Introduction

The role of family/friend caregiversFootnote 1 and the impact of caregiving on their own lives have been well documented prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is well acknowledged that caregivers provide much of the support needed by older adults experiencing loss of autonomy, for example, by providing direct support for the daily activities or monitoring health follow-ups (Bom et al., Reference Bom, Bakx, Schut and van Doorslaer2019; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Paul, Fahy, Dowling-Hetherington and Lafferty2020). In Canada, 7.8 million Canadians aged 15 and over are caregivers, which represents one quarter of the Canadian population (Statistics Canada, 2020). Caregivers perform a variety of tasks that differ in length of time, intensity, and degree of emotional and physical demands. These tasks may include medical care, emotional support, and assistance with household tasks (e.g., errands, transportation, medical appointments, meals, and cleaning). According to the 2018 General Social Survey – Caregiving and Care Receiving, most caregivers (64%) spent less than 10 hours a week on caregiving responsibilities, but 15% spent 10–19 hours and 21% spent 20 hours or more (Statistics Canada, 2020).

Caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic

As a result of the public health guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic, many older adults have had to significantly adjust their daily behaviours to avoid social gatherings and restrict physical contact to only a few individuals. This has impacted not only older adults but also their caregivers and other family members. At the beginning of the pandemic, caregiver roles and tasks changed drastically. Learning new tasks (wearing personal protective equipment and providing care that would otherwise have been given by a care attendant, such as giving medication) and following strict restrictions for fear of transmitting the virus were reported to increase caregiver stress, burden, and social isolation (Hanna et al., Reference Hanna, Giebel, Tetlow, Ward, Shenton, Cannon, Komuravelli, Gaughan, Eley, Rogers, Rajagopal, Limbert, Callaghan, Whittington, Butchard, Shaw and Gabbay2021; Hindmarch et al., Reference Hindmarch, McGhan, Flemons and McCaughey2021; Nash et al., Reference Nash, Harris, Heller and Mitchell2021; Tsapanou, Zoi, et al., Reference Tsapanou, Zoi, Kalligerou, Blekou and Sakka2021).

Caregivers’ psychosocial well-being, particularly during lockdown periods, was significantly impacted. Caregivers expressed that it was physically, emotionally, and financially more difficult to care for older adults with limitations during confinement (Cagnin et al., Reference Cagnin, Di Lorenzo, Marra, Bonanni, Cupidi, Laganà, Rubino, Vacca, Provero, Isella, Vanacore, Agosta, Appollonio, Caffarra, Pettenuzzo, Sambati, Quaranta, Guglielmi, Logroscino and Bruni2020; Lightfoot, Moone, et al., Reference Lightfoot, Moone, Suleiman, Otis, Yun, Kutzler and Turck2021). For caregivers and care recipients, lockdowns restricted social and physical interactions, which increased levels of social isolation, stress, and anxiety (Borges-Machado et al., Reference Borges-Machado, Barros, Ribeiro and Carvalho2020; Lightfoot, Yun, et al., Reference Lightfoot, Yun, Moone, Otis, Suleiman, Turck and Kutzler2021; Nash et al., Reference Nash, Harris, Heller and Mitchell2021). Some studies reported on the specific challenges of persons caring for individuals with dementia. Many caregivers felt that dementia-associated psychological and behavioural symptoms worsened due to social isolation; hence, their caregiver stress became more pervasive (Altieri & et Santangelo, Reference Altieri and Santangelo2021; Borg et al., Reference Borg, Rouch, Pongan, Getenet, Bachelet, Herrmann, Bohec, Laurent, Rey and et Dorey2021; Cagnin et al., Reference Cagnin, Di Lorenzo, Marra, Bonanni, Cupidi, Laganà, Rubino, Vacca, Provero, Isella, Vanacore, Agosta, Appollonio, Caffarra, Pettenuzzo, Sambati, Quaranta, Guglielmi, Logroscino and Bruni2020; Roach et al., Reference Roach, Zwiers, Cox, Fischer, Charlton, Josephson, Patten, Seitz, Ismail and Smith2021; Tsapanou, Papatriantafyllou, et al., Reference Tsapanou, Papatriantafyllou, Yiannopoulou, Sali, Kalligerou, Ntanasi, Zoi, Margioti, Kamtsadeli, Hatzopoulou, Koustimpi, Zagka, Papageorgiou and Sakka2021).

Some caregivers also reported feelings of guilt for not being able to care for their loved one, either from fear of transmitting the virus or due to restrictions imposed by the residence of their loved one (Tsapanou, Zoi, et al., Reference Tsapanou, Zoi, Kalligerou, Blekou and Sakka2021) knowing that their absence would have a direct impact on their loved one’s well-being and the care they received (Dementia Society, 2020; Schlaudecker, Reference Schlaudecker2020). In fact, restricted visits in residences and a lack of staff to compensate for the support previously provided by family members resulted in some individuals bringing the care recipient into their own home during this period (Nash et al., Reference Nash, Harris, Heller and Mitchell2021).

The Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (2020) emphasizes that caregivers should be recognized as partners of health care organizations. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that this was not yet the case in the spring of 2020, when caregivers were denied contact with their loved ones in care facilities. Although confinement rules were later modified when it became clear that the presence of caregivers was necessary for the well-being of the frail older adults, this period was filled with uncertainty for caregivers.

Caregivers living in an official language minority community (OLMC)

Being a member of a minority language group can have an impact on the role of the caregiver. Research has previously demonstrated the negative impact of language barriers on access to health and social services, satisfaction and experience of care recipients, and disparities in access to care between members of OLMCs (de Moissac & Bowen, Reference de Moissac and Bowen2017, Reference de Moissac and Bowen2019; Drolet et al., Reference Drolet, Bouchard, Savard, Laforge, Drolet, Bouchard and Savard2017; Timony et al., Reference Timony, Gauthier, Wenghofer and Hien2022). In Canada, English is the majority official language spoken in all provinces and territories, except for the province of Quebec, where French is the majority official language (Canada Council for the Arts, n.d.)Footnote 2. Drolet et al. (Reference Drolet, Arcand, Benoît, Savard, Savard and Lagacé2015) noted that Francophone caregivers living outside of Quebec have difficulty obtaining services in the language of their loved ones. Similarly, in New Brunswick, the only officially bilingual province, Dupuis-Blanchard et al. (Reference Dupuis-Blanchard, Gould, Gibbons, Simard, Éthier and Villalon2015) and Simard et al. (Reference Simard, Dupuis-Blanchard, Villalon, Gould, Ethier and Gibbons2015) noted that due to the difficulty in accessing health and social services in their first language, Francophones in minority situations often rely on their caregivers to accompany them in their interactions with English-speaking staff, placing an additional burden on their caregivers.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, loosening of language obligations in public institutions and governments was observed (Chouinard & Normand, Reference Chouinard and Normand2020). It is not known how this can have impacted caregivers.

Objectives and research questions

In 2020, gaps had been identified in the scientific literature pertaining to caregiver needs (WHO, 2020) and how to best support them during the pandemic (Onwumere, Reference Onwumere2020). Since then, many studies have been published on the immediate impact of the confinement. Our research team was interested in the continued impact of this event, up to two years after the pandemic onset, on caregivers of older Canadian adults living at home.

The main objective of this research was to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Canadian caregivers of older adults living at home in Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick and determine whether belonging to an OLMC had an influence on caregivers’ experiences. We focused on these four provinces as they have a high proportion of official language minority population (Statistics Canada, 2021). The specific objectives were:

-

• To identify changes experienced by caregivers following the COVID-19 pandemic with regard to the assistance provided to an older adult, support received, and psychological well-being of the caregiver, up to two years after the pandemic onset.

-

• To examine the impact of belonging to an OLMC on these variables.

The research questions were:

-

• What impacts on caregiving, support received, and caregiver psychological well-being are experienced by caregivers of older adults living at home after the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada?

-

• What is the influence of sociodemographic variables on the well-being of caregivers?

-

• Are there differences between caregiver–recipient dyads from OLMC and those from the official language majority community on these variables?

Methods

A mixed methodological approach (quantitative and qualitative) was adopted to collect data on the impact of COVID-19 on caregivers of older adults living at home and to better understand the experience of these caregivers. An advisory committee consisting of researchers and representatives from eight partner organizations (caregiver support organizations, older adults’ associations, and French-language health organizations) was involved in all stages of the project. Ethics approval was received from the university research ethics boards for all research team members.

Recruitment

Participant recruitment was done through convenience and snowball sampling. The research team, with the assistance of project partners, recruited participants by sharing the invitation through their respective contact networks, social media, and newsletters, with the research team also disseminating the invitation within their community. Some researchers also participated in radio interviews to talk about the research project, which served as a recruitment outreach. Caregivers of both official languages were included if they were caring for an older adult who was living at home or in an independent living residence during the pandemic, if they resided in New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, or Manitoba, if they were able to provide informed consent, and if they were able to complete a questionnaire online or by telephone. We excluded caregivers of older adults living in assisted living accommodations (e.g., nursing homes and long-term care homes) at the beginning of the study, as we were aware of other research studies being conducted with this population.

Data collection

Phase 1: Caregivers from the four provinces completed an initial online (Survey Monkey) or telephone questionnaire, between the fall of 2021 and the winter of 2022. The questionnaire included questions developed by the research team, inquiring about (1) the caregiver’s and older adult’s sociodemographic profile; (2) their health status; (3) the older adult’s living situation (whether the older adult lived in a personal home, with or without the caregiver, in an independent living facility, etc.); (4) the caregiver’s and older adult’s language preference; (5) the caregiver’s role and responsibilities prior to the onset of the pandemic (answered retrospectively), during the strictest lockdown periods (answered retrospectively), and as of the date of the questionnaire response; and 6) the language of services received by the older adult. The two versions of the questionnaire (French and English) were pretested with three caregivers who provided feedback that helped simplify some questions. In addition, the questionnaire included three validated scales.

The 12-item Zarit Burden Questionnaire (Bédard et al., Reference Bédard, Molloy, Squire, Dubois, Lever and O’Donnell2001) was used to measure caregiver burden. This version has an excellent internal consistency (α =0.88) and excellent correlations (r = 0.92–0.97) with the widely used 22-item version (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Orr and Zarit1985). Higher scores on the Zarit Burden Questionnaire indicate a greater sense of burden. The short form scores can be interpreted as follows: less than 3 = low burden or below the 25th percentile and 18 and over or 17 and overFootnote 3 = extremely high or over the 75th percentile, with a maximum possible score of 48 (Bédard et al., Reference Bédard, Molloy, Squire, Dubois, Lever and O’Donnell2001; Hébert et al., Reference Hébert, Bravo and Préville2000). Moderate and high burden levels (above 10) have been found to be predictive of depressive symptoms (O’Rourke & Tuokko, Reference O’Rourke and Tuokko2003).

The 6-item de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, Reference de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg2006; de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, Reference de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg2010) was used to measure caregivers’ feeling of loneliness. The items have three response categories: ‘no’, ‘more or less’, and ‘yes’. Three items indicating feelings of loneliness are dichotomized as ‘more or less’ and ‘yes’ = 1 indicating loneliness and ‘no’ = 0 indicating its absence, while the three items indicating social support are dichotomized as ‘no’ and ‘more or less’ = 1 indicating loneliness and ‘yes’ = 0, for a possible maximum score of 6, where 6 indicates a greater sense of loneliness (de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, Reference de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg2010). The scale’s internal consistency is demonstrated with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.64 to 0.77 (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Parmar, Dobbs and Tian2021; de Jong Gierveld et al., Reference de Jong Gierveld, Keating and Fast2015; de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, Reference de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg2006). Mean loneliness scores were found to be lower in the Canadian aging population (mean 1.27; de Jong Gierveld et al., Reference de Jong Gierveld, Keating and Fast2015) than in other countries (mean ranging from 1.56 to 2.80; de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, Reference de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg2010).

Caregivers’ perception of social support was measured with the 6-item Medical Outcome Study (MOS) Social Support Survey (Holden et al., Reference Holden, Lee, Hockey, Ware and Dobson2014). Construct validity of this abridged version was demonstrated, and a strong correlation was found with the original MOS (Sherbourne & Stewart, Reference Sherbourne and Stewart1993). The 6-item MOS has a 5-point Likert response scale for a maximum possible score of 30. Higher scores on the MOS Social Support Scale indicate greater social support. A median score of 26 out of 30 is reported by Holden et al. (Reference Holden, Lee, Hockey, Ware and Dobson2014) in a cohort of Australian women aged 53–58.

Phase 2: These same respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire a second time (without the sociodemographic profile and the retrospective questions) six months later, between April 2022 and August 2022.

Phase 3: At the end of the second questionnaire, OLMC respondents were invited to participate in a semi-structured individual interview, via videoconference or telephone. The interviews focused on the caregivers’ experience of care before the pandemic, during periods of strict lockdown, and at the time of the interview, as well as their ideas about how the health and social system could have better met their needs. They also allowed validation of our understanding of the questionnaire data. The interviews lasted approximately 45–60 minutes, were recorded, and were transcribed in their entirety.

Quantitative data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sociodemographic characteristics. Frequencies were reported for caregiver visits, types of care and support provided by caregivers, care recipient community services, and supports for caregivers over four time periods: (1) pre-COVID-19 before March 2020, (2) COVID-19 lockdowns (March 2020 to Fall 2021)Footnote 4, (3) October 2021 to February 2022, and (4) 6-month follow-up from April 2022 to August 2022.

Frequencies were reported for the perceived impact of the pandemic on physical, mental, and cognitive health, at initial and 6-month follow-up questionnaires. The perceived impact was dichotomized as ‘yes’ or ‘no’ negative impact. The non-parametric McNemar–Bowker test for paired samples was used to test differences in the proportions between initial questionnaire and 6-month follow-up.

Frequencies were reported for changes in total scores between initial and 6-month follow-up questionnaires for burden, loneliness, and social support scales. Changes in total scores were categorized as follows: ‘decreased’ if scores were lower by 10% or more, ‘stable’ if scores were plus or minus 10%, and ‘increased’ if scores were higher by 10% or more. A paired sample t-test was used to test differences in mean total scores between initial and 6-month follow-up.

Correlations and multiple linear regression were used to examine associations between sociodemographic characteristics and caregiver burden scores at the 6-month follow-up questionnaire. Explanatory variables included age group (<60 years versus 60+ years), education level (university versus college, technical, or secondary), professional status (employed full-time, part-time, or student versus unemployed or retired), household gross income (<$100,000 versus $100,000+ [Can]), working in health care currently or in the past (yes versus no), and caregiver or recipient belonging to an OLMC (yes versus no). A caregiver–recipient dyad belongs to an OLMC if either one self-identifies that their main official language spoken is not the majority language in their province or territory.

Statistical significance was considered at the alpha level of .05, with two-tailed tests and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) provided for tests. Analyses were conducted using SPSS® 28.0 statistical software.

Qualitative data analysis

A thematic analysis approach based on the types of annotations described by Paillé and Mucchielli (Reference Paillé and Mucchielli2008) was used. The verbatim quotes were sorted using the NVivo 13 analysis software. Content analysis first allowed the overall meaning of the corpus to be extracted and then deconstructed to identify specific emerging phenomena. A research assistant and a senior research associate coded the interview data according to a predetermined procedure: (1) The research assistant and research associate did an initial reading and coding of one interview together; (2) they separately coded two other interviews with the goal of identifying headings (a general annotation that describes what is discussed in the corpus excerpt) and emerging themes (an annotation that specifies what is discussed in the excerpt) (Paillé & Mucchielli, Reference Paillé and Mucchielli2008); (3) they met for approximately 1 hour to go through the three coded interviews and reach a consensus on the headings and themes; (4) this initial coding scheme was presented and discussed with the research team to obtain their feedback; (5) the research assistant coded the rest of the data according to the identified code list, while allowing for the emergence of new codes; (6) the research assistant and research associate met on two occasions to finalize the list of codes and their definitions; and (7) the final code list was validated with the research team. The entire coding and validation process took place between autumn 2022 and spring 2023. Thus, the category grid was based on the inter-judge and consensus method. Data were analysed deductively and inductively, through an iterative process, to progressively clarify emerging themes related to the experience of caregivers, challenges they faced during the pandemic, and possible facilitating factors, in a specific context. To increase analysis trustworthiness, interview data were also triangulated with the quantitative questionnaire data, and data analysis was validated with the research team during two group meetings. Although we did not reach the desired number of interviews, data saturation seems to have been reached, as the last interviews that were analysed did not lead to any new codes.

Qualitative comments from all questionnaire participants were coded deductively using the same codes and definitions.

Results

Questionnaire participants

In total, 164 caregivers completed the initial questionnaire, of which 83 also completed the 6-month follow-up questionnaires (50.6% response rate) and are included in the present analysis. Note that the second questionnaire was not sent to 18 caregivers who indicated that the older adult they cared for during the pandemic had recently died.

Caregiver sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Caregivers were predominantly women (88.0%) and in the age groups of 60–69 years (32.5%) and 50–59 years (28.9%). The majority were unemployed or retired (51.8%), although many were working full-time or part-time (43.4%). Most were providing care to their mother, father, or parents-in-law (68.7%).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of caregivers who completed both the initial and 6-month follow-up questionnaires (n = 83)

Abbreviations: CAD = Canadian dollar; OLMC = official language minority communities.

Post hoc comparisons were performed using standardized differences (std. diff.) of sociodemographic characteristics between caregivers who completed both the initial and 6-month follow-up questionnaires (n = 83) and caregivers who completed only the initial questionnaire (n = 81). The only statistically significant difference was for the province of residence. Among caregivers who completed both questionnaires, fewer were from Quebec (32.5% versus 50.6%, std. diff. = .37) and more were from New Brunswick (15.7% versus 6.2%, std. diff. = .37).

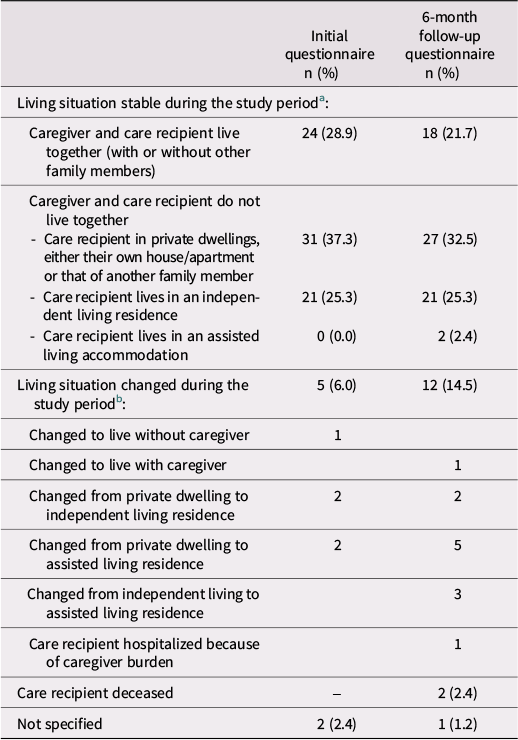

As shown in Table 2, most caregivers were not living with the care recipient. As time passed, a certain number of care recipients moved to facilities where they could receive more care.

Table 2. Living situation at initial and 6-month follow-up (n = 83)

a The study period means:

-

- For the initial questionnaire: from the onset of the pandemic to the initial questionnaire

-

- For the follow-up questionnaire: from initial to follow-up questionnaire.

b In the initial questionnaire, a response option was as follows: their place of residence changed during the pandemic or recently (please specify). In the follow-up questionnaire, it was as follows: their place of residence changed during the last months (please specify).

Interview participants

Eight caregivers participated in a one-on-one qualitative interview. To ensure the confidentiality of the participants, pseudonyms assigned by the researchers are used to identify them. Characteristics of these caregivers are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Characteristics of caregivers who participated in a qualitative interview

a None of the caregivers who participated in the qualitative interviews were living with the care recipient

In the following sections, for each theme, quantitative results are presented first, followed by insights from the qualitative interviews (identified with pseudonyms) or qualitative comments from the questionnaires (identified with the questionnaire number [Q1 or Q2] and the respondent number).

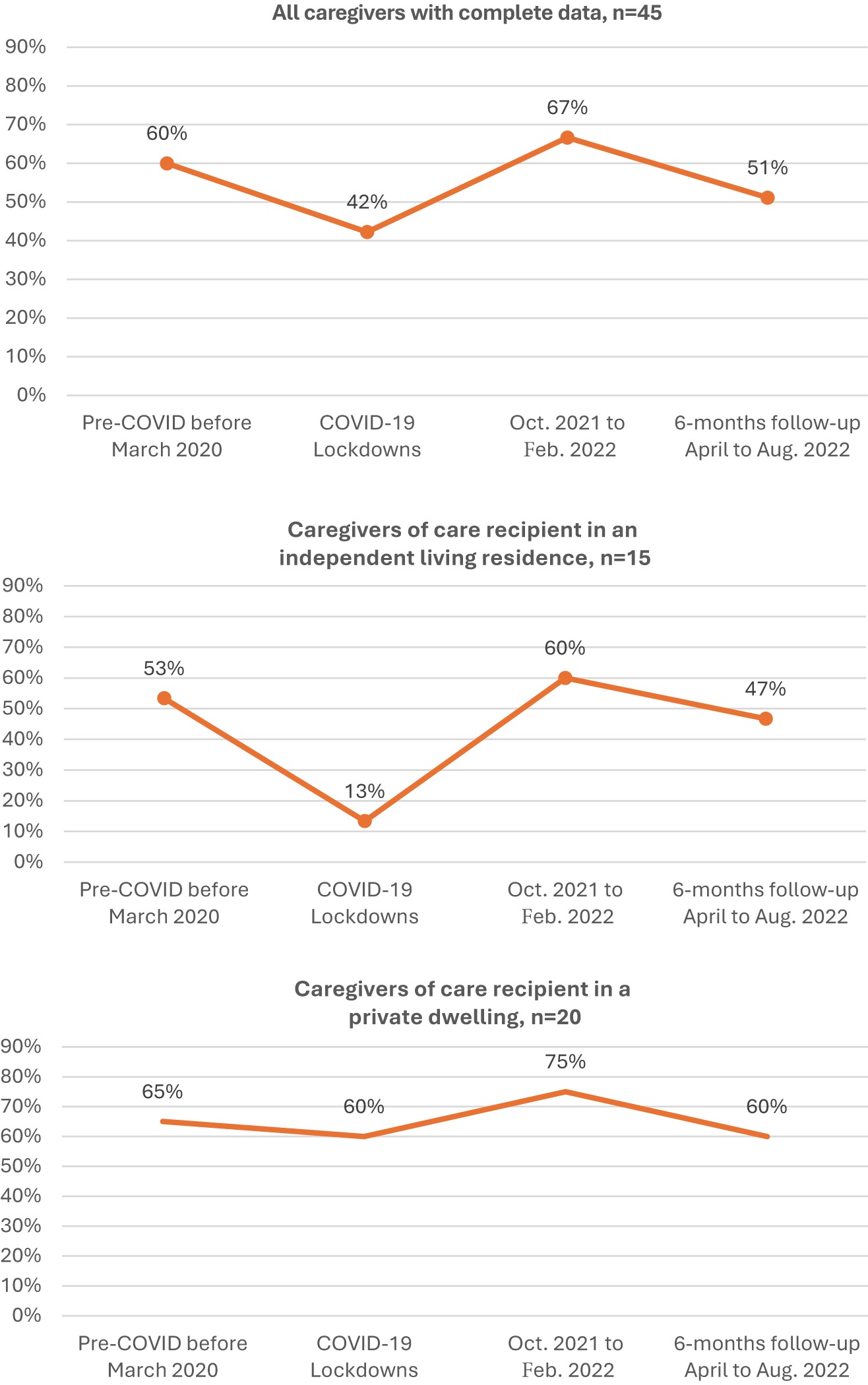

Caregiver visits

Questions about the frequency of visits at four different points in time were asked to caregivers not living with their care recipient. Only caregivers who responded at each time point (n = 45) are included in this analysis. Caregiver visits fluctuated over time between pre-COVID-19 and 6-month follow-up. The percentages of caregivers visiting the care recipient at least two or more times per week are displayed in Figure 1. Caregiver visits decreased during COVID-19 lockdown periods, increased throughout October 2021 to February 2022, and then decreased again at the 6-month follow-up, when presumably more external activities had resumed. Sub-group analyses were done with participants whose living situation did not change during the study period. There was a greater decrease in caregiver visits during COVID-19 lockdown periods for recipients living in an independent living residence (n = 15, 53%–13%), compared to recipients living in private dwellings (n = 20, 65%–60%).

Figure 1. Percentages of caregivers visiting the care recipient at least twice a week.

During interviews, caregivers whose care recipient lived in an independent living residence spoke mostly about visitation limits during the first lockdown periods and then of having to adopt new procedures to be able to enter the residence (choosing one principal caregiver who could enter the residence, mask wearing, COVID-19 testing and questioning, being extra vigilant to avoid contracting and transmitting the virus, etc.).

During the lockdowns, some explained having to leave groceries at the door or the reception desk or trying to see their loved one from the window or further away.

We used to talk to each other from the window, until I was told at some point not to go on the [Residence] grounds. So, there I was, in the parking lot, on the other side of the fence […]. Then again, [they] told me to get off the lot. I said well, where am I supposed to talk to her? […]. The only time I could really go and see her was when she had an appointment to have her PCR cleaned. (Florette, translated from French)

Caregivers spoke of these visitation limits as added stress for them from not being able to have contact with their loved one and not being able to provide the same care as usual. In this regard, Ginny said: ‘It was very difficult in the sense that we couldn’t go into the building to see her, but at the same time, we knew she needed help with certain things’ (translated from French).

However, resuming visits after lockdown periods also led to certain challenges as caregivers found themselves having to negotiate between taking part in social activities and visiting their loved one.

But when we started seeing friends again, well, they were working, so it had to be the weekend. But on weekends, I was going to my grandmother’s. […] And if I see a friend, well, maybe I should wait a week before seeing my grandmother, just in case. But if I wait a week, that’s a week I don’t see her. (Lisette, translated from French)

Most caregivers whose care recipient lived in private dwellings explained that it was important to continue offering care to their loved one, so they continued to visit them while following rigid guidelines to prevent virus transmission and by organizing a visiting schedule among family members to take turns. However, certain caregivers mentioned that different points of view among family members created tensions in the family, since some felt it was necessary to keep visiting the care recipient to provide care and counter isolation, while others felt that the risk of transmitting the virus was too important.

Types of care and support provided by caregivers

Caregivers provided various types of care and support, including personal care (e.g., help with eating, dressing, and bathing), medical care (e.g., taking medication), care management (e.g., scheduling appointments), housework, transportation, meal preparation or delivery, psychological or social support, administrative tasks (e.g., managing finances), and therapeutic activities or exercise.

The percentage of all caregivers providing various types of care and support are shown in Figure 2 presented in a supplementary data file Footnote 5. During COVID-19 lockdown periods, there was an increase in the provision of personal care, medical care, care management, and meal preparation or delivery. Throughout October 2021 to February 2022, a further increase was observed in personal care, care management, housework, transportation, and psychological and social support. At the 6-month follow-up, the percentages were at the highest for all types of care and support, except for a decrease in medical care, housework, and meal preparation or delivery.

Types of care and support provided by caregivers during the pandemic could vary according to the living situation. Among the sub-set of caregivers and recipients not living together and not in an independent living residence (n = 23), the percentages were lower than in the total sample for personal care, care management, and psychological support and higher for housework, administrative tasks, and therapeutic activities or exercise. The trends in time were similar to those seen in the total sample except for an increase in help for housework and a decrease in psychological or social support at the 6-month follow-up.

During interviews, caregivers whose care recipient was living at home talked about their role and tasks to keep their loved one at home, as well as their system for sharing tasks with other family members. Certain caregivers felt an increase in the care they provided to counter the lack of external services now unavailable due to the pandemic.

We had one of our home care workers who had an immunosuppressive problem. So she had to protect herself even more. It was a real panic at first. Nobody knew what was going on. So I was asked to do a lot more. I was the one who took care of my mother during the day, every day for the first few months. (Lilianne, translated from French)

Caregivers whose care recipient lived in an independent living residence mostly provided certain meals or groceries, transportation and accompaniment to medical or personal appointments, care management, regular telephone calls during lockdown periods, and social outings once permitted. One of the participants, Ginny, was a nurse and said that her mother relied on her for everything health related. On her part, Florette explained that she constantly had to keep an eye on her mother, even though she lived in a residence.

At one point, I was sick. When I felt well enough to see my mother, there were dirty clothes piled up. No one in the residence picked them up [for laundry]. I really, had to be always present, well, not to complain, but to say that it’s reality. (translated from French)

Community services for older adults

The percentage of older adults receiving care and support from community services are shown in Figure 3 presented in a supplementary data file. Approximately one quarter of care recipients did not receive any community services during the four time periods. During COVID-19 lockdown periods, participants reported an increase in community services for medical care and meal preparation or delivery, whereas respite care decreased. Throughout October 2021 to February 2022, an increase in community services for personal care, medical care, housework, transportation, and respite care was observed. At the 6-month follow-up, reported community services for medical care, housework, and respite care decreased.

Some care recipients had moved from their home to independent living residences or to assisted living accommodations between the initial and 6-month follow-up questionnaires. Among the sub-set of care recipients living alone (n = 17), there was an increase in help with housework from initial questionnaire (29.4%) to 6-month follow-up (41.2%).

Among the sub-set of care recipients living with family members (n = 50)Footnote 6, there was a decrease in respite care from initial (24%) to lockdown periods (16%). In the October 2021–February 2022 period, respite care had returned to a higher level (36%) but then decreased again at the 6-month follow-up (16.2%, n = 37 care recipients still living with family members). This later decrease may be explained by the fact that those receiving respite were more likely to have changed their living arrangement (e.g., care recipient moved to an assisted living accommodation).

Qualitative data reveal different experiences regarding access to home care or community services during the pandemic. Some caregivers mentioned that community services continued during the pandemic. Christine acknowledged that her parents were very lucky because their family doctor had retired but maintained services to a handful of patients, including her parents, and continued to visit them in their home. Some reported that care attendants took all the necessary sanitary precautions, which was a great relief for caregivers. However, some mentioned the challenge of having rotated personal workers coming into the home, which confused or worried the care recipient.

So then they said somebody had to come and watch her, but every two weeks it would be somebody different. And then my mother said I don’t want strangers in my house. Like she said; if it’s the same person all the time, that’s fine, but every two weeks, they ring the doorbell, and I don’t know who it is. (Bonnie)

For other caregivers, community services had decreased during the pandemic; therefore, caregivers had to compensate for the lack of support, as evidenced by the following questionnaire respondents’ comments.

Before the pandemic, my wife had services 5 days/week, with 3 baths/week. During the pandemic, services were reduced to 2 days/week […]. For me, this meant a lot more work and responsibility. (Q2-R91, translated from French)

Organizations seem overwhelmed, and caregivers spend too much time searching for the help they need for their relative. (Q2-R37, translated from French)

Some caregivers felt a need to change their loved one’s living arrangements to compensate for the lack of support either from home care or in long-term care homes.

The absence of services during the pandemic has dramatically accelerated the need to admit my husband into long-term care. No day-care programs, no respite care, no in-person caregiver support, and dramatically reduced social interaction ultimately made in-home care no longer feasible. (Q2-R113)

I discharged my mother from [long-term care] in March 2021. She had been transferred there from an [independent living residence] two months before. The lack of services and care led me to take her in. (Q2-R163, translated from French)

Support for caregivers

The percentage of caregivers receiving support for themselves are shown in Figure 4 presented in a supplementary data file. Most caregivers (nearly 60%) received no support throughout the entire study period. During COVID-19 lockdown periods, the proportion of caregivers who received support from health care workers or social workers (12%–20%) and support groups (11%–17%) increased. Participation in support groups was highest at the 6-month follow-up. Respite in residential settings decreased during the lockdowns (4%–2%) and increased to 10% after the end of the lockdown periods.

During the interviews, caregivers talked about various sources of support that they sought for themselves during the pandemic, such as a family doctor, a therapist, a social worker, online resources or webinars for caregivers, formal support groups, or informal support by talking with family members or friends. Caregivers who felt they had good support were those with strong family ties, or familiarity with community resources, either because they worked in the field or because someone else directed them to these resources.

For me, what was really helpful about the pandemic was having people to talk it over with. Whether it was my sister, my family, or the organizations I was involved with, it was being able to let go of emotions and stress a little. (Lilianne, translated from French)

The increased availability of virtual resources was also mentioned by caregivers as an aspect facilitating access to support for themselves.

Unfortunately, not all caregivers had easy access to support for themselves or even knew where to find such services. Christine felt that she did not have much support for herself during the pandemic: ‘I felt really, really alone’ (translated from French). Questionnaire respondents also reported a lack of support:

The pandemic opened my eyes to how hard it is to find support for seniors in crisis at home and how hard it is to find support for me as a caregiver. (Q1-R80)

It was a very hard time for us caregivers during the pandemic, no help to support us emotionally, […] nobody answered us anywhere, no access to the doctors of our loved one, no return call from them, and it was the same for the CLSC, no return call from the social worker. (Q1-R63, translated from French)

Impact on physical, mental, and cognitive health

A negative impact of the pandemic on caregivers’ and care recipients’ physical and mental health was perceived by 50%–72% of the participants. The impact on cognitive health was only inquired for care recipients, and the perception of a negative impact was also high (55%–62% of the participants). The impact persisted over time, as the differences were minimal and not statistically significant between the initial and follow-up questionnaires as shown in Table 4 presented in a supplementary data file.

The pandemic’s health impact on caregivers and care recipients was also apparent in the qualitative data.

Christine’s physical fatigue was very evident during the interview: ‘I feel I’ve aged 10 years in two years (she cries). Physically, it really hit me …. my body has changed so much. […] It’s all been very heavy’ (translated from French).

Others mentioned the negative impact that the pandemic had on their own mental health. ‘There was always stress, stress of contracting COVID, not knowing and transmitting it [to my father], stress of changing districts […]. It was a lot’ (Rose, translated from French).

Caregivers also observed changes in care recipients, such as signs of fatigue from the pandemic sanitary measures or a decline in mental health or cognitive functioning resulting from prolonged isolation.

And then at some point, when she was really fed up with being within her own four walls, as she puts it, she said to me: “At my age, I’ve lived long enough. So, I’d rather go out, even if I catch it, it doesn’t matter. I’ve lived long enough”. (Amelie, translated from French)

She’d been trapped in her room for months and months and months. All of a sudden, she couldn’t even get out. That’s how bad it got. She was all mixed up. No matter how much I talked to her, she was angry with everyone. She was mad at the people who were going to bring her food. That’s weird. That’s not really like my mother. (Florette, translated from French)

In terms of her memory and all that, I mean, it’s certainly a progression with Alzheimer’s, but I think that the pandemic has contributed, that it’s worse than it would have been if there hadn’t been, if she hadn’t been so isolated. (Ginny, translated from French)

Caregiver burden, loneliness, and social support

The mean burden score of our sample was extremely high (21.0 at the initial questionnaire and 20.6 at the 6-month follow-up out of a total of 48). The mean scores for loneliness (3.2 and 3.4) observed in this study are similar to those reported by Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Parmar, Dobbs and Tian2021) in a study on caregivers carried out in July 2020 (3.3–4.5 according to the living situation) but higher than those reported retrospectively as being felt prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in the same study. We did not find comparative data for caregiver scores on the 6-item MOS scale.

Changes in total scores for burden, loneliness, and social support are presented in Table 5 found in a supplementary data file. Among most caregivers, the total mean burden scores remained stable between initial questionnaire and 6-month follow-up, although 20.3% of caregivers had an increase in burden and 24.6% reported a decrease. Hence, the difference in mean total scores was not statistically significant. Similar trends are observed for loneliness and social support.

Correlations and multiple regression analysis of sociodemographic variables with burden, loneliness, and social support are presented in a supplementary data file. The only significant result resides in variation in burden scores. Age group (B = 5.91, p = .01) and household gross income (B = 7.17, p = .01) were statistically significantly associated with burden. Caregivers less than 60 years old had on average higher scores of burden than caregivers 60 years and older. In addition, caregivers with household gross income less than 100,000 Canadian dollars (CAD) had on average higher scores of burden than caregivers with household gross income greater than 100,000 CAD.

How the pandemic impacted caregiver burden was strongly expressed in the interviews. For example, Bonnie’s mother was hospitalized a few times during the pandemic and Bonnie had to provide care even at the hospital due to staff shortage. Having children to care for at home at the same time due to school closures and online schooling also contributed to the burden.

But the bulk [of the assistance] kind of fell to me, and because they were so short-staffed in that, oh, and they said once you came in, like if you left, you couldn’t come back. So, like I couldn’t just go for an hour, do something, come back. So, I was staying maybe about five hours trying to cover one or two meals to make sure that she was getting fed and that she had stimulation too because there weren’t enough people to do that. (Bonnie)

It was just hard because I also had two school-aged children at home too and kind of watching out for their mental health too. (Bonnie)

Language of and access to services

Differences between OLMC and non-OLMC caregiver–recipient dyads

Sub-group analyses by OLMC were performed to examine potential differences in types of care and support provided by caregivers, care recipient community services, and supports for caregivers. Results are presented in Figures 5–7 of the supplementary data file. A few differences were found between caregiver–recipient dyads that belong to an OLMC compared to those that belong to the linguistic majority group of their province.

A higher percentage of caregivers from the linguistic majority groups were providing medical care, and the difference was statistically significant during the lockdown periods and after. These caregivers were also more likely to provide help with housework and with meal preparation or delivery at the 6-month follow-up. The percentage of OLMC caregivers providing social and psychological support was higher before the onset of the pandemic (21.1% versus 4.4%, p = 0.03) and tended to be stable throughout the study. The percentage of non-OLMC caregivers providing this kind of support increased gradually but more importantly at the time of the 6-month follow-up questionnaire, reaching a level similar to that of the OLMC group.

There were no statistically significant differences in care recipient community services by OLMC. The percentage of non-OLMC dyads receiving respite from external services tended to be higher, mainly at the 6-month follow-up questionnaire, but this difference did not reach a statistically significant level.

The differences could reflect, at least in part, a difference in living arrangements. As shown in Table 9 of the supplementary data file, care recipients from the OLMC group were more likely to live in an independent living residence where meals are provided and housework tasks are reduced, but psychological support may be needed, while those from the majority group were more likely to live with their caregiver, a situation in which respite is of greater relevance.

The percentage of OLMC caregivers not receiving any support for themselves at the 6-month follow-up was higher (71.1% versus 48.9%), a statistically significant difference of 22.2%, p = .04. We could not find an explanation for this situation in our data.

Impact of pandemic on accessing services in the official minority language

Many members of OLMC (40.5%) did not receive the majority of their support services in the official language of their choice (33.3% of the 6 anglophones in Quebec and 41.9% of the Francophones from the other provinces). Statistical analysis revealed no objective change in the language of the services received at different time points during the study period, either for those preferring services in English or in French. However, it is of interest to note that 15 of the 32 (46.9%) Francophones in a minority context reported a perceived increased difficulty accessing services in French as a consequence of the pandemic, while one of the 6 (16.6%) Anglophones in a minority context reported a perceived increased difficulty accessing services in English. Comments from questionnaire participants suggest that the lack of services generally was problematic, not necessarily as they relate to language: ‘Not many services to get, independently of language’ (Q1-R164) and ‘The province is bilingual, so the problem is not language, it’s the services.’ (Q1-R34, translated from French).

During the interviews, caregivers in New Brunswick and Ontario who already had access to French-speaking staff mentioned that they continued to receive these services in French. Amelie felt grateful for the widespread use of French in her mother’s independent living residence: The residence manager was bilingual as were many staff members, and activities were often offered in both official languages. Only one caregiver reported a loss of French-language services, mentioning that there was only one French-speaking attendant who cared for her parent, and this person stopped working during the pandemic because she had a young child at home. Other families who did not have access to services in French before March 2020 did not receive more of these during the pandemic.

However, caregivers spoke about the importance of receiving services in their official language of choice. Bonnie explained that her mother was much more at ease when she was brought to a hospital in Quebec that offered services in English, her official language of choice: ‘She was attended to in English and she said oh, my gosh, it’s so much different when I can speak English and they understand’. Bonnie felt that her mother received more attention and better care in this situation.

Rose explained the strategies she used to get English-speaking attendants to communicate with her French-speaking father: ‘Some were unilingual English speakers. That’s why I developed little memory cards, cheat sheets. On one side, it was “As-tu faim?” and on the other, the attendant could read “Are you hungry?” So she could try to say it, or my father in those days could read it. We had to be creative together to develop strategies like that’ (Rose, translated from French).

Discussion

This study sought to better understand the experience of family/friend caregivers providing care to older adults living at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to respondents, the pandemic had a negative impact on the physical and mental health of caregivers, as well as on the physical, mental, and cognitive health of care recipients. These results are consistent with those of other studies on the impact of the pandemic on caregivers and older adults (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Parmar, Dobbs and Tian2021; Borg et al., Reference Borg, Rouch, Pongan, Getenet, Bachelet, Herrmann, Bohec, Laurent, Rey and et Dorey2021; Cagnin et al., Reference Cagnin, Di Lorenzo, Marra, Bonanni, Cupidi, Laganà, Rubino, Vacca, Provero, Isella, Vanacore, Agosta, Appollonio, Caffarra, Pettenuzzo, Sambati, Quaranta, Guglielmi, Logroscino and Bruni2020; Lightfoot, Moone, et al., Reference Lightfoot, Moone, Suleiman, Otis, Yun, Kutzler and Turck2021; Roach et al., Reference Roach, Zwiers, Cox, Fischer, Charlton, Josephson, Patten, Seitz, Ismail and Smith2021; Tsapanou, Papatriantafyllou, et al., Reference Tsapanou, Papatriantafyllou, Yiannopoulou, Sali, Kalligerou, Ntanasi, Zoi, Margioti, Kamtsadeli, Hatzopoulou, Koustimpi, Zagka, Papageorgiou and Sakka2021). In addition, our study showed that these impacts were maintained 2 years after the pandemic onset. Our qualitative data have shown the extent to which this impact may have had serious consequences for some caregivers, who had little or no time for respite and had to increase their efforts and energy to look after their loved one. When caring for someone in an independent living residence, they felt anxious during visitor restrictions and afterward. Similar findings are reported for persons caring for individuals in assisted living residences who felt they always needed to have a watchful eye on the care provided (Altieri & et Santangelo, Reference Altieri and Santangelo2021; Dupuis-Blanchard et al., Reference Dupuis-Blanchard, Maillet, Thériault, LeBlanc and Bigonnesse2021).

Quantitative findings suggest that most community services seem to have been maintained during the pandemic, except for respite care. An overall decrease is observed only in housework support at the 6-month follow-up; this could be explained by the fact that some care recipients moved to an independent or assisted living residence and no longer required housework support. In fact, for care recipients who were living alone, an increased housework support is observed from both community services and their caregivers.

Despite community services being maintained, caregivers reported having increased their support to their care recipient during the lockdown periods and after. This could in part be explained by the normal aging process that would have occurred, although many respondents felt that the impact of the pandemic had exacerbated this decline. In addition, the pandemic may have brought an increased need for emotional support. Shortage and turnover of staff seen during and after the end of the sanitary measures (Blackwell, Reference Blackwell2023) was also mentioned as one of the reasons for this increased need for support from caregivers. These results are congruent with those of a study conducted in nursing homes in which caregivers observed changes in the care recipients’ physical and cognitive health and reported that because of the lack of human resources, they were expected to do more personal care once able to visit (Dupuis-Blanchard et al., Reference Dupuis-Blanchard, Maillet, Thériault, LeBlanc and Bigonnesse2021).

Although caregiver burden was felt as having increased with the pandemic in our qualitative data, the quantitative scores obtained in our study (from 1 to 2 years after the pandemic onset) were similar to those being reported in studies conducted prior to the pandemic (Bédard et al., Reference Bédard, Molloy, Squire, Dubois, Lever and O’Donnell2001; Hébert et al., Reference Hébert, Bravo and Préville2000).

Regarding the language of services, we had expected a decrease in the proportion of services offered in the minority language because of staffing issues observed during this period. Language preference may have been less of a priority when organizing services, but this did not emerge in our quantitative data on the language of services received, although there was a perception of increased difficulty accessing these services for the Francophones in a minority context. The qualitative data also revealed the fragility of certain French-language services, for example, when a service loses its only French-speaking provider. When it is not possible to get services in French from the service provider, the caregiver often must act as an interpreter for the care recipients or develop tools to facilitate communication. In addition, caregivers highlighted quite clearly the positive impact perceived by the older adults when they received services in the official language of their choice. They felt that the older adult received better quality care in their official language of choice since they were communicating more clearly and had a better understanding of the current situation. Similarly, in the qualitative study by Dupuis-Blanchard et al. (Reference Dupuis-Blanchard, Maillet, Thériault, LeBlanc and Bigonnesse2021), caregivers observed language issues between staff and their relative in nursing homes. They mentioned that in a situation of high staff turnover, organizations were often not recruiting bilingual individuals.

Recommendations

At the beginning of the pandemic, the government was mainly focused on preventing transmission of the virus and less attention was given to the emotional needs of the population, including older adults and their caregivers. Our results confirm the impact of this orientation. Our main recommendation would be to recognize the central role of caregivers in the care of older adults living with autonomy loss. This would lead to better integration of the needs of caregivers in any public health policy. Caregivers are able to share their perspectives and needs, and it is essential to listen to them. In fact, during the interviews, caregivers provided some recommendations for possible future health crises such as the pandemic, including ensuring caregivers easy access to independent living residences, better consideration of the impact of loneliness on older adults, providing caregiver training on new health instructions, informing caregivers of available support groups and resources, providing technological support for older adults to enable distance communication with their relatives, and ensuring that retirement homes or home care personnel provide regular follow-ups with families. In addition to the recommendations provided by the caregivers, we suggest that in OLMCs, allowing the presence of family/friend caregivers in assisted living residences and care institutions is even more important as they facilitate communication between their relative and the institution’s personnel. This fact should be considered by decision makers in future crises.

Study limitations

The respondents in our study represent a demographic profile that is younger, better educated, and more financially well-off than that typically presented in research on family caregivers. This may be the result of recruitment by convenience sampling through social media networks and community organizations’ newsletters. As such, participant responses may not be representative of all caregivers for an older adult living at home or in an independent living residence.

We also did not interview as many caregivers as we would have liked, as most of the participants for the qualitative part were from Ontario, and only one was from the anglophone minority in Quebec. Thus, the qualitative results may not be representative of the caregivers’ lived experience in the four provinces.

Another limitation is that the questionnaires were self-reported. Documentation of care provided and received before and during the lockdown periods was provided retrospectively, and responses may be influenced by recall bias. We had no data on burden before the pandemic (we decided not to measure burden retrospectively due to risk of bias) so we cannot attest whether caregiver burden increased due to the pandemic or not.

Conclusion

Caregivers felt that the pandemic had a prolonged impact on their physical and mental health, as well as on the physical, mental, and cognitive health of their care recipients. Being unable to visit their loved ones was distressing for caregivers. Lack of respite services may also have contributed to caregiver burden, although many caregivers did not receive any respite or formal support even before the pandemic.

While our quantitative data did not reveal changes in the language of the services received before, during, and after the lockdown periods, findings from the qualitative data showed the precarity of French-language services when the only French-speaking care provider is unavailable.

Caregivers’ responsibilities are important independently of linguistic context or living situation of care recipients. The pandemic added to this already important mental and physical burden. If caregivers are to be recognized as partners of the health organizations, better consideration of their needs is essential. Continued research on this topic is important as new epidemics and other large-scale public health events are likely to recur.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980825100494.

Acknowledgements

This study received funding from the Consortium national de formation en santé, University of Ottawa component and the national secretariat, to whom we are grateful. We also acknowledge the collaboration of the partner organizations throughout the research: Société Santé en français, the Perley and Rideau Veteran’s Health Centre, the Dementia Society of Ottawa and Renfrew County, the Ontario Caregiver Organization, the Fédération des aînés et des retraités francophones de l’Ontario, the Association francophone des aînés du Nouveau-Brunswick, the Fédération des aînés de la francophonie manitobaine, and L’appui pour les proches aidants.

We are also grateful for the help of all other organizations that assisted with recruitment: Parkinson Canada, Centre d’action bénévole Grand Châteauguay, Club 55+ Châteauguay, Centre d’action bénévole d’Argenteuil, Réseau des services de santé en français de l’Est de l’Ontario, Réseau du mieux-être francophone du Nord de l’Ontario, Conseil sur le vieillissement, Réseau de soutien communautaire de Champlain, Ontario Community Support Association, Seniors Services Development of the region of Peel, Radio-Canada, Temiskaming Shores Manor, Holy Cross Parish, Port Elgin/Paquetville-Inkerman/Lamèque Nursing Home Without Walls, Volunteer Centre of the Acadian Peninsula, Collaborative on Healthy Aging and Care, Réseaux-santé du Nouveau-Brunswick, Mouvement acadien des communautés en santé du Nouveau-Brunswick, ARCf de Saint-Jean, Alzheimer Society of New Brunswick, L’Initial residence, Chartwell Monastère d’Aylmer, St-Paul Parish, Entre-nous Community Centre, Deschênes Community Centre, 4 Korners, Townshippers Association, West Quebecers Association, Connexions Resource Centre, Senior Services on the Lower North Shore, Saint-Antoine 50+, Community Health & Social Services Network, Assistance and Referral Centre of Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu and Longueuil, Vision Gaspé-Percé Now, Contactivity Centre, Shared Health Manitoba, A & O Support Services for Older Adults, St-Boniface Diocese, Winnipeg Diocese, Société de la francophonie manitobaine, and Creative retirement.