Introduction

Our best physical theories contain free parameters that had to take on a narrow range of values in order for our universe to be life-permitting. Furthermore, it seems improbable, on the basis of physical considerations alone, that they would have fallen into this range. Thus, our universe appears ‘fine-tuned’ for the existence of life.Footnote 1 Many theists appeal to this phenomenon as evidence for the existence of God.

Life, especially intelligent life, the reasoning goes, is quite valuable. So if God exists, it is not so improbable that God would ensure that the parameters fall within the life-permitting range. Since it is much more to be expected that they would do so on the assumption that God exists than on the assumption of a naturalistic hypothesis according to which value considerations played no role in their settings, the fine-tuning of the universe is taken to support theism evidentially over naturalism.Footnote 2

While fine-tuning may provide an evidential consideration in favour of theism over naturalism, other phenomena initially appear to point the other way. In particular, the extent, duration, and distribution of suffering and various other forms of evil appear extremely surprising given theism, but not so surprising given that we live in a morally indifferent universe. Here sceptical theists demur.

Given our cognitive limitations, sceptical theists claim, our a priori access to the moral reasons a being like God might have for permitting the sort of evils and distribution thereof we find in our world remains extremely limited. It is quite plausible that God has moral reasons in favour of permitting such things that are beyond our understanding. Sceptical theists insist that these facts about our cognitive limitations dramatically undercut our ability to predict, on the basis of our insight into moral considerations alone, what a being like God would do, and thereby undermine evidential arguments from evil.Footnote 3

If sceptical theism undermines evidential arguments from evil in this way, however, it also threatens to undermine the fine-tuning argument. As noted above, proponents of the fine-tuning argument typically appeal to value considerations as the basis of their judgement that it is not too improbable God would create a life-supporting universe. But if sceptical theists are right, it is plausible there are strong moral reasons against God’s creating a life-permitting universe beyond our ken. And this fact undermines the rationality of the judgement that God is not unlikely to do so.Footnote 4

Indeed, sceptical theism threatens a large family of evidential arguments for theism that purport theism best accounts for various features of our world because a being like God would likely bring them about. In so doing, it threatens to undercut the basis many would otherwise have for being theists to begin with.Footnote 5 Thus, sceptical theists appear to face a dilemma.Footnote 6 They can give up their strategy for resisting evidential arguments from evil and (in the absence of alternative strategies) find their theistic belief undermined by such arguments. Or they can lean into that strategy and (in the absence of alternative grounds) find the rationality of their theistic belief undercut.Footnote 7

In this paper, I show how sceptical theists can escape this bind. I do so by presenting a version of the fine-tuning argument that does not rely on a priori insight into what moral reasons a being like God might have. In putting forward this version, I also exhibit a more general strategy by which sceptical theists can deploy evidential arguments for theism.

The standard fine-tuning argument

In these first two sections, I will draw into sharper relief the difficulties sceptical theists face in endorsing standard versions of the fine-tuning argument. I will begin by providing a representative formulation of that argument.Footnote 8 As noted above, the fine-tuning argument draws upon the observation that our best physical theories contain free parameters that fall within a narrow life-permitting range even though physical considerations alone appear to render it improbable that they would have done so.

One particularly striking and much discussed example of this pertains to the value of the effective cosmological constant.Footnote 9 The cosmological constant is a parameter in Einstein’s field equations that pertains to the rate at which the expansion of the universe accelerates. The value of the effective cosmological constant is the value of this parameter modified by all the other forms of energy in the universe that influence the rate of acceleration of the universe’s expansion. Fortunately, its value is near (though slightly above) 0, since had it been much larger in the positive direction, the universe would have expanded too rapidly for complex structures to form, and had it been much larger in the negative direction, the universe would have collapsed on itself before such structures were able to form. Based solely on considerations from quantum field theory, estimates of the probability that the value of the effective cosmological constant would fall close enough to 0 so as to be life-permitting lie between 10−60 and 10−120.

Following a terminological suggestion from Roger White, let us summarise such fine-tuning data under the observation that the life-permitting requirements for our universe are ‘stringent’ (White Reference White2011). And let ‘S’ denote a proposition encapsulating the precise manner in which the requirements are stringent as indicated by our current best science. That is, S is a proposition that describes in detail what our best contemporary theories say about the character of the life-permitting requirements and the specific facts that would lead one to expect it unlikely, on the basis of physical considerations alone, that those requirements would have been satisfied. S should not be construed, however, to entail that those requirements are satisfied.

Note that S is thereby construed as a proposition that lends itself to the assignment of a low probability of the parameters taking on the life-permitting values, on the assumption that value-neutral considerations alone are relevant. Now let ‘N’ denote naturalism, where naturalism is construed, for present purposes, as the claim that there is nothing at all like God, and the only factors relevant to the parameters taking on their values are physical ones. Finally, let ‘L’ denote the proposition that the universe is life-permitting.

If what proponents of the standard fine-tuning argument say about the stringency of the life-permitting requirements is right, we are entitled to endorse the following claim (which provides the first premise of the standard fine-tuning argument):

(SFTA1) P(L|N&S) has an extremely low value.

That is, we are entitled to endorse the claim that the conditional probability that the universe is life-permitting given naturalism and the information we have about the stringency of the life-permitting requirements is extremely low. The kind of probability at issue here should be construed as epistemic probability. Such probabilities may in turn be construed as measures of rational or evidential support relations that hold between propositions.Footnote 11

Now let ‘T’ denote theism, where theism is the thesis that God exists, where God is construed as an omnipotent, omniscient, and wholly good being. According to proponents of the standard fine-tuning argument, we are positioned to see that life, and especially intelligent life, is valuable, and therefore it is not so unlikely that a being like God would bring it about. These considerations are taken to support the truth of the following premise:

(SFTA2) P(L|T&S) has a value that is not extremely low.

Proponents of the standard fine-tuning argument also typically endorse the following (widely held) principle of confirmation:

(The Likelihood Principle) For any item of evidence E, any pair of hypotheses H1 and H2, and any body of background information, B, E evidentially favours H1 over H2 with respect to B if and only if P(E|H1&B) > P(E|H2&B); furthermore, the greater the ratio of P(E|H1&B) to P(E|H2&B), the more strongly E favours H1 over H2 with respect to B.

Thus, all the above elements may be put together to provide the following (more or less) standard presentation of the fine-tuning argument for theism:

(SFTA1) P(L|N&S) has an extremely low value.

(SFTA2) P(L|T&S) has a value that is not extremely low.

Therefore (via the likelihood principle), L evidentially favours T over N with respect to S.

This version of the fine-tuning argument has the modest conclusion that L merely favours T over N (relative to the specified background information). A more ambitious version might assert (or assert premises that jointly imply) that the value of P(L|T&S) is substantially higher than the value of P(L|N&S), and thus arrive at the conclusion that L strongly evidentially favours T over N.

The argument is also modest in another respect. It aims merely for the comparative conclusion that the evidence from fine-tuning favours theism over naturalism. It does not attempt to establish that theism is probably true, or even that the fine-tuning evidence favours theism over other potential rival hypotheses. If sceptical theism threatens to undermine the modest argument for theism sketched in this section, however, it also threatens to undermine fine-tuning arguments for theism with more ambitious conclusions.

How sceptical theism undermines the standard fine-tuning argument

While the literature has seen much discussion of the first premise of the standard fine-tuning argument, sceptical theism threatens to undermine the second. That is because support for the second premise typically relies (as it did in the presentation above) on an a priori appeal to the sort of moral reasons a being like God would have as a means of predicting what that being would do. And sceptical theists maintain that our ability to deploy such considerations is extremely limited.

We might have initially judged, for example, that it is unlikely that a being like God would permit an event like the Holocaust. Sceptical theists claim, however, that a proper appreciation of our cognitive limitations in comparison with the capacities of a being like God should make us sceptical about that judgement. And given this scepticism, they maintain, we should recognise that we are not in a position to take the fact that the Holocaust occurred as strong evidence against theism. Perhaps, for all we know or can even reasonably judge likely, the securing of some great good, or the prevention of some great evil, turned on God’s permission of that event. Or, perhaps, for all we know or can even reasonably judge likely, God has powerful deontic reasons to permit such events.

But if we are not in a position to judge it unlikely that a being like God would permit events like the Holocaust, then it seems that we are equally ill positioned to judge it likely that God would create a life-permitting universe. We may be positioned to see that life is in fact valuable, and that is one consideration in favour of God’s creating it. But perhaps that is only one consideration among many. Perhaps, for all we know or even reasonably judge likely, some great good would be lost or some great evil occasioned were God to create a life-permitting universe. Or perhaps, for all we know or reasonably judge likely, God has powerful deontic reasons against creating such a universe.Footnote 12

Not all versions of sceptical theism are equally susceptible to this worry. According to what we might call ‘moderate sceptical theism,’ the known facts about evil provide some evidence against the existence of God, but the extent to which they do is significantly mitigated by appropriate theological scepticism.Footnote 13 Since moderate sceptical theists are willing to concede that moral considerations allow us to form some tenuous expectations concerning what a being such as God is likely to do, they might embrace the second premise of the standard fine-tuning argument.Footnote 14 While they might concede that we are not rationally positioned to believe that P(L|T&S) is high, they might also claim that we are rationally positioned to believe that P(L|T&S) is not extremely low. At the very least, they might claim, we are rationally positioned to believe it is not nearly as low as 10−60.

There remains room for scepticism, however, regarding the claim that we are in a position to assign a high enough value to P(L|T&S) to allow the standard version of the fine-tuning argument to go through, without also being in a position to judge it sufficiently unlikely that God would permit events like the Holocaust. Thus, there remains room to question whether moderate sceptical theists can help themselves to the standard fine-tuning argument without undermining their response to the evidential problem of evil. For this reason, I will focus on versions of sceptical theism that are unwilling to concede even this much ground.

Perry Hendricks suggests a strategy akin to the moderate sceptical theist one, but that (unlike it) aims to bypass any reliance on alleged a priori insight into the balance of moral reasons a being like God might have. According to this strategy, at least at a first pass, God is to be identified with the Good itself, and therefore creatures are to be regarded as good to the extent they resemble God (Hendricks Reference Hendricks2023, 224–225). But in order for any creature to resemble God much at all, it must be conscious (Hendricks Reference Hendricks2023, 228–229). Thus, we have some reason to believe that God would be motivated to bring about such creatures, as a means of realising goodness.

Hendricks claims that this reasoning bypasses reliance on a priori insight into the balance of God’s moral reasons, because it relies on a conceptual insight pertaining to what goodness consists in, as opposed to the perceived overall value of things like conscious agents (Hendricks Reference Hendricks2023, 228–229). Finally, Hendricks claims that the strategy exemplified by this response does not really turn on the metaethical claim that God is identical with the Good, but rather on the less controversial claim that if God (conceived of as a maximally great being) exists, then things are good to the extent that they resemble God.

It is far from clear, however, that Hendricks’s strategy succeeds in bypassing any need to rely on our ability to assess the balance of God’s reasons on purely a priori grounds. Let us grant that it is a conceptual truth that if God exists then things are good to the extent that they resemble God. Even so, it is at least conceivable that the creation of such things might lower the total amount of value in the world.

Perhaps there is a kind of moral or aesthetic value in there being no other beings all that much like God, so that God’s uniqueness and perfection shines out all the clearer. Or perhaps there is a unique sort of disvalue in there being creatures who resemble God to a significant degree but also exhibit various imperfections (making them, no matter how good, grotesque caricatures in comparison with the divine). Or perhaps God has strong deontic reasons to refrain from creating. Perhaps as Mark Murphy has suggested, God has moral reasons to refrain from creating on account of the fact that doing so would place God in a particularly intimate relation to non-divine things, thereby displaying a kind of disrespect for God’s own value (Murphy Reference Murphy2021, 145–148).

I do not claim that any of the above suggestions are likely true or even so much as plausible. I do claim that the mere conceivability of God’s having strong moral reasons to refrain from creating things that resemble God (in spite of the conceptual truth that such things would be good) suffices to undercut Hendricks’s claim that his strategy avoids being undermined by sceptical theism.

For these reasons, I will focus on versions of sceptical theism according to which the probability that God would permit events like the Holocaust on our background information is either ill-defined or inscrutable. And I will grant that it follows, by parity of reasoning, that such sceptical theists are committed to the claim that P(L|T&S) is either ill-defined or inscrutable as well.Footnote 19 If I can succeed in showing that even such extreme forms of sceptical theism are compatible with a version of the fine-tuning argument, I will also have succeeded in showing that moderate versions are. So from now on, I will reserve the term ‘sceptical theism’ as a means of referring to this more extreme view.

One might worry that such extreme forms of sceptical theism prove too much and are therefore too implausible at the outset to take seriously. For example, Luke Barnes asks us to imagine a scenario in which ‘we discovered the opening of the Gospel of John written into the interior of every atom’ (Barnes Reference Barnes2012, 1241). Under those conditions, says Barnes, we would have in our possession an ‘Awesome Theistic Argument’. Furthermore, he claims, ‘any objection that would “look foolish” in the face of the ATA must also fail against the FTA unless there is some relevant difference between the cases’. Among the objections Barnes targets with this test is that the fine-tuning argument fails on account of divine inscrutability. The atheist who would resist the ATA on the grounds that if God exists, God’s ways are inscrutable, might seem desperate indeed.

One important difference between the standard fine-tuning argument and the ATA, however, has to do with the relative scarcity of the proposed background information. The background information pertinent to the ATA would include vast swaths of historical information pertaining to the formation and uptake of documents like the Gospel of John, documents that themselves purport to reveal some of God’s intentions. As I will argue in subsequent sections, sceptical theists can properly appeal to such information to support claims about God’s intentions, without violating their scepticism about the extent of our a priori insight.

Since the standard fine-tuning argument treats the fact that the universe is life-permitting as evidence, however, the background information cannot include the fact that the universe contains life, let alone various facts about the unfolding of human history. The only empirical content found in the background information pertains to the structure of the laws of nature and the narrowness of the life-permitting requirements. This leaves sceptical theists with little other to draw upon for information about God’s possible motivations than a priori considerations.

There are, however, alternative ways of formulating the fine-tuning argument that do not presuppose such a limited body of background information. John Roberts notes that on the standard formulation of the fine-tuning argument, the stringency of the life-permitting requirements is taken as part of the background information while the fact that the universe is life-permitting is taken as evidence (Roberts Reference Roberts2012). As Roberts observes, this is opposite the historical order in which we actually encountered these items of information.

Thus Roberts proposes an alternative formulation of the fine-tuning argument that reflects this historical order.Footnote 22 The version of the fine-tuning argument that I will claim sceptical theists can endorse proceeds in a similar manner. But before I develop it, I need to say more about what sort of additional background information might prove useful to sceptical theists who wish to endorse a fine-tuning argument.

On the probative value of alleged divine disclosure

While sceptical theists deny that we have significant access to God’s motivations via a priori considerations, they are not thereby committed to the claim that we have no significant access whatsoever. Religious sceptical theists can consistently maintain, for instance, that we have access to God’s motivations via religious experience and other forms of divine revelation. They can consistently maintain this, that is, provided they can also consistently maintain that their sceptical theism does not undermine proper trust in the content of such divine disclosure.

Granted, some have argued that sceptical theist considerations do undermine any otherwise rational trust religious theists might have in the alleged content of divine revelation. That is because, if we set aside the implausible Kantian view that intentional deception is always wrong, sceptical theists cannot maintain on the basis of a priori insight into the sort of moral reasons God has that God is unlikely to deceive intentionally.Footnote 23

But, as Aaron Segal points out, religious sceptical theists need not maintain that they know God is unlikely to deceive solely on the basis of such considerations. They might, for instance, take themselves to have inductive or other evidential grounds for believing that divine testimony is reliable. Or they might adopt a non-reductive view of testimony according to which it is rational to accept an item of testimony in the absence of positive reasons to doubt its veracity (Segal Reference Segal2011, 91–92).

Even so, one might think that such purported items of divine disclosure are useless to those who wish to endorse a fine-tuning argument for the existence of God. The fine-tuning argument is aimed, one might protest, at those who do not already believe, and so cannot take for granted claims that entail God’s existence (such as that God has engaged in acts of divine disclosure).

But, in fact, what turns out to be required for the purpose of the alternative version of the fine-tuning argument that I will develop is not that sceptical theists be in a position to assign rationally a non-negligible probability to the veracity of any given item of purported divine revelation. Rather, what turns out to be required is that they are positioned to assign rationally a non-negligible probability to the veracity of various purported items of divine revelation on the supposition that theism is true given the historical information we possess.

Not only sceptical theists, but even atheists (who share their scepticism concerning our a priori insight into what a being like God would do) might find themselves in that situation. An atheist might, for example, take the probability that God exists to be very low, while nonetheless assigning a moderately low to middling conditional probability that one of the major theistic religions is correct on the supposition that theism is true.Footnote 25

So let ‘D’ be a highly detailed proposition that reports a vast collection of known historical facts, including facts about occurrences of what people have taken to be instances of divine revelation, but excluding facts pertaining to the discovery that the parameters are stringent. Let ‘T*’ denote the proposition that theism is true and that God intended to create a life-permitting universe. Since much of the contents of alleged divine disclosures throughout history have included or entailed the proposition that God intended to create a life-sustaining universe, I claim that sceptical theists (as well as atheists and agnostics who share their scepticism about our a priori insight into what a being like God would do) may consistently assign a value to P(T*|T&D) that is not extremely low.

Further considerations regarding sceptical theism and divine disclosure

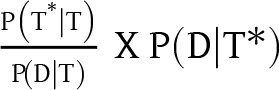

Some might object that the sort of sceptical theists on which we are focusing may not consistently assign such a value. Recall that our focus is on those sceptical theists who are committed to the claim that probabilities such as P(T*|T) and P(D|T) are ill-defined or inscrutable. But, according to Bayes’ theorem,  ${\text{P}}\!\left( {\text{T}}\!*\!|{\text{T} \& \text{D}} \right){\text{ }} = \;\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}\;\,{\text{X P}}\!\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T*}}} \right).$ So, the argument goes, since P(T*|T) and P(D|T) are ill-defined or inscrutable, P(T*|T&D) is as well.

${\text{P}}\!\left( {\text{T}}\!*\!|{\text{T} \& \text{D}} \right){\text{ }} = \;\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}\;\,{\text{X P}}\!\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T*}}} \right).$ So, the argument goes, since P(T*|T) and P(D|T) are ill-defined or inscrutable, P(T*|T&D) is as well.

It is manifestly false, however, that, in general, if P(A|B) is inscrutable or ill-defined then P(A|C&B) is also inscrutable or ill-defined. It might be for example that while P(A|B) is inscrutable or ill-defined, C and B jointly imply A, making it the case that P(A|C&B) = 1. Or it may be that C carries additional information about the expectability of A given B. For example, C&B might carry frequency information about the class to which A pertains that was lacking in B.

But what of the argument, employing Bayes’s theorem, offered above, for the conclusion that if P(T*|T) and P(D|T) are ill-defined or inscrutable, so is P(T*|T&D)? Either Bayes’s theorem does not apply (because the theorem holds only when all the conditional probabilities involved are well defined) or it turns out that the product  $\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}\;{\text{X P}}\!\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}*} \right)$ remains scrutable in spite of the fact that P(T*|T) and P(D|T) are not.

$\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}\;{\text{X P}}\!\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}*} \right)$ remains scrutable in spite of the fact that P(T*|T) and P(D|T) are not.

Let us suppose the latter possibility obtains. If so, perhaps neither  $\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$ nor P(D|T*) is scrutable (after all, D contains a lot of specific information that is irrelevant to the divine intentions reported by T*). Or perhaps both P(T*|T&D) and P(D|T*) are scrutable, thereby rendering

$\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$ nor P(D|T*) is scrutable (after all, D contains a lot of specific information that is irrelevant to the divine intentions reported by T*). Or perhaps both P(T*|T&D) and P(D|T*) are scrutable, thereby rendering  $\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$ scrutable as well. In either scenario we have a situation in which the product of two factors (either

$\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$ scrutable as well. In either scenario we have a situation in which the product of two factors (either  $\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$ and P(D|T*) or P(T*|T) and

$\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{{\text{T}}^{\text{*}}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$ and P(D|T*) or P(T*|T) and  $\frac{1}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$) is scrutable even though the factors themselves are not. But of course such scenarios are readily possible. I might know, for example, that the product of the circumference of a given circle with the reciprocal of its diameter is π without having a clue as to the size of the circle.Footnote 26

$\frac{1}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{D}}|{\text{T}}} \right)}}$) is scrutable even though the factors themselves are not. But of course such scenarios are readily possible. I might know, for example, that the product of the circumference of a given circle with the reciprocal of its diameter is π without having a clue as to the size of the circle.Footnote 26

Another kind of objection one might press against sceptical theists who maintain that P(T*|T&D) is both scrutable and not low is that such a position threatens to undermine the sceptical theist response to the problem of evil. Perhaps some of the content of D probabilifies subsets of the theistic hypothesis according to which God has intentions on which we would not expect some of the evils we observe.

Even if that is the case, however, sceptical theists might rest content with achieving a more limited ambition. They might take sceptical theism as a vehicle primarily for blocking evidential arguments from evil that attempt to rely on a priori insight to discern what a being like God is likely to do. This leaves room (rightfully so!) for versions of the problem of evil to arise in connection with more specific religious claims concerning the contents of God’s intentions.

That said, it is also true that (given how detailed it was stipulated to be) D already entails the occurrence of much of the evil that has already taken place. Thus the conditional probability that God often permits many of the sorts of evils with which we are familiar given the conjunction of D and T is high.Footnote 27 Furthermore, specific religious traditions may offer resources for explaining why certain evils occur that are not probable on a priori grounds alone.Footnote 28 Finally, sceptical theists may also invoke sceptical considerations to undermine inferences to the effect that God is failing to realise intentions probabilified by D in morally optimal ways.

A fine-tuning argument for sceptical theists

We now have all the resources in place to construct a version of the fine-tuning argument sceptical theists may consistently endorse. In this section, I offer an intuitive presentation of the argument and reply to some objections. In the next section, I offer a formal version of the argument. The argument takes the stringency of the life-permitting requirements as the relevant item of evidence rather than the fact that the universe is life-permitting. It also draws upon historical information regarding the alleged content of divine revelation in order to support probabilistic judgements concerning God’s intentions. An initial presentation of the argument proceeds as follows:

Given background information that includes the fact that the universe is life-permitting, one would expect that it was not too difficult for it to have been so. It is for that reason extremely surprising given naturalism and historical information that includes the fact that life has arisen to discover that the parameters of nature are so stringent. However, it is not that surprising on the assumption that theism is true and that God intentionally brought about a life-permitting universe. That is because, since God is conceived to be omnipotent, theism makes the extent to which the parameters are stringent irrelevant to how difficult it was for life to arise. Furthermore, the claim that God did have such intentions is not so improbable given both bare theism and historical information that includes alleged instances of divine revelation whose content entails that God had those intentions.

This intuitive presentation of the argument involves two central premises. The first is that it is highly improbable given naturalism and the fact that the universe contains life that the parameters are stringent. The second is that it is not so improbable given theism and the claim that God intended to create life that the parameters are stringent.

Cory Juhl raises a potential objection to the first premise. He argues that any given complex phenomenon tends to be ‘causally ramified’. That is, it ends up ‘depending, for its existence, on a large and diverse collection of logically independent facts’ (Juhl Reference Juhl2006, 271). Since life is such a phenomenon, it is not surprising, on background information that includes the fact that life exists, that it too is causally ramified. It is also not surprising, Juhl argues, that mathematical models of the conditions required for a causally ramified phenomenon include parameters whose values must fall within an extremely narrow range in order to correspond with those conditions. Thus it is unsurprising, Juhl concludes, that the physical parameters that describe our life-permitting universe do in fact exhibit such sensitivity (Juhl Reference Juhl2006, 272).

Juhl is right to insist that the mere sensitivity of the life-permitting parameters is unsurprising given that life does in fact exist. But the key premise here is not that it is surprising given naturalism and the fact that the universe contains life that the parameters are sensitive. Rather, it is surprising that they are stringent. As we have characterised stringency, the parameters are stringent when it is unlikely, on the basis of physical considerations alone (excluding the information that life exists), that their values are life-permitting. It is easy to see that these two notions can come apart. A parameter might be such that its life-permitting values fall within an extremely narrow range, but our best physical theories might also render it highly probable (for reasons having nothing to do with the existence of life) that its value would have fallen within that range.

It is true that some proponents of the fine-tuning argument attempt to infer that it is improbable that the parameters would fall within the life-permitting range from the fact that they are sensitive. As Juhl rightly points out, this is a mistake (Juhl Reference Juhl2006, 272–273). But it is not one made by every proponent of the fine-tuning argument. As Hawthorne and Isaacs point out, for instance, the considerations that lend themselves to the conclusion it is surprising that the value of the effective cosmological constant falls within the life-permitting range have to do with what quantum field theory would lead us to expect that value to be, not with the fact that the parameter is sensitive (Hawthorne and Isaacs Reference Hawthorne, Isaacs, Benton, Hawthorne and Rabinowitz2018, 164).

Indeed, given how stringency was defined, it just follows that ![]() ${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low. And while the claim that the parameters are stringent in that sense faces objections, none of them pertain to the worries raised by sceptical theism that are of present concern (as they target the second premise of the standard fine-tuning argument, not the first). Thus in the current dialectical context, we may simply take the stringency of the requirements for granted.Footnote 33 It is a short distance, furthermore, from the claim that

${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low. And while the claim that the parameters are stringent in that sense faces objections, none of them pertain to the worries raised by sceptical theism that are of present concern (as they target the second premise of the standard fine-tuning argument, not the first). Thus in the current dialectical context, we may simply take the stringency of the requirements for granted.Footnote 33 It is a short distance, furthermore, from the claim that ![]() ${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low to the claim that

${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low to the claim that ![]() ${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{L}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is very low.Footnote 34

${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{L}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is very low.Footnote 34

Let’s stipulate that a probability counts as ‘extremely low’ when its value is less than or equal to 10−30, and as ‘very low’ when its value is less than or equal to 10−20. Let’s also stipulate that a proposition is ‘at least somewhat plausible’ on a given supposition or body of information when its epistemic probability on that body or supposition is greater than or equal to 10−10. Of course, these stipulations are wholly artificial. But having some artificial precision can be useful when evaluating (what are fundamentally) qualitative comparisons between probabilities. The arguments below that use these stipulations remain robust under alternative precisifications, provided that they preserve the relevant comparative order of magnitude claims. And all that really matters, as far as the dialectic is concerned, is whether sceptical theists may sensibly endorse those comparisons.

According to Bayes’ theorem, P(S|N&L) =  $\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right){\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}$. Since (given what has already been said),

$\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right){\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}$. Since (given what has already been said), ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 10−60, P(S|N&L) is itself very low unless

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 10−60, P(S|N&L) is itself very low unless  $\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}$ is high enough to offset that extremely low value. Indeed, to prevent P(S|N&L) from being very low, it must be that

$\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}$ is high enough to offset that extremely low value. Indeed, to prevent P(S|N&L) from being very low, it must be that  $\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}$ > 1040. And since

$\frac{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}{{{\text{P}}\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)}}$ > 1040. And since ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 1, in order for that to happen, it must be that

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 1, in order for that to happen, it must be that ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−40. It is at least somewhat plausible given naturalism alone, furthermore, that S would fail to be true (i.e., at the very least,

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−40. It is at least somewhat plausible given naturalism alone, furthermore, that S would fail to be true (i.e., at the very least, ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {\sim}{\text{S}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ 10−10). But note that

${\text{P}}\!\left( {\sim}{\text{S}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ 10−10). But note that ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\sim}{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right){\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$. So

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\sim}{\text{S}}|{\text{N}}} \right){\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$. So ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−40 only if

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−40 only if ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−30. That is,

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−30. That is, ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−40 only if

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{N}}} \right)$ < 10−40 only if ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low.

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low.

But ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is not extremely low. Granted, on some hypotheses incompatible with S, the parameters are as or more stringent than S entails they are. But on others, the requirements are fairly lax. Let’s have ‘R’ denote the proposition that the parameters are ‘relaxed’. More exactly, let’s stipulate that ‘R’ denotes a disjunction of mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive scientific propositions, pertaining to the character of the life-permitting requirements, such that for each proposition, R*, in that disjunction,

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is not extremely low. Granted, on some hypotheses incompatible with S, the parameters are as or more stringent than S entails they are. But on others, the requirements are fairly lax. Let’s have ‘R’ denote the proposition that the parameters are ‘relaxed’. More exactly, let’s stipulate that ‘R’ denotes a disjunction of mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive scientific propositions, pertaining to the character of the life-permitting requirements, such that for each proposition, R*, in that disjunction,  ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{{\text{R}}^{\text{*}}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ 10−10. Since R entails ∼S,

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{{\text{R}}^{\text{*}}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ 10−10. Since R entails ∼S, ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right){\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{R}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$. So,

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right){\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\text{R}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$. So, ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ 10−10 ×

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≥ 10−10 × ![]() ${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$. So

${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$. So ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 10−30 only if

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 10−30 only if ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 10−20. That is,

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ ≤ 10−20. That is, ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low only if

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{L}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is extremely low only if ![]() ${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is very low.

${\text{P}}\!\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is very low.

But ![]() ${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is not very low. Prior to the discovery of the stringency of the life-permitting requirements, it would have been reasonable for naturalists to think it at least somewhat plausible that life is just an interesting complex phenomenon that arises fairly easily under a wide array of conditions. So I conclude that

${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{R}}|{\sim}{\text{S}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is not very low. Prior to the discovery of the stringency of the life-permitting requirements, it would have been reasonable for naturalists to think it at least somewhat plausible that life is just an interesting complex phenomenon that arises fairly easily under a wide array of conditions. So I conclude that ![]() ${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{L}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is in fact very low. More cautiously, I conclude that sceptical theists may consistently endorse the claim that

${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{L}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is in fact very low. More cautiously, I conclude that sceptical theists may consistently endorse the claim that ![]() ${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{L}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is very low.

${\text{P}}\left( {{\text{S}}|{\text{L}}\& {\text{N}}} \right)$ is very low.

The second premise is subject to an objection that has been articulated (in slightly different ways) by Jonathan Weisberg and Hans Halvorson (Weisberg Reference Weisberg2010; Halvorson Reference Halvorson, Benton, Hawthorne and Rabinowitz2018). They assert that it is surprising that God would make the parameters stringent, given that God intended to create a life-permitting universe. If (as most theists would presume) God had control over the stringency of the constants of nature, and God wanted a life-permitting universe, then why make things more difficult?

In response, it may be said that since God is omnipotent, God does not in fact make the job of creating a life-supporting universe more difficult by making the parameters stringent. God can make the requirements as stringent as God likes (so long as they do not entail the impossibility of life) and then meet them without expending any additional effort. In other words, the theistic hypothesis envisioned renders the stringency of the requirements irrelevant to how difficult it was for life to have arisen, thereby screening off the predictive value of the fact that our universe is life-permitting with respect to the claim that the parameters are not stringent. And it is not too surprising on a priori grounds alone (without taking into consideration that the universe is in fact life-permitting) that the requirements would be stringent.

Furthermore, there are at least some plausible motivations God might have for making the life-permitting requirements stringent. The laws of nature, as they stand, appear to many physicists to be quite elegant and beautiful. Perhaps the most beautiful, elegant laws also tend to have parameters that must be finely tuned in order for there to be a life-permitting universe. Or perhaps God intended to include within reality some trace of God’s own intentional design, and for that reason made the life-permitting requirements stringent and then met them.Footnote 36 It is true that sceptical theists cannot consistently claim to discern a priori on the basis of moral considerations that it is plausible that God has such motivations. But the content of the alleged divine disclosures included in D plausibly supplies enough information about God’s alleged intentions to support these claims, at least well enough to prevent the conditional probability on D that God has such intentions from being ill-defined, inscrutable, or negligible.

A formal version of the argument

I have argued that it is not very unlikely given theism and the fact that God intended to create a life-permitting universe that the parameters are stringent. I have also argued that P(S|N&L) is very low. Since (given naturalism) D does not contain additional relevant information concerning whether the parameters are stringent beyond its entailing L, we may also conclude that P(S|N&D) is very low. Unfortunately, it does not obviously follow from these claims that P(S|T&D) > P(S|N&D).

The reason is that S has been characterised as encapsulating a highly specific and detailed body of information, including the actual ranges of the life-permitting values and the like. It is difficult to assess the probability that such specific facts would obtain given theism and the claim that God intended to create a life-permitting universe. Perhaps it too is very low. Fortunately, there is a workaround.

Let ‘S^’ be the disjunction of every proposition, S*, encapsulating a possible set of scientific facts such that P(L|N&S*) ≤ 10−60. Thus it is also the case that P(L|N&S^) ≤ 10−60. Note that an argument parallel to the one given in the previous section establishes that P(S^|N&L) is very low and therefore also that P(S^|N&D) is very low.

Now (as before), let ‘T*’ denote the proposition that theism is true and that God intentionally brought about a life-permitting universe. Note that (by the total probability theorem), P(S^|T&D) ≥ P(T*|T&D)P(S^|T*&D) (provided that all the probabilities at issue are well defined). Thus P(S^|T&D) is very low only if P(T*|T&D)P(S^|T*&D) is very low or ill-defined. But (by the arguments provided in the previous two sections), both P(T*|T&D) and P(S^|T*&D) are well defined and far from very low (far enough that their product is also not very low). Or at least, I have argued, sceptical theists may consistently claim as much. So sceptical theists may consistently claim that P(S^|T&D) has a value that is not very low.

Finally, we note that, according to the fine-tuning argument, what evidentially distinguishes between theism and naturalism is the stringency of the fine-tuning requirements themselves, not the specific details regarding the precise ranges of the life-permitting values and the like. Accordingly, we may assert that P(S|S^&N&D) = P(S|S^&T&D).

We may now put all of these pieces together to arrive at the following, sceptical-theist-friendly version of the fine-tuning argument:

(STFFTA1) P(S^|N&D) has a very low value.

(STFFTA2) P(S^|T&D) has a value that is not very low.

(STFFTA3) P(S|S^&N&D) = P(S|S^&T&D)

Therefore, S favours T over N with respect to D.

This argument is formally valid (given the likelihood principle) and has premises that a sceptical theist may consistently endorse.Footnote 37

Conclusion

I have defended the claim that sceptical theists can endorse a version of the fine-tuning argument by appealing to historical information about alleged divine disclosures that probabilifies certain claims concerning God’s intentions. The general strategy that I employ can also be used by sceptical theists as a means of endorsing other kinds of evidential arguments for theism. Thus sceptical theists need not choose between endorsing such arguments and abandoning their preferred strategy for responding to evidential arguments from evil.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sarah Boyce, Bradford Saad, the participants in the Fall 2024 Workshop on Fine-Tuning at the University of Mississippi, and various anonymous referees for helpful comments on previous drafts.

Competing interests

The author declares none.