1. Introduction

Flapping wings or tails are frequently employed in the locomotion of aerial and aquatic animals (Wang Reference Wang2005; Wu Reference Wu2011; Liu, Wang & Liu Reference Liu, Wang and Liu2024). On the one hand, this is because biological systems do not support rotor-like spinning machines. On the other hand, the flapping wing has more aerodynamic or hydrodynamic advantages at moderate Reynolds numbers, such as high lift, low noise and agility (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1969; Eldredge & Jones Reference Eldredge and Jones2019; Jaworski & Peake Reference Jaworski and Peake2020). Over billions of years of evolution, animals have adapted to various environments and developed highly efficient locomotion capabilities. Studying the dynamic and biological mechanisms underlying these abilities serves as a rich source of inspiration for bio-inspired design.

The rigid plate with prescribed pitching and heaving motion has been widely used in the modelling of the animal wing due to its simplicity and close relevance to most biological systems (Triantafyllou, Triantafyllou & Gopalkrishnan Reference Triantafyllou, Triantafyllou and Gopalkrishnan1991; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Streitlien, Barrett and Triantafyllou1998; Dong, Mittal & Najjar Reference Dong, Mittal and Najjar2006; Green, Rowley & Smits Reference Green, Rowley and Smits2011; Ayancik et al. Reference Ayancik, Zhong, Quinn, Brandes, Bart-Smith and Moored2019; Zhu, Mathai & Breuer Reference Zhu, Mathai and Breuer2021; Chao, Jia & Li Reference Chao, Jia and Li2024; Jin et al. Reference Jin, Wang, Ravi, Young, Lai and Tian2024). For instance, von Ellenrieder, Parker & Soria (Reference von Ellenrieder, Parker and Soria2003) visualised the three-dimensional flow structures behind a heaving and pitching finite-span wing and showed that variations in Strouhal number, pitch amplitude and phase angle can significantly alter the wake topology. Buchholz & Smits (Reference Buchholz and Smits2006) examined the wake of a low-aspect-ratio pitching panel and identified alternating horseshoe vortices whose streamwise legs dominate the wake dynamics at small aspect ratios. Later, Buchholz & Smits (Reference Buchholz and Smits2008) experimentally quantified the thrust generation of a finite-aspect-ratio panel pitching about its leading edge, showing that the thrust coefficient increases monotonically with the Strouhal number, aspect ratio and Reynolds number. In a related but distinct study, Quinn et al. (Reference Quinn, Moored, Dewey and Smits2014) investigated unsteady propulsion of a pitching foil near a solid boundary and demonstrated that ground effect can enhance thrust by up to

![]() $40\,\%$

at the equilibrium position where the time-averaged lift is zero. Regarding the development of a generic scaling analysis for flapping foils, Floryan et al. (Reference Floryan, Van Buren, Rowley and Smits2017) presented scaling relations for the thrust coefficient, power coefficient and propulsive efficiency of rigid foils undergoing either heaving or pitching motions, considering unsteady lift and added mass forces. They demonstrated that the mean thrust for heaving is entirely lift based, while for pitching, it is solely due to added mass. However, the mean input power and propulsive efficiency depend on contributions from both mechanisms. These scaling laws were validated through water tunnel experiments on a nominally two-dimensional flapping plate in a free stream, as well as by biological data of swimming aquatic animals. In a related study, Van Buren, Floryan & Smits (Reference Van Buren, Floryan and Smits2019) experimentally investigated rigid foils undergoing combined heaving and pitching motions in a free stream, considering the effect of phase difference. Their findings revealed that the pitching motion should lag the heaving motion by approximately

$40\,\%$

at the equilibrium position where the time-averaged lift is zero. Regarding the development of a generic scaling analysis for flapping foils, Floryan et al. (Reference Floryan, Van Buren, Rowley and Smits2017) presented scaling relations for the thrust coefficient, power coefficient and propulsive efficiency of rigid foils undergoing either heaving or pitching motions, considering unsteady lift and added mass forces. They demonstrated that the mean thrust for heaving is entirely lift based, while for pitching, it is solely due to added mass. However, the mean input power and propulsive efficiency depend on contributions from both mechanisms. These scaling laws were validated through water tunnel experiments on a nominally two-dimensional flapping plate in a free stream, as well as by biological data of swimming aquatic animals. In a related study, Van Buren, Floryan & Smits (Reference Van Buren, Floryan and Smits2019) experimentally investigated rigid foils undergoing combined heaving and pitching motions in a free stream, considering the effect of phase difference. Their findings revealed that the pitching motion should lag the heaving motion by approximately

![]() $30^\circ$

to maximise thrust and by approximately

$30^\circ$

to maximise thrust and by approximately

![]() $90^\circ$

to maximise the propulsive efficiency. Expanding on the scaling law developed by Floryan et al. (Reference Floryan, Van Buren, Rowley and Smits2017) for individual heaving or pitching motions, Van Buren et al. (Reference Van Buren, Floryan and Smits2019) developed new scaling laws for combined heaving and pitching motions, considering the phase offset between them, which were validated by experimental data.

$90^\circ$

to maximise the propulsive efficiency. Expanding on the scaling law developed by Floryan et al. (Reference Floryan, Van Buren, Rowley and Smits2017) for individual heaving or pitching motions, Van Buren et al. (Reference Van Buren, Floryan and Smits2019) developed new scaling laws for combined heaving and pitching motions, considering the phase offset between them, which were validated by experimental data.

Inspired by the role of flexibility in aerial locomotion, particularly in structures such as flying animals’ wings (Wootton Reference Wootton1992; Brodsky Reference Brodsky1994), researchers have studied passive or active deformation, in addition to passive flapping (Spagnolie et al. Reference Spagnolie, Moret, Shelley and Zhang2010; Zhang, Liu & Lu Reference Zhang, Liu and Lu2010), to gain deeper insights into how structural flexibility influences locomotor performance (Liao et al. Reference Liao, Beal, Lauder and Triantafyllou2003; Shyy et al. Reference Shyy, Aono, Chimakurthi, Trizila, Kang, Cesnik and Liu2010; Zhu, He & Zhang Reference Zhu, He and Zhang2014a , Reference Zhu, He and Zhangb ; Gazzola, Argentina & Mahadevan Reference Gazzola, Argentina and Mahadevan2015; Hoover et al. Reference Hoover, Cortez, Tytell and Fauci2018; Smits Reference Smits2019; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wang and Liu2024). Experimental studies conducted by Thiria & Godoy-Diana (Reference Thiria and Godoy-Diana2010) and Ramananarivo, Godoy-Diana & Thiria (Reference Ramananarivo, Godoy-Diana and Thiria2011) investigated the self-propulsion of flexible plates in the air. They found that flapping frequencies lower than the natural frequency of the flexible plate maximise the thrust coefficient and propulsive efficiency. Their experimental observations matched well with predictions from a nonlinear oscillator model, which incorporated cubic structural nonlinearities and both linear and quadratic damping terms. The modelling further revealed that non-resonant behaviour emerges both in the presence of nonlinear damping at small flapping amplitudes and due to geometric saturation effects at large amplitudes. Therefore, resonance mechanisms cannot explain the observed performance optimum. Instead, they found that at the optimal frequency ratio, the instantaneous angle of attack and the trailing-edge deflection angle become equal at the moment of maximum flapping velocity, a configuration that is more favourable for generating aerodynamic pressure contributing to thrust. Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Aono, Cesnik and Shyy2011) numerically investigated the flapping dynamics of flexible plates. They found that the maximum propulsive force is achieved slightly below resonance. In contrast, the optimal propulsive efficiency occurs when the flapping frequency is approximately half the natural frequency. A non-dimensional tip-deformation parameter was proposed to characterise the structural response, and both the time-averaged force and efficiency were shown to scale with this parameter. Alben et al. (Reference Alben, Witt, Baker, Anderson and Lauder2012) observed resonant-like peaks in the self-propulsive speed as the length and rigidity of the flexible plate were varied, both in numerical simulations and experiments. The inviscid model predicted that the self-propulsive speed scales with the length and rigidity, and these scalings were validated by experimental data. It has also been reported that the optimal propulsive efficiency can occur below (Ramananarivo et al. Reference Ramananarivo, Godoy-Diana and Thiria2011), at (Michelin & Llewellyn Smith Reference Michelin and Llewellyn Smith2009) or above the resonant frequency (Masoud & Alexeev Reference Masoud and Alexeev2010). All of these cases were observed in the experimental study (Dewey et al. Reference Dewey, Boschitsch, Moored, Stone and Smits2013) of flexible pitching panels in free-stream flow. Therefore, there is no consensus on whether resonance plays a definitive role in maximising thrust and propulsive efficiency.

It is important to note that the above-mentioned investigations into flexible plates treat those plates as inextensible. In comparison, compliant membranes possess finite in-plane stretching, allowing them to adapt to changing flow conditions through passive deformation and elastic extension (Swartz et al. Reference Swartz, Groves, Kim and Walsh1996; Shyy, Berg & Ljungqvist Reference Shyy, Berg and Ljungqvist1999; Song et al. Reference Song, Tian, Israeli, Galvao, Bishop, Swartz and Breuer2008; Cheney et al. Reference Cheney, Konow, Bearnot and Swartz2015; Mavroyiakoumou & Alben Reference Mavroyiakoumou and Alben2020, Reference Mavroyiakoumou and Alben2022; Mathai et al. Reference Mathai, Das, Naylor and Breuer2023). Unlike rigid or purely inextensible plates, membranes with finite in-plane stretching have been demonstrated to reduce flow separation and delay stall. The aerodynamic performance improvements of such membrane wings have been reviewed by Lian et al. (Reference Lian, Shyy, Viieru and Zhang2003) and Tiomkin & Raveh (Reference Tiomkin and Raveh2021). Tiomkin and colleagues (Tiomkin & Raveh Reference Tiomkin and Raveh2017, Reference Tiomkin and Raveh2019; Tiomkin & Jaworski Reference Tiomkin and Jaworski2022) developed theoretical models that couple thin-airfoil aerodynamics with membrane elasticity to describe the unsteady response and aeroelastic stability of membrane wings. In particular, Waldman & Breuer (Reference Waldman and Breuer2017) presented a model that incorporates the Young–Laplace equation to capture the nonlinear deformation of a membrane at low angles of attack and employs thin-airfoil theory to approximate the aerodynamic pressure acting on the membrane. The predicted camber, lift and vibrational frequency show good agreement with numerical simulations and experimental observations. Furthermore, Tzezana & Breuer (Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019) developed a theoretical framework that combines thin-airfoil theory with a membrane equation to model both steady and flapping membranes. As the flapping frequency increases, the membranes transition from thrust to drag near the resonant frequency, with this transition occurring earlier for more compliant membranes. Additionally, the wake experiences a transition from a reverse von Kármán vortex street to a traditional von Kármán vortex street. For highly compliant membranes, the wake transition frequency is predicted to be higher than the thrust–to-drag transition frequency. In the domain of numerical simulations and experiments, Lauber, Weymouth & Limbert (Reference Lauber, Weymouth and Limbert2023) employs a fully coupled fluid–structure interaction approach to investigate the effects of the Strouhal number and membrane compliance on the flight performance of bat-like flapping membrane wings, specifically designed to mimic the biomechanics of the handwing. They showed that a peak in both propulsive and lift efficiencies occurs near

![]() ${\textit{St}} \approx 0.5$

, which is significantly higher than the classical optimal Strouhal number range of

${\textit{St}} \approx 0.5$

, which is significantly higher than the classical optimal Strouhal number range of

![]() ${\textit{St}} \approx 0.2$

–

${\textit{St}} \approx 0.2$

–

![]() $0.4$

reported for the locomotion of birds and fishes (Triantafyllou, Triantafyllou & Grosenbaugh Reference Triantafyllou, Triantafyllou and Grosenbaugh1993; Taylor, Nudds & Thomas Reference Taylor, Nudds and Thomas2003). This shift is attributed to the specialised kinematics of bat flight. Moreover, they also found that, while reducing membrane stiffness improves propulsive efficiency, excessive compliance induces flutter and significantly degrades performance, and introducing anisotropy into the material model helps delay the onset of flutter.

$0.4$

reported for the locomotion of birds and fishes (Triantafyllou, Triantafyllou & Grosenbaugh Reference Triantafyllou, Triantafyllou and Grosenbaugh1993; Taylor, Nudds & Thomas Reference Taylor, Nudds and Thomas2003). This shift is attributed to the specialised kinematics of bat flight. Moreover, they also found that, while reducing membrane stiffness improves propulsive efficiency, excessive compliance induces flutter and significantly degrades performance, and introducing anisotropy into the material model helps delay the onset of flutter.

In contrast, the numerical study by Kumar, Seo & Mittal (Reference Kumar, Seo and Mittal2025) incorporates both the handwing and the armwing, enabling a more complete representation of bat wing kinematics. They employ a force partitioning method to analyse the aerodynamic forces and show that the dominant contribution arises from Q-induced forces, while the time-averaged contribution of kinematic forces is minimal. Here,

![]() $Q$

is the second invariant of the velocity gradient tensor. However, the time variation of the various partitions of the pressure-induced lift and drag forces reveals that the primary source of force oscillations is the kinematic component. This insight highlights the important role of unsteady inertial effects, particularly those associated with wing flutter. Similarly, Gehrke & Mulleners (Reference Gehrke and Mulleners2025) experimentally investigated the effects of the in-plane stretching stiffness and pitching amplitude on the lift and efficiency of a flapping membrane in a stationary fluid. In their set-up, the membrane undergoes a prescribed horizontal heaving motion while maintaining a constant pitching angle throughout the flapping cycle. They identified distinct optimal values for the in-plane stretching stiffness and angle of attack, which maximise lift and efficiency, respectively. They observed different vortex patterns, and, unlike the rigid plate, it is no longer the leading-edge vortex that generates lift. Instead, the curvature of the membrane suppresses the leading-edge vortex. Vorticity then accumulates in a bound shear layer that covers the entire membrane, thereby enhancing lift.

$Q$

is the second invariant of the velocity gradient tensor. However, the time variation of the various partitions of the pressure-induced lift and drag forces reveals that the primary source of force oscillations is the kinematic component. This insight highlights the important role of unsteady inertial effects, particularly those associated with wing flutter. Similarly, Gehrke & Mulleners (Reference Gehrke and Mulleners2025) experimentally investigated the effects of the in-plane stretching stiffness and pitching amplitude on the lift and efficiency of a flapping membrane in a stationary fluid. In their set-up, the membrane undergoes a prescribed horizontal heaving motion while maintaining a constant pitching angle throughout the flapping cycle. They identified distinct optimal values for the in-plane stretching stiffness and angle of attack, which maximise lift and efficiency, respectively. They observed different vortex patterns, and, unlike the rigid plate, it is no longer the leading-edge vortex that generates lift. Instead, the curvature of the membrane suppresses the leading-edge vortex. Vorticity then accumulates in a bound shear layer that covers the entire membrane, thereby enhancing lift.

Beyond bio-inspired studies of flapping flight, compliant membranes have also been investigated for their potential in flow energy harvesting. For example, Mathai et al. (Reference Mathai, Tzezana, Das and Breuer2022) experimentally studied a flexible membrane oscillating in a uniform flow and demonstrated that it could extract up to

![]() $160\,\%$

more power than a rigid plate. This enhancement was attributed to the increased lateral force resulting from the delayed shedding of the leading-edge vortex. Similarly, Upfal et al. (Reference Upfal, Zhu, Handy-Cardenas and Breuer2025) investigated a shape-morphing membrane foil in an energy-harvesting configuration and found that, at moderately high effective angles of attack, membrane compliance stabilises the leading-edge vortex and delays dynamic stall, enhancing efficiency, whereas excessive deformation at very high angles leads to performance degradation. In a related study, Gehrke et al. (Reference Gehrke, Richeux, Uksul and Mulleners2022) examined a bio-inspired flapping membrane wing in a hovering configuration and showed that its aerodynamic performance increases with effective angle of attack up to an intermediate-to-high range, beyond which excessive angles lead to stronger flow separation and a reduction in lift. In the present work, however, we restrict our analysis to moderate-to-low effective angles of attack (approximately

$160\,\%$

more power than a rigid plate. This enhancement was attributed to the increased lateral force resulting from the delayed shedding of the leading-edge vortex. Similarly, Upfal et al. (Reference Upfal, Zhu, Handy-Cardenas and Breuer2025) investigated a shape-morphing membrane foil in an energy-harvesting configuration and found that, at moderately high effective angles of attack, membrane compliance stabilises the leading-edge vortex and delays dynamic stall, enhancing efficiency, whereas excessive deformation at very high angles leads to performance degradation. In a related study, Gehrke et al. (Reference Gehrke, Richeux, Uksul and Mulleners2022) examined a bio-inspired flapping membrane wing in a hovering configuration and showed that its aerodynamic performance increases with effective angle of attack up to an intermediate-to-high range, beyond which excessive angles lead to stronger flow separation and a reduction in lift. In the present work, however, we restrict our analysis to moderate-to-low effective angles of attack (approximately

![]() $10^\circ$

–

$10^\circ$

–

![]() $40^\circ$

), focusing on the propulsive regime rather than the high-angle flow-separation dynamics.

$40^\circ$

), focusing on the propulsive regime rather than the high-angle flow-separation dynamics.

Despite the existing theoretical, numerical and experimental works on membranes with finite in-plane stretching, fundamental physical questions remain unanswered: How does the membrane’s stretching stiffness at different levels alter the strength of vortex structures formed on the membrane and impact its dynamic performance? And how can we capture this coupled fluid–structure dynamics in a unified scaling framework that predicts thrust and power? To address these questions, we perform fully coupled fluid–structure interaction simulations of a two-dimensional membrane undergoing simultaneous heaving and pitching in a uniform flow, while systematically varying the membrane’s stretching stiffness, Strouhal number and pitching amplitude. By analysing the evolution of vortices and membrane dynamics, we uncover the physical mechanisms through which propulsion performance is enhanced and modify scaling laws that capture the dominant contributions to thrust and power, with good agreement across a wide range of parameters.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. The physical problem and mathematical formulation are presented in § 2.1. The numerical method is described in § 2.2. Detailed results are discussed in § 3, and concluding remarks are addressed in § 4.

2. Computational model

2.1. Physical problem and mathematical formulation

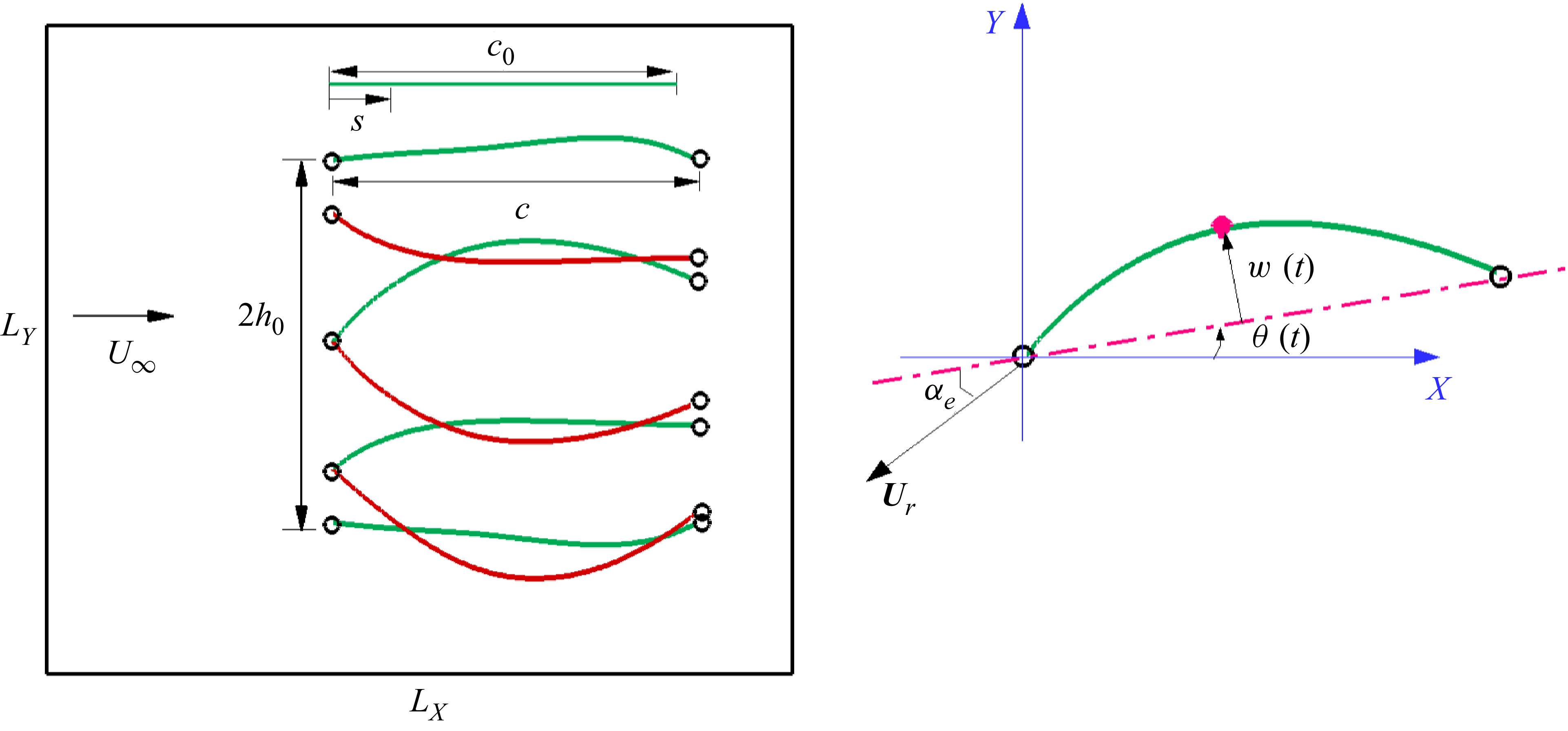

A two-dimensional model of a membrane with finite in-plane stretching flapping in uniform flow is considered. As shown in figure 1, a compliant membrane with an original length

![]() $c_0$

in the flat and stress-free state is pre-stretched to a length

$c_0$

in the flat and stress-free state is pre-stretched to a length

![]() $c$

and immersed in a viscous fluid. The computational domain is an

$c$

and immersed in a viscous fluid. The computational domain is an

![]() $L_X\times L_Y$

rectangle, where

$L_X\times L_Y$

rectangle, where

![]() $L_X$

and

$L_X$

and

![]() $L_Y$

are the domain sizes in the

$L_Y$

are the domain sizes in the

![]() $x\hbox{-}$

and

$x\hbox{-}$

and

![]() $y\hbox{-}$

directions, respectively.

$y\hbox{-}$

directions, respectively.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of a membrane flapping in a uniform incoming flow. Here,

![]() $2 h_0$

denotes the peak-to-peak heaving displacement, and

$2 h_0$

denotes the peak-to-peak heaving displacement, and

![]() $\theta (t)$

represents the instantaneous pitching angle.

$\theta (t)$

represents the instantaneous pitching angle.

To investigate this system of fluid–membrane interaction, the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations are solved to simulate the flow

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

is the velocity,

$\boldsymbol{v}$

is the velocity,

![]() $p$

the pressure,

$p$

the pressure,

![]() $\rho$

the density of the fluid,

$\rho$

the density of the fluid,

![]() $\mu$

the dynamic viscosity and

$\mu$

the dynamic viscosity and

![]() $\boldsymbol{f}_{\kern-1.5pt b}$

the body force term.

$\boldsymbol{f}_{\kern-1.5pt b}$

the body force term.

As shown in figure 1, the leading edge of the membrane undergoes a heaving motion, while the trailing edge experiences a combination of heaving and pitching motions about the leading edge. The green curves represent the membrane during the downstroke, whereas the red curves represent the membrane during the upstroke. The heaving and pitching motions are respectively described by the following equations:

Here, the phase difference between the heaving and pitching motions is set to

![]() $\phi =-90^\circ$

, meaning that the pitching motion lags the heaving motion by one quarter of a cycle. This phasing has been shown to maximise propulsive efficiency in previous studies (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1970; Wu Reference Wu1971; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Streitlien, Barrett and Triantafyllou1998; Quinn, Lauder & Smits Reference Quinn, Lauder and Smits2015). In figure 1,

$\phi =-90^\circ$

, meaning that the pitching motion lags the heaving motion by one quarter of a cycle. This phasing has been shown to maximise propulsive efficiency in previous studies (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1970; Wu Reference Wu1971; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Streitlien, Barrett and Triantafyllou1998; Quinn, Lauder & Smits Reference Quinn, Lauder and Smits2015). In figure 1,

![]() $w(t)$

is the instantaneous maximal deflection relative to the undeformed state, with positive values representing upward deflections and negative values representing downward deflections and

$w(t)$

is the instantaneous maximal deflection relative to the undeformed state, with positive values representing upward deflections and negative values representing downward deflections and

![]() $\alpha _{e}$

is the effective angle of attack, defined as

$\alpha _{e}$

is the effective angle of attack, defined as

where

![]() $U_\infty$

denotes the incoming flow velocity. The deformation and motion of the membrane are described by the structural equation (Connell & Yue Reference Connell and Yue2007; Hua, Zhu & Lu Reference Hua, Zhu and Lu2013)

$U_\infty$

denotes the incoming flow velocity. The deformation and motion of the membrane are described by the structural equation (Connell & Yue Reference Connell and Yue2007; Hua, Zhu & Lu Reference Hua, Zhu and Lu2013)

where

![]() $s$

is the Lagrangian coordinate along the membrane in its flat, stress-free state, with

$s$

is the Lagrangian coordinate along the membrane in its flat, stress-free state, with

![]() $s\in [0,c_0]$

,

$s\in [0,c_0]$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}(s,t)$

is the Eulerian position vector for a Lagrangian point

$\boldsymbol{X}(s,t)$

is the Eulerian position vector for a Lagrangian point

![]() $s$

at time

$s$

at time

![]() $t$

,

$t$

,

![]() $\rho _s$

is the membrane line density (mass per unit length) and

$\rho _s$

is the membrane line density (mass per unit length) and

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt s}$

is the Lagrangian force exerted on the membrane by the surrounding fluid. The parameters

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt s}$

is the Lagrangian force exerted on the membrane by the surrounding fluid. The parameters

![]() $Eh$

and

$Eh$

and

![]() $EI$

represent the dimensional stretching and the bending stiffnesses, respectively. A pre-stretch is introduced through the following boundary conditions:

$EI$

represent the dimensional stretching and the bending stiffnesses, respectively. A pre-stretch is introduced through the following boundary conditions:

Here,

![]() $c$

is the length after pre-stretching, with a pre-stretch ratio of

$c$

is the length after pre-stretching, with a pre-stretch ratio of

![]() $\lambda _0=c/c_0$

. Both ends of the membrane are hinged (simply supported) and subjected to prescribed motions: the leading edge performs pure heaving motion, while the trailing edge performs combined heaving and pitching motions. The hinged condition implies zero bending moment at both ends, expressed as

$\lambda _0=c/c_0$

. Both ends of the membrane are hinged (simply supported) and subjected to prescribed motions: the leading edge performs pure heaving motion, while the trailing edge performs combined heaving and pitching motions. The hinged condition implies zero bending moment at both ends, expressed as

The above equations are non-dimensionalised by the following characteristic scales: the chord length

![]() $c$

, the fluid density

$c$

, the fluid density

![]() $\rho$

and the incoming flow velocity

$\rho$

and the incoming flow velocity

![]() $U_\infty$

. The dimensionless governing parameters are listed as follows: the Reynolds number

$U_\infty$

. The dimensionless governing parameters are listed as follows: the Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=\rho U_\infty c/\mu$

, the in-plane stretching stiffness

${\textit{Re}}=\rho U_\infty c/\mu$

, the in-plane stretching stiffness

![]() $K_{\!S}=Eh/\rho U_\infty ^{2}c$

(also referred to as the aeroelastic number (Tzezana & Breuer Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019)), the bending stiffness

$K_{\!S}=Eh/\rho U_\infty ^{2}c$

(also referred to as the aeroelastic number (Tzezana & Breuer Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019)), the bending stiffness

![]() $K_{\kern-1pt B}=EI/\rho U_\infty ^{2} {c}^{3}$

, the mass ratio

$K_{\kern-1pt B}=EI/\rho U_\infty ^{2} {c}^{3}$

, the mass ratio

![]() $M=\rho _s/\rho c$

and the Strouhal number

$M=\rho _s/\rho c$

and the Strouhal number

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c=fc/U_\infty$

. Moreover, the instantaneous thrust coefficient (

${\textit{St}}_c=fc/U_\infty$

. Moreover, the instantaneous thrust coefficient (

![]() $\widetilde {C_T}$

), time-averaged thrust coefficient (

$\widetilde {C_T}$

), time-averaged thrust coefficient (

![]() $C_T$

), time-averaged power coefficient (

$C_T$

), time-averaged power coefficient (

![]() $C_{\!P}$

) and propulsive efficiency (

$C_{\!P}$

) and propulsive efficiency (

![]() $\eta$

) (Van Buren et al. Reference Van Buren, Floryan and Smits2019) are defined as

$\eta$

) (Van Buren et al. Reference Van Buren, Floryan and Smits2019) are defined as

\begin{align} \widetilde {C_T}&=\frac {-\int _0^c F_x(s,t) \, {\rm d}s}{\frac {1}{2}\rho U_{\infty }^2 c},\; C_T=\frac {1}{T_f}\int _t^{t+T_f}\widetilde {C_T} \, {\rm d}t, \nonumber\\ C_{\!P}&=\frac {1}{T_f}\frac {-\int _t^{t+T_f}\int _0^c \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt s}(s,t)\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _t \boldsymbol{X} \, {\rm d}s \,{\rm d}t}{\frac {1}{2}\rho U_{\infty }^3 c},\; \eta =\frac {C_T}{C_{\!P}} .\end{align}

\begin{align} \widetilde {C_T}&=\frac {-\int _0^c F_x(s,t) \, {\rm d}s}{\frac {1}{2}\rho U_{\infty }^2 c},\; C_T=\frac {1}{T_f}\int _t^{t+T_f}\widetilde {C_T} \, {\rm d}t, \nonumber\\ C_{\!P}&=\frac {1}{T_f}\frac {-\int _t^{t+T_f}\int _0^c \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt s}(s,t)\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _t \boldsymbol{X} \, {\rm d}s \,{\rm d}t}{\frac {1}{2}\rho U_{\infty }^3 c},\; \eta =\frac {C_T}{C_{\!P}} .\end{align}

Here, the minus sign in

![]() $\widetilde {C_T}$

reflects that the free-stream velocity is aligned with the positive

$\widetilde {C_T}$

reflects that the free-stream velocity is aligned with the positive

![]() $x$

-direction, so a positive thrust acting against the free stream corresponds to a force in the negative

$x$

-direction, so a positive thrust acting against the free stream corresponds to a force in the negative

![]() $x$

-direction. Meanwhile, the minus sign in

$x$

-direction. Meanwhile, the minus sign in

![]() $C_{\!P}$

reflects the convention that the power is positive when the membrane does work on the fluid, which corresponds to negative work exerted by the fluid on the membrane.

$C_{\!P}$

reflects the convention that the power is positive when the membrane does work on the fluid, which corresponds to negative work exerted by the fluid on the membrane.

2.2. Numerical method and validation

The lattice Boltzmann method (Chen & Doolen Reference Chen and Doolen1998) is employed to solve the governing equations of fluid flow. The corresponding lattice Boltzmann equation with a body force model (Guo, Zheng & Shi Reference Guo, Zheng and Shi2002) is given by

where

![]() $g_i(\boldsymbol{x}, t)$

is the distribution function for particles with velocity

$g_i(\boldsymbol{x}, t)$

is the distribution function for particles with velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{e}_i$

at position

$\boldsymbol{e}_i$

at position

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

and time t,

$\boldsymbol{x}$

and time t,

![]() $\tau$

is the non-dimensional relaxation time and

$\tau$

is the non-dimensional relaxation time and

![]() $\delta t$

is the time increment. The equilibrium distribution function

$\delta t$

is the time increment. The equilibrium distribution function

![]() $g_i^{\textit{eq}}$

and the force term

$g_i^{\textit{eq}}$

and the force term

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt i}$

(Chen & Doolen Reference Chen and Doolen1998; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Zheng and Shi2002) are defined as

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt i}$

(Chen & Doolen Reference Chen and Doolen1998; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Zheng and Shi2002) are defined as

\begin{align} g_i^{\textit{eq}}&= w_i \rho \left[1+\frac { \boldsymbol{e}_i \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v} }{ c_s^2 } + \frac {\boldsymbol{v}\boldsymbol{v}:\left(\boldsymbol{e}_i \boldsymbol{e}_i - c_s^2\boldsymbol{I}\right)}{2c_s^2}\right]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} g_i^{\textit{eq}}&= w_i \rho \left[1+\frac { \boldsymbol{e}_i \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v} }{ c_s^2 } + \frac {\boldsymbol{v}\boldsymbol{v}:\left(\boldsymbol{e}_i \boldsymbol{e}_i - c_s^2\boldsymbol{I}\right)}{2c_s^2}\right]\!, \end{align}

where

![]() $w_i$

is the weighting factor and

$w_i$

is the weighting factor and

![]() $c_s$

is the lattice sound speed.

$c_s$

is the lattice sound speed.

The standard lattice Boltzmann method is based on a regular square lattice, where a set of discrete velocity vectors

![]() $\boldsymbol{e}_i$

$\boldsymbol{e}_i$

![]() $(i=1{-}N)$

pointing to the neighbouring nodes is defined at each lattice point to represent the molecular velocities. The two-dimensional nine-velocity lattice model is applied here. In this model,

$(i=1{-}N)$

pointing to the neighbouring nodes is defined at each lattice point to represent the molecular velocities. The two-dimensional nine-velocity lattice model is applied here. In this model,

![]() $i=1$

corresponds to the rest particle,

$i=1$

corresponds to the rest particle,

![]() $i=2{-}5$

denote the axis-aligned velocities and

$i=2{-}5$

denote the axis-aligned velocities and

![]() $i=6{-}9$

denote the diagonal velocities. The discrete velocity vectors and their corresponding weighting factors are given as follows:

$i=6{-}9$

denote the diagonal velocities. The discrete velocity vectors and their corresponding weighting factors are given as follows:

The density

![]() $\rho$

and velocity

$\rho$

and velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

can be calculated by the distribution functions

$\boldsymbol{v}$

can be calculated by the distribution functions

The structure (2.5) is solved by the finite element method (FEM) with the co-rotational scheme (Doyle Reference Doyle2013). The immersed boundary method couples the fluid–structure interaction (Peskin Reference Peskin2002). The Lagrangian force exerted on the membrane by the fluid

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt s}=(F_x,F_y)$

in (2.5) is calculated using the penalty scheme (Goldstein, Handler & Sirovich Reference Goldstein, Handler and Sirovich1993)

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt s}=(F_x,F_y)$

in (2.5) is calculated using the penalty scheme (Goldstein, Handler & Sirovich Reference Goldstein, Handler and Sirovich1993)

where

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $\beta$

are penalty parameters, and the corresponding values are selected based on the previous studies (Hua, Zhu & Lu Reference Hua, Zhu and Lu2014; Peng, Huang & Lu Reference Peng, Huang and Lu2018; Zhang, Huang & Lu Reference Zhang, Huang and Lu2020),

$\beta$

are penalty parameters, and the corresponding values are selected based on the previous studies (Hua, Zhu & Lu Reference Hua, Zhu and Lu2014; Peng, Huang & Lu Reference Peng, Huang and Lu2018; Zhang, Huang & Lu Reference Zhang, Huang and Lu2020),

![]() $\boldsymbol{V}_{\kern-1pt s}= {\partial \boldsymbol{X}}/{\partial t}$

is the velocity of the Lagrangian point of the membrane and

$\boldsymbol{V}_{\kern-1pt s}= {\partial \boldsymbol{X}}/{\partial t}$

is the velocity of the Lagrangian point of the membrane and

![]() $\boldsymbol{V}_{\kern-1pt f}$

is the fluid velocity at the position

$\boldsymbol{V}_{\kern-1pt f}$

is the fluid velocity at the position

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}$

obtained by interpolation

$\boldsymbol{X}$

obtained by interpolation

where

![]() $\delta (\boldsymbol{x}{-}\boldsymbol{X})$

is the smoothed Dirac delta function. The body force term

$\delta (\boldsymbol{x}{-}\boldsymbol{X})$

is the smoothed Dirac delta function. The body force term

![]() $\boldsymbol{f}_{\kern-1.5pt b}$

in (2.1) is used as an interaction force between the fluid and the immersed boundary to enforce the no-slip velocity boundary condition. The body force

$\boldsymbol{f}_{\kern-1.5pt b}$

in (2.1) is used as an interaction force between the fluid and the immersed boundary to enforce the no-slip velocity boundary condition. The body force

![]() $\boldsymbol{f}_{\kern-1.5pt b}$

on the Eulerian points can be obtained from the Lagrangian force

$\boldsymbol{f}_{\kern-1.5pt b}$

on the Eulerian points can be obtained from the Lagrangian force

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_s$

using the Dirac delta function, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{F}_s$

using the Dirac delta function, i.e.

Figure 2. Time variations of

![]() $\widetilde {C_T}$

for cases with

$\widetilde {C_T}$

for cases with

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=200$

,

${\textit{Re}}=200$

,

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c=0.25$

,

${\textit{St}}_c=0.25$

,

![]() $K_{\!S}=10$

,

$K_{\!S}=10$

,

![]() $\theta _0=15^\circ$

and

$\theta _0=15^\circ$

and

![]() $M=1.0$

, simulated under (

$M=1.0$

, simulated under (

![]() $a$

) three different combinations of grid spacings and time steps, and (

$a$

) three different combinations of grid spacings and time steps, and (

![]() $b$

) two discrete mesh sizes for the membrane. (

$b$

) two discrete mesh sizes for the membrane. (

![]() $c$

) Time evolution of the dimensionless transverse displacement

$c$

) Time evolution of the dimensionless transverse displacement

![]() $y_m$

of the midpoint of a membrane with fixed simply supported boundaries at both ends, undergoing free vibrations triggered by small perturbations for three different values of

$y_m$

of the midpoint of a membrane with fixed simply supported boundaries at both ends, undergoing free vibrations triggered by small perturbations for three different values of

![]() $K_{\!S}$

. (

$K_{\!S}$

. (

![]() $d$

) Power spectral density (PSD) of

$d$

) Power spectral density (PSD) of

![]() $y_m$

corresponding to the three

$y_m$

corresponding to the three

![]() $K_{\!S}$

cases shown in (

$K_{\!S}$

cases shown in (

![]() $c$

), and the dotted lines indicate the analytical values of the first-order natural frequencies for each case.

$c$

), and the dotted lines indicate the analytical values of the first-order natural frequencies for each case.

A uniform velocity

![]() $U_\infty$

is applied at the inlet boundary and the two side boundaries of the fluid computational domain. A Neumann boundary condition (

$U_\infty$

is applied at the inlet boundary and the two side boundaries of the fluid computational domain. A Neumann boundary condition (

![]() $\partial \boldsymbol{U}/\partial x=0$

) is specified at the outlet boundary. The computational domain for fluid flow is chosen to be

$\partial \boldsymbol{U}/\partial x=0$

) is specified at the outlet boundary. The computational domain for fluid flow is chosen to be

![]() $40c\times 20c$

in the

$40c\times 20c$

in the

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

- directions to eliminate boundary effects. A convergence study for grid spacing and time step is conducted for cases with

$y$

- directions to eliminate boundary effects. A convergence study for grid spacing and time step is conducted for cases with

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=200$

,

${\textit{Re}}=200$

,

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c=0.2$

,

${\textit{St}}_c=0.2$

,

![]() $K_{\!S}=30$

,

$K_{\!S}=30$

,

![]() $\theta _0=15^\circ$

and

$\theta _0=15^\circ$

and

![]() $M=1.0$

. Figure 2(a) shows the time-dependent thrust coefficient

$M=1.0$

. Figure 2(a) shows the time-dependent thrust coefficient

![]() $\widetilde {C_T}$

under three different grid spacings

$\widetilde {C_T}$

under three different grid spacings

![]() $\Delta x$

and time steps

$\Delta x$

and time steps

![]() $\Delta t$

. It can be seen that

$\Delta t$

. It can be seen that

![]() $\Delta x=c/100$

and

$\Delta x=c/100$

and

![]() $\Delta t=T/10\,000$

are sufficiently small to yield accurate results, where

$\Delta t=T/10\,000$

are sufficiently small to yield accurate results, where

![]() $T$

is the flapping period. Therefore,

$T$

is the flapping period. Therefore,

![]() $\Delta x=c/100$

and

$\Delta x=c/100$

and

![]() $\Delta t=T/10\,000$

are adopted for all the present simulations. Since the membrane in this study can undergo in-plane stretching deformation, two different structure grid spacings,

$\Delta t=T/10\,000$

are adopted for all the present simulations. Since the membrane in this study can undergo in-plane stretching deformation, two different structure grid spacings,

![]() $\Delta s$

, are tested. Figure 2(b) presents the time-dependent thrust coefficient for a grid with the same size as the fluid grid,

$\Delta s$

, are tested. Figure 2(b) presents the time-dependent thrust coefficient for a grid with the same size as the fluid grid,

![]() $\Delta s=c/100$

, and a finer grid,

$\Delta s=c/100$

, and a finer grid,

![]() $\Delta s=c/200$

, used to discretise the solid structure. Although the different values of

$\Delta s=c/200$

, used to discretise the solid structure. Although the different values of

![]() $\Delta s$

do not produce any changes, a finer solid grid with

$\Delta s$

do not produce any changes, a finer solid grid with

![]() $\Delta s=c/200$

is used to better capture the membrane deformation.

$\Delta s=c/200$

is used to better capture the membrane deformation.

The numerical strategy used here has been successfully applied to flexible plates without pre-stretching in a wide range of flows (Hua et al. Reference Hua, Zhu and Lu2014; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Huang and Lu2018; Liu, Liu & Huang Reference Liu, Liu and Huang2022; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Sun, Yang, Xiong, Wang and Wang2022; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Gao, Lu and Chen2024). Figures 2(

![]() $c$

) and 2(

$c$

) and 2(

![]() $d$

) validate the FEM solver for simulating the free vibrations of a membrane with

$d$

) validate the FEM solver for simulating the free vibrations of a membrane with

![]() $M=1.0$

,

$M=1.0$

,

![]() $K_{\kern-1pt B}=10^{-4}$

and a pre-stretch ratio of

$K_{\kern-1pt B}=10^{-4}$

and a pre-stretch ratio of

![]() $\lambda _0=1.05$

in a vacuum. The membrane is subject to small perturbations and has fixed simply supported boundary conditions at both ends. The validation is performed by comparing the simulation results with the analytical solution for the natural frequency. Figure 2(

$\lambda _0=1.05$

in a vacuum. The membrane is subject to small perturbations and has fixed simply supported boundary conditions at both ends. The validation is performed by comparing the simulation results with the analytical solution for the natural frequency. Figure 2(

![]() $c$

) presents the time-dependent transverse displacement (

$c$

) presents the time-dependent transverse displacement (

![]() $y_m$

) of the membrane’s midpoint for

$y_m$

) of the membrane’s midpoint for

![]() $K_{\!S} = 5$

,

$K_{\!S} = 5$

,

![]() $K_{\!S} = 39.2$

, and

$K_{\!S} = 39.2$

, and

![]() $K_{\!S} = 51.2$

. The PSD analysis of

$K_{\!S} = 51.2$

. The PSD analysis of

![]() $y_m$

, shown in figure 2(d), reveals that the dimensionless dominant frequencies (

$y_m$

, shown in figure 2(d), reveals that the dimensionless dominant frequencies (

![]() $f$

) are

$f$

) are

![]() $0.250$

,

$0.250$

,

![]() $0.700$

and

$0.700$

and

![]() $0.800$

for

$0.800$

for

![]() $K_{\!S} = 5$

,

$K_{\!S} = 5$

,

![]() $K_{\!S} = 39.2$

and

$K_{\!S} = 39.2$

and

![]() $K_{\!S} = 51.2$

, respectively.

$K_{\!S} = 51.2$

, respectively.

Under the small-deflection assumption, the dimensionless governing equation for the transverse free vibration of a pre-stretched membrane in vacuum is written as

where

![]() $y(x,t)$

denotes the transverse displacement. Assuming a harmonic solution of the form

$y(x,t)$

denotes the transverse displacement. Assuming a harmonic solution of the form

![]() $y(x,t) = \phi (x)\,e^{i\omega t}$

and substituting it into the governing equation yields the following ordinary differential equation for the mode shape

$y(x,t) = \phi (x)\,e^{i\omega t}$

and substituting it into the governing equation yields the following ordinary differential equation for the mode shape

![]() $\phi (x)$

:

$\phi (x)$

:

where

![]() $\omega$

is the angular frequency of vibration. The general solution of (2.21) is

$\omega$

is the angular frequency of vibration. The general solution of (2.21) is

![]() $\phi (x) = C_0 \sin (\gamma x) + C_1 \cos (\gamma x)$

, where

$\phi (x) = C_0 \sin (\gamma x) + C_1 \cos (\gamma x)$

, where

![]() $\gamma =\sqrt {({(M/\lambda _0) }/{K_{\!S}(\lambda _0-1)})}\,\omega$

. Applying the hinged boundary conditions at both ends of the membrane

$\gamma =\sqrt {({(M/\lambda _0) }/{K_{\!S}(\lambda _0-1)})}\,\omega$

. Applying the hinged boundary conditions at both ends of the membrane

gives

![]() $C_1=0$

and

$C_1=0$

and

![]() $\gamma =n\pi$

(

$\gamma =n\pi$

(

![]() $n=1,2,\ldots$

). Therefore, the analytical expression for the dimensionless

$n=1,2,\ldots$

). Therefore, the analytical expression for the dimensionless

![]() $n$

th natural frequency is given by

$n$

th natural frequency is given by

\begin{eqnarray} f_n = \frac {\omega _n}{2\pi }=\frac {n}{2} \sqrt {\frac {K_{\!S} (\lambda _0 - 1)}{M/\lambda _0}}. \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} f_n = \frac {\omega _n}{2\pi }=\frac {n}{2} \sqrt {\frac {K_{\!S} (\lambda _0 - 1)}{M/\lambda _0}}. \end{eqnarray}

For the first-order natural frequencies (

![]() $f_1$

), the analytical values for

$f_1$

), the analytical values for

![]() $K_{\!S} = 5$

,

$K_{\!S} = 5$

,

![]() $K_{\!S} = 39.2$

and

$K_{\!S} = 39.2$

and

![]() $K_{\!S} = 51.2$

are

$K_{\!S} = 51.2$

are

![]() $0.256$

,

$0.256$

,

![]() $0.717$

and

$0.717$

and

![]() $0.820$

, respectively. The relative error, given by

$0.820$

, respectively. The relative error, given by

![]() $ {\lvert f-f_1 \rvert }/{f_1}$

, remains within

$ {\lvert f-f_1 \rvert }/{f_1}$

, remains within

![]() $2.5\,\%$

, indicating strong agreement between the simulation results and the analytical solution.

$2.5\,\%$

, indicating strong agreement between the simulation results and the analytical solution.

Previous high-fidelity computational aeroelastic simulations of membrane airfoils (Gordnier Reference Gordnier2009; Jaworski & Gordnier Reference Jaworski and Gordnier2012, Reference Jaworski and Gordnier2015) provide additional background for the present numerical investigation.

3. Results and discussion

In our study, the Reynolds number, mass ratio, heaving amplitude and pre-stretch ratio are set to

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=200$

,

${\textit{Re}}=200$

,

![]() $M=1.0$

,

$M=1.0$

,

![]() $h_0/c=0.5$

and

$h_0/c=0.5$

and

![]() $\lambda _0=1.05$

, respectively. The values of

$\lambda _0=1.05$

, respectively. The values of

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $\lambda _0$

are selected based on previous studies (Jaworski & Gordnier Reference Jaworski and Gordnier2015; Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017; Tzezana & Breuer Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019). Bending stiffness

$\lambda _0$

are selected based on previous studies (Jaworski & Gordnier Reference Jaworski and Gordnier2015; Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017; Tzezana & Breuer Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019). Bending stiffness

![]() $K_{\kern-1pt B}=10^{-4}$

is chosen to be sufficiently small to neglect the bending effects while ensuring numerical stability in the Newmark-

$K_{\kern-1pt B}=10^{-4}$

is chosen to be sufficiently small to neglect the bending effects while ensuring numerical stability in the Newmark-

![]() $\beta$

integration and avoiding singularity of stiffness matrix. Further decreasing

$\beta$

integration and avoiding singularity of stiffness matrix. Further decreasing

![]() $K_{\kern-1pt B}$

to

$K_{\kern-1pt B}$

to

![]() $K_{\kern-1pt B}=10^{-6}$

has no effect on the thrust coefficient of the membrane. The effects of the stretching stiffness (

$K_{\kern-1pt B}=10^{-6}$

has no effect on the thrust coefficient of the membrane. The effects of the stretching stiffness (

![]() $1\lt K_{\!S}\lt \infty$

, where

$1\lt K_{\!S}\lt \infty$

, where

![]() $K_{\!S}=\infty$

represents a rigid plate), the Strouhal number (

$K_{\!S}=\infty$

represents a rigid plate), the Strouhal number (

![]() $0.2\leq {\textit{St}}_c \leq 0.4$

) and the pitching amplitude (

$0.2\leq {\textit{St}}_c \leq 0.4$

) and the pitching amplitude (

![]() $10^\circ \leq \theta _0\leq 20^\circ$

) on the propulsive performance of the compliant membrane are investigated.

$10^\circ \leq \theta _0\leq 20^\circ$

) on the propulsive performance of the compliant membrane are investigated.

3.1. Propulsive performance

Figure 3 shows the propulsive performance metrics as functions of the stretching stiffness

![]() $K_{\!S}$

for a representative pitching amplitude of

$K_{\!S}$

for a representative pitching amplitude of

![]() $\theta _0=15^{\circ }$

. As shown in figure 3(a), for all considered Strouhal numbers

$\theta _0=15^{\circ }$

. As shown in figure 3(a), for all considered Strouhal numbers

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

, the time-averaged thrust coefficient

${\textit{St}}_c$

, the time-averaged thrust coefficient

![]() $C_T$

increases with

$C_T$

increases with

![]() $K_{\!S}$

initially and then decreases, indicating the existence of an optimal

$K_{\!S}$

initially and then decreases, indicating the existence of an optimal

![]() $K_{\!S}$

(

$K_{\!S}$

(

![]() $K_{\!S}^*$

) that maximises thrust. Furthermore, as

$K_{\!S}^*$

) that maximises thrust. Furthermore, as

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

increases from

${\textit{St}}_c$

increases from

![]() $0.2$

to

$0.2$

to

![]() $0.4$

,

$0.4$

,

![]() $K_{\!S}^*$

also increases from

$K_{\!S}^*$

also increases from

![]() $K_{\!S}^*=20$

to

$K_{\!S}^*=20$

to

![]() $K_{\!S}^*=30$

. To quantify the propulsive performance enhancement of the membrane compared with the rigid plate, relative increment ratios are introduced. Figure 3(d) shows the thrust increment ratio

$K_{\!S}^*=30$

. To quantify the propulsive performance enhancement of the membrane compared with the rigid plate, relative increment ratios are introduced. Figure 3(d) shows the thrust increment ratio

![]() $\Delta C_T/C_{TR}=(C_T-C_{TR})/C_{TR}$

as a function of

$\Delta C_T/C_{TR}=(C_T-C_{TR})/C_{TR}$

as a function of

![]() $K_{\!S}$

, where

$K_{\!S}$

, where

![]() $C_{TR}$

is the time-averaged thrust coefficient of the rigid plate. It should be noted that the definition of

$C_{TR}$

is the time-averaged thrust coefficient of the rigid plate. It should be noted that the definition of

![]() $\Delta C_T/C_{TR}$

is valid only when

$\Delta C_T/C_{TR}$

is valid only when

![]() $C_{TR} \gt 0$

. For

$C_{TR} \gt 0$

. For

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c=0.2$

, the rigid plate experiences drag, whereas the membrane, due to the effect of in-plane stretching, generates thrust. For larger

${\textit{St}}_c=0.2$

, the rigid plate experiences drag, whereas the membrane, due to the effect of in-plane stretching, generates thrust. For larger

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

, the in-plane stretching enables the membrane to achieve a thrust enhancement that is

${\textit{St}}_c$

, the in-plane stretching enables the membrane to achieve a thrust enhancement that is

![]() $200\,\%$

of the rigid plate’s thrust, and

$200\,\%$

of the rigid plate’s thrust, and

![]() $\Delta C_T/C_{TR}$

decreases as

$\Delta C_T/C_{TR}$

decreases as

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

increases for each

${\textit{St}}_c$

increases for each

![]() $K_{\!S}$

.

$K_{\!S}$

.

Figure 3. (a) Time-averaged thrust coefficient

![]() $C_T$

, (b) time-averaged power coefficient

$C_T$

, (b) time-averaged power coefficient

![]() $C_{\!P}$

, (c) propulsive efficiency

$C_{\!P}$

, (c) propulsive efficiency

![]() $\eta$

, (d) thrust increment ratio

$\eta$

, (d) thrust increment ratio

![]() $({\Delta C_T}/{C_{TR}})$

, (e) maximum deflection over a cycle

$({\Delta C_T}/{C_{TR}})$

, (e) maximum deflection over a cycle

![]() $w_m$

and (f) propulsive efficiency increment ratio

$w_m$

and (f) propulsive efficiency increment ratio

![]() $({\Delta \eta }/{\eta _R})$

as functions of

$({\Delta \eta }/{\eta _R})$

as functions of

![]() $K_{\!S}$

for

$K_{\!S}$

for

![]() $\theta _0=15^{\circ }$

. The values of

$\theta _0=15^{\circ }$

. The values of

![]() $K_{\!S}^*$

indicate the optimal

$K_{\!S}^*$

indicate the optimal

![]() $K_{\!S}$

corresponding to the maximum

$K_{\!S}$

corresponding to the maximum

![]() $C_T$

in (a) and the maximum

$C_T$

in (a) and the maximum

![]() $\eta$

in (c). Note that the cases with

$\eta$

in (c). Note that the cases with

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c=0.2$

(red curves) are not included in (

${\textit{St}}_c=0.2$

(red curves) are not included in (

![]() $d$

) and (

$d$

) and (

![]() $f$

), as they generate drag. Body profiles of the membrane during (g) downstroke and (h) upstroke for

$f$

), as they generate drag. Body profiles of the membrane during (g) downstroke and (h) upstroke for

![]() $K_{\!S}=12.5$

,

$K_{\!S}=12.5$

,

![]() ${\textit{St}}=0.32$

and

${\textit{St}}=0.32$

and

![]() $\theta =15^{\circ }$

. (i) Variation of lift coefficient

$\theta =15^{\circ }$

. (i) Variation of lift coefficient

![]() $C_L$

and prescribed heaving velocity

$C_L$

and prescribed heaving velocity

![]() $\dot {h}$

within one cycle for three representative

$\dot {h}$

within one cycle for three representative

![]() $K_{\!S}$

values under

$K_{\!S}$

values under

![]() ${\textit{St}}=0.32$

and

${\textit{St}}=0.32$

and

![]() $\theta =15^{\circ }$

.

$\theta =15^{\circ }$

.

Figure 3(b) shows that the time-averaged power coefficient

![]() $C_{\!P}$

decreases monotonically as

$C_{\!P}$

decreases monotonically as

![]() $K_{\!S}$

increases for each

$K_{\!S}$

increases for each

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

. Combined with the trend of the time-averaged thrust coefficient with respect to

${\textit{St}}_c$

. Combined with the trend of the time-averaged thrust coefficient with respect to

![]() $K_{\!S}$

, this indicates that, in general, higher thrust is achieved at the expense of increased input power. According to the definition of the power coefficient, since the motion in the streamwise (

$K_{\!S}$

, this indicates that, in general, higher thrust is achieved at the expense of increased input power. According to the definition of the power coefficient, since the motion in the streamwise (

![]() $x$

) direction is constrained (no prescribed translation), the input power mainly originates from the contributions of the force and velocity in the transverse (

$x$

) direction is constrained (no prescribed translation), the input power mainly originates from the contributions of the force and velocity in the transverse (

![]() $y$

) direction. Therefore, we introduce the maximum deflection relative to the undeformed state of the membrane across the chord at each instant during a flapping period, denoted as

$y$

) direction. Therefore, we introduce the maximum deflection relative to the undeformed state of the membrane across the chord at each instant during a flapping period, denoted as

![]() $w(t)$

, while

$w(t)$

, while

![]() $w_m$

represents the maximum absolute value of

$w_m$

represents the maximum absolute value of

![]() $w$

over a full cycle. Figure 3(e) shows that

$w$

over a full cycle. Figure 3(e) shows that

![]() $w_m$

decreases monotonically as

$w_m$

decreases monotonically as

![]() $K_{\!S}$

increases.

$K_{\!S}$

increases.

During both the downstroke and upstroke, as the prescribed heaving velocity

![]() $\dot {h}$

increases from zero to its maximum and then decelerates back to zero, the membrane deflection also evolves from its nearly minimum to nearly maximum and back, as shown in figures 3(g) and 3(h), respectively. During the deceleration stage, the elastic rebound of the membrane enhances the transverse (

$\dot {h}$

increases from zero to its maximum and then decelerates back to zero, the membrane deflection also evolves from its nearly minimum to nearly maximum and back, as shown in figures 3(g) and 3(h), respectively. During the deceleration stage, the elastic rebound of the membrane enhances the transverse (

![]() $y$

-direction) velocity of each part of the membrane. Therefore, a larger

$y$

-direction) velocity of each part of the membrane. Therefore, a larger

![]() $w_m$

helps maintain higher transverse velocities during the deceleration phase, which partially explains the monotonic increase of the power coefficient with decreasing

$w_m$

helps maintain higher transverse velocities during the deceleration phase, which partially explains the monotonic increase of the power coefficient with decreasing

![]() $K_{\!S}$

.

$K_{\!S}$

.

In addition, figure 3(i) shows the variation of the lift coefficient

![]() $C_L$

over one flapping cycle. For smaller

$C_L$

over one flapping cycle. For smaller

![]() $K_{\!S}$

, the phase transition of

$K_{\!S}$

, the phase transition of

![]() $C_L$

from positive to negative lags behind the reversal of

$C_L$

from positive to negative lags behind the reversal of

![]() $\dot {h}$

. Similar hysteresis phenomena have been reported in previous studies (Song et al. Reference Song, Tian, Israeli, Galvao, Bishop, Swartz and Breuer2008; Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017; Upfal et al. Reference Upfal, Zhu, Handy-Cardenas and Breuer2025), where they were attributed to the persistence of the membrane deformation direction when the flapping motion reverses. This is consistent with the body profiles shown in figures 3(g) and 3(h), where the membrane is not flat at

$\dot {h}$

. Similar hysteresis phenomena have been reported in previous studies (Song et al. Reference Song, Tian, Israeli, Galvao, Bishop, Swartz and Breuer2008; Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017; Upfal et al. Reference Upfal, Zhu, Handy-Cardenas and Breuer2025), where they were attributed to the persistence of the membrane deformation direction when the flapping motion reverses. This is consistent with the body profiles shown in figures 3(g) and 3(h), where the membrane is not flat at

![]() $t/T=0$

,

$t/T=0$

,

![]() $1/2$

and

$1/2$

and

![]() $1$

. As

$1$

. As

![]() $K_{\!S}$

decreases, the amplitude of

$K_{\!S}$

decreases, the amplitude of

![]() $C_L$

increases, as shown in figure 3(i), which provides another explanation for the monotonic increase of the power coefficient with decreasing

$C_L$

increases, as shown in figure 3(i), which provides another explanation for the monotonic increase of the power coefficient with decreasing

![]() $K_{\!S}$

. In the next section, the variation of the

$K_{\!S}$

. In the next section, the variation of the

![]() $C_L$

amplitude with

$C_L$

amplitude with

![]() $K_{\!S}$

will be further discussed in relation to the analysis of the flow field.

$K_{\!S}$

will be further discussed in relation to the analysis of the flow field.

Since

![]() $C_T$

varies non-monotonically with

$C_T$

varies non-monotonically with

![]() $K_{\!S}$

, while

$K_{\!S}$

, while

![]() $C_{\!P}$

varies monotonically with

$C_{\!P}$

varies monotonically with

![]() $K_{\!S}$

, the propulsive efficiency

$K_{\!S}$

, the propulsive efficiency

![]() $\eta =C_T/C_{\!P}$

also varies non-monotonically with

$\eta =C_T/C_{\!P}$

also varies non-monotonically with

![]() $K_{\!S}$

, as shown in figure 3(c). Similar to

$K_{\!S}$

, as shown in figure 3(c). Similar to

![]() $C_T$

, there exists

$C_T$

, there exists

![]() $K_{\!S}^*$

that maximises the propulsive efficiency. Furthermore, as

$K_{\!S}^*$

that maximises the propulsive efficiency. Furthermore, as

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

increases from

${\textit{St}}_c$

increases from

![]() $0.2$

to

$0.2$

to

![]() $0.4$

,

$0.4$

,

![]() $K_{\!S}^*$

increases from

$K_{\!S}^*$

increases from

![]() $20$

to

$20$

to

![]() $70$

. Figure 3(

$70$

. Figure 3(

![]() $f$

) shows the propulsive efficiency increment ratio

$f$

) shows the propulsive efficiency increment ratio

![]() $\Delta \eta /\eta _R=(\eta -\eta _R)/\eta _R$

as a function of

$\Delta \eta /\eta _R=(\eta -\eta _R)/\eta _R$

as a function of

![]() $K_{\!S}$

, where

$K_{\!S}$

, where

![]() $\eta _R$

is the propulsive efficiency coefficient of the rigid plate. The propulsive efficiency increment ratio follows a similar trend to the thrust increment ratio as

$\eta _R$

is the propulsive efficiency coefficient of the rigid plate. The propulsive efficiency increment ratio follows a similar trend to the thrust increment ratio as

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

and

${\textit{St}}_c$

and

![]() $K_{\!S}$

change, and in-plane stretching can increase the membrane’s propulsive efficiency by up to

$K_{\!S}$

change, and in-plane stretching can increase the membrane’s propulsive efficiency by up to

![]() $100\,\%$

compared with the rigid plate.

$100\,\%$

compared with the rigid plate.

To analyse the dynamic response of the membrane, the frequency ratio

![]() $f^*$

, defined as the ratio of the flapping frequency to the first-order natural frequency of the membrane in a uniform incoming flow (the latter is deduced in Tzezana & Breuer Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019), is introduced as

$f^*$

, defined as the ratio of the flapping frequency to the first-order natural frequency of the membrane in a uniform incoming flow (the latter is deduced in Tzezana & Breuer Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019), is introduced as

\begin{eqnarray} f^*=\frac {f}{f_1}=2 {\textit{St}}_c \sqrt {\frac {M/\lambda _0 + M_A}{K_{\!S} (\lambda _0-1)}}, \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} f^*=\frac {f}{f_1}=2 {\textit{St}}_c \sqrt {\frac {M/\lambda _0 + M_A}{K_{\!S} (\lambda _0-1)}}, \end{eqnarray}

where

![]() $M_A$

is the added mass coefficient and

$M_A$

is the added mass coefficient and

![]() $M_A = 0.5$

is obtained in Tzezana & Breuer (Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019). Note that

$M_A = 0.5$

is obtained in Tzezana & Breuer (Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019). Note that

![]() $f^*=0$

corresponds to the rigid-plate limit (

$f^*=0$

corresponds to the rigid-plate limit (

![]() $K_{\!S} \to \infty$

), for which no deformation occurs.

$K_{\!S} \to \infty$

), for which no deformation occurs.

Figure 4. (a) Variation of

![]() $w_m$

as a function of

$w_m$

as a function of

![]() $f^*$

for four different values of

$f^*$

for four different values of

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

(represented by different symbol shapes), with

${\textit{St}}_c$

(represented by different symbol shapes), with

![]() $\theta _0 = 10^{\circ }$

(red symbols),

$\theta _0 = 10^{\circ }$

(red symbols),

![]() $\theta _0 = 15^{\circ }$

(green symbols) and

$\theta _0 = 15^{\circ }$

(green symbols) and

![]() $\theta _0 = 20^{\circ }$

(blue symbols). (b) Predicted

$\theta _0 = 20^{\circ }$

(blue symbols). (b) Predicted

![]() $w^{\prime }_{t^*}$

versus numerically simulated

$w^{\prime }_{t^*}$

versus numerically simulated

![]() $w_{t^*}$

at

$w_{t^*}$

at

![]() $t= {T}/{4}$

and

$t= {T}/{4}$

and

![]() $t= {(3T)}/{4}$

for all

$t= {(3T)}/{4}$

for all

![]() $\theta _0$

and

$\theta _0$

and

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

. The dashed black line indicates

${\textit{St}}_c$

. The dashed black line indicates

![]() $w^{\prime }_{t^*}=w_{t^*}$

.

$w^{\prime }_{t^*}=w_{t^*}$

.

Figure 4(a) shows the variation of

![]() $w_m$

with the frequency ratio

$w_m$

with the frequency ratio

![]() $f^*$

for three different pitching amplitudes (

$f^*$

for three different pitching amplitudes (

![]() $\theta _0=10^\circ$

,

$\theta _0=10^\circ$

,

![]() $15^\circ$

and

$15^\circ$

and

![]() $20^\circ$

). Here,

$20^\circ$

). Here,

![]() $f^*$

nearly collapses

$f^*$

nearly collapses

![]() $w_m$

from different

$w_m$

from different

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

and

${\textit{St}}_c$

and

![]() $\theta _0$

onto a single curve, and

$\theta _0$

onto a single curve, and

![]() $w_m$

increases monotonically with

$w_m$

increases monotonically with

![]() $f^*$

before reaching the resonance. For the instantaneous maximal deflection

$f^*$

before reaching the resonance. For the instantaneous maximal deflection

![]() $w(t)$

, it can be approximated as a steady-state response for simplicity and derived based on the Young–Laplace equation (Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017; Mathai et al. Reference Mathai, Tzezana, Das and Breuer2022)

$w(t)$

, it can be approximated as a steady-state response for simplicity and derived based on the Young–Laplace equation (Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017; Mathai et al. Reference Mathai, Tzezana, Das and Breuer2022)

where

![]() $\kappa$

is the curvature,

$\kappa$

is the curvature,

![]() $p$

is the pressure difference across the membrane and

$p$

is the pressure difference across the membrane and

![]() $\mathcal{T}$

is the tension. Assuming that the deformation of the membrane is a circular arc with camber

$\mathcal{T}$

is the tension. Assuming that the deformation of the membrane is a circular arc with camber

![]() $w$

, the following relationships can be derived from the geometry:

$w$

, the following relationships can be derived from the geometry:

![]() $\kappa =8w/(1+4w^2)$

,

$\kappa =8w/(1+4w^2)$

,

![]() $\lambda =(2\lambda _0/\kappa )\sin ^{-1}(\kappa /2)$

and

$\lambda =(2\lambda _0/\kappa )\sin ^{-1}(\kappa /2)$

and

![]() $\mathcal{T}=Eh(\lambda -1)$

. The pressure across the membrane is calculated by the thin-airfoil theory (Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017)

$\mathcal{T}=Eh(\lambda -1)$

. The pressure across the membrane is calculated by the thin-airfoil theory (Waldman & Breuer Reference Waldman and Breuer2017)

where

![]() $\alpha _{e}$

is the instantaneous effective angle of attack. By substituting the expressions for

$\alpha _{e}$

is the instantaneous effective angle of attack. By substituting the expressions for

![]() $\alpha _{e}$

, pressure

$\alpha _{e}$

, pressure

![]() $p$

, and curvature

$p$

, and curvature

![]() $\kappa$

into the Young–Laplace equation (3.2), and non-dimensionalising using the membrane’s fixed-end length

$\kappa$

into the Young–Laplace equation (3.2), and non-dimensionalising using the membrane’s fixed-end length

![]() $c$

as the length scale and

$c$

as the length scale and

![]() $\rho U_\infty ^2$

as the pressure scale, the resulting non-dimensional equation is expressed as

$\rho U_\infty ^2$

as the pressure scale, the resulting non-dimensional equation is expressed as

\begin{eqnarray} \frac {\pi \sin \left(\alpha _{e}+\dfrac {1}{2}\sin ^{-1}(\tilde {\kappa }(\tilde {w}/2))\right)}{(\lambda (\tilde {w})-1)\tilde {\kappa }(\tilde {w})}=K_{\!S}, \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \frac {\pi \sin \left(\alpha _{e}+\dfrac {1}{2}\sin ^{-1}(\tilde {\kappa }(\tilde {w}/2))\right)}{(\lambda (\tilde {w})-1)\tilde {\kappa }(\tilde {w})}=K_{\!S}, \end{eqnarray}

where

![]() $\tilde{\,}$

represents the non-dimensionalised quantities.

$\tilde{\,}$

represents the non-dimensionalised quantities.

Figure 4(b) presents the instantaneous maximal deflection at two instants,

![]() $t^* = {T}/{4}$

and

$t^* = {T}/{4}$

and

![]() $t^* = {(3T)}/{4}$

, where

$t^* = {(3T)}/{4}$

, where

![]() $T$

is the flapping period. The instantaneous maximal deflections, obtained from (3.4) and numerical simulations, are denoted as

$T$

is the flapping period. The instantaneous maximal deflections, obtained from (3.4) and numerical simulations, are denoted as

![]() $w_{t^*}^\prime$

and

$w_{t^*}^\prime$

and

![]() $w_{t^*}$

, respectively. The results show good agreement between the two approaches. The discrepancy between

$w_{t^*}$

, respectively. The results show good agreement between the two approaches. The discrepancy between

![]() $w_{t^*}^\prime$

and

$w_{t^*}^\prime$

and

![]() $w_{t^*}$

increases with

$w_{t^*}$

increases with

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

, and can be explained as follows:

${\textit{St}}_c$

, and can be explained as follows:

![]() $w_{t^*}^\prime$

is derived based on steady-state theory, which assumes that the deformation is a symmetric circular arc. However, a larger

$w_{t^*}^\prime$

is derived based on steady-state theory, which assumes that the deformation is a symmetric circular arc. However, a larger

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

corresponds to a higher flapping frequency, where dynamic effects become more pronounced, and the deformation deviates from a symmetric circular arc, as shown in figures 9 and 10. These dynamic deviations lead to a greater divergence of the

${\textit{St}}_c$

corresponds to a higher flapping frequency, where dynamic effects become more pronounced, and the deformation deviates from a symmetric circular arc, as shown in figures 9 and 10. These dynamic deviations lead to a greater divergence of the

![]() $w_{t^*}^\prime$

–

$w_{t^*}^\prime$

–

![]() $w_{t^*}$

comparison from the

$w_{t^*}$

comparison from the

![]() $x = y$

line.

$x = y$

line.

Figure 5. (

![]() $a$

,

$a$

,

![]() $d$

,

$d$

,

![]() $g$

) The thrust coefficient

$g$

) The thrust coefficient

![]() $C_T$

, (

$C_T$

, (

![]() $b$

,

$b$

,

![]() $e$

,

$e$

,

![]() $h$

) power coefficient

$h$

) power coefficient

![]() $C_{\!P}$

and (

$C_{\!P}$

and (

![]() $c$

,

$c$

,

![]() $f$

,

$f$

,

![]() $i$

) propulsive efficiency

$i$

) propulsive efficiency

![]() $\eta$

as functions of

$\eta$

as functions of

![]() $f^*$

for (

$f^*$

for (

![]() $a$

–

$a$

–

![]() $c$

)

$c$

)

![]() $\theta _0=10^{\circ }$

, (

$\theta _0=10^{\circ }$

, (

![]() $d$

–

$d$

–

![]() $f$

)

$f$

)

![]() $\theta _0=15^{\circ }$

and (

$\theta _0=15^{\circ }$

and (

![]() $g$

–

$g$

–

![]() $i$

)

$i$

)

![]() $\theta _0=20^{\circ }$

, respectively.

$\theta _0=20^{\circ }$

, respectively.

Figure 5 presents the propulsive performance metrics (

![]() $C_T$

,

$C_T$

,

![]() $C_{\!P}$

and

$C_{\!P}$

and

![]() $\eta$

) as functions of the frequency ratio (

$\eta$

) as functions of the frequency ratio (

![]() $f^*$

) for three different pitching amplitudes (

$f^*$

) for three different pitching amplitudes (

![]() $\theta _0=10^\circ$

,

$\theta _0=10^\circ$

,

![]() $15^\circ$

and

$15^\circ$

and

![]() $20^\circ$

). It can be observed that, for each combination of

$20^\circ$

). It can be observed that, for each combination of

![]() $\theta _0$

and

$\theta _0$

and

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

, the thrust coefficient (

${\textit{St}}_c$

, the thrust coefficient (

![]() $C_T$

) first increases and then decreases with increasing

$C_T$

) first increases and then decreases with increasing

![]() $f^*$

, exhibiting an optimal frequency ratio (

$f^*$

, exhibiting an optimal frequency ratio (

![]() $f^*_{\textit{opt}}$

) that maximises

$f^*_{\textit{opt}}$

) that maximises

![]() $C_T$

. The values of

$C_T$

. The values of

![]() $f^*_{\textit{opt}}$

are explicitly marked in figure 5(

$f^*_{\textit{opt}}$

are explicitly marked in figure 5(

![]() $a$

,

$a$

,

![]() $d$

,

$d$

,

![]() $g$

). This trend is consistent with the theoretical results of Tzezana & Breuer (Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019), which indicate that, as

$g$

). This trend is consistent with the theoretical results of Tzezana & Breuer (Reference Tzezana and Breuer2019), which indicate that, as

![]() $f^*$

increases, the thrust initially rises and then transitions to drag near resonance. Additionally, for each

$f^*$

increases, the thrust initially rises and then transitions to drag near resonance. Additionally, for each

![]() $\theta _0$

, as

$\theta _0$

, as

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$

increases,

${\textit{St}}_c$

increases,

![]() $f^*_{\textit{opt}}$

also increases. However, for a given

$f^*_{\textit{opt}}$

also increases. However, for a given

![]() ${\textit{St}}_c$