Social enterprises (SEs) have emerged across the globe to create social value through market-based activities and innovation (Dart, Reference Dart2004). For instance, work integration SEs hire chronically unemployed and/or marginalized people, such as formerly incarcerated people, to create marketable goods or services (Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013). Scholars typically conceptualize SEs as hybrid organizations that integrate multiple institutional logics (Battilana & Lee, Reference Battilana and Lee2014), defined as cultural symbols, material practices, and belief systems that shape taken-for-granted assumptions, values, and practices (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). As SEs struggle to balance social-business orientations, research has focused on the institutional complexityFootnote 1 (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011) created by social-welfare and market logicsFootnote 2 (see Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gonin and Besharov2013).

However, growing research suggests other institutional logics influence SEs (Kerlin et al., Reference Kerlin, Peng and Cui2021; Neuberger et al., Reference Neuberger, Kroezen and Tracey2023; Zhao & Wry, Reference Zhao and Wry2016). Indeed, SEs have proliferated in authoritarian regimes, where the state plays a critical role mediating between the economy and civil society. Marquis and Bird (Reference Marquis and Bird2018) find that coercive government pressures and restrictive policies may present formidable barriers for effective market and nonmarket activities, while others find that because institutional infrastructure is typically weak and unmet social needs are usually considerable, the state may seek to foster SE development (Hua, Reference Hua2021; Kerlin, Reference Kerlin2010). The complex state–society–market dynamics in authoritarian states may generate a unique form of institutional complexity for SEs.

Drawing on interview data from 42 SE leaders and two field experts, we examined how SEs perceive and manage institutional complexity in China in their social innovation efforts. This study contributes to SE research by showing how sociopolitical forces shape the institutional complexity Chinese SEs confront: The key tensions arise from the state–social logics, and the dominant state logic shifts the social–market relationship to be compatible. This study not only answers scholarly calls to explain the role of the state in SE organizing (e.g., Defourny & Kim, Reference Defourny and Kim2011; Kerlin et al., Reference Kerlin, Peng and Cui2021; Maher & Hazenberg, Reference Maher and Hazenberg2021), but also “addresses the democratic society bias” in SE and institutional research (Neuberger et al., Reference Neuberger, Kroezen and Tracey2023, p. 93).

Relatedly, this research sheds light on the interrelationship among disparate logics in hybrid organizing (e.g., Yan et al., Reference Yan, Almandoz and Ferraro2021) and enriches growing research suggesting institutional logics may be complementary (e.g., Beaton, Reference Beaton2021; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Lu and Lee2022). Thus, this research answers calls to “understan[d] contextually situated analysis of institutional logics” to illuminate the influence of multiple logics on SE practices, thus improving practitioners’ capacity to manage SEs (McMullin & Skelcher, Reference McMullin and Skelcher2018, p. 911).

This study also extends research in organizational responses to institutional complexity, showing two strategies Chinese SEs employ: depoliticization and localization. This research contributes to a contextual understanding of social innovation organizing in a non-Western context (Stott & Tracey, Reference Stott and Tracey2018), highlighting the institutional nature of social innovation (van Wijk et al., Reference van Wijk, Zietsma, Dorado, de Bakker and Martí2019). In contrast to widely held assumptions about scaling up social innovations to achieve larger impact (e.g., Bi & Yu, Reference Bi and Yu2023; Westley et al., Reference Westley, Antadze, Riddell, Robinson and Geobey2014), this study suggests SEs tend to keep social innovation local and small in a politically restrictive context.

Literature Review

SEs and Social Innovation: An Institutional Logic Perspective

The need for organizations to create or adopt social innovations to tackle societal challenges is urgent (van Wijk et al., Reference van Wijk, Zietsma, Dorado, de Bakker and Martí2019). Scholars consider SEs as one of the most effective organizational vehicles of social innovation, positing that innovation is core to SE organizing (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gonin and Besharov2013). For instance, Dart (Reference Dart2004) suggests SEs “engag[e] in…continuous innovation, adaption, and learning” (p. 414). SEs address persistent social issues in developed and developing countries through developing new business models, work experiences, and training programs (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019; Zhao & Wry, Reference Zhao and Wry2016).

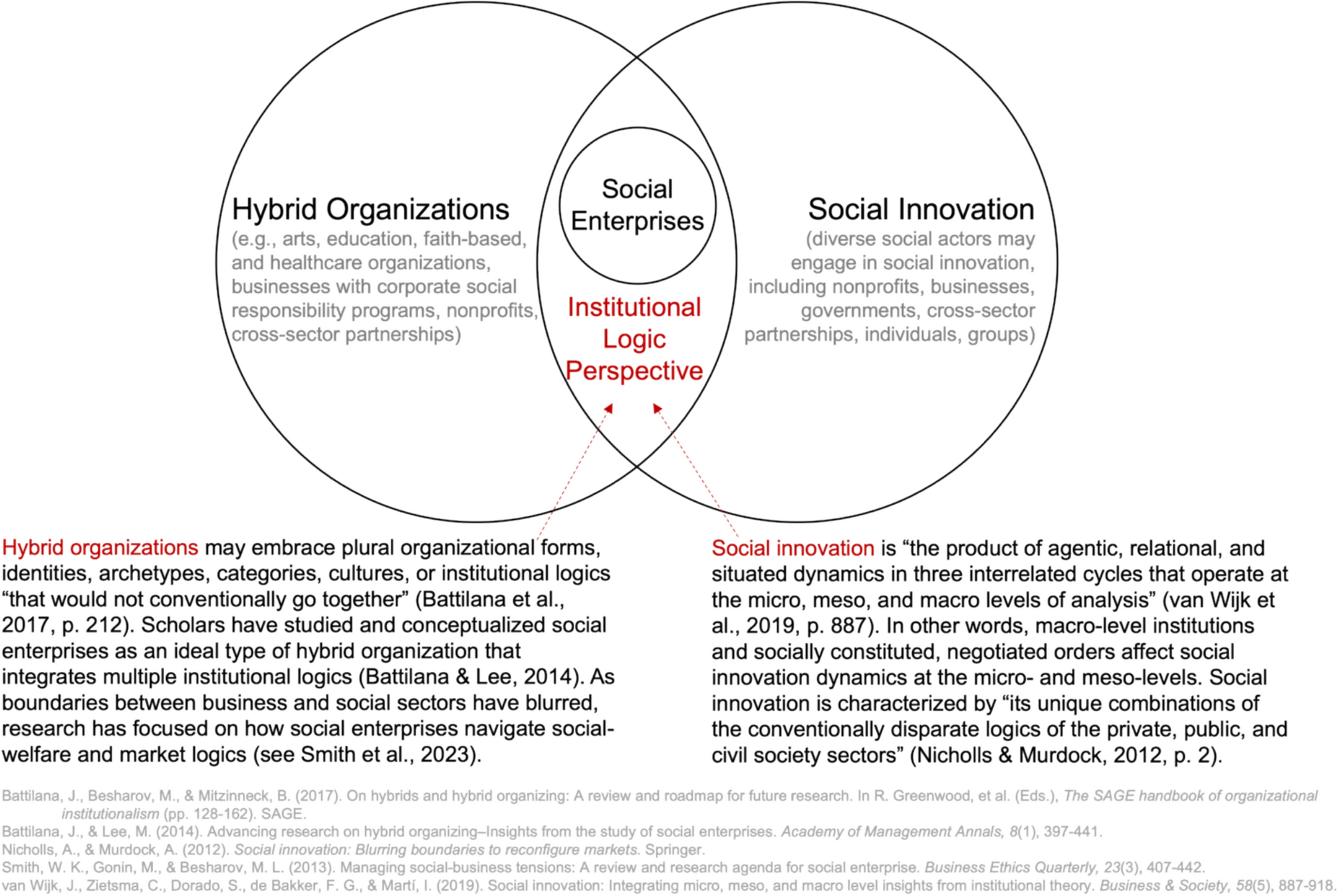

Research on both SEs and social innovation calls for the institutional logics perspective (see Fig. 1). This perspective is explicit about theorizing the interrelationship of different institutional orders and societal structures in shaping organizational action (Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019). Given the wicked nature of grand challenges, social innovations often have to go beyond conventional societal jurisdictions and creatively combine elements from alternative fields. Scholars argue social innovation organizing at the micro- and meso-levels involves re-negotiations of multiple institutional logics and socially constituted orders among diverse actors (van Wijk et al., Reference van Wijk, Zietsma, Dorado, de Bakker and Martí2019).

Fig. 1 Key concepts

Likewise, much SE research has adopted the institutional logics perspective to understand how SEs cope with institutional complexity (e.g., McMullin & Skelcher, Reference McMullin and Skelcher2018; Wry & Zhao, Reference Wry and Zhao2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cai and Song2023), the situation when multiple societal logics make sometimes incompatible prescriptions for organizational action (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). Extant studies primarily focus on social-welfare and market logics and the divergent management principles, goals, practices, and governance mechanisms they prescribe (see Battilana & Lee, Reference Battilana and Lee2014). Market logic prescribes profit maximization, competitive advantage, and efficiency. Social-welfare logic prioritizes social value creation, community well-being, democratic control, and social change. Scholarly interest in the social–market contention originates from the notion of “market fundamentalism” for economic action in Western neoliberal democracy contexts (Mars & Lounsbury, Reference Mars and Lounsbury2009, p. 11).

However, authoritarian states may violate assumptions about market fundamentalism. These states are “characterized by a strong concentration of political power in the hands of [few] elites,” intolerance of dissent, governance with limited transparency, constraints on individual freedom, “a strong preference for social order over the social ‘chaos’ that they associate with democratic systems,” and “public censorship and information and media control” (Neuberger et al., Reference Neuberger, Kroezen and Tracey2023, p. 69–70). The government’s basic orientation toward “securing social and political order” (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Díaz, Li and Lorente2010, p. 523) plays a central role in organizational functioning, and organizational actors face arbitrary government regulation; hostility toward entrepreneurial, grassroots activities; and a restrictive, repressive political and policy environment. Normal institutions necessary for the development of SEs in neoliberal contexts (e.g., favorable tax laws, free market entry) may be absent in authoritarian regimes (Kerlin, Reference Kerlin2010; Neuberger et al., Reference Neuberger, Kroezen and Tracey2023), leading to a distinct landscape of institutional complexity.

Given that core assumptions about organizational survival and legitimation in existing studies do not apply to authoritarian settings, the strategies SEs employ may differ (Neuberger et al., Reference Neuberger, Kroezen and Tracey2023). Prior studies have set the empirical stage in authoritarian contexts, but research has yet to systematically examine the role of the state logic and the challenge it may pose to how SEs perceive and manage institutional complexity, particularly in their core activities of social innovation. We address this gap and contribute to a deeper understanding of institutional complexity confronting SEs in China.

SEs and Social Innovation in China

SEs have boomed in China since around 2004, responding to the challenges confronting the nongovernmental organization (NGO) sector, such as the state’s introduction of stringent NGO registration and annual review policies, as well as a small philanthropic donation market (Yu, Reference Yu2011). Several venture philanthropy funds and foundations (e.g., the Nonprofit Incubator, Ginkgo Foundation) have supported SEs (Zhao, Reference Zhao, Chandra and Wong2016). According to the 2019 China SE and Social Investment report, at least 1,684 organizations identify as SEs and are recognized by their peer organizations. They exist in 46 cities in 27 provinces and municipalities nationwide, with first-tier cities such as Shenzhen, Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai having the largest number.

As with the general SE scholarship (see Battilana & Lee, Reference Battilana and Lee2014), the definition and operationalization of an SE remains contested in China (see Appendix A), but scholars on Chinese SEs generally agree that SEs employ market means to accomplish a social mission. Emerging research reveals the diverse SE landscape in China. For example, Chinese SEs may depend on income from goods or services, donations, or government funding (e.g., Arantes, Reference Arantes2022; Bhatt et al., Reference Bhatt, Qureshi and Riaz2019; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cai and Song2023; Ye, Reference Ye2021). Chinese SEs focus on many issue areas; the most popular include employment promotion, elderly services, community development, education, environment, and poverty alleviation (Bhatt et al., Reference Bhatt, Qureshi and Riaz2019; Yu, Reference Yu2011; Zhao, Reference Zhao, Chandra and Wong2016). Research has documented a variety of social innovations from Chinese SEs, such as the development of intelligent robots for protective services (see Huang & Han, 2019). Some Chinese SEs embrace physical and mental health interventions involving emerging digital technologies (Yin & Chen, Reference Yin and Chen2018).

However, the dominance of the state over NGO governance and limited public trust have remained formidable challenges (Spires, Reference Spires2020). Unlike many developed countries, China lacks a legal designation for SEs and thus favorable tax statuses that support SEs (Ye, Reference Ye2021; Yu, Reference Yu2011). By contrast, in Western neoliberal democracies, the tax code and the non-distributional limits on earned income have created clear distinctions between nonprofits and for-profits (Frumkin, Reference Frumkin2009), and hence the differentiation of the social-welfare and market logics. In the absence of such legal distinctions, China’s SE field may differ markedly from those studied in prior studies. Faced with the restrictive dual administration system and the limited scope of activities for registering as nonprofits (e.g., private non-enterprise unit), many SEs remained unregistered or register as regular for-profit companies, even if they do not expect profits, and even though it may undermine public trust in their social mission (see Appendix A). Chinese SE leaders lament such limitations in addition to political risks and interference from the state (Bhatt et al., Reference Bhatt, Qureshi and Riaz2019). Because of SEs’ primary goals of social mission, Chinese SE research has focused on the social–market or social–state relationships (e.g., Kerlin et al., Reference Kerlin, Peng and Cui2021; Yin & Chen, Reference Yin and Chen2018), as opposed to the state–market relationship.Footnote 3

Moreover, different local governments treat SEs differently (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2004; Spires, Reference Spires2011). Although a few senior government officials have publicly applauded social innovations SEs developed to address unmet social needs, the central state has no official stance on SEs’ existence or practices (Zhao, Reference Zhao2012). In this context, in politically restrictive geographic areas (e.g., Beijing, Inner Mongolia), the local government is mistrustful of SEs which it seems as infringing on the state’s primary responsibility for social problem-solving (Bhatt et al., Reference Bhatt, Qureshi and Riaz2019). Other municipal governments (e.g., Chengdu, Shanghai, and Shenzhen) have supported SEs, playing the roles such as funders, incubators, and policy guides (Arantes, Reference Arantes2022; Hua, Reference Hua2021; Ye, Reference Ye2021). In sum, the legitimacy and successes of SEs may be “determined by their interactions with the local state” (Hsu & Hasmath, Reference Hsu and Hasmath2014, p. 516).

Responsive authoritarianism allows some space for public participation to improve governance over social issues and the state and civil society have become closer and more complementary. But the threat and reality of control of civil society organizations remains ubiquitous in China (Hildebrandt, Reference Hildebrandt2011; Hsu & Hasmath, Reference Hsu and Hasmath2014; Marquis & Bird, Reference Marquis and Bird2018; Pan & Xu, Reference Pan and Xu2022; Spires, Reference Spires2011, Reference Spires2020). Chinese SEs experience state hostility, repression, and suspicion at both the central and local levels (e.g., Bhatt et al., Reference Bhatt, Qureshi and Riaz2019; Zhao, Reference Zhao2012) that limits their autonomy and participative governance (Yu, Reference Yu2013).

Prior studies’ focus on the social–market tensions has led to a peripheral approach to the study of the institutional logics beyond social-welfare or market in SEs. This may have obscured state–society dynamics in authoritarian regimes and how the state logic influences SEs’ hybrid operations. Thus, we first ask:

RQ1:How do organizational leaders perceive the interrelationship among the most prominent institutional logics Chinese SEs embody?

Organizational Responses to Institutional Complexity

Organizations must adapt their strategy to align with the institutional environment to maintain legitimacy, particularly in politically restrictive contexts (Kerlin et al., Reference Kerlin, Peng and Cui2021; Neuberger et al., Reference Neuberger, Kroezen and Tracey2023). Research on institutional logics suggests organizational responses to the institutional environment depend on how institutional complexity instantiates in organizations (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). For instance, an organization may integrate multiple logics into a common identity (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010), resist or eliminate a logic (Mair et al., Reference Mair, Mayer and Lutz2015), or selectively incorporate logics to symbolically attend to their disparate demands (Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013).

Because the dominant state logic creates a unique form of institutional complexity, Chinese SEs likely deploy distinct strategies to manage institutional complexity in their social innovation efforts. The adaptation to the institutional context is particularly important for SEs, where key audiences may be suspicious of this new organizational form from the outset, the facilitating institutional infrastructure is largely deficient, and politics are restrictive and even detrimental for SEs. Since social innovation is core to SEs, studying SEs naturally entails investigating social innovation (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gonin and Besharov2013). Therefore, we explore how SEs uniquely respond to institutional complexity in their social innovation efforts by asking:

RQ2:How do Chinese SEs cope with institutional complexity in their social innovation?

Methods

Because of the limited research in institutional complexity in Chinese SEs, we employed a qualitative, inductive methodology via a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998), which allowed us to look for themes and relationships across the data, uncover hidden concepts and emerging issues in Chinese SEs, and suggest a theory for institutional complexity and social innovation by Chinese SEs.

Interview Data Collection and Procedure

To develop the profiles of SEs, we relied our primary data source on semi-structured interviews with the founders or leaders of 42 SEs in 2016. We followed the SE definition (i.e., a nonprofit or for-profit organization that uses market mechanisms to address social problems) to guide us in theoretical sampling. Through a snowball sampling strategy, we recruited participants through direct inquiries and referrals until we reached theoretical saturation. Sources included personal contacts, referrals from China’s SE Research Center, and participants’ referrals. This is consistent with the self-identification and peer-approval approach used in China’s SE field (e.g., Bi & Yu, Reference Bi and Yu2023).

Depending on informants’ preference and location, we conducted face-to-face or remote interviews by telephone, WeChat, or Skype. Each lasted 45–110 min (M = 54.32). Each interview was transcribed verbatim. The research team verified the accuracy of each transcript against the audio recordings and then sent them to each interviewee for review. The transcripts amounted to 587 pages (single-spaced) of transcripts. Appendix B provides the guiding interview protocol approved by the first author’s institution. Appendix C provides the key information of the studied SEs. On average, the SEs had existed for 5.36 years (SD = 4.89). Informants came from 11 municipalities and provinces, although Beijing and Shanghai predominated (n = 26, 62%). The SEs were also diverse in terms of the founders’ professional backgrounds, social mission, business models, and sources of revenue.

Many SEs developed their business models and/or social innovations through learning from SEs overseas. For example, nutrition education programs in Japan inspired SE05; Design for America inspired SE32’s human-centered design summer camps; SE41 aimed to become China’s Charity Navigator and GuideStar equivalent; SE08’s mobile app was inspired by the United States’ Amber Alert; the US Recycle Bank model inspired SE22’s garbage recycling programs; and SE21 emulated the European model of 404 website for public service advertising.

Two interviews with field experts, from a Shenzhen-based SE research institute and a Beijing-based social impact investment organization, provided additional data. These took place via WeChat (40-min each, 19-page transcripts).

Data Analysis

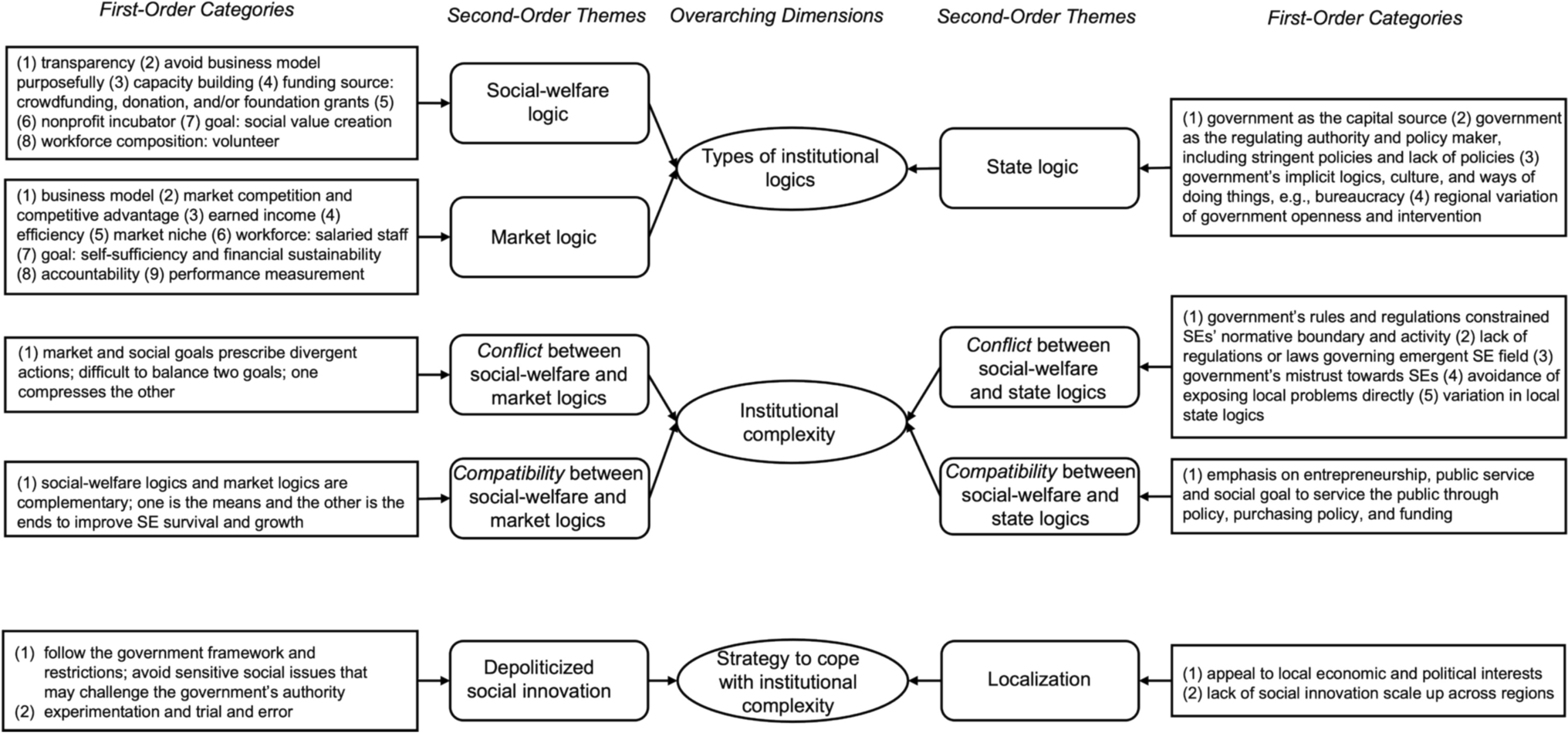

We used Atlas.ti to keep track of all open, axial, and selective codes, and employed a two-phase coding procedure to identify emerging themes (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Data structure

In the first phase, we identified the most prevalent institutional logics in Chinese SEs and mapped their interrelationship. First, we read all interviews to familiarize ourselves with the dataset. Next, we conducted open coding to develop initial categories and themes from the interview data. We used sentences or paragraphs as coding units and labeled them with in vivo codes or descriptive sentences. To do this, we read the interview transcripts and identified all references to institutional logics (e.g., in funding source, organizational goals). Examples of the social-welfare logic included funding source (e.g., “public donations,” “foundation grants”) and workforce composition (e.g., “volunteers and unpaid workers”). Codes that reflected the market logic included capital source (e.g., “business models and earned income”) and management principles (e.g., “formalization, efficiency, and professionalism”). Codes about the state logic included capital source (e.g., “funding from government contracting, procurement, grants”) and organizational goals (e.g., “conformity to state regulations” and “build political legitimacy”). State logic was more prevalent than social-welfare or market logic. Government rules, policies, regulations, norms, and funding shaped SE operations.

We conducted a second round of open coding to identify additional concepts or themes to improve the reliability of the findings. We then created a codebook based on themes identified and conducted axial and focused coding. We also established higher order axial codes and managed the interrelationships between the open codes. This involved reassembling the coded data by grouping conceptually similar codes as facets of the same institutional logic. We further reclassified the axial codes into compatibility (e.g., informants discussed logics as harmony or synergistic; 相辅相成,一脉相承) and conflict (e.g., informants discussed logics as contradictory or conflicting; 矛盾,冲突). In doing so, we gained insight into a unique form of institutional complexity Chinese SEs confront.

In the last stage, we verified the data and our interpretations based on quotes from the field experts. In case of inconsistency, we recursively returned to the interview data to triangulate different data sources and look for instances to validate or reject our claims.

Based on the central themes identified in the first phase, the goal of the second phase was to identify how SEs cope with such institutional complexity in their social innovation efforts. First, we conducted open coding to develop initial categories and themes (i.e., first-order concepts) when the informants talked about innovations, responses, and strategies, focusing on how SEs organize and manage their social innovation processes based on the institutional complexity manifested in their organization. During this process, we noticed the concerns informants shared about scaling up their SEs and/or social innovations geographically, such as concerns about limited human, financial, and political resources and concerns about loss of identity and mission drift. We then created a codebook and conducted axial and focused coding in the second stage. Based on the analytical notes, we established higher order axial codes that subsumed the open codes and managed the interrelationships among them. Focused coding resulted in a reclassification into three main codes indicating the focus of strategies through which the informants managed institutional complexity during their social innovation efforts.

Results

Dominance of the State Logic and Social–State Conflict

As logics are interdependent yet contradictory, we address both conflicts and compatibilities between logics (see Appendix E). Given that the conflict between state and social-welfare logics was the most prominent, we focus here on reporting the conflict between social-welfare and state logics.Footnote 4 Based on the findings, we also develop key propositions.

The state, as a regulatory authority, constrained SEs’ functioning, effectiveness, and efficiency to provide social services. Various restrictive laws, regulations, and policies, at the central and local state levels, limited SEs’ ability to appeal to their stakeholders to mobilize social and economic capital. Leaders therefore perceived profound conflict between social-welfare and state logics.

Informants complained about the complex approval and review procedures for organizing public events and operating under official supervision. They noted the limitations of the categories nonprofit private non-enterprise entity (minying feiqiye) and for-profit company, and the need to obtain the support of a supervisory unit (i.e., a government agency or government-affiliated organization), high registration fees, and limited geographic scope of authorized services for the former. A transnational social entrepreneur (SE33) working on children’s education in rural areas obtained US registration because “It is almost impossible to register as an NGO in China…. You need solid government resources [connections] to gain approval.” Even if SEs are able to navigate the “lengthy process” of registering as “a government-sponsored organization,” they “will have limited autonomy” and “it will be difficult to survive” under the government’s “hostile policies” (SE32). According to the leader of SE12,

[T]he government controls and manages the whole SE sector, including funding, laws, and polices. … It’s complicated…Without tight government intervention or control, it would be more open, and the development of the SE field would be much faster…the bigger field and sector is not healthy, because of these constraints…social organizations are being fed [literally, breastfed; buyu in Chinese, thus, relying wholly on the government for sustenance].

Similarly, the leader of SE15 reflected, “The pattern of state-society relations has been ‘strong-government weak-society’ for many years in China. The government should not intervene in many things, nor do they have the ability.”

Some SEs remained unregistered, which caused stakeholders to question their legitimacy. It also increased obstacles when negotiating collaboration opportunities with potential partners, who were cautious about SEs’ “illegal” status. Similarly, registering as a business weakened the credibility of SEs with potential clients and aroused public suspicions about the benevolence of their enterprise. As the leader of SE20 explained:

When you sign big contracts with other organizations, you must have a licence. We had no choice but to register as a for-profit company. But the licence of a social organization and a for-profit company are completely different. . . . When you operate with a company licence, people will ask, aren’t you a not-for-profit? Why are you using a company licence? Even now [that we have reputation in the field], there are many challenges.

In sum, our findings suggested the strict state policies on the legal status of SEs negatively affected key stakeholders’ trust.

Participants also cited the lack of formal regulation as a manifestation of the deeply contested social–state tensions. For instance, in line with the literature and our two expert informants, the leader of SE30 stated China has “no legislation, customized preferential policies, or support measures for SEs.” The lack of tax benefits and “well-established regulations, policies, and laws” for SEs amplified social–state tensions because the government is expected to provide institutional guarantee and support for SEs to flourish and thrive, “protecting SEs and activating their full potential for social problem-solving” (SE17).

In addition to the bureaucracy problem commonly cited in the literature, our data revealed local governments generally directed distrust, suspicion, and “denial” (SE20) toward SEs because of concerns about public order and security. As the leader of SE40 stated, “the SE sector is still in its infancy,” and the government’s understanding and attitude toward SEs are still limited and biased, which “pose significant challenges for their activities and operations.” These obstacles have impeded SEs’ operations and social innovation organizing, leading to social–state tensions.

Some informants mentioned local government officials did not trust social entrepreneurs, and some were totally opposed to them, although leaders with government work experience or an “administrative record” (beishu in Chinese) could get better treatment. Some felt they did not obtain the resources or recognition they deserved despite having the required eligibility and qualifications as a result. According to the leader of SE23, SEs cannot leverage political resources and government support without “political ties” or “before your organization has any performance [social impact].” Similarly, the leader of SE37 remarked said the government only supports SEs after they have “some level of social impact or obtained some achievement,” unless their leaders have “political connections.”

However, SEs supported by local governments had to play by their rules and submit to tight control by state actors that affected their day-to-day operations, sometimes causing delays in the timely delivery of services. The founder of SE14 discussed the subtlety of responding to local political interests, communicating social problems to the government privately, and appeasing government officials as opposed to openly criticizing the government for any failure:

The ideology for food safety in China is different from that in other countries.… Previously, we monitored many cases, cracked down on many crimes, and reported many cases to the government. But the problem is that the government leaves you very little room [for civil society action].… If you have solid evidence, you can communicate [and collaborate] with the government privately and ask its law enforcement to solve the problem. You cannot find illegal cases and expose them directly in the media. [If you do], you are dead, totally, totally.

They ultimately learned that it was necessary to report food safety violations privately to local state departments.

Local government officials may prefer SEs not expose social problems in their jurisdiction because negative news coverage can attract unfavorable attention from their superiors in the government and thereby lessen their chances for promotion. SEs had work behind the scenes with local government officials to address social problems, such as left-behind children and migrant worker issues (SE33), child abduction and trafficking (SE08), climate migrants (SE28), and damage to historic villages (SE18).

In summary, the social-welfare and state logics emphasize different priorities, values, and goals, exhibiting the most significant source of conflict for Chinese SEs. SEs are most effective when they can openly expose social problems to enhance public awareness, but state logics forbade such exposure. Based on these findings, we developed the following proposition:

P1. The social-state conflict predominates in Chinese SEs.

State Logic (Re)Configures the Social–Market Relationship

Corroborating the existing SE studies, some SE leaders referenced the social–market conflict in constraining their operations (see Appendix E). However, this was rare. SEs are primarily driven by social mission; making money is a means to an end rather than, as in business, the primary end. The most common language informants used to describe the social–market relationship was “mutually reinforcing” and “complementary.” That is, Chinese SE leaders saw social-welfare and market logics as highly compatible and synergistic. For instance, the leader of SE22 suggested that to accomplish their ultimate social goal, they must survive first; their central social mission guide their business models “in an ethical, united, and sustainable manner.” SE leaders concurred:

I don’t think social value can be separated from business value.… They are complementary to each other. Although our primary goal is social value. . . profit is an essential part of our enterprise. If social value is our dream, economic value is our daily supplies. [SE03]

They do not conflict with each other. The former is an ultimate goal, but you have to use various [business] means to achieve this goal. [SE13]

Only when you are self-sufficient can you create social value; only when you have large social impact can you generate sustained income in turn. They are complementary and mutually reinforcing. [SE37]

The state logic actually attenuates the social–market conflict, in three ways. First, the state logic, rooted in the communist and socialist nature of China’s institutional system, imprinted on SE leaders and made them idealists. State propaganda on common prosperity and people-centered economic development cultivates a mindset that commercial activities should serve a social mission. As the leader of SE34 explained, “SE is a form of organization that aligns well with the socialist nature of China, with the goal of serving social needs. It is consistent with the spirit of socialism ideology and socialist spirit.” The director of SE01 suggested social-welfare enterprises the state set up to provide employment opportunities for people with disabilities about five decades ago contributes to the perceived social–market compatibility. Likewise, the leader of SE31 referenced several long-existing, well-known welfare enterprises (e.g., Dabao cosmetics) to highlight the fit of SEs in China’s socialist system. Some SE leaders perceived this compatibility as an attribute and the “norm” and “core” of all organizations. They suggested that in China’s policy environment “all enterprises have their social nature and dual goals.”

Second, the dominance of the state logic also increased the perceived social–market compatibility because the state funds and supports SEs as useful extensions providing necessary public services. State funding and provision of resources are particularly important to alleviate the social–market tensions for early-stage SEs, who are still exploring and improving their own business model. For example, two-thirds of SE22’s start-up funding came from government procurement. The local government has limited capacity to provide recycling services and thus has such services to this SE. SE28 reported an even higher percentage, 90%, in its early days, as well as incubation support that helped it “survive…and come to the next stage of larger visibility and social impact.” Since it has begun offering paid tours for the elderly populations, SE28 receives about 50% of its funding from the government. Neither SEs’ leaders were seeking independence from government funding. As one of our experts stated, the government views SEs as “tool[s] for maintaining social stability” through social service provision and hence provides such funding.

Third, the tepid philanthropic contribution market in China, which reflects the dominant state logic, also attenuated the perceived social–market conflict, because state–social conflict is so dominant that social–market conflict becomes negligible. As the leader of SE03 explained, China does not have “established donation systems from corporations, rich people, and individuals to support public welfare projects and ensure the sustainability of NGOs” as Western countries often do. SEs tend to rely less on public donations than government funding due to China’s restrictive policies and regulations. Like SE11, many SEs that registered as a nonprofit had “no fundraising qualification” under the law. The state restricts NGOs’ fundraising activities in a number of ways, including failing to give tax incentives for individual or organizational donations. The small philanthropic contribution market and a lack of stable donations mean that most SEs have no philanthropic alternative. As such, SE leaders saw no tension between donations and profits.

In summary, our data revealed Chinese SEs experience less social–market conflict than their peers in other countries, while the conflict between state and social-welfare logics is dominant. The state’s intervention in market and nonmarket activities induces some degree of social–market compatibility in three ways. Hence, we propose:

P2. The state logic attenuates the social-market conflict Chinese SEs confront.

Navigating Institutional Complexity in Social Innovation Efforts

We further probed how Chinese SEs coped with such institutional complexity in their social innovation efforts.

Depoliticization

Although SEs and the state converge partially in their desire to provide public services, organizations must keep their operations small and depoliticized to survive. Social innovation ideas that are sensitive or employ radical activism for public awareness could undermine state legitimacy and power and thus never get traction. Chinese SEs cannot experiment with seemingly radical social innovation ideas, because “all possible paths have been blocked by the government” (SE24). Schwartz’s (Reference Schwartz2004) argument still holds for the Chinese civil society landscape inclusive of SEs today: China has “a rather weak and passive civil society,” “a depoliticized sphere of social and economic life with political power remaining in the hands of the state” (p. 35). The Chinese state has merely moved away from “overt sanctioning” to “tacit sanctioning,” developing strong ties with civil society organizations “to enable the state to organize societal interests” consistent with its agenda (Hsu & Hasmath, Reference Hsu and Hasmath2014, p. 521).

To survive, SEs target their social innovation efforts within the government’s agenda. The leader of SE05 highlighted the need to comply with state requirements in social innovation creation, citing the explicit monitoring of these innovations by the state. Otherwise, “the [local] state will not approve and will cut your project off.” The leader of SE30 explained “If you can forge good relationships with the local government and get government contracts, [your organization] will have a higher probability of surviving.”

In the midst of a lack of formal institutions and stable politics and a fuzzy and frequently shifting political line, Chinese SEs vigorously self-censored to ensure they did not release information that could incite state repression. Such self-censorship involves experimentation and trial and error. After several incidents and shutdowns of their social media accounts, SE24 learned to not publish articles that explicitly attacked or implicitly criticized the system, for example, by referencing stories from a similar authoritarian context. Likewise, SE14 learned not to report safety violations to the media over time.

P3. Chinese SEs employ a depoliticized social innovation approach to prioritize the state logic.

Localization

Some local governments are more open and supportive of SEs than others. Our informants indicated the governments of Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou are more supportive of SEs than other jurisdictions, more likely to see them as an opportunity to improve public services. Informants pointed out that Beijing, China’s political center with a rich history of activism and social movement, was relatively conservative, manifested in stringent registration and review policies (SE10), as well as distrust toward grassroots organizing. The founder of SE40 described “an impasse” in state–society dynamics in Beijing.

Such variations “present formidable challenges to scale up an SE” (SE05) and thus generally prevent expansion. As the founder of SE20 noted, “even if you could scale up the program, you cannot bring many things over... including local culture and policy environment.” Even local governments with similar approaches to that of the SE’s headquarters would need to be cultivated. The leader of SE31 said: “What hinders us [from scaling up] is not financial or human resources, but our local political resources…We need [political] connections.”

The founder of SE27 summarized “The government and social organizations have two different systems. So you cannot push this [scaling up], even if you wish. You need an opportunity that has the right time, in the right place, and with the right people.”

P4. Chinese SEs limit their social innovation in response to local politics.

Discussion

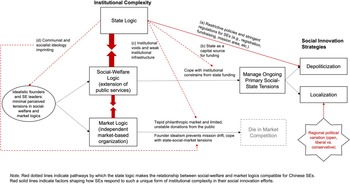

This research investigated how SEs perceive and cope with institutional complexity in a politically restrictive context. We found Chinese SEs struggle the most with tensions between state and social-welfare logics. The state logic also renders the social–market relationships relatively compatible. Accordingly, we found Chinese SEs develop social innovation in accordance with this unique form of institutional complexity through depoliticization and localization. Figure 3 presents a holistic framework of our findings.

Fig. 3 Summary of findings

This study makes three theoretical contributions. First, in contrast to prior SE studies, which focus on social-welfare and market logics (see Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gonin and Besharov2013), this research suggests the core of the state logic to SE functioning in authoritarian states. Our finding that Chinese SEs are struggling the most in the state–society conflict echoes the Chinese NGO scholarship (Hildebrandt, Reference Hildebrandt2011; Marquis & Bird, Reference Marquis and Bird2018; Spires, Reference Spires2020). Similarly, emerging SE research in other authoritarian contexts (e.g., Egypt, Jordan, Vietnam) has documented the central state–society conflict over the social–market tension (Maher & Hazenberg, Reference Maher and Hazenberg2021; Tauber, Reference Tauber2021). Specifically, SEs must avoid negative attention and ensure that state actors understand their activities well and do not perceive them as threatening or offensive, as opposed to standing out to attract attention (Neuberger et al., Reference Neuberger, Kroezen and Tracey2023). Therefore, in authoritarian and hybrid “contexts that are strictly regulated, closed, and where stability is generally prioritized over change,” SEs “have a primary strategic orientation toward being as unobtrusive as strategically possible” (p. 94–95). The accumulating evidence from authoritarian states suggests scholars must actively rethink the explicit and implicit assumptions to advance theory and empirical SE research.

Second, this research suggests the predominant state logic (re)configures the relationships among other institutional logics by making the social–market relationship compatible. As our findings reveal, the socialist and communist roots that emphasize common prosperity and social harmony, along with the state’s ubiquitous intervention in market and nonmarket activities (e.g., state reforms to create social-welfare enterprises), render Chinese SE leaders convinced that social-welfare and market logics are compatible. Hence, this study enriches recent hybrid organizing research on how an institutional logic may shift the challenges in other institutional logics (Wry & Zhao, Reference Wry and Zhao2018; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Almandoz and Ferraro2021). This adds to the budding research that suggests SE practitioners may perceive social–market logics as compatible and synergistic (Beaton, Reference Beaton2021; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Lu and Lee2022).

Third, the critical role of the state logic in authoritarian regimes, where social issues tend to be greater than in other contexts, underscores the necessity of developing unique strategies to manage institutional complexity to tap the full social innovation potential of SEs. Specifically, our research identifies depoliticization (prioritization of the state logic) and localization (integrating and balancing the social-welfare and state logics) Chinese SEs employ to manage the primary social–state tensions. This extends research in organizational responses to institutional complexity among SEs (Mair et al., Reference Mair, Mayer and Lutz2015; Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019).

In contrast to most research, which assumes entrepreneurial actors aspire to scale up social innovations for larger social impact (e.g., Bi & Yu, Reference Bi and Yu2023; Westley et al., Reference Westley, Antadze, Riddell, Robinson and Geobey2014), this research suggests scaling up may not be feasible or desirable in authoritarian contexts where organizations must adapt to local politics. Underlying the corporatist institutional framework with the distinct tacit sanctioning approach of the local state, “select organizations and groups are granted the privilege to mediate interests on behalf of their constituents to the state; and these organizations and groups must adhere to the rules and regulations established by the state” (Hsu & Hasmath, Reference Hsu and Hasmath2014, p. 522). This study highlights the necessity of studying SEs and social innovation in more diverse contexts to generalize findings, synthesize knowledge, and gain a deeper understanding of how the embedded institutional contexts shape SE development (Kerlin, Reference Kerlin2010; Stott & Tracey, Reference Stott and Tracey2018; Tauber, Reference Tauber2021).

Taken together, this study enriches budding research in Chinese SEs (e.g., Bhatt et al., Reference Bhatt, Qureshi and Riaz2019; Bi & Yu, Reference Bi and Yu2023; Hua, Reference Hua2021; Yin & Chen, Reference Yin and Chen2018; Zhao, Reference Zhao, Chandra and Wong2016). It sheds light on the opportunities of emerging SEs and their social innovation for social development. Yet, Chinese SEs confront significant political challenges and institutional constraints in their social innovation efforts. The SE and civil society sector, although deeply suppressed by the state, continues to play an important role in addressing social issues in China. Our findings speak to these realities and highlight the state’s dominant role in shaping the institutional complexity on the ground. In particular, the social–market complementarity, due to the dominance of the state logic, presents a novel contribution to research on SEs and social innovation.

Limitations and Future Research

This research has several limitations that provide opportunities for future research. First, this research employed snowball sampling, which might be subject to selection bias, and most SEs studied were relatively young and small. These characteristics may limit the transferability of the findings to all types of SEs, particularly big SEs with mature business models. Future research may employ quantitative analyses (e.g., Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cai and Song2023) to examine how SEs cope with institutional complexity. Future research may examine the complex state–society–market dynamics in SEs in diverse contexts, such as the market–state relationship in SEs and the heterogeneity in state influence at various levels.

Second, due to the methodological orientation (i.e., a grounded theory approach), we did not compare different types of SEs. Future research may examine how legal forms (e.g., nonprofit vs. for-profit SE) and other key attributes (e.g., mission, age, size) may influence SE dynamics. Future research may also study a more homogeneous group of Chinese SEs by specifying similar legal form, social mission, geographic area, or revenue structure.

Finally, our data were collected in 2016, a transitional period when China’s first national Charity Law, “the single largest change in civil society governance in recent decades” (Spires, Reference Spires2020, p. 572), was implemented. While the law seemingly relaxed NGO registration requirements and public fundraising constraints for grassroots organizations, it did not meaningfully change “the political dynamics that have long limited the development of grassroots civil society in China” (p. 581). Because of their ambiguity and repression, these regulatory changes seem to further restrict civil society activities rather than support or enable them (Pan & Xu, Reference Pan and Xu2022; Ye, Reference Ye2021). Nevertheless, future research may find important changes in the dynamics documented here.

Conclusion

Crafting SEs based on a better understanding of how they function in diverse sociopolitical contexts has the potential to generate significant social value. In this research, we uncovered considerable tension between social-welfare and state logics for Chinese SEs; the dominance of the state logic in Chinese SEs (re)configures the social–market relationships to be compatible. Thus, managing institutional complexity can be seen as a persistent source of struggle for social value creation, both in capitalist systems where social-welfare and market logics are conflicting and in authoritarian contexts where social-welfare and state logics are contradictory. The dynamics animating the institutional complexity Chinese SEs confront hold lessons that reach beyond China in other politically restrictive contexts, which are often marked with official censorship and information control, and government actors preoccupied with social stability and public security and that repress independent, large-scale civil organizations and associations calling for democratic reforms. As promising change agents, SEs operating under authoritarian regimes must attend to the often-competing institutional demands of government agencies at various administrative levels and strategically adapt their innovation orientations to their sociopolitical environment for survival and legitimacy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Michelle Shumate, Noshir Contractor, Ned Smith, Klaus Weber, John Almandoz, Milo Wang, and participants of the EURAM conference (The Quest for Social Impact: Opportunities and Challenges for Hybrid Organizations track) and Academy of Management OMT Division Paper Development and Workshop for their constructive feedback and insightful comments on the earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (SES-1730079), Buffet Institute for Global Studies at Northwestern University, and Rutgers University School of Communication and Information faculty start-up funding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.