The “comuna question” refers to the fate of the comuna as the preferred form of organization in rural Ecuador. Why has the comuna (commune or registered peasant community) persisted despite political, economic, and social changes that might have otherwise eroded its appeal? Nearly a century ago, Ecuador’s 1937 Comunas Law defined procedures for registering collective property with the state, as well as procedures for the internal organization of such collectives (e.g., membership rights and requirements; the composition, purpose, and election of governing councils; the organization of meetings and work parties). Since then, communal lands have largely been divided up; trade associations, development committees, and other organizations that are all easier to create and maintain have emerged; and today, the state provides little to no oversight over the internal regulation of comunas. Therefore, we inquire into the ongoing reproduction of the comuna. What power are rural populations gaining in their comunas that outweighs the costs of rules and regulations?

A commitment to state-sanctioned rules might seem still more peculiar when contrasted with recent literature on the comunas of Ecuador that highlights autonomy or even activities against the state. During the COVID-19 crisis, for example, comunas autonomously “moved, acted, and managed” to ensure food access among their members (Lager Reference Lager2020, 32).Footnote 1 They generated barter internally—and across comunas, even as they monitored the entrance of external actors to prevent outbreaks (Lyall et al. Reference Lyall, Vallejo, Colloredo-Mansfeld and Havice2021; Tuaza Castro Reference Tuaza and Alberto2020). In 2019 and 2022, comunas represented the organizational base of nationwide, anti-neoliberal uprisings. Reactivating tactics of mobilization rooted in comuna labor practices and inter-comuna coordination, comunas forced the national government into negotiations with the Indigenous movement (Lyall and Colloredo-Mansfeld Reference Lyall and Colloredo-Mansfeld2024). In daily life, comunas independently conserve natural resources and develop tourism income (Lager Reference Lager2020; Ruiz-Ballesteros Reference Ruiz-Ballesteros2012); they defend territorial autonomy from encroachment (Álvarez Reference Álvarez2002, 8; Lager Reference Lager2019); and, in general terms, they “respond to the needs” of members (Castro et al., Reference Tuaza, Alberto and Sáenz Ozaetta2014, 31; see also Fabricant Reference Fabricant, Krupa and Nugent2015, 56). Why do state procedures of tiresome bureaucracy serve comuna members as the organizational form of choice for local, autonomous—and at times, militant—action?Footnote 2

Mercedes Prieto (Reference Prieto2015) offers one accounting. She describes comuna members as “partial state subjects” (144)—that is, as subjects of “civil control” (144) who access, conjure, and experience the state in their daily lives as comuneros and yet, simultaneously, advance “cultural autonomy” (162) through the comuna form. Within this framework, the comuna is a platform from which marginalized, subaltern subjects both manage relationships with the state and organize local, collective efforts and identities. Yet this formulation introduces a new problem: It seems to establish a mid-twentieth-century set of administrative practices as the vehicles of identity for extended families and rural collectives whose shared history and ritual life go back to a prior century, if not earlier. That is to say, while Prieto’s formulation persuades us of the tie between civil control and cultural autonomy in comuna practices, we still ask how leaders are able to reproduce cultural authority by means of (dated) arbitrary state procedures for a rising generation of comuna members with more vivid experiences of COVID-19 than of civil rights struggles of the late 1900s.

To tackle this problem, we structured intergenerational dialogues between young, university-trained rural comuna members and other members regarding the past, present, and future importance of the comuna. This methodology complements other important ethnographic approaches to the comuna based on “dense description” (e.g., Ruiz Ballesteros Reference Ruiz Ballesteros2009), as we developed a strategy of semistructured interviews that yielded contemporary data on comuna activities and sparked conversations between generations. In rural contexts in which young people often aspire to leave the comuna for educational and work opportunities elsewhere (Lyall et al. Reference Lyall, Colloredo-Mansfeld and Quick2020; Castro et al., Reference Tuaza, Alberto and Colloredo-Mansfeld2024), this strategy was rooted in the curiosity of rising generations and privileged what an older generation wanted the generations behind them to know about the significance of comuna registration and management. Specifically, four undergraduate students, members of rural comunas, conducted thirty-eight semistructured interviews with men and women comuna leaders and residents of various ages in thirteen comunas of the Andes and the coast, including their own comunas and neighboring comunas. In this way, the project was both informational and instrumental. Interviewees provided historical insights, using the interviews to make the case directly to these university-educated young leaders why the comuna is worth defending.

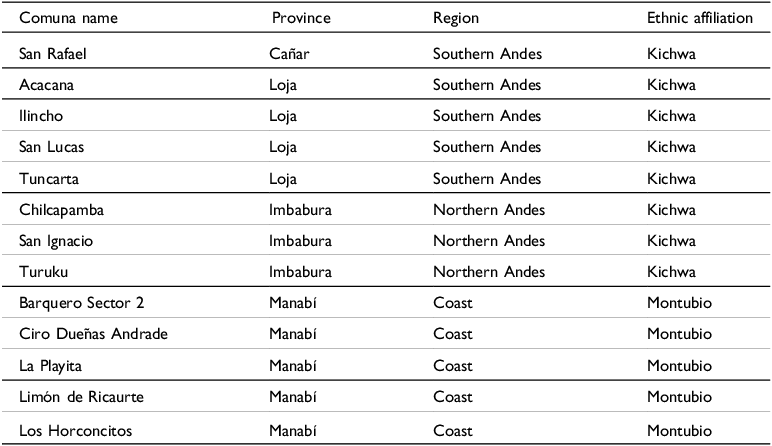

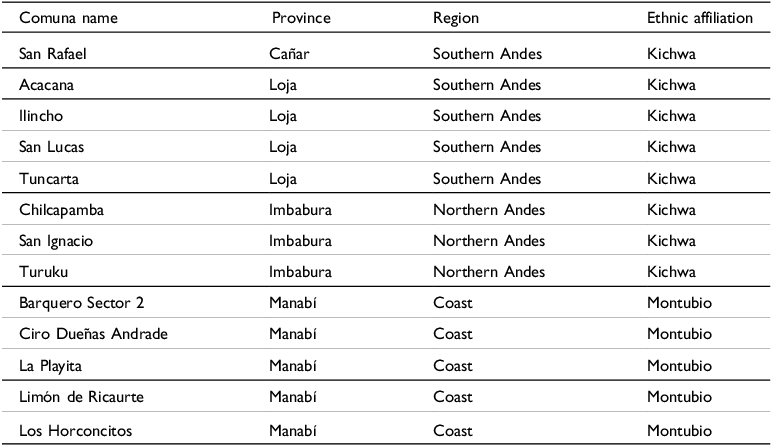

Augmenting the core work of the student research team, two of the professors involved also conducted interviews regarding comuna futures in Indigenous and mestizo comunas in the northern Amazon and northern and central Andes, where they have conducted research periodically for two and three decades, respectively. They also interviewed former government officials at the regional level regarding the evolution of state interactions with comunas. Finally, they spoke with officials at the Ministry of Agriculture and analyzed the ministry’s records of comuna registrations. In all, this research, which took place periodically over twelve months from June 2023 through May 2024, included perspectives from two dozen comunas in seven provinces (see Table 1 for locations of the comunas).

Table 1. Comunas that participated in intergenerational dialogues

We found that since the 1990s, leaders have seen infrastructure development as the essential work of comuna councils, at first as the protagonists and later as go-betweens in building and running potable water systems, recruiting companies to electrify rural communities, and improving road networks. In turn, the potential for the comuna to facilitate access to public works or infrastructure (e.g., electricity, internet, roads) is widely considered contingent on the disciplined, ongoing fulfillment of comuna procedures today. In this procedural consciousness, the practical matters of administration become expressive of and instruments for historical struggles for rights. But the implications extend further. We argue that when methodically pursued, these procedures serve as mechanisms for demonstrating moral fitness for office, legitimizing disciplined leadership, and consequently generating local authority. Indeed, research participants frequently associated a lack of local progress on access to public services with flaws in comuna procedural discipline. Expressions of frustration were rendered against an idealized notion of the historical comuna and its potential.

Chris Krupa and David Nugent (Reference Krupa and Nugent2015) edited a compilation on the Andean state in which they argue that, if the state is nothing more or less than a claim to legitimate authority, and yet state actors rarely fulfill promises, then the idea of the state depends on the production of hope—that is, hope for the eventual materialization of the state and enjoyment of full citizenship rights. For Krupa and Nugent, this would seem to be a false sort of hope—perhaps a “cruel optimism” (Berlant Reference Berlant2020), cultivated by representatives of a fetishized state and allied forces of domination. Relatedly, Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff (Reference Comaroff, Comaroff, Benda-Beckmann, Benda-Beckmann and Eckert2016) argue that the hope invested in jurisdictional recognition at the margins of the state represents a particular fetish characteristic of the neoliberal era. We draw a contrast between desperate hope invested in the state and the hope invested in the comuna among our research participants. Hope invested in the comuna is based not on an immaterial fetish but on memories of past comunas that achieved the expansion of material rights. Consequently, the enactment of formal comuna procedures—that is, of the “bureaucratic habitus” (Prieto Reference Prieto2015, 27)—that may seem geared toward currying favor with state actors have come to represent practices and idioms with which comuna leadership derives authority locally, whether or not state actors are paying any attention.

Of course, the comuna is not the only center of local authority for pursuing rights and resources in modern Ecuador. In some spaces, local water committees, church committees, and neighborhood organizations have rivaled or eclipsed the comuna in terms of importance. Second-grade organizations or networks of comunas spearhead efforts to access resources through the state, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and development agencies. And parish governments have taken on increasing importance since 2009, when they were granted budgets for local infrastructure investments. Yet it is the comuna that specifically combines the demonstration of a leader’s day-to-day competency—updating lists, scheduling assemblies, holding elections—with the collective’s historical legacy of mobilizations.

In this article, we focus our analysis on this chain of reference to history and to duty that moves back and forth among building infrastructure, state administrative procedure, the making of local authority, and the morality of collective life—all of which become activated in the contemporary comuna.

Backstory: Peasant production, state authority, and the invention of the comuna

In Ecuador, prior to 1937, many rural communities with communal lands and no formal relationship to the state apparatus referred to themselves as comunas, or communes. On July 30, 1937, the Ecuadorian Congress approved the Law of Organization and Regime of the Peasant Communes—or what is more often referred to as the Comunas Law. It emerged from debates among modernizing socialists regarding “the Indian problem” or the “incorporation [of Indigenous peoples] into the national medium” (Sáenz Reference Sáenz1933, 1) and from rising awareness of the invasion of communal lands by estate owners:

Until the promulgation of the aforementioned Law, land conflicts between landowners and Indigenous communities were constrained to the field of events, since any legal solution was prohibited to them; when … they tried to seek a legal resolution to the problem, the preferred argument … of landowners … always came down to the same thing: there is no person who can claim ownership of the community, not even the whole of its members are able to represent it, because the Indigenous villages simply lack legal status and, therefore, are unable to appear before any court. (Marchán Reference Marchán1986, 42)

Diverse groups used the Comunas Law to carve out a territorial legal identity to protect themselves from land theft or invasions. The law granted legal standing to “every populated center that is not categorized as a parish … and that has been known as a hamlet, anejo, barrio, partido, community … or any other designation” (Art. 1).Footnote 3 As this list suggests, the law aimed to provide a general structure and set of regulations for all unincorporated rural communities, not only for a specific subset with communal property relations. It was not necessary to have communal property to seek out comuna status.

The Comunas Law did, however, define quite specific forms, procedures, and even values for internal comuna organization. It recognized groups of fifty members or more who submitted governing statutes to the Ministry of Social Welfare. Annually, comuna members were to elect governing councils of five members: president, vice president, treasurer, síndico, and secretary. The governing council was tasked with improving the “moral, intellectual, and material” standing of the comuna and governing collective property, including land, natural resources, educational infrastructure, and other forms of fixed capital (Art. 17). Members had to participate in monthly meetings to address issues of “great importance” (Art. 16), whereas the council was authorized to set monthly membership fees or fines for not participating in meetings or work parties.

Formally, the Comunas Law introduced state authority into local organizing. Elections were to be conducted with the supervision of the parish government and approved by the ministry. The ministry could replace leadership that failed to sustain “moral solvency” (Art. 14). Not only did governing councils have to register property, but they also needed the approval of the ministry to acquire additional property (Art. 17). In turn, the ministry committed to supporting comunas in “material and intellectual improvement” (Art. 18) through financing collective goods, such as land, productive installations, or irrigation infrastructure, and by coordinating with other government entities to respond to other needs. According to Prieto (Reference Prieto2004), the Ministry of Social Welfare initially inspected the comunas, policing rural territories, verifying membership, resolving conflicts, and regulating relations among rural subjects and institutions over resources, although, in effect, the Comunas Law introduced the state into the lives of highland Indigenous peoples only periodically, through occasional legal intervention and state-sponsored events, such as health campaigns (Prieto Reference Prieto2015, 26–27).

Some communities resisted becoming comunas insofar as the configuration was perceived as a mechanism for state “control over rural society” (Álvarez Reference Álvarez2002, 10) or a strategy for “controlling a peasantry that was becoming independent from hacienda power” (Martínez Novo Reference Martínez Novo2007, 346). Parts of Cayambe County, for example, expressed a preference for rural unions and cooperatives insofar as the comuna was perceived as a state strategy to interfere in community life (Becker Reference Becker1999).Footnote 4

Beginning in 1960, comunas had to be registered annually with the Ministry of Agriculture. Between 1964 and 1994, agrarian reform effectively brought an end to the hacienda system as a sociocultural instrument of domination over Indigenous communities and facilitated the redistribution or purchase of land by peasant collectives, as well as the formation of comunas (Barsky Reference Barsky1988). In the 1960s and 1970s, agrarian reform witnessed an explosion of comuna registration, particularly in Chimborazo Province (Becker Reference Becker1999). In the 1970s, comunas acquired the ability to articulate into federations. In this period, the comuna became widely and, in the words of José Antonio Figueroa (Reference Figueroa2014), “romantically” (145) associated with peasant agrarian collectives of the Andes.

As part of a broader strategy of resistance, the Comunas Law was also appropriated by subaltern populations of the coastal and Amazonian regions. On the coast, many turned to this law by the mid-twentieth century to conserve historical forms of territorial autonomy. Silvia Álvarez (Reference Álvarez2002) distinguishes between coastal comunas based on “historical communal lands” and “new comunas” formed to access public services (8). By contrast, prior to the twentieth century, territorial occupation in the Amazon region had been characterized by seminomadic groups of families that occupied any given site for three or four years before moving on (Vickers Reference Vickers1989). In the context of agrarian reform, many Amazonian peoples—in addition to colonizers from the Andes and coast—used the Comunas Law to claim and carve out exclusive, bordered territories for the first time (Iriarte de Aspurz Reference Iriarte de Aspurz1980). In both regions, coastal and Amazonian populations appropriated the structure of the Andean community in accordance with the Comunas Law. Across Ecuador, this jurisdictional practice, drawing together membership rolls, monthly assemblies, demarcated territories, and formal state recognition had become the accepted unit of subaltern civil society and the way in which rural peoples engaged the state to promote their interests.

Neoliberal transitions, state withdrawal, and the turn to commercial associations

The 1978 Law of Amazonian Colonization and 1979 Law of Agricultural Promotion and Development “emptied” agrarian reform of its “redistributive content” (Naranjo Bonilla, Reference Naranjo Bonilla2016). By the 1980s, rural sociologists widely observed that a lack of financial and fixed capital (including land) and restricted market access among peasant comunas, as well as peasant unions and cooperatives, had inhibited the growth of productive peasant organizations (Murmis Reference Murmis1980; Barsky Reference Barsky1988) or had provoked their “decomposition” (Velasco Reference Velasco and Escobar1988). Neoliberal counterreforms subsequently eliminated price controls, liberalized trade, and reduced state services to peasants, as ministry investments refocused on export-oriented crops (Krupa Reference Krupa2022; Larrea and North Reference Larrea and North1997). An emerging, export-oriented agrarian elite in the Andes set out to eliminate agrarian reform altogether. Neoliberal governments recharacterized comunas as obstacles to national development—the Ministry of Agriculture even rescinded comuna status in some cases, beginning with urban comunas (Pavón Suntaxi Reference Pavón and Ángel2023, 29; see also Rayner Reference Rayner, Rayner and Mérida Conde2019). This neoliberal “offensive” (Martínez Reference Martínez2000, 10) culminated in 1994 with the Agrarian Development Law (Ley de Desarrollo Agrario, or LDA). The pro-business NGO IDEA (Instituto de Estrategias Agropecuarias) had written the core of the LDA based on a study of just four comunas (Camacho Reference Camacho1993), which concluded that comunas no longer used lands efficiently and, therefore, national development demanded that communal lands be sold off for productive investment (Whitaker Reference Whitaker1996).Footnote 5 The intent was to eliminate communal property as well as its “ideological forms” (Novillo Rameix Reference Novillo Rameix1999, 242), converting comuna members into individual, capitalist farmers (see Navas Reference Navas1998).Footnote 6

Rural sociologists and anthropologists who associated the comuna with collectivized agrarian livelihoods anticipated the demise of this institution. Leon Zamosc (Reference Zamosc1995, 60) affirmed that a spike in association formation by the mid-1990s signaled that “the comuna [had] ceased to be the preferred option” in the Andes. Many tourism and artisan associations were founded in this period (Colloredo-Mansfeld Reference Colloredo-Mansfeld2009; Colloredo-Mansfeld et al. Reference Colloredo-Mansfeld, Ordoñez, López, Quick, Quiroga and Williams2018; Lyall et al. Reference Lyall, Colloredo-Mansfeld and Quick2020). Luciano Martínez (Reference Martínez2000, 5) enumerated reasons rural communities might opt for such associations (e.g., a significantly lower membership requirements) and forgo the “complicated legal paperwork” of comuna registration, as they renounced “traditional forms of living” associated with the agrarian comuna. Víctor Bretón (Reference Bretón Solo de Zaldívar2001, 74) went a step further, arguing that, in effect, “communal lands did not exist” (74), and in the absence of communal agrarian resources, “we cannot talk about the existence of a community” (75). During the remainder of the 1990s, comunas became widely represented by NGOs and the state as nonproductive objects of social welfare intervention; subsequently, the NGO sector of rural development burgeoned (Bretón Reference Bretón Solo de Zaldívar2001, Reference Bretón Solo del Zaldívar2008). Although many comunas did not claim Indigenous identity or reflect the “essentialized ancestral characteristics” of “imagined ethnicity” (Álvarez Reference Álvarez Litben2016, 329), national development programs such as PRODEPINE (Project for the Development of the Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian Peoples of Ecuador) in the late 1990s incentivized rural collectivities to identify as Indigenous to access state and NGO resources (Bretón Reference Bretón Solo de Zaldívar2001). The countryside at the turn of the century became characterized more by individual, nonagrarian economic strategies, pluriactivity, and urban migration than by communal farming (Lyall and Colloredo-Mansfeld Reference Lyall and Colloredo-Mansfeld2024).

Today, rural Ecuador seems to be a world apart from the era of agrarian reform in an economic sense, as rising generations widely reject family farming as a viable livelihood (Lyall et al. Reference Lyall, Colloredo-Mansfeld and Quick2020) and, instead, pursue education and/or employment in cities (Lamino et al. Reference Lamino, Millares, Landaverde and Boren-Alpízar2024). Rural activists pursue development objectives with organizational alternatives to the comuna. For example, we interviewed members of two “pro-improvements committees,” which are organizations registered with the Ministry of Urbanization and Housing that require only fifteen members and fewer rules for participation and internal organization. Gary Manuel Vargas Alarcón, president-elect of one such committee in Chone, Manabí, explained that their committee was conceived of in similar terms as a comuna: “It is an organizational mode for the common good … Individually, nothing can be achieved.” With such legal recognition, it was easier for them to gain an audience with government officials. Consequently, he reported, “We have a community house, roofs, water, energy, and telecommunications … We are almost complete in infrastructure.” Development committees deliver. Why, then, has the comuna proved so durable when other, less demanding forms of organization are available?

The comuna as infrastructure and comunero as usuario

Faced with decades of research that spoke of forces eroding the comuna as an agrarian institution, our research team sought to document how current leaders established an agenda for their work. As market and political forces sought to terminate the comuna as an agrarian institution in the 1990s, comuna leaderships redeployed their authority, negotiating with the state to pursue nonagrarian demands, or what might seem to be a sort of “municipalization” of the comuna. Among such diverse ends, infrastructure development emerged as the key objective in relation to which comuna members tend to evaluate the limitations and potentials of the comuna. Marjorie Carlota Carpio Morán, of the comuna Barquero Dos, argued succinctly that today “the comuna is infrastructure.”Footnote 7 In this section, we describe the different ways that infrastructure aspirations have demanded the time and skills of local councils. Amid the diversity of projects that they have been called on for, councils have in effect built a literal common ground for member households whose own work has become increasingly diversified in commodity production, nonagrarian rural work, migration, livestock raising, jobs in the police and armed forces, and community tourism.

We spoke with a series of comuna members who traced a transition in the 1990s in the focus of comunas from that of managing agrarian resources toward accessing infrastructures for public services. In Cañar, for example, Natividad Pichazaca said that her comuna initially formed as a cooperative during agrarian reform but, in turn, refounded as a comuna as it became clear that comunas might better organize collective pressure on the state to access basic services. Laura Santellan, of Cotacachi, grew up in the comuna of Agato, where families worked in agriculture and handicrafts. She migrated to the city in the 1980s in the hope of studying at university. Because of a lack of funds, she became a nursing aid at a hospital instead, where she witnessed racism and individualism that drove her back to Agato. In the early 1990s, she returned to her comuna and became its first female leader, spearheading infrastructure projects such as roads and potable water pumps.

A former comuna president in Cotacachi, María Rosa Quinchiguango, recalled that in her youth, there was no potable water, gas, or electricity. Before becoming a legal comuna, they built a community center and stadium with the help of the provincial government, but, she argued, they had to legalize the comuna in 2005 “to obtain power.” The Ministry of Agriculture helped them to legalize the comuna to get public services, and then Quinchiguango began to travel to Quito to pressure institutions on behalf of the comuna for “services and public works.” The municipal government required that her comuna provide labor for building public lighting or potable water infrastructure; in turn, the municipality helped them incorporate abandoned lands into the comuna—not for agricultural activities but for public works, such as a stadium.

On the coast, Ángel Rubén Zambrano (comuna president) and Teresa Hidalgo (comuna member), of the comuna Limón, recalled that, in the era of their grandparents in the 1980s and 1990s, families organized to sell corn or rice in groups, but only in the previous two decades had they formalized the comuna to “request help from the municipality, the prefecture, and the parish governments” for basic services. Alberto Anrango, a former mayor of Cotacachi, recalled that the objectives of comuna governing councils shifted toward public works in the early 1990s. Anrango worked with the comunas in his county to build roads, schools, and potable water infrastructure. A former mayor of Cayambe explained to us that, with funds from the World Bank, municipal governments began to actively organize comunas in the late 1980s to weave client relationships—and use free comuna labor through work parties—to expand public works. The 2008 Constitution and subsequent legal apparatus elevated the comuna to a scale of government, as an agent or proxy within the state apparatus, to support the expansion of infrastructure. In Chone County, comuna president Patricio Zambrano explained that legal recognition as a comuna has become widely perceived as “an identity for the community” or as the sine qua non for “any politician or any organism” to carry out infrastructural projects in the community. Zambrano observed that the municipality of Chone responds to lots of communities that are not comunas, and so his community decided to form a comuna strategically “to obtain support and a prompt solution to the [potable water] problem—the comuna is very important because it works together with the parish council, the municipality, and the provincial council.”

The primacy of infrastructure is evident in the vocabulary surrounding membership in comunas. When speaking of members, elected leaders in Imbabura shifted among the terms comuneros (community members), socios (associates), and usuarios (users). If all three were synonymous in referring to registered members, then we would highlight that the last term—user—evokes access to water or electric systems. In today’s comuna, the minimum a member could expect of the council is that it advocate to parish water authorities or the electric utility for the extension and restoration of such services. Behind this “customer service” role lies the pressing economic needs of women and men operating within diverse informal economies that span city and countryside. The modernization of services is essential for those who tap their rural landholdings and homes as capital, refuge, and instruments of production to advance the disparate economic aspirations they now hold.

Authority within and against the state: Registration and internal struggles for legitimacy

In meeting their constituents’ expectations, comuna governing councils in this research did not tend to see themselves as state proxies but rather as organizers of collective action within the comuna to pressure resistant state actors. Paradoxically, one of the most effective tools to prepare residents to mobilize against the state has been the methodical execution of the requisites for registering with the state. Indeed, many take for granted that protesting against the state is the essential step to ensuring close collaboration with its ministries and programs. Hayda Zambrano Sandoval Solórzano, president of the comuna Horconcitos in Chone County, described to us continuous campaigns around infrastructure projects: “We go on strike because when there is a strike, people pay attention—that is, the authorities pay attention; if they do not make a strike, there is no need in that community, but when I see, ‘Ah, really, if there is a need, we are going to pay attention,’ there they go … If you do not shout, nobody pays attention to you. That is why there is a saying: ‘He who cries, suckles; he who asks, eats.’ If no one cries, no one gives him his bottle to drink. Stoppages are necessary.” The comuna president Ángel Rubén Zambrano emphasized that processes of political pressure articulate continuously through the comuna because of the added problem of infrastructural maintenance and repair: “Thanks to the Parish Council, we now have drinking water or piped water, although it is not 100 percent potable; we are currently managing because our pump burned out, so … the comuna met and agreed to send an official letter to the mayor.” Although water, electricity, and road projects may operate with engineering and financial profiles that exceed the comunas’ capacity for direct management, for users, the functioning of these systems falls to the advocacy skills of comuna governing councils, whose members mediate between the state, operators, and comuna members. Successes in wresting projects from state actors, in turn, reinforce comuna organizing and social networks. In Cañar, Rosa Guamán says, “Thanks to the comuna we have water [for consumption]; irrigation water … ; access roads; light; assemblies that serve for everyone’s lives and for that we belong to the comuna, and we will continue organizing festivals.” Local organizing serves evolving ends for subaltern populations. “When certain rights are achieved,” Bagner Sarango, of Loja, explained, “new needs emerge.” But, again, we return once more to the question of why organizations do not take the form of artisan associations, development committees, or other formal organizations that are easier to create and maintain?

Across research contexts, we found that the institution of the comuna is associated closely with emblematic social struggles for rights in rural areas in the twentieth century—that is, for land and for schools. Some interviewees did recall histories of local, collective action before comuna formation (e.g., building homes, preventing land theft, sharing food, struggling to close cantinas), but struggles for land and education in the twentieth century elevated the comuna as an institution of national importance and enduring potential. In the southern Andean province of Cañar, an elderly comunera member named Antonio Acero said, “They wanted their own lands and to not depend on the estate owners; with the agrarian reform, we started to get lands and then new rights—we started to study.” Antonio linked past struggles to the potential for further expanding social rights in the present or “new opportunities, basic services, health care.” Tránsito Morocho, of Cañar, described the comuna, in short, as a “legacy” or an “inheritance that changes from one generation to the next,” although the “goals of well-being of the community change and improve.”

Comuna members repeatedly compared the performance of comuna procedures by past and current governing councils—often expressing frustration with any perceived gap or lack of discipline among current councils and members. In Cotacachi, María Rosa Quinchiguango, for example, emphasized the lack of fulfillment of obligations in her comuna, which had recently prohibited the sale of lands to outsiders, for being even less likely to adopt comuna rules and regulations. Here, we would illustrate such concerns for comuna regulations by describing dynamics we observed in the context of an anti-neoliberal protest in 2022. A research participant sent us a video of comuna members in Chimborazo Province who were maintaining a blockade along a mountainous highway pass.

The video featured a dozen families sitting in the road. The wind muffled their chatter. A few kids ran circles around the adults. The filmmaker narrated the scene, praising her comuna and commenting on the beauty of the mountains and valleys beyond the blockade. Her pride in place was evident. When a separate group of families appeared on the roadside, prepared to relieve them at their post, a woman called out: “Where is the list? Who has the list?” She wanted to ensure that her participation was registered. But the list was nowhere to be found. Grumbles and complaints became audible against the blustering wind: “There is no organization! Where is the president?” These comuna members were demanding that the procedures of the comuna be respected. The comuna governing council, which conducts elections, work parties, assemblies, and registration, knows that such forms of discipline underwrite their authority and are conducive to effective collection action. In other words, comuna members evaluate the fluency of the governing council in these practices to grant them moral authority that can be put to work.

It is in this context that we investigated the official, bureaucratic consequences of the council’s organizational efforts. At the heart of the comuna leaders’ work is the annual requirement to register with the Ministry of Agriculture. In accessing the databases of the ministry and speaking with ministry officials, we examined two dimensions of the patterns of ministry recognition in a subset of parishes in which Lyall and Colloredo-Mansfeld had done ethnographic work between 2005 and 2018, which includes eighty comunas in the provinces of Imbabura (twenty-two), Pichincha (twenty-nine), Cotopaxi (twelve), and Chimborazo (seventeen). Bearing in mind the current cultural meanings of the history of struggle for rights, we looked at the original dates of comuna formation to understand how deep the tradition of state recognition was. In addition, we solicited the most recent list of registered comunas to document the alignment between ministry records and local efforts to stay registered.

Imbabura was clearly an early site of jurisdictional registration, with twelve communities gaining jurisdiction in the 1940s. In Zumbahua parish, Cotopaxi Province, seven of nine comunas began registration in the 1960s. Cangahua parish in the province of Pichincha witnessed a surge of new registrations (eight of twenty-nine) in the 2010s. Such variations would suggest the presence of regional catalysts for organizing, independent of state policy at the national level. One could speculate on these causes. For example, in the 1940s, the construction of the Pan-American Highway and the early commercialization of textile production may have sparked organizational activity in Imbabura Province. In the provinces of Cotopaxi and Chimborazo in the 1960s, land reform provided incentives to organize to acquire land in regions dense with haciendas. Meanwhile, in Cangahua, the expansion of the export-oriented, cut-flower plantations into hillside communities in the 2010s was a new inducement to competition for investments in water systems and improved roads. New registrations in the 2010s might also have been related to new comuna rights defined in the 2008 Constitution.Footnote 8 Potential correlations are there, although research is needed to establish precise links between economic and political changes and jurisdictional strategies.

We then examined the current registration of a subset of twelve comunas. We asked council members of these comunas about their registration histories with the ministry. All twelve councils reported dutifully fulfilling registration requirements annually, including in 2023, when we conducted interviews. Each respondent took for granted the necessity of registration. In one exchange, the interviewer asked, “Why are you registering the community?” The president replied simply, “So that each member can be registered.” Not to do so would leave them at a loss. As another president put it: “If we do not have registration, we do not have anything. Without registration, we are like any other person.” In his view, registration separates a person from the mass of ordinary Ecuadorians and elevates them as a member of a collective, as a person who must be heard. However, the ministry itself could not confirm the registrations of these comunas. Although the ministry did have a record of each of the comunas’ original founding date and membership numbers, it listed only five of twelve communities as “registered” or “in the process of being registered.” In all, the institution provided us with a list of 1,555 comunas in Ecuador in 2023. The central office was able to call up partial registries from some provincial offices; other provincial offices were unresponsive. That is, some provinces were missing from the list altogether.

Today, we cannot estimate the number and geographical distribution of comunas on a national scale because the official registry of comunas is limited. What does this lack of comuna registration mean in relation to our research question regarding the endurance of the comuna form? It suggests to us that the act of registration is not primarily meant to establish a working relationship with the Ministry of Agriculture. Reinforcing this conclusion, technicians at the ministry told us that today the ministry does not work with comunas on productive matters but rather with individuals or associations registered as producers under the definition of “peasant family agriculture.”Footnote 9 The procedures of comuna registration and administration defined in the 1937 law seem anachronistic or arbitrary today insofar as state actors are not paying attention to the internal conduct of individual comunas. If comuna members carefully continue to speak the language of the state, the state does not seem to be listening. It is the membership itself that is paying attention, and in doing so, it is the membership that grants legitimacy to local authorities and capacities for collective action.

Comunas, individualism, and the collective self

The perception of poor organizing and declining respect for comuna rules is often accounted for in terms of rising individualism. In Cañar, Juan de Dios Pichazaca lamented that “our grandparents were true comuneros … these days there is no participation” In Cañar, Magdalena Acero complained, “There is not the same unity as before.” On the coast, Patricio Zambrano stated similarly, “In past decades, the families were more collaborative: If someone organized an activity like a raffle, someone would say, ‘I will donate a chicken’ and nobody had to force them; another person would say, ‘I will donate a pig for the raffle’ … Now there is more egoism.” In the southern province of Loja, Bagner Sarango added that “growing individualism” among rising generations results from the influence of political parties, whereby comuna members seek to build their electoral profiles as leaders to run for the parish board or the municipal government, rather than submit to the consensus-building logic of an assembly space.

The conversations we collected largely reinforce the notion that the comuna is a space of “discussion and consensus” (González Reference González Andricaín2009, 118). However, this mutuality is accompanied by the reality that comunas are also hierarchical spaces in which power is disputed and distributed locally. Such criticisms and critiques may operate as forms of social discipline that shape the future effectiveness of the comuna; critiques of others may also serve to represent oneself as truly committed and, therefore, competent for office; and of course, criticisms may reflect the actual erosion of social cohesion—for example, due to out-migration. In Cañar, José Pichazaca says, “Migration is one of the roots of many problems in the community; this has generated the loss of the ayllu; the majority is no longer here and this has contributed to the separation and lack of organization … for example, the work parties that are not the same or the festivals.”Footnote 10 Regardless of the way people see the threats the comuna faces, the effort to close a perceived gap between past and current comuna-ness sustains the possibility of and hope for expanding rights into the future. Here again it is dedication to administrative minutiae (e.g., updating membership lists, scheduling and carrying out assemblies) that endows hope with substance.

In a broad sense, the comuna serves so many social, cultural, and economic purposes today that it is frequently referred to synonymously with “community” itself. In their dialogue with the student researchers, experienced comuna members emphasized the integrated well-being a person gains as a member of a comuna. It was widely conceived of as a refuge from challenges on the “outside” and associated with a sense of protection from ethnic discrimination or from the anonymity of urban society. In Cañar, Juan de Dios Pichazaca described the comuna as a place “to live together, among friends.” It is a place where, according to Lucinda Duy, “everyone feels comfortable.” This sense of place has taken on renewed significance in recent years in relation to growing insecurity in the cities, where gang activities are concentrated. In the northern Andean county of Cayambe, Elena Tandayamo expressed this sentiment by analogy: “A person who does not participate in the comuna is like an untethered sheep; they are not safe.” In Cotacachi, Ligia Morales stated that she felt protected as a comuna member because she could access loans or donations for medical care. Another Cotacachi resident, Takiri Moran, explained, “You never lack food in the community; in the city you do,” adding that the COVID-19 pandemic was easier to survive as a comuna member. In the coastal comunas, raffles or other fundraising events are commonly organized to support members with health-care needs. In 1983, the rural sociologist Manuel Chiriboga (Reference Chiriboga1984, 24) suggested that economic understandings of rural comunas among his peers were reductive insofar as comunas fulfilled a diverse array of productive, political, and sociocultural purposes, including and beyond “political representation and defense” (cited in Martínez Reference Martínez1998, 3). The pursuit of such diverse ends through the comuna persists, even as those ends transform over time.

Conclusions: Legal formalities and hope in the contemporary comuna

Marie-Therese Lager (Reference Lager2019, 6) posed the question, “How can the comunas survive and persist under conditions of global capitalism?” The agrarian political economy in which the comuna proliferated has changed dramatically over the past fifty years or so. A series of neoliberal governments have sought to accelerate economic transition at times precisely by dismantling the assets and authority of peasant organizations. Yet the comuna was never only an economic institution; rather, it stands in for a host of social, economic, and political relationships. It represents economic networks and support; a place of sociocultural identity, acceptance, and companionship; and a political legacy and platform.

According to the 1937 Comunas Law, the local political representation or authority achieved through the comuna is derivative of state sovereignty. Whereas the national constitutions of 1946, 1967, 1979, and 1998 made no mention of comunas as an administrative unit, the 2008 Constitution called on local governments to “promote the organization of citizens of comunas” (Art. 267, 6) and to conceive of comunas as partners in expanding public services (Colloredo-Mansfeld et al. Reference Colloredo-Mansfeld, Ordoñez, López, Quick, Quiroga and Williams2018).Footnote 11 In the early years of the post-neoliberal turn (2007–2017), state actors treated the comuna as a proxy for the state, particularly to accelerate the provision of infrastructure. In 2023, an ex-mayor of Cayambe commented to us that, in effect, the figure of the comuna serves for community leadership to “derive authority from the central state.” One might conclude that the comuna is increasingly submerged in the state apparatus. Moreover, one might interpret such a trend as facilitating the replacement of “radical protest politics” with a “politics of the possible” (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee1997), cited in Gudavarthy Reference Gudavarthy2014, 5). Indeed, community organizing has been motivated to gain legal recognition in order to resolve disputes over land and labor through the state since the beginning of the Republic (Coronel Reference Coronel and Kingman2009).

However, community organizing has also been motivated historically to lobby for social and institutional change through direct action against the state (Becker Reference Becker2015). In the 1940s, the Ecuadorian Federation of Indians (Federación Ecuatoriana de Indios, or FEI) recognized comunas as part of its base of national organizing, alongside cooperatives, unions, and cultural institutions (Becker Reference Becker2007). Since the 1980s, the national Indigenous movement has affirmed the comuna as its “base” of political organizing and opposition (Breton Reference Bretón2025; Simbaña Reference Simbaña2022). If it is a state form, then the comuna is also a vessel of cultural autonomy, returning to Prieto’s (Reference Prieto2015) characterization. In the narratives of our research participants, the relationship between the comuna and the state continues to be anything but harmonious. The comuna is largely valued for its ability to pressure the state from a position of exteriority. In these narratives, the comuna has accumulated legitimacy in relation to historical, emblematic victories.Footnote 12 In turn, comuna leadership derives its authority not from state recognition but from the historical memory of prior comuna exercises of collective action that wrested concessions of social rights from the state. Notions of effective local organizing are constituted in terms of the proper procedures and rule following defined in the Comunas Law that were used in other moments.

In fact, we highlight the surprising way that autonomy, independence, and place-based identities have come to be measured and operationalized by how well a collective of rural people can jump through the bureaucratic hoops of comuna registration and management in accordance with state rules and regulations. As Krupa and Nugent (Reference Krupa and Nugent2015) argue, the maintenance of authority in the face of continuous setbacks and failures requires the active (re)production of hope.Footnote 13 The comuna derives hope from procedures and rules that become viewed as memory and as forward-leaning habits: “The persistence of habit ensures historical memory, but it is also an ethical claim on the future,” writes the theorist Jon Beasley-Murray (Reference Beasley-Murray2010, 178). Such formalities might seem to reflect what the anthropologists Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff (Reference Comaroff, Comaroff, Benda-Beckmann, Benda-Beckmann and Eckert2016) have described as a jurisdictional fetish; yet the rituals to formalize and manage the comuna are no mere ideological fixation on stateness. They are instrumental to coordinating autonomous, collective action, as leaders derive legitimacy from performing procedures to put authority to work or, at least, to sustain hope.

In summary, through intergenerational discussions among comuna members in more than two dozen comunas, we found that participants tended to associate the expansion of social rights, particularly with access to land and education in the twentieth century, with the disciplined fulfillment of comuna procedures. Conversely, they widely associated a lack of contemporary progress on other rights (e.g., public services) with flaws in procedural discipline. Expressions of frustration sustain hope for the fulfillment of comuna potential. This is not an unfounded or ideological hope that state theorists describe at the root of state legitimization or a blind faith in jurisdictional recognition; rather, the hope invested in the comuna form emerges from historical experiences. The enactment of procedures for comuna registration and management may seem geared toward state recognition, but for comuna members, these are historically legitimized practices and idioms from which comuna leadership derives authority locally, whether or not the state is paying attention.

Comunas is a research collective based in the Universidad San Francisco de Quito in which students from rural communities and professors develop questions on the past, present, and future of communal organization and life and collaborate in carrying out qualitative research. The students (Bryan Salas, Luis Malqui Maigua Moran, Flor Maritza Guamán González, Mariuxi Lizbeth Gualán Guaillas, and Matías Adrián Guaita Noroña) are from diverse regions of Ecuador, and their professors (Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld, Angus Lyall, and Gabriela Valdivia) have been conducting research on rural politics and livelihoods in the Ecuadorian Andes, Amazon, and coast for multiple decades. This article represents our first publication.