Highlights

What is already known?

-

• The I-squared index is widely used in relation to the identification or description of heterogeneity in meta-analysis.

-

• The role of I-squared has been questioned, partly because it is often misinterpreted: It measures inconsistency in findings, which is not the same as variability in effect sizes.

What is new?

-

• We provide a technical overview and our reflections on the I-squared index, including its definition, computation, and interpretation, and we offer a new definition that might be particularly useful when designing simulation studies.

Potential impact for RSM readers

-

• Given the routine use of the I-squared index in diverse research fields, it is important that users have a proper understanding of what it can, and cannot, portray.

1 Introduction

Meta-analysis is the statistical integration of results from a set of studies considered to be sufficiently similar for the combined estimate to be meaningful. If the studies are very similar such that they can be assumed to have addressed the same research question, their results might be expected to differ only because of sampling error. If the studies are all very large, the variation among their results would then be small. However, in practice, studies tend to differ in aspects such as the sample characteristics, ways in which treatments or exposures are defined or measured, and ways in which outcomes are measured. As a result, some degree of additional variation among the results is to be expected.Reference Higgins1, Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2 Such variation beyond what can be attributed to chance alone is usually called statistical heterogeneity or (in statistical texts) simply heterogeneity. It may be measured using, for example, the standard deviation of true effects across studies on the scale in which the effect size is measured (e.g., as a mean, a mean difference, or (log) odds ratio).

The

![]() ${I}^2$

index is a descriptive statistic that is used in relation to heterogeneity among studies in a meta-analysis. It aims to quantify inconsistency, a term we use for a construct that is distinct from (statistical) heterogeneity. Inconsistency relates to the extent to which the statistical findings of the studies disagree with each other after taking into account sampling error. Interpretation of inconsistency measures such as the

${I}^2$

index is a descriptive statistic that is used in relation to heterogeneity among studies in a meta-analysis. It aims to quantify inconsistency, a term we use for a construct that is distinct from (statistical) heterogeneity. Inconsistency relates to the extent to which the statistical findings of the studies disagree with each other after taking into account sampling error. Interpretation of inconsistency measures such as the

![]() ${I}^2$

index does not depend on the scale on which the result is measured. As such, they cannot be used to infer the actual (or absolute) amount of heterogeneity in the effect sizes across studies. The

${I}^2$

index does not depend on the scale on which the result is measured. As such, they cannot be used to infer the actual (or absolute) amount of heterogeneity in the effect sizes across studies. The

![]() ${I}^2$

index is typically expressed as a percentage, with a value of 0% indicating that the only source of variability among the results reported in the primary studies is sampling error (so there is no heterogeneity) and values approaching 100% indicating that nearly all variability is due to heterogeneity among the studies rather than sampling error.

${I}^2$

index is typically expressed as a percentage, with a value of 0% indicating that the only source of variability among the results reported in the primary studies is sampling error (so there is no heterogeneity) and values approaching 100% indicating that nearly all variability is due to heterogeneity among the studies rather than sampling error.

The index was introduced under the nomenclature

![]() ${I}^2$

by Higgins and Thompson (HT) in 2002, motivated by a desire to find an alternative to either the standard

${I}^2$

by Higgins and Thompson (HT) in 2002, motivated by a desire to find an alternative to either the standard

![]() ${\chi}^2$

test for heterogeneity (whose interpretation depends importantly on the number of studies) or the between-study variance as estimated in a random-effects meta-analysis (whose interpretation depends importantly on the measurement scale). The

${\chi}^2$

test for heterogeneity (whose interpretation depends importantly on the number of studies) or the between-study variance as estimated in a random-effects meta-analysis (whose interpretation depends importantly on the measurement scale). The

![]() ${I}^2$

index was promoted in a BMJ paper by the same authors, along with Altman and Deeks, the following year.Reference Higgins and Thompson3,

Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman4 The notion of “proportion of total variance due to between-study variance” had previously been mentioned in passing by Takkouche and colleagues.Reference Takkouche, CadarsoSurez and Spiegelman5 Reporting of the

${I}^2$

index was promoted in a BMJ paper by the same authors, along with Altman and Deeks, the following year.Reference Higgins and Thompson3,

Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman4 The notion of “proportion of total variance due to between-study variance” had previously been mentioned in passing by Takkouche and colleagues.Reference Takkouche, CadarsoSurez and Spiegelman5 Reporting of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index in meta-analyses has increased year by year, extending far beyond the initial context for which it was initially proposed, and the measure has been widely implemented in different research fields.Reference Hansen, Zeng and Ryan6–

Reference Villanueva and Zavarsek10 The index is now extremely widely used; the 2002 and 2003 papers frequently appear in lists of very highly cited papers.Reference Uthman, Okwundu, Wiysonge, Young and Clarke11,

Reference Nietert, Wahlquist and Herbert12 The journal Nature recently ranked the BMJ paper as the twentieth most cited of the twenty-first century.Reference Pearson, Ledford, Hutson and Van Noorden13

${I}^2$

index in meta-analyses has increased year by year, extending far beyond the initial context for which it was initially proposed, and the measure has been widely implemented in different research fields.Reference Hansen, Zeng and Ryan6–

Reference Villanueva and Zavarsek10 The index is now extremely widely used; the 2002 and 2003 papers frequently appear in lists of very highly cited papers.Reference Uthman, Okwundu, Wiysonge, Young and Clarke11,

Reference Nietert, Wahlquist and Herbert12 The journal Nature recently ranked the BMJ paper as the twentieth most cited of the twenty-first century.Reference Pearson, Ledford, Hutson and Van Noorden13

Although

![]() ${I}^2$

has been welcomed by some,Reference Ioannidis14,

Reference Pathak, Dwivedi, Deo, Sreenivas and Thakur15 its popularity has been accompanied by some common misconceptions and misinterpretations that hamper its usefulness in practice.Reference Borenstein, Higgins, T Hedges and Rothstein16,

Reference Rücker, Schwarzer, Carpenter and Schumacher17 When interpreted correctly as a measure of inconsistency rather than heterogeneity, the index has a useful place in the meta-analysis toolkit and its idea has been extended to other applications. In this paper, we provide a technical discussion of the

${I}^2$

has been welcomed by some,Reference Ioannidis14,

Reference Pathak, Dwivedi, Deo, Sreenivas and Thakur15 its popularity has been accompanied by some common misconceptions and misinterpretations that hamper its usefulness in practice.Reference Borenstein, Higgins, T Hedges and Rothstein16,

Reference Rücker, Schwarzer, Carpenter and Schumacher17 When interpreted correctly as a measure of inconsistency rather than heterogeneity, the index has a useful place in the meta-analysis toolkit and its idea has been extended to other applications. In this paper, we provide a technical discussion of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index, providing extensive references to related papers and our reflections from several years experience of working in the research synthesis field. We present different definitions of the

${I}^2$

index, providing extensive references to related papers and our reflections from several years experience of working in the research synthesis field. We present different definitions of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index, clarify its interpretation, address expressions of uncertainty, discuss extensions, and close with our suggestions on how the use and reporting of

${I}^2$

index, clarify its interpretation, address expressions of uncertainty, discuss extensions, and close with our suggestions on how the use and reporting of

![]() ${I}^2$

might be improved in future meta-analyses.

${I}^2$

might be improved in future meta-analyses.

2 Definitions of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

2.1 Standard (Q-based) definition of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

Perhaps the most familiar definition of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index is based on the

${I}^2$

index is based on the

![]() $Q$

statistic, which is another commonly employed statistic used to examine the variability among the results included in the meta-analysis. In this approach,

$Q$

statistic, which is another commonly employed statistic used to examine the variability among the results included in the meta-analysis. In this approach,

![]() ${I}^2$

is defined as

${I}^2$

is defined as

where

![]() $k$

is the number of studies and

$k$

is the number of studies and

![]() $Q$

is the

$Q$

is the

![]() ${\chi}^2$

statistic proposed by Cochran and defined as followsReference Cochran18:

${\chi}^2$

statistic proposed by Cochran and defined as followsReference Cochran18:

Here,

![]() ${y}_i$

is the result from the

${y}_i$

is the result from the

![]() $i$

th

study;

$i$

th

study;

![]() ${w}_i=1/{\sigma}_i^2$

is the weight assigned to the result from the

${w}_i=1/{\sigma}_i^2$

is the weight assigned to the result from the

![]() $i$

th

study, with

$i$

th

study, with

![]() ${\sigma}_i^2$

being the within-study variance reflecting the sampling error in

${\sigma}_i^2$

being the within-study variance reflecting the sampling error in

![]() ${y}_i$

and typically assumed to be known in meta-analysis; and

${y}_i$

and typically assumed to be known in meta-analysis; and

![]() ${\overline{y}}_w={\sum {w}_i{y}_i} / {\sum {w}_i}$

is an inverse-variance-weighted average of the study-specific estimates. Under the simplifying assumption that weights are known and identical for every study, the

${\overline{y}}_w={\sum {w}_i{y}_i} / {\sum {w}_i}$

is an inverse-variance-weighted average of the study-specific estimates. Under the simplifying assumption that weights are known and identical for every study, the

![]() $Q$

statistic follows a chi-squared distribution with

$Q$

statistic follows a chi-squared distribution with

![]() $k-1$

degrees of freedom.Reference Hoaglin19 Although the

$k-1$

degrees of freedom.Reference Hoaglin19 Although the

![]() $Q$

statistic has been widely used as a hypothesis test to detect heterogeneity among the individual results, it suffers from low statistical power in most meta-analytic applications and therefore can easily lead to misleading conclusions.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2,

Reference Borenstein20

$Q$

statistic has been widely used as a hypothesis test to detect heterogeneity among the individual results, it suffers from low statistical power in most meta-analytic applications and therefore can easily lead to misleading conclusions.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2,

Reference Borenstein20

Because the value of

![]() $Q$

can be smaller than its degrees of freedom, the

$Q$

can be smaller than its degrees of freedom, the

![]() ${I}^2$

index defined in (1) can be negative. Therefore, in practice,

${I}^2$

index defined in (1) can be negative. Therefore, in practice,

![]() ${I}^2$

is customarily truncated at 0%, such that negative numbers (indicating less variation than would be expected by chance alone) are not allowed.

${I}^2$

is customarily truncated at 0%, such that negative numbers (indicating less variation than would be expected by chance alone) are not allowed.

2.2 Conceptual definition of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

A broader definition of

![]() ${I}^2$

relates to the underlying parameters rather than to the test statistic

${I}^2$

relates to the underlying parameters rather than to the test statistic

![]() $Q$

. Although the following definition appears to be parametric on the surface, it is not strictly parametric, as we shall discuss. We define a quantity

$Q$

. Although the following definition appears to be parametric on the surface, it is not strictly parametric, as we shall discuss. We define a quantity

![]() ${\iota}^2$

as

${\iota}^2$

as

where

![]() ${\tau}^2$

is the between-study variance parameter and

${\tau}^2$

is the between-study variance parameter and

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

is a measure of within-study variance (i.e., the sampling error in estimation of

${\sigma}^2$

is a measure of within-study variance (i.e., the sampling error in estimation of

![]() ${y}_i$

). We use a Greek letter here to distinguish the parametric form,

${y}_i$

). We use a Greek letter here to distinguish the parametric form,

![]() ${\iota}^2$

, from a statistic computed from data, for which we use

${\iota}^2$

, from a statistic computed from data, for which we use

![]() ${I}^2$

.

${I}^2$

.

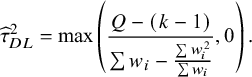

Numerous estimators of between-study variance,

![]() ${\tau}^2$

, have been described in the meta-analytic literature.Reference Veroniki, Jackson and Viechtbauer21 A moment-based estimate,

${\tau}^2$

, have been described in the meta-analytic literature.Reference Veroniki, Jackson and Viechtbauer21 A moment-based estimate,

![]() ${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

, introduced by DerSimonian and Laird, was popular for many years, although others are now considered preferable.Reference Langan, Higgins and Simmonds22,

Reference Langan, Higgins and Jackson23 The moment-based estimate is given byReference DerSimonian and Laird24

${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

, introduced by DerSimonian and Laird, was popular for many years, although others are now considered preferable.Reference Langan, Higgins and Simmonds22,

Reference Langan, Higgins and Jackson23 The moment-based estimate is given byReference DerSimonian and Laird24

$$\begin{align*}{\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2=\max \left(\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{\sum {w}_i-\frac{\sum {w}_i^2}{\sum {w}_i}},0\right).\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2=\max \left(\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{\sum {w}_i-\frac{\sum {w}_i^2}{\sum {w}_i}},0\right).\end{align*}$$

The within-study variance quantity

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

is a clearly defined parameter only if all studies have the same within-study variance. Otherwise,

${\sigma}^2$

is a clearly defined parameter only if all studies have the same within-study variance. Otherwise,

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

needs to be interpreted as a “typical” within-study variance across the studies included in the meta-analysis. Different choices are available for estimating such a typical variance, including the arithmetic mean, the median, and the geometric mean of the

${\sigma}^2$

needs to be interpreted as a “typical” within-study variance across the studies included in the meta-analysis. Different choices are available for estimating such a typical variance, including the arithmetic mean, the median, and the geometric mean of the

![]() ${\sigma}_i^2$

. HT proposed the quantity:

${\sigma}_i^2$

. HT proposed the quantity:

$$\begin{align}{\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2=\frac{\left(k-1\right)\sum {w}_i}{{\left(\sum {w}_i\right)}^2-\sum {w}_i^2}\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2=\frac{\left(k-1\right)\sum {w}_i}{{\left(\sum {w}_i\right)}^2-\sum {w}_i^2}\end{align}$$

with

![]() ${w}_i=1/{\sigma}_i^2$

.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 Takkouche, Cadarso-Suárez, and Spiegelman (TCS) usedReference Takkouche, CadarsoSurez and Spiegelman5

${w}_i=1/{\sigma}_i^2$

.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 Takkouche, Cadarso-Suárez, and Spiegelman (TCS) usedReference Takkouche, CadarsoSurez and Spiegelman5

Since

![]() $Var\left({\overline{y}}_w\right)=1/\sum {w}_i$

and

$Var\left({\overline{y}}_w\right)=1/\sum {w}_i$

and

![]() ${w}_i=1/{\sigma}_i^2$

, it can be seen that

${w}_i=1/{\sigma}_i^2$

, it can be seen that

![]() ${\widehat{\sigma}}_{TCS}^2$

is the harmonic mean of the

${\widehat{\sigma}}_{TCS}^2$

is the harmonic mean of the

![]() ${\sigma}_i^2$

values.

${\sigma}_i^2$

values.

Given that there are several options to estimate the between-study variance

![]() ${\tau}^2$

and several options to estimate a typical within-study variance

${\tau}^2$

and several options to estimate a typical within-study variance

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

, numerous values of

${\sigma}^2$

, numerous values of

![]() ${I}^2$

can be derived using Equation (3). The

${I}^2$

can be derived using Equation (3). The

![]() $Q$

-based definition of

$Q$

-based definition of

![]() ${I}^2$

in Equation (1) corresponds to the choice of the DerSimonian and Laird estimator,

${I}^2$

in Equation (1) corresponds to the choice of the DerSimonian and Laird estimator,

![]() ${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

, and the use of

${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

, and the use of

![]() ${\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2$

from Equation (4). We refer to this as the “method-of-moments” (MM) definition:

${\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2$

from Equation (4). We refer to this as the “method-of-moments” (MM) definition:

$$\begin{align}{I}_{MM}^2=\frac{{\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2}{{\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2+{\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2}=\frac{\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{\sum {w}_i-\frac{\sum {w}_i^2}{\sum {w}_i}}}{\left(\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{\sum {w}_i-\frac{\sum {w}_i^2}{\sum {w}_i}}\right)+\left(\frac{\left(k-1\right)\sum {w}_i}{{\left(\sum {w}_i\right)}^2-\sum {w}_i^2}\right)}=\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{Q}.\kern0.6em\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{I}_{MM}^2=\frac{{\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2}{{\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2+{\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2}=\frac{\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{\sum {w}_i-\frac{\sum {w}_i^2}{\sum {w}_i}}}{\left(\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{\sum {w}_i-\frac{\sum {w}_i^2}{\sum {w}_i}}\right)+\left(\frac{\left(k-1\right)\sum {w}_i}{{\left(\sum {w}_i\right)}^2-\sum {w}_i^2}\right)}=\frac{Q-\left(k-1\right)}{Q}.\kern0.6em\end{align}$$

2.3 Heuristic definition of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

Noting the broad interpretation of

![]() ${I}^2$

as the proportion of total variation in observed results that arises from between-study heterogeneity,Reference Higgins and Thompson3,

Reference von Hippel25 a further option to define

${I}^2$

as the proportion of total variation in observed results that arises from between-study heterogeneity,Reference Higgins and Thompson3,

Reference von Hippel25 a further option to define

![]() ${I}^2$

is as follows:

${I}^2$

is as follows:

$$\begin{align}{I}^2=\frac{{\widehat{\tau}}^2}{Var\left({y}_i\right)}\times 100\%.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{I}^2=\frac{{\widehat{\tau}}^2}{Var\left({y}_i\right)}\times 100\%.\end{align}$$

The denominator in (7) is just the sample variance of the study estimates. Under the usual additive heterogeneity model, rather than a multiplicative heterogeneity model,Reference Mawdsley, Higgins, Sutton and Abrams26 this can be regarded as conceptually equivalent to the sum of the between-study (

![]() ${\tau}^2$

) and within-study (

${\tau}^2$

) and within-study (

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

) variance components in the denominator of Equation (3).Reference von Hippel25

${\sigma}^2$

) variance components in the denominator of Equation (3).Reference von Hippel25

2.4 General definition of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

The conceptual definition presented in Equation (3) is analogous to using weighted sums of squares as follows:

In this expression,

![]() $WS{S}_b=\sum {w}_i{\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2$

is the between-study weighted sum of squares and quantifies the dispersion of the effect parameters from each study (

$WS{S}_b=\sum {w}_i{\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2$

is the between-study weighted sum of squares and quantifies the dispersion of the effect parameters from each study (

![]() ${\theta}_i$

) from the overall mean

${\theta}_i$

) from the overall mean

![]() $\mu$

. The term

$\mu$

. The term

![]() $WS{S}_w=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)}^2$

is the within-study weighted sum of squares, which accounts for the dispersion of the estimates (

$WS{S}_w=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)}^2$

is the within-study weighted sum of squares, which accounts for the dispersion of the estimates (

![]() ${y}_i$

) from the effect parameters

${y}_i$

) from the effect parameters

![]() ${\theta}_i$

for each study.

${\theta}_i$

for each study.

We can verify the conceptual equivalence of (8) with (3) and (7) by noting that

$$\begin{align}WS{S}_{\mathrm{total}}&=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-\mu \right)}^2 \nonumber\\&=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i+{\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2 \nonumber\\&=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)}^2+\sum {w}_i{\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2+2\sum {w}_i\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}WS{S}_{\mathrm{total}}&=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-\mu \right)}^2 \nonumber\\&=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i+{\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2 \nonumber\\&=\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)}^2+\sum {w}_i{\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2+2\sum {w}_i\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right),\end{align}$$

where

![]() $\sum {w}_i{\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2$

corresponds to

$\sum {w}_i{\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)}^2$

corresponds to

![]() $WS{S}_b$

and

$WS{S}_b$

and

![]() $\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)}^2$

corresponds to

$\sum {w}_i{\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)}^2$

corresponds to

![]() $WS{S}_w$

. The final term,

$WS{S}_w$

. The final term,

![]() $2\sum {w}_i\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)$

, represents residual covariation between the within- and between-study variance components. When within-study variances are uncorrelated with effect sizes, this covariation will be zero and the

$2\sum {w}_i\left({y}_i-{\theta}_i\right)\left({\theta}_i-\mu \right)$

, represents residual covariation between the within- and between-study variance components. When within-study variances are uncorrelated with effect sizes, this covariation will be zero and the

![]() $WS{S}_{\mathrm{total}}$

is equivalent to the sum of

$WS{S}_{\mathrm{total}}$

is equivalent to the sum of

![]() $WS{S}_b$

and

$WS{S}_b$

and

![]() $WS{S}_w$

.

$WS{S}_w$

.

The general definition of

![]() ${I}^2$

presented in Equation (8) provides a framework to specify the “true” value of the index (

${I}^2$

presented in Equation (8) provides a framework to specify the “true” value of the index (

![]() ${\iota}^2$

) in simulation studies. We used this definition for the study presented in the next section.

${\iota}^2$

) in simulation studies. We used this definition for the study presented in the next section.

3 Illustration of the properties of different

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

estimators

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

estimators

3.1 Application to two real data sets

Simulation studies indicate that alternatives to

![]() ${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

have better properties,Reference Langan, Higgins and Simmonds22,

Reference Langan, Higgins and Jackson23 so the question arises as to whether using an alternative estimator for

${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

have better properties,Reference Langan, Higgins and Simmonds22,

Reference Langan, Higgins and Jackson23 so the question arises as to whether using an alternative estimator for

![]() ${\tau}^2$

in (3) would be preferable for computing

${\tau}^2$

in (3) would be preferable for computing

![]() ${I}^2$

. In addition, since different options are available for estimating

${I}^2$

. In addition, since different options are available for estimating

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

, it is not immediately clear which should be used. In a later section, we examine some of these issues in a simulation study. Here, we illustrate the impact that different choices can have through application to two examples, using the metafor R package for the calculations.Reference Viechtbauer27

${\sigma}^2$

, it is not immediately clear which should be used. In a later section, we examine some of these issues in a simulation study. Here, we illustrate the impact that different choices can have through application to two examples, using the metafor R package for the calculations.Reference Viechtbauer27

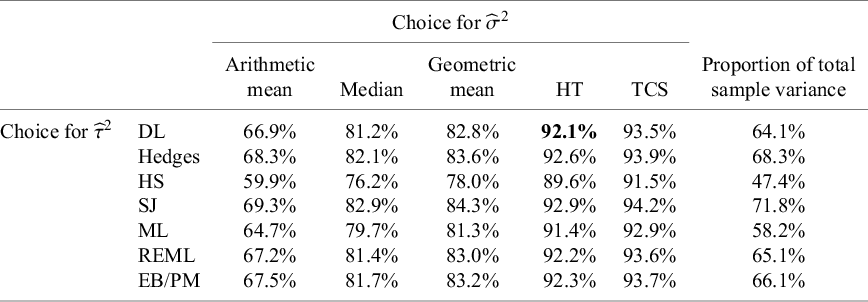

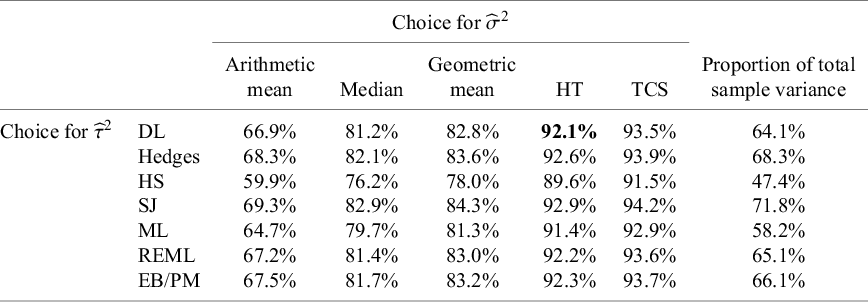

The first example is a set of 13 clinical trials of Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) vaccine to prevent tuberculosis,Reference Colditz, Brewer and Berkey28 using data presented by Berkey and colleagues.Reference Berkey, Hoaglin, Mosteller and Colditz29 The effect measure for this example is the log risk ratio comparing the risk of tuberculosis in the vaccinated versus unvaccinated groups. In Table 1, we list different values of

![]() ${I}^2$

for different estimators of

${I}^2$

for different estimators of

![]() ${\tau}^2$

and

${\tau}^2$

and

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

as well as using the simple sample variance of the

${\sigma}^2$

as well as using the simple sample variance of the

![]() ${y}_i$

as the denominator (Equation (7)). A key point we seek to illustrate here is that

${y}_i$

as the denominator (Equation (7)). A key point we seek to illustrate here is that

![]() ${I}^2$

values range markedly, from a minimum of 47.4% to a maximum of 94.2%. The usual value, based on the DerSimonian–Laird estimator of

${I}^2$

values range markedly, from a minimum of 47.4% to a maximum of 94.2%. The usual value, based on the DerSimonian–Laird estimator of

![]() ${\tau}^2$

(

${\tau}^2$

(

![]() ${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

) and the HT “typical variance” formula (

${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

) and the HT “typical variance” formula (

![]() ${\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2$

), is 92.1%.

${\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2$

), is 92.1%.

Table 1 Different values of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

obtained using the different definitions, with different choices of estimators for

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

obtained using the different definitions, with different choices of estimators for

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\sigma}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

and

${\boldsymbol{\sigma}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\tau}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

, applied to studies of BCG vaccine

${\boldsymbol{\tau}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

, applied to studies of BCG vaccine

Note: The bold entry is the “standard” choice (

![]() ${\boldsymbol{I}}_{\boldsymbol{MM}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

) as introduced by Higgins and Thompson.

${\boldsymbol{I}}_{\boldsymbol{MM}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

) as introduced by Higgins and Thompson.

HT, Higgins and Thompson; TCS, Takkouche, Cadarso-Suárez, and Spiegelman; DL, DerSimonian–Laird; HS, Hunter–Schmidt; SJ, Sidik–Jonkman; MLE, maximum likelihood; REML, restricted maximum likelihood; EB, empirical Bayes; PM, Paule–Mandel.

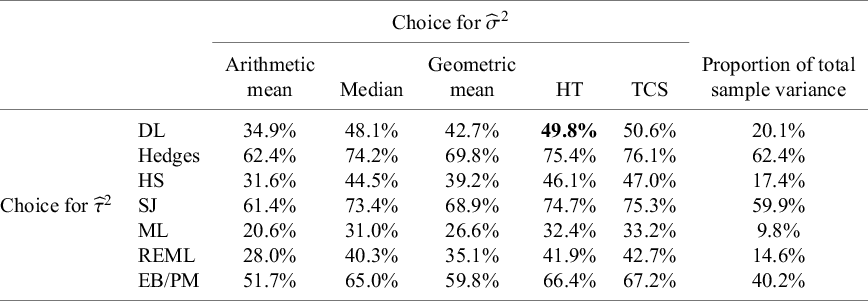

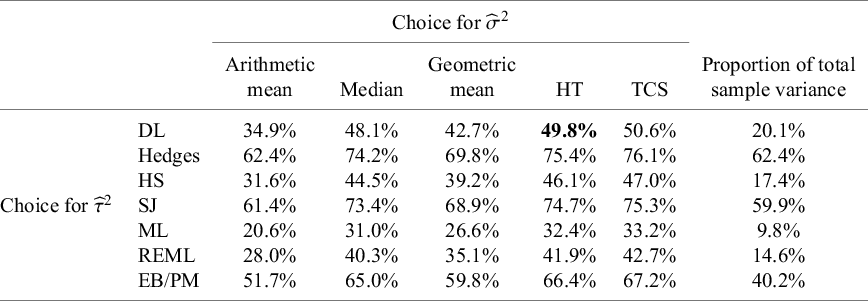

The second example is a set of results from 19 studies examining how teachers’ expectations influence their pupils’ intelligence quotient (IQ) scores, a phenomenon sometimes labeled as the “Pygmalion effect” using data provided by Raudenbush (Table 2).Reference Raudenbush30 The effect measure for this example is the standardized mean difference. Data were obtained from the metadata R package.Reference White, Nobles, Senior, Hamilton and Viechtbauer31 Again,

![]() ${I}^2$

values range notably, from a minimum of 9.8% to a maximum of 76.1%, with the usual value using

${I}^2$

values range notably, from a minimum of 9.8% to a maximum of 76.1%, with the usual value using

![]() ${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

and

${\widehat{\tau}}_{DL}^2$

and

![]() ${\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2$

being

${\widehat{\sigma}}_{HT}^2$

being

![]() ${I}_{MM}^2$

= 49.8%. The question then arises as to whether any of these variants is “more correct” than others, and we turn to this question in the following section by conducting a small simulation study.

${I}_{MM}^2$

= 49.8%. The question then arises as to whether any of these variants is “more correct” than others, and we turn to this question in the following section by conducting a small simulation study.

Table 2 Different values of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

obtained using different definitions, with different choices of estimators for

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

obtained using different definitions, with different choices of estimators for

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\sigma}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

and

${\boldsymbol{\sigma}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\tau}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

, applied to studies on the “Pygmalion effect”

${\boldsymbol{\tau}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

, applied to studies on the “Pygmalion effect”

Note: The bold entry is the “standard” choice (

![]() ${\boldsymbol{I}}_{\boldsymbol{MM}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

) as introduced by Higgins and Thompson.

${\boldsymbol{I}}_{\boldsymbol{MM}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

) as introduced by Higgins and Thompson.

HT, Higgins and Thompson; TCS, Takkouche, Cadarso-Suárez, and Spiegelman; DL, DerSimonian–Laird; HS, Hunter–Schmidt; SJ, Sidik–Jonkman; MLE, maximum likelihood; REML, restricted maximum likelihood; EB, empirical Bayes; PM, Paule–Mandel.

3.2 A simulation study

3.2.1 Simulation design

We conducted a small simulation study to examine the different approximations to the “typical” within-study variance in Equations (3) and (8) in the context of a very large meta-analysis (1,000 studies). For each meta-analysis, we drew

![]() $k$

= 1,000 effect parameters

$k$

= 1,000 effect parameters

![]() ${\theta}_i$

from a normal distribution with

${\theta}_i$

from a normal distribution with

![]() $\mu =0$

and

$\mu =0$

and

![]() ${\tau}^2=0.001$

and then generated individual scores on a continuous outcome for two-arm studies from normal distributions with means

${\tau}^2=0.001$

and then generated individual scores on a continuous outcome for two-arm studies from normal distributions with means

![]() ${\theta}_i$

and 0 for the experimental and control arms, respectively, and with a between-individual variance of 1 for both arms. The effect measure for each study was Hedges’ g, that is, the standardized mean difference as presented by Hedges and Olkin.Reference Hedges and Olkin32 We assigned arm sizes of 300, 350, 400, 450, and 1,000 individuals, with each value being assigned to 200 studies in the meta-analysis, with equal arm sizes for the two arms within each study. Total study sizes were therefore 600, 700, 800, 900, or 2,000 individuals, and the corresponding within-study variances (

${\theta}_i$

and 0 for the experimental and control arms, respectively, and with a between-individual variance of 1 for both arms. The effect measure for each study was Hedges’ g, that is, the standardized mean difference as presented by Hedges and Olkin.Reference Hedges and Olkin32 We assigned arm sizes of 300, 350, 400, 450, and 1,000 individuals, with each value being assigned to 200 studies in the meta-analysis, with equal arm sizes for the two arms within each study. Total study sizes were therefore 600, 700, 800, 900, or 2,000 individuals, and the corresponding within-study variances (

![]() ${\sigma}_i^2$

) were 0.0067, 0.0057, 0.0050, 0.0044, or 0.0020.

${\sigma}_i^2$

) were 0.0067, 0.0057, 0.0050, 0.0044, or 0.0020.

We simulated 10,000 meta-analyses using R version 4.3.3.33 For each simulated meta-analysis, we computed the within-study effect estimate (

![]() ${y}_i$

) and resulting “true”

${y}_i$

) and resulting “true”

![]() ${I}^2$

using a general weighted sums of squares approach (Equation (8)) based on known values of

${I}^2$

using a general weighted sums of squares approach (Equation (8)) based on known values of

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() ${\sigma}_i^2$

and simulated values of

${\sigma}_i^2$

and simulated values of

![]() ${\theta}_i$

. We compared these true values with the values yielded by replacing

${\theta}_i$

. We compared these true values with the values yielded by replacing

![]() ${\tau}^2$

in Equation (3) with the variance of the effect parameters

${\tau}^2$

in Equation (3) with the variance of the effect parameters

![]() ${\theta}_i$

(to avoid selecting a specific estimator for

${\theta}_i$

(to avoid selecting a specific estimator for

![]() ${\tau}^2$

) and using different estimators of

${\tau}^2$

) and using different estimators of

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

in Equation (3): arithmetic mean, median, HT (Equation (5)), and Takkouche and colleagues (Equation (6)). We also included the method using the total sampling variance of the observed effect estimates (Equation (7)).

${\sigma}^2$

in Equation (3): arithmetic mean, median, HT (Equation (5)), and Takkouche and colleagues (Equation (6)). We also included the method using the total sampling variance of the observed effect estimates (Equation (7)).

3.2.2 Simulation results

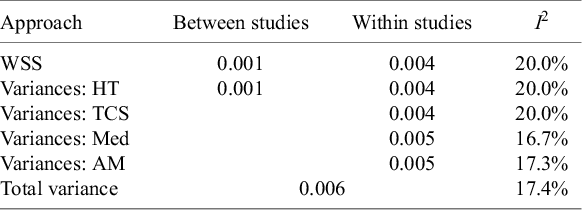

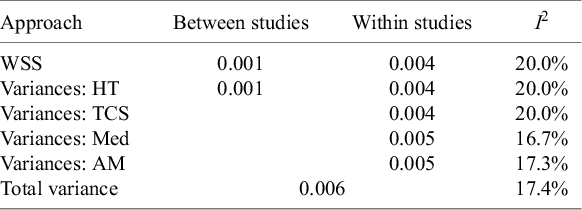

Table 3 shows the results of the simulation. Weighted sums of squares

![]() $WS{S}_b$

and

$WS{S}_b$

and

![]() $WS{S}_w$

(see Equation (8)) yielded values of 0.001 and 0.004, respectively, the former corresponding to the preset known value of the between-study variance component and the latter defining the true value of the within-study variance component (this coincides with the harmonic mean of the vector of five preset

$WS{S}_w$

(see Equation (8)) yielded values of 0.001 and 0.004, respectively, the former corresponding to the preset known value of the between-study variance component and the latter defining the true value of the within-study variance component (this coincides with the harmonic mean of the vector of five preset

![]() ${\sigma}_i^2$

values), leading to a true parameter value of

${\sigma}_i^2$

values), leading to a true parameter value of

![]() ${\iota}^2=20.0\%$

. Among the methods we compared, the formulae proposed by HT and by Takkouche and colleagues both yielded the correct average values of 0.004 for within-study variation. Conversely, using the median (0.005) or the arithmetic mean (0.005) led to the overestimation of within-study variation, resulting in an underestimation of

${\iota}^2=20.0\%$

. Among the methods we compared, the formulae proposed by HT and by Takkouche and colleagues both yielded the correct average values of 0.004 for within-study variation. Conversely, using the median (0.005) or the arithmetic mean (0.005) led to the overestimation of within-study variation, resulting in an underestimation of

![]() ${\iota}^2$

(by 3.3% and 2.7%, respectively). Lastly, the method using the total sampling variance of the observed effect estimates also underestimated the true value of

${\iota}^2$

(by 3.3% and 2.7%, respectively). Lastly, the method using the total sampling variance of the observed effect estimates also underestimated the true value of

![]() ${I}^2$

with an average value of 17.4%. Therefore, the different methods proposed to quantify a representative value of the within-study variation across studies,

${I}^2$

with an average value of 17.4%. Therefore, the different methods proposed to quantify a representative value of the within-study variation across studies,

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

, showed some discrepancies that affected the estimation of

${\sigma}^2$

, showed some discrepancies that affected the estimation of

![]() ${I}^2$

using Equation (3), with only the Takkouche and the HT methods performing close to the general formula presented in Equation (8). The lesson from our simulations is that only these two approaches should be considered (from those compared) for summarizing within-study variances across studies. Comparisons of these two methods in less favorable simulated scenarios can be found elsewhere.Reference Böhning, Lerdsuwansri and Holling34,

Reference Mittlbock and Heinzl35 Our simulations involved large numbers of studies so as to ensure that the between-study variance was well estimated. Further simulation studies might elucidate preferred estimators of between-study variance, although we would expect findings to align with existing recommendations for the choice of between-study variance.Reference Langan, Higgins and Simmonds22,

Reference Langan, Higgins and Jackson23

${I}^2$

using Equation (3), with only the Takkouche and the HT methods performing close to the general formula presented in Equation (8). The lesson from our simulations is that only these two approaches should be considered (from those compared) for summarizing within-study variances across studies. Comparisons of these two methods in less favorable simulated scenarios can be found elsewhere.Reference Böhning, Lerdsuwansri and Holling34,

Reference Mittlbock and Heinzl35 Our simulations involved large numbers of studies so as to ensure that the between-study variance was well estimated. Further simulation studies might elucidate preferred estimators of between-study variance, although we would expect findings to align with existing recommendations for the choice of between-study variance.Reference Langan, Higgins and Simmonds22,

Reference Langan, Higgins and Jackson23

Table 3 Results from the simulation study

WSS, weighted sums of squares; HT, Higgins and Thompson; TCS, Takkouche, Cadarso-Suárez, and Spiegelman (harmonic mean); Med, median; AM, arithmetic mean.

4 Expressing uncertainty in

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

Values of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index can be highly volatile when based on a small number of studies.Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Evangelou36 In many fields, very few studies tend to be included in meta-analyses (with a median of 3 having been reported in the health areaReference Davey, Turner, Clarke and Higgins37). HT originally derived formulae to calculate a confidence interval around

${I}^2$

index can be highly volatile when based on a small number of studies.Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Evangelou36 In many fields, very few studies tend to be included in meta-analyses (with a median of 3 having been reported in the health areaReference Davey, Turner, Clarke and Higgins37). HT originally derived formulae to calculate a confidence interval around

![]() ${I}^2$

based on

${I}^2$

based on

![]() ${H}^2$

, another metric for quantifying inconsistency in meta-analysis sometimes known as Birge’s ratio.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 An alternative, preferable, confidence interval for

${H}^2$

, another metric for quantifying inconsistency in meta-analysis sometimes known as Birge’s ratio.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 An alternative, preferable, confidence interval for

![]() ${I}^2$

is based on a noncentral chi-squared distribution,Reference Hedges and Pigott38 used by Orsini.Reference Orsini, Bottai and Higgins39 Hedges and Pigott note that this is the distribution of Q under a fixed-effects model, while under a random-effects model it has a gamma distribution.Reference Hedges and Pigott38 These results are used as the default in the metan macro for Stata.Reference Fisher, Harris and Bradburn40

${I}^2$

is based on a noncentral chi-squared distribution,Reference Hedges and Pigott38 used by Orsini.Reference Orsini, Bottai and Higgins39 Hedges and Pigott note that this is the distribution of Q under a fixed-effects model, while under a random-effects model it has a gamma distribution.Reference Hedges and Pigott38 These results are used as the default in the metan macro for Stata.Reference Fisher, Harris and Bradburn40

Confidence intervals for

![]() ${I}^2$

may also be derived from confidence intervals for

${I}^2$

may also be derived from confidence intervals for

![]() ${\tau}^2$

. Methods for these include the Q-profile method,Reference Knapp, Biggerstaff and Hartung41,

Reference Viechtbauer42 a generalized Q-statistic method,Reference Hartung and Knapp43,

Reference Jackson44 and a profile-likelihood method,Reference Hardy and Thompson45,

Reference Viechtbauer and Lopez-Lopez46 all of which are implemented in the metafor package for R.Reference Viechtbauer27,

33 Additional approaches have been developed that do not require a known sampling distribution of the Q-statisticReference Kulinskaya and Dollinger47,

Reference Kulinskaya, Dollinger and Bjorkestol48 an assumption which has been deemed unrealistic in most applied situations.Reference Hoaglin19 To the best of our knowledge, no simulation studies comparing all existing methods have been conducted to date, although an empirical comparison of the performance of some of them was recently conducted by Wang and colleagues.Reference Wang, DelRocco and Lin49

${\tau}^2$

. Methods for these include the Q-profile method,Reference Knapp, Biggerstaff and Hartung41,

Reference Viechtbauer42 a generalized Q-statistic method,Reference Hartung and Knapp43,

Reference Jackson44 and a profile-likelihood method,Reference Hardy and Thompson45,

Reference Viechtbauer and Lopez-Lopez46 all of which are implemented in the metafor package for R.Reference Viechtbauer27,

33 Additional approaches have been developed that do not require a known sampling distribution of the Q-statisticReference Kulinskaya and Dollinger47,

Reference Kulinskaya, Dollinger and Bjorkestol48 an assumption which has been deemed unrealistic in most applied situations.Reference Hoaglin19 To the best of our knowledge, no simulation studies comparing all existing methods have been conducted to date, although an empirical comparison of the performance of some of them was recently conducted by Wang and colleagues.Reference Wang, DelRocco and Lin49

5 Interpretation of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

The

![]() ${I}^2$

index is often interpreted as the amount of heterogeneity among studies, that is, as a measure of the variability across studies in true effect sizes underlying the effect estimates. Despite being widespread in the literature, this interpretation is incorrect. Numerous papers have explained this misinterpretation, and we refer the reader to several clear expositions.Reference Borenstein, Higgins, T Hedges and Rothstein16,

Reference Rücker, Schwarzer, Carpenter and Schumacher17,

Reference Borenstein50–

Reference Borenstein52 The

${I}^2$

index is often interpreted as the amount of heterogeneity among studies, that is, as a measure of the variability across studies in true effect sizes underlying the effect estimates. Despite being widespread in the literature, this interpretation is incorrect. Numerous papers have explained this misinterpretation, and we refer the reader to several clear expositions.Reference Borenstein, Higgins, T Hedges and Rothstein16,

Reference Rücker, Schwarzer, Carpenter and Schumacher17,

Reference Borenstein50–

Reference Borenstein52 The

![]() ${I}^2$

index measures the amount of heterogeneity in relation to the sampling error associated with the effect estimates feeding into the meta-analysis. As such, it is similar in interpretation to the intraclass correlation coefficient in clustered data. In fact, the letter

${I}^2$

index measures the amount of heterogeneity in relation to the sampling error associated with the effect estimates feeding into the meta-analysis. As such, it is similar in interpretation to the intraclass correlation coefficient in clustered data. In fact, the letter

![]() $I$

was originally chosen to represent “intraclass,” although we regard it as more constructive to consider the

$I$

was originally chosen to represent “intraclass,” although we regard it as more constructive to consider the

![]() $I$

to stand for “inconsistency.”

$I$

to stand for “inconsistency.”

![]() ${I}^2$

may be interpreted as the proportion of variability in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. Informally, it can be considered to reflect the extent to which confidence intervals displayed in a forest plot do not overlap with each other. This is the rationale for the characterization of

${I}^2$

may be interpreted as the proportion of variability in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. Informally, it can be considered to reflect the extent to which confidence intervals displayed in a forest plot do not overlap with each other. This is the rationale for the characterization of

![]() ${I}^2$

as a measure of inconsistency. If the results of the different studies are consistent with each other, their confidence intervals will have a high degree of overlap. If the results are inconsistent, there will be poor overlap in the confidence intervals. Note that the degree (or not) of overlap in confidence intervals is unrelated to the numbers on the effect measure axis.

${I}^2$

as a measure of inconsistency. If the results of the different studies are consistent with each other, their confidence intervals will have a high degree of overlap. If the results are inconsistent, there will be poor overlap in the confidence intervals. Note that the degree (or not) of overlap in confidence intervals is unrelated to the numbers on the effect measure axis.

![]() ${I}^2$

is invariant to a linear transformation of point estimates and confidence interval limits (in the metric used for the analysis, which is typically the logarithmic scale if the effect is measured on a ratio scale). Thus,

${I}^2$

is invariant to a linear transformation of point estimates and confidence interval limits (in the metric used for the analysis, which is typically the logarithmic scale if the effect is measured on a ratio scale). Thus,

![]() ${I}^2$

cannot be a measure of absolute heterogeneity, which is a quantity that is specific to the actual numbers on the axis.

${I}^2$

cannot be a measure of absolute heterogeneity, which is a quantity that is specific to the actual numbers on the axis.

A fundamental property of

![]() ${I}^2$

is that it will increase as the study effect estimates get more precise. Specifically, as studies get larger, confidence intervals around their effect estimates get narrower, and the overlap in confidence intervals across studies reduces, leading to larger values of

${I}^2$

is that it will increase as the study effect estimates get more precise. Specifically, as studies get larger, confidence intervals around their effect estimates get narrower, and the overlap in confidence intervals across studies reduces, leading to larger values of

![]() ${I}^2$

. This is apparent from Equation (3): For a given set of true effect sizes

${I}^2$

. This is apparent from Equation (3): For a given set of true effect sizes

![]() ${\theta}_i$

(and hence fixed

${\theta}_i$

(and hence fixed

![]() $\mathrm{Var}\left({\theta}_i\right)={\tau}^2$

), the value of

$\mathrm{Var}\left({\theta}_i\right)={\tau}^2$

), the value of

![]() ${\iota}^2$

increases as the typical within-study variance,

${\iota}^2$

increases as the typical within-study variance,

![]() ${\sigma}^2$

, decreases.Reference Rücker, Schwarzer, Carpenter and Schumacher17

${\sigma}^2$

, decreases.Reference Rücker, Schwarzer, Carpenter and Schumacher17

A much lesser problem in the interpretation of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index is that it has a minor dependence on the number of studies (

${I}^2$

index is that it has a minor dependence on the number of studies (

![]() $k$

) in the meta-analysis, as simulation studies have shown. Specifically,

$k$

) in the meta-analysis, as simulation studies have shown. Specifically,

![]() ${I}^2$

has been reported to yield biased estimates when the number of studies,

${I}^2$

has been reported to yield biased estimates when the number of studies,

![]() $k$

, is very small,Reference von Hippel25 similar to the pseudo-

$k$

, is very small,Reference von Hippel25 similar to the pseudo-

![]() ${R}^2$

statistic, another ratio measure in meta-analysis that requires estimation of

${R}^2$

statistic, another ratio measure in meta-analysis that requires estimation of

![]() ${\tau}^2.$

Reference Lopez-Lopez, Marin-Martinez, Sanchez-Meca, Van den Noortgate and Viechtbauer53 Furthermore, the

${\tau}^2.$

Reference Lopez-Lopez, Marin-Martinez, Sanchez-Meca, Van den Noortgate and Viechtbauer53 Furthermore, the

![]() ${I}^2$

index is closely related to the

${I}^2$

index is closely related to the

![]() $Q$

statistic, and hence, analogous to the low statistical power of the test based on the

$Q$

statistic, and hence, analogous to the low statistical power of the test based on the

![]() $Q$

statistic, it has substantial uncertainty unless a large number of results is combined.Reference Mittlbock and Heinzl35,

Reference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella54 Performance of both the Q-statistic and the

$Q$

statistic, it has substantial uncertainty unless a large number of results is combined.Reference Mittlbock and Heinzl35,

Reference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella54 Performance of both the Q-statistic and the

![]() ${I}^2$

index has also been found to be affected by publication bias simulated by Augusteijn and colleagues, who additionally developed a web-based application to explore the potential impact of publication bias on the assessment of heterogeneity for a given meta-analytic data set.Reference Augusteijn, van Aert and van Assen55

${I}^2$

index has also been found to be affected by publication bias simulated by Augusteijn and colleagues, who additionally developed a web-based application to explore the potential impact of publication bias on the assessment of heterogeneity for a given meta-analytic data set.Reference Augusteijn, van Aert and van Assen55

An important additional point worth noting here is that there are technical problems with

![]() ${I}^2$

arising from the fact that the within-study variances are not known but estimated with error. These problems, which will be more important when study estimates have low precision, are well articulated by Hoaglin.Reference Hoaglin19,

Reference Hoaglin56

${I}^2$

arising from the fact that the within-study variances are not known but estimated with error. These problems, which will be more important when study estimates have low precision, are well articulated by Hoaglin.Reference Hoaglin19,

Reference Hoaglin56

5.1 What is a large value of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

?

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

?

It is tempting to seek ranges or thresholds for the interpretation of

![]() ${I}^2$

: What is a large amount of inconsistency? The original paper proposing the index proposed that “mild heterogeneity might account for less than 30 per cent of the variability in point estimates, and notable heterogeneity substantially more than 50 per cent.” The use of the word “heterogeneity” in these proposals, while correct, may have led readers to believe the descriptors “mild” and “notable” related to the amount of heterogeneity rather than the amount of inconsistency. This is unfortunate. The arguments were based informally on the connection between heterogeneity and inconsistency for situations in which the chi-squared test for heterogeneity achieves statistical significance (at a 5% level) for around 10–30 studies, with meta-analyses of randomized trials very much in mind.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 The benchmarks did not directly consider the absolute magnitude of heterogeneity, as measured by

${I}^2$

: What is a large amount of inconsistency? The original paper proposing the index proposed that “mild heterogeneity might account for less than 30 per cent of the variability in point estimates, and notable heterogeneity substantially more than 50 per cent.” The use of the word “heterogeneity” in these proposals, while correct, may have led readers to believe the descriptors “mild” and “notable” related to the amount of heterogeneity rather than the amount of inconsistency. This is unfortunate. The arguments were based informally on the connection between heterogeneity and inconsistency for situations in which the chi-squared test for heterogeneity achieves statistical significance (at a 5% level) for around 10–30 studies, with meta-analyses of randomized trials very much in mind.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 The benchmarks did not directly consider the absolute magnitude of heterogeneity, as measured by

![]() ${\tau}^2$

.

${\tau}^2$

.

The most widely cited paper about

![]() ${I}^2$

proposed “naive categorisation of values for

${I}^2$

proposed “naive categorisation of values for

![]() ${I}^2$

would not be appropriate for all circumstances, although we would tentatively assign adjectives of low, moderate, and high to

${I}^2$

would not be appropriate for all circumstances, although we would tentatively assign adjectives of low, moderate, and high to

![]() ${I}^2$

values of 25%, 50%, and 75%.”Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman4 Again, these proposals were intended to apply only to randomized trials. Despite the caveats, these benchmarks have become widely (mis)used and applied to situations far beyond meta-analyses of trials.

${I}^2$

values of 25%, 50%, and 75%.”Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman4 Again, these proposals were intended to apply only to randomized trials. Despite the caveats, these benchmarks have become widely (mis)used and applied to situations far beyond meta-analyses of trials.

In an attempt to curb the overzealous use of the thresholds, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions in 2008 proposed overlapping ranges, again intended for use only with randomized trials: 0% to 40% might not be important; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity.Reference Higgins, Thomas and Chandler57 These suggestions were accompanied by clear guidance that “the importance of the observed value of

![]() ${I}^2$

depends on (i) magnitude and direction of effects and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g., P-value from the chi-squared test, or a confidence interval for

${I}^2$

depends on (i) magnitude and direction of effects and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g., P-value from the chi-squared test, or a confidence interval for

![]() ${I}^2$

),” advice which has again largely been ignored in practice.

${I}^2$

),” advice which has again largely been ignored in practice.

Although these benchmarks can be helpful as a very rough guide, they should not be used to categorize meta-analysis data sets or to decide on whether, or how, to combine the results. We particularly discourage the use of thresholds for

![]() ${I}^2$

to decide between adopting fixed-effect(s) or random-effects meta-analysis models, because such decisions should be made on the basis of the question being asked rather than characteristics of the data.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein58 Empirical investigations of typical values of

${I}^2$

to decide between adopting fixed-effect(s) or random-effects meta-analysis models, because such decisions should be made on the basis of the question being asked rather than characteristics of the data.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein58 Empirical investigations of typical values of

![]() ${I}^2$

can provide some useful pointers as to how a particular meta-analysis data set compares with others in related areas. Rhodes and colleagues reanalyzed 9,895 meta-analysis data sets from Cochrane reviews and fitted distributions to them.Reference Rhodes, Turner and Higgins59 For meta-analyses of trials with binary outcomes, the median value of

${I}^2$

can provide some useful pointers as to how a particular meta-analysis data set compares with others in related areas. Rhodes and colleagues reanalyzed 9,895 meta-analysis data sets from Cochrane reviews and fitted distributions to them.Reference Rhodes, Turner and Higgins59 For meta-analyses of trials with binary outcomes, the median value of

![]() ${I}^2$

was 22% for log odds ratios, with interquartile range (IQR) 12% to 39%. For continuous outcomes meta-analysis, the median was 40% for standardized mean differences, with IQR 15% to 73%. Such a difference between binary and continuous outcomes has been noted by others.Reference Alba, Alexander, Chang, Maclsaac, DeFry and Guyatt60 Differences have also been reported depending on the choice of effect measure within categoricalReference Rhodes, Turner and Higgins59,

Reference Papageorgiou, Tsiranidou, Antonoglou, Deschner and Jager61 and continuousReference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella54,

Reference Rhodes, Turner and Higgins59 outcomes, with, for example, inconsistency being higher for risk differences than for odds ratios or risk ratios.

${I}^2$

was 22% for log odds ratios, with interquartile range (IQR) 12% to 39%. For continuous outcomes meta-analysis, the median was 40% for standardized mean differences, with IQR 15% to 73%. Such a difference between binary and continuous outcomes has been noted by others.Reference Alba, Alexander, Chang, Maclsaac, DeFry and Guyatt60 Differences have also been reported depending on the choice of effect measure within categoricalReference Rhodes, Turner and Higgins59,

Reference Papageorgiou, Tsiranidou, Antonoglou, Deschner and Jager61 and continuousReference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella54,

Reference Rhodes, Turner and Higgins59 outcomes, with, for example, inconsistency being higher for risk differences than for odds ratios or risk ratios.

Application of

![]() ${I}^2$

to results other than treatment effects from randomized trials can yield extreme results. An overview of 134 meta-analyses of prevalence studies found a median

${I}^2$

to results other than treatment effects from randomized trials can yield extreme results. An overview of 134 meta-analyses of prevalence studies found a median

![]() ${I}^2$

value of 96.9% (IQR: 90.5% to 98.7%).Reference Migliavaca, Stein and Colpani62 An overview of 138 reliability generalization meta-analyses found a median

${I}^2$

value of 96.9% (IQR: 90.5% to 98.7%).Reference Migliavaca, Stein and Colpani62 An overview of 138 reliability generalization meta-analyses found a median

![]() ${I}^2$

value of 93.2% (IQR: 88.8% to 96.4%) when integrating untransformed alpha coefficients, with similar results for the transformations typically used in this field.Reference López-Ibáñez, López-Nicolás, Blázquez-Rincón and Sánchez-Meca63 These very high values reflect the higher precision with which these quantities are estimated in relation to the underlying heterogeneity. For example, studies of prevalence can be very large, being based on large surveys or databases. In this situation, even trivially small differences in prevalence can lead to very large values of

${I}^2$

value of 93.2% (IQR: 88.8% to 96.4%) when integrating untransformed alpha coefficients, with similar results for the transformations typically used in this field.Reference López-Ibáñez, López-Nicolás, Blázquez-Rincón and Sánchez-Meca63 These very high values reflect the higher precision with which these quantities are estimated in relation to the underlying heterogeneity. For example, studies of prevalence can be very large, being based on large surveys or databases. In this situation, even trivially small differences in prevalence can lead to very large values of

![]() ${I}^2$

. The utility of the

${I}^2$

. The utility of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index is therefore questionable in such situations, although as a statistic it cannot be said to be misleading or wrong.

${I}^2$

index is therefore questionable in such situations, although as a statistic it cannot be said to be misleading or wrong.

6 Extensions and repurposing of

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

${\boldsymbol{I}}^{\boldsymbol{2}}$

The popularity of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index has led to several extensions for application to specific types of meta-analysis. One of these is to meta-analyze models with covariates (known as moderator analysis or meta-regression). Here, part of the between-study variation is hoped to be explained by covariates, with some residual variation that cannot be accounted for by the model covariates. In this context,

${I}^2$

index has led to several extensions for application to specific types of meta-analysis. One of these is to meta-analyze models with covariates (known as moderator analysis or meta-regression). Here, part of the between-study variation is hoped to be explained by covariates, with some residual variation that cannot be accounted for by the model covariates. In this context,

![]() ${I}^2$

is interpreted as the proportion of the residual between-study variation (rather than the total variation) due to heterogeneity as opposed to random sampling error.Reference Harbord and Higgins64

${I}^2$

is interpreted as the proportion of the residual between-study variation (rather than the total variation) due to heterogeneity as opposed to random sampling error.Reference Harbord and Higgins64

Other extensions for more complex models include variants for multilevel meta-analytic modelsReference Nakagawa and Santos65 and multivariate meta-analysis,Reference White66,

Reference Jackson, White and Riley67 with the latter being applicable also in the context of network meta-analysis.Reference Balduzzi, Rücker, Nikolakopoulou, Salanti, Efthimiou and Schwarzer68,

Reference Jackson, Barrett, Rice, White and Higgins69 Multivariate versions were initially based on normal–normal random-effects models and have been extended to binomial–normal random-effects models for use, for example, in meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies.Reference Zhou and Dendukuri70 Analogs to

![]() ${I}^2$

have additionally been proposed for individual participant data meta-analysis and cluster-randomized trials.Reference Hemming, Hughes, McKenzie and Forbes71

${I}^2$

have additionally been proposed for individual participant data meta-analysis and cluster-randomized trials.Reference Hemming, Hughes, McKenzie and Forbes71

Vo and colleagues extend the use of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index to examine the impact of different sources of heterogeneity.Reference Vo, Porcher and Vansteelandt72 They partition the heterogeneity variance,

${I}^2$

index to examine the impact of different sources of heterogeneity.Reference Vo, Porcher and Vansteelandt72 They partition the heterogeneity variance,

![]() ${\tau}^2$

, into heterogeneity due to differences in participant characteristics (“case mix”) and heterogeneity due to other sources (largely methodological differences across the studies). They then propose versions of the

${\tau}^2$

, into heterogeneity due to differences in participant characteristics (“case mix”) and heterogeneity due to other sources (largely methodological differences across the studies). They then propose versions of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index for each of these components separately, expressing each as a proportion of the total variation in study estimates. Note that, in practice, the separation of these two sources of heterogeneity can only be achieved with individual participant data.Reference Vo, Porcher and Vansteelandt72

${I}^2$

index for each of these components separately, expressing each as a proportion of the total variation in study estimates. Note that, in practice, the separation of these two sources of heterogeneity can only be achieved with individual participant data.Reference Vo, Porcher and Vansteelandt72

The

![]() ${I}^2$

index has been repurposed for application to other problems. Montori and colleagues apply the

${I}^2$

index has been repurposed for application to other problems. Montori and colleagues apply the

![]() ${I}^2$

index to multiple waves of a survey, where at each wave an attempt is made to reach nonresponders to earlier waves.Reference Montori, Leung, Walter and Guyatt8 The

${I}^2$

index to multiple waves of a survey, where at each wave an attempt is made to reach nonresponders to earlier waves.Reference Montori, Leung, Walter and Guyatt8 The

![]() ${I}^2$

index calculated from answers to a survey question across multiple waves provides a measure of the inconsistency across waves due to response bias. Specifically, it describes the proportion of total variation in responses to the question, in successive waves, that is due to differences in the responders across waves rather than random variation within each wave. Finally, Bowden and colleagues adopted the

${I}^2$

index calculated from answers to a survey question across multiple waves provides a measure of the inconsistency across waves due to response bias. Specifically, it describes the proportion of total variation in responses to the question, in successive waves, that is due to differences in the responders across waves rather than random variation within each wave. Finally, Bowden and colleagues adopted the

![]() ${I}^2$

index for use in the field of Mendelian randomization to quantify the strength of violation of an assumption made in two-sample Mendelian randomization.Reference Bowden, Del Greco, Minelli, Davey Smith, Sheehan and Thompson73

${I}^2$

index for use in the field of Mendelian randomization to quantify the strength of violation of an assumption made in two-sample Mendelian randomization.Reference Bowden, Del Greco, Minelli, Davey Smith, Sheehan and Thompson73

7 Alternative indices of heterogeneity

Alongside the

![]() ${I}^2$

index, popular statistics for assessing heterogeneity in a meta-analysis are the Q-statistic and the between-study variance parameter. The latter is easier to interpret when reported as the standard deviation,

${I}^2$

index, popular statistics for assessing heterogeneity in a meta-analysis are the Q-statistic and the between-study variance parameter. The latter is easier to interpret when reported as the standard deviation,

![]() $\tau$

. This standard deviation may also be used to calculate prediction intervals around the overall effect estimate.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter74 Prediction intervals provide a range of plausible values for the true effect in a further primary study similar to those already in the meta-analysis. They directly portray the amount of heterogeneity observed in the meta-analysis on the metric used to present the meta-analytic results. The use and reporting of prediction intervals is now widely advocated in the meta-analytic literature.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter74–

Reference Stijnen, White, Schmid, Schmid, Stijnen and White80

$\tau$

. This standard deviation may also be used to calculate prediction intervals around the overall effect estimate.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter74 Prediction intervals provide a range of plausible values for the true effect in a further primary study similar to those already in the meta-analysis. They directly portray the amount of heterogeneity observed in the meta-analysis on the metric used to present the meta-analytic results. The use and reporting of prediction intervals is now widely advocated in the meta-analytic literature.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter74–

Reference Stijnen, White, Schmid, Schmid, Stijnen and White80

Assessment of heterogeneity is a key aspect of any meta-analysis, so it is not surprising that several alternatives to these indices have been proposed.Reference Stogiannis, Siannis and Androulakis81 Lin and colleaguesReference Lin, Chu and Hodges82 developed two indices intended for meta-analyses including outlying studies and reported a robust performance under such scenarios.Reference Ma, Lin, Qu, Zhu and Chu83 Crippa and colleagues proposed another scale-invariant measure, which, unlike the

![]() ${I}^2$

index, requires neither quantification of a typical value of the within-study variance nor an assumption of homogeneity of these quantities.Reference Crippa, Khudyakov, Wang, Orsini and Spiegelman84 The proposed index quantifies the between-study heterogeneity relative to the variance of the summary random-effects estimate. A disadvantage of this measure is the potential for bias, especially with a small number of studies.Reference Stogiannis, Siannis and Androulakis81 The coefficient of variation, calculated as the ratio between

${I}^2$

index, requires neither quantification of a typical value of the within-study variance nor an assumption of homogeneity of these quantities.Reference Crippa, Khudyakov, Wang, Orsini and Spiegelman84 The proposed index quantifies the between-study heterogeneity relative to the variance of the summary random-effects estimate. A disadvantage of this measure is the potential for bias, especially with a small number of studies.Reference Stogiannis, Siannis and Androulakis81 The coefficient of variation, calculated as the ratio between

![]() $\tau$

and either the fixed-effectsReference Takkouche, CadarsoSurez and Spiegelman5 or random-effectsReference Takkouche, Khudyakov, Costa-Bouzas and Spiegelman85 overall estimate, has been proposed as a complementary measure of heterogeneity, although it can be expected to yield very large values when the effect estimate is small, which hampers interpretation.Reference Cairns and Prendergast86

$\tau$

and either the fixed-effectsReference Takkouche, CadarsoSurez and Spiegelman5 or random-effectsReference Takkouche, Khudyakov, Costa-Bouzas and Spiegelman85 overall estimate, has been proposed as a complementary measure of heterogeneity, although it can be expected to yield very large values when the effect estimate is small, which hampers interpretation.Reference Cairns and Prendergast86

Last, we note that HT originally proposed the

![]() ${I}^2$

index along with two other quantities.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 The first of these was the H index or Birge’s ratio, closely related to the standard (Q-based) definition of

${I}^2$

index along with two other quantities.Reference Higgins and Thompson3 The first of these was the H index or Birge’s ratio, closely related to the standard (Q-based) definition of

![]() ${I}^2$

, and with a modified version subsequently proposed.Reference Mittlbock and Heinzl35 The second was the

${I}^2$

, and with a modified version subsequently proposed.Reference Mittlbock and Heinzl35 The second was the

![]() ${R}^2$

index, a ratio of the variances of the random-effects and the fixed-effects overall estimates in the meta-analysis, subsequently rebranded as the diamond ratio.Reference Cairns, Cumming, Calin-Jageman and Prendergast87

${R}^2$

index, a ratio of the variances of the random-effects and the fixed-effects overall estimates in the meta-analysis, subsequently rebranded as the diamond ratio.Reference Cairns, Cumming, Calin-Jageman and Prendergast87

8 Discussion

Papers proposing the

![]() ${I}^2$

index for meta-analysis are among the most highly cited in the medical research literature, with the original papers in Statistics in Medicine and BMJ having been cited in excess of 35,000 and 60,000 times, respectively. In this paper, we have reviewed the properties and interpretations of the

${I}^2$

index for meta-analysis are among the most highly cited in the medical research literature, with the original papers in Statistics in Medicine and BMJ having been cited in excess of 35,000 and 60,000 times, respectively. In this paper, we have reviewed the properties and interpretations of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index. We overviewed different ways of defining the statistic and illustrated how different definitions can lead to different values.

${I}^2$

index. We overviewed different ways of defining the statistic and illustrated how different definitions can lead to different values.

When a fixed-effects model is assumed, there is no estimation of the between-study variance,

![]() ${\tau}^2$

, and hence, we regard the standard (Q-based) definition to be a natural choice to compute

${\tau}^2$

, and hence, we regard the standard (Q-based) definition to be a natural choice to compute

![]() ${I}^2$

. Furthermore, if both fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses are planned, then the Q-based definition has the advantage that it will yield the same result for both statistical models. In the context of a random-effects meta-analysis, other definitions for

${I}^2$

. Furthermore, if both fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses are planned, then the Q-based definition has the advantage that it will yield the same result for both statistical models. In the context of a random-effects meta-analysis, other definitions for

![]() ${I}^2$

are serious contenders. A particular problem is that the closest version to a parametric interpretation of the

${I}^2$

are serious contenders. A particular problem is that the closest version to a parametric interpretation of the

![]() ${I}^2$

index (our conceptual definition) involves the notion of a “typical” within-study variance term, which is a poorly defined quantity. As a result, we propose a general definition of

${I}^2$

index (our conceptual definition) involves the notion of a “typical” within-study variance term, which is a poorly defined quantity. As a result, we propose a general definition of

![]() ${I}^2$

based on weighted sums of squares and use this as a basis for a small simulation study. We suggest that this new definition may have a useful role in a range of future simulation studies investigating methods for estimating heterogeneity parameters or mean meta-analytic effects.

${I}^2$

based on weighted sums of squares and use this as a basis for a small simulation study. We suggest that this new definition may have a useful role in a range of future simulation studies investigating methods for estimating heterogeneity parameters or mean meta-analytic effects.

We believe the index plays a very valuable role in the meta-analysis toolkit, although we are concerned at the widespread misunderstanding and misinterpretation of it in practice. Common mistakes are to interpret the

![]() ${I}^2$

index as a measure of the absolute amount of heterogeneity across studies and to apply inappropriate thresholds for interpreting values of the index. It is important to remember that the

${I}^2$

index as a measure of the absolute amount of heterogeneity across studies and to apply inappropriate thresholds for interpreting values of the index. It is important to remember that the

![]() ${I}^2$