The morphological transformation known as the fish–tetrapod transition affected every part of the anatomy. If the skeleton of a fish member of the tetrapod stem group such as Eustenopteron (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1980) is compared to that of a limbed stem tetrapod such as Ichthyostega, Acanthostega, Crassigyrinus or Greererpeton (Clack Reference Clack2012), it will be found that they differ on every single point to a lesser or greater degree. Among the most drastic of these anatomical reconfigurations is that which affected the braincase. However, it is less well understood than the transformation of other parts of the anatomy, partly because braincases of early tetrapods are both rare and difficult to study by conventional techniques such as mechanical preparation. Here we present a new braincase specimen of the Devonian stem tetrapod Ventastega, and previously unpublished data on the braincase of Acanthostega, which cast new light on the early evolution of the tetrapod braincase. Both taxa have been studied by means of micro-computed tomography (μCT), allowing the delicate braincase anatomy to be completely freed from matrix and visualised (Figs 1–3).

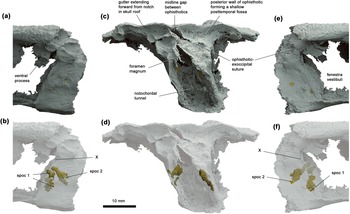

Figure 1 Skull roof and braincase of Ventastega curonica, specimen LDM G 81/807a-b, in dorsal (a, b), ventral (c), anterior (d), posterior (e), right lateral (f) and left lateral (g) views. Blender renderings of stl files from μCT scans. False colours: brown indicates skull roof; grey, braincase; orange, parasphenoid; turquoise, arcual plate; green, lateral line sulcus. In (a), suture lines of skull roof are indicated in black; in (f) and (g), the basioccipital-prootic suture has been indicated similarly. In (a), Fr denotes the frontal bone; It, intertemporal; Pa, parietal; Pof, postfrontal; Pp, postparietal; Prf, prefrontal; Su, supratemporal; and Ta, tabular.

Figure 2 Occipital region of Ventastega curonica, specimen LDM G 81/807a-b, in (a, b) left lateral, (c, d) posterior and (e, f) right lateral views. Blender renderings of stl files from μCT scan. False colours: grey, braincase and skull roof; gold, spino-occipital nerve canal fills. In (b, d, f), the braincase and skull roof are shown semi-transparent to reveal the course of the spino-occipital nerve canals. Spoc 1 and spoc 2 denote spino-occipital nerve canals 1 and 2; X indicates the groove for the vagus nerve.

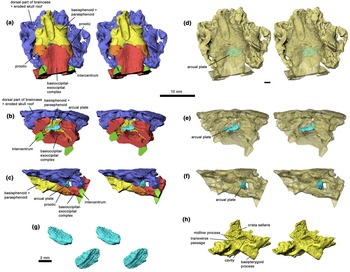

Figure 3 Braincase of Acanthostega gunnari, specimen UMZC T.1300d, stereo pairs in ventral (a), posterior (b) and left lateral (c) views. Semi-transparent models of same, showing arcual plate within the cranial cavity, in ventral (d), posterior (e) and left lateral (f) views. (g) Arcual plate stereo pair in posterodorsolateral (top) and anteroventrolateral (bottom) views. (h) Basisphenoid–parasphenoid complex, stereo pair, in left anterodorsolateral view. Rhino renderings of stl files from μCT scan. False colours. 10 mm scale bar applies to all figure elements except (g).

1. The transformation of the braincase from fish to tetrapod: what do we know?

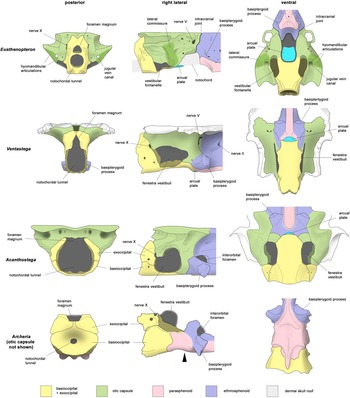

The endpoints of the braincase transformation from fish to tetrapod are quite well understood. The starting point is a fully ossified but kinetic braincase with an intracranial joint (Fig. 4, top), of the type seen in Eusthenopteron (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1980) and Gogonasus (Long et al. Reference Long, Barwick and Campbell1997), which fortuitously survives in almost unmodified (but less fully ossified) form in the extant coelacanth Latimeria (Dutel et al. Reference Dutel, Galland, Tafforeau, Long, Fagan, Janvier, Herrel, Santin, Clément and Herbin2019). In this type of braincase, the otic capsule is separated from the ethmosphenoid by a vertical joint that passes through the region of the trigeminal nerve foramina, though its exact relationship to these foramina is variable (Ahlberg Reference Ahlberg1991). The cranial notochord is unconstricted and passes through a tunnel in the basioccipital before traversing a basicranial fenestra that is partly floored by an arcual plate (an independent element resembling a vertebral intercentrum) and finally ending against a facet on the posterior face of the ethmosphenoid, immediately posterior to the hypophysial recess. The otic capsule carries on each side a lateral commissure, which straddles the jugular vein and provides articulation points for the hyomandibula. The contact between the otic capsule and occipital takes the form of a lateral otic fissure, which ends anteroventrally in a vestibular fontanelle. This fontanelle opens into the saccular region of the inner ear cavity, but is not connected to the hyomandibula. In Latimeria the fontanelle is absent.

Figure 4 Braincase reconstructions of Ventastega and Acanthostega, compared with the tetrapodomorph fish Eusthenopteron and the embolomere Archeria. Not to scale. Eusthenopteron modified from Jarvik (Reference Jarvik1980); Ventastega, original, combining data from LDM G 81/807a-b and LDM G 81/775 (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008); Acanthostega modified from Clack (Reference Clack1998), with additional data presented here; Archeria, original, based on photos of specimen FMNH UC 871 from Pardo (Reference Pardo2023). In the lateral view of Archeria, the black arrowhead indicates the position of the boundary between basioccipital and ethmosphenoid, which is concealed by the posterior extension of the parasphenoid. In the ventral view of Acanthostega, only a small part of the arcual plate is exposed between the basioccipital and ethmosphenoid; see Fig. 3d for a view of the complete arcual plate.

The finishing point of the transition can be taken, somewhat arbitrarily, to be represented by the condition in the vicinity of the tetrapod crown group node. This node corresponds to the last common ancestor of extant lissamphibians and amniotes, but the positions relative to the crown group node of important early tetrapod groups such as embolomeres (Fig. 4, bottom), temnospondyls and the various ‘lepospondyls’ are not unambiguously resolved in recent phylogenetic analyses (e.g., Clack et al. Reference Clack, Bennett, Carpenter, Davies, Fraser, Kearsey, Marshall, Millward, Otoo, Reeves, Ross, Ruta, Smithson, Smithson and Walsh2016, Reference Clack, Ruta, Milner, Marshall, Smithson and Smithson2019; Pardo et al. Reference Pardo, Szostakiwskyj, Ahlberg and Anderson2017; Marjanović & Laurin Reference Marjanović and Laurin2019). However, the known braincases of all these groups agree in lacking an intracranial joint; in having, instead of a basicranial fenestra, a transverse ventral fissure between the basioccipital and basisphenoid, which is bridged ventrally by the parasphenoid; in having at most a slender remnant of the cranial notochord; in lacking a lateral commissure; and in having the hyomandibula transformed into a stapes with its footplate lodged in a fenestra connecting with the inner ear, variously described as the fenestra vestibuli or fenestra ovalis (Clack Reference Clack2012).

These changes add up to a thorough transformation of the role of the braincase, in terms of both cranial mechanics and sound detection. The sequence of steps by which the transformation occurred, and the intermediate morphologies that were generated along the way, are thus of great interest for understanding the biology of the fish–tetrapod transition. However, the information available for the Devonian part of the tetrapod stem group that spans the fin-to-limb transition is quite limited.

Largely complete braincases, preserved in articulation with the skull roof, have been described from the elpistostegalians Panderichthys (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack and Luks̆evic̆s1996) and Tiktaalik (Downs et al. Reference Downs, Daeschler, Jenkins and Shubin2008). These braincases are scarcely modified from the Eusthenopteron-Gogonasus condition, even though the external head morphology is approaching that of tetrapods and the dermal intracranial joint has been lost. The endoskeletal intracranial joint, basicranial fenestra, notochordal tunnel through the basioccipital, and lateral commissure are still present. An arcual plate is present in Panderichthys but not in Tiktaalik. The only derived tetrapod character that has appeared is the large anterolaterally flaring buttress on the prootic; this is present in Tiktaalik, and may also be present in Panderichthys, although that part of the braincase is concealed by the palatoquadrate in the only known specimen of the otic region. A small vestibular fontanelle positioned anterior to the level of the lateral commissure, and a broad basioccipital with a somewhat ‘violin-shaped’ outline, are shared features unique to Panderichthys and Tiktaalik. In both genera the hyomandibula has been shortened distally (Brazeau & Ahlberg Reference Brazeau and Ahlberg2006; Downs et al. Reference Downs, Daeschler, Jenkins and Shubin2008), but it articulates with the lateral commissure and cannot be considered a stapes. In short, the elpistostegalians show only the very beginning of the transformation; they do however demonstrate that the rebuilding of the braincase and spiracular region lagged behind the loss of intracranial kinesis.

The earliest known tetrapod braincases are those of Acanthostega, Ichthyostega and Ventastega, all from the late Famennian (Clack Reference Clack1994a, Reference Clack1994b, Reference Clack1998; Jarvik Reference Jarvik1996; Clack et al. Reference Clack, Ahlberg, Finney, Dominguez Alonso, Robinson and Ketcham2003; Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008). One specimen of the early Famennian tetrapod Parmastega preserves the dorsalmost part of the otic capsules, showing strong prootic buttresses together with relatively small anterior and posterior semicircular canals, but not much else (Beznosov et al. Reference Beznosov, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Ruta and Ahlberg2019). The braincases of Acanthostega and Ichthyostega are essentially complete. Both differ from post-Devonian tetrapod braincases in two major respects: the basioccipital is fully notochordal, with no evidence for occipital condyles, and the parasphenoid does not extend backwards to cover the ventral cranial fissure (Clack Reference Clack1994a, Reference Clack1994b, Reference Clack1998; Jarvik Reference Jarvik1996; Clack et al. Reference Clack, Ahlberg, Finney, Dominguez Alonso, Robinson and Ketcham2003). Conversely, they agree with later tetrapod braincases in lacking an intracranial joint, a basicranial fenestra and a lateral commissure, and both have prootic buttresses. Beyond these points of agreement, they differ dramatically from each other. In Acanthostega the otic capsules are wide and more or less fill the ventral surface of the skull table, leaving only a narrow margin of exposed dermal bone. The vestibular fontanelle is very large, occupying most of the lateral wall of the otic region. By contrast, in Ichthyostega the otic capsules are narrow (apart from the prootic buttresses), leaving a wide expanse of exposed skull table on either side, and the vestibular fontanelle is small. These differences, which appear to relate to functionally different middle ears (Clack et al. Reference Clack, Ahlberg, Finney, Dominguez Alonso, Robinson and Ketcham2003), make it very difficult to determine whether either type represents the main line of evolution of tetrapod braincase architecture (Beznosov et al. Reference Beznosov, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Ruta and Ahlberg2019). The published braincase of Ventastega (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008) appears to resemble that of Acanthostega, but the entire occipital complex and much of the otic capsules are missing. The material presented here remedies this deficiency in our knowledge of Ventastega and presents new internal anatomical data from Acanthostega that compel a substantial reinterpretation of its braincase composition.

2. Ventastega and Acanthostega

Ventastega curonica Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Luks̆evic̆s and Lebedev1994, is known from only three localities in the Upper Devonian (Upper Famennian) Ketleri Formation, of western Latvia, namely the Ketleri, Pavāri-1 and Pavāri-2 sites. The Ketleri locality, on the right bank of the Venta River close to the abandoned Ķetleri farmhouse, has been known since the 1930s (Gross Reference Gross1933). It has yielded a wide variety of vertebrates including fishes and tetrapods (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Luks̆evic̆s and Lebedev1994; Lebedev & Lukševičs Reference Lebedev and Lukševičs2017, Reference Lebedev and Lukševičs2018), as well as trace fossils and recently found rhizocretes (Lukševičs et al. Reference Lukševičs, Stinkulis, Lebedev and Żilińska2017). Analysis by Ahlberg et al. (Reference Ahlberg, Luks̆evic̆s and Lebedev1994) demonstrated that cranial remains from Ketleri assigned to the taxon Panderichthys bystrowi (Gross Reference Gross1941) by E. Vorobyeva (Reference Vorobyeva1960, Reference Vorobyeva1962) belong to a tetrapod, which was given the name Ventastega curonica. At the Pavāri locality, fish remains were first found in the course of geological mapping in the late 1960s, in the outcrop on the left bank of the Ciecere River opposite the former Pavāri farmhouse; this is now designated the Pavāri-1 site. L. Lyarskaya carried out the first excavations there in 1970 and 1973 (Lyarskaya & Savvaitova Reference Lyarskaya, Savvaitova and Sorokin1974). Further excavations were carried out under the leadership of E. Lukševičs in 1988, 1989, 1991, 1995, 2001, 2005, 2011 and 2013, with the participation of not only Latvian but also foreign researchers (P. E. Ahlberg, H. Blom, O. Lebedev, L. Vyushkova). Recently, in 2019, a newly formed outcrop designated Pavāri-2 was discovered on the left bank of the Ciecere River near the confluence with the Paksīte River, at a distance of about 400 m from Pavāri-1 (Lukševičs et al. Reference Lukševičs, Alksnītis, Bērtiņa, Ješkins, Matisone and Visotina2022). A rich vertebrate assemblage typical for the Pavāri Member of the Ketleri Formation was found there; well-preserved tetrapod remains including lower jaws, clavicle, cleithrum and an almost complete scapulocoracoid are buried in poorly consolidated sandstones and silty-clayey deposits. An excavation at Pavāri-2 in 2023 also yielded well-preserved plant material. All tetrapod material from Pavāri is registered to the Latvian National Museum of Natural History, Latvijas Nacionālais Dabas Muzejs, with the letter code LDM G.

Acanthostega gunnari Jarvik, Reference Jarvik1952, was first described from two incomplete skulls recovered from the ‘Remigolepis Series’ (in modern terminology comprising the Aina Dal, Wimans Bjerg and Britta Dal Formations) of Wimans Bjerg on Gauss Halvø (Gauss Peninsula) and Celsius Bjerg on Ymer Ø (Ymer Island), in the East Greenland sedimentary basin (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1952). These formations belong to the Upper Famennian and are broadly contemporary with the Ketleri Formation (Esin et al. Reference Esin, Ginter, Ivanov, Lebedev, Luksevics, Avkhimovich, Golubtsov, Petukhova, Blieck and Turner2000; Blom et al. Reference Blom, Clack and Ahlberg2005). A new Acanthostega locality was discovered in 1970, in the Britta Dal Formation of Stensiö Bjerg, Gauss Halvø, by J. Nicholson (University of Cambridge). He collected three skulls, which fitted together into a single block, and deposited these in Cambridge, where they were rediscovered by J. A. Clack and registered by her at Cambridge University Museum of Zoology under specimen numbers UMZC T.1300a-j (Clack Reference Clack1988). A follow-up expedition in 1987, led jointly by J. A. Clack (University of Cambridge) and S. E. Bendix-Almgreen (Geologisk Museum, Copenhagen) found Nicholson's locality and collected an extensive material from what proved to be a substantial mass-death deposit (Bendix-Almgreen et al. Reference Bendix-Almgreen, Clack and Olsen1988). This material was registered to Geologisk Museum, Copenhagen. Subsequently, all the Acanthostega material from the Stensiö Bjerg locality was prepared mechanically and in some instances sectioned by diamond-wire saw, and described in a long series of papers; of particular interest here are those that describe the braincase (Clack Reference Clack1994a, Reference Clack1994b, Reference Clack1998; Clack et al. Reference Clack, Ahlberg, Finney, Dominguez Alonso, Robinson and Ketcham2003). For the study of the braincase, the key specimen proved to be UMZC T.1300d. An investigation of UMZC T.1300d by μCT was undertaken by J. Robinson for his PhD thesis at University College London (Robinson Reference Robinson2006), but never published in a journal article. Key findings from this investigation are included here.

3. Materials and methods

The partial skull of Ventastega presented here, LDM G 81/807a-b, was collected in 2013 from the Pavāri-1 locality, during an excavation by University of Latvia under the leadership of E. Lukševičs. This skull consists of two separate blocks broken apart before burial in a very fine-grained sandstone. These blocks were buried in a close proximity and match well along the crack. Both blocks were separately prepared under a Leica MZ16 binocular microscope using a mounted needle and brush and consolidated using polyvinyl butyral 1 % solution in spirit in the Laboratory of Mineralogy and Palaeontology (University of Latvia). They were scanned by μCT in 2018 at the University of Bristol School of Earth Sciences (Bristol, UK) on a Nikon XT H 225 μCT scanner (Nikon Metrology, Tring, UK). The two blocks were scanned separately. The anterior block – containing the prefrontals, anterior portion of the frontals, and anterior part of the braincase – was scanned at 160 kV and 230 μA, and produced 1,999 transverse slices (TIFF images) composed of isometric voxels with a resolution of 0.048 mm/pixel. The posterior block – containing the posterior part of the braincase and the skull table – was scanned at 135 kV and 210 μA, and produced 1,999 transverse slices (TIFF images) composed of isometric voxels with a resolution of 0.049 mm per pixel. The scans were segmented at Uppsala University by P. E. Ahlberg using Mimics 19.0 (Materialise NV) and the resulting stl files exported to Blender (Blender.org) for rendering. Figures were composed in Photoshop 22.1.1 (Adobe).

The braincase of Acanthostega, UMZC T.1300d, was collected by J. Nicholson in 1970 and mechanically prepared with dental mallet by members of the Clack team. It was scanned on an HRXCT system at Penn State University (Pennsylvania, USA). Manufactured by Universal Systems (www.universal-systems.com), this system consisted of a HD-600 CT system with subsystems from BIR and X-tek. The system had two energy sources, a large and a micro focal source with maximal energies of 320 kV and 225 kV respectively. The scan, which ran from the anterior extent of the specimen to approximately the middle of the exoccipitals and thus excluded the posterior end of the specimen, was produced with 2,400 views per rotation with 41 slices being produced per rotation, meaning the specimen was rotated 14 times within the x-ray field. This produced a scan series in 16-bit resolution (1,024 pixels by 1,024 pixels) comprising 574 slices each of 0.04397 mm thickness (i.e., approximately 23 slices per mm). Each slice has a field of view of 40 mm giving a pixel size of 0.03906 mm. Segmenting was carried out by J. Robinson using Mimics 7.1–8.1 (Materialise NV). Because the full data set of 574 slices was difficult to process with the computer power available at the time, every other slice was discarded to create a stack of 287 slices. All elements created in the Mimics project were imported into Rhino (McNeel) for rendering and were subjected to a smoothing transformation over all world coordinates with a factor of 1.5.

4. Description: Ventastega

The new braincase and skull roof LDM G 81/807a-b (Fig. 1) closely resembles the previously described LDM G 81/775 (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008) and clearly represents the same taxon, but the two specimens complement each other. LDM G 81/775 has one nasal preserved in articulation, whereas the nasals are missing in LDM G 81/807a-b, and correspondingly the preservation of the ethmosphenoid extends further anteriorly in LDM G 81/775 than in LDM G 81/807a-b (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008, fig. 1d). The ethmosphenoid part of the braincase is generally better preserved in LDM G 81/775, with less distortion and cracking. LDM G 81/775 is also associated with an articulated cheek, LDM G 81/776. Conversely, LDM G 81/807a-b has a complete otoccipital braincase (Fig. 1c, e–g).

In LDM G 81/775, the suture pattern of the posterior part of the skull roof is obscured by bone fusion (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008). By contrast, LDM G 81/807a-b shows a full set of sutures that can be traced with confidence (Fig. 1a). Importantly, it confirms the tentative observation from LDM G 81/775 that an intertemporal bone is present, intervening between the postfrontal and the supratemporal. Ventastega is the only Devonian tetrapod known to possess this bone, which is otherwise recorded from both sarcopterygian fishes and some post-Devonian tetrapods (see Discussion). Its lateral margin, which is sutural, divides into a longer anterolateral and shorter (postero)lateral segments, representing the contacts for the postorbital and squamosal respectively. The supratemporal, the largest bone in the marginal series, carries the posterior part of the squamosal contact and also forms the anterior margin of the spiracular notch. The tabular is a narrow, parallel-sided bone, bounded laterally by the spiracular notch.

The postparietals are relatively large bones, parallel-sided, only slightly shorter than the parietals, and have a long contact with the supratemporals. The posterior margin of the skull roof is indented by a pair of deep notches, which do not mark the postparietal-tabular sutures as might be expected but instead lie entirely within the postparietals. In posteroventral view, a short anteroventrally directed gutter can be seen to extend forward from each notch on the underside of the postparietal, to the contact with the braincase (Fig. 2c). This suggests that something inserted into these notches; given their position, and the documented presence of an anocleithrum (but not a supracleithrum, posttemporal, or extrascapulars) in Ventastega (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008), it seems likely that they accommodated a ligament extending from the skull to the anocleithrum. The rear margin of the skull roof is markedly asymmetrical, with the right corner more posterior than the left. A similar but opposite asymmetry is present in LDM G 81/775 (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008, figs 1a, 5a).

The parietals have a more complex shape, widest at the level of the pineal foramen and narrowing rapidly towards the anterior, where they suture with the frontals within the narrow and transversely concave interorbital region. The pineal foramen is oval with an anteroposterior long axis. An interesting pattern change is seen in the midline sutures at the level of the parietal-frontal contact. The midline sutures of the postparietals and parietals are almost perfectly straight and median, whereas the frontal-frontal contact is strongly asymmetrical, with the left frontal being both longer and wider posteriorly. Supraorbital lateral line sulci (Fig. 1a, green) are present on the frontals, extending posteriorly as far as the ‘step’ in the dorsal surface that demarcates the sloping anterior skull roof with its median gutter and anterior fontanelle (see also Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008, fig. 3) from the horizontal posterior skull roof. There are no more posterior lateral line sulci on the skull roof.

The bone pattern of the anterior skull roof has already been described by Ahlberg et al. (Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008) and is confirmed by the new specimen. However, there is a strong and apparently pathological asymmetry between the two prefrontal bones. The left prefrontal is normal, very similar in shape to the previously described example (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008), but the right is much shorter and has a circular notch in the anterolateral margin (Fig. 1, ‘lesion’). The margins of the bone and the notch are all natural, not broken, so these features were present in life. The bone thins slightly towards the notch on the internal surface, whereas the ornament on the external surface extends unbroken right to the edge; this suggests that the notch formed in response to a soft-tissue growth such as a cyst, tumour or abscess, which was located internal to the bone and did not invade the bone tissue. It does not have the appearance of biting damage. The overall difference in bone shape is intriguing, as it suggests a very asymmetrical snout region, but as the nasals and premaxillae are missing the full extent and nature of this asymmetry cannot be determined. In any case it seems probable that the underlying disturbance that caused the asymmetry and notch was already present early in the growth history of the animal.

On the internal surface of the skull roof, in the postorbital region, LDM G 81/807a-b shows two new contact surfaces that were not noticed in LDM G 81/775 (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008). The larger one is irregular in shape, with a striated surface, and extends to the margin of the skull roof where it is confluent with the postorbital suture; we interpret it as part of this suture, showing that a flange of the postorbital underlapped the skull roof. The smaller contact surface is sharply demarcated, oval, with a smoother surface, and extends anteromesially from the larger (Fig. 1c). It lies on the internal suture line between postfrontal and parietal. This must be a contact for the ascending process (columella cranii) of the epipterygoid, similar to that in embolomeres (Clack Reference Clack1987a) and some temnospondyls (Sawin Reference Sawin1941).

Another oblong indentation, slightly smaller, is present on the spiracular margin at a point straddling the supratemporal-tabular suture (Fig. 1c, ‘muscle attachment?’). This cannot represent a contact for a bone or cartilage, as comparative anatomy mandates that none should be present in that region; it is most probably a muscle attachment scar, the point of origin either for a muscle extending to the stapes or for musculature operating a valve in the spiracle.

The new information provided by the braincase of LDM G 81/807a-b centres on the basioccipital, exoccipitals, and middle and posterior parts of the otic capsule (Figs 1c–g, 3). The ethmosphenoid, basipterygoid processes, and prootic buttresses closely resemble those in LDM G 81/775 (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008, fig. 5). In posterior view, the entire braincase can be seen to be somewhat skewed to the right (Figs 1e, 3c–d), but it does not appear to be compressed either dorsoventrally or laterally.

The basioccipital-exoccipital complex, which cannot readily be demarcated into separate basioccipital and exoccipitals, is well ossified. The same applies to the posterior faces of the opisthotics, which are well ossified apart from a narrow unossified gap in the midline (Fig. 2c). By contrast, the lateral wall of the otic capsule is lightly ossified and the skeletal fenestra vestibuli is enormous with poorly defined anterior and dorsal margins. It seems likely that the otic capsule wall was partly cartilaginous in life, defining a smaller fenestra vestibuli.

The braincase is emphatically notochordal, with a wide tunnel passing through the basioccipital-exoccipital complex and no development at all of articular condyles either on the basioccipital or exoccipitals. The exoccipitals meet in the dorsal midline above the triangular foramen magnum. In posterior view the complex is tall, parallel-sided and relatively narrow, reminiscent of Eusthenopteron (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1980, fig. 86c) except that the foramen magnum and notochordal tunnel are confluent in Ventastega. It differs greatly from the occipital reconstruction of the braincase of Acanthostega provided by Clack (Reference Clack1998, fig. 8C), a point to which we return below. In lateral view, the occipital arch is tall, but short in the anteroposterior direction, again very reminiscent of the condition in Eusthenopteron including a similar slight anteroventral slope of the occipital plane. Spino-occipital nerve foramina and canals are preserved on both sides (Fig. 2). They show a surprising, but clearly natural (as the preservation is excellent), asymmetry with two foramina on the right side and three on the left. A tall but shallow notch for the vagus nerve (nerve X) is present on both sides in the anterior margin of the exoccipital, just below a blocky process with a concave posterior face that may represent a muscle attachment.

The ventral surface of the basioccipital is essentially flat and rather featureless. Posteriorly, its lateral margins are defined by slightly raised curving edges that demarcate a pair of faintly striated areas that may represent muscle or connective tissue attachments. Anteriorly it appears at first sight to reach the ventral cranial fissure, but in fact a separate midline element with a lenticular outline intervenes between the two. Evidence from Acanthostega (see next section) indicates that this is not a broken-off fragment of the basioccipital but is in fact an arcual plate (Fig. 1c, f, g).

In lateral view, the middle part of the basioccipital is low, forming a kind of ‘plank’ that floors the space for the notochord and the sacculi of the inner ears. The lateral margin of this region, which forms the lower margin of the fenestra vestibuli, has some interesting details that probably relate to the anatomy of the inner ear and its relationship with the stapes, but which cannot yet be fully interpreted. Posteriorly, the edge forms a sharp angle or corner with the anterior margin of the occipital arch, and this corner projects laterally as a distinct process. Moving anteriorly from the corner, the margin is initially concave in ventral view and then straight or faintly convex, ending in an anterior corner that marks the widest point of the basioccipital and the beginning of its suture with the prootic. From this point forwards the margin of the fenestra vestibuli (which is now formed by the prootic) takes an anterodorsal direction, while the basioccipital becomes narrower.

The otic capsule is less informative than the basioccipital-exoccipital complex due to its light ossification, but it does show some interesting and important features. Most importantly, the presence inferred by Ahlberg et al. (Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008, fig. 5a) of long, narrow, laterally open posttemporal fossae, is not supported. The lateral wall of the ophisthotic extends unbroken to the skull roof on both sides (Fig. 1c). The transverse posterior wall of each ophisthotic is faintly concave, with a posteriorly projecting peak (and unossified gap) in the middle (Fig. 2c, d). These concavities probably represent the posttemporal fossae. The posterodorsal part of the lateral wall of the otic capsule is developed into a short, ventrally trending process that extends past the level of the vagus nerve notch in the occipital arch (Fig. 2a). This process is also present in Acanthostega (Clack Reference Clack1998, fig. 8E). On the left side, a long semicircular ossification in an otherwise rather fragmented area appears to represent part of the wall of the external semicircular canal (Fig. 1c). However, its position is considerably more anterior than the anterior and posterior semicircular canal grooves of LDM G 81/775, which are certainly in life position as they are impressed into the internal surface of the skull roof (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008, fig. 5a). The external semicircular canal is thus probably somewhat displaced.

5. Description: Acanthostega

The external morphology of the otic region of Acanthostega was described by Clack (Reference Clack1994a, Reference Clack1994b, Reference Clack1998) on the basis of the mechanically prepared specimen UMZC T.1300d. This specimen has suffered substantial dorsoventral compression as well as dislocation of elements, and the posterior end is partly obscured by the impacted atlas intercentrum. Clack's attempt at reconstructing the original shape involved extensive graphic repositioning and retrodeformation of components on paper. Robinson's (Reference Robinson2006) tomographic analysis confirmed Clack's record of the external morphology, but also recovered important internal structures that impact the interpretation of the anatomy. These include a probable arcual plate, sutures between the prootics and basioccipital, and paired but medially connected chambers in front of the crista sellaris that may have accommodated retractor bulbi or rectus eye muscles (Fig. 3).

The probable arcual plate is a small, dorsally concave and ventrally convex, endoskeletal element that resembles a tiny intercentrum (Fig. 3g). As preserved it lies slightly to the left of the midline, a short distance posterior to the ventral cranial fissure (Fig. 3d), which is not a linear contact but manifests a distinct midline gap between basioccipital and basisphenoid (Fig. 3a). Given that the braincase is relatively undisturbed and is preserved in articulation with the atlas intercentrum, it seems highly unlikely that this is a displaced vertebral element, and the interpretation as an arcual plate is thus the only plausible one. It seems likely that the basioccipital and basisphenoid have been pushed together somewhat post-mortem, as suggested also by the atlas intercentrum pushing in under the basioccipital, and that this has popped the arcual plate out of its proper position between the basioccipital and basisphenoid. On this basis we infer that the lenticular element in Ventastega (see previous section) is also an arcual plate, preserved in its natural position (Fig. 1c, f, g).

The identification of sutures separating the ventral part of the prootics from the basioccipital, and thus showing that the anterior margin on the fenestra vestibuli is formed by the prootic rather than by the basioccipital as previously thought (Clack Reference Clack1994b, Reference Clack1998), brings Acanthostega into line with Ventastega, where these sutures are clearly visible (Fig. 1f, g, 3a, c). Another feature of importance, where Acanthostega and Ventastega differ, is the presence in Acanthostega of a pair of confluent rounded cavities in the basisphenoid, immediately anterodorsal to the basipterygoid processes, bounded posterodorsally by the crista sellaris (Fig. 3h). Together these cavities and the connection between them form a complete transverse passage through the braincase (‘interorbital foramen’ of Clack Reference Clack1998). Clack interpreted this space as transmitting not only the interorbital (pituitary) vein, which is probably correct, but also nerves II and V, which seems less likely. The forward-facing paired cavities may have housed eye muscles, but Clack (Reference Clack1998) hesitated to make a precise identification or address the question of homology with the retractor pit of reptiles. Ventastega, by contrast, has a solid braincase wall in this region, pierced by individual small foramina, and lacks both the interorbital foramen and the associated cavities (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Blom and Zupins2008, fig. 5b).

New reconstructions of the braincases of Ventastega and Acanthostega are presented in Fig. 4, together with reconstructions of Eusthenopteron and Archeria intended for comparison.

6. Discussion

The interplay between the new data from Ventastega and Acanthostega aids in the interpretation of both taxa and substantially reinforces our understanding of these early tetrapod braincases (Fig. 4). The process of comparison is helped by the fact that the two are reasonably similar in general proportions. This is particularly evident in lateral view, where the fully three-dimensional braincase of Ventastega closely resembles Clack's (Reference Clack1994b, Reference Clack1998) reconstruction of Acanthostega, indicating that the graphic retrodeformation of the latter was quite successful. The comparison also establishes a shared braincase ‘gestalt’ with an anteroposteriorly short but tall occipital arch region, large notochordal tunnel, no occipital condyles, flat basioccipital and large fenestra vestibuli. The dorsal outlines of the two braincases are already known to be broadly similar, with otic capsules filling almost the whole underside of the skull table. They are in these respects very different from the braincases of Ichthyostega and Parmastega (Clack et al. Reference Clack, Ahlberg, Finney, Dominguez Alonso, Robinson and Ketcham2003; Beznosov et al. Reference Beznosov, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Ruta and Ahlberg2019), which have substantially narrower otic capsules, and, in the case of Ichthyostega, a long occipital arch region and a small fenestra vestibuli.

When Ventastega and Acanthostega are compared with Eusthenopteron, it is readily apparent that the large fenestra vestibuli of the tetrapods corresponds substantially to the vestibular fontanelle of the fish. The posteroventral part is essentially identical, but the tetrapod fenestra vestibuli appears to extend further anteriorly, and in particular dorsally. This probably relates to the loss of the lateral commissure and the transference of the foot of the hyomandibula/stapes from the lateral commissure to the fenestra vestibuli. Unfortunately, the stapes of Ventastega remains unknown, and in Acanthostega the relationship between the stapedial footplate and fenestra vestibuli is not known in detail. However, Ichthyostega has a bipartite stapedial footplate where the ventral part articulates with the basioccipital and the dorsal part inserts into the fenestra vestibuli (Clack et al. Reference Clack, Ahlberg, Finney, Dominguez Alonso, Robinson and Ketcham2003). In extant tetrapods the stapedial footplate contains a mesodermal component, whereas the rest of the stapes consists of hyoid arch neural crest (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Ohazama, Sharpe and Tucker2012), probably indicating that the stapes has absorbed part of the otic capsule wall.

A noteworthy shared characteristic of the braincases of Ventastega and Acanthostega, and as far as we know also of Ichthyostega, is the delicate construction of the notochordal basicranium. The contrast with later tetrapods such as the Early Permian embolomere Archeria, a more crownward member of the tetrapod stem group with a strongly reduced cranial notochord (Pardo Reference Pardo2023), is striking. Ventastega, Acanthostega and Archeria all have a basioccipital ossification separated from the basisphenoid by a transverse fissure (with or without an intervening arcual plate; see below). However, in Archeria the basioccipital is a robust ossification, securely bonded to the basisphenoid by a posterior extension of the parasphenoid which bridges the fissure, whereas in Ventastega and Acanthostega the basioccipital is a thin-walled ‘cradle’ for the notochord and the fissure is exposed (Fig. 4). If the bones are considered in isolation, the braincases of the Devonian tetrapods thus appear much weaker than those of Archeria. However, this is probably not a realistic comparison, because a fragile basicranium would be liable to potentially fatal injury from wrenching movements during prey capture. It is difficult to imagine how or why such a structure would evolve. The real significance of the construction must be that the cranial notochord retained an important structural role and provided much of the strength of the basicranium in the Devonian forms. When the notochord was reduced in post-Devonian tetrapods, the basioccipital-basisphenoid axis was greatly strengthened as a functional replacement.

Given the many similarities between Ventastega and Acanthostega, it is surprising to find that the occipital view of the braincase of Ventastega is substantially different from that reconstructed for Acanthostega by Clack (Reference Clack1998, fig. 8c). In the latter the occipital arches form an almost circular curve, defining a wide notochordal tunnel, and are widely separated dorsally; there is no distinct foramen magnum at all, though the entire opening is labelled ‘for mag’. It seems likely that some of these differences are due to the difficulty of accurately retrodeforming distorted bones on paper. The specimen drawings of UMZC T.1300d (Clack Reference Clack1998, fig. 1) show the exoccipitals approaching closer to the dorsal midline. Nevertheless, they are separated by a distinct gap, whereas in Ventastega they suture together. The occiputs of Ventastega and Acanthostega are evidently different, with Ventastega closer to the primitive tetrapodomorph fish condition represented by taxa such as Eusthenopteron and Gogonasus (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1980; Long et al. Reference Long, Barwick and Campbell1997), even though the condition in Acanthostega is not fully understood (Fig. 4). Moreover, Ventastega has a co-ossified basioccipital-exoccipital complex like Eusthenopteron, whereas Acanthostega, like post-Devonian tetrapods, has sutures demarcating the exoccipitals from the basioccipital.

Differences that may be phylogenetically informative are also seen in the hypophyseal region (Fig. 4). An interorbital foramen comparable to that of Acanthostega is present in many post-Devonian tetrapods, notably in Whatcheeria (Bolt & Lombard Reference Bolt and Lombard2019), embolomeres (Clack & Holmes Reference Clack and Holmes1988; Pardo Reference Pardo2023), baphetids (Beaumont Reference Beaumont1977), colosteids (Smithson Reference Smithson1982) and some temnospondyls such as Dendrerpeton (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Ahlberg and Koentges2005). Conversely, Ventastega has a solid braincase wall pierced by small foramina, which is essentially the same condition as in Eusthenopteron, Gogonasus, Panderichthys and Tiktaalik (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1980; Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack and Luks̆evic̆s1996; Long et al. Reference Long, Barwick and Campbell1997; Downs et al. Reference Downs, Daeschler, Jenkins and Shubin2008). This is presumably primitive for tetrapods. Apparently linked to this character is the position of the basipterygoid process, which is high in Eusthenopteron, slightly lower in Ventastega, and lower still in Acanthostega and Archeria (Fig. 4). The lowering of the process seems to create the space required for a transverse interorbital foramen. Together, the character suites of the occipital and hypophyseal regions strongly suggest that Ventastega occupies a less crownward position in the tetrapod stem group than Acanthostega.

By far the most unexpected outcome of this project has been the discovery of an arcual plate in both Ventastega and Acanthostega. Its presence suggests a somewhat different mechanism for the loss of the basicranial fenestra than previously envisaged (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Clack and Luks̆evic̆s1996): rather than consolidating the entire parachordal region as a one-step transformation to a unitary basioccipital, the fenestra may have been lost by a proportional shortening of the prootic region, resulting in the anterior margin of the basioccipital moving closer to the posterior margin of the basisphenoid until the narrowing gap was entirely filled by the arcual plate. However, there is at present no evidence of an arcual plate in Ichthyostega or in any post-Devonian tetrapod.

The new skull roof of Ventastega also adds important data to our understanding of this taxon, because of its fully resolved suture pattern. Ventastega is an odd outlier as the only known Devonian tetrapod to possess an intertemporal bone; in Parmastega, Acanthostega and Ichthyostega the intertemporal is absent and the postorbital contacts the parietal (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1996; Clack Reference Clack2002; Beznosov et al. Reference Beznosov, Clack, Luks̆evic̆s, Ruta and Ahlberg2019). The intertemporal bone is a primitive sarcopterygian character, present also in tetrapodomorph fishes such as Gogonasus and Eustenopteron (Jarvik Reference Jarvik1980; Long et al. Reference Long, Barwick and Campbell1997), but higher in the tree its distribution becomes quite peculiar and its phylogenetic significance uncertain. It is present in Panderichthys (Vorobyeva Reference Vorobyeva1977) but absent in Elpistostege (Schultze & Arsenault Reference Schultze and Arsenault1985); the condition in Tiktaalik is uncertain (Daeschler et al. Reference Daeschler, Shubin and Jenkins2006). Among post-Devonian tetrapods it is present in Pederpes (Clack & Finney Reference Clack and Finney2005), Whatcheeria (Lombard & Bolt Reference Lombard and Bolt1995), Crassigyrinus (Panchen Reference Panchen1985), embolomeres and other anthracosaurs (Panchen Reference Panchen1972; Holmes Reference Holmes1984; Clack Reference Clack1987b; Porro et al. Reference Porro, Martin-Silverstone and Rayfield2024), some deep-branching temnospondyls such as Balanerpeton and Capetus (Milner & Sequeira Reference Milner and Sequeira1993; Sequeira & Milner Reference Sequeira and Milner1993), and seymouriamorphs (Klembara Reference Klembara1997), but not in aïstopods (Boyd Reference Boyd1982; Milner Reference Milner1993; Carroll Reference Carroll1998; Anderson Reference Anderson2003; Pardo et al. Reference Pardo, Szostakiwskyj, Ahlberg and Anderson2017), nectrideans, microsaurs, lysorophids or crown amniotes (Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Bossy, Milner, Andrews, Wellstead and Wellnhofer1998; Clack Reference Clack2012). The post-Devonian pattern is most readily interpreted as primitive presence of the intertemporal followed by repeated loss, especially as its absence among these tetrapods is often associated with overall simplification of the skull bone pattern. However, whether this presence condition is homologous with the (essentially indistinguishable) one in Ventastega, Panderichthys, and less crownward tetrapodomorphs – and what that means for the phylogenetic position of Acanthostega, Ichthyostega, Parmastega and Elpistostege, which lack this bone – is impossible to say at present.

All in all, the new findings from Ventastega and Acanthostega confirm the importance of the otoccipital and orbitotemporal regions of the braincase, and their associated skull roof, as major sources of functionally and phylogenetically informative data for the earliest tetrapods. Several new tetrapod braincases from the latest Famennian of Greenland, representing previously unknown taxa, are currently under description and will contribute to the further expansion of this important but previously meagre data set. It is already apparent that some characters, notably the intertemporal, have incongruent distributions that point to phylogenetic complexity with high levels of homoplasy. The phylogeny of Devonian tetrapods is unlikely to be a straightforward Hennigian comb showing step-by-step acquisition of the crown tetrapod morphotype. Data from the braincase and skull roof will play a central part in untangling, as far as possible, this messy but fascinating pattern.

7. Acknowledgements

We dedicate this paper to Tim Smithson, in recognition of his ground-breaking contributions to research on the morphology, diversity and evolution of early tetrapods. This paper forms a contribution to ERC Advanced Grant project ||ERC-2020-ADG 10101963 ‘Tetrapod Origin’, awarded to P.E.A. E.L. acknowledges the support of the University of Latvia, grant ‘Climate changes and sustainable use of natural resources’, and the Latvian Council of Science, grant no. lzp-2018/2-0231 ‘Influence of tidal regime and climate on the Middle-Late Devonian biota in the epeiric Baltic palaeobasin’. L.B.P was funded by NERC (Natural Environment Research Council) Standard Grant NE/P013090/1 (‘Skull evolution and the terrestrialization and radiation of tetrapods’) to E. J. Rayfield (PI) and L.B.P. (RCI), and a Marie Curie International Incoming Research Fellowship (‘Tetrapods Rising’, 303161) to L.B.P. J.R's PhD was funded by a BBSRC grant awarded to P.E.A. and Georgy Koentges; access to specimen UMZC T.1300d was granted by the late J. A. Clack (University of Cambridge). We thank T. Davies, L. Martin-Silverstone and B. Moon (University of Bristol) for their help in μCT-scanning fossils of Ventastega. Jurijs Ješkins (University of Latvia) provided technical support processing data from μCT scanner.

8. Data availability

The scan data sets of LDM G 81/807a-b are deposited at https://www.morphosource.org/concern/media/000636412?locale=en, https://www.morphosource.org/concern/media/000636407?locale=en. It has not been possible to retrieve the scan data for UMZC T.1300d, but the specimen itself is deposited at the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge.

9. Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.