1. Introduction

The significance of flows along micro- or nanostructured surfaces extends across various technical applications, such as in micro-fluid mechanics and process engineering. Particular attention is devoted to so-called superhydrophobic (SHS) and liquid-infused surfaces (LIS). Their desirable effect is achieved by trapping a lubrication fluid within these structures on an otherwise no-slip wall. Once enclosed, the fluid forms a boundary to the primary fluid and thus creates a heterogeneous surface with a solid–fluid and fluid–fluid interface pattern. This reduces the relative surface fraction of the solid wall, which therefore means that the bulk flow can partially slide over fluid cushions scattered across the wall. Such a unique configuration imparts lower surface wettability, resulting in water-repellent behaviour, utilised for self-cleaning (Fürstner et al. Reference Fürstner, Barthlott, Neinhuis and Walzel2005), anti-fouling (Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Wong, Belisle, Boggs and Aizenberg2012) and anti-icing (Latthe et al. Reference Latthe, Sutar, Bhosale, Nagappan, Ha, Sadasivuni, Liu and Xing2019) effects as well as for significant drag reduction (Vinogradova Reference Vinogradova1999; Ou, Perot & Rothstein Reference Ou, Perot and Rothstein2004; Belyaev & Vinogradova Reference Belyaev and Vinogradova2010; Rothstein Reference Rothstein2010; Karatay et al. Reference Karatay, Haase, Visser, Sun, Lohse, Tsai and Lammertink2013). Alongside the aforementioned apparent slip effect, there exists another phenomenon referred to as molecular (or intrinsic) slip (Lauga, Brenner & Stone Reference Lauga, Brenner and Stone2005). The latter describes liquid molecules actually sliding along a solid wall. Due to its minor significance in engineering applications (Hardt & McHale Reference Hardt and McHale2022), it is not further considered.

Maximising apparent slip, however, depends on the choice of lubrication, with air being a suitable candidate (SHS). As the enclosed fluid is dragged along with the bulk flow, the interface causes almost no resistance due to the low viscosity of air, in fact often idealised to be shear free (Davis & Lauga Reference Davis and Lauga2009; Crowdy Reference Crowdy2010; Schnitzer & Yariv Reference Schnitzer and Yariv2019). However, this mobility may be hindered by deposited surfactants and impurities, causing interface rigidity ( McHale, Flynn & Newton Reference McHale, Flynn and Newton2011; Schäffel et al. Reference Schäffel, Koynov, Vollmer, Butt and Schönecker2016). Additionally, air dissipation can occur, leading the interface to migrate into the microstructures and consequently expelling the remaining lubricant (Nizkaya, Asmolov & Vinogradova Reference Nizkaya, Asmolov and Vinogradova2014). Once these cavities have been conquered, the desired slip effect is significantly reduced. For this reason, higher-viscosity liquids such as oils are used as lubricants to increase interface stability (LIS), as they are robust against pressure-induced failure (Wexler, Jacobi & Stone Reference Wexler, Jacobi and Stone2015). Although this impedes slippage over the cushions due to increasing shear resistance, the overall wetting condition is more durable (Kim & Rothstein Reference Kim and Rothstein2016; Hardt & McHale Reference Hardt and McHale2022). The stability of such fluid–fluid interfaces is therefore a critical parameter, particularly in configurations with a high interfacial surface fraction. For gas–liquid systems, large interface areas may promote interfacial collapse, if the imposed pressure gradient or shear stresses exceed a certain threshold. Among the various methods to enhance interface stability are coatings with materials having a high contact angle, nano- and microstructured coatings, preferably with overhang structures. In contrast, for liquid–liquid systems, higher interfacial tension and viscosity ratios often allow for more stable menisci, supporting long-term operation. The present analysis assumes this quasi-static interface shape, which is expected to remain valid under moderate pressure gradients and sufficiently high surface tension.

It is evident that the assumption of shear-free interfaces is not valid in this case, necessitating the consideration of the associated interfacial shear losses, as has been addressed by numerous studies (Crowdy Reference Crowdy2017). Depending on the fluid employed, however, unwanted contamination of the bulk flow due to shear-driven drainage can occur, which potentially requires an additional cleaning procedure in the process (Wexler et al. Reference Wexler, Jacobi and Stone2015). The desired sliding effect is of course largely dependent on the fact that fluid interfaces replace no-slip wall sections. However, these walls do not disappear, but continue to influence the mobility of the enclosed fluid, with that influencing the slippage experienced by the bulk flow. Therefore, it would be beneficial to decouple the influence of the wall within the microstructure as much as possible. As mentioned above, this can be realised by using low-viscosity lubricants. However, if the use of air (or other gases) is not possible, the geometry of the cavities must be designed in such a way that the walls move as far into the distance as possible, with that maximising the amount of buffer zone created by the lubricant.

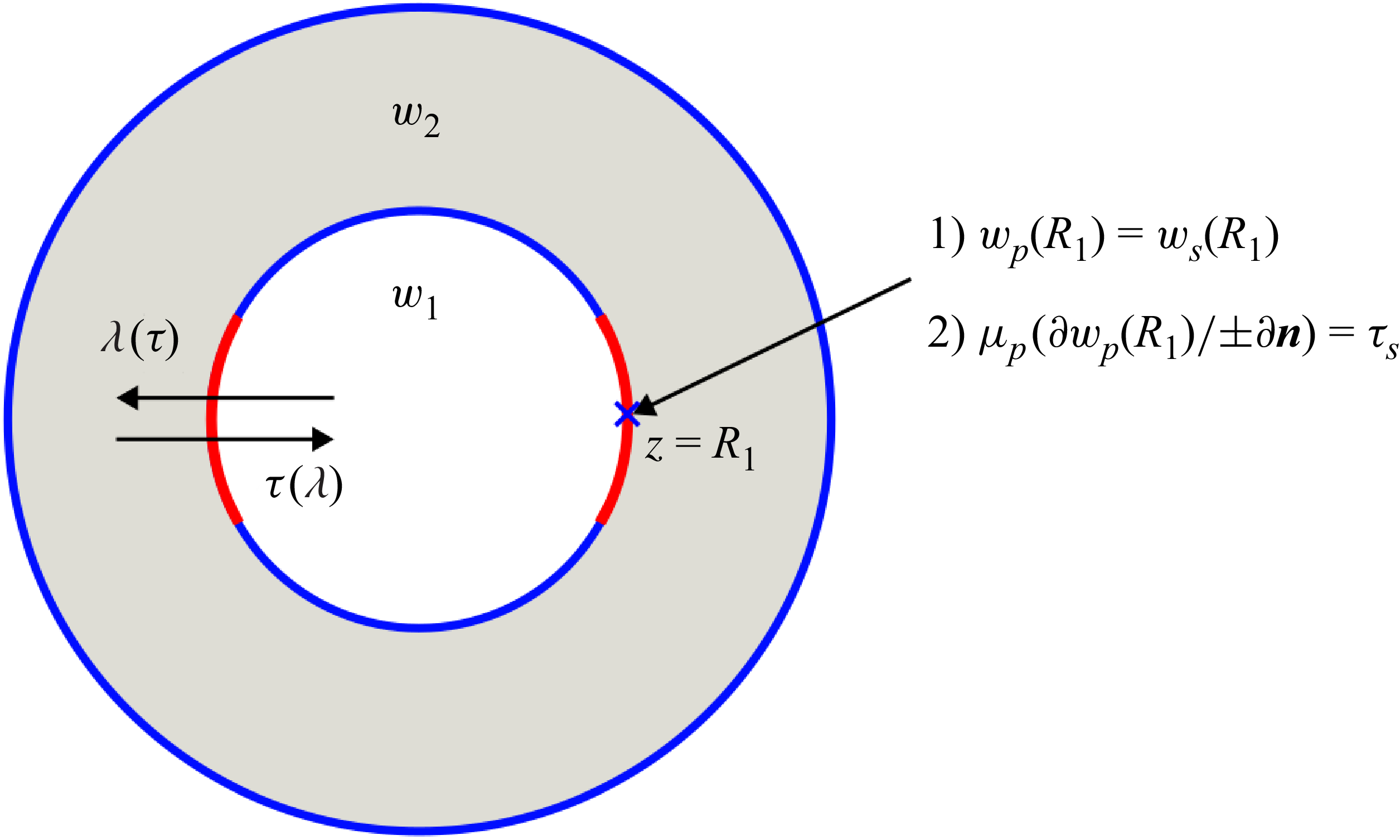

Consequently, it would be ideal to remove all immediate walls within the microstructures. The employed texture therefore has no bottom or sidewalls (apart from the necessary structure height), or at least they are sufficiently far away so that their influence is negligible. This premise motivates the pipes-in-pipes configurations considered in this work, as depicted in figure 1. In this arrangement, the boundaries of pressure-driven (annular) pipes (blue region in figure 1) are equipped with longitudinal slits acting as an interface to a lubricating fluid (illustrated in yellow, see figure 1). The latter is not subject to an external pressure gradient itself, but is merely dragged along the interface, not featuring any immediate walls, instead moving within its own axially infinite tube. This design eliminates recirculation and minimises the walls’ impact on the bulk flow. Assumptions include the same pressure along the longitudinal slits and that the surface tension is sufficiently high so that any protrusion of the interface beyond the current circular arc shape is excluded.

Figure 1. Illustration of a concentric pipe set-up, where an inner pipe (fluid zone 1) is situated inside an outer tube (fluid zone 2), with both being connected to each other via an arbitrary number of axial slits, here shown for 2 slits, depicted as red boundary parts on otherwise no-slip walls. Both illustrated scenarios are fully described in § 3. (a) Depicts a pipe-within-pipe set-up in which the inner region (blue) is driven by a pressure gradient

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

and, as a result, the outer flow (yellow) is dragged along by the shear stress imposed on the interfaces (red boundary parts). Such a scenario is labeled as ‘case 1’. The right-hand side shows the

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

and, as a result, the outer flow (yellow) is dragged along by the shear stress imposed on the interfaces (red boundary parts). Such a scenario is labeled as ‘case 1’. The right-hand side shows the

![]() $(x,y)$

cross-section of the set-up. (b) The opposite case is shown here, i.e. that the annular flow (

$(x,y)$

cross-section of the set-up. (b) The opposite case is shown here, i.e. that the annular flow (

![]() $w_{2,p}$

) is pressure driven, with the lubricant (

$w_{2,p}$

) is pressure driven, with the lubricant (

![]() $w_{1,s}$

) enclosed within the inner pipe, referred to as ‘case 2’.

$w_{1,s}$

) enclosed within the inner pipe, referred to as ‘case 2’.

In our work, we distinguish two scenarios: in case 1, the inner pipe is pressure driven and the outer tube contains the lubricant fluid which is passively dragged along by the primary fluid, as depicted in figure 1(a). In case 2, in addition, the exact opposite is then considered. The outer flow is externally driven by a pressure gradient and the lubricant is located within the inner pipe, as illustrated in figure 1(b). Due to the complexity of both cases described, it is not possible to derive a single analytical, explicit and fully coupled velocity field equation. Rather, to model both scenarios described, four fundamental solutions, i.e. equations for their respective velocity fields, are required. They are then connected, thereby ensuring continuity of velocity and shear forces across each interface.

First, solutions are needed for the pressure-driven pipe (§ 2.1.1) and annular flow (§ 2.2.1), each featuring slits along the walls to represent interfaces interacting with the respective lubricant. This viscous interaction is modelled by introducing a local slip length

![]() $\lambda$

serving as an input parameter dependent on the dynamics of both the pressure-driven flow itself and the lubricant dynamics. The so-called Navier-slip equation

$\lambda$

serving as an input parameter dependent on the dynamics of both the pressure-driven flow itself and the lubricant dynamics. The so-called Navier-slip equation

connects the non-zero wall velocity

![]() $w_{w\textit{all}}$

with its normal derivative

$w_{w\textit{all}}$

with its normal derivative

![]() $\partial / \partial \boldsymbol{n}$

pointing fluid inwards. In the subsequent analysis, it is critically assumed that the latter, i.e. the shear stress, is constant along all interfaces. While this is clearly an approximation, it has been shown by various studies to be a physically reasonable one, showing excellent agreement with numerical simulations (Higdon Reference Higdon1985; Schönecker & Hardt Reference Schönecker and Hardt2013; Schönecker et al. Reference Schönecker, Baier and Hardt2014; Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). It should be noted that modelling non-idealised viscous interface interactions may also be achieved by implementing the corresponding shear stress directly instead of

$\partial / \partial \boldsymbol{n}$

pointing fluid inwards. In the subsequent analysis, it is critically assumed that the latter, i.e. the shear stress, is constant along all interfaces. While this is clearly an approximation, it has been shown by various studies to be a physically reasonable one, showing excellent agreement with numerical simulations (Higdon Reference Higdon1985; Schönecker & Hardt Reference Schönecker and Hardt2013; Schönecker et al. Reference Schönecker, Baier and Hardt2014; Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). It should be noted that modelling non-idealised viscous interface interactions may also be achieved by implementing the corresponding shear stress directly instead of

![]() $\lambda$

. Both approaches are actually equivalent. After all, they are linearly connected, as demonstrated by (1.1). However, the slip length is a common term in the literature and therefore we would like to follow this approach. The necessary pressure-driven equations have already been derived in an earlier work by the authors (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024), where

$\lambda$

. Both approaches are actually equivalent. After all, they are linearly connected, as demonstrated by (1.1). However, the slip length is a common term in the literature and therefore we would like to follow this approach. The necessary pressure-driven equations have already been derived in an earlier work by the authors (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024), where

![]() $\lambda$

was implemented by employing a straightforward linear superposition approach. They are introduced in § 2 in a different notation to the original work. The derivations presented in this paper are quite similar to those in Zimmermann & Schönecker (Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024) in that they utilise solutions that have already been published in the literature and combine them in such a way as to implement potentially finite non-zero shear stress along certain boundary parts of circular pipes. The fundamental distinction pertains to the ambit of application. The present paper diverges from the original, exclusive pressure-driven flow regimes, additionally incorporating externally driven passive pipes as well. These pipes correspond to superhydrophobic or liquid-infused pipes, where the lubricant is not directly pressure driven, but dragged along by the main fluid.

$\lambda$

was implemented by employing a straightforward linear superposition approach. They are introduced in § 2 in a different notation to the original work. The derivations presented in this paper are quite similar to those in Zimmermann & Schönecker (Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024) in that they utilise solutions that have already been published in the literature and combine them in such a way as to implement potentially finite non-zero shear stress along certain boundary parts of circular pipes. The fundamental distinction pertains to the ambit of application. The present paper diverges from the original, exclusive pressure-driven flow regimes, additionally incorporating externally driven passive pipes as well. These pipes correspond to superhydrophobic or liquid-infused pipes, where the lubricant is not directly pressure driven, but dragged along by the main fluid.

Additionally, equations for the lubricant in a pipe (§ 2.1.2) and annulus (§ 2.2.2) are derived, whereby, as mentioned earlier, they are not driven by a pressure gradient but rather through the shear stress imposed by the corresponding pressure-driven flow at the interface. This constant-shear stress is the relevant unknown in these equations. Finally, these fundamental solutions are coupled along the interface according to the two scenarios described (§ 3). This coupling results in the complete determination of the previously unknown variables (local slip length and shear stress at the interface) in relation to their opposite flow region. The outcome is a coupled system where no unknowns remain, and only fluid and geometric parameters need to be specified to obtain the coupled velocity field.

With these newly derived solutions, it is now possible to fully compute configurations of SHS and LIS in circular geometries, considering the practically relevant case of interacting pressure driven and passively dragged along lubricant for drag reduction. This allows for the consideration of various Newtonian fluids as lubricants. The equations obtained are of significant importance for the design, layout and optimisation for enhancing the overall performance of SHS and LIS, which hold crucial applications in engineering. While drag reduction represents a primary motivation for the development of SHS and LIS, such configurations are also of considerable interest for applications where interfacial processes play a central role, for example in microreactors or membrane contactors where chemical reactions or mass transfer occur directly at the fluid–fluid interface. In these cases, the interface serves not primarily as a slip promoter but as an active reactive or transport boundary, and the present model provides a framework to predict and optimise the coupled flow fields in such devices.

It is imperative to note that all four essential solutions necessary for describing such a coupled pipe-in-pipe velocity field can be derived by a linear combination of four equations which are already well established within the existing literature, namely

-

(i)

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PP}}$

– Poiseuille flow in a circular pipe with pressure gradient

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PP}}$

– Poiseuille flow in a circular pipe with pressure gradient

$-s$

;

$-s$

; -

(ii)

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

– Poiseuille flow in an annular pipe with pressure gradient

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

– Poiseuille flow in an annular pipe with pressure gradient

$-s$

;

$-s$

; -

(iii)

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Philip}}$

– Philip’s solution for a pressure-driven pipe flow with shear-free slots and pressure gradient

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Philip}}$

– Philip’s solution for a pressure-driven pipe flow with shear-free slots and pressure gradient

$-s$

;

$-s$

; -

(iv)

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

– Crowdy’s solution for pressure-driven flow through an annular pipe with shear-free slots on the inner wall and pressure gradient

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

– Crowdy’s solution for pressure-driven flow through an annular pipe with shear-free slots on the inner wall and pressure gradient

$-s$

.

$-s$

.

The first two solutions,

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{PP}}$

and

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PP}}$

and

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

, can be found in almost every textbook on the matter. The third solution has become canonical for describing axial flow along SHS pipes (Philip Reference Philip1972a

) and the last,

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

, can be found in almost every textbook on the matter. The third solution has become canonical for describing axial flow along SHS pipes (Philip Reference Philip1972a

) and the last,

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

, has been derived recently by Crowdy (Reference Crowdy2021).

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

, has been derived recently by Crowdy (Reference Crowdy2021).

The velocity field solutions presented here are obtained by combining existing results from the literature in a manner that emphasises clarity and accessibility. However, an alternative and more rigorous derivation based on methods of complex analysis is provided in Appendices A and B. This complementary approach not only confirms the validity of the main results but also offers additional theoretical insights that may be of independent interest to the reader.

2. Mathematical framework – fundamental solutions

The following section will derive, present and discuss the fundamental solutions mentioned in the introduction. First, solutions for pressure-driven flows are presented, which are solutions previously derived by the authors (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024) that are only adapted in their notation (inner pipe flow in § 2.1.1 and outer annular flow in § 2.2.1). Subsequently, solutions for fluid flows being driven by

![]() $N$

rotationally symmetric shear-imposing slits on the walls are derived (inner pipe flow in § 2.1.2, outer annular flow in § 2.2.2). The derived equations then possess an input parameter for the constant interfacial shear stress that is to be determined.

$N$

rotationally symmetric shear-imposing slits on the walls are derived (inner pipe flow in § 2.1.2, outer annular flow in § 2.2.2). The derived equations then possess an input parameter for the constant interfacial shear stress that is to be determined.

2.1. Inner pipe flow

2.1.1. Pressure-driven finite-shear inner pipe solution

For the first fundamental solution we are considering a pressure-driven flow through a pipe with outer radius

![]() $R_1$

and

$R_1$

and

![]() $N$

rotationally symmetric slits. These slits can be interpreted as an interface between the pressure-driven pipe flow and a lubricating fluid, located in an outer pipe region (see § 2.2.2). It is assumed that the surface tension at the interface is sufficiently high to prevent a slit protrusion deviating from its current circular arc shape. The crucial point is that the intricate viscous interaction of both fluid zones involved at the interface is modelled with a local slip length

$N$

rotationally symmetric slits. These slits can be interpreted as an interface between the pressure-driven pipe flow and a lubricating fluid, located in an outer pipe region (see § 2.2.2). It is assumed that the surface tension at the interface is sufficiently high to prevent a slit protrusion deviating from its current circular arc shape. The crucial point is that the intricate viscous interaction of both fluid zones involved at the interface is modelled with a local slip length

![]() $\lambda _1$

, which is defined at the centre of the slit.

$\lambda _1$

, which is defined at the centre of the slit.

Philip (Reference Philip1972a

) provides the foundation for the presented pressure-driven flow. Using conformal mapping, he derives an analytical expression for the velocity field assuming that the slits along the boundary are shear free. This assumption means that the bulk flow travels over these segments without any resistance, which corresponds to an infinite local slip length or vanishing shear stress at the slits. This is a suitable approximation for the interaction of water and air along such an interface, provided a sufficiently large air layer depth (Busse et al. Reference Busse, Sandham, McHale and Newton2013) and width (Schönecker et al. Reference Schönecker, Baier and Hardt2014), as also discussed in § 4. At the same time, however, this shear-free assumption does not take into account some important factors, such as the exact viscosity of the enclosed fluid and the geometry of the secondary fluid zone. To close this gap, the authors extended Philip’s model using a superposition approach in an earlier work (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). This corresponds to extending Philip’s no-shear solution with a constant shear at the slits. The pre-existing flow field over shear-free slits were combined with known solutions of the Poisson equation, which solely possess no-slip walls on the outer boundary, such that the solution is simply a linear combination of

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{Philip}}$

and

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Philip}}$

and

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{PP}}$

. It was crucially assumed that the resulting velocity field itself exhibits a constant finite-shear stress along the interface segments. Numerous studies show that this assumption is not merely mathematically convenient, but is in fact a reasonable physical approximation, as discussed in the introduction. Considering suitable matching conditions, the viscous interaction along the interface is modelled using a finite local slip length

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PP}}$

. It was crucially assumed that the resulting velocity field itself exhibits a constant finite-shear stress along the interface segments. Numerous studies show that this assumption is not merely mathematically convenient, but is in fact a reasonable physical approximation, as discussed in the introduction. Considering suitable matching conditions, the viscous interaction along the interface is modelled using a finite local slip length

![]() $\lambda _1$

defined at the slit centre, contrary to the implicitly infinite one in Philip’s approach (Philip Reference Philip1972a

). For further information and a detailed derivation of the analytical model just described, see Zimmermann & Schönecker (Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). Finally, the equation for the normalised velocity field of a pressure-driven flow through a pipe with

$\lambda _1$

defined at the slit centre, contrary to the implicitly infinite one in Philip’s approach (Philip Reference Philip1972a

). For further information and a detailed derivation of the analytical model just described, see Zimmermann & Schönecker (Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). Finally, the equation for the normalised velocity field of a pressure-driven flow through a pipe with

![]() $N$

rotationally symmetric finite-shear slits is

$N$

rotationally symmetric finite-shear slits is

with the integral

\begin{align} I_1(\zeta ) = \int _{-q}^{\zeta } \left (1 - \left ( \frac { (\zeta '-q) (\zeta '-q)}{(\zeta '-a) (\zeta '-\bar {a})} \right )^{\frac {1}{2}} \right ) \frac {\mathrm{d}\zeta '}{\zeta '} , \end{align}

\begin{align} I_1(\zeta ) = \int _{-q}^{\zeta } \left (1 - \left ( \frac { (\zeta '-q) (\zeta '-q)}{(\zeta '-a) (\zeta '-\bar {a})} \right )^{\frac {1}{2}} \right ) \frac {\mathrm{d}\zeta '}{\zeta '} , \end{align}

and the coefficient

![]() $\alpha$

$\alpha$

\begin{align} \alpha = \frac {R_1 \lambda _1}{R_1 \lambda _1 + \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_1(q)]}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \alpha = \frac {R_1 \lambda _1}{R_1 \lambda _1 + \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_1(q)]}. \end{align}

Here,

![]() $\lambda _1$

denotes the aforementioned finite local slit length defined at the slit centre. The coordinate

$\lambda _1$

denotes the aforementioned finite local slit length defined at the slit centre. The coordinate

![]() $\zeta = z^N$

takes values from the unit disc and

$\zeta = z^N$

takes values from the unit disc and

![]() $a=R_1^N e^{i\theta }$

and

$a=R_1^N e^{i\theta }$

and

![]() $q=R_1^N$

. The angle

$q=R_1^N$

. The angle

![]() $\theta = \phi N$

denotes the half-opening angle of the finite-shear slit in the

$\theta = \phi N$

denotes the half-opening angle of the finite-shear slit in the

![]() $\zeta$

plane. For visual depition, see figure 8(e). The velocity field is normalised with respect to

$\zeta$

plane. For visual depition, see figure 8(e). The velocity field is normalised with respect to

![]() $\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2 /\hat {\mu }_1$

, with the negative pressure gradient

$\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2 /\hat {\mu }_1$

, with the negative pressure gradient

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p}_1=-\hat {s}_1$

. It should be mentioned at this point that the notations of (2.1) and (2.3) are chosen to be consistent with the rest of this work, but thus deviate from the authors’ original study (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). The expression

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p}_1=-\hat {s}_1$

. It should be mentioned at this point that the notations of (2.1) and (2.3) are chosen to be consistent with the rest of this work, but thus deviate from the authors’ original study (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). The expression

![]() $\textrm {Re}[I_1(q)]$

refers to the real part of the integral

$\textrm {Re}[I_1(q)]$

refers to the real part of the integral

![]() $I_1(\zeta )$

evaluated at the centre of the slit, corresponding to

$I_1(\zeta )$

evaluated at the centre of the slit, corresponding to

![]() $\zeta =q$

. Considering the shear-free limit of (2.1), i.e.

$\zeta =q$

. Considering the shear-free limit of (2.1), i.e.

![]() $\lambda _1 \rightarrow \infty$

, corresponding to

$\lambda _1 \rightarrow \infty$

, corresponding to

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow 1$

, and comparing this limit with the special values provided by Philip (Reference Philip1972a

), one easily determines that

$\alpha \rightarrow 1$

, and comparing this limit with the special values provided by Philip (Reference Philip1972a

), one easily determines that

which is a useful identity to be used later on.

2.1.2. Shear-driven solution

Now the case of rotationally symmetric shear-imposing slits in a pipe with arbitrary outer radius

![]() $R_1$

is considered. This specifically means that the velocity field in question does not necessarily possess an externally induced pressure gradient, i.e.

$R_1$

is considered. This specifically means that the velocity field in question does not necessarily possess an externally induced pressure gradient, i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p} =0$

, but that all forces on the fluid are induced by a shear stress at the slit boundary parts of an otherwise no-slip wall. It is important to note that the lubricant is subject to the influence of its own solid domain walls, which will inevitably result in a downstream pressure drop (in the

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p} =0$

, but that all forces on the fluid are induced by a shear stress at the slit boundary parts of an otherwise no-slip wall. It is important to note that the lubricant is subject to the influence of its own solid domain walls, which will inevitably result in a downstream pressure drop (in the

![]() $Z$

direction). The magnitude and therefore the significance of this pressure drop will depend on the geometry of the outer pipe, in particular whether the outer pipe is open to the environment, i.e. if the flow is unidirectional, or whether it is closed at the ends, which would force the fluid in the outer pipe to recirculate. In the latter case, the pressure drop is significant. Within the course of this work, we consider the outer pipe to be open (meaning infinite in

$Z$

direction). The magnitude and therefore the significance of this pressure drop will depend on the geometry of the outer pipe, in particular whether the outer pipe is open to the environment, i.e. if the flow is unidirectional, or whether it is closed at the ends, which would force the fluid in the outer pipe to recirculate. In the latter case, the pressure drop is significant. Within the course of this work, we consider the outer pipe to be open (meaning infinite in

![]() $Z$

direction), as depicted in figure 1, so that the pressure drop is not crucial. Furthermore, in the subsequent analysis, it is assumed that the surface tension of the interface is sufficiently high to prevent any additional significant interfacial deflection as a result of any pressure gradient. If, contrary to the assumptions made here, the consideration of a pressure drop must be taken into account, the shear-driven flow derived here may be linearly superimposed with the corresponding pressure-driven variant (see § 2.1.1).

$Z$

direction), as depicted in figure 1, so that the pressure drop is not crucial. Furthermore, in the subsequent analysis, it is assumed that the surface tension of the interface is sufficiently high to prevent any additional significant interfacial deflection as a result of any pressure gradient. If, contrary to the assumptions made here, the consideration of a pressure drop must be taken into account, the shear-driven flow derived here may be linearly superimposed with the corresponding pressure-driven variant (see § 2.1.1).

Using a limit value of the constant-shear solution presented in § 2.1.1 and combining it with another available solution already present in the literature, it is straightforward to derive the aforementioned shear-driven inner pipe solution. In fact, it follows from

where

![]() $\gamma _1$

is a scaling constant,

$\gamma _1$

is a scaling constant,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_1$

is the dimensional constant-shear stress acting on each slit and

$\hat {\tau }_1$

is the dimensional constant-shear stress acting on each slit and

![]() $\hat {s}_1$

denotes the pressure gradient in the

$\hat {s}_1$

denotes the pressure gradient in the

![]() $Z$

direction. The shear-driven solution is simply a linear combination of the well-known pressure-driven Poiseuille flow through a pipe with outer radius

$Z$

direction. The shear-driven solution is simply a linear combination of the well-known pressure-driven Poiseuille flow through a pipe with outer radius

![]() $R_1$

(remember that, for such a flow field, the outer wall is assumed to be a no-slip solid wall)

$R_1$

(remember that, for such a flow field, the outer wall is assumed to be a no-slip solid wall)

and Philips aforementioned no-shear solution, which is simply the limit case

![]() $\lambda \to \infty$

of (2.1), given as

$\lambda \to \infty$

of (2.1), given as

Combining (2.5), (2.6) and (2.7) we get

By choosing

![]() $\gamma _1$

to be the shear stress imposed by (2.6) along the slit parts on

$\gamma _1$

to be the shear stress imposed by (2.6) along the slit parts on

![]() $R_1$

, we get the final shear-driven solution

$R_1$

, we get the final shear-driven solution

Figure 2 illustrates the contour lines of the velocity fields defined in (2.1) and (2.9) independently of each other. Thereby, figures 2(a) and 2(b) show shear-driven pipe flow as a function of an exemplary shear rate

![]() $c_1$

. Panels (c) and (d), on the other hand, illustrate the contour lines of the pressure-driven flow as a function of an arbitrarily selected local slip length

$c_1$

. Panels (c) and (d), on the other hand, illustrate the contour lines of the pressure-driven flow as a function of an arbitrarily selected local slip length

![]() $\lambda _1$

. Note that (c) and (d) furthermore do not depend on the magnitude of the pressure gradient because

$\lambda _1$

. Note that (c) and (d) furthermore do not depend on the magnitude of the pressure gradient because

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p}$

is part of the non-dimensionalisation, but rather on the degree to which the flow is held back at the boundaries, namely by the shear stress at the slits.

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p}$

is part of the non-dimensionalisation, but rather on the degree to which the flow is held back at the boundaries, namely by the shear stress at the slits.

Figure 2. Shows the normalised axial velocity contour lines for the fundamental solutions presented and derived for the inner pipe flow in § 2.1. The upper row shows the lubricant flow from (2.9), the lower covers the pressure-driven flow given by (2.1). (a) Shows the velocity field of a pipe with two shear-imposing slits (

![]() $c_1=1$

), with an inner radius

$c_1=1$

), with an inner radius

![]() $R_1=0.5$

and

$R_1=0.5$

and

![]() $\theta =\pi / 4$

. (b) Shear-driven velocity field:

$\theta =\pi / 4$

. (b) Shear-driven velocity field:

![]() $c_1=1, N=3, R_1=0.5, \theta = \pi / 4$

. (c) Shows the pressure-driven counterpart of (a), employing

$c_1=1, N=3, R_1=0.5, \theta = \pi / 4$

. (c) Shows the pressure-driven counterpart of (a), employing

![]() $\lambda _1=0.1$

. (d) Pressure-driven flow with

$\lambda _1=0.1$

. (d) Pressure-driven flow with

![]() $\lambda _1=0.1, N=3, R_1=0.5, \theta = \pi / 4$

.

$\lambda _1=0.1, N=3, R_1=0.5, \theta = \pi / 4$

.

2.2. Outer annular flow

Now that both the pressure-driven (§ 2.1.1) and the shear-driven (§ 2.1.2) solutions for the inner pipe flow have been derived and presented, the following section is devoted to the same basic approach, but in contrast for the outer pipe flow. The objective is to continue to generate the necessary fundamental solutions for the complete description of the coupled ‘pipe-within-pipe’ scenario, as illustrated in figure 1.

2.2.1. Pressure-driven finite-shear annular solution

The first fundamental annular solution is the pressure-driven flow through an annulus with

![]() $N$

rotationally symmetric finite-shear slits along the inner wall. Analogous to § 2.1.1, this solution has already been derived in an earlier work by the authors and will therefore only be briefly presented. It is based on a linear combination of

$N$

rotationally symmetric finite-shear slits along the inner wall. Analogous to § 2.1.1, this solution has already been derived in an earlier work by the authors and will therefore only be briefly presented. It is based on a linear combination of

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

(Crowdy Reference Crowdy2021) and

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

(Crowdy Reference Crowdy2021) and

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

. For a detailed derivation and discussion, see Zimmermann & Schönecker (Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). The flow field, being normalised with respect to

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

. For a detailed derivation and discussion, see Zimmermann & Schönecker (Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). The flow field, being normalised with respect to

![]() $\hat {s}_2 \hat {R}_0^2 / \hat {\mu }_2$

is given by

$\hat {s}_2 \hat {R}_0^2 / \hat {\mu }_2$

is given by

again using a slightly different notation to the original work. The integral

![]() $I_{2,p}(\zeta )$

is defined as

$I_{2,p}(\zeta )$

is defined as

\begin{align} I_{2,p}(\zeta ) = \int _{-1}^{\zeta } \left [1- \frac {\dfrac {1}{R_1^2} + 2 \ln (R_1)-1}{2 S} \left ( \frac {P\left ( \zeta '/q,q \right ) P\left ( \zeta '/q,q\right ) }{P\left ( \zeta '/a,q\right ) P\left ( \zeta '/\bar {a},q\right )}\right )^{1/2} \right ] \frac {\mathrm{d} \zeta '}{\zeta '}, \end{align}

\begin{align} I_{2,p}(\zeta ) = \int _{-1}^{\zeta } \left [1- \frac {\dfrac {1}{R_1^2} + 2 \ln (R_1)-1}{2 S} \left ( \frac {P\left ( \zeta '/q,q \right ) P\left ( \zeta '/q,q\right ) }{P\left ( \zeta '/a,q\right ) P\left ( \zeta '/\bar {a},q\right )}\right )^{1/2} \right ] \frac {\mathrm{d} \zeta '}{\zeta '}, \end{align}

with

![]() $S$

defined as

$S$

defined as

In contrast to comparable shear-free solutions, this pressure-driven flow experiences a finite-shear stress along the slits on

![]() $|z|=R_1$

. Therefore, it does not slide perfectly over these areas but rather experiences resistance. This viscous interaction is modelled using a local slip length

$|z|=R_1$

. Therefore, it does not slide perfectly over these areas but rather experiences resistance. This viscous interaction is modelled using a local slip length

![]() $\lambda _2$

, which is defined in the centre of the slit at

$\lambda _2$

, which is defined in the centre of the slit at

![]() $\zeta =q$

. The local slip length

$\zeta =q$

. The local slip length

![]() $\lambda _2$

is incorporated using the coefficient

$\lambda _2$

is incorporated using the coefficient

![]() $\beta$

, which is defined as

$\beta$

, which is defined as

\begin{align} \beta = \frac {\lambda _2 \left (R_1^2+2 R_1^2 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) -1 \right ) }{ R_1^2 \lambda _2 - \lambda _2 + R_1 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) \bigg (R_1^2-2 \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_{2,p}(q)] + 2 \lambda _2 R_1 -1 \bigg ) }, \end{align}

\begin{align} \beta = \frac {\lambda _2 \left (R_1^2+2 R_1^2 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) -1 \right ) }{ R_1^2 \lambda _2 - \lambda _2 + R_1 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) \bigg (R_1^2-2 \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_{2,p}(q)] + 2 \lambda _2 R_1 -1 \bigg ) }, \end{align}

with

![]() $\textrm {Re}[I_{2,p}(q)]$

being the real part of the integral

$\textrm {Re}[I_{2,p}(q)]$

being the real part of the integral

![]() $I_{2,p}(\zeta )$

evaluated at the slit centre corresponding to

$I_{2,p}(\zeta )$

evaluated at the slit centre corresponding to

![]() $\zeta =q$

. When considering very high local slip lengths

$\zeta =q$

. When considering very high local slip lengths

![]() $\lambda _2 \rightarrow \infty$

, it is easy to identify that

$\lambda _2 \rightarrow \infty$

, it is easy to identify that

![]() $\beta \rightarrow 1$

and thus (2.10) transitions into the shear-free solution provided by Crowdy (Reference Crowdy2021).

$\beta \rightarrow 1$

and thus (2.10) transitions into the shear-free solution provided by Crowdy (Reference Crowdy2021).

The contour lines of the annular flow fields are illustrated in figure 3. Panels (a) and (b) show the purely shear-driven solution from (2.17) for some shear rate

![]() $c_2$

. The last two panels, i.e. (c) and (d), on the other hand, illustrate the pressure-driven flow through an annulus for a finite local slip length

$c_2$

. The last two panels, i.e. (c) and (d), on the other hand, illustrate the pressure-driven flow through an annulus for a finite local slip length

![]() $\lambda _2$

.

$\lambda _2$

.

Figure 3. Illustrates the normalised axial velocity contour lines for the fundamental solutions presented and derived for the annular pipe in § 2.2. Similar to figure 2, the upper row shows the lubricant flow from (2.17), the lower covers the pressure-driven flow given by (2.10). (a) Shows the velocity field of an annular pipe with two shear-imposing slits (

![]() $c_2=1$

), with an inner radius

$c_2=1$

), with an inner radius

![]() $R_1=0.3$

and

$R_1=0.3$

and

![]() $\theta =\pi / 2$

. (b) Shear-driven velocity field:

$\theta =\pi / 2$

. (b) Shear-driven velocity field:

![]() $c_2=1, N=3, R_1=0.7, \theta = \pi / 4$

. (c) Shows the pressure-driven annular flow employing

$c_2=1, N=3, R_1=0.7, \theta = \pi / 4$

. (c) Shows the pressure-driven annular flow employing

![]() $\lambda _2=3, N=4, R_1 = 0.4$

and

$\lambda _2=3, N=4, R_1 = 0.4$

and

![]() $\theta = \pi / 4$

. (d) Pressure-driven flow with

$\theta = \pi / 4$

. (d) Pressure-driven flow with

![]() $\lambda _2=3, N=6, R_1=0.6, \theta = \pi / 3$

.

$\lambda _2=3, N=6, R_1=0.6, \theta = \pi / 3$

.

2.2.2. Shear-driven solution

A concentric annulus with inner radius

![]() $R_1$

is considered, featuring

$R_1$

is considered, featuring

![]() $N$

rotationally symmetric shear-inducing slits on an otherwise no-slip solid inner wall, with the latter condition also applying for the whole outer wall with radius

$N$

rotationally symmetric shear-inducing slits on an otherwise no-slip solid inner wall, with the latter condition also applying for the whole outer wall with radius

![]() $1$

. The shear boundary segments again have a spanning angle of

$1$

. The shear boundary segments again have a spanning angle of

![]() $2 \phi$

in the

$2 \phi$

in the

![]() $z$

plane. Analogous to § 2.1.2, we assume that the flow field is not subject to any pressure gradient, i.e.

$z$

plane. Analogous to § 2.1.2, we assume that the flow field is not subject to any pressure gradient, i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p}_2 = 0$

, and is characterised within the same Cartesian coordinate system

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\hat {p}_2 = 0$

, and is characterised within the same Cartesian coordinate system

![]() $(x,y,Z)$

as before. The annular flow, therefore, is solely driven by a constant-shear stress, represented by the shear rate

$(x,y,Z)$

as before. The annular flow, therefore, is solely driven by a constant-shear stress, represented by the shear rate

![]() $c_2$

, acting on the slit segments featured on the inner wall at

$c_2$

, acting on the slit segments featured on the inner wall at

![]() $|z|=R_1$

, which drags the viscous fluid along with it.

$|z|=R_1$

, which drags the viscous fluid along with it.

Similar to § 2.1.2, the shear-driven solution can be obtained by a combination of two already known and readily available solutions, using

with the shear stress

![]() $\hat {\tau }_2$

and downstream pressure gradient

$\hat {\tau }_2$

and downstream pressure gradient

![]() $\hat {s}_2$

, respectively. The parameter

$\hat {s}_2$

, respectively. The parameter

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

denotes the no-shear solution derived by Crowdy (Reference Crowdy2021), which is simply the dimensional limit

$\hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}}$

denotes the no-shear solution derived by Crowdy (Reference Crowdy2021), which is simply the dimensional limit

![]() $\lambda \to \infty$

of the constant-shear solution given in (2.10), such that

$\lambda \to \infty$

of the constant-shear solution given in (2.10), such that

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {1-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {R_1^2}{2 N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] \right ) \! , \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{\textit{Cro}w\textit{dy}} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {1-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {R_1^2}{2 N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] \right ) \! , \end{align}

with

![]() $I_{2,p}$

defined in (2.11). The second velocity field in (2.14),

$I_{2,p}$

defined in (2.11). The second velocity field in (2.14),

![]() $\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

, refers to the annular Poiseuille flow, where both the inner boundary at

$\hat {w}_{\textit{PA}}$

, refers to the annular Poiseuille flow, where both the inner boundary at

![]() $|z| = R_1$

and the outer at

$|z| = R_1$

and the outer at

![]() $|z| = 1$

are modelled as pure no-slip walls. It is given by

$|z| = 1$

are modelled as pure no-slip walls. It is given by

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{\textit{PA}} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {1-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {1 - R^2_1}{4} \frac {\ln |z|}{\ln (R_1)} \right ) \!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{\textit{PA}} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {1-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {1 - R^2_1}{4} \frac {\ln |z|}{\ln (R_1)} \right ) \!. \end{align}

Equation (2.14) therefore yields

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{2,s} = \gamma _2 \frac {\hat {\tau }_2 \hat {R_0}}{\hat {\mu }_2} \left ( \frac {1 - R^2_1}{4} \frac {\ln |z|}{\ln (R_1)} + \frac {R_1^2}{2 N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] \right )\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{2,s} = \gamma _2 \frac {\hat {\tau }_2 \hat {R_0}}{\hat {\mu }_2} \left ( \frac {1 - R^2_1}{4} \frac {\ln |z|}{\ln (R_1)} + \frac {R_1^2}{2 N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] \right )\!, \end{align}

where we choose

![]() $\gamma _2$

to be the shear stress imposed by the annular Poiseuille flow along the rotationally symmetric slits on

$\gamma _2$

to be the shear stress imposed by the annular Poiseuille flow along the rotationally symmetric slits on

![]() $|z| = R_1$

, so that

$|z| = R_1$

, so that

\begin{align} \gamma _2 = \left ( -\frac {R_1^2}{2} + \frac {R_1^2-1}{4 R_1 \ln (R_1)} \right )^{-1} \! . \end{align}

\begin{align} \gamma _2 = \left ( -\frac {R_1^2}{2} + \frac {R_1^2-1}{4 R_1 \ln (R_1)} \right )^{-1} \! . \end{align}

3. Coupled flow fields – pipe in a pipe

The objective of this section is to examine the case of two mutually interacting flow fields in which one is pressure driven and the other is dragged along the interface, thus acting as a lubricant, as illustrated in figure 1. The two domains, i.e. inner and outer pipes, are connected by longitudinal slits along the inner wall, shown in the

![]() $(x,y)$

cross-section as red circular arcs on

$(x,y)$

cross-section as red circular arcs on

![]() $|z|=R_1$

. It is therefore obvious, that each flow field is heavily influenced by the other. The pressure-driven flow has a non-zero velocity at these slit parts and thus reduces its resistance, but carries the other (non-pressure-driven) flow along with it at the interface, imposing a shear stress onto the latter.

$|z|=R_1$

. It is therefore obvious, that each flow field is heavily influenced by the other. The pressure-driven flow has a non-zero velocity at these slit parts and thus reduces its resistance, but carries the other (non-pressure-driven) flow along with it at the interface, imposing a shear stress onto the latter.

Depending on the viscosity ratio, flow resistance can thus be significantly reduced. This effect is purposefully utilised for SHS and LIS, for example. This usually involves air being enclosed within the lubricant domain, as its low viscosity promises almost frictionless slippage along the interface. To approximate the velocity field, drag reduction as well as other quantities, models are often used which assume the viscous interaction to be shear free, as discussed earlier. However, the purpose of this work is not to consider shear-free interfaces, but rather to represent these interactions as a function of fluid properties and geometry. As previously discussed, this is achieved using a local slip length (

![]() $\lambda _1$

or

$\lambda _1$

or

![]() $\lambda _2$

), which models the influence of the shear-driven fluid as an input factor to the respective pressure-driven velocity fields. This then enables the previous models to be generalised to any Newtonian fluid being enclosed within the framework of pipes in pipes. Shear-free models then represent a useful limit for very high viscosity ratios. Figure 4 illustrates the coupling of both flow fields, their mutual dependencies on the quantities

$\lambda _2$

), which models the influence of the shear-driven fluid as an input factor to the respective pressure-driven velocity fields. This then enables the previous models to be generalised to any Newtonian fluid being enclosed within the framework of pipes in pipes. Shear-free models then represent a useful limit for very high viscosity ratios. Figure 4 illustrates the coupling of both flow fields, their mutual dependencies on the quantities

![]() $\lambda (\hat {\tau })$

and

$\lambda (\hat {\tau })$

and

![]() $\hat {\tau }(\lambda )$

as well as the coupling conditions

$\hat {\tau }(\lambda )$

as well as the coupling conditions

where the first condition dictates the equality of both velocities at a single point

![]() $z=R_1$

(or

$z=R_1$

(or

![]() $\zeta =q$

) and the second defines the driving shear stress

$\zeta =q$

) and the second defines the driving shear stress

![]() $\tau _s$

as a function of the pressure-driven flow (subscript

$\tau _s$

as a function of the pressure-driven flow (subscript

![]() $p$

) on the interface. We require the surface tension to be high and the pressure drop along the

$p$

) on the interface. We require the surface tension to be high and the pressure drop along the

![]() $Z$

-axis sufficiently low such that no additional protrusion of the interface beyond its current circular shape is considered. Therefore, the shape of the interface is assumed to be quasi-constant, with the radius of curvature set to be

$Z$

-axis sufficiently low such that no additional protrusion of the interface beyond its current circular shape is considered. Therefore, the shape of the interface is assumed to be quasi-constant, with the radius of curvature set to be

![]() $R_1$

. We further assume that the inner wall and all interfaces are infinitely thin. In the previous § 2, only dimensionless variables and equations were considered. This has contributed to the clarity of the derivations made, but is no longer appropriate for the considerations below. For that reason, the governing dimensional equations are introduced at the beginning of each subsection.

$R_1$

. We further assume that the inner wall and all interfaces are infinitely thin. In the previous § 2, only dimensionless variables and equations were considered. This has contributed to the clarity of the derivations made, but is no longer appropriate for the considerations below. For that reason, the governing dimensional equations are introduced at the beginning of each subsection.

Figure 4. Shows the connection at point

![]() $z = R_1$

(green cross) of the discussed and derived fundamental solutions (see § 2) for fluid regions 1 (inner pipe) and 2 (outer pipe), subject to the stated boundary conditions, as performed in § 3. The reciprocal influence of the individual flows on their respective counterpart is also shown, i.e. that

$z = R_1$

(green cross) of the discussed and derived fundamental solutions (see § 2) for fluid regions 1 (inner pipe) and 2 (outer pipe), subject to the stated boundary conditions, as performed in § 3. The reciprocal influence of the individual flows on their respective counterpart is also shown, i.e. that

![]() $\lambda (\hat {\tau })$

and

$\lambda (\hat {\tau })$

and

![]() $\hat {\tau }(\lambda )$

.

$\hat {\tau }(\lambda )$

.

We will examine two fundamental cases: (i) in § 3.1 the case, in which the inner flow is pressure driven and the outer shear driven (see figure 1 a). (ii) Similarly, as illustrated in figure 1(b), the case in which the inner flow is dragged along by an outer pressure-driven flow field, in § 3.2.

3.1. Coupling – case 1

Case 1, as illustrated in figure 1(a), describes the scenario in which a pressure-driven inner pipe flow (subscript 1) drags an outer fluid (subscript 2) along

![]() $N$

equally distributed interfaces, which are scattered across the inner wall. The equations governing the flow fields are

$N$

equally distributed interfaces, which are scattered across the inner wall. The equations governing the flow fields are

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{1,p} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {R_1^2-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {\alpha }{2} \frac {R_1^2}{N} \ \textrm {Re} \left [ I_1(\zeta ) \right ] \right ) \!, \\[-28pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{1,p} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {R_1^2-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {\alpha }{2} \frac {R_1^2}{N} \ \textrm {Re} \left [ I_1(\zeta ) \right ] \right ) \!, \\[-28pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{2,s} = \gamma _2 \frac {\hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) \hat {R_0}}{\hat {\mu }_2} \left ( \frac {1 - R^2_1}{4} \frac {\ln |z|}{\ln (R_1)} + \frac {R_1^2}{2 N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] \right ) \! , \\[2pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{2,s} = \gamma _2 \frac {\hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) \hat {R_0}}{\hat {\mu }_2} \left ( \frac {1 - R^2_1}{4} \frac {\ln |z|}{\ln (R_1)} + \frac {R_1^2}{2 N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] \right ) \! , \\[2pt] \nonumber \end{align}

where

![]() $\hat {s}_1$

and

$\hat {s}_1$

and

![]() $\hat {\mu }_1$

denote the pressure gradient and dynamic viscosity of the inner pipe flow. The quotient

$\hat {\mu }_1$

denote the pressure gradient and dynamic viscosity of the inner pipe flow. The quotient

![]() $\hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) / \hat {\mu }_2$

denotes the shear rate, where the numerator is the driving shear stress as a function of the local slip length

$\hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) / \hat {\mu }_2$

denotes the shear rate, where the numerator is the driving shear stress as a function of the local slip length

![]() $\lambda _1$

and the denominator refers to the dynamic viscosity of the outer fluid. Here,

$\lambda _1$

and the denominator refers to the dynamic viscosity of the outer fluid. Here,

![]() $\hat {R}_0$

is a characterising length scale of both flow domains and is chosen to be the dimensional radius of the outer tube. It must be emphasised that all quantities without a ‘hat’ are still dimensionless. The integrals

$\hat {R}_0$

is a characterising length scale of both flow domains and is chosen to be the dimensional radius of the outer tube. It must be emphasised that all quantities without a ‘hat’ are still dimensionless. The integrals

![]() $I_1(\zeta )$

and

$I_1(\zeta )$

and

![]() $I_{2,p}(\zeta )$

are given by (2.2) and (2.11), respectively. Coefficient

$I_{2,p}(\zeta )$

are given by (2.2) and (2.11), respectively. Coefficient

![]() $\alpha$

is still defined as

$\alpha$

is still defined as

\begin{align} \alpha = \frac {R_1 \lambda _1(k)}{R_1 \lambda _1(k) + \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_1(q)]}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \alpha = \frac {R_1 \lambda _1(k)}{R_1 \lambda _1(k) + \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_1(q)]}, \end{align}

however, now with the local slip length depending on the viscosity ratio

![]() $k= \hat {\mu }_1 / \hat {\mu }_2$

and with

$k= \hat {\mu }_1 / \hat {\mu }_2$

and with

![]() $\gamma _1$

defined in (2.18). The coefficients

$\gamma _1$

defined in (2.18). The coefficients

![]() $\lambda _1(k)$

and

$\lambda _1(k)$

and

![]() $\hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1)$

must now be determined. For that, we impose the conditions

$\hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1)$

must now be determined. For that, we impose the conditions

at

![]() $z=R_1$

. Both required coefficients are readily found. The local slip length of the pressure-driven inner flow as a function of the viscosity ratio

$z=R_1$

. Both required coefficients are readily found. The local slip length of the pressure-driven inner flow as a function of the viscosity ratio

![]() $k$

is

$k$

is

where the integral

![]() $ [ I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ]$

is evaluated at the slit centre

$ [ I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ]$

is evaluated at the slit centre

![]() $\zeta = q$

. Equation (3.6) can be rewritten such that

$\zeta = q$

. Equation (3.6) can be rewritten such that

The integral

![]() $I_{2,s}(q)$

is defined as

$I_{2,s}(q)$

is defined as

\begin{align} I_{2,s}(\zeta ) = \int _{-1}^{\zeta } \Bigg [ 1 - \frac {\ln (R_1)}{S} \left ( \frac {P\left ( \zeta '/q,q \right ) P\left ( \zeta '/q,q\right ) }{P\left ( \zeta '/a,q\right ) P\left ( \zeta '/\bar {a},q\right )}\right )^{1/2} \Bigg ] \frac {\mathrm{d} \zeta '}{\zeta '}, \end{align}

\begin{align} I_{2,s}(\zeta ) = \int _{-1}^{\zeta } \Bigg [ 1 - \frac {\ln (R_1)}{S} \left ( \frac {P\left ( \zeta '/q,q \right ) P\left ( \zeta '/q,q\right ) }{P\left ( \zeta '/a,q\right ) P\left ( \zeta '/\bar {a},q\right )}\right )^{1/2} \Bigg ] \frac {\mathrm{d} \zeta '}{\zeta '}, \end{align}

with

![]() $S$

from (2.12).

$S$

from (2.12).

The shear stress imposed on the outer fluid at the interface is identified to be defined as

\begin{align} & \scriptsize \hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) \nonumber \\ & = \hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0 \frac {\hat {\mu }_2 R_1 \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] (1-R_1^2 + 2 R_1^3 \ln (R_1))}{\big ( 4 R_1^2 (\hat {\mu }_1 \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)] + \hat {\mu }_2 R_1 \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)]) - 2 \hat {\mu }_1 N (R_1^2 - 1) \big ) \ln (R_1) - 2 \hat {\mu }_2 \textrm {Re} [ I_{1}(q)] (R_1^2-1)}, \end{align}

\begin{align} & \scriptsize \hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) \nonumber \\ & = \hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0 \frac {\hat {\mu }_2 R_1 \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] (1-R_1^2 + 2 R_1^3 \ln (R_1))}{\big ( 4 R_1^2 (\hat {\mu }_1 \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)] + \hat {\mu }_2 R_1 \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)]) - 2 \hat {\mu }_1 N (R_1^2 - 1) \big ) \ln (R_1) - 2 \hat {\mu }_2 \textrm {Re} [ I_{1}(q)] (R_1^2-1)}, \end{align}

or alternatively written down as

\begin{align} \hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) = \hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0 \frac {R_1}{2} \frac { \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]}{ \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] + \dfrac {N}{R_1} \lambda _1(k)} = \hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0 \frac {R_1}{2} \frac { \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]}{ \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]- \dfrac {\hat {\mu }_1}{\hat {\mu }_2} \textrm {Re} [I_{2,s}(q)]} , \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {\tau }_2(\lambda _1) = \hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0 \frac {R_1}{2} \frac { \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]}{ \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] + \dfrac {N}{R_1} \lambda _1(k)} = \hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0 \frac {R_1}{2} \frac { \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]}{ \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]- \dfrac {\hat {\mu }_1}{\hat {\mu }_2} \textrm {Re} [I_{2,s}(q)]} , \end{align}

including the integral

![]() $I_{1}(q)$

evaluated at

$I_{1}(q)$

evaluated at

![]() $\zeta =q$

. Case 1 is therefore fully described. The coupled velocity fields are then given by

$\zeta =q$

. Case 1 is therefore fully described. The coupled velocity fields are then given by

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{1,p} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {R_1^2-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {R_1^2}{2N} \frac {\textrm {Re} [I_{2,s}(q)]}{\textrm {Re} [I_{2,s}(q)] - \dfrac {1}{k} \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]} \textrm {Re} \left [ I_1(\zeta ) \right ] \right ) \!, \\[-28pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{1,p} = \frac {\hat {s}_1 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_1} \left ( \frac {R_1^2-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {R_1^2}{2N} \frac {\textrm {Re} [I_{2,s}(q)]}{\textrm {Re} [I_{2,s}(q)] - \dfrac {1}{k} \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)]} \textrm {Re} \left [ I_1(\zeta ) \right ] \right ) \!, \\[-28pt] \nonumber \end{align}

where

![]() $\hat {w}_{2,s}$

was rewritten in terms of the integral

$\hat {w}_{2,s}$

was rewritten in terms of the integral

![]() $I_{2,s}(\zeta )$

. With the provided equations it is now possible to calculate both velocity fields individually as a function of each other. The velocity fields are now described purely as a function of the geometrical and fluid properties, such as viscosities

$I_{2,s}(\zeta )$

. With the provided equations it is now possible to calculate both velocity fields individually as a function of each other. The velocity fields are now described purely as a function of the geometrical and fluid properties, such as viscosities

![]() $\hat {\mu }_1$

and

$\hat {\mu }_1$

and

![]() $\hat {\mu }_2$

, number of slits and geometry parameters (i.e. the radii) as well as, of course, as the driving pressure gradient

$\hat {\mu }_2$

, number of slits and geometry parameters (i.e. the radii) as well as, of course, as the driving pressure gradient

![]() $\hat {s}_1$

. The quantities

$\hat {s}_1$

. The quantities

![]() $\hat {\tau }_2$

and

$\hat {\tau }_2$

and

![]() $\lambda _1(k)$

employed for modelling disappear. In case one wishes to optimise drag reduction, (3.7) can be employed to find certain set of parameters to maximise the slip length

$\lambda _1(k)$

employed for modelling disappear. In case one wishes to optimise drag reduction, (3.7) can be employed to find certain set of parameters to maximise the slip length

![]() $\lambda$

.

$\lambda$

.

3.2. Coupling – case 2

Now let us examine the exact opposite case to § 3.1. Therefore, we consider a pressure-driven annular flow that drags a fluid in the inner pipe along its

![]() $N$

rotationally symmetric slits, hereinafter referred to as case 2, as illustrated in figure 1(b). Indices 1 and 2 still refer to the inner and outer domains, respectively. Again, we introduce the dimensional velocity field equations

$N$

rotationally symmetric slits, hereinafter referred to as case 2, as illustrated in figure 1(b). Indices 1 and 2 still refer to the inner and outer domains, respectively. Again, we introduce the dimensional velocity field equations

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{2,p} = \frac {\hat {s}_2 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_2} \left ( \frac {1-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {\beta }{2} \frac {R_1^2}{N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] - (1-\beta ) \frac {\left ( 1-R^2_1\right )}{4} \frac {\ln (|z|)}{\ln (R_1)} \right ) \! , \\[2pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \hat {w}_{2,p} = \frac {\hat {s}_2 \hat {R}_0^2}{\hat {\mu }_2} \left ( \frac {1-|z|^2}{4} + \frac {\beta }{2} \frac {R_1^2}{N} \ \textrm {Re} [I_{2,p}(\zeta ) ] - (1-\beta ) \frac {\left ( 1-R^2_1\right )}{4} \frac {\ln (|z|)}{\ln (R_1)} \right ) \! , \\[2pt] \nonumber \end{align}

with the shear stress

![]() $\hat {\tau }_1$

as a function of the outer local slip length

$\hat {\tau }_1$

as a function of the outer local slip length

![]() $\lambda _2$

. Both integrals

$\lambda _2$

. Both integrals

![]() $I_1(\zeta )$

and

$I_1(\zeta )$

and

![]() $I_{2,p}$

are defined by (2.2) and (2.11), respectively. The coefficient

$I_{2,p}$

are defined by (2.2) and (2.11), respectively. The coefficient

![]() $\beta$

is again defined as

$\beta$

is again defined as

\begin{align} \beta = \frac {\lambda _2(k) \left (R_1^2+2 R_1^2 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) -1 \right ) }{ \left [ R_1^2 \lambda _2(k) - \lambda _2(k) + R_1 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) \bigg (R_1^2-2 \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_{2,p}(q)] + 2 \lambda _2(k) R_1 -1 \bigg ) \right ] }. \end{align}

\begin{align} \beta = \frac {\lambda _2(k) \left (R_1^2+2 R_1^2 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) -1 \right ) }{ \left [ R_1^2 \lambda _2(k) - \lambda _2(k) + R_1 \ln \left (\dfrac {1}{R_1} \right ) \bigg (R_1^2-2 \dfrac {R_1^2}{N} \textrm {Re}[I_{2,p}(q)] + 2 \lambda _2(k) R_1 -1 \bigg ) \right ] }. \end{align}

The two coupling parameters

![]() $\hat {\tau }_1(\lambda _2)$

and

$\hat {\tau }_1(\lambda _2)$

and

![]() $\lambda _2(k)$

must now be determined again. For this purpose, the following boundary conditions are imposed:

$\lambda _2(k)$

must now be determined again. For this purpose, the following boundary conditions are imposed:

where the first boundary condition again sets equality of velocities at the interfaces. The second establishes a relationship between the two shear stresses on the boundary at

![]() $z=R_1$

. Notice that we consider the positive normal derivative in (3.16b

), as we define the normal vector to be pointing outwards (see also (3.5b

)). Accordingly, we define the shear stress

$z=R_1$

. Notice that we consider the positive normal derivative in (3.16b

), as we define the normal vector to be pointing outwards (see also (3.5b

)). Accordingly, we define the shear stress

![]() $\hat {\tau }_1$

as negative. With both conditions at hand, the sought coefficients are readily determined. The local slip length for the annular flow as a function of the viscosity ration

$\hat {\tau }_1$

as negative. With both conditions at hand, the sought coefficients are readily determined. The local slip length for the annular flow as a function of the viscosity ration

![]() $k$

is

$k$

is

The shear stress imposed onto the inner fluid domain is given by

\begin{align} & \hat {\tau }_1 = \frac {\hat {s}_2 \hat {R_0} \hat {\mu }_1 \big ( R_1^2 N - N - 2 R_1^2 \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)] \big ) \big ( 1- R_1^2 + 2 R_1^2 \ln (R_1) \big )}{4 \ln (R_1) \big ( N R_1 \hat {\mu }_1 (R_1^2-1) + 2 R_1^3 \big (\textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] \hat {\mu }_2 - \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)] \hat {\mu }_1 \big ) \big ) - 4 R_1 \hat {\mu }_2 \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] (R_1^2-1)}, \end{align}

\begin{align} & \hat {\tau }_1 = \frac {\hat {s}_2 \hat {R_0} \hat {\mu }_1 \big ( R_1^2 N - N - 2 R_1^2 \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)] \big ) \big ( 1- R_1^2 + 2 R_1^2 \ln (R_1) \big )}{4 \ln (R_1) \big ( N R_1 \hat {\mu }_1 (R_1^2-1) + 2 R_1^3 \big (\textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] \hat {\mu }_2 - \textrm {Re} [ I_{2,p}(q)] \hat {\mu }_1 \big ) \big ) - 4 R_1 \hat {\mu }_2 \textrm {Re} [I_{1}(q)] (R_1^2-1)}, \end{align}

implicitly depending on the local slip length from (3.17) and vice versa. Alternatively, it can be written as

depending on the coefficient

![]() $\beta$

, as defined in (3.15). The coupling of both fluid domains at the interface is now complete and both velocity fields are therefore fully described as a function of the other, using the coefficients

$\beta$

, as defined in (3.15). The coupling of both fluid domains at the interface is now complete and both velocity fields are therefore fully described as a function of the other, using the coefficients

![]() $\lambda _2$

and

$\lambda _2$

and

![]() $\hat {\tau }_1$

. Due to the greater complexity of the governing equations employed compared with case 1 in § 3.1, an explicit representation of both velocity fields is not provided.

$\hat {\tau }_1$

. Due to the greater complexity of the governing equations employed compared with case 1 in § 3.1, an explicit representation of both velocity fields is not provided.

4. Results and discussion

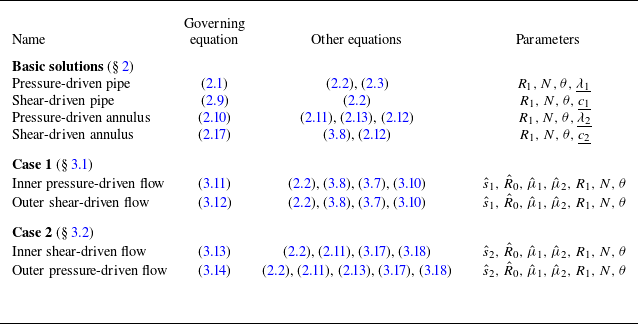

In what follows, the above equations are examined in more detail. Table 1 provides an overview of all results, with external parameters being underlined. For the sake of clarity, the governing equations are given with all the auxiliary formulae required for computation. Note that the equations derived so far can also be employed on their own, provided the necessary external parameters are known. Alternatively, they may be coupled, as just demonstrated, in which case the velocity field expressions are only a function of geometry and fluid properties.

4.1. Coupled multi-phase flow – flow fields

A selection of contour line plots of the axial velocity field for the inner and outer flows has already been presented in § 2. Both cases were initially considered separately, which is why exemplary local slip lengths

![]() $\lambda$

and imposed shear stresses were used. However, the equations derived in § 3, as already mentioned, no longer include these unknowns (see table 1) but rather describe the velocity field completely in terms of geometry and fluid parameters.

$\lambda$

and imposed shear stresses were used. However, the equations derived in § 3, as already mentioned, no longer include these unknowns (see table 1) but rather describe the velocity field completely in terms of geometry and fluid parameters.

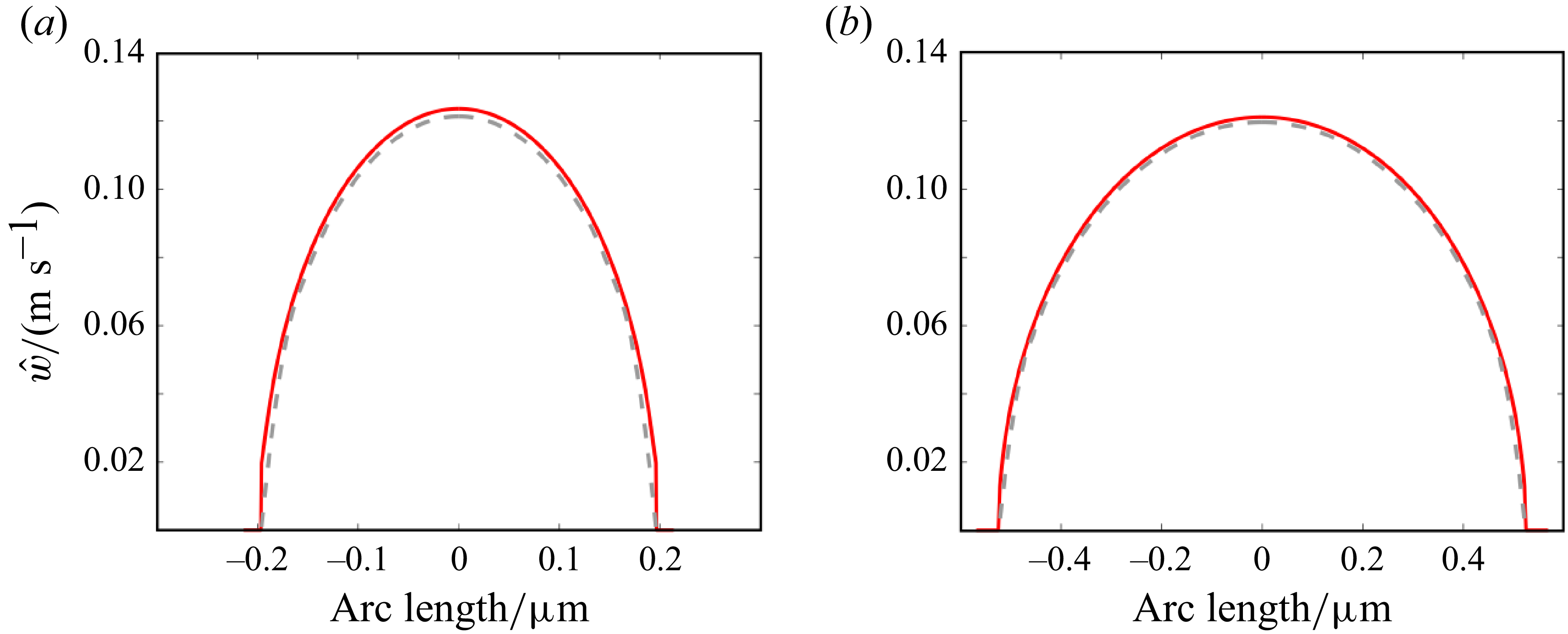

In the previous derivations, the coupling of both flow regimes, i.e. the pressure-driven and the lubricant flow, were achieved by prescribing equality of velocity and shear stress at

![]() $\zeta =q$

, i.e. a single point at the centre of the interfaces (see (3.1a

) and (b), respectively). This obviously corresponds to a mathematically convenient approximation, whereas this very equality must actually apply along the entire interface. However, it produces physically appropriate results. After all, a similar assumption is applied in the derivation of the pressure-driven flows, as already shown in previous work (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). To further demonstrate the validity of this modelling approach, the contour lines of the velocity field of the analytically derived equations (orange lines) are compared with full numerical simulations (grey dashed lines) in figure 5(a). We considered case 1, see § 3.1 for reference. The numerical simulations were carried out using the commercial finite-element solver COMSOL

$\zeta =q$

, i.e. a single point at the centre of the interfaces (see (3.1a

) and (b), respectively). This obviously corresponds to a mathematically convenient approximation, whereas this very equality must actually apply along the entire interface. However, it produces physically appropriate results. After all, a similar assumption is applied in the derivation of the pressure-driven flows, as already shown in previous work (Zimmermann & Schönecker Reference Zimmermann and Schönecker2024). To further demonstrate the validity of this modelling approach, the contour lines of the velocity field of the analytically derived equations (orange lines) are compared with full numerical simulations (grey dashed lines) in figure 5(a). We considered case 1, see § 3.1 for reference. The numerical simulations were carried out using the commercial finite-element solver COMSOL

![]() $\textrm {Multiphysics}^{\circledR }$

, where the two-dimensional Poisson equation was solved for the inner pressure-driven flow and the Laplace equation for the external lubricant. The corresponding viscous interaction is coupled along the entire interface (red slit segments) via the classic conditions of continuity of velocity and stress. Figure 5(a) clearly shows that the analytical and numerical results are in excellent agreement. Further comparisons with simulations, including considering case 2, also demonstrate excellent alignment with the analytically computed contour lines. An extended comparison between the numerical and analytical results can be found in Appendix C.

$\textrm {Multiphysics}^{\circledR }$

, where the two-dimensional Poisson equation was solved for the inner pressure-driven flow and the Laplace equation for the external lubricant. The corresponding viscous interaction is coupled along the entire interface (red slit segments) via the classic conditions of continuity of velocity and stress. Figure 5(a) clearly shows that the analytical and numerical results are in excellent agreement. Further comparisons with simulations, including considering case 2, also demonstrate excellent alignment with the analytically computed contour lines. An extended comparison between the numerical and analytical results can be found in Appendix C.

Figure 5. Illustrates the dimensional axial velocity contour lines for the coupled, fully determined models from § 3, always assuming a pressure gradient of

![]() $s=5000 \ \mathrm{Pa} \, \mathrm{m}^{-1}$

and an outer pipe radius of

$s=5000 \ \mathrm{Pa} \, \mathrm{m}^{-1}$

and an outer pipe radius of

![]() $R_0 = 1 \ \mathrm{mm}$

. With ‘case 1’ referring to an inner pressure-driven flow and an outer lubricant, and ‘case 2’ to the opposite, as defined in § 3. (a) Shows the comparison of the analytical solutions (orange lines) and fully coupled numerical simulations (grey dashed lines) for an inner pressure-driven water flow (

$R_0 = 1 \ \mathrm{mm}$

. With ‘case 1’ referring to an inner pressure-driven flow and an outer lubricant, and ‘case 2’ to the opposite, as defined in § 3. (a) Shows the comparison of the analytical solutions (orange lines) and fully coupled numerical simulations (grey dashed lines) for an inner pressure-driven water flow (

![]() $\hat {\mu }_1 = 0.001 \ \mathrm{Pa \ s}$

) and air as lubricant (

$\hat {\mu }_1 = 0.001 \ \mathrm{Pa \ s}$

) and air as lubricant (

![]() $\hat {\mu }_2 = 1.8 \times 10^{-5} \ \mathrm{Pa \ s}$

) with

$\hat {\mu }_2 = 1.8 \times 10^{-5} \ \mathrm{Pa \ s}$

) with

![]() $N=2, R_1 = 0.5, \theta =\pi / 4$

. (b) Inner water flow and air as a lubricant, with

$N=2, R_1 = 0.5, \theta =\pi / 4$

. (b) Inner water flow and air as a lubricant, with

![]() $N=4, R_1=0.3, \theta =\pi / 4$

. (c) Inner water flow and oil as a lubricant (

$N=4, R_1=0.3, \theta =\pi / 4$

. (c) Inner water flow and oil as a lubricant (

![]() $\hat {\mu }_2 = 0.005 \ \mathrm{Pa \ s}$

), with

$\hat {\mu }_2 = 0.005 \ \mathrm{Pa \ s}$

), with

![]() $N=5, R_1=0.5, \theta =0.9 \times \pi / 2$

. (d) Outer pressure-driven water flow and air as a lubricant, with

$N=5, R_1=0.5, \theta =0.9 \times \pi / 2$

. (d) Outer pressure-driven water flow and air as a lubricant, with

![]() $N=5, R_1=0.3, \theta =\pi / 3$

. (e) Pressure-driven water flow and oil as lubricant, with

$N=5, R_1=0.3, \theta =\pi / 3$

. (e) Pressure-driven water flow and oil as lubricant, with

![]() $N=3, R_1=0.7, \theta =\pi / 4$

.

$N=3, R_1=0.7, \theta =\pi / 4$

.

Figure 5(b–e) furthermore shows the fully described velocity fields for the coupled multi-phase flow, with pressure gradients of

![]() $5000 \ \mathrm{Pa\,m^{-1}}$

and an outer dimensional radius

$5000 \ \mathrm{Pa\,m^{-1}}$

and an outer dimensional radius

![]() $\hat {R}_0=1 \ \mathrm{mm}$

. Panels (b) and (c) illustrate the scenario of an inner pressure-driven water flow (

$\hat {R}_0=1 \ \mathrm{mm}$

. Panels (b) and (c) illustrate the scenario of an inner pressure-driven water flow (

![]() $\hat {\mu }_1 = 0.001 \ \mathrm{Pa} \ \mathrm{s}$

), with the former using air as lubricant (

$\hat {\mu }_1 = 0.001 \ \mathrm{Pa} \ \mathrm{s}$

), with the former using air as lubricant (

![]() $\hat {\mu }_2 = 1.8 \times 10^{-5} \ \mathrm{Pa} \ \mathrm{s}$

), exhibiting 4 slits (

$\hat {\mu }_2 = 1.8 \times 10^{-5} \ \mathrm{Pa} \ \mathrm{s}$

), exhibiting 4 slits (

![]() $\theta = \pi /4$

) and an inner radius of

$\theta = \pi /4$

) and an inner radius of

![]() $R_1 = 0.3$

. The latter, in contrast, has oil trapped in the outer tube (

$R_1 = 0.3$

. The latter, in contrast, has oil trapped in the outer tube (

![]() $\hat {\mu }_2 = 0.005 \ \mathrm{Pa} \ \mathrm{s}$

), with

$\hat {\mu }_2 = 0.005 \ \mathrm{Pa} \ \mathrm{s}$

), with

![]() $N=4$

, an inner radius of

$N=4$

, an inner radius of

![]() $500 \ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m}$

and a slit half-angle of

$500 \ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m}$

and a slit half-angle of

![]() $\theta = 0.9 \times \pi /2$

. In the same fashion, the last two contour line plots of figure 5 show an outer pressure-driven water flow, one with air (d) and the other with oil (e) as lubricant, as before. The air–water configuration exhibits

$\theta = 0.9 \times \pi /2$

. In the same fashion, the last two contour line plots of figure 5 show an outer pressure-driven water flow, one with air (d) and the other with oil (e) as lubricant, as before. The air–water configuration exhibits

![]() $5$

slits with an opening angle

$5$

slits with an opening angle

![]() $\theta = \pi /3$

(

$\theta = \pi /3$

(

![]() $R_1=0.3$

). For the water–oil scenario in panel (e), we set

$R_1=0.3$

). For the water–oil scenario in panel (e), we set

![]() $N=3, R_1=0.7$

and

$N=3, R_1=0.7$

and

![]() $\theta = \pi /4$

.

$\theta = \pi /4$

.

An initial qualitative analysis of the contour line plots presented clearly shows the importance of the viscosity ratio

![]() $k=\hat {\mu }_1 / \hat {\mu }_2$