Introduction

The year 2021 was still marked by the Covid-19 pandemic. Throughout the year, political processes took place in the context of the ‘special situation’ under the Federal Law of Epidemics and, thus, with a more important role of the federal government compared with normal times. In this context, the Swiss electorate voted twice on referendums about the Covid-19 law, which served as the legal basis for the Federal Council to mitigate the negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic on society and the economy. While in both cases the citizenry clearly backed the government, the referendums were a reflexion of a relatively strong movement against the pandemic governance in Switzerland. The pre-pandemic's most important issue (i.e., the climate crisis) remained on the political agenda. While the ‘green wave’ of the 2019 national elections spilled over to the cantonal elections, in June 2021 citizens rejected the revised CO2 Act at the ballot.

Election report

No national elections were held in Switzerland in 2021.

Cantonal (subnational) elections took place in the cantons of Valais, Fribourg, Solothurn and Neuchâtel. In all these cantonal elections, the two trends of the previous national elections continued. First, the proportion of women elected grew (Seitz Reference Seitz2021), particularly in the canton of Neuchâtel where the share of female Members of Parliament increased by 24 percentage points. Second, the two parties with the ‘green’ label, namely the Green Liberal Party (GLP/pvl) and the Green Party (GPS/pes), again made significant gains in vote share, meaning the ‘green wave’ of the 2019 national elections continued at the cantonal level in 2021. At the same time, the two large parties of the political left and right, that is, the Social Democrats/Sozialdemokratische Partei/Parti Socialiste (SPS/PSS) and the Swiss People's Party/Schweizerische Volkspartei/Union démocratique du centre (SVP/UDC), lost seats in many cantons and also did The Liberals/FDP.Die Liberalen/PLR.Les Libéraux-Radicaux (FDP/PLR). The FDP/PLR, as well the newly merged party ‘The Center’ (see Political party report), struggled to stabilize their vote shares. Similar to the national parliament in the last national elections, many cantonal parliaments thus became greener, but not necessarily more left-wing.Footnote 1 These latest developments will also contribute to an interesting starting position with regard to the next national elections in late 2023. In view of the recent cantonal election results, the demand of the ecological parties to receive seats in the consensual federal government is not likely to weaken.

Referendums

The quarterly dates of federal votes are fixed and announced in advance. In 2021, all four dates were used, with Swiss voters deciding on 13 ballot proposals (Tables 1–4).

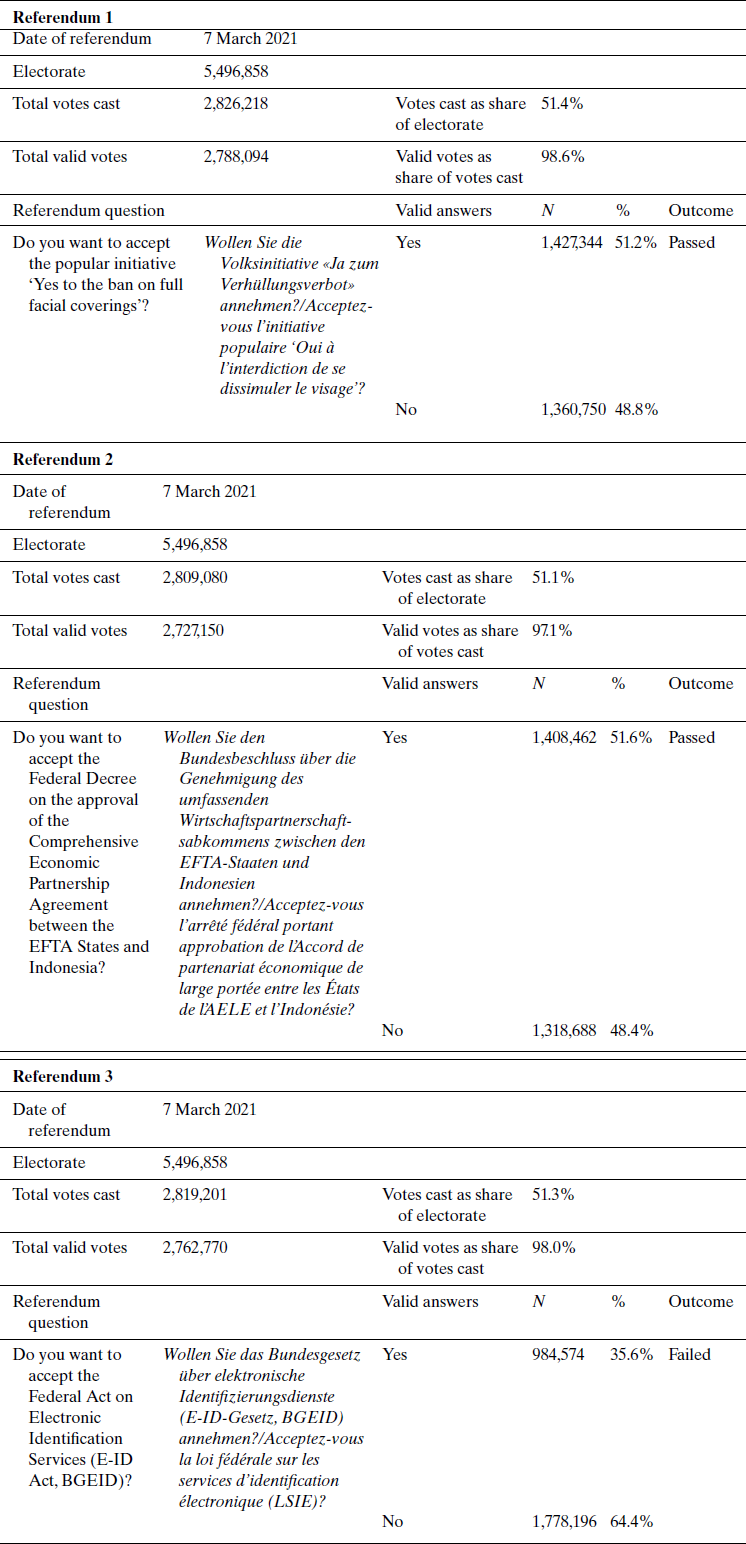

Table 1. Results of three referenda held on 7 March 2021 in Switzerland

Source: The Federal Chancellery (2021).

The first ballot votes of the year took place on 7 March (Table 1). The popular initiative ‘yes to a ban on full facial coverings’ demanded that no one in Switzerland should be allowed to cover their face in places accessible to the public, that is, on the street, in official offices, on public transport, in football stadiums, restaurants, shops or in the great outdoors. Exceptions would only be possible in places of worship and other sacred places, as well as for reasons of safety, health, climatic conditions and local customs. The initiative was accepted by a small majority of 51.2 per cent of voters and 20 cantons, and thus became the first successful popular initiative since 2014. The post-ballot survey reveals that the most important reasons to accept the initiative were related to cultural considerations and arguments about internal security. Moreover, the display of the niqab and burqa was seen as potentially misogynistic – although a majority of women voted against the initiative (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe and Rey2021a: 4).

The second proposal of the day was a referendum on the approval of the economic partnership agreement with Indonesia. As Switzerland is an European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member, voters primarily weighed the economic potential of the agreement with Indonesia against the protection of the environment – especially the production and trade of palm oil. The referendum was called for by the Swiss Farmers’ Union and supported by members of the GPS/PES and a part of the SP/PS (Ammann Reference Ammann2020). However, the economic potential of the agreement finally prevailed with 51.6 per cent yes-votes at the ballot.

On the same day, the citizenry rejected another governmental proposal. The referendum on the Federal Act on Electronic Identification Services failed clearly with 64.4 per cent no-votes. Opponents of the new act were concerned about data protection and were unwilling to accept a solution that could provoke abuses by private issuers (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe and Rey2021a: 5).

On 13 June, voters decided on five ballot proposals that covered a wide range of topics from agriculture, Covid-19 governance, the revised CO2 Act and measures for fighting terrorism (Table 2). This resulted in an exceptionally high voting turnout of almost 60 per cent. What is striking in comparison with other voting dates is that a particularly large number of young people cast their vote, namely 54 per cent of all 18–29-year-olds (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe, Estermann and Bohn2021b: 7). While the two agricultural initiatives mobilized the most, the CO2 Act was most intensively discussed in the campaign.

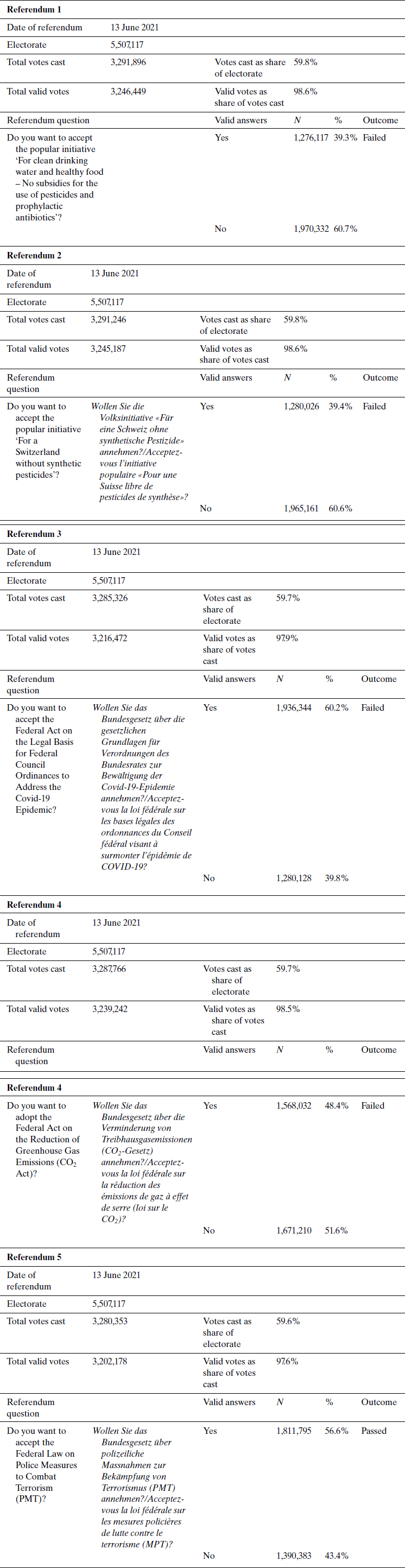

Table 2. Results of five referenda held on 13 June 2021 in Switzerland

Source: The Federal Chancellery (2021).

The first two ballot votes on that day were the popular initiative ‘for clean drinking water and healthy food’ and the popular initiative ‘for a Switzerland without artificial pesticides’. The initiatives wanted to introduce strong environmental requirements via direct payments to agriculture and a ban of pesticides. From the beginning, the public debates on both proposals were conducted together, which is why the ‘no’ side argued very similarly against both initiatives. Accordingly, also the ballot results were almost identical, with 39.3 per cent voting in favour of the clean drinking water and 39.4 per cent voting in favour for the initiative against pesticides. Furthermore, the pattern of conflict between the two proposals was almost identical. Even though a ban on (artificial) pesticides in agriculture was well accepted, higher expected food prices in Switzerland was a main argument in the counter-campaign (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe, Estermann and Bohn2021b: 5f.). Eventually, a majority judged the demands as too extreme or found the proposals exaggerated. In the countryside, the rejection was more pronounced, while in the core cities it convinced a majority (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe, Estermann and Bohn2021b: 5).

The third proposal of the day was a referendum on the COVID-19 act in Switzerland. This act was enacted to create a legal basis for the Federal Council to mitigate the negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic on society and the economy. The association ‘Friends of the Constitution’ had launched a referendum on the grounds that this law would create a potential for abuse and that it had been drafted without the consent of the people. At the ballot, the COVID-19 Act was clearly accepted with 60.2 per cent of votes in favour. ‘Yes’ voters were characterized by their confidence in the Federal Council, the federal office of health and the Covid-19 task force as well as their support the policy during the global pandemic (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe, Estermann and Bohn2021b: 6).

The fourth proposal was the referendum on the Federal Act on the Reduction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions (CO2 Act). The CO2 Act built on previous Swiss climate policy and aimed at creating financial incentives to promote climate-friendly behaviour. Among the major parties, only the right-wing SVP/UDC was against the Act, but interestingly, the French-speaking Switzerland section of the climate strike movement joined the camp of opponents. While the SVP/UDC criticized that the law would be too expensive, the climate strike movement argued that it did not go far enough. In the end, the law was narrowly rejected at the ballot with only 48.4 per cent of votes in favour (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe, Estermann and Bohn2021b: 6). While environmental proposals such as the CO2 Act are generally not easy to get accepted in direct democracy (Stadelmann-Steffen Reference Stadelmann-Steffen2011), the strong mobilization of the agricultural initiatives in rural regions not only led to two clear ‘no’ votes on these initiatives, but eventually also contributed to the rejection of the CO2 Act (Golder Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe, Estermann and Bohn2021b: 5).

The fifth proposal on this well-filled voting day was the referendum on the federal act on police measures to combat terrorism. The aim of the Act was to give the police more instruments to prevent terrorist attacks. For opponents, the law was not clearly formulated and they feared that Switzerland would become a police state. Nevertheless, the referendum was rejected with 56.6 per cent of voters supporting the Act (Golder Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Salathe, Estermann and Bohn2021b: 7).

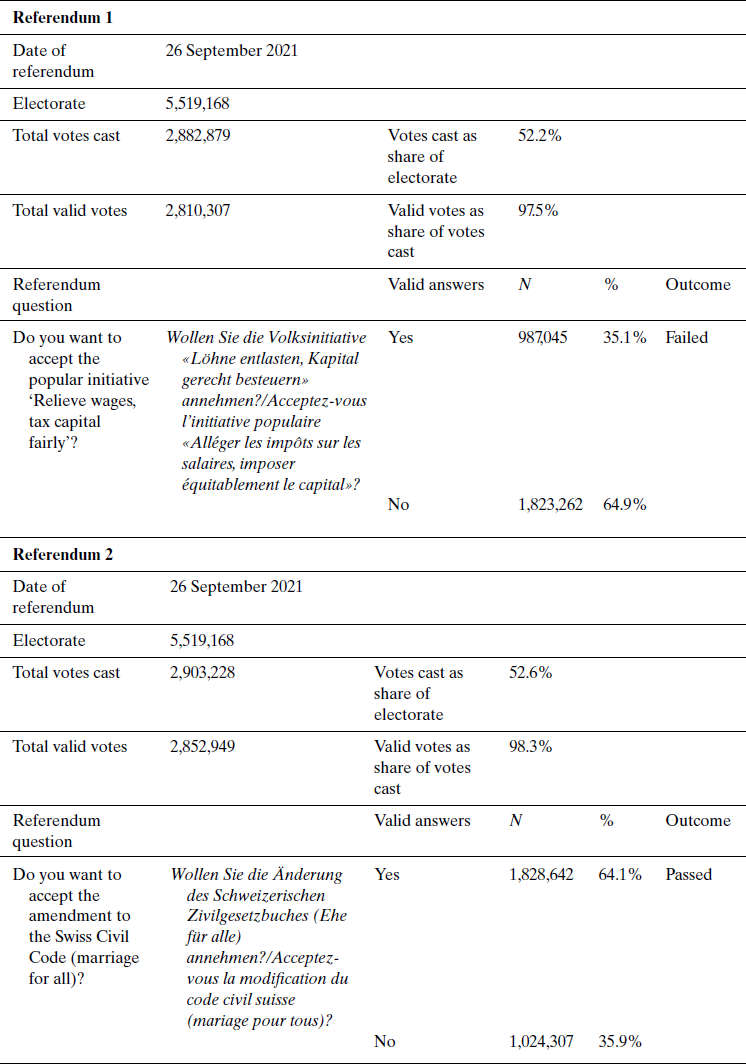

On 26 September, the Swiss population voted on two proposals (Table 3). The first proposal was the popular initiative ‘Reduce tax on salaries, tax capital fairly’, which was initiated by the Young Socialists (JUSO/JS) and wanted capital income such as interest or dividends to be taxed more heavily. The initiative was rejected clearly with only 35.1 per cent yes-votes.

Table 3. Results of two referenda held on 26 September 2021 in Switzerland

Source: The Federal Chancellery (2021).

The second vote was the referendum on the marriage for all. The referendum was against the extension of marriage to same-sex couples. However, at the ballot, as the 30th country worldwide – and one of the last in Western Europe – Switzerland accepted the marriage for all reform with 64.1 per cent of voters and all cantons supporting it.Footnote 2 The bill enjoyed support among large parts of the population and was practically only rejected by people who described themselves as right-wing extremists, sympathized with the SVP/UDC or had a strong belief in the free churches (Golder Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Schoch and Rey2021c: 4).

On this day, an above-average number of voters took part in the ballot, with a participation rate around 52.4 per cent, whereas marriage for all mobilized more voters than capital taxation (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Schoch and Rey2021c: 5).

On the last voting date, on 28 November, Switzerland decided about three proposals, of which two outcomes were strongly influenced by the pandemic (Table 4). Additionally, this exceptional situation pushed the overall voter turnout to a new record high: since the introduction of women's suffrage in 1971, the average turnout has never been higher than in 2021 (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Seebacher, Jenzer and Rey2021d: 4). The first proposal was the ‘nursing initiative’, which calls on the federal government and the cantons to do more for the nursing profession, for example, in the area of training, and also to regulate working conditions and wages. Although the issue had been on the political agenda for years, the pandemic gave special visibility and relevance to the concerns of the initiative and, thus, served as a crucial success factor. The proposal was approved by 61 per cent of voters. According to a follow-up survey (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Seebacher, Jenzer and Rey2021d), the ballot result was also an expression of trust in the trade unions and in the nursing staff, and further related to values for a strong welfare state and for solidarity.

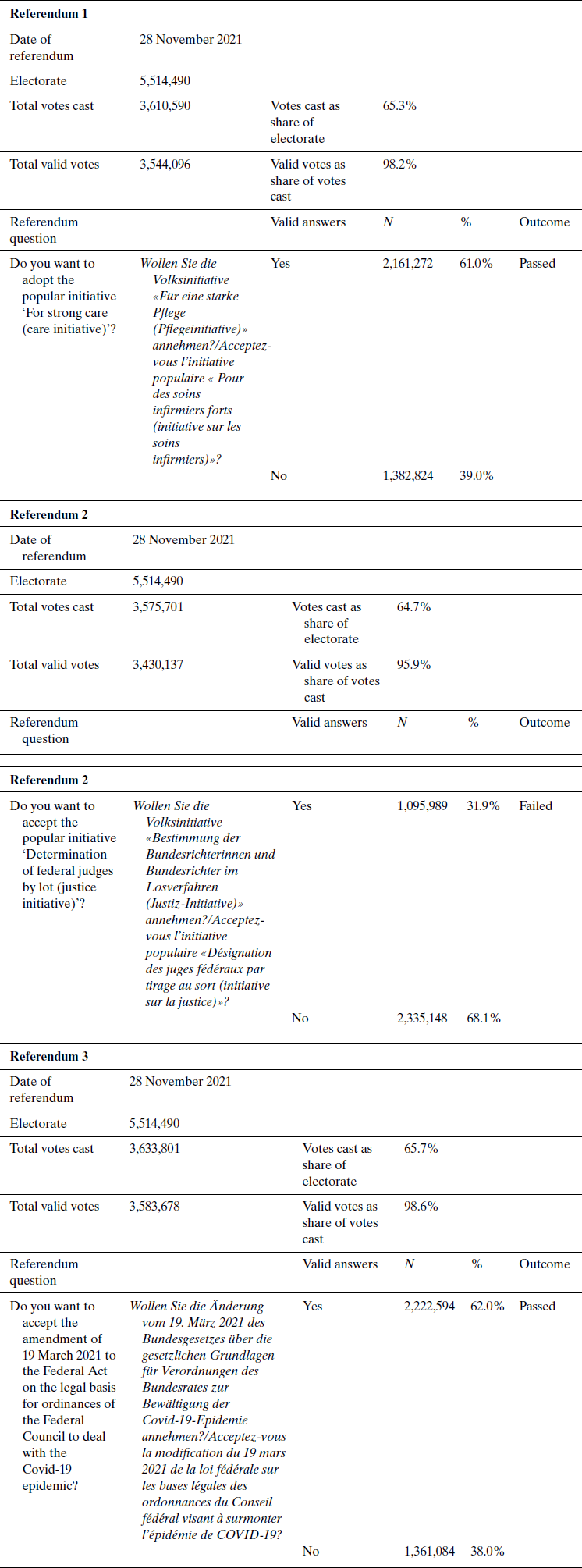

Table 4. Results of three referenda held on 28 November 2021 in Switzerland

Source: The Federal Chancellery (2021).

The second proposal was the ‘judge initiative’. The initiative proposed a new election process for federal judges who would be drawn by lot from a group of candidates chosen by a committee of experts. The proposal was clearly rejected with 32 per cent of yes-votes. The results reflect a general pattern in Swiss politics whereby Swiss citizens exhibit strong trust in the existing institutions and are reluctant to change them at the ballot box.

The third vote was the referendum on the COVID-19 Act. For the second time in the year, and only three months after the first vote, the population could again express their opinion on the pandemic governance in Switzerland. The referendum mainly focused on the Covid-19 certificate (i.e., the proof that a person has either been vaccinated against Covid-19, received a negative test result or recovered from Covid-19). Once again, the population backed the coronavirus policy of the Federal Council and Parliament and accepted the law with an approval rate that was even higher than in June, rising from 60 per cent to 62 per cent (Golder Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Seebacher, Jenzer and Rey2021d: 5).

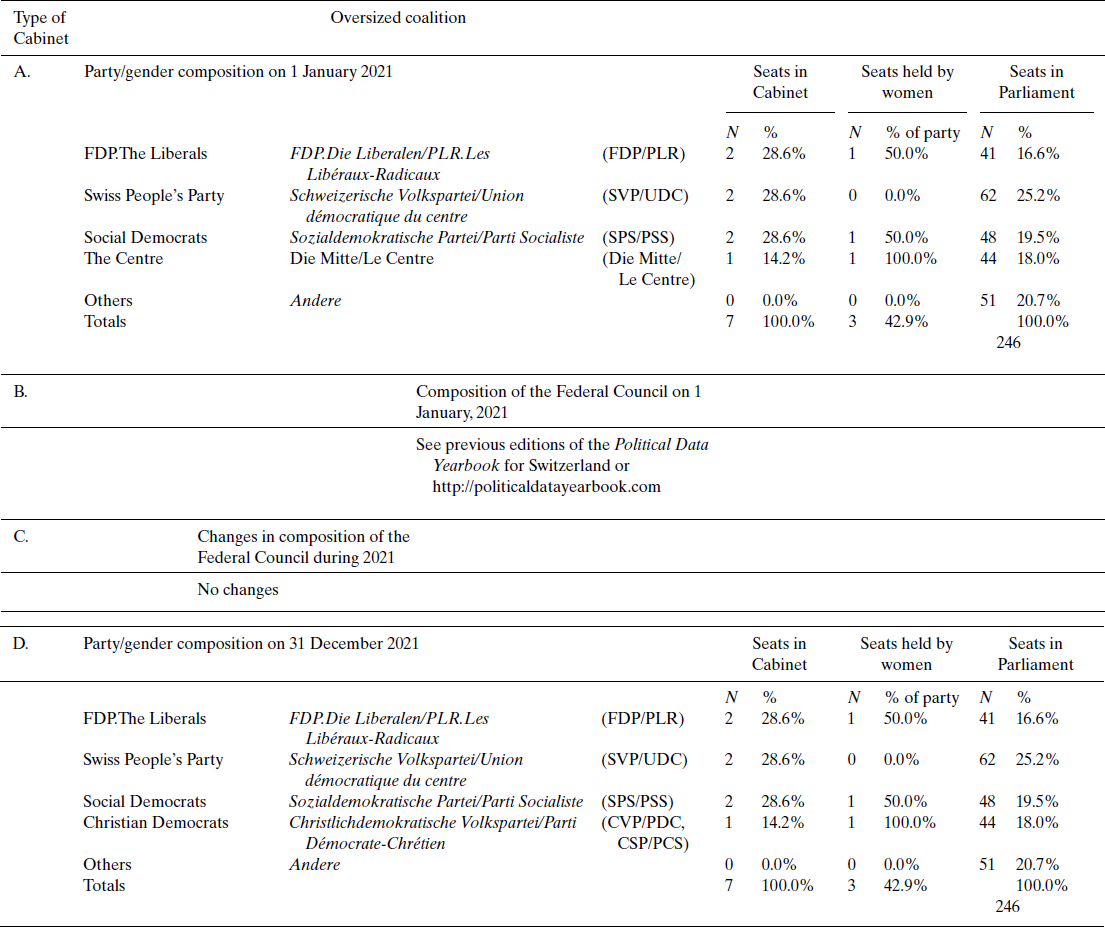

Cabinet report

On 9 December 2020, Parliament elected the federal President and Vice-President for 2021, as these positions rotate annually among the seven members of the Cabinet. For the first time in his career, Guy Parmelin (SVP/UDC) was elected as federal President with 188 out of 202 valid votes. Ignazio Cassis (FDP/PLR) was nominated as Vice-President and received 162 out of 191 valid votes. Data on the cabinet composition of federal council can be found in Table 5.

Table 5. Cabinet composition of the Federal Council in Switzerland in 2021

Notes: Parliament refers to the Vereinigte Bundesversammlung and consists of the seats in both chambers (the upper and lower houses), which means a total of 246 seats.

The Cabinet is an oversized coalition, but not every faction that has seats in Parliament has a federal councillor (see ‘Others’ in the Cabinet composition).

The president and vice-president of the confederation change every year. But the composition of the Cabinet regarding the ministers and their department stayed the same. In 2021, the President was Guy Parmelin (SVP/UDC) and the Vice-President was Ignazio Cassis (FDP/PLR).

Source: The Federal Council (2021).

Parliament report

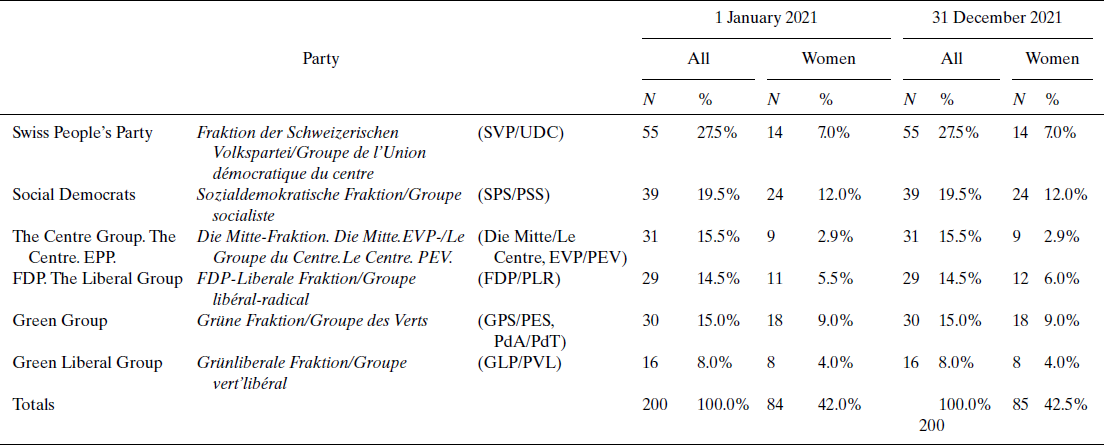

In this second year of the legislative term, four members of the lower house of Parliament (National Council) were replaced. Two persons left the national Parliament because they were elected to the governments of their home cantons. The other two members resigned for personal reasons. Data on the party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat/Conseil national) can be found in Table 6.

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat/Conseil national) in Switzerland in 2021

Note: Parliamentary groups are not identical to political parties. For more information, see https://www.parlament.ch/en/organe/groups.

Source: The Federal Assembly–The Swiss Parliament (2022).

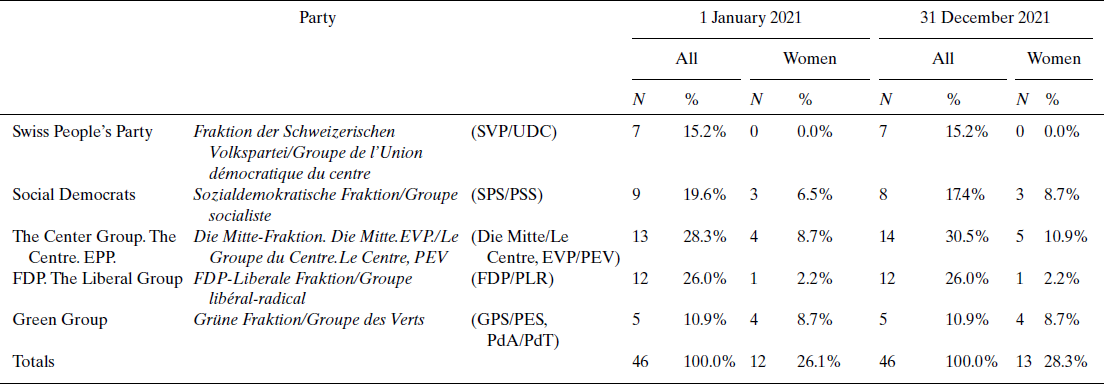

Furthermore, one member of the upper house (Council of States) stepped down. This change received more public attention, not only because it concerned the former and long-time president of the SPS/PSS, Christian Levrat, but also because in the by-elections, he was replaced by the candidate of ‘The Center’, Isabelle Chassot, meaning that the SPS/PSS lost one seat in the Council of States. Data on the party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Ständerat/Conseil des États) can be found in Table 7.

Table 7. Party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Ständerat/Conseil des États) in Switzerland in 2021

Note: Parliamentary groups are not identical to political parties. For more information, see https://www.parlament.ch/en/organe/groups.

Source: The Federal Assembly-The Swiss Parliament (2022).

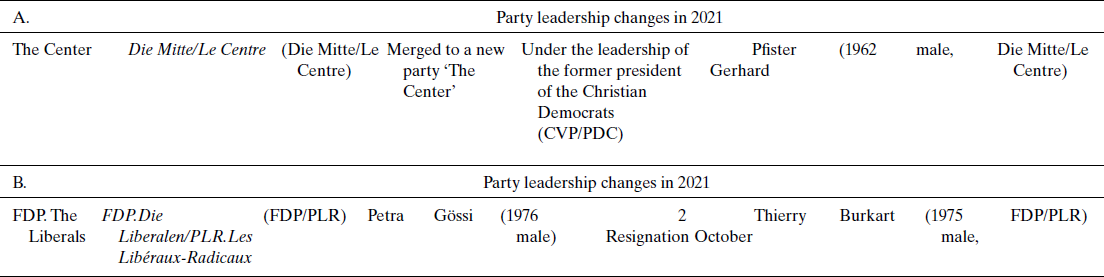

Political party report

Already in November 2020, the former Christian Democratic People's Party (CVP/PDC) and the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP/PBD) had decided to merge into a new joint party called ‘The Centre’. The new party officially started its activities on 1 January 2021. Gerhard Pfister, who has been the president of the CVP/PDC before the merger, was elected as new and first president of ‘The Center’.

In the FDP/PLR, there was a change in the party leadership. After five years as president of the FDP/PLR, Petra Gössi resigned from office. On 2 October, the delegates of the party elected Thierry Burkhart as her successor. One of the clearest differences between the former president and her successor is in the area of climate policy, as Burkart was a vocal critic of the green course taken by the previous president. Data on the changes in political parties can be found in Table 8.

Table 8. Changes in political parties in Switzerland in 2021

Note: During 2020, the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP/PBD) formed together with the former Christian The Democratic Faction (CVP/PDC, CSP/PCS and EVP/PEV), the new ‘The Center Group. CVP-EVP-BDP’. Officially the new (and old) president of the new Centre party was elected in 2021.

Source: The Federal Chancellery (2021).

Institutional change report

There were no major institutional changes in 2021.

Issues in national politics

In normal times, Switzerland belongs to one of the most decentralized countries in the world, with the cantons enjoying substantial autonomy in many areas. However, during the pandemic, the Federal Law of Epidemics, and more specifically the declaration of ‘extraordinary’ or ‘special situation’, leads to rather strong centralization of responsibility and power towards the Federal Council (Hegele & Schnabel Reference Hegele and Schnabel2020). The strongest form of this centralization, that is, the ‘extraordinary situation’, was already abandoned in 2020 and replaced by the more moderate ‘special situation’ remaining in place throughout 2021. However, while even the latter still means that the Federal Council can order specific measures that in normal times are in the competence of the cantons, the changed and unusual balance of power triggered intense debates – in society and also in Parliament – about the merits and disadvantages of Swiss federalism, especially during crises.

Moreover, social movements against pandemic measures, especially also against vaccination, found fertile ground in Switzerland. They were accompanied by a strong social polarization with regard to various pandemic-related aspects (Craviolini et al. Reference Craviolini, Hermann, Krähenbühl and Wenger2021), which also extended to more general questions of political authority and democratic legitimacy. This situation resulted not only in numerous protests and one of the lowest vaccination rates in Europe, but also in the two referendum votes as well as ‘anti-corona’ groups running in local and cantonal elections.

Finally, in May 2021, the Federal Council decided to terminate the negotiations with the EU on the EU–Swiss Institutional Framework Agreement. This decision has the potential to significantly shape political debates and election campaigns in the near future.

Acknowledgement

Open Access Funding provided by Universitat Bern.