Introduction

Between the 1970s and the early 21st century, most European welfare states shifted towards the subsidiarisation of social policy and service provision. This transition brought policy implementation closer to citizens by reorganising central authority and expanding the involvement of regional and local actors (Kazepov, Reference Kazepov2010; Bonoli et al., Reference Bonoli, Natili and Trein2019). This phenomenon encompassed two main processes: vertically, it involved either restructuring regulatory powers across different territorial levels – explicit rescaling – or making changes in the relative weight of specific measures regulated at different territorial levels – implicit rescaling –; horizontally, it witnessed a proliferation of public and private actors engaged in designing, managing, and implementing social policies (Kazepov, Reference Kazepov2008: 250). Therefore, subsidiarisation fostered new spaces of solidarity beyond the nation state, where regional and local actors gained the capacity to develop more innovative and responsive social policies (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2009).

In this context, policymakers have operated in a multi-level governance (MLG) context to deal with policy problems, becoming coordination across all levels of government essential for effective policy implementation (Peters, Reference Peters2018; Adam et al. Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill, Peters and Steinebach2019; Bonoli and Trein, Reference Bonoli and Trein2022; Scalise and Hemerijck, Reference Scalise and Hemerijck2024). The need for coordination has gained particular relevance in the field of social assistance and minimum income policy. Growing numbers of people experiencing poverty and social exclusion have placed significant strain on existing regional systems, compelling some European governments – such as those of Italy and Spain – to “rescale back” minimum income provision at the national level. In other words, while during the 1980s and the 1990s, anti-poverty policies underwent “downwards” explicit rescaling – where responsibilities were shifted to lower levels of government –, rising caseloads and budgetary constraints at the regional level after the Great Recession have prompted “upwards” implicit rescaling. This new institutional change involves a shift – although not yet fully institutionalised – in the management, delivery, and financing of minimum income policy from regional to national administrations, leading to a mix of responsibilities and duties across different levels of governance.

Notwithstanding the goodwill of governments to address the problem, rescaling functions for policy delivery across regional and national levels might also be problematic. The existing literature suggests that coordination and administrative costs can increase significantly with the number of governments and jurisdictions involved in policymaking (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003). National governments may take decisions in one policy area without considering prior decisions by subnational units in the same area, or they may impose a preferred policy design while avoiding cooperative practices that could benefit all levels of government involved (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1994; Peters, Reference Peters2018). These multi-level challenges can become even more pronounced during large-scale crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, where coordination problems within and across levels of governance make it increasingly difficult to develop coherent, mutually agreed policy responses within a short negotiation window (Maggetti and Trein, Reference Maggetti and Trein2022; Arriba González de Durana and Aguilar, Reference Arriba González de Durana and Aguilar2021). Therefore, while “higher-order” institutions can establish common rules to promote harmonisation, convergence, and integration in decentralised states, they also have problem-generating potential if coordination is lacking (Maggetti and Trein, Reference Maggetti and Trein2019).

Against this background, the existing literature has provided worthwhile theoretical contributions to the problem-solving capacity of multi-level systems (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1997; Trein et al., Reference Trein, Thomann and Maggetti2019; Maggetti and Trein, Reference Maggetti and Trein2022) and the problem-generating potential of reorganising these systems (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003; Maggetti and Trein, Reference Maggetti and Trein2019). In recent social policy research, a growing number of scholars have examined various aspects of multi-tiered welfare governance. Some scholars have analysed subnational responses to welfare rescaling (Bonoli et al., Reference Bonoli, Natili and Trein2019; Bonoli and Trein, Reference Bonoli and Trein2022), compared the delivery of European Cohesion Funds for social policy in decentralised welfare states (Ballantyne and Mascioli, Reference Ballantyne and Mascioli2024), and explored how vertical coordination between national and subnational levels influences the success of social investment policies (Scalise and Hemerijck, Reference Scalise and Hemerijck2024). Others, meanwhile, have focused on the role of street-level bureaucrats in these processes (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Javornik, Brummel and Yerkes2021; Andreotti et al., Reference Andreotti, Coletto and Rio2024).

Nevertheless, while the literature on policy implementation in multi-level systems is growing and upward welfare rescaling has become more common, the actual impact of these institutional changes on welfare recipients remains largely unexplored. To this end, the present article is interested in exploring the following questions: How does implicit welfare rescaling contribute to the administrative burden faced by welfare claimants, and in what ways does the (lack of) coordination between administrative levels impact this experience? To what extent do horizontal actors recognise the burdens placed on citizens, and what measures do they take to alleviate them?

To address these questions, the article integrates the literature on MLG with administrative burden theory (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015; Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2018; Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Lindgren and Melin2022a). We then propose an original analytical model for assessing policy implementation, arguing that when implicit welfare rescaling occurs in multi-level settings, limited coordination among administrative levels can lead to a complex and inconsistent distribution of responsibilities across levels of government. This, in turn, can create learning, compliance, and psychological costs for welfare claimants when navigating different administrative procedures, ultimately limiting access to welfare benefits. In addition, we state that local welfare systems (LWSs) can mediate between central government actions and potential welfare recipients, aiming to reduce administrative burdens during policy implementation.

To test the analytical model, the article relies on empirical, qualitative case-based evidence, focusing on Spain as a clear example of decentralisation followed by problem-generating welfare rescaling. In this line, the central government introduced in June 2020 the Ingreso Mínimo Vital (IMV) to enhance the integration of the minimum income system and address the limited regional coverage of existing programmes. However, its rapid implementation during the COVID-19 crisis hindered alignment with regional schemes (Arriba González de Durana and Aguilar, Reference Arriba González de Durana and Aguilar2021), leading to overlapping responsibilities across administrative levels. As a result, the government’s welfare rescaling revealed significant shortcomings (Ayala et al., Reference Ayala, Jurado and Pérez2022), reflected in non-take-up rates of around 60% and nearly 1 million application rejections in the first year (AiREF, 2022).

Methodologically, we conducted “interactive” focus group discussions (Belzile and Öberg, Reference Belzile and Öberg2012) with frontline professionals who assisted with the policy application process between 2020 and 2022, as well as four expert interviews with statewide actors involved in policy design. To ensure diversity and territorial representation among the participants, we selected a broad range of experiences and contexts (see Supplementary Table 1 in annexes for a complete description of the participants).

The article is organised as follows. We begin by reviewing the literature on administrative burden and LWSs in MLG contexts. We then build on this scholarship to develop an analytical model to examine how implicit rescaling affects individual experiences and local actors’ responses. Next, we outline our research design, covering case selection, country contextualisation, and data and methods. Finally, we present the empirical analysis, summarise key findings, and highlight our contributions to the existing literature.

Administrative burden, minimum income policy, and the role of LWSs

The concept of administrative burden refers to the onerous and time-consuming experience individuals face when dealing with the administration (Burden et al., Reference Burden, Canon, Mayer and Moynihan2012). This burden can impact both citizens and public employees (Ferraioli, Reference Ferraioli2025). It emphasises how government actions – and particularly the specific way policies are designed and implemented – directly influence how burdensome these experiences feel to people (Baekgaard and Tankink, Reference Baekgaard and Tankink2022; Halling and Baekgaard, Reference Halling and Baekgaard2023). This scholarship states that citizens’ attempts to access public and social policies are formally structured by state-determined rules, regulations, and procedures such as eligibility requirements, forms to complete, documents to submit, and appointments to attend (Baekgaard and Tankink, Reference Baekgaard and Tankink2022). These state actions impose “learning costs” on citizens in identifying public policies they are eligible for and understanding the procedures attached to each policy. They also entail “compliance costs” in time and effort spent on these processes, while “psychological costs” emerge from repeated administrative interactions, causing stigma, stress, and loss of autonomy. When one or more of these costs is high, it creates burdens that may prevent individuals from enrolling, lead to dropout, or hinder programme recognition (Halling and Baekgaard, Reference Halling and Baekgaard2023).

Although all policies generate a certain cost for individuals, these costs are not distributed equally across the population, and their extent depends on individuals’ resources, skills, and sociodemographic features (Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2018; Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Lindgren and Melin2022a). In this light, individuals with higher human capital are physically and mentally more prepared to carry out tasks required by the administration (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Aarøe, Baekgaard, Herd and Moynihan2020). Similarly, individuals with previous experience in dealing with administration have greater “administrative capital” providing them with “empirical knowledge” on how to navigate unclear administrative designs (Döring and Madsen, Reference Döring and Madsen2022; Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021). Financial resources allow individuals to pay for advisory services or even bribe individuals within the administration to expedite processes. Finally, social capital – including family networks and friends, among others – is crucial for supporting individuals to navigate administrative procedures through direct assistance, emotional support, or caring duties (Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021).

Against this background, we posit that minimum income claimants – who possess limited human, administrative, and social capital – may face greater difficulties in navigating administrative processes, making them more susceptible to the impacts of administrative burden compared to others. Recent research in social policy implementation shows indeed that digitalisation and automation of application processes to welfare benefits impose temporal, financial, and emotional costs on some recipients (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Currie and Podoletz2024). In response, the literature highlights strategies to ease administrative burden, particularly for low-skilled individuals, such as simplifying processes or using clearer language and familiar terms (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Giannella, Herd and Sutherland2022).

What role for LWSs?

Beyond the formal administration, citizens’ experiences during policy implementation are also shaped by other public and private entities. As noted by Kazepov (Reference Kazepov2008, Reference Kazepov2010), the horizontal process of subsidiarisation has led, since the 1970s, to a proliferation of actors engaged in the design, management, and implementation of social policies. In this vein, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) identified the third-sector – including voluntary associations, social cooperatives, and various other profit and non-profit entities – as the “fourth leg” of the welfare state, alongside the state, market, and family. This mix of public and non-public actors, together with local and regional administrations, has given rise to what are often called LWSs. In these systems, actors with diverse power resources interact and collaborate in both the deliberation and delivery of welfare services (Johansson and Koch, Reference Johansson, Koch, Johansson and Panican2016; Andreotti and Mingione, Reference Andreotti and Mingione2016; Andreotti et al., Reference Andreotti, Mingione and Polizzi2012; Ranci et al., Reference Ranci, Brandsen and Sabatinelli2014).

The role of LWSs (or local support ecosystems, Edmiston et al., Reference Edmiston, Robertshaw, Young, Ingold, Gibbons, Summers, Scullion, Geiger and de Vries2022) in benefiting welfare recipients is somewhat ambiguous. While their institutionalisation has strengthened local welfare infrastructures and enhanced policy effectiveness, rising demand in times of financial strain has limited their ability to consistently provide effective policy responses (Ranci and Maestripieri, Reference Ranci, Maestripieri, Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022; Scalise, Reference Scalise2021). Their role also varies across countries, with a notable presence in Southern welfare states, where public–private partnerships have long been key to addressing poverty and social exclusion (Saraceno, Reference Saraceno2006; Laparra and Aguilar, Reference Laparra and Aguilar1996). What is certain is that LWSs have played a crucial role in helping welfare claimants reduce the costs of accessing support and services (Nisar, Reference Nisar2018; Tiggelaar and George, Reference Tiggelaar and George2025), addressing recipients’ needs, and fostering local partnerships and innovation (Andreotti et al., Reference Andreotti, Mingione and Polizzi2012). Beyond individual support, these organisations have also advocated for policy changes to central governments, influencing welfare policy design to improve the overall citizen experience (Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2018; Tiggelaar and George, Reference Tiggelaar and George2025).

The analytical model: from welfare rescaling to administrative burden in multi-level systems

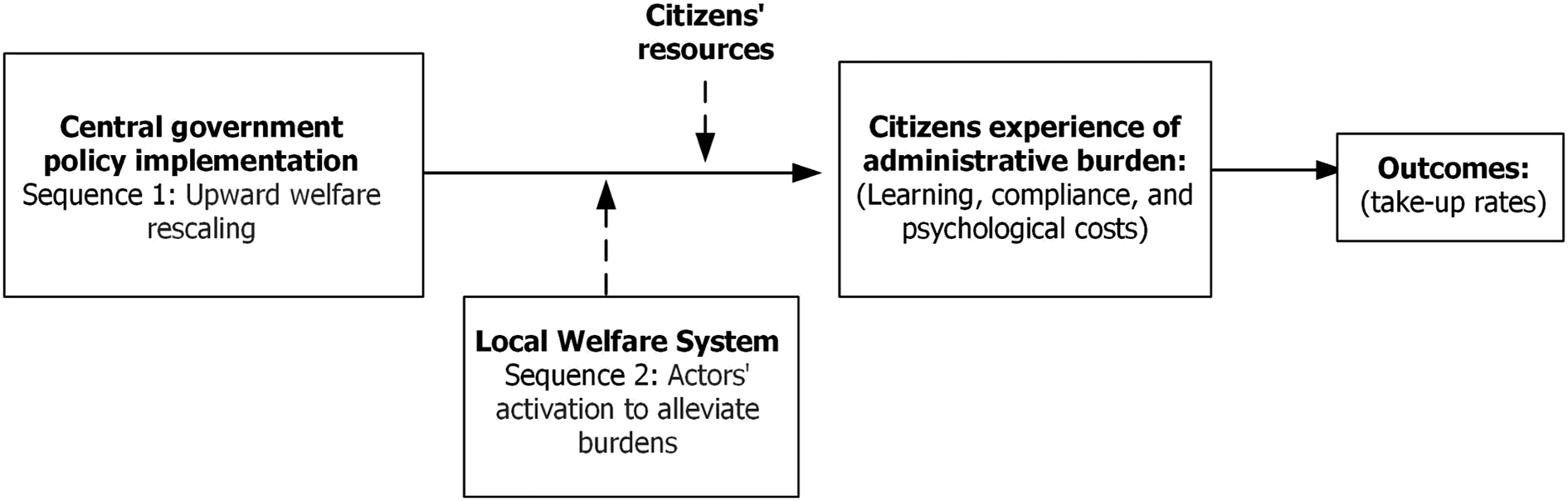

This article investigates how implicit welfare rescaling in Spain contributed to the administrative burden faced by welfare claimants, and in what ways the (lack of) coordination between administrative levels impacted such experiences. It also explores the extent to which the LWS can identify policy problems within this sequence and intervene to reduce them. To accomplish this, the article integrates the MLG literature (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003; Trein et al., Reference Trein, Thomann and Maggetti2019; Maggetti and Trein, Reference Maggetti and Trein2019) with administrative burden theory (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015; Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2018) to develop an original analytical model, presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Analytical model: a two-step sequence to assess social policy implementation.

The article is based on the widely shared assumption that in multi-level systems effective policy implementation requires coordination across all levels of government (Peters, Reference Peters2018; Adam et al. Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill, Peters and Steinebach2019; Bonoli and Trein, Reference Bonoli and Trein2022). This coordination is of particular importance in the field of minimum income, where an increasing caseload and budgetary constraints have put considerable pressure on existing regional systems, prompting some national governments to rescale minimum income provision upwards — at the national level. This does not mean that policy competencies are fully transferred from regional to national levels. Rather, when a national means-tested social benefit is introduced within a regionally fragmented system, some policy responsibilities may be shared or become unclear – for example, determining who is responsible for assisting welfare claimants.

Kazepov and Barberis (Reference Kazepov and Barberis2013, p. 206) describe this situation as “mixed frames in transition,” referring to a change in MLG where new developments have not yet been fully institutionalised. This transitional phase implies implicit rescaling in the management, delivery, and financing of the policy, characterised by a mix of responsibilities and duties among levels of government. In our case, we argue that if the eligibility requirements and application processes of a newly implemented policy differ from those of previous, equivalent policies at the regional level, and coordination between administrative levels is weak, the restructuring of policy responsibilities can lead to significant administrative costs (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003) or shift costs to users (see Arlotti and Aguilar, Reference Arlotti and Aguilar2018, for long-term care provision in Italy and Spain). Some specific examples of this include duplication – for example, administrations may ask citizens for the same information again and again, which imply “temporal costs” (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Currie and Podoletz2024) – or contradictions – where programmes are at odds with one another (Peters, Reference Peters2018).

These inefficiencies, we add, can create burdensome procedures at the individual level, obstructing access to minimum income provision for citizens with limited human, administrative, and financial capital – especially if these limitations are not properly considered when designing the policy. At this point, we draw on administrative burden theory to differentiate between learning, compliance, and psychological costs (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015). In practical terms, this means that if a central government assumes control without fully understanding the documentation requirements that welfare claimants can or cannot fulfil – such as the need for an electronic ID – or without recognising how the application process for the national benefit differs from regional processes previously in place, citizens may face significant compliance costs regardless of the objective functional role of the requirements. It may also occur that citizens, accustomed to interacting with specific offices and requirements, may find these replaced by others without receiving accurate information from the central government. As a result, minimum income claimants may face high learning costs. Altogether can lead to increased stress and loss of autonomy, as individuals struggle to navigate a fragmented and disorganised administrative system, thus incurring in significant psychological costs.

However, the literature on subsidiarisation has shown that horizontal activity plays an important role within this sequence (Kazepov, Reference Kazepov2010; Ranci and Maestripieri, Reference Ranci, Maestripieri, Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022). When policy responsibilities in minimum income are reorganised to give greater weight to the national administration, activating the LWS can help reduce the administrative burden on citizens (Edmiston et al., Reference Edmiston, Robertshaw, Young, Ingold, Gibbons, Summers, Scullion, Geiger and de Vries2022). Regional and local actors can respond to the high costs citizens face due to policies that are not designed taking into account their skills and resources. For example, the LWS can assist welfare claimants helping them gather documentation, guiding them through different administrative levels, or requesting changes in policy design to the central government.

As illustrated in Figure 1, our analytical model addresses the two research questions by examining a two-step sequence. First, implicit rescaling from regional to the national levels of government takes place, which can result in burdensome experiences and high costs for citizens if there is neither positive nor negative coordination. Positive coordination refers to a process where decisions made in one public policy consider those made in others, aiming to avoid conflicts. Negative coordination, however, goes a step further, requiring organisations not only to avoid conflicts but also to actively seek cooperative solutions that benefit all organisations and individuals involved (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1994; Peters, Reference Peters2018). This may also happen because policies are implemented without accounting for the specific characteristics and the limited human, administrative, and social capital of the targeted individuals. In a second step, LWSs may intervene, identifying costs and mediating between central government actions and citizens to mitigate the administrative burden experienced by minimum income claimants.

Research design: A qualitative, explorative approach

This section is divided into two subsections. First, we explain why Spain and Catalonia in particular are an intriguing example for addressing our research questions and testing our analytical model. We also provide case-specific context. Second, we outline the data and methods used.

Case selection: Why Spain?

Spain has lacked a nationwide minimum income system, relying since the 1990s on a regional model (Aguilar and Arriba González de Durana, Reference Aguilar and Arriba González de Durana2020). The 1978 constitution established a distribution of powers with elements of both dual and cooperative federalism (Del Pino and Pavolini, Reference Del Pino and Pavolini2015). Thus, while certain powers are exclusive to the central government (e.g., social security), others are exclusively reserved to regional governments (e.g., social services) or are shared among the administrative levels (Del Pino and Pavolini, Reference Del Pino and Pavolini2015). In the field of minimum income, the absence of a national legislative framework led to processes of policy development that did not follow a clear directional pattern (Gallego and Subirats, Reference Gallego and Subirats2012). Therefore, minimum income policy has been characterised by a highly fragmented system, with each region setting its own eligibility criteria and income thresholds. This, in turn, has caused uncoordinated decentralisation (Natili, Reference Natili2020) and significant coverage gaps nationwide (Aguilar and Arriba González de Durana, Reference Aguilar and Arriba González de Durana2020).

To deal with a model with limited coverage in a context of increased caseload, the national government implemented a statewide scheme (IMV) in June 2020. The IMV was a tax-funded safety net based on a means test set at 61.4% of the 2019 relative poverty threshold, and it aimed to establish a “common floor” and expand coverage (Soler-Buades, Reference Soler-Buades2025). The income level exceeded that of many regional schemesFootnote 1, and it was made compatible with existing regional schemes; regions could either use the new national scheme to supplement regional levels or choose to replace one with the other. Hence, while responsibilities for minimum income provision remain regional, the national government now oversees a new means-tested social security benefit. For the first time, the national government has taken on powers traditionally held by regional authorities in anti-poverty policy, including control over the application process, budget management, compliance, auditing, and financial relations.

The implementation of the IMV expanded coverage to nearly 300,000 more households compared to the previous regional model (AiREF, 2023). However, despite this significant policy advancement, the limited timeframe during the COVID-19 crisis hindered effective coordination between the IMV and regional programmes (Arriba González de Durana and Aguilar, Reference Arriba González de Durana and Aguilar2021). As a result, policy implementation faced substantial challenges (Ayala et al., Reference Ayala, Jurado and Pérez2022), with non-take-up rates around 60%—meaning 6 of 10 eligible individuals were not receiving the benefit. Additionally, nearly 1 million applications were rejected, with 46% denied due to income or asset issues, while the rest were rejected for documentation problems or unspecified reasons (AiREF, 2022).

In this context, we argue that Catalonia, and particularly the city of Barcelona, offers a highly relevant case for addressing our research questions. Catalonia was one of the regions that chose to supplement the new national scheme with its own regional benefit, rather than replacing one system with another. The region’s existing minimum income scheme, the Renda Garantida de Ciutadania (RGC), is well-established and functional, making it an ideal case for examining how the national system integrates with or overlaps existing regional schemes. Specifically, we contend that the presence of the RGC forces claimants to navigate the complexities of two distinct benefits, each with its own set of procedures. This dual system, characterized by notable differences and overlaps between the two programmes, resulted in significant implementation and coordination challenges (Costas and Ferrer, Reference Costas and Ferrer2022). We believe these differences in design and documented challenges make it a valuable policy scenario for testing our theoretical argument.

Data and method

Methodologically, we adopt an exploratory approach. This approach has proven effective for examining vertical and horizontal coordination between levels of governance in social policy implementation (Scalise and Hemerijck, Reference Scalise and Hemerijck2024; Ballantyne and Mascioli, Reference Ballantyne and Mascioli2024). In particular, we perform “twofold” qualitative fieldwork.

On the one hand, we conduct two specific focus groups with frontline professionals from the LWS who assist with the policy application process. More specifically, we performed “interactive” focus groups (Belzile and Öberg, Reference Belzile and Öberg2012), which involve defining research objectives before conducting qualitative work and, in our case, enhancing in-group interaction among all actors to gather a comprehensive picture of the policy process. In this context, we build on administrative burden theory and adopt Madsen et al.’s (2012) framework to guide participants through a structured sequence of steps that welfare claimants must follow. As shown in Supplementary Figure 2 (see appendix), we use a vignette-based approach to illustrate these steps within a specific model. This model outlines the tasks citizens must complete to access the IMV, from identifying themselves as potential beneficiaries to receiving the benefit or facing rejection. Participants are then asked to identify the stage where they perceive policy implementation to be most problematic. To assess the degree of administrative burden, they use colour-coded cards – red, yellow, and green – enabling us to pinpoint where burdens are most significant across different steps.

On the other hand, we perform four interviews with high-ranking officials and actors involved in the design of the IMV at the national level. In this vein, we contend that the perspectives of experts involved in policy design can enhance our understanding of the specific patterns of coordination – or lack thereof – that contribute to the generation of administrative burden. For a detailed description of the participants, please refer to Supplementary Table 1 in the annexes.Footnote 2

The selection procedure for participants involved an initial exploration of the national, regional, and local stakeholders engaged in the implementation of the IMV. To identify the primary agents responsible for welfare delivery at the local level, and more specifically, those who support welfare claimants during the application process, we mostly relied on the literature on LWS (Andreotti et al., Reference Andreotti, Mingione and Polizzi2012; Ranci et al., Reference Ranci, Brandsen and Sabatinelli2014; and others) and consulted various experts in the field. In addition, we used the database from the Institute of Government and Public Policy (UAB) on anti-poverty stakeholders in the region. The interviews were selected based on an analysis of individuals responsible for minimum income policy within the national government and state-level anti-poverty organisations.

Focus groups were conducted between April 2022 and May 2023 in Catalonia, while the four interviews with statewide actors were performed in Madrid and Zaragoza within the same period. To ensure diversity, we included a range of actors from different local governance structures, resource levels, funding models, and demographics (Edmiston et al., Reference Edmiston, Robertshaw, Young, Ingold, Gibbons, Summers, Scullion, Geiger and de Vries2022). The focus groups and interviews were conducted in person for three sessions and online for the remaining two sessions. The resulting transcripts were analysed using administrative burden theory, focusing on the elements identified by participants as the most problematic within the sequence proposed. In addition, emergent themes identified during the discussions were incorporated as part of an exploratory analysis.

All this qualitative material was produced under the European project “Euroship: Closing gaps in social citizenship”. All participants referred to in the article have given their explicit and informed consent verbally within the Euroship project, as per the ethics approval process specified by the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Empirical analysis

Following the analytical model – Figure 1 –, we divide this section into two main parts. First, we present qualitative evidence addressing the question of how upwards implicit rescaling produces administrative burdens on welfare claimants – first sequence. Second, we show the extent to which LWS helped to mitigate such burdens – second sequence – by relying not only on informal networks but also on their capacity to transfer knowledge upwards and influence the central government.

The first sequence: “Inter-institutional misfit” and administrative burden

One of the primary issues identified by both the focus groups and the interviewed experts is what we term “inter-institutional misfit,” referring to the insufficient dialogue and coordination between national and regional administrations. This lack of alignment, both in the preparatory phase and throughout the implementation process, created a burdensome experience for citizens, affecting the effectiveness of policy execution. A professional from the third-sector noted that while the IMV was quickly launched at the political level, insufficient attention was given to inter-administrative and technical discussions, as well as the limited resources of potential recipients (A1). Therefore, in this section, we aim to demonstrate that the national government did take decisions without consideration of those made before by the regions to avoid conflicts – positive coordination (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1994). Overall, we find that inter-institutional misfit manifests in significant differences in eligibility requirements between the IMV and regional schemes, as well as in varying application process requirements and timelines.

As for the eligibility requirements, such differences created considerable confusion among beneficiaries, increasing learning costs. This led to many recipients of the regional scheme to refrain from applying for the IMV due to concerns about meeting the eligibility criteria, opting instead to secure the income they currently receive from the regional scheme (A2; A4). However, most problems were in the mis-fit of specific requirements (A4). For instance, Catalonia assesses mean-testing considering income for the last 3 months, intending to adapt to sudden poverty situations. In contrast, the IMV considered income from the entire previous year, a particularly problematic approach during the COVID-19 crisis when many citizens experienced rapid income loss (A1). This problem in the design is attributed to the fact that using the previous year’s income simplifies administrative work for the Instituto Nacional de Seguridad Social (INSS; National Social Security Institute) (A5). However, this also meant that claimants were not required to provide evidence of their income if the INSS could access data from the tax agency, which compiles data for every individual after the end of the fiscal year. Paradoxically, thus, a design intended to reduce the administrative burden ended up making the program less effective, as it failed to adequately address situations of sudden poverty.

Another requirement that was reported problematic by all participants was the definition of household unit,Footnote 3 which, due to its strictness and close ties to the concept of the traditional family, imposed significant compliance costs. This requirement compelled individuals who met the income criterion but failed to meet the household unit criterion – particularly immigrants living together out of necessity without familial ties –Footnote 4 to navigate a complex administrative process to obtain a ““vulnerability certificate” from social services, which is required in such cases (A3). In this regard, frontline professionals explained that many citizens approach social services, “pleading” for certificates that validate their household unit (A7). Overall, these findings attribute high learning and compliance costs to the overwhelming amount of documentation that must be submitted to prove household vulnerability (A3; A10).

Similarly, household units needed to demonstrate a fixed residence. However, many citizens cannot provide proof of their address because they live in rented rooms and other complex situations. According to frontline professionals, it was not only the requirement itself, but also the process of navigating among administrations to deal with this requirement that generated significant administrative burden (A2). In addition, potential recipients sometimes failed to update their residency status because they did not legally change their address, even though they had done so in practice. This particularly affected young people who have a specific requirement to demonstrate that they have been economically independent for over 3 years, leading to significant compliance costs as they often fulfil all the other requirements (A1). Beyond age, the IMV is also more restrictive than the RGC (the Catalan scheme) concerning the irregular status of individuals within the household. While the IMV disqualifies the entire household if one member has an irregular status, the RGC offers greater flexibility (A8).

As noted at the beginning of the section, administrative burden has emerged not only from design differences but also from an application process that has failed to account for both regional practices and the characteristics of potential beneficiaries. In other words, the interaction between the administration and recipients varies significantly during the application process when we compare regional and national systems, which generates confusion among potential recipients. The striking example of how differences in the application process – lack of negative and positive coordination (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1994; Peters, Reference Peters2018) – can lead to learning costs is the concept of “administrative silence”:

In the RGC, administrative silence is interpreted as positive, whereas in the IMV, it is viewed as negative. This means that applicants do not receive confirmation of receipt when they submit their applications, which can result in some individuals resubmitting their requests under the assumption that their initial applications were incomplete. This miscommunication often leads to denials based on duplication. (A2)

Coordination problems also relate to different administrative timelines among distinct levels. For instance, a potential beneficiary is allotted 10 days to request and compile the necessary documentation mandated by the central administration to advance to the second phase of the application process. However, the individual must navigate multiple state-level, regional, and local administrations to gather such documentation, each of which operates by appointment and adheres to varying processing times that often exceed the stipulated 10-day period (A2). Therefore, significant learning and compliance costs emerge from trying to meet this requirement, which social policy scholars have also termed “temporal costs” (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Currie and Podoletz2024) and that in this case is a consequence of contradictions among administrative levels (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1994; Peters, Reference Peters2018). In any case, a third-sector worker also noted that the administrative burden primarily stemmed from the national scheme, as the RGC, being more established and operational for a longer period, functions more efficiently (A1).

In another note, the initial months of implementation were particularly difficult due to the fully digital nature of the application process instituted during the pandemic in 2020. While the regional application process had a clear structure and adequate personnel resources, frontline professionals noted that the new online application process generated additional administrative burden. This was attributed to the use of specialised language, the requirement for an email address, and the need to obtain further documentation at other administrative levels, also through digitals means (A1). Indeed, although the central government acknowledges sending text messages to eligible citizens, they note that the majority fail to respond due to a digital gap (A11).

Consequently, it seems that the problem was not that individuals failed to recognise themselves as potential recipients; rather, the challenge laid in the fact that when they attempted to apply, they encountered various obstacles that hindered their ability to proceed with the application – as the central administration provided no individualised support throughout the process (A1; A10). In this light, we find that policymakers assumed that potential claimants possessed certain computer skills, such as the ability to compress PDF files to meet the 30-megabyte upload limit, use the Spanish electronic ID (Cl@ve), or install a valid electronic certificate on a computer (A2; A1). Moreover, it is assumed that potential recipients possess a personal computer and a reliable internet connection, which is often not the case. As well, the application process is not optimised for use on mobile phones, which serve as the primary ICT devices for many vulnerable groups (A10).

These issues highlighted by frontline professionals from the LWS align with the existing literature underscoring how digital procedures disproportionately affect vulnerable populations (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Lindgren and Melin2022a; Lindgren et al., Reference Lindgren, Madsen, Hofmann and Melin2019) and, more in particular, minimum income claimants (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Currie and Podoletz2024). Older adults and individuals with limited resources and lower human capital often lack the necessary knowledge, training, and executive functions required to effectively navigate application processes, making professional assistance essential to overcome these barriers (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Aarøe, Baekgaard, Herd and Moynihan2020). In this context, LWSs have played a vital role in facilitating the application process because the most vulnerable claimants frequently rely on local social services and third-sector professionals to access the IMV. However, third-sector workers report significant psychological costs stemming from difficulties in understanding the application process, slow or inefficient ICT systems, and poorly designed, uninformative web interfaces, advocating for a platform that allows recipients to track the status of their applications (A1; A3).

Against this background, LWSs observe that when dealing with vulnerable families, these often experience substantial emotional and stress-related burdens. Applying for assistance, which typically amounts to just over 400 euros, involves a complex administrative process that leaves applicants feeling disempowered (A10). Many require continuous support from someone who can guide them through the process: reading documents, understanding their financial situation, managing identification requirements, and handling personal information. This significant administrative burden exacerbates their existing challenges, leading to considerable fatigue and causing many to abandon the process before completing it (A10).

Coordination in the aftermath: The “Boomerang Effect” and vertical and horizontal responses

The second sequence is characterised by institutional and local responses to the administrative burden generated. Overall, however, deficient top-down communication channels between administrative levels prevailed (A8). Indeed, no specific contacts were established between administrations, and frontline professionals had to reach the central administration through the general phone line and an email address that provided to all citizens (A9).

Not only were channels not guaranteed, but also a significant workload also emerged for LWSs, highlighting that the state level was unprepared to effectively implement the policy. In this light, we identified a “boomerang effect,” referring to the return of a large number of IMV administrative records to the local level, which cannot be managed at the national level. As for this “boomerang effect,” the main concern of LWS actors is that the policy implementation has taken place at an administrative level – national – that is neither prepared nor equipped with the human resources necessary to take responsibility for policy implementation in this policy domain (A2). This, in turn, has led to a spillover of workload downwards to regional and local administrations. Regarding this, the coordinator of the law’s design argued that it is “natural” for social vulnerability situations to be addressed more locally, where actors are better attuned to these individuals and can more easily track them (A14). In this line, he argued that INSS lacks social workers at the national level to assess emergency needs or support the application process (A14). However, the assumption that “the state need not take responsibility” seems to have led to unintended consequences, as we show below.

An illustrative example of this spillover is the case of the Basque Country. When this region took over the direct management of the IMVFootnote 5 following a downward transfer of competences in 2022, it received over 20,000 unresolved IMV applications (A13). This resulted in a significant backlog in the region, prompting the need to hire temporary staff to address the situation, which has been stabilised 2 years later (A13). Similarly, frontline professionals from the LWS report that when the INSS has an excessive workload, it delegates case management to other regional offices across Spain. This disrupts the established channels between local interlocutors, as requests for certificates from social services to prove vulnerability – among other requests – come not only from Catalonia, but also from potential beneficiaries in other regions, resulting in confusion and overload at the local level (A3).

Overall, no coordination has resulted in an overwhelming workload that “cascades down” to the LWS (A1; A3). In this line, they argue that local administrations are required to take on the economic and personnel responsibilities for a situation that “should fall under the remit of the central administration” (A3). While local administrations may be willing and have the discretion to support welfare recipients, they argue that they cannot bear the full responsibility of welfare state functions – such as education, healthcare, and housing – that other levels of government are reluctant to address (A3). This issue is particularly severe in small- and medium-sized cities, which often have fewer resources, making it difficult to provide the necessary technical support and meet residents’ needs (A1; A10).

Furthermore, policy responses to address this situation have remained uncoordinated. For example, the central government approved in 2021 the Decreto de Entidades Mediadoras to enable private actors – such as third-sector organisations – to assist potential beneficiaries during the application process as a response to implementation issues. However, while the RGC allows these actors to provide support and certify situations of social vulnerability, the IMV restricts this function to organisations operating at the state level. Consequently, approximately 3000 organisations were excluded from mediating these functions in Catalonia, as they are legally restricted to operating at the regional level (A2).

Despite the lack of vertical coordination, LWSs have also found (horizontal) ways to reduce learning and compliance costs of minimum income claimants. In particular, frontline professionals have established their own horizontal strategies to lessen the impact of (poor) policy implementation. The most illustrative example is the XARSE initiative, a service established by the Barcelona City Council’s Neighbourhood Plan in 2020 to support individuals who struggle to independently apply for public financial aid – and in particular to the IMV. One of the coordinators explained that they have created a new channel to address stalled applications: in many cases, when assisting an individual who, due to the type of documents they have, cannot submit an online application but is still eligible for the benefit, they facilitate the contact with the social affairs offices – managed by the regional administration – to expedite the application process (A4). At the same time, other frontline professionals from the LWS reported using informal channels and personal connections with public institutions to address specific situations (A1; A7). For instance, third-sector professionals have worked closely with the Institut Municipal de Serveis Socials, from the local government, exchanging necessary documents and requests (A9).

Not only did LWSs intervene to reduce the administrative burden, but anti-poverty organisations (such as Cáritas) at the national level also contributed through other ways. Specifically, one of the main responsible within this organisation explained that the government introduced several policy changes following a key meeting between the parties. In this line, the government accepted some changes that were among the top priorities as they addressed some of the eligibility requirements that were generating administrative burden – for example, registration, address, and the definition of the household unit, among others – (A12).

Conclusions

This article has investigated how implicit welfare rescaling contributes to the administrative burden faced by welfare claimants, and in what ways does the (lack of) coordination between administrative levels impact their experiences. In addition, it assessed to what extent horizontal actors helped to recognise the burdens placed on citizens, and what measures they took to alleviate them. To do so, we built an original analytical model by bringing together literature on MLG and administrative burden theory. The model proposes that, in multi-level systems, restructuring service provision through poor coordination across administrative levels can impose substantial learning, compliance and psychological costs on benefit claimants, hindering welfare access. The article tests this argument in the context of Spain, specifically examining the (failed) implementation of the IMV (2020–2022).

The qualitative findings confirm that the model proposed is a useful conceptual tool to evaluate policy implementation. We reveal that the implementation of the IMV led to a complex and inconsistent distribution of responsibilities among levels of government, disrupting an established regional welfare system and generating new administrative burdens for potential beneficiaries. We found that the national government overlooked the unique characteristics, resources, and needs of the targeted population in both the design and application form/process of the IMV. In addition, it also failed to account for the significant differences between the IMV and regional schemes in these two areas during the policymaking process, reflecting a lack of positive coordination, as described by Peters (Reference Peters2018). As a result, individuals faced substantial learning, compliance, and psychological costs during the application process, leading to incomplete enrolments and a high number of dropouts. A good example of the lack of positive coordination is the 10-day window provided by the central administration to request and gather the necessary documentation for advancing to the second phase of the application process. Individuals had to navigate various state, regional, and local administrations, each with different appointment systems and processing times, often exceeding the 10-day limit.

The findings also suggest, however, that when uncoordinated institutional changes take place, LWSs appear to play a crucial role. Used to deal with policy implementation, we find that they help claimants manage learning and compliance costs through formal and informal channels, even if under-resourced and beyond the scope of their competencies.

The second contribution of this article is to the social policy literature in Southern Europe. It provides further evidence of the relevance of the territorial dimension of social policies, which, although long neglected in comparative social policy analysis, has been increasingly recognised since Kazepov’s work (2008; 2010). In particular, the article contributes to a growing body of research that has recently identified coordination challenges within multi-level policy settings in Southern countries, which have hindered successful policy implementation in areas such as long-term care in Italy and Spain (Arlotti and Aguilar, Reference Arlotti and Aguilar2018; León et al., Reference León, Arlotti, Palomera and Ranci2023), social inclusion services for minimum income beneficiaries (Soler-Buades, Reference Soler-Buades2025), and childcare services delivery in Barcelona (Scalise and Hemerijck, Reference Scalise and Hemerijck2024), among others.

We believe that building on the empirical findings of this article and the referenced research can help policymakers navigate and overcome the multi-level challenges encountered in past programmes. Future reforms should consider that shifting more power to the national administration and reorganising policy responsibilities may undermine policy progress unless coordination with subnational units and LWSs is carefully managed. In particular, we posit that while vertically designed policies – grounded in adherence to norms and aimed at standardized, equal implementation for all – may ensure consistency and reduce territorial inequalities, they can also have a negative impact on both citizens’ experiences and overall policy effectiveness. One way governments can address this is by leveraging the expertise of local actors to identify individuals’ needs, skills, and resources, thereby designing more targeted, inclusive, and effective policies.

While this study provides a new conceptual tool for analysing policy implementation in multi-level systems, it also has some limitations. The main limitation is likely the generalisation of our results to other territories. As explained, regions have either replaced or adapted their regional schemes to align with the IMV. This article focuses on the latter to address our research questions. However, further research is needed to assess the IMV’s implementation in regions where it has replaced the regional scheme, as the process and policy problems in those areas may have differed.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/ics.2025.10039.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their colleagues at the Institute of Government and Public Policy (UAB), participants in the IX Conferencia Red Española de Política Social (REPS – ESPAnet Spain) held in Palma (2023), participants in the Workshop INCOME-INN organized by the GSADI-UAB research group, and the editors of the Special Issue “Social Policy Implementation in Latin America and Southern Europe: Failures, Breakthroughs, and Challenges in the Provision of Social Protection” for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article. The authors are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments, which significantly enhanced the final manuscript. This research was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No. 870698 (EUROSHIP: Closing Gaps in Social Citizenship). The authors’ arguments published on this website reflect only the author’s view. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.