Optimizing research-to-practice translation using implementation science

Implementation science has rapidly expanded over the past 25 years to improve the efficiency of research-to-practice translation. The field initially focused on conceptualizing implementation outcomes as distinct from clinical and service outcomes [Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan1]. Early work centered on identifying implementation barriers and strategies to overcome them (e.g., training and facilitation). Today, there is growing emphasis on mechanisms of implementation strategies (i.e., how, why, and when they work) [Reference Lewis, Klasnja and Powell2]. For innovations (i.e., pharmaceuticals, psychosocial interventions, and policies) to reach populations equitably and close the lengthy research-to-practice time lag, new approaches were needed to ensure that innovations are scaled while maintaining effectiveness. Hybrid studies, including type 1, type 2, and type 3 effectiveness-implementation studies [Reference Curran, Landes and McBain3], and more recently, DIeSEL (Dissemination, Implementation, effectiveness, Sustainment, Economics, and Level-of-Scaling) hybrid studies [Reference Garner4], have been codified to fill this need. However, limited guidance exists for generating insights about implementation in efficacy (i.e., whether the intervention works in ideal settings) or effectiveness (i.e., whether the intervention works in practice) stage hybrid trials. Optimizing hybrid studies as early as possible in the research translation continuum to produce strategic knowledge about the innovation and its implementation has potential to improve the efficiency of research translation, and ultimately, societal impact.

Effectiveness-implementation hybrid studies

Carroll and Rounsaville (2003) first proposed that elements of intervention efficacy and effectiveness research be blended into a hybrid model to prepare for “real-world” application [Reference Carroll and Rounsaville5]. For example, they explained that teams might consider retaining randomization necessary for establishing intervention efficacy but diversify the delivery context or expand patient inclusion criteria to enhance generalizability. Curran et al. advanced this hybrid concept further by introducing effectiveness-implementation hybrid studies [Reference Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne and Stetler6]. Indeed, with complexities of the health and social care system, and the frequent co-occurrence of biopsychosocial conditions throughout populations, scientists and healthcare professionals must rethink how we approach the research that ultimately impacts patient care.

Hybrid effectiveness-implementation studies include both an intervention effectiveness aim and an implementation aim in one study. A type 1 hybrid study is primarily focused on examining the effectiveness of an intervention on patient outcomes (e.g., symptoms, functioning) while also considering factors bearing on its implementation potential [Reference Curran, Landes and McBain3]. A type 2 hybrid usually has co-primary aims simultaneously examining the effectiveness of an intervention on patient outcomes and the effectiveness of the implementation strategy or strategies on implementation outcomes. A type 3 hybrid study is focused on examining the effectiveness of implementation strategies on implementation outcomes, while also gathering intervention effectiveness data.

Notably, hybrid studies have been recommended for use after the efficacy of the intervention has been established [Reference Curran, Landes and McBain3]. This recommendation stems from the requisite that the intervention has demonstrated safety and unintended consequences have been investigated. Nevertheless, the progression from efficacy to effectiveness is not necessarily linear or distinct, particularly for social, behavioral, and policy interventions [Reference Carroll and Rounsaville5,Reference Glasgow, Lichtenstein and Marcus7]. Further, following the status quo research translation paradigm using linear progression from efficacy testing through pragmatic dissemination and implementation trials has resulted in the slow or no translation of interventions into practice settings, as well as reduced effectiveness as the intervention moves through the research-to-practice translation continuum [Reference Chambers, Glasgow and Stange8]. With this inception of a much-needed scientific modernization, and long-overdue prioritization of health equity, social justice, and resource efficiency, we recommend consideration of dissemination, implementation, and sustainment by intervention trialists as early as possible in the research-translation continuum, including during efficacy testing. We contend that implementation can and should be investigated during the efficacy testing stage, and hence, these studies should be specifically designated as hybrid type 1 efficacy-implementation studies.

Hybrid type 1 studies

Hybrid type 1 studies can be designed more rigorously to accelerate research-to-practice gaps and enhance pragmatic application. Opportunities exist to introduce implementation during intervention efficacy testing stages. For example, guided by the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance framework (RE-AIM) [Reference Glasgow, Harden and Gaglio9], Bartholemew et al. used a type 1 hybrid study to investigate efficacy (rather than effectiveness) and implementation of the Comprehensive-TeleHarm Reduction intervention for increasing engagement in HIV prevention care [Reference Bartholomew, Plesons and Serota10].

Much more knowledge about implementation can be gained from more rigorously designed type 1 hybrids than what is currently being generated. Existing applications of type 1 hybrids generally focus on assessing determinants (i.e., What are the barriers and facilitators to implementation?) and perceptions about the intervention (i.e., Is the intervention acceptable?). These types of research questions likely stem from existing recommendations [Reference Curran, Landes and McBain3], published study examples, and/or insufficient availability of implementation research expertise in the workforce.

Advancing type 1 hybrid studies

The growth of implementation research across diseases and conditions, contexts, and populations, as well as continual advancements to implementation concepts, necessitate boundary-pushing to keep pace with scientific developments and complexities of healthcare and patient needs. More recently, type 1 hybrid studies have started to investigate specific implementation determinants, like implementation climate, readiness for change, and innovation-values fit [Reference Garner, Burrus and Ortiz11], which could be key mechanisms used to inform implementation strategy selection or refine implementation strategies to test in subsequent hybrid studies. Furthermore, although hybrid studies are distinct from pragmatic trials, key conceptual alignments can be leveraged for complementarity in efficacy stages. Specifically, type 1 hybrids include purposeful evaluation of implementation outcomes and contextual determinants, while pragmatic trials test interventions in the contexts where they are meant to be delivered, for example by leveraging existing personnel to deliver the intervention within the greater system and processes of care. Notably, the PRagmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS-2) Tool [Reference Loudon, Treweek, Sullivan, Donnan, Thorpe and Zwarenstein12] can be used to design more pragmatic type 1 hybrid studies that leverage key delivery domains important for real-world application (e.g., broader patient inclusion criteria, flexibility in intervention delivery, existing organizational resources), while also examining implementation outcomes and specific theory-driven contextual determinants. In turn, this could lead to optimized type 2 hybrid studies that test implementation strategies and expedite the research-to-practice pipeline.

We assert that teams should work alongside healthcare providers, community partners, and patients to design interventions focused on equitability, which could reduce access and implementation barriers at later stages of research translation. Further, teams should design interventions to align with capacities, goals, needs, and values of the target setting and packaged for more effective dissemination to target audiences [Reference Garner, Burrus and Ortiz11,Reference Kwan, Brownson, Glasgow, Morrato and Luke13]. Moving beyond the design stage, engagement with partners should continue throughout the study to assess setting-intervention fit and contextual determinants that may impact intervention effectiveness and use, particularly given the dynamic nature of the implementation context. Furthermore, theories remain underutilized across intervention and implementation research. Implementation (e.g., Theory of Implementation Effectiveness) or classic theories (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior) can guide more precise implementation aims and hypotheses that explain how and why phenomena occur [Reference Nilsen14]. By grounding implementation aims in theory, type 1 hybrid studies can advance the science of implementation through theory building, enhance generalizability of the phenomena to other contexts, and inform preliminary causal models of implementation process mechanisms [Reference Lewis, Klasnja and Powell2,Reference Nilsen14,Reference Weiner, Lewis and Linnan15].

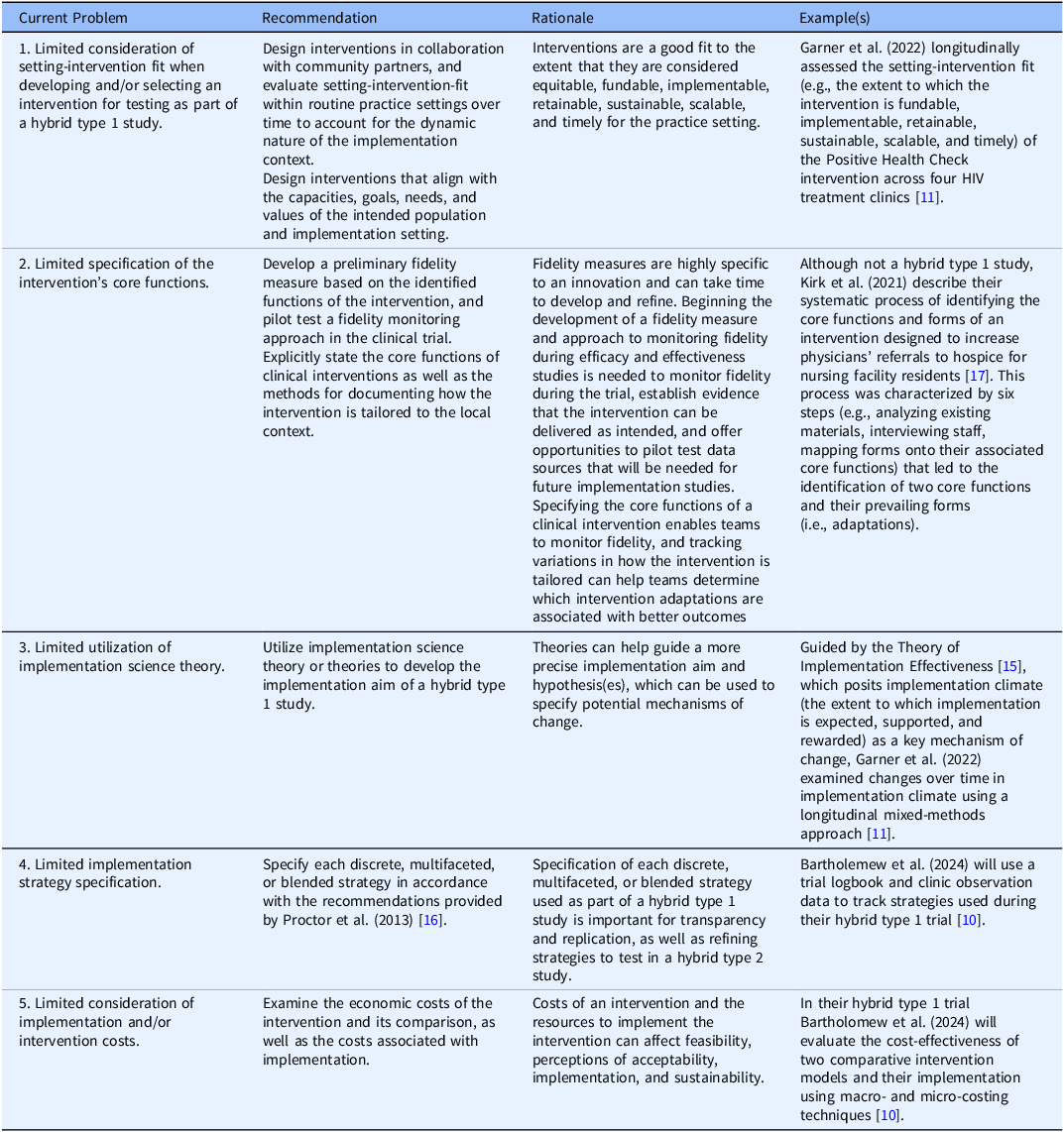

Further, intervention trialists often use implementation strategies during efficacy and effectiveness trials (i.e., training, audits, feedback) without acknowledging or reporting these strategies, which prohibits replicability [Reference Proctor, Powell and McMillen16] or delays testing specific strategies to improve implementation, sustainment, and scale-up. In Table 1, we provide new, specific recommendations for maximizing type 1 hybrid studies based on the implementation science literature.

Table 1. Recommendations for hybrid type 1 efficacy and effectiveness-implementation studies

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Kathryn Hyzak: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Alicia Bunger: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing-review & editing; Lisa Juckett: Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing; Daniel Walker: Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing; Bryan Garner: Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing.

Funding statement

A.C.B efforts were supported in part by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences awarded to the Clinical and Translational Science Institute of The Ohio State University (#UM1TR004548).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.