Introduction

The gender wage gap is a fundamental indicator of persistent gender inequalities in paid work globally. Its measurement varies across countries depending on the differences in the labour market structure as well as the policies and societal norms that affect the gender division of labour. Alternative measures and non-standardised estimates make gender pay inequality issues much more challenging and complex, especially in countries with gendered employment structures such as Türkiye. The factors underlying the high gender gap in labour force participation and employment rates in Türkiye have long been discussed in the literature (İlkkaracan Reference İlkkaracan2012; Kongar and Memiş Reference Kongar, Memiş, Connelly and Kongar2017; Toksöz Reference Toksöz2011; Toksöz and Memiş Reference Toksöz and Memiş2018). The gender pay gap not only sheds light on these gaps as an outcome indicator but also helps policymakers understand where the problems are deeper. Thus, measuring the gender pay gap is particularly important for sound country-specific policymaking.

Despite more than half a century of international conventions, national laws, and regulations guaranteeing women’s equal and full participation in the labour market, it is still not possible to achieve equal participation or equal pay. The International Labour Organization (ILO) Equal Remuneration Convention 1951 (No. 100), which was ratified in 1967 by Türkiye, mandates equal remuneration and social rights for work of equal value, regardless of gender. The convention establishes the principle of equal remuneration for men and women workers for work of equal value. Similarly, Türkiye also ratified the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1985, which obligates states to ensure equal remuneration and treatment for work of equal value and to eradicate workplace discrimination. Aligned with these international conventions, Article 10 of the Turkish Constitution guarantees equality before the law and mandates state measures to enforce gender equality in practice, while Article 90 affirms the supremacy of international agreements in domestic legal frameworks. The Labour Law No. 4857, particularly Article 5, explicitly prohibits wage discrimination based on sex for equivalent or comparable work. On a global scale, the elimination of the gender wage gap is also central to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8, which aims to ‘promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all by 2030’. Specifically, target 8.5 emphasises achieving equal pay for work of equal value.

Theoretical approaches to understanding the gender pay wage emphasise multiple institutional and structural factors, including social norms, workplace discrimination, and similar systemic issues. On the one hand, according to the neoclassical approach to income distribution and wage determination, the gender wage gap is attributed to the fact that women receive lower wages than men because of their lower levels of education, less experience, or fewer job-related skills (Blau and Khan Reference Blau and Kahn2017; Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer Reference Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer2007). Women’s lower education levels or experience, on the other hand, are often explained by unequal time spent on childcare, as termed in the motherhood penalty (Budig and England Reference Budig and England2001), household chores, and unpaid care work, which limits their ability to invest in education and work experience. Critiques emphasise how societal norms act as barriers against equal participation and equal pay in the market. Gender-based wage inequalities in science and engineering fields, with fewer women occupying high-paying positions, provide evidence for this. Further debates emphasise the gender wage gap as an outcome of the employers’ propensity to discriminate, presuming that women have lower productivity (Budig and England Reference Budig and England2001). Although the theory of employer discrimination expects discrimination to be eliminated over time by market competition (Becker Reference Becker1957), the persistence of the gender wage gap indicates the need for alternative theoretical explanations. On the one hand, the compensating wage differentials (Goldin Reference Goldin2014) at high-paying professions, gender inequalities in work hours, differences in career interruptions (Bertrand et al Reference Bertrand, Goldin and Katz2010), limitations on weekly hours worked due to societal norms, and dual labour market approach (Karamessini and Ioakimoglou Reference Karamessini and Ioakimoglou2007), as well as gender segregation by occupation and sector result in lower wages, and job insecurity are the main reasons for women’s concentration in the informal sector (Blau and Khan Reference Blau and Kahn2017; England Reference England1984; Levanon et al Reference Levanon, England and Allison2009).

On the other hand, gender theories underline the structural and institutional factors, including asymmetric unpaid workload of women (Hersch and Stratton Reference Hersch and Stratton2002), occupational segregation, and devaluing of women’s work (England Reference England2010, Reference England2018; Power et al Reference Power, Mutari and Figart2003). In line with these approaches, alternative empirical measurements based on different data sources came along to better understand the gender wage gap (Power et al Reference Power, Mutari and Figart2003). In analysing the gender pay gap, the underlying measurable factors provide important insights. Nevertheless, any method or magnitude of measurement is important in drawing attention to the fact that discrimination is unacceptable. It is a fundamental right for all workers not to be discriminated against based on gender. The persistence of the gender wage gap, even between individuals of the same age group, education level, and occupation, requires a better understanding of the underlying sources with alternative data or measurements when available.

The more commonly used data sources for measuring the gender pay gap come from sample surveys and survey research at the household or firm level. Labour force surveys or income and earnings survey data are the main data sources used for estimation. Since there is no international standardisation in the measurement of the gender wage gap, alternative data sources are used, with differences in scope and variable definitions across countries. However, the choice of data sources becomes critical as surveys conducted for purposes other than gender pay gap research are susceptible to gender bias, as their sample coverage excludes sectors that usually coincide with sectors where female labour is concentrated, as their coverage is limited to sectors other than formal full-time employment/urban/agriculture. Differences in measurement results in the same country are also important because different survey sample information is often incomplete and less known in practice, making it difficult to understand when alternative data sources are used to provide evidence (ILO and TurkStat 2020). So far, only a few studies have been conducted using the full country-level administrative dataset. Among these, Foster et al (Reference Foster, Murray-Close, Landivar and deWolf2020) use a dataset of approximately 1,914,000 people in the US, including 864,000 women and 1,050,000 men. Böheim and Gust (Reference Böheim and Gust2021) provide measures for Australia using administrative data from the Austrian Social Security Database (ASSD), which includes 23,085 firm-year observations between 2009 and 2017.

In this context, we aim to analyse the gender wage gap in Türkiye using a comprehensive dataset compiled for the first time from all individuals registered in the social security system and working full-time between 2013 and 2022. Data is constructed by aggregating 1.5 billion rows of data from 37.4 million unique individuals and transforming it into a 10-year panel dataset. To the best of our knowledge, there are only a limited number of studies on the gender wage gap that employ panel data analysis. Rather, many studies typically use survey data collected by statistical offices, which is then converted into pooled data or pseudo-panel datasets. However, no study has been identified that utilises administrative records or actual individual-level data. Given the lack of gender wage gap estimates using panel administrative data analysis, both in Türkiye and internationally, we believe that this study holds the potential to provide an innovative contribution to the measurement of the gender pay gap.

The introduction is followed by a background section that reviews previous empirical findings. This is followed by a section on data preparation and the methodology used to analyse and estimate the gender wage gap in Türkiye for the period 2013–2022. The data compiled are analysed using panel estimation techniques. Finally, the results are discussed in the context of the existing literature, followed by conclusions and policy recommendations.

Background

The measurement of the gender wage gap is based on data from the Structure of Earnings Survey (SES), which is used as the designated official measure in Türkiye and has a high potential to understate the existing gap, given the labour market structure in Türkiye. In January 2020, a formal cooperation protocol was signed between the ILO Türkiye Office and Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) to develop a more robust framework for measuring and presenting the gender pay gap in Turkey using alternative data sources. A joint working group consisting of experts from the TurkStat and the ILO Turkey Office provided information on how alternative measures based on alternative data sources result in different measures of the gender pay gap in Türkiye when a broader sectoral coverage, including the informal sector, allows for the analysis of the gender pay gap across subgroups defined by education, age, economic activity, and occupational category. The estimates obtained for 2018 using three different data sources indicated gender wage gaps of 7.7%, 9.6%, and 15.6%, with the differences attributable to data scope (ILO and TurkStat 2020). The average gap had decreased to 6.2% by 2022; however, when calculated based on annual gross earnings, the gap ranged between 14.5% and 19.6% by education level, varying across sectors and occupations (TurkStat 2023). The earnings structure surveys conducted in 2018 (based on surveys) and in 2022 (using administrative records) enable a comparative analysis of gender wage gap estimates. The consistency of results across both sources lends support to the existence of a structural gender wage gap in the labour market.

Previous research on the measurement of the gender wage gap can be categorised into two strands. The first consists of reports published by official institutions, which provide general insights based on studies conducted across various countries. The second encompasses academic research, which typically delves into specific determinants of the gender wage gap and its manifestation in specialised groups. Both types of studies consistently demonstrate that women earn less than men at the same level, and contribute to a better understanding of the gender wage gap.

In the European Union, despite women’s employment rates being higher than ever, and despite advancements in regulations, women’s average earnings remain significantly lower than men’s, with cumulative disparities growing throughout their careers. In 2020, the gender wage gap in the EU was 15.7% (European Commission 2020) based on the SES data compiled from 27 countries. Eurostat, decomposing the underlying factors, also provided a synthetic indicator, the ‘gender overall earnings gap’, which measures the impact of three combined factors on the difference in the average earnings of all women of working age –whether employed or not employed – compared to men. Those factors are as follows: the average hourly earnings, the monthly average of the number of hours paid, and the employment rate for men and women. SES coverage of sectors and formal employees may hold a stronger representation of women’s employment in the EU, but it has limitations in countries like Türkiye.

While cross-country reports enable comparison and ranking among countries, each country analysis report provides country-specific factors underlying and driving the gender wage gap, which could be of more interest for policymaking purposes. For example, a pioneer study conducted in the United States (US) presents high wage disparities between white and black workers, as well as between men and women. In 1967, the raw wage gap between white men and women was found to be as high as 45.6%. Occupational segregation was identified then and remained a key factor, with women often occupying lower rungs on the occupational ladder. However, analyses show that women in certain occupations receive larger wage increases, compensating for their underrepresentation in high-status roles. Not surprisingly, additional factors such as education, marital status, and the employment sector also significantly affect wage disparities (Blinder Reference Blinder1973; Oaxaca Reference Oaxaca1973). Publicly available data from the US in 2023 show that only 8% of CEOs were women, with gender being a key determinant for executive appointments. Limited experience among women in managerial roles contributes to this disparity (Xu Reference Xu2024). Similarly, in Portugal, post-2008 financial crisis data indicate that salaries and bonuses for female managers decreased while those for male managers increased (Fernandes and Ferreira Reference Fernandes and Ferreira2021).

In Canada, measures of the gender wage gap based on research using data from the 2016 Canadian Census provide differences in wages between Indigenous peoples and White Canadians and among Indigenous groups, where Indigenous women experience an 11% to 14% wage gap, while only registered First Nations men experience a wage gap of approximately 16% (Taylor Reference Taylor2020). Ethnic minorities in the UK face a ‘double pay penalty’ due to race and gender (Lyonette et al. Reference Lyonette, Baldauf and Behle2010). In Australia, an analysis of earnings data confirms a persistent gender wage gap. Data from the Average Weekly Earnings Survey shows the gap increased slightly between 15% and 17% from 1990 to 2009. Gender discrimination accounts for 60% of the gap, with other factors including sectoral differences, experience, and the underrepresentation of women in large companies (Cassells et al Reference Cassells, Vidyattama, Miranti and McNamara2009). In Brazil, women earned roughly three-quarters of men’s wages in 2016, with the gap widening at higher education levels. Women with university or higher education earned only 63.4% of men’s wages at equivalent levels (IBGE 2018). The United Kingdom’s Office for National Statistics reported that the gender wage gap for full-time employees in 2019 was 8.9%, decreasing compared to its level (12.2%) in 2009. Notably, the gap is near zero among those under 40 years of age, while exceeding 10% for those over 40, partly because older women are more likely to work in lower-paid jobs and less likely to hold managerial or senior public service roles compared to younger women (ONS 2019). In Germany, the gender wage gap in 2004 was influenced by factors such as years of education, potential labour market experience, number of children, marital status, employment type (part-time/full-time), migration status, and residency in East Germany (Bauer and Sinning Reference Bauer and Sinning2005). Studies in the UK, Finland, and France highlight that gender bias in task allocation contributes significantly to wage disparities, with occupational discrimination and public spending on families playing pivotal roles (Elass Reference Elass2024). In Spain, the gender wage gap among managers was 9.4% in 2020. Analysis of reports submitted to the Spanish Securities and Exchange Commission from 2012 to 2021 indicates significant wage disparities between male and female board members in publicly traded companies, attributed to institutional cultures favouring lower wages for women (Garcia et al Reference Garcia, Herrero and Vila2024).

In Türkiye, a previous analysis of the 2010 Household Labor Force Survey found no significant wage disparities when categorical variables such as age, tenure, and education were converted into continuous variables and controlled for (Cergibozan and Özcan Reference Cergibozan and Özcan2012). In a study conducted using the same survey data for the period 2002–2019, it was found that although women had, on average, more favourable individual characteristics than men, men still earned higher average wages. While the overall gender wage gap in the labour market appeared to be relatively low, individual characteristics – particularly occupation and sector – had a substantial impact on the wage gap. Variables such as age, tenure, and education had a significant positive effect on wages. Marital status, however, was found to widen the gender wage gap, with marriage leading to a considerable increase in men’s wages (Koral and Mercan Reference Koral and Mercan2021). However, a 2018 study of job postings, including variables such as wages, gender, region, sector, occupation, age, and education, found a 0.18% gender wage gap. Regional analysis showed higher average wages for men in job postings, although the gap was lower in the construction sector compared to others. Across all educational groups, women received lower average wage offers than men (Halaçlı and Karaalp Orhan Reference Halaçlı and Karaalp Orhan2022). Although the gender wage gap in Türkiye was approximately 3% in 2006, wage distributions reveal a wide range of variation. At the median, men earned 6.47% more than women; however, there were also observations in which women earned 4.99% more than men. When controlling for key variables such as age, education, and tenure, the gender wage gap tends to increase (Aktaş and Uysal Reference Aktas and Uysal2012). Between 2004 and 2016, the wages of informal workers were considerably lower than those of formal employees. Moreover, the wage gap among informal workers was wider compared to their formal counterparts. While the wage gap narrowed in sectors with higher female employment, it widened significantly in male-dominated and high-production sectors, to the advantage of men (Toksöz and Memiş Reference Toksöz and Memiş2020). Over the past few decades, Türkiye has introduced policies that support women’s participation in the workforce. However, women continue to face gender discrimination in the labour market. Women in Türkiye work in a range of job categories that require elementary skills and lower-level occupations (so-called ‘women’s jobs’), further reinforcing their subordinate position in the labour market (Yücel Reference Yücel2015). The gender wage gap tends to decline when male labour force participation is low. Although inter-sectoral differences in the gender wage gap are relatively limited, wage disparities generally favour men. Nonetheless, there are sectors in which women earn higher average wages than men. In labour-intensive sectors such as heavy metal industries and mining, women are more likely to be employed in white-collar positions while men are concentrated in blue-collar roles – an occupational distribution that contributes to narrowing the gender wage gap in favour of women. Conversely, in sectors such as education, health, and finance – where the number of male and female white-collar workers is relatively balanced – the gender wage gap tends to widen in favour of men (Mercan and Karakaş Reference Mercan and Karakaş2015).

Overall, occupational segregation and discrimination in hiring and promotion practices, the motherhood penalty, including unequal distribution of unpaid care work that limits women’s participation in the labour market and leads to career breaks, emerge as common underlying factors across countries. While in high-income countries, labour market segregation is more influential, in mid- and low-income countries, wage gaps are often underestimated due to high informal work. For instance, in Sub-Saharan Africa, women dominate informal agriculture yet earn significantly less due to limited market access and bargaining power (de Pryck and Termine Reference de Pryck, Termine, Quisumbing, Meinzen-Dick, Raney, Croppenstedt, Behrman and Peterman2014; Kabeer Reference Kabeer2021).

Among the more limited number of studies, panel data analyses of the gender wage gap from 1980 to 2010 reveal that the gap narrows over time but remains significant in upper wage distributions in the US. Occupational and sectoral variables, as well as gender roles and labour division, continue to influence the gap. Emerging variables such as cognitive and non-cognitive skills, although less impactful than traditional factors, are gaining importance in explaining wage disparities (Blau and Kahn Reference Blau and Kahn2017). In the US, the gender wage gap widens during GDP growth periods and narrows during high unemployment periods (Finio Reference Finio2010). Similarly, data from 16 OECD countries (2000–2012) suggest that economic growth exacerbates wage inequality between men and women, while increased female labour force participation helps narrow the gap (Dursun Reference Dursun2015). In China, data from the China Family Panel Studies show that motherhood leads to lifelong income loss for women, with the magnitude varying by the education levels of both spouses (Cheng and Zhou Reference Cheng and Zhou2024).

Data and methodology

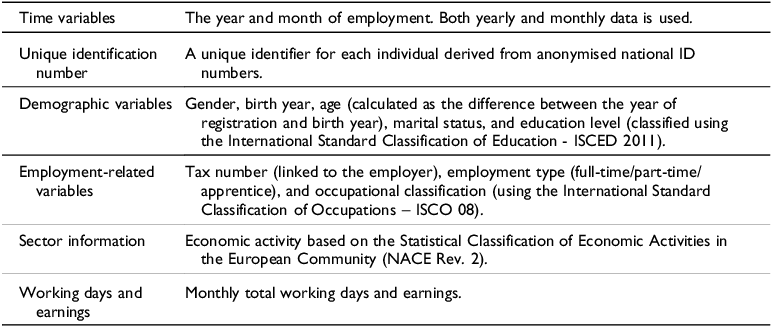

The dataFootnote 1 used in this study, in which two different datasets are combined and harmonised at the individual level for the first time for Türkiye, come from administrative records kept by the Turkish Statistical Institute. The main data source corresponds to these records obtained from the Social Security Institution (SSI) and the Revenue Administration (RA). Employers in Türkiye are legally obliged to report data on their employees to both institutions monthly. Information on the full extent of formal employment is only available in this dataset, which consists of SSI and RA records. Variables include the gender, occupation, type of employment (full-time/part-time/apprentice), number of working days, and earnings of employees, as well as the employer’s tax identification number and comprehensive information on the sector of activity. However, registered workers’ demographic variables, such as age, education level, and marital status, are unavailable. We used the Population dataset that the General Directorate of Population and Citizenship Affairs collected to obtain demographic information and regularly transmitted it to TurkStat. Variables such as gender, age, marital status, education, occupation, sector, number of working days, and earnings were aggregated while ensuring no personal identifiers were included. The variables used in calculating the gender wage gap are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. List of variables included measurement

The raw dataset spans 2013–2022 and contains 1.49 billion rows of data for 37.4 million unique individuals. After filtering for the following criteria (full-time employment, non-apprentice positions, age 15–64, and exclusion of certain sectors and occupations), the dataset was reduced to 563.5 million rows of data for 14 million unique individuals. We confirm that this is the first administrative dataset of this size available at the national level for officially registered workers in Türkiye. To the best of our knowledge, the novelty of using such a large dataset to analyse the gender pay gap is also valid in the international literature.

In the data processing phase, data cleaning was performed first. For individuals who worked in more than one workplace in the same month, only the record corresponding to their primary job was kept. Primary job is defined as the job with the highest earnings or, in the case of equal earnings, the one with the highest number of working days is selected. Records with less than 30 working days per month were excluded from the final dataset. Among the excluded were also the apprentices, interns, agricultural sector, and military personnel records. We restricted the sample by working age, limiting records to the 15–64 age group. In addition, sectors included cover between B-S coding according to Nace Rev2 classification, except for the O-sector (public administration and defence; compulsory social security). Finally, we excluded records for occupation codes above ‘96’ (Refuse Workers and Other Elementary Workers) under ISCO-08.

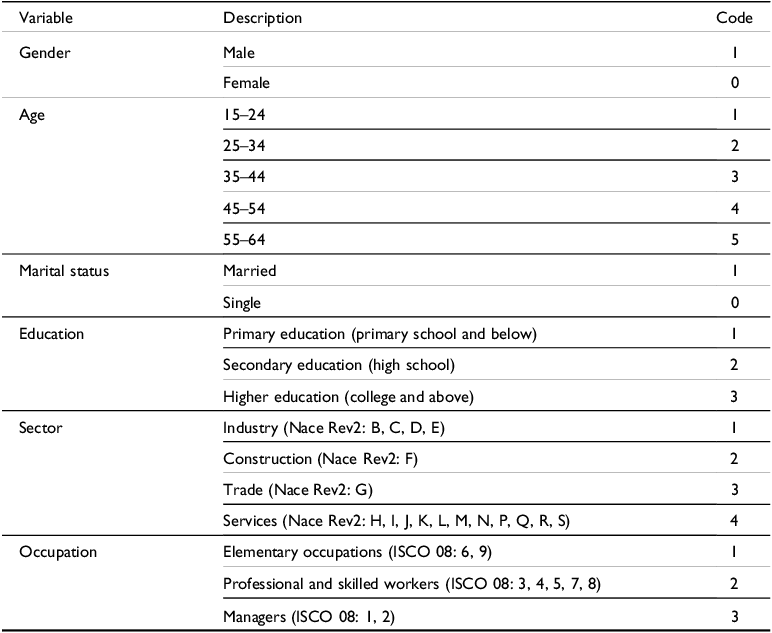

In the second step, the individual attributes were grouped based on age groups, education categories, and occupational classification. All were grouped into categorical variables hierarchically to maintain logical continuity. Gender and marital status variables are constructed as dummies (1/0) (Table 2). In the end, the resulting dataset we get has become a balanced dataset across subgroups, ready for our analysis of the gender wage differences.

Table 2. Overview of the explanatory variables

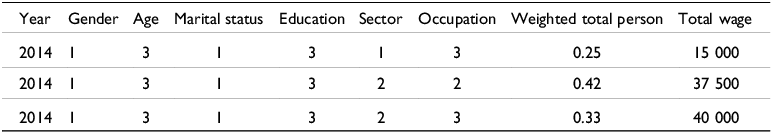

All data checks are also done after preparing the final dataset. For the individuals included in the analysis, variables such as age, marital status, and education level take the same value within the same year. However, individuals can work in multiple sectors or occupations within the same year. After deduplication of the raw data, a single row was created for each person for each month. Since an individual may change sectors or occupations during the year, and have multiple recordings in the data even in the same year, a weight value of 1/12 was assigned for each month worked, and the weighted number of individuals in the relevant group was calculated by multiplying the number of months worked by the weighted value where the sum of the weighted number of individuals for each person equals 1. At the end of this process, the annual total number of individuals in the sector and occupations may be a rational number. However, since the total weight of each individual in the year is 1, it does not cause any disparity. Wages for individuals are calculated as the total wages of the total working months for each sector or occupation. Depending on the number of months employed, the weighted sum of average wages is calculated for each individual. For example, the yearly wage level for a 40-year-old male with a master’s degree, married, who worked for 3 months in sector C as a manager with a salary of 5 thousand TL, for 5 months in sector F as a civil engineer with a salary of 7.5 thousand TL, and for 4 months in sector F as a manager with a salary of 10 thousand TL in 2014, is calculated as shown below (Table 3).

Table 3. The variables assigned to an individual using weights (example)

Subgroups for which information was not available for both genders were excluded from the analysis, as they did not allow for the measurement of the gender pay gap. In addition, subgroups that were completely disaggregated by gender were also excluded from the analysis. This way, a balanced panel dataset was obtained to analyse the impact of variables such as age, marital status, education, sector, relative share of women in the subgroup, and occupation on the gender pay gap. In the next step, the gender wage gap is calculated as the wage gap between male and female employees with the same characteristics divided into i groups as formulated in Equation 1:

Here, GWG represents the gender wage gap in group i,

![]() $A{W_{mi}}$

denotes the average wage of men in subgroup i, while

$A{W_{mi}}$

denotes the average wage of men in subgroup i, while

![]() $A{W_{fi}}$

denotes the average wage level of women in subgroup i. After calculating the gender wage gap for each, the variables used in the estimation are constructed. The dataset consists of a balanced panel set of 360 subgroups using 10 years of data.

$A{W_{fi}}$

denotes the average wage level of women in subgroup i. After calculating the gender wage gap for each, the variables used in the estimation are constructed. The dataset consists of a balanced panel set of 360 subgroups using 10 years of data.

We estimated the following equation in the third stage to analyse associations between each attribute and the gender wage gap, controlling for other factors and women’s relative ratio, which is formalised as:

Among the variables in Equation 2, ED stands for education level, MS for marital status, OCC for occupation, SEC for sector of employment, AGE for the age group, WR the ratio of women relative to men in the corresponding subgroup i = 1, 2, …, 360 represents each subgroup, t = 1, 2, …, 10 represents the periods, and ε represents the error term. The GWG variable stands for the percentage gap calculated as in Equation 1.

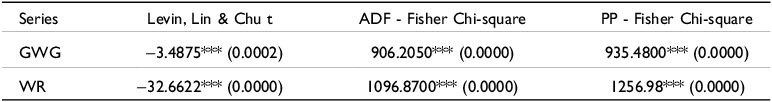

In the first step of the empirical analysis, stationarity tests were conducted to avoid spurious regression. Since the educational level, marital status, occupations, age groups, and sector variables are hierarchical and dummy variables, stationarity tests were also conducted for the GWG and WR variables. The test results are presented in the table below (Table 4).

Table 4. Conventional panel-based unit root tests

Note. *, **, and *** indicate significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. GWG includes no exogenous variable, but WS includes individual effects and individual linear trends. Probabilities for Fisher tests are computed using an asymptotic Chi-square distribution. All other tests assume asymptotic normality.

Empirical results

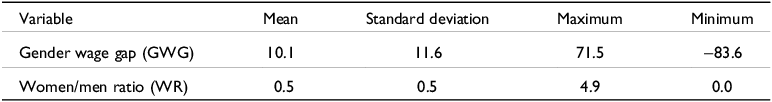

The gender wage gap was calculated using the annual wages of full-year employees between 2013 and 2022. Panel data analyses were conducted to explain the components of the gender wage gap. The long-term effects of age, education, marital status, occupation, and the sector of employment on the gender wage gap were demonstrated. Descriptive statistics are shown in the table below (Table 5).

Table 5. Descriptive statistics

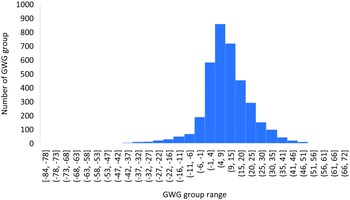

Final data includes 360 groups and 10 years, resulting in 3600 observations. All variables meet the conditions for normal distribution. From 2013 to 2022, the average gender wage gap across years and subgroups is 10.1%. Full-year and registered male employees earn, on average, 10.1% more than female employees. Similar to the findings of Aktaş and Uysal (Reference Aktas and Uysal2012), the gender wage gap varies across education, marital status, occupation, sector, and age groups. The maximum gender wage gap in favour of men is 71.5%, while the minimum gender wage gap in favour of women is 83.6%. The maximum gender wage gap represents the group of singles between the ages of 55 and 64 with a primary education degree, who work in the construction sector as a manager for men, while it represents the group of married women between the ages of 15 and 24 with a primary education degree, who work in the construction sector as a manager (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of gender wage gaps.

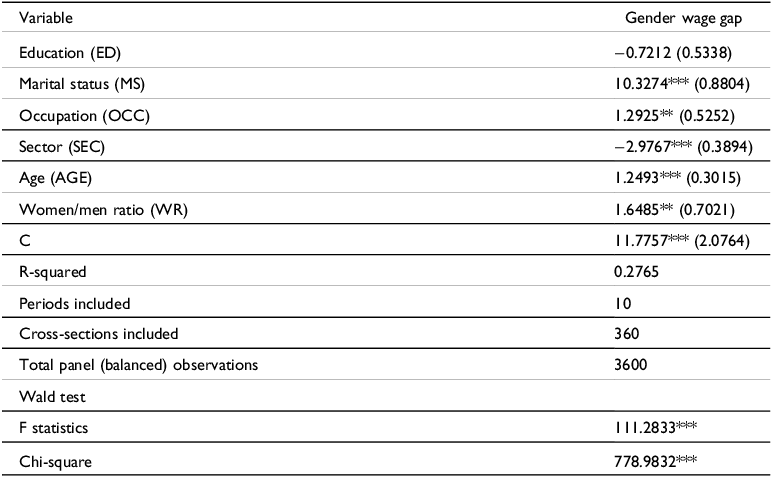

Depending on the effect of the error terms on the model, two alternative panel data estimations can be implemented in the analysis: fixed effects and random effects estimation techniques. Given variable types as hierarchical variables (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) or dummy (1, 0) variables, the estimations were performed using the random effects model. The results of the panel data analysis are shown in the table below (Table 6).

Table 6. Panel analysis with random effects

Note. *, ** and *** indicate significance at 10%, 5% and 1% levels respectively.

The weighted R-squared value, which indicates the explanatory power of the model, is 0.06, while the unweighted R-squared value is 0.28. Estimation results present that all variables, except for the education variable, provide significant results. The significance of the independent variables in explaining the dependent variable was analysed using the Wald Test. The results are shown in the table below.

This study makes a significant contribution to data selection in the gender wage gap literature. While previous research based on survey data – such as Cergibozan and Özcan (Reference Cergibozan and Özcan2012), Koral and Mercan (Reference Koral and Mercan2021), Halaçlı and Karaalp Orhan (Reference Halaçlı and Karaalp Orhan2022), and Aktaş and Uysal (Reference Aktas and Uysal2012) – has generally found relatively low levels of the gender wage gap, this study reveals a GWG of 10.1% over a ten-year period. These findings highlight the discrepancies between survey data and administrative records. Moreover, unlike earlier studies, panel data results from this study show that education level does not have a statistically significant effect on the GWG. The use of big data and long-term analysis provides a pioneering contribution to the academic literature. Future research utilising administrative data is expected to offer new insights into wage differences in the labour market.

Accordingly, the association between the educational level and the gender wage gap is not statistically significant, which is a result supported by the summary earnings gap statistics provided by TurkStat (2023). No matter what the education level is, the gender wage gap persists as other gender-based structural factors dominate. Many studies in the literature that analyse the issue at the individual level argue that there is a significant relationship between education and the gender wage gap. Blau and Kahn (Reference Blau and Kahn2017) present the role of education in reducing the wage gap, yet nevertheless, they argue that significant wage disparities remain as the education level increases. They emphasise that even among highly educated individuals, factors like occupational segregation and discrimination contribute to persistent wage differences. An increasing number of studies demonstrate that despite the increasing presence of women in sectors and occupations dominated by highly educated employees, the gender wage gap persists. Mercan and Karakaş (Reference Mercan and Karakaş2015) argue that in Türkiye, education has a more positive impact on men’s wages compared to women’s.

Bertrand et al (Reference Bertrand, Goldin and Katz2010) demonstrated that while the earnings of male and female MBA graduates are nearly identical at the start of their careers, they quickly diverge thereafter. Similarly, Xu (Reference Xu2015) found that men’s and women’s earnings begin to diverge significantly within the first ten years of their careers, with female STEM (science, technology, engineering, and maths) graduates experiencing a particularly pronounced wage disadvantage. Despite women’s overall advantage in earning bachelor’s degrees (DiPrete and Buchmann Reference DiPrete and Buchmann2013), significant and enduring gender differences in fields of study persist (Bayer and Wilcox Reference Bayer and Wilcox2019; Charles and Bradley Reference Charles and Bradley2009). Studies have demonstrated that wage differences between fields of study can be as large as the average gap between high school and bachelor’s degree earnings (Kim et al Reference Kim, Tamborini and Sakamoto2015; Webber Reference Webber2016) and that gender-based differences in college majors have significantly contributed to the overall gender wage gap. As in the case of Türkiye, education level plays an important role, particularly in women’s labour force participation, professional development, social development, and their role in the household in Türkiye. However, as our results also present, education level may neither have a significant long-term effect nor affect variations across subgroups in terms of the gender wage gap.

Regarding the association between marital status and the gender wage gap, controlling for other factors, there is much evidence showing that marital status may influence wage levels for both women and men significantly differently. Our results here indicate that marital status has a significant and highly positive effect on the gender wage gap, which is highly dominant. We observe that the gender wage gap between single women and men increases significantly after marriage. These results support the widespread literature and gender-based norms. The breadwinner single-earner family model as a social norm leads to perceptions such as ‘men deserve higher wages after marriage’, which has been explored and discussed in Türkiye previously. In practice, a higher wage premium for married men compared to their single counterparts is considered socially acceptable (Gemicioğlu and Memiş Reference Gemicioğlu and Memiş2024). Women, on the other hand, undertake asymmetrically household chores and care for their children in married-couple households (Kongar and Memiş Reference Kongar, Memiş, Connelly and Kongar2017). Additionally, it is thought that women are more likely to take a career break or temporarily leave their jobs due to pregnancy and rising care burdens. This situation marks the beginning of the glass ceiling effect for married women. The increased potential for women to leave their jobs leads to limited wage increases and relegation in professional development.

Professional development has a significant and positive effect on the gender wage gap. The gender wage gap is lower in unskilled jobs but higher in skilled jobs and among managers. These results are supported by many studies in the literature. The increase in the gender wage gap due to professional development is based on two main reasons. First, in unskilled jobs, general wage levels are low. Regardless of gender, many employees earn minimum wage or slightly above it, which keeps the gender wage gap low. However, in skilled jobs, wage differentiation is higher, which allows men to earn more. The second reason is discrimination, which women face in both skilled jobs and among managers. Despite women’s advances in their careers, they face lower wage increases compared to men. Chen and Xu (Reference Chen and Xu2024) identify a lack of experience as one of the causes of discrimination. However, the widespread literature proves that women are subjected to the glass ceiling effect in both career development and wage levels.

Furthermore, our results show that the gender wage gap decreases when transitioning from the industrial sector to the services sector. While there is no hierarchical relationship between the sectors, on the one hand, we observe that, especially in the service sectors, women earn higher wages, and in some sub-sectors (such as transportation and storage, real estate activities), the gender wage gap favours women (TurkStat 2023). On the other hand, the high level of the gender wage gap in favour of men, particularly in the manufacturing sector, needs a more disaggregated level of exploration. Toksöz and Memiş (Reference Toksöz and Memiş2020) state that as production levels increase, the gender wage gap tends to widen in favour of men. Similarly, Şentürk and Demir (Reference Şentürk and Demir2022) and Solum (Reference Solum2022) note that employment in the manufacturing sector poses disadvantages for women, including barriers to hiring, long working hours, and lower wages. In contrast, the relative wage advantage of women in service sectors is largely attributed to their greater representation in qualified positions – such as those in the aviation industry – compared to men. Regarding the association of age groups with the gender wage gap, we observe that the gender wage gap increases significantly with age. This increase is consistent with the widespread literature. Britton et al (Reference Britton, Dearden and Waltmann2021), revealed that in the UK, by the age of 30, the gender pay gap widens substantially, despite their work field. Many studies have presented that while the age-wage relationship is linear for men, no such linear relationship exists for women (Cheng and Zhou Reference Cheng and Zhou2024; Halaçlı and Karaalp Orhan Reference Halaçlı and Karaalp Orhan2022; ILO and TurkStat 2020; ONS 2019). Gender discrimination should not only be considered as a function of age-related gender wage gaps. The glass ceiling effect faced by women in later years of working life also contributes to these results.

Women’s representation has a significant and positive effect on the gender wage gap. Consistent with the broader literature, the findings confirm that women tend to enter the labour market at lower wage levels than men. Equally important, the average ratio of women’s employment relative to men’s is 54%, indicating that women’s participation is roughly half that of men. Employment policies in Türkiye remain inadequate in addressing the structural barriers women face in the labour market (Yücel Reference Yücel2015). Employment segregation is one of the primary factors contributing to the gender wage gap around the world (Carranza et al Reference Carranza, Das and Kotikula2023). Past experiences prove that eliminating gender-based specialisation requires a new way of thinking about men’s and women’s jobs, both in the academic and business worlds. However, gender roles begin at a very young age in families, in nurseries, and in many social settings (Anker et al Reference Anker, Melkas and Korten2003). Women’s labour force participation is low due to reasons such as household production, long working hours, and motherhood earning penalty (Nwaka et al Reference Nwaka, Lisaniler and Tuna2016). İlkkaracan and Selim (Reference İlkkaracan and Selim2007) state that, in Türkiye, lower working experience of women stems from the responsibilities such as childcare, household work, and lack of affordable quality childcare facilities. This concludes with women withdrawing from the labour force upon birth and returning to work once children have reached school age.

Concluding remarks

The gender wage gap remains a critical measure of persistent gender inequalities in labour markets worldwide, reflecting the complex interplay of economic, structural, and societal factors. Despite the long existence of international conventions, national legislation, and policy frameworks aimed at achieving equal pay, the goal remains unfulfilled. This persistent gap underscores the need for more nuanced approaches to understanding its root causes and measuring its magnitude with precision.

This study highlights the importance of using comprehensive, country-specific datasets to explore the gender wage gap. By leveraging an extensive panel dataset from the social security system, spanning over a decade and encompassing millions of individual records, this research advances the empirical examination of wage differences in a way that surpasses traditional survey-based methods in Türkiye. In doing so, it not only provides more robust evidence of the enduring gender wage gap but also opens avenues for more accurate policy targeting. Between 2013 and 2022, the gender wage gap was analysed for approximately 14 million full-year employees in Türkiye, using 360 observation groups and 10 years of panel data. The main summary finding of the empirical analysis here shows that the average gender wage gap stood at 10.1% over the corresponding period. Although this rate appears relatively low compared to other countries, it proves the existence and persistence of a gender-based wage gap among all formally employed full-time and registered in the social security system administrative data. Therefore, further work is needed to rethink the economic and social policies to address this issue.

Furthermore, the findings reaffirm the significance of marital status, occupation, sector, and age by gender, and gender-based social norms in shaping the wage gap. They also emphasise the limitations of existing data sources and methodologies, which often fail to capture the full scope of gender-based differences. Marital status, occupation, and age are significant factors contributing to the increase in the gender wage gap, with marital status having the most substantial impact. The findings indicate that married women experience wage differences in the labour market. Additionally, the decrease in GWG observed as individuals transition from industrial to service sectors serves as a crucial indicator of labour market dynamics. The education variable, contrary to existing literature, lacks statistical significance. This insignificance may be attributed to the exclusion of unregistered wages and informal employment, which could explain the discrepancies with prior studies. Moreover, many studies in the literature have limitations in terms of time and sample size. As such, the role of education may not be accurately reflected in its impact on GWG in Türkiye. Further research is warranted to explore the relationship between educational attainment and GWG.

The results underscore the urgent need for alternative measurement approaches that can account for the nuances of informal employment, sectoral differences, and the broader labour market dynamics where women are disproportionately affected. Despite the increasing presence of women in the labour market, the gender wage gap persists and remains at high levels even in dynamic sectors of high technology. We believe our findings contribute to the research arguing for the great importance of policies to be developed worldwide. There are studies in the literature showing that an increase in the number of women in the labour market positively affects GDP growth. However, this effect should not be evaluated solely in terms of economic growth but also from a human rights perspective for ethical and social purposes.