Introduction

Study of Neolithic stone axehead production in Britain and Ireland has, to date, largely neglected the Midlands in favour of those upland regions that are home to the well-known extraction sites of the period like Great Langdale (Group VI), Graig Lwyd (Group VII), Tievebulliagh (Group IX), and North Roe, Shetland (Group XXII). In part, this bias might be due to the visibility of monuments (or rather the lack of them) coupled with relatively low numbers of small finds; the Midlands has been long famed for its extensive tracts of medieval ridge and furrow, which is likely to have obscured much earlier data. Nevertheless, the River Trent is an important west–east/north–east artery and axeheads, particularly of Groups VI and VII, are distributed along the middle and lower reaches of the river (see distribution maps in Clough & Cummins Reference Clough, Cummins, Clough and Cummins1988, 270–1). Whether the river provided a focal point for settlement or indeed a boundary during the Neolithic is something that stone axehead distribution might eventually help point towards.

The greater number of axeheads found in the region are of Group VI, particularly north of the Trent, all evidently transported from Cumbria, and it might seem surprising that local rocks were not used to a much greater degree. However, the source of Group XX artefacts has been argued to be situated within the Charnwood Forest area of Leicestershire ever since the group was first identified in the late 1950s (Shotton Reference Shotton1959; Reference Shotton, Clough and Cummins1988; Moore & Cummins Reference Moore and Cummins1974, 65; Clough & Cummins Reference Clough, Cummins, Clough and Cummins1988, 47; Bradley Reference Bradley1989a; Reference Bradley1989b). Subsequent research at that time, mainly based on the examination of petrological thin sections, was unable to determine a precise petrological match between artefact and outcrop, though it remained likely that the source of Group XX lay somewhere in Charnwood Forest. Pinpointing a source for Group XX artefacts could not only be a crucial step in exploring the regional Neolithic but also may provide a catalyst for the further investigation into the extraction, manufacture, and dispersal of axeheads in the Midlands.

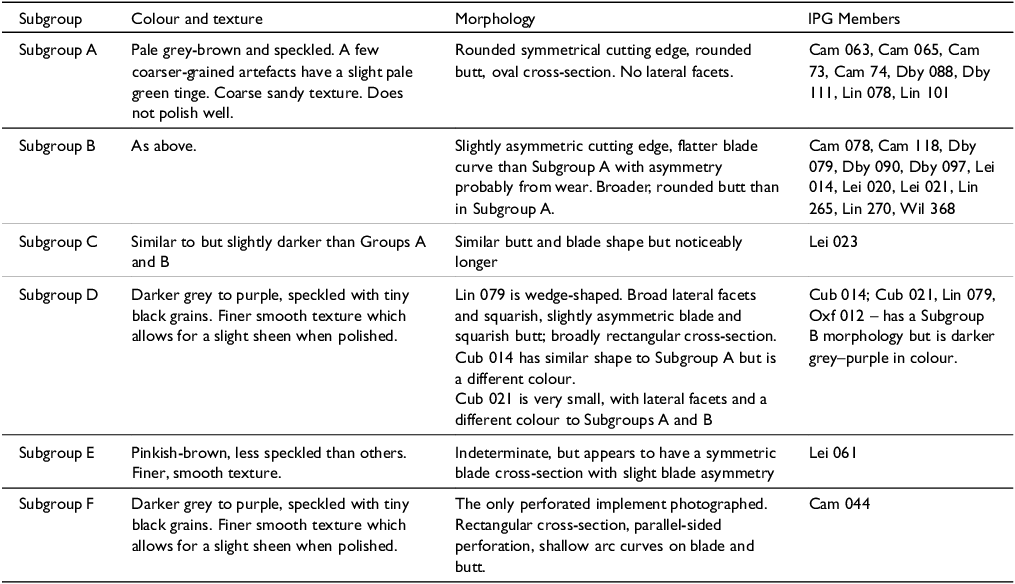

Photographic evaluation of 26 Group XX artefacts showed that there are six morphologically distinct subsets (Table 1). Two of these, Subgroups A and B, are petrologically similar, whilst the remaining four, a minor component, are sufficiently dissimilar to Subgroups A and B to warrant reassessment of their inclusion in Group XX. The determination of Subgroups A and B leads to the probability that the material was not extracted or collected loose on an ad-hoc basis, but that there are one or perhaps two distinct manufacturing centres and thus narrowing down the source to a few rock exposures provides us with a much smaller target area for future archaeological investigation. As only 26 of the 134 have been photographed and studied in detail, Subgroups C, E and F (although only having one member each) remain, for the moment, included as further work on Group XX axeheads may reveal new members of these Subgroups.

Table 1. Summary of the six morphologically recognised Group XX subgroups. As only 26 of the 134 members have been examined by the authors, the inclusion of single-member subgroups is in anticipation that there are further examples in the 108 artefacts yet to be photographed/examined in detail.

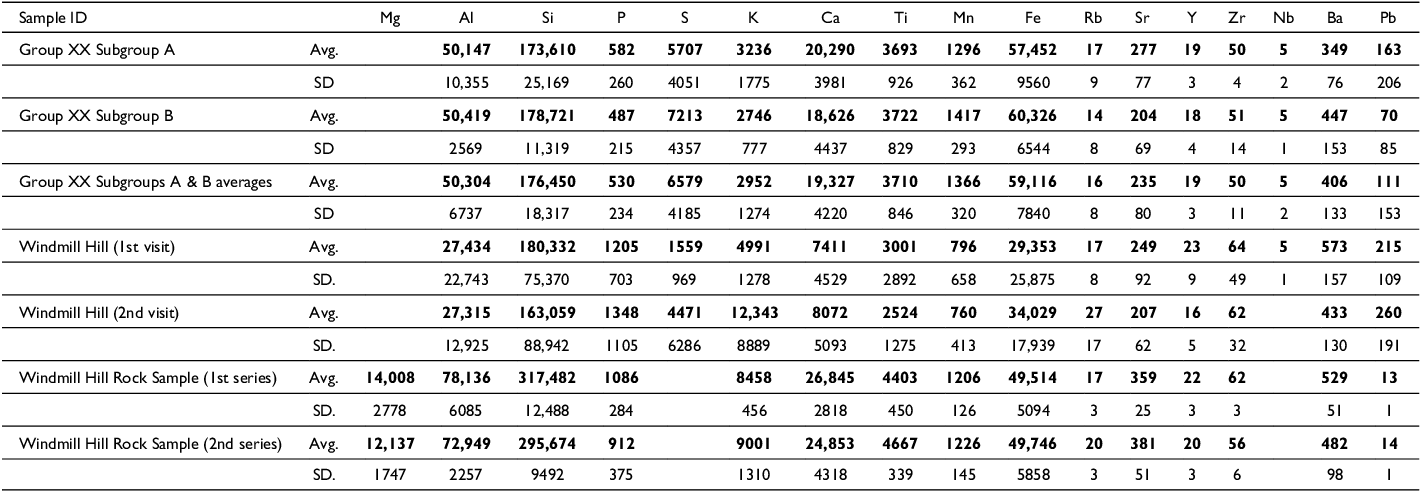

Reassessment of petrological thin sections and examination of axehead macroscopic petrology of 22 existing artefacts and 31 rock exposures revealed the potential rock source to be in the east of Charnwood Forest, within the geological Bradgate Formation. Additionally, portable X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF) was used to obtain elemental concentrations for the 22 Group XX artefacts, which allowed the determination of, and average element concentration for, Group XX (Table 2 & Supplementaries S2, S3). The same pXRF analyser, operating on the same settings, was used to obtain between 2–6 measurements at each of 17 Charnwood exposures, producing a total of 107 analyses. In addition, pXRF analyses of eight sliced rock samples was used to complement examination of the field measurements (details in Supplementaries S1, S4).

Table 2. Group XX Subgroups A & B: pXRF-determined elemental averages (in ppm) and associated standard deviations, plus summary averages and standard deviations of the Windmill Hill exposure and its associated rock sample. The measurements were obtained using an Olympus Vanta-M pXRF utilising its ‘Geochem 3-beam’ setting with beam times 60:30:20 seconds respectively. Subgroup A is the average of eight artefacts assigned to this group; Subgroup B is the average of ten artefacts assigned (see Table 1). ‘Subgroups A & B’ presents the combined averages of all artefacts. The Windmill Hill exposure was visited twice; averages and standard deviations are presented for the first (four measurements) and second visit (ten measurements). A sample of Windmill Hill material was measured on a flat, sawn surface in the laboratory (first series: three sets of two overlapping measurements/pXRF not moved; second series: four non-overlapping measurements). Where the concentration was below the pXRF level of detection (LOD), the cells are left blank. Further pXRF data and a range of bivariate plots used to examine the artefacts and outcrop is contained in Supplementaries 3 and 4.

Together the five datasets of archaeological (historical), geospatial (distribution, Figure 2), morphological (Figures 3–4, and Table 1), petrological, (Figures 5a & b) and pXRF analyses (Table 2) combine to present the likelihood that the immediate area near the Windmill Hill exposure of the Bradgate Formation, next to Woodhouse Eaves, is close to or indeed contains the source of Group XX material.

Figure 1. Location map with the research area inset. Charnwood Forest lies north-east of Leicester and contains the Neoproterozoic Ediacaran volcanistic rocks previously suggested as the source of Group XX (map developed QGIS v.3.40.4 ‘Bratislava’, plus British Geological Survey Open Source data: Solid Geology 1:50k Bedrock, ArcGIS Open Source ‘World Hillshade’ and Ordnance Survey Open Licence Mapping Data).

Figure 2. Distribution of Group XX artefacts based on revised location data in version 9a of the Implement Petrology Group Master Catalogue (Markham in prep.). Windmill Hill (black square) is now believed to be close to the actual source for the group.

Figure 3. Group XX axehead morphologies (photos: Mik Markham, Leicester Museum, Lincoln Museum, Sheffield Museums Trust & Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology).

Regional neolithic

Topographically, Charnwood Forest is a small upland area situated in the north-east of modern Leicestershire little more than 10 km south of the River Trent (Figure 1). The latter is an important artery that separates Charnwood from the high ground of the Peak District to the north, but the area is otherwise a lowland zone, landlocked and located in the centre of England. Despite its geographical centrality, it is an area that has been far from central to accounts of the Neolithic in Britain and Ireland (Clay Reference Clay1999, 1; Reference Clay, Brophy and Barclay2009, 92). Patrick Clay (Reference Clay1999, 1) has chalked up this oversight to the poor visibility of sites from the period as well as a ‘lack of fieldwork and pre-conceptions rather than a genuine lack of an archaeological resource’. Indeed, traces of fourth and third millennium BC activity are increasingly being recognised throughout the region and its immediate vicinity as a result of commercial archaeology (for overviews, see Clay Reference Clay1999; Reference Clay and Cooper2006: for the Trent valley see Knight & Howard Reference Knight, Howard, Knight and Howard2004); however, because of agricultural works during historic and recent times, much of the evidence that would have been above ground has been ploughed out. Consequently, though monuments are present in the region, much of the material record comes from sub-surface features and lithic scatters (Clay in Speed Reference Speed2015, 29). Nevertheless, geophysical survey has revealed a causewayed enclosure at Husbands Bosworth in southern Leicestershire (Clay Reference Clay1999, 7) and there are further examples to the west at Mavesyn Ridware and Alrewas in Staffordshire (Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Dyer and Barber2001, 155; Knight & Howard Reference Knight, Howard, Knight and Howard2004, 62–3). On the terrace to the north of the Trent, and significantly almost facing Charnwood, lie two cursus monuments at Aston (Gibson & Loveday Reference Gibson and Loveday1989) and Potlock respectively (Guilbert & Malone Reference Guilbert and Malone1994). Additionally, possible ploughed-out Neolithic barrows, both long and round, are visible as crop and soil marks on aerial photographs (Loveday Reference Loveday1980, 86–7; Clay Reference Clay and Cooper2006, 75).

Figure 4. Subgroup A and B axeheads: Subgroup A axehead Lin 101 from West Rasen, Lincolnshire and Subgroup B axehead Dby 090 from Cross Platts Plantation, Middleton, Derbyshire (photo: Mik Markham, Lincoln Museum and Sheffield Museums Trust).

Immediately east of Charnwood near the confluence of the Rivers Soar and Wreake, evidence for activity spanning the Neolithic is becoming increasing apparent with two sites near Rothley, a village south of Mountsorrel. At Rothley Temple Grange, a feature interpreted as an Early Neolithic sunken-featured structure was located at the centre of a series of pits including five that were ‘large, shallow and irregularly shaped’ with fills containing Carinated Bowls and worked Early Neolithic flints (Speed Reference Speed2015, 4). A single radiocarbon date taken from the upper fill of one pit yielded a date range of 3510–3340 cal BC (95% probability: Lab no Ua-40795) (Speed Reference Speed2015, 12). Additionally, a series of pits were uncovered dating from the Middle to Late Neolithic at nearby Rothley Lodge Farm (see Clay & Hunt Reference Clay and Hunt2016). Alongside the pottery sherds, flint tools, and animal bones found across these features were several stone artefacts, including a sandstone rubber and a ground flint axehead that had been fragmented by fire and found in the fill of one pit. Moreover, Patrick Clay and Leon Hunt (Reference Clay and Hunt2016, 24–5, 32–4) highlight two features, each containing an axehead that they identified as belonging to petrological Group XX, amongst a scatter of Late Neolithic material.

Group XX

Group XX stone axeheads form a petrological grouping of artefacts made from an epidotised andesitic tuff which may also be described as an epidotised tuffaceous sandstone. There are currently 34 petrologically recognised stone axehead ‘Groups’ in Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, and Brittany (see Clough & Cummins Reference Clough, Cummins, Clough and Cummins1988), all resulting from work since 1935 to identify the precise source of material used for artefact manufacture. The output of some implement petrology groups clearly dwarfed that of Group XX: the number of pieces assigned to Group VI, for example, currently sits at 1697 (Markham personal research: Implement Petrology Group catalogue v 9D) and axeheads of the ubiquitous southern flint will do likewise. The grouping enabled the recognition of several ‘axe factory’ sites with subsequent analysis of artefact distribution providing important clues as to social structure and interchange both within Britain and with Ireland and the European mainland in the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. Based on the lack of evidence for finished products found at the respective locales, these are now considered to be quarry or extraction sites and the roughing out of artefacts for finishing is thought to be carried out elsewhere (see e.g. Edmonds Reference Edmonds1999, 46–8, 51; Topping Reference Topping2021).

While there is a distinctive petrological signature reported for Group XX taken from artefacts (Figure 5a), the precise source of the rock has been a matter of conjecture for over 65 years. Frederick W. Shotton (Reference Shotton1959) of the Lapworth Museum, Birmingham University, first identified this ‘very distinctive rock’ as a tuff, differentiating it from the rock of the Group VI (an epidotised tuff) Cumbrian axeheads found in abundance in nearby Derbyshire, the difference being based on the lack of quartz in local epidotised tuffs. Shotton identified an area close to the western fringe of the Charnwood Forest near Spring Hill, ‘Beacon Ashes’ (SK 450158±200 m), as a potential source, which places it as part of the Whitwick Volcanic Complex (Strange et al. Reference Strange, Carney and Ambrose2010, 6), close to outcrops of Grimley Andesite, Peldar Dacite Breccia, and Sharply Porphyritic Dacite (Shotton Reference Shotton1959, 143). This area has been extensively quarried since Shotton’s assessment, and it has not been possible to visit the Spring Hill site, as it has been destroyed by quarrying in the intervening decades. However, re-examination of petrographic thin sections from within the quarry and around its fringe, coupled with subsequent pXRF analyses, have allowed the authors to conclude that this area is most probably not the source of Group XX. Geologically, the ‘Beacon Ashes’ are now identified as part of the Beacon Hill Formation (BGS online database 2025) and rocks from the Beacon Hill Formation are unlikely to have been the source of axehead material, as it is petrologically and geochemically different. Further, current geological maps do not show any outcrop of the Beacon Hill Formation in the vicinity of Spring Hill, which is surrounded by rocks from the Whitwick Volcanic Complex. We cannot repeat Shotton’s identification, as there is insufficient information to identify which thin section Shotton used, but on the basis of our work it is considered highly unlikely that the now missing ‘Beacon Ashes’ were the source for Group XX.

Figure 5. a) Petrological thin section images from Nfk 120, from Feltwell, Norfolk, the Group XX reference (taken by R.V. Davis, then Chair of the Implement Petrology Group). Photographed in reflected light (left), plane polarised light (centre), and cross polarised light (right). Top row: field of view 4.5mm, x40 magnification; bottom row: field of view 1.7mm, x100 magnification (photos: Mik Markham). b) British Geological Survey petrographic thin sections E1838 & 1895 from Windmill Hill, illustrating the epidotised andesitic tuffaceous nature of the rock. Photographed in reflected light (left), plane polarised light (centre), and cross polarised light (right); all images field of view 4.5mm, x40 magnification (photos: Mik Markham/British Geological Survey).

Further work was carried out in the 1980s by Philippa Bradley, whose undergraduate dissertation explored the, then available, petrology and compared five thin sections from samples taken from outcrops across the Charnwood region to those of three Group XX axeheads (Bradley Reference Bradley1989a). Sites at Charnwood Lodge, Strawberry Hill Plantation, Warren Hills, Beacon Hill, and Chitterman Woods were investigated, of which thin sections from Strawberry Hill Plantation and Charnwood Lodge compared well with the axeheads; the former site is on Benscliffe Breccia and the latter is on Volcanic Formation Breccia. Both rocks are, however, strongly cleaved and Shotton (Reference Shotton1959, 142), had formerly considered that the raw material used for axeheads ‘would need to be uncleaved and to be jointed in such a way as to give rectangular blocks at least 9 inches [23 cm] long from which flaked roughouts could be fashioned’. Philippa Bradley’s work demonstrated the variation in the Charnwood rocks and that it would be difficult for petrology alone to identify the source (Bradley Reference Bradley1989b, 185).

The present project has re-evaluated both Group XX and Charnwood petrology using those thin sections available to both Shotton and Bradley, along with additional thin sections from exposures held in collections at the Lapworth Museum and the British Geological Survey, as well as the artefact thin sections held by the South Western Implement Petrology Group (SWIPG).

Artefacts

Distribution

The geographical distribution of artefacts currently assigned to Group XX is shown in Figure 2 and details of each are listed in Supplementary S1. Although not a large petrological group when compared to others, its members are distributed over significant areas reaching north as far as Cumbria and as far south as Sussex. Its significance lies in its location situated midway between the widely utilised tuffs of Cumbria and the ubiquitous flint of southern and eastern England. Most artefacts are described as axeheads (114), thought on typological grounds to date to the Early Neolithic, however there are also adzes (2), maceheads (8), flakes (4), a perforated hammer, a pestle, a wedge, a pebble-mace, and a pebble-hammer, some of which might date slightly later. In terms of distribution, tools have mostly been found throughout the Midlands and East Anglia with significant concentrations in the Peak District and the fenland near Ely, alongside finds in Shropshire to the west and a notable group in Lincolnshire in the east. Few have been found within the confines of the Charnwood Forest itself, perhaps not surprisingly as most of the area is pasture or woodland and little has been cultivated. If tool finishing was carried out away from the site of extraction, finds might be expected in areas more conducive to settlement. Nevertheless, two were found near Spring Barrow Lodge (Implement Petrology Group (IPG) numbers Lei 020 and Lei 021) and another came from Poachers Corner, Charlie (IPG Lei 023) (below), all on the northern fringe of the Forest.

Most Group XX artefacts are stray finds, but a few good archaeological contexts are recorded. One axehead was found at Arbor Low henge in Derbyshire (IPG Dby 268) and two fragments (IPG Wil 025 and Wil 368) came from the upper fill of a ditch at the Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure in Wiltshire (Evens et al. Reference Evens, Smith and Wallis1972, 237; Smith Reference Smith, Clough and Cummins1979, 20). Elsewhere, artefacts have been found in later contexts, with a ‘medium polished axe’ recovered from the cairn over a burial cist (Shotton Reference Shotton1959, 141) at Bicton Circle in Shropshire. At Cross Platts Plantation in Derbyshire an axehead (IPG Dby 090) was excavated from an unknown context in a barrow (Moore and Cummins Reference Moore and Cummins1974; see Bateman Reference Bateman1868, 34–5; Howarth Reference Howarth1899, 14–5), and at Wigber Low in Derbyshire fragments (IPG Dby 255) were found in a Late Neolithic occupation layer beneath a barrow (Bradley Reference Bradley1989a, 183). At this latter site, the fragments were found with a Group VI axehead, a similar circumstance to the association at Saxby in Lincolnshire (Cummins & Moore Reference Cummins and Moore1973, 239; Bradley Reference Bradley1989a, 183).

Morphology

Based on a sample of 26 artefacts (Figure 3) representing approximately 20% of the artefacts assigned to Group XX, axeheads generally appear pale grey-brown in surface colour, randomly speckled, with a sandy, gritty surface texture. Variation in the colour of the surface patina may simply result from post-depositional processes. It is apparent that the group’s morphology is best described as stout and robust. As Mike Pitts (Reference Pitts1996, 342) noted in his digital analysis of axehead form, the type is quite distinctive and falls between his digitally generated forms 1, 4, and 5, but here two specific subgroups have been identified (Figure 4), confirming the observations of Timothy Clough and Barbara Green (Reference Clough and Green1972, 123, 138) who noted long and short examples in East Anglia. Table 1 summarises the morphology of all 26 Group XX artefacts examined (including perforated pieces) and shows the two main distinct morphological subgroups termed Subgroup A and Subgroup B, with labels C–F retained as minor placeholder groups for future work. It can be seen from the illustrations (Figures 3–4) that the difference is one of length, with Subgroup A being the longer of the two subgroups. While it is possible that this difference might represent two distinct phases of manufacture, or the changing preference of the end user, it may simply be that cleavage planes provided natural blanks of different length. Should an alternative suggestion that they represent different functions be accepted, the examination of wear traces may be fruitful. The distribution of these Group XX subgroups is distinguished in the distribution map (Figure 2), where it appears both Subgroups A and B have similar distribution patterns.

Of the two main subgroups, blades tend to be convex symmetrical (Subgroup A) or slightly asymmetrical (Subgroup B) and a wide, slightly curved and rounded to oval profiled butt is typical. Sides tend to be straight or very slightly curved, and in cross-section they appear oval/lenticular, with whole artefacts having maximum dimensions c. 125±30 mm long, 65±12 mm wide, and 33±12 mm thick. Occasionally, relict flake arrises are visible and it is evident that the chosen block was initially crudely knapped, then probably pecked, before being ground into shape. Most have lost any buffed surface, though it is expected that like many other ground Neolithic axeheads they will have been polished or at least finely ground. Partly damaged butts are not unusual and it may be that this resulted from fitting into a certain type of haft. A single example in Subgroup C is isolated here simply on account of it being slightly darker, but in all other respects it fits the Subgroup A and B template. Its patina is likely the result of post-depositional factors.

It is now apparent that several axeheads formerly listed as being in Group XX are unlikely to be from Charnwood. Several in Subgroup D are highlighted as not only different in colour but of different pXRF signature as well. Aside from colour, two of these, IPG Cub 014 and Cub 021 (Figure 3) stand out quite distinctly as having a more pointed butt. Having been found in Cumbria it is more likely that they derive from an unknown Cumbrian source and therefore are identified as such in Supplementary S1, but will be removed from Group XX subsequently. One other form in Subgroup D visually differs. This has pronounced side facets and is almost rectangular in cross-section (Figure 3, Lin 079). It immediately raises concern, as the form is similar to many Funnel Beaker culture (TRB) axeheads on the Continent (e.g. Wentink Reference Wentink2006; Walker Reference Walker2018), and as the pXRF data indicated that it has different large ion lithophile and high field strength elements values, it can now be discounted as a member of Group XX. Two similar examples from East Anglia formerly identified as Group XX (Clough & Green Reference Clough and Green1972, 123) therefore also become suspect, as does the adzehead from Whitmoor Common, Surrey (IPG Sur 069) (Field & Woolley Reference Field and Woolley1984, 901–2). Based on colour alone, the perforated implement in Subgroup F probably came from a different outcrop to the others.

Petrology

On a freshly fractured surface, the majority of artefacts macroscopically examined appear to have a pale grey, speckled colour. All are medium- to coarse-grained with fragmental texture and with many showing randomly scattered black specks. A few have noticeable banding picked out by grain size differences. Some pieces have larger, irregularly shaped, pale brown–cream coloured grains up to 5 mm. A x10 hand lens is needed to see sub-millimetre grey rounded to sub-rounded quartz grains, pale brown–cream coloured, irregular to tabular feldspar, very pale pink irregular rock fragments, and small irregular black grains (which may be epidote). The petrographic thin section from an axehead from Feltwell, Norfolk (IPG Nfk 120), is the pre-identified reference type for Group XX (it is recorded on the slide as such) and is the reference against which group membership is assessed here (Figure 5). It depicts a poorly sorted, immature medium- to coarse-grained volcaniclastic rock with occasional millimetre- to centimetre-sized banding (presumed to be fining upwards) and comprised of rock fragments, quartz grains, feldspar grains, and epidote with iron/titanium accessory minerals. Based on this microscopic petrology, the rock is an Epidotised Tuffaceous Sandstone or, alternatively, Epidotised Andesitic Tuff. The former name recognises the presence of reworked andesitic rock fragments, the second that much of the rock is associated with andesitic volcanism. A tuffaceous sandstone has 25–75% pyroclastic fragments, whereas a tuff has >75% pyroclastic fragments (Gillespie & Styles Reference Gillespie and Styles1999). The angular nature of the andesitic grains suggests these are not reworked volcaniclastic sediments, hence the latter description is favoured.

Geochemistry

Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (pXRF) is a simple to use, portable, and importantly non-destructive method that can be used to obtain geochemical data from archaeological artefacts. Alongside archaeological, geospatial, and petrological data, pXRF can help to locate the source of the rock used for manufacture. The method has previously proved useful in the identification of axeheads in Ireland, Shetland, and Cornwall (e.g. Meighan et al. Reference Meighan, Jamison, Logue, Mallory, Simpson, Mandal, Cooney and Logue1993; Mandal & Cooney Reference Mandal and Cooney1997; Markham Reference Markham2000; Reference Markham2018; Williams-Thorpe et al. Reference Williams-Thorpe, Webb and Jones2003). For the present study, a total of 26 of the 134 artefacts currently assigned to Group XX (Clough & Cummins Reference Clough, Cummins, Clough and Cummins1988) were analysed at four museums in Cambridge, Leicester, Lincoln, and Sheffield during October and November 2023. In each case the geochemical data were obtained using an Olympus VANTA M-Series (VMR, 50kV) pXRF spectrometer, utilising its ‘Geochem 3-Beam’ setting with each of the three beams lasting 60 seconds, 30 seconds, and 20 seconds respectively. Each artefact was measured at least four and normally six times, using the Vanta’s radiation-proof workstation within which the artefacts could be analysed safely. In each case the flattest and ‘cleanest’ location with a minimum thickness of 1 cm beneath the 8 mm pXRF aperture was measured and where possible readings were taken on either side. Analyses are summarised in Table 2, with bivariate diagrams for large ion lithophile and high field strength elements in Supplementaries S3 and S4.

The results for each artefact were averaged and the associated standard deviation calculated. As it is known that surface condition (weathering and texture), grain size, and morphology (curvature) of artefacts does affect the pXRF analyses (Markham Reference Markham2000), the artefact data were specifically explored using bivariate plots of large ion lithophile elements rubidium and strontium, and high field strength elements yttrium and zirconium. Examination of the bivariate plots as well as the data in general resulted in an indication that the geochemical analyses of the previously morphologically determined Subgroups A and B could be taken as typical for Group XX artefacts.

The summary of these two subgroups is presented in Table 2. Processing the Subgroup A and Subgroup B artefacts (93 values) and Windmill Hill figures (24 values) through a Student’s t-Test (performed in Excel), using a 2-tailed distribution and 2-sample unequal variance returned the following results: Rb 0.0340; Sr 0.0556; Y 0.6137; Zr 0.0804. Anything greater than 0.05 is deemed significant. The averages and standard deviation of the same datasets are, respectively Artefact – Windmill Hill: Rb 16.0±8.3 and 21.7±11.9; Sr 238.9±85.1 and 218.0±94.4; Y 18.6±4.1 and 19.2±5.3; Zr 50.8±13.8 and 61.3±27.2. All Windmill Hill averages are within ±1 standard deviation of the artefact Subgroup A and B averages.

All the pXRF analyses in this work were carried out using the same analyser and settings and thus are internally consistent. The pXRF ‘self-calibration check’ programme was run at the beginning and end of each session to give confidence in machine performance. Analyses can be compared with each other, and while confidence in the pXRF performance was obtained by reviewing measurements of a rock sample with known WDXRF provenance, the data in this work have not been calibrated to a known external reference. As such comparison with other published geochemical analyses must be carried out with care and forethought. Here, the pXRF has been used to augment the available archaeological, geospatial, and petrological information available in order to narrow down the search of the origin of Group XX material. We deliberately present the pXRF data values in ‘parts per million’ (ppm) as opposed to the normal geochemical practice of presenting the analyses as weight % for major oxides and ppm for minor elements, as while the data are internally consistent, they should not be taken as being definitive for Charnwood Forest as a whole.

Charnwood geology

The geology of the Charnwood Forest can be described as comprising Neoproterozoic Ediacaran rocks (635–541 mya) overlain by Mesozoic Triassic rocks (252–201 mya) with the older, much harder rocks seen as elevated jagged exposures (Figure 6). The Ediacaran rocks are geologically named as the Charnian Supergroup (Moseley Reference Moseley1979) and comprised of volcaniclastic sediments and associated with intermediate and acid volcanic suites, mostly andesites, dacites, and rhyolites. Within the Charnian Supergroup are three major formations: Blackbrook Formation, Beacon Hill Formation, and Bradgate Formation. Moreover, there are associated volcanic sequences of the Charnwood Lodge, Whitwick, and Bardon Hill Volcanic Sequence (Worssam & Old Reference Worssam and Old1988; Strange et al. Reference Strange, Carney and Ambrose2010). It is the Bradgate Formation which is of most interest here (Figure 7), characterised as ‘grey, fine-grained parallel-laminated, vitric tuffs’ to ‘thick graded sequences of tuffaceous sandstone fining upward to siltstone or mudstone cappings’ (Carney et al. Reference Carney, Ambrose and Brandon2002). Additionally, the British Geological SurveyFootnote 1 describes the lithology of this Formation as being comprised of thinly bedded and laminated mudstones and siltstones, locally tuffaceous; minor interbeds of vitric tuff and volcanic breccia; generally, the sequence fines upward.

Figure 6. Geospatial information for the source of petrographic thin sections examined in this work (T) and the location of outcrop pXRF measurements (O). Note that at this scale not all the thin section sources and measurement locations can be depicted (see S2 for details). Tan, white, red and pale pink: Triassic cover of the Charnwood Ediacaran rocks; dark purple: Charnwood Volcanics; light purple: Bradgate Formation; very pale purple: Beacon Hill Formation. The smaller yellow, pale blue and darker red areas are specific members of the Beacon Hill Formation. See https://geologyviewer.bgs.ac.uk/ for more details (map developed using QGIS v.3.40.4 ‘Bratislava’, plus British Geological Survey Open Source data: Solid Geology 1:50k Bedrock, ArcGIS Open Source ‘World Hillshade’ and Ordnance Survey Open Licence Mapping Data).

Figure 7. Typical exposure of the Bradgate Formation at Hangingstone Hills, illustrating the different thicknesses of bedding. Centimetre-sized bedding is seen at the top of the exposure with larger, metre-sized, bedding towards the bottom. The thicker bedding is thought likely to provide material suitable for artefact manufacture (photo: Shirley Markham).

Outcrop geology (Bradgate Formation)

Macroscopically, the Bradgate Formation exposures range between blocky, thickly (metre-sized) bedded (Figure 7) to thin, centimetre-sized bedding. The thinner beds can often be found with cleavage forming at an angle to the bedding, aligned to the axis of the Charnwood anticline. The exposures are grey to grey-brown in colour and from fine to very coarse in grain size, and are often lichen-covered. Many of the exposures have been quarried in recorded history or show signs of quarrying.

Over 36 petrological thin sections from a range of rock types found in the Charnwood Forest were examined, with the closest match to Group XX artefacts being from the Bradgate Formation, notably in the Hangingstone Hills area. In particular, two thin sections from the Windmill Hill area (British Geological Survey E 1838 and E 1895) are very similar to the majority of artefact thin sections, both in mineralogy and textures. The Windmill Hill rock is a poorly sorted volcaniclastic rock with millimetre-sized sub-rounded andesite fragments that contain plentiful and aligned feldspar laths and slightly more angular quartz grains with normal extinction (i.e. not wavy/stressed) and tiny opaque inclusions. Occasional mafic grains have been altered to chlorite/epidote and plentiful fine-grained epidote is seen in the finer matrix. Plentiful small, lath-like plagioclase feldspar grains (<0.5 mm) are randomly scattered throughout the thin sections, the larger ones containing alteration products (Figure 5b). The rock can be named as an Andesitic Lithic-crystal Tuff (or a Epidotised Tuffaceous Sandstone).

Outcrop geochemistry

Initial reconnaissance throughout the Charnwood area and examination of existing petrographic thin sections identified the Bradgate and Beacon Hill Formations as potential sources for Group XX axeheads. Following this, fieldwork began in October 2023, focussing on exposures of both formations: Bradgate Park, Charnwood Golf Course, Hangingstone Hill, Windmill Hill, and Beacon Hill (Figure 6). In addition, outcrops of other Charnwood Supergroup formation rocks in Cademan Woods, St. Bernards Abbey, Whitlock Quarry Edge, and Gun Hill were also analysed in order to assess the magnitude of geochemical variation. A minimum of two (though usually more) pXRF measurements were taken at each outcrop location using the same Vanta pXRF and settings as for the artefacts. In total 196 measurements were taken at 53 locations (all data are in Supplementary S3; locations illustrated in Figure 6). In addition, eight rock samples were obtained and sawn to provide a flat and unweathered fresh surface for pXRF analysis as an adjunct to the field measurements.

The data for each location were averaged and associated standard deviations calculated and then visually compared with the artefact data using bivariate plots of the large ion lithophile and high field strength elements rubidium, strontium, yttrium, and zirconium. It was assessed that the best, though not precise, match between artefact and rock outcrops is for the Windmill Hill exposure of the Bradgate Formation, where the four immobile large ion lithophile and high field strength element concentrations were within ±1 SD of those established for Group XX axeheads. There were observed differences between other elements measured, as was expected due to surface weathering, textures, and contamination. For example, sulphur was recorded from almost all field measurements and artefacts, but none was seen in sawn, fresh surfaced rock samples, suggesting the sulphur is a surface contaminant, possibly associated with acid rain. This latter point is speculation, and more work will be needed to be definitive. However, the near correlation of the four immobile large ion lithophile and high field strength element concentrations in both the exposure and Group XX artefacts indicates that Windmill Hill is a close match for Group XX. Outcrop pXRF data and associated bivariate plots used to examine the data are included in Supplementary S4.

Discussion

Re-examination of artefact and outcrop petrological thin sections from slide archives, along with refined data on the geology of Charnwood Forest, has allowed us to demonstrate close similarities between Group XX artefacts and the Bradgate Park Formation. In particular, a petrology slide of material from Windmill Hill provides a close, though not precise, match. In addition, and most importantly, pXRF analysis of both artefacts and outcrops has increased confidence and allowed an extraction area to be proposed on, or very close to, Windmill Hill, just west of Woodhouse Eaves. The hill itself has a prominent conical form and, as the name suggests, was topped by a post mill from 1863 (until it burned down in 1945) and was a local attraction that drew in tourists from across Leicestershire. Photographic evidence in Leicestershire Record Office (Figure 8) depicts public picnics and outings to the hilltop as common throughout the 1800s and early 1900s. It is clear, from the presence of weathered outcrops on and around the hill, that before then it was the site of intermittent small-scale quarrying for possibly millennia, with the most recent activity evidently taking place some considerable time before Enclosure.

Figure 8. Photograph of Windmill Hill, probably taken around the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth century. The exposure to the right of the image is the one examined in this work (i.e. Windmill Hill). The disturbed ground seen across the image suggests prior quarrying (Leicestershire Record Office DE3736 Box74: Photo Leicestershire Records Office).

Today, the hill sits in a mixed woodland of oak, ash, rowan, holly, and silver birch, crowned with bracken, brambles, and gorse. All that remains of the post mill is the stone base and there are extensive views to the south-west, north, and north-east, adequately satisfying Peter Topping’s (Reference Topping2021, 66–9) point that Neolithic extraction took place most often in dramatic, awe-inspiring locations. On a clear day, the site commands extensive views across the River Soar with Loughborough visible to the north and, more distantly, Lincoln to the north-east. Approximately 30 metres north from the actual windmill base lies an outcrop of the Bradgate Formation that provided pXRF large ion lithophile and high field strength element measurements closest to those of the artefacts (Figure 9). The exposure seems to have been quarried on its northern side, but historical archives indicate that no quarrying has been recorded within the last two centuries. Nevertheless, traces of small-scale quarrying, all weathered, rounded off, and evidently of some age can be traced around the hilltop. Neither is there any recorded Neolithic archaeology in the immediate area, though undoubtedly it would be interesting to examine the undulating and weathered ground disturbance downslope of the exposure to identify when quarrying took place.

Figure 9. The Bradgate Formation exposure on Windmill Hill that has the closest petrological and geochemical match with Group XX Subgroups A and B artefacts (photo: Jonathon Graham).

It has long been conjectured that the distribution of Group XX artefacts supports a Midlands source, though unfortunately the scarcity of roughouts has in the past not helped point to extraction or manufacturing sites. Aside from the three examples found within the Forest noted above, there are currently only four confirmed finds from the immediate environs: one from outside of Whitwick to the north-west of Woodhouse Eaves (IPG Lei 023), one to the north-east of Melton Mowbray (IPG Lei 014), and two axeheads from Rothley Lodge Farm (see Clay & Hunt Reference Clay and Hunt2016, 32–4), five miles south-east of Windmill Hill.

The aforementioned Group XX pieces from Rothley were found in pits containing occupation material of the early third millennium BC. However, in one case the Late Neolithic fill was part of a pit that recut an earlier feature, which had in turn cut into a pit to its north (see Clay & Hunt Reference Clay and Hunt2016, 22–4). The artefact from this feature was the butt of a Group XX axehead that had been ‘worked down as a core’ until it was interred with flint scrapers and the sherds of four Grooved Ware vessels. The other piece, which had also been flaked later in its life, was found in a pit containing some small stones, three flakes of flint, and a pebble that had been fire-cracked (Clay & Hunt Reference Clay and Hunt2016, 24–5; 33–4; 48–50). Given the reuse, coupled with a Late Neolithic radiocarbon date from the former context, it seems extremely unlikely that these axeheads were contemporaneous, but were probably disturbed from one of the earlier pits and reused. It remains possible, as Clay and Hunt (Reference Clay and Hunt2016, 33–4) suggested, that they were deliberately destroyed, as a Group VI axehead from nearby Rothley Temple Grange had been (Speed Reference Speed2015, 4, 13; see Larsson Reference Larsson, Davis and Edmonds2011 for deliberate destruction of axeheads).

In contrast to distributions in Leicestershire, the main clusters of Group XX implements have been found over 30 miles away to the north in Derbyshire, and Roy Loveday (Reference Loveday2004, 7) has argued that the axeheads may have travelled from Charnwood through the ‘Willington-Aston cursus zone’ of the Middle Trent Valley, where cursus monuments at Potlock and Aston flank the river (Figure 10) (see Gibson & Loveday Reference Gibson and Loveday1989; Guilbert & Malone Reference Guilbert and Malone1994). Across this zone, Loveday (Reference Loveday2004, 4–7) contends that many axeheads ended up in the south of the Peak District, where axeheads from Cornwall, Langdale, and Graig Lwyd can also be found in greater numbers. From there, axeheads such as those from Arbor Low and the fragments from Wigber Low may have been moved to nearby sites in the Dove–Derwent corridor (Loveday Reference Loveday2004, 7–8; see Clough & Cummins Reference Clough, Cummins, Clough and Cummins1988, 46). This distribution raises some interesting questions about the relationship of communities exploiting the outcrop at Windmill Hill during the Neolithic and contact with the surrounding regions.

Figure 10. Location of Potlock and Aston cursus monuments alongside the River Trent relative to Windmill Hill and axehead distribution (black spots) in the Peak District (after Gibson and Loveday Reference Gibson and Loveday1989, fig. 3; map developed using QGIS v.3.40.4 ‘Bratislava’, plus ArcGIS Open Source ‘World Hillshade’ and Ordnance Survey Open Licence Mapping Data).

One other rock source was exploited in the Midlands during prehistory, Group XIV, which was used for axe-hammers and located within the Nuneaton area. Again, extraction was minor; in this case just 28 examples are known, mostly found locally within the Nuneaton area. The material is Lamprophyre, originally thought to derive from Gryff, although recent fieldwork suggests that a source may lie on the prominent Mancetter Ridge (Supplementary S5). Windmill Hill, therefore, presents us with the unique opportunity to better understand how an axehead production site operated in the Midlands and how this potentially differs from the activities of those elsewhere. Whilst both petrology and pXRF data have assisted with pinpointing an extraction location for Group XX axeheads, further fieldwork is now needed to locate quarries and working floors. The well-weathered rounded undulations around the hill visible on the early photograph (Figure 8) provide obvious targets. Moreover, microwear analysis of Group XX axeheads could be a productive avenue in exploring whether there was a difference in how the two morphologies of axeheads were used in the past.

Conclusion

Re-examination of existing geological and petrological data, coupled with fresh geochemical data obtained using non-destructive pXRF, have confirmed that the source rock for Group XX is consistent with an origin in the Bradgate Formation, a major constituent of the Charnwood Super Group of rocks, which outcrops in Charnwood Forest. Significantly, analysis of both pXRF and petrological thin section data shows that the best data match between the majority of Group XX artefacts is with an exposure of the Bradgate Formation at Windmill Hill, just west of Woodhouse Eaves. The nature of the exposure, on high ground with excellent views from the north-east to the south, provides the typical topography well-known for Neolithic extraction. The location now requires more intense archaeological investigation to identify the actual manufacturing sites.

The result of this investigation now allows greater emphasis to be placed on Neolithic procurement methods and activities in the Midlands, an area generally seen as straddling the outreach of Cumbria and north Wales rocks on the one hand with flint-bearing regions on the other. It can provide the basis for beginning to understand the regional Neolithic and how it differs from, and indeed absorbs influences from, those areas to the north and south.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2025.10071.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Rachel Armitage at the University of Leicester for her tireless help with the pXRF throughout this project and the support, as well as comments on this report given by Professor Oliver Harris and Associate Professor Rachel Crellin. Thank you to Dr Annika Burns from the School of Geography, Geology and the Environment at the University of Leicester for assistance with rock samples. We would also like to thank Peter Liddle and Tom Clayton for facilitating access to Gun Hill, Helen Sharp at Leicestershire Museums, Eleanor Wilkinson at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge, Martha Jasko-Lawrence at Sheffield Museums, and Dawn Heywood at the Lincoln Museum & Usher Gallery for welcoming us and allowing recording of implements in their care. We also thank Louise Neep at the British Geological Survey for access to the Survey’s collection of petrological thin sections, Dr Peter Topping for his encouragement and insightful comments on this article, Dr Alison Sheridan, whose comprehensive knowledge of the subject is astounding and who provided endless avenues for fruitful enquiry, and last but not least Shirley Markham, who accompanied us and took photographs during much of the fieldwork.