In December 2018, after decades of debate, the Canadian Parliament amended the Income Tax Act (ITA) to eliminate restrictions on the “political activities” of registered charities. Then, in January 2019, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) issued new guidance on ‘Public Policy Dialogue and Development Activities (PPDDAs)” by Canadian charities. The new CRA guidance states that:

A charity may engage in unlimited PPDDAs that further its stated charitable purpose(s), provided the charity never directly or indirectly supports or opposes a political party or candidate for public office… In other words, a charity is free to advocate for retaining, opposing, or changing any law, policy, or decision of government in furtherance of its stated charitable purpose (CRA, 2019).Footnote 2

From a legal perspective, the changes to the ITA and the CRA regulations mark a significant shift in state-civil society relations by allowing charities to freely engage in activities to influence public policy making, so long as those activities are nonpartisan and related to the charity's stated purpose. Until 2019, Canadian law had restricted charities from allocating more than 10 per cent of their annual revenue to what the CRA called “political activities”—involving any calls for public action with the goal of influencing government laws, regulations or policies.Footnote 3 Many charity sector leaders had claimed that the old CRA regulations, and especially their heightened enforcement from 2012 to 2015 under the Conservative government, had created a “chill effect” on policy engagement (Beeby, Reference Beeby2014; CCIC, 2016a; Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities, 2017; Lasby and Cordeaux, Reference Lasby and Cordeaux2016: 16–18). Implicit in these claims was the promise that more charities would engage more seriously in policy debates if the rules were relaxed.

However, five years after the legal changes, policy engagement by Canadian charities does not appear to have increased. Our data suggest that very few charities engaged seriously and consistently in federal policy processes before or after the 2018–2019 legal changes. Since the changes in law could reasonably be expected to result, at least eventually, in increased policy engagement, we have an intellectual puzzle: Why have Canadian charities not become more engaged with federal policy making, despite the new legal opportunities to do so?

Solving this puzzle, at least for charities in the international development sector, is one of the contributions of this article. We investigate this puzzle by drawing on comparative research on policy engagement by charities and using a constructivist interpretation of neo-institutionalism. In the article, we use the term “policy engagement” as a shorthand for the CRA's (2019) term “public policy dialogue and development activities.”

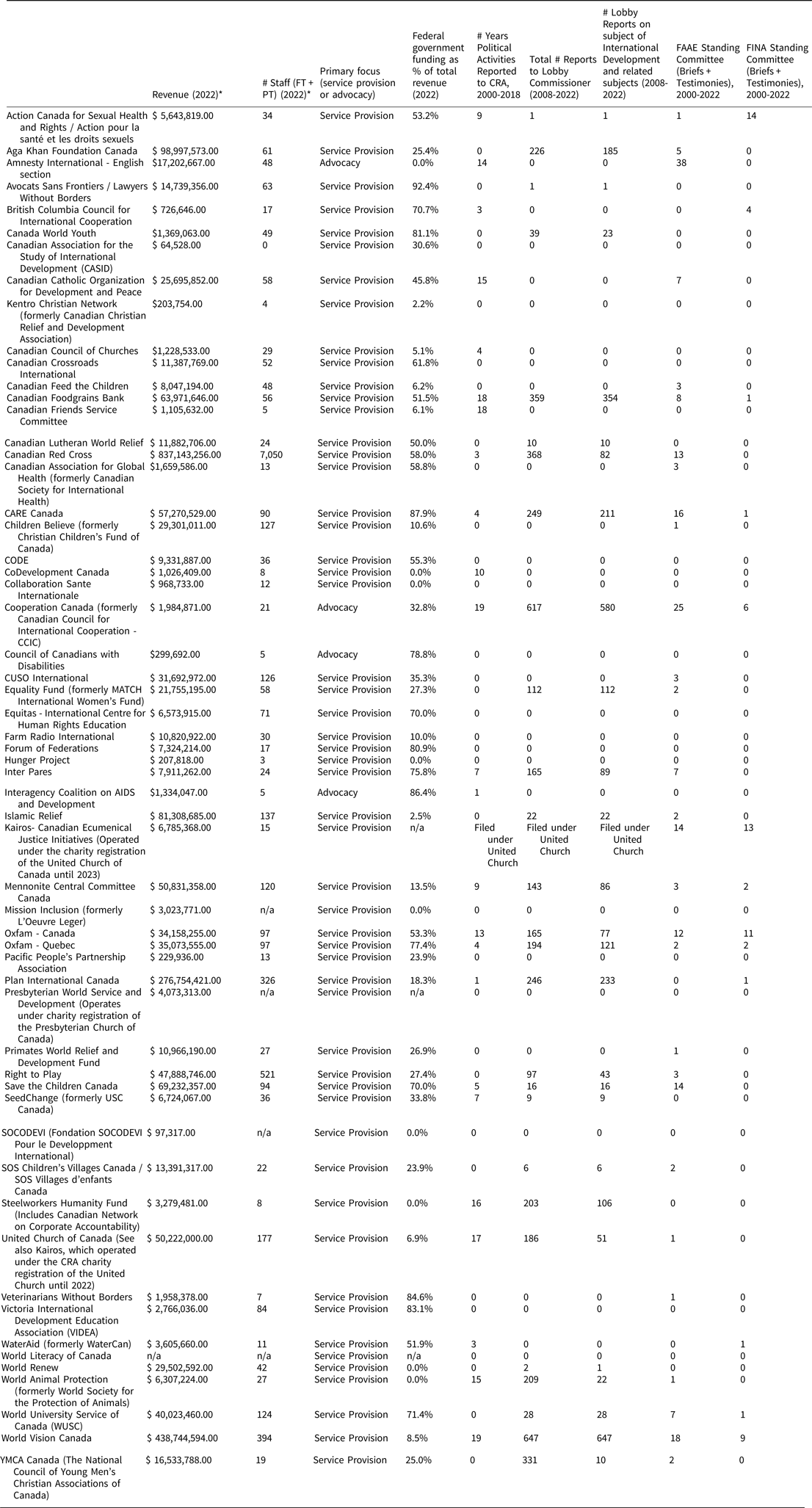

The article examines the context for federal policy engagement by all charities in Canada but focuses on charities in the international development sector and specifically the 58 charities that were members of the umbrella organization called Cooperation Canada as of 2018 (see Appendix 1). Charities in different sectors face different constraints and opportunities for policy engagement. The international development sector is an instructive case, if not representative of the full spectrum of charities in Canada, for several reasons. First, most of the large and medium-size organizations in the sector are registered charities, so charity law has an important impact on the operation of the sector. Second, the primary focus of almost all charities in the sector is service provision (see Appendix 1). Such organizations are more likely to have larger budgets than organizations focused primarily on policy engagement, which means that the CRA's 10 per cent cap on “political activities” was less of a constraint than for smaller organizations and those with a strong policy focus. Third, most charities in this sector expressed strong belief in the importance of public policy engagement but struggled to prioritize those beliefs in their operations.Footnote 4 Fourth, charities in the sector asserted that their engagement in public policy advocacy was constrained by the old CRA regulations. A 2016 report on a survey conducted by the Canadian Council for International Cooperation (now Cooperation Canada) stated that “current CRA rules … appear to limit the willingness of Canadian charities to undertake public policy work” (CCIC, 2016a: 14). Ninety-two per cent of the survey respondents indicated that the old CRA restriction on “political activities” “hinders their ability to realize their missions” (CCIC, 2016b: 23).

In this sense, the international development sector was a “most likely case” to study (see Flyvbjorg, Reference Flyvbjerg2011; Ruffa, Reference Ruffa, Franzese and Curini2020), as it appeared to be poised to increase its policy engagement following the changes in the ITA and CRA regulations—but that does not appear to have happened. The sector is also instructive because international development is primarily an area of federal jurisdiction, so policy engagement by charities in the sector focuses on the federal government and can be analysed through federal government data, a task that is more complicated for charities engaged with provincial and municipal policy issues for which data are more difficult to compare. Despite the particularities of the international development sector, our interviews with charity lawyers and leaders of organizations that support a wide range of Canadian charities suggest that many of the factors that we observed in the international development charities are also prevalent in other charitable sectors, bringing it close to the definition of a “typical” case (Gerring, Reference Gerring, Box-Steffensmeier, Brady and Collier2008; Seawright and Gerring, Reference Seawright and Gerring2008).

While controversies about the 2006–2015 Conservative government's enforcement of the CRA regulations contributed to widespread perceptions that the regulations themselves were the primary constraint, our research points to a wider range of factors that shape and constrain policy engagement by charities. First, charity leaders highlighted that it was not so much the regulations themselves as the politicized enforcement of the regulations in the last few years of the Harper government that generated fear and uncertainty in the sector about policy engagement. Moreover, that fear and uncertainty and the risk aversion that emerged from it persists within many charities, especially within boards of directors, reflecting socially constructed understandings of the law. Second, other factors that have little to do with the regulatory framework also shape policy engagement by charities in important ways, including the difficulties of finding resources to pay for public policy engagement, concerns about jeopardizing government funding and a strategic preference for insider advocacy—which was never restricted by the ITA or CRA regulations. The insider approach to policy advocacy focuses on building relationships with decision makers and quiet lobbying behind the scenes, in contrast to outsider approaches involving public campaigns and calls to action, which were regulated and restricted by the ITA and CRA regulations (see DeSantis and Mulé, Reference DeSantis and Mulé2017; Lang, Reference Lang2012; Sussman, Reference Sussman2007).

The article develops this argument in five parts. Section 1 highlights key debates in the comparative literature about public policy engagement by charities. Section 2 explains our methodology and data sources. Section 3 provides a short history of federal lawFootnote 5 on policy engagement by charities in Canada, the responses of charities to the law, and debates over whether and how the ITA and regulations should change. Section 4 presents our analysis of publicly available federal government data on policy engagement by charities. Section 5 explores the constraints on policy engagement in more detail, drawing primarily on interviews with charity leaders.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Whether and how charities engage with public policy is an important issue in any polity.Footnote 6 Charities play key roles in modern pluralist societies not only by providing social services but also by monitoring governments, holding them to account, providing policy advice and stimulating public deliberation on policy issues (Gibbons, Reference Gibbins2016; DeSantis and Mulé, Reference DeSantis and Mulé2017). Since charities often act as implementing agents for state policy, they have important experiential knowledge about what works and what does not and so can contribute to better policy outcomes.

Public controversies over the old CRA regulations on policy engagement (2003–2018), especially under the Harper government, generated significant analysis of the legal constraints on policy engagement by Canadian charities, in addition to the extensive earlier literature on the 1978 CRA regulations (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2018; Devlin, Reference Devlin2017; Drache, Reference Drache2002; Elson, Reference Elson2011; Hale, Reference Hale2017; McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt, Reference McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt2017; Monohan and Roth, Reference Monohan and Roth2000; Parachin, Reference Parachin2007, Reference Parachin2015, Reference Parachin2016, Reference Parachin2017a, Reference Parachin, Mulé and DeSantis2017b; Singer, Reference Singer2020; Watson, Reference Watson1985). This analysis, which we explore further in section 3, is extremely helpful for understanding the formal regulatory framework for policy engagement by charities, but little analysis has been published on how charities have responded to the 2018–2019 changes in the law (see Lorinc, Reference Lorinc2020). The other contribution of this article is thus to fill that empirical gap in the literature. Since our research findings indicate that the 2018–2019 legal changes did not spur an important increase in charities’ policy engagement, research is needed to better understand the broader factors that shape policy engagement by charities, including how charities understand and respond to the law.

A social constructivist approach to institutionalism highlights the ways that actors’ understandings of institutions—such as the regulatory framework composed of the ITA and associated CRA regulations—shape their behaviour. Classical versions of neo-institutionalism understood institutions as objective structures that shaped and constrained human action, “analogous to the rules of the game in a competitive team sport” (North, Reference North1990: 4). However, there has been considerable debate over the extent to which institutions should be understood objectively as fixed structures or as contingent social constructs, based on human understandings and perceptions.Footnote 7 In this article, we do not engage directly with these theoretical debates, but we do note that scholars on all sides of these debates agree at a basic level that how political agents understand their institutional environments is crucial to explaining their political behaviour. From this perspective, it is not the law itself that shapes and constrains the behaviour of charities, but rather how charities, their boards and managers understand (and frequently misunderstand) the ITA and the CRA regulations—including the ways that understandings based on previous versions of the law and their implementation under previous governments continue to shape charities’ behaviour into the present (see DeSantis and Mulé, Reference DeSantis and Mulé2017: 16–17; and Lasby and Courdeaux, Reference Lasby and Cordeaux2016). A social constructivist approach to institutionalism focused on charities’ understandings of the law may thus help to solve the apparent puzzle of why public policy engagement by charities does not appear to have changed following the 2018–2019 reforms of the ITA and CRA regulations.

However, while the regulatory framework and charity actors’ understanding of it are key parts of the context that shapes policy engagement by charities, comparative research highlights a wider range of factors beyond regulations that may also help to solve the apparent puzzle of policy engagement by charities. Much of the US research emphasizes the ways that resource constraints of money, staff time and expertise limit and shape policy engagement by charities and nonprofits. Serious and consistent policy work costs money—especially to pay for experienced and professional staff—and raising funds to cover those costs is challenging for many charities and nonprofits, frequently limiting their capacity to engage with policy issues (Bass et al., Reference Bass2007; Lu, 2018; Pekkanen, Smith and Tsujinaka, Reference Pekkanen, Smith and Tsujinaka2014; Salamon, Reference Salamon2002).

Within the research on resources for policy engagement, numerous studies examine the effects of government funding on decisions by charities about whether and how to engage in policy advocacy. The empirical evidence strongly indicates that receiving government funding is positively correlated with policy engagement, especially when that funding represents less than 50 per cent of a charity's revenue (Bass et al., Reference Bass2007; Kelleher and Yackee, Reference Kelleher and Yackee2009; Leroux and Goerdel, Reference Leroux and Goerdel2009; Lu, 2018; Mosley, Reference Mosley2011; Moulton and Eckerd, Reference Moulton and Eckerd2012; Neumayr et al., Reference Neumayr, Schneider and Meyer2013; O'Reagan and Oster, 2012; Salaman, Reference Salamon2002). Resource mobilization theory offers an explanation for this evidence, highlighting the costs involved in policy work and the ways that government funding contributes to the overall capacity of charities for policy engagement (McCarthy and Zald, Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins and Powell1987). Similarly, the “paradigm of partnership” highlights the ways that relationships with government funders can open pathways for charities to influence policy (Kelleher and Yackee, Reference Kelleher and Yackee2009; Salamon, Reference Salamon2002).

However, comparative research also indicates that government funding frequently softens the advocacy strategies of charities and nonprofits, “channelling” them towards less-confrontational forms of insider advocacy (Chewinski and Corrigall-Brown, Reference Chewinski and Corrigall-Brown2020; Clément, Reference Clément2017; Nicholson-Crotty, Reference Nicholson-Crotty2007) or what Onyx et al. referred to as “advocacy with gloves on” (Reference Onyx2010: 41). Mosley (Reference Mosley2012) found that public funding led charities to “reject confrontational methods and advocate as insiders” (Reference Mosley2012: 841) while Lu concluded that “nonprofits with more government funding use more insider strategies to achieve their advocacy goals” (Reference Lu2016: 9). Given the significant federal support for charities and nonprofits in Canada (Clément, Reference Clément2017), including in the international development sector (Smillie, Reference Smillie and Brown2012), it may be that government funding has channeled charities towards insider advocacy in ways that were (and continue to be) more powerful than the constraints on outsider advocacy contained in the CRA regulations.

The studies on the effects of government funding also highlight the strategic or tactical choices of charities about how to engage governments to promote policy change, particularly whether they adopt insider or outsider approaches to advocacy (DeSantis and Mulé, Reference DeSantis and Mulé2017; Lang, Reference Lang2012; Sussman, 2017). Government funding may be one factor that informs these strategic considerations, but there may be other factors as well, such as the risk appetite of boards of directors and organizational evaluations of the relative effectiveness of different tactical options.

In the research for this article, we drew on insights from social constructivist approaches to institutionalism and comparative research on policy engagement by charities by asking questions about the factors that shape Canadian charities’ decisions about policy engagement, including the ITA and CRA regulations and charities’ understandings of them, the challenges of raising funding for policy work, the effects of government funding on decisions about policy engagement and strategic approaches to policy change by the management and boards of charities.

Research Methods and Data Sources

To try to understand whether and how charities’ engagement with federal public policy issues changed following the 2018–2019 amendments to the ITA and CRA regulations, we conducted both quantitative and qualitative research. It bears emphasizing that efforts to measure policy engagement by charities with quantitative data require careful interpretation. There are no thorough, systematic or fully objective sources of data on policy engagement by charities in Canada. No single data source captures all the activities that charities understand as part of policy engagement, from policy research to closed-door meetings with officials to public campaigns. Research based on surveys of charities allows for in-depth questions and nuanced data but is typically limited by low response rates and a fixed point in time (see Lu, Reference Lu2016: table 1). For this reason, we examine publicly available federal government data, which include much larger response rates and can be measured over time but lack the more nuanced questions that survey research allows.

Based on conversations with charity leaders, we identified three sources of federal government data that provide insight into policy engagement by charities: 1) the CRA data on “political activities” for charities; 2) lobbying reports from the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada; 3) data on the submission of briefs and witness testimony for two Parliamentary Committees. Below we explain each source in turn.

From 2003 to 2018, CRA regulations required registered charities to self-report on “political activities” in the annual T3010 information return. The data included whether the charity engaged in any “political activities” and how much money it spent on those activities. In response to our information request (submitted on January 11, 2022), CRA provided data from all T3010 returns for the period 2003 through 2018, representing about 75,000 registered charities per year.Footnote 8 When the restrictions on “political activities” were abolished in 2019, CRA also stopped collecting data on them, making it impossible to track changes in self-reported “political activities” through CRA data after 2018. The pre-2018 data, however, still provide a useful baseline indicator of charities’ engagement in outsider forms of policy advocacy.

Lobbying was never restricted by the CRA but lobbying data from the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying do provide an indication of insider policy engagement by charities. Federal law requires any individual or private entity who lobbies a federal public office holder regarding possible changes in any federal policy, law or decision to register as a lobbyist and to register each lobbying visit. The data, published on the website of the Office of the Lobbying CommissionerFootnote 9, include the name of the lobbyist and the person or entity being lobbied, the subject matter of the meeting and the date of the meeting.

The House of Commons Standing Committees represent an important opportunity to engage with Members of Parliament on policy issues, despite the contradictions generated by party discipline (Franks, Reference Franks1971; Skogstad, Reference Skogstad1985). Data on who presented to what committee and when are available on the Parliamentary websiteFootnote 10. We examined the lists of all organizations that submitted briefs and witness testimony to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development (FAAE) and to the annual Pre-Budget Consultations of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance (FINA) over the period 2000–2022. We chose the FAAE and FINA, since these are the parliamentary committees of most relevance to the international development sector.

It is important to recognize that these federal datasets are marked by misreporting, under-reporting, over-reporting and by different understandings of the law (see Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2012; Lasby and Courdeaux, Reference Lasby and Cordeaux2016). Charities’ understandings of the regulations for policy engagement and their risk appetites may have also changed over time; so, apparent temporal patterns may indicate changes in reporting rather than actual increases or decreases in policy engagement. It is also important to highlight that the federal government data do not capture important forms of policy engagement that were not restricted by the 2003–2018 CRA regulations, especially outward facing advocacy such as the publication of policy research, public education, blogs and op-eds that did not involve public calls to action. Because of the limitations of the data, we do not attempt statistical analysis beyond basic description. We use the three sets of federal data as overlapping radar screens to identify which charities have been engaged in federal policy processes at all. We posit that charities that have been seriously and consistently engaged in efforts to influence federal policy will show up in at least some of the data sources, some of the time. Taken together, these three federal datasets will provide important insights into the overall level of policy engagement by charities, and of the identities of those most involved.

To address limitations in the quantitative data and to gain other insights as well, we conducted 90 semi-structured qualitative interviews with relevant staff (for example, those responsible for policy engagement, senior managers) and board members from 56 Canadian charities, primarily in the international development sector. We conducted 79 of those interviews in English and 11 in French, 58 before the legal changes in 2018–2019 and 32 afterwards. We also interviewed four prominent charity lawyers and four leaders of organizations that support policy work across the entire charitable sector following the 2018–2019 legal changes. We then coded interview transcriptions using a priori and inductive approaches to identify key themes (Azungah, Reference Azungah2018).

The “Long Freeze” on Policy Engagement by Charities

Controversy about the regulatory constraints on policy engagement by charities made headlines when the Conservative government of Stephen Harper announced additional funding to the CRA in the 2012 federal budget to conduct special audits on the so-called “political activities” of Canadian charities.Footnote 11 Evidence suggested that the CRA's audits of “political activities” targeted charities with policy positions that challenged the Harper government, particularly in the environmental, international development, antipoverty and human rights sectors (International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group, 2021). The result of the special audits, conducted between 2012 and 2015, combined with direct threats (Clark, Reference Clark2010) and cuts in funding to charities that had been seen as being opposed to the Conservative government's policies, such as Kairos, North-South Institute and CCIC, was a “chill” on policy engagement by charities—even within the bounds of the CRA regulations (Kirkby, Reference Kirkby2014; Beeby, Reference Beeby2014). As numerous charity leaders lamented, “advocacy” became a dirty word and came to be perceived as a risky activity (DeSantis and Mulé, Reference DeSantis and Mulé2017; Byrnes and Palassio, Reference Byrnes and Palassio2022).

However, the advocacy chill of the 2010s marked only a slight drop in temperature within what can be understood as a “long freeze” on policy engagement by charities that profoundly shaped their institutional design, organizational culture, staff capacity and strategic decision-making (Byrnes and Palassio, Reference Byrnes and Palassio2022). The history of the aversion to policy engagement by charities in Canada is partly rooted in the CRA's regulation of charitable and political “purposes,” which in turn is based in common law. Based on the 1891 Pemsel case in the UK House of Lords and subsequent case law, which in turn draws on the 1601 Statute of Charitable Uses, the CRA recognizes four “purposes” for charities: 1) the relief of poverty; 2) the advancement of education; 3) the advancement of religion; and 4) other purposes beneficial to the community (CRA, 2013; Pemsel Case Foundation, 2021). Notably, influencing policy is not a recognized charitable purpose in common law and for many decades, the Canadian parliament and courts did not consider policy engagement to be an allowable “activity” for charities, even to achieve recognized charitable “purposes.”Footnote 12 For example, regulations put in place in 1978 under the then Liberal government allowed charities to engage in quiet lobbying but prohibited virtually all activities to engage the public with government policy, including “writing letters to the editor,” “holding a demonstration,” “lobbying government through an organized campaign,” and “conducting a campaign where people send form letters to their elected representatives” (Department of National Revenue, 1978; Singer, Reference Singer2020: 688–90). For over two decades (1978–2003), Canadian charities were created, operated and evolved within a regulatory framework that specifically discouraged policy engagement. The boards of directors and management of Canadian charities generally adopted cautious approaches to public policy engagement and very few charities developed strong capacities for policy analysis and influence (see Carter et al., Reference Carter, Plewes and Echenberg2005).

The “long freeze” on policy engagement by Canadian charities and calls for legal reform are well-documented in public statements by charity sector leaders, lawyers, judges, members of parliament and multiple rounds of federal commissions and reports, including the National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action (1977), the Panel on Accountability and Governance in the Voluntary Sector (1999), the Voluntary Sector Initiative (2002), and the Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities (2017) (see also Elson, Reference Elson2011; Drache, Reference Drache2002; Laforest, Reference Laforest2013; Levasseur, Reference Levasseur2012; Monohan and Roth, Reference Monohan and Roth2000; Parachin, Reference Parachin, Mulé and DeSantis2017b; Watson, Reference Watson1985). Summarizing the long debate over the regulation of policy engagement by charities, Elson (Reference Elson2011: 62) highlights the “eerily familiar” repetition of calls to modernize the definition of charity in Canada and to relax or eliminate the regulatory restrictions on policy engagement. As the federally-appointed Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities asserted in its 2017 report, “problems with the legislative framework and its administration have left the [charitable] sector and its regulators stuck on a merry-go-round of consultation, clarification, and concern for nearly four decades” (Consultation Panel, 2017: 10).

Following several public controversies and debates in Parliament in the 1980s and 1990s, the CRA introduced a “Policy Statement on Political Activities” in 2003 (CRA, 2003). The guidance recognized the value of policy engagement by charities (section 3, paragraph 5), but simultaneously restricted it. Partisan activities were still prohibited (CRA, 2003: section 6.1). However, the guidance also distinguished between so-called “political” and “charitable” forms of policy engagement. It allowed charities to engage in limited “political activities” provided that they were related to the charity's officially stated purposes, and that “substantially all” of the charity's resources were directed towards “charitable activities” (that is, not “political activities”). The CRA interpreted the term “substantially all” to mean 90 per cent,Footnote 13 thus allowing charities to allocate up to 10 per cent of their annual revenue to “political activities,” a regulation that became known informally as “the ten percent rule.”Footnote 14 The CRA defined an activity as “political” if it “explicitly communicate[d] a call to political action (that is, encourage[d] the public to contact an elected representative or public official and urge(d) them to retain, oppose, or change the law, policy, or decision of any level of government in Canada or a foreign country)” (CRA, 2003: section 6.2). Behind-the-scenes lobbying for policy change and public campaigns to raise awareness of policy issues were considered charitable, and therefore unrestricted, as long as they did not involve a public call to action to change a law, policy or decision. The definition of “political activity” as a nonpartisan public call to action is significant because it explicitly discouraged efforts to engage citizens in policy debates and implicitly encouraged behind-the-scenes insider forms of policy engagement, an issue we return to below.

In principle, the 2003 CRA guidance on “political activities” opened opportunities for policy engagement by charities. Public campaigns to change government laws and policies were simply limited to 10 per cent of a charity's annual revenue, with higher allowances for smaller charities and the option to average expenditures on “political activities” over three years.

Public concern about the advocacy chill under the 2006–2015 Conservative government was powerful enough that the Liberal Party proposed to end it in its 2015 election platform (Liberal Party of Canada, 2015: 33–34). After the election, the prime minister's mandate letters to the ministers of National Revenue and of Finance explicitly called for them to end the “political harassment” of charities and to clarify “the rules governing ‘political activity,’ with an understanding that charities make an important contribution to public debate and public policy” (Trudeau, Reference Trudeau2015). The Liberal government eventually terminated the CRA's “political activities” audit program in 2017 (Beeby, Reference Beeby2017). In 2016, the government instructed the CRA to establish the “Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities,” which conducted hearings across the country and released a report in 2017 calling for the removal of all restrictions on nonpartisan public policy activities (Consultation Panel, 2017). The report of the consultation panel highlighted the “remarkable consisten[cy]” in responses from charities and emphasized the “strong message” that a “lack of clarity, whether with the rules or their application, means some charities view political activities as too risky to carry out and engage in self-censorship . . . many charities make a rational choice to avoid or limit the risk” (Consultation Panel, 2017: 12). The government was then forced to act even more quickly when the Ontario Superior Court of Justice (2018) ruled that the CRA regulations on “political activities” were unconstitutional, since they violated the right to freedom of speech. In December 2018, Parliament amended the ITA to remove references to “political activities” by charities, and in January 2019, the CRA issued new policy guidance (CG-027) for unlimited nonpartisan “public policy dialogue and development activities” by charities (CRA, 2019).

Quantitative Data on Policy Engagement by Charities

When we overlap the quantitative data from the three federal data sources, they tell a consistent story: very few Canadian charities engage seriously and consistently with public policy, and there is no evidence that the 2018–2019 changes to the ITA and CRA regulations prompted any significant change in policy engagement by charities in the international development sector.

With over 85,000 registered charities in Canada, the volume of data over 20 years is too large to include here, and so we provide it as supplementary data on the journal website. Here we summarize the highlights.

Canada Revenue Agency data on “political activities”

The CRA data on self-reported “political activities” by registered charities show that very few charities ever reported “political activities” and the amounts of expenditure that they reported were small (see supplementary data, tab 1). Of roughly 75,000 registered charities, an average of just 419 per year (0.57%) ever reported any “political activities.” Of the charities that did so, spending on “political activities” represented 0.91 per cent of total revenue, a proportion that declined over time, especially after 2010. Mean spending on “political activities” by the charities that reported them was $6,514 per annum.Footnote 15

Reported spending on “political activities” by Cooperation Canada member charities was higher than the charitable sector as a whole, but still relatively small and limited to a small group. Of the 58 registered charities that were members of Cooperation Canada in 2018, a maximum of 24 (in 2015 and 2016) ever reported any “political activities,” but only a smaller group of 15 charities consistently reported spending more than $10,000 per year. Spending on “political activities” by the Cooperation Canada charities that reported them averaged 1.36 per cent of total annual revenues over the period 2003–2018, nowhere near the 10 per cent cap. Moreover, many of the managers of international development charities that reported spending on “political activities” indicated in interviews that they did so out of an abundance of caution and included spending on policy activities outside the CRA's definition of “political activities.” So, the number of international development charities that used public calls to action in their efforts to influence federal policy between 2003 to 2018 was likely even smaller than the CRA data indicate.

Lobbying reports submitted to the office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada

The data on lobbying activity by international development charities paint a similar picture to the CRA data. Between 2008 and 2022, 25 of the 58 Cooperation Canada charities submitted one or more lobby reports, with a maximum number of 24 organizations reporting in 2022. Of those, a smaller group of 15 charities submitted lobby reports on a regular basis (an average of more than one per month).

The number of reports submitted by Cooperation Canada member charities increased slightly (4.7%) in the three years following the change in the ITA and the CRA regulations (2019–2021) compared with the three years before the change (2016–2018), while the number of Cooperation Canada charities that submitted lobby reports increased from 17 in 2016 to 22 in 2021. However, as we discuss further below, the leaders and staff of international development charities did not indicate in our interviews any increases in policy engagement over that time period. So the data from the lobbying commissioner may indicate increased rates of reporting rather than increased policy engagement; they may also indicate increased rates of lobbying for funding in the early years of the new Liberal government, which was widely seen as more supportive of the sector than the previous Conservative government.

House of Commons standing committees

Between 2000 and 2022, over 15 sessions of Parliament, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development invited a total of 2,962 witnesses and received 464 written briefs. Of those, 196 witnesses (6.6%) and 31 briefs (6.6%) were from 28 charities belonging to Cooperation Canada. However, just 8 Cooperation Canada member charities engaged with the FAAE ten times or more, while another 8 engaged only once or twice over the 23-year period.

Between 2000 and 2022 the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance produced 16 pre-budget consultation reports, involving a total of 4,680 witnesses and 6,833 briefs. Of those, 25 witnesses (0.53%) and 52 briefs (0.8%) were from 17 Cooperation Canada charities. Only 3 Cooperation Canada charities engaged with FINA ten times or more, while 9 engaged only once or twice over the 22-year period. With few exceptions, these are the same charities that appear in the data from CRA and the Lobbying Commission. The pattern of engagement with the 2 standing committees did not change significantly after 2018: 7 charities did submit briefs to FINA for the first time after 2019, although 5 of the 7 did so only once and none were invited to testify. Only 1 charity engaged with the FAAE after 2019 that had not done so before, while 11 charities that had submitted briefs or testified to the FAAE before 2019 did not do so between 2019 and 2022.

Explaining Policy Engagement by Canadian Charities

The quantitative data from federal sources on policy engagement by charities point to three basic observations: 1) relatively few charities have consistently engaged with federal policy issues; 2) the charities that have engaged with policy spend proportionately few resources on it; and 3) there is very little evidence of any change in policy engagement following the 2018–2019 changes to the ITA and CRA regulations—either in the number of charities or the frequency of their engagement. In this section, we explore factors that might explain the apparent lack of change in policy engagement by charities after 2018–2019, based primarily on our qualitative interviews.

Charity leaders in the international development sector whom we interviewed asserted almost universally that the change in regulations “did not make any difference” for decisions by their organizations about whether, how or how much to engage with federal policy issues (Respondent 81, 2023). They explained that, as organizations with relatively large budgets and a focus on service provision, expenditures on “political activities” were “never anywhere near ten percent” (Respondent 65, 2022). One policy director indicated that “even with a big campaign every year and two full time staff salaries, we still don't get anywhere near the ten percent threshold” (Respondent 15, 2016).

Nevertheless, charity leaders did emphasize that they appreciated the change in the ITA and the CRA regulations, partly because the new regulations removed the “annoying and time consuming” reporting requirements (Respondent 67, 2022) and partly because they removed “fear and uncertainty” and “feelings of being watched by the CRA” (Respondent 71, 2022). Some respondents complained that the 2003–2018 CRA guidelines were “vague and confusing” (Respondent 43, 2016), which discouraged many smaller charities from engaging with policy issues because they could not afford legal advice or dedicate staff time to overcoming the confusion. At the same time, charities with a strong commitment to policy engagement reported that, despite the confusing guidelines, “we figured out how to work within the rules” (Respondent 37, 2016).

The party in power and the politicization of CRA regulations

Rather than the CRA regulations themselves, charity leaders considered the politicization of the regulations by the Harper Conservatives to be a much more important constraint on policy engagement, especially between 2012 and 2015. As one policy director put it, “the CRA audits under Harper were targeted, deliberate and politically motivated” (Respondent 38, 2016). Another asserted, “The Income Tax law itself is not the problem, but its application… it's the harassment and political targeting of charities that was the problem” (Respondent 7, 2016). Charities that were audited by the CRA emphasized “traumatizing transaction costs” (Respondent 29, 2016). As one former executive director explained, “the (CRA) audit went on forever, they wanted to access everything, transcripts of public talks, speaking notes, everything, it was nuts! It was incredibly time consuming, huge staff energy and most of it fell on me” (Respondent 84, 2024). Stories of CRA audits spread quickly through the charity sector and generated widespread fear of the audits themselves and of the even greater risk of losing charitable status and the associated fundraising capacity.

Major cuts in government funding to prominent international development charities that had been seen as being opposed to the Conservative government's policies, such as CCIC, Kairos and the North-South Institute, further heightened the sense of fear and subsequent “chill” on policy engagement (Beeby, Reference Beeby2014). One seasoned policy advocate explained the widespread perception that “if you spoke up, you were cut off. Eventually, people started silencing themselves” (Respondent 46, 2017). Another reported that “discussions [about policy engagement] within my organization and the international development sector were characterized by panic and fear” (Respondent 19, 2016). Other charity leaders highlighted the practical effects of the “chill” on policy engagement: “it made you hesitant to speak out in public” (Respondent 25, 2016); “You could feel the chill, it was palpable, nobody even wanted to write public letters or op-eds” (Respondent 84, 2024). A government relations director from a large charity reported that “our board didn't even want us to do a pre-budget submission [to the Standing Committee on Finance] or other totally legitimate policy activities that were not even restricted by the CRA” (Respondent 27, 2016). The leader of another policy team explained that “the perception of risk [about policy engagement] by the board emerged at a percentage point well below ten percent” (Respondent 31, 2016), suggesting again that the 10 per cent rule itself was not a constraint but rather perceptions of its politicized application by the Harper government. In the context of those perceptions, any uncertainty or confusion about the CRA rules contributed to risk aversion: “sometimes we'd forget what was allowed and perfectly legitimate. The chill created doubt and restraint on our part about what messages to send” (Respondent 19, 2016).

Unprompted by our interview questions, many charity leaders said that the change in tone of the new Liberal government starting in 2015 was more important than the change in CRA regulations. One policy officer explained, “the [Liberal] government perceives the role of civil society very differently. They actually call us to ask what we think” (Respondent 1, 2016). Others emphasized that “our access to the government opened up” (Respondent 64, 2022), and “the stress of cuts, the advocacy chill was lifted” (Respondent 45, 2017). Charity leaders suggested that the attitude of the government in power may be a more important factor in determining policy engagement than the law itself.

The greater openness to policy engagement by charities under the Liberal government prompted some organizations to invest new resources and hire new staff for policy research and advocacy, but few reported any significant changes in the strategies they used to try to influence policy making. Most notably, charity leaders indicated a strong ongoing preference for insider strategies, and none reported that they had increased “public calls to action” despite the 2018–2019 changes to the ITA and the CRA regulations. As one executive director explained, “the [Liberal] government has generally been good for this sector . . . they've supported us, so I don't want to spit in the soup . . . When you have a friend, it means that sometimes you have to talk the real talk and say ‘Look, I'm not happy with this’, but it's a soft-spoken advocacy toward the current government” (Respondent 82, 2023).

However, charity leaders also revealed some deep and persistent legacies of the “chill” on public policy engagement, even eight years after the change in government and five years after the change in the law. As one executive director explained, “Many charities lost their capacity for advocacy. Advocacy units were shut down or downsized and staff were redeployed. It takes longer for organizations to re-build, to hire new staff, to develop new strategic plans. Those ten years [of Conservative government] were corrosive and hollowed out the capacity for advocacy in many charities” (Respondent 52, 2018). While some organizations have managed to hire new staff for policy research and advocacy, feelings of uncertainty, fear and risk aversion about policy engagement persist throughout the sector—highlighting the insights from constructivist institutionalism that what matters is not simply the regulations but also how they are understood. Staff from charities with active histories of policy engagement reported that within their own organizations “there is still a level of alarm when the word ‘advocacy’ is used” (Respondent 75, 2023) and “the fear is so ingrained that it [advocacy] still feels a little risky” (Respondent 70, 2022). Another explained that risk aversion to policy engagement “still continues like a cloud over civil society. It [policy engagement] is like a muscle we haven't used yet . . . there's still fears around it” (Respondent 68, 2022).

Mistrust and fear of the CRA

Charity leaders indicated that their fear is partly grounded in an ongoing mistrust of the CRA that is pervasive across the charitable sector (see Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector, 2021). Some policy directors indicated that they did not feel that the 2019 CRA regulations had yet been seriously tested and they were still waiting to see how the CRA and the rest of the federal government will respond to charities that engage aggressively in public calls to action for policy change. One executive director explained, “being first over the trench is scary” (Respondent 76, 2023). The charity lawyers we interviewed explained that, despite the change in the law, charities still have good reasons to fear the CRA—in particular, the onerous transaction costs and reputational damage incurred through CRA audits (see Carter, Reference Carter2015) and the high cost of appealing CRA decisions (see Chan, Reference Chan2016; Juneau, Reference Juneau2016: 2; Senate of Canada, 2019: 69–73). The absence of an affordable process for appealing CRA decisions led one charity lawyer to describe the CRA as “beyond the rule of law” (Respondent 74, 2023). In the context of legal advice that still often views policy engagement as a risk, many charities continue to avoid any activities they think might attract the CRA's attention.

Charity leaders were also concerned that future federal governments might re-politicize the CRA audit process, either by reintroducing legal restrictions on policy engagement or by “weaponizing” the CRA's complaint mechanisms and audit power to punish outspoken charities and to frighten others into silence (Respondent 80, 2023). In this context, some respondents reported that their organizations remain wary of investing energy and resources to expand their policy engagement, even if they had the money to do so.

Nonregulatory constraints on policy engagement

Our interviews with charity leaders also suggest that decisions about whether, how and how much charities engage in policy debates are heavily shaped by a combination of organizational culture, leadership, strategic considerations and funding—reinforcing findings from comparative research, albeit with some important nuances. For most of the charities we interviewed, these nonregulatory factors did not change after 2018–2019, thus offering insights into the lack of changes in policy engagement.

Organizational culture as a constraint on policy engagement

Senior managers highlighted multiple factors that draw their attention and support away from policy engagement. Those factors included the tension between the long-term and uncertain results of policy engagement and the organizational focus on short-term results fostered by the results-based management frameworks required by governments and philanthropic donors (Respondent 35, 2016). The director of one charity explained, “The metrics that [senior managers] are judged on are deliverables, impacts and outcomes . . . which doesn't lend itself to long-term thinking about advocacy for system change” (Respondent 53, 2018). Another executive director highlighted the ways that the constant demands of program management and fundraising distracted his attention from policy engagement: “you're distracted, you're focused on those other things, program implementation and funding” (Respondent 73, 2022). Reinforcing social constructivist approaches to institutionalism, many policy directors also emphasized misunderstandings by board members about CRA regulations as a constraint on policy engagement. As one explained, “Boards have the sense that the rules don't allow ‘political activities’ at all so they won't even try. They don't take risks” (Respondent 53, 2018).

Several executive directors and policy directors emphasized that for charities to engage with policy, their leaders must actively prioritize and nurture it. As one director put it, “if you want to do effective public policy advocacy, you must staff it and you must resource it . . . that helps to create an internal culture, an identity as an organization that does public policy advocacy. It's not just a question of the resources but also the identity that this is something that you do and it's resourced, it's part of your priorities as an organization” (Respondent 64, 2022). Another director spoke with praise about the principled commitment of another charity that “made really clear, strategic decisions to build a policy team instead of spending unrestricted money on fundraising campaigns” (Respondent 71, 2022). Many policy directors also emphasized their ongoing work to “advocate for advocacy” within their own organizations and the need to regularly remind their directors and boards of the value and positive results of policy work (Respondent 75, 2023). One policy director explained that “I had to do a lot of internal advocacy to get policy advocacy into the strategic plan” (Respondent 78, 2023). Another explained that “a big part of my job is to convince [the executive director] and the board that policy work generates results and does not pose a risk to our funding” (Respondent 65, 2022). Both before and after the 2018–2019 changes to the ITA and the CRA regulations, interviewees gave similar accounts of how organizational culture affected their organization's approach to policy engagement.

Strategic constraints and an ongoing preference for insider advocacy

Within the charities with at least some policy engagement, policy staff were adamant that decisions about how to influence government policy—and especially whether to use insider or outsider approaches—were driven primarily by strategic considerations about what types of engagement are likely to be most effective. Again, this finding came out in interviews before and after the 2018–2019 legal changes. As one seasoned policy director put it, “the only constraints are strategic” (Respondent 10, 2016). Many respondents emphasized their efforts to “use our budget and resources as strategically as possible” (Respondent 79, 2023) and “on topics that have the most chance of getting somewhere” (Respondent 13, 2016). Policy leaders also concurred on the “need to pick a few issues and really push those few” (Respondent 68, 2022) and to focus on winnable fights. As the policy director for a charity with a relatively large budget for policy engagement explained, “We don't advocate on hopeless issues. We would be wasting valuable political capital to push for issues the government is not interested in. We focus only on issues on which we have a chance of success” (Respondent 31, 2016). A government relations consultant pointed to the importance of tackling “low hanging fruit to help ensure the success needed to maintain board enthusiasm [for policy engagement]” (Respondent 44, 2016). Similarly, a policy director explained the ways that prevailing results-based management frameworks push charities towards short-term, winnable policy issues: “An advocacy campaign built around an idealistic stand won't enable you to report on the results the way that [our management framework] requires” (Respondent 34, 2016). However, the same policy director also recognized the trade-offs of “a focus only on what you can win rather than what is important.”

Both before and after the 2018–2019 changes in the law, almost all the charity leaders we interviewed expressed a strong strategic preference for insider approaches to policy engagement. It is important to highlight that the CRA restrictions on “political activities” from 2003–2018 applied only to outsider forms of policy engagement involving a public “call to political action” (CRA, 2003: section 6.2). Insider forms of advocacy such as lobbying and public engagement that did not involve a public call to political action were not restricted. The widespread strategic preference of charity leaders for insider advocacy thus helps to explain why the 2018–2019 changes in the ITA and CRA regulations has had little apparent effect on policy engagement by charities.

Policy directors explained that they preferred insider approaches both because they typically require less time and resources than public campaigns and because they contribute to building relationships of trust with decision makers, which they considered to be essential for long-term policy influence. Some charities indicated that if insider approaches failed, they would try other, more aggressive, public-facing tactics. As a policy director for one of the more activist charities explained, “We always try the insider track first. If we're getting there with the insider track, and the government comes through with our priorities, we're happy to leave it at that. But if it doesn't happen, then we try something different” (Respondent 70, 2022). Another said, “You always try to get what you want through the back channels first, without embarrassing someone” (Respondent 53, 2016).

However, the policy directors for many charities explained that they exclusively use insider approaches focused on relationship building and never engage in campaigns involving public calls to action. As the policy lead for a large coalition organization explained,

Our advocacy approach is very much a relationship-based approach. It's behind the scenes, direct advocacy with those who we assess to be key decision makers on whatever issue we're trying to push forward . . . we're not a campaign style organization. It's not that we are never critical, but we never threaten, we never seek to embarrass. We're more apt to try to find mutual win-win solutions. (Respondent 83, 2023)

The policy director for a large charity similarly emphasized, “we don't come out to criticize, it's not our style. We do things behind the scenes. We build long-term relationships with people in government” (Respondent 13, 2016). Policy directors also explained the importance of “collaborative, solutions-focused” approaches to policy engagement as essential for building trusting relationships with government decision makers (Respondent 78, 2023). This approach involves “being a helpful partner to government” (Respondent 38, 2016) and “propositional, not oppositional” (Respondent 31, 2016). A seasoned government relations consultant emphasized the importance of making proposals that government decision makers “can say yes to” (Respondent 76, 2023). Another policy director similarly explained, “good advocacy requires engagement with governments that want praise and recognition for their work” (Respondent 10, 2016).

While most of our respondents claimed to respect outsider forms of policy engagement by other organizations, they did not consider outsider approaches to be appropriate strategies for their own organizations. One explained, “I don't think that putting the government on blast and telling them all of the things they're doing wrong is going to get you where you want to go” (Respondent 83, 2023). Another asserted, “I don't believe that raising your fist in the air really effects change. Rather, advocacy is about being really smart about using media at the same time as pressuring on the inside. At some point, everybody has to win, including the decision makers you are lobbying” (Respondent 46, 2017).

Only two of the charities we interviewed rejected the insider approach to policy engagement. Interestingly, even these charities acknowledged that they considered insider advocacy to be more effective for achieving specific policy goals. As one put it, “closed door advocacy is often more productive, takes things further” (Respondent 50, 2018). Their rejection of insider approaches was principled rather than strategic, based on “strong lines of accountability to partner organizations in the global South” (Respondent 29, 2016) and “a conscious choice to engage citizens in the policy process” (Respondent 50, 2018). As Respondent 29 questioned “if you're only doing the inside strategy, what happens to public engagement, to public education, to movement building?” (Respondent 29, 2016). The director of the other charity explained her organization's principled commitment to citizen engagement in policy change: “Policy interventions without public engagement may shift policy, but they don't shift power. We're aiming for more than just technical policy changes” (Respondent 35, 2016). She went on to explain her organization's rejection of insider advocacy:

Instead of analyzing the situation and saying, “this is what we want”, there's a shift to asking, “in this political context, what can we realistically achieve?” It's a shift from the clear and principled to the tactical and strategic. People constrain their thinking to the political context and don't ever think big picture, they focus only on what they think they can get in this political moment. We thus confuse the winnable achievement with what we really want. (Respondent 35, 2016)

Difficulties of engaging Canadians with public policy

While some policy directors at charities that prioritized insider approaches sympathized with concerns about the lack of citizen engagement and movement building, they also highlighted the difficulties of engaging Canadians in campaigns to change public policy, particularly on global issues. Again, the findings from interviews were virtually the same before and after the 2018–2019 changes to the law. Policy staff from a wide range of organizations echoed the assertion that “Canadians are generally reluctant to act politically” (Respondent 11, 2016) and “would rather write cheques than a letter to their MP” (Respondent 34, 2016). Seasoned policy advocates asserted that outsider campaigns on international development issues typically generate little public interest: “You get very little uptake. It's a small cast of characters” (Respondent 40, 2016). Policy leaders from two organizations with large member-donor bases indicated that only 1 to 5 per cent of their regular donors could be engaged in public policy campaigns (Respondents 7 and 13, 2016). As one put it, “it's a real, real challenge to move people beyond charity” (Respondent 13, 2016). The policy lead for another charity lamented that “our organization just doesn't have the resources to move the needle on public opinion” (Respondent 83, 2023). In the context of the perceived challenges of engaging Canadians in efforts to change public policy, all but a few charities with deep, principled commitments to citizen engagement asserted that insider approaches to policy change were a better use of their limited resources.

Receipt of federal funding as a constraint on policy engagement

At the same time, many charity leaders also acknowledged that the receipt of federal funding made them more careful about policy engagement. Echoing the findings from quantitative research in the United States and channelling theory, our interviewees were adamant that reliance on government funding did not stop them from policy engagement but did lead them towards insider approaches and greater caution with outsider approaches, under both Conservative and Liberal governments. Once more, the interview data on this question did not vary much from the pre to post 2018–2019 period. As one policy director explained, “we do receive quite a lot of money from the government and so we always have to calculate how much risk we want to take” (Respondent 70, 2022). At the same time, there is a widespread perception within the sector that the more radical organizations do not receive government funding and so are not constrained by it. As the policy director from an organization with relatively little federal funding explained, “we don't have big programs with [Global Affairs Canada] . . . so we really don't care if we upset the government because there is little risk. It allows for a more outsider, confrontational approach” (Respondent 50, 2018).

Three points about the relationships between government funding and policy engagement bear emphasizing, however. First, almost all of the charities we interviewed received at least some federal funding (see appendix 1). Second, our interviews and the quantitative data indicate that almost all of the charities that received federal funding also engaged with federal policy issues in at least some fashion. And third, there is no obvious evidence that the absence of government funding leads organizations to be more engaged or more outspoken on policy issues. Indeed, some of the more engaged and more critical international development charities have long histories of significant government funding (such as Inter Pares and the two Oxfams), while some organizations with very little or no government funding (such as Kentro Christian Network) have been largely disengaged from public policy debates. Our interviewees both before and after the 2018–2019 changes attributed these variations to organizational missions, culture and leadership within charities and insisted there is no direct relationship between government funding and avoidance of policy engagement. In a separate project, analysis of CRA data for all Canadian charities between 2003 and 2018 pointed to a similar conclusion: Charities without government funding were no more likely to engage in political activities than charities with government funding, even when it represented more than 50 per cent of their revenue (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Dicks and Swiss2024).

Funding constraints on policy engagement

Charity leaders highlighted the availability of funding for policy engagement as a major constraint that existed before the 2018–2019 legal changes and afterwards. As advocates of resource mobilization theory emphasize, public policy advocacy has “significant costs” (Salamon, Reference Salamon2002: 20), especially the salaries for experienced staff members. Many of our respondents emphasized the challenges of raising funds for public policy work: “It's really difficult to fundraise for advocacy” (Respondent 70, 2022). Given that the federal government does not allow organizations to use federal funds for advocacy towards the government, the two main alternative funding sources are philanthropic foundations and individual charitable donations, neither of which are easy to access and both of which come with strings attached (Chewinski and Corrigall-Brown, Reference Chewinski and Corrigall-Brown2020).

Funding from philanthropic foundations for public policy engagement in Canada is very limited, despite signs of growing interest (Elson and Hall, Reference Elson and Hall2016; Lauzière, Reference Lauzière and Phillips2021; Pearson, Reference Pearson2022). Many of our respondents pointed to this constraint: “How on earth are we going to get Canadian philanthropies to support us? We have not cracked it . . . We have not been able to facilitate a conversation with Canadian philanthropists about funding policy engagement in the international development sector” (Respondent 64, 2022). The one significant exception is the US-based Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which is the primary source of foundation funding for policy advocacy in the international development sector in Canada. While nine Cooperation Canada member organizations were able to access Gates funding for policy work (totalling at least $14.6 million from 2014–2022), those funds are also directed towards specific policy issues and require reporting on short to medium term outcomes, which can limit the scope of policy work.Footnote 16

Individual donations to Canadian charities are at historic lows (Canada Helps, 2023) and fundraising for public policy work is particularly difficult. As one policy director explained, “It's a really hard sell to make public policy work sound interesting to donors. It feels less immediate . . . The measurables are also more difficult. It's very hard to show that funds for advocacy actually have impact. Policy shifts can take decades. People don't want to give money for hypothetical policy wins decades down the road” (Respondent 49, 2018). Another argued somewhat more optimistically that while some donors will support policy work, the international development sector as a whole has “not yet realized the potential for advocacy-related fundraising” (Respondent 55, 2018). Charitable donations are also no panacea for policy engagement. Some policy directors reported that they felt just as constrained by their individual donors as by federal funding. One highlighted the challenge of “being true to what our partners in the global South are asking us to do, without losing our supporters here [in Canada]” (Respondent 34, 2016), while another noted “the fine line between what our partners [in the global South] want us to do and what our donor and member base [in Canada] will support” (Respondent 55, 2016).

In sum, the overall lack of resources to support policy engagement continues to operate as a major constraint on charities’ investments in it, despite the 2018–2019 legal changes. In this context, the primary funding pattern for policy engagement by charities is relatively large-service delivery organizations that allocate a very small proportion of their total revenue to public policy work—typically drawing on “unrestricted funding” from individual charitable donations. Some charities have also been able to supplement those unrestricted funds with philanthropic grants, most notably from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—but for most these still represent a small proportion of their overall budgets.

Coalitions as a strategy for collaboration and avoiding policy engagement

In the context of scarce resources and ongoing risk aversion, many charities emphasized in interviews both before and after the 2018–2019 legal changes that they do not engage with federal public policy issues on their own but rather through coalitions of like-minded organizations. Advocacy coalitions enable their members to pool resources and also provide political cover on controversial issues (see Corrigall-Brown, Reference Corrigall-Brown2022: 54–84; Levi and Murphy, Reference Levi and Murphy2006; Staggenborg, Reference Staggenbord1986).Footnote 17 Indeed, many of our respondents highlighted sectoral collaboration through coalition organizations as a “critical success factor” for public policy engagement (Respondent 81, 2023) but also lamented that the sector does not collaborate more in efforts to influence federal policy. The typical coalition arrangement involves individual member organizations that provide funding, and a coalition office that provides research, campaign planning, coordination and public-facing policy advocacy. In that arrangement, the role of individual organizations varies widely, from only making financial contributions to participation in insider lobbying to outsider campaigning. Nevertheless, many of our respondents implied what one policy director acknowledged openly: “we let them [the coalition office] do the heavy lifting” (Respondent 75, 2023). In this context, some charities in the international development sector support policy engagement through financial contributions to coalitions but do not actively engage in efforts to influence policy on their own, especially through public calls to action and other outsider tactics.

The uneven distribution of work between coalition offices and member organizations frustrated some coalition staff and charity leaders. As the sole staff member of one coalition organization explained, “It can't be just the coalitions that do all the work. Coalitions can do the background research and advocacy coordination, but the members need to engage the broader public and the politicians. The member organizations are much better known (to the public), but sometimes they won't speak out” (Respondent 52, 2018). The director of one of the more outspoken charities similarly complained that in some coalitions it is “only a few that are willing to speak to the media” (Respondent 82, 2023).

Coalition funding can also be a constraint. Apart from Cooperation Canada and CanWaCH, which both have mandates that extend well beyond policy engagement, most coalition organizations are very small—often with only enough funding for one staff member. As another charity director acknowledged, “None of the advocacy coalitions have real resources or institutional stability” (Respondent 10, 2016). When coalitions are well-funded and member organizations participate actively in coalition-led campaigns, evidence suggests that they can be very effective strategies for policy change (Corrigall-Brown, Reference Corrigall-Brown2022). Unfortunately, the opposite pattern of modest funding and passive engagement by member charities in policy coalitions appears to be widespread, with coalitions serving as much to mitigate the perceived risks of policy engagement as to increase effectiveness.

Conclusion

Five years after the ITA and CRA regulations changed to allow Canadian charities to engage in “unlimited” nonpartisan public policy activities, it appears that few organizations in the international development sector have taken advantage of this opportunity. Our research indicates that only a small group of international development charities ever engaged seriously in efforts to influence federal public policy, and that neither the number of charities nor the intensity of their policy engagement changed significantly following the 2018–2019 changes in the ITA and the CRA regulations. Interviews with charity leaders point to at least three interconnected reasons for the apparent lack of change in behaviour by charities despite the change in the law.

First, the CRA regulations on “political activities” from 2003 to 2019 had restricted outsider forms of public policy engagement that involved calls to public action for the purpose of changing laws, policies or decisions of governments. However, almost all the charity leaders we interviewed indicated that their organizations avoided outsider approaches to policy engagement, not only because of the CRA regulations but also because they believe insider approaches are more effective and less likely to jeopardize federal government funding, which almost all of the larger charities in the international development sector receive.

Second, charity leaders also emphasized that it was not so much the ITA and the CRA regulations themselves that had generated confusion and fear among charities, but rather the perception that the Conservative government of Stephen Harper had politicized the CRA regulations by targeting charities that challenged government policies with special audits coupled with cuts in funding to organizations that were seen as opposed to the Conservative government's policies. The 2018–2019 changes in the law did not alleviate concerns that a future government might reintroduce restrictions on policy engagement or simply intimidate outspoken charities by weaponizing the CRA's audit powers and/or cutting funding to charities that challenge government policies. In the context of those concerns, many charity leaders indicated that they were reluctant to make new investments in public policy capacity or engage in outsider strategies. Similarly, charity leaders highlighted that misunderstanding, confusion and uncertainty persist about the ITA and the CRA regulations and broader attitude of the federal government towards policy engagement by charities, especially among boards of directors. In the context of that uncertainty, charities generally seek to mitigate the perceived risks of being audited, losing charitable status or losing government funding by avoiding policy engagement altogether, opting for less risky insider approaches and/or engaging in public advocacy largely under the cover of coalitions. These responses by charities reflect constructivist approaches to institutionalism by calling attention not simply to the laws but also to the ways that they are understood by political actors, including those within civil society.

Finally, the charity leaders we interviewed both before and after the 2018–2019 changes in the law highlighted important nonregulatory factors that shape their decisions about whether, how much and how to engage with government policy. These included the strategic preference for insider forms of policy engagement and related concerns to not jeopardize government funding, as well as the serious challenges of raising money to support public policy engagement, and the perceived difficulties of engaging Canadians in public policy campaigns.

Controversies over the 2003–2018 CRA regulations on “political activities” by charities created a widespread impression that the laws themselves were the primary constraint on public policy engagement by Canadian charities. However, our research comes to a different conclusion. Our interviews with charity leaders suggest that socially constructed understandings of the regulations and nonregulatory constraints related to strategy, funding and organizational culture are more important in shaping public policy engagement by charities than the formal regulatory framework created by the ITA and the CRA regulations. Understandings of the law have been slow to change and many of the nonregulatory constraints have not changed at all, thus providing an answer to the puzzle of why charities’ behaviour does not appear to have changed following a purportedly important change in the law.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423924000623.

Appendix 1: Summary of Public Policy Engagement by Cooperation Canada member organizations with charitable status, 2000-2022 (Ranked by revenue)