Introduction

The beneficial health and well-being outcomes of volunteering are well documented. Among other things, volunteering can improve the physical and mental health of volunteers (Alspach Reference Alspach2014; Fegan and Cook Reference Fegan and Cook2014; Salt et al. Reference Salt, Crofford and Segerstrom2017; Yeung et al. Reference Yeung, Zhuoni and Tae Yeun2017), provide a positive pathway for those experiencing social isolation (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Buris, Townsend and Ebden2010; South et al. Reference South, White and Gamsu2013), reduce hospital service usage (Kim and Konrath Reference Kim and Konrath2016), and help connect services to at-risk groups (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Buck and South2018; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Springett, Croot, Booth, Campbell, Thompson and Yang2015). The intrinsic value of volunteering and the societal benefits that result from increased volunteerism are increasingly recognised by policy makers (O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, Deaton, Durand, Halpern and Layard2014). In the United Kingdom (UK), for example, volunteering is framed as an integral part of the health and care system (Department of Health 2011; Naylor et al. Reference Naylor, Mundle, Weaks and Buck2013) and an activity that should be promoted to support greater self-care and prevention efforts in communities (NHS England Reference England2014; People and Communities Board 2016). Whilst there is wide endorsement of the benefits of volunteering for volunteers and recipients of volunteering, and to communities and society more generally, any concerns around potential inequalities in volunteering do not feature strongly in what is a broadly positive discourse. However, there are marked variations in volunteering prevalence both between and within countries and emergent patterns as to who is most likely to volunteer. There is a tenfold variation in volunteering rates across Europe (Hupert et al. Reference Hupert, Marks, Clark, Siegrist, Stutzer, Vittersø and Wahrendorf2009). In England, 27% of the adult population take part in formal volunteering ‘regularly’ (once a month) and 42% do so ‘occasionally’ (less than once a month but more than once a year) (Cabinet Office 2016). The variations in prevalence and therefore the unequal distribution of health and well-being benefits from volunteering suggest that this may be a health inequalities issue. The aim of the paper is to provide an overview of both the breadth and interconnectedness of what helps or hinders volunteering for a selection of social demographic groups at risks of experiencing disadvantage. It extends and updates existing empirical and theoretical insights on this topic by adopting a health equity lens to suggest that underlying social inequalities present substantive barriers to volunteering that must be addressed to promote greater access. This paper explores barriers to volunteering that exist at structural and institutional as well as personal levels. We understand ‘barriers’ to mean any factor or combination of factors that constrains engagement in volunteering whether at structural, institutional, or personal levels. The paper shifts the focus away from the level of individual choice and towards the influence of broader patterns of social exclusion and economic inequality as major determinants of volunteerism.

Volunteering is not an irrational act, and inquiry into the philosophical, sociological, and psychological bases for decisions to undertake such work is needed (Musick and Wilson Reference Musick and Wilson2007). Work commitments are the most frequently cited reason for not volunteering in England (The National Archives 2016). Other reasons include childcare commitments and looking after the home, doing other things, not knowing about volunteering opportunities, study commitments, looking after an elderly relative, disability, and age. Volunteer prevalence is not just an individual choice—to volunteer or not—but is also affected by what other people are thinking and doing (Wilson and Music Reference Wilson and Musick1997). Like paid work, a ‘market’ exists for volunteer labour in which admittance is conditional on one’s qualifications (Wilson and Music Reference Wilson and Musick1997). Wilson (Reference Wilson2012) supposes that volunteerism is based on a combination of one’s subjective dispositions (i.e. individual personality traits, motives, attitudes, norms, and values), personal resources, life course experiences, and social context. Similarly, Wilson and Musick (Reference Wilson and Musick1997) suggest that entry into the volunteer labour force requires three different kinds of resources: human, social, and cultural capital. Clearly, a complex interaction of variables influences why volunteers do what they do and why others decline to volunteer. This paper explores this mix of variables for specific demographic groups by using a structural determinants framework which demonstrates how barriers and facilitating factors exist through individual, interpersonal/familial, work environment/institutional and broader socio-economic and political levels.

Methods

In November 2015, Volunteering Matters, a UK charity concerned with supporting and promoting inclusive volunteering, instigated a collaborative project to embed more fully into the health system an understanding of volunteering as an effective public health intervention and a means of addressing social exclusion and health inequalities. A key objective was to identify actions to enable those less able to volunteer to overcome barriers and gain the health and well-being benefits of volunteering. A rapid evidence review was commissioned to inform development of proposals for policy and practice.

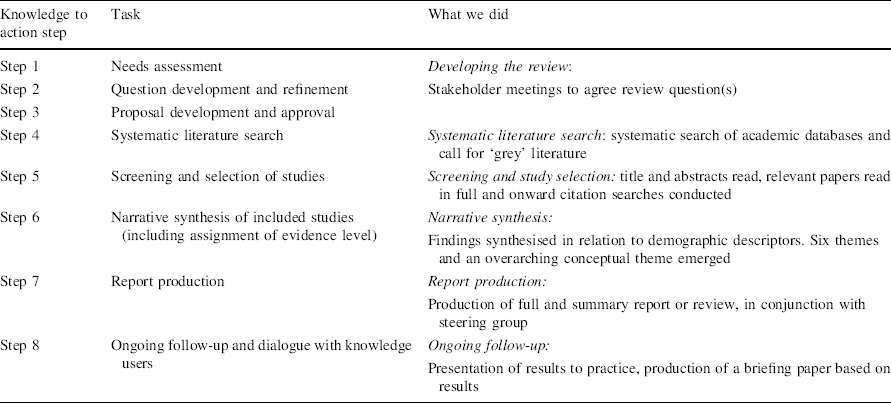

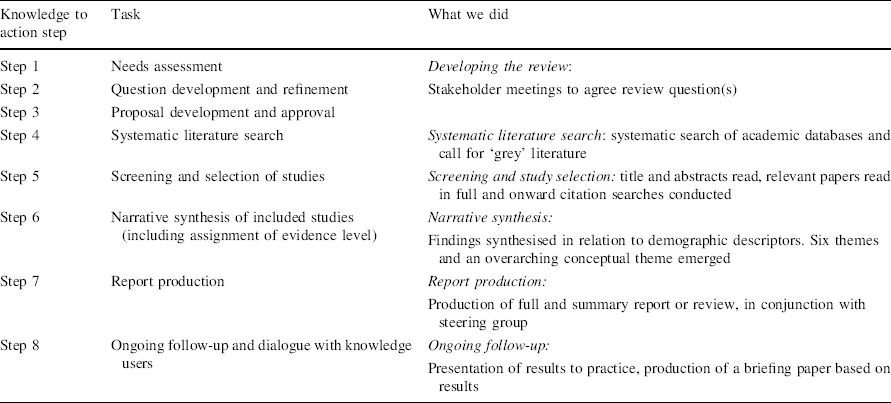

Our review methodology maps to the eight steps of a Knowledge to Action ‘evidence summary’ described by Khangura et al. (Reference Khangura, Konnyu, Cushman, Grimshaw and Moher2012) (see Table 1). This approach was appropriate due the requirement for a summary of existing knowledge and scoping of key barriers to inform later policy advocacy. Whilst ‘systematic reviews’ are often considered the preeminent mode of comprehensively synthesising evidence, this may not always be the case, particularly where clarification and insight is needed over identifying that which is common in the findings (Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Thorne and Malterud2018). Evidence summaries—and the overall class of ‘rapid reviews’ into which they fall—are a streamlined approach to synthesising available evidence within a short time frame to serve as an information brief for discussion on policy issues and support the direction and evidence base for policy initiatives (Khangura et al. Reference Khangura, Konnyu, Cushman, Grimshaw and Moher2012; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Newman and Oliver2013; Varker et al. Reference Varker, Forbes, Dell, Weston, Merlin, Hodson and O’Donnell2015). Provided the limitations are sufficiently understood and procedures transparent, the overview provided through rapid review may be considered reasonable and appropriate in the context of informing policy and decision makers concerned with efficacy or effectiveness (Khangura et al. Reference Khangura, Konnyu, Cushman, Grimshaw and Moher2012; Varker et al. Reference Varker, Forbes, Dell, Weston, Merlin, Hodson and O’Donnell2015).

Table 1 Outline of our rapid review procedure mapped to knowledge to action evidence summary

Knowledge to action step |

Task |

What we did |

|---|---|---|

Step 1 |

Needs assessment |

Developing the review: Stakeholder meetings to agree review question(s) |

Step 2 |

Question development and refinement |

|

Step 3 |

Proposal development and approval |

|

Step 4 |

Systematic literature search |

Systematic literature search: systematic search of academic databases and call for ‘grey’ literature |

Step 5 |

Screening and selection of studies |

Screening and study selection: title and abstracts read, relevant papers read in full and onward citation searches conducted |

Step 6 |

Narrative synthesis of included studies (including assignment of evidence level) |

Narrative synthesis: Findings synthesised in relation to demographic descriptors. Six themes and an overarching conceptual theme emerged |

Step 7 |

Report production |

Report production: Production of full and summary report or review, in conjunction with steering group |

Step 8 |

Ongoing follow-up and dialogue with knowledge users |

Ongoing follow-up: Presentation of results to practice, production of a briefing paper based on results |

Steps 1–3: Developing the Review

The review was undertaken between in January 2016 and May 2017 by two researchers from the Centre of Health Promotion Research (KS, JS), with consultative support provided by another (AMB). The research team, alongside representatives from Volunteering Matters and The King’s Fund, formed the project steering group. Decisions about the review (i.e. specific research question, initial findings, and analysis) were discussed with the steering group throughout the review process.

The aim of the review developed iteratively. Following initial steering group discussion, broad questions concerning the outcomes of, and processes involved in, volunteering were identified (i.e. ‘what is the relationship between volunteering and health inequalities?’, ‘how can statutory and non-statutory services engage with marginalised groups/individuals as volunteers?’). Through further discussion and preliminary literature searches, it was decided to narrow the focus of the review to inequalities within volunteering and to the specific research question. Moving beyond descriptions of volunteer prevalence, the review focused on inequalities across various socio-economic domains.

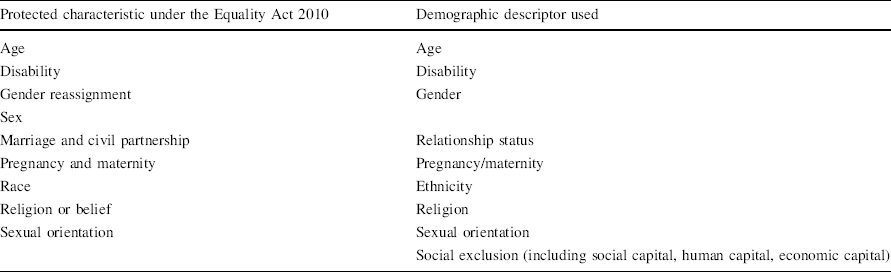

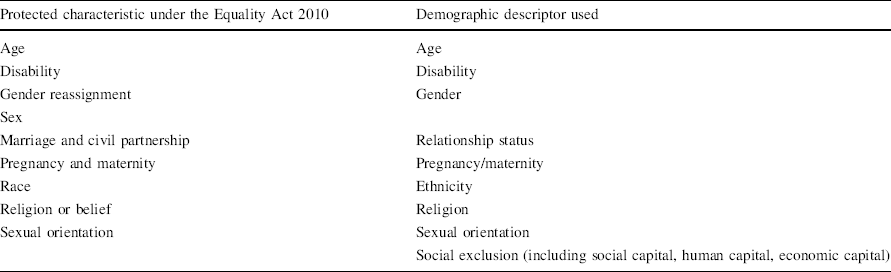

To explore barriers across a range of population groups where there is potential for disadvantage, we used the nine characteristics protected by the UK Equality Act 2010 (i.e. age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, sexual orientation) as an initial framework to map literature.

The specific research question guiding the review was: What helps and hinders people—especially those at risk of social exclusion—from taking part in volunteering? Barriers were identified as any factor or combination of factors that constrained engagement in volunteering whether at structural, institutional or personal levels (Harden et al. Reference Harden, Sheridan, McKeown, Dan-Ogosi and Bagnall2015).

Step 4: Systematic Literature Search

A systematic search of published and ‘grey’ literature concerning what helps and hinders people to volunteer was undertaken. To ensure the enquiry was broad and encompassed the multitude of exclusionary forces acting on potential volunteers, we adapted the characteristics protected under the UK’s Equality Act 2010 into a framework to guide our search terms and results synthesis (see Table 2). We also included an additional ‘social exclusion’ descriptor to capture any crosscutting issues relating to socio-economic disadvantage.

Table 2 Adapted protected characteristics (Equality Act 2010) framework

Protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010 |

Demographic descriptor used |

|---|---|

Age |

Age |

Disability |

Disability |

Gender reassignment |

Gender |

Sex |

|

Marriage and civil partnership |

Relationship status |

Pregnancy and maternity |

Pregnancy/maternity |

Race |

Ethnicity |

Religion or belief |

Religion |

Sexual orientation |

Sexual orientation |

Social exclusion (including social capital, human capital, economic capital) |

The literature search was conducted in March 2016 using Leeds Beckett University Library’s ‘Discover’ portal, which searched over 120 academic databases, including health specific databases (i.e. MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, SPORTDiscus). A set of search terms relating to the concept of ‘volunteering’ was combined with one or more sets of ‘demographic descriptor’ search terms (see supplementary material for full search strategy). Results were limited to English language publications and academic journals. No date or geographical restriction was applied. Research from a non-UK context was included as the review intended to identify broad potential barriers to volunteering rather than specific barriers experienced by those in the UK.

To identify relevant unpublished ‘grey’ literature, in January 2016 Volunteering Matters issued a call for evidence via the Network of National Volunteer-Involving Agencies (NNVIA) network. Members were asked to forward to the research team reports or evidence concerning barriers to volunteering, particularly for groups thought to be marginalised from volunteering.

Step 5: Screening and Study Selection

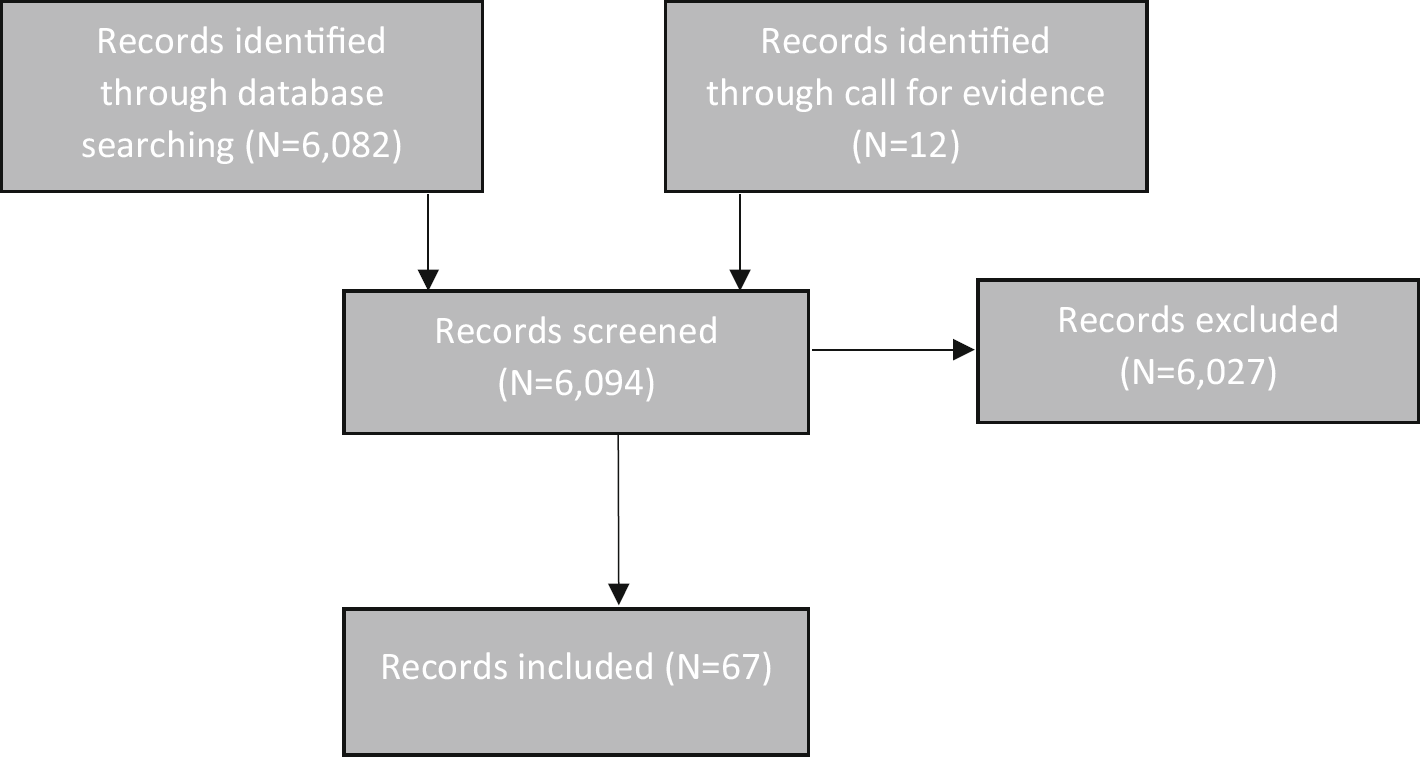

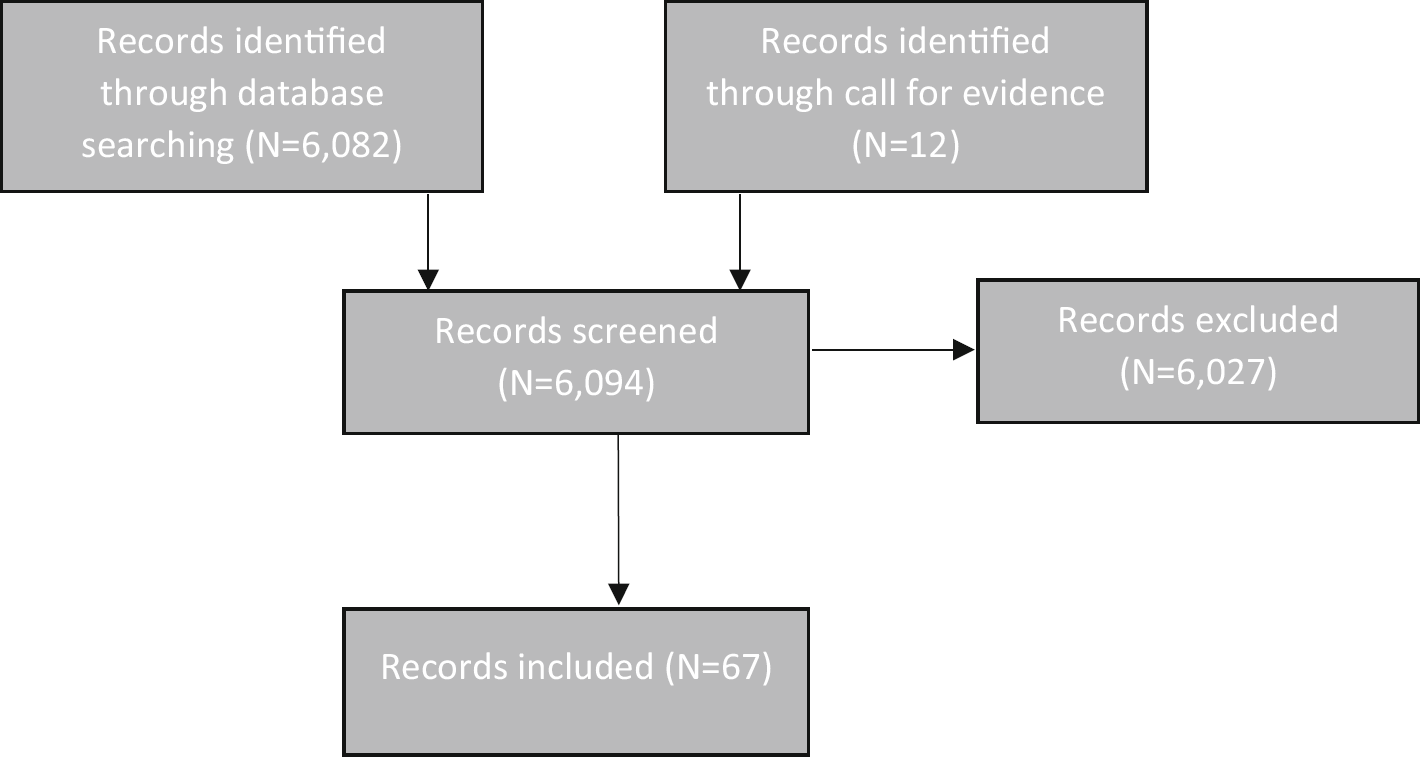

In total, sixty-seven records were included in the review (see Fig. 1). The search yielded 6094 items, consisting of 6082 published articles and twelve grey literature items. All titles and abstracts were initially screened for relevance by one member of the research team. Full papers were obtained and subjected to further screening if they reported an empirical study, systematic review, or relevant discussion paper about: (1) actual or perceived barriers to volunteering; (2) inequalities in volunteering rates; or (3) psychological factors (i.e. motivations) preventing or discouraging volunteering in relation to one or more demographic descriptors.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of literature search and screening results

Step 6: Narrative Synthesis

Data were extracted by one reviewer (KS) from each included article concerning research methodology (including research methods and sample data), country in which the research was conducted, demographic descriptor(s) under exploration, and identified barriers to volunteering.

The extracted data from across the sixty-seven included records were synthesised narratively (Popay Reference Popay2006). The identified barriers to volunteering were described in relation to each demographic descriptor. Six themes were then drawn out: socialisation, institutional factors, personal resources, view of volunteering, caring responsibilities, and employment. A seventh theme around social exclusion was also drawn out as a crosscutting, overarching concept. This narrative approach served to deepen understanding of the pertinent issues rather than just provide a summation of what is known (Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Thorne and Malterud2018).

Steps 7–8: Dissemination and Follow-up

In the first instance, the findings of the review were written up by the research team as a report for Volunteering Matters (Southby and South Reference Southby and South2016b), with an accompanying summary report (Southby and South Reference Southby and South2016a). The report went through a number of iterations following feedback from stakeholders.

The findings of the review were presented at a series of events in England (Coventry, York, Sheffield, Manchester) in the summer of 2017 where stakeholders from both statutory and third-sector organisations had opportunities to comment on the relevance and significance of the review. Volunteering Matters produced a briefing based on the findings of the review to start to raise the issues on the policy agenda and to stimulate debate about what practical actions could be done to address volunteering inequalities at a local, regional, and national level.

Findings

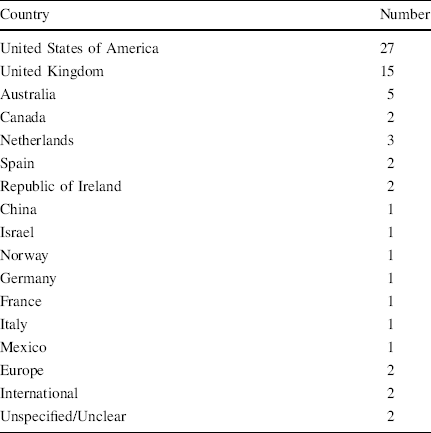

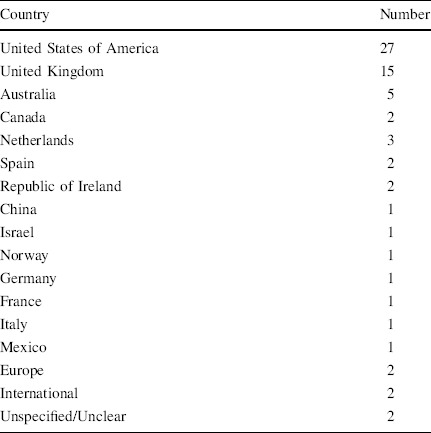

Table 3 shows that the included studies were almost all from high-income countries. The evidence is dominated by studies from the USA (n = 27) and the UK (N = 15).

Table 3 Geographical focus of included studies

Country |

Number |

|---|---|

United States of America |

27 |

United Kingdom |

15 |

Australia |

5 |

Canada |

2 |

Netherlands |

3 |

Spain |

2 |

Republic of Ireland |

2 |

China |

1 |

Israel |

1 |

Norway |

1 |

Germany |

1 |

France |

1 |

Italy |

1 |

Mexico |

1 |

Europe |

2 |

International |

2 |

Unspecified/Unclear |

2 |

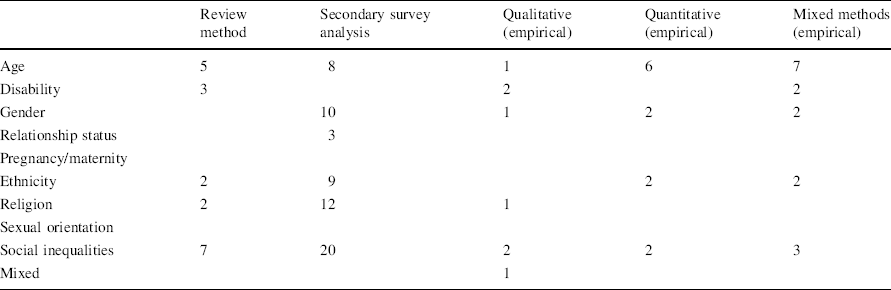

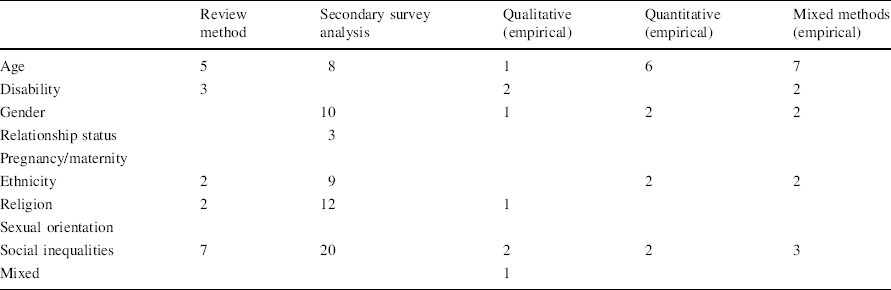

The content of the papers was diverse with some discussing issues for multiple demographic groups. The greatest number of articles discussed ‘social inequalities’ and volunteering (n = 34), followed by ‘age’ (n = 27), ‘religion’ (n = 15), ‘ethnicity’ (n = 15), ‘gender’ (n = 15), and then ‘disability’ (n = 7) and ‘relationship status’ (n = 3). No literature was identified in relation to ‘sexual orientation’ or ‘pregnancy/maternity’ and volunteering, although three papers discussed having children in the household and volunteering. This may reflect a dearth of evidence in these areas rather than a lack of barriers to volunteering for these groups. The largest number of papers (n = 33) carried out secondary analysis of existing quantitative survey data. Eleven papers utilised a review methodology, ranging from narrative reviews to meta-analysis. Twenty-three papers collected empirical data, including quantitative data (n = 9), qualitative data (n = 7), and mixed methods (n = 7). Mapping the methodologies used to explore barriers to volunteering for different demographic groups (see Table 4) illustrates the reliance to date on survey methodologies and a relative dearth of qualitative and mixed-methods empirical evidence. Contrary to this general pattern is the experience of people with disabilities (broadly defined) who have been the subject of relatively more qualitative and mixed-methods research and little survey analysis.

Table 4 Matrix of demographic descriptor and methodology for included papers

Review method |

Secondary survey analysis |

Qualitative (empirical) |

Quantitative (empirical) |

Mixed methods (empirical) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Age |

5 |

8 |

1 |

6 |

7 |

Disability |

3 |

2 |

2 |

||

Gender |

10 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

Relationship status |

3 |

||||

Pregnancy/maternity |

|||||

Ethnicity |

2 |

9 |

2 |

2 |

|

Religion |

2 |

12 |

1 |

||

Sexual orientation |

|||||

Social inequalities |

7 |

20 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

Mixed |

1 |

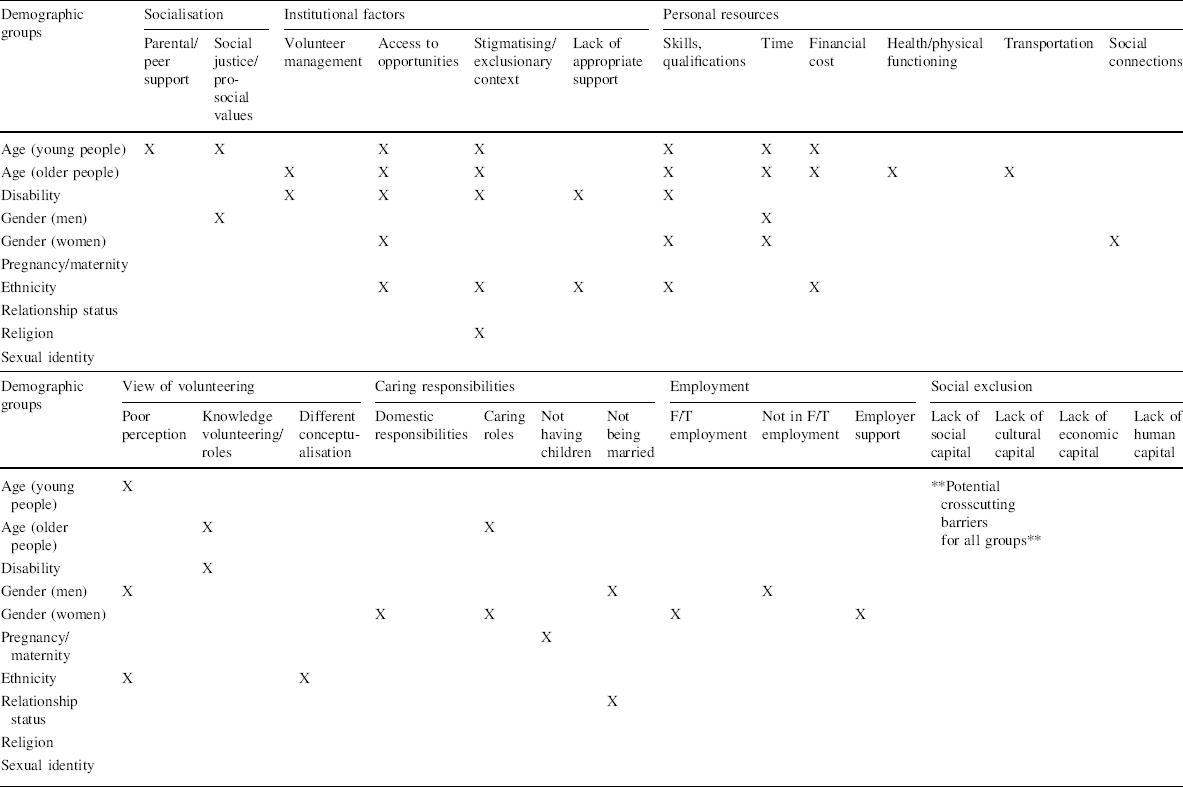

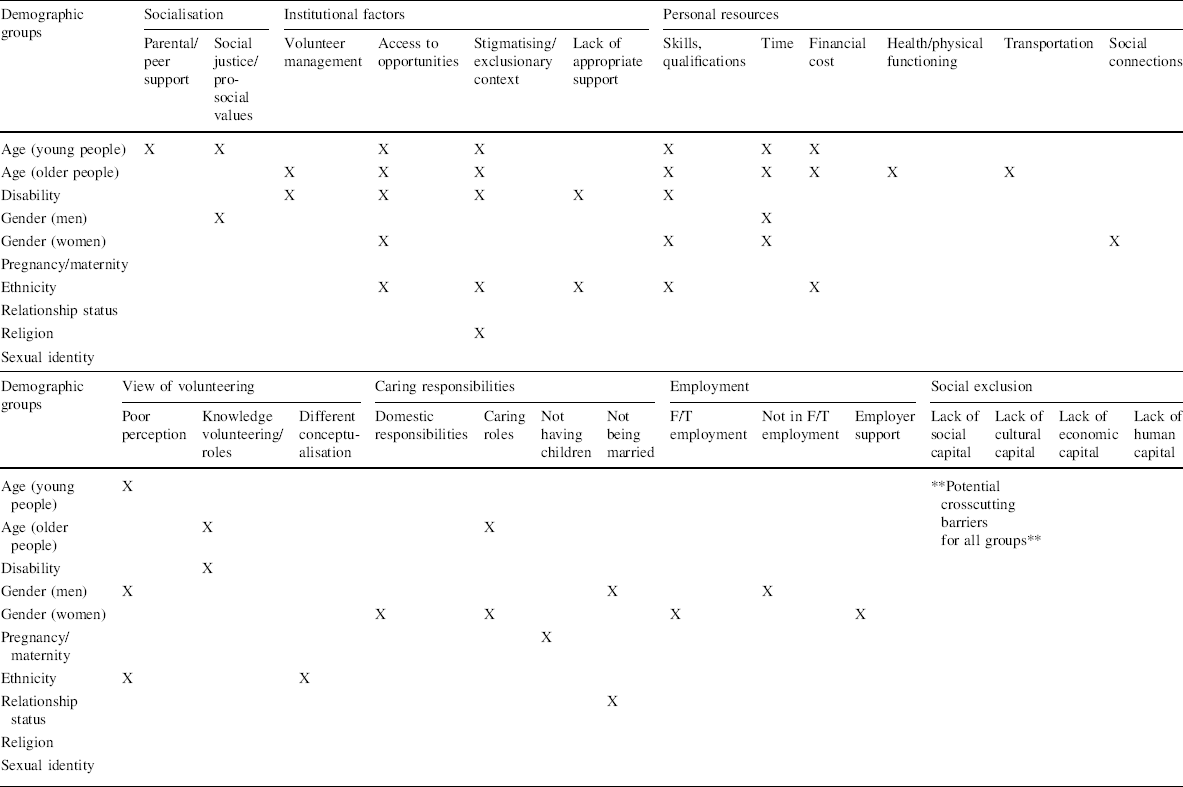

The identified papers described a range of barriers affecting volunteering for different demographic groups. Table 5 maps the identified barriers to volunteering to the different demographic groups. It demonstrates the breadth of potential issues for different groups but not the volume or quality of identified evidence. Some groups, such as ‘age’, ‘disability’, and ‘gender’, appear to experience a broader range of barriers to volunteering.

Table 5 Identified potential barriers to volunteering including crosscutting themes, by demographic group

Demographic groups |

Socialisation |

Institutional factors |

Personal resources |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Parental/peer support |

Social justice/pro-social values |

Volunteer management |

Access to opportunities |

Stigmatising/exclusionary context |

Lack of appropriate support |

Skills, qualifications |

Time |

Financial cost |

Health/physical functioning |

Transportation |

Social connections |

|

Age (young people) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

Age (older people) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

Disability |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

Gender (men) |

X |

X |

||||||||||

Gender (women) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

Pregnancy/maternity |

||||||||||||

Ethnicity |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

Relationship status |

||||||||||||

Religion |

X |

|||||||||||

Sexual identity |

||||||||||||

Demographic groups |

View of volunteering |

Caring responsibilities |

Employment |

Social exclusion |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Poor perception |

Knowledge volunteering/roles |

Different conceptualisation |

Domestic responsibilities |

Caring roles |

Not having children |

Not being married |

F/T employment |

Not in F/T employment |

Employer support |

Lack of social capital |

Lack of cultural capital |

Lack of economic capital |

Lack of human capital |

|

Age (young people) |

X |

**Potential crosscutting barriers for all groups** |

||||||||||||

Age (older people) |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

Disability |

X |

|||||||||||||

Gender (men) |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||

Gender (women) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||

Pregnancy/maternity |

X |

|||||||||||||

Ethnicity |

X |

X |

||||||||||||

Relationship status |

X |

|||||||||||||

Religion |

||||||||||||||

Sexual identity |

||||||||||||||

Among older people, poor health and physical functioning, poverty, stigma, lack of skills, poor transport, time constraints, inadequate volunteer management, and other caring responsibilities are highlighted in the identified literature as potential barriers to volunteering. For younger people, a lack of institutional support and not being socialised into volunteering roles are barriers identified in the literature. The literature also indicates that younger people may have negative perceptions of volunteering, as well as not having time to volunteer. A significant barrier to volunteering for people with a disability can be the disablist attitudes of others, including a stigma associated with impairment and perceptions that people with a disability have very little to offer or that supporting someone with a disability to volunteer will be too resource intensive. Some people with a disability may themselves express concerns about participating outside of ‘safe’ spaces and may sometimes require additional skills development to take part in volunteering. Men and women may have different motivations for volunteering and all identified barriers to volunteering appear to have a gender element. The identified papers suggest women are required to devote a greater proportion of their ‘free time’ in order to volunteer than men. Women are constrained to a greater extent than men by housework and additional caring responsibilities (for children and elderly relatives) and are likely to receive less support from employers. No research on volunteering and pregnancy/maternity (or paternity) was found in this review, although having (school aged) children in the household was found to be positively associated with both formal and informal volunteering in three identified papers and in survey data. Raising children may make parents more aware of volunteering opportunities (i.e. through schools and youth groups/activities) and may create a societal expectation to socialise children into socially responsible roles. The papers suggest that different cultures may think about and value volunteering differently. People from minority ethnic groups may also experience limited access to volunteering infrastructures, feel alienated or excluded within volunteer organisations and environments, have fewer skills and resources to volunteer, and experience fewer positive outcomes from volunteering. The papers discussing volunteering and relationship (marital) status generally suggest a positive relationship between marriage and volunteering. However, a changing backdrop of family structures may be affecting the relationship between marriage and volunteering, particularly for women in terms of paid employment, having fewer children and having additional family care responsibilities. The identified literature focuses on heterosexual marriage, and no literature was identified specifically in relation to same-sex marriage or civil partnership. Church (or equivalent) attendance, in particular, is an influential factor in volunteering, possibly creating larger social networks and more opportunities to engage in volunteering, although the relationship to volunteering varies between religious affiliations. Some of the identified research warns that religion may form exclusionary boundaries around who can volunteer and what kind of activities are undertaken. Factors related to broader exclusionary processes and social, human, cultural, and economic capital have been identified in the research literature as key to participation in volunteering. The literature suggests that whilst volunteering is a mechanism for individuals to boost their personal, social, financial, and cultural resources in order to overcome exclusion, volunteering also consumes one’s resources. This means that those with less personal and social resources are less able to volunteer and gain the associated benefits.

Whilst different demographic groups may experience unique barriers to volunteering, the review highlighted areas of commonality. For example, both older people (Hussein and Manthorpe Reference Hussein and Manthorpe2014) and those with disabilities (Farrell and Bryant Reference Farrell and Bryant2009; Fegan and Cook Reference Fegan and Cook2012; Roker et al. Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1998; Trembath et al. Reference Trembath, Balandin, Stancliffe and Togher2010) experienced their volunteering being limited to specific roles and/or organisations. Moreover, barriers to volunteering associated with specific demographic groups were compounded (and/or mitigated) by multiple socio-economic factors. For example, the barriers to volunteering experienced by different age groups were found to be affected by the gender, ethnicity, disability, socio-economic status, family background, and education of potential volunteers (Cramm and Nieboer Reference Cramm and Nieboer2015; Kay and Bradbury Reference Kay and Bradbury2009; Mainar et al. Reference Mainar, Servós and Gil2015; McNamara and Gonzales Reference McNamara and Gonzales2011; Nicol Reference Nicol2012; Pantea Reference Pantea2013). A narrative account is now given of the main crosscutting factors affecting volunteering identified through the review.

Socialisation

The influence of socialisation on volunteering is most notably documented with regard to young people. Norms and values gained from friends and family help to explain why some people volunteer and others do not (Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999; Ishizawa Reference Ishizawa2015). Parents and friends who do not volunteer (Mainar et al. Reference Mainar, Servós and Gil2015; van Goethem et al. Reference van Goethem, van Hoof, van Aken, Orobio de Castro and Raaijmakers2014), do not hold strong social justice values (Webber Reference Webber2011), or do not see volunteering as part as their identity (Marta and Pozzi Reference Marta and Pozzi2008) are likely to dissuade youth volunteering. Individuals are also influenced by their social environments across the life course, including norms, values, customs, and habits, which all affect volunteering behaviour (Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999; Ishizawa Reference Ishizawa2015; McNamara and Gonzales Reference McNamara and Gonzales2011; Youssim et al. Reference Youssim, Hank and Litwin2015). For example, being religious may encourage volunteering through the teaching of obligation (Son and Wilson Reference Son and Wilson2012), whilst the process of teaching children socially responsible roles may encourage parents to volunteer (Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006).

Institutional Factors

The volunteering of different demographic groups also appears to be affected, to varying degrees, by the organisation and conduct of volunteer-involving organisations. Poor volunteer management has been found to be a barrier to volunteering for older people (Fengyan et al. Reference Fengyan, Morrow-Howell and Songiee2009) and men (Kolnick and Mulder Reference Kolnick and Mulder2007). Access to volunteering opportunities can be a barrier to volunteering. Clear entry points into volunteering and institutional support (i.e. school, church, community groups) are key facilitators for young people to volunteer (Webber Reference Webber2011). Similarly, those from minority ethnic groups may have limited access to formal volunteer infrastructures (Rotolo and Wilson Reference Rotolo and Wilson2014). Volunteering might also be organised to take place in unfamiliar, alienating, or non-inclusive environments. Older people (Connolly and O’shea Reference Connolly and O’shea2015; Suanet et al. Reference Suanet, Broese van Groenou and Braam2009), people with physical and/or intellectual impairments (Farrell and Bryant Reference Farrell and Bryant2009; Fegan and Cook Reference Fegan and Cook2012; Roker et al. Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1998), young people (Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999), and people from minority ethnic groups (Bortree and Waters Reference Bortree and Waters2014; Ockenden Reference Ockenden2007) have all reported not feeling welcome as volunteers within volunteer-involving organisations. Within voluntary roles, individuals may not receive appropriate support, discouraging them from volunteering further. Commitment to volunteers with a disability may be viewed as additional work (Roker et al. Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1998) and therefore a low service priority for organisations with limited time and resources (Young and Passmore Reference Young and Passmore2007). The availability of institutional support helps to explain why some young people volunteer and others do not (Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999; Ishizawa Reference Ishizawa2015).

The church (or other religious equivalent), for example, is an often discussed institution in the volunteering literature. Church attendance has been found to be an influential factor in volunteering (Layton and Moreno Reference Layton and Moreno2014; Storm Reference Storm2015), creating larger social networks, and more opportunities for interaction and the acquisition of social and administrative skills involved in civic engagement/volunteering. However, the relationship is contingent on other factors, including religion and denomination. In the United States of America (USA), for example, volunteering has been found to be more strongly tied to attendance at black and evangelical churches compared to those who attend Catholic and mainline protestant churches (Johnston Reference Johnston2013; Wilson and Janoski Reference Wilson and Janoski1995). Within African-American communities in the USA, the church may have a more mobilising effect for volunteering than in ‘white’ communities (Musick et al. Reference Musick, Wilson and Bynum2000). In the UK, some researches have found that religious ‘pluralists’—those who believe religions other than their own contain some basic truths—are more likely to volunteer than any other groups of religious people (Birdwell and Littler Reference Birdwell and Littler2012). Moreover, whilst facilitating access to voluntary opportunities for some, the church can also form exclusionary boundaries around voluntary activity (Pathak and McGhee Reference Pathak and McGhee2015).

Personal Resources

Individuals’ personal resources have been found to be a barrier and/or an enabling factor towards volunteering. Participating in volunteering requires an individual investment of time, money, effort, and skill (i.e. for travel, expenses). Lack of time, for various reasons, has been found to be a barrier to volunteering for young people (Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999; Mainar et al. Reference Mainar, Servós and Gil2015; Nicol Reference Nicol2012) and both men and women; women may devote a greater proportion of their ‘free time’ to volunteering (Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006; Windebank Reference Windebank2008). Lack of financial resources to cover the costs associated with volunteering has been found to be a barrier for older people (Cattan et al. Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Fengyan et al. Reference Fengyan, Morrow-Howell and Songiee2009), young people (Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999; Mainar et al. Reference Mainar, Servós and Gil2015; Nicol Reference Nicol2012), and people from minority ethnic groups (Mesch et al. Reference Mesch, Rooney, Steinberg and Denton2006; Musick et al. Reference Musick, Wilson and Bynum2000). Some people may not be able to take part in volunteering due to ill health. This has been found to be the case among older people, where poor health and physical functioning negatively correlates with volunteering (Cramm and Nieboer Reference Cramm and Nieboer2015; Lum and Lightfoot Reference Lum and Lightfoot2005). Older people (Fengyan et al. Reference Fengyan, Morrow-Howell and Songiee2009), young people (Bang Reference Bang2015; Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999), people with physical and/or intellectual impairments (Young and Passmore Reference Young and Passmore2007), women (Bryant et al. Reference Bryant, Jeon-Slaughter, Kang and Tax2003; Einolf Reference Einolf2011), and people from minority ethnic groups (Mesch et al. Reference Mesch, Rooney, Steinberg and Denton2006; Musick et al. Reference Musick, Wilson and Bynum2000) all face barriers to volunteering when they are perceived as lacking the desired skills for volunteer roles.

Understanding of Volunteering

The identified papers indicate that different demographic groups may think about and conceptualise volunteering differently, affecting their propensity to volunteer. Older people may lack knowledge around volunteer opportunities and roles (Fengyan et al. Reference Fengyan, Morrow-Howell and Songiee2009). Other groups, including young people (Davis Smith Reference Davis Smith1999) and people with physical and/or intellectual impairments (Balandin et al. Reference Balandin, Llewellyn, Dew, Ballin and Schneider2006), may hold negative views about volunteering. People from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds may also view volunteering differently. For example, African-American populations are less likely to see ‘charity’ as the best way to address social problems (Musick et al. Reference Musick, Wilson and Bynum2000). In Chinese and Japanese cultures, older people may be less inclined to volunteer because of the implication that they are not being appropriately cared for by their family (Fengyan et al. Reference Fengyan, Morrow-Howell and Songiee2009; Warburton and Winterton Reference Warburton and Winterton2010).

Caring Responsibilities

Family structures and the way caring (and domestic) responsibilities are divided within households have been shown to impact volunteering. In general, marriage (McNamara and Gonzales Reference McNamara and Gonzales2011; Plagnol and Huppert Reference Plagnol and Huppert2010; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006) and the presence of children (Einolf Reference Einolf2011; McNamara and Gonzales Reference McNamara and Gonzales2011; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006)—particularly of school age—in the household have been found to correlate with parents’ volunteering. Parents are thought to be ‘plugged into volunteering activities’ through school and youth activities (McNamara and Gonzales Reference McNamara and Gonzales2011, p. 500). Domestic and family responsibilities are a barrier to women’s volunteering more than men’s (Einolf Reference Einolf2011; Fyall and Gazley Reference Fyall and Gazley2015; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006; Windebank Reference Windebank2008). However, changing family structures (i.e. away from the ‘nuclear family’) and gender roles with regard to employment may be adversely affecting the relationship between volunteering and marriage, particularly for women (Ogunye and Parker Reference Ogunye and Parker2015) and for older people expected to take on greater caring roles (Fengyan et al. Reference Fengyan, Morrow-Howell and Songiee2009). Tiehen (Reference Tiehen2000) also finds that where married women are having fewer children, they may be less exposed to volunteering opportunities.

Employment

Conditions around employment have been found to affect volunteering of men and women in different ways. Men may be more likely to volunteer when they are in (full-time) employment (Fyall and Gazley Reference Fyall and Gazley2015; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006), whereas women who do not work or who work part-time have been found to be far more likely to volunteer both formally and informally (Helms and McKenzie Reference Helms and McKenzie2014). Women may be less likely than male colleagues to receive employer support for volunteering (MacPhail and Bowles Reference MacPhail and Bowles2009). In the USA, increases in paid employment (Tiehen Reference Tiehen2000) and additional family care responsibilities (Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006) may be a barrier to female volunteering.

Social Exclusion

The review has so far highlighted a range of barriers that may affect the capacity of different groups to volunteer. The final theme is how the unequal distribution of social, human, and economic capital resources profoundly affects volunteering. Studies conducting regression analyses of data from the USA (Lee and Brudney Reference Lee and Brudney2012; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998), Canada (Smith Reference Smith2012), Israel (Youssim et al. Reference Youssim, Hank and Litwin2015), Italy (Marta and Pozzi Reference Marta and Pozzi2008), and Spain (Mainar et al. Reference Mainar, Servós and Gil2015) all point to factors associated with broader exclusionary mechanisms—social, economic, and human capital—being significant influences on volunteering.

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating a significant positive relationship between social capital—the ‘ability of actors to secure benefits by virtue of membership in social networks’ (Portes Reference Portes1998, p. 6)—and philanthropic behaviour, including volunteering (Forbes and Zampelli Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014; Layton and Moreno Reference Layton and Moreno2014; Zhuang and Girginov Reference Zhuang and Girginov2012). People or groups with low levels of social capital may be less likely to volunteer because they may have less contact with diverse people or organisations that provide opportunities for volunteering (Cramm and Nieboer Reference Cramm and Nieboer2015; Forbes and Zampelli Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014; Lee and Brudney Reference Lee and Brudney2012; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998). The effects of social capital may be compounded by other factors such as education, being religious, and family background (Lee and Brudney Reference Lee and Brudney2012). A linked concept is ‘cultural capital’, with the ability to ‘act’ in a given social context in order to identify and avail volunteering opportunities transmitted from one generation to another within social groups (Youssim et al. Reference Youssim, Hank and Litwin2015).

A positive relationship between individuals’ level of education and skills—human capital—and volunteering has been observed in the USA (Forbes and Zampelli Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014; Ishizawa Reference Ishizawa2014; Mesch et al. Reference Mesch, Rooney, Steinberg and Denton2006; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998), Canada (Smith Reference Smith2012), mainland Europe (Plagnol and Huppert Reference Plagnol and Huppert2010), and Germany (Helms and McKenzie Reference Helms and McKenzie2014). Higher human capital is thought to enable individuals to make better use of their social networks in order to identify and utilise opportunities for volunteering (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998), whereas a lack of human capital may reduce individuals’ ambition and expectations of their own participation in volunteering (Brodie et al. Reference Brodie, Hughes, Jochum, Miller, Ockenden and Warburton2011).

Finally, economic capital has been linked to volunteering prevalence (Berliner Reference Berliner2013; Hussein and Manthorpe Reference Hussein and Manthorpe2014; Plagnol and Huppert Reference Plagnol and Huppert2010; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998). Higher income may allow more discretionary spending and afford people a greater stake in society (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998). Those with higher incomes may also have a higher social network density, creating more opportunities to volunteer. Conversely, for those lacking in economic capital, volunteering might be a luxury they cannot—literally and figuratively—afford (Berliner Reference Berliner2013; Plagnol and Huppert Reference Plagnol and Huppert2010; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2006).

Discussion

Volunteering encompasses a broad range of activities that help or benefit those beyond one’s immediate family or environment undertaken without the need for remuneration (Lee and Brudney Reference Lee and Brudney2012, p. 159). A commonly held defining feature of volunteering is that activities are freely chosen. However, the findings of this review suggest that these choices may be significantly constrained by structural level inequalities and aspects of the socio-cultural context.

Using the Equality Act 2010 ‘protected characteristics’ was a useful initial framework to explore factors affecting volunteering for different demographic groups. The review has highlighted the plethora of ‘levels’ of barriers to volunteering at different life stages (i.e. personal, familial, social, institutional, structural). Findings show differences between groups and some demographic descriptors, such as age, disability, and gender, appear to be associated with a broader range of barriers to volunteering. This may, however, be reflective of a dearth of evidence in other areas. It is surprising that no literature concerning barriers to volunteering and ‘sexual orientation’ was identified in this review given the strong traditions of citizen activism and volunteer/peer health programmes in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities (Gates et al. Reference Gates, Russell and Gainsburg2016). It may be that these activities are not called ‘volunteering’ within these communities. The variation in evidence about potentially disadvantaged groups merits further exploration using systematic review methods, with more sophisticated search strategies to locate literature.

This review contributes to a growing body of evidence identifying broader exclusionary mechanisms relating to social, economic, and human capital as a crosscutting concern to participation in volunteering (Lee and Brudney Reference Lee and Brudney2012; Mainar et al. Reference Mainar, Servós and Gil2015; Marta and Pozzi Reference Marta and Pozzi2008; Smith Reference Smith2012; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998; Youssim et al. Reference Youssim, Hank and Litwin2015). This is not to diminish the unique experience of individuals or groups. Rather, our analysis suggests that whilst different demographic groups encounter specific barriers to volunteering, these exist within a framework of structural factors related to broader, crosscutting exclusionary processes and social inequalities (see Table 5). This reflects Wilson and Music’s (Reference Wilson and Musick1997) finding that social statuses like age, race, and gender have only a largely indirect effect on volunteerism. Moreover, the interactions between demography and factors affecting volunteer participation are not simple, but compounded. For example, whilst women may have additional caring responsibilities and receive less employer support to volunteer compared to men, this experience is likely to be different depending on other attributes, including but not limited to age, socio-economic status, religion, or disability.

Volunteering is an activity that can bring health and well-being benefits to those involved and more broadly to communities and society (Public Health England 2015). However, volunteering has a social gradient, with people from more disadvantaged areas less likely to volunteer (Department for Communities and Local Government 2011; NNVIA - The Network of National Volunteer-Involving Agencies 2011). This means that those groups of people who may stand to gain the most from volunteering are least likely to take part. The variations in prevalence and therefore the unequal distribution of health and well-being benefits from volunteering suggest that this may be a health inequalities issue. The potential public health implications of volunteering mean there is much to be gained from broadening participation, particularly in the pathways and connections that can be made for disadvantaged groups. That there are significant barriers that stop people from volunteering has been recognised by government (Office of the Third Sector 2005). However, the dominant policy discourse around volunteering adopts an uncritical view of participation: that it is a matter of individual choice and that people are able to participate with ease. This is at odds with evidence from this review and elsewhere that participation in volunteering is socially determined by inequalities in access, opportunity, and resources. Particularly troublesome is the attachment of volunteer work to formal organisations, which means that communities or countries where the infrastructure of nongovernmental organisations outside the private sector is poorly developed will have fewer opportunities (Wilson Reference Wilson2012). Stakeholders should not focus solely on micro- or macro-barriers as our argument is that barriers occur at all ‘levels’ and that these levels are interconnected.

Given the relationship between wider exclusionary factors and volunteering, pathways to participation need to be developed in conjunction with addressing broader equity issues. Jenkinson et al. (Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Rtaylor and Trogers2013), reporting on a systematic review of the health and survival of volunteers, point out that the positive health effects of volunteering may in fact be due to selection bias and reverse causation and that the focus needs to be on widening participation for socially disadvantaged groups. So that people can experience the virtuous circle of volunteering when they choose to and gain maximum benefits in terms of their health and well-being, consideration needs to be given to how to foster greater human, economic, and social capital across society. Volunteering can be related to community membership (e.g. religion, ethnicity, social interest), and so greater cohesion within and between groups should be fostered to facilitate greater involvement.

Encouraging volunteering requires a life course approach to deal with different barriers and facilitators, starting with support for young people to become involved in volunteering through to ensuring those in old age can continue to contribute if they wish. More could be done to remove the stigma preventing people from volunteering and to highlight the diversity of volunteering, along with ensuring a range of opportunities are available. Provision to facilitate the involvement of people from different demographic groups in volunteering, including young people, those with disabilities and those from ethnic minorities, needs to be more personalised to the needs of respective groups. The review findings suggest that there is scope to improve the volunteer experience. This requires a systematic approach to addressing barriers and providing inclusive volunteer opportunities to ensure that people can choose to volunteer in ways where the most benefit can be had, and within diverse organisations and communities.

Limitations and Future Research

This review is not a comprehensive account of the barriers to volunteering, rather an overview of some pertinent issues and themes. Limited time and resource meant restrictions had to be placed on the breadth and depth of searching. There is a need for a comprehensive systematic review of the available evidence concerning barriers and facilitators to volunteering and their effects on and pathways to reducing social and health inequalities.

The review has drawn on evidence from a global perspective, as the intention was to provide a broad overview of the barriers to volunteering. The evidence in this review comes mostly from high-income countries, specifically the USA and UK, and so may not be relevant to medium- or low-income countries. This is not entirely surprising given documented publication bias towards the USA in the literature more generally (Yeung Reference Yeung2001). It is not clear the extent to which international studies can be synthesised when issues around volunteering are often dependent on social and cultural context, although there do appear to be shared issues. Further primary research and secondary data analysis of the barriers to volunteering in demographic groups on a country-by-country basis would be beneficial to confirm these findings.

Although a significant body of literature exists concerning volunteering and inequalities, there are gaps in our understanding of the barriers that particular demographic groups may experience. No research was identified exploring either pregnancy and/or maternity/paternity or sexual orientation and barriers to volunteering. The majority of the identified literature in relation to ethnicity or religion and volunteering was from a non-UK context. The literature concerning relationship status and volunteering exclusively focused on heterosexual marriage. Further primary research and secondary data analysis of volunteering patterns in relation to sexual orientation and disability would be beneficial in bridging current gaps in knowledge.

Conclusion

This paper is an attempt to understand the breadth and interconnectedness of factors affecting volunteering for different demographic groups. It has produced a map of individual and structural factors affecting volunteering for those with characteristics protected under the UK Equality Act 2010. Whilst different demographic groups experience distinct barriers to volunteering, crosscutting issues relating to broader exclusionary processes affect all ‘disadvantaged’ groups. This shifts the onus of volunteering away from the level of individual choice (a dominant factor emphasized in policy and practical discussions around promoting volunteering) and towards the influence of broader patterns of social exclusion and economic inequality as major determinants of volunteerism ability.

There is a body of knowledge on the health and well-being benefits of volunteering. The results of this review illuminate some major inequalities in access to, and participation in, volunteering that are related to socio-economic (dis)advantage. Whilst pro-social activity, including volunteering, is increasingly encouraged as a solution to health problems, particularly for those at risk of social isolation or poor mental health, there are questions about the success of this approach given that underlying social inequities present substantive barriers to volunteering, and must be addressed to promote greater access.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mandy James (Volunteering Matters) for her support throughout the review process. Further thanks goes to steering group members Duncan Tree (Volunteering Matters), Dave Buck (The King’s Fund), and Andrew Tyson (independent health consultant) for their support.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.