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2006a). Loyalty has also been explored as both passive behaviour (e.g. waiting for future improvement, Rusbult et al., Reference Rusbult, Farrell, Rogers and Mainous1988) and active behaviour (e.g. performing extra work, Yee et al., Reference Yee, Yeung and Edwin Cheng2010).

In our study, we adopted a loyalty concept based on individual commitment (Yoon & Sengupta, Reference Yoon and Sengupta2019) expressed through actions, thoughts and interactions with other members (Davis-Blake et al., Reference Davis-Blake, Broschak and George2003), which not only affects workers’ attitudes but impacts the actions they take in the cooperative (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2006b). This concept reflects employees' emotional attachment to the cooperative (Mazzarol et al., Reference Mazzarol, Soutar and Mamouni Limnios2019), increasing organisational pride and strengthening members’ connection to the cooperative’s values and social missions (Jussila et al., Reference Jussila, Byrne and Tuominen2012a; Wang, Reference Wang2022). Enhanced loyalty acts as a driving force in WCs, motivating members-workers to participate, as shown in Hoffmann's research ().

It is nevertheless essential to note that loyalty operates differently according to voice orientation. Maynes and Podsakoff (Reference Maynes and Podsakoff2014) distinguish between constructive and destructive voices in studying challenging behaviours in organisations. Constructive voices (ConstrV) entail proactive actions that positively challenge the status quo through suggestions and contributions to improve work practices, policies, and procedures. However, acknowledging that individuals do not always engage in constructive voicing, destructive voices (DestrV) represent an alternative aspect. These voices are characterised by a negative nature and involve expressing detrimental opinions voluntarily about work-related aspects. This distinction is essential for comprehending the dynamics of loyalty and participation within cooperatives workplaces. Hence, the following basic assumptions propose:

H1a. Employee loyalty will be positively associated with ConstrV.

H1b. Employee loyalty will be negatively associated with DestrV.

LMX and its Mediating Role

Given that WCs heavily rely on their members as the workforce, the role of leaders and their relationships with members become critical factors in promoting participation (Carlson & Schneiter, Reference Carlson, Schneiter and Agard2011). In this context, the quality of LMX assumes significance, fostering conditions for positive member interactions and outcomes (Shier & Handy, Reference Shier and Handy2020). LMX encompasses crucial relational aspects for cooperatives, including openness for input, mutual trust, respect, reciprocal influence between the leader and follower and a sense of obligation according to a reciprocity process. As leaders are the immediate cooperative link for workers, LMX represents the consistent mechanism through which loyalty translates its impact on voice behaviours. According to the norm of reciprocity (Blau, Reference Blau1964; Poledrini, Reference Poledrini2015), employee voice serves as a behavioural response, providing workers with the opportunity to reciprocate the attachment, support and respect they receive from their leaders as proximal representatives of their WCs. Thus, LMX cultivates trust and enables open communication, empowering members to constructively express their concerns whilst minimising criticism (Unler & Caliskan, Reference Unler and Caliskan2019).

Scholars have explored LMX's mediating role in different contexts, revealing that LMX is a key construct that transmits the effects of individual traits on voice behaviours (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Huang, Liu and Zhao2016). Drawing from literature on cooperatives, LMX can create safe spaces in the workplace, allowing individuals to express dissent, challenge the status quo and take calculated risks through voice behaviour (Shier & Handy, Reference Shier and Handy2020). In line with this, Pei et al. (Reference Pei, Pan, Skitmore and Feng2018) found that the quality of LMX relationships significantly influences voice behaviours.

Building on previous research calling for further investigation into the effects of LMX on different voice behaviours (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Zhu, Zhou, Li, Maguire, Sun and Wang2018), we posit that the level of loyalty translates its influence into a stronger LMX, which channels members' attachment to cooperatives into challenging yet ConstrV behaviours and also buffers members detrimental behaviours, such as DestrV (Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Huang and He2020; Maynes & Podsakoff, Reference Maynes and Podsakoff2014). Unler and Caliskan (Reference Unler and Caliskan2019) have consistently proved that high LMX has an impact in DestrV.

Hence:

Hp2a. LMX mediates the relationship between loyalty and ConstrV.

Hp2b. LMX mediates the relationship between loyalty and DestrV.

Integrative Mechanisms and the Mediating Role

The complexity of the interdependencies within an organisation necessitates ongoing coordination via diverse mechanisms for seamless integration of activities, resources and people. The literature suggests that in cooperatives, horizontal ties generally replace vertical relations. Members exhibit a notable level of diligence and accountability that demonstrates a deep-seated responsibility towards the cooperative, thereby minimising the need for hierarchical supervision (Pencavel, Reference Pencavel2002). Social relations between individuals based on trust and reciprocity emerge as prominent mechanisms of lateral coordination (Borzaga & Tortia, Reference Borzaga, Tortia, Michie, Blasi and Borzaga2017; Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016). In this context, reciprocity norms and trust-based workplace relationships shape the structural mechanisms to integrate and unify activities, serving as the conduit for integrating resources contributed by members (Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016).

The literature on employee voice has investigated various integrative mechanisms (Mowbray, Reference Mowbray2018) by demonstrating that employees manifest voice behaviours through either formal or informal systems and networks (Marchington & Suter, Reference Marchington and Suter2013; Venkataramani et al., Reference Venkataramani, Zhou, Wang, Liao and Shi2016). Prior research has shown a significant relationship between employee loyalty and the mechanisms facilitating voice, thereby shedding light on the prominence of simplified integrative approaches. In the context of loyal employees, this approach predominantly relies on direct communication as the primary means of expressing opinions (Olson-Buchanan & Boswell, Reference Olson-Buchanan and Boswell2002).

In this study, therefore, we explore integrative mechanisms (COORD) as the underlying instrument through which loyal members transmit ConstrV and DestrV behaviours within the cooperative.

Hp3a. COORD mediate the relationship between loyalty and ConstrV.

Hp3b. COORD mediate the relationship between loyalty and DestrV.

The Sequential Mediation of LMX and Integrative Mechanisms for Coordination

The bedrock of any complex mechanism needed to coordinate the greater complexity of work activities in cooperatives lies in the simplest form of coordination, namely relationships (Borzaga & Tortia, Reference Borzaga, Tortia, Michie, Blasi and Borzaga2017).

The literature on relational theory suggests that elements linked to high LMX improve work coordination, which is the means to establish and develop relationships between individuals (Gittell, Reference Gittell2011). Relational theory, in synergy with SET, contends that interpersonal interactions constitute the most spontaneous mode of coordination, characterising the interdependent dynamics amongst individuals at work. This coherently aligns with the cooperative model in which social relationships based on reciprocal trust emerge as the prevailing conduit to orchestrate collective efforts (Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016). The literature has consistently suggested that work coordination amongst members in cooperatives operates under mechanisms that support trust, communication, cooperation and relationships (Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016; Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Modena and Tortia2014). Delving deeper, we suggest that LMX—the relational aspect—and COORD emphasising structural methods for integrating members' activities—the operational aspect—serve as pathways for loyal members' participation in cooperative actions. We argue that the quality of LMX significantly shapes the adoption of different mechanisms based on different relational dynamics to coordinate activities, with the more complex mechanisms driven by social interactions rooted in high-quality relationships (Cropanzano et al., Reference Cropanzano, Anthony, Daniels and Hall2017; Gittell, Reference Gittell2002). Therefore, we argue, first, that LMX and COORD are the mediators that explain how individual loyalty affects employee voice. Second, we speculate that this process operates differently according to the intent of the behaviour (i.e. constructive or destructive). Hence:

Hp4a. LMX and COORD mediate the relationship between loyalty and ConstrV.

Hp4b. LMX and COORD mediate the relationship between loyalty and DestrV.

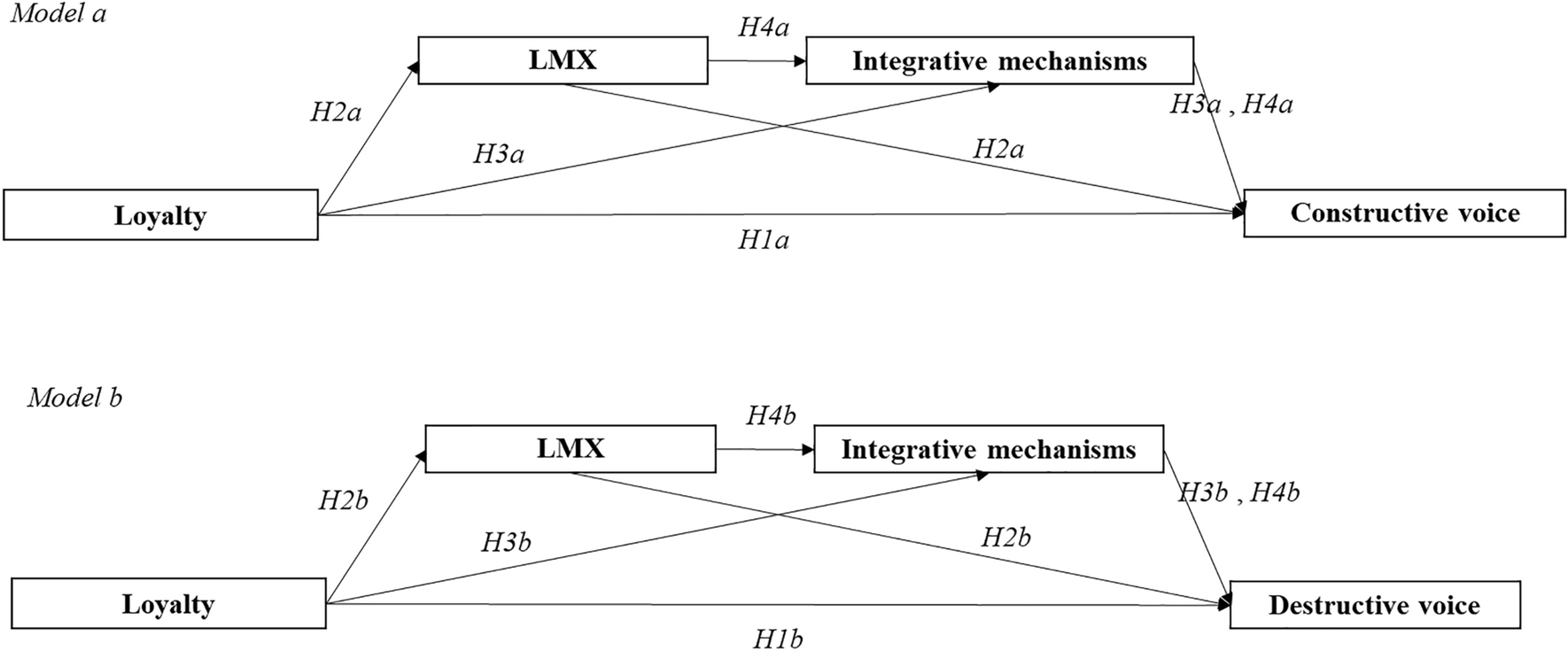

Figure 1 provides an overview of the models investigated to test the hypotheses.

Fig. 1 Research model

Research Methodology

Data Collection and Sample

The research draws data from Italy, a noteworthy case where cooperatives play a significant role, engaging approximately 7.5% of the workforce and contributing around 7% to the country’s GDP (Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy, 2022a).

In Italy, cooperatives are classified based on specific activities, notably in production, labour, and social sectors. Production and labour cooperatives provide members with enhanced employment opportunities. Social cooperatives focus on community well-being, human development, and social integration. With support from Legacoop Toscana, a regional division of the National League of Cooperatives and Mutuals (Legacoop), this study involved 19 WCs in Tuscany, central Italy. Legacoop, acknowledged amongst the largest association representing Italian cooperatives (Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy, 2022b) holds a significant membership base and plays in Tuscany a critical role in shaping the landscape of production and labour as well as social cooperatives (Osservatorio Regionale Toscano sulla Cooperazione, 2008). The WCs involved reflect the Italian coops system and operate across various production and services sectors, spanning agri-food, cultural enterprises, tourism, communication cooperatives and the social sector.

Following the first contact facilitated by Legacoop, the authors independently collected data for this study. The primary instrument for data acquisition was a web-based survey featuring a structured questionnaire with closed-ended questions, which was administered from November 2020 to April 2021. Participants received an initial email with a link to an anonymous online survey, followed by a reminder after 15 days. Respondents included board of directors (BoD) members and other cooperative members, following Vantilborgh (Reference Vantilborgh2015). The latter group was chosen based on specific criteria, such as their roles as immediate supervisors and skip-level leaders (Detert and Treviño, Reference Detert and Treviño2010), or their formal responsibilities in pivotal positions, thus serving as central information hubs. We also reached out to individuals with expertise who are actively engaged in their cooperatives’ decision-making.

As part of a more extensive survey, the questionnaire aimed to gather the different perceptions of the two groups. We sent 808 invitations and received 335 responses (41%). Production and service WCs accounted for 67.16% (225 responses), whilst social WCs type A (caring for health, social care, education, and social services) constituted 32.84% (110 responses). This distribution aligns with the broader landscape of Italian cooperatives (Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy, 2022a). 301 questionnaires were deemed usable for subsequent analyses.

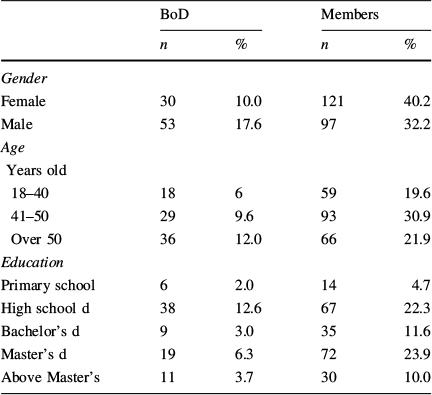

Most respondents were between 41 and 50 years old (40.5%), and the sample was homogeneous in terms of gender (50.17% females; 49.83% males). Over 45% of individuals possessed bachelor's or master's degrees in line with their roles within the cooperative, and 13.62% pursued additional higher education. Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the characteristics of participants.

Table 1 Personal information of participants

BoD |

Members |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

Gender |

||||

Female |

30 |

10.0 |

121 |

40.2 |

Male |

53 |

17.6 |

97 |

32.2 |

Age |

||||

Years old |

||||

18–40 |

18 |

6 |

59 |

19.6 |

41–50 |

29 |

9.6 |

93 |

30.9 |

Over 50 |

36 |

12.0 |

66 |

21.9 |

Education |

||||

Primary school |

6 |

2.0 |

14 |

4.7 |

High school d |

38 |

12.6 |

67 |

22.3 |

Bachelor’s d |

9 |

3.0 |

35 |

11.6 |

Master’s d |

19 |

6.3 |

72 |

23.9 |

Above Master’s |

11 |

3.7 |

30 |

10.0 |

*d degree

Measures

The survey consisted of self-perception measures based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The survey was in Italian and based on the English version of the original scales adapted to the cooperative context, as shown in Appendix 1.

Loyalty We used four items from Davis-Blake et al. (Reference Davis-Blake, Broschak and George2003) loyalty measure that was based on Marsden et al. (Reference Marsden, Kalleberg and Cook1993) commitment scale, recognising loyalty as an acknowledged facet of commitment (Mazzarol et al., Reference Mazzarol, Soutar and Mamouni Limnios2019; Yoon & Sengupta, Reference Yoon and Sengupta2019). The items assessed an individual’s commitment to the goals and values of the organisation as well as the level of desire to maintain membership (Marsden et al., Reference Marsden, Kalleberg and Cook1993; Wang, Reference Wang2022). An adapted scale was likewise adopted in the Workplace Employment Relations Surveys in 2004 and 2011 (α = 0.79).

LMX. The first mediator contained Scandura and Graen’s five items (Reference Scandura and Graen1984), which have also been previously adopted by studies asking employees to evaluate this relationship (Kauppila, Reference Kauppila2014; Wayne et al., Reference Wayne, Shore and Liden1997) (α = 0.91).

Integrative Mechanisms (COORD) Four items explored formal integrative mechanisms within organisational structures based on established research (Gupta & Govindarajan, Reference Gupta and Govindarajan2000; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Van den Bosch and Volberda2005; Kumar & Seth, Reference Kumar and Seth1998; Lombardi et al., Reference Lombardi, Cavaliere, Giustiniano and Cipollini2020). To align with the WCs research context, we adapted Gupta and Govindarajan's (Reference Gupta and Govindarajan2000) scales, as did Jansen et al. (Reference Jansen, Van den Bosch and Volberda2005), adding an item to comprehensively explore formal integrative mechanisms based on the literature (Chisholm, Reference Chisholm1992; Claggett & Karahanna, Reference Claggett and Karahanna2018; Kumar & Seth, Reference Kumar and Seth1998). These integrative mechanisms vary in complexity from least to most complex (i.e. liaison personnel to teams, Gupta & Govindarajan, Reference Gupta and Govindarajan2000; Kumar & Seth, Reference Kumar and Seth1998). Following the weight attribution methodology (Gupta & Govindarajan, Reference Gupta and Govindarajan2000; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Van den Bosch and Volberda2005), we attributed a weight of 3 to the most complex mechanism, ‘namely teams’; 2 to the moderately complex ‘regular meetings with the boss’; 1.5 to ‘formal planning in advance’; and 1 to the least complex ‘liaison personnel.’ This refinement resulted in increased reliability, with a higher Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.704 compared to the previous scale's coefficient of below 0.64.

Employee Voice The measures of the dependent variables were from Maynes and Podsakoff (Reference Maynes and Podsakoff2014) Constructive voice (ConstrV, α = 0.95) and destructive voice (DestrV, α = 0.89) were both assessed with five items as used by prior studies (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Wu, Dong, Chen, Wei and Duan2022; Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Huang and He2020; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Lucianetti, Hsu, Yim and Sorensen2021; Romney, Reference Romney2020; Unler & Caliskan, Reference Unler and Caliskan2019).

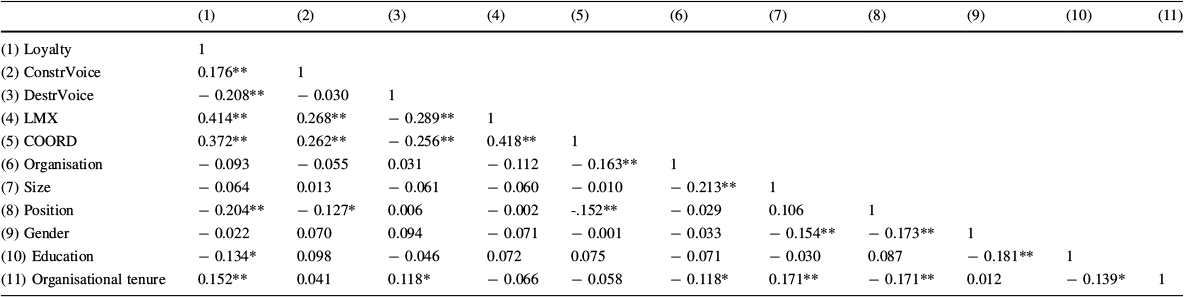

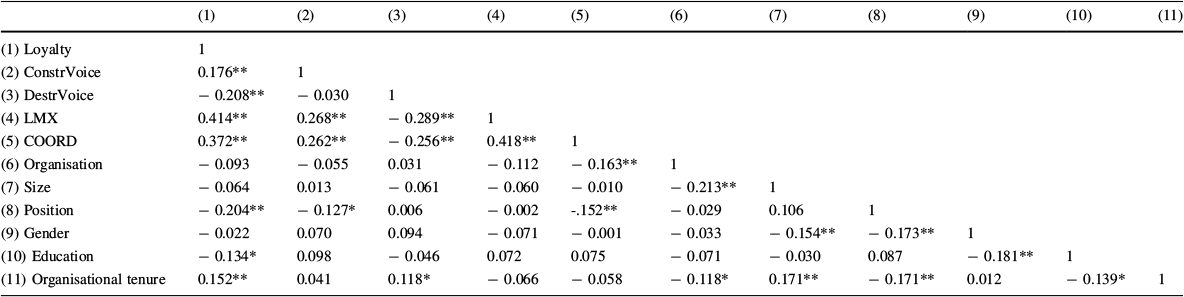

Control Variables We added control variables based on previous studies (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Mosseri, Vromen, Baird, Hill and Probyn2021; Zhu & Wu, Reference Zhu and Wu2023) to reduce the impact of alternative explanations of the results: position (1 = BoD; 2 = cooperative worker), gender (1 = female; 2 = male), organisation (n = 19), size (1 = micro; 2 = small; 3 = medium; 4 = big), education (1 = the lowest level; 5 = the highest level) and organisational tenure (years spent working in the cooperative). Table 2 shows the Person’s correlations.

Table 2 Person's correlations

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

(11) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) Loyalty |

1 |

||||||||||

(2) ConstrVoice |

0.176** |

1 |

|||||||||

(3) DestrVoice |

− 0.208** |

− 0.030 |

1 |

||||||||

(4) LMX |

0.414** |

0.268** |

− 0.289** |

1 |

|||||||

(5) COORD |

0.372** |

0.262** |

− 0.256** |

0.418** |

1 |

||||||

(6) Organisation |

− 0.093 |

− 0.055 |

0.031 |

− 0.112 |

− 0.163** |

1 |

|||||

(7) Size |

− 0.064 |

0.013 |

− 0.061 |

− 0.060 |

− 0.010 |

− 0.213** |

1 |

||||

(8) Position |

− 0.204** |

− 0.127* |

0.006 |

− 0.002 |

-.152** |

− 0.029 |

0.106 |

1 |

|||

(9) Gender |

− 0.022 |

0.070 |

0.094 |

− 0.071 |

− 0.001 |

− 0.033 |

− 0.154** |

− 0.173** |

1 |

||

(10) Education |

− 0.134* |

0.098 |

− 0.046 |

0.072 |

0.075 |

− 0.071 |

− 0.030 |

0.087 |

− 0.181** |

1 |

|

(11) Organisational tenure |

0.152** |

0.041 |

0.118* |

− 0.066 |

− 0.058 |

− 0.118* |

0.171** |

− 0.171** |

0.012 |

− 0.139* |

1 |

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.01

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Validity and Reliability

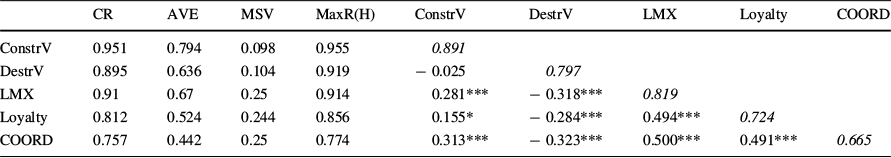

To assess construct validity, we conducted both convergent and discriminant validity tests (Table 3). For convergent validity, we verified that the average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded 0.50. For constructs falling below this threshold, we considered composite reliability (CR) values, all of which exceeded 0.70 as required (Malhotra & Dash, Reference Malhotra and Dash2016). For discriminant validity, we compared the AVE and the inter-construct correlations (on the diagonal in Table 3) with the inter-construct correlation coefficients. In all instances, the former exceeded the latter. Overall, these checks confirmed the validity of the measurement instruments employed.

Table 3 Validity results

CR |

AVE |

MSV |

MaxR(H) |

ConstrV |

DestrV |

LMX |

Loyalty |

COORD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ConstrV |

0.951 |

0.794 |

0.098 |

0.955 |

0.891 |

||||

DestrV |

0.895 |

0.636 |

0.104 |

0.919 |

− 0.025 |

0.797 |

|||

LMX |

0.91 |

0.67 |

0.25 |

0.914 |

0.281*** |

− 0.318*** |

0.819 |

||

Loyalty |

0.812 |

0.524 |

0.244 |

0.856 |

0.155* |

− 0.284*** |

0.494*** |

0.724 |

|

COORD |

0.757 |

0.442 |

0.25 |

0.774 |

0.313*** |

− 0.323*** |

0.500*** |

0.491*** |

0.665 |

CR Composite reliability, AVE average variance extracted, MSV maximum shared variance, MaxR(H) maximum reliability, on the diagonal in italics square root of AVE

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Common Method Variance

To avoid common method variance (CMV), a known limitation of self-report data, we carried out the following procedures (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The items under examination were integrated into a broader questionnaire alongside other constructs related to employee voice. Translated into Italian for clarity, thereby ensuring clarity and precision whilst dropping interpretational ambiguity, they were presented randomly to participants, with dependent and independent variables separated. Survey instructions emphasised there were no right or wrong answers, encouraging participants to choose responses aligning with their opinions in a quiet environment. After collecting data, the Harman's (Reference Harman1976) single-factor test, employing principal component factoring, produced an unrotated factor solution explaining 35% of the covariance, below the 50% threshold (Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Kim and Patil, A. J. M. S.2006). Thus, common method bias was unlikely to be a significant concern in our study.

Additional Checks

To address multicollinearity, we examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) in accordance with James et al. (Reference James, Witten, Hastie and Tibshirani2013). In addition, to prevent any potential issues with heteroscedasticity, we conducted White tests. The results provided strong evidence against multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity in our analyses.

Measurement Model

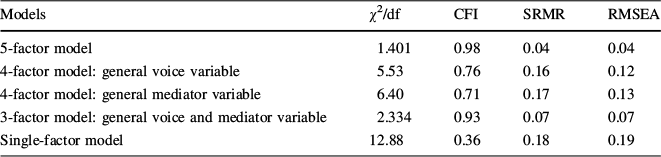

Using IBM AMOS 23, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis by loading all items into the 5-factor model (Table 3), showing an overall satisfactory fit (Hu et al., Reference Hu, L.T., Bentler, P.M.1999; Kline, Reference Kline2015). Similar to prior works (Vantilborgh, Reference Vantilborgh2015), (n − 1)-factor models were examined, loading different items into the same latent variable and the remaining observed items into respective latent variables. All alternative factor models demonstrated poor fit (Table 4), confirming the consistency of factor structures with the conceptual model, as intended in the 5-factor model.

Table 4 Results of CFA

Models |

χ 2/df |

CFI |

SRMR |

RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

5-factor model |

1.401 |

0.98 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

4-factor model: general voice variable |

5.53 |

0.76 |

0.16 |

0.12 |

4-factor model: general mediator variable |

6.40 |

0.71 |

0.17 |

0.13 |

3-factor model: general voice and mediator variable |

2.334 |

0.93 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

Single-factor model |

12.88 |

0.36 |

0.18 |

0.19 |

Data Analysis

We employed the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2017) to test mediation models using OLS regression. Hayes' approach uses bootstrapping to create an empirical representation of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect and construct confidence intervals (CIs), recommended for addressing weaknesses associated with the normal theory approach (the Sobel test). Bootstrap CIs better handle sampling distribution irregularities, providing more accurate inferences and higher test power (Hayes, Reference Hayes2017). Our analyses employed 5,000 bootstrap estimates for 95% bias-corrected CIs, investigating three indirect effects of loyalty on employee voice: through LMX, COORD, and a serial mediation model involving both.

Hypothesis Testing

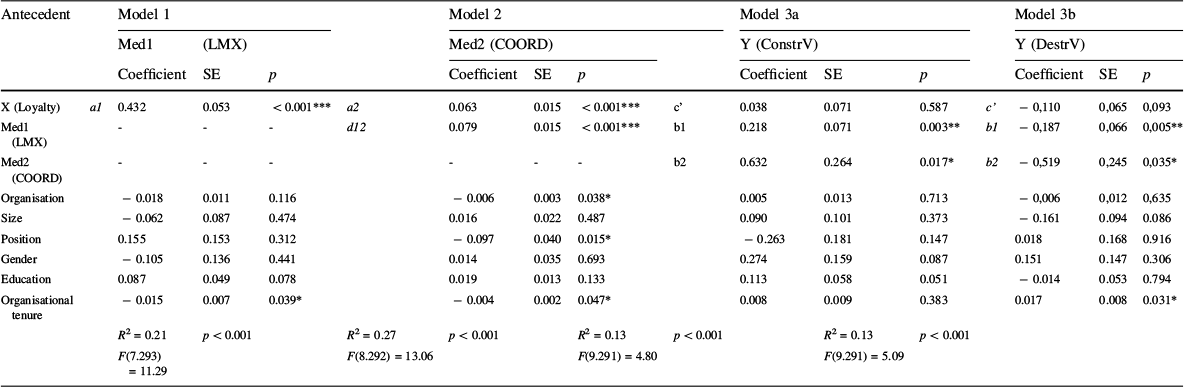

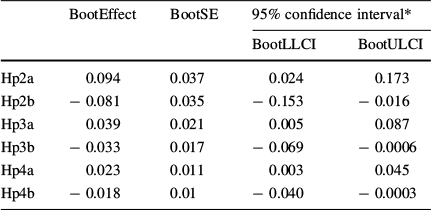

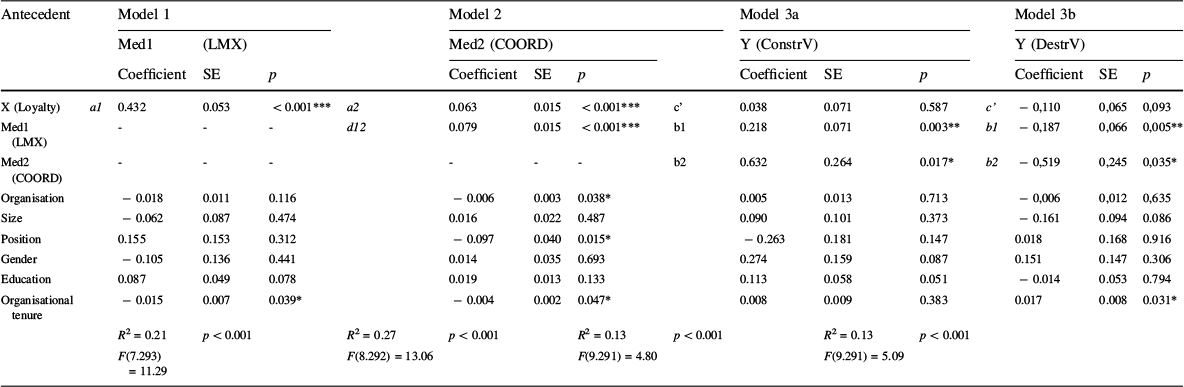

Tables 5 and 6 show the results of the regression analysis. Table 5 shows that amongst the control variables, only organisational tenure is significant for destructive voice. The results show that loyalty had a significant direct effect on both ConstrV (b = 0.19; p < 0.01) and DestrV (b = − 0.24; p < 0.001), thus confirming Hp1a and Hp1b. However, the inclusion of the mediators in the regression did not significantly enhance their significance. To confirm mediation, predicting an indirect effect of loyalty ➜ mediator(s) ➜ voice was required. In the first regression (Table 5, Model 1), loyalty was linked to LMX (a 1 = 0.432; p < 0.001). In Model 3a, LMX was associated with ConstrV (b 1 = 0.218; p < 0.01). The significant indirect and positive effect (a 1b 1 = 0.094) confirmed Hp2a, with BootCI entirely above zero (Table 6). In Model 3b, LMX associated with DestrV (b 1 = − 0.187; p < 0.01), and the significant negative indirect effect (a 1b 1 = − 0.081) confirmed Hp2b, with BootCI entirely below zero (Table 6).

Table 5 Mediation results

Antecedent |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3a |

Model 3b |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Med1 (LMX) |

Med2 (COORD) |

Y (ConstrV) |

Y (DestrV) |

|||||||||||||

Coefficient |

SE |

p |

Coefficient |

SE |

p |

Coefficient |

SE |

p |

Coefficient |

SE |

p |

|||||

X (Loyalty) |

a1 |

0.432 |

0.053 |

< 0.001*** |

a2 |

0.063 |

0.015 |

< 0.001*** |

c' |

0.038 |

0.071 |

0.587 |

c' |

− 0,110 |

0,065 |

0,093 |

Med1 (LMX) |

- |

- |

- |

d12 |

0.079 |

0.015 |

< 0.001*** |

b1 |

0.218 |

0.071 |

0.003** |

b1 |

− 0,187 |

0,066 |

0,005** |

|

Med2 (COORD) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

b2 |

0.632 |

0.264 |

0.017* |

b2 |

− 0,519 |

0,245 |

0,035* |

||

Organisation |

− 0.018 |

0.011 |

0.116 |

− 0.006 |

0.003 |

0.038* |

0.005 |

0.013 |

0.713 |

− 0,006 |

0,012 |

0,635 |

||||

Size |

− 0.062 |

0.087 |

0.474 |

0.016 |

0.022 |

0.487 |

0.090 |

0.101 |

0.373 |

− 0.161 |

0.094 |

0.086 |

||||

Position |

0.155 |

0.153 |

0.312 |

− 0.097 |

0.040 |

0.015* |

− 0.263 |

0.181 |

0.147 |

0.018 |

0.168 |

0.916 |

||||

Gender |

− 0.105 |

0.136 |

0.441 |

0.014 |

0.035 |

0.693 |

0.274 |

0.159 |

0.087 |

0.151 |

0.147 |

0.306 |

||||

Education |

0.087 |

0.049 |

0.078 |

0.019 |

0.013 |

0.133 |

0.113 |

0.058 |

0.051 |

− 0.014 |

0.053 |

0.794 |

||||

Organisational tenure |

− 0.015 |

0.007 |

0.039* |

− 0.004 |

0.002 |

0.047* |

0.008 |

0.009 |

0.383 |

0.017 |

0.008 |

0.031* |

||||

R 2 = 0.21 |

p < 0.001 |

R 2 = 0.27 |

p < 0.001 |

R 2 = 0.13 |

p < 0.001 |

R 2 = 0.13 |

p < 0.001 |

|||||||||

F(7.293) = 11.29 |

F(8.292) = 13.06 |

F(9.291) = 4.80 |

F(9.291) = 5.09 |

|||||||||||||

N = 301

Table 6 Indirect effects of employee loyalty on voice behaviours

BootEffect |

BootSE |

95% confidence interval* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

BootLLCI |

BootULCI |

|||

Hp2a |

0.094 |

0.037 |

0.024 |

0.173 |

Hp2b |

− 0.081 |

0.035 |

− 0.153 |

− 0.016 |

Hp3a |

0.039 |

0.021 |

0.005 |

0.087 |

Hp3b |

− 0.033 |

0.017 |

− 0.069 |

− 0.0006 |

Hp4a |

0.023 |

0.011 |

0.003 |

0.045 |

Hp4b |

− 0.018 |

0.01 |

− 0.040 |

− 0.0003 |

BootLLCI bootstrapping lower limit confidence interval, BootULCI bootstrapping upper limit confidence interval

*5000 bootstrap samples

Applying the same approach, regression Model 2 (Table 5) showed that loyalty correlated with COORD (a 2 = 0.063; p < 0.001). In Model 3a, COORD associated with ConstrV (b 2 = 0.632; p < 0.05). The significant and positive indirect effect (a 1b 1 = 0.039) was confirmed by BootCI being entirely above zero (Table 6), supporting Hp3a. In Model 3b, COORD associated with DestrV (b 1 = − 0.052; p < 0.05). The significant and negative indirect effect (a 2b 2 = 0.032) was confirmed by BootCI being entirely below zero, supporting Hp3b.

The serial indirect effect of loyalty ➜ LMX ➜ COORD ➜ voice shown in Table 6 confirms the positive serial indirect effect of loyalty through LMX and of COORD on ConstrV (a 1d 12b 2 = 0.023), and a negative indirect effect of loyalty through LMX and of COORD on DestrV (a 1d 12b 2 = − 0.018).

Discussion

This study delves into member participation dynamics in WCs, venturing into the uncharted territory of individual-level complexities (Camargo Benavides & Ehrenhard, Reference Camargo Benavides and Ehrenhard2021). The study posited loyalty to the cooperative as the foundational premise and voice as the behavioural manifestation of participation. The findings shed light on the significant impact of interpersonal relationships in affecting operational processes and explaining members’ loyalty and participation dynamics. The ensuing implications are subsequently discussed.

Theoretical Implications

Whilst extensive literature explores Hirschman's EVL theory in workplace contexts, a notable research gap exists in examining loyalty's impact on participation within cooperatives using Hirschman's framework (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2006a, Reference Hoffmann2006b). Cooperative membership requires significant investments, making leaving a complex decision. In such situations, loyalty often keeps members from leaving and leads them to express ideas and dissatisfaction through 'voice,' enabling participation. The significance of membership stems from having a say in the cooperative (Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016). In the light of our study findings, voice behaviours consistently play a crucial role in regenerating democracy and renovating members’ participation in the workplace. Moreover, within cooperatives, constructive and destructive voices mirror the extent to which members' participation aligns with or challenges cooperative values. Loyalty fosters active participation, aligning with cooperative principles of collective decision-making and shared responsibility, it minimises destructive behaviours that contradict the core values of cooperatives in prioritising reciprocity in collaboration (Poledrini, Reference Poledrini2015).

Furthermore, due to the distinctive structure of WCs, namely that they are characterised by democratic governance led by members–workers (Vieta et al., Reference Vieta, Quarter, Spear and Moskovskaya2016), research highlights the crucial role of leadership in stimulating, propelling and nurturing active member participation (Carlson & Schneiter, Reference Carlson, Schneiter and Agard2011). Simultaneously, scholars depict cooperatives as operating on social relations built on trust and reciprocity rather than strict hierarchy (Borzaga & Tortia, Reference Borzaga, Tortia, Michie, Blasi and Borzaga2017). Our study consistently shows that social relations and interactions between leaders and members in WCs act as the central mechanism through which members translate their loyalty into participative behaviours.

Finally, our finding demonstrates that SET (Blau, Reference Blau1964) provides a suitable conceptual basis for investigating individuals’ relational dynamics within cooperatives, where voluntary and informal social exchanges dominate the system of activities amongst members (Jussila et al., Reference Jussila, Byrne and Tuominen2012a, Reference Jussila, Goel and Tuominen2012b). In this complex context, this study confirms that leaders are the indispensable linchpin for reinforcing interconnection and cooperation amongst members, and their reciprocal relationship influences the coordination of their activities. Integrative mechanisms then serve as an additional channel through which members translate their loyalty into tangible participatory behaviours.

Practical Implications for WCs

Our study has significant implications for cooperative management, emphasising the pivotal role of loyalty in reinforcing the cooperative values of member participation. Loyalty is an essential organisational condition resulting from the emotional attachment individuals develop towards an impersonal entity, in this context, the cooperative. Consequently, cooperatives should prioritise cultivating member loyalty by eliciting emotional (affective) commitment. This involves not only emphasising superior service quality and cost competitiveness compared to market alternatives but also intentionally fostering a shared mission and value system that resonates with members (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Jussila and Kalmi2016; Mazzarol et al., Reference Mazzarol, Soutar and Mamouni Limnios2019). Members must align with a collective purpose beyond individual interests. In some cases, individuals actively seek cooperative membership, whilst in other cases, they may encounter employment opportunities and subsequently adopt the cooperative philosophy (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2006b). Individuals fully embracing their cooperative's principles aspire to create meaningful affiliations for substantial positive change in the broader community. As a result, cooperatives should intentionally forge strong connections with members and engage the broader community to cultivate lasting, mutually beneficial relationships. These efforts contribute to nurturing member loyalty towards the cooperative and its essence, thus encouraging participation at work.

Our findings also highlight that leaders play a critical role as the linchpin between the cooperative and its members and that high-quality LMX shapes the social interactions and the way in which individuals organise and coordinate work activities. Consequently, cooperatives should recruit leaders aligned with their fundamental values and who demonstrate a propensity for relational engagement, mutual respect and support (Basterretxea et al., Reference Basterretxea, Heras-Saizarbitoria and Lertxundi2019), which can facilitate members’ concrete participation in the cooperative. Given its pivotal role in workplace dynamics, cooperatives should implement leadership training and reward systems that emphasise the significance of social relationships and workplace support in unlocking individual potential and motivating improvement. Members need to develop trust in the relationships they share with their leaders, who should adopt a style inspired by the maieutic and the pars construens of the Socratic method, thereby emphasising dialogue. Aligning the above HRM practices with this approach empowers leaders to act as members' coaches—being open, attentive, and supportive in translating ideas into tangible actions.

To enhance daily participation in WCs decisions, effective workplace communication processes are essential because they enable coordination through simple, direct interactions. Consequently, designers of cooperative structures should ensure the ability to support social exchanges, participation and horizontal connections. The organic organisational structure, characterised by minimal authority lines and rules along with increased lateral integration (Burns & Stalker, Reference Burns and Stalker1961), serves as an effective model for achieving these objectives (Kyriakopoulos et al., Reference Kyriakopoulos, Meulenberg and Nilsson2004). In this regard, face-to-face interactions, scheduled meetings for task integration and informal feedback systems can enhance staff relationships, fostering active engagement and member participation.

Lastly, despite daily competitive pressures, cooperatives must steadfastly uphold democratic governance rooted in trust-based relationships, organic organisational models and mutual values shaping their business culture and strategic decisions. Continuous reinforcement is essential to sustain cooperative behaviours and social connections, thus, preventing erosion over time (Poledrini, Reference Poledrini2015). Therefore, cooperatives should proactively encourage workplace social gatherings, serving a dual purpose by fostering interpersonal relationships amongst leaders and members and nurturing the attachment amongst those who resonate with the cooperative’s values.

The success of these strategies relies on the unique context of each cooperative and the commitment of its members and leadership. Various factors can significantly influence initiatives to enhance member participation in diverse industries, sizes, and locations. As both business entities and social organisations, cooperatives must consider challenges shaped by factors like geographic location, market conditions, and social development (Puusa & Saastamoinen, Reference Puusa and Saastamoinen2023). This complexity forms the dynamic context where implementing suggested strategies highlights the necessity for adaptable and context-sensitive approaches to foster cooperative success.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Whilst our research has yielded promising findings, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. Considering the contextual dynamics within cooperatives, other mediators might intervene between individual loyalty and voice behaviours. The cooperative model particularly emphasises trust as fundamental element (Hatak et al., Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016). Members invest trust in both leadership and one another, forming a dynamic element that evolves over time and shapes the cooperative culture. Variations in trust levels, whether in leadership or amongst members, can thus serve as mediators influencing participation. Also, whilst not identified as direct determinants in this study, individual education may influence the relationship investigated by enhancing communication skills and self-efficacy, boosting confidence in expressing one's voice. Similarly, the extended tenure of cooperative worker–members may boost participation initiatives whilst reducing destructive behaviours, as found in this study, suggesting further investigation. Although our serial mediation model elucidates causal relationships amongst variables (Hayes, Reference Hayes2017), the cross-sectional nature of our database limits conclusive causal directions. Literature supports causality from loyalty to voice, with loyalty as the entry point for cooperative participation (Barnard, Reference Barnard1938; Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2006b). However, a heightened degree of voice might reciprocally enhance loyalty, and the reciprocal nature within cooperatives may trigger an iterative process. A longitudinal study could explore this interesting research avenue. Despite efforts to mitigate biases through diverse data sources (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), employing alternative methods, such as third-party ratings (e.g. supervisor evaluations of members’ voice) may enhance research robustness and validity.

Furthermore, it is important to note that Italian cooperative movement has historically exhibited diverse orientations (Sacchetto & Semenzin, Reference Sacchetto and Semenzin2014). However, contemporary developments indicate a diminishing influence of factors contributing to divisions, as major associations have entered into a federative agreement, marking substantial progress towards integration. Despite this positive shift and the alignment of our sample with the broader Italian cooperative landscape (Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy, 2022a), it is essential to acknowledge that our study's focus on Tuscany and cooperatives affiliated with a singular association could potentially limit the generalisability of our findings. Consequently, the concentration in Tuscany of cooperatives in manufacturing sectors, along with neighbouring regions of Umbria and Emilia Romagna (OECD, 2021), opens avenues for expanding this study in future research. This research should encompass cooperatives affiliated with diverse associations, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamic cooperative system.

Finally, our survey, conducted between 2020 and 2021, primarily focused on traditional workplace attitudes amongst cooperative members, without explicitly exploring the COVID-19 pandemic or the remote work impact. Future research could integrate these implications, offering significant contributions to cooperatives functioning and literature (Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Dufays, Friedel and Staessens2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Firenze within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix 1

Scales Adapted in this Study

Loyalty (Davis-Blake et al., Reference Davis-Blake, Broschak and George2003).

a. I am proud to be working for this Cooperative.

b. I would take almost any job to keep working for this Cooperative.

c. I would turn down another job for more pay in order to stay with this Cooperative.

d. I find that my values and the Cooperative's values are very similar.

LMX (Scandura & Graen, Reference Scandura and Graen1984).

a. I usually know where I stand with my boss.

b. My boss has enough confidence in me that he/she would defend and justify my decisions if I was not present to do so.

c. My boss understands my problems and needs.

d. I can count on my boss to "bail me out," even at his or her own expense, when I really need it.

e. My boss recognises my potential.

Integrative Mechanism (COORD, Gupta & Govindarajan, Reference Gupta and Govindarajan2000).

a. liaison personnel

b. teams

c. regular meetings

d. formal planning in advance

Constructive Voice (Maynes & Podsakoff, Reference Maynes and Podsakoff2014).

a. I frequently make suggestions about how to do things in new or more effective ways at work.

b. I often suggest changes to work projects in order to make them better.

c. I often speak up with recommendations about how to fix work-related problems.

d. I frequently make suggestions about how to improve work methods or practices.

e. I regularly propose ideas for new or more effective work methods.

Destructive Voice (Maynes & Podsakoff, Reference Maynes and Podsakoff2014).

a. I often bad-mouth the Cooperative’s policies or objectives.

b. I often make insulting comments about work-related programs or initiatives.

c. I frequently make overly critical comments regarding how things are done in the Cooperative.

d. I often make overly critical comments about the Cooperative’s work practices or methods.

e. I hardly criticise the Cooperative’s policies, even though the criticism is unfounded.