Introduction

In 2019 the centre‐right Rutte III coalition lost its majority in both the Senate and the House. This meant that after more than a year of majority government, the Netherlands effectively returned to minority government. The government would need to negotiate policy solutions within its own ranks as well as with opposition parties. The Cabinet managed to build ad‐hoc coalitions for pension reforms and environmental measures.

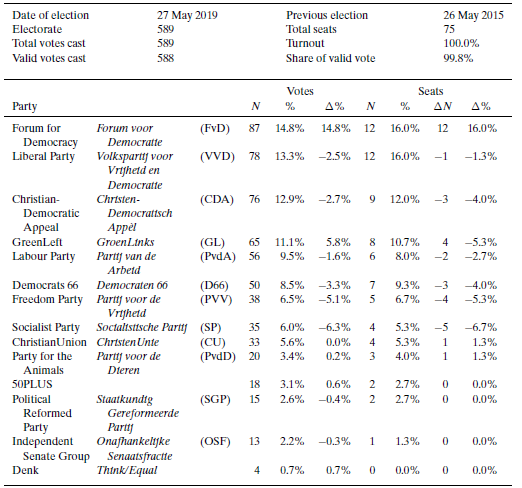

Table 1. Elections to the Upper House of the Dutch Parliament (Eerste Kamer der Staten‐Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2019

Source: Kiesraad (2019).

Election report

Senate elections

On 20 March, the Netherlands held elections for the provincial councils. The election campaign was suspended two days before the election after an Islamic terror attack on a tram in Utrecht cost the lives of four people. For the first time electors were also elected for the three ‘special municipalities’ of the Netherlands in the Caribbean: Bonaire, St. Eustatius and Saba. On 27 May these newly elected provincial councillors and electors elected the First Chamber (Eerste Kamer) of the Netherlands. The provincial elections already indicated major shifts: the largest party in the provincial councils was Forum for Democracy/Forum voor Democratie (FvD), a radical right‐wing populist party which won its first two seats in the Second Chamber just two years earlier. The other victor was the GreenLeft/GroenLinks (GL). The Rutte III coalition of the Liberal Party/Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD), Christian‐Democratic Appeal/Christen‐Democratisch Appèl (CDA), Democrats 66/Democraten 66 (D66) and ChristianUnion/ChristenUnie (CU), which already had lost its majority one month before (see below), did not regain its majority in this new Senate.

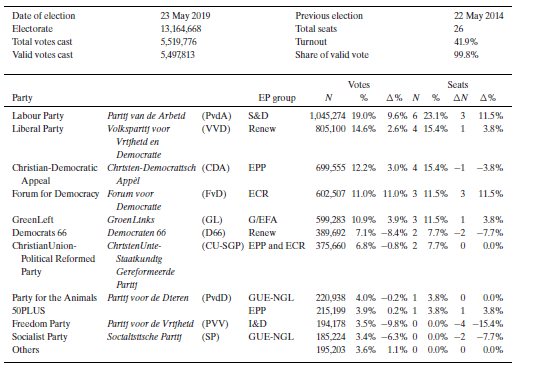

Table 2. Elections to the European Parliament (Europees Parlement) in the Netherlands in 2019

Source: Kiesraad (2019).

European elections

On 23 May, the Netherlands elected its delegation to the European Parliament (EP). Two European Spitzenkandidaten were running in the elections: the first Vice‐President of the European Commission, Frans Timmermans, who was Spitzenkandidat for the Party of European Socialists, ran for the Labour Party/Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA). Bas Eickhout, MEP, who was co‐Spitzenkandidat for the European Green Party, together with the German Ska Keller, ran for the GreenLeft. The candidature of Timmermans, who was seen as serious contender for the Presidency of the European Commission, garnered quite some media attention.

Timmermans’ Labour Party won the election for the Dutch MEPs. The party doubled its vote share and the number of seats compared with 2014 (from 9 to 19 per cent). A second major winner of the elections was the FvD, which won 11 per cent of the vote (and three seats). The Liberal Party and the GreenLeft were also able to increase their support and the pensioners’ party 50PLUS won its first seat. The Freedom Party/Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) and the Socialist Party/Socialistische Partij (SP) lost all their EP seats in the election. The D66 also lost a substantive part of its support.

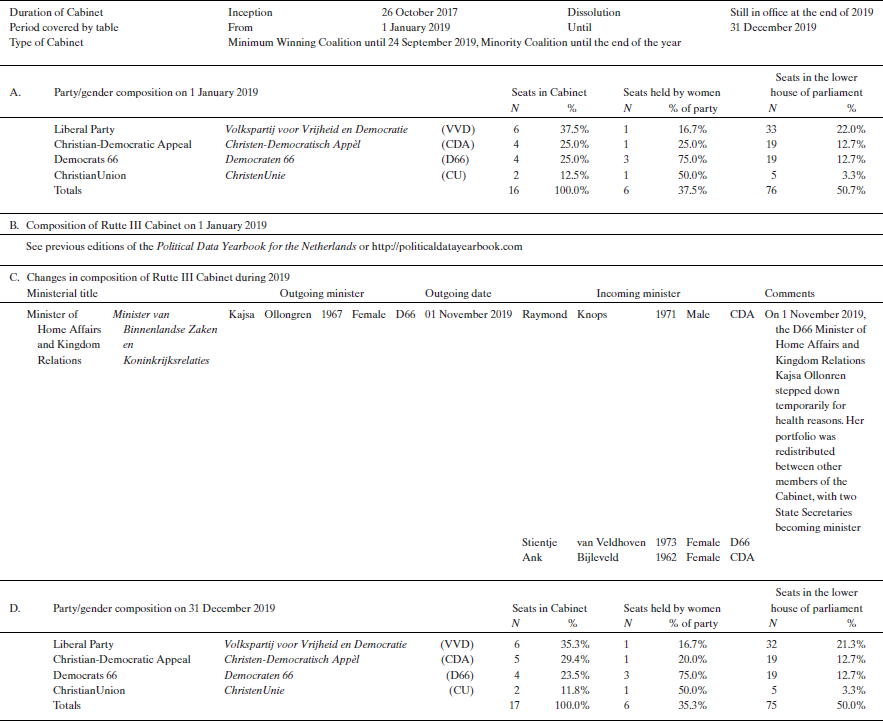

Cabinet report

The year 2019 saw a number of Cabinet officials leaving and one new Cabinet official coming in. On 21 May, Mark Harbers (VVD), State Secretary for Migration, stepped down because he had given incomplete information to the Second Chamber about the crimes committed by asylum‐seekers. On 11 June 11, Ankie Broekers‐Knol (VVD), former Speaker of the Senate, took the office.

On 1 November, Kajsa Ollongren (D66), Minister of Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations, temporarily stepped down for health reasons. Her portfolio was redistributed between other members of the Cabinet: State Secretary for Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations Raymond Knops (CDA), became minister at this department and took over most of Ollongren's portfolio. State Secretary for Infrastructure and the Environment, Stientje van Veldhoven (D66), became minister without portfolio for the Environment and Housing, retaining her portfolio at the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment and adding the Housing and Spatial Planning portfolios from Ollongren. Minister of Defense Ank Bijleveld (CDA) also became minister without portfolio for the General Intelligence and Security Service in addition to her responsibilities at Defense. Minister of Social Affairs and Employment Wouter Koolmees (D66) took over Ollongren's responsibilities as the D66 Vice‐Prime Minister.

On 18 December, State Secretary for Finance Menno Snel (D66) stepped down after increasing criticism from Parliament on how the tax service dealt with suspected cases of fraud with allowances. His successor would not be appointed in 2019.

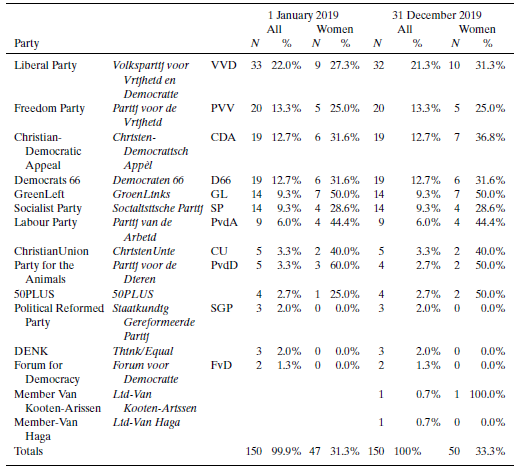

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Dutch Parliament (Tweede Kamer der Staten‐Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2019

Source: PDC/MI (2020).

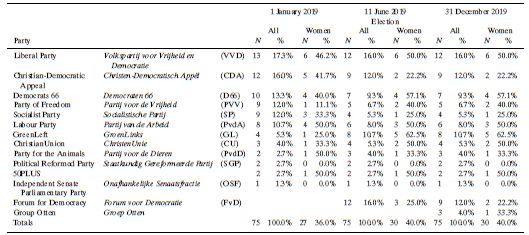

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the upper house of the Dutch Parliament (Eerste Kamer der Staten‐Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2019

Source: PDC/MI (2020).

Parliament report

In both the House and the Senate, internal conflicts led to the formation of new party groups. This led the Cabinet to lose its majority first in the Senate and then in the House. On 26 April 2019, Anne‐Wil Duthler, Senator for the Liberal Party, was removed from the Liberal Senate group over a perceived conflict of interests. She was criticized for using her Senate position to better her business interests. This meant that a month before the election of a new Senate, the coalition lost its majority in the Senate.

On 16 July, Femke Merel van Kooten‐Arissen, MP for the Party for the Animals/Partij voor de Dieren (PvdD), left this parliamentary party group to continue as an independent MP after a conflict over the party's course. Van Kooten‐Arissen wanted the party to focus on other themes than just animal welfare.

On 28 July, Henk Otten, the newly elected Senator for the FvD, was removed from the FvD Senate group over controversies surrounding his handling of the party finances during his stint as treasurer of the party board. On 18 August, two other FvD Senators, Dorien Rookmaker and Jeroen de Vries, joined his group. They had been dissatisfied with the course FvD leader Thierry Baudet and his ‘admiration of the extreme right’ (Megens Reference Megens2019). On 18 August, the group registered as a new party, Group Otten/Groep Otten (GO), which aimed to participate in the 2021 parliamentary elections.

On 24 September, Wybren van Haga, MP for the Liberal Party, was removed for the Liberal group over controversies surrounding his real estate business. He continued as an independent MP. As the government only had one seat majority in the House, his split from the Liberal group made the Rutte III coalition government a minority coalition. Van Haga, however, continued to vote in line with the VVD.

Political party report

Two political party parties changed their party leader: CDA leader Sybrand Buma, who was elected leader in 2012, stepped down as party leader on 29 May 2019. He became Mayor of Leeuwarden. He was succeeded as party group chair by Pieter Heerma, who had been his fellow negotiator during the negotiations for the Rutte III coalition.

Party for the Animals leader Marianne Thieme stepped down as party leader on 8 October 2019. She had led the party since its foundation in 2002. Thieme continued the international work for her party. She was succeeded as party group chair by Esther Ouwehand, who had been her fellow MP since 2006.

Institutional change report

A considerable number of changes to the Dutch political system were debated in 2019, following the publication of two reports on the subject in 2018.

In January, the government responded to the report of the evaluation committee about party finance law. In their response, the government adopted the advice to ban donations from persons from countries outside the European Union (EU), as well as the mandatory disclosure of all donations from other EU member states. In case of donations from legal entities, the names of natural persons who were involved had to be made transparent. In September, the Second Chamber also decided to increase the subsidies to national parties by €9 million per year until 2025, and subsequently with €5 million annually.

In May, the Senate unanimously adopted a Code of Conduct on Integrity, which, among others, set rules regarding transparency concerning relations with lobbyists, the acceptance of gifts and the additional functions that senators may hold.

In June, the government published an extensive response to the state committee's advisory report on the parliamentary system, which had been presented in December 2018. In order to strengthen the bond between voters and the elected representatives, the Cabinet wanted to give greater weight to the preference vote. To counter parliamentary fragmentation, the government proposed to increase the admission requirements for new parties. The Cabinet also adopted the advice to draw up a Political Parties Law, which should include party finance law, the possibility to ban parties, the regulation of the internal party organization and microtargeting by political parties. The Cabinet postponed decisions about a binding corrective referendum and the right for the First Chamber to send back legislation to the Second Chamber. It rejected the proposals for the direct election of the formateur of a new government and the creation of a constitutional court with the competence of judicial review. On its own initiative the Cabinet proposed to alter the way the Senate was elected, by expanding its legislative term from four to six years, with half the Senate being elected every three years. The reform had to reduce the chance of divergent political majorities in the Lower and Upper Houses due to high levels of electoral volatility, but would make it more difficult for small parties to enter the Senate.

Issues in national politics

The coalition had to deal with several issues during 2019. As the Cabinet lost its majority in the Senate, the coalition also had to negotiate with opposition parties for support. In many of the comprises struck, the Liberal Party of Prime Minister Rutte in particular ended up with the short end of the stick. Environmental issues were dominant in the Netherlands for most of the year, but cultural and economic issues also had to be dealt with.

In January, the coalition parties came to an agreement about how to deal with several asylum‐seekers who had come to Netherlands as minors and had stayed for a long period but whose asylum request was not granted. This specific group of 600 children had fallen between the ‘cracks’ of earlier amnesty measures. They would get a residency permit on humanitarian grounds, but the ability to grant such permits to asylum‐seekers would be taken away from the State Secretary for Migration and be given to the Immigration and Naturalization Service. The Liberal Party was forced to accept this solution when the CDA moved to the position the D66 and CU already held.

At the end of 2018, a climate agreement between the government and social partners was negotiated (Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2019). The coalition parties negotiated between themselves which elements of the agreements they would follow, leading to mutual frictions. These negotiations coincided with the campaign for the provincial elections. In March, a week before the provincial elections, the Cabinet announced a policy package that would incorporate most of the climate agreement. The Cabinet deviated from the agreement in introducing a CO2 tax for companies and lower energy costs for citizens. The CDA and VVD had opposed this measure during the coalition negotiations. In June, the Cabinet included plans for road pricing system (‘rekeningrijden’) in the final version of the climate agreement. This had been opposed by the Liberal Party and CDA in the past decade. Meanwhile a broadly supported Climate Law that set targets for climate reduction, passed the Senate in May. This bill that was initiated by the leaders of the Labour Party and GreenLeft, now both opposition parties, had already been accepted by the house in 2018 (for more, see Otjes and Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2019). In December, the Supreme Court confirmed the decision by a lower court that the government had to keep to its commitment to reduce CO2 emissions by 25 per cent in 2020 (Otjes and Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2019). This meant that despite the agreement over climate policy in the long term, the coalition would need to work on short‐term solutions in the next year.

In the spring the Cabinet negotiated in parallel with the trade unions and employers as well as the left‐wing opposition parties SP, Labour Party and GL about pension reform. The agreement, which was presented in June, primarily concerned the obligatory private employee pensions. The government, social partners, PvdA and GL agreed on a package that would make less strict requirements on pension funds. In order to court the trade unions and the left‐wing parties, the government also fix the government pension age at 67, allowed employees with lower paying jobs to use their private employee pensions earlier and introduced a proposal for an obligatory disability insurance for self‐employed people.

Another environmental issue loomed large in the fall. In May, the Council of State, the highest administrative court, rejected the existing government policy concerning the compensation nitrogen emissions by new construction projects in vicinity of nature reserves. This meant no new building projects would be possible in much of the country unless the government would reduce the emission of nitrogen. The proposal by the D66 to halve the number of livestock in the Netherlands to decrease nitrogen emissions led to massive protests by farmers in the autumn. The coalition negotiated a package to deal with the issue. This included changing cattle feed, consolidating nature reserves, speeding the processing of build permits and reducing the speed limit on roads from 130 to 100 km/hr during the daytime. The Liberal Party had claimed increasing the speed limit as an important liberal accomplishment. In December, the coalition parties found an ad‐hoc majority with support of the Independent Senate Group (Onafhankelijke Senaatsfractie, OSF), which represents provincial parties, the pensioners’ party 50PLUS, the small Christian Political Reformed Party/Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (SGP) and Group‐Otten.

Where in the last years the lack of a majority in the Senate necessitated negotiations about the budget between the coalition and opposition parties, this was not necessary in 2019: Jesse Klaver, leader of the GreenLeft, announced that his party would unconditionally support all government budgets. He did not want to vote against the budget of the Cabinet as it meant an improvement on most issues his party prioritized.