The real argument for democracy is […] that in the people we have the source of that endless life and unbounded wisdom which the rulers of men must have.

W.E.B. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1920)

If you don't get out there and define yourself, you'll be quickly and inaccurately defined by others.

Michelle Obama (Reference Obama2018)

Introduction

Ethnic and racial minority citizens and women remain under‐represented in parliaments in most advanced democracies (Bloemraad & Schönwälder, Reference Bloemraad and Schönwälder2013), raising fundamental questions about the functioning of representative democracy (Dahl, Reference Dahl1989; Phillips, Reference Phillips1995). To study how the elected presence of historically disadvantaged groups affects political representation, scholars have turned to the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967) – or numerical presence and the legislative activity of representatives (e.g., Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2011; Sobolewska et al., Reference Sobolewska, McKee and Campbell2018). Others have focused on the role that shared experiences play (Allen, Reference Allen2022; Fenno, Reference Fenno2003) or the symbolic impact of descriptive representatives, particularly how they challenge norms and stereotypes (Ward, Reference Ward2016a). Inspired by Black feminists in the United States (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1991), political scientists have more recently turned to intersectional analysis to disentangle how experiences and possibilities in politics of members of parliament (MPs) are influenced by more than one category of difference (Brown & Banks, Reference Brown and Banks2013; Mügge & Erzeel, Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016; Mügge et al., Reference Mügge, Montoya, Emejulu and Laurel Weldon2018; Reingold et al., Reference Reingold, Haynie and Widner2020). Building on this literature, we ask: How do MPs with a migration background – hereafter ethnic minority MPs – represent their minoritized group identities and how does this play out intersectionally?

To answer these questions, we draw on maiden speeches, the first address of a newly elected MP in parliament. We aim to explore how and why ethnic minority MPs represent a particular mix of their group identities, based on among others, gender, race/ethnicity and how such representation of identities is influenced by the organizational context such as diversity networks in parties and political orientation. The maiden speech is a useful moment to compare the role identities play in representation since it is a similar landmark – a rite of passage – for each newly elected MP. How do ethnic minority MPs define themselves in such transitions before they are seen as MPs by others? What identities do they foreground? Maiden speeches are one of the most personal interventions in an MP's career. It is the moment when they give voters and their fellow politicians a taste of the type of politician they aspire to be and how they aim to use their newly acquired power. Studying this personal moment of transition adds a new focus to the study of representation from the point of view of minority MPs. Maiden speeches provide MPs with the opportunity to showcase themselves, mostly without the usual focus on a specific subject that drives discourses in parliament. It is a rite of passage that creates a unique opportunity to investigate how they articulate collective identities politically, from their own perspectives. While earlier empirical work on substantive representation has focused on bill sponsoring, parliamentary questions and symbolic accounts of representation in the media, the maiden speech captures a unique moment with both substantive and symbolic elements – one that captures the intersectional representational styles of ethnic minority MPs (cf. Fenno, Reference Fenno1978) in their own words.

Compared to other countries in the region, the Netherlands has one of the longest and strongest traditions of representation of MPs of immigrant origin (Espírito‐Santo et al., Reference Espírito‐Santo, Verge, Morales, Fernandes and Leston‐Bandeira2019; Mügge et al., Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019). We include in our study MPs who belong to historically marginalized groups, defined as those who have been ethnic minorities as set by the Dutch state based on their, or one of their parents, country of birth. Our sample includes all 93 ethnic minority MPs who have held a seat in the Dutch parliament since World War Two, of which 88 delivered a maiden speech. The scope of our study allows exploration over time, within and between different parties and identities.

We study whether self‐representation of a minority identity comes from the presence of a ‘first’ (by gender and migration background) and by the context of the political party. We consider minority identities as any identity that deviates from the white, male, theoretically educated, heterosexual norm that dominates Dutch politics. We then pursue an in‐depth narrative analysis of the stories minority MPs bring to the political arena to illustrate how their (intersectional) identities matter to them and how they inform their political work. Although we study the entire population of ethnic minority MPs in the Netherlands, our sample is small (N = 93). Nevertheless, we can glean general descriptive trends: environment matters. MPs who emphasize a minority identity are less often the ‘first’ women or men MPs of an ethnic minority group. MPs who refer to a minority identity more often represent progressive parties, with all sorts of active diversity networks. More than half of the ethnic minority MPs in our sample (52/88) refer to an identity in some form in their maiden speech; a smaller portion (38/88) refers to a collective minority group identity, such as migration background or gender (see online Appendix 6). As ours is the first limited‐scale but in‐depth exploration of the maiden speech as empirical subject, we cannot – nor do we aim to – disentangle these outcomes.

Our analysis shows that narrating shared experiences along collective lines of minority identities is a relatively recent phenomenon. While both men and women refer to minority identities, few women do so intersectionally by combining this with reference to their gender identity. In the narrative analysis, we show how these MPs represent their collective identities illustrated by stories of shared experiences along the intersectional lines of ethnicity, gender, education, sexuality and religion, with personal stories and family histories serving as vehicles to counter stereotypes, to unmute silenced cultures and share reassuring values. The political narrative is a strategic tool par excellence for MPs from historically disadvantaged groups to represent collective minority identities.

Political narratives and representation

A perennial puzzle in the scholarship on the representation of historically disadvantaged groups is the extent to which the elected presence of ethnic minority politicians leads to the championing of their interests. Does descriptive representation lead to substantive representation (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967)? Empirical studies report mixed results. In the United States and the United Kingdom, scholars find a positive relation between descriptive and substantive representation of ethnic and racialized politicians (e.g., Hardy‐Fanta et al., Reference Hardy‐Fanta, Pinderhughes and Sierra2016; Saalfeld & Bischof, Reference Saalfeld and Bischof2013). A German study concludes that newly elected MPs of immigrant origin have an incentive to engage in substantive group representation, but that this diminishes over time (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Breunig, Giger and Wüst2021, p. 12). Others emphasize the importance of critical ‘acts’ over mere numerical presence (Childs & Krook, Reference Childs and Krook2009). Reynolds (Reference Reynolds2013) shows that even in small numbers, the presence of LGBT MPs encourages the adoption of gay‐friendly legislation.

The political presence of disadvantaged groups means more than the inclusion of bodies that appear different from the erstwhile norm; it also has symbolic impact, which can be a consequence of both descriptive and substantive representation, simultaneously and in their own right (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967). Lombardo and Meier define symbolic representation as ‘the representation of a constituency through a symbol that presents this constituency in a particular way and thus constructs meanings about it’ (Reference Lombardo and Meier2019, p. 234). Symbols can be material such as bank notes, or refer to physical embodiments such as a woman minister. Symbolic representation also entails how politicians are represented in the media. Minority women MPs in the United Kingdom, for instance, receive less positive and more negative coverage than all other racialized gender groups. The intersectional dynamic is thus a double‐edged sword (Ward, Reference Ward2017): although minority women politicians are more visible due to their ‘otherness’, their visibility also more often carries negative connotations, for example when they are treated by others as tokens (Ward, Reference Ward, Brown and Gershon2016b).

Hyper‐visibility has negative effects as it distracts attention from the political message and reinforces stereotypes such as that of the angry Black woman (Collins, Reference Collins1990). A U.K. study finds that coverage of women candidates disproportionately focuses on their gender to the detriment of their ideas, thereby reinforcing the norm of the male politician (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Evans, Harrison, Shears and Wadia2013). Dutch studies on ethnic minority MPs find that all are framed in newspaper coverage in terms of their ethnic background (Mügge & Schotel, Reference Mügge and Schotel2017; Runderkamp et al., Reference Runderkamp, Pas, Schotel and Mügge2022). There are also intersectional effects. While women are framed as the ‘other’ in multiple ways (e.g., Moroccan Muslim woman), men are framed in such a way that they come closer to the norm (e.g., Moluccan from the [Dutch city of] Vlissingen). In a matched‐sample comparison of Dutch ethnic minority men and women MPs with native Dutch men and women MPs, we find that all MPs who differ from native men MPs suffer from stereotypical treatment in the media (Runderkamp et al., Reference Runderkamp, Pas, Schotel and Mügge2022). In a scarce political science account of the self‐representation of politicians, Brown and Gershon (Reference Brown and Gershon2016a, p. 102) find that racial minority Congresswomen are more likely to emphasize their race, ethnicity or gender on their webpages than their white female and minority male peers. These self‐representations thus differ from what scholarship finds in media representation.

Extant empirical research largely focuses on the link between one or two descriptive characteristics of elected politicians and their legislative work. Popular data sources for this quantitative work – which relies on top‐down gender and race/ethnicity categories – include parliamentary questions, speeches, voting records, committee memberships, bill sponsoring and newspaper coverage. Our approach differs. Although we begin with established categories of gender and ethnicity, we continue by focusing on self‐representation in political narratives, providing more detailed and unmediated insight into representational styles, and which identities are foregrounded. These are not individual identities per se but rather references to collective or shared identities that are tied to being a member of a marginalized group, like a citizen with a migration background, having a history of refuge, or being a woman. We conducted a mixed‐methods study to uncover the frequency of self‐representations as well as their content and implications (Ward, Reference Ward2017).

Narratives make identities visible in politics. Narratives can explain values and ideals, advance representative claims, and can also – or especially – be used for political purposes. Saward argues that the most compelling representative claims ‘resonate among relevant audiences, will be made from “ready‐mades”, existing terms and understandings which the would‐be audience would recognize’ (Reference Saward2006, p. 303). Speakers thus construct relations with their audiences and constituencies: ‘The speaker appeals to assumed history or set of values salient for this audience. He uses jokes, figures of speech, idioms, that resonate with this audience and may not with others’ (Young, Reference Young2000, p. 68).

The maiden speech is first and foremost a political narrative. Amongst others, for Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (Dalvean, Reference Dalvean, Dowding and Lewis2012; Pitman, Reference Pitman2012; Rush & Giddings, Reference Rush and Giddings2011), the maiden speech is ‘a rite of passage, serving to admit one into the exclusive club’ (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen1988, pp. 527−528). While the maiden speech is a potential data honeypot, there are – to our knowledge – only two studies from the 1980s that use it as a primary data source (Horn et al., Reference Horn, Leniston and Lewis1983; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen1988).

The Dutch copied the maiden speech from the British. The ritual is not formally stipulated in parliamentary rules, and the practice has evolved over time. A maiden speech is given only once after an MP's first election. The MP may not be interrupted, is lauded by following speakers, receives flowers and is congratulated by the speaker of the house. Because MPs cannot be interrupted, the maiden speech provides an unimpeded opportunity to position themselves. Due to the personal nature of the speech, it may contain narratives that do not reflect the experiences of privileged groups. Ethnic minority MPs tend to have different stories that may previously have been silenced or unheard in society (cf. Landamore, Reference Landamore2020). By sharing stories in maiden speeches, they become of political use. Young (Reference Young2000) argues that stories serve as the only means for marginalized groups to get some understanding of their problems and experiences. Others argue that narratives are unavoidable when it comes to issues such as values and identities (Engelken‐Jorge, Reference Engelken‐Jorge2016).

Maiden speeches are an indication of an MP's representational style and may contain both substantive and symbolic promises and messages. In line with Ruedin, a maiden speech might be seen as a ‘low‐cost’ substantive activity to represent their respective group (Reference Ruedin, Rohrschneider and Thomassen2020). Against the backdrop of media framing, expectations from minority communities and the party, ethnic minority MPs must strategically decide whether to refer to their subordinate descriptive characteristics in their maiden speeches or not. Their decisions will be penalized by some and applauded by others. Electorally, it may be wise to blend in to prevent accusations of clientelism (Rosenberger & Stöckl, Reference Rosenberger and Stöckl2018) and to appeal to a larger group of (majority white) voters (Brown & Gershon, Reference Brown and Gershon2016a; Van Oosten et al., Reference Van Oosten, Mügge and van der Pas2023), although this may lead to charges of ‘selling out’ (Beatty, Reference Beatty2015). MPs’ references to a minority identity may signal empathy and show (intentions of) substantive representation to work on behalf of certain constituencies (De Jong & Mügge, Reference de Jong and Mügge2023a, Reference de Jong and Mügge2023b).

Group visibility in parliament

The reference of MPs to identities might be influenced by the visibility of diversity in the parliament. The election of a historic ‘first’ – say the first woman or the first person of colour in a particular position in Western democracies – is highly symbolic; their presence may forever change the nature of political representation (Gauld, Reference Gauld1998). With their appearance deviating from the erstwhile norm, they are hyper‐visible ‘space invaders’ (Puwar, Reference Puwar2004) who are simultaneously included through equal political rights and excluded in that dominant discourses ‘make assumptions they do not share, the interaction privileges specific styles of expression, [and] the participation of some people is dismissed as out of order’ (Young, Reference Young2000, p. 53). In the United States, Falk (Reference Falk2010) finds that women ‘firsts’ receive more media coverage, albeit not necessarily positive. Women and ethnic/racial ‘firsts’ in the United States tend to present themselves as representatives of under‐represented groups, both descriptively and symbolically, especially when there are electoral rewards for doing so (Simien, Reference Simien2015). A Spanish study finds that almost all ‘first women’ on both the left and right refer to their gender and substantive issues like women's rights and gender equality (Verge & Pastor, Reference Verge and Pastor2018).

In the Netherlands, ethnic minority MPs have over time become a structural feature in the make‐up of parliament. Diverse in (parental) birth country and gender, the ‘firsts’ of a particular ethnic group will have different experiences than those who follow, whose hyper‐visibility will likely fade over time but who may still experience forms of exclusion such as tokenism or silencing (Hawkesworth, Reference Hawkesworth2003). Based on findings from the literature on intersectionality and representation, we assume that the experiences of the first men and women MPs of a particular ethnic minority group will differ from those who follow in their footsteps. We thus construct intersectional groups based on gender and (parental) birth country and explore whether and how these ‘firsts’ to give a maiden speech refer to their gender and/or ethnic minority identity. Given the negative symbolic hypervisibility of the firsts, we explore whether this group emphasizes a minority group identity less often than non‐firsts, as it may benefit them electorally to present themselves as representatives of all citizens. We ask whether, once ethnic minority representation has become a structural feature in parliament and the public has become more accustomed to parliamentary diversity, there might be more room for alternative representations of identity.

Role of political parties

From earlier scholarship, we know that political parties are likely to influence whether ethnic minority MPs talk about their identity. Left‐leaning post‐materialist parties are more likely to have positive views on minority groups, to support minority rights, and to be ideologically committed to protect and promote marginalized communities (Htun & Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2018; Mazur, Reference Mazur2002). Such parties are thus more likely to have women and ethnic minority citizens among their MPs (Caul, Reference Caul1999; Sobolewska, Reference Sobolewska2013; Wängnerud, Reference Wängnerud2009). Researchers find a similar pattern for the Netherlands, with policy positions on migration and integration determining the number and position of minority candidates on electoral lists. Parties with more restrictive positions on migration and integration place fewer ethnic minority candidates on their lists; when they do so, they are lower down. The opposite is the case for parties with more liberal positions on migration and integration (Van der Zwan et al., Reference Van der Zwan, Lubbers and Eisinga2019). Therefore, we ask: How does the political party environment enable the self‐articulation of minority identities in the maiden speech? This includes (1) progressive‐conservative party cleavages and (2) within‐party networks.

The progressive‐conservative dimension (GAL/TAN) of political parties’ social and cultural values (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020) trumps economic left‐right cleavages in explaining differences in their substantive representation of minorities. Ethnic minority MPs from culturally progressive parties adopt more supportive framings of cultural and/or religious rights and liberties, while ethnic minority MPs from more conservative parties adopt more suppressive frames (Aydemir & Vliegenthart, Reference Aydemir and Vliegenthart2021). We explore whether the same progressive/conservative divide holds for mentioning of minority identities in maiden speeches.

Diversity networks within political parties may advocate for more diversity in political parties (Krook & Norris, Reference Krook and Norris2014). They lobby for targets or quotas, for candidates, representation in leadership positions, and substantive equality issues in party manifestos (Celis et al., Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014). While these networks push to improve descriptive representation, they are also well‐positioned to battle against tokenism. The encouragement of women's descriptive representation often goes hand in hand with openly acknowledging the importance of ethnic diversity. Such efforts are thus crucial to lobby for all kinds of diversity, especially in a national context without binding quotas. Ethnic minority MPs who represent parties with strong women's or multi‐ethnic networks will have more opportunities to address their (intersectional) minority identities in their narratives (Mügge & Damstra, Reference Mügge and Damstra2013; Mügge, Reference Mügge2016).

In‐depth narrative analysis

We use Young's (Reference Young2000, pp. 72−80) framework about communication across differences to distinguish between the different forms of shared experiences and how they are used by the subset of MPs who highlight their (intersectional) identities (N = 52/88). These references to collective identities can be used strategically to foster recognition between and within groups. Young distinguishes between four types of narrative strategies used by marginalized groups, which MPs can use to deliver both symbolic and substantive messages. In the context of hostile media frames of politicians of colour in general, and anti‐immigrant and anti‐Islam politics, all strategies could be used to justify that they are perfectly fit as Dutch MPs.

-

(1) Response to the ‘differend’ refers to a situation in which groups who suffer harm or oppression ‘lack the terms to express a claim of injustice within the prevailing normative discourse’ (Young, 2000, p. 72). Storytelling here serves as a bridge between the ‘mute experience’ of the respective minority group and arguments for political justice (Young, 2000, p. 72). An opportunity to develop a new vocabulary to express injustices and to bring them to public light, the strategy is likely to be used by MPs belonging to groups who experience structural racism and discrimination. As in many other West‐European immigration countries, Muslim politicians in the Netherlands contest anti‐Islam discourses, which will likely be reflected in maiden speeches (Severs et al., Reference Severs, Celis and Meier2013).

-

(2) Facilitation of local publics and articulation of collective affinities. Storytelling is a powerful instrument for a collective to identify with each other ‘with respect to particular interests, opinions and/or social positions’ (Young, Reference Young2000, p. 73). The narrative facilitates recognition of people from the same ‘public’. We expect this strategy to be useful for MPs who wish to emphasize a symbolic message that they are in parliament to represent that particular group (Brown & Gershon, Reference Brown and Gershon2016a, Reference Brown and Gershon2016b).

-

(3) Understanding the experience of others and countering stereotypes. The political narrative may serve as a vehicle to make others understand one's experience and to counter stereotypes – a strategy suitable for MPs seeking to explain their views to the native majority and how these are rooted in their personal histories. This is in line with our readings of autobiographies of (former) ethnic minority politicians (cf. Hirsi Ali, Reference Hirsi Ali2006; Cherribi, Reference Cherribi2010).

-

(4) Unveiling the source of values. Narratives can help to explain values, distinguishing between what is important and trivial, and why something is valued. Especially myths and historical narratives are used to show what practices, places and symbols mean to people and where their values originate: ‘Through this narrative, outsiders may come to understand why the insiders value what they value and why they have the priorities they have. (…) Those facing such a lack of understanding often rely on (…) to explain “where they are coming from”’ (Young, Reference Young2000, p. 75). This strategy will likely be used by MPs to elaborate substantive ideas. They may use references to well‐known historical figures to legitimize their claims in a way that is understandable to the audience (Saward, Reference Saward2006).

Context and methods

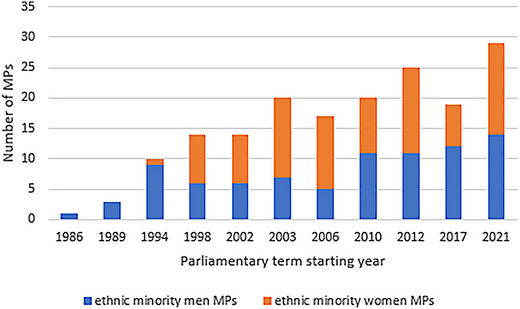

Before the 1980s, there was limited supply and demand for ethnic minority MPs in the Netherlands. This changed as more immigrants obtained Dutch nationality and voting rights. To cater to this electorate, parties started to recruit ethnic minority candidates. Since 2003, citizens with ‘non‐Western’ migration and post‐colonial backgrounds have been represented in the Dutch parliament roughly equal to ‘their’ share of the population (between 10 and 18 per cent). Compared to other European immigration countries, the Netherlands has one of the longest and percentage‐wise strongest representation of MPs with migration backgrounds (Espírito‐Santo et al., Reference Espírito‐Santo, Verge, Morales, Fernandes and Leston‐Bandeira2019). Their share dropped in 2017 due to the rout of the Labour Party which had the largest number of ethnic minority MPs (28/93) (see Figure 1). The Netherlands is the first country in which immigrant‐origin politicians have founded their own political parties: ThinkFootnote 1 in 2015, and AsOne in 2016.

Figure 1. Ethnic minority MPs in the Dutch parliament by gender since 1986 (N = 93). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Our sample includes all MPs from ethnic minority groups that have been targeted in Dutch migration and integration policies (Rath, Reference Rath1999; Scholten, Reference Scholten2011). They belong to a ‘marginalized ascriptive group’ characterized by (1) social and political inequality along group membership, (2) group membership that is not necessarily voluntary, (3) group membership is not experienced as mutable and (4) dominant culture and society assign negative meanings to group identity (Williams, Reference Williams1998, pp. 15−18). We rely on the official categories used by the Dutch Central Bureau for Statistics (CBS) that defines a person with a migration background as a person with at least one foreign‐born parent or is born abroad themselves. The CBS differentiates between ‘Western’ and ‘non‐Western’ citizens with a migration background. This contested terminology is based on a country's socioeconomic and cultural position and is highly racialized, as ‘Western’ mostly refers to majority white countries (Mügge & Van Der Haar, Reference Mügge, van der Haar, Garcés‐Mascareñas and Penninx2016; Yanow & Van Der Haar, Reference Yanow and Van Der Haar2013). Our sample includes MPs with at least one parent born in a (former) Dutch colony, a ‘non‐Western’ country or a South European labour‐exporting country as well as refugees and their children. We exclude MPs born in one of these countries to two ethnically Dutch parents since they are not minoritized (see online Appendix 1 for our sampling strategy).

The sample includes 93 ethnic minority MPs, covering 35 years spanning 11 parliamentary terms (1986–2023). While the first ethnic minority MP, Rustam Effendi, born in the Dutch East Indies, represented the Communist Party from 1933 to 1946 (Leenders, Reference Leenders2013), our study begins four decades later when the first ethnic minority MP after World War II was elected in 1986 (Appendix 2 with all MPs under study is available with the authors). Biographical information to compile the list of MPs was collected from the website of the Parliamentary Documentation Centre,Footnote 2 the House of Representatives,Footnote 3 and, where available, from the Open Research Area Funded project ‘Pathways to Power: The Political Representation of Citizens of Immigrant Origin in Seven European Democracies’ (PATHWAYS).Footnote 4 Full transcripts of maiden speeches between 1986 and 1994 were collected from the public digital archive Staten‐Generaal Digitaal.Footnote 5 Speeches from 1995 onwards were retrieved from the public database overheid.nlFootnote 6 and tweedekamer.nl.Footnote 7 At the time of writing, the majority of MPs (88/93) had delivered a maiden speech.

Both authors first inductively coded all maiden speeches for references to an identity (e.g., gender, religion, parental birth country) until subsumption, using the qualitative data analysis software nVivo. This resulted in 23 codes (see online Appendix 3) and a first overview of the identities MPs referred to in their maiden speeches. Then both authors coded thematically, searching for references to minority identity – labels of groups historically disadvantaged and/or under‐represented in Dutch politics (e.g., Muslim, woman, migrant, lower education) as opposed to the identity labels of groups historically in power (e.g., university education, man, Dutch regional background) (see the code book in online Appendix 4 and all minority identity quotes in online Appendix 6). We then studied these references to a minority identity in their political context, such as party and if the MP is a ‘first’ to give a maiden speech. Finally, we closely read the maiden speeches in light of the strategies in Young's (Reference Young2000) framework on difference.

Results

Over time

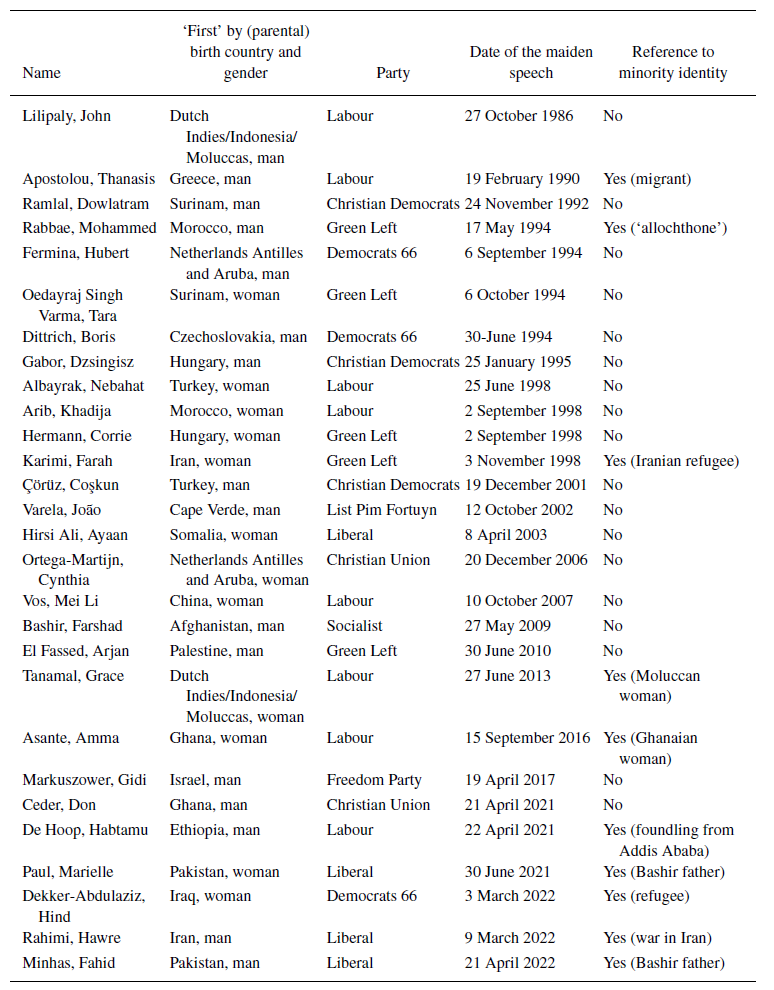

In total, 28 MPs were the first of their (parental) birth country and gender to deliver a maiden speech (see Table 1). The firsts are more often men (16) than women (12) and have roots in 19 different countries. Most firsts (eight) represent the Labour Party.

Table 1. Firsts in Dutch Parliament by (parental) birth country and gender to give a maiden speech, 1986–2023 (N = 28)

Does being the first of an intersectional ethnic minority group make the MP less likely to emphasize group identities, but rather to represent themselves not as ‘minority’ politicians? A chi‐squared test between firsts and non‐firsts and reference to a minority identity does not reveal a statistically significant difference between groups (p = 0.334). Nevertheless, the whole population of maiden speeches by minority MPs reveals a difference between firsts (10/28 or 36 per cent) and non‐firsts (28/60 or 47 per cent) referencing a minority identity. Indeed, descriptively, less ‘firsts’ mention their minority identity.

The first ethnic minority man and woman MPs, Lilipaly and Oedayraj Singh Varma do not refer to their minority identities but to substantive policy issues on which they are spokespersons: Lilipaly on minority policy (1986), Oedayraj Singh Varma on healthcare (1994). Lilipaly is critical of the minority policy and addresses affirmative action in the labour market and the inclusion of ethnic minorities in government institutions. He refers to the experience of his ethnic group to criticize the government, pointing to failed agreements with the Badan Persatuan, a Mollucan political party which represented the interests of the Mollucan people in the Netherlands (Smeets & Steijlen, Reference Smeets and Steijlen2006). Oedrayraj Singh Varma does not refer to ethnic minority groups but to the elderly.

Ten of the 28 ‘firsts’ refer to a minority identity in some way, connecting their backgrounds to their symbolic roles and substantive contributions as MPs. Apostolou gave a long speech in 1990 about the political, socio‐economic and cultural rights of ‘migrants’. Regarding the increasingly ‘migrant‐unfriendly’ societal and political climate, he says: ‘Coming from the circle of migrants in this country and as member of this parliament, I would like to express my disgust and indignation at the organisations that have made migrants the target of their political activity’.

Minhas (2022) states that his father's positive reception in the Netherlands as a guest worker inspired his entry into politics. Others open their speeches with their personal migration stories. Karimi refers to the authoritarian regime of her country of birth (Iran) and emphasizes the role of European integration:

In the early 1980s, I was engaged in a fierce struggle for democracy and respect for human rights and against a system in which criticizing those in power and standing up for the desire for freedom, equality and fraternity – that sounds European, doesn't it? – was prohibited. Asking for democratic rights was a crime, big enough to pay for with one's life. If someone had told me at the time: ‘but dear Farah, in only 20 years you will be in the Dutch Parliament, one of the oldest democracies in the world’, I would very likely have called that person a fool. But now I'm standing here, in flesh and blood. Europeans have many roots. (1998)

Three firsts (Asante, De Hoop and Paul) use their personal stories to support their substantive ideas on education and equal opportunities. Asante mentions her first Dutch friend at school and shares her childhood experiences with discrimination and racism:

Without permanent residency, without the willpower of my parents, without accessible education, without my friend Gabriella, I probably would never have been here. It has taught me that politics matters. So, what we do here can directly affect the lives of people in this country. I'm more aware of that than anyone else. Politics can make society more beautiful, fairer and especially offer opportunities to people for whom success is not a given. (2016)

De Hoop shares his adoption story as well as the farmer history of the parents who raised him to illustrate his enthusiasm for a specific education policy proposal:

As their son I know that equal opportunities are not part of your DNA. It is about the people who are around you. That is what equal opportunities are about. Equal opportunities are so much more than luck. It is about learning opportunities at school, experiences or the soccer coach in your village […] As a society and in politics, we have the responsibility to organize this for every child. (2021)

Of the 12 ‘first’ women only two refer to their gender. Tanamal represents herself intersectionally and opens her speech with the words:

It is my honour to be the first woman of Moluccan descent in the Dutch parliament. My father had a dream: studying in the Netherlands and becoming an officer in the Dutch army. Together with my mother, Dutch but born and raised in Indonesia, he made his dream come true, partly in The Hague. […] My parents are no longer alive, but I wish they could be here to share my experience of standing here now, at the heart of our democracy. (2013)

Tanamal goes on to narrate how she observed the exclusion and inequalities faced by citizens of the Dutch Indies and Moluccas and how she decided to do something about it once she was an adult. That time has come as an MP. Assante represents her gender as the daughter of a former factory worker and chambermaid.

Organizational context of the political party

We then ask if ethnic minority MPs representing culturally progressive parties more often narrate their minority identities than their conservative colleagues following the GAL/TAN dimensions (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020). We perform a chi‐squared test to assess the relation between party ideology and reference to a minority identity. The results are not significant (p = 0.107), but indeed, MPs who narrate an ethnic minority identity more often represent progressive parties (29/59 or 49 per cent) than conservative parties (9/29 or 31 per cent).

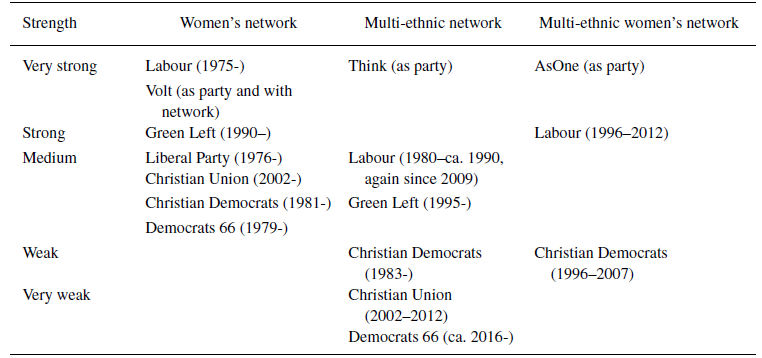

Table 2 depicts parties with (former) women's‐, multi‐ethnic‐, multi‐ethnic women's‐ or diversity‐networks. There is considerable overlap between the GAL/TAN dimensions and having a diversity network, as well as whether and how these parties support minority groups. If parties are not represented in Table 2, they lack such networks. The recently established parties (AsOne, Think, Volt) are exceptions as they do not always host specific networks but represent themselves as, respectively, intersectional‐, feminist‐ and ethnically diverse parties.Footnote 8 For this reason, they are included in the table. We ask whether ethnic minority women MPs representing parties with women's networks more often represent gender identity than their colleagues in parties with weak or without women's networks. Ten ethnic minority women MPs mentioned gender identity in their maiden speeches; nine of them represented parties with strong or medium women's networks or an intersectional party (see online Appendix 5 for a full overview including quotes).

Table 2. Diversity networks

Note: Data are updated by authors using publically available information. For Labour Party: https://www.pvda.nl/partij/netwerken/netwerk‐diversiteit/; accessed 23 July 2021 and Sylvester (Reference Sylvester2021). For Democrats 66: https://twitter.com/d66div?lang=en, accessed 23 July 2021.

Source: Mügge and Damstra (Reference Mügge and Damstra2013).

More than half (20/38) of the MPs who mention their collective ethnic minority identity represent Labour (14), Green Left (four), AsOne (one) and Think (one) which had medium strong multi‐ethnic networks or are characterized as new ‘immigrant parties’. However, the other 18 MPs who mention an ethnic minority identity represent parties with weak or no multi‐ethnic networks. So descriptively, diversity networks do not seem to play an important role. While some represent parties that have strong diversity networks or are intersectional (e.g., Labour, AsOne), eight represent Democrats 66, a party with a very weak diversity network. No ethnic minority women MPs representing the Christian Democrats refer to intersectional identities although the party had an intersectional multi‐ethnic women's network. Thus, the availability and strength of diversity networks in parties does not help us understand how the political and organizational context shapes the ability to represent ethnic minority or intersectional identities in maiden speeches per se.

Narratives across difference

Which strategies in Young's (Reference Young2000) typology do we find in the maiden speeches under study? In most cases, references to any – minority or not – identity are one‐liners. In a few cases, a rich personal story incorporates more than one type of narrative. Others do not mention any kind of minority identity but do apply one of Young's strategies.

The first way in which narratives can further discussion across differences is by responding to the ‘differend’. Several maiden speeches narrated how MPs, their parents or grandparents had suffered injustice. Günal‐Gezer mentioned she had come a ‘long way’ as the daughter of a guestworker. Several stories narrated refuge, such as the speech by Yeşilgöz‐Zegerius:

I came to this country with my parents over 30 years ago as a political refugee. My parents fought for equal rights for gays, for religious minorities, for secular people and for many others. At one point, the situation became too dangerous for them. They had to choose to leave everything behind and build a new life elsewhere. (2017)

Multiple stories narrate personal experiences with exclusion and go on to emphasize the significance of the moment to them and their families. Others use the maiden speech to address the ongoing generational exclusion of all people with an ancestral migration background in the Netherlands:

I see that we will soon be able to replace the American dream with the Dutch dream […] We fight against discrimination, which is also persistently present in the Netherlands today, sometimes against the current. People with a migration background, of the first, second or third generation, are included. They are Dutch. It is deeply sad that they are treated differently in the Netherlands in 2017. There must be permanent attention for this. (Bouali, 2017)

The second strategy is the facilitation of local publics and the articulation of collective affinities. Several MPs signalled that they are part of a local public, for instance, by using a local language in their speech (8), sometimes as simple as the greeting ‘bon dia’ (Wuite, 2021). This is what Young calls the ‘unmuting’ of previously marginalized languages and cultures. Leerdam opens his speech (2003) with a saying in Papiamentu, the lingua franca of the Dutch Antilles. As Papiamentu was not taught in schools until 2005, Leerdam's use of the language in parliament is highly symbolic. Asante (2016) refers to a local Ghanaian word for ‘the promised land’. Others refer to Dutch regional identities with specific words to indicate belonging to Limburg (such as Öztürk, 2013 and Amhaouch, 2016) or Frisia (De Hoop, 2021).

The third narrative strategy is understanding the experience of others and countering stereotypes. In the aftermath of 9/11, Azough (2002) aims to counter the idea that all Muslims think alike. Several MPs speak up against stigmas, for instance:

As a child of guest workers and as a child in Dutch society, I was brought up with the idea that integration is the way to go to become part of Dutch society. The ethnicization of people – to reduce their identity to their descent – I have always found terrible. I have also sometimes been stigmatized for my origins. I come from Harderwijk [a provincial Dutch city]. (Belhaj, 2016)

Finally, narratives can be used to unveil the source of values. Several MPs refer to family values such as seizing opportunities, mainly in education. Amhaouch (2016) connects his personal story to his current working mentality:

My father came to the Netherlands in 1963 as a Moroccan guest worker. Today, that is sort of a synonym for economic refugee, but by invitation! He loved to work, and did, right up to his well‐deserved retirement. (…) This mentality of working together, with all kinds of different people and organizations, has always appealed to me and continues to give me energy.

Family stories are used by new MPs to show where they come from. Kuzu (2012) recounts how as a small boy he used to translate between Turkish and Dutch for his parents, neighbours and acquaintances during visits to doctors, hospitals, schools, or the city hall. Ceder (2021) connects his passion for the rights of youths to a difficult period in his childhood when he could not live with his parents. The message is that he knows what these young people are going through. Several MPs use their stories to emphasize how they are role models:

I am telling this to indicate that, despite the fact that I came to the Netherlands at a later age, I have taken my responsibility. In this way, I hope to be an example for many with a different ethnic origin. I want to show that the Netherlands gives people who want to go further space and offers opportunities. It is people's job to take advantage of those opportunities. It is not only about taking responsibility, but also about bearing responsibility. (Eski, 2002)

The maiden speeches referred to historical figures as sources of ideological inspiration, spanning civil rights leader Martin Luther King (Tjon‐A‐Ten, 2003), guerrilla leader Ernesto Che Guevara (Alkaya, 2018), U.S. presidents John F. Kennedy (Çegerek, 2014), Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Gündoğan, 2021), people who have fought for freedom of speech, women's rights and heroes of the resistance in World War Two (Ellian, 2021). In two speeches, MPs referred to their Dutch political heroes such as the founding fathers of mainstream parties (Çelik, 2010; Boulakjar, 2021) or the social democratic feminist icon Corry Tendeloo (Çegerek, 2014). Wuite (2021) refers to the first Councillor of State for Sint‐Maarten, Maria Platz. Finally, one MP referred to the novel The Kite Runner by immigrant‐origin novelist Khaled Hosseini (Gündoğan, 2021), while another paraphrased the bible (Vos, 2007).

Finally, Simons uses all four strategies. Over the past years, Simons has developed a profile as an explicitly intersectional feminist and anti‐racist in the mainstream media, on social media and in activism. Her election as the first Black woman party leader in parliament has garnered massive attention. To address stereotypes and exclusion that stick across generations, Simons uses her family history to remind the public of Dutch colonial history and involvement in the slave trade:

Here stands a proud woman, a woman who has already overcome a lot in life. Born in the colony, where my mother's grandmother was still employed as a slave. And then the crossing [of the Atlantic Ocean], as a toddler, to a motherland, where, despite my Dutch passport, which I was given at birth, I never seem to belong. During my life, I have already been an official foreigner, fellow countryman, new Dutchman and immigrant. Or, this was also very popular: ‘exotic’. Generational exclusion that even my beautiful grandchild will carry on her shoulders. After all, her grandmother was not born in the Netherlands. (2021)

Simons narrates that she became a single mother at the age of 21. She uses this story to share her sympathy and rage with victims over an issue involving childcare allowances over which the ruling government resigned in 2021. The tax office administering these allowances specifically targeted ethnic minorities.

In sum, in the in‐depth narrative analyses, we find all four of Young's strategies. The strategy ‘responding to the differend’ is used by MPs from groups experiencing structural racism. But while some do so to focus on their individual perseverance, others do so to criticize exclusion. This seems to be related to party ideology, with conservative MPs emphasizing individual responsibility and progressive MPs being more critical of social structures. The strategy ‘facilitation of local publics and the articulation of collective affinities’ is used by MPs to emphasize symbolic messages, that they are in parliament to represent that particular group, albeit taking pains to emphasize that they also represent the broader Dutch public. The strategy to increase ‘understanding the experience of others and countering stereotypes’ is mainly used by MPs addressing Islamophobia to explain to the dominant group how ethnic minority citizens experience social stigma. The strategy to ‘unveil the source of values’ was most popular. Here, ethnic minority MPs rely on a spectrum of historical figures and symbols to elaborate on their substantive ideas. Finally, only one MP who explicitly represents intersectional politics – descriptively, symbolically and substantively – applies all strategies. Given the small numbers, these findings should be seen as the first qualitative exploration to be tested in future research.

Conclusion

Political narratives offer MPs opportunities to represent their individual and collective identities. Nevertheless, maiden speeches and other kinds of political narratives (e.g., autobiographies and blogposts) remain empirically under‐studied in the scholarship on political representation. Political narratives illustrate that descriptive representation does not only entail visible characteristics but also shared experiences – an essential tool for politicians from historically disadvantaged groups to convince members of dominant groups that their perspectives or insights are widely shared (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999). At the same time, it is a way to show members of disadvantaged groups that they are role models, that they too belong in politics and that they are ready to take up issues that have been neglected by dominant‐group MPs. The maiden speech is a more significant moment for ethnic minority MPs than for MPs from dominant groups. As ‘space invaders’ (Puwar, Reference Puwar2004), ethnic minority MPs are hyper‐visible and their decisions to (not) refer to identity are highly consequential.

Our in‐depth exploration of 88 maiden speeches over 35 years shows that the explicit representation of minority identities fluctuates and that organizational context matters. Our descriptive exploration shows that the ‘first’ of a particular intersectional group less often emphasizes an (intersectional) minority identity. The presence of ‘firsts’ pave the way for those who follow, the first step in normalizing the presence of people deemed to be ‘like them’. The penalties imposed by the dominant group – accusations of ethnic or gender clientelism or tokenism – might be lower later in time. In line with the legislative literature, we find that minority MPs representing progressive parties (often with diversity networks) more often narrate a minority identity than MPs representing conservative parties.

Our analysis of maiden speeches sheds new light on the blurry lines between different forms of representation (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967). Descriptive characteristics and shared experiences play an important role in political narratives: substantive promises may be made, and the speech itself has symbolic significance for the social groups that feel represented by the MP. The focus on what kinds of identity MPs themselves foreground before their work formally begins offers a new lens to study the relation between descriptive, substantive and symbolic representation. The in‐depth reading of all speeches shows that ethnic minority MPs often use their family stories to counter negative images about particular ethnic groups through human and humble stories. While ethnic minority MPs represent ‘different’ backgrounds, they particularly emphasized feelings of belonging to the Netherlands, seemingly to state that despite their different‐looking bodies, names or migration histories, they are Dutch MPs with clear substantive messages. Towards this end, they used personal experiences, family histories, local languages and dialects or references to historical figures, writings and literature, either Dutch, from their (ancestral) homeland, or a combination thereof. Through political narratives, they sought to familiarize citizens with the world of the ‘unknown’, using their experiences to show that their migration stories are also Dutch stories – as well as how being categorized as different has fuelled their dreams and ambitions for their political work. Ethnic minority MPs strategically use political narratives to respond to injustice, unmute local and silenced cultures, counter stereotypes and share values that may be unknown to the majority. Few ethnic minority MPs represented an intersectional identity. A possible explanation is that women ethnic minority MPs are more hyper‐visible than their male colleagues and may fear future penalties.

The 2021 elections in the Netherlands witnessed a sea change. Never before had ethnic minority candidates been so vocal during the election campaign about structural racism and exclusion in politics and society. The number of ethnic minority MPs as well as the number of maiden speeches referring to minority identities was never so high, apparently inspired by international activism including the Black Lives Matter and intersectional feminist movements. Most recently elected minority MPs also actively use social media to show snippets from their maiden speeches. Both developments are not confined to the Netherlands. Future research could combine maiden speeches with other forms of political narratives advanced by politicians such as their social media, autobiographies or web presence. Future work should try to better understand the consequences of these developments for the political representation of groups that have been politically subordinated in advanced democracies – how they are able to get out there and define themselves.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Takeo David Hymans for editing the manuscript with great care. Liza Mügge's research is supported by a Dutch Research Council (NWO) VIDI grant [grant number: 016.Vidi.175.355]. Early chunks of the paper have been developed and written during her residential stays at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences ‐ NIAS (2016–2017) and the Social Science Center Berlin ‐ WZB (2020–2021 Alexander von Humboldt Fellow).

Data availability statement

Full transcripts of maiden speeches between 1986‐1994 can be collected from the public digital archive Staten‐Generaal Digitaal: http://www.statengeneraaldigitaal.nl/

Speeches from 1995 onwards can be retrieved from the public databases https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/ and https://www.tweedekamer.nl

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix 1: Countries in sample of ‘ethnic minority MPs’.

Appendix 2: All MPs under study, available with authors.

Appendix 3: Longlist of identities mentioned in speeches.

Appendix 4: Codebook.

Appendix 5: Representation of gender identity by ethnic minority MPs.

Appendix 6: Overview of quotes of minority identity (in Dutch with English translation).