In 2022, a Watergate-style scandal rocked Greek politics. The intelligence service appeared to have wiretapped members of the opposition, government officials, journalists and others. As this article shows, the 2022 scandal builds on long-term historical patterns of politicisation of the Greek intelligence service. Intelligence services have played pivotal and distinct roles in European political history since the Second World War, ranging from their position as a stronghold of authoritarian regimes to their role in protecting democracy from anti-democratic forces. Their function as such protectors gives them a special status that is more enduring and independent from the day-to-day squabbles among political parties and other actors. At the same time, as bureaucratic agencies, intelligence services operate in a political environment from which they derive their legitimacy and budget, but within which they are also objects that any politician aspiring to power would like to control. In such cases, intelligence operations may serve the short-term, electoral interests of the political parties who provide patronage.

This article shows the changing but persistent nature of politicisation of the Greek intelligence service between 1974, when the country transitioned to democracy, and 2008. The year 2008 represents a turning point for several reasons: it marked the introduction of a new legal framework intended to modernise the service and regulate its operations; it coincided with the onset of Greece’s economic crisis, which reshaped the priorities and constraints on state institutions, including intelligence; and it marked the beginning of the decline of the two-party system that had dominated Greek politics since the restoration of democracy. The economic crisis was a profound shock to the Greek state, and for the next few years, economic and financial issues dominated the priorities of the government and public discourse. As such, the Greek National Intelligence Service (EYP) largely faded from public attention until 2022, when the emergence of the wiretapping scandal reignited interest in its activities and brought the issue of intelligence politicisation back into the national spotlight. Although the 2022 wiretapping scandal occurred outside the specific timeframe of this study, it serves as a recent reminder of the enduring challenges related to the politicisation of intelligence services and underscores the continued relevance of the historical analysis presented in this article.

We argue that from the end of the junta regime, and especially between 1981 and 1995, the parties in power were keen to keep the Greek intelligence service under control. Several successive governments fought fire with fire: they countered the junta heritage of the intelligence service by keeping the service closely under their control and, consequently, aligning it with governing party interests. Accordingly, we explain that the politicisation of Greek intelligence is, paradoxically, related to attempts at distancing intelligence services from their authoritarian legacy.

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in scholarly works examining Greece’s post-dictatorship era, particularly focusing on the ‘Metapolitefsi’ (restoration of democracy). Notable contributions to this scholarship include Avgeridis et al.’s comprehensive volume mapping the broader political, social and cultural history of Greece after 1974, Kallivretakis’ analysis of the political transitions from dictatorship to democracy and Hatzivassiliou’s study of transitional justice during the immediate post-junta years.Footnote 1 Additionally, Karamanolakis, Nikolakopoulos and Sakellaropoulos explore key moments in the transition from 1974 to 1975 and offer valuable insights into the political, social and institutional transformations of this period.Footnote 2 This article examines the role of the intelligence service in Greece’s democratic consolidation, complementing the ongoing broader discussions. More specifically, historical research on the Greek intelligence service, in Greek and especially English, is surprisingly scarce in comparison to the political attention it receives. Until recently, former head of service Pavlos Apostolidis was the only person with access to the service’s archives. He wrote the only non-operational, institutional history of the intelligence service, an essential starting point for any research on the Greek service.Footnote 3 The early institutional history of the Greek intelligence service indirectly occurs in research on the junta regime and the Greek armed forces, in particular the secret army officers’ organisations IDEA and ASPIDA.Footnote 4 The service also appears in studies of several Greek service employees who played a prominent role in Greek political history, such as Alexandros Natsinas (first head of the Central Intelligence Service (KYP)), Georgios Papadopoulos and Nicholas Makarezos (protagonists of the junta regime).Footnote 5 Most research on the Greek service, however, tends to focus on the present and future, in the context of which the past plays a secondary role or none at all.Footnote 6

More directly related to this article, recent publications by Eleni Braat and Sofia Tzamarelou focus on the democratisation of the service after the end of the junta regime. Both emphasise the decisive role of officials who staffed the service during the junta period and stayed on after the restoration of democracy. The continuous presence of these officials significantly contributed to hampering attempts to democratise the Greek intelligence service. Braat explains why the demilitarisation of the service – crucial for its democratic embedment – was slow to materialise and largely independent from governmental politics regarding democratisation. Instead, the socio-cultural demilitarisation of the service had its own dynamics.Footnote 7 Tzamarelou’s work, while briefly discussing the demilitarisation of the Greek service, focuses on additional factors that have influenced its democratisation, such as oversight, operational interests and the role of civil society. Her research consists of a systematic comparison of these ‘security sector reform indicators’ for the Portuguese, Greek and Spanish intelligence services after the end of the dictatorships in the mid-1970s. Tzamarelou’s comparative research shows that authoritarian legacies, although a barrier to reform, can lead to different outcomes in terms of intelligence democratisation.Footnote 8

Below we explain the relationship between the politicisation of intelligence services and an authoritarian legacy, by pointing to wider mechanisms of politicisation of intelligence services, particularly in the third wave of democratisation in Southern and Eastern Europe. We then discuss the opportunities and drawbacks of the primary sources of our research, and we analyse three periods of governmental dealings with the Greek intelligence service. These three periods coincide with important party-political shifts: bipartisan support for distancing the intelligence service from its old former self under the junta regime (1974–81), the intelligence service under party patronage and as a tool for governing parties to monitor the opposition (1981–95) and renewed attempts to increase the independence and professional character of the service (1995–2008).

How Does an Authoritarian Legacy Relate to the Politicisation of Intelligence Services?

What is politicisation of intelligence, how does it work and why can it coexist with democratisation, which would appear to be the opposite phenomenon? In a politicised public administration, political criteria such as ‘party loyalty’, networks and other resources are more important than merit-based criteria such as expertise (degrees) and experience (seniority) in the recruitment, appointment, promotion and disciplining of civil servants. The politicisation of bureaucracy by (governing) political parties is a means to control policy and its implementation, reaching beyond the scope of merely providing jobs to a group of like-minded individuals as a spoils for office.Footnote 9 Some degree of politicisation is not always a ‘bad’ thing, as it may do justice to electoral outcomes. Consequently, a moderately politicised intelligence service, as other politicised state bureaucracies, may generate more joined-up policy-making, rallied around a coherent, ideological idea whose implementation has been pledged in electoral campaigns and supported by the majority of voters. Politically driven agency initiatives may therefore be more goal-oriented, and their products may correspond better to governmental and public needs, compared to fully technocratic, bureaucratically centred policy initiatives. At the same time, politicised services often experience ideologically rooted tunnel vision and policy bias, producing distorted intelligence analyses that are tailored to the expectations of the governing party rather than being supportive in the long-term maintenance of the democratic order. Unsurprisingly, in cases where this occurs systematically, politicised intelligence services produce lingering hostility and distrust among citizens, and a situation in which intelligence cannot be valuable in the public policy-making more broadly.

To explain the politicisation of intelligence services, we distinguish between top-down and bottom-up mechanisms of politicisation.Footnote 10 Literature on the politicisation of public administration largely focusses on top-down politicisation, where executive control is the main channel of party-political influence over the bureaucracy. Along such top-down lines, Rovner understands the politicisation of intelligence services as the ‘manipulation of intelligence to reflect policy preferences’. This occurs either directly when leaders intervene to modify analytical outcomes, or indirectly, involving subtle signals to the intelligence service about the anticipated outcome of estimates.Footnote 11 Physical proximity between leaders and the intelligence service (e.g. working in the same building), organisational dependence and bureaucratic collaboration may facilitate the occurrence of direct and indirect politicisation of agency leaders.Footnote 12 However, not all relevant political resources or ‘patrons’ may reside at the top of political parties in office. Organisations rooted in society may drive politicisation from the bottom-up or, at least, without the immediate employment of bureaucratic hierarchy or ministerial authority. This happens when civil servants in the agency mobilise along party-political lines, triggered by political organisations, most notably labour unions. As Sotiropoulos points out regarding Greek public administration, labour unions with elected leaders belonging to specific political parties can play a decisive role in such bottom-up politicisation processes.Footnote 13 We similarly find that the labour union of the Greek intelligence service, whose leaders were alternately affiliated with the socialist party (Panhellenic Socialist Movement, PASOK) or the conservative party New Democracy (Nea Dimokratia) , constituted a decisive mechanism in fostering and sustaining a politicised service.

Paradoxically, we observe that the politicisation of intelligence often occurs in a context of democratisation. This is paradoxical because politicisation often persists in ways that undermine the goals of democratisation, even if democratisation entails consequences such as the depoliticisation of intelligence services to prevent their reuse as tools of political oppression. It is important to acknowledge that the expectation of depoliticisation can be particularly challenging in the context of democratisation, where strong political antagonisms are common. In post-authoritarian Southern and Eastern Europe numerous examples exist of top-down and bottom-up politicisation of intelligence. For instance, we observe several cases where the governing party has used intelligence services to monitor the opposition. As this article shows, this happened in Greece in the 1980s and 1990s, and until recently as the scandal in 2022 suggests. However, Greece is no exception. Similar instances occurred in Hungary in the 1990s and 2000s, and in Albania, Croatia, Serbia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Spain in the 1990s.Footnote 14 Governmental shifts led to frequent leadership and personnel changes in Greece in the 1980s and in Poland in the 1990s.Footnote 15 Until the 1990s, Spanish intelligence prioritised new employees with ties to the military or who were politically aligned with the rest of the service rather than relying primarily on merit-based criteria to select their employees.Footnote 16 These examples suggest that the democratisation of the political system and the politicisation of intelligence go hand in hand.

Why do these seemingly opposing phenomena coexist? While there is ample research on democratisation in general, it prioritises universally applicable ‘pathways’ to democratisation, outlining specific conditions and processes. Little is known, however, about historical causes that promote or block democracy in an unruly, non-linear way, depending on the period and region.Footnote 17 We know even less about the democratisation of intelligence services, as ‘the last frontier for attempts to democratise previously authoritarian government structures and processes’.Footnote 18 In line with the general literature on democratisation, several scholars point to rational-legal criteria to democratise this ‘last frontier’, such as the structure of accountability mechanisms and the powers of oversight bodies.Footnote 19 They consider intelligence services per se to be at odds with democratic governance, arguing that robust accountability mechanisms can compensate for this inherent incompatibility between democratic transparency and operational secrecy. A small body of literature moves beyond this rational-legal approach, explaining the democratisation of intelligence from an historical institutional perspective.Footnote 20 These scholars suggest that an authoritarian past creates path dependency that either enables or constrains democratisation. Such enabling or constraining mechanisms are historically constructed, non-intentional and casual. They relate, for instance, to the composition of staff of an intelligence service, the fragmented or centralised structure of the national intelligence capacity or operational interests.

Post-authoritarian governmental measures may contribute, to a greater or lesser degree, to the disruption of this path dependency. An example of radical disruption occurred in the Portuguese intelligence service after the 1974 Carnation Revolution. The lustration of the intelligence service paralysed the service in the first years of democratic rule, but it defined and enabled the further course of its democratisation.Footnote 21 Few intelligence services experienced such radical lustration, and Tzamarelou shows how the lack of radical lustration in the Spanish and Greek intelligence services has been a restraining factor in democratising these services in later years. Another common governmental measure to disrupt authoritarian path dependency is to fragment a formerly centralised service. The service can be divided, for instance, along foreign and domestic lines, military and civil, or intelligence and counterintelligence. This occurred, for instance, in Portugal after 1974, in Brazil after the military dictatorship in 1985 and in Romania, Hungary and Russia after the end of the Cold War.Footnote 22 By contrast, Spain and Greece maintained centralised services. Moreover, the continuingly strong military components in these services hindered attempts to prioritize hiring more qualified employees rather than politically loyal ones.

Even though such measures to politically disempower or bureaucratically neutralise intelligence services may be effective, we point to two mechanisms that make it plausible to expect politicisation rather than depoliticisation as part of democratisation. First, we depart from the idea that typical differences exist, over time and across national contexts, regarding the separation between public administration and ‘politics’, regardless of whether the regime is democratic or not. In Greece, the general administrative tradition is characterised by high levels of politicisation of the civil service in which alternations in the party in office lead to patronage-style administrative appointments to reward party loyalists.Footnote 23 This became especially striking in the 1980s, when the socialist PASOK governments changed the arena of decision-making by politicising the top echelons of the civil service.Footnote 24 The path dependency of typical party-political patronage is difficult to disrupt and easy to fall back on.

Second, governmental attempts to disrupt authoritarian path dependency, for instance by demilitarisation, alterations in management or staff and operational interests, create additional strong incentives among the governing political party to politicise the intelligence service. After all, the implementation of such disruptive measures requires control over the service. Keeping the service close is a means to control it, to keep its authoritarian legacy in check and, temptingly, to abuse it for political purposes, as the old regime did. In our case study on Greece, we explain how governments fought fire with fire in their attempts to democratise the intelligence service: following an initial period with few attempts to disrupt the service’s authoritarian path dependency (1974–81) , the disruptive measures of the PASOK governments and their successors led to a politicised intelligence service (1981–95) and belatedly renewed attempts at democratisation (1995–2008).

Methodology

To analyse the variation in the degree of politicisation of the Greek intelligence service, we use publications in newspapers, parliamentary debates on the service and original oral history interviews with former Greek intelligence service personnel. This is the first research on the Greek intelligence service based on such a large-scale, longitudinal and diverse empirical data collection.

The Greek press during ‘Metapolitefsi’ reflected and reinforced the political polarisation of the era, often aligning its narratives with the interests and ideologies of political parties. This aligns with Stuart Hall’s insights on the press as an ideological vehicle, shaping public discourse rather than merely reporting facts.Footnote 25 The Greek press is particularly valuable as a source, primarily due to its keen interest in KYP and its successor EYP, driven by two main factors: the demands for greater transparency and accountability of the security forces since 1974, and the political polarisation that led opposition newspapers to exploit scandals within the intelligence community with the aim to undermine the government. Prominent newspapers such as Kathimerini, Ta Nea, To Vima, Rizospastis, Avriani and the journal Anti provide an abundance of detailed information about KYP/EYP, shedding light on various aspects of Greek intelligence history. As this article only has a limited interest in the different ways these newspapers framed the intelligence service, it mostly treats the press as a source of information about developments within EYP, making particular use of Kathimerini, Ta Nea and To Vima for their typically factual reporting. Most newspaper articles are unsigned. This is a common characteristic of the Greek press that has yet to be studied systematically. This phenomenon could be attributed to several factors: a journalistic tradition within the Greek media, an effort by the writer to avoid personal responsibility or an intention by the newspaper to present the article as expressing a collective editorial opinion rather than an individual perspective.

Another source for this research is oral history interviews with eight former employees of KYP/EYP, who entered the service between 1967 and 2004.Footnote 26 They contribute to our understanding of how employees experienced the politicised organisational culture within the service individually. Secrecy makes the use of oral history in intelligence history both challenging and essential. The inaccessibility or (partial) destruction of archival records increases the reliance on oral history that, in turn, has several drawbacks due to the secrecy involved.Footnote 27 Eleni Braat, one of the authors of this article, found the interviewees through the ‘snowball’ method, that is, former employees who came to trust Braat, connected her with others and so forth. Braat tried to avoid a clustering of people in similar age groups, hierarchical level and backgrounds. However, as it is impossible to openly select former intelligence service employees and few are willing to talk, the selection is slightly biased towards a cohort that entered the service around 1974–7 and towards the higher hierarchical levels. The selection is strongly biased towards former civil employees rather than former military employees, because it proved particularly challenging to get in touch with the latter.Footnote 28 To lower the threshold for former employees to share their memories, Braat offered them the option of remaining anonymous, including the removal of information that, when combined with other information, could lead to their identity. This includes information such as socio-economic background, position in the organisation and age. Nearly all of them took part on condition of anonymity. Equally important for the participation of former employees were the non-operational questions that were posed. Rather, questions concerned several aspects of the socio-cultural history of Greek intelligence, of which politicisation and the role of the labour union were only a small part. Questions were openly formulated, allowing interviewees to answer freely and expand beyond the original question. While this method helps make the interviewees comfortable and generous in the information they share with the researcher, the topics in the interviews vary considerably, depending on what the interviewee found important and in which part of the service they were employed. Another possible reason why interviewees may have been generous in their explanations is their possible perception of the interviewer as an outsider to their former professional environment, in terms of national context, age and gender. Moreover, most interviewees seemed to enjoy sharing their memories, often leading to extensive though carefully formulated answers.

Breaking with the Junta Past: A Consensus for Change (1974–81)

From its inception, KYP was inherently politicised. Established in 1953 and modelled on the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), its foremost objective was the surveillance and containment of the Communist opposition. Until 1974, KYP employees were selected solely based on political criteria, with certificates of political beliefs (πιστοποιητικά κοινωνικών φρονημάτων) serving as a prerequisite for public service employment. KYP stood at the vanguard of anti-communism.

In the first six years after the end of the junta regime, parties across the entire political spectrum supported the democratisation of the state, including the intelligence service. Regarding the security apparatus, the conservative government of Nea Dimokratia (1974–81) took the first steps in dejuntification. During this period, KYP appears in the political debate as a former aid of the junta regime, smeared with a bad reputation, but not as a critical exponent of the junta regime. The available literature suggests a similar image of KYP as of secondary importance to the maintenance of the regime, especially compared to the more powerful and brutal military police.Footnote 29 In this period, the political debate on KYP centres on means to distance the service from its junta past in three ways. A first means consisted of the dejuntification of the intelligence service, as part of the dejuntification of the entire public administration. This mainly amounted to the removal of civil servants who had been staunch supporters of the junta regime and had abused their powers at times, or their secondment to parts of the civil service unrelated to their previous position. This did not go as smoothly or radically as the opposition would have liked, or as an anonymous writer with insider knowledge who named himself ‘old soldier’ in his newspaper articles would have wanted.Footnote 30 Dejuntification also included the destruction of its files from the junta period.Footnote 31

Distancing KYP from its junta past also happened through revelations and trials on power abuses by KYP during the junta period. For instance, in 1974 a presumed former agent of KYP came forward and revealed his operational work in the Athens Polytechnic uprising of 1973, when a massive anti-junta revolt ended in bloodshed.Footnote 32 More importantly, trials against former KYP officials of the Thessaloniki unit revealed the service’s use of torture and murder against political opponents of the junta regime. They portrayed the service as not only a bystander of the regime but also an active perpetrator of violence.Footnote 33

Finally, in the post-junta years the conservative government made some modest attempts at democratising the service. KYP was reorganised in a way that confined the service to its ‘strictly national mission’, without focusing on communism, Greek citizens or politicians.Footnote 34 Such a specification of tasks somewhat narrowed the broad authority of the service to provide some protection to citizens for agency overreach. Moreover, in 1976 Georgios Rallis, the Nea Dimokratia minister of the presidency, announced that he ‘has no objection against the formation of a committee that consists of members of each political party who he could inform [on KYP]. However, I cannot inform the entire Parliament. I refuse an in-depth discussion on KYP’.Footnote 35 During this first post-junta period, attempts at greater transparency and parliamentary oversight did not advance much further than the expression of this intention.

Under conservative governmental rule (1974–81), KYP was politically less salient than in the later time periods studied. Only 22 per cent of all articles we studied on the intelligence service in newspaper Kathimerini concerned this crucial period of post-junta democratic embedment of KYP.

Party Patronage and Opposition Control (1981–95)

We observe an increase in politicisation in this period, through both top-down and bottom-up mechanisms.

The 1980s socialist PASOK governments inaugurated a period of intense politicisation of the intelligence service. This politicisation occurred hand in hand with attempts by the socialist government, in particular Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou, to distance the service from its junta past. Formal demilitarisation was a means to break the ties with the junta past and possibly the United States. In combination with a close alignment of the top echelons of the service to the PASOK prime minister, demilitarisation (as part of democratisation process) and politicisation occurred simultaneously. As part of this process, in 1984, KYP moved from the Ministry of the Interior to the prime minister and became the direct responsibility of Andreas Papandreou. In 1986, it formally became a civil (rather than military) service, changing its name from KYP (Central Intelligence Service) to EYP (National Intelligence Service). Throughout this period, Papandreou sought to transform KYP into an instrument for the envisioned ‘Party State’. As Kevin Featherstone puts it, as PASOK, the former ‘out group’, took over power in October 1981, it became concerned to appoint ‘our people’ to replace ‘theirs’.Footnote 36

Despite repeated assurances by the government that the intelligence service did not follow any politicians,Footnote 37 the conservative party Nea Dimokratia started suspecting the opposite in 1985. The discovery of covert listening devices in the conservative party’s offices triggered a formal investigation, which in turn caused one of the greatest political scandals involving EYP.Footnote 38 The wiretapping scandal further escalated after PASOK lost the elections to a coalition government of Nea Dimokratia and centre-left Synaspismos. The coalition government initiated the settlement of the scandals involving the PASOK government between 1981 and 1989 by means of legal proceedings. The wiretapping scandal was one of these scandals. Media attention soared and Andreas Papandreou was prosecuted but never convicted. Interestingly, newspaper articles and parliamentary debates treated EYP as a passive political tool, a client, in the hands of the former governing party, the patron, in particular its former Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou, with little independent agency as a state body. For instance, in 1989 Kathimerini wrote that

Judging from the fact that the recipient of the illegal interceptions was the intelligence service (EYP), which is known to be directly under the control of the prime minister, his own personal responsibilities clearly emerge, those of Papandreou.Footnote 39

Towards the end of 1989, the former head of service Konstantinos Tsimas received increasing attention, independently from Papandreou, but as a member of European Parliament he could not be subjected to any legal proceedings.

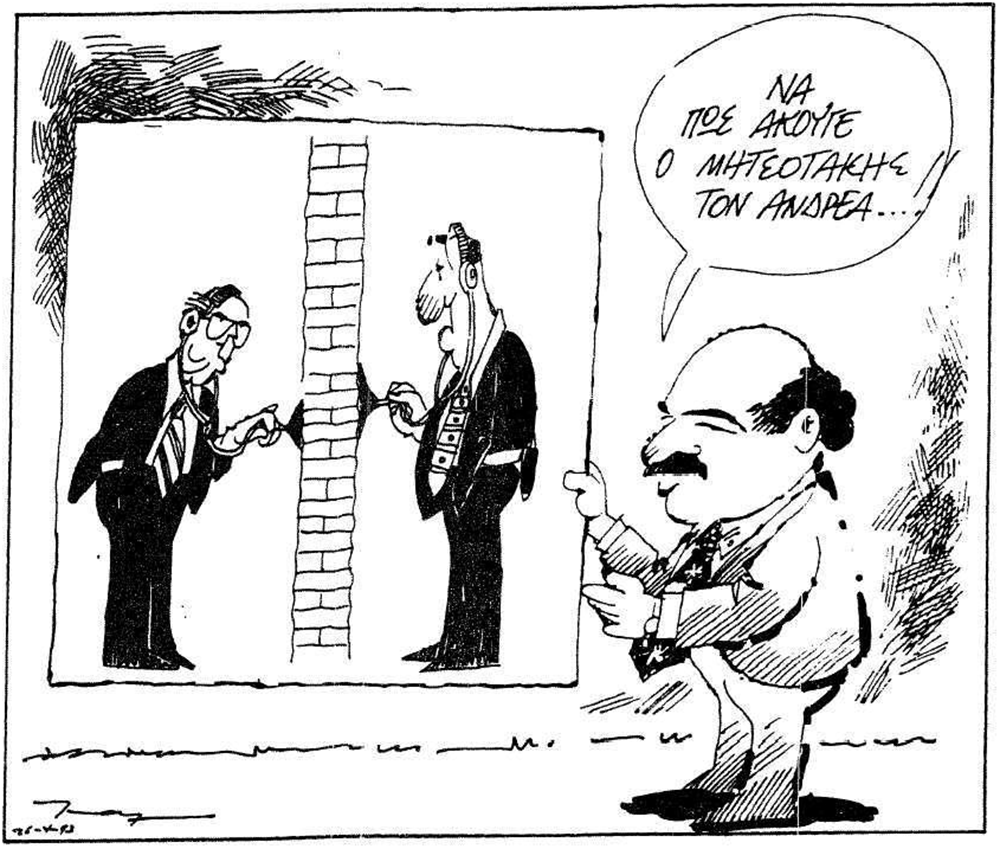

The tables were turned when, in 1993, it became clear that Nea Dimokratia ministers, acting through EYP, had used covert listening devices against PASOK during the period 1989–93, particularly against Andreas Papandreou (see Figure 1).Footnote 40 At the time of the revelation, the Nea Dimokratia government was split and on the verge of losing parliamentary support. According to PASOK, these recent revelations clearly showed

the mechanism of the deep state, that was used unscrupulously to ensure the rise to power of [the leader of Nea Dimokratia] Mitsotakis. The American Watergate scandal pales in comparison to this Mitsotakis-gate.Footnote 41

Figure 1. ‘See How Mitsotakis (leader of Nea Dimokratia) listened in on Andreas (Papandreou)’ (Kathimerini, 27 Apr. 1993, p. 2).

PASOK asked for an investigation into the scandal. Nea Dimokratia agreed under the precondition that the investigation should cover the period since 1985, thus including the presumed eavesdropping by PASOK.Footnote 42

Simultaneously to the phone tapping scandal, which shows a top-down mechanism of politicisation in the sense that the service was partly used for party-political purposes, the intelligence service experienced an internal, bottom-up process of politicisation. The service’s labour union, the Panhellenic Federation of Associations of the National Intelligence Service (POSEYP), having acquired more powers since the formal demilitarisation of the service in 1986, evolved into an important vehicle of socialisation among the service’s civil employees. Through its activities, the labour union played an important role in defining the norms and culture of the intelligence service, and it contributed to the employees’ commitment to the organisation. It had the power to reach a great number of employees, since nearly all of them were union members. Besides negotiating working conditions, such as income, discounts on public transport, assurances and access to hospitals for the armed forces, the labour union organised a range of social gatherings. These included events such as parties and theatre plays, for not only employees but also their spouses and children, and yearly meetings. In 2003, it opened a gym for employees, and every Christmas it handed out prizes, books and ‘expensive’ presents to employees’ children, especially those who excelled in school. Many such social gatherings were organised in not only Athens but also the service’s branches in Thessaloniki and Alexandroupoli. In 2008, the labour union organised an unprecedented, public conference on EYP’s work, with academics, practitioners and journalists as contributors, with the aim to offer more transparency on EYP and arguably to create a better understanding and more sympathy for its work.Footnote 43 Military and police employees, who were temporarily seconded to the service, could not become members of the labour union. This furthered the divide that had become salient as part of the dejuntification process, between them and civil employees.Footnote 44

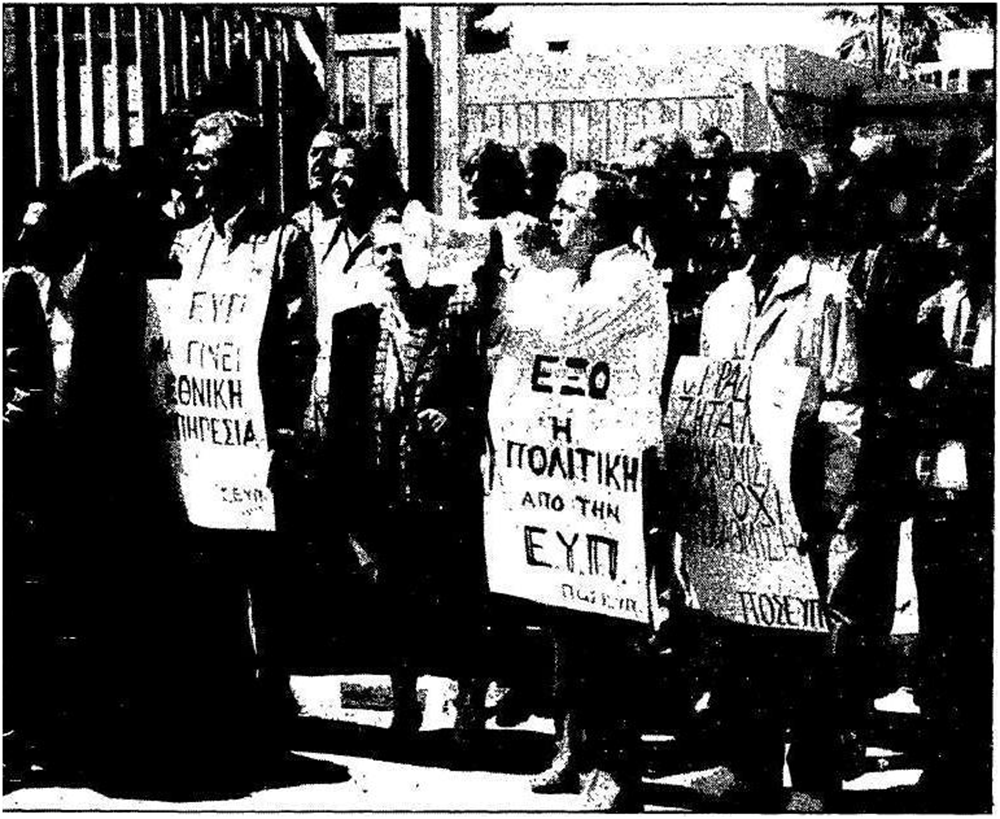

Besides this socialising impact on the civil employees, the labour union heightened the political awareness and agency of civil employees. The union did not always express its discontent discretely, regularly seeking media attention to reinforce its claims. Newspaper articles therefore offer us important insights into the concerns of the labour union and its regular conflicts with the service’s management (see Figure 2). For example, in October 1984 employees went on a three-hour strike between 6 and 9 AM; in November 1987 some employees went on a hunger strike to ask for additional allowances; and in April 1989 employees blocked the entrance of the main EYP offices to protest the secondment of colleagues.Footnote 45 They shouted, ‘We want a dialogue’, ‘Authoritarianism will not pass’ and, addressing the head of service at the time, ‘Tsima, come down and talk with us’, as well as threatening Prime Minister Papandreou with further determined action if he did not comply with their demands.Footnote 46 In 1994, the labour union publicly stated that ‘uncontrolled mechanisms that grow dark and suspicious activities function within EYP’.Footnote 47

Figure 2. Demonstration by EYP Employees from the Labour Union (Kathimerini, 15 Apr. 1989, p. 4).

Personnel shifts, both horizontally and vertically, were another means of politicisation. In the 1980s, the PASOK government made managerial positions in the service temporary, which, in practice, made them political currency. Moreover, such vertical shifts caused considerable turmoil in the service, putting former managers in dependent positions and vice versa. An even greater contribution to the service’s politicised organisational culture was the frequent transfers of employees who entered and left the service. Secondments of military and police officials continued after the intelligence service lost its military nature (in 1986), while such temporary transfers did not only concern positions that required military or police knowledge. Instead, to a certain extent they served as a way for the governing party to control the service.

Such use of seconded employees as political currency had a chaotic effect on the service for several reasons. By the time military and police staff left the service – because of a change of government or the end of their secondment period (usually three years) – they had just become acquainted with their specialised operational work. Moreover, service employees and management worried that their temporary secondment endangered the confidentiality of their work. At times, there were suspicions that some seconded employees unofficially continued running their human sources from their new positions in the military or police. A notorious period of massive civil personnel shifts occurred in 1988–9 when, prior to the elections, EYP hired about 400 employees on top of a total of about 1000 civil employees at the time.Footnote 48 When PASOK lost the elections in 1989, most of them were transferred to other ministries. When PASOK won the elections in 1993, these 400 employees were given the opportunity to return to EYP. According to former EYP head Pavlos Apostolidis, the least qualified did, disrupting the service.Footnote 49 In 1992, Nea Dimokratia staffed part of the intelligence service with politically loyal employees.Footnote 50

Volatile support for parliamentary oversight of the intelligence service reveals that EYP was a much-wanted political instrument for the governing party. While Nea Dimokratia, together with the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), favoured parliamentary oversight in the 1980s, it became diffident regarding the same initiative right after it had beaten PASOK in the elections of 1989.Footnote 51 In 1991 the Nea Dimokratia/Synaspismos government even disapproved of the recurring calls by the opposition for parliamentary oversight, reassuring the opposition that ‘this is not the EYP of Tsimas [under PASOK]’ and that EYP is dedicated to its mission.Footnote 52 This suggests that the position of Nea Dimokratia regarding parliamentary oversight of EYP was based on political incentives. The same could be said of PASOK, which only became a supporter of parliamentary oversight of EYP when the Nea Dimokratia government was on the verge of collapse and under fire for eavesdropping on PASOK.Footnote 53 Only the communist party KKE and the centre-left party Synaspismos, which KYP had systematically targeted throughout the post-war period, were consistent in their repeated requests for parliamentary oversight of EYP.Footnote 54 In 1993, at the height of the Nea Dimokratia eavesdropping scandal, KKE complained that the squabbling between PASOK and Nea Dimokratia for parliamentary oversight was aimed at avoiding any control of EYP.Footnote 55 A year later, Aleka Papariga, the general secretary of KKE, alluded to what she viewed as ‘very clearly a game’ between PASOK and Nea Dimokratia, ‘that we should condemn’.

Neither one [political party] nor the other is interested in transparency, in democracy in OTE [the state telecommunications provider], in EYP. Covert eavesdropping is happening and will continue to happen. We want to reveal this game.Footnote 56

Each scandal intensified the requests of Synaspismos and especially KKE for bipartisan parliamentary oversight, especially throughout 1993 and 1994. These repeated pleas seem to have produced some results, when the National Committee for the Protection of Privacy of Communications was founded in July 1994. Its members, including representatives of each political party in parliament, had considerable powers of oversight regarding EYP and the state telecommunications provider Hellenic Telecommunications Organisation (OTE) . For instance, they were allowed to do unsolicited research in the archives and administration systems of EYP and OTE and to conduct hearings of staff, managers and responsible ministers of the two organisations.Footnote 57

Democratisation and Modernisation (1995–2008)

The period of intense politicisation of KYP/EYP came to an end around 1995. The years between 1995 and 2008 were much quieter from a political perspective. Elected in January 1996, the new prime minister, Costas Simitis, championed a clearer distinction between the party and the state, signalling a departure from the bureaucratic clientelism that had characterised recent history. His approach served as a critique of not only the Andreas Papandreou era but also the practices of Nea Dimokratia.Footnote 58 Simitis’ modernisation programme notably impacted EYP. No longer so much in the limelight, EYP tried to depoliticise its organisational culture in several ways.

A strike prohibition for EYP employees in 1999 hardly made the labour union publicly less visible, in part because on several occasions the service’s management chose to respond to the labour union’s demands with legal action.Footnote 59 The labour union also contributed to deepening political differences between civil employees. The division of the labour union between leaders affiliated with PASOK or Nea Dimokratia and division of the related electoral lists along the lines of these two parties was palpable among employees in the rest of the service. ‘That is, partisanship entered the service. . . . It was the worst thing that could happen’, a former employee remembers.Footnote 60 Another former employee explains why, in his view, such partisanship was detrimental to the service:

I think it was wrong that trade unionism developed in the service, which was partisan up until 1999. ... I believe that political parties should play no role in the service. None. ... If you live your life in a political party, it influences your mind, your thoughts and your judgment in operational matters. ... When you are in this job, you need to take off your hat, your flag, and become something like a machine. Gather data and draw conclusions.Footnote 61

The politically divisive impact of the EYP labour union on the organisational culture of the service was caused by the adherence of its members to a political party. In 1999, minister Vaso Papandreou abolished the internal electoral lists along party-political lines for relevant positions within the labour union, allowing a single electoral list only. ‘It improved the situation a bit’, the former head of service Pavlos Apostolidis remembers, ‘but in my view, there should not have been any list at all. Such a thing as unionism has no place, I think, in an intelligence service’.Footnote 62 Not everybody agreed with him, instead emphasising improved working conditions that the labour union secured, such as pay rises, a gym and several discounts and its socialising impact on the service’s employees.Footnote 63 Former head of service Ioannis Corantis (2004–9) has positive memories of his relations with the labour union.Footnote 64

Another effort to depoliticise the service consisted of attempts to further reduce the number of seconded military and police employees and to restrict them to positions where their expertise was indispensable. Simultaneously, the service tried attracting more qualified, rather than politically loyal, civil employees through open, competitive, merit-based hiring procedures. Such major hiring procedures occurred in 1999, 2001, 2003 and 2005 for positions ranging from intelligence officers to cryptanalysts, ICT specialists, translators, (night) guards, catering staff and chauffeurs.Footnote 65 ‘I believe we had to see what the market had to offer us’, Corantis says, explaining his choice for such open competitions.Footnote 66 These open hiring procedures certainly gave insights into what the market had on offer, as they attracted a great number of applications. In 2003, fifty vacancies for intelligence officers and ICT specialists attracted 11,601 applications,Footnote 67 and in 2005, fifty vacancies attracted 4,500 applications.Footnote 68

During the period of intense politicisation of the intelligence service between 1981 and 1994, successive opposition parties associated the depoliticisation of the service with its democratisation through parliamentary oversight. The 1994 instalment of the oversight committee was the capstone of this period, and the subsequent years had to show its consolidation. The first report of the committee was, according to Kathimerini, ‘disheartening’. It concluded that ‘the covert tapping of each phone remains possible and uncontrollable, whether a phone has old technology, is digital, wireless or mobile’.Footnote 69 However, Kathimerini reported more neutrally on a later report of the committee, where it concluded that state organisations (OTE, EYP) had operated legally in the preceding period.Footnote 70

In 1999, EYP came under fire for its role in the unsuccessful attempts of the Greek government to deny any involvement in the flight of Kurdish PKK leader Öcalan, an incident widely referred to in Greek media as the ‘Öcalan case’.Footnote 71 The Öcalan case refers to the controversial capture of Öcalan, whose planned transit through Greece in 1999 was disrupted, leading to his apprehension by Turkish authorities in Kenya. Even if EYP was not solely responsible for the Öcalan debacle, the former head of service Stavrakakis and three ministers resigned as a result. In parliament and the press, the notorious case triggered demands for the professionalisation and reform of EYP. According to the then Minister of the Interior, Vaso Papandreou, the Öcalan case showed that EYP was ‘the swan song of a mechanism that is based on previous eras and needs radical changes regarding its employees and its structure’.Footnote 72 The nomination of Pavlos Apostolidis as the new head of service, a former ambassador without a clear political signature, was part of this attempt to professionalise the service.

In 2001, EYP moved to the ministry of Public Order, where minister Tsochatzopoulos continued expressing his intention to reform EYP radically. Kathimerini applauded this, concluding that ‘the practice of staffing EYP with military and police officials has failed. [The service] needs a new generation of staff with sound professional training and advanced technological equipment’.Footnote 73 Prime Minister Costas Simitis pursued ‘the renaissance of EYP and its functioning on a professional basis’. Merit-based recruitment would become the norm and, gradually, 400 seconded police officials would be placed elsewhere.Footnote 74 Until 2008, most parliamentary and media attention to EYP did not focus, as before, on its presumed politicised nature, but on its political legitimacy and its democratic embedment, mainly through better oversight.

Conclusion

The challenges that Greek intelligence encountered in its democratisation process were far from unique in a European perspective. The consecutive fall of authoritarian regimes in southern Europe, notably in Spain after Franco’s death in 1975, and later extending to Eastern and Central Europe after the Soviet Union’s collapse, brought similar challenges. This third wave of democratisation demanded a comprehensive reassessment of the functioning of intelligence services, which were previously fundamental to authoritarian governments, within the frameworks of new democracies. Democratic governments were tasked with establishing new objectives for these services, addressing the issues of existing personnel that had served an authoritarian regime and determining how to ensure democratic oversight. At the same time and paradoxically, intelligence services became a powerful instrument that could be used to monitor the opposition.

The politicisation of the Greek intelligence service was especially salient between 1981 and 1995. In the transitional years of adjustment to democracy, which in this article ends in 1981, there was broad political support for a new KYP, even if this was by no means a political priority nor did it receive much media attention. In hindsight and especially compared to the tumultuous years between 1981 and 1995, this crucial post-junta period provided a window of opportunity to distance KYP from its junta predecessor. The Nea Dimokratia government did not seize this opportunity. Instead, demilitarisation remained slow, the renewal of staff was far from radical and the government did not take any initiative towards parliamentary oversight. The establishment of an independent and efficient intelligence service proved challenging, due to a lack of know-how, a deeply politicised organisational culture and an environment in and around the intelligence service that was dominated by party politics. Also, as with other post-authoritarian governments, the Nea Dimokratia government hesitated to involve itself with the remnants of authoritarian regimes, preferring instead to wait for future governments to deal with this political hot potato.Footnote 75

Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou fought the fire of the junta heritage with the fire of party patronage in two stages: to distance KYP from its reputation as a tool of the junta regime, he made the intelligence service into his government’s own tool. By doing this, he created a precedent for Nea Dimokratia to mirror his use of the service after his government had lost the elections. Finally, in the 1995–2008 period, recovering from the political turmoil of the preceding period, EYP continued where the post-junta years under Nea Dimokratia had stopped in 1981: distancing itself from the ‘old KYP’ through an oversight mechanism, taking on more qualified rather than politically loyal employees and consolidating the civil rather than military nature of the service.

The years between 1981 and 1995 showed how the intelligence service became an arena of conflict between government and opposition parties in several ways that reinforced each other simultaneously. Top-down politicisation occurred most conspicuously in the use of the intelligence service for the government’s political goals, namely monitoring the opposition parties to gain electoral advantage. The democratisation of the service, in particular by means of parliamentary oversight, became a political position hypocritically favoured by the opposition until it entered government itself. Less notable to the public eye was the process of bottom-up politicisation. Particularly from 1986, when the service’s labour union acquired more agency, the two-party political system took root in the organisational culture of the service. Employee mobility became easier and more frequent. Between 1995 and 2008 governments increased their efforts to democratise EYP, by means of oversight and consolidating the civil nature of the service. However, EYP engendered lingering hostility and distrust due to its past use as a political tool, arguably more because of the open scandals of the 1981–95 period than the more distant junta years.

In November 2024, the Greek intelligence service unexpectedly announced an initiative to declassify parts of its archive, in line with a legal obligation to do so since 2008. Together with this announcement, it declassified a limited set of documents on the Cyprus question, dating back to July and August 1974. These documents provide no insights into the service’s role in Greece’s domestic politics.Footnote 76 The service announced it will continue to declassify documents, even on sensitive political issues, although it remains unknown what precisely will be declassified and when this will happen.Footnote 77 It is likely, however, that current and future declassification efforts by EYP will attract more academic interest in the service’s history. Building on this article and depending on future declassified files, further research could focus on the service’s own agency in dealing with party-political influence and how its politicisation influenced its effectiveness.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Financial support

This research has been funded by the Dutch Research Council.