Introduction

Cover crops are increasingly employed as an integrated weed management tool given their ability to disrupt life-cycle transitions of annual weed species (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Lounsbury, Palmer, Korres, Travlos and Gitsopoulos2024; Teasdale Reference Teasdale and Zimdahl2018). Cover crop surface residues can produce meaningful levels of weed suppression at early crop growth stages, but two-pass herbicide programs are still needed to minimize reproductive output and population growth of problematic weed species (Loux et al. Reference Loux, Dobbels, Bradley, Johnson, Young, Spaunhorst, Norsworthy, Palhano and Steckel2017; Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, McClure, Hayes, Walker, Senseman and Steckel2018; Vollmer et al. Reference Vollmer, VanGessel, Johnson and Scott2020). Therefore, modification of cover crop management tactics to increase weed-suppression potential should also reflect how such tactics influence herbicide fate and weed control efficacy.

Previous studies have demonstrated that integrating cover crop surface residues with soil-residual herbicides can produce either synergistic or antagonistic effects on establishment of annual weeds (Teasdale et al. Reference Teasdale, Shelton, Sadeghi and Isensee2003, Reference Teasdale, Pillai and Collins2005). Synergistic effects can occur when the weed control efficacy of soil-residual herbicides is amplified in the presence of cover crop surface residues, thereby lowering the lethal dose needed to control emerging weed seedlings. For example, Teasdale et al. (Reference Teasdale, Pillai and Collins2005) demonstrated that the partitioning of resources to hypocotyl elongation by redroot pigweed (Amaranthus hybridus L.) and common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.) seedlings lowered the lethal dose of very-long-chain fatty-acid synthesis inhibitors (VLCFAs; Group 15). On the other hand, antagonism between these tactics may occur when the efficacy of residual herbicides is reduced in the presence of cover crop surface residues due to physical interference with herbicide deposition to soil (Teasdale et al. Reference Teasdale, Shelton, Sadeghi and Isensee2003).

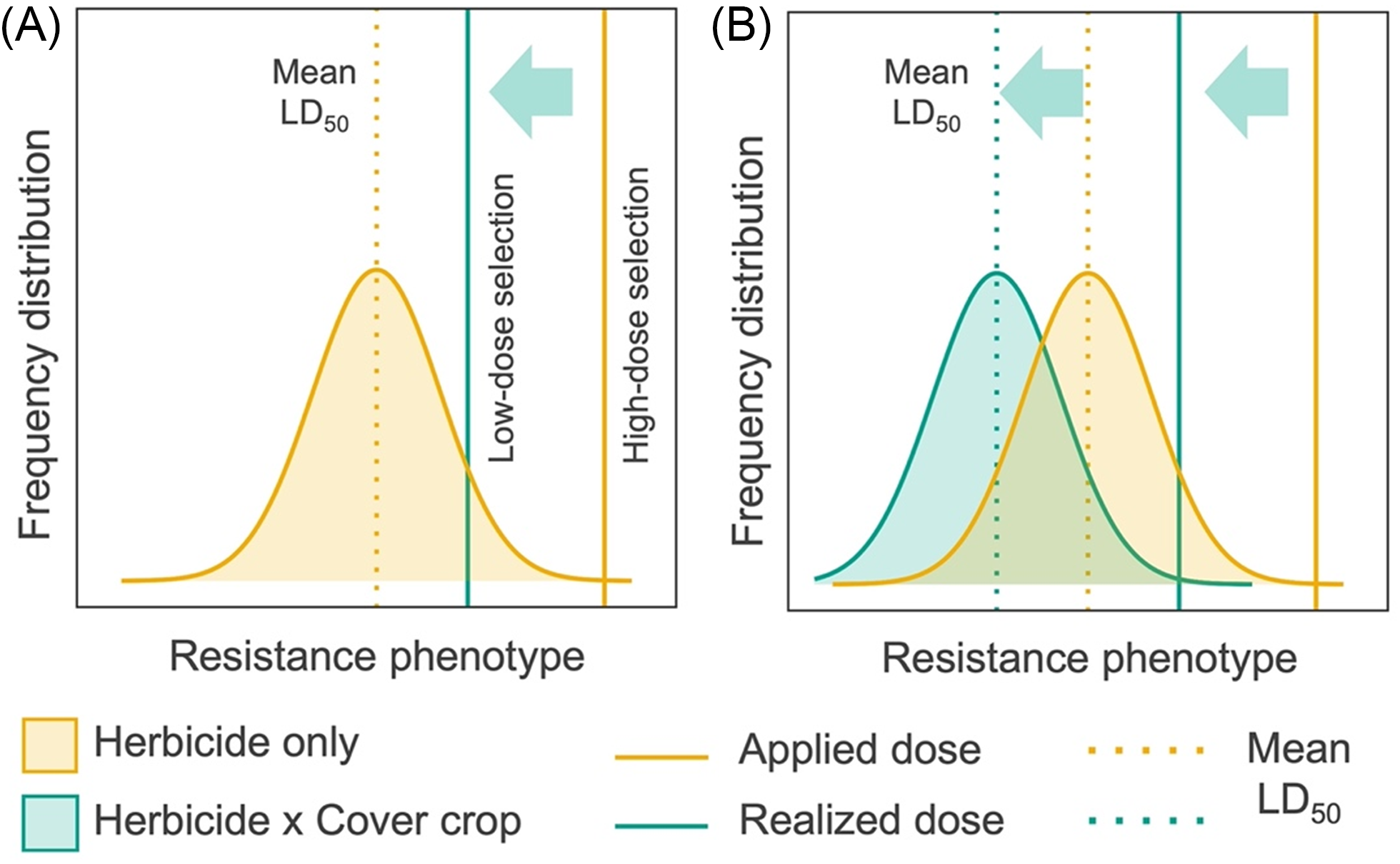

Understanding cover crop management effects on initial herbicide concentrations in soil is particularly important given that recurrent exposure to sublethal herbicide doses can select for phenotypes within standing genetic variation that survive labeled herbicide rates (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Varanasi, Bagavathiannan and Brabham2021; Tehranchian et al. Reference Tehranchian, Norsworthy, Powles, Bararpour, Bagavathiannan, Barber and Scott2017). A potential consequence of reduced deposition of soil-residual herbicides due to cover crop interference is greater exposure of weed phenotypes to sublethal concentrations, creating low-dose selection scenarios (Neve et al. Reference Neve, Busi, Renton and Vila-Aiub2014; Figure 1A). An alternative hypothesis is that a reduction in herbicide concentration due to cover crop residues is correlated with a reduction in the mean lethal dose (LD50) among phenotypes due to stresses imposed by cover crop residues and that the magnitude of these opposing effects is roughly proportional (Figure 1B). Designing proactive herbicide-resistance management strategies will require a more fundamental understanding of how cover crop management influences herbicide fate, including deposition and wash-off processes, which determine initial concentrations in soil.

Figure 1. Alternative hypotheses of herbicide selection when soil-residual herbicides are applied alone (yellow) or in combination with cover crop surface residues (green): (A) interference from cover crop surface residue lowers the realized herbicide dose, which increases the proportion of phenotypes exposed to a sublethal herbicide dose, resulting in low-dose selection; or (B) a reduction in the realized herbicide dose related to cover crop surface residues is correlated with a proportional reduction in the mean response (LD50) to herbicide selection due to joint effects of cover crop stressors at an individual scale. Hypotheses are based on conceptual model of low-dose herbicide selection described by Neve et al. (Reference Neve, Busi, Renton and Vila-Aiub2014).

Currently, there is increasing interest in enhancing weed-suppression potential from surface residues by delaying cover crop termination until after or at cash crop planting, often referred to as “planting green.” This practice can allow for greater biomass accumulation and improved weed suppression compared with the standard practice of terminating cover crops 10 to 21 days before planting (Ficks et al. Reference Ficks, Karsten and Wallace2023; Grint et al. Reference Grint, Arneson, Arriaga, DeWerff, Oliveira, Smith, Stoltenberg and Werle2022; Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Wallace, Arneson, Johnson, Young, Norsworthy, Ikley, Gage, Bradley, Jha, Lancaster, Kumar, Legleiter and Werle2024; Reed et al. Reference Reed, Karsten, Curran, Tooker and Duiker2019). Early adopters of planting green promote planting into living cover crops before terminating the cover crop to promote continuous living cover and target soil-moisture levels that improve planting conditions in wet springs. A common management scenario is a tank-mixed herbicide application made shortly after cash crop planting (1 to 5 days after planting (DAP)) that includes foliar-active herbicides to terminate cover crops and soil-residual herbicides to provide early-season weed control in a single pass.

The combination of increased cover crop biomass production and application of soil-residual herbicides into living cover crops in planting green systems may significantly affect herbicide deposition to the soil surface at the time of application. Recent studies have begun to quantify relationships between cover crop biomass and concentration of herbicides in soil across cover crop termination timings that create variable biomass levels (Maia et al. Reference Maia, Armstrong, Kladivko, Young and Johnson2025; Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Arneson, Wallace, Gage, Miller, Lancaster, Mueller and Werle2023a; Whalen et al. Reference Whalen, Shergill, Kinne, Bish and Bradley2020). However, there is less understanding of herbicide wash-off processes from living or aged cover crop residues, where a proportion of herbicide that is intercepted by cover crops at the time of application is transferred to the soil surface due to precipitation events.

Interactions between physiochemical properties of crop residues, herbicide lipophilicity, and the timing and amount of rainfall are known to mediate herbicide wash-off from crop residues (Alletto et al. Reference Alletto, Coquet, Benoit, Heddadj and Barriuso2010; Locke and Bryson Reference Locke and Bryson1997). Mass loss of crop residue is driven by decomposition of nonstructural carbohydrates and hemi-cellulose, which increases the ratio of lignin (Thapa et al. Reference Thapa, Tully, Reberg-Horton, Cabrera, Davis, Fleisher, Gaskin, Hitchcock, Poncet, Schomberg, Seehaver, Timlin and Mirsky2022). As the proportion of lignin increases in decaying crop residues, herbicide molecules have greater potential to become physically entrapped within cell wall structures, which reduces herbicide wash-off potential (Dao et al. Reference Dao1991; Reddy et al. Reference Reddy, Locke, Wagner, Zablotowicz, Gaston and Smeda1995).

Several herbicide modes of action commonly used to provide soil-residual activity contain active ingredients that also display foliar activity. When such herbicides are applied into a living cover crop, a proportion of intercepted spray will be unavailable for wash-off to the soil surface due to foliar uptake and translocation to their molecular targets (Krähmer et al. Reference Krähmer, Walter, Jeschke, Haaf, Baur and Evans2021). VLCFAs are nonpolar herbicides that provide only soil-residual activity but are readily absorbed across plant cuticles, which can limit wash-off potential (Krutz et al. Reference Krutz, Koger, Locke and Steinriede2007). Wash-off potential from foliage of living plants will likely differ based on the lipophilicity (log Kow) and acid strength (pKa) of herbicides, given their role in mediating diffusion or active transport across lipophilic membranes before entering into cells (Takano et al. Reference Takano, Patterson, Nissen, Dayan and Gaines2019).

In planting green systems, roller-crimpers are increasingly used to create a uniform surface mulch and improve cash crop establishment (Sias et al. Reference Sias, Bamber and Flessner2024; Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Mazzone and Larson2023). Roll-crimping before application of residual herbicides alters cover crop orientation and ground cover. Consequently, roll-crimping is likely to have direct effects on herbicide deposition and wash-off processes by changing ground cover and the composition of stem and leaves that comprise the exposed surface area of cover crops (Khalil et al. Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2020; Teasdale and Mohler Reference Teasdale and Mohler2000).

Cover crop species selection is also likely to mediate the relationship between cover crop biomass, herbicide deposition to soil, and wash-off from residues. Winter cereal cover crops are frequently used in sequence with soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], but grass–legume mixtures are often used to target multiple ecosystem services preceding corn (Zea mays L.) in rotation (Finney et al. Reference Finney, White and Kaye2016; Schipanski et al. Reference Schipanski, Barbercheck, Douglas, Finney, Haider, Kaye, Kemanian, Mortensen, Ryan, Tooker and White2014). Teasdale and Mohler (Reference Teasdale and Mohler2000) observed that legume cover crops had a greater mass area index compared with cereal rye (Secale cereale L.) due to greater surface area per unit of biomass, which resulted in less light penetration through the cover crop canopy to the soil surface compared with cereal rye for a given unit of biomass. Light penetration through surface mulch is likely positively correlated with herbicide deposition, and thus we should expect to see differences among cover crop species based on growth habit and traits such as leaf area index. Legume cover crops or grass–legume mixtures are also likely to decompose faster than grass cover crops within early-season herbicide application windows because of lower C:N ratios. Differences in decomposition rate can affect the length of weed suppression (Pittman et al. Reference Pittman, Barney and Flessner2020). These differences may also decrease herbicide wash-off potential due to increased herbicide sorption capacity at more advanced decomposition stages.

In this study, we quantify soil-residual herbicide deposition and wash-off across varying cover crop and herbicide management scenarios to deepen understanding of the relationship between cover crop management tactics and initial concentrations of residual herbicides in soil. We limit our evaluations to the single herbicide active ingredient pyroxasulfone, because of its utility in preemergence and postemergence herbicide programs in both corn and soybean, and because interception and wash-off dynamics of pyroxasulfone from aged crop residues has been previously described (Khalil et al. Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2018a, Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2019, Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2020). Our primary objective was to quantify the relative effects of cover crop biomass, physiochemical property (living vs. aged residue, grass vs. grass–legume), and orientation (roll-crimped vs. standing) on (1) herbicide deposition to the soil surface at the time of application and (2) wash-off potential following rainfall events.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Locations

Field experiments were conducted at the Pennsylvania State University Russell E. Larson Agricultural Research Center (RELARC) near Rock Springs, PA, the University of Delaware’s Research and Education Center (UDREC) near Georgetown, DE, and the Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station (VAES) Kentland Farm near Blacksburg, VA, in the 2022 and 2023 growing season for a total of 6 site-years. Experimental sites differed in soil texture, including Hagerstown silt loam (fine, mixed, semiactive, mesic Typic Hapludalfs) at RELARC Hammonton loamy sand (coarse-loamy, siliceous, semiactive, mesic Aquic Hapludults) Ross loam (fine-loamy, mixed, super active, mesic Cumulic Hapludolls).

Experimental Design

Experiments were designed as a two-factor complete block and arranged in a split-plot treatment structure with four replicates. Treatments were randomized at the main and split-plot levels. Main plots were cover crop management tactic (CC) with six treatment levels and split plots were herbicide application timing with two treatment levels. Main plot size was 24 by 3 m and split plots were 12 by 3 m.

Cover crop management tactics differed by species selection, termination timing, and residue management. The six treatments included cereal rye terminated with glyphosate (Roundup PowerMax®, Bayer CropScience, St Louis, MO, USA) and left standing at the (1) flag-leaf stage (Zadoks 37–39; Zadoks et al. Reference Zadoks, Chang and Konzak1974); (2) heading stage (Zadoks 51–59); and (3) anthesis stage (Zadoks 65–69); and cover crops terminated with glyphosate after roll-crimping at the anthesis stage (Zadoks 65–69), including (4) a cereal rye monoculture; (5) a cereal rye and crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum L.) mixture; and (6) a cereal rye and hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth) mixture. Cereal rye was seeded at 67 kg ha−1 in monoculture treatments and at 33 kg ha−1 in legume mixtures. Hairy vetch and crimson clover were seeded at 33 kg ha−1. Split-plot treatments included the residual herbicide, pyroxasulfone (Zidua®, BASF, Florham Park, NJ, USA), applied (1) at cover crop termination (0 d after termination [DAT]) or (2) 21 d after cereal rye anthesis, simulating an early postemergence application.

Pyroxasulfone (0.15 kg ai ha−1) was used as the test residual herbicide treatment for two reasons. First, pyroxasulfone can be applied preemergence and early postemergence in both corn and soybean production. Second, pyroxasulfone is known to readily leach from crop residues (Khalil et al. Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2019) and dissipation due to photodegradation or volatilization is reported to be negligible (Shaner Reference Shaner2014). Pyroxasulfone was tank mixed with glyphosate (1.27 kg ai ha−1) and ammonium sulfate (AMS; 2.5% v/v) in 0 DAT and early postemergence treatments. For early postemergence split-plot treatments, glyphosate and AMS were applied without pyroxasulfone at the appropriate cereal rye termination stage (boot, heading, anthesis) in monoculture treatments and 2,4-D choline (0.56 kg ae ha−1) was included in the tank mix for legume mixtures. Roll-crimping in targeted treatments occurred before application of the test herbicide at the 0 DAT and before cover crop burndown applications (0 DAT) in early postemergence treatments.

At each location, cover crops were established in the fall preceding the experimental growing season using a 3.3-m no-till grain drill with 19-cm row spacing. No-till practices were used in the previous soybean crop. Roll-crimping was performed using either a front- or rear- mounted 3-m unit with a chevron pattern (I&J Manufacturing, Gordonville, PA, USA). A single pass in the hydraulic float position was used for treatments requiring roll-crimping.

petri Dish Assay

A bulk collection of soil cores was collected to a depth of 7.6 cm at each location from the experimental field in late spring before herbicide treatments. Soil cores were air-dried and passed through a 2-mm sieve. Using methods described by Khalil et al. (Reference Khalil, Siddique, Ward, Piggin, Bong, Nambiar and Trengove2018b, Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2019), we placed 50 g of dried and sieved soil into petri dishes (9-cm diameter, 1.5-cm depth) to create uniform soil conditions for field assays. Studies conducted by Khalil et al. (Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2019) used this petri dish configuration to measure pyroxasulfone wash-off under simulated rainfall regimes ranging from 5 to 20 mm in either onetime events or across multiple events. Our preliminary field studies showed negligible loss of soil from petri dishes as a result of observed rainfall events, although extreme high-rainfall intensity events not encountered in our studies would likely lead to soil loss.

At each herbicide application timing (0 DAT, early postemergence), two petri dishes were placed 0.75 m from the middle of the plot within two adjacent cover crop interrows. Location was selected based on uniformity and species composition of the stand. For early growth stages, a flag was used to denote petri dish placement to prevent foot traffic influencing assays at the time of herbicide application. Petri dishes were placed directly on the soil surface to simulate field surface conditions. Within approximately 1 h of petri dish placement, the residual herbicide treatment was applied using a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer and 3-m boom equipped with 51-cm nozzle spacing and 110015 AIXR (TeeJet®, Spraying Systems, Wheaton, IL, USA) nozzles, delivering a carrier rate of 140 L ha−1. Weather data were collected at each residual herbicide application timing, including the three cereal rye cover crop growth stages (flag leaf, heading, anthesis) application timings and the early postemergence timing (21 d after anthesis). A herbicide standard (STD) was created at each application timing and site-year by locating a petri dish in a fallow strip adjacent to each replicate block and applying pyroxasulfone. The STD was collected at the same time as CC treatment samples. Finally, an untreated (UTC) petri dish was then paired with STDs for analyses to determine background concentrations of pyroxasulfone in soil.

Cover crop residue was allowed to dry for 2 h after each application. Each pair of petri dishes was then collected and replaced with new petri dishes. The second pair of petri dishes were collected after the cumulation of 12.5 mm of rainfall, measured using rain gauges placed within each experimental location (Table 1). In pyroxasulfone bioassays, Khalil et al. (Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2019) found negligible differences in weed control between 5 and 20 mm of simulated rainfall, which was imposed to determine the effects of rainfall amount on wash-off of pyroxasulfone from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) residues.

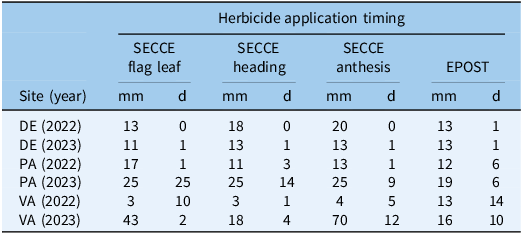

Table 1. Total cumulative precipitation (mm) and days (d) between placement and collection of wash-off petri dish assays by site-year and herbicide application timing a .

a Abbreviations: DE, Delaware; PA, Pennsylvania; VA, Virginia; SECCE, cereal rye (Secale cereale); EPOST, early postemergence application.

Cover crop biomass was then collected in the area of petri dish assays using a 65 by 38 cm quadrat, which encompassed three seeded rows and the two interrow spaces where petri dishes were placed. Cover crop biomass was oven-dried at 65 C for 5 to 7 d and weighed. Following their collection, petri dishes were paired and placed in freezer bags stored in a −7 C freezer to prevent microbial degradation.

Laboratory Analysis

Preliminary tests were conducted with known concentrations of pyroxasulfone mixed with soil from each location using different solvents (acetone, methanol) to observe differences in recovery rate (%). Of the solvents tested, acetone (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) optimized herbicide recovery. Following the completion of field assays, samples were removed from the freezer and allowed to thaw for 12 h, and paired samples (50 g) were homogenized (100 g). A 15-g subsample was placed in a weighed 50-ml Falcon tube, and the moist soil weight was recorded. Acetone (40 ml) was added to each Falcon tube, which was then placed on a shaker table overnight (14 h) to remove herbicide from the soil sample. A 1-ml sample was then extracted from each Falcon tube using a 0.45-µm filter syringe, placed in a glass vial that was capped and stored in a −7 C freezer. Falcon tubes containing the remaining solvent were stored until completion of the filtering, at which time they were placed in a fume hood to allow the solvent to evaporate. Dried soil was weighed and used to correct the sample dry weight in herbicide concentrate calculation.

Pyroxasulfone concentrations were quantified using a Dionex™ ICS-6000+ HPIC™ System (ThermoFisher, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) coupled with a Q Exactive Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher, Bremen, Germany) through heated electrospray ionization in positive ion mode (Supplementary Table 1). The limit of detection was 1 µg L−1, whereas the limit of quantification was 2 µg L−1. First- and second-order metabolites were not quantified.

Statistical Analysis

Pyroxasulfone concentration (ppb) measured in both deposition and wash-off samples was first expressed as a proportion of the STD at the block level to quantify the proportion of pyroxasulfone (1) deposited to the soil surface at the time of application (i.e., deposition) and (2) recovered after targeted rainfall (12.5 mm; i.e., wash-off). Deposition and wash-off proportions were then summed at the experimental unit level to quantify the proportion that was recovered from the combined processes (i.e., total soil concentration). In a limited number of cases in which cover crop biomass was low, total proportion recovered exceeded the STD. In these cases, experimental units were assigned a value of 0.99 to constrain proportion data to a 0 to 1 scale.

Log-normal models were fit to assess treatment effects on cover crop biomass (Mg ha−1) using the lmer package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Machler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (R Core Team 2022). Cover crop treatment (n = 6), residual herbicide application timing (n = 2), and their interaction were fit as fixed effects. Site-year (n = 5) and block nested in site year and main plot nested in block were fit as random effects.

Deposition, wash-off, and total recovery response variables were analyzed separately using generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) with a beta distribution (glmmTMB package; Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Kristensen, van Benthem, Magnusson, Berg, Nielsen, Skaug, Maechler and Bolker2017) in R (R Core Team 2022). Use of a beta distribution within GLMMs allow for analysis of continuous proportion data using the original scale, thereby producing less-biased estimates relative to transformation-based statistical approaches (Douma and Weedon Reference Douma and Weedon2019).

Two modeling approaches were used to assess treatment effects. First, cover crop treatment (n = 6), residual herbicide application timing (n = 2), and their interaction were fit as fixed effects, and site-year (n = 5) and block nested in site year and main plot nested in block were fit as random effects. We excluded VA22 from all models that focused on the relationship between deposition and wash-off processes due to limited precipitation following pyroxasulfone applications (Table 1). Next, data were subset by (1) treatments that included cereal rye monocultures that were left standing (n = 3) and (2) treatments that included cover crops roll-crimped at the cereal rye anthesis stage (n = 3). For each subset, we modeled cover crop biomass (Mg ha−1), application timing, and their interaction as fixed effects with a random site-year intercept term. For the roll-crimped subset, we included cover crop species as an additional covariate, including two- and three-way interaction terms. Random effects were reduced to site-year as the sole blocking factor to allow for fitting of both random intercept and random slope and intercept terms. Model comparisons (Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)) indicated that random intercept–only models were more parsimonious.

The significance of fixed effects in all models was evaluated using log-likelihood ratio tests (Wald χ2) to compare full versus reduced models using the anova function. Post hoc comparisons at either the main effect or two-way interaction level were conducted for the ANOVA model that specified cover crop treatments as categorical data by employing Tukey’s contrasts in the emmeans function (Lenth Reference Lenth2019). Post hoc orthogonal contrasts were also used to compare treatments of interest. Model fit of beta-regression models was assessed using the marginal (R2 m) and conditional (R2 c) coefficient of determination, which quantifies the amount of variance explained by fixed (R2 m) and fixed plus random components (R2 c) of mixed-effects models (Nakagawa and Schielzeth Reference Nakagawa and Schielzeth2013). Variance explained by predictor variables within the fixed component was also partitioned into inclusive R2 statistics using the partR2 package (Stoffel et al. Reference Stoffel, Nakagawa and Schielzeth2021). Inclusive R2 quantifies the total proportion of variance explained for a given predictor variable, including variance explained jointly with other predictors (Stoffel et al. Reference Stoffel, Nakagawa and Schielzeth2021).

Results and Discussion

Cover Crop Performance

Mean cover crop biomass at the time of pyroxasulfone applications differed among cover crop treatments (χ2 = 78; P < 0.001), ranging from 2.6 to 4.8 Mg ha−1 when averaged across site-years and application timing. Herbicide application timing also influenced cover crop biomass production (χ2 = 25; P < 0.001). Mean biomass was 3.5 Mg ha−1 in early postemergence treatments compared with 4.2 Mg ha−1 in 0 DAT treatments, or approximately 17% mass loss, when averaged across site-years and cover crop treatments. Imposed treatments explained a smaller proportion of variation in cover crop biomass (R2 m = 0.17) than variation among site-year and replicate blocks within site-year (R2 c = 0.71).

Deposition and Total Herbicide Recovery

Cover crop management affected deposition (χ2 = 64; P < 0.001) and total recovery (χ2 = 40; P < 0.001) of pyroxasulfone (Table 2). Herbicide application timing did not affect deposition but did have a marginal effect on total pyroxasulfone recovery (χ2 = 3.5; P = 0.06). Recovery was greater in early postemergence treatments compared with 0 DAT. Among orthogonal contrasts of interest, standing cover crops resulted in greater deposition (z = 7.2; P < 0.001) and total recovery (z = 5.8; P < 0.001) compared with roll-crimped cover crops. Application of pyroxasulfone into standing cereal rye at the anthesis stage resulted in greater deposition (z = 2.0; P = 0.04) than roll-crimped crimped cereal rye, but total recovery did not differ. Imposed treatments explained a smaller proportion of variation in total recovery of pyroxasulfone (R2 m = 0.28) compared with variation among site-years and replicate blocks within site-year (R2 c = 0.64).

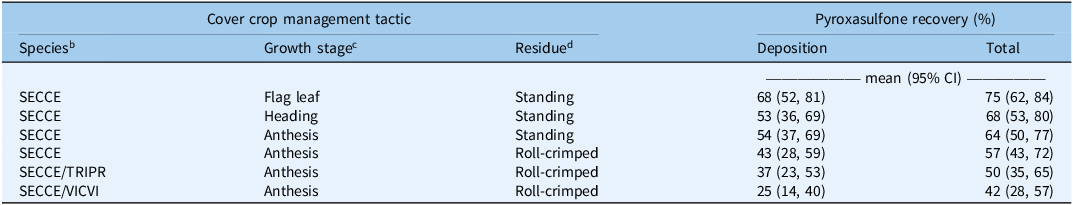

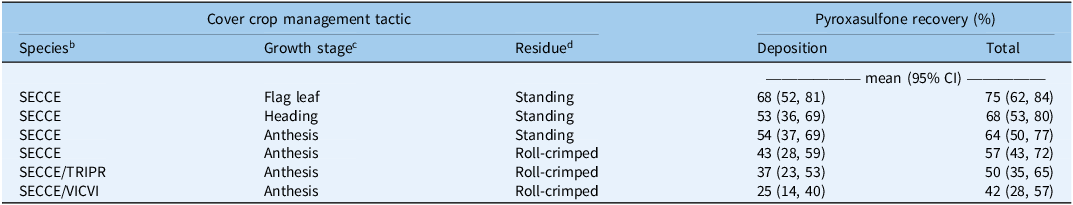

Table 2. Effect of cover crop management tactic on deposition and total recovery a .

a Data are estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and pooled across application timing and site-years.

b Species: SECCE, cereal rye (Secale cereale); TRIPR, crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum L.); VICVI, hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth).

c Cereal rye growth stage at time of cover crop termination.

d Cover crop residue management tactic.

Deposition and Wash-Off in Standing Cereal Rye

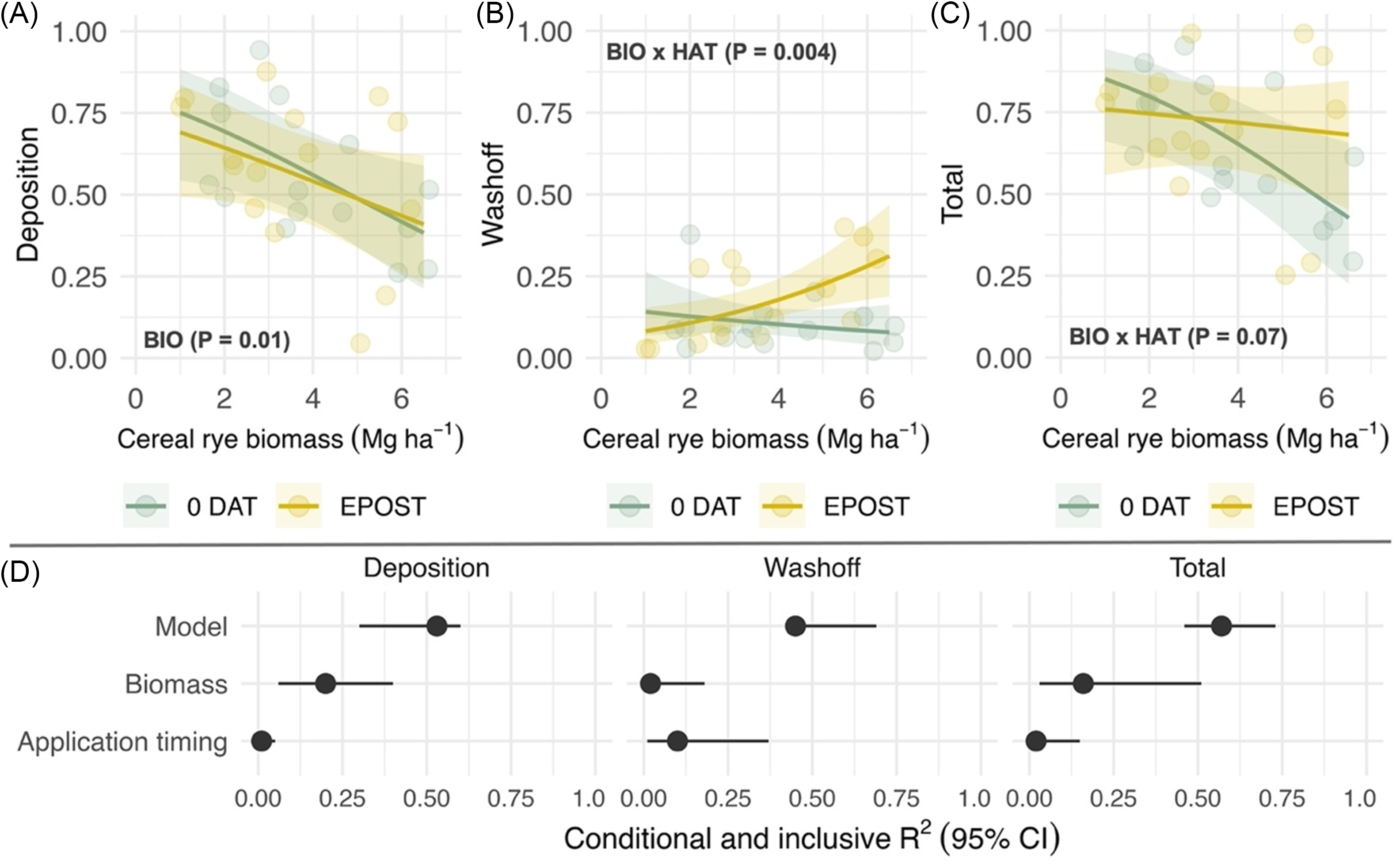

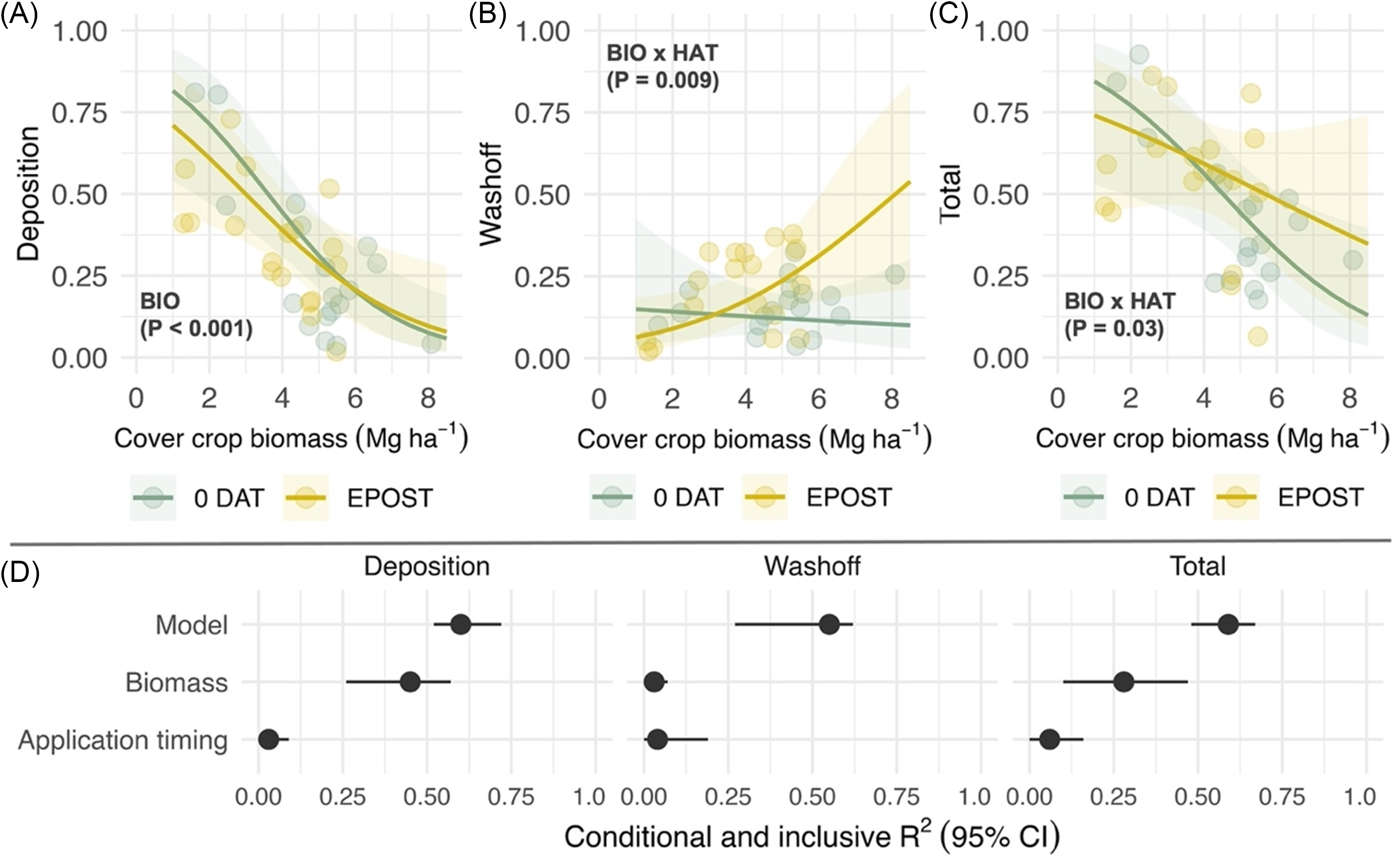

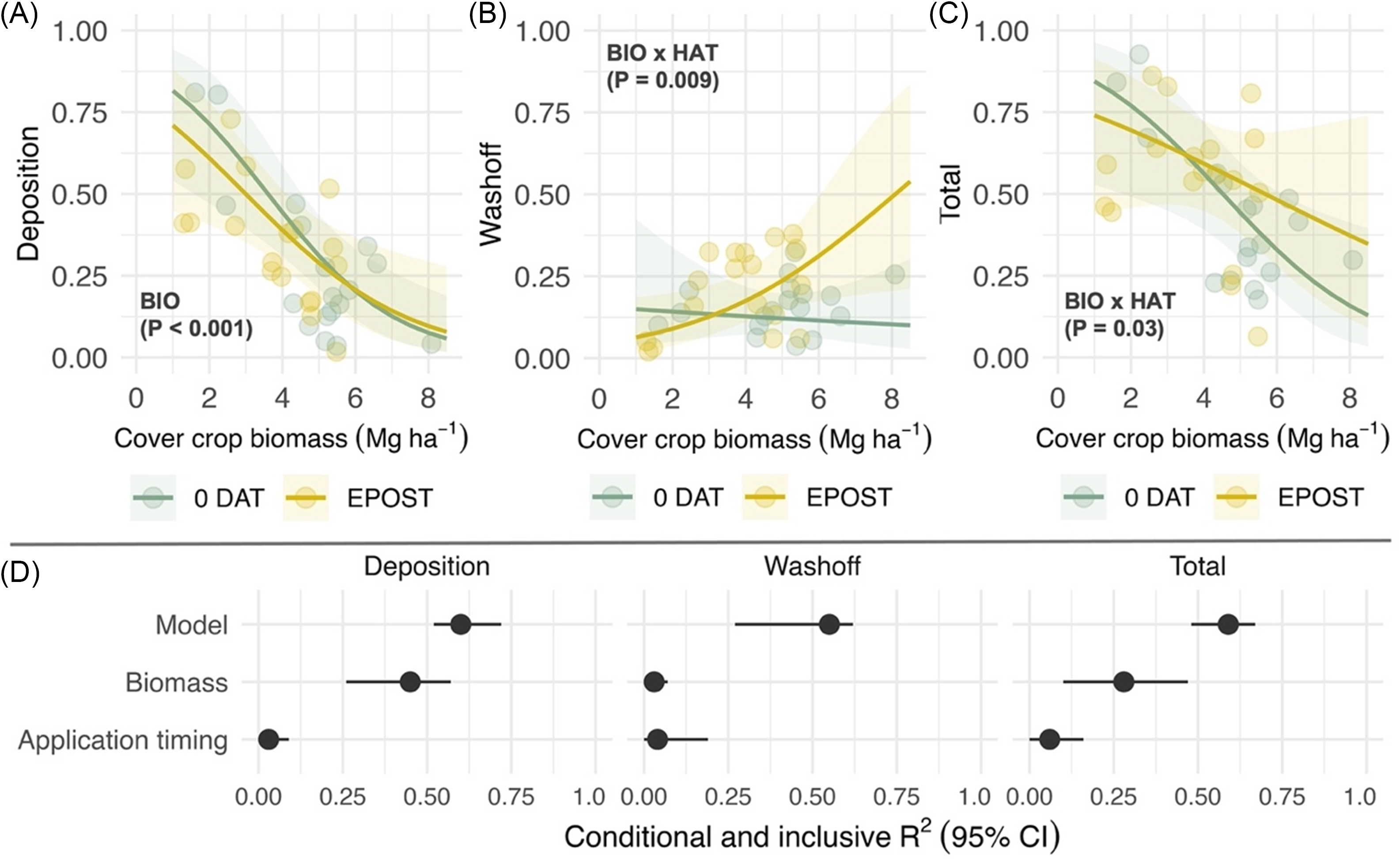

Pyroxasulfone deposition was negatively correlated with cereal rye biomass (χ2 = 5.7; P = 0.01) among cereal rye treatments left standing, but no effect of application timing was observed (Figure 2A). The proportion of recovered pyroxasulfone attributed to wash-off did not vary as a function of cereal rye biomass within 0 DAT treatments but significantly increased as a function of cereal rye biomass within early postemergence treatments (χ2 = 8.1; P = 0.004; Figure 2B). An interaction between cereal rye biomass and herbicide application timing was observed in analysis of total recovery (χ2 = 3.2; P = 0.07; Figure 2C). Total recovery was similar across cereal rye biomass levels within early postemergence treatments but declined in 0 DAT treatments. Fitted terms, including random intercepts (site-years), accounted for 53%, 45%, and 55% of variance (R2 c) in deposition, wash-off, and total recovery models (Figure 2D, Model). Cover crop biomass and its interaction with application timing accounted for greater proportion of variance explained in deposition and total recovery models (20% and 16%, respectively) compared with herbicide application timing (Figure 2D, Inclusive R2). Conversely, herbicide application timing and its interaction with cover crop biomass accounted for a greater proportion of variance (10%) explained in the wash-off model.

Figure 2. Predicted effects of cereal rye biomass (BIO; Mg ha−1) that is left standing and herbicide application timing (HAT) on pyroxasulfone (A) deposition, (B) wash-off, and (C) total recovery, which are expressed as a proportion of a no cover crop standard (STD); and (D) the proportion of variance explained by the fitted model (conditional R2; model) and unique and joint effects (inclusive R2) of each predictor (biomass, application timing). Herbicide application timings include the day of cereal rye termination (0 DAT) and simulation of an early-postemergence timing in corn or soybean. Shaded bands are 95% prediction intervals, and points are estimated marginal means for imposed treatments at the site-year level.

Deposition and Wash-Off in Roll-Crimped Cover Crops

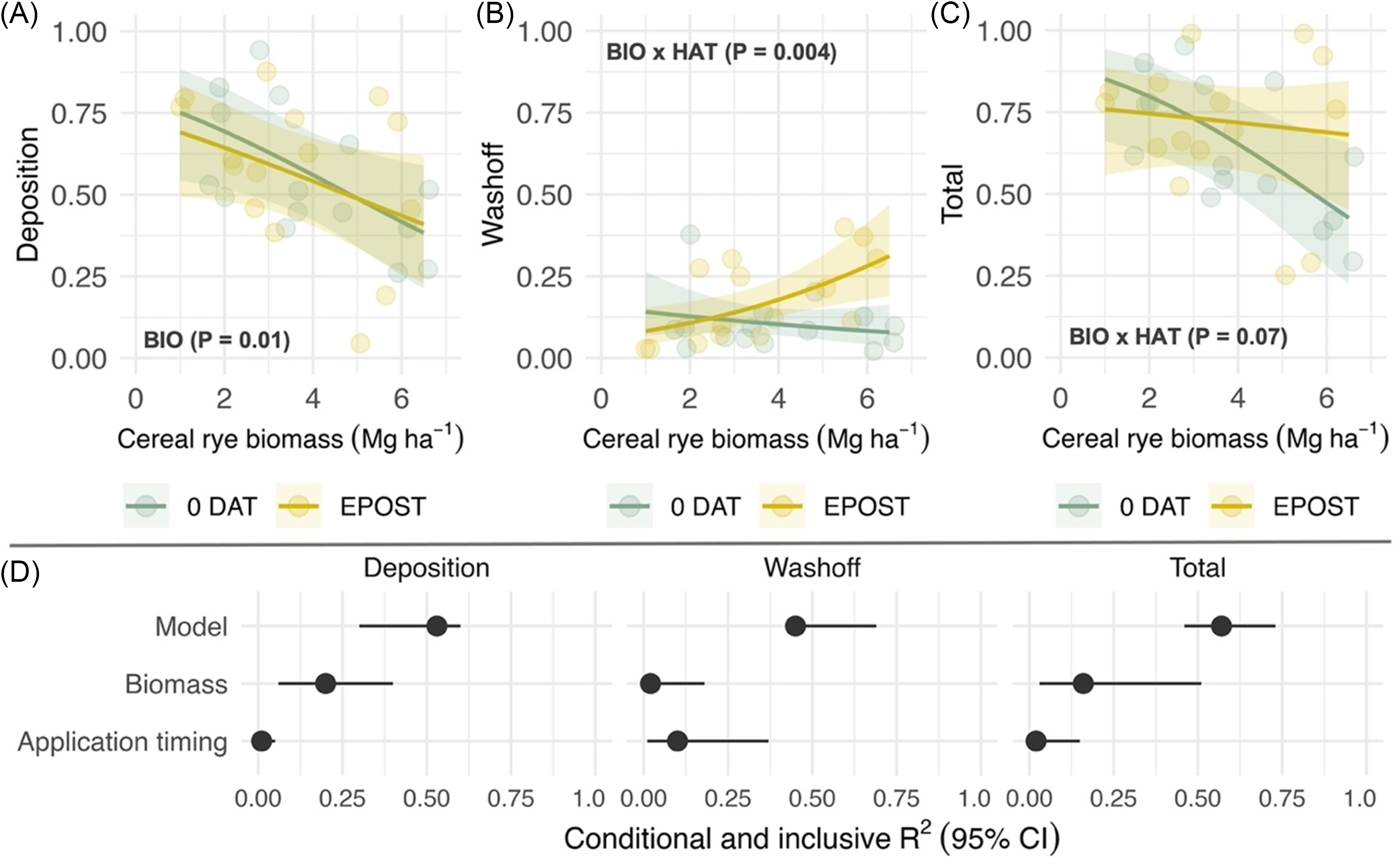

Deposition of pyroxasulfone was negatively correlated with cover crop biomass (χ2 = 13.9; P < 0.001) among treatments roll-crimped at the cereal rye anthesis stage, but no effect of application timing was observed (Figure 3A). The proportion of recovered pyroxasulfone attributed to wash-off did not vary as a function of cover crop biomass within 0 DAT treatments but significantly increased as a function of biomass within early postemergence treatments (χ2 = 6.6; P = 0.009; Figure 3B). A significant interaction between cover crop biomass and herbicide application timing was observed in analysis of total recovery (χ2 = 4.5; P = 0.03; Figure 3C), where total recovery declined at a higher rate in 0 DAT compared with early postemergence treatments as cover crop biomass levels increased. Fitted terms, including random intercepts (site-years), accounted for more than 50% of variance (R2 c) in each model (Figure 3D, Model). Cover crop biomass and its interaction with application timing accounted for 45% of variance explained in the deposition model, but only 28% in the total recovery model (Figure 3D, Inclusive R2). The unique and joint effects of biomass and herbicide application each contributed to less than 5% of variance in the wash-off model.

Figure 3. Predicted effects of cover crop biomass (BIO; Mg ha−1) that is roll-crimped at the cereal rye anthesis stage and herbicide application timing (HAT) on pyroxasulfone (A) deposition, (B) wash-off, and (C) total recovery, which are expressed as a proportion of a no cover crop standard (STD); and the (D) proportion of variance explained by the fitted model (conditional R2; model) and unique and joint effects (inclusive R2) of each predictor (biomass, application timing). Herbicide application timings include the day of cereal rye termination (0 DAT) and simulation of an early-postemergence timing in corn or soybean. Shaded bands are 95% prediction intervals, and points are estimated marginal means for imposed treatments at the site-year level.

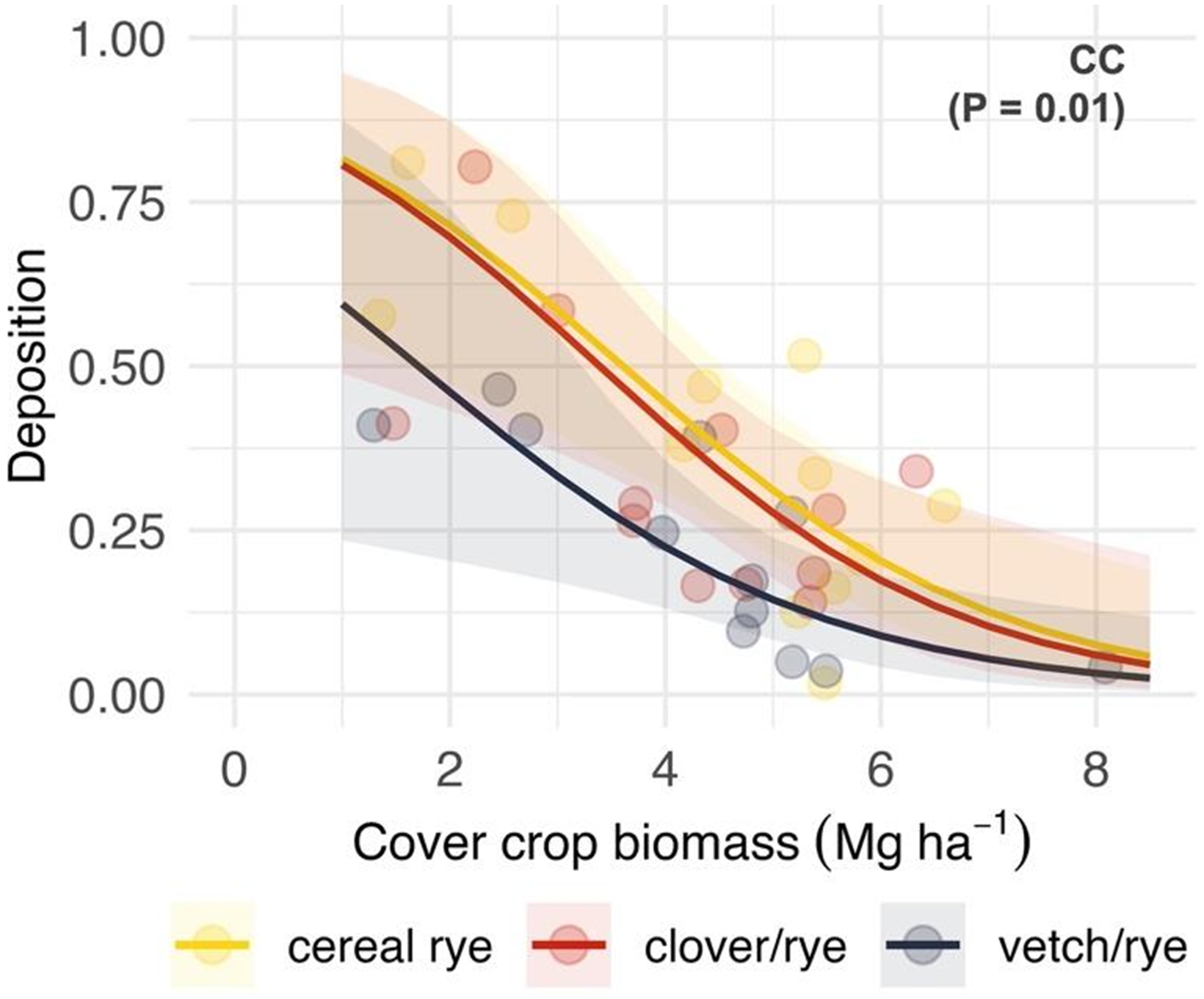

Effects of Roll-Crimped Grass–Legume Mixtures

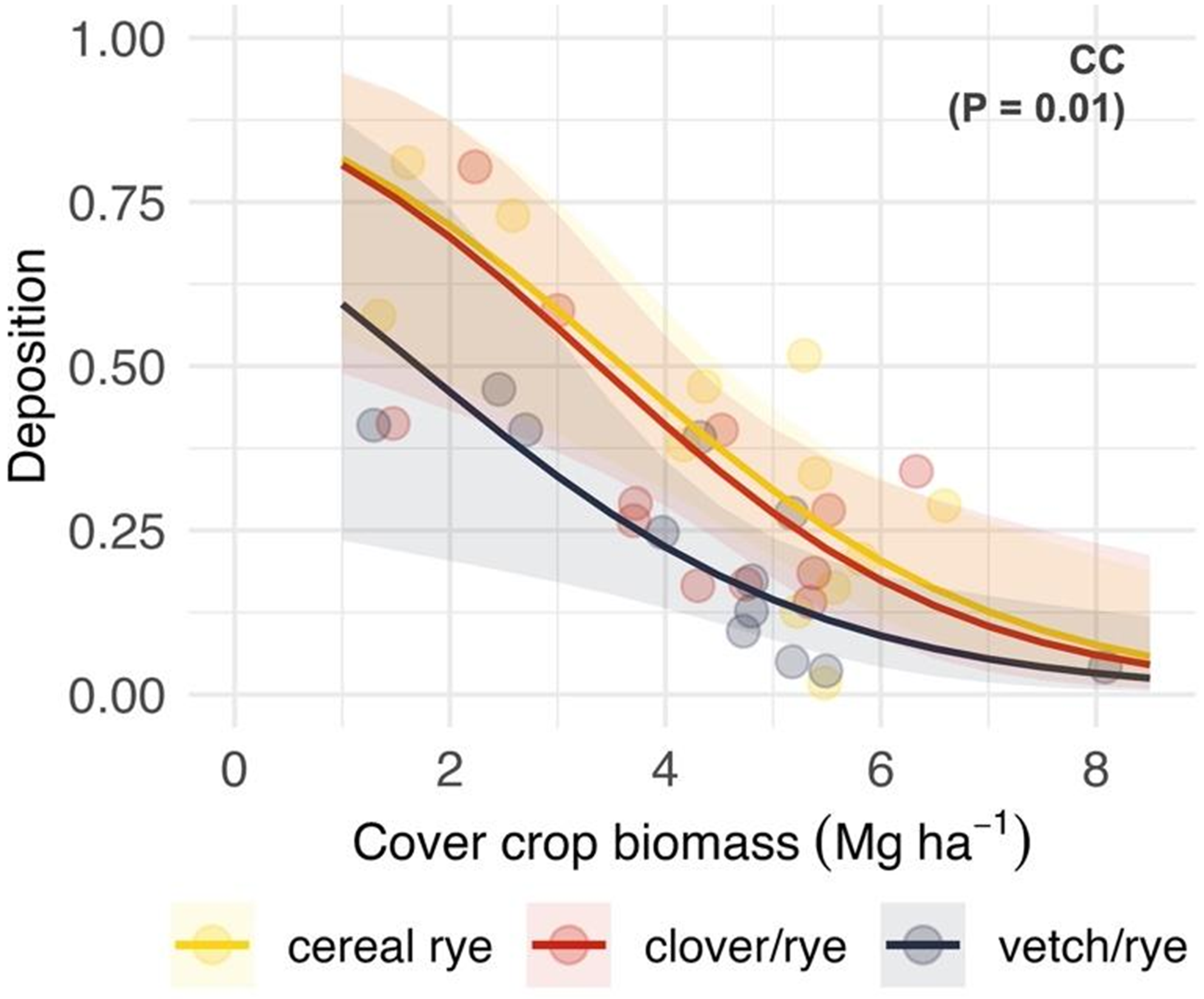

Inclusion of a legume (crimson clover or hairy vetch) with cereal rye resulted in reduced deposition (z = 2.7; P = 0.005) and total recovery (z = 2.3; P = 0.02) of pyroxasulfone when compared with roll-crimping cereal rye monocultures (Table 2). A significant main effect of cover crop species (χ2 = 9.1; P = 0.01) was observed when included as a covariate in models relating deposition to cover crop biomass (Figure 4), wherein deposition was lower in cereal rye–hairy vetch mixtures than cereal rye–crimson clover mixtures or cereal rye monocultures across the observed biomass gradient. Model results did not support the hypothesis that the relationship between herbicide wash-off potential and cover crop species selection varies by application timing (χ2 = 0.6; P = 0.73), suggesting that the difference in properties of aged residues at the early post emergence timing between cereal rye and rye–legume mixtures was not large enough to produce a treatment response.

Figure 4. Predicted effects of cover crop biomass (Mg ha−1) that is roll-crimped at the cereal rye anthesis stage and cover crop treatment (CC) on pyroxasulfone deposition, which is expressed as a proportion of a no cover crop standard (STD). Cover crop treatments include a cereal rye as a monoculture (yellow) or in mixture with crimson clover (red) or hairy vetch (purple). Shaded bands are 95% prediction intervals and points are estimated marginal means for imposed treatments at the site-year level.

Our results are partially supported by previous studies that have used different methodologies to characterize herbicide fate in conservation agriculture systems that integrate cover crop surface residues. Studies that have measured herbicide deposition to the soil surface in the presence of cover crops have shown a negative correlation between cover crop biomass and herbicide spray coverage when measured using water-sensitive spray cards (Bunchek Reference Bunchek2018; Haramoto et al. Reference Haramoto, Sherman and Green2020; Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Arneson, DeWerff, Ruark, Conley, Smith and Werle2023b). For example, Haramoto et al. (Reference Haramoto, Sherman and Green2020) reported a 44% reduction in spray coverage when applied into a living cereal rye cover crop approximately 40 cm in height (Zadoks 31) and 4 Mg ha−1 in aboveground biomass. Bunchek (Reference Bunchek2018) observed a 33% to 60% reduction in spray coverage at the soil surface when applications were made into cereal rye (3 Mg ha−1) or a cereal rye–hairy vetch mixture (6 Mg ha−1) that was chemically terminated approximately 14 d before application near the Zadoks 69 growth stage of cereal rye. At higher cereal rye biomass levels (9 to 12 Mg ha−1), Nunes et al. (Reference Nunes, Arneson, DeWerff, Ruark, Conley, Smith and Werle2023b) found negligible differences in spray coverage between treatments that were either roll-crimped or left standing at the time of application, whereas leaving cereal rye standing resulted in greater spray coverage than roll-crimped treatments at more moderate biomass levels (5 Mg ha−1). This study also quantified initial concentrations of metolachlor and sulfentrazone and found a significantly positive relationship between spray coverage and initial soil concentration of each herbicide.

Recent field studies have also quantified herbicide soil concentration over time within various cover crop management scenarios. This research method is applicable for quantifying weed control potential but would require pattern-based analyses to understand the role of cover crop management on both deposition and wash-off dynamics. For example, Whalen et al. (Reference Whalen, Shergill, Kinne, Bish and Bradley2020) observed lower sulfentrazone concentrations in soil when applied into a range of cover crop species that were terminated at 7 days pre-plant (DPP) compared with 21 DPP, which was attributed to greater biomass accumulation in delayed termination (7 DPP) treatments. In this study, there was a trend toward increased herbicide concentrations between 0 and 14 d after application, which suggests that a proportion of intercepted spray was washed from aged (7 to 21 d) cover crop residues and incorporated into the soil profile. In a mutiregional study, Nunes et al. (Reference Nunes, Arneson, Wallace, Gage, Miller, Lancaster, Mueller and Werle2023a) observed greater pyroxasulfone concentration at 7 DAT compared with 0 DAT in some site-years when pyroxasulfone was applied into living cereal rye in a planting green scenario. In a similar study, Maia et al. (Reference Maia, Armstrong, Kladivko, Young and Johnson2025) reported a 55% reduction in S-metolachlor concentration in soil at 0 DAT due to interception by aged cover crop residues, which ranged from 1 to 7 Mg ha−1 in aboveground biomass at the time of termination. But these authors did not observe increased S-metolachlor concentration in soil at subsequent sampling dates following rainfall events.

We suggest that our study contributes to the growing literature on herbicide fate in cover crop systems by quantifying the relative effects of (1) standing versus roll-crimped residue, (2) cereal rye versus cereal rye–legume mixtures, and (3) living versus aged cover crop residues on both deposition and wash-off potential while controlling for aboveground biomass effects. However, two uncertainties are worth noting when considering inferences from our fitted models. First, in utilizing field-based assays, we were unable to control for the frequency and total volume of rainfall among herbicide application timings and across site-years. A previous study suggests that rainfall ranging from 5 to 20 mm is sufficient for washing pyroxasulfone from high levels of wheat residue (4 t ha−1) when the rainfall occurred within 14 d after herbicide application (Khalil et al. Reference Khalil, Flower, Siddique and Ward2019). In 2022, our targeted rainfall threshold (>12.5 mm) occurred between 1 to 6 d after herbicide application among locations. In comparison, these thresholds occurred between 1 to 25 d within the 2023 growing season due to drier spring conditions. This variability in the number of days to rainfall thresholds, as well as the total volume, likely contributed to unexplained variation in our fitted models (Figures 2D and 3D). Our sampling method may have also partially contributed to unexplained variation in fitted models. Herbicide deposition is lower within cover crop intrarows compared with interrows, although the magnitude of differences at this scale is strongly mediated by total aboveground biomass (Haramoto et al. Reference Haramoto, Sherman and Green2020; Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Arneson, DeWerff, Ruark, Conley, Smith and Werle2023b). Thus, our petri dish assay methods may have not fully captured the spatial dynamics of herbicide deposition and wash-off from cover crops that operate at micro-site scales. Nonetheless, we suggest that our models provide strong inferences for how alternative cover crop management tactics impact deposition and wash-off potential of soil-residual herbicides.

Management Implications

Our results indicate that under lower cereal rye biomass (i.e., 2 Mg ha−1), which is left standing, herbicide deposition is reduced by approximately 35% relative to bare ground regardless of application timing (0 DAT, early postemergence). At these biomass levels, the reduction in soil concentration is closer to 25% after pyroxasulfone wash-off from residues following rainfall events. In comparison, residual herbicide application timing is a comparatively more important factor in determining initial soil concentration when herbicides are applied into standing cereal rye at higher biomass levels (5 Mg ha−1), which is a potential biomass target for enhancing weed-suppression potential of cover crop surface residues (Nichols et al. Reference Nichols, Martinez-Feria, Weisberger, Carlson, Basso and Basche2020; Weisberger et al. Reference Weisberger, Bastos, Sykes and Basinger2023). At 5 Mg ha−1, herbicide deposition is reduced by 50% regardless of application timing, but due to greater wash-off potential, initial soil concentration is greater at an early postemergence application timing (70%) than in a planting green scenario (0 DAT; 55%).

At higher cereal rye biomass levels (5 Mg ha−1), roll-crimping is more likely to be employed as a residue management tool. In this scenario, herbicide deposition is reduced by approximately 70% compared with bare ground regardless of application timing. After accounting for wash-off dynamics, total recovery was greater when pyroxasulfone was applied at an early postemergence timing (55%) compared with a planting green scenario (0 DAT; 45%). In our study, inclusion of hairy vetch in mixture with cereal rye further decreased herbicide deposition (85% reduction) into roll-crimped residues at a 5 Mg ha−1 biomass level, but comparatively greater wash-off of pyroxasulfone resulted in similar initial soil concentration to cereal rye monocultures. Reddy et al. (Reference Reddy, Locke, Wagner, Zablotowicz, Gaston and Smeda1995) also reported higher herbicide interception rates by hairy vetch compared with cereal rye, which was attributed to greater surface area for sorption per unit of mass. Additional research is needed to understand relationships between the physiochemical properties of cover crop species, herbicide sorption properties, and wash-off potential.

Results of our study bring two knowledge gaps into greater focus. First, initial concentration of soil-residual herbicides can be significantly reduced (>50%) when cover crop management is intensified to include (1) higher biomass via planting green, (2) use of roller-crimpers for residue management, and (3) inclusion of legume species in mixture. Yet field studies that have evaluated integration of high biomass cover crops and soil-residual (preemergence) herbicides report that weed control (%) from combining these tactics is equal to or exceeds control levels from preemergence herbicides alone (Bunchek et al. Reference Bunchek, Wallace, Curran, Mortensen, VanGessel and Scott2020; Loux et al. Reference Loux, Dobbels, Bradley, Johnson, Young, Spaunhorst, Norsworthy, Palhano and Steckel2017; Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Wallace, Arneson, Johnson, Young, Norsworthy, Ikley, Gage, Bradley, Jha, Lancaster, Kumar, Legleiter and Werle2024). Studies that have documented lower herbicide concentrations in soil over time in the presence of cover crops have also reported similar weed control benefits from combining tactics (Maia et al. Reference Maia, Armstrong, Kladivko, Young and Johnson2025; Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Arneson, Wallace, Gage, Miller, Lancaster, Mueller and Werle2023a). Synergistic action, where the mean lethal herbicide dose is lower in the presence of cover crops (Figure 1B), is one explanation for these reported weed control outcomes. In such a scenario, cover crop stressors may either limit resource acquisition necessary to survive herbicide stressors or lengthen exposure to herbicide stressors by slowing the germination to establishment life-cycle transition. An alternative hypothesis is that the lethal dose of many soil-residual herbicides is considerably lower for commonly targeted weed species than reduced concentrations reported in cover-cropping experiments. For example, Teasdale et al. (Reference Teasdale, Shelton, Sadeghi and Isensee2003) reported that the mean lethal dose (LD50) of S-metolachlor for several common annual weed species (A. hybridus, C. album, giant foxtail [Setaria faberi Herrm.]) is approximately 10% of a standard label rate, or more than three soil half-lives. Recent field studies also indicate that initial concentrations (i.e., 0 to 7 DAT) of soil-residual herbicides in cover crop systems can be significantly reduced, but due to differences in degradation rates, soil concentrations become more comparable in cover crop and no cover crop scenarios at 21 DAT (Maia et al. Reference Maia, Armstrong, Kladivko, Young and Johnson2025; Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Arneson, Wallace, Gage, Miller, Lancaster, Mueller and Werle2023a). Finally, an alternative hypothesis is that spatial heterogeneity of residual herbicide concentration in soil is high and inversely correlated with cover crop residues, resulting in microsites that either have herbicide concentrations or cover crop residues sufficient to reduce weed recruitment. Cover crop biomass and residue complexity, and therefore soil coverage, are highly variable at the microsite scale (Eslami and Davis Reference Eslami and Davis2018; Teasdale et al. Reference Teasdale, Pillai and Collins2005).

Second, our results highlight the relative importance of herbicide application timing in mediating wash-off dynamics when higher levels of cover crop biomass are realized. Wash-off potential of pyroxasulfone from living cereal rye was greater than from aged cereal rye residues targeted at an early postemergence application timing. Pyroxasulfone and other VLCFA inhibitors are nonpolar herbicides that are readily absorbed across plant cuticles, thereby limiting desorption rates via rainfall if intercepted by living foliage (Krutz et al. Reference Krutz, Koger, Locke and Steinriede2007). Herbicide absorption and desorption rates in living foliage are a function of a herbicide’s lipophilicity (log Kow) and acid strength (pKa), which mediate diffusion or active transport across lipophilic membranes (Takano et al. Reference Takano, Patterson, Nissen, Dayan and Gaines2019).

Although our results demonstrate that wash-off potential depends on whether cover crops are living (0 DAT) or terminated (early postemergence), there was a significant amount of unexplained variation in wash-off models that is likely related to the timing, amount, and frequency of rainfall. Rainfall events are beyond the control of managers, but herbicide selection and application timing are two management decisions that could be adjusted to optimize wash-off potential when higher cover crop biomass levels are targeted. Inferences from our modeled estimates of wash-off and total recovery are limited to pyroxasulfone, but future research focused on quantifying interactions among herbicide sorption properties and cover crop physiochemical properties can utilize our estimates of deposition among cover crop management scenarios as a starting point for evaluating the relative importance of wash-off dynamics in herbicide transport to soil.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that increased cereal rye biomass via delayed termination can significantly reduce (>50%) the deposition of herbicides to the soil surface. At high biomass levels (>5 Mg ha−1), roll-crimping cereal rye results in additional (20%) interception of herbicide spray compared with cereal rye left standing. Including hairy vetch in mixture with cereal rye results in additional interception (15%) compared with roll-crimped cereal rye monocultures. Management scenarios that result in high levels of herbicide interception become more reliant on wash-off for herbicide transport to soil. Our results demonstrate that wash-off potential is likely greater when herbicides are applied into terminated cover crops that are in early stages of decomposition compared with living cover crops in a planting green scenario. These results suggest that if high biomass (>5 Mg ha−1) is realized, repositioning the timing of residual herbicide applications to later crop growth stages is worth considering to improve the combined action of cover crop– and herbicide-based weed control tactics.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2025.10070

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tosh Mazzone, Jared Adam, Megan Czekaj, Kevin Bamber, and Barb Scott for assisting in the completion of this project.

Funding statement

This research was supported by USDA-NIFA Crop Protection and Pest Management (CPPM) program grant award (no. 2021-04906) and in-kind services from USDA-ARS Pasture Systems and Watershed Management Research Unit project no. 8070-13000-015-00D.

Competing interests

No conflicts of interest have been declared.