Introduction

Hydrogels, with their unique ability to form stable three-dimensional networks through physical or chemical cross-linking of polymers (hydrophilic or hydrophobic) and clays, have become highly versatile materials with numerous applications. Hydrogels are highly versatile materials with significant applications in pharmaceutical and cosmetic fields. In the pharmaceutical field, their stand-out feature is their capacity to provide controlled drug release in topical applications. This property is particularly beneficial, as it allows for more effective and prolonged administration of medications, thereby improving treatment adherence and minimizing side-effects (Mahinroosta et al., Reference Mahinroosta, Jomeh, Allahverdi and Shakoori2018; Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Câmara, García-Villén, Viseras, Júnior, Machado, Câmara, Farias, Moura, Dreiss and Raffin2021; Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Leite, García-Villén, Sánchez-Espejo, Cerezo, Viseras, Faccendini, Sandri, Raffin and Moura2022).

Hydrogels, with their high water content and gentle, gel-like consistency, are used extensively in the cosmetics industry. They are particularly beneficial in skincare products, where they provide hydration, soothing effects, and anti-aging benefits. Their ability to carry ingredients such as vitamins, anti-oxidants, and peptides to the skin is a key factor in enhancing the efficacy of these formulations (Bah et al., Reference Bahú, Andrade, Barbosa, Crivellin, Pioli, Souza, Viktor and Souto2022). This is a clear demonstration of how hydrogels can improve the performance of skincare products significantly (Mohapatra et al., Reference Mohapatra, Mirza, Hilles, Zakir, Gomes, Ansari, Iqbal and Mahmood2021).

In the formation of hydrogels, hydrophilic polymers such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyacrylic acid (PAA), and natural polymers including alginate, chitosan, and gelatin, are predominantly employed due to their ability to form stable, three-dimensional networks through physical or chemical cross-linking (Peppas et al., Reference Peppas, Bures, Leobandung and Ichikawa2000; Lee and Mooney, Reference Lee and Mooney2012). These hydrophilic polymers are essential for creating hydrogels with high water retention and swelling capacities, crucial for controlled drug delivery and skin hydration applications. Furthermore, the integration of hydrophobic polymers like polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), and polycaprolactone (PCL) enhances the mechanical strength and modulates the degradation rates of the hydrogels, making them more suitable for specific therapeutic uses (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chang, Chan, Chung and Shu2022).

In addition to the organic polymers, incorporating inorganic materials, particularly clay-based hydrogels, introduces unique properties that are advantageous for medical treatments. Clays can be categorized into natural, synthetic, and modified types, with natural clays such as those from the smectite group (e.g. montmorillonite and saponite) notable for their significant swelling capacity and water-retention abilities. These characteristics impart beneficial rheological properties to the hydrogels, such as enhanced viscosity and elasticity, which are critical for their performance in physical medical treatments (Bergaya and Lagaly, Reference Bergaya, Lagaly, Bergaya, Theng and Lagaly2006). The synergistic combination of inorganic clays with organic polymers in hydrogels thus holds great promise for developing advanced materials with tailored thermal and rheological properties for targeted therapeutic applications. Synthetic clays, such as Laponite®, are engineered to have specific properties that enhance their performance in hydrogel formulations. Laponite® is a synthetic hectorite clay that is often used to improve the mechanical properties, stability, and rheological behavior of hydrogels (Stealey et al., Reference Stealey, Gaharwar and Zustiak2023).

Modified clays, such as organo-modified montmorillonite, are treated chemically to improve compatibility with various polymers and to enhance mechanical strength and thermal stability. Organo-modified clays are used widely in hydrogel formulations to achieve these enhancements. For example, organo-montmorillonite has been incorporated into polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogels to improve their mechanical properties and thermal stability, making them suitable for biomedical applications (Kokabi et al., Reference Kokabi, Sirousazar and Hassan2007).

Smectitic clays, including bentonite (Veegum®), can form hydrogels in aqueous media due to the formation of delaminated dispersions resulting from the self-assembly of their nanodiscs via face–edge aggregation. Veegum®, a magnesium silicate clay, belongs to the smectite group and has gained prominence in developing hydrogels for therapeutic purposes. The general chemical formula of Veegum® is (Na,Ca)0.33(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2⋅𝑛H2O(Na,Ca)0.33(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2·nH2O, where n represents the variable amount of interlayer water (Viseras and Lopez-Galindo, Reference Viseras and Lopez-Galindo1999; Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Hosseini, Jafari and Taheri2018; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Galdino, Trigueiro, Honorio, Barbosa, Carrasco, Silva-Filho, Osajima and Viseras2022).

These laminar phyllosilicates, consisting of an octahedral sheet sandwiched between two tetrahedral sheets (2:1 structure), possess a TOT (tetrahedral-octahedral- tetrahedral) structure and can retain a significant amount of water in the interlayer spaces (Santos et al., Reference Santos, França, Castellano, Trigueiro, Silva Filho, Santos and Fonseca2020; da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, França, Rodrigues, Oliveira, Trigueiro, Silva Filho and Fonseca2021). Studies have demonstrated that Veegum®-based hydrogels exhibit ideal rheological properties and moisture retention for applications in skin care, controlled drug delivery, and other topical therapies (Moraes et al., Reference Moraes, Bertolino, Cuffini, Ducart, Bretzke and Leonardi2017; Viseras et al., Reference Viseras, Sánchez-Espejo, Palumbo, Liccardi, García-Villén, Borrego-Sánchez, Massaro, Riela and López-Galindo2021). The ability of Veegum® to enhance the stability and efficacy of hydrogels makes it a valuable component in advanced formulations for health and regenerative medicine (Ramos-Tejada et al., Reference Ramos-Tejada, Ontiveros, Plaza, Delgado and Durán2003).

The inclusion of clay enhances the mechanical strength and durability of hydrogels, making them suitable for applications where structural integrity is paramount. The gelation process in these hydrogels involves complex mechanisms, including physical cross-linking and electrostatic interactions between clay particles and polymer chains, which are critical for their performance in both drug delivery (Iliescu et al., Reference Iliescu, Andronescu, Ghitulica, Voicu, Ficai and Hoteteu2014; Cavalcanti et al., Reference Cavalcanti, Fonseca, da Silva Filho and Jaber2019) and cosmetic applications (López-Galindo et al., Reference López-Galindo, Viseras, Aguzzi, Cerezo, Galán and Singer2011; Ruggeri et al., Reference Ruggeri, Sánchez-Espejo, Casula, Sandri, Perioli, Cardia, Lai and Viseras2023). Understanding these mechanisms is essential for designing and applying hydrogels that can deliver drugs and cosmetic ingredients effectively while maintaining their structural properties.

The unique properties of hydrogels, such as their viscoelastic nature, allow them to undergo significant deformation without breaking, and to respond to environmental stimuli such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength (Peppas et al., Reference Peppas, Bures, Leobandung and Ichikawa2000). Additionally, their capacity to form films on the skin surface contributes significantly to their application in healthcare and regenerative medicine. This film-forming ability provides a moist environment that facilitates healing, making hydrogels particularly effective in promoting tissue repair and regeneration (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Hu, Zhang, Fan, Chen and Wang2024).

The formation of clay gelling structures is a complex process, dependent on factors such as the type of clay minerals dispersed, pH, and ionic strength (Lagaly and Ogawa, Reference Lagaly, Ogawa, Bergaya, Theng and Lagaly2006). These structures, influenced by the specific interactions between the clay particles and their environment, form intricate networks that enhance the rheological properties of clay-based hydrogels. Understanding these aggregation mechanisms and the hierarchical structure of clay mineral powders is a crucial step toward optimizing hydrogel performance in various applications, particularly in developing advanced materials for physical medical treatments.

The detailed mechanism of clay swelling in water was reported recently by Pavón and Alba (Reference Pavón and Alba2021). Clay swelling can be categorized into three regions based on the clay volume fraction: crystalline swelling, osmotic swelling, and Brownian expansion. The formation of a physical gel in aqueous clay dispersions occurs predominantly within the osmotic swelling region. In this region, electrostatic repulsion between the clay layers drives their expansion. It is believed that lowering electrolyte concentration can effectively exfoliate the clay, enhancing this swelling behavior. Clay particles in water tend to form a ‘house-of-cards’ structure, driven by electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged faces of the clay layers and the positively charged edges. This configuration contributes significantly to the unique rheological properties observed in clay-based hydrogels.

Peats are complex mixtures of mainly humic and fulvic acids resulting from vegetable wastes transformed under anaerobic conditions, and are used in topical health care and cosmetology (Beer et al., Reference Beer, Grozeva, Sagorchev and Lukanov2003; Summa and Tateo, Reference Summa and Tateo1999). Therapeutic effects of these natural active ingredients are supposedly due to both physical (thermal and mechanical) and chemical (humic and fulvic acids) mechanisms. In a previous study, the composition and properties of some peats were studied (García-Villén et al., Reference García-Villén, Sánchez-Espejo, Carazo and Borrego-Sánchez2018), concluding that improvement of rheological and thermal properties of the systems should be advisable.

In this way, the present study aimed to design and fully characterize mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels, composed of pharmaceutical-grade clay and an organic material (peats) as the solid phase, with mineral medicinal water as the dispersion medium. The goal was to optimize the technological, biopharmaceutical, and therapeutic properties of the resulting preparation.

Materials and methods

Materials

The clay used in the present study was Veegum® F (VF), a magnesium aluminum silicate with pharmaceutical-grade clay (Vanderbilt Ltd, USA), commercialized as a pharmaceutical excipient, fulfilling the requirements included in the pharmacopoeia monographs (European Pharmacopoeia 8.0; USP 32). Peat (P) was provided by Turbera del Agia (Padul, Granada, Spain) and the mineral medicinal water, referred to hereafter as ‘Graena water’, came from the thermal spring of Graena (Cortes y Graena, Granada, Spain).

Mineralogical and chemical composition

X-ray diffraction (XRD) data and chemical analysis (major elements) of VF were used to assess sample identity, purity, and richness. Mineral quantification was based on the measurements of peak areas in the XRD patterns and corrected with chemical data using the XPOWER ® program (Granada, Spain). The XRD analysis was performed using a Philips® X-Pert (Philips, Holland) diffractometer equipped with an automatic slit (CuKα, 4–70°2θ, 6° min–1, 40 kV) both on bulk random and oriented aggregated samples. Major elements were determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF), using a Bruker® S4 Pioneer instrument (Bruker, MA, USA) with a Rh X-ray tube (60 kV, 150 mA). The characterization of mineral components and major elements present in the P was carried out in the total sample dried at 40°C (P-40) and after calcination at 750°C (4 h) (P-C), under the same conditions and equipment as used for VF.

Elemental analysis

The P sample was subjected to elemental analysis to determine carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur by using an elemental analyzer (Flash 2000 model, Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK), equipped with an autosampler, an oven, a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) detection system, a chromatographic column, a trace S detector and a control, calculation, and data processing computer system, connected to two precision microbalances (Mettler M-3, Mettler XP-6, Greifensee, Switzerland).

Scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the textures of the clay particles and their aggregates was performed using a GEMINI (FESEM) instrument (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Samples were dried at 40°C for a minimum of 48 h. Powdery samples were then mounted over standard aluminum stubs and coated with carbon.

Cation exchange capacity

VF powders and P (1 g) were dispersed in 25 mL of tetramethylammonium bromide (TMAB) aqueous solution (1 M), in order to displace their constituent cations. Dispersions were shaken overnight at 50 rpm and then filtered. The TMAB was used as a leaching agent to strip off all four ions: K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. The TMAB replaced the cations as the methyl groups are a good electron withdrawal entity; this increased the positive charge on nitrogen. The bromide ion reacted easily with the cations and the tetramethylammonium bromide would react with the OH-group of the clay mineral being analyzed. Cations in solution were assayed by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) (Optima 8300 ICP-OES spectrometer, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and cation exchange capacity (CEC) was calculated as the sum of exchangeable cations, expressed in meq per 100 g of dry powder. For the blank it was the same solution, minus the sample.

Thermal analysis of peat

Thermogravimetric analysis (TG, DTG) was carried out using a Mettler Toledo (Greifensee, Switzerland) device model TGA/DSC1 with FRS5 sensor and a microbalance (precision of 0.1 μg) in air atmosphere, over a range of 35–950°C and heating at a rate of 10°C min–1.

Particle-size distribution of peat

A Malvern® Mastersizer 2000 LF granulometer (Malvern, UK) was used to determine the particle size of peat. Before the analysis, a few milligrams of peat powder were dispersed in purified water using a sonication bath. Three replicates were performed for each test.

Preparation of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

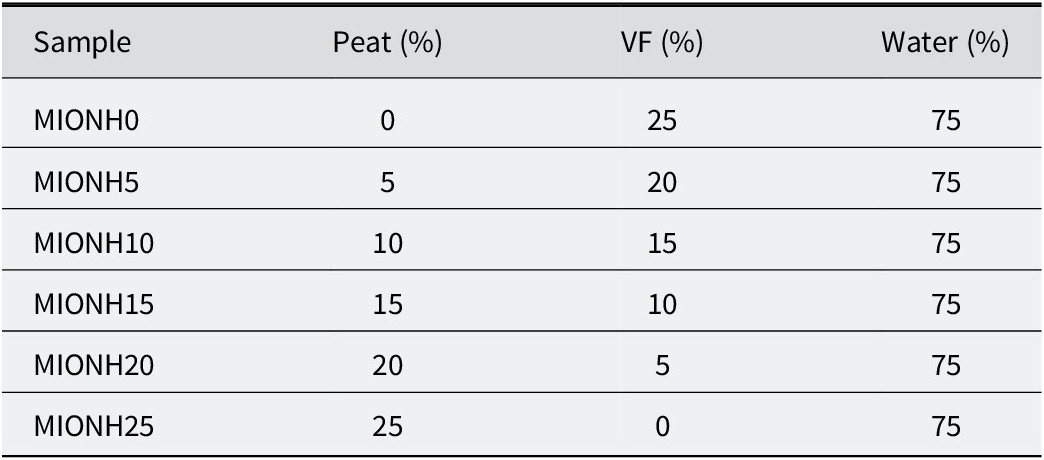

To prepare mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels (MIONHs), P and VF powders were suspended in Graena water using a turbine stirrer (Silverson Machines Ltd, Chesham, UK) at 8000 rpm for 5 min and left to swell for 48 h. The P powder was obtained by oven drying at 100°C. For all MIONHs obtained, the relative solid/liquid ratio was maintained at 25/75 (w/w), and various organic/inorganic component (P/VF) ratios of the solid phase were used (Table 1). Rheological analysis, pH, and thermal analysis were carried out to characterize and determine the stability of MIONHs.

Table 1. Composition of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

Rheological properties of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

Rheological measurements were taken immediately after interposition and allowed to swell for 48 h, using a controlled rate viscometer (Thermo Scientific HAAKE, RotoVisco 1, Karlsruhe, Germany) and HAAKE RheoWin software (Karlsruhe, Germany). Rheological measurements of samples MIONH10, MIONH15, MIONH20, and MIONH25 were performed using a cone/plate configuration (DC60/2°). For MIONH0 and MIONH5, due to their greater viscosity, a plate/plate sensor (P20 TiL S) was employed. Measurements were carried out at 25°C after a rest time of 90 s. A Peltier temperature-controlled measuring plate for parallel plate (TCP/P, HAAKE unit) was used to control measurement temperature. The rheological properties of the MIONHs were measured over the shear rate range of 70–800 s–1. Both temperature and shear rates were selected as representative of the stress produced by skin spreading (10–200 s−1), manual mixing (100–200 s−1), or container removal (400–2000 s−1). Rheological characterization included flow curves obtained with increasing and decreasing shear rate and the apparent viscosity of the systems. Six replicates were performed on each sample.

Rheological modeling of hydrogels

The rheological behavior of the hydrogel formulations was evaluated through flow-curve measurements performed at two aging times (t 0 and t 48h), in both ascending and descending shear rate ramps. The experimental data were fitted using two widely adopted non-Newtonian models: the Cross model and the Carreau–Yasuda model. The Cross equation is given by Eqn (1) and Eqn (2), respectively:

where η0 is the zero-shear viscosity, η∞ is the infinite-shear viscosity, k is the time constant, and m is the dimensionless rate constant describing the shear-thinning transition.

The Carreau–Yasuda equation is expressed as:

where λ is a characteristic relaxation time, a is a dimensionless parameter controlling the transition sharpness, and n is the power-law index. Non-linear, least-squares regression (Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm) was used to estimate the model parameters from shear stress versus shear rate (τ vs γ̇) data. The quality of fit was evaluated by the coefficient of determination (R 2) and the relative root mean square error (RMSE%).

In both cases, parameter estimation was carried out via non-linear, least-squares regression with relative error weighting to ensure balanced contributions from both low- and high-stress regions of the curve. To prevent numerical singularities at γ̇ = 0, a small offset (ε) was introduced inside the rate term. Fits were performed independently for the loading (up) and unloading (down) branches of the hysteresis loop to capture potential thixotropic effects.

The fitted parameters and their physical interpretations were as follows:

η₀: zero-shear viscosity (Pa·s);

η∞: infinite-shear viscosity (Pa·s);

m (Cross): shear-thinning index (–);

k (Cross): rate constant (s), with the critical shear rate γ̇c = 1/k;

λ (Carreau–Yasuda): relaxation time (s);

a (Carreau–Yasuda): transition width parameter (–);

n (Carreau–Yasuda): high-shear power-law index (–);

S: shear-thinning strength, defined as S = log10 (η0/η∞).

Thermal properties of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

Cooling kinetics were studied following the study of Cara et al. (Reference Cara, Carcangiu, Padalino, Palomba and Tamanini2000) and the procedure described by Khiari et al. (Reference Khiari, Mefteh, Sánchez-Espejo, Cerezo, Aguzzi, López-Galindo, Jamoussi and Viseras2014) and Sánchez-Espejo et al. (Reference Sánchez-Espejo, Aguzzi, Cerezo, Salcedo, López-Galindo and Viseras2014). Briefly, known amounts of MIONHs were conditioned at 50°C in a cylindrical polyethylene terephthalate cell and then immersed in a thermostatic bath at 25°C, measuring the cooling of the samples up to 32°C (skin temperature), by means of a thermometric probe located in the center of the cell. Experimental cooling data were fitted using the Newton law, describing thermal exchange between two bodies in contact at different temperatures. Experimental thermal parameters of the samples studied were then obtained using Eqn (3) and Eqn (4):

where T min is room temperature (25°C), T max is the initial temperature (50°C, considering the application temperature), t is the time (min) and k is a constant that depends on the material and apparatus, given by:

where P is the instrumental constant of the apparatus, C is the heat capacity of the heated material, m is the heated mass, and C p is the specific heat. The apparatus constant was obtained following Cara et al. (Reference Cara, Carcangiu, Padalino, Palomba and Tamanini2000) by fitting of cooling data obtained with a known amount of a reference water suspension of TiO2.

pH of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

The pH of all studied MIONHs was measured using a pH meter Crison pH 25+ (Crison Instruments S.A., Barcelona, Spain), equipped with a 5052T semi-solid sensor (also from Crison Instruments).

Results and Discussion

Mineralogical and chemical composition of Veegum® F

The mineralogical composition and major element content of VF agree with previously reported mineralogical and chemical properties, which demonstrated that VF is composed (>85% w/w) of intermediate mineral phases between di- (montmorillonite) and tri- (saponite) octahedral smectites (Aguzzi et al., Reference Aguzzi, Viseras, Cerezo, Rossi, Ferrari and Lo2005; López-Galindo et al., Reference López-Galindo, Viseras and Cerezo2007). VF is a pharmaceutical-grade clay, and the results obtained confirm that its identity, purity, and mineralogical properties are appropriate for its use as a pharmaceutical excipient in semi-solid dosage forms (Viseras and López-Galindo, Reference Viseras and Lopez-Galindo2000; López-Galindo et al., Reference López-Galindo, Viseras and Cerezo2007). It meets the regulatory requirements for pharmaceutical clays, further supporting its suitability for pharmaceutical formulations (Viseras et al., Reference Viseras, Aguzzi, Cerezo and Lopez-Galindo2007; Aguzzi et al., Reference Aguzzi, Sánchez-Espejo, Cerezo, Machado, Bonferoni, Rossi, Salcedo and Viseras2013).

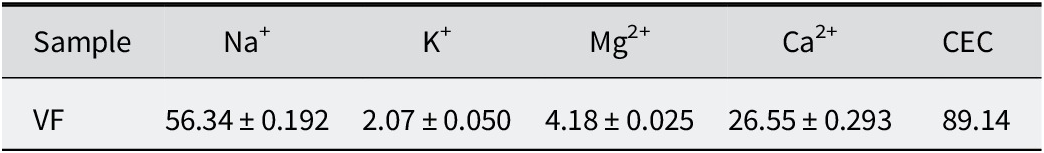

Cation exchange capacity of Veegum® F

The concentration of individual exchangeable cationic species and the total CEC of the VF sample are shown in Table 2. The total CEC was 89 meq per 100 g. Exchangeable species were mainly Na+ and Ca2+, with amounts reaching 63% and 30% of the total, respectively. The presence of Na+ and Ca2+ confirmed the composition reported in mineralogical and chemical composition.

Table 2. Exchangeable cations (meq per 100 g) (means±SD; n=3) and CEC of VF

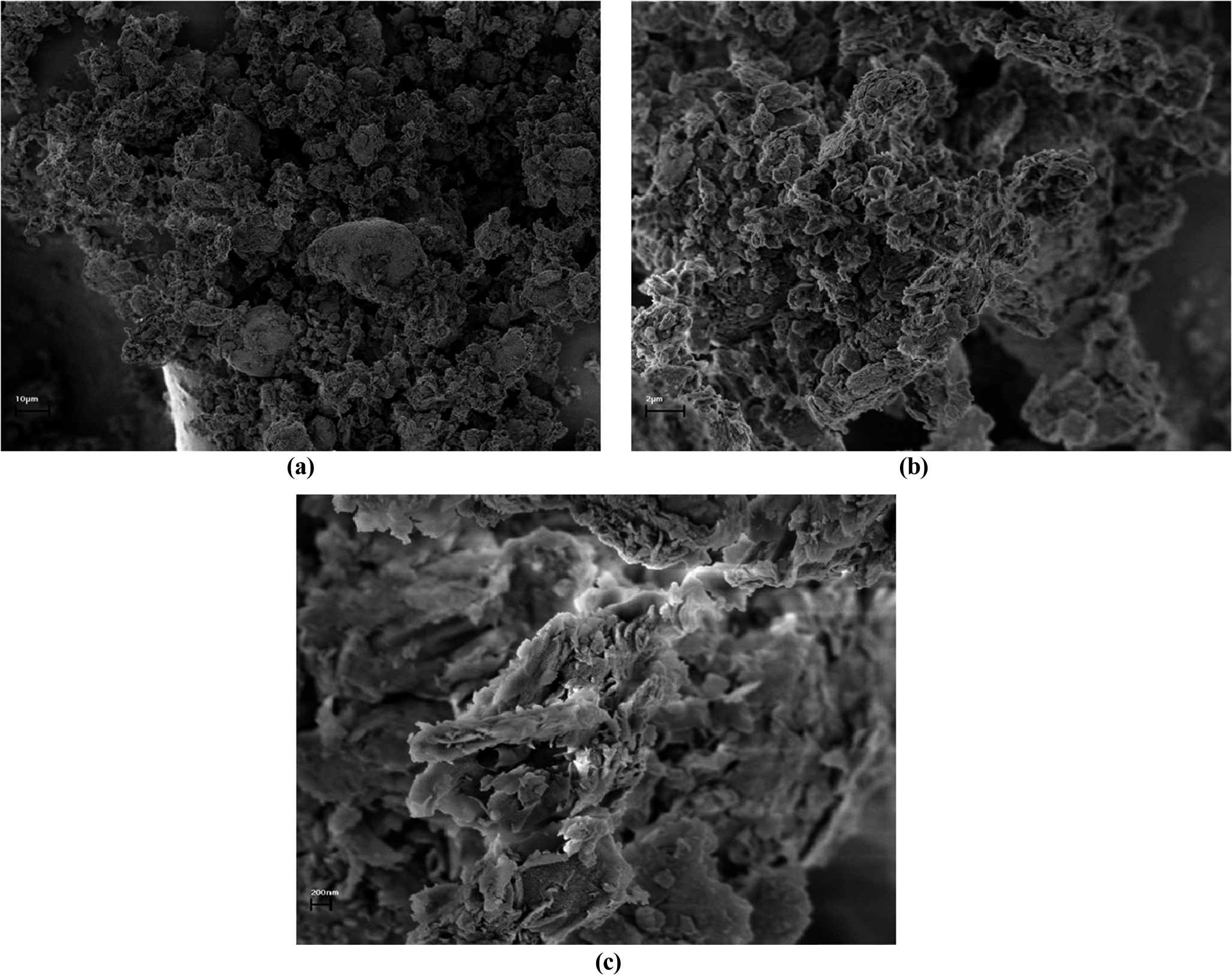

Scanning electron microscopy

The morphology of VF particles was investigated further by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to complement the mineralogical and elemental analyses. The micrographs revealed irregular aggregates of lamellar platelets, characteristic of smectitic clays, arranged in porous, loosely packed structures (Fig. 1). At greater magnifications, individual platelets displayed well-defined edges and occasional curling, indicative of partial delamination during sample preparation. This structure is consistent with the known composition of VF, which is rich in montmorillonite and saponite and imparts the large specific surface area and interlayer spacing characteristic of these smectitic minerals. The observed ‘house-of-cards’ arrangement, arising from face–edge electrostatic interactions between platelets, is closely associated with the swelling capacity and cation exchange properties of VF, and accounts for its ability to form stable, thixotropic networks in aqueous dispersions.

Figure 1. SEM images of VF prepared as described in the methodology (dried at 40°C, mounted on aluminum stubs, and carbon-coated), showing: (a) low-magnification image of irregular aggregates of lamellar platelets; (b) intermediate magnification revealing the porous, loosely packed ‘house-of-cards’ arrangement typical of smectitic clays; and (c) high magnification highlighting well-defined platelet edges and occasional curling, indicative of partial delamination during preparation.

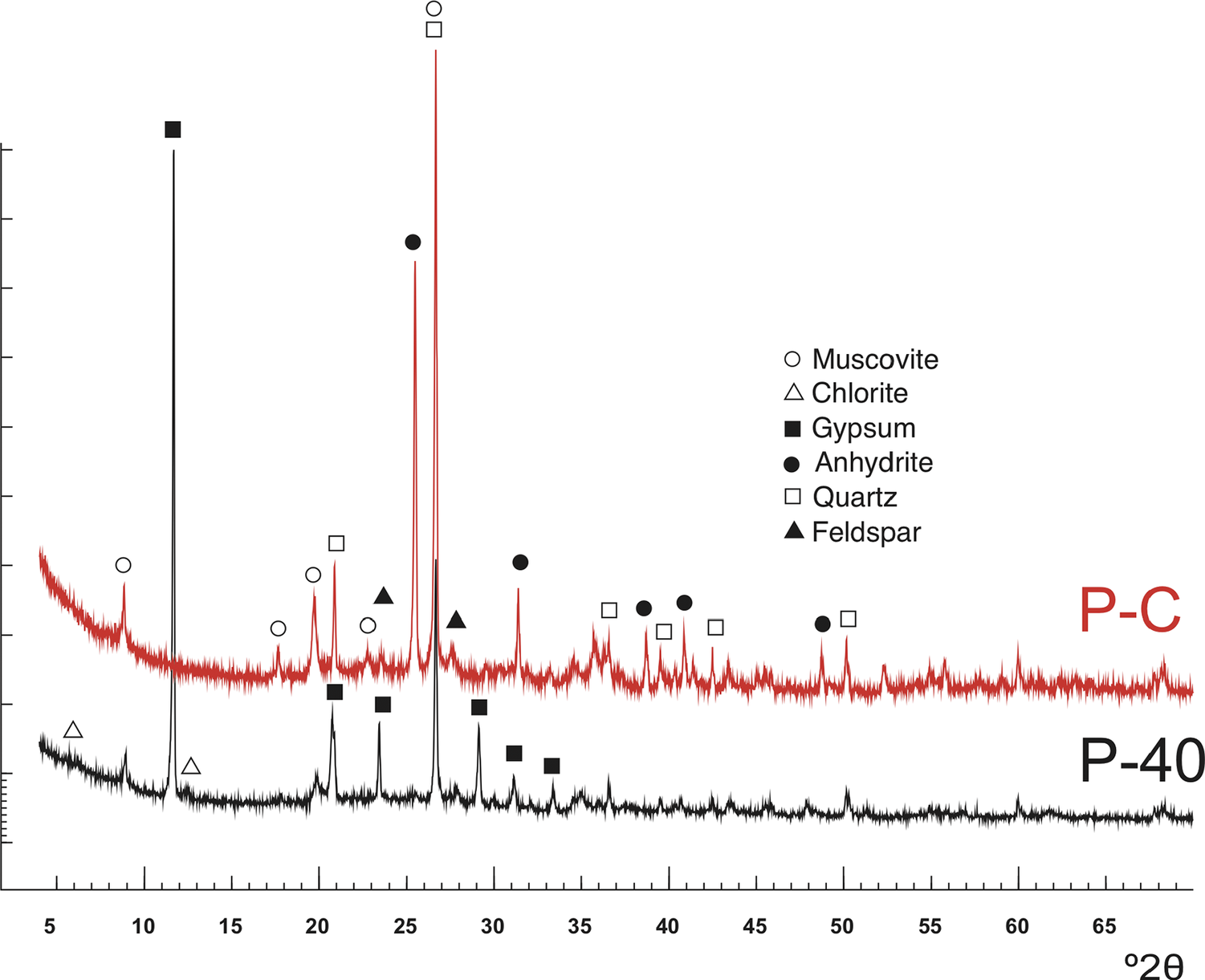

Mineralogical and chemical composition of peat

The mineralogical composition of the P sample dried at 40°C (P-40) and after calcination (750°C, 4 h) (P-C) was determined based on XRPD patterns (Fig. 2) and chemical composition (Table 3). According to the XRD pattern, the sample was composed mainly of gypsum, mica, quartz, and feldspar, with traces of chlorite. After calcination, gypsum gave rise to anhydrite, as expected.

Figure 2. XRD patterns of the peat sample dried at 40°C (P-40) and after calcination (P-C).

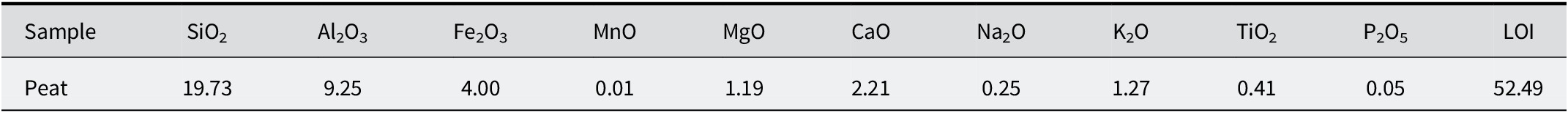

Table 3. Major-element content (w/w %) of the peat sample

LOI = loss on ignition.

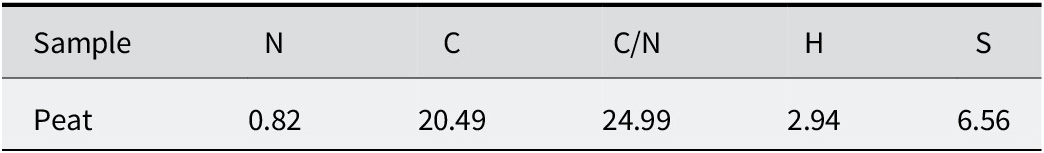

Elemental analysis of peat

The results of elemental analysis of peat samples were 2.66% N, 65.83% C, 9.64% H, and 21.88% S, relative to the total (Table 4). The carbon was derived from organic matter as the sample had not carbonated. The nitrogen behaved similarly to carbon and corresponded to organic matter. The C/N ratio (Table 4) showed the degree of decomposition of organic matter. In the peat studied, it was ~25, which corresponded to a medium–high degree of decomposition. The hydrogen was mainly associated with the organic matter, moisture, and gypsum present in the mineral fraction.

Table 4. Elemental analysis of the peat sample

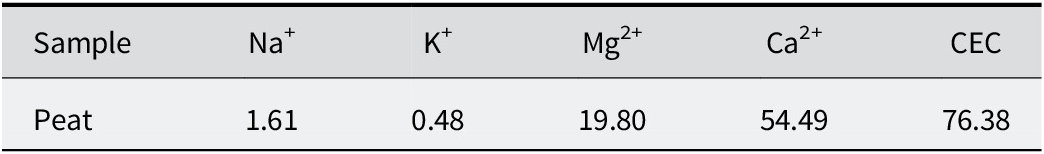

CEC of peat

The concentration of individual exchangeable cations and the total CEC of the peat sample are shown in Table 5. The total CEC was 76 meq per 100 g. The main exchangeable cation was Ca2+, representing ~71% (54.59–76.38 meq per 100 g) of the total.

Table 5. Exchangeable cations (meq per 100 g) and CEC of the peat sample

Thermal analysis of peat

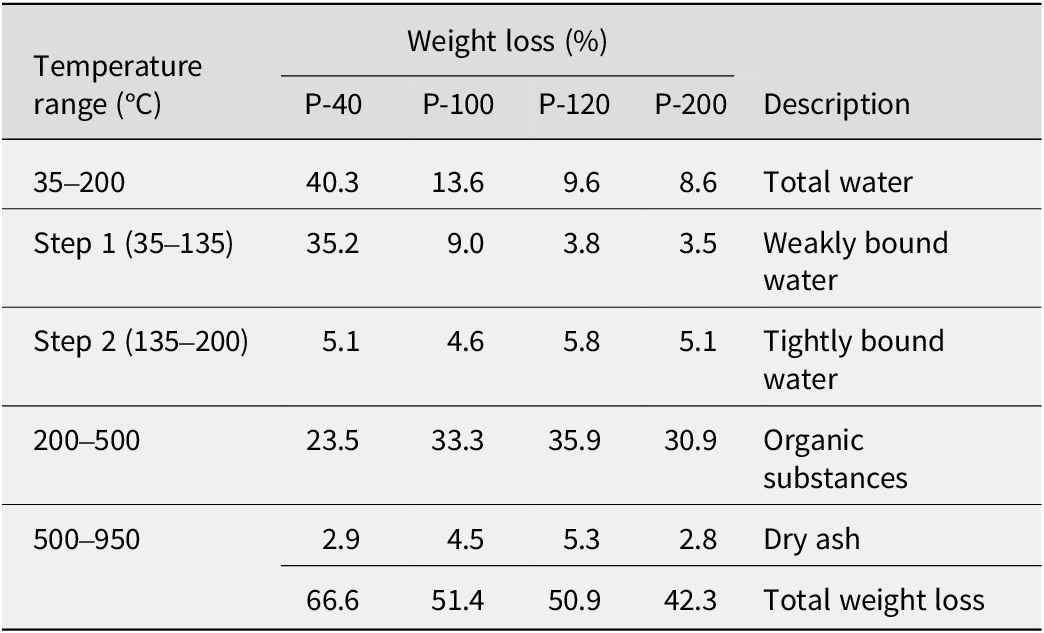

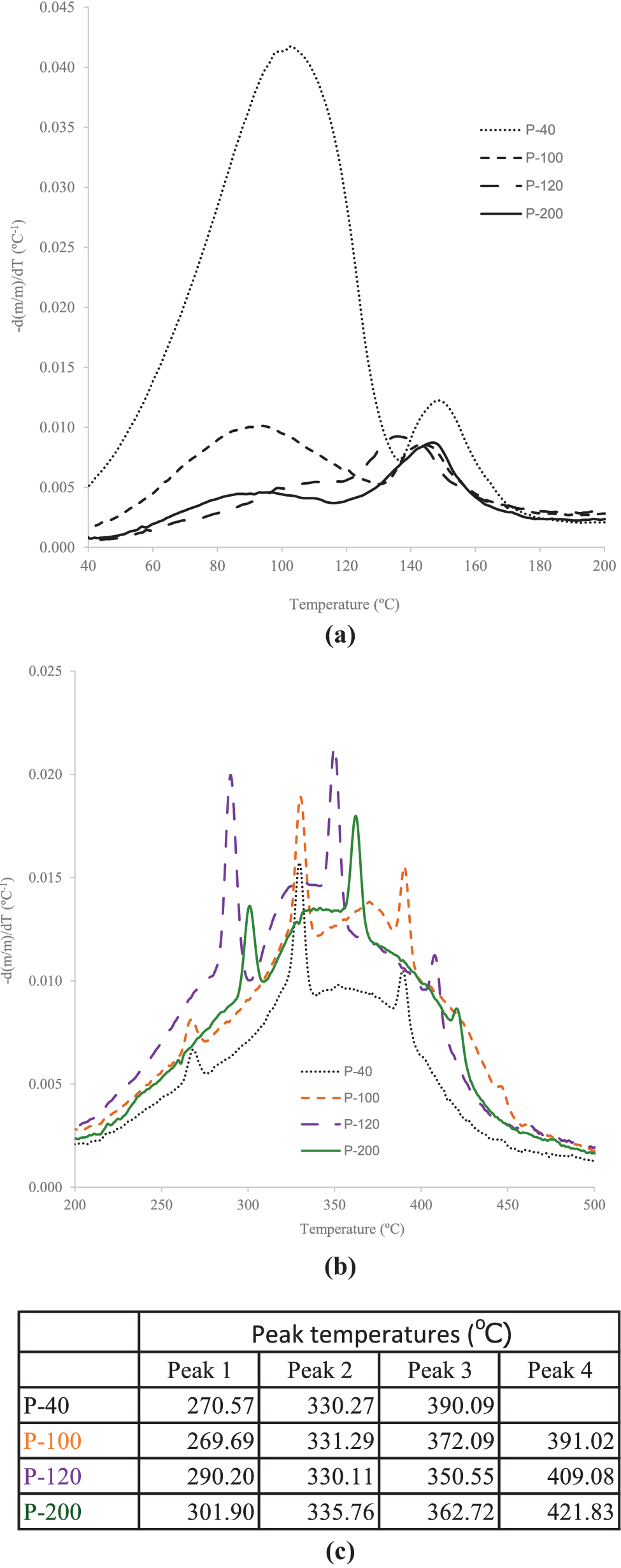

The formulation of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels (MIONHs) requires mixing and homogenizing of the organic (peat) and inorganic (Veegum® F) solids prior to their dispersion in mineral medicinal water. Pre-drying of the components under conditions that do not alter their composition is essential for this. To evaluate the drying effect, peat was dried in an oven at various temperatures (40, 100, 120, 200°C) and subsequently analyzed for moisture and combustion content of organic matter by thermogravimetric analysis. In a TG analysis the mass of a sample in a controlled atmosphere is recorded continuously as a function of temperature or time as the temperature of the sample is increased. The mass loss of the peat samples over various temperature ranges are reported in Fig. 3 and Table 6. As demonstrated by TG, after drying at 40°C, the peat sample still contained ~40% w/w of water, reducing to values of ~10% w/w when heating to 100°C, and then remained constant up to 200°C.

Figure 3. TG curves of peat samples.

Table 6. Weight loss of the peat samples over various temperature ranges

Differential thermogravimetric curves (Fig. 4) showed that water evaporation took place in two successive stages. The first stage (Fig. 4a) corresponded to weakly bound water, and was sensitive to the pre-drying of the samples. The second stage (Fig. 4b) was related to the removal of tightly bound water, which had an approximate value of 5% w/w of the total mass. Furthermore, in the second stage the quantity of bound water remained practically unchanged and was independent of the previous drying temperature of the sample. From 200°C, combustion of organic matter occurred, with three DTG peaks corresponding to degradation of polysaccharides and other organic components (265–300°C), followed by carbon formation (330–360°C) and its oxidation (390–420°C) (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhao and Liu2011). Above 500°C, only dry ash (inorganic material) remained.

Figure 4. DTG curves of peat samples: (a) the phase of weakly bound water loss; (b) the phase of strongly bound water loss; (c) temperatures of the main peaks.

The DTG curves of the peat samples dried at 40°C (P-40) and 100°C (P-100) were almost identical, indicating that drying up to 100°C did not modify the thermal behavior of the organic matter significantly. However, drying at higher temperatures caused shift of the main DTG peak towards higher temperatures, and a decrease in magnitude of the weight loss, suggesting partial degradation of the organic components of peat. As observed in Fig. 4, residual moisture content after drying at 100°C and 120°C was comparable, but heating at 120°C could induce some compositional changes, resulting in shifts of the peaks in the 200–500°C interval. Consequently, peat dried at 100°C (with DTG curve almost identical to sample P40 in the interval 200–400°C) was selected for all subsequent experiments.

Particle-size distribution of peat samples

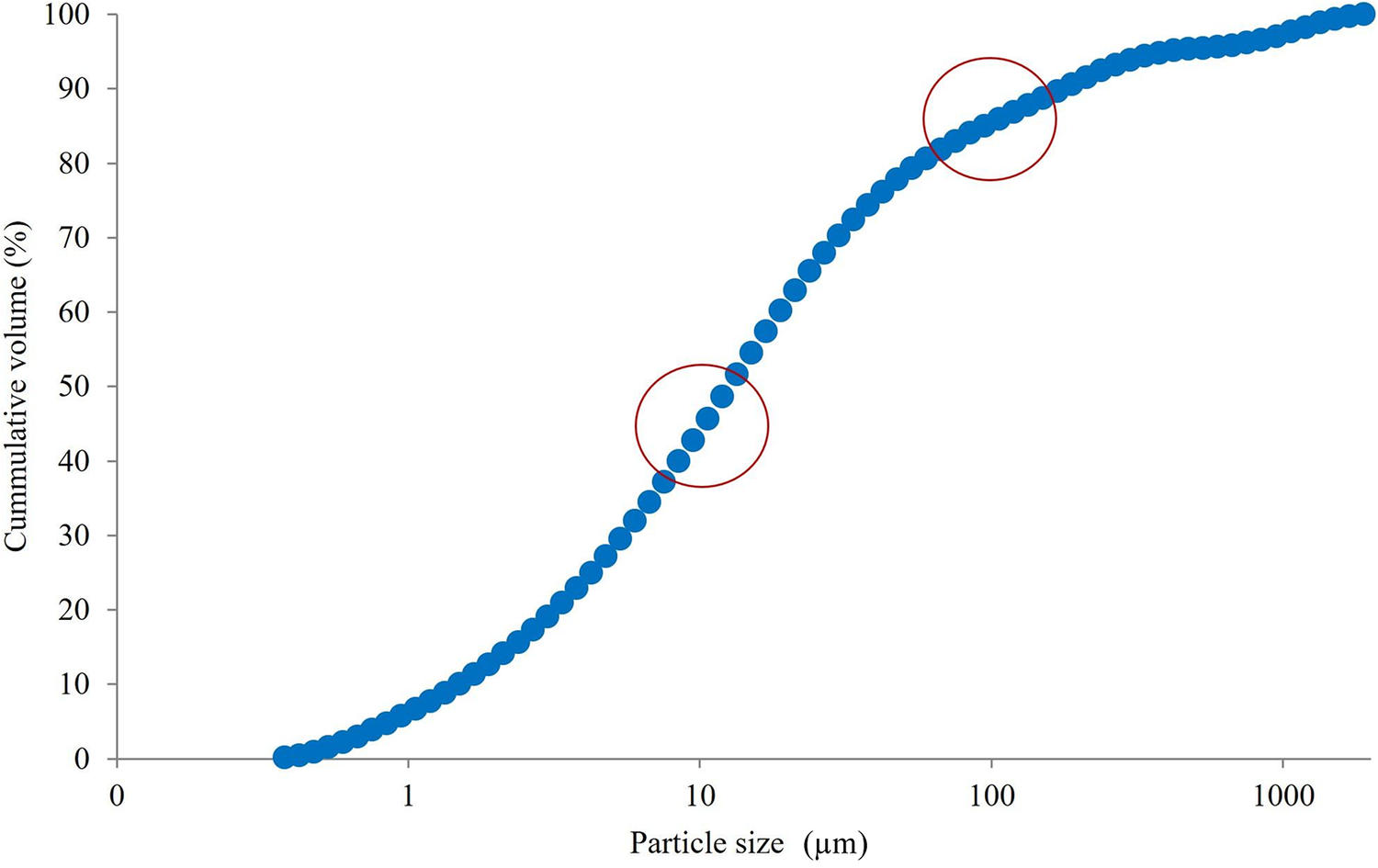

The pathogenic inhalator potential of particulate matter (dust) is related to the mineral composition, e.g. the presence of crystalline silica or chemical impurities, but also to the physical properties and particle-size distribution. Depending on their size, particles of raw materials used to prepare MIONHs could become hazardous to worker health, particularly when suspended in air. The particle size of respirable dust that is harmful to human health is in the range of 10 μm and below (Gharpure et al., Reference Gharpure, Heim and Vander Wal2021). Smaller airborne particles of dust, which can remain suspended in air for hours, pose a greater risk to the respiratory system when inhaled. Particles having a diameter of >10 mm are expected to be deposited in the nasopharyngeal region, whereas particles of <5 mm may reach the bronchial and alveolar regions. With this premise, a detailed particle-size distribution of the sample was mandatory.

The granulometric distribution of the peat sample was predominantly unimodal and provided a detailed profile of particle dimensions and the proportion of fine fractions. The cumulative particle-size distribution (Fig. 5) was used to estimate the fraction of particles likely to be deposited in the alveolar region of the lungs when inhaled (respirable dust). More than 90% of the particles exhibited diameters of <100 μm, and >40% were <10 μm, values that are relevant for both handling safety and functional performance in the hydrogel formulations. Consequently, preventive measures to control dust exposure should be implemented during powder handling and dispersion preparation. When considered alongside the SEM observations of VF, these granulometric data contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the morphology and particle characteristics of the solid components employed in this study.

Figure 5. Particle-size distribution of peat. The circles show that >90% of the particles are <100 μm in diameter and >40% of the particles are <10 μm in diameter.

Rheological properties

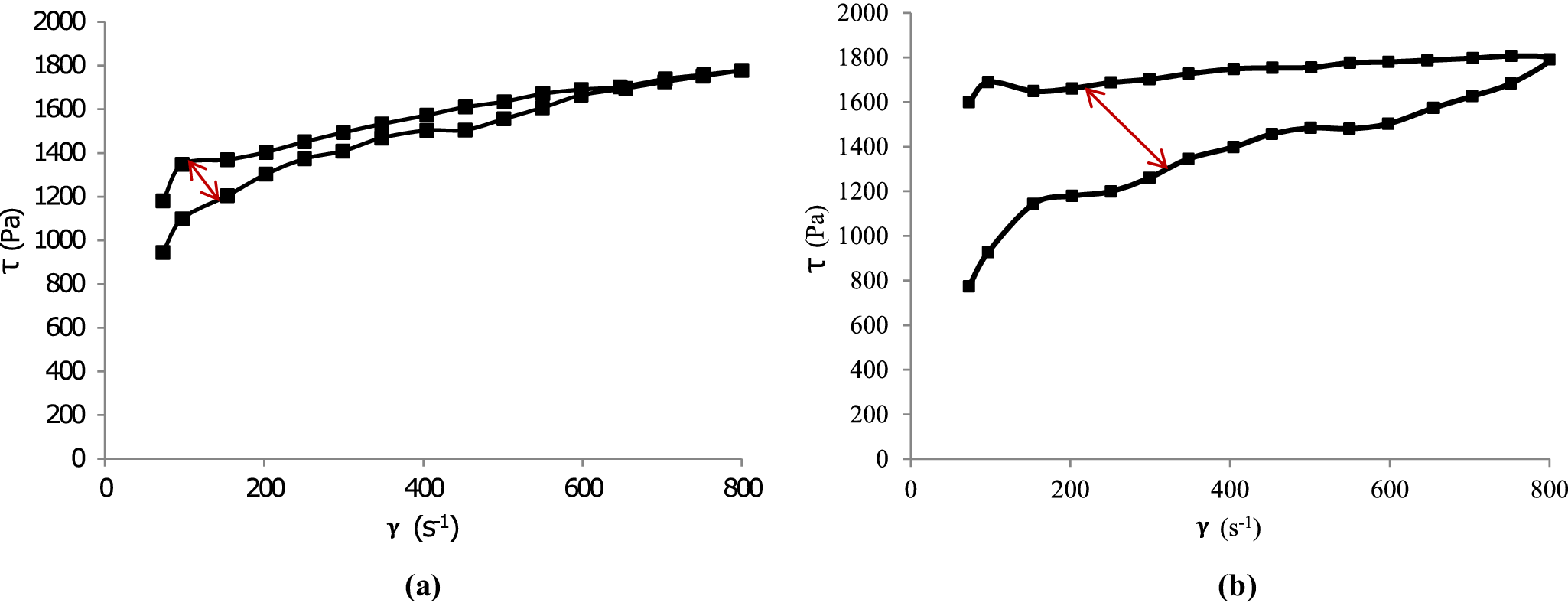

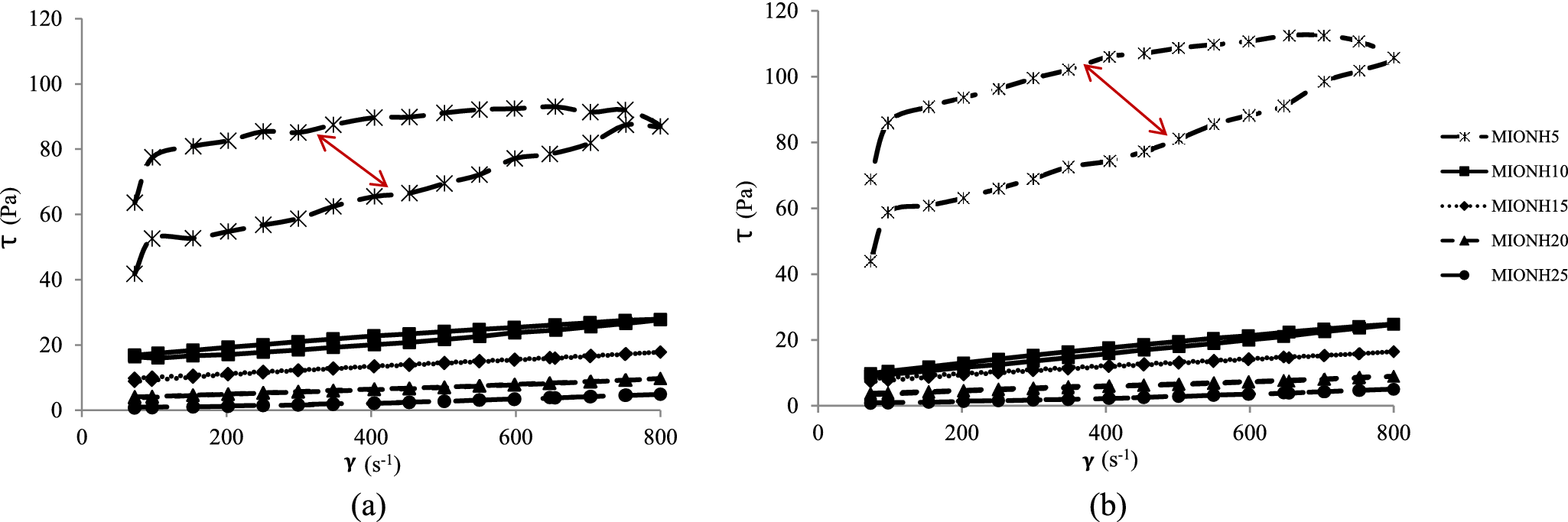

All MIONHs obtained showed typical non-Newtonian viscoplastic flow curves. This flow was independent of the composition and maturation time. MIONHs prepared with only VF (MIONH0) or peat (MIONH25) as well as those prepared with a VF-P mixture (MIONH5, MIONH10, MIONH15, MIONH20) showed similar profiles, with minor differences depending on the composition and measuring time (Figs 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Flow curves of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogel (MIONH0:VF suspension) at 0 h (a) and after 48 h (b). The red arrow indicates the change in hysteresis area.

Figure 7. Flow curves of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels at 0 h (a) and after 48 h (b). The red arrows indicate the changes in hysteresis area.

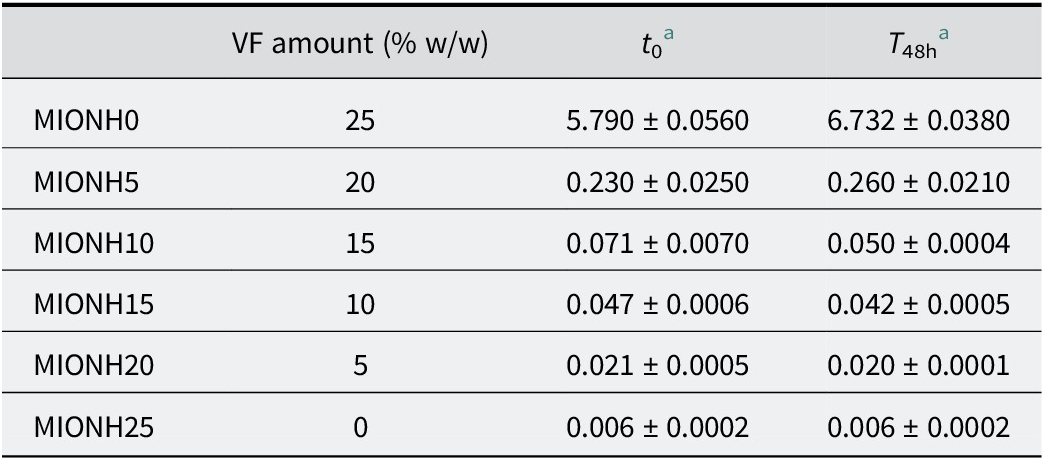

MIONH0 showed high viscosity and thixotropy, which increased after 48 h of swelling (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the hysteresis area of MIONH0 after 48 h of swelling ( Fig. 6b) was larger than that of the non-swollen sample (Fig. 6a). This result can probably be attributed to the formation of a more stable gel due to the increased crosslinking of VF fibers over time. This agrees with previous data, which demonstrated that the hysteresis area of Veegum® HV hydrogels increased with progressing maturation time (Aguzzi et al., Reference Aguzzi, Sánchez-Espejo, Cerezo, Machado, Bonferoni, Rossi, Salcedo and Viseras2013). On the other hand, MIONH25 (peat dispersion) showed very low viscosity and no thixotropy (Fig. 7) at both swelling times. The profile of the flow curves prepared with mixtures of both materials (MIONH5–20) increased, as expected, with the VF concentration. This effect was not linear, and a significant increase was observed in MIONH5 (Fig. 7). It can be postulated that VF particles require a minimum concentration to produce a structure with interesting rheological properties. To compare and follow this concentration effect, it is useful to obtain apparent viscosities from the flow curves. The values of apparent viscosities at 250 s–1 are shown in Table 7, where the influence of the VF concentration is evident and the threshold occurred at 20% w/w of VF concentration.

Table 7. Apparent viscosities (Pa·s; 250 s–1, 25°C) of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels at 0 h and after 48 h

a Values ± SD; n = 6.

The flow curves at t 0 and t 48h (Fig. 7) showed a reduction in hysteresis area, consistent with the decrease in apparent viscosity values reported in Table 8. These trends agree with the Cross and Carreau–Yasuda model fits, which captured accurately the non-Newtonian, shear-thinning behavior and its evolution over time. Both the Cross and Carreau–Yasuda models provided an excellent description of the non-Newtonian, shear-thinning behavior of the hydrogels, with coefficients of determination (R 2) between 0.99 and 1.00 and relative RMSE values generally <0.05. The Cross model consistently yielded stable and physically interpretable fits across all conditions. For instance, at t 0 (loading branch), η0 values ranged from 0.019 Pa·s (P25) to 404 Pa·s (P15), η∞ from 0.00569 to 0.0872 Pa·s, and the shear-thinning exponent, m, from 0.99 to 3.00. The corresponding critical shear rates (γ̇c) spanned from 0.0206 s⁻¹ (P15) to 96.7 s⁻¹ (P5), while the shear-thinning strength (S) varied between 0.524 (P25) and 4.58 (P15).

Table 8. Thermal parameters of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

a Values ± SD; n = 3.

In the unloading branch, most samples exhibited either reduced η₀ and/or increased γ̇c relative to the loading branch, indicating thixotropic behavior. After 48 h, several formulations showed decreased η0 and increased γ̇c, suggesting partial microstructural breakdown or rearrangement over time. For example, P5 (loading branch) decreased from η0=0.914 Pa·s and γ̇c=96.7 s⁻¹ at t 0 to η0=0.797 Pa·s and γ̇c=131 s⁻¹ at t 48h.

The Carreau–Yasuda model achieved a similar quality of fit (R 2≈0.99–1.00). However, in some cases, particularly when loading at t 0, the parameters a and n were weakly identifiable (very large a and n approaching zero). Despite this, the trends in λ and η0/η∞ mirrored those from the Cross model, reinforcing the robustness of the shear-thinning characterization.

At t 48h, the Cross model maintained high-quality fits, although changes in η0 indicated structural evolution of the gels. For instance, P15 exhibited a decrease in η0 from 354 Pa·s, consistent with partial network relaxation. The Carreau–Yasuda parameters corroborated these observations, with λ and n adjustments reflecting altered microstructural dynamics.

Analyses of the descending ramp revealed similar trends but with minor hysteresis, further supporting the presence of thixotropic effects. Collectively, the temporal evolution of the parameters confirmed that both models are suitable for quantifying the time-dependent, non-Newtonian behavior of these hydrogels. Nevertheless, the Cross model provides a more compact and physically interpretable parameter set, η0, η∞, m, γ̇c, and S, that effectively captures both shear-thinning and thixotropic characteristics.

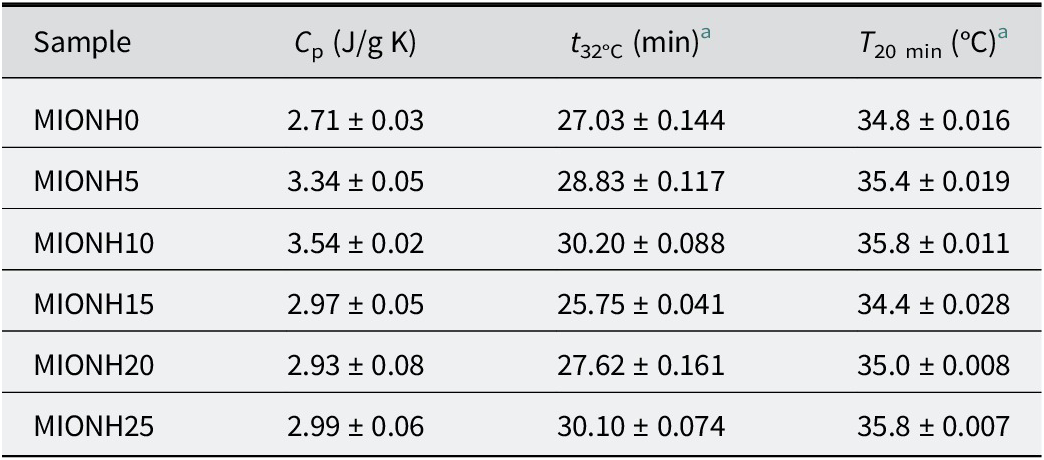

Thermal properties of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

Experimental specific heats of the MIONHs are shown in Table 8. The experimental values of specific heats were similar to those measured in analogous systems by other authors (Legido et al., Reference Legido, Medina, Mourelle, Carretero and Pozo2007; Cara et al., Reference Cara, Carcangiu, Padalino, Palomba and Tamanini2000; Casás et al., Reference Casás, Legido, Pozo, Mourelle, Plantier and Bessires2011; Caridad et al., Reference Caridad, Ortiz de Zárate, Khayet and Legido2014; Khiari et al., Reference Khiari, Mefteh, Sánchez-Espejo, Cerezo, Aguzzi, López-Galindo, Jamoussi and Viseras2014; Sánchez-Espejo et al., Reference Sánchez-Espejo, Aguzzi, Cerezo, Salcedo, López-Galindo and Viseras2014). In many of these works, it has been shown that the specific heat capacity of these systems depends mainly on the water content and secondarily on the composition of the solid phase. All of the prepared MIONHs had the same water content (75% w/w) and the differences in specific heat values were minimal. From a practical point of view, it was interesting to evaluate the time required to achieve 32°C (t 32, °C) (skin temperature) as well as hydrogel temperature after 20 min (T 20 min) (minimum typical time of application of hydrogels), calculated from the fitting of cooling curves (R 2>0.9999 in all cases). The time required for MIONHs to achieve 32°C was in the range 25.8–30.2 min and T 20 was ~35–36°C, assuring heat transfer between the prepared MIONHs and the skin in normal application procedures. No influence of the composition was observed in the thermal parameters studied. This is in agreement with the hypothesis that the thermal behavior of hydrogel is mainly dependent on the water content of the systems.

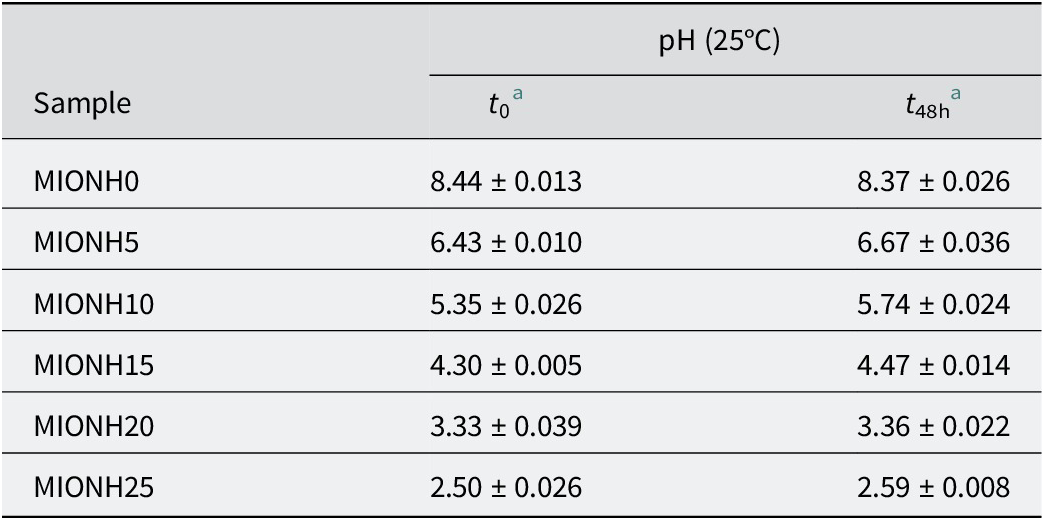

pH studies of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

The pH of the MIONHs at 0 h (t 0) and after 48 h (t 48) are shown in Table 6. Those values were in the range 2.50–8.44 (Table 9). The MIONHs (MIONH5–20) showed intermediate values between those of the pure components (MIONH0 and MIONH25), allowing a complete interval of pH values. It is interesting that MIONH5 and MIONH10 showed pH values near to that of the skin (5.0).

Table 9. pH of mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels

a Values ± SD; n = 3.

Conclusions

The inorganic clay (Veegum® F) studied is mainly composed of di- (montmorillonite) and tri- (saponite) octahedral smectites and, in particular, it may be considered as a ‘sodium smectite’. In addition, although Veegum® F is a commercial clay with a known composition, its physicochemical characterization was performed to ensure batch consistency and suitability for the intended application. Variability in mineral content, particle-size distribution, or moisture level between batches could impact the performance and stability of the hydrogel formulations. For its use as a pharmaceutical excipient, Veegum® F must be of high purity, have no toxic elements, have controlled swelling behavior, and have adequate hydration capacity, in accordance with pharmacopeial standards (e.g. those set by the United States Pharmacopeia, USP). These parameters influence directly its safety and functionality in topical or therapeutic formulations. The peat studied contains a large proportion of water hydration (40% w/w). The dried sample captures moisture and keeps it at ~10% (w/w). The mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels showed flow curves which are dependent on the clay content. The mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels with minimal VF concentration (20%, w/w) showed apparent viscosities suitable for their topical application together with thixotropic character that allowed physical stability during storage.

The specific heat capacity of the mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels was independent of the solid-phase composition. The values of hydrogel temperature after 20 min (T 20 min) and the time required to achieve 32°C (t 32) were suitable for its use as a thermal therapeutic agent. The mixed inorganic/organic natural hydrogels studied are potentially useful as semi-solid formulations, with interesting synergies between the components. Inorganic components influence rheological properties significantly, whereas organic components influence pH and thermal behaviors to a lesser extent.

The preparation of the hydrogel formulations by blending clay with peat, although not widely practised, presents a promising advancement in the medical use of these semi-solid systems. This formulation not only capitalizes on the distinct benefits of both inorganic and organic materials but also paves the way for more effective, customizable, and sustainable therapeutic options.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article.

Author contribution

Conceptualization, R.d.M.B. and R.S-E.; methodology, P.C., C.C. and R.P.; formal analysis, C.C., and R.P.; investigation, L.D.M. and R.P.; resources, L.D.M. and C.V.; data curation, L.D.M. and R.S-E.; writing-original draft preparation, C.C.; writing-review and editing, R.d.M.B. and F.C.; visualization, R.S-E.; supervision, P.C., L.D.M. and C.V.; project administration, R.d.M.B. and R.S-E.; funding acquisition, R.d.M.B., C.V. and L.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Spanish project PID2022-137603O13-100 of the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. R.d.M.B. wishes to acknowledge the EMERGIA Program Project 2022/00001046 (Junta de Andalucía, Universidad de Sevilla, Spain) (contract number USE 23922-W).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.