Replication Materials

The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available on the European Journal of Political Research Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/deegoddard.

Introduction

When a new government is announced, the gender balance of the cabinet is one of the first assessments of the newly appointed decision makers. But the images of the new cabinets do not reveal one of the most important features of the government formation process: which portfolio has been assigned to each minister. While in some contexts women are being appointed to high‐salience portfolios such as justice and finance, there are other circumstances where women are only allocated the traditionally ‘feminine’ policy areas such as health and family.

Some cabinet posts are perceived as being an important part of the traditional ‘core’ of government (Blondel & Thiebault Reference Blondel and Thiebault1991), while others are important to the party (Warwick & Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006). Some portfolio policy areas are seen as traditionally ‘masculine’ while others are traditionally ‘feminine’ (Krook & O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). Whether, when and where women are appointed to these posts is important for the representation of women's views at the highest levels of government decision making.

Most existing analyses of government appointments overlook these important gender dynamics, and analyses from the gender and politics literature overlook the important partisan features of ministerial appointment. By considering both the characteristics of political parties and gendered dynamics, this article provides an analysis of how party characteristics influence where women sit around the ministerial table. These party characteristics include the salience of different policy areas, the party's ideological orientation and the gender attitudes of the party's voters.

This analysis addresses the research question: under what circumstances do women get appointed to different ministerial portfolios? The allocation of ministers to government portfolios is a complex, multidimensional problem faced by party leaders. Therefore, I develop a theoretical framework that examines the allocation of ministers to cabinet portfolios based on the policy‐, office‐ and vote‐seeking motivations of party leaders (Müller & Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999).

Based on this theoretical framework, the empirical analysis in this article provides an insight into when women get allocated to different government portfolios. By combining datasets on 7,005 cabinet appointments across 29 European countries from the late 1980s until 2014, this article provides a uniquely detailed time‐series cross‐sectional insight into the allocation of policy areas to women ministers.

The findings of this party‐level analysis have important implications for our understanding of women's representation in the most powerful political decision‐making positions across Europe. First, voter attitudes about women's role appear to have an impact on the gender composition of the cabinet. Second, party ideology is a moderating factor in the process of government appointments and plays an important part in determining which portfolios are allocated to men and women. Finally, women are less likely to be selected for ‘masculine’ cabinet positions, and therefore prime ministers and party leaders may be overlooking potential ministerial talent based on gendered biases.

Theory and hypotheses

With the appointment of Sylvie Goulard as France's Ministre des Armées in May 2017, the defence minister in four of Europe's five largest economies was a woman (Henley Reference Henley2017). Yet, in the cabinet which met at the Elysée prior to the formation of the 2017 French government, there were no women in the core offices of state. This pattern is familiar across Europe, where the allocation of women to government portfolios fluctuates between and across governments and countries.

The selection of ministers is a complex problem for party leaders; British Prime Minister Harold Wilson called it ‘a nightmarish multi‐dimensional jigsaw puzzle’ (Wilson Reference Wilson1976: 34). As such, a theoretical framework for the allocation of portfolios to ministers must consider these multiple and competing dimensions. Müller and Strøm's (Reference Müller and Strøm1999) classic framework of party leader decision making provides a theoretical framework through which to understand ministerial selection. They argue that party leaders have three core motivations: policy, office and votes. Leading a political party requires decision making based on trading off these motivations, and deciding who to place in which ministry is a typical example of the need to balance these priorities. Ministers need to be effective and trustworthy in delivering policy objectives, they must not cause the party to lose political office and they need to appeal to the electorate.

Our understanding of the factors which lead to ministerial appointments has advanced in recent years, including intra‐party politics (Mershon Reference Mershon2001; Kam et al. Reference Kam2010), policy issue salience (Greene & Jensen Reference Greene and Jensen2017) and individual policy positions (Giannetti & Laver Reference Giannetti and Laver2005). There have also been further developments in the analysis of how the backgrounds of ministers influence whether they get appointed to government and which portfolio they get, as well as the impact that the individual characteristics of ministers can have on the policy decisions they make in office (Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2015, Reference Alexiadou2016; Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Tosun2015). However, these analyses do not take into consideration whether the ministers that are appointed to cabinet positions are male or female. And, therefore, they overlook a key aspect of the ministerial selection decision‐making process.

In this article, I build on the existing analyses that have addressed the representation of women in ministerial potions at the government level (Davis Reference Davis1997; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2000; Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2005; Krook & O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; Claveria Reference Claveria2014; O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien2015). In the developing literature on ‘who gets what’ in coalition governments, analyses have shown the importance of political parties and their characteristics for the appointment of ministers (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Raabe & Linhart Reference Raabe and Linhart2014; Greene & Jensen Reference Greene and Jensen2017). This is particularly the case in the European context, where parliamentary and semi‐presidential systems dominate the political landscape (Schleiter & Morgan‐Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan‐Jones2009). The most detailed cross‐national analysis of women's appointment to cabinets considers party dynamics in presidential systems (Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2016). However, this is in a context where the separation of the executive and legislature leads to very different dynamics of cabinet appointments to European parliamentary democracies, especially in relation to the nature of party attachments, the selection pool and the ministerial appointment process. By considering the party‐level factors that shape government appointments in a European context, this article provides an understanding of how we end up with the diverse range in the representation of women in ministerial positions we see across European democracies.

This article also develops our understanding of the process of allocating ministers and contributes to the existing literature on government appointments by demonstrating the importance of gender dynamics in who gets allocated which policy area. Without considering the important factor of the gender of ministers, these studies have overlooked a key factor shaping who is in government. By examining the allocation of ministerial portfolios through the gendered motivations of party leaders, I am able to hypothesise when we see women appointed to different portfolios across governments and start to consider why this may be.

Three important aspects of the ministerial selection process mean that it is particularly difficult to examine why ministers get appointed. First, ministerial selection discussions and decisions take place in secret, behind closed doors, between a small number of high‐level individuals (Annesley Reference Annesley2015). Second, is not possible to make a realistic assessment of the ministerial selection pool. Therefore, I consider the output of this decision‐making process: the final allocation of portfolios which is announced to the electorate. Finally, this ‘jigsaw puzzle’ has a large number of counterfactuals, with a wide range of dimensions. Therefore, it is not necessarily the case that because an individual is not deemed suitable for a particular ministry, that they are not suitable for government positions in any area. For example, the fact that a woman is not appointed to a ‘core’ portfolio does not mean that she will definitely get a ‘non‐core’ portfolio, or having a woman in a masculine portfolio doesn't necessarily mean you are more likely to have a man in feminine portfolios. These effects are further complicated in coalition governments, where parties must also consider their coalition partners’ reactions to any ministerial appointments.

Therefore, in this article, I consider how the characteristics of portfolios, parties and governments, as opposed to an individual's characteristics, shape the allocation of women to government. While this approach has some costs in terms of the depth of analysis of party leader considerations, it enables an analysis of trends in women's appointment. Understanding these trends provides a large‐scale understanding of where and when party leaders decide to appoint women to different portfolios and a Europe‐wide insight into which factors can lead to more or fewer women in the government. After all, it is these decisions that have an impact on how government departments are run and, as such, public policy.

Office

‘For the most important portfolios, I need to pick ministers that are loyal to me’

When considering office‐seeking motivations, party leaders are concerned with holding on to government portfolios (Müller & Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999: 9) and so seek to appoint credible ministers who maintain a high level of loyalty to the party leader. As cabinet ministers have a very high level of autonomy over their portfolio, they have the capability to undermine their principal in the formation and implementation of policy in the areas under their jurisdiction. Party leaders as principals can be subject to adverse selection problems with ministers as their agents, since leaders do not have complete information on the competence or policy positions of ministerial candidates prior to their selection (Strøm Reference Strøm2000: 270–271). Therefore, party leaders screen ministerial candidates ex‐ante in order to identify whether they are suitably experienced for the role (Huber & Martinez‐Gallardo Reference Huber and Martinez‐Gallardo2008).

While part of this ex‐ante screening for important political portfolios will be based on the ministerial candidate's views, voting record and policy positions (Rose Reference Rose1987), this pre‐appointment screening process will also be based on less tangible informal links and relationships of trust. These close ties constitute protection against personal unreliability as they provide incentives for members of the government to act openly and form a sense of allegiance to the leader (Blondel & Manning Reference Blondel and Manning2002: 463). Consequently, the process of ministerial selection is functionally dependent on social networks built on trusting relationships (Moury Reference Moury2011). For many reasons, these high‐trust networks are relatively closed to women (Annesley & Gains Reference Annesley and Gains2010: 463). For example, Feminist Institutionalist scholars have highlighted how the rules and practices that shape formal and informal institutions lead to different outcomes for men and women (Chappell & Waylen Reference Chappell and Waylen2013). Chappell (Reference Chappell2006) suggests there is a ‘gendered logic of appropriateness’ which operates in political institutions and excludes women as an ‘other’ in the close social networks that govern political institutions. This is coupled with the fact that women are often prohibited, as carers, from engaging in the activities that build trusting relationships such as social events and networking activities. This ‘homosocial reproduction’ can prevent women from entering the close networks that become the selection pool for the most important offices of state (Kanter Reference Kanter1977).

When allocating ministers to the prestigious ‘core’ ministries of state, these informal networks become particularly important. In the most visible, powerful and influential portfolios, party leaders who seek to hold onto political office need to assure themselves that they will not be betrayed or let down by their ministers. A public betrayal through a ministerial coup could be a party leader's downfall. As such, this ex‐ante screening through existing political networks is especially rigorous in the case of the most prestigious and powerful ministerial portfolios, such as finance and defence (Huber & Martinez‐Gallardo Reference Huber and Martinez‐Gallardo2008).

Therefore, the gendered effects of women's limited access to high‐trust political networks will have the most significant effect for the highly important and prestigious ‘inner circle’ positions within the government. Existing analyses of ministerial allocations at the government level find that women are less likely to be appointed to the most important and highly trusted positions within the government (Claveria Reference Claveria2013; Krook & O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012).

H1: Appointments to ‘core’ ministerial portfolios are less likely to be female.

However, it is not just the ‘core’ portfolios that are of importance to party leaders and political parties more broadly. Even party leaders themselves have contested such categorisations. After receiving criticism for the gendered allocations of portfolios to his shadow cabinet, British opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn sought to emphasise that women had been appointed to the real ‘top jobs’ – the policy areas which mattered most to his party including health, education and social care (Dathan Reference Dathan2015).

When party leaders appoint their cabinet, they are very aware of the fact that some cabinet portfolios are of a higher issue salience than others (Warwick & Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006; Druckman & Roberts Reference Druckman and Roberts2007). However, this salience may be quite distinct from the ‘inner circle’ prestigious government positions. Parties have commitments to policy areas that are particularly salient for them, and analyses of the portfolio allocation process suggest that in coalitions, parties are more likely to be allocated policy areas that are particularly salient for them (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Greene & Jensen Reference Greene and Jensen2017). For example, green parties are more likely to be allocated to environmental or climate change portfolios (Poguntke Reference Poguntke2002). To those green parties, the environmental portfolio is equivalent to the ‘core’ offices of state. Thus, the same informal and formal network dynamics will be in operation for high‐salience portfolios as there are for ‘inner circle’ or ‘core’ positions. Consequently, fewer women are likely to be appointed to these high‐salience ministerial portfolios.

H2: Ministers appointed to portfolios where the policy areas are of high salience to political parties are less likely to be female.

‘I am from a left‐wing political party, and have more women in my ministerial candidate pool’

However, intra‐party gender politics varies within and between European political parties. Analyses that begin to lift the lid on the black box of decision making within parties identify a complex picture of multiple competing actors and interests (Greene & Jensen Reference Greene and Jensen2014; Greene & Jensen Reference Greene and Jensen2017). Yet, within this complex picture of decision making at the party level, the dynamics of gender in appointing ministers have received little attention. In the European context, these party‐level characteristics are particularly important as most governments are not single party ones. Therefore, the overall allocation of women to ministerial positions across the government depends on multiple parties, each with different ideological perspectives, policy agendas and policy preferences.

Left‐wing political parties are aligned with the values of egalitarianism, and this means that these parties are more likely to have an ideological commitment to gender equality than right‐wing political parties. For this reason, especially since the ‘second wave’ of feminism, leftist political parties are seen to be more ‘female friendly’ than their right‐wing counterparts. Existing analyses of women's representation in parliament find that left‐wing parties typically exhibit a greater representation of women than right‐wing parties (Rule Reference Rule1987; Norris & Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995; Matland Reference Matland1998; Kenworthy & Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2000; Caul Reference Caul2001; Chiva Reference Chiva2005).

Left‐wing parties are likely to have stronger connections to feminism and feminist movements, and left‐wing parties are more likely to implement party quotas (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006; Krook Reference Krook2007; Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall, Dahlerup and Leyenaar2013). Women are more likely to be appointed to ministerial positions where governing parties have adopted gender quotas (Claveria Reference Claveria2014). Therefore, although party quotas do not directly stipulate which policy areas women ministers should be allocated, they can have an indirect impact on the number of women in the selection pool for ministerial portfolios. Thus, left‐wing parties are more likely to have more women high in their party hierarchy that are suitable for appointment to a ministerial position than right‐wing parties.

Empirical studies of the representation of women in the cabinet governments at the government level suggest that this is the case. Cabinets led by prime ministers from left‐wing parties have more women ministers than those led by prime ministers from right‐wing parties (Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2000; Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2005; Claveria Reference Claveria2014). Additionally, leaders of left‐wing parties are more likely to hold feminist views than their right‐wing counterparts (Bashevkin Reference Bashevkin2014; Campbell & Childs Reference Campbell and Childs2015). Therefore, both male and female leaders of these parties are less likely to adhere to the traditional public/private divide when considering the allocation of roles and competencies of female ministerial candidates. For these reasons, it is anticipated that leftist parties within the government will be more gender‐balanced in their allocation of portfolios than right‐wing political parties.

H3: Less gender differentiation in portfolio allocation in left‐wing parties than right‐wing parties.

Policy

‘She's a woman so will know about that kind of thing’

Over the last 30 years, there has become an increasingly pervasive norm of women gaining access to powerful fora of decision making – what Jacob et al. (Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014) call the ‘gender‐balanced decision‐making norm’. This norm has set expectations that women will be appointed to decision‐making bodies across the public and private sector to represent and defend the interests of women. This ‘substantive representation’ relies on women as political actors to represent the interests of women across the country (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967), so party leaders may seek to appoint women to the government to represent ‘women's interests’ (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Celis & Childs Reference Celis and Childs2008). Consequently, party leaders will evaluate the skills and expertise of women against their view of how they will best represent women in the policy areas which matter to women. As women continue to be associated with policy areas related to the home, children, health and the elderly, they will be more likely to be appointed to these policy areas than the ‘masculine’ portfolios concerned with the public sphere of the economy and national security. Women will be more likely to be appointed to policy areas which pertain to the ‘private’ sphere of life, such as children and family portfolios, women's affairs, education, welfare, and health and social care (Krook & O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). Therefore, we will observe more women in the ‘feminine’ policy areas than traditionally ‘masculine’ areas such as agriculture, construction, military and foreign affairs (Mackay Reference Mackay2008).

Further, some women with successful political careers may well have championed their personal knowledge and experience of the feminine policy areas such as health and education. Therefore, when party leaders are assessing who will be best placed to lead a government department in one policy area, they may be more likely to select an individual who has carried out their politics as a clear advocate of ‘women's issues’ in that policy area (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2011).

Divisions in the gendered nature of policy areas are not necessarily linked to the prestige of the ministry, as some traditionally feminine areas can command large budgets and have a high public profile. However, the gendered view of policy effectiveness, as well as the skills, experience and areas of interest to female ministerial candidates, can lead to more women in the ‘feminine’ ministerial portfolios.

H4: Ministers appointed to ‘feminine’ portfolios are more likely to be female.

Votes

‘My appearance as a non‐sexist party leader depends on this’

The high‐profile process of announcing a new government is part of the government's calculated interaction with the public and sends an important message about the party's image and intention. Some voters are more concerned with the gender balance of their preferred party's ministers. Any governing party leader must be aware of ‘the picture – often a literal photo in the press – presented by their cabinet’ (Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2009: 4). For example, the leader of the British Liberal Democrats, Nick Clegg, was widely criticised in the British media for failing to appoint any women to the cabinet during the party's time in coalition government (Leftly Reference Leftly2014). On the other hand, the leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, José Zapatero, pledged a gender parity cabinet before the 2008 Spanish general election, and in 2005 the newly elected leader of the British Conservatives, David Cameron, pledged that one‐third of his ministers would be female by 2015 (Heppell Reference Heppell2012). These pre‐election pledges show how some party leaders attempt to appeal to their voters based on their appointments to the government.

Party leaders are concerned with balancing interests when they announce a government, and ministerial selection can be used as a tool to signal the interests of various geographical, intraparty or sectorial groups (Mershon Reference Mershon2001; Ono Reference Ono2012). Since women constitute half of the population, some party leaders are incentivised to gender balance their ministerial appointments in order to maximise votes by ensuring that the government (and the party) appears to represent the electorate. Others party leaders are motivated to use their ministerial appointments to convey the party's commitment to ‘masculinist’ values.

This is not to say that women voters will find a cabinet unsatisfactory on the basis of a gender imbalance alone, or that women are mobilised enough as a group to lobby for more representation. However, appointing women to the cabinet can still become an important signal from the government to the electorate.

Not all party leaders across time and contexts feel the same amount of pressure to appoint female ministers, or to appoint them to the most influential portfolios. To a degree, these concerns may also map onto the traditional left‐right political partisan spectrum; however, these attitudes may also vary across other dimensions of political competition, such as socially conservative or liberal political attitudes (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994). For example, the traditional blue‐collar voters for left‐wing political parties may have less progressive gender attitudes than otherwise socially conservative elites who traditionally vote for centre‐right parties. Therefore, individual‐level voter attitudes aggregated at the party electorate level can have an important effect on the relative pressure to appoint women to diverse portfolios across the government.

H5: Less gender differentiation in portfolio allocation by parties whose voters have more gender‐equal attitudes.

Data and methods

In order to test these hypotheses, I combine multiple datasets on governments, parties and voter attitudes. For the composition of European cabinets, I use the Seki‐Williams government and ministers data (Williams & Seki Reference Williams and Seki2016), which extends and digitises the Woldendorp, Keman and Budge government composition data from the early 1990s through to 2014 (Woldendorp et al. Reference Woldendorp, Keman and Budge2000). This dataset details the name, gender, party, duration and other features for all government ministers, and also links their membership to other comparative datasets (Seki & Williams Reference Seki and Williams2014).

For this analysis, I draw on data on 29 European countries from the late 1980s until 2014.Footnote 1 The earliest government in this dataset is the Maltese Adami government, which was appointed on 14 May 1987. The most recent government is the Romanian Ponta government appointed on 17 December 2014. Within this dataset, an observation is the appointment of an individual to a portfolio within a government. In total, this dataset has 7,005 observations, and 3,657 unique ministers. Just over a quarter (26.5 per cent) of the ministerial appointees in the dataset are female.

The dependent variable in this analysis is the gender of the cabinet minister, as identified in the Seki‐Williams minister data. As the unit of analysis is the individual minister, the party‐level characteristics in this analysis (such as left‐right score and portfolio salience) are assigned to an individual based on the party the minister represents in government and the year in which they were appointed.

This categorisation of ‘inner circle’ portfolios (H1) is based on Claveria's (Reference Claveria2013) inner/outer typology of portfolios. The ‘inner’ portfolios are the closest advisors to the prime minister and have regular access to the government leader. These are vice‐president/deputy prime minister, defence, finance, economy, home office and foreign affairs. All other portfolio areas are seen as specialised areas which may not have regular access to the prime minister.

For the salience of the portfolios to the political party (H2), I have used the Chapel Hill Expert Survey trend file data, which provides an annual expert evaluation of the salience of a range of substantive policy issues to political parties (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker2015; Polk et al. Reference Polk2017). This dataset uniquely provides a time‐variant party‐specific evaluation of policy area salience. An issue has been graded as high‐salience if it scores higher than nine on the ten‐point salience score. A portfolio is high‐salience when it maps onto the high‐salience policy area, or is the prime minister or deputy/vice prime minister. Of the 6,095 ministerial allocations with available data on salience in this dataset, 2,927 (48 per cent) are high‐salience.

To test the party‐level hypotheses that there is less gender differentiation in the portfolio allocation of left‐wing parties (H3), the left‐right score is operationalised through the ‘rile’ score of each governing party in the Comparative Manifestos Project (CMP).Footnote 2 This measure is an additive left‐right index, which serves as a summary indicator of the policy positions of political parties in their electoral manifestos (Budge et al. Reference Budge2001). The measure ‘could in principle range from –100 (the whole manifesto is devoted to “left” categories) to +100 (the whole manifesto is devoted to “right” categories)’ (Mölder Reference Mölder2013: 3). The range for governing parties is more limited: from –58 to 82. The left‐right score of the last manifesto coded before the appointment of the government is considered for each observation.

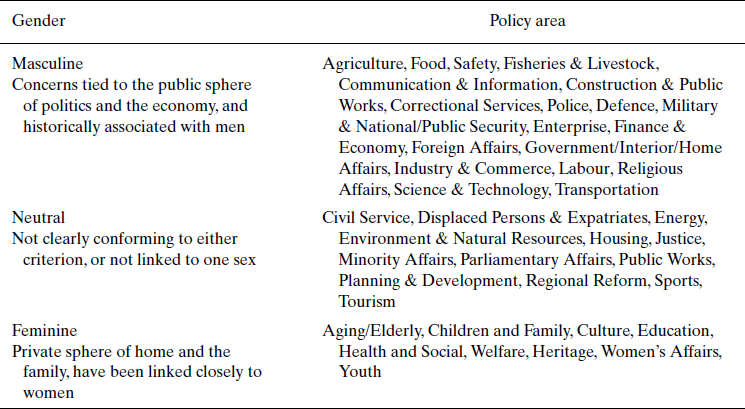

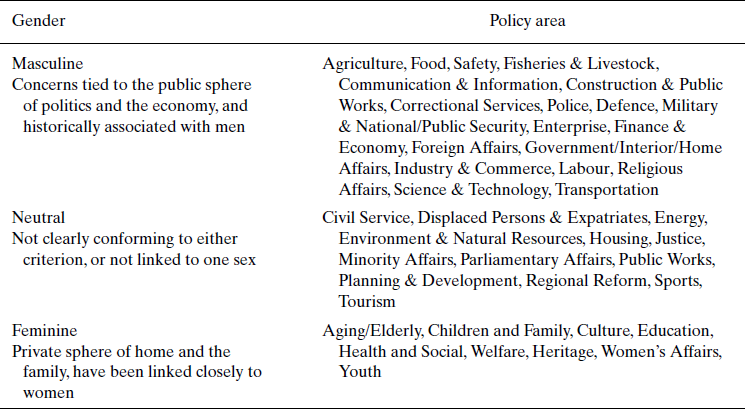

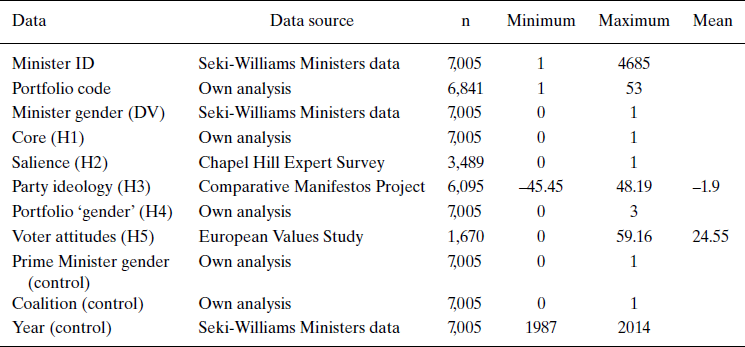

Policy areas have been identified as traditionally masculine, neutral or feminine (H4) based on their affiliations with the public or private sphere of politics and/or historical association with men or women (Krook & O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012: 844). Based on Krook and O'Brien's (Reference Krook and O'Brien2012) typology, I have categorised the ministries based on at least one policy area in the minister's title being from the masculine, feminine or neutral group (Table 1).

Table 1. Gender categorisation of portfolios

Source: Categorisation from Krook and O'Brien (Reference Krook and O'Brien2012).

I use survey data to examine the effects of the gender attitudes of the voters of each party (H5). I use the European Values Study (EVS) longitudinal dataset and grouped the responses based on responses to the question ‘e179‐ If there was a general election tomorrow, which party would you vote for?’ (European Values Study 2015). As a measure of gender attitudes within each party's voter base, I use these groups to calculate the percentage of respondents who agreed to the statement ‘c001‐ When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job than women’. This measure of gender attitudes provides a point of comparison between the voters of political parties.

The gender of the government's prime minister has also been included as a control variable, as the government being led by a woman may moderate some of the earlier hypothesised effects. For example, a woman may be more likely to have women in her close, trusting networks than a man. Further, the year in which the government is appointed is included as a control variable as there is a general trend towards increased women's representation over time.

I also include whether a government is a coalition government as a control variable in this analysis as governments with more than one party involved in portfolio allocation and ministerial selection may behave differently to single‐party governments. While parties in coalitions can be relatively autonomous in selecting ministers, they may have to consider the reaction of other parties in government (Debus Reference Debus2008; Kaiser & Fischer Reference Kaiser and Fischer2009). This could have an impact on the allocation of women to ministerial portfolios through constraining choices of plausible ministerial candidates, as well as parties’ and voters’ perception of the overall gender balance of the government. Table 2 provides an overview of all these data sources and some descriptive statistics.

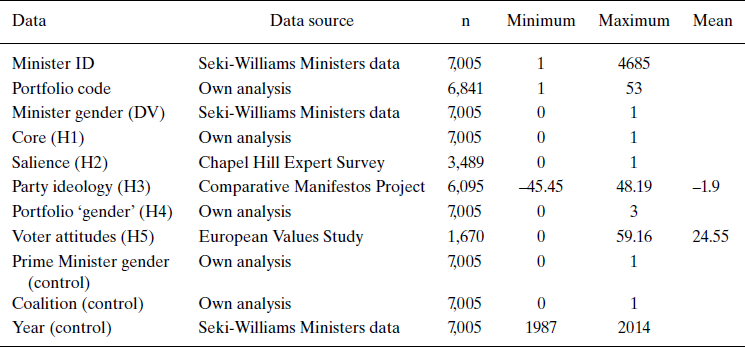

Table 2. Data sources and descriptive statistics

The results in this article are based on logistic (logit) regression modelling with country fixed effects, which are applied because, across the 29 counties in this analysis, there may be baseline differences in the propensity to appoint women to government positions, as well as the overall equality of opportunities for women. While incurring some costs in terms of identifying potential causal relationships across countries, fixed‐effects modelling enables this analysis to account for unobserved country‐specific sources of variation.Footnote 3

The dependent variable in this analysis is the gender of the cabinet minister, where a female minister is coded as 1, and a male minister as 0. The logistic formula is stated in terms of the probability that the gender of the minister (Y) = 1 (female), which is referred to as

![]() .

.

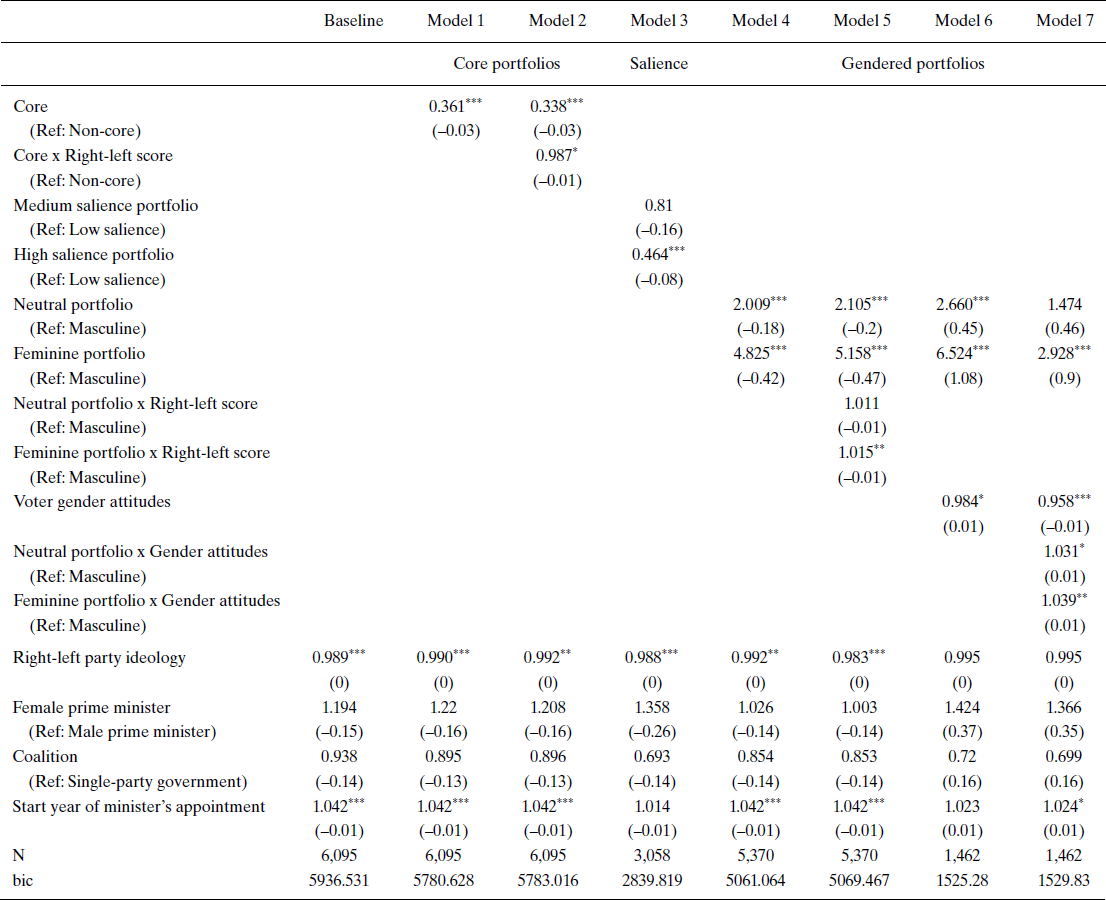

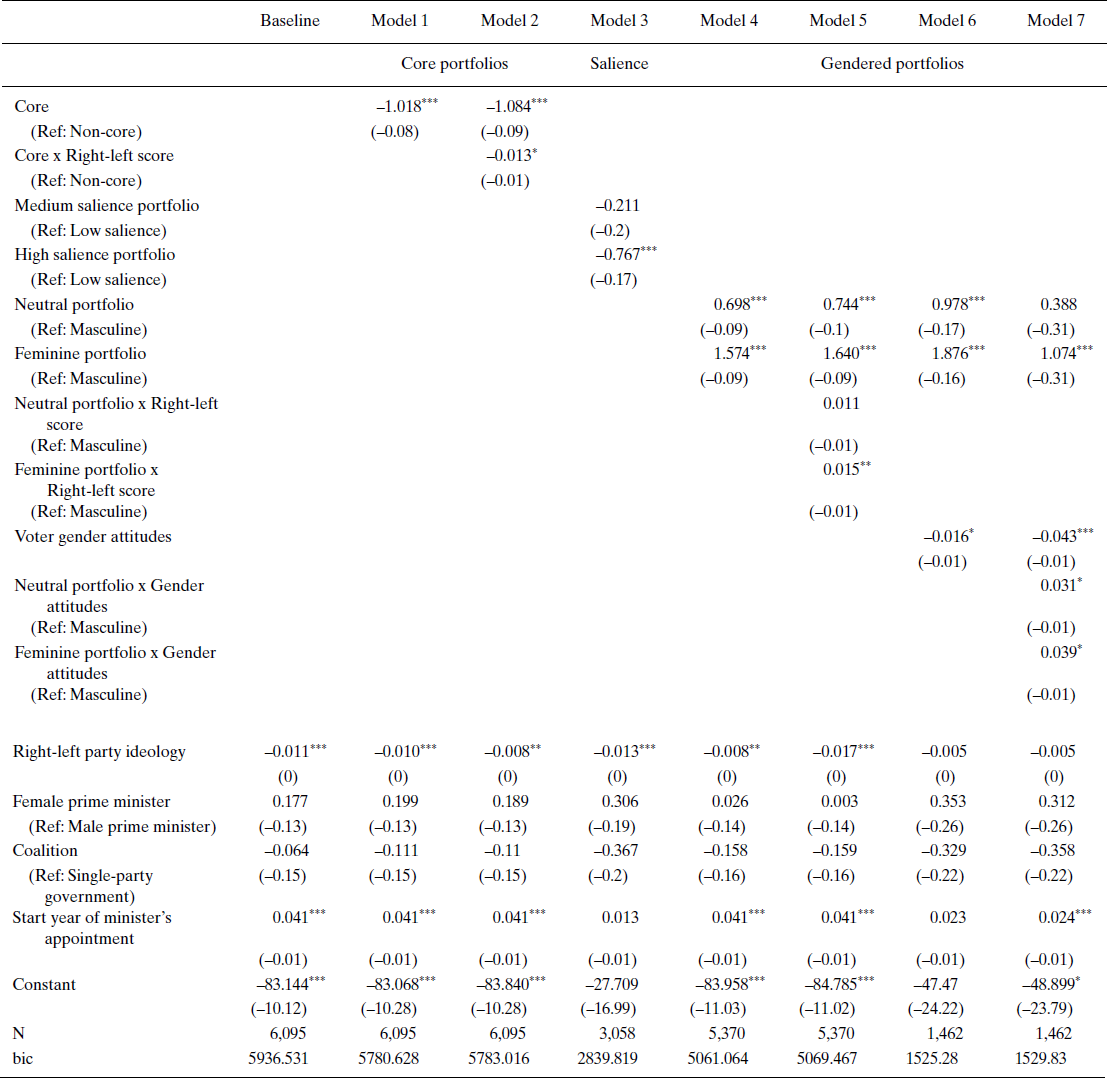

For ease of interpretation, odds ratios are presented in Table 3. An odds radio coefficient above 1 indicates a positive effect (the appointment is more likely to be a woman) and a coefficient below 1 a negative effect (the appointment is less likely to be a woman). The predicted margins and point predictions discussed are the probability of a positive outcome (a female appointee) assuming that the random effect is zero.

Table 3. Odds ratios

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The logit coefficients for this analysis are provided in the Appendix, and should be interpreted as the log odds increase of the probability of the minister being female predicted by a 1 unit increase in the covariate, holding all other independent variables constant.

Analysis

Are women less likely to be appointed to the core ministries of state than their male counterparts (H1)? A descriptive overview of the data suggests so. Between 1987 and 2014, no women were appointed to any of the core ministries in Malta. While Sweden has the most women appointed to these roles between 1989 and 2014, women are still in a significant minority, with only 10 per cent of appointments to core portfolios being allocated to women. Model 1 in Table 3 shows that an appointment to a ‘core’ portfolio is almost three times more likely to be a man than a woman (the odds ratio is 0.361), controlling for all other variables in the analysis. There is a stark gender difference between core and non‐core ministers: women are much less likely to be found in the most powerful and ‘inner circle’ political offices.

Gender differences in appointments to core portfolios are moderated by party ideology (H3). Only 15 per cent of the 219 cases where women were appointed to a ‘core’ portfolio were appointed by the parties in the farthest right quartile of parties of this dataset (where the left‐right score is greater than 7.21). The interaction term between whether a portfolio is in the ministerial core, and the left‐right score for a party shows that appointments to core portfolios by right‐wing parties are even less likely to be female than appointments to core portfolios by left‐wing parties.

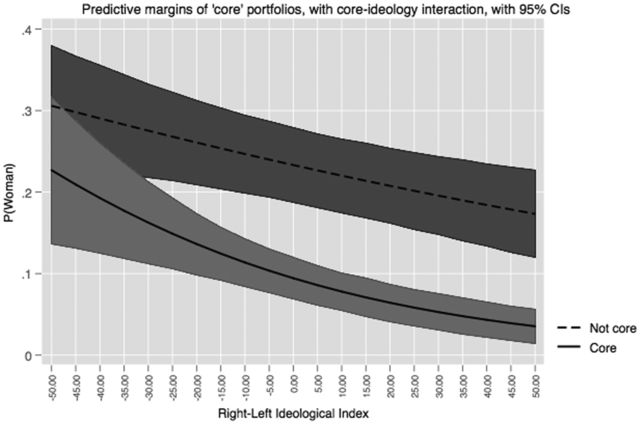

This is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the predicted margins of a minister being a female from model 2, with the interaction between party ideology and core portfolios. There is no statistically significant difference in the predicted gender of core and non‐core appointments by parties at the farthest left of the political spectrum, where the left‐right score is less than –30. These parties include the Social Democratic Party of Finland (SDP) in 1990, the French Socialist Party (PS) in 2012 and 2014, and the Belgian Socialist Party (PS) between 2007 and 2010, among others.

Figure 1. Predicted probability of ministers of core and non‐core portfolios being female, with core‐ideology interaction (95 per cent confidence intervals).

However, there is a significant difference in the gender of appointments to core portfolios for the majority (96.74 per cent) of governing parties in this dataset. Where the left‐right score is 30, as it was for the British Conservatives (C) or Greek New Democracy (ND) in the 1990s, the probability of a core appointment being female is 0.05. For a non‐core appointment the probability is nearly three times that at 0.19. This demonstrates the importance of considering party‐level factors when addressing the gendered nature of portfolio allocation in European governments as the allocation of women to core portfolios varies significantly across the left‐right political spectrum.

Time is also an important driver of this effect as appointments in more recent years are more likely to be female. For example, this model predicts that the likelihood of a German Free Democratic Party (FDP) appointment to a core ministry being female in 1991 is 0.06, but 20 years later in 2011 this had more than doubled to 0.13, despite a very minor rightwards shift in the right‐left score of the party (from 1.89 to 4.27).

In each of the models presented in this analysis, I have controlled for the gender of the prime minister. It could be expected that female prime ministers are more likely to have more women in their close social networks, and therefore be more likely to appoint women to core, high salience and ‘masculine’ or ‘neutral’ portfolios. The gender of the prime minister is not a statistically significant factor in the allocation of portfolios to women in any of the models presented in this analysis.

This study provides a unique insight into the importance and salience of ministerial appointments for political parties by drawing on expert surveys (H2). Model 3 shows that appointments to high‐salience portfolios are significantly less likely to be female. Indeed, appointments to high‐salience portfolios are over half as likely to be female than appointments to low salience portfolios (the odds ratio is 0.46). However, there is not a significant gender difference in appointments to medium‐salience portfolios.

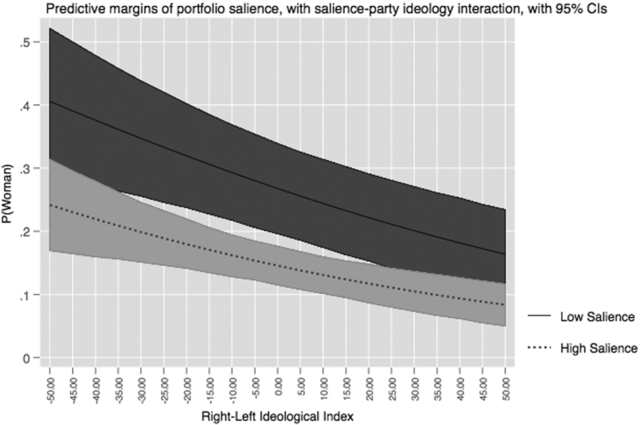

Party ideology has a significant impact on the likelihood of a high‐salience appointment being female. Figure 2 unpacks this further, and demonstrates a statistically significant difference in the predicted probability of a woman being appointed to high‐ and low‐salience portfolios in the political centre (when the left‐right score is between –35 and 25). This accounts for 92 per cent of the observations in the dataset.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of ministers of high and low salience portfolios being female (95 per cent confidence intervals).

For example, the Dutch portfolio of the Minister of Home Affairs and Relations with the Dutch Antilles was of high salience to the both the right‐wing People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), which has a left‐right score of 28.08, and the left‐wing Labour Party (PvdA), which has a left‐right score of 0.84. Yet the model's prediction of the likelihood of the Labour appointment to the post being female in 2007 (0.10) is almost twice that of the People's Party's appointment in 2006 (0.06).

The interaction between party ideology and the salience of portfolios is not statistically significant. This means that the relationship between the salience of appointments and the gender of ministers is not moderated by the partisanship of those appointing the government.

Ministers allocated to ‘feminine’ portfolios, such as women's affairs, children and family, or health and social care, are much more likely to be female than those appointed to masculine portfolios, such as military and foreign affairs, finance and the economy, or science and technology (H4). Only 15.65 per cent of all appointments to masculine portfolios in this dataset are female, as opposed to 37.37 per cent of appointments to feminine portfolios. As the results of model 4 in Table 3 shows, ministers appointed to feminine portfolios are 4.8 times more likely to be female than those appointed to masculine portfolios, holding the other variables in this model constant.

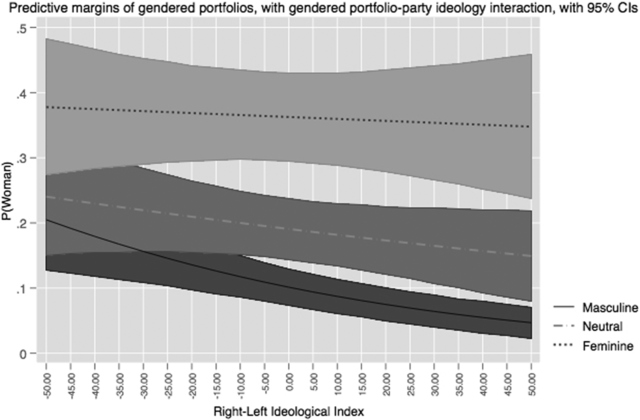

The effect of the gendered nature of ministerial portfolios on the likelihood of appointees being female is even stronger in right‐wing parties than left‐wing parties, as shown in model 5, which includes an interaction between party ideology and the gendered nature of portfolios. Parties on the political right of the ideological spectrum are less likely than leftist parties to appoint women to masculine and neutral portfolios.

This relationship is explored further in Figure 3, which plots the predicted margins of model 5. As this figure shows, for parties at the far left of the political spectrum with a (left‐right score less than –27), there is no statistically significant difference between the likelihood of appointments to masculine and feminine portfolios being female. However, this only accounts for 4.3 per cent of the observations in this dataset. There is no statistically significant difference between the likelihood of appointments to feminine, neutral and masculine portfolios being female for the most left‐wing third of the parties in this data (when the left‐right score is less than –10). As an example, the Portuguese Socialist Party (PS) had a score of –10.22 in 2005. However, this effect largely arises because the appointment of women to both masculine and neutral portfolios is very unlikely. When the left‐right score is –10, the model's predicted probability of an appointment to a masculine portfolio being a female is 0.12, and 0.20 for a neutral portfolio.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of ministers of masculine, neutral and feminine portfolios being female, with portfolio‐ideology interaction (95 per cent confidence intervals).

For parties on the political right, this effect is exacerbated. For centre‐right parties (with a left‐right score of 20) the predicted probability of an appointment to a feminine portfolio being female is 0.36. The prediction for a neutral portfolio is half this (0.17) and for a masculine portfolio is over five times less (0.07). Therefore, the model accurately predicts that the British Conservatives (left‐right score of 17.54), when appointing their 2014 reshuffle cabinet selected female Nicky Morgan as Secretary of State for Education, and male Michael Fallon as Secretary of State for Defence. Across the political spectrum, the likelihood of appointees to feminine portfolios being female remains relatively consistent, dropping from 0.38 to 0.35 from the very left (–50) to the very right (50), respectively, when controlling for the other variables in the model.

This analysis reveals a gendered divide in portfolio allocation across most governing parties across the political spectrum. Where women are appointed to ministerial positions, it is most likely to be in feminine policy areas, and on the political right women are unlikely to be appointed to masculine portfolios.

Over time, all appointments are marginally more likely to be female. For example, based on model 5, the probability of the Hungarian Socialist Party's (MSZP) appointment to the Ministry of Finance in 1994 being female was 0.06. By 2014, this had doubled to 0.14 (the party had also moved five points to the left in that time). Another illustrative example is Ireland's Fianna Fáil's appointments to the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform position. The probability of a woman being appointed increased from 0.30 in June 1997 to 0.41 in May 2008 (the party also moved leftwards by 15 points in that time).

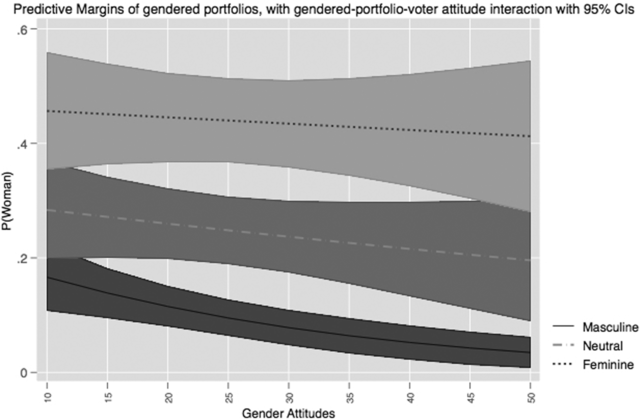

To what extent do the gender attitudes of a party's voters impact on the appointment of women ministers to government portfolios (H5)? The results from model 6 in Table 3 show (for the subset of cases where survey data is available) that parties whose voters have less progressive social attitudes are less likely to appoint women to neutral and masculine portfolios even when controlling for party ideology and time. The results from model 7, which include an interaction between party ideology and the gendered nature of policy areas, demonstrate that this effect is particularly substantial on the political right. Figure 4 plots the marginal effects of this analysis, and shows that the gender attitudes of voters have a statistically significant effect on the appointment of women to ministerial portfolios, especially in the allocation of masculine portfolios to women.

Figure 4. Predicted probability of ministers of masculine, neutral and feminine portfolios being female, with portfolio‐voter attitudes interaction (95 per cent confidence intervals).

For parties whose voters have less progressive gender attitudes, there is a large, statistically significant difference between the likelihood of appointments to masculine, feminine and neutral portfolios being female. In 15.7 per cent of cases in this data, more than 40 per cent of respondents voting for a party answered that ‘When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job than women’. These include the Italian Christian Democracy (DC) party and Ireland's Fianna Fáil (FF) in the early 1990s, and Greek New Democracy (ND) in 2012. For this group of parties, whose voters have less progressive gender attitudes, the predicted probability of appointments to masculine portfolios being female is 0.05.

Parties with voters with more progressive gender attitudes (where less than 10 per cent of voters answered that ‘When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job than women’) include the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the late 1980s and Danish Social Democracy (S) in the mid‐2010s. For these parties, the probability of a masculine appointment being female is over three times greater than the group of less‐progressive parties (0.17).

As Figure 4 shows, for parties whose voters have more gender‐equal social attitudes there is no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of appointments to masculine, neutral and feminine portfolios being female. This stands in marked difference to the group of parties whose voters have less progressive social attitudes towards women, where the predicted margins indicate that the probability of a woman being appointed to a feminine portfolio (0.42) is over eight times greater than appointments to masculine portfolios (0.05).

This lends evidence to suggest that party leaders are considering their voters’ views when appointing the cabinet, and that voter attitudes have a significant effect on the appointment of women to the cabinet. This indicates that changing perceptions of women's role in society may lead to a change in the policy areas allocated to women in government.

In all except models 3 and 6, time has a statistically significant impact on the allocation of portfolios to women: women are more likely to be appointed core, high‐salience and masculine portfolios over time. This reflects the results of existing analyses of the representation of women in elected and appointed political positions whereby women's representation increases over time (Krook & O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien2015; Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2016).

This analysis of the impact of coalition governments suggests that there is no statistically significant difference between coalition and single‐party governments in the allocation of portfolios to women ministers, including in the baseline model. That parties behave similarly in single‐party and coalition governments suggests that while coalition dynamics may play an important part in the allocation of parties to portfolios (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011), they do not necessarily have an impact on parties’ allocation of portfolios to women ministers. How coalition dynamics influence the allocation of women to ministerial portfolios could provide a fruitful area for future analysis.

Discussion and conclusions

Under which circumstances do women get appointed to different ministerial portfolios? In this article, I have addressed this question by considering how the policy‐, office‐ and vote‐seeking motivations of party leaders influence the allocation of women to ministerial portfolios across Europe. This analysis of 7,005 ministerial appointments across 29 European countries builds upon existing analyses of women's appointment to government positions (Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2009, Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2016; Krook & O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012) to provide an examination of how party and portfolio characteristics influence the allocation of appointment of women ministers. Both empirically and in terms of our theoretical understanding, I provide an approach by which to assess how the motivations we know shape government appointments also shape the role of women in those governments.

To the extent that party leaders are office‐motivated, they seek to ensure the ministers they appoint are loyal to them – particularly those they allocate to the most important portfolios. The motivation to have loyal ministers has a disproportionately detrimental effect on women, who are less likely to have access to the high‐trust networks which promote and engender these trusting relationships. This effect is played out across European governments: ministers appointed to both high salience and ‘core’ portfolios are less likely to be female. For the ‘core’ portfolios, this effect is moderated by party ideology as the gender gap in appointments is not present in left‐wing parties.

The effect of ideology in moderating the gendered nature of ministerial appointments is a consistent theme throughout this analysis. This suggests that a more gender‐balanced talent pool in left‐wing parties impacts the appointment of women to ministerial portfolios. These party‐level differences highlight the importance of looking beyond the representation of women in the government as a whole and considering trends in the characteristics of ministerial appointments at the individual level.

This analysis suggests that party leaders’ perceptions of the competencies of female ministerial appointments influence their portfolio allocation decisions. Women are significantly more likely to be appointed to ‘feminine’ portfolios than their male counterparts and are also less likely to be appointed to lead ‘neutral’ policy areas. The effect of these gender dynamics is moderated by party ideology, where women are over twice less likely to be allocated a ‘masculine’ portfolio in a right‐wing party than a left‐wing one. This shows how important the party ideology of governing parties can be in influencing the appointment of women ministers – the effect of which is not necessarily so prevalent in other elected and appointed political offices.

Winning votes matters to party leaders and this analysis of the appointment of women to the cabinet suggests that the attitudes of a party's electorate play a role in who they appoint to their top posts. In political parties whose voters have more progressive gender attitudes, women are significantly more likely to be allocated to masculine portfolios, even when controlling for party ideology. This significant effect indicates that the symbolic act of appointing women to the government can act as a means to communicate the party's perceptions about gender to voters. Where voters are receptive to women's presence in different policy areas, the political parties meet this expectation.

Based on this analysis, which emphasises the importance of party‐level factors, future research could turn to exploring how other party‐level factors, such as party selection pools and intra‐party groups and networks, impact on the appointment of women to public office. Building on this theoretical framework, as well as O'Brien et al.’s (Reference O'Brien2015) study of female party leaders and Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson's (Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2016) detailed investigation of the allocation of women to presidential cabinets, future research could consider how political parties and their leaders play a role in who is appointed to the government.

The findings of this analysis also have important implications for those who seek to see more women around the cabinet table and less gender differentiation in the allocation of portfolios. First, voter attitudes about women's role in society and the economy appear to have an impact on the gender composition of the cabinet. Therefore, working to change societal attitudes towards women leaders and politicians can influence who gets represented in the top jobs. Second, party ideology is a moderating factor in the process of government appointments which plays an important part in determining which portfolios women are allocated. This evidence suggests that, in general, there is less gender differentiation in portfolio allocation in left‐wing parties than right‐wing parties. Third, across the political spectrum, women's competencies and interest in the more ‘masculine’ areas of government may be overlooked due to gendered conceptions of ‘who is good at that kind of thing’. By not appointing competent women who may be interested in ‘masculine’ policy areas, and men who have experience and interest in the ‘feminine’ areas of government, party leaders are not maximising the policy competence of their top appointments. Due to the importance of ministers for the government's successful implementation of their policy program (Laver & Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996), all party leaders should be interested in ways in which to maximise the experience of their government appointments. This analysis shows that there is still work to be done in this area.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of a United Kingdom Economic and Social Research Council funded PhD, award number 1495863. I am grateful to Dr Ed Morgan‐Jones and Dr Lucy Barnes for their valuable insights on this project. This article was previously presented at the 2017 European Political Science Association annual meeting, the 2018 Political Studies Association annual conference and the University of Kent Comparative Research Group. I would like to thank participants at these meetings, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Appendix: Logit coefficients

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.