Highlights

-

• Bilinguals distinguished animacy of words in a target language.

-

• ERP lexical frequency effects were reduced in the nontarget language.

-

• ERP semantic concreteness effects were eliminated in the nontarget language.

-

• The proportion of each language present did not affect language suppression.

-

• Findings support the partial selectivity hypothesis of bilingual language control.

1. Introduction

Bilinguals navigate a variety of linguistic contexts throughout their lives, which creates the need to monitor which language is relevant in the current context in order to communicate appropriately with interlocutors. Although in some cases both languages may be used, such as in a dense code-switching context, in other cases bilinguals need to select just one of their languages to use, for example, when speaking to a monolingual or a bilingual with whom they share only one language. Prior research has investigated this language selection largely in the realm of language production (Kroll et al., Reference Kroll, Bobb and Wodniecka2006) but has often assumed that language selection is not necessary in comprehension because the input alone can drive activations in a bottom-up fashion (Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra and van Heuven2002; Dijkstra & van Hell, Reference Dijkstra and van Hell2003). Yet restricting activation to a currently relevant target language during comprehension may be more efficient, and some recent research suggests that language control mechanisms indeed operate during comprehension (Elston-Güttler et al., Reference Elston-Güttler, Paulmann and Kotz2005; Elston-Güttler & Gunter, Reference Elston-Güttler and Gunter2009; FitzPatrick & Indefrey, Reference FitzPatrick and Indefrey2010; FitzPatrick & Indefrey, Reference FitzPatrick and Indefrey2014; Mercier et al., Reference Mercier, Pivneva and Titone2014; Hoversten & Traxler, Reference Hoversten and Traxler2020; Hoversten & Martin, Reference Hoversten and Martin2023; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Negron and Scholl2025). However, we do not yet fully understand how the bilingual brain selects the appropriate language for the current context during comprehension.

One major question related to the issue of language selection and control is whether the target and nontarget languages are activated in parallel (nonselective access) or not (selective access). A large body of studies have demonstrated a clear influence of the nontarget language during target language processing (see Kroll, Reference Kroll2024, for a recent review). As such, the field has settled on a fundamentally nonselective view in which both languages are activated in parallel, and selection happens based on the similarity of the input to lexical representations stored in long-term memory. The most widely supported models of word recognition, BIA, BIA+ and Multilink, incorporate such a nonselective architecture in which representations are largely activated in a bottom-up manner (Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra, van Heuven, Grainger and Jacobs1998, Reference Dijkstra and van Heuven2002, Reference Dijkstra and van Heuven2013; Dijkstra et al., Reference Dijkstra, Wahl, Buytenhuijs, van Halem, Al-Jibouri, de Korte and Rekké2019). Although the original BIA model incorporated some top-down control from language nodes to inhibit lexical representations in the opposite language, the updated BIA+ and subsequent models have removed this top-down control of lexico-semantic processing in favor of an external task/decision system that operates solely on the output of the word recognition system to implement a current task goal such as lexical decision (Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra and van Heuven2002).

While a host of research supports the idea that the word recognition system is permeable to the nontarget language, this need not preclude at least some degree of top-down control of the nontarget language. In fact, recent work has shown evidence that activations of representations belonging to the target and nontarget languages may not be an all-or-none process. In other words, representations may become activated selectively or nonselectively to different degrees depending on the particular context and task demands. For example, Hoversten & Traxler (Reference Hoversten and Traxler2020) presented Spanish–English bilinguals with intrasentential code-switches during natural reading. Skip rates and reading times were intermediate between those of non-switches and pseudowords when code-switches were presented overtly, with increasing skip rates as more code-switches were presented over the course of the experiment. When the same code-switches were presented covertly through parafoveal preview and replaced with a non-switch to mimic a monolingual language context, they elicited no more skipping than pseudowords did. These results demonstrate a clear influence of global language context on the degree of activation of each language during natural reading, beginning from the earliest stages of word recognition indexed by skip rate. Yet, the question of the degree of selectivity is severely under-researched, including which factors drive different degrees of selectivity as well as which linguistic levels of abstraction (e.g., sublexical, lexical, semantic) are affected by language control during comprehension.

1.1. Dual task paradigm

One way to investigate these questions is through the dual task paradigm, in which bilinguals simultaneously categorize words according to language membership and semantic meaning during electroencephalography (EEG) recording (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015; Ng & Wicha, Reference Ng and Wicha2013; Rodriguez-Fornells et al., Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002; Yiu et al., Reference Yiu, Pitts and Canseco-Gonzalez2015). These studies create a target and a nontarget language through Go/No-Go task instructions: respond to only one of the two languages. The additional semantic categorization task is implemented as a button press response: for example, respond with the left hand for words representing living things and with the right hand for nonliving things. The semantic categorization task ensures that participants fully process the stimuli, at least in the target language. During analysis, event-related potentials (ERPs) are extracted from the EEG signal to establish when the brain implements each type of categorization and how deeply words are processed in each condition.

Using this paradigm, research has demonstrated surprisingly early identification of language membership information: within 200–300 ms of stimulus presentation and approximately 100 ms prior to the semantic categorization operation in this task (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015, Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2017; Yiu et al., Reference Yiu, Pitts and Canseco-Gonzalez2015). Furthermore, by additionally manipulating word frequency in both languages, the paradigm has revealed decreased frequency effects (i.e., differences in the N400 ERP component between high- and low-frequency words; Rugg, Reference Rugg1990) in the nontarget language compared to the target language, reflecting shallower lexical processing in the nontarget language (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015; Rodriguez-Fornells, Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002). Overall, these results demonstrate that bilinguals quickly identify the language to which a word belongs and can use this information to suppress (at least partly) a task-irrelevant language.Footnote 1 Different studies, however, have shown different degrees of processing in the nontarget language, with one study showing a complete absence of frequency effects (Rodriguez-Fornells et al., Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002) and another study showing decreased but not absent frequency effects in the nontarget language (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015). Yet another study did not report the interaction between target and nontarget frequency effects, though it appears to follow the pattern of partially decreased effects in the nontarget language based on visual inspection (see Ng & Wicha, Reference Ng and Wicha2013, figures 3 and 4). Thus, the extent of processing in the nontarget language requires further investigation, given that selective versus partially selective lexical access is a fundamental distinction for modeling bilingual word recognition processes.

1.2. Adaptive control across populations

One possible explanation of these differences across studies could lie in the adaptive control hypothesis (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013). This hypothesis proposes that bilinguals who engage in different types of interactional contexts in their daily lives will develop and utilize different language control mechanisms (see also Beatty-Martinez et al., Reference Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2020). Rodriguez-Fornells et al. (Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002) studied early, balanced Spanish–Catalan bilinguals who grew up in a community in which both of their languages are highly prevalent, and they found evidence for complete suppression of the nontarget language. Both Hoversten et al. (Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015) and Ng & Wicha (Reference Ng and Wicha2013), on the other hand, studied Spanish–English heritage bilinguals living in a community in which the majority language was their second language (L2), English, and found partial suppression of the nontarget language. It is possible that the differences between studies could be attributed to the language history profile of participants, with more experience with dual language contexts (e.g., both languages highly prevalent throughout the community) leading to stronger suppression of a task-irrelevant language, and more experience with single language contexts (e.g., Spanish at home and English at school/work) leading to weaker suppression of a task-irrelevant language when both are present. However, the degree of language suppression in comprehension has not been well investigated across different populations, so further research is needed to establish whether these patterns of effects replicate in other bilingual populations and language pairs.

1.3. Locus of language control

In addition to the extent of nontarget language processing, the locus of language control has not been thoroughly investigated in comprehension. Most models of language processing posit a number of different levels of abstraction, namely sublexical, lexical and semantic (e.g., Grainger & Ziegler, Reference Grainger and Ziegler2011; McClelland & Rumelhart, Reference McClelland and Rumelhart1981). Current views suggest that activations pass through these different representational levels in a cascaded and interactive fashion, from initial visual or auditory processing all the way to deep semantic processing of a word. Although multiple loci of language control have been posited in bilingual production research (Kroll et al., Reference Kroll, Bobb and Wodniecka2006; Declerck & Phillip, Reference Declerck and Philipp2015), this issue has received very little attention in bilingual comprehension research. Current models such as BIA+ and Multilink assume that language control is exerted entirely outside the lexicon, operating on the output of the word recognition system alone.

However, recent studies demonstrate that the bilingual brain can in fact exert language control on the lexico-semantic processing stream itself (e.g., Fitzpatrick & Indefrey, Reference FitzPatrick and Indefrey2014; Hoversten & Traxler, Reference Hoversten and Traxler2020; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Negron and Scholl2025). For example, Fitzpatrick & Indefrey (Reference FitzPatrick and Indefrey2014) showed delayed lexical processing of intrasentential code-switches and nontarget meanings of interlingual homographs in the ERP signal, suggesting that words in the target language enjoy a “head start” in processing compared to words in the nontarget language. Hoversten & Martin (Reference Hoversten and Martin2023) showed that bilinguals demonstrate within but not cross-language semantic preview benefits during natural reading, despite the fact that translation previews were more semantically similar to target words than within-language synonym previews were. Finally, Schwartz et al. (Reference Schwartz, Negron and Scholl2025) showed that color coding text in each language can reduce switch costs in early eye-tracking measures during natural reading, suggesting that nonlinguistic cues can directly influence activation dynamics within the bilingual lexicon. However, very little work thus far has systematically investigated exactly which representational levels inside the lexicon are affected by language control in bilingual comprehension.

1.4. Language mode

Another possible moderator of the degree and locus of language control is the language mode, or the contextual relevance of each language along a continuum from monolingual, in which only one language is relevant, to bilingual, in which both languages are relevant (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean and Nicol2001). Some studies have shown that language mode may indeed influence the global activation of each language (Dunn & Fox Tree, Reference Dunn and Fox Tree2014; Elston-Güttler et al., Reference Elston-Güttler, Paulmann and Kotz2005, Elston-Güttler & Gunter, Reference Elston-Güttler and Gunter2009; FitzPatrick & Indefrey, Reference FitzPatrick and Indefrey2014; Hoversten & Traxler, Reference Hoversten and Traxler2020; Mercier et al., Reference Mercier, Pivneva and Titone2014). For example, Elston-Güttler et al. (Reference Elston-Güttler, Paulmann and Kotz2005) showed ERP evidence of selective activation of the target language meaning of a sentence-final interlingual homograph when the experiment was preceded by a video in the target language but showed nonselective activation (in the first half of the experiment only) when preceded by a video in the nontarget language. The authors suggest that participants “zoomed into” the target language over time with increasing exposure to it. On the other hand, several studies have shown no effect of language mode (e.g., De Groot et al., Reference De Groot, Delmaar and Lupker2000; Dijsktra & van Hell, Reference Dijkstra and van Hell2003, Paulmann et al., Reference Paulmann, Elston-Güttler, Gunter and Kotz2006). For example, Paulmann et al. (Reference Paulmann, Elston-Güttler, Gunter and Kotz2006) tested the same paradigm and word stimuli as Elston-Güttler et al. (Reference Elston-Güttler, Paulmann and Kotz2005), except that interlingual homographs were not embedded in sentences. In contrast to the sentence reading experiment, they found evidence of nonselective activation of both meanings of interlingual homographs regardless of the video context preceding the experiment. Thus, further investigation is required across various tasks and methods to tease apart when and how language mode might affect language control in comprehension.

1.5. Current study

In summary, we do not yet know what representational levels (e.g., lexical, semantic) are influenced by language control (e.g., suppression of the task-irrelevant nontarget language) or whether the degree of processing differs across these representational levels. Furthermore, we do not know whether bilingual populations with different language history profiles will exhibit similar effects as prior studies, showing partially or fully selective access depending on how frequently bilinguals use their languages separately or together in the same communicative context. Nor do we know how the proportion of each language presented (i.e., the language mode) might influence nontarget language suppression. Therefore, the goal of the current study was to further specify the locus of nontarget language suppression in bilingual language comprehension in a new population based on task demands and language mode.

We used the same dual task paradigm during EEG recording as the prior studies described above, in which one language served as the target “Go” language, while the other language served as the nontarget “No-Go” language, and response hand was determined by animacy. Critically, we orthogonally manipulated frequency and concreteness of words across target and nontarget languages. As described above, lower frequency words typically produce a more negative ERP signal than higher frequency words across centroparietal electrodes (i.e., a frequency effect; Rugg, Reference Rugg1990). Similarly, concrete words produce a more negative ERP signal than abstract words across frontal electrodes (i.e., a concreteness effect; Kounios & Holcomb, Reference Kounios and Holcomb1994). We follow prior research in considering frequency effects to reflect lexical processing (Baayen et al., Reference Baayen, Milin and Ramscar2016; Cuetos et al., Reference Cuetos, Glez-Nosti, Barbón and Brysbaert2009; Inhoff & Rayner, Reference Inhoff and Rayner1986; Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Ashby, Pollatsek and Reichle2004) and concreteness effects to reflect semantic processing (Binder et al., Reference Binder, Westbury, McKiernan, Possing and Medler2005; Holcomb et al, Reference Holcomb, Kounios, Anderson and West1999). In order to further explore the role of language history profile, we tested frequency and concreteness effects in the ERP signal in a novel population of early balanced Spanish–Basque bilinguals living in the Basque Country of Spain, in which both languages are highly prevalent in the community. Finally, in order to simulate more bilingual or monolingual language modes, we manipulated the proportion of each language presented across blocks – either a 1:1 ratio of each language as in prior studies or a 7:1 ratio of target to nontarget language words.

1.6. Predictions

If task demands indeed enable nontarget language suppression as found in prior studies, we expect to find reduced frequency and/or concreteness effects in the nontarget language. A partially selective view would predict reduced but not eliminated effects (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015), whereas a fully selective view would predict eliminated effects (Rodriguez-Fornells et al., Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002). The adaptive control hypothesis would predict that results with the current population would more closely align with those of Rodriguez-Fornells et al. (Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002), that is, early balanced Spanish–Catalan bilinguals living in a bilingual environment. On the other hand, a fully nonselective view such as the BIA+ model would predict no differences between target and nontarget languages in frequency and concreteness effects (Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra and van Heuven2002). Instead, language control based on task demands would be implemented outside of the lexicon and operate solely on the output of the word recognition system rather than on activation dynamics within the lexicon itself and therefore would not affect these lexico-semantic variables.

We may also find different magnitudes of effects across frequency and concreteness manipulations, as these are hypothesized to reflect distinct levels of processing (e.g., lexical vs. semantic, respectively). Such a result might suggest that language control differentially affects loci across these linguistic levels. For example, task demands may enable the system to suppress the nontarget language such that representations are activated in a partially selective manner at the lexical level (i.e., reduced but not eliminated frequency effects in the nontarget language) and a fully selective manner at the semantic level (i.e., eliminated concreteness effects in the nontarget language). Such a result might imply an underlying mechanism of language control that allows some shallow processing of words belonging to the nontarget language but prevents deep semantic processing.

Finally, if language mode affects language control in this task, we predict increased suppression in the 7:1 block compared to the 1:1 block due to zooming in on the target language in the former. Note that the opposite effect is also possible: the 7:1 block mimicking a more monolingual language mode may require less monitoring and control of the nontarget language due to higher activation of the target language, which would produce less suppression in the 7:1 versus 1:1 blocks. Either way, the language mode hypothesis would predict differential degrees of suppression of the nontarget language across the proportion manipulation. Therefore, the study was designed to disentangle questions about the degree and locus of language control in word recognition, as well as the influence of language history and language mode on such language control, in order to further specify the neurocognitive mechanisms of bilingual lexico-semantic processing during comprehension.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Fifty-two Spanish–Basque young adult (18–40 years) bilinguals gave written, informed consent and were paid to participate according to the ethical standards of the institutional committee on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. After subject exclusions (three participants completed only one session and three participants had excessive artifact such that less than half of trials remained for analysis after exclusion procedures described below), 46 participants were included in the final sample (age: M = 31, SD = 6.1; female = 41). All participants were right-handed highly proficient users of both Spanish and Basque based on a battery of assessments in each language, including verbal interviews, lexical decision tasks (LexTALE: Lemhöfer & Broersma, Reference Lemhöfer and Broersma2012), naming tasks (BEST; De Bruin et al., Reference De Bruin, Carreiras and Duñabeitia2017) and a language history questionnaire (Table 1). None of the participants had a history of neurological, psychiatric or language-related disorders.

Table 1. Participants’ language proficiency data means and standard deviations

2.2. Stimuli

We selected 576 nouns, half of which were Basque and half Spanish. Half of the stimuli in each language were living (e.g., dog, secretary) and half nonliving (e.g., table, beach). We excluded language-ambiguous stimuli like cognates and interlingual homographs, as well as Spanish words with accents that would provide low-level visual cues as to the language membership of the word. Words in each category (Spanish/Basque, living/nonliving) were matched on length, log frequency per million (B-Pal Spanish database, Davis & Perea, Reference Davis and Perea2005; E-Hitz Basque database, Perea et al., Reference Perea, Urkia, Davis, Agirre, Laseka and Carreiras2006), concreteness (BaSp database, Duñabeitia et al., Reference Duñabeitia, Casaponsa, Dimitropoulou, Martí, Larraza and Carreiras2017) and orthographic neighborhood density (Table 2). We orthogonally manipulated concreteness and frequency in each of the four categories (Spanish living, Basque living, Spanish nonliving, Basque nonliving) with a median split on each variable, ensuring that stimuli were matched on all other stimuli characteristics across high and low values (ps > .23).

Table 2. Stimuli characteristics across orthogonal median splits (bolded) of frequency and concreteness (middle), languages and animacy categories (left) and filler words (right). Freq. = frequency (log/million), Conc. = concreteness, Len. = length, N = neighborhood density.

In addition, we chose 432 filler stimuli per language, half living and half nonliving to create the proportion manipulation (see explanation below). Although these stimuli were not analyzed since they were not precisely matched to the critical stimuli, they had similar lexical characteristics.

2.3. Procedure

Each participant completed two separate sessions between 3 and 7 days apart. In each session, one language was the target language, and the other language was the nontarget language. The experimenter always spoke to participants in the target language for that session in order to maintain a reliable target language throughout the session.

In each session, EEG was recorded while stimuli were presented serially in white uppercase size 20 Calibri font between two horizontal lines in the center of the screen with a black background. Each word was presented for 400 ms with a jittered interval of 1750–2100 ms between stimuli. A fixation cross appeared between the lines for 1000 ms at the beginning of each section of the experiment and after every third stimulus, during which participants were instructed to blink. After each fixation cross, the horizontal lines remained on the screen for 1500 ms before the beginning of the next trial.

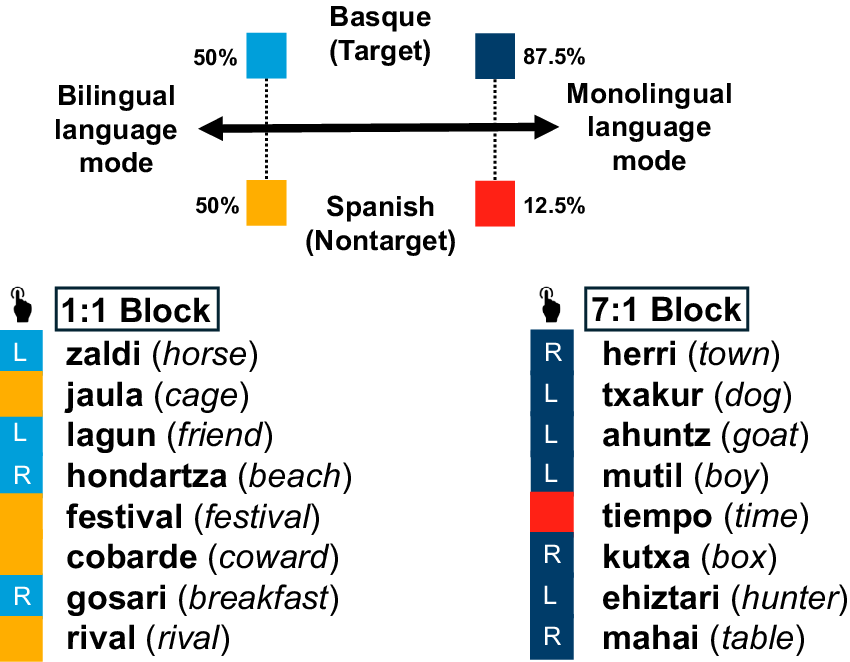

Participants performed language membership and animacy categorization tasks on each word, with instructions to perform the classifications simultaneously as quickly and accurately as possible (Figure 1). A Go or No-Go response decision was made based on language membership information (Spanish or Basque), creating a target and a nontarget language. A left or right response hand decision was made based on animacy information (living or nonliving), which was counterbalanced across blocks. The inclusion of the semantic classification task was necessary in order to force semantic processing of words, at least in the target language.

Figure 1. The proportion of each language was manipulated across blocks to mimic more bilingual or monolingual language modes. Button press response hand is given for an example block in which Basque is the target language, the right hand (R) is used to respond to nonliving nouns and the left hand (L) is used to respond to living nouns. English translations of example stimuli are listed in italics.

Of the 576 total critical stimuli, 288 were presented in each session. These stimuli were then separated into four blocks per session, with 12 practice trials at the beginning of each block and rest breaks between blocks. Across two of these blocks, we presented 72 critical stimuli per language without fillers, such that 50% of the stimuli belonged to the target language and 50% belonged to the nontarget language (1:1 ratio; Figure 1). Across the other two blocks, we presented 72 critical stimuli per language along with 432 fillers in the target language, such that 87.5% of the total stimuli belonged to the target language and 12.5% belonged to the nontarget language (7:1 ratio; Figure 1). Each participant performed all combinations of the task, counterbalancing response hand and target language across blocks and sessions. Across participants, we counterbalanced the order of target languages, response hand, and proportion manipulation for each of the 576 critical stimuli.

2.4. Recording

The electroencephalogram (EEG) signal was recorded using a BrainAmp system at a sampling rate of 500 Hz from 27 scalp electrodes mounted in an Activecap elastic recording cap (Brain Products GmBH). Additional electrodes were attached to the mastoids to serve as references and below and to the side of each eye to monitor blinks and eye movements. Electrodes were referenced online to the right mastoid and re-referenced offline to the average of the left and right mastoids. Electrode impedances were lowered below 10 kΩ.

The EEG data were filtered with a 0.05–30 Hz band-pass filter (24 dB/octave), and 1200-ms epochs were extracted, time-locked to the presentation of each stimulus with a 200-ms pre-stimulus baseline. Incorrect trials were removed (7% of data). Independent component analysis was then used to isolate and remove any blink and saccade components in the data (Makeig et al., Reference Makeig, Bell, Jung and Sejnowski1996). Single-trial waveforms were then screened for remaining blink or eye movement artifacts, amplifier drift, or muscle artifacts (> ±100 μV) and removed as needed (2.6% of data). After processing, all conditions for each participant contained at least 36 trials for analysis (M = 64 trials/condition/participant).

2.5. Analysis

EEG epochs were averaged in each condition to compute ERPs, and analyses were conducted on individual subject ERP mean amplitudes in a given time window. A Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to analyses with more than one degree of freedom to meet the assumption of sphericity. RM-ANOVAs were performed on behavioral accuracy and on ERPs using SPSS (version 19) with experimental factors of Language (Target vs. Nontarget), Proportion (1:1 vs. 7:1) and either Frequency or Concreteness (High vs. Low). Frequency and Concreteness effects were analyzed separately since these factors were orthogonally manipulated in the stimuli set to allow for sufficient power to detect interactions of theoretical interest. To probe the scalp distribution of effects, analyses included two topographical factors: Anteriority (Anterior, Central, Posterior) and Laterality (Left, Middle, Right), generating nine clusters of electrode sites (Left Anterior [F3, F7, FC5], Left Central [C3, T7, CP5], Left Posterior [P3, P7], Medial Anterior [Fp1, Fp2, Fz, FC1/2], Medial Central [Cz, CP1/2], Medial Posterior [Pz, O1/2], Right Anterior [F4, F8, FC6], Right Central [C4, T8, CP6] and Right Posterior [P4, P8]).

We focused on the highest order interaction(s) between experimental factors of interest in each model. Effects of topographic factors are reported only when they interact with a factor of interest, and main effects are only reported if they are not qualified by a higher order interaction with that term. We followed up effects of theoretical interest by zooming into the topographic region of interest (ROI) for each type of effect: a frontal cluster of electrodes (FP1/2, Fz, F3/4, F7/8, FC1/2, FC5/6) where concreteness effects tend to emerge (Kounios & Holcomb, Reference Kounios and Holcomb1994) and a centroparietal cluster (Cz, CP1/2, Pz, P3/4, O1/2) where frequency effects are typically maximal (Rugg, Reference Rugg1990). We also split the data set according to one of the experimental factors involved in the critical theoretical interaction by examining effects in the target and nontarget languages separately. Additionally, condition means are reported with within-subject standard errors (Morey, Reference Morey2008 correction). See OSF page (https://osf.io/3quxj/) for the full results of each model reporting all main effects and interactions.

3. Results

We first report behavioral results of task performance, followed by the results of ERP mean amplitude analyses below. Participants performed well on the task in all conditions (M = 93% accuracy). However, low-frequency words elicited higher error rates (9%) than high-frequency words (6%) (F (1, 45) = 48.8, p < .001), and abstract words elicited higher error rates (8%) than concrete words (%) (F (1, 45) = 11.8, p = .001). In addition, the interaction between Frequency and Target Language was significant (F (1, 45) = 16.7, p < .001), whereby low-frequency words were more likely to elicit errors in Go trials (11%) than in No-Go trials (7%), but high-frequency words elicited approximately equal errors in Go trials (6%) and No-Go trials (7%). The interaction between Proportion and Target Language was also significant (concreteness analysis: F (1, 45) = 88.8, p < .001; frequency analysis: F (1, 45) = 84.4, p < .001), whereby No-Go trials elicited more errors in the 7:1 block (9%) than in the 1:1 block (3%), but Go trials elicited more errors in the 1:1 block (9%) than in the 7:1 block (7%).

In the grand average ERP waveforms, typical early visual components emerged prior to P2 and N400 components. Across both 1:1 and 7:1 blocks, the Target language (Go) category elicited more positive amplitudes than the Nontarget language (No-Go) category, beginning around 300 ms post-stimulus onset (Figure 2). This effect was likely driven by an enhanced inhibitory N2 for No-Go stimuli as well as an enhanced target P3 for Go stimuli (Folstein & van Petten, Reference Folstein and Van Petten2008). Rare No-Go stimuli in the 7:1 blocks also elicited an enhanced positivity relative to No-Go stimuli in the 1:1 blocks, which represents a classic oddball P3 elicited by rare stimuli that has been found in a variety of oddball tasks in prior studies (e.g., Debener et al., Reference Debener, Makeig, Delorme and Engel2005 in auditory perception; Luck et al., Reference Luck, Kappenman, Fuller, Robinson, Summerfelt and Gold2009 in visual perception; Hoversten & Traxler, Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2017 in bilingual language processing). As effects of theoretical interest should manifest on top of these general Go/No-Go task-related ERPs, we report but do not discuss in detail any results that solely reflect the N2/P3 complex without affecting the critical language control task manipulation (Target Language × Frequency/Concreteness).

Figure 2. A Nontarget (No-Go) language N2 and a Target (Go) language P3 emerged across both the 1:1 block and the 7:1 block. Rare Nontarget language stimuli in the 7:1 block also elicited an oddball P3. Raw waveforms recorded at representative anterior (Fz) and posterior (Pz) electrode sites, and the corresponding scalp topographies are shown.

3.1. Frequency ERPs

Based on visual inspection, frequency effects emerged across a broad time window spanning 200–800 ms and across a broad topographic region of the scalp, though most strongly in our centroparietal ROI (Figure 3). In order to investigate whether task demands and proportion differentially affected lexical access across this broad time course, we analyzed mean ERP amplitudes in an earlier (200–500 ms) and later (500–800 ms) time window for High- and Low-Frequency words by Target Language (Go vs. No Go) and Proportion (1:1 vs. 7:1). In each window, we first report whole head analyses including the topographic factors Anteriority and Laterality, with follow-up analyses in the centroparietal ROI.

Figure 3. Frequency effects emerged in both languages but were smaller in the Nontarget (No-Go) than in the Target (Go) language. Raw waveforms of High- and Low-frequency stimuli across Target and Nontarget languages at a representative posterior electrode site (Pz) are displayed on the left. Topographic scalp distributions of the frequency effect in each language between 200 and 800 ms are displayed in the middle. High–Low-frequency difference waves in each language at electrode Pz are displayed on the right. Effects are collapsed across the Proportion manipulation because it did not significantly affect the critical indices of language control (Target Language × Frequency).

3.1.1. 200–500 ms Early window

This analysis revealed several significant three-way interactions: Frequency by Anteriority by Laterality (F (2.9, 132.8) = 5.4, p = .002, MSE = .09, ηₚ2 = .11), Target Language by Anteriority by Laterality (F (3.4, 151.5) = 4.1, p = .005, MSE = .08, ηₚ2 = .08), Frequency by Proportion by Laterality (F (1.8, 81.3) = 4.1, p = .023, MSE = .30, ηₚ2 = .08) and Target Language by Proportion by Laterality (F (1.6, 73.9) = 4.2, p = .025, MSE = .44, ηₚ2 = .09). Both Frequency and Target Language effects emerged most strongly in our centroparietal ROI in this time window. Frequency effects were slightly left-lateralized in the 7:1 blocks but slightly right-lateralized in the 1:1 block. Additionally, the Target Language effect was more right-lateralized in the 1:1 blocks than the 7:1 block. None of these interactions, however, answer our theoretical question of interest about the effect of Target Language on Frequency.

Critically, a theoretical effect of interest emerged in a significant two-way interaction between Target Language and Frequency (F (1, 45) = 4.9, p = .032, MSE = 8.6, ηₚ2 = .10), whereby frequency effects were smaller in the No-Go compared to the Go language. To follow up this two-way interaction, we considered Go and No-Go languages separately in the centroparietal ROI in which both of these effects were largest.Footnote 2 We found significant Frequency effects in both the Go language (F (1, 45) = 51.4, p < .001, MSE = 1.2, ηₚ2 = .53) and the No-Go language (F (1, 45) = 12.7, p = .001, MSE = 1.43, ηₚ2 = .22). However, effects were nearly twice the size in the Go language (M = 1.1 μV, SEM = .16) compared to the No-Go language (M = .60 μV, SEM = .18). While Proportion significantly affected mean amplitudes in this window, it did not differentially affect the critical Frequency manipulation across the two languages.

3.1.2. 500–800 ms Late window

This analysis revealed a significant four-way interaction among Target Language, Proportion, Anteriority and Laterality (F (3.1, 140.8) = 8.2, p < .001, MSE = .15, ηₚ2 = .15), reflecting the Go language P3 across both Proportions with an additional oddball P3 in the No-Go language discussed above. Critically, we also found a significant four-way interaction among Target Language, Frequency, Anteriority and Laterality (F (3.0, 135.3) = 2.7, p = .046, MSE = .10, ηₚ2 = .06), whereby Frequency effects were smaller in the No-Go compared to the Go language, particularly at centroparietal electrode sites. To follow up this theoretically interesting four-way interaction, we considered Go and No-Go languages separately in the centroparietal ROI where effects were largest. We found significant Frequency effects in both the Go language (F (1, 45) = 48.9, p < .001, MSE = 1.93, ηₚ2 = .52) and the No-Go language (F (1, 45) = 20.3, p < .001, MSE = 2.15, ηₚ2 = .31). As in the earlier time window, effects were larger in the Go language (M = 1.4 μV, SEM = .20) than in the No-Go language (M = 1.0 μV, SEM = .22). We also found a significant main effect of Proportion in the No-Go language only (F (1, 45) = 31.3, p < .001, MSE = 2.87, ηₚ2 = .41), whereby mean amplitudes were more positive in the 7:1 blocks (M = 5.2 μV, SEM = .25) compared to the 1:1 blocks (M = 3.8 μV, SEM = .25), again reflecting the large oddball P3 in this condition. Critically, Proportion did not interact with Frequency effects in either language.

3.1.3. Summary of effects of theoretical interest

Frequency effects were significantly diminished in the No-Go language relative to the Go language in both 200–500 and 500–800 ms time windows, regardless of the proportion of each language present. However, frequency effects still significantly differed from zero even in the No-Go language.

3.2. Concreteness ERPs

Based on visual inspection, concreteness effects also spanned a broad time window, though slightly later than the frequency effects (300–800 ms), and were mainly present across frontal electrode sites in concert with our topographic ROI (Figure 4). In order to investigate the effects of task demands and proportion on semantic access across this broad time window, we analyzed the mean ERP amplitudes in an earlier (300–500 ms) and later (500–800 ms) time window for Concrete and Abstract words by Target Language (Go vs. No-Go) and Proportion (1:1 vs. 7:1). In each window, we first report whole head analyses including the topographic factors Anteriority and Laterality, with follow-up analyses in the frontal ROI.

Figure 4. Concreteness effects emerged in the Target (Go) language but not in the Nontarget (No-Go) language. Raw waveforms of concrete and abstract stimuli across Target and Nontarget languages at a representative anterior electrode site (Fz) are displayed on the left. Topographic scalp distributions of the concreteness effect in each language between 300 and 800 ms are displayed in the middle. Concrete minus abstract difference waves in each language at electrode Fz are displayed on the right. Effects are collapsed across the Proportion manipulation because it did not significantly affect the critical indices of language control (Target Language × Concreteness).

3.2.1. 300–500 ms Early window

This analysis revealed a significant five-way interaction among all factors: Target Language, Concreteness, Proportion, Laterality and Anteriority (F (3.2, 148.0) = 2.9, p = .031, MSE = .09, ηₚ2 = .06). The Anteriority and Laterality factor involvement in this interaction reflects that Concreteness effects were indeed largest in our frontal ROI, as expected. Concreteness effects were also larger in the Go language (M = .60 μV, SEM = .17) than in the No-Go language (M = .15 μV, SEM = .14). We, therefore, followed up this interaction by considering Go and No-Go languages separately in the frontal ROI. In the Go language, we found only a main effect of Concreteness (F (1, 45) = 12.3, p = .001, MSE = 1.33, ηₚ2 = .22), and no interaction with Proportion (F (1, 45) = 1.9, p = .18, MSE = .89, ηₚ2 = .04). In the No-Go language, we did not find a main effect of Concreteness (F (1, 45) = 1.2, p = .27, MSE = .92, ηₚ2 = .03), nor an interaction between Concreteness and Proportion (F (1, 45) = 1.5, p = .24, MSE = .80, ηₚ2 = .03).

3.2.2. 500–800 ms Late window

The analysis in this later time window yielded a significant four-way interaction among Target Language, Proportion, Laterality and Anteriority (F (3.1, 141.0) = 8.1, p < .001, MSE = .16, ηₚ2 = .15), again reflecting the more positive mean amplitudes for the Go than the No-Go language at right and posterior sites in the 1:1 blocks but more positive mean amplitudes for the No-Go than the Go language at anterior sites in the 7:1 blocks, respectively reflecting the target P3 and oddball P3 effects discussed above. Nonetheless, our critical manipulation of Concreteness did not interact with these factors.

The next highest order interactions included several three-way interactions: Concreteness, Laterality and Anteriority (F (3.5, 155.5) = 3.2, p = .020, MSE = .10, ηₚ2 = .07), Target Language, Laterality and Anteriority (F (2.9, 132.0) = 24.1, p < .001, MSE = .48, ηₚ2 = .35), Target Language, Proportion and Anteriority (F (2.0, 88.6) = 7.2, p = .001, MSE = .59, ηₚ2 = .14), and Target, Concreteness and Anteriority (F (1.6, 71.6) = 4.0, p = .032, MSE = .60, ηₚ2 = .08). Concreteness effects were largest over our frontal ROI, while Target Language effects were largest over left posterior sites in this window. While Proportion significantly affected mean amplitudes in this window due to the large oddball P3 in the No-Go condition, importantly it did not significantly interact with effects of Concreteness at any order of interaction.Footnote 3

To follow up the theoretically interesting interaction of Target Language, Concreteness and Anteriority, we considered Go and No-Go languages separately in the frontal ROI where effects were largest. As in the earlier time window, Concreteness effects in the frontal ROI were larger in the Go language (M = .61 μV, SEM = .19) than in the No-Go language (M = .04 μV, SEM = .14). In the Go language, we found a significant main effect of Concreteness (F (1, 45) = 9.63, p = .003, MSE = 1.73, ηₚ2 = .18), but no interaction with Proportion (F (1, 45) = .80, p = .38, MSE = .97, ηₚ2 = .02). In the No-Go language, we did not find a main effect of Concreteness (F (1, 45) = .16 p = .69, MSE = .88, ηₚ2 < .01), but we did find a significant two-way interaction between Concreteness and Proportion (F (1, 45) = 4.3, p = .044, MSE = .82, ηₚ2 = .09). We followed up this interaction by considering 1:1 and 7:1 proportion blocks separately. However, we did not find significant effects of Concreteness in either the 1:1 block (F (1, 45) = 3.7, p = .059, MSE = .68, ηₚ2 = .08) or the 7:1 block (F (1, 45) = 1.09, p = .30, MSE = 1.02, ηₚ2 = .02).Footnote 4 Since Concreteness effects reversed polarity across the 1:1 block (M = −.34 μV, SEM = .12) and the 7:1 block (M = .25 μV, SEM = .15), the Concreteness by Proportion interaction in the No-Go language appears to reflect random variation in opposite directions across block types.

3.2.3. Summary of effects of theoretical interest

We found significant critical interactions between Concreteness and Target Language in both 300–500 and 500–800 ms time windows, particularly in the frontal ROI. While significant effects of Concreteness were found for the Go language in both time windows, no significant effects of Concreteness were found in the No-Go language in either time window. Furthermore, Proportion did not significantly affect the Target Language by Concreteness interaction, indicating that neither the larger Concreteness effect in the Go language nor the eliminated Concreteness effect in the No-Go language depended on the Proportion manipulation in either time window.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to establish: the locus of language control during bilingual word recognition, whether the degree of processing differs across lexical and semantic levels and whether the depth of processing depends on the proportion of each language presented. In a dual categorization task, we found that the bilingual brain can reduce lexical processing and eliminate semantic processing of words that belong to a task-irrelevant, nontarget (No-Go) language. Specifically, ERP results showed that task demands to attend to semantic category (i.e., animacy) in a single target (Go) language reduced lexical frequency effects and eliminated semantic concreteness effects for words belonging to the nontarget (No-Go) language. The proportion of each language presented across blocks had no significant effect on this modulation of processing depth. These findings support the partial selectivity hypothesis of bilingual language control and further specify potential underlying mechanisms that should be applied to models of bilingual word recognition.

4.1. Lexical processing

The finding that ERP frequency effects were reduced but not eliminated in the nontarget language indicates that nontarget words were indeed processed at the lexical level but to a lesser extent than words in the target language. This result replicates our prior work (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015) in a new population and language pair (i.e., Spanish–Basque bilinguals living in a highly bilingual environment). Our prior study suggests that this suppression effect is unique to bilingual language control, as alterations in the task to create target and nontarget categories based on semantic rather than language membership information did not produce evidence of nontarget category suppression (see Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015). The present results extend the prior study to indicate that bilingual suppression of a nontarget language at the lexical level is a robust effect across studies that have used this paradigm to investigate bilingual language control (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015; Ng & Wicha, Reference Ng and Wicha2013; Rodriguez-Fornells et al., Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002; current study).

The adaptive control hypothesis would have predicted that our results with Spanish–Basque bilinguals would more closely resemble the results of Rodriguez-Fornells et al. (Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002), who found evidence of complete suppression of a nontarget language in Spanish–Catalan bilinguals living in a highly bilingual society. However, our results more closely align with prior studies of Spanish–English heritage bilinguals in the United States who may experience more separated language contexts due to the majority language of the wider community being different than the home language (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015; Ng & Wicha, Reference Ng and Wicha2013). Since bilinguals with vastly different language backgrounds showed convergent patterns whereas those with more comparable backgrounds showed greater divergence, adaptive control does not appear to have played a strong role in producing the pattern of results in this dual task paradigm.

Small variations in the task may instead explain differences across studies. For example, Rodriguez-Fornells et al. (Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Rotte, Heinze, Nösselt and Münte2002) asked participants to categorize the first letter of each word as a vowel or consonant instead of making an animacy judgment as in our current and prior studies. Their task could have led to reduced depth of processing of words overall compared to our studies, which may have led to their finding insignificant frequency effects in the nontarget language. Additionally, their study did uncover small but significantly higher error rates for high-frequency words in the nontarget language, which could indicate some degree of partial lexical processing in the nontarget language. In any case, the majority of studies so far (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015; Ng & Wicha, Reference Ng and Wicha2013; current study) have shown partial suppression at the lexical level as indicated by reduced but still significant ERP frequency effects in the nontarget language.

4.2. Semantic processing

Over and above replicating reduced nontarget language ERP frequency effects seen in previous studies, we also discovered an elimination of ERP concreteness effects in the nontarget language despite clear concreteness effects in the target language. This novel finding suggests that participants did not process words in the nontarget language deeply enough at the semantic level to elicit concreteness effects. This result is strengthened by the fact that the same words appeared as trials in the target versus nontarget language across participants. In other words, the same words elicited concreteness effects when they appeared as a target language but not when they appeared as a nontarget language. Although the finding of reduced but significant lexical frequency effects could arguably be explained by either partial suppression of the nontarget language or enhancement of processing of the target language, the elimination of the semantic concreteness effect in the nontarget language supports the former. That is, the nontarget language must have been deactivated relative to the target language in order for participants not to have processed it at this depth.

It is possible that concreteness is processed relatively late and that other semantic factors would show some evidence of nontarget language activations at the semantic level, such as semantic relatedness between pairs of words in a priming paradigm (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Dering, Thomas and Thierry2009). Future research may reveal the degree of suppression across a range of lexico-semantic manipulations to further specify the nature of these effects. Nonetheless, with the current data, we can infer that the degree of processing decreased across the hierarchy of representational levels, with less processing at a deeper semantic level than at the lexical level. We will return to proposed mechanisms of this pattern and implications for models of bilingual word recognition below.

4.3. Language mode

The proportion of each language presented across blocks (i.e., 1:1 vs. 7:1) affected the ERP signal by eliciting an oddball P3 in the nontarget language in the 7:1 block, which was expected given that the nontarget language trials were rare in this block (Luck et al., Reference Luck, Kappenman, Fuller, Robinson, Summerfelt and Gold2009). However, contrary to our hypothesis, the proportion manipulation did not significantly affect the degree of activation of the nontarget language at either the lexical or semantic levels. Any such effect should have manifested on top of the oddball effect in the 7:1 block, for example, with concrete words eliciting more negative amplitudes than abstract words during the oddball P3 in the nontarget language. Thus, the simple presence of the oddball effect in the 7:1 block does not explain the absence of this interaction.

Behavioral results showed that participants made more erroneous responses to words in the nontarget language when they rarely appeared (7:1 block) compared to when they appeared equally as often as words in the target language (1:1 block). This pattern contradicts the prediction that the nontarget language would be suppressed more strongly in the 7:1 blocks when the stimulus list composition strongly supported activation of the target language. Instead, it may lend some evidence in favor of the prediction that reduced monitoring and control are applied to the nontarget language in the 7:1 block due to its rare occurrence in the task. Under this account, nontarget stimuli in the 7:1 block would be more likely to escape language control mechanisms, leading to a higher rate of commission errors in this condition. Although the ERP data for correct trials did not provide evidence in support of this possibility, future work may aim to collect sufficient data from commission-error trials to evaluate it more directly. A further possibility is that this behavioral pattern reflects a general task artifact, as no-go trial commission errors are typically more common than go trial omission errors outside the domain of bilingual language processing (Trommer et al., Reference Trommer, Hoeppner, Lorber and Armstrong1988).

The current data, therefore, suggest that language mode does not play as large of a role in influencing the activations of each language as proposed by some studies (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean and Nicol2001). However, it may be the case that the influence of language mode heavily depends on the naturalness of the context. Indeed, the majority of studies that have failed to find an effect of language mode implemented artificial tasks while participants read word lists (De Groot et al., Reference De Groot, Delmaar and Lupker2000; Dijsktra & van Hell, Reference Dijkstra and van Hell2003, Paulmann et al., Reference Paulmann, Elston-Güttler, Gunter and Kotz2006; cf. Dunn & Fox Tree, Reference Dunn and Fox Tree2014 who found language mode effects in a lexical decision task), while those that have found an effect of language mode generally studied more natural contexts such as sentence processing (e.g., Elston-Güttler et al., Reference Elston-Güttler, Paulmann and Kotz2005; Elston-Güttler & Gunter, Reference Elston-Güttler and Gunter2009; Hoversten & Traxler, Reference Hoversten and Traxler2020; Hoversten & Martin, Reference Hoversten and Martin2023; Olson, Reference Olson2017). The lack of language mode effects in the present study follows this pattern in the literature since we used an artificial task while participants processed words in isolation. More research manipulating this language mode factor is, therefore, needed to explicitly tease apart when language mode does or does not influence bilingual language control in comprehension. Nevertheless, we found no evidence that language mode affected bilingual language control in this dual task paradigm.

4.4. Mechanisms

In summary, the current results imply partial lexical activation and absent semantic activation of the nontarget language, regardless of the proportion of each language present in the input. This finding clearly supports a locus of language control in comprehension that lies within the lexicon, not external to it as proposed by most models of bilingual visual word recognition. In other words, we find clear evidence of direct influences from top-down sources such as task demands on lexico-semantic variables in real time (see also Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Negron and Scholl2025), as suggested by the partial selectivity hypothesis (Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2015; Hoversten & Traxler, Reference Hoversten and Traxler2020). This hypothesis suggests that while both languages can be active in parallel, they may be active to different extents based on a number of different factors (e.g., task demands, language mode, naturalness of the context, individual characteristics of the participants). In this way, a less relevant language within a particular context (e.g., the nontarget No-Go language in this task) may be only partially active compared to the more relevant language (e.g., the target Go language in this task). The current findings not only support this hypothesis but also further specify the nature of partial selectivity in terms of the degree of activation of each language across different representational levels. In this study, we found partial activation of the nontarget lexical representations and little to no activation of nontarget semantic representations.

Prominent models of bilingual visual word recognition such as BIA+ and Multilink cannot accommodate these results because they hypothesize that all language control during comprehension ultimately lies outside the lexicon in a separate task/decision system (Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra and van Heuven2002; Dijkstra et al., Reference Dijkstra, Wahl, Buytenhuijs, van Halem, Al-Jibouri, de Korte and Rekké2019). These models, therefore, do not contain any mechanism by which task demands can directly influence lexico-semantic processing in real time, as we found in the current study. On the other hand, the earlier version of these models, BIA, could potentially accommodate the current results using the feedback connections from the language nodes to the lexicon (Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra, van Heuven, Grainger and Jacobs1998; see also Declerck et al., Reference Declerck, Meade and Grainger2019 commentary).

Based on the language control mechanism implemented in the BIA model, we speculate that one potential mechanism at play here is a filtering of activations across increasing levels of the representational hierarchy. The two languages may be activated in parallel at the sublexical and even lexical levels to some extent, which are both used to identify language membership early during word recognition (Casaponsa & Duñabeitia, Reference Casaponsa, Carreiras and Duñabeitia2014, Reference Casaponsa and Duñabeitia2016; Hoversten et al., Reference Hoversten, Brothers, Swaab and Traxler2017). As activation of language nodes accumulates relatively early on, it would feed back onto the lexico-semantic processing stream to inhibit nontarget language representations according to task demands. The result, then, would be that lexical representations in the nontarget language could begin to be activated, producing small but significant frequency effects in the neural signal. However, this activation would be inhibited quickly enough to reduce lexical activations compared to the target language and critically, to prevent semantic representations from becoming activated enough to influence the neural signal for concreteness effects. In this way, activations of nontarget language representations would be filtered out across the increasing hierarchy of representational levels. To fully accommodate such a scenario, BIA would need to introduce a semantic layer of representations and specify exactly how task demands interact with language nodes during word processing.

While we conjecture that such a filtering mechanism may explain our results, it remains unclear whether it would fully explain our results given the nature of cascaded and interactive activations (McClelland & Rumelhart, Reference McClelland and Rumelhart1981). It could explain the partial nontarget language activations at the lexical level, but it is not clear that such a mechanism alone would produce no evidence of semantic activation whatsoever in the nontarget language. It is possible that the ERP concreteness effect simply taps into such a deep aspect of semantic processing that nontarget language representations at this level do not receive enough activation to influence the neural signal. Alternatively, there may be some (albeit incomplete) proactive, global suppression of the nontarget language based on task demands, such that nontarget representations are slower to accumulate evidence even from lower representational levels (e.g., sublexical (bigram) or lexical representations). Such a mechanism would be supported by studies such as Fitzpatrick & Indefrey (Reference FitzPatrick and Indefrey2014) who found evidence for a “head start” for the target language in processing efficiency. Thus, despite the cascaded and interactive nature of activations across the system, the slower accumulation of activations of nontarget language representations (alone or in combination with the feedback inhibition from the language nodes described above) could also explain the current results of partial lexical activation and absent semantic activation in the ERP data. Future research should aim to tease apart these two separate though not mutually exclusive mechanisms of language control during bilingual visual word recognition.

4.5. Potential limitations

One limitation of the study is that we implemented an artificial task rather than assessing comprehension in a natural setting. Therefore, it is possible that these mechanisms are not at play during natural comprehension. However, it is important to note that we did not instruct participants to inhibit or bypass processing of the nontarget language. They could have performed the task while fully activating representations in both languages and then deciding whether to respond post-lexically (as suggested by BIA+; Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra and van Heuven2002). If the bilingual brain processes both languages all the time no matter the context, unavoidably and automatically, then we would not have found reduced and even absent neural correlates of lexico-semantic processing in this study. The fact that we did find these effects demonstrates both a capability and an inclination of the bilingual brain to suppress the nontarget language when it is beneficial for the ultimate communicative goal. Furthermore, up to this point most studies that have demonstrated restrictions on nontarget language activation have used sentence processing paradigms. The current experiment is thus one of the few studies that has tested and shown similar effects of reduced nontarget language activation in a single word recognition paradigm. Nonetheless, future research should generalize these findings to more naturalistic contexts to develop our understanding of the mechanisms at play across different communicative settings.

5. Conclusion

We show evidence of partially selective language control in bilingual word recognition, with reduced lexical and eliminated semantic processing of the nontarget language based on task demands. These findings call for revisions to current models of bilingual word recognition to implement language control mechanisms based on task demands that operate within the lexicon and that can differentially affect each representational level. The results therefore further our understanding of suppression of the nontarget language to include both the lexical and semantic levels, with partial suppression at the lexical level and complete suppression at the semantic level.

Data availability statement

Data and materials for the project are openly available at https://osf.io/3quxj/.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the Basque Government through the BERC 2022-2025 program and by the Spanish State Research Agency through the BCBL Severo Ochoa excellence accreditation CEX2020-001010-S and through a Juan de la Cierva-Incorporación postdoctoral grant to L.H. The research was also supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (PID2020-113926GB-I00 to C.M.) and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programmer (grant agreement no 819093 to C.M.).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.