Introduction

In Western countries, living with parents is a reality for many young adults aged between 18 and 34 years old (see online Appendix A). In 2019, across Europe, 49 per cent of the 18–34 year olds cohabited with their parents, while they were 32 per cent to do so among the 25–34 age group. Cohabitation can be the result of multiple factors ranging from the length of time spent in school, low wages at the beginning of a career, the difficulty of landing a first job, the cost of housing or any life shocks that prompt emerging adults to stay with their parents. Several consequences of this living arrangement are already well documented by social scientists. These include depressive symptoms among parents (Tosi, Reference Tosi2020) or young adults living with parents (Copp et al., Reference Copp, Giordano, Longmore and Manning2017), or children's lower income later in life (Billari & Tabellini, Reference Billari and Tabellini2010).

Despite much research in social science on living arrangements between emerging adults and their parents, we lack an understanding of its implications regarding political stances. My focus on the implications of this social trend for political opinions is motivated by the literature on everyday life experience and economic anxiety. We know from previous research that the spatial or social context in which individuals live influences their perception of the economy. For instance, a high share of unemployed individuals in a neighbourhood is associated with a negative assessment of the national economy (Bisgaard et al., Reference Bisgaard, Sønderskov and Dinesen2016). Being aware of economic difficulties in one's social circle influences the perception of the economy, just as much as discussing politics between spouses or relatives can influence people's political opinions and behaviour in a social group (Daenekindt et al., Reference Daenekindt, de Koster and van der Waal2020; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Velez, Hartman and Bankert2015). Hence, we might expect that economic difficulties affecting children will render parents more anxious about the overall economic conditions, mimicking a contagion effect among household members. Since cohabitation between parents and young adults is mostly explained by economic difficulties (Matsudaira, Reference Matsudaira2016), it likely triggers negative evaluations among children regarding the current state of the national economy and political actors; since both can be held accountable for the economic difficulties encountered by young adults.

Based on these motivations, I investigate whether cohabitation between young adults and their parents is correlated with negative opinions about the national economy and government performance among parents and working age children. By seeing their children struggle to achieve emancipation, parents are likely to form a more pessimistic view of the country's economic situation and evaluate the government's performance more negatively; while young adults who remain with their parents are also expected to become more negative as their age increases and social norms regarding the need of flying the nest become more pressing.

My contribution to the field of public opinion research is twofold. First, I provide further evidence of the importance of everyday life context for opinion formation. Being exposed to someone's economic uncertainty on a daily basis, through cohabitation, might influence the economic attitudes of household members. Second, my results underline the importance of accounting for the presence of young adults in the household when studying both parent's and children's opinions. Traditional studies in opinion formation usually take into account the household economic context by controlling for the household material well‐being or employment situation between partners. However, economic hardship faced by working age children can affect political views within the household just as much as the economic uncertainty of one partner on the other. Since the co‐residence between young adults and their parents is widespread in Western countries, social scientists should consider this factor when studying political opinion.

Constrained cohabitation as a proxy for the economic uncertainty

Facing high unemployment rates (see online Appendix B) and a housing affordability crisis, young adults can use different strategies to adapt to a disadvantageous socioeconomic context. One of these strategies is to stay or return to their parent's place which allows them to save on rent at least and rely on material help from parents at best (Swartz et al., Reference Swartz, Kim, Uno, Mortimer and O'Brien2011). That economic conditions motivate children's moving‐out decision is already well grounded in the economic literature (Matsudaira, Reference Matsudaira2016). An unfavourable economic context undermines young adults' ability to face rental cost let alone home ownership. Because difficulties in accessing the housing market are a precursor of young adults' economic uncertainty, some European countries have tried to mitigate those difficulties by providing emerging adults with financial help in order to make housing more affordable for youngsters. If social benefits are not provided by the state, parents themselves might be able to help their children financially, by providing financial support for living costs during their studies or when they enter the labour market. Lacking such support from either parents or the state, young adults may be forced to stay or return to live with their parents if they are unable to afford their independence.

This observation is crucial when considering the economic context in which an individual evolves and how this context is studied. Much research measures the economic situation of an individual by means of their income, employment situation or assets. Others have drawn attention to the fact that individuals are not isolated but are affected by their surroundings, with a focus on neighbourhood effects (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Velez, Hartman and Bankert2015). These factors usually serve as proxies for estimating the economic conditions of a respondent in opinion surveys, since one's personal economic situation can influence opinions on many topics, especially economic ones. But with equal earnings as well as the same (un)employment status, some young adults can be financially helped by their parents – or the state when they have access to subsidies – and hence experience independence, whereas others who lack such support might be constrained to stay with their parents. Given the specific difficulties of the younger generations who in recent years have faced housing crises, high unemployment rates, precarious contracts and low wages, traditional measures are particularly problematic for capturing their economic conditions. For this reason, I make use of the constrained cohabitation with parents as a proxy that captures the economic conditions that young adults face. I expect cohabitation to be negatively correlated with citizens' perceptions of the state of the national economy.

I conceive cohabitation as a proxy for the economic situation of young cohorts as a whole and not the respondent alone. Precisely, cohabitation can soften the blow of job loss or low wages. With parental help through cohabitation, a young adult will then be sheltered as regard to material well‐being and perhaps even be able to save some money. Yet, this does not alter the fact that such young adults are unable to become independent which likely fosters frustration about the economic situation reserved for the vast majority of emerging adults. I assume that cohabitation likely has an influence on personal economic perceptions too, but here my interest is in perceptions of the state of the national economy.

Hypotheses

In this research note, I test two hypotheses that are primarily motivated by the literature on the role of the household context on political attitudes (Huckfeldt & Sprague, Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995), peer effects (Dahl et al., Reference Dahl, Løken and Mogstad2014) and the economic voting literature (Lewis‐Beck & Stegmaier, Reference Lewis‐Beck and Stegmaier2000). First, I argue that young adults living with parents evaluate the economy and the government more negatively compared to independent individuals of the same age (I label this hypothesis the Children hypothesis). This hypothesis relies on the peer effect theory and social stigma associated with long‐lasting cohabitation with parents. The premise being that, as a young adult grows older, more and more of their peers no longer live with their parents. As such, those who are lagging behind in acquiring their independence will tend to worry about their situation when comparing themselves to their independent peers and have more pessimistic opinions overall. Hence, I expect the negative effect of cohabitation among young adults to be conditional on their age.

Hypothesis 1. Children hypothesis. As age increases between 18 and 34 years old, living with parents is associated with a lower level of satisfaction with the [economy/government] compared to young adults living without their parents.

Second, mirroring their children's political opinions, parents who are exposed on a daily basis to the economic difficulties faced by their adult children – that materialize by means of cohabitation – should also be less satisfied with the economy or the government's performance compared to parents living with children under 18 or childless individuals (Parents hypothesis). The crucial element from the parents' perspective is the psychological dimension of seeing their adult child unable to become independent. Seeing their children struggle to become independent should induce anxiety among parents mimicking a contagion – effect that translates into negative political stances. Hence, parents might be tempted to blame the economy and actors responsible for it such as the government.

Hypothesis 2. Parents hypothesis. Living with adult children is associated with lower satisfaction with the [economy/government] compared to parents who do not cohabit with adult children.

Before turning to the empirical results, I briefly consider the possibility that the effects of cohabitation are gendered. We know from previous research that parenthood affects political preferences (see, for instance, Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Elder, Greene and Stevens2016, on the consequences of parenthood in Europe). Importantly, we also know that parenthood can trigger different reactions between mothers and fathers (Burlacu & Lühiste, Reference Burlacu and Lühiste2021; Klar et al., Reference Klar, Madonia and Schneider2014). Given that parenthood is gendered, it could be argued that the parental role moderates the association between cohabitation and political views. In the Supporting Information (in Appendix T), I, therefore, explore heterogeneity in the association based on parents' gender. The results show that, compared to fathers, mothers cohabiting with a young adult tend to hold more negative opinions on the economy and government's performance. However, this difference is not statistically significant.

Research design and data

To test my two hypotheses, I use the European Social Survey (ESS) from 2002 to 2016 (8 waves, every 2 years), in 32 countries. I use two dependent variables, the respondent's satisfaction with the economy and with government performance, both are measured on a scale running from 0 to 10, where 0 refers to extremely dissatisfied and 10 refers to extremely satisfied.

The main independent variable varies depending on which hypothesis is tested. For the Children hypothesis, the coefficient of interest is the interaction between a binary variable capturing whether the respondent still lives with their parents (variable named Cohabitation with parents) and their age. The cohabitation variable is coded 1 if the respondent lives with her parents, 0 if not, and age is measured in years, that is continuously. Due to my theory, the Children hypothesis focuses on a restricted sample of respondents, that is, individuals aged less than 34 years old. The choice of a cut‐off at 34 is partly arbitrary but motivated by the traditional use of the 18–34 age group (as the ilc_lvps08 indicator from Eurostat) when referring to young adults. The incorporation of older respondents could then cover the scenario of children taking care of their parents who become non‐independent due to their health condition, which is out of this study's scope. With respect to the Parents hypothesis, the main explanatory variable is Cohabitation with children. I use a binary measure, where 1 refers to the presence of over 18 years‐old and under 34 years‐old children in the household, 0 otherwise (e.g., parents with only children under 18, parents who do not cohabit with their children or childless individuals). A binary measure is in line with the theory since it allows a comparison between parents who cohabit with young adults and those who do not. However, this coding might hide important information in terms of household composition. To address concerns about heterogeneity in household composition, I provide an alternative measure that contains five categories: (1) never had children at home, (2) have had children at home but not currently, (3) only children under 18 at home, (4) mixed household (children under and above 18 at home), (5) only children above 18 at home.

As for the Children hypothesis, young adults taken into account for the Parents hypothesis are only those from 18 to 34 years old, in order to fit with my theoretical expectations and to minimize measurement errors as much as possible. This brings me to mention a potential bias regarding both cohabitation variables. The main unobserved factor is whether living with their parents is a choice or a constraint for children. I can only assume that, from a certain age, the majority of young adults will want to gain independence. This desire for independence should grow as one gets older as expected from the peer effect theory and social stigma associated with long‐lasting cohabitation between working age children and parents. Hence, if not socially or personally desired, remaining with one's parents reflects constraints motivated by economic conditions. Since information on the motivations for cohabitation with parents is not available, it can be seen as a measurement error in the independent variable (i.e., the cohabitation variable, for both hypotheses).

I control for a respondent's age in years, the household total income, the respondent's level of education (in years) and whether the respondent is unemployed and actively looking for a job at the time of the survey (1 if unemployed, 0 if not). To account for change in the economic context from year to year within each country, I control for the yearly unemployment rate. When testing the Children hypothesis, I also control for the respondent being at school or not at the time of the survey (coded 1 if at school 0 otherwise). The information regarding the enrollment of children at school is only used for the Children hypothesis. The ESS survey provides information on occupation for the respondent and their partner only, and not for other household members. Therefore, models for the Parents hypothesis do not control for whether children are still at school. I decided to not include support for the incumbent party in the main models since doing so might introduce post‐treatment bias. However, controlling for identification with the incumbent party yields similar results through various coding decisions (see online Appendix J, K, M, and N). Question wordings are listed in online Appendix C and descriptive statistics of all variables in online Appendix E.

Finally, both hypotheses are estimated by means of a linear regression with country and year fixed effects, standard errors are double clustered at the level of year and country and I consistently apply post‐stratification weights. Further justification of the method as well as equations for testing each hypothesis are available in online Appendix G. Finally, the full tables for each model presented in the paper as well as those for the robustness checks are presented in the online appendices.

Results

The Children hypothesis aims to assess whether, as age increases, living with parents is associated with lower levels of satisfaction with the economy or the government's performance compared to independent adults.

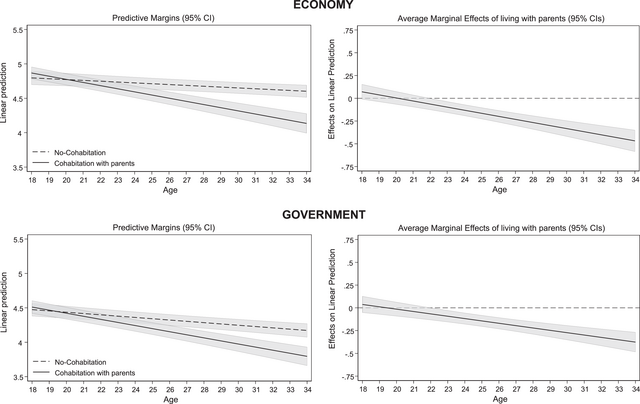

Figure 1 shows the results in two ways. The left panels show the linear prediction of satisfaction with the economy (top panel) or the government (bottom panel), conditional on whether the respondent lives with their parents, as well as their age at the time of the survey. The right panels show the average marginal effect on satisfaction with the economy or government of a shift in cohabitation from 0 (no cohabitation) to 1 (cohabitation with parents). As can be seen in the left panels of Figure 1 (the predictive margins), as age increases, young adults living with their parents tend to hold more negative views of the economy (top panel) or government performance (bottom panel) compared to those who do not. The dashed line (No‐cohabitation) looks almost stable across age in both left panels meaning that age is not associated with meaningful change in opinion regarding the economy or the government conditional on being independent. The solid line (Cohabitation) pictures a slightly different behaviour: among individuals who cohabit with their parents, as one gets older their satisfaction with the economy or government decreases to a greater extent. The average marginal effects (right panels) for both dependent variables show when the differences between groups are significant. Thus, before reaching 22–23 years, young adults cohabiting with their parents do not hold different views of the economy or the government compared to their independent peers. In other words, there is a difference between both groups, but it is not significant at the conventional level. Perhaps, since living with parents appears to be the norm among this age group, children might not find their living arrangement abnormal compared to their independent peers, or they do not really feel worried about their situation. Hence, the evaluation of both the economy or the government is not correlated with the living arrangement. However, the path diverges and the difference becomes significant in the mid‐twenties: after 23 years old, the gap between the two groups widens as age increases. The pattern is similar for both dependent variables.

Figure 1. Predictive margins and marginal effects of living with parents on children's level of satisfaction with the economy or government's performance.

Note: Derived from the Model 4 presented in Table 1 in online Appendix H for the economy (top panels) and Model 8 in Table 1 for the government's performance (bottom panels) in online Appendix I.

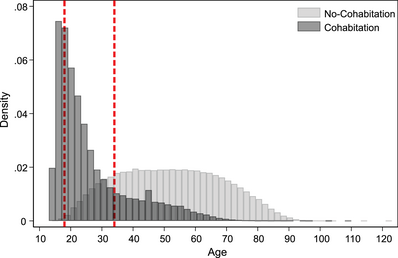

The results are in line with the distribution of cohabiting and non‐cohabiting individuals in different age groups. More specifically, Figure 2 shows that around the age of 30 years old and onward, non‐independents become a minority and hence being independent becomes the norm. While this cannot be entirely proved through the data, this more negative turn in the opinions of the non‐independents is probably the outcome of a comparison with their peers, for example, in their circle of friends or colleagues, where the norm becomes to be independent. Since I assume that cohabitation is constrained by economic reasons, additional effects of seeing one's peers gain independence might explain this increasing gap between groups and the decreasing satisfaction with both the economy and the government.

Figure 2. Distribution of the respondents according to whether they live with their parents or not. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The first red line indicates 18 years of age for the x‐axis, while the second red line indicates 34.

The aim of the Parents hypothesis is to assess whether, among parents, having young adults in the household is correlated with a lower level of satisfaction with the economy or government performance compared to parents with no child at home or only children under 18. Before discussing the results, I would like to bring the reader's attention on the rationale behind the restrictions I made regarding the sample. First, in line with the Children hypothesis, the Cohabitation with children variable takes into account cohabitation with young adults aged between 18 and 34 year olds (coded 1) and under 18 or no child at home (coded 0). These age restrictions serve to rule out the case where parents would live at their children's place due to their caregiving needs. Obviously, it is impossible to entirely rule out that individuals over 34 years of age may still be living at their parents' home for economic reasons. However, in order to minimize measurement errors as much as possible, it seems important to proceed with the most rational scenario taking into account the limitations of the survey. Hence, I assume that beyond 34 years old, individuals living with their parents are more likely to be in a position to take care of them rather than the reverse. In addition to the limitation to the 18–34 age group in the coding of the main explanatory variable, I opted to exclude from the analysis the respondents aged between 18 and 34 years old. Retaining this age group as part of the analysis of the Parents hypothesis implies that children still living with their parents or not would be studied under both hypotheses, which would introduce a bias by means of measurement error.

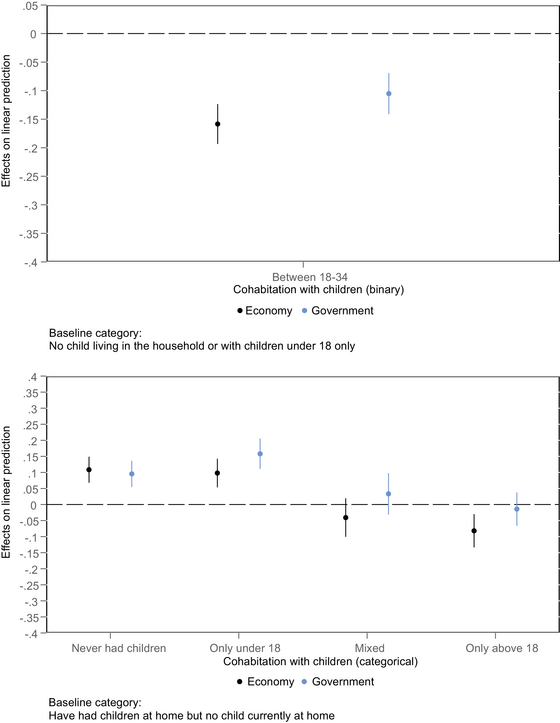

The top panel from Figure 3 shows the association between a cohabitation with children aged between 18 and 34 and the satisfaction with the economy or government's performance among parents compared to parents without children over 18 at home. As can be seen, the presence of young adults in the household is associated with less satisfaction with the economy or government performance compared to the baseline category. More specifically, when looking at the results using the binary variable, having children above 18 and under 34 in the household compared to no child or under 18 decreases the satisfaction with the economy by 0.16 points on a scale ranging from 0 to 10 (see Model 1 in online Appendix L). Although effects are quite comparable for the second dependent variable Government, that is, a negative coefficient among parents with only children over the age of 18, the coefficient's size is smaller (−0.11, Model 3, online Appendix L).

Figure 3. Effects of household composition on satisfaction with the economy or government's performance. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Results from the categorical variable (see the bottom panel, Figure 3) allow to reach a similar conclusion since only households with children above 18 years old (see “Only above 18”) are less satisfied with the economy compared to households who have had children at home but not currently. However, regarding the satisfaction with the government's performance, the coefficient is close to 0 and not significant at the conventional level (see category “Only above 18” in Model 4, online Appendix L). Overall, the results support the main hypothesis that living with young adults might induce anxiety among parents; and this anxiety can be expressed by a dissatisfaction toward factors that are more likely to be seen as the reason behind the difficulties encountered by those non‐independent children, that is, the economy and the government. As expected, having only young adults aged 18 or older in the household yields the most substantial effect regarding the satisfaction with the economy.

Finally, I provide several robustness checks in the online appendix. These robustness checks include (1) a regression for each country in order to rule that effects are driven by a subset of countries, (2) estimates with adjusted p‐values in order to address the potential multiple comparisons problem using Benjamini and Hochberg's (Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995) method, (3) estimates for all models with party identification with the incumbent party as a control variable through various coding decision and (4) a test with a variable that captures having children at home between 25 and 34 compared to 18–34 as employed in the main analysis. All robustness checks produce similar results to those presented in the main analysis regarding the size of the coefficients as well their significance levels.

Conclusion

I examined a behaviour that is socially widespread but somewhat neglected by political scientists: the large and increasing number of young adults staying in the family home and its implications for the understanding of opinion formation. The analysis shows that both parents and working age children who cohabit hold more negative opinions on items largely used in the public opinion literature, such as the assessment of the economy and the government's performance. These results are consistent with various mechanisms studied in public opinion such as the influence of the surrounding economic context on opinions.

My findings are relevant for different actors. Policy‐makers should be conscious about the fate of young adults and their economic difficulties. While the youngest generations do not turn out in large numbers their parents do and based on my findings, the economic situation of their working age children may have an effect on their opinions towards the economy and satisfaction with the government's performance. Since opinions on policy performances might lead voters to reward or punish the incumbent, policy‐makers and candidates should keep an eye on this social trend that affects a large part of the electorate, that is parents and voting age children. More generally, this study calls attention to the consequences of a salient social trend that might be of an interest for social scientists, and more specifically scholars of political behaviour. Future research may fruitfully explore the implications of cohabitation identified in this study on vote choice, notably in favour of extreme parties or even for abstention. Failure to reach independence might foster a resentment among young adults with the potential to drive them to extreme parties.

Regarding the analysis, while the estimates appear to be robust, the study does not provide causal evidence of the mechanism at work. I have theoretically presented cohabitation as a causal factor but the evidence remains correlational. Future research should extend the analyses by means of a causal identification. Panel data would be an excellent way to go if appropriate measures are available.

Finally, this research note has implications for survey design and calls for the inclusion of additional questions regarding the living arrangements beyond the usual considerations such as being an owner or renter, or cohabitation with a partner. While housing crises in large cities, change in living arrangements due to Covid‐19 and unemployment rates are more likely to affect young adults, accounting for the cohabitation with parents might provide a better proxy in order to capture the more accurate economic situation of those young voters.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ruth Dassonneville for her comments and suggestions at each stage of the paper. I am also grateful to Vincent Arel‐Bundock, Semih Çakır, Jean‐François Daoust, Martin Vinæs Larsen and Dieter Stiers. The research reported here was supported by the FRQSC (grant: 292337). I also thank the editors of the EJPR and their three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. Full replication data and syntax are available in the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HVUU6X

Data Availability Statement

Full replication data and syntax are available in the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HVUU6X.

[Correction added on 7th of August 2023, after first online publication: Data availability statement has been added in this version.]

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure 1: Share of young adults living with their parents in Europe

Figure 1: Unemployment among two age groups: less than 25 and 25‐74 years old

Table 1: Descriptive statistics: number of respondents by country and year (full sample before restrictions)

Table 1: Descriptive statistics

Figure 1: Parents sample ‐ Correlation between the two dependent variables, that is the satisfaction with the economy and government's performance

Figure 2: Children sample ‐ Correlation between the two dependent variables, that is the satisfaction with the economy and government's performance

Table 1: Main results ‐ Children hypothesis ‐ DV: Economy

Table 1: Main results ‐ Children hypothesis ‐ DV: Government

Table 1: Main results ‐ Children hypothesis controlling for incumbent partisanship (Binary variable)

Table 1: Main results ‐ Children hypothesis controlling for incumbent partisanship (3 categories)

Table 1: Main results ‐ Parents hypothesis‐ Binary and categorical measures of cohabitation

Table 1: Main results ‐ Parents hypothesis controlling for incumbent partisanship (binary)

Table 1: Main results ‐ Parents hypothesis controlling for incumbent partisanship (Independents, Opposition, Incumbent partisan)

Figure 1: Effects of having children aged between 18 and 34 years old in the household on parents' level of satisfaction with the economy or government's performance.

Table 1: Parents hypothesis with an alternative cutoff regarding the explanatory variable

Table 1: Estimates of Cohabitation with parents per country with corrected p‐value ‐ Dependent variable: satisfaction with the economy

Table 1: Estimates of Cohabitation with parents per country with corrected p‐value ‐ Dependent variable: satisfaction with the government

Table 1: Parents hypothesis when controlling for parental role

Table 1: Parents hypothesis ‐ moderating effect of parental role