Introduction

Institutional trust refers to citizens’ confidence that public institutions will operate effectively (Hudson, Reference Hudson2006). Public institutions include representative institutions (Parliament, central government) and institutions that provide public policies (the legal system and administrative branches) (Rothstein and Stolle, Reference Rothstein and Stolle2008). Institutional trust can be considered an important resource for economic performance (Knack and Keefer, Reference Knack and Keefer1997; Leblang et al., Reference Leblang, Smith and Wesselbaum2022), contribution to public goods (Anderson, Reference Anderson2017; Marien and Hooghe, Reference Marien and Hooghe2011), development of a democratic system (Newton, Reference Newton2001), and social cohesion (Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Herrera, Morelli and Sonno2024). Literature has proposed two theoretical approaches to the roots of institutional trust (Kaasa and Andriani, Reference Kaasa and Andriani2022). The cultural approach comes from the field of political culture and focuses on social capital.Footnote 1 A dense network of voluntary associations generates social trust, reciprocity, and cooperation among citizens, as well as a high level of civic engagement. The link between social trust and institutional trust is particularly important, with social trust that ‘spills up’ to trust in public institutions (Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti1993). A second approach explains the foundation of institutional trust in terms of political economy, focusing on the principles of rational choice. According to this institutional approach, institutional trust is the positive response of citizens to their perceptions of, and expectations about, institutional performance (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004). Institutional trust is therefore embedded in the performance of public institutions. Institutions performing well from an economic and political point of view generate institutional trust. Poorly performing institutions inspire scepticism and distrust (Džunić et al., Reference Džunić, Golubović and Marinković2020; Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001).

In this paper, by adopting the institutional approach, we analyse whether a policy implemented in Italy to fight organised crime has affected citizens’ trust in institutions. The Italian government has developed highly effective law enforcement tools against organised crime. The strategy can be separated into two distinct phases. The first involves the identification, seizure, and confiscation of the wealth of mafia-type associations. Wealth includes current assets (money and jewellery), documented current assets (cars, boats, and airplanes), non-current assets in the form of real estate (villas, apartments, agricultural buildings, commercial buildings, and land), and companies (shares in companies, factories, industrial plants, and commercial activities). The second phase involves the allocation of confiscated real estate for social and institutional purposes. The primary aim of Italian policy is to weaken the financial capacity of mafia organisations, disrupt their illicit activities, and foster economic development in communities affected by organised crime. Additionally, it seeks to convey a clear message that criminal activity will not be tolerated and that illicit gains will be recovered and redirected for the public benefit.

Our study examines the confiscation of real estate assets from mafia-type organisations and its effects on citizens’ trust in public institutions. This policy conveys a dual message: it demonstrates the State’s capacity to target organised crime through seized wealth (symbolic value), thereby fostering institutional trust, and it transforms confiscated assets into tangible social and economic resources that benefit local communities (economic value).

Using individual-level data from the Italian National Statistical Office (ISTAT)’s Aspects of Daily Life(ADL) survey and regional data from the National Agency for the Administration and Destination of Seized and Confiscated Assets (ANBSC) for 2014–2022, we employ linear and non-linear regressions alongside instrumental variables techniques to assess the impact of confiscations on trust in national Parliament, regional and municipal governments, as well as the legal system.

Our findings reveal marked geographical heterogeneity. On average, confiscations enhance trust in local public institutions, but not in the Parliament and legal system. In Southern regions, characterised by a stronger presence of organised crime and higher confiscation rates, confiscation also increases trust in the Parliament and legal system. In Central and Northern regions, where organised crime is less prevalent, the positive effect is confined to local public institutions, and confiscations reduce trust in the legal system.

This paper contributes to current literature in two main ways. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that considers the relationship between the confiscation of real estate assets from organised crime and institutional trust. It fits with the recent research on anti-mafia policies with economic content. Previous studies have focused on the impact of the confiscation of real estate assets on (i) real estate values (Calamunci et al., Reference Calamunci, Ferrante, Scebba and Torrisi2023), (ii) the value of properties in the proximity of reallocated assets and criminal activity (Boeri et al., Reference Boeri, Di Cataldo and Pietrostefani2024), and (iii) electoral competition (Ferrante et al., Reference Ferrante, Reito, Spagano and Torrisi2021). The confiscation of organised crime companies has also been analysed with respect to (i) ‘legal’ firms that operate in the same market as criminal companies (Calamunci and Drago, Reference Calamunci and Drago2020), (ii) bank–firm relationships (Calamunci et al., Reference Calamunci, De Benedetto and Silipo2021), and (iii) commercial property values (Calamunci et al., Reference Calamunci, Ferrante and Scebba2022). Our study adds to this literature by providing evidence that confiscation may have economic benefits that also indirectly increase citizens’ institutional trust.

Secondly, our work contributes to the literature on the determinants of institutional trust. Some studies have provided evidence that institutional trust is affected by individual characteristics such as gender, marital status, age, education, income, and employment status (Camussi and Mancini, Reference Camussi and Mancini2019; Hudson, Reference Hudson2006; Kaasa and Andriani, Reference Kaasa and Andriani2022). Others have highlighted the relevance of cultural aspects, such as social capital and perceived corruption, as well as institutional performance, such as the quality of local services and governments (Camussi and Mancini, Reference Camussi and Mancini2019; Džunić et al., Reference Džunić, Golubović and Marinković2020; Kaasa and Andriani, Reference Kaasa and Andriani2022), and the role of crime (Blanco, Reference Blanco2013; Campedelli et al., Reference Campedelli, Daniele, Martinangeli and Pinotti2023; Corbacho et al., Reference Corbacho, Philipp and Ruiz-Vega2015; Pazzona, Reference Pazzona2020), income inequality, and economic well-being (Rainer and Siedler, Reference Rainer and Siedler2009). Our findings integrate the institutional approach by highlighting the important role of anti-mafia policies aimed at confiscating criminal real estate assets.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section The confiscation of mafia assets in Italy and the links with institutional trust outlines Italy’s policy on the confiscation of real estate assets from mafia organisations and its relation to institutional trust. Section Data and methodology describes the data and methodology. Section Result presents the empirical findings, and section Discussion and Conclusion discusses the results and draws the conclusions.

The confiscation of mafia assets in Italy and the links with institutional trust

Institutional framework of confiscated real estate mafia assets

The mafia phenomenon is more than a century old (Lupo, Reference Lupo2004).Footnote 2 Mafia-type organisations take over, manage, and control the economic activities of enterprises either directly or indirectly. They also influence the activity of local public administrations (Mirenda et al., Reference Mirenda, Mocetti and Rizzica2022). Their dangerous and pervasive capacity is increased through the use of vast financial resources, accumulated through violence, clandestine trafficking, and other crimes. This stream of ‘dirty money’, destined to expand their unlawful activities and influence the legal economy, is a transnational phenomenon (Palermo, Reference Palermo, Balloni and Sette2020; Sciarrone and Storti, Reference Sciarrone and Storti2014). Mafia-type criminal organisations now control whole territories and communities far beyond their original span. This debunks the thesis of the mafia’s non-exportability (Gambetta, Reference Gambetta1992) due to the dependence on resources and factors embedded in the local environment. Mafia organisations are not the product of a particular mentality or culture, but they are able to develop within any local environment, mainly through the control of territory using violence, and relations with politics and the economy (Catino, Reference Catino2015). Their actions are largely oriented towards the accumulation of material and immaterial goods.

Experience against the mafia in Italy has made it clear that repressive policies managed mainly by public institutions must be combined with preventive (indirect) policies developed in communities to interrupt the ties and networks built by criminal organisations. The basic idea of more effective tools is to strike at the economic strength of mafia-type organisations by removing illegally acquired assets and resources from the criminal organisation’s economic circuit. This takes away both economic wealth and the force required to recruit associates, showing that supporting them guarantees opportunities for wealth. This idea is the basis of the preventive measures adopted in Italy. They were first introduced by the ‘Rognoni–La Torre’ Law 646 of 1982.Footnote 3 Over the years, they have been adapted to overcome difficulties in their application and to streamline and enhance the procedures for confiscating illegal resources. Article 416 was a revolutionary breakthrough in the fight against the mafia since it directly criminalised the organisations themselves. It states, ‘A Mafia-type organisation is an organisation whose members use the power of intimidation deriving from the bonds of membership, the state of subjugation and conspiracy of silence that it engenders to commit offences, to acquire direct or indirect control of economic activities, licences, authorisations, public procurement contracts and services or to obtain unjust profits or advantages for themselves or others, or to prevent or obstruct the free exercise of vote, or to procure votes for themselves or others at elections’. Upon the conviction of an individual associated with a mafia-type organisation, the State, pursuant to Article 416- bis of the Penal Code, acquires possession of assets connected to the offence. This includes not only property directly owned by the convicted individual but also assets under their de facto control, even where nominal ownership lies with relatives, associates, or other intermediaries, reflecting the innovative scope of the confiscation regime.

Strategies to fight organised crime comprise two principal phases. The first concerns the identification, seizure, and confiscation of assets belonging to mafia-type organisations, including current assets (money and jewellery), documented current assets (cars, boats, aeroplanes), non-current assets in the form of real estate (villas, apartments, agricultural buildings, commercial buildings, and land), and companies (shares in companies, factories, industrial plants, and other commercial activities) (Law 646/1982). The second involves the allocation of confiscated real estate for institutional and social purposes (Law 109/1996; Legislative Decree 159/2011).

The size and complexity of confiscated assets led to the establishment of the National Agency for the Administration and Destination of Assets Seized and Confiscated from Organised Crime ANBSC, under Law 50/2010. Operating under the supervision of the Ministry of the Interior, the Agency manages seized and confiscated assets, supports judicial authorities, and oversees their reassignment for public or social use.

The strategic relevance of asset reuse is reaffirmed at European Union (EU) level, notably in Directive 2014/42/EU and, more recently, Directive 2024/1260/EU,Footnote 4 which emphasises the social reuse of confiscated assets as a means of promoting legality, justice, and community resilience against criminal infiltration.

The confiscation and reuse process involves multiple institutional actors, non-profit organisations, and civil society. Parliament establishes the legal framework and allocates resources, while judicial authorities order seizure and confiscation. The ANBSC plays a strategic role in determining asset use, distinguishing between institutional and social purposes. If institutional, local administrative bodies must use the asset as a public good. If social, the assets are used for social purposes either directly by administrative bodies or assigned on free loan to non-profit organisations. Local governments are central to the post-confiscation phase, managing properties, facilitating partnerships with civil society, and transforming confiscated real estate into community assets that support social development and symbolically challenge organised crime.

Confiscated real estate mafia assets and institutional trust

The real estate assets of criminal organisations primarily serve as a prominent symbol of their power. These goods can be compared to the microeconomic category of positional goods (Hirsch, Reference Hirsch1976), that is, goods that confer utility through the status they create, and the position on the social ladder that can be achieved and/or occupied through their ownership and consumption (hence the term ‘positional goods’). These assets contribute to the economic prosperity and utility of the organisation’s members. They also demonstrate to the community that criminal organisations are strong and able to create wealth for both themselves and their affiliates (Mosca and Villani, Reference Mosca and Villani2013; Mosca, Reference Mosca, Sacchetti, Christoforu and Mosca2017).

By removing these assets from criminal organisations’ control, the policy aims to undermine the image of the mafia. It conveys the message that the State can fight organised crime by confiscating wealth accumulated in real estate assets. This strikes the symbolic value of criminal organisations’ dominance and authority over the communities and territories in which they operate. Moreover, the policy also has an economic value. Confiscated real estate assets become public goods that are returned to the population and territories to support social inclusion, employment, democratic participation, and improve the quality of life.

These values could be seen as channels through which the anti-mafia policy designed to confiscate criminal real estate assets builds trust between citizens and public institutions (Parliament, courts, and local governments). This relationship, however, is not automatic, as individuals’ trust in public institutions is shaped by reality, perception, and expectations (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001; Van de Walle and Bouckaert, Reference Van de Walle and Bouckaert2003). Historically, the geographic distribution of organised crime has shown that mafia-type organisations have been more prevalent in the Southern regions of Calabria, Sicily, Campania, and Apulia (Libera, 2021; Mocetti and Rizzica, Reference Mocetti and Rizzica2024; Sciarrone, Reference Sciarrone2014). In these regions, police and legal actions were highly effective, resulting in numerous confiscations of real estate assets. Thanks to Law 109/1996 and subsequent amendments, many real estate assets have been reassigned for social and institutional purposes to non-profit organisations and local governments, especially municipalities. These are now the owners of the confiscated real estate assets (Libera, 2017).

In the Northern and Central regions, the penetration of criminal organisations into society and institutions is a relatively new phenomenon (Catino, Reference Catino2020; Varese, Reference Varese2011). In these areas, the number of confiscated properties has increased over time but remains much lower than in the South (Libera, 2017). Thus, the different presence of criminal organisations across Northern and Southern regions can generate dissimilar perceptions in citizens about the policy of confiscated real estate assets (Libera, 2018). In the South, where the presence of criminal organisations is pervasive, stable, dominant, and well-defined, also due to mafia homicides, the confiscation policy of real estate assets is perceived and expected as a credible tool for fighting organised crime. Thus, reaffirming the rule of law and promoting socio-economic local development through the creation of social activities. Citizens’ trust can increase toward all the institutions involved in the policy. Contrarily, in North and Central Italy, the presence of mafia-type organisations is a recent phenomenon, which is more oriented towards hitting entrepreneurship and finance. The diffusion of the mafia is therefore less violent, less visible, and embedded in the economic and financial structure of the society. The confiscation of real estate assets can therefore be perceived and expected in its economic value. However, the symbolic value can be less important and less perceived. In this case, citizens’ trust could be directed more towards the local government involved in the policy than towards the legal system that should have prevented mafia infiltration.

From the above arguments, we expect that the anti-mafia policy designed to confiscate real estate assets from organised crime increases citizens’ trust in institutions. This link should be stronger in the South than in other areas of Italy.

Data and methodology

To assess the effect of the confiscation of real estate mafia assets on institutional trust, we run an econometric analysis with several measures of trust as dependent variables. This section describes the data, variable construction, and the empirical model.

Data on institutional trust and assets confiscated from mafia organisations

We use two primary data sources to construct our dataset. Information on institutional trust is drawn from the annual ADL survey conducted by ISTAT (ISTAT, 2025). The survey questionnaire collects information about the daily lives of individuals and households. It also provides insights into their habits and issues in various thematic areas, including social, economic, and political aspects of life. The questionnaire provides information on the individuals’ region of residence by using the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS 2). Each year, about 20,000 households and 50,000 individuals are interviewed. Our sample is built by pooling nine waves of the ADL survey from 2014 to 2022. Our measures of institutional trust are based on the questions that ask people how much they trust i) municipal government, ii) regional government, iii) the Italian Parliament, and iv) the legal system. The answers range from 0 (no trust) to 10 (completely trusted). Using these data, we build four variables for institutional trust: trust in municipal government (Trust mun), trust in regional government (Trust reg), trust in the Italian Parliament (Trust parl), and trust in the legal system (Trust leg).

Data on real estate assets confiscated from mafia organisations are provided by the ANBSC. For each confiscated real estate asset, the ANBSC provides the asset type (e.g., apartment, building, or land), the asset address, and the date of confiscation. We aggregate these data at the regional level (NUTS-2 level) to give the number of confiscated real estate assets for the twenty Italian regions in each year between 2014 and 2022. The main explanatory variable of our regression model is the number of confiscated real estate assets per 1,000 inhabitants (Confiscated assets).Footnote 5

Control variables

Consistent with the literature on the determinants of institutional trust, we include two sets of controls: one at the individual level and one at the regional level.

At the individual level, we use the ADL survey from ISTAT and control for demographic and socio-economic characteristics, including gender, age, household members, children, level of education, perceived health status, household economic situation and resources, and employment status. We also built three individual social capital variables: religious participation, Olson groups, and Putnam groups.Footnote 6 Lastly, we use dummies for municipal size. This first set of control variables consists mainly of binary variables.

We consider several regional variables using data from ISTAT and European Statistical Office (EUROSTAT). Gross Domestic Product per capita (GDP pc) accounts for the economic standard of living. Public services measure the quality of local public services which, in line with Camussi and Mancini (Reference Camussi and Mancini2019), is expected to increase citizens’ trust in institutions. Quality of politicians takes into account the ability of politicians, as measured by their educational level. The variable is computed by using data for both municipal and regional elections. Quality of politicians based on municipal elections is included in the regression for trust in municipal government, while Quality of politicians based on regional elections is included in the other regressions. The literature shows that the level of human capital is a good proxy for politicians’ ability and quality (Alfano et al., Reference Alfano, Baraldi and Papagni2020; Fortunato and Panizza, Reference Fortunato and Panizza2015), thereby improving citizens’ trust in public institutions. Inequality in household income is measured using the Gini index computed from households’ disposable income. Crime and Mafia homicides control for possible confounding factors concerning the intensity of criminal activities in the region. Crime accounts for perceptions of insecurity due to widespread criminal activity. It measures the percentage of households in the region perceiving a high risk of crime. Mafia homicides is the number of homicides attributable to mafia organisations, and it is a proxy of the violence exerted by mafia. Lastly, we control for the region’s population size (Population).Footnote 7

Descriptive analysis

The spatial distribution of our four measures of trust is shown in Figure 1. Real estate assets confiscated from mafia organisations are shown in Figure 2. Trust varies considerably across regions. Trust in local governments (municipal and regional) is higher in Northern Italy and in some central regions, such as Tuscany and, to a certain extent, Marche. However, it is low in Southern Italy, especially in Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily. It is notable that trust in the legal system differs markedly: it is higher in the South (Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily) and quite low in some important regions of the North, such as Lombardy, Veneto, and Emilia-Romagna. The picture is mixed for trust in the Italian Parliament, which is more equally distributed across macro-areas. It is high in Liguria, Tuscany, Lazio, Campania, and Apulia, and low in Veneto, Marche, and Sardinia.

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of institutional trust, average values in the period 2014–2022.

Notes: The figure shows the geographic distribution of our measures of institutional trust across Italian regions (NUTS 2-level) throughout the whole period of analysis.

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of real estate assets confiscated from mafia-type organisations, 2014–2022.

Notes: The figure shows the geographic distribution of confiscated assets across Italian regions (NUTS 2-level) throughout the whole period of analysis.

During the period 2014–2022, 12,324 real estate assets were confiscated from mafia-type organisations. Most of them were in Southern Italy: 5,044 in Sicily, 2,012 in Calabria, 2,043 in Campania, and 1,124 in Apulia. Many confiscations, however, were also registered in other macro-areas of Italy, especially in Lombardy (838) and Lazio (586), suggesting that the phenomenon is not limited to the South. The geographic distribution across macro-areas is also mixed for regions with few confiscated real estate assets. There are a few confiscations in Basilicata (19), Molise (3), Friuli (33), or Trentino (2). Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of confiscated real estate assets both in absolute numbers and per 1,000 inhabitants. The two maps are similar and indicate that, although more assets are confiscated in Southern regions, confiscations also occur in some Northern and Central regions.

Individual trust in public institutions is quite low, below the median (5) for all measures of trust. On average, trust is higher in municipal governments (4.75) than in other tiers of government, followed by trust in the legal system (4.45). The lowest trust is in the Italian Parliament (3.94), whereas trust in regional governments is slightly higher (4.02).Footnote 8

Empirical model

The regression model is based on an individual-level dataset comprising repeated cross-sections of the ADL waves from 2014 to 2022. The estimated equation is specified as follows:

where i refers to individuals who responded to the ADL survey questions, r refers to regions, and t stands for the years of the survey waves.

![]() $Trus{t_{i,r,t}}$

is our proxies for institutional trust and

$Trus{t_{i,r,t}}$

is our proxies for institutional trust and

![]() $Confiscated\;asset{s_{r,t}}$

measures confiscation of assets from mafia-type organisations.

$Confiscated\;asset{s_{r,t}}$

measures confiscation of assets from mafia-type organisations.

![]() ${R_{i,r,t}}\;$

is the vector of individual controls taken from the ADL survey and

${R_{i,r,t}}\;$

is the vector of individual controls taken from the ADL survey and

![]() ${X_{r,t}}$

is the vector of regional controls.

${X_{r,t}}$

is the vector of regional controls.

![]() ${\gamma _t}$

is the set of time fixed effects included to control for any shocks common to the whole country in a specific year,

${\gamma _t}$

is the set of time fixed effects included to control for any shocks common to the whole country in a specific year,

![]() ${\mu _r}$

are regional fixed effects that account for unobserved and time- invariant heterogeneity, and

${\mu _r}$

are regional fixed effects that account for unobserved and time- invariant heterogeneity, and

![]() ${\varepsilon _{i,r,t}}$

is the error term. Fixed effects are at the regional level, along with some controls, because the ADL survey provides information on respondents’ regions of residence. The main coefficient of interest is

${\varepsilon _{i,r,t}}$

is the error term. Fixed effects are at the regional level, along with some controls, because the ADL survey provides information on respondents’ regions of residence. The main coefficient of interest is

![]() $\beta $

, which captures the impact of asset confiscation on institutional trust. The regressions run on a maximum of 3,19,476 observations and are estimated by the ordered probit model because the dependent variables are discrete and ordinal.Footnote 9 Their values range from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating greater trust. The maximum likelihood method is used to estimate the model parameters, with standard errors clustered at the regional level.

$\beta $

, which captures the impact of asset confiscation on institutional trust. The regressions run on a maximum of 3,19,476 observations and are estimated by the ordered probit model because the dependent variables are discrete and ordinal.Footnote 9 Their values range from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating greater trust. The maximum likelihood method is used to estimate the model parameters, with standard errors clustered at the regional level.

Results

Baseline results

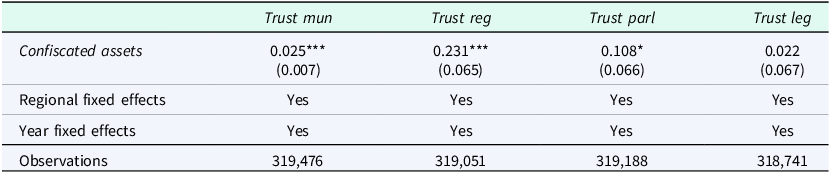

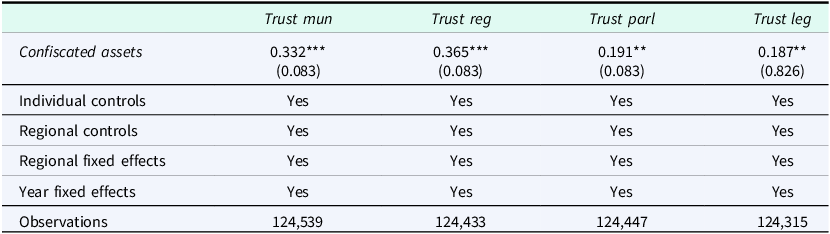

As a first step, we carried out a bivariate regression of institutional trust on confiscated real estate assets, including regional and year-fixed effects. The estimates are shown in Table 1. There is a positive and statistically significant association between trust in the different tiers of national government and confiscated assets. There is also a positive relationship with trust in the legal system, but the coefficient of Confiscated assets is not statistically significant. The impact of asset confiscation is larger on trust in regional government and lower on trust in municipal government.

Table 1. Ordered probit estimates

Notes: Ordered probit estimates are reported with standard errors clustered at the regional level in parentheses. The units of observation are the individuals who responded to the ADL survey in the period 2014–2022. The dependent variables are: trust in the municipal government (Trust mun), trust in the regional government (Trust reg), trust in the Italian Parliament (Trust parl), and trust in the national legal system (Trust leg). All regressions include regional fixed effects (NUTS-2 level) and year-fixed effects. ***, **, and * show statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level.

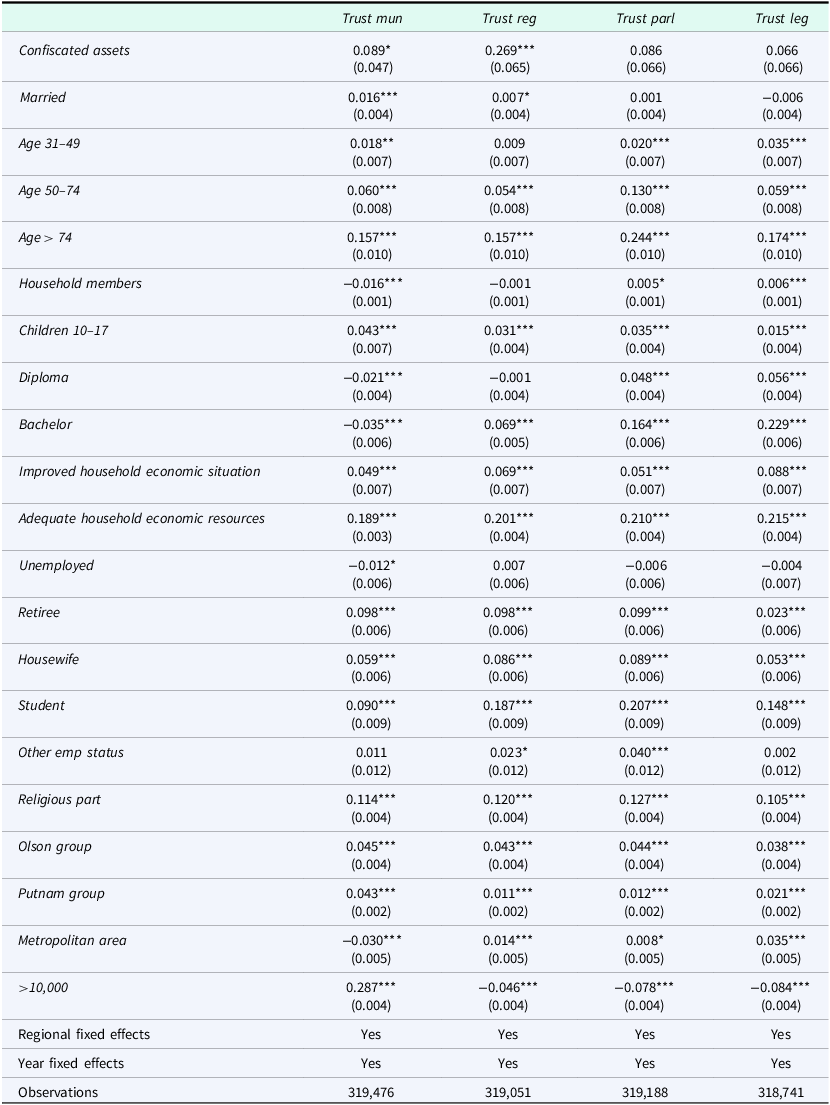

As a second step, we add the large set of individual controls from the ADL survey to the regressions. Table 2 shows similar results to those of the previous model specification. Asset confiscation has a positive and statistically significant correlation with trust in municipal and regional governments. The estimated coefficients of Confiscated assets increase slightly in these two regressions. The relationship is also positive with trust in the Italian Parliament, but the coefficient is not statistically significant. The effect on the legal system is still positive, but not significant.

Table 2. Ordered probit estimates with individual controls

Notes: Ordered probit estimates are reported with standard errors clustered at the regional level in parentheses. The units of observation are the individuals who responded to the ADL survey in the period 2014–2022. The dependent variables are: trust in the municipal government (Trust mun), trust in the regional government (Trust reg), trust in the Italian Parliament (Trust parl), and trust in the national legal system (Trust leg). All regressions include the individual-level controls described in the text, regional fixed effects (NUTS-2 level), and year-fixed effects. ***, **, and * show statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level.

The controls are generally statistically significant. Looking at the demographic and socio-economic variables, trust in the various government institutions is higher among older people (Age > 74) and those with children (Children 10–17). It is also higher among those with a bachelor’s degree (except for trust in municipal government), households with an improved economic situation (Improved household economic situation), and adequate economic resources (Adequate household economic resources), retired people, housewives, and students. Of the social capital variables, institutional trust is higher among individuals who attend church or other places of worship (Religious part) and were members of an Olson and Putnam group. The results on age differ from those of Camussi and Mancini (Reference Camussi and Mancini2019) but are similar to those of Corbacho et al. (Reference Corbacho, Philipp and Ruiz-Vega2015), while the findings on education, economic situation, and social capital are consistent with Kaasa and Andriani (Reference Kaasa and Andriani2022).

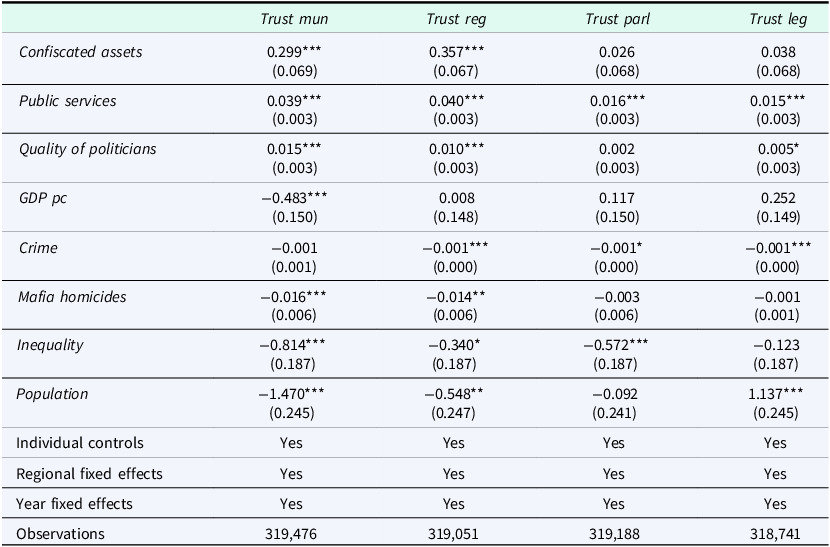

Finally, we extend the previous model specifications by including the regional-level controls. Table 3 shows the findings for Confiscated assets and regional variables. The individual controls are not shown for space considerations, but they are included in the regressions. The main results are consistent with the previous analysis. Confiscation of real estate assets is positively and significantly associated with trust in municipal and regional governments. The impact is larger for trust in regional governments. The relationship, although positive, is not statistically significant for the Italian Parliament and the legal system.

Table 3. Ordered probit estimates with individual and regional controls

Notes: Ordered probit estimates are reported with standard errors clustered at the regional level in parentheses. The units of observation are the individuals who responded to the ADL survey in the period 2014–2022. The dependent variables are: trust in the municipal government (Trust mun), trust in the regional government (Trust reg), trust in the Italian Parliament (Trust parl), and trust in the national legal system (Trust leg). All regressions include the regional- and individual-level controls described in the text, regional fixed effects (NUTS-2 level), and year-fixed effects. The coefficients of the individual-level controls are not shown to save space. ***, **, and * show statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level.

Looking at the regional controls, the impact of GDP pc is mixed. It is related to lower trust in municipal government, but it is not significant for other institutional trust outcomes. Consistent with Camussi and Mancini (Reference Camussi and Mancini2019), the quality of public services is positively associated with all types of trust (Public services). The quality of local politicians is associated with more trust in municipal and regional governments and the legal system. The lack of statistical significance in the regressions with the Italian Parliament, however, may be due to the variable Quality of politicians being computed based on municipal or regional elections. This variable, therefore, is not completely consistent with the dependent variable measuring trust in the Italian Parliament.

Where households’ perceptions of criminal activity are higher, trust in institutions is generally low. This result does not hold for the regression about trust in municipal government, where the estimated coefficient of Crime is not significant. Homicides by mafia organisations are associated with lower trust in municipal and regional governments. These results suggest that heightened mafia activity and extreme violent events perpetrated by these groups reduce citizens’ trust in local government institutions. Although our measures of crime differ from Blanco (Reference Blanco2013), Corbacho et al. (Reference Corbacho, Philipp and Ruiz-Vega2015), and Pazzona (Reference Pazzona2020), we find a negative correlation with the institution responsible for the management of law enforcement, consistent with these studies.

Income inequality, as in Rainer and Siedler (Reference Rainer and Siedler2009), is associated with less trust in municipal and regional governments and in the Italian Parliament. However, it is not statistically associated with trust in the legal system. Lastly, Population shows a mixed relationship with trust. Trust in municipal and regional governments is lower where the population is larger, but trust in the legal system is higher.

Overall, we find that the confiscation of real estate assets is associated with higher trust in local tiers of government but not in the Italian Parliament and legal system. Variables measuring individual and household economic conditions and social capital are relevant determinants of institutional trust, along with other regional-level measures such as the quality of public services, the quality of politicians, crime, and inequality.

To assess the size of the impact, we use the predicted probabilities for each category of the dependent variables at low and high values of Confiscated assets, which are one standard deviation below and above the mean.Footnote 10

As the intensity of confiscation increases from low to high, the probability that citizens have low trust (values of the dependent variables from 0 to 4) decreases, while the probability that citizens have high trust (values of the dependent variables from 6 to 10) increases. This is true for all regressions and all types of trust, except for trust in the legal system, which is not significant in the main analysis. The changes within the individual categories are quite small, but it must be kept in mind that the dependent variables have eleven categories. To give a broad idea of the overall impact of confiscation on trust, we can add together the probability changes in each category of the dependent variables. This gives us the following increases in trust: 2.1% for municipal government and 2.7% for regional government.

Endogeneity issues

We now turn our attention to endogeneity issues. The findings described so far showed a positive relationship between real estate assets confiscated from mafia organisations and institutional trust. It is, however, hard to assess whether this relationship is causal in the sense that asset confiscation increases trust in institutions.

The model specifications described so far covered a wide range of observed individual and regional characteristics. The inclusion of year and regional fixed effects in the model also accounted for unobserved cyclical variations and time-invariant regional heterogeneity. Endogeneity from omitted variables can, therefore, be considered a minor issue in our analysis. Our results, however, may still be biased by measurement errors and reverse causality. We measured institutional trust using respondents’ survey answers. These responses cannot be considered precise and quantitative measures of trust. It is also possible that the causal relationship is not from asset confiscation to trust, as we have hypothesised, but from trust to confiscations. It is possible that high levels of trust in institutions among citizens could strengthen the political and administrative processes required to confiscate and re-allocate mafia assets. Our model would then suffer from reverse causality.

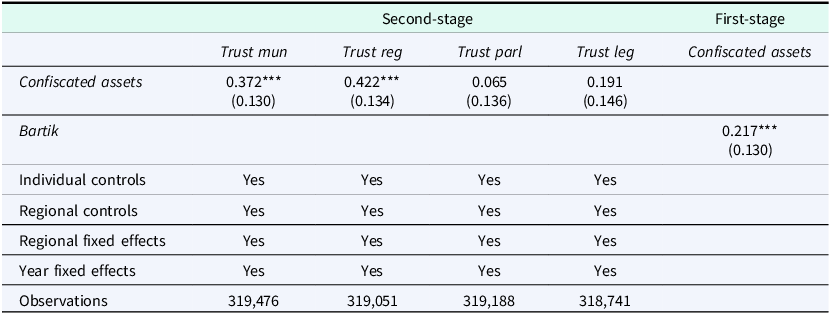

To be more confident that our results are not biased, we estimate an instrumental variable ordered probit model in which the variable Confiscated assets is instrumented by a Bartik-style instrument computed by interacting the regional historical shares of confiscated assets with the confiscations at the national level (variable Bartik). Both terms are scaled by population (1,000 inhabitants), like the variable Confiscated assets. Historical shares are computed using the number of asset confiscations in the period 2008–2010. We selected this period to improve the exogeneity of the regional shares of confiscations to our measures of institutional trust, which refer to the period 2014–2022. In addition, after 2010, the year in which the ANBSC was funded, the number of confiscations grew significantly. The results are shown in Table 4 and are consistent with previous estimates. The instrument Bartik is statistically significant at the 1% level in the first-stage regression. The estimated coefficients of Confiscated assets are slightly higher and are statistically significant for trust in municipal and regional governments. For the other types of trust, Confiscated assets are still positive, but it is not statistically significant.Footnote 11, Footnote 12

Table 4. Instrumental variable ordered probit estimates

Notes: Instrumental variable ordered probit estimates are reported with standard errors clustered at the regional level in parentheses. The instrument used for Confiscated assets is the Bartik instrument described in the text (variable Bartik). The units of observation are the individuals who responded to the ADL survey in the period 2014–2022. The dependent variables are: trust in the municipal government (Trust mun), trust in the regional government (Trust reg), trust in the Italian Parliament (Trust parl), and trust in the national legal system (Trust leg), for the second-stage, and Confiscated assets for the firststage. All regressions include the regional – and individual-level controls described in the text, regional fixed effects (NUTS-2 level), and year-fixed effects. The coefficients of the regional and individual-level controls are not shown to save space. ***, **, and * show statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level.

Heterogeneity analysis by geographic macro-areas

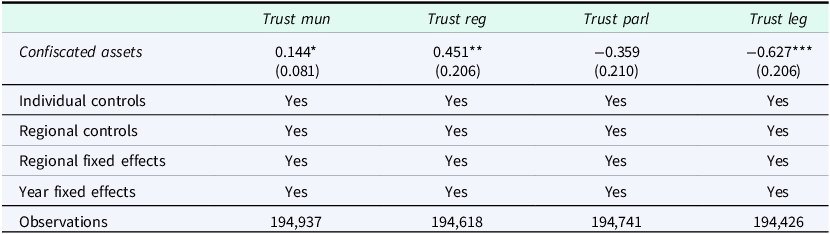

This analysis has covered the whole country. The descriptive statistics in Section Descriptive analysis, however, showed that both trust in government institutions and confiscation of real estate mafia assets varied across geographic areas. Trust in the lower tiers of government, for example, is typically high in the North and low in the South, while the opposite is true for trust in the Italian Parliament. The territorial distribution of real estate assets confiscated from mafia-type organisations highlights a greater concentration in Southern Italy than in Northern Italy. We therefore examine whether our main results vary across Italy’s geographic macro-areas. The model specification in Table 3, the ordered probit model with individual and regional controls, is re-estimated separately for Southern Italy (Table 5) and Central and Northern Italy (Table 6).

Table 5. Ordered probit estimates with individual and regional controls for Southern Italy

Notes: Ordered probit estimates are reported with standard errors clustered at the regional level in parentheses. The units of observation are the individuals who responded to the ADL survey in the period 2014–2022. The sample is restricted to the South of Italy. The dependent variables are: trust in the municipal government (Trust mun), trust in the regional government (Trust reg), trust in the Italian Parliament (Trust parl), and trust in the national legal system (Trust leg). All regressions include the regional – and individual-level controls described in the text, regional fixed effects (NUTS-2 level), and year-fixed effects. The coefficients of the regional – and individual-level controls are not shown to save space. ***, **, and * show statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level.

Table 6. Ordered probit estimates with individual and regional controls for Central and Northern Italy

Notes: Ordered probit estimates are reported with standard errors clustered at the regional level in parentheses. The units of observation are the individuals who responded to the ADL survey in the period 2014–2022. The sample is restricted to the Centre and North of Italy. The dependent variables are as follows: trust in the municipal government (Trust mun), trust in the regional government (Trust reg), trust in the Italian Parliament (Trust parl), and trust in the national legal system (Trust leg). All regressions include the regional – and individual-level controls described in the text, regional fixed effects (NUTS-2 level), and year-fixed effects. The coefficients of the regional – and individual-level controls are not shown to save space. ***, **, and * show statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level.

Looking at Southern Italy, it is interesting to observe that Confiscated assets is always significant, including the regression with trust in the Italian Parliament and legal system as dependent variables, and the coefficients are higher than in Table 3. The confiscation of real estate mafia assets has a strong impact in Southern regions, where it increases citizens’ trust in all government institutions and the legal system. Compared with the estimates for the whole country, the effect of asset confiscation is particularly higher for trust in municipal governments (+3.4%) and regional governments (+3.8%).Footnote 13 The effect is about 2% for trust in the Italian Parliament and the legal system.

In Central and Northern Italy, the results are weaker and mixed. Confiscated assets are positive and significant in the regressions with trust in municipal and regional government as dependent variables, but not statistically significant for trust in the Italian Parliament. Looking at the regression for the legal system, the coefficient of Confiscated assets is negative and significant, meaning that the confiscation of mafia assets reduces trust in the legal system. This result contrasts with the main analysis, where the coefficient, although not significant, was positive. In this geographic area, we suggest that there is general scepticism toward the highest levels of government, which is not affected by the confiscation of mafia real estate assets. The impact of the policy on asset confiscation is only clear for lower (local) tiers of government.

The predicted probabilities confirm that the impact of asset confiscation is lower in Northern and Central regions than in Southern Italy.Footnote 14 Across all categories of the dependent variables, as the intensity of asset confiscation increases, trust in the municipal government increases by 0.9% and in the regional government by 1.1%. Regarding the legal system, trust decreases by approximately 1.3%.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper investigated whether the policy of confiscating real estate assets from organised crime affected citizens’ trust in government institutions and the legal system. It focused on Italy, where public authorities have implemented a unique and effective policy based on the confiscation of illicit assets from mafia-type organisations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical attempt to link the policy of confiscating real estate assets from mafia-type organisations to trust in public institutions.

The findings can be interpreted in several ways. By removing real estate assets from the control of criminal organisations, the policy demonstrates (i) a symbolic value, signalling that the State is capable of countering organised crime by targeting the wealth accumulated through illicit means, thereby striking at the symbols of dominance and authority of criminal groups, and (ii) an economic value such as confiscated real estate assets, converted into public goods, are returned to local communities with the aim of improving social inclusion, employment, democratic participation, and overall the quality of life.

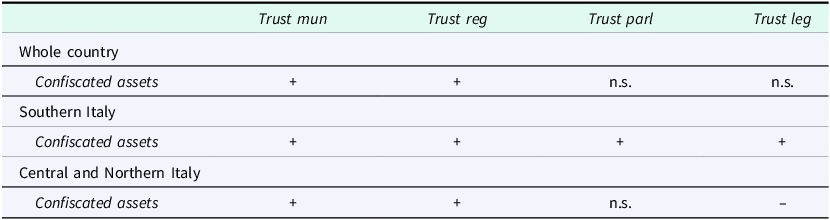

In developing our analysis, we have assumed that the ‘economic’ effects of mafia-type organisations are negative and perceived as such by citizens. However, research on organised crime has shown that these organisations may also be viewed positively by local populations. In their territories of origin, such as Southern Italy, mafia-type organisations provide protection and governance of the markets and territories (for example, drug trafficking, access to markets, creation of cartels, dispute resolution). In contrast, in areas of more recent expansion, such as Northern and Central Italy, they tend to focus mainly on trade-related activities, including drug trafficking, construction, restaurants, and bars (Catino, Reference Catino2020; Skarbek, Reference Skarbek2024). Table 7 summarises our results for the whole country as well as the different macro-areas.

Table 7. Estimated coefficients of Confiscated assets

Notes: The table shows the statistical significance of Confiscated assets in the regressions for the whole country, South, and Centre-North. ‘+’/‘–’ denote a positive/negative statistically significant regression coefficient; n.s. denotes a not statistically significant regression coefficient.

At the national level, the results highlight a positive effect on trust in local government institutions (municipal and regional governments). This suggests that the confiscation of real estate assets increases citizens’ trust in local administrative bodies responsible for reallocating these within the territory. This effect already emerges at the time of confiscation, as our data on trust and confiscations refer to that time, and not only when the assets are re-allocated. Although on average there is a delay of about eight years between confiscation and re-allocation (Boeri et al., Reference Boeri, Di Cataldo and Pietrostefani2024), we suggest that the increased trust in the administrative bodies may manifest even earlier the re-allocation for a number of reasons relating to citizens’ perception of the phenomenon, the role of the institutions involved and the transparency that must be respected by lawFootnote 15 in making the information on confiscated assets accessible to all people and organisations (Bisogno et al., Reference Bisogno, Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Citro and Vaia2024; Giorgi et al., Reference Giorgi, Parma, Bernardini, Bellini, Paganin and Campioli2025). First, periodic reports from the Anti-Mafia Investigative Directorate (Direzione Investigativa Antimafia–DIA) and the Parliamentary Anti-Mafia Commission,Footnote 16 containing information on confiscations, may increase trust in the local public institutions by reinforcing the credibility of the Italian State in combating mafia-type associations. Second, many local public institutions are active in supporting civic movements against organised crime and promote awareness-raising initiatives, particularly among younger generations (La Spina, Reference La Spina and Paoli2014). Civic organisations committed to legality and social reuse of confiscated assets also play a crucial role in transforming criminal assets into common goods (Ferroni, Reference Ferroni, Ferroni, Galdini and Ruocco2023). Through advocacy activities, public campaigns, and local initiatives, they turn seizures into a ‘promise of future reuse’, thereby promoting an immediate increase in trust in those institutions perceived as closest to citizens, namely local and regional ones (Laratta, Reference Laratta2010). These activities ensure that the social and/or institutional reuse of confiscated assets becomes embedded in the public narrative long before its practical implementation. Third, in local contexts, news of the seizure or confiscation of assets is not an abstract, technical-legal matter but rather an event of considerable symbolic resonance. National media tend to amplify these stories, placing significant emphasis on the role of institutions in the fight against organised crime (Di Ronco and Lavorgna, Reference Di Ronco and Lavorgna2018). Moreover, direct or personal familiarity with the criminal phenomenon and the individuals involved amplifies the reputational impact of such events, establishing an immediate link between judicial outcomes and the perception of a potential path towards collective redemption (Libera, 2018).

Additionally, the results show a positive, though statistically insignificant, impact of asset confiscation on trust in the Italian Parliament and the legal system. Hence, confiscation does not appear to increase trust in the representative institutions, which draw up anti-mafia laws, nor in the judiciary, which is responsible for enforcing confiscations. This finding aligns with Campedelli et al. (Reference Campedelli, Daniele, Martinangeli and Pinotti2023), who, using a representative sample of Italian individuals, demonstrate that exposure to visual and textual content concerning organised crime violence does not increase trust in the justice system. Thus, the lack of such significant effects may be interpreted in terms of the ‘symbolic value’ of the policy. Citizens may be disillusioned with the political and operational capacity of the political system and the courts to fight mafia-type organisations effectively.

The results also reveal significant territorial differences across Italian macro-areas. As claimed in section Confiscated real estate mafia assets and institutional trust, in the South, where the presence of criminal organisations is pervasive, visible, and strengthened also through mafia homicides, the confiscation policy of real estate assets is perceived as a credible tool for fighting organised crime, reaffirming the rule of law and promoting socio-economic local development through the creation of social activities. In these areas, we observe a positive impact of the confiscation policy on all dimensions of trust, including trust in the Italian Parliament and the legal system.

In Northern and Central Italy, where the presence of mafia-type organisation is a recent phenomenon, less visible due to lower levels of violence, and embedded within economic and financial structures, therefore perceived as less socially and economically threatening, the confiscation of real estate assets has no effect on trust in the national Parliament and a negative effect on trust in the legal system.

The lack of significance for the Italian Parliament seems to confirm Figure 1, which shows that in several regions of Central and Northern Italy, citizens exhibit higher levels of trust in local institutions than in the Italian Parliament (ISTAT, 2022). In general, citizens in these geographic areas are sceptical towards the actions of the higher levels of government and other national institutions, such as the legal system. Therefore, while confiscation may increase trust in the local government, it does not appear to affect trust in the national Parliament, which remains generally low.

The impact on trust in the legal system is also negative. A possible explanation for this result is that, in Central and Northern Italy, where the number of confiscations is low, citizens perceive a lower level of mafia presence; therefore, more confiscations could be interpreted as widespread infiltration of mafia activity rather than as an effective way to fight organised crime. In such contexts, asset confiscation may be interpreted as a signal of an inadequate capacity of the legal system to prevent criminal activity. This can undermine trust in the legal system, as citizens may perceive that institutions intervene only at a later stage, without an effective deterrent action (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012). This interpretation is supported by our data, which suggests a non-linear relationship between asset confiscation and trust. Table S11 in the supplementary materials shows the impact of Confiscated assets and its squared term (Confiscated assets sqrd) on trust in the legal system. The coefficient of Confiscated assets is negative, while that of Confiscated assets sqrd is positive. These estimates support the view of a U-shaped relationship between confiscation and trust in the legal system. When the confiscations are few, as in many areas of Northern and Central Italy, they reduce trust in the legal system. The relationship becomes positive as confiscations increase and strengthen perceptions of the mafia’s presence among citizens, as typically occurs in the South.

An alternative explanation relates to the economic dimension of mafia activity. When mafia-type organisations expand from the South to Central and Northern Italy, they engage in both legal and illegal profit-making activities, often forming alliances with local entrepreneurs (Moro and Villa, Reference Moro and Villa2017; Paoli, Reference Paoli and Paoli2014). For citizens aware of such infiltration, the growing involvement of the judiciary in the economic sphere, through confiscations, may be viewed as an obstacle to economic activity, increasing business costs, reducing employment and disposable income, as well as constraining investment (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005; Djankov et al., Reference Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer2002; Le Moglie and Sorrenti, Reference Le Moglie and Sorrenti2022; Schneider and Enste, Reference Schneider and Enste2000). Consequently, the legal system may be perceived as interfering with the private economic domain, thus reducing trust.

Overall, our findings confirm the principle enshrined in Italian law and the European directives on anti-mafia measures: asset confiscation plays a crucial role in combating mafia-type organisations by reinforcing citizens’ trust in public institutions, particularly when such organisations visibly dominate local territories. In these contexts, confiscations are perceived as a direct attack on criminal power. Our results suggest that anti-mafia policies are more effective when they target the heart of these organisations’ illegal activities, namely their economic interests (Calamunci et al., Reference Calamunci, Ferrante and Scebba2022). They reinforce the knowledge that the strategy to defeat these criminal organisations must be based on repressive and preventive instruments and that further improvements will have a prominent impact.

The analysis presented in this paper opens avenues for future research, although it is not without limitations. Even though we focused on the Italian context, the economic infiltration of organised crime is a widespread global phenomenon. The Italian experience shows that asset confiscation is a strategic tool for dismantling organised crime, while also increasing trust in public institutions. Many European Union countries have implemented the European Union Directives 2014/42/EU and 2024/1260/EU on the recovery and confiscation of criminal assets. Both directives are part of the framework of harmonisation of European criminal law, aimed at strengthening the fight against organised and financial crime through asset enforcement, and strongly suggest to the member states to include in their legislation the reuse of confiscated real estate assets for public interest and social purposes. From this point of view, future research is needed to assess the external validity of our results in other EU countries and to investigate the transmission channels in more detail.

We acknowledge that using survey data to measure trust in public institutions may pose challenges. However, this is a common strategy in the institutional economics literature, and several studies have used survey data to measure institutional trust (Camussi and Mancini, Reference Camussi and Mancini2019; Kaasa and Andriani, Reference Kaasa and Andriani2022). The individual-level data used in our analysis are drawn from the ADL survey. For each individual, the ADL survey provides information on the region of residence (NUTS 2) but not on the municipality. Therefore, data on confiscated real estate assets can be merged with individual-level data only at the regional level. Using more geographically disaggregated data can further corroborate the robustness of our results. Finally, our dataset covers only the confiscation of real estate assets and does not include information on their subsequent reallocation and reuse. This warrants further investigation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137426100459.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to the editors and six anonymous reviewers whose comments allowed a substantial improvement of the paper. Needless to say, usual caveats apply. Luca Pennacchio acknowledges financial support from the Italian Ministry of University and Research under grants PRIN 2022 PNRR P20227JN7R–CUP I53D23006170001.