Introduction

In September 2024, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat quietly celebrated its 20th anniversary. Established by Measure 1 (2003) (ATCM, 2003a) and formally commencing operations in Buenos Aires on 1 September 2004, the Secretariat was the latest significant institutional development created within the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) (Scott, Reference Scott2003). Designed to provide administrative and logistical support to both the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) and the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP), the Secretariat was conceived as a modest but necessary innovation to enhance the operation of the 1959 Antarctic Treaty and the 1991 Environmental Protocol (Colacrai & Molinari, Reference Colacrai and Molinari2015). However, despite the significance of this institutional development, the Secretariat’s 20th anniversary passed with little impact or critical reflection within the Antarctic policy and academic community.

In recent years, the study of treaty secretariats, particularly within the field of global environmental governance, has gained increasing prominence. For a long time, the role of these institutions remained largely overlooked in international law and international relations scholarship. However, recent contributions by scholars such as Bauer (Reference Bauer2006), Biermann et al. (Reference Biermann, Siebenhüner, Bauer, Busch, Campe, Dingwerth, Biermann, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009), Jinnah (Reference Jinnah2014), and Reinalda (Reference Reinalda2020) have begun to fill this gap, offering valuable insights into how secretariats influence global politics and why their influence matters. While these studies have significantly advanced our understanding of the authority, functions, and legitimacy of treaty secretariats, none have examined the role of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat within the governance of the Antarctic region. This absence is notable given the growing complexity of Antarctic affairs. Francioni (Reference Francioni2000), Scott (Reference Scott2003), and Vigni (Reference Vigni2003, Reference Vigni, Triggs and Riddel2007) have discussed the establishment of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat and its relevance in international law. However, all these contributions now range from nearly to more than two decades old. It is therefore important to consider whether a small treaty secretariat such as the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat can nonetheless act as a relevant and influential actor within the unique legal, institutional, and geopolitical context of the ATS.

This article seeks to address this gap in analysis by offering a comprehensive assessment of the Secretariat’s role within the ATS after 20 years of existence. It examines the Secretariat’s origins and mandate, evaluates its contributions to the efficiency of the Antarctic regime, and identifies the structural constraints that continue to limit its capacity. It also reflects on the Secretariat’s potential to evolve in response to increasing demands on Antarctic governance, particularly in the context of accelerating climate change, growing geopolitical competition, and evolving expectations for transparency and institutional accountability of the ATS.

The article is structured in four main sections. Following this introduction, Section The establishment of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat provides a historical overview of the Secretariat’s establishment and legal foundations. Section The Secretariat’s functions and performance over the last two decades examines the Secretariat’s functions, achievements, and limitations, including its formal mandate within the ATS, its contributions over the past two decades, and the structural and political constraints that shape its role. Section The Secretariat in a Changing Antarctic Context analyses the Secretariat’s evolving importance in a changing Antarctic context, considering emerging geopolitical and environmental challenges, and concludes with reflections on its growing significance in supporting the continued effectiveness of the ATS.

The establishment of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat

The Antarctic region is governed primarily by the ATS, whose central instrument is the 1959 Antarctic Treaty. The Antarctic Treaty was adopted as a regional response to the increasingly tense situation in Antarctica during the 1940s and 1950s. While seven states – Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom – claimed sovereignty over different Antarctic territories, the two great powers, the United States and the Soviet Union, did not recognise any of those claims and explicitly reserved the right to assert claims over part or all of the continent in the future (Auburn, Reference Auburn1982). Against this backdrop of rising geopolitical tension exacerbated by overlapping claims of Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom on the Antarctic Peninsula and fears that Cold War rivalry might extend southward, the 12 states that participated in the 1957–1958 International Geophysical Year negotiated and adopted the Antarctic Treaty (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Its primary aims are to put “on hold” disruptive arguments over territorial sovereignty in Antarctica (Article IV), prohibit any measures of a military nature in the region (Article I), and promote freedom of scientific research in a spirit of international cooperation (Article II) (Guyer, Reference Guyer1973). The Treaty was specifically designed to accommodate divergent views on sovereignty in Antarctica. While it has been largely successful in defusing sovereignty-related disputes, concerns over this issue remain relevant and continue to influence the development of the ATS (Rothwell, Reference Rothwell1996). These concerns have also played a significant role in shaping the establishment of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty deliberately did not include provisions for permanent institutions, treaty organs, or any type of administrative infrastructure with secretariat functions (Francioni, Reference Francioni2000). Article IX of the Antarctic Treaty established the ATCM, a forum for “exchanging information, consulting on matters of common interest, and recommending measures to advance the Treaty’s principles and objectives.” These measures may concern the exclusive use of Antarctica for peaceful purposes, the facilitation of scientific research and international scientific cooperation, the implementation of inspection rights under Article VII, questions related to the exercise of jurisdiction in the region, and the preservation and conservation of its living resources. The ATCM forms the backbone of the governance framework that continues to shape the legal and political order of Antarctica today.

The ATCM brings together various actors involved in Antarctic governance. The main participants are the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties (ATCPs), States that have demonstrated substantial scientific activity in Antarctica and are therefore entitled to participate in the decision-making process (Molenaar, Reference Molenaar2021). In addition to ATCPs, the non-Consultative Parties – which are Parties to the Treaty but do not meet the criteria for consultative party status – may attend the meetings but do not participate in the decision-making mechanism. ATCMs are also attended by several observers such as the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), and the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs, as well as invited environmental and industry experts such as the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition and the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. This participation ensures that ATCMs benefit from a range of scientific, legal, and policy expertise.

The ATCM operates on the basis of consensus among the ATCPs, reflecting the cooperative spirit of the Antarctic Treaty (Jackson, Reference Jackson2018). At the ATCMs, the Consultative Parties might adopt, by consensus, Measures (which are legally binding after being adopted at the meeting and subsequently approved by all Consultative Parties), Decisions (administrative in nature and typically concern the ATCM’s internal procedures), and Resolutions (which are non-binding and provide guidance or express shared views on specific issues). Before 1995, these instruments were known collectively as Recommendations. The adoption of Measures, Decisions, and Resolutions (and previously Recommendations) has enabled the ATS to adapt to new challenges and coordinate actions among the Parties, while maintaining the delicate balance of national and international community interests that underpin the Antarctic legal and institutional regime. The ATS has been able to accommodate the interests (including, at times, conflicting ones) of the seven claimant states, the two “quasi” or “semi” claimant states (the United States and the Russian Federation), and the non-claimant states. While the rule of consensus can limit rapid decision-making, it has also helped foster a stable governance framework based on mutual respect and shared responsibility.

For much of its early history, the ATCM operated without a permanent institutional apparatus. From the first ATCM in Canberra in 1961 until 1994, the ATCM generally met every two years. However, since 1994, meetings have been held annually. In keeping with the Treaty’s emphasis on cooperation and consensus among sovereign equals, annual ATCMs are held on a rotating basis. The ATCMs are hosted by the Consultative Parties in alphabetical order of their English names. Until the creation of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, the Antarctic Treaty operated under a decentralised administration in which the host state assumed responsibility for administrative coordination, document preparation, and translation (Sampaio, Reference Sampaio2022). While this ad hoc, decentralised model sustained the regime for more than four decades (1961–2004), it also led to inconsistencies in record keeping, delays in information sharing, and inefficiencies in maintaining institutional memory.

Discussions on the establishment of a secretariat for the Antarctic Treaty arose during the creation of the Antarctic regime. At the Washington negotiations for the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, proposals by the United Kingdom and others for a permanent secretariat met with reluctance from several states, particularly Argentina, Australia, and Chile, who were cautious about creating an institutional structure that could resemble an international organisation (Hanessian, Reference Hanessian1960). At ATCM I, South Africa proposed the creation of a small administrative body to support the operation of the ATCM (Scott, Reference Scott2003). However, this proposal was also rejected based on the same grounds, as some ATCPs feared that a permanent institution could weaken their legal arguments regarding sovereignty in Antarctica by acting as an independent or separate political actor with its own international legal personality. As a result, the idea of a permanent secretariat remained politically sensitive and nascent for decades, reflecting the broader tensions between states on cooperation and sovereignty within the ATS.

However, the 1980s marked a turning point in the evolution of the ATS, as internal and external challenges compelled the ATCPs to reconsider their institutional foundations (Haward & Jackson, Reference Haward and Jackson2023). Internally, the ATCM faced organisational challenges due to an increasing number ATCPs (including new acceding states China, India, and Brazil), while debates about the potential exploitation of mineral resources in Antarctica intensified (Joyner, Reference Joyner1987). Outside the ATS, some developing countries led by Malaysia began using the United Nations General Assembly as a forum to challenge the legitimacy of the ATS in the region (Beck, Reference Beck, Dodds, Hemmings and Roberts2017). As part of its response to both internal and external challenges, the ATCM established a working group to examine the “Operation of the Antarctic Treaty System.” In this context, at the 1985 ATCM, several delegations expressed the view that the way the ATCM’s work had evolved in recent years pointed to a growing need for some form of permanent infrastructure, and for the first time, the Final Report formally acknowledged the necessity of establishing a permanent administrative mechanism to ensure the continued effectiveness of the ATS (ATCM, 1985). The issue of establishing a new institution to support the ATCM thus became a more prominent topic at subsequent ATCMs.

By the late 1980s, there was increasing interest among ATCPs in creating a new permanent administrative body within the ATS. Several proposals were made to define its structure and main functions (Francioni, Reference Francioni2000). The ATS was already familiar with establishing and operating permanent institutions. The CAMLR Convention had already created a permanent secretariat, which is based in Hobart (Australia) and has operated since 1982. At the same time, while the 1988 Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities did not enter into force, it proposed the creation of several permanent institutions, including a secretariat. However, despite these institutional advances within the ATS, some concerns about the Secretariat’s cost, functions, and legal personality remained latent (Colacrai & Molinari, Reference Colacrai and Molinari2015). While such concerns were genuine and more discussion was needed, by 1987, most (but not all) ATCP delegates recognised that a secretariat was necessary to support the increasingly complex functions of the ATS. Some states remained reluctant to support the creation of a new institution, arguing that the existing framework – under which administrative functions were carried out by the host country of each ATCM on a rotating basis – remained adequate and appropriate (ATCM, 1987).

At the XVII ATCM in Venice in 1992, consensus on the need for a secretariat was finally reached. After the adoption of the Protocol on Environmental Protection in 1991, which significantly expanded the legal and operational responsibilities of the ATS, the ATCPs included the topic as a standing item on the ATCM agenda, with ongoing annual discussions focusing on key institutional issues, such as the location, functions, composition, legal personality, and funding mechanisms of the future secretariat. Contact groups under Working Group I, chaired by Professor Francesco Francioni (Italy) in 1992 and later by Professor Rüdiger Wolfrum (Federal Republic of Germany), were also formed by the ATCM to further discuss the creation of the Secretariat. These contact groups discussed inter alia the legal personality and functions of the Secretariat and privileges and immunities of the staff members. Key working papers were submitted by various countries, reflecting differing views on these issues (Francioni, Reference Francioni2000). The group drafted several key texts that laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Secretariat, as reflected in Annex E of the Final Report of the 1992 ATCM and Annex D of the Final Report of the 1994 ATCM (Scott, Reference Scott2003). However, despite these developments, the process of reaching consensus among the ATCPs on the final details for establishing the new institution was complex and reflected the ongoing need to balance administrative efficiency with political sensitivities surrounding sovereignty and concerns about creating an international organisation with an international legal personality separate from that of the Antarctic Treaty Parties (Andersen, Reference Andersen1988).

The location of the Secretariat proved to be one of the most contentious issues during the negotiations. Only Argentina (Buenos Aires) and the United States (Washington) were proposed for hosting the future Secretariat at the 1992 ATCM. However, the United States withdrew its proposal in 1994, making Buenos Aires the sole candidate (ATCM, 1994). As previously mentioned, Argentina opposed the creation of a permanent institution even before the adoption of the Antarctic Treaty due to fears that it could diminish its position as a state claiming sovereignty over Antarctic territory (Hanessian, Reference Hanessian1960). However, as the ATS evolved into a more complex regime addressing, among other issues, the protection of the Antarctic environment under the recently adopted Environmental Protocol, Argentina shifted its position in 1992. Having spoken out against the creation of a permanent institution as recently as 1991 (ATCM, 1991), Argentina now expressed support for a new Antarctic body and proposed that it be headquartered in Buenos Aires (ATCM, 1992). While the Argentine proposal was strongly supported by the vast majority of ATCPs, it met with strong resistance from the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom was reluctant to support Buenos Aires as the location of the Secretariat due to geopolitical sensitivities surrounding sovereignty claims in Antarctica (Francioni, Reference Francioni2000). As one of the countries with overlapping claims, the United Kingdom was concerned that Argentina might use the presence of the institution on its territory to undermine or deny British rights over Antarctic areas. Australia even proposed Hobart as the headquarters of the Secretariat to ease these tensions between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1998 (ATCM, 1998). However, the proposal was quickly dismissed, with several countries (including China) arguing that the institution should be located in South America to better reflect the geographic and political diversity of the Antarctic Treaty membership (Scott, Reference Scott2003). After lengthy negotiations, the United Kingdom finally reported that it would not withhold consensus on the Argentine proposal at the XXIV ATCM in St. Petersburg, 2001. With the United Kingdom on board (a decision that could have been related to significant changes Argentina made to the structures of the Dirección Nacional del Antártico (Argentine Antarctic Program) (Colacrai, Reference Colacrai2004), the way was opened to create the new institution.

With consensus reached on its location, the establishment of the Secretariat advanced toward formal implementation. After more than a decade of negotiations, the ATCPs adopted Measure 1 at the XXVI ATCM in Madrid in 2003 (ATCM, 2003a), officially creating the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, to be based in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The Headquarters Agreement between the ATCM and the Government of Argentina was annexed to this Measure (ATCM, 2003c), and Decision 1 (2003) concerning the allocation of financial contributions to the Secretariat was also adopted (ATCM, 2003b). In 2003, a debate had sparked different positions since the Antarctic Treaty negotiations had been concluded. Measure 1 (2003) thus became the last major institutional development within the ATS to date.

The Secretariat is a subordinated organ of the ATCM (Article I of Measure 1 (2003)). This Antarctic institution is not an independent body within the ATS and does not hold autonomous decision-making authority. As has been noted, the Secretariat is “the servant of the Consultative Parties, not the master” (Andersen, Reference Andersen1988). It is also worth highlighting that the ATCM itself does not possess an international legal personality, which further limits the capacity of the Secretariat to act autonomously within the ATS. At the same time, the Secretariat has neither replaced the United States as the depositary government for the Antarctic Treaty (Article XIII, Antarctic Treaty) nor created a new international organisation. It can therefore be classified as a “treaty secretariat,” as opposed to the secretariat of an intergovernmental organisation (Reinalda, Reference Reinalda2020). Its establishment did not alter the Consultative Party–centred nature of Antarctic governance; the ATCPs remain the principal actors within the Antarctic legal and institutional framework. Nevertheless, the creation of the Secretariat marked a significant, if often underappreciated, moment in the institutional evolution of the ATS, introducing a degree of permanence and continuity of administrative capacity without challenging the primacy of States in Antarctic governance.

In accordance with Article 2 of the Headquarters Agreement (ATCM, 2003c), the Secretariat has legal personality and capacity for the purpose of performing its functions within the territory of the Argentine Republic (i.e. it does not possess international legal personality). It exercises its legal capacity only to the extent authorised by the ATCM. It has, in particular, the capacity to contract, to acquire and dispose of movable and immovable property, and to institute and be a party to legal proceedings. It is funded through a system of assessed contributions by Consultative Parties, with oversight provided by the ATCM (non-Consultative Parties do not contribute to the budget of the Secretariat). Half of the budget comes from contributions from all Consultative Parties in equal parts, while the other half comes from the contributions that the Consultative Parties make, based on the scale of their national activities in Antarctica and considering the payment capacity of each of them Decision 1 (2003) (ATCM, 2003b). Any Contracting Party (Consultative or non-Consultative) may also make voluntary contributions at any time. The budget of the Secretariat for the upcoming year must be approved by the representatives of all the Consultative Parties present annually at the ATCM.

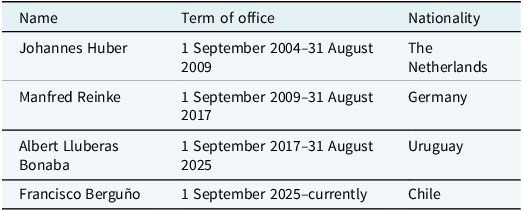

The Secretariat began its operations in September 2004 under its first Executive Secretary, Johannes Huber, from the Netherlands. Executive Secretaries are selected by the ATCM and can only be drawn from the nationals of a Consultative Party. At the last ATCM in Milan in 2025, Francisco Berguño (a Chilean diplomat with a long trajectory in Antarctic affairs) was selected to replace Albert Lluberas Bonaba (a Uruguayan Antarctic expert with extensive experience in Antarctic matters and former Secretary General of the Uruguayan Antarctic Institute) (see Table 1 for the list of all Executive Secretaries). The Secretariat operates in a cost-effective manner (Article IV, Measure 1 (2003)). It includes the Executive Secretary and other staff members selected by him/her. The Secretariat currently consists of the Executive Secretary, the Deputy Executive Secretary, and eight members in the general staff category, who serve under the procedures, terms, and conditions set out in the Staff Regulations. Under the guidance of successive Executive Secretaries, the Secretariat has maintained continuity and stability in administering the ATCM and CEP, with little indication that this consistent institutional role will change in the near future.

Table 1. List of Executive Secretaries

The Secretariat’s functions and performance over the last two decades

The role of the Secretariat within the ATS

The Antarctic Treaty Secretariat was deliberately created with limited functions and as a cost-effective institution. To allay any concerns among ATCPs regarding the Secretariat’s legal capacity and subjectivity, which would ultimately undermine its decision-making power (Francioni, Reference Francioni2000), the institution has been formally limited to purely administrative functions. Its mandate remains narrow in scope, reflecting the political sensitivities of ATCPs that were wary of establishing a body with decision-making or agenda-setting, which could undermine the Consultative Parties-driven character. At the same time, this institution does not generate significant costs for the parties (Colacrai & Molinari, Reference Colacrai and Molinari2015). This careful design ensured that the Secretariat was designed to support, rather than alter, the intergovernmental and consensus-based character of the ATS at the lowest economic cost possible.

As recognised by Measure 1 (2003) (ATCM, 2003a), the Secretariat’s primary role is to assist the ATCM and the CEP in the performance of their functions. In practice, the Secretariat is responsible for assisting the host government in organising the ATCMs and the CEP meetings (and any other meetings held in conjunction with the ATCM or within the framework of them, such as special ATCM or meetings of the experts). The Secretariat is responsible for receiving and preparing all documents submitted by the delegation to be discussed or introduced at the meetings (i.e., Working Papers, Information Papers, and Background Papers). The Secretariat also prepares and distributes meeting agendas and reports, translates meeting documents, provides interpretation services, and assists the ATCM in drafting meeting documents, including the final report. Under the Secretariat’s coordination, a Chief Rapporteur supervises a team of expert, local, and sometimes trainee rapporteurs, whose accurate, timely, and impartial documentation of the ATCM’s discussions and decisions is essential for producing a reliable Final Report serving as the authoritative record of the Meeting. These tasks require a deeper understanding of the operation of the Antarctic Treaty and the Environmental Protocol.

In addition to its coordinating role during meetings, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat contributes to the work of the ATCM and CEP by submitting papers that support the effective functioning of the regime. These papers (known as Secretariat Papers or SP) might be submitted before the ATCM to address different Antarctic Treaty institutional challenges. For instance, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat submitted 16 Secretariat Papers for the last ATCM 47 – CEP 27 in Milan in 2025 (ATCM, 2025a). These papers included information about proofreading the French, Russian, and Spanish versions of the ATCM Rules of Procedure, CEP Rules of Procedure, and General Guidelines for Visitors to the Antarctic. SPs themselves do not require the adoption of a Measure; they are primarily administrative and informational to support the smooth functioning of the ATCM and the CEP. However, some SPs that include requests for analysis may lead to the adoption of a Decision or a Resolution if the ATCPs choose to act. For instance, an SP may lead to the amendment of the Rules of Procedure. The Decision approving the Secretariat’s budget and its preliminary activities for the coming years is also based on an SP submitted by the Secretariat. The Secretariat also prepares reports on its activities and assists the ATCM in reviewing the status of previous Recommendations and Measures adopted under Article IX of the Antarctic Treaty.

The Secretariat also performs a range of important intersessional functions. Between the annual meetings of the ATCM and CEP, it is responsible for facilitating the exchange of information, coordinating communications, and supporting collaboration among the Parties. A key tool in this effort is the Electronic Information Exchange System (EIES), a digital platform managed by the Secretariat to modernise and streamline the submission, access, and distribution of Treaty-related documents. The Secretariat also coordinates the work of Intersessional Contact Groups (ICGs), which are established by the ATCM to facilitate in-depth discussions, information sharing, and the development of potential measures or frameworks on specific topics such as the ICG on Antarctic Tourism. It also plays an important role in coordinating subsidiary bodies such as the Subsidiary Group on Climate Change Response. Acting under the direction of the ATCM, the Secretariat also provides coordination and liaison with other elements of the ATS (such as CCAMLR) as well as with relevant international bodies and organisations (such as the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels). These intersessional responsibilities reinforce the Secretariat’s role as a central hub for communication and coordination within the ATS.

The official website of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat plays a crucial role in promoting transparency and ensuring the effective dissemination of information within the ATS. It serves as a centralised and accessible repository for a wide range of documents and resources, including a searchable database and detailed maps relevant to Antarctic governance. The website regularly publishes the official minutes of the ATCMs and the CEP meetings. It also facilitates access to a comprehensive archive of ATS documents and provides up-to-date information on the legal instruments, institutional arrangements, and ongoing developments within the system. The website serves as an essential tool for enhancing the transparency of the Antarctic regime and fostering accountability among Antarctic Treaty Parties.

Training and capacity-building are also key components of the Secretariat’s efforts to support the effective functioning of the ATS. The Secretariat conducts both in-person and virtual training sessions for Party delegates and operators of the EIES. These sessions are designed to support the effective use of the EIES, introduce new functionalities, and provide a platform for the exchange of feedback and ideas on how to continually improve the system. In addition to EIES-related training, the Secretariat also organises capacity-building activities at its headquarters in Buenos Aires, focusing on matters related to the ATCM. These initiatives contribute to building institutional knowledge, fostering consistency in Treaty practice, and enhancing the overall efficiency of the ATS.

Annex VI of the Environmental Protocol, titled Liability Arising from Environmental Emergencies, envisages an expanded administrative role for the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat in the event of environmental emergencies. Although Annex VI has not yet entered into force, it anticipates a new function for the Secretariat, reflecting its broader mandate to support the ATS. Specifically, Article 12 assigns the Secretariat responsibility for maintaining and administering a fund to reimburse, inter alia, the reasonable costs incurred by a party or parties in responding to an environmental emergency when an operator fails to take prompt and effective action. This prospective role underscores the Secretariat’s importance in promoting coordination, accountability, and effective implementation of environmental governance measures within the ATS (Proelss & Steenkamp, Reference Proelss, Steenkamp, Gailhofer, Krebs, Proelss, Schmalenbach and Verheyen2023). By managing this fund, the Secretariat would act as a central administrative hub, facilitating collective action and ensuring that response measures are supported even when individual operators do not fulfil their obligations.

Key contributions of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat

Since the beginning of its operation in 2004, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat has played a central role in enhancing the effective functioning of the ATS. As noted above, the Secretariat was created with a narrowly defined mandate, primarily to provide administrative and logistical support to the ATCM and CEP. However, in practice, although it has shied away from a stronger advocacy role, its contributions over the past two decades have been considerably more substantial. These contributions have made the Secretariat a fundamental actor within Antarctic governance. Any assessment of the relevance of the ATS in the 21st century must therefore take into account the Secretariat’s evolving role and the impact it has had since its inception.

The Secretariat contributes to ensuring institutional memory. This is extremely important in a decentralised regime such as the ATS (Francioni, Reference Francioni2000) because it allows continuity, consistency, and historical knowledge in institutional regimes (Hardt, Reference Hardt2018). The Antarctic Treaty Secretariat upholds the accumulated body of knowledge, practices, decisions, documents, and experiences developed through the ATCMs and related processes since 1961. By centralising, organising, digitising, and making open-access a vast repository of Treaty-related documents ranging from historical reports of ATCMs and CEP meetings to contemporary Measures, Decisions, and Resolutions, it has enhanced the system’s institutional memory and accessibility for a wide range of stakeholders (Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, n.d.). This archival infrastructure plays a critical role in preserving the continuity of Antarctic governance, allowing Parties to trace the evolution of legal and policy positions over time and draw on precedents in ongoing negotiations. It also serves a democratising function within the regime. Smaller States or newer Consultative Parties, which may lack the internal administrative capacity to maintain comprehensive and easily retrievable records, now have reliable access to authoritative information that facilitates meaningful participation in the decision-making process. Furthermore, the public availability of this documentation promotes transparency and academic analysis, contributing to greater understanding and oversight of the ATS by stakeholders, academic institutions, civil society, and the public.

The Secretariat’s assistance to the ATCM host country has also contributed to the professionalisation and standardisation of ATCMs and CEP meetings. Before the Secretariat’s establishment, meeting formats, documentation styles, and record-keeping practices varied significantly depending on the host state’s administrative capacity, available resources, and interpretation of its responsibilities. This inconsistency not only affected institutional memory but also made it difficult to ensure continuity between meetings and to track the evolution of key policy discussions. The Secretariat has introduced a level of procedural consistency, linguistic accuracy, and quality control that has greatly enhanced the efficiency, reliability, and transparency of Treaty meetings (Reinke, Reference Reinke2018). It ensures that working papers, information papers, and final reports are produced according to standardised templates and timelines, and it supports simultaneous translation and distribution, which is crucial for equitable participation. Moreover, the Secretariat’s archiving and indexing practices have facilitated access to historical records, enabling Parties and observers to engage more effectively in deliberations and monitor the implementation of agreed measures over time.

The Antarctic Treaty Secretariat has also improved the coordination of Antarctic activities and the exchange of information among the Antarctic community. By facilitating communication among Treaty Parties, particularly through the EIES, the Secretariat has provided vital logistical and administrative support for the organisation of inspections, the submission and circulation of information, and the timely sharing of scientific and operational data (Barrett, Reference Barrett2015). These efforts have enhanced mutual awareness, reduced duplication of activities, and contributed to more efficient and cooperative implementation of Treaty obligations (Vigni, Reference Vigni, Triggs and Riddel2007). The Secretariat thus has helped to foster a more integrated and collaborative Antarctic governance framework.

The Secretariat has also made significant progress in supporting multilingualism within the ATS. By coordinating the translation of key documents and meeting minutes into the four official languages of the ATS (i.e. English, French, Spanish, and Russian), it has helped foster greater inclusion and reduce language barriers to participation (Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, n.d.). This function is particularly valuable for non-English-speaking Parties, including several Latin American States, for whom access to timely and accurate translations is essential to effectively participate in deliberations and advance their national positions. Beyond its logistical value, this linguistic support strengthens diplomatic interaction and contributes to a more equitable and representative decision-making process. It affirms the multilateral nature of the regime and helps prevent the dominance of English-speaking delegations in defining the agenda and outcomes of negotiations. In this way, the Secretariat reinforces the legitimacy and accessibility of the ATS as a truly international governance framework.

The Secretariat has also taken modest but significant steps toward public engagement and outreach, consistent with broader expectations for transparency and accountability in international environmental governance. Through its official website, educational resources, and support for external initiatives such as public exhibitions, university collaborations, and the dissemination of key Treaty texts, the Secretariat has helped raise awareness of the ATS and its core principles among non-state actors, educators, researchers, and the public (ATCM, 2023). While its mandate does not extend to policy advocacy, its information dissemination activities have contributed to increasing the regime’s visibility and legitimacy. These efforts are particularly relevant at a time of growing global interest in Antarctica, where public perception and understanding can influence national policy priorities and international cooperation. By facilitating access to accurate and accessible materials, the Secretariat has supported the environmental and peaceful use objectives of the ATS beyond formal diplomatic channels.

These contributions demonstrate that even within a deliberately constrained institutional design, the Secretariat has added substantial and enduring value to the ATS. Although it was never intended to serve as a political or decision-making body, its administrative, technical, and procedural contributions have nonetheless shaped the day-to-day functioning and long-term resilience of the regime. By enhancing continuity of the regime, coordination among Parties, improving accessibility to information and historical records, standardising meeting practices, supporting multilingual engagement, and facilitating public outreach, the Secretariat has helped to consolidate the administrative and normative foundations of Antarctic governance. In doing so, it has quietly but effectively reinforced the legitimacy, transparency, and adaptability of a system that operates without a centralised enforcement authority or supranational oversight.

Limitations and structural constraints

Several factors limit and constrain the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat’s functions. Despite the significant contributions of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat over the past two decades, its relevance remains limited by several legal, financial, and political constraints. These constraints reflect both the Secretariat’s original design and the persistent political preferences of the Consultative Parties, many of which have always been cautious about empowering ATS institutions.

The Secretariat is not a separate legal subject from the ATCM. It is a subsidiary organ acting under the power of the ATCM (Article I Measure 1 (2003)). The Secretariat has no voice of its own. The Secretariat has no capacity to decide on its actions; its capacity is subject to the will of the ATCM. Its functions are limited to procedural support, document management, and information sharing. It is not authorised to interpret the Antarctic Treaty or Environmental Protocol provisions, monitor State behaviour, assess compliance, or drive policy development. The Secretariat cannot participate on behalf of the ATCM in meetings of other forums relevant to the Antarctic region, such as the United Nations Climate Change Conferences, without authorisation from the ATCM. This institutional minimalism was deliberately chosen to preserve the State-centric and consensus-based nature of the ATS, but it also prevents the Secretariat from making a more substantial contribution to governance challenges.

The Secretariat’s limited visibility and lack of public authority may reduce its potential to act as a catalyst for transparency and accountability. While it plays a valuable role in publishing ATCM and CEP documents, it lacks the mandate to synthesise information, issue reports, or facilitate greater civil society engagement in Antarctic governance. This reinforces a culture of insularity and limits the Secretariat’s ability to contribute to evolving expectations of environmental transparency and global institutional legitimacy.

Another important limitation is budgetary. The Secretariat is funded by contributions assessed by the Consultative Parties, following a UN scale with some adjustments. While the budget is sufficient to cover basic administrative functions, it remains modest compared to comparable international secretariats. This limited funding restricts the Secretariat’s ability to expand its staff, engage in long-term planning, or provide technical expertise beyond immediate operational needs. For example, at the last ATCM in Milan in 2025, several States raised concerns about financing Working Group Chairs through the Secretariat’s budget, given its already strained financial position (ATCM 2025a). The Secretariat’s reliance on State contributions not only exposes it to shifts in political will or economic downturns among major contributors but also constrains its operational independence and capacity to plan or act strategically. These financial limitations not only restrict the Secretariat’s operational capacity but also risk undermining its ability to effectively support and advance the objectives of the ATS.

The Secretariat’s role is also shaped by the political sensitivities of the ATCPs, particularly those wary of institutional expansion or centralisation. Any effort (even a modest one) to develop the Secretariat’s capacity beyond its original mandate faces political obstacles. Comparatively speaking, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat operates with fewer powers and resources than the secretariats of other multilateral environmental agreements, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or the Convention on Biological Diversity (Bauer, Reference Bauer2006; Scott, Reference Scott2003). While these bodies conduct technical assessments, convene expert groups, and contribute to political agenda-setting, the Antarctic Secretariat is not intended to play a leading role in policymaking or treaty implementation.

The Secretariat’s role is defined as much by what it cannot do as by what it can. While its minimalist design reflects the founding principles of the Antarctic Treaty, particularly the emphasis on consensus, decentralisation, and Consultative Parties-driven governance, it also constrains the regime’s institutional responsiveness. This limited mandate restricts the Secretariat’s ability to take proactive or independent action, whether in supporting scientific collaboration, enhancing compliance, or engaging with non-state actors. The functions (and limitations) of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat may hinder the ATS’s ability to evolve and remain effective in an era marked by intensifying environmental pressures, geopolitical competition, and shifting expectations of global environmental governance. The need to critically review these institutional constraints, how they are embedded in the current legal framework, and how they might be adjusted through incremental or formal reform, remains a key question for the future development of the Antarctic regime.

The Secretariat in a changing Antarctic context

As the Antarctic Treaty will very soon turn 70, the region faces several interrelated challenges that are placing increasing pressure on its institutional and legal architecture. Climate change, intensifying scientific and commercial interest in Antarctica, and the return of geopolitical rivalry to global affairs suggest that the ATS must be able not only to respect established rules but also to adapt to a more complex and dynamic governance landscape. In this changing context, the Secretariat, although originally conceived as a limited administrative body, could find itself playing a more central role in preserving the coherence and functionality of the regime.

Climate change is arguably the most pressing challenge facing the Antarctic region. The marine ecosystems of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean are already being significantly affected by rising global temperatures, ocean warming, and accelerating ice loss (Bracegirdle et al., Reference Bracegirdle, Krinner, Tonelli, Haumann, Naughten, Rackow and Wainer2020; Constable et al., Reference Constable, Melbourne-Thomas, Corney, Arrigo, Barbraud, Barnes and Costa2014). In addition to climate-driven changes, human activities such as scientific research, tourism, and fishing are placing increasing pressure on fragile polar ecosystems (Rayfuse, Reference Rayfuse2007). Given Antarctica’s fundamental role in the global climate system, understanding and addressing both climate change and broader human-induced impacts are of critical importance (Stephens, Reference Stephens2018). Growing scientific concern about potential tipping points further underscores the need for effective coordination among Parties and timely access to high-quality environmental data. Although the Secretariat does not have a scientific mandate, it is well placed to support the science–policy interface by assisting the CEP in synthesising scientific information, facilitating engagement with SCAR and other relevant institutions, and ensuring the integrity and accessibility of environmental reports. In this context, modest institutional enhancements, such as expanding its role in technical workshops and capacity-building activities, increasing funding and staff resources to enable greater continuity and responsiveness, and strengthening public outreach and knowledge dissemination, could significantly improve coordination within the ATS. Such measures would help bridge the gap between Antarctic diplomacy and the expectations of global civil society, while reinforcing evidence-based decision-making in the face of accelerating environmental change.

Geopolitical tensions are also testing Antarctic cooperation. The new post-Cold War international order creates unprecedented challenges for Antarctic governance (McGee et al., Reference McGee, Edmiston and Haward2022). In recent years, the ATCMs have experienced increasing difficulty in reaching consensus on key issues, such as granting Consultative Party status to Canada and Belarus (among others). There have been recent similar problems during 2023–2024 at the ATCM to reach consensus on granting emperor penguins Specially Protected Species status. Further, over the last decade, CCAMLR has failed to find consensus on three proposals for new marine protected areas in Antarctica aimed at helping the region better adjust to the impacts of climate change (McGee et al., Reference McGee, Arpi and Jackson2020). In this context, while the adoption of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) under the CCAMLR regime would fall outside its scope, the Secretariat’s role as a neutral facilitator to facilitate dialogue between Antarctic Treaty Parties may take on greater importance. Its ability to maintain institutional memory, provide consistent technical support, and act as a quiet stabilising force can help protect the regime from the most disruptive effects of global political rivalry.

The broader landscape of global environmental governance is evolving, with growing expectations for institutional transparency and accountability for international regimes such as the ATS. At the 2025 ATCM in Milan, the Netherlands, Australia, and South Korea jointly submitted a working paper calling for greater openness in Antarctic governance (ATCM, 2025b). The paper proposes a new model of transparency within the ATS, including the participation of civil society and media representatives in ATCM meetings. By promoting greater public oversight of state conduct, the proposal seeks to align ATCM practices with contemporary standards in international environmental governance. For example, the United Nations Climate Change Conferences routinely host thousands of civil society and media participants. In this context, the Secretariat may increasingly be expected to engage with actors beyond States, including NGOs, indigenous representatives, and other civil society organisations concerned with polar issues. While such engagement could mark a significant institutional evolution within the ATS, it also raises important questions about the Secretariat’s role and its capacity to operate effectively under these expanded expectations. Increasing transparency in ATCM (and CCAMLR meetings), particularly regarding decision-making processes, could serve two important functions (Arpi et al., Reference Arpi, McGee and Press2025). It would allow other states, international organisations, civil society, academia, scientists, and the media to gain a clearer understanding of which actors are facilitating or impeding progress on key issues. At the same time, it could help build greater public and stakeholder confidence in ATS institutions at a time when trust in multilateral governance is waning. Enhancing transparency would not only improve accountability but also strengthen the legitimacy and effectiveness of Antarctic governance.

Looking ahead, the Secretariat’s future role will depend on both political will and institutional creativity. Modest reforms, such as improving its capacity to support data synthesis, facilitating technical workshops, or expanding dissemination, could significantly enhance its contribution without challenging the power of the ATCM or decision-making authority of the ATCPs. More ambitious proposals, such as granting the Secretariat a monitoring or compliance support role, would require revisiting the fundamental principles of the ATS. Such proposals are likely to be politically contentious, reigniting original concerns about establishing a stronger central body and making consensus difficult to achieve. However, the ongoing evolution of global environmental standards and governance expectations suggests that some degree of institutional adaptation will be necessary to maintain the ATS’s legitimacy and effectiveness. By carefully balancing its limited mandate with targeted institutional innovation, the Secretariat can continue to act as a central facilitator of coordination, accountability, and scientific and policy integration, ensuring that the ATS remains robust, responsive, and legitimate in the face of 21st-century challenges. Ultimately, a well-supported Secretariat is not only essential for day-to-day administration but also for safeguarding the long-term stability and credibility of Antarctic governance as a model of effective multilateral cooperation.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Professor Jeff McGee for valuable comments on an earlier draft and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.