Introduction

International nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) have become important societal actors. They provide public goods and services in regions where state agencies lack capacities (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017) and shape international policy outcomes across a wide spectrum of political issues (Mitchell & Schmitz, Reference Mitchell, Schmitz and Bruno-van Vijfeijken2020; Prakash & Gugerty, Reference Prakash and Gugerty2010). With their accentuated influence, the implementation of stringent accountability practices has become crucial to maintain INGOs’ legitimacy as private organizations that represent the public’s interest. In the context of a fairly liberal international funding market, INGOs, however, are criticized for prioritizing the accountability demands of donors and regulatory bodies and for focusing on accountability for financial performance and legal compliance (Crack, Reference Crack2013b; Hielscher et al., Reference Hielscher, Winkin, Crack and Pies2017; O’Dwyer & Boomsma, Reference O’Dwyer and Boomsma2015).

In response to these critiques, nonprofit management research has advanced important ideas around a more comprehensive approach to INGO accountability. Comprehensive INGO accountability addresses a wider set of stakeholders, in particular, those that hold little negotiation power, such as beneficiaries. It further incorporates accountability for the INGO’s primary goal, that is, their mission achievement (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Crack, Reference Crack2013b; Lecy et al., Reference Lecy, Schmitz and Swedlund2012). There is emerging empirical evidence linking comprehensive accountability to increased organizational performance. For instance, comprehensive accountability practices that are based on closer relationships and dialogue with beneficiaries are found to be central to organizational learning processes (Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Raggo and Bruno-van Vijfeijken2012) and can increase the effectiveness of aid interventions (Jacobs & Wilford, Reference Jacobs and Wilford2010; van Zyl & Claeyé, Reference van Zyl and Claeyé2019). This suggest that there is a strategic managerial argument for INGOs to implement comprehensive accountability. There is yet, however, a lack of empirical evidence for such an argument. Moreover, critical studies also show that the implementation of dialogue and partnership-oriented accountability is challenging when INGOs lack the resources and organizational commitment to effectively engage with their beneficiaries (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019; O’Dwyer & Unerman, Reference O’Dwyer and Unerman2007). This study aims to strengthen the empirical evidence for the strategic managerial argument for INGOs to adopt and implement comprehensive accountability. It asks: “How does comprehensive INGO accountability strengthen perceived program effectiveness?” To answer this question, this study first builds on nonprofit management literature to detect different accountability logics. Second, a theoretical framework is developed including drivers of accountability logics and program effectiveness as overall goal. Finally, the framework is empirically tested.

Recent studies take an institutional logics perspective to describe the accountability relationships (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2019; Coule, Reference Coule2015; Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019; Weinryb, Reference Weinryb2020). The perspective suggests that INGOs and different stakeholders each have their own institutional logics that affect how accountability is structured, communicated and understood (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2019). Extant frameworks focus on accountability logics of individual relationships between the INGO and its stakeholders and reveal the challenges arising from conflicting accountability logics (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2019; Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019; McMullin & Skelcher, Reference McMullin and Skelcher2018). This study builds on the idea that INGO accountability follows multiple logics. Instead of defining accountability logics tied to the institutional logics of individual stakeholders, however, it identifies three accountability meta-logics that describe the different ends to which INGOs practice accountability. These meta-logics refer to as resource logic, outcome assessment logic, and discursive logic. The theoretical framework developed in this study consists of the drivers of comprehensive accountability, the meta-logics, and their impact on perceived program effectiveness as ultimate goal to justify INGO accountability. The analysis is conducted based on a unique data set from an international survey among 201 INGO leaders from 21 countries.

The article is structured as follows: It presents the concept of institutional logics, the literature on INGO accountability, and how these concepts relate in order to derive hypotheses. It then elaborates on the methodological approach before presenting and discussing the results. The final section concludes with limitations and implications for future research.

Integrating Institutional Logics with INGO Accountability

The concept of institutional logics has emerged as part of institutional theory. Institutional theory generally seeks to understand the behavior of organizations within their institutional environment. Institutional logics define the material practices through, and reasons for, which organizations and their stakeholders interact (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2013). The assumption is that organizational decisions are mainly guided by what is deemed legitimate according to their individual institutional logics (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio2008). This relativizes the assumption that the market logic and inherent striving for financial efficiency are the sole driver of organizational behavior (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio2008) and allows defining other reasons for which organizations take certain organizational decisions. The institutional logics perspective has become a viable theoretical lens for researchers analyzing nonprofit organizations’ accountability relationships with different stakeholders, in particular, with those that are not characterized by an efficient market transaction, including the relationship with their beneficiaries (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2019; Coule, Reference Coule2015; Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019; Weinryb, Reference Weinryb2020).

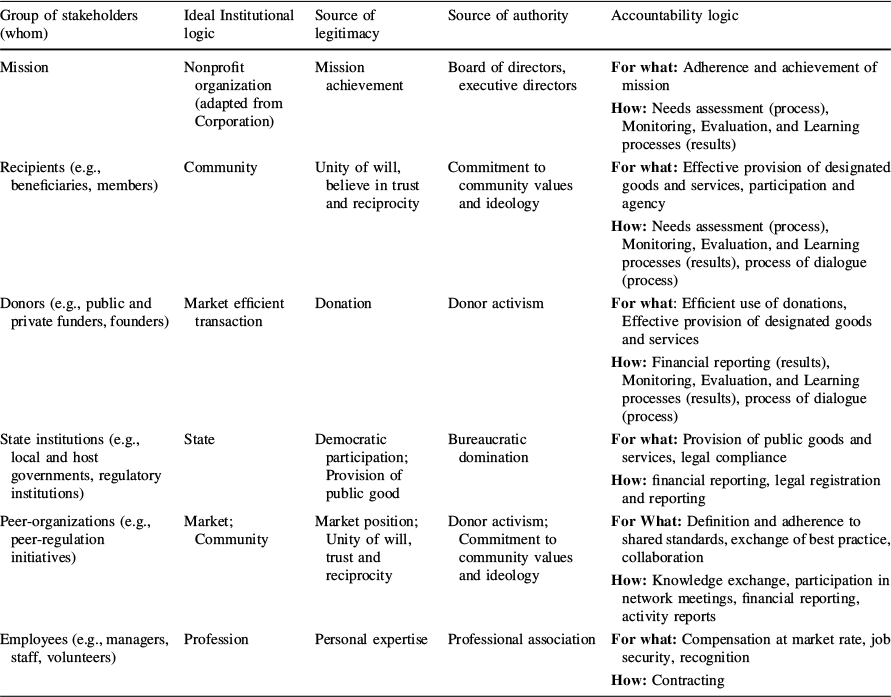

INGOs operate in a multi-stakeholder context, that is, they work with a broad variety of stakeholders including beneficiaries, public and private donors, governmental institutions, employees and volunteers, and peer-organizations. These stakeholders all come with their own institutional logics which define their expectations regarding the work of INGO. For instance, while funders may seek control to ensure the efficient management of their funds, the creation of effective programs and service delivery is more relevant for beneficiaries. Accordingly, these stakeholders have their respective accountability logic, that is, a logic that describe the reason for, and defines the practice through, which the INGO should deliver accountability. An in-depth elaboration on the individual stakeholder accountability logics can be found in the supplementary material.

These individual accountability logics need to be adequately addressed for the INGO to remain a legitimate societal actor. Scholars suggest that following a multiple logics approach creates space for broad accountability to multiple stakeholders (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2019; Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Coule, Reference Coule2015; Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019; McMullin & Skelcher, Reference McMullin and Skelcher2018). Recent studies describe a multitude of accountability logics. For instance, logics that address donors include regular financial reporting and disclosure, which serve to strengthen trust in the organization and increase the chance for future financial support (Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019; Weinryb, Reference Weinryb2020). Similarly, accountability directed at public sector organizations is based on compliance with legal requirements (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2019). Accountability toward peers is based on mechanisms that strengthen mutual learning to serve the logic of collective action (Gugerty, Reference Gugerty2008). Internal evaluations are common practices in which staff report their own progress toward internal goals and missions (Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2003). Table 1 provides an overview for the individual stakeholders’ institutional logics and the resulting accountability logics.

Table 1 Overview individual stakeholder accountability logics

Group of stakeholders (whom) |

Ideal Institutional logic |

Source of legitimacy |

Source of authority |

Accountability logic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mission |

Nonprofit organization (adapted from Corporation) |

Mission achievement |

Board of directors, executive directors |

For what: Adherence and achievement of mission How: Needs assessment (process), Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning processes (results) |

Recipients (e.g., beneficiaries, members) |

Community |

Unity of will, believe in trust and reciprocity |

Commitment to community values and ideology |

For what: Effective provision of designated goods and services, participation and agency How: Needs assessment (process), Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning processes (results), process of dialogue (process) |

Donors (e.g., public and private funders, founders) |

Market efficient transaction |

Donation |

Donor activism |

For what: Efficient use of donations, Effective provision of designated goods and services How: Financial reporting (results), Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning processes (results), process of dialogue (process) |

State institutions (e.g., local and host governments, regulatory institutions) |

State |

Democratic participation; Provision of public good |

Bureaucratic domination |

For what: Provision of public goods and services, legal compliance How: financial reporting, legal registration and reporting |

Peer-organizations (e.g., peer-regulation initiatives) |

Market; Community |

Market position; Unity of will, trust and reciprocity |

Donor activism; Commitment to community values and ideology |

For What: Definition and adherence to shared standards, exchange of best practice, collaboration How: Knowledge exchange, participation in network meetings, financial reporting, activity reports |

Employees (e.g., managers, staff, volunteers) |

Profession |

Personal expertise |

Professional association |

For what: Compensation at market rate, job security, recognition How: Contracting |

Challenges arise when the organizational objective for which accountability is practiced conflict. Ebrahim (Reference Ebrahim2005) argues that accountability mechanisms that emphasize short-term operational behavior run the risk of promoting activities that are so focused on immediate outputs and efficiency that they lose sight of long-range goals concerning organizational effectiveness. Similarly, Koppell (Reference Koppell2005) illustrates how conflicting accountability expectations contribute to organizational dysfunction. Organizations that try to respond to too many conflicting accountability expectations often satisfy none. He coins the term multiple accountability disorder (MAD) and suggests weighting which expectations are the most relevant ones to avoid MAD. In contrast to the generally positive perspective of being accountable to a wider set of stakeholders, these studies show the potentially harmful effects of accountability. Extant research has primarily focused on understanding the logics and dynamics within specific accountability relationships that are tied to the institutional logics of the individual stakeholders. As a result, insights on how to manage and overcome conflicting accountability logics remain understudied.

Addressing these short-comings, researchers broaden the concept of accountability to not only be a means of control, but to further involve the ideas of negotiation and discourse as central determinants of organizational performance (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Coule, Reference Coule2015). The institutional logics perspective is not only concerned with the material practices and reasons for which organizations interact, but further seeks to understand the drivers of specific logics as well as their implications for organizational performance (Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014). This study adds to the literature by establishing a conceptual framework that defines accountability meta-logics that describe different ends to which INGOs practice accountability. Instead of focusing on the individual institutional logics of stakeholders, the meta-logics describe ends and mechanisms that allow integrating the different perspectives stemming from individual institutional logics. It refocuses on how accountability practice can contribute to the INGO’s mission achievement—its initial aim. The meta-logics, in the following, are argued to allow overcoming conflicts arising when conceptualizing accountability logics tied to individual stakeholders. Further, the framework incorporates drivers of different INGO accountability meta-logics and links them to organizational performance. Linking accountability to organizational performance allows providing a strategic managerial argument for a comprehensive approach to INGO accountability.

Toward a Framework of Comprehensive INGO Accountability: Three Meta-Logics

By reviewing the current literature on accountability in nonprofits in general, and the literature on INGO accountability more specifically, three INGO accountability meta-logics can be identified. These INGO accountability meta-logics can be linked to organizational performance in different ways and materialize in different practices. They each define the stakeholders that are addressed, the practice employed and the ends to which INGOs practice accountability.

The resource logic defines the most common and widely used conceptualization of INGO accountability and is considered part of good governance (Crack, Reference Crack2013a). It describes the idea that accountability is primarily owed to stakeholders that provide financial resources, that is, to the donors of INGOs. From the donors’ side, accountability serves as a means of control and risk mitigation (Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019). From the INGO’s side, this logic implies that accountability is a means to satisfy donors’ demands for the efficient use of donated resources and good financial performance. This materializes in the form of adherence to reporting and disclosure standards (Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2003). The resource logic is primarily driven by market pressure for funding; organizations who signal good financial performance and compliance are perceived as more trustworthy and reliable and are more likely to receive funding (Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019). The resources logic is linked to perceived program effectiveness by securing necessary financial resources for the organization to operate effectively. However, current research stresses that accountability for the financial performance need to be aligned with accountability for other mission achievement to avoid mission drift (Hersberger-Langloh et al., Reference Hersberger-Langloh, Stühlinger and von Schnurbein2021).

To provide accountability for mission achievement, the outcome assessment logic has emerged. It shifts the focus from accountability for financial performance to accountability for effective outcomes. This logic describes the application of mechanisms that assess organizational performance in terms of program outcomes and promotes learning and continuous improvement in these outcomes. It comprises the implementation of processes that include data collection, evaluation, and comparison of program outcomes for continuous improvement (Carman & Fredericks, 2008, Reference Carman and Fredericks2010), as well as having the capacities to learn from evaluation outcomes (Liket et al., Reference Liket, Rey-Garcia and Maas2014). Monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) processes have become important mechanisms to materialize and provide accountability for organizational performance (Carman & Fredericks, Reference Carman and Fredericks2010; Liket et al., Reference Liket, Rey-Garcia and Maas2014). The outcome assessment logic is linked to perceived program effectiveness by promoting the continuous improvement in offered programs leading them to be more effective. The logic is driven by requirements of the funding market (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017), or by self- and peer-regulation initiatives which promote the definition of meaningful impact measures (Crack, Reference Crack2018; Gugerty, Reference Gugerty2008; Hengevoss & von Schnurbein, Reference Hengevoss and von Schnurbein2022).

More recently, scholars discuss a more constructivist conceptualization of nonprofit accountability which can be referred to as the discursive accountability logic (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Coule, Reference Coule2015; Crack, Reference Crack2018; Hengevoss, Reference Hengevoss2019). This logic shifts the focus of accountability for outcomes (financial and non-financial) to the process of discourse itself. It describes a discursive process of negotiation and deliberation between the INGO and a multiplicity of stakeholders that have different accountability demands. It implies that in this discourse primordial importance should be given to the accountability demands of beneficiaries (Crack, Reference Crack2013a; Williams & Taylor, Reference Williams and Taylor2013). The aim is to negotiate, weigh, and find consensus among different accountability demands. The underlying assumption is that discourse offers a legitimation process for specific organizational decisions and inherent outcomes, which are assumed to be more widely accepted and thus stable (Hengevoss, Reference Hengevoss2019; Herman & Renz, Reference Herman and Renz2008). The discursive logic is linked to perceived program effectiveness by allowing for mutual understanding between the INGO and different stakeholder and by promoting consensus in the case of diverging expectations. This, in turn, allows creating more perceived program effectiveness (Herman & Renz, Reference Herman and Renz2008). The logic can materialize in any form of dialogue, discussion, or negotiation between the INGO and multiple stakeholders. Important driving forces of the discursive logic include peer-regulation and participative processes (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Coule, Reference Coule2015; Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2003; Hengevoss & von Schnurbein, Reference Hengevoss and von Schnurbein2022). Peer-regulation initiatives promote exchange between members and place high importance on including beneficiaries into these conversations (Crack, Reference Crack2018). Ebrahim (Reference Ebrahim2003) distinguishes between two forms of participative processes: Deliberate communication and beneficiary engagement. The former refers to sharing information about organizational plans and activities with the public. The second form of participation describes the INGO’s active engagement of beneficiaries on the operational level (Liket & Maas, Reference Liket and Maas2015) or on the strategic level, where for instance representatives of beneficiaries are given a significant voice in decision-making processes (Wellens & Jegers, Reference Wellens and Jegers2011). Including beneficiaries’ perspective in strategic conversations can allow to counterbalance accountability claims of donors or regulatory institutions. For instance, having a representative of the beneficiary community on the board provides more credibility when presenting strategic decisions to funders and regulatory institutions. Further, external scrutiny and feedback can drive and strengthen discourse between the INGO and its stakeholders (Wellens & Jegers, Reference Wellens and Jegers2014b).

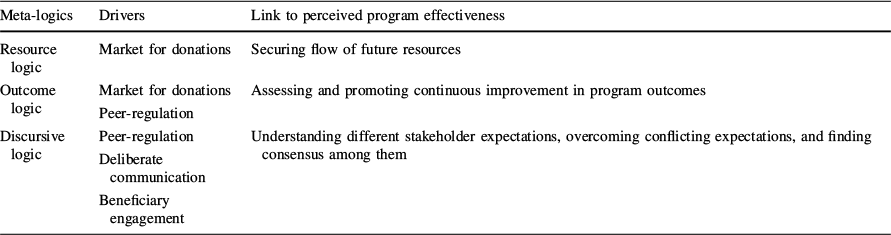

The three meta-logics describe different ends to which INGOs practice accountability and materialize through different mechanisms. Table 2 provides an overview of the meta-logics, their drivers, and their link to perceived program effectiveness. Moreover, they are incentivized by different driving forces. Together, the three meta-logics are theorized to form a comprehensive approach to INGO accountability that responds to different requirements for, and challenges to accountability. The meta-logics allow providing accountability for different understandings of organizational performance. The resource logic provides accountability for performance in terms of organizational growth, the outcome assessment logic provides accountability for performance conceptualized as goal attainment, and the discursive logic addresses accountability concerns in terms of closer stakeholder engagement (Lecy et al., Reference Lecy, Schmitz and Swedlund2012). Finally, the three meta-logics contribute to the different criteria that constitute INGOs’ organizational legitimacy (Atack, Reference Atack1999). They strengthen legitimacy by creating and measuring effectiveness (resource logic and outcome assessment logic), where legitimacy is achieved by demonstrating results. They further contribute to more legitimacy through representativeness and empowerment (discursive logic), where legitimacy is obtained by ensuring a process of decision-making viewed as legitimate. A more detailed overview of the three accountability meta-logics and their link to performance and legitimacy is found in the supplementary material.

Table 2 Framework for Comprehensive INGO Accountability

Meta-logics |

Drivers |

Link to perceived program effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

Resource logic |

Market for donations |

Securing flow of future resources |

Outcome logic |

Market for donations Peer-regulation |

Assessing and promoting continuous improvement in program outcomes |

Discursive logic |

Peer-regulation Deliberate communication Beneficiary engagement |

Understanding different stakeholder expectations, overcoming conflicting expectations, and finding consensus among them |

The comprehensive approach to accountability focuses less on accountability logics tied to stakeholders’ individual institutional logics, but seeks to strengthen INGOs’ mission achievement. However, empirical evidence for a positive link between comprehensive accountability and organizational performance remains scarce and is based on small-N studies (Jacobs & Wilford, Reference Jacobs and Wilford2010; van Zyl & Claeyé, Reference van Zyl and Claeyé2019). To gain more insight on the impact of comprehensive accountability on INGOs mission achievement more empirical testing is required.

Hypotheses

The previous section developed the conceptual framework for comprehensive INGO accountability. The expectations stemming from donors that provide resources in a competitive funding market influence how INGOs practice accountability. The funding market drives accountability that serves the resource security (resource logic) (Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019). Self- and peer-regulation initiatives drive the assessment of outcomes and promote discourse (discursive logic) between INGOs and their stakeholders. Participative processes in the form of deliberate communication and beneficiary engagement are further driving forces for discourse between the INGO and their stakeholders (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Coule, Reference Coule2015; Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2003). These drivers jointly strengthen the three meta-logics of comprehensive INGO accountability, which leads to the following hypothesis:

H1 (a) The market, (b) self- and peer-regulation, (c) deliberate communication, and (d) beneficiary engagement are significant drivers of the comprehensive INGO accountability approach.

The resource logic increases trust among donors and serves the stability of financial resources that are the baseline to create and run effective programs (Coule, Reference Coule2015; Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019). The outcome assessment logic promotes learning and continuous improvement to create effective programs (Carman & Fredericks, Reference Carman and Fredericks2010; Liket et al., Reference Liket, Rey-Garcia and Maas2014). The discursive logic follows a constructivist approach to accountability whereby different stakeholders discuss what the effective solution to a societal problem is. This discourse allows constructing a shared notion of effectiveness. The claim is that including all relevant stakeholders, and beneficiaries in particular, leads to a better understanding of what is considered effective (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Crack, Reference Crack2013b). Through the process of negotiation and consensus, decisions can be assumed to be more stable. This ultimately leads to greater perceived effectiveness of the offered programs. Jointly, the three meta-logics of comprehensive INGO accountability are linked to perceived program effectiveness, which leads to the following hypothesis:

H2 The comprehensive INGO accountability approach strengthens the perceived program effectiveness.

Finally, according to the institutional logics perspective, differing logics can coexist or a dominant logic can emerge (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio2008). To conceptualize a comprehensive accountability, it is essential to understand how different accountability logics influence each other. A resource logic is aimed at satisfying the demands of donors for accountability and is considered a crucial part of good governance (Coule, Reference Coule2015). Satisfying donors’ demands is linked to securing resources that allow the INGO to operate and generate an outcome in the first place. This links the resource logic to the outcome assessment logic. The outcome assessment logic is concerned with the organization’s mission achievement (Crack, Reference Crack2013b). This information is an essential baseline for discourse between the INGO and its stakeholders. This advances the third and fourth hypothesis:

H3 The resource logic has a positive effect on the outcome assessment logic.

H4 The outcome assessment logic has a positive effect on the discursive logic.

A graphical depiction of hypotheses is displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Hypotheses

Methodology

The hypotheses are tested applying a partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) analysis. PSL-SEM allows to simultaneously estimation multiple relationships between one or more independent variable(s), and one or more dependent variable(s) (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2014b). The model consists of latent constructs for the four identified drivers of INGO accountability, the three defined accountability meta-logics, and perceived program effectiveness. The constructs are based on measurement models that were first analyzed with a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). All analyses in this study are computed using the SmartPLS 3.0 software (Ringle et al., Reference Ringle, Wende and Becker2015).

Data

The data were collected via an international survey among CEOs of INGOs in 2020. Contact information from INGOs from two data bases were included in the sample: INGOs registered in the Swiss trade register and relevant organizations listed in the Yearbook of International Organizations (YIO). Switzerland has a strong nonprofit sector (von Schnurbein & Perez, Reference von Schnurbein and Perez2018), with many INGOs headquartered in Geneva. The YIO is a reference work for international organizations published by the Union of International Associations, containing information on over 40,300 intergovernmental organizations and INGOs, from over 300 countries and territories (Union of International Associations, 2020), and has been used in many studies on INGOs (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2013; Murdie & Davis, Reference Murdie and Davis2012). The sample included 635 INGOs registered in the Swiss trade register for which contact information was found. From the YIO, organizations classified as “international,” “national with an international scope of activity,” “membership-based”; “Humanitarian organizations” and “Human rights organizations” were retained, which yielded a sample of 808 relevant organizations with contact information. The resulting sample comprised 1443 INGOs. The paper-and-pencil questionnaire was addressed to the CEO of the organization.

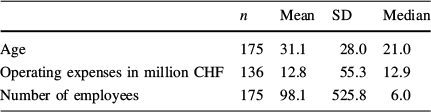

Three hundred and fifty-one responses (response rate 24.3%) were received and 201 organizations remained in the sample after listwise deletion of questionnaires with non-randomly missing data among the relevant variables. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is one of the largest cross-country samples of INGOs used for academic research. The largest sample size found in prior research comprised a considerable sample of 152 US-registered INGOs (Mitchell & Schmitz, Reference Mitchell and Schmitz2014). Sample size requirements for PLS-SEM were met, as 201 exceeds both (a) ten times the largest number of formative indicators used to measure a construct, and (b) ten times the largest number of structural path directed at a particular latent construct in the structural model (). The data set includes organizations from 21 countries, operating in over 120 countries located in the Global North and the Global South. The average organization is 31 years old, has 98 employees and operating expenditures of 12.8 Mio CHF in 2019 (see Appendix Table 4). The majority of the organizations are engaged in the fields of education and research (23%, 46 organizations), international development cooperation (19%, 38), and public health (10%, 20).

Measures

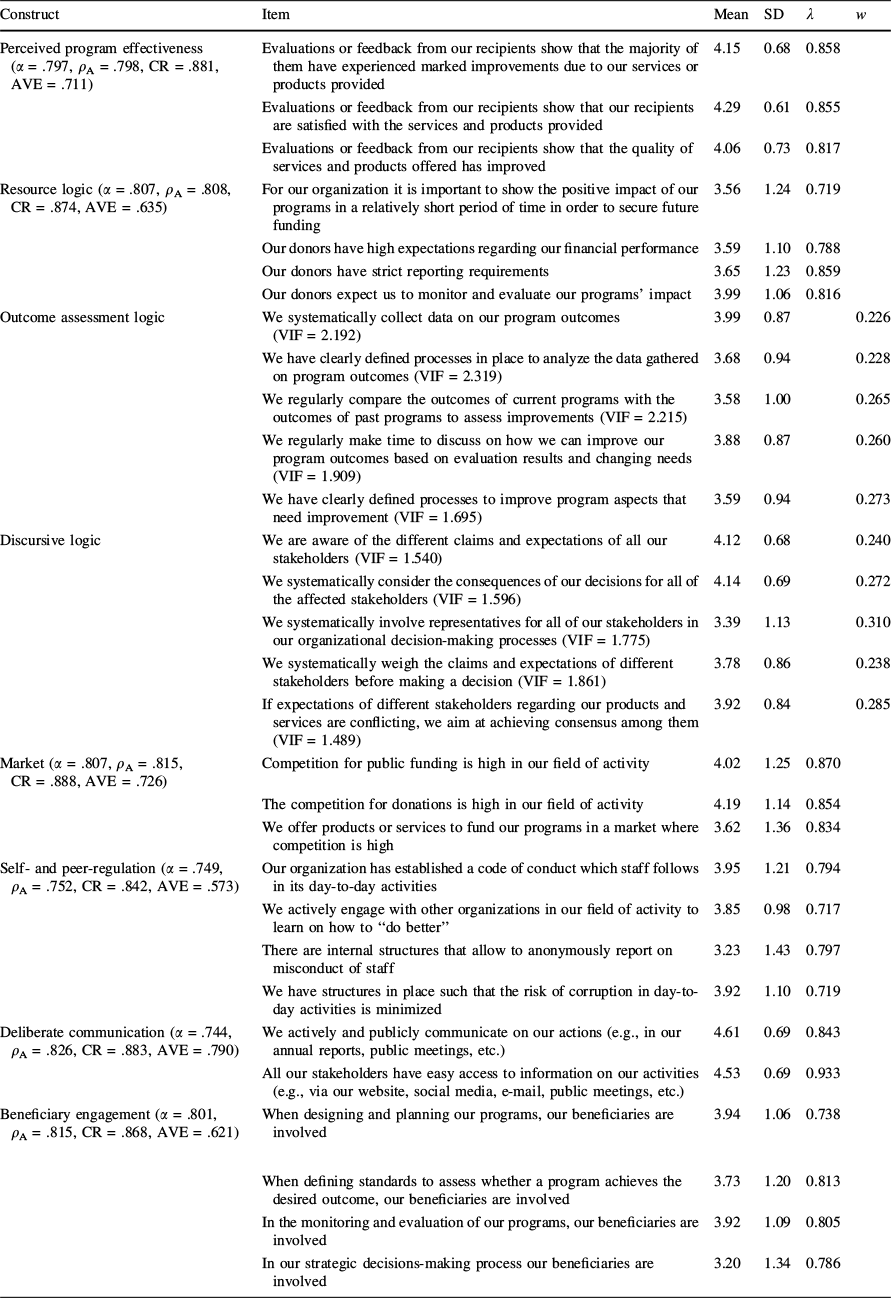

The PLS-SEM is based on eight latent constructs presented in Fig. 1. As items were collected via a survey, they represent the perception of the respondents. To minimize bias and avoid over-justification effects, the survey data were collected anonymously. The performance of INGOs is measured using a reflective construct for perceived program effectiveness. This is in line with previous studies (Brown, Reference Brown2005; Hersberger-Langloh et al., Reference Hersberger-Langloh, Stühlinger and von Schnurbein2021), who have assessed organizational performance by asking respondents to which they believe they have succeeded as an organization by assessing their mission achievement. The three items used are adapted from a scale of perceived organizational performance by Hersberger-Langloh et al. (Reference Hersberger-Langloh, Stühlinger and von Schnurbein2021) and assess output-oriented beneficiaries’ satisfaction and improvements in service quality. This allows assessing the perceived performance of programs that focus on service provision as well as on advocacy work.

The construct for the resource logic is self-constructed, reflective, and includes four items on donors’ reporting requirements and expectations for good financial performance. The construct for the outcome assessment logic is self-developed, and formative to include five items on an organization’s systematic monitoring of program outcomes, its capacity for evaluating collected data on program outcomes (Carman & Fredericks, Reference Carman and Fredericks2010), and the capacity for learning from evaluation results (Liket et al., Reference Liket, Rey-Garcia and Maas2014). The construct for the discursive logic is formative and was formed based on an adapted scale by Voegtlin (Reference Voegtlin, Pless and Maak2011). The construct includes items assessing the degree to which the board of directors follows deliberative practices that allow representing and weighing different accountability demands, as well as items on discursive processes to develop consensus.

The constructs for the four drivers of INGO accountability are reflective and were developed based on the reviewed literature. The market construct includes three items assessing the perceived competitiveness in the funding market. Self- and peer-regulation has been grouped into one construct as they present a regulatory approach that is voluntary and motivated from within the organization as opposed to external legal regulation. The construct includes items on the degree to which the INGO has a self-defined code of conduct and internal reporting mechanisms for misconduct of staff and corruption, as well as items on its openness to engage with and learn from peer-organizations (Gugerty, Reference Gugerty2008). The construct for deliberate communication is based on two items that include the deliberate communication on activities as well as the accessibility of information (Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2003). The measurement for beneficiary engagement is based on four items reflecting participative processes through which beneficiaries are involved in the program design and assessment (Liket & Maas, Reference Liket and Maas2015) and in strategic decision-making processes (Wellens & Jegers, Reference Wellens and Jegers2014a). Finally, the model controls for the effects of organizational size (number of employees) and age (years) on perceived program effectiveness.

All items are measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = [I] strongly disagree, to 5 = [I] agree strongly, which allows for the assumption of continuous variables (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2014a). Table 3 shows the items and descriptive statistics for all constructs.

Table 3 Measurement items, descriptive statistics, reliability, and validity indicators

Construct |

Item |

Mean |

SD |

λ |

w |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Perceived program effectiveness (α = .797, ρ A = .798, CR = .881, AVE = .711) |

Evaluations or feedback from our recipients show that the majority of them have experienced marked improvements due to our services or products provided |

4.15 |

0.68 |

0.858 |

|

Evaluations or feedback from our recipients show that our recipients are satisfied with the services and products provided |

4.29 |

0.61 |

0.855 |

||

Evaluations or feedback from our recipients show that the quality of services and products offered has improved |

4.06 |

0.73 |

0.817 |

||

Resource logic (α = .807, ρ A = .808, CR = .874, AVE = .635) |

For our organization it is important to show the positive impact of our programs in a relatively short period of time in order to secure future funding |

3.56 |

1.24 |

0.719 |

|

Our donors have high expectations regarding our financial performance |

3.59 |

1.10 |

0.788 |

||

Our donors have strict reporting requirements |

3.65 |

1.23 |

0.859 |

||

Our donors expect us to monitor and evaluate our programs’ impact |

3.99 |

1.06 |

0.816 |

||

Outcome assessment logic |

We systematically collect data on our program outcomes (VIF = 2.192) |

3.99 |

0.87 |

0.226 |

|

We have clearly defined processes in place to analyze the data gathered on program outcomes (VIF = 2.319) |

3.68 |

0.94 |

0.228 |

||

We regularly compare the outcomes of current programs with the outcomes of past programs to assess improvements (VIF = 2.215) |

3.58 |

1.00 |

0.265 |

||

We regularly make time to discuss on how we can improve our program outcomes based on evaluation results and changing needs (VIF = 1.909) |

3.88 |

0.87 |

0.260 |

||

We have clearly defined processes to improve program aspects that need improvement (VIF = 1.695) |

3.59 |

0.94 |

0.273 |

||

Discursive logic |

We are aware of the different claims and expectations of all our stakeholders (VIF = 1.540) |

4.12 |

0.68 |

0.240 |

|

We systematically consider the consequences of our decisions for all of the affected stakeholders (VIF = 1.596) |

4.14 |

0.69 |

0.272 |

||

We systematically involve representatives for all of our stakeholders in our organizational decision-making processes (VIF = 1.775) |

3.39 |

1.13 |

0.310 |

||

We systematically weigh the claims and expectations of different stakeholders before making a decision (VIF = 1.861) |

3.78 |

0.86 |

0.238 |

||

If expectations of different stakeholders regarding our products and services are conflicting, we aim at achieving consensus among them (VIF = 1.489) |

3.92 |

0.84 |

0.285 |

||

Market (α = .807, ρ A = .815, CR = .888, AVE = .726) |

Competition for public funding is high in our field of activity |

4.02 |

1.25 |

0.870 |

|

The competition for donations is high in our field of activity |

4.19 |

1.14 |

0.854 |

||

We offer products or services to fund our programs in a market where competition is high |

3.62 |

1.36 |

0.834 |

||

Self- and peer-regulation (α = .749, ρ A = .752, CR = .842, AVE = .573) |

Our organization has established a code of conduct which staff follows in its day-to-day activities |

3.95 |

1.21 |

0.794 |

|

We actively engage with other organizations in our field of activity to learn on how to “do better” |

3.85 |

0.98 |

0.717 |

||

There are internal structures that allow to anonymously report on misconduct of staff |

3.23 |

1.43 |

0.797 |

||

We have structures in place such that the risk of corruption in day-to-day activities is minimized |

3.92 |

1.10 |

0.719 |

||

Deliberate communication (α = .744, ρ A = .826, CR = .883, AVE = .790) |

We actively and publicly communicate on our actions (e.g., in our annual reports, public meetings, etc.) |

4.61 |

0.69 |

0.843 |

|

All our stakeholders have easy access to information on our activities (e.g., via our website, social media, e-mail, public meetings, etc.) |

4.53 |

0.69 |

0.933 |

||

Beneficiary engagement (α = .801, ρ A = .815, CR = .868, AVE = .621) |

When designing and planning our programs, our beneficiaries are involved |

3.94 |

1.06 |

0.738 |

|

When defining standards to assess whether a program achieves the desired outcome, our beneficiaries are involved |

3.73 |

1.20 |

0.813 |

||

In the monitoring and evaluation of our programs, our beneficiaries are involved |

3.92 |

1.09 |

0.805 |

||

In our strategic decisions-making process our beneficiaries are involved |

3.20 |

1.34 |

0.786 |

All factor loadings and weights are significant at p ≤ 0.001

Results

Measurement Model

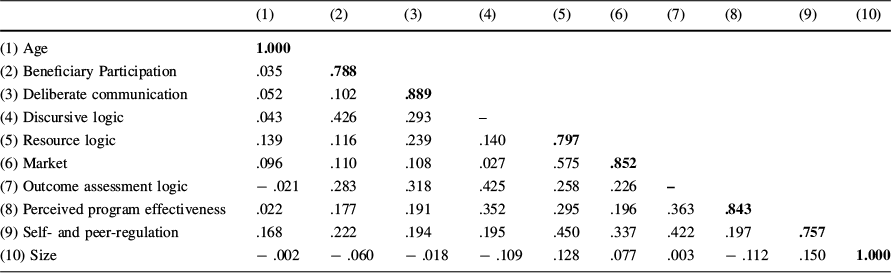

The PLS-SEM contains both reflective and formative constructs, which have differing assessment criteria. For the reflective constructs, item and construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were assessed. Item reliability was assessed by examining the construct-to-item loadings (λ), which all exceed the threshold of 0.708 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Risher, Sarstedt and Ringle2019). Construct reliability was assessed based on three measures: Cronbach Alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), and ρ A. All three measures largely exceed the threshold of 0.70 indicating construct reliability (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Risher, Sarstedt and Ringle2019). Convergent validity was assessed testing for the average variance extracted (AVE), which for all constructs exceeds the threshold of 0.50 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Risher, Sarstedt and Ringle2019). The Fornell–Larcker criterion (FLC) indicates discriminant validity (Appendix Table 5) (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). For formative constructs, indicator collinearity and statistical significance of indicator weights (w) were assessed. The outer-model variance inflation factors (VIF) values are below the threshold of 3.0 indicating that there are no collinearity issues (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Risher, Sarstedt and Ringle2019). Finally, all indicator weights are statistically significant at the 0.1% significance level (two-tailed test). All indicators are presented in Table 3.

Structural Model

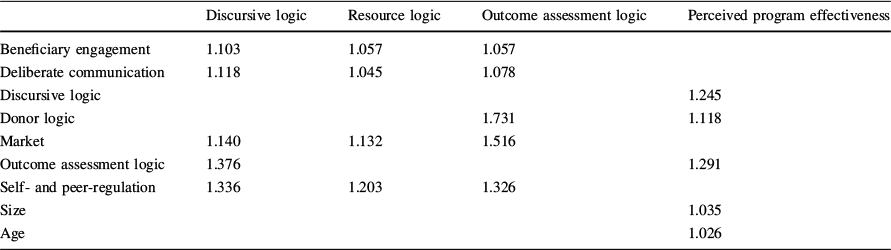

The results for the structural model show adequate predictive capabilities. Collinearity issues among endogenous constructs were excluded by testing for their inner-model VIF values, which were all under the threshold of 2.0 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2014a, Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2014b) (Appendix Table 6). Assessing predictive accuracy, the coefficient of determination (R2) suggests that the structural model explains 42.2% of the variance in the resource logic construct, 27.3% of the variance in the outcome assessment logic construct, 31.7% of variance in the discursive logic construct, and 23.4% of the variance in the perceived program effectiveness construct. Predictive relevance of the structural model is assessed based on the Stone–Geisser's Q 2 values (Geisser, Reference Geisser1974; Stone, Reference Stone1974). With all endogenous constructs including donor accountability logic (Q 2 = 0.243), outcome accountability logic (Q 2 = 0.163), discursive accountability logic (Q 2 = 0.188), and perceived program effectiveness (Q 2 = 0.178) yielding Q 2 larger than 0, the structural model provides sufficient predictive relevance.

Figure 2 shows the model with standardized coefficients, with significant paths displayed in black, and all other paths in gray. Significance levels of estimators are obtained by bootstrapping (5000 resamples) (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Risher, Sarstedt and Ringle2019). The market has a significant positive effect on the resource logic (0.470, p < 0.001). Self- and peer-regulation has a significant positive effect on the resource logic (0.266, p < 0.001) and on the outcome assessment logic (0.312, p < 0.001). Deliberate communication has a significant positive effect on the outcome assessment logic (0.231, p < 0.001) as well as on the discursive logic (0.175, p < 0.05). Beneficiary engagement has a significant positive effect on the outcome assessment logic (0.183, p < 0.01) as well as on the discursive logic (0.336, p < 0.001). Resource logic (0.227, p < 0.01), outcome assessment logic (0.212, p < 0.05), and discursive logic (0.219, p < 0.01) all have a significant positive effect on perceived program effectiveness. Moreover, the outcome assessment logic (0.298, p < 0.001) has a significant positive effect on the discursive logic.

Fig. 2 Results of PLS-SEM. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

The results of the above analysis are consistent with hypotheses 1, 2, and 4. The market, self- and peer-regulation, deliberate communication, and beneficiary engagement are significant drivers of a comprehensive INGO accountability approach. Comprehensive INGO accountability significantly strengthens perceived program effectiveness. The outcome assessment logic is an important baseline for the discursive logic. There is no evidence for hypothesis 3 as the resource logic has no significant effect on the outcome assessment logic. The following section discusses the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Discussion

In reaction to criticism about INGOs prioritizing the accountability demands of donors, the nonprofit management literature has yielded an important body of literature discussing a more comprehensive approach to INGO accountability. This study asked how comprehensive INGO accountability can strengthen program effectiveness. It addressed this question by establishing and empirically testing a framework for comprehensive INGO accountability. The framework describes three distinct accountability meta-logics that have different underlying drivers and jointly strengthen the perceived program effectiveness.

In line with a constructivist understanding of accountability (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Coule, Reference Coule2015; Crack, Reference Crack2018; Hengevoss, Reference Hengevoss2019), the results show that comprehensive INGO accountability leads to increased perceived program effectiveness. The resource logic which focuses on the reporting of results and good financial performance contributes to donor satisfaction and ensures the provision of future resources (Goncharenko, Reference Goncharenko2019), which is the baseline for creating and running effective programs. An outcome assessment logic fosters continuous improvement in programs to render them more effective (Liket et al., Reference Liket, Rey-Garcia and Maas2014). The discursive logic allows integrating conflicting expectations. Previous studies assessing dialogue- and negotiation-based accountability practices (discursive logic, found that these practices often were costly in terms of increased conflicts and tensions between different stakeholders (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019). By providing empirical evidence for a positive effect of discursive accountability on INGO perceived program effectiveness, this study relativizes these concerns about these negative effects of comprehensive accountability. Instead, it shows that a comprehensive approach to INGO accountability is a strategic decision that is linked to improved perceived organizational performance. This contributes to the strategic managerial argument for leaders of INGOs to implement processes that foster comprehensive accountability.

The established framework further has implications for theory building on INGO accountability. In line with previous frameworks, this study builds on the idea that INGO accountability follows multiple logics as advanced by the institutional logics perspective. Extant frameworks have described logics of, and inherent dynamics within, accountability relationships and, in particular, revealed difficulties and costs arising from conflicting logics (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Simons and Vandenabeele2017; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019). Critical research has highlighted the potentially harmful effects of accountability. Previous studies have shown that accountability logics that emphasize short-term operational behavior bear the risk of promoting organizational activities that are so focused on immediate output and efficiency that the organization loses sight of long-range goals concerning its effectiveness (Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2005). Alternative solutions on how to overcome these difficulties were lacking. This study followed the same theoretical approach. Instead of defining accountability logics tied to individual stakeholders it established a conceptual framework that defines accountability meta-logics that describe different ends to which INGOs practice accountability. These ends include the resource security (resource logic), the assessment of outcomes to improve organizational impact (outcome assessment logic), and discourse to understand different accountability demands and find consensus in case of conflicting demands (discursive logic). These meta-logics were then linked to organizational performance to empirically show that they each strengthen perceived program effectiveness. Moreover, the empirical findings suggest that these three meta-logics can coexist within an organization. The previous literature highlights differences and conflicts of different stakeholder groups. Applying accountability meta-logic can help to overcome these conflicts by integrating individual institutional logics through deliberate negotiation and dialogue. The study contributes to the theory building of INGO accountability as it shows that logics cannot only be defined on the relationship-level between the INGO and the individual stakeholder, but that there are meta-logics, which describe the ends to which accountability is practiced. In particular, the discursive logic strives to find consensus among different accountability demands. The underlying assumption is that discourse offers a legitimation process for specific organizational decisions and inherent outcomes, which are assumed to be more widely accepted and thus stable (Hengevoss, Reference Hengevoss2019; Herman & Renz, Reference Herman and Renz2008). Comprehensive accountability that is based on discourse is assumed to allow for a better management to overcome the challenges of the conflicting logics on the relationship level.

Conclusion

In this study, a framework for comprehensive INGO accountability has been developed. The framework describes three accountability meta-logics that each defines the ends to which accountability is practiced. The empirical results show that comprehensive accountability can strengthen an INGO’s perceive program effectiveness.

This study has some limitations. The findings are based on survey results. While the necessary precautions to reduce any form of bias when conducting the survey were taken, a certain degree of desirability bias in the answers cannot be excluded. Generally, it needs to be considered that surveys are limited in adequately generating differentiated answers for more complex topics. In this article, the focus laid on consensus as the desired outcome of discourse. Future research is encouraged to explore the implications of other outcomes of discourse for INGOs’ performance, such as majority votes. Consequently, the findings are to be understood as offering a valuable, yet first, step to test the drivers and implications of comprehensive INGO accountability, and should be generalized with caution.

Overall, the study advances theoretical insights on the conceptualization of accountability as a concept that follows multiple logics. It extends previous conceptualizations by defining three accountability meta-logics that focus on overcoming the challenges arising from conflicting accountability demands among stakeholders. In particular, the implementation of discursive processes that give voice to beneficiaries can be expected to become a crucial means to ensure organizational legitimacy. For leaders of INGOs, this suggests that implementing processes that combine the three meta-logics strengthens their ability to respond to external demands for financial and nonfinancial performance and is likely to successfully integrate and overcome differing expectations regarding their work. Finally, it provides first empirical evidence that implementing comprehensive accountability, not only is the “right thing” to do, but that it has the strategic benefit of improving perceived organizational performance and, thus, legitimacy.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

I have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix

Table 4 Descriptive statistics of sample characteristics

n |

Mean |

SD |

Median |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Age |

175 |

31.1 |

28.0 |

21.0 |

Operating expenses in million CHF |

136 |

12.8 |

55.3 |

12.9 |

Number of employees |

175 |

98.1 |

525.8 |

6.0 |

Table 5 Correlations between constructs

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) Age |

1.000 |

|||||||||

(2) Beneficiary Participation |

.035 |

.788 |

||||||||

(3) Deliberate communication |

.052 |

.102 |

.889 |

|||||||

(4) Discursive logic |

.043 |

.426 |

.293 |

– |

||||||

(5) Resource logic |

.139 |

.116 |

.239 |

.140 |

.797 |

|||||

(6) Market |

.096 |

.110 |

.108 |

.027 |

.575 |

.852 |

||||

(7) Outcome assessment logic |

− .021 |

.283 |

.318 |

.425 |

.258 |

.226 |

– |

|||

(8) Perceived program effectiveness |

.022 |

.177 |

.191 |

.352 |

.295 |

.196 |

.363 |

.843 |

||

(9) Self- and peer-regulation |

.168 |

.222 |

.194 |

.195 |

.450 |

.337 |

.422 |

.197 |

.757 |

|

(10) Size |

− .002 |

− .060 |

− .018 |

− .109 |

.128 |

.077 |

.003 |

− .112 |

.150 |

1.000 |

Table 6 VIF for endogenous constructs

Discursive logic |

Resource logic |

Outcome assessment logic |

Perceived program effectiveness |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Beneficiary engagement |

1.103 |

1.057 |

1.057 |

|

Deliberate communication |

1.118 |

1.045 |

1.078 |

|

Discursive logic |

1.245 |

|||

Donor logic |

1.731 |

1.118 |

||

Market |

1.140 |

1.132 |

1.516 |

|

Outcome assessment logic |

1.376 |

1.291 |

||

Self- and peer-regulation |

1.336 |

1.203 |

1.326 |

|

Size |

1.035 |

|||

Age |

1.026 |