Approximately 354 000 people were homeless on a given night in England in 2024, including 322 000 in temporary accommodation and 3900 who were ‘sleeping rough’. 1 The number of people who are homeless is increasing, due to growing challenges related to limited housing and widening economic insecurity. 2 It has been recognised that the physical and mental health of people who are homeless is poorer than that of those who are stably housed. Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel3 A global review of homeless people Reference Ayano, Belete, Duko, Tsegay and Dachew4 found that 47% report symptoms of depression, and between 11 and 26% have major depression or major depressive disorder; other reviews in high-income settings Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes5,Reference Gutwinski, Schreiter, Deutscher and Fazel6 estimated prevalence figures of 11 and 12% for major depression. In the UK, a psychiatric survey of homeless people that was conducted in 1994 Reference Gill, Meltzer and Hinds7 estimated that the prevalence of depression or general anxiety disorder was 36%. In the Homeless Health Needs Audit report of 2022, over 60% of participants reported having depression or an anxiety disorder; Reference Hertzberg and Boobis8 in comparison, only 14% of adults living in private households had these conditions according to a national survey conducted in 1993, and 17% in 2014. Reference McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha9

Medical and social implications of depression and anxiety among people who are homeless

Depression and anxiety can lead to disabling symptoms such as lack of motivation, energy and concentration, and chronic and excessive worry, which impair access to healthcare. Limited access to healthcare is exacerbated by high need, because those affected by depression or anxiety are more likely to experience the incidence, persistence and recurrence of other physical, mental and substance use conditions, Reference Grenard, Munjas, Adams, Suttorp, Maglione and McGlynn10 and to attempt suicide. Reference Lee, Jun, Kim, Roh, Moon and Bukonda11 For homeless persons, access to health- and social care for the aforementioned conditions is hindered by stigma, discrimination and other intersecting domains of social exclusion, resulting in inequitable health outcomes: in England and Wales in 2021, the mean age at death was 45 and 43 years for homeless men and women, respectively, 12 and homeless persons have standardised mortality ratios that are 2–5 times higher than those of the general population. Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel3

Epidemiologic evidence around depression and anxiety among people who are homeless

Evidence from systematic reviews on mental health among adults who are homeless Reference Ayano, Belete, Duko, Tsegay and Dachew4–Reference Gutwinski, Schreiter, Deutscher and Fazel6 is predominantly drawn from studies conducted in the USA, where the homeless population has distinct challenges including the high cost and poor availability of health- and social care. There is limited peer-reviewed evidence to inform health- and social care around depression or anxiety for homeless adults in the UK, where psychological care for depression and anxiety is available and free at the point of use but is not necessarily accessible (e.g. due to barriers with registration, opening hours, appointment booking systems, etc.). For evidence about depression, an association was found between dental problems and depression among 853 homeless adults in Scotland. Reference Gill, Meltzer and Hinds7 Among patients of a specialist homelessness primary care centre in England, some 34% had depression and 23% had anxiety, which were associated with 1.8 and 2.3 times higher odds of non-fatal overdose, respectively. Reference Anderson, Kurmi, Lowrie, Araf and Paudyal13 Evidence on anxiety is more limited: in one study of young people (16–24 years) in temporary supported accommodation, 19% had generalised anxiety disorder, which was associated with a 2.8-fold increase in emergency department use. Reference Hodgson, Shelton and van den14 A cluster analysis of 452 homeless adults Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen15 found that those who had experience of being ‘very depressed or anxious’ clustered with those who had more complex and severe experiences of social exclusion and, furthermore, that symptoms tended to precede the exclusion.

With the population of homeless adults in England projected to increase, and access to healthcare – and, more specifically, to mental healthcare – remaining constrained, it is essential to characterise more fully the epidemiologic features of depression and anxiety, so that policy and research programmes can be prioritised appropriately.

Method

Setting/context

This study was undertaken in London, UK, where in 2024 an estimated 184 000 people were homeless, just over half of whom were adults. 1 In England everyone is entitled to free primary and emergency healthcare through the National Health Service, regardless of residency status. For those with symptoms of depression or anxiety, self-referral to self-guided therapy is available while a GP can refer patients to talking therapy, opt for watchful waiting, prescribe medication or refer to mental health specialists. In addition to these services, people who are homeless can choose to register at a GP surgery that specialises in homeless healthcare, where available, and those staying in hostels may be able to access talking therapy through hostel-based counsellors. GPs and key workers can refer people with drug or alcohol dependency, or psychosis, directly to specialist mental healthcare, where comorbid depression or anxiety can be treated. While such entitlements are legally mandated, there are frequently a range of barriers to the availability and uptake of mental healthcare. These barriers include long wait lists; logistical and administrative challenges; past experiences of discrimination; lack of confidence; as well as low prioritisation of healthcare amid competing priorities of survival.

Study procedures

This secondary analysis draws on data from an evaluation of a non-governmental organisation-delivered peer advocacy programme to improve access to healthcare, the methods for which have been reported in detail. Reference Rathod, Guise, Annand, Hosseini, Williamson and Miners16 Briefly, we recruited two cohorts from the same source population: adults experiencing homelessness in London and who had difficulty accessing healthcare. We recruited these cohorts concurrently between August and December 2021 and followed up for 12 months. The first cohort (‘clients’) were adults (≥25 years), homeless (e.g. sleeping rough, living in a hostel or shelter, in supported housing or with insecure private housing, etc.) in London, had difficulty accessing healthcare and were receiving support – whether new or ongoing – from the peer advocacy programme. Peer advocates – all of whom had lived experience of homelessness – recruited their clients into the cohort as part of their usual client engagement activities, with the understanding that consent or denial to the research would not affect the clients’ access to either the intervention or healthcare. For the second cohort (‘non-clients’), we recruited adults from hostels and day centres in London where the peer advocacy programme was not commissioned to work, and who either self-affirmed or had a key worker affirm their difficulty in accessing healthcare. A team of co-researchers – with experience of homelessness themselves or of working with homeless people – approached potential participants at these sites, explained the aims of the study and assessed them for eligibility. All participants who gave consent completed a 30 min structured questionnaire that could be either self- or interviewer-administered on a tablet device in either English or Polish. The questionnaire contained sections in three domains: (a) sociodemographic (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity); (b) social vulnerability (e.g. multiple-exclusion homelessness, Reference Fitzpatrick, Johnsen and White17 food insecurity, history of incarceration and trauma); and (c) health (e.g. current conditions, barriers to care, drug and alcohol use and depression and anxiety symptoms).

Study outcome

We used the 4-item PHQ-4, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe18 which uses a 4-point Likert scale for depression- and anxiety-related symptoms, with scores ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (nearly every day in the past 2 weeks). Because depression and anxiety are frequently comorbid and are increasingly considered to be a single psychological construct, and recognising the dimensional nature of mental health, most of our analyses used the sum of the 4 PHQ-4 items, a continuous measure (range 0–12) which, in this sample, had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83. We also created scoring categories of 0–5, 6–8 (‘yellow flag’) and 9–12 (‘red flag’), which were cut points suggested by Löwe et al Reference Löwe, Wahl, Rose, Spitzer, Glaesmer and Wingenfeld19 as indicators for clinical attention.

Other study measures

We measured age in years and grouped in 10-year intervals from 25. Participants could select one or more ethnic backgrounds (i.e. White, Asian, Black, Arab, Hispanic, other); we classified those who identified as White only, Black only and Asian only into their own categories, and the remainder (multiple ethnicity, other, decline to answer) into another category. We asked participants the age at which they first became homeless, subtracted that from their current age and created a category of <2 years to classify those who had recently become homeless, then divided the remaining participants into approximately equal-sized groups for 2–9, 10–24 and ≥25 years since first becoming homeless. For drinking frequency in the past 12 months, we re-categorised 9 frequency categories into 4: never, infrequent (up to a few times per year), frequent (a few times per month) and daily (5 or more days per week). For English literacy, we classified those who reported having below average ability in either reading or writing as having lower literacy. We included an 11-item tool to measure social vulnerability and exclusion characteristics for homeless persons. Reference Fitzpatrick, Johnsen and White17 Participants who affirmed going hungry because they could not afford food in the past 12 months were classified as food insecure. We asked questions about violence using items drawn from the World Health Organization multi-country study on domestic violence, Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts20 with recall periods of <6 and ≥6 months ago; those participants who reported ever having been pushed, shoved or slapped were classified as having physical abuse; ever having been belittled, humiliated or called racist names as verbal abuse; and ever having been touched, grabbed or forced sexually as sexual abuse. We asked participants about their non-prescription drug use in the past 12 months, and whether they used each of the drugs daily or less frequently. Those who had a PHQ-4 score of ≥9 and who daily used a substance (i.e. alcohol, cocaine, heroin, marijuana or spice) were classified as having a probable dual diagnosis.

Ethics

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by Dulwich Research Ethics Committee (no. IRAS 271312) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (ref. 18021), both based in the UK. All participants provided written informed consent and were reimbursed £10 (cash or grocery voucher) for their time and offered a copy of The Pavement magazine, which includes a listing of services for homeless people in London.

Statistical analysis

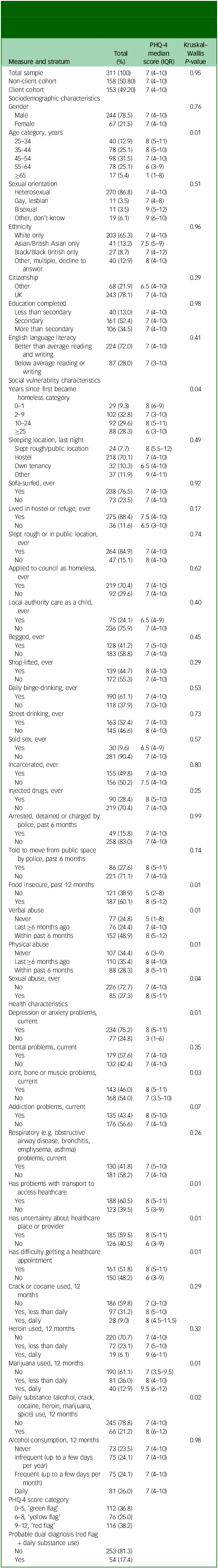

First we tabulated the sociodemographic, social vulnerability- and health-related characteristics of participants using proportions. To maintain confidentiality, we combined strata with <10 observations with other strata, if appropriate, or did not tabulate their findings. For large ‘choose all that apply’ question sets (e.g. ongoing health issues), we present the three to four most affirmed responses only. Second, we describe the sum of PHQ-4 scores using the median and interquartile range (IQR). We report the proportions with yellow and red flag PHQ-4 scores. Third, we report the median PHQ-4 score and IQR across each of the socioeconomic, social vulnerability- and health-related characteristics. Fourth, we consider evidence of association of these characteristics with PHQ-4. We could not use parametric tests such as the t-test or analysis of variance to test for associations because the PHQ-4 scores were skewed, and so we used the Kruskal–Wallis test, a non-parametric test, to compare the distribution of a continuous variable across two or more categories. As a descriptive analysis, our aim was to characterise, not to confirm, associations, and so we did not make adjustment for multiple testing. We used StataSE 18.0 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA; www.stata.com) for this analysis (see supplementary file available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10956). Fifth, we repeated steps 3 and 4 and tabulated results for the PHQ-4 symptom subscales for depression (PHQ2) and that for anxiety (GAD2). Finally, we conducted post hoc, pairwise comparisons of the categories from those measures with evidence of association in step 4, again with no adjustment for multiple testing.

Results

We recruited 311 participants, of whom 153 were peer advocacy clients and 158 non-clients. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Among all participants, 78.5% identified as male and 21.5% as female. Three participants identified as transgender and are not tabulated here. The median age was 48 years (IQR 40–57, not tabulated). The majority of participants were heterosexual (86.8%), identified as being of White ethnicity (65.3%), were UK citizens (78.1%), had completed only secondary school (52.4%) and had been sleeping in a hostel the previous night (70.1%). Notable proportions of participants had experienced verbal (49.8%) or physical (28.8%) abuse in the past 6 months, or sexual abuse in their lifetime (27.3%). The most common self-reported health problems were depression (75.2%), dental (57.6), joint, bone or muscle (46.0%), addiction (43.4%) and respiratory (41.8%), and 60.5% reported having problems with transportation to access healthcare. Using suggested cut points to guide clinical practice, Reference Löwe, Wahl, Rose, Spitzer, Glaesmer and Wingenfeld19 38.2% had red flag PHQ-4 scores of 9–12 and a further 25.0% had yellow flag scores of 6–8; 7 participants (2.2%) did not respond to at least 1 item of PHQ-4 and were not included in further analyses.

Table 1 Sociodemographic, social exclusion and health-related characteristics, and their association with PHQ-4 scores, among homeless health peer advocacy evaluation cohort participants, London, UK, 2020–2021

PHQ-4, 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire; IQR, interquartile range.

The overall median PHQ-4 score was 7, with IQR of 4–10. Both male and female participants had a median PHQ-4 score of 7, with IQR of 4–10, and there was no evidence of a difference in these distributions (Kruskal–Wallis, P = 0.76). There was evidence of an association of PHQ-4 score with age, in that scores were highest among younger participants (median 8) and lower among older participants (median 1). Scores were highest among those whose first episode of homelessness occurred in the past year (median 8), and lowest among those who were first homeless over 25 years ago (median 6). People who reported food insecurity had higher scores (median 8) than those who were food secure (median 5). Recent or historic experiences of physical, verbal and sexual abuse were all associated with higher PHQ-4 scores (all P < 0.05). Those who had joint, bone or muscle problems had higher scores (median 8) than those who did not (median 7). The three most common barriers to healthcare were all associated with higher scores: for example, participants who identified transportation as a barrier had a median score of 8, compared with a median of 5 for those who did not. Those who used marijuana daily had higher scores (median 9.5) than those who did not (median 7). There was no evidence of difference in PHQ-4 scores across crack/cocaine, heroin or alcohol consumption categories (all P > 0.29). The results for analyses of the PHQ2 depression symptom subscale are reported in Supplementary Table 2, for the GAD2 anxiety symptom subscale in Supplementary Table 3 and post hoc pairwise testing of PHQ-4 in Supplementary Table 4.

Discussion

Key findings

Among homeless adults who reported issues accessing healthcare, depression and anxiety symptoms were high, with a median PHQ-4 score of 7 out of 12, and 38% having red flag scores warranting clinical attention. Awareness of these conditions by name was also high: over 75% of participants affirmed having ongoing problems with ‘depression or anxiety’. While PHQ-4 scores were consistently high across participant characteristics, there was evidence that these were higher among younger people, those using marijuana daily, those who had transportation problems and those who had joint, bone or muscle problems. In addition, almost 2 in 3 participants had experienced hunger in the past 12 months, 1 in 2 had experienced verbal abuse in the past 6 months and 1 in 3 had experienced sexual abuse in their lifetime.

Burden of symptoms and coverage of care

The depression and anxiety symptom levels observed in this sample are far higher than those found in previous meta-analyses of homeless populations, Reference Ayano, Belete, Duko, Tsegay and Dachew4–Reference Gutwinski, Schreiter, Deutscher and Fazel6 and are probably an artefact of a study inclusion criterion: self-reported difficulty in accessing healthcare. For this population, reducing the burden of these conditions will require consideration of both their incidence and duration. Because insecure housing is evidenced as an incidence risk factor for a range of social and medical conditions, Reference Gallent21 action to improve housing security must remain a priority. To reduce duration, we need to develop more accessible forms of psychological support. For example, models of peer support interventions have been developed and demonstrated as being effective in improving mental health; Reference Smit, Miguel, Vrijsen, Groeneweg, Spijker and Cuijpers22 one peer-delivered model for substance use counselling among people who are homeless is currently being evaluated in the UK. Reference Parkes, Matheson, Carver, Foster, Budd and Liddell23

Associations with depression and anxiety symptoms

We observed higher PHQ-4 scores among younger age groups. This trend is consistent with one study from Taiwan Reference La Gory, Ritchey and Mullis24 and the opposite of another from the USA. Reference Wang, Lin, Chen, Wang and Lin25 We also observed higher scores among those who first became homeless recently. Two studies, Reference Flentje, Shumway, Wong and Riley26,Reference Riley, Dilworth, Satre, Silverberg, Neilands and Mangurian27 both from San Francisco, USA, found that recent homelessness was associated with depression and anxiety; in further analysis, these two measures were positively correlated. It is plausible that younger people had higher PHQ-4 scores because they had more recently became homeless, although it is also plausible that older participants had lower PHQ-4 scores due to survivor bias. Our findings support efforts to address the drivers of housing insecurity.

The lack of association here between sexual orientation and both depression and anxiety is contrary to findings from the general population in the UK, Reference Semlyen, King, Varney and Hagger-Johnson28 and among homeless people in the USA. Reference Flentje, Shumway, Wong and Riley26,Reference Rohde, Noell, Ochs and Seeley29,Reference Schick, Witte, Misedah, Benedict, Falk and Brown30 Overall, 11% of our sample identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or other – substantially higher than the 3% estimated from national population surveys in the UK Reference Semlyen, King, Varney and Hagger-Johnson28 but the same as that reported in the 2022 Homeless Health Needs Audit. Reference Hertzberg and Boobis8 The disproportionate representation of sexual minorities in the homeless population is well characterised Reference Fraser, Pierse, Chisholm and Cook31 and, given the lack of research on mental health among sexual minorities within the homeless population, we recommend further qualitative research and larger quantitative studies to consider whether there are protective factors for sexual minorities that are present in the UK and absent in other settings.

Around 6 in 10 of our participants had experienced hunger due to lack of funds in the past 12 months, reinforcing the 2022 Homeless Health Need Audit in England, Reference Hertzberg and Boobis8 which found that only 18% of respondents had an average of 3 meals per day. Participants who had experienced hunger had higher PHQ-4 scores than those who had not. Similar findings have been reported from Canada and the USA, Reference Riley, Dilworth, Satre, Silverberg, Neilands and Mangurian27,Reference Lachaud, Mejia-Lancheros, Wang, Wiens, Nisenbaum and Stergiopoulos32,Reference Palar, Kushel, Frongillo, Riley, Grede and Bangsberg33 with the cohort study from Palar et al Reference Palar, Kushel, Frongillo, Riley, Grede and Bangsberg33 finding that severe food insecurity precedes an increase in depression severity. These findings further support the need for a strengthening of social care services, so that social work teams can devote adequate time to help their clients navigate disparate services (i.e. for nutrition, housing, physical health and mental health), and can sensitise the relevant service providers to the intersecting vulnerabilities faced by their clients.

The use of drugs and alcohol to self-medicate against symptoms of mental distress has been well characterised in the general population, and has been reported from studies of homeless persons in the USA and France. Reference Fond, Tinland, Boucekine, Girard, Loubière and Boyer34,Reference Berg, Nyamathi, Christiani, Morisky and Leake35 In this study, we did not detect any associations among crack, heroin or alcohol use with PHQ-4 scores, although we did with marijuana. Building on the findings of Lowe et al, Reference Lowe, Sasiadek, Coles and George36 our findings support further research on whether cannabis use exacerbates physical health issues and depression symptoms, and whether the cognitive effects of cannabis might be related to some of the specific barriers to accessing healthcare (e.g. relating to transportation) reported by our participants. We observed that 1 in 5 participants was using a substance daily and that 17% had a probable dual diagnosis (e.g. high PHQ-4 score and daily substance use), evidencing a confluence of homelessness, substance use and mental distress. This finding should motivate further coordination between social and medical providers.

The high prevalence of verbal, physical and sexual abuse is consistent with review evidence Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel3 that estimates between 27 and 52% of homeless persons had experienced physical or sexual assault in the previous year. As evidenced both in the UK and internationally, Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen15,Reference Fond, Tinland, Boucekine, Girard, Loubière and Boyer34,Reference Tsai, Weiser, Dilworth, Shumway and Riley37–Reference Larney, Conroy, Mills, Burns and Teesson39 abuse is associated with depression and anxiety, and with other domains of social exclusion. Homeless service providers need to ensure that health and social services are informed by an understanding of, and sensitivity around, experience of violence and the role that this trauma might play in the lives and behaviours of service users. This understanding might include the development of organisational cultures that foster an understanding of how experiences of adversity may shape behaviour, and improvement in staff training around how to recognise and respond to the signs of trauma. Improving access to specialist trauma services for people experiencing homelessness is also key. Inclusion of those with lived experience of homelessness services as staff and volunteers could also facilitate systemic change, to better recognise and meet the needs of clients who face historic and ongoing abuse. Furthermore, these findings reinforce the need for integration of housing and mental health support for survivors of abuse.

Consistent with a study of people who are homeless in Los Angeles, USA, Reference Nyamathi, Branson, Idemundia, Reback, Shoptaw and Marfisee40 we found high levels of physical joint, bone or muscle problems associated with higher PHQ-4 scores. While somatic symptoms are common features of depression, these physical problems can sometimes be independent comorbidities. This finding highlights the need for integrated approaches to care, such that presentation with these common physical complaints is routinely accompanied by investigation into depression and anxiety and vice versa, and that clinical providers coordinate their care. We also note the high concordance of PHQ-4 scores with self-reported problems of depression and anxiety. The fact that participants with symptoms recognised their underlying conditions evidences an encouraging level of mental health literacy, upon which further interventions to improve access to care can build.

All participants in this analysis had difficulty accessing healthcare according to the eligibility criteria of the study; the most common barriers included problems with transportation, uncertainty about location and inability to get an appointment. These barriers were associated with higher PHQ-4 scores. We recommend that policy-makers consider removal of structural barriers to services, including those around accessing public transport, and of barriers to referrals within and between medical and social care sectors.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first descriptive analysis, using validated tools, of the distribution of depression and anxiety symptoms among any homeless population in the UK. Given emerging findings about peer support for the health of homeless people, we believe that our engagement with peers and co-researchers with lived experience of homelessness means that many of our participants were people who would otherwise be hesitant to participate in a research study, and were more likely to provide complete and accurate responses. We believe that this engagement resulted in less selection bias and less response bias. The high levels of affirmation to question items that are considered stigmatising (e.g. on abuse, substance use and mental health) evidences a level of trust to disclose to our co-researchers who, like peer advocates, have lived experience of homelessness. Our measure of depression and anxiety symptoms was PHQ-4, a subset of items drawn from PHQ9 and GAD7, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe18 which are well characterised and widely used to screen for depression and anxiety, respectively. For analysis, we used PHQ-4 as a continuous measure, which is consistent with the dimensional approach to mental health and avoids the clinical and measurement issues inherent in using a cut-off score to diagnose a mental health condition. There are several limitations of this analysis that must be noted. First, it is not possible to make causal interpretations for the associations detected here; our data are cross-sectional and temporality is not always clear. Second, no sampling frame exists for homeless people in London, nor could we recruit from all hostels and day centres in this city because we relied on cooperation from site managers. Furthermore, given the focus of the primary study from which this secondary analysis was drawn – about people who have difficulty accessing healthcare in London – our sample may be systematically different to the broader population of people who are homeless. And third, because some strata in this analysis were relatively small, our statistical power to detect modest variations in PHQ-4 scores was limited. While there were over 40 statistical tests run in the main analysis (Table 1), we did not make adjustments for multiple comparisons. Due to the risk of type 1 error (false positive) associated with multiple testing, readers should treat our findings as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10956

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from L.P. (lucy.platt@lshtm.ac.uk), upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the Study Steering Committee, including Alex Marshall and Louisa McDonald of Groundswell, Suzanne Fitzpatrick of Heriot-Watt University and Mark Lunt of Manchester University. We thank Jocelyn Elmes, Chrissy H. Roberts and Aubrey Ko of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM); Mani Cudjoe, Ozgur Gencalp, Martin Murphy and Kate Bowgett of Groundswell; our co-researchers Maame Esi Yankah, Keely Tarrant, Maya Palej, Michael ‘Spike’ Hudson, Adrian Godfrey, Khalid Hussain, Dena Pursell, Tasia Thompson, Mark Leonard, Benjamin Opene, Jacqueline Craine, Mhohn Bancyr de Angeli and Stephan Morrison; and our participants. Open Data Kit servers and support were provided by the LSHTM Global Health Analytics Group (https://opendatakit.lshtm.ac.uk/).

Author contributions

S.D.R. designed and conducted this analysis, collected data and wrote the article. P.A. contributed to drafting and interpretation of the article. P.H. carried out data collection and contributed to drafting the article. A.G. designed the broader study within which this analysis was conducted, and contributed to interpretation of this analysis and drafting the article. L.P. contributed to the broader study within which this analysis was conducted, collected data and contributed to interpretation of the analysis and drafting the article. All authors give final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research (PHR Project 17/44/40).

Declaration of Interest

None.

Transparency declaration

S.D.R. affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.