1 Introduction and background

1.1 Preliminaries

We assume that the reader is familiar with the basic concepts and results of algorithmic randomness. Our notation is standard. Unexplained notation can be found in Downey and Hirschfeldt [Reference Downey and Hirschfeldt3]. As it is standard in the field, all rational and real numbers are meant to be in the unit interval

![]() $[0,1)$

, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

$[0,1)$

, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

We start with reviewing some central concepts and results that will be used subsequently. The main object of interest of this article is the Solovay reducibility, which has been introduced by Robert M. Solovay [Reference Solovay11] in 1975 as a measure of relative randomness. Its original definition by Solovay uses the notion of a translation function defined on the left cut of a real.

Definition 1.1. A computable approximation is a computable Cauchy sequence, i.e., a computable sequence of rational numbers that converges. A real is computably approximable, or c.a., if it is the limit of some computable approximation.

A left-c.e. approximation is a nondecreasing computable approximation. A real is left-c.e. if it is the limit of some left-c.e. approximation.

Definition 1.2. The left cut of a real

![]() $\alpha $

, written

$\alpha $

, written

![]() $LC(\alpha )$

, is the set of all rationals strictly smaller than

$LC(\alpha )$

, is the set of all rationals strictly smaller than

![]() $\alpha $

.

$\alpha $

.

Definition 1.3 (Solovay, 1975).

A translation function from a real

![]() $\beta $

to a real

$\beta $

to a real

![]() $\alpha $

is a partially computable function g from the set

$\alpha $

is a partially computable function g from the set

![]() ${\mathbb {Q}} \cap [0,1)$

to itself such that, for all

${\mathbb {Q}} \cap [0,1)$

to itself such that, for all

![]() $q<\beta $

, the value

$q<\beta $

, the value

![]() $g(q)$

is defined and fulfills

$g(q)$

is defined and fulfills

![]() $g(q)<\alpha $

, and

$g(q)<\alpha $

, and

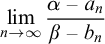

where

![]() $\lim \limits _{q\nearrow \beta }$

denotes the left limit.

$\lim \limits _{q\nearrow \beta }$

denotes the left limit.

A real

![]() $\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to a real

$\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to a real

![]() $\beta $

, also written as

$\beta $

, also written as

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

, if there is a real constant c and a translation function g from

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

, if there is a real constant c and a translation function g from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

such that, for all

$\alpha $

such that, for all

![]() $q< \beta $

, it holds that

$q< \beta $

, it holds that

We will refer to (2) as Solovay condition and to c as Solovay constant, and we say that g witnesses the Solovay reducibility of

![]() $\alpha $

to

$\alpha $

to

![]() $\beta $

.

$\beta $

.

Note that if a partially computable rational-valued function g is defined on all of the set

![]() $LC(\beta )$

and maps it to

$LC(\beta )$

and maps it to

![]() $LC(\alpha )$

, then the Solovay condition (2) implies (1).

$LC(\alpha )$

, then the Solovay condition (2) implies (1).

Noting that the translation function g defined above provides useful information only about the left cuts of

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

, many researchers focused on Solovay reducibility as a measure of relative randomness of left-c.e. reals, whereas, outside of the left-c.e. reals, the notion has been considered as “badly behaved” by several authors (see, e.g., Downey and Hirschfeldt [Reference Downey and Hirschfeldt3, Section 9.1]).

$\beta $

, many researchers focused on Solovay reducibility as a measure of relative randomness of left-c.e. reals, whereas, outside of the left-c.e. reals, the notion has been considered as “badly behaved” by several authors (see, e.g., Downey and Hirschfeldt [Reference Downey and Hirschfeldt3, Section 9.1]).

Calude, Hertling, Khoussainov, and Wang [Reference Calude, Hertling, Khoussainov and Wang2] gave an equivalent characterization of Solovay reducibility on the set of the left-c.e. reals in terms of left-c.e. approximations of the involved reals.

Proposition 1.4 (Calude et al., 1998).

A left-c.e. real

![]() $\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to a left-c.e. real

$\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to a left-c.e. real

![]() $\beta $

with a Solovay constant c if and only if, for every left-c.e. approximations

$\beta $

with a Solovay constant c if and only if, for every left-c.e. approximations

![]() $a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

$a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

, there exists a computable index function

$b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

, there exists a computable index function

![]() $f:\mathbb {N}\to \mathbb {N}$

such that, for every n, it holds that

$f:\mathbb {N}\to \mathbb {N}$

such that, for every n, it holds that

Informally speaking, the reduction

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

provides for every left-c.e. approximation of

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

provides for every left-c.e. approximation of

![]() $\beta $

a not slower left-c.e. approximation of

$\beta $

a not slower left-c.e. approximation of

![]() $\alpha $

. It is well known and easy to prove that the universal quantification over left-c.e. approximations to

$\alpha $

. It is well known and easy to prove that the universal quantification over left-c.e. approximations to

![]() $\alpha $

in Proposition 1.4 can be replaced by an existential quantification as follows.

$\alpha $

in Proposition 1.4 can be replaced by an existential quantification as follows.

Proposition 1.5. A left-c.e. real

![]() $\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to a left-c.e. real

$\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to a left-c.e. real

![]() $\beta $

with a Solovay constant c if and only if there exist left-c.e. approximations

$\beta $

with a Solovay constant c if and only if there exist left-c.e. approximations

![]() $a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

$a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

such that, for every n, it holds that

$b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

such that, for every n, it holds that

In what follows, we refer to the characterizations of Solovay reducibility given in Definition 1.3 and in Propositions 1.4 and 1.5 as rational and index approaches, respectively.

Remark. Zheng and Rettinger [Reference Zheng, Rettinger, Chwa, Ian and Munro14] used the index approach to introduce the following modification of Solovay reducibility on the computably enumerable reals: a c.a. real is S2a-reducible to a real

![]() $\beta $

if there exist a constant c and computable approximations

$\beta $

if there exist a constant c and computable approximations

![]() $a_0,a_1,\dots $

and

$a_0,a_1,\dots $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots $

of

$b_0,b_1,\dots $

of

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

, respectively, that safisfy the inequality

$\beta $

, respectively, that safisfy the inequality

![]() $|\alpha - a_n| < c(|\beta - b_n| + 2^{-n})$

for all n.

$|\alpha - a_n| < c(|\beta - b_n| + 2^{-n})$

for all n.

When comparing Solovay reducibility and S2a-reducibility, both are equivalent on the left-c.e. reals [Reference Zheng, Rettinger, Chwa, Ian and Munro14, Theorem 3.2(2)] but S2a-reducibility is strictly weaker on the c.a. reals [Reference Titov13, Theorem 2.1]. Some authors [Reference Hoyrup, Saucedo, Stull, Chatzigiannakis, Kaklamanis, Marx and Sannella4, Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Reference Rettinger and Zheng10] consider S2a-reducibility and not Solovay reducibility as the standard reducibility for investigating the c.a. reals.

1.2 The Barmpalias–Lewis-Pye limit theorem on left-c.e. reals: two versions

Using the index approach of Calude et al., Kučera and Slaman [Reference Kucera and Slaman5] have proven that the

![]() $\Omega $

-like reals, i.e., Martin-Löf random left-c.e. reals, form the highest Solovay degree on the set of left-c.e. reals. The core of their proof is the following assertion.

$\Omega $

-like reals, i.e., Martin-Löf random left-c.e. reals, form the highest Solovay degree on the set of left-c.e. reals. The core of their proof is the following assertion.

Lemma 1.6 (Kučera and Slaman, 2001).

For every two left-c.e. approximations

![]() ${a_0,a_1,\dots }$

and

${a_0,a_1,\dots }$

and

![]() ${b_0,b_1,\dots }$

of a left-c.e real

${b_0,b_1,\dots }$

of a left-c.e real

![]() $\alpha $

and a Martin-Löf random left-c.e. real

$\alpha $

and a Martin-Löf random left-c.e. real

![]() $\beta $

, respectively, there exists a constant c such that

$\beta $

, respectively, there exists a constant c such that

For an explicit proof of the latter lemma (see Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.1]. Barmpalias and Lewis-Pye [Reference Barmpalias and Lewis-Pye1] have strengthened Lemma 1.6 by showing the following theorem.

Theorem 1.7 (Barmpalias, Lewis-Pye, 2017).

For every left-c.e. real

![]() $\alpha $

and every Martin-Löf random left-c.e. real

$\alpha $

and every Martin-Löf random left-c.e. real

![]() $\beta $

, there exists a constant

$\beta $

, there exists a constant

![]() $d\geq 0$

such that, for every left-c.e. approximations

$d\geq 0$

such that, for every left-c.e. approximations

![]() $a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

$a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

, it holds that

$b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

, it holds that

Moreover,

![]() $d=0$

if and only if

$d=0$

if and only if

![]() $\alpha $

is not Martin-Löf random.

$\alpha $

is not Martin-Löf random.

We refer to Theorem 1.7 as index form of the Barmpalias–Lewis-Pye limit theorem. We will argue in connection with Proposition 1.9 below that the index form of the Limit Theorem, which is essentially the original formulation, can be equivalently stated, with the value of d preserved, in the following rational form (which necessitates the use of nondecreasing translation functions).

Theorem 1.8 (Rational form of the Barmpalias–Lewis-Pye limit theorem).

For every left-c.e. real

![]() $\alpha $

and every Martin-Löf random left-c.e. real

$\alpha $

and every Martin-Löf random left-c.e. real

![]() $\beta $

, there exists a constant

$\beta $

, there exists a constant

![]() $d\geq 0$

such that, for every nondecreasing translation function g from

$d\geq 0$

such that, for every nondecreasing translation function g from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

, it holds that

$\alpha $

, it holds that

$$ \begin{align} \lim\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} = d. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \lim\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} = d. \end{align} $$

Moreover,

![]() $d=0$

if and only if

$d=0$

if and only if

![]() $\alpha $

is not Martin-Löf random.

$\alpha $

is not Martin-Löf random.

The following proposition and its proof indicate that Theorems 1.8 and 1.7 can be considered as variants of each other.

Proof. First, we show that Theorem 1.7 follows from Theorem 1.8 with the same d. Let

![]() $a_0,a_1,\dots $

and

$a_0,a_1,\dots $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots $

be left-c.e. approximations of reals

$b_0,b_1,\dots $

be left-c.e. approximations of reals

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

where

$\beta $

where

![]() $\beta $

is Martin-Löf random. Let d be as in Theorem 1.8. Define functions f and h on

$\beta $

is Martin-Löf random. Let d be as in Theorem 1.8. Define functions f and h on

![]() $LC(\beta )$

by

$LC(\beta )$

by

Recall that both the sequences

![]() $a_0, a_1,\dots $

and

$a_0, a_1,\dots $

and

![]() $b_0, b_1,\dots $

are nondecreasing (but not necessarily strictly increasing). So, by construction, f and h are nondecreasing translation functions from

$b_0, b_1,\dots $

are nondecreasing (but not necessarily strictly increasing). So, by construction, f and h are nondecreasing translation functions from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

, and we have for all n that

$\alpha $

, and we have for all n that

![]() ${f(b_n) \le a_n \le h(b_n)}$

. As a consequence, we obtain

${f(b_n) \le a_n \le h(b_n)}$

. As a consequence, we obtain

$$ \begin{align} d = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - h(b_n)}{\beta - b_n} \leq \liminf \limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - a_n}{\beta - b_n} \leq \limsup \limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - a_n}{\beta - b_n} \leq \lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - f(b_n)}{\beta - b_n} = d, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} d = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - h(b_n)}{\beta - b_n} \leq \liminf \limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - a_n}{\beta - b_n} \leq \limsup \limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - a_n}{\beta - b_n} \leq \lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\frac{\alpha - f(b_n)}{\beta - b_n} = d, \end{align} $$

where the equalities hold by choice of d and by applying Theorem 1.8 to h and to f. Now, in particular, the limit inferiore and limit superiore in (6) are both equal to d, i.e., the corresponding sequence of fractions converges to d. Theorem 1.7 follows because

![]() $a_0,a_1,\dots $

and

$a_0,a_1,\dots $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots $

have been chosen as arbitrary left-c.e. approximations of

$b_0,b_1,\dots $

have been chosen as arbitrary left-c.e. approximations of

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

, respectively.

$\beta $

, respectively.

Next, we show that Theorem 1.8 follows from Theorem 1.7 with the same d. Let

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

be left-c.e. reals where

$\beta $

be left-c.e. reals where

![]() $\beta $

is Martin-Löf random, and fix some strictly increasing left-c.e. approximation

$\beta $

is Martin-Löf random, and fix some strictly increasing left-c.e. approximation

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots $

of

$b_0,b_1,\dots $

of

![]() $\beta $

. Let d be as in Theorem 1.7 and g be an arbitrary nondecreasing translation function from

$\beta $

. Let d be as in Theorem 1.7 and g be an arbitrary nondecreasing translation function from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

. For all n, let

$\alpha $

. For all n, let

![]() $a_n=g(b_n)$

. Then, for all rationals q and for n such that

$a_n=g(b_n)$

. Then, for all rationals q and for n such that

![]() $b_n \le q < b_{n+1}$

, the monotonicity of g implies that

$b_n \le q < b_{n+1}$

, the monotonicity of g implies that

![]() ${a_n \leq g(q) \leq a_{n+1}}$

, hence, for all such q and n, it holds that

${a_n \leq g(q) \leq a_{n+1}}$

, hence, for all such q and n, it holds that

$$ \begin{align} \underbrace{\frac{\alpha-a_{n+1}}{\beta - b_n}}_{= \rho_1(n)} \le \underbrace{\frac{\alpha-g(q)}{\beta - q}}_{= \rho(q)} < \underbrace{\frac{\alpha-a_n}{\beta - b_{n+1}}}_{= \rho_2(n)}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \underbrace{\frac{\alpha-a_{n+1}}{\beta - b_n}}_{= \rho_1(n)} \le \underbrace{\frac{\alpha-g(q)}{\beta - q}}_{= \rho(q)} < \underbrace{\frac{\alpha-a_n}{\beta - b_{n+1}}}_{= \rho_2(n)}. \end{align} $$

Now, the sequences

![]() $b_0, b_1,\dots $

and

$b_0, b_1,\dots $

and

![]() $b_1, b_2,\dots $

are both left-c.e. approximations of

$b_1, b_2,\dots $

are both left-c.e. approximations of

![]() $\beta $

, and, by choice of g and by (1), the sequences

$\beta $

, and, by choice of g and by (1), the sequences

![]() $a_1, a_2,\dots $

and

$a_1, a_2,\dots $

and

![]() $a_0, a_1,\dots $

are both left-c.e. approximations of

$a_0, a_1,\dots $

are both left-c.e. approximations of

![]() $\alpha $

. Hence, by Theorem 1.7, we have

$\alpha $

. Hence, by Theorem 1.7, we have

So for given

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, there is some index

$\varepsilon>0$

, there is some index

![]() $n(\varepsilon )$

such that, for all

$n(\varepsilon )$

such that, for all

![]() $n> n(\varepsilon )$

, the values

$n> n(\varepsilon )$

, the values

![]() $\rho _1(n)$

and

$\rho _1(n)$

and

![]() $\rho _2(n)$

differ at most by

$\rho _2(n)$

differ at most by

![]() $\varepsilon $

from d. But then, by (7), for every rational q where

$\varepsilon $

from d. But then, by (7), for every rational q where

![]() $b_{n(\varepsilon )} < q < \beta $

, the value

$b_{n(\varepsilon )} < q < \beta $

, the value

![]() $\rho (q)$

differs at most by

$\rho (q)$

differs at most by

![]() $\varepsilon $

from d. Thus, we have (5), i.e., the values

$\varepsilon $

from d. Thus, we have (5), i.e., the values

![]() $\rho (q)$

converge to d when q tends to

$\rho (q)$

converge to d when q tends to

![]() $\beta $

from the left. Since g was chosen as an arbitrary nondecreasing translation function from

$\beta $

from the left. Since g was chosen as an arbitrary nondecreasing translation function from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

, Theorem 1.8 follows.

$\alpha $

, Theorem 1.8 follows.

Monotone translation functions have been considered before by Kumabe, Miyabe, Mizusawa, and Suzuki [Reference Kumabe, Miyabe, Mizusawa and Suzuki6], who characterized Solovay reducibility on the set of left-c.e. reals in terms of nondecreasing real-valued translation functions.

It is not complicated to check that, in case a left-c.e. real is Solovay reducible to another left-c.e. real, this is always witnessed by a nondecreasing translation function while preserving any given Solovay constant.

Proposition 1.10. Let

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

be left-c.e. reals, and let c be a real. Then

$\beta $

be left-c.e. reals, and let c be a real. Then

![]() $\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

$\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

![]() $\beta $

with the Solovay constant c if and only

$\beta $

with the Solovay constant c if and only

![]() $\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

$\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

![]() $\beta $

via some nondecreasing translation function g and the Solovay constant c.

$\beta $

via some nondecreasing translation function g and the Solovay constant c.

Proof. For a proof of the nontrivial direction of the asserted equivalence, assume that

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

with the Solovay constant c. By Proposition 1.4, choose left-c.e. approximations

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

with the Solovay constant c. By Proposition 1.4, choose left-c.e. approximations

![]() $a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

$a_0,a_1,\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

such that (4) holds.

$b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

such that (4) holds.

Then

![]() $\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

$\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

![]() $\beta $

with the Solovay constant c via the nondecreasing translation function g defined by

$\beta $

with the Solovay constant c via the nondecreasing translation function g defined by

![]() $g(q)=a_{\max \{n\colon b_n\leq q\}}$

.

$g(q)=a_{\max \{n\colon b_n\leq q\}}$

.

Remark. Note that strengthening Definition 1.3 by considering only nondecreasing translation functions yields a well-defined reducibility

![]() ${\le }_{\mathrm {S}}^{\mathrm {m}} $

on

${\le }_{\mathrm {S}}^{\mathrm {m}} $

on

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

, called monotone Solovay reducibility. The basic properties of

$\mathbb {R}$

, called monotone Solovay reducibility. The basic properties of

![]() ${\le }_{\mathrm {S}}^{\mathrm {m}} $

have been investigated by Titov [Reference Titov12, Chapter 3]. Note that Proposition 1.10 shows that

${\le }_{\mathrm {S}}^{\mathrm {m}} $

have been investigated by Titov [Reference Titov12, Chapter 3]. Note that Proposition 1.10 shows that

![]() $\leq _S^{m}$

and

$\leq _S^{m}$

and

![]() ${\le }_{\mathrm {S}} $

coincide on the set of left-c.e. reals.

${\le }_{\mathrm {S}} $

coincide on the set of left-c.e. reals.

In Theorem 1.8, requiring the function g to be nondecreasing is crucial because, for every

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

that fulfills the conditions there, we can construct a nonmonotone translation function g such that the left limit in (5) does not exist, as we will see in the next proposition.

$\beta $

that fulfills the conditions there, we can construct a nonmonotone translation function g such that the left limit in (5) does not exist, as we will see in the next proposition.

Proposition 1.11. Let

![]() $\alpha ,\beta $

be two left-c.e. reals such that

$\alpha ,\beta $

be two left-c.e. reals such that

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

with a Solovay constant c. Then there exists a translation function g from

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

with a Solovay constant c. Then there exists a translation function g from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

such that

$\alpha $

such that

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

with the Solovay constant c via g, wherein

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

with the Solovay constant c via g, wherein

$$ \begin{align} \liminf\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} = 0\quad \text{and}\quad \limsup\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}> 0. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \liminf\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} = 0\quad \text{and}\quad \limsup\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}> 0. \end{align} $$

Proof. By Proposition 1.5, fix left-c.e. approximations

![]() $a_0,a_1\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

$a_0,a_1\dots \nearrow \alpha $

and

![]() $b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

such that (4) holds.

$b_0,b_1,\dots \nearrow \beta $

such that (4) holds.

The desired translation function g is defined by letting

$$ \begin{align*} &g(b_n+\frac{b_{n+1} - b_n}{2^k}) = a_{n+k} && \text{ for all }n,k>0\text{ in case }b_n\neq b_{n+1}, \\ &g(b_n - \frac{b_{n}-b_{n-1}}{3^k}) = a_{n+k} - c(b_{n+k} - b_n) && \text{ for all }n,k>0\text{ in case }b_{n-1}\neq b_n, \\ &g(q) = a_{\min\{n: b_n\geq q\}} && \text{ for all other rationals }q<\beta. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &g(b_n+\frac{b_{n+1} - b_n}{2^k}) = a_{n+k} && \text{ for all }n,k>0\text{ in case }b_n\neq b_{n+1}, \\ &g(b_n - \frac{b_{n}-b_{n-1}}{3^k}) = a_{n+k} - c(b_{n+k} - b_n) && \text{ for all }n,k>0\text{ in case }b_{n-1}\neq b_n, \\ &g(q) = a_{\min\{n: b_n\geq q\}} && \text{ for all other rationals }q<\beta. \end{align*} $$

Obviously, g is partially computable and defined on all rationals

![]() $< \beta $

.

$< \beta $

.

So, it suffices to show that g satisfies the conditions (2) and (8) (recall that the Solovay condition (2) implies (1) in the definition of translation functions).

In order to argue that (2) holds, we consider three cases:

-

• for

$q = b_n + \frac {b_{n+1}-b_n}{2^k}$

for some

$q = b_n + \frac {b_{n+1}-b_n}{2^k}$

for some

$n,k>0$

, where

$n,k>0$

, where

$b_n\neq b_{n+1}$

, (2) is implied by

$b_n\neq b_{n+1}$

, (2) is implied by  $$\begin{align*}\alpha - g(q) = \alpha - a_{n+k}\leq \alpha - a_{n+1}<c(\beta - b_{n+1})<c(\beta - q);\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\alpha - g(q) = \alpha - a_{n+k}\leq \alpha - a_{n+1}<c(\beta - b_{n+1})<c(\beta - q);\end{align*}$$

-

• for

$q = b_n - \frac {b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k}$

for some

$q = b_n - \frac {b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k}$

for some

$n,k>0$

where

$n,k>0$

where

$b_{n-1}\neq b_n$

, (2) follows from

$b_{n-1}\neq b_n$

, (2) follows from  $$\begin{align*}\kern-6pt\alpha - g(q) = \alpha - a_{n+k} + c(b_{n+k} - b_n) < c(\beta - b_{n+k}) + c(b_{n+k} - b_n) < c(\beta - q);\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\kern-6pt\alpha - g(q) = \alpha - a_{n+k} + c(b_{n+k} - b_n) < c(\beta - b_{n+k}) + c(b_{n+k} - b_n) < c(\beta - q);\end{align*}$$

-

• for all other q, (2) is implied by

$$\begin{align*}\alpha - g(q) = \alpha - a_{\min\{n:b_n\geq q\}} < c(\beta - b_{\min\{n:b_n\geq q\}})\leq c(\beta - q)\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\alpha - g(q) = \alpha - a_{\min\{n:b_n\geq q\}} < c(\beta - b_{\min\{n:b_n\geq q\}})\leq c(\beta - q)\end{align*}$$

(note that, in each case, the first strict inequality follows from (4)).

Further, the left part of (8) holds since, for every n such that

![]() $b_n\neq b_{n+1}$

, the real

$b_n\neq b_{n+1}$

, the real

![]() $\alpha $

is an accumulation point of

$\alpha $

is an accumulation point of

![]() $g(q)|_{[b_n, b_{n+1}]}$

since

$g(q)|_{[b_n, b_{n+1}]}$

since

![]() $g(b_n+\frac {b_{n+1} - b_n}{2^k})\underset {k\to \infty }{\to }\alpha $

.

$g(b_n+\frac {b_{n+1} - b_n}{2^k})\underset {k\to \infty }{\to }\alpha $

.

Finally, the right part of (8) holds since, for every n such that

![]() $b_{n-1}\neq b_n$

, the constant c is an accumulation point of

$b_{n-1}\neq b_n$

, the constant c is an accumulation point of

![]() $\frac {\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}|_{[b_{n-1},b_n]}$

since

$\frac {\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}|_{[b_{n-1},b_n]}$

since

$$\begin{align*}\frac{\alpha - g(b_n - \frac{b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k})}{\beta - (b_n - \frac{b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k})} = \frac{\alpha - a_{n+k} + c(b_{n+k} - b_n)}{\beta - b_n + \frac{b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k}} \underset{k\to\infty}{\longrightarrow}\frac{c(\beta - b_n)}{\beta - b_n} = c.\\[-47pt] \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\frac{\alpha - g(b_n - \frac{b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k})}{\beta - (b_n - \frac{b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k})} = \frac{\alpha - a_{n+k} + c(b_{n+k} - b_n)}{\beta - b_n + \frac{b_n - b_{n-1}}{3^k}} \underset{k\to\infty}{\longrightarrow}\frac{c(\beta - b_n)}{\beta - b_n} = c.\\[-47pt] \end{align*}$$

The latter proposition is a motivation to consider the Solovay reducibility via only nondecreasing translation functions in order to extend the Barmpalias–Lewis-Pye limit theorem on

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

.

$\mathbb {R}$

.

2 The theorem

Theorem 2.1. For every real

![]() $\alpha $

and every Martin-Löf random real

$\alpha $

and every Martin-Löf random real

![]() $\beta $

, there exists a constant

$\beta $

, there exists a constant

![]() $d\geq 0$

such that, for every nondecreasing translation function g from

$d\geq 0$

such that, for every nondecreasing translation function g from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

, it holds that

$\alpha $

, it holds that

$$ \begin{align} \lim\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} = d. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \lim\limits_{q\nearrow\beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} = d. \end{align} $$

Proof. Let

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\beta $

be two reals where

$\beta $

be two reals where

![]() $\beta $

is Martin-Löf random, and let g be a nondecreasing translation function from

$\beta $

is Martin-Löf random, and let g be a nondecreasing translation function from

![]() $\beta $

to

$\beta $

to

![]() $\alpha $

.

$\alpha $

.

The proof is organized as follows.

In Section 2.2, we show that

![]() $\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

$\alpha $

is Solovay reducible to

![]() $\beta $

via the translation function g, i.e., that the fraction in (9) is bounded from above for

$\beta $

via the translation function g, i.e., that the fraction in (9) is bounded from above for

![]() $q\nearrow \beta $

. This fact can be obtained using Claims 1–3, which we will state at the beginning of Section 2.2 after introducing some notation. Claim 1 will be proved by combinatorial arguments, Claim 2 can be obtained straightforwardly, and Claim 3 will be argued similarly to the case of left-c.e. reals [Reference Barmpalias and Lewis-Pye1, Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9].

$q\nearrow \beta $

. This fact can be obtained using Claims 1–3, which we will state at the beginning of Section 2.2 after introducing some notation. Claim 1 will be proved by combinatorial arguments, Claim 2 can be obtained straightforwardly, and Claim 3 will be argued similarly to the case of left-c.e. reals [Reference Barmpalias and Lewis-Pye1, Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9].

Next, in Section 2.2, we show that the left limit considered in the theorem exists by assuming the opposite, namely, that the left limit inferiore of the fraction in (9) does not coincide with its left limit superiore (note that, by the previous section, both of them differ from infinity). The contradiction will be obtained rather directly from Claims 7 –9, which we will also state in the beginning of the section. Claims 7 and 8 follow by arguments that are similar to the ones used in connection with the case of left-c.e. reals [Reference Kucera and Slaman5, Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9], whereas the proof of Claim 9 is rather involved and has no counterpart in the left-c.e. case.

Finally, in Section 2.3, we show that the left limit considered in the theorem does not depend on the choice of the translation function by assuming the opposite, namely, that there are two translation functions having different left limits of the fraction in (9).

The notation

In the remainder of this proof, and unless explicitly stated otherwise, the term “interval” refers to a closed interval on

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

that is bounded by rationals. Lebesgue measure is denoted by

$\mathbb {R}$

that is bounded by rationals. Lebesgue measure is denoted by

![]() $\mu $

, i.e., the Lebesgue measure, or measure, for short, of an interval U is

$\mu $

, i.e., the Lebesgue measure, or measure, for short, of an interval U is

![]() ${\mu (U)= \max U - \min U}$

.

${\mu (U)= \max U - \min U}$

.

A finite test is an empty set or a tuple

![]() $A=(U_0,\dots ,U_m)$

with

$A=(U_0,\dots ,U_m)$

with

![]() $m\geq 0$

where the

$m\geq 0$

where the

![]() $U_i$

are not necessarily distinct nonempty intervals. For such a finite test A, we define its covering function by

$U_i$

are not necessarily distinct nonempty intervals. For such a finite test A, we define its covering function by

that is,

![]() ${k_{A}} (x)$

is the number of intervals in A that contain the real number x. Furthermore, the measure of A is

${k_{A}} (x)$

is the number of intervals in A that contain the real number x. Furthermore, the measure of A is

![]() $\mu (A) = \sum _{i\in \{0,\dots ,m\}} \mu (U_i)$

.

$\mu (A) = \sum _{i\in \{0,\dots ,m\}} \mu (U_i)$

.

It is easy to see that the measure of a given finite test A can be computed by integrating its covering function on the whole domain

![]() $[0,1]$

, i.e., for every finite test A, it holds that

$[0,1]$

, i.e., for every finite test A, it holds that

$$ \begin{align*} \mu(A) =\int\limits _0^1 {k_{A}({x})} dx. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mu(A) =\int\limits _0^1 {k_{A}({x})} dx. \end{align*} $$

Observe that, by our definition (10) of the covering function, the values of the covering functions of two tests

![]() $([0.2, 0.3],[0.3,0.7])$

and

$([0.2, 0.3],[0.3,0.7])$

and

![]() $([0.2,0.7])$

differ on the argument

$([0.2,0.7])$

differ on the argument

![]() $0.3$

. Furthermore, for a given finite test and a rational q, by adding intervals of the form

$0.3$

. Furthermore, for a given finite test and a rational q, by adding intervals of the form

![]() $[q,q]$

the value of the corresponding covering function at q can be made arbitrarily large without changing the measure of the test. However, these observations will not be relevant in what follows since they relate only to the value of covering functions at rationals.

$[q,q]$

the value of the corresponding covering function at q can be made arbitrarily large without changing the measure of the test. However, these observations will not be relevant in what follows since they relate only to the value of covering functions at rationals.

For all three sections, we fix some effective enumeration

![]() $p_0, p_1, \dots $

without repetition of the domain of g and, for all natural n, define

$p_0, p_1, \dots $

without repetition of the domain of g and, for all natural n, define

![]() $Q_n = \{p_0, \dots , p_n\}$

.

$Q_n = \{p_0, \dots , p_n\}$

.

2.1 The fraction is bounded from above

First, we demonstrate that the translation function g witnesses the reducibility

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

, or, equivalently, that

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

, or, equivalently, that

$$ \begin{align} \exists c \forall q<\beta \left(\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}<c\right). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \exists c \forall q<\beta \left(\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}<c\right). \end{align} $$

For all n and i, we will construct a finite test

![]() $T_i^n$

based of the idea of test construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.1] for the left-c.e. case adapted for the nonmonotone enumeration of the domain of g (the adaptation is needed since the original Miller’s construction may not satisfy Claim 2 stated below if the enumeration of the domain of g is not increasing). The construction is effective in the sense that it always terminates and is uniform in n and i.

$T_i^n$

based of the idea of test construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.1] for the left-c.e. case adapted for the nonmonotone enumeration of the domain of g (the adaptation is needed since the original Miller’s construction may not satisfy Claim 2 stated below if the enumeration of the domain of g is not increasing). The construction is effective in the sense that it always terminates and is uniform in n and i.

For every n and i, let

![]() $Y_i^n$

be the union of all intervals lying in the finite test

$Y_i^n$

be the union of all intervals lying in the finite test

![]() $T_i^n$

(note that

$T_i^n$

(note that

![]() $Y_i^n$

can be represented as a disjoint union of finitely many intervals). For every i, let

$Y_i^n$

can be represented as a disjoint union of finitely many intervals). For every i, let

![]() $Y_i$

denote the union of the sets

$Y_i$

denote the union of the sets

![]() $Y_i^0,Y_i^1,\dots $

.

$Y_i^0,Y_i^1,\dots $

.

The property (11) can be obtained from the following three claims.

Claim 1. For every i and n, it holds that

Claim 2. For every i and n, it holds that

Claim 3. For every i, the following implication holds:

From the first two claims we easily obtain that the Lebesgue measure of the set

![]() $Y_i$

is also bounded by

$Y_i$

is also bounded by

![]() $2^{-(i+1)}$

for every i.

$2^{-(i+1)}$

for every i.

For all i and

![]() $n> 0$

,

$n> 0$

,

![]() $Y_i^n\setminus Y_i^{n-1}$

is a disjoint union of finitely many intervals, wherein a list of intervals is computable in i and n because the same holds for

$Y_i^n\setminus Y_i^{n-1}$

is a disjoint union of finitely many intervals, wherein a list of intervals is computable in i and n because the same holds for

![]() $Y_i^n$

and

$Y_i^n$

and

![]() $Y_i^{n-1}$

.

$Y_i^{n-1}$

.

Accordingly, the set

![]() $Y_i$

is equal to the union of a set

$Y_i$

is equal to the union of a set

![]() $S_i$

of intervals with rational endpoints that is effectively enumerable in i and where the sum of the measures of these intervals is at most

$S_i$

of intervals with rational endpoints that is effectively enumerable in i and where the sum of the measures of these intervals is at most

![]() $2^{-(i+1)}$

. By the latter two properties, the sequence

$2^{-(i+1)}$

. By the latter two properties, the sequence

![]() $S_0,S_1,\dots $

is a Martin-Löf test.

$S_0,S_1,\dots $

is a Martin-Löf test.

The real

![]() $\beta $

is Martin-Löf random, hence the test

$\beta $

is Martin-Löf random, hence the test

![]() $S_0,S_1,\dots $

should fail on

$S_0,S_1,\dots $

should fail on

![]() $\beta $

. Therefore, we can fix an index i such that

$\beta $

. Therefore, we can fix an index i such that

![]() $\beta $

is not contained in

$\beta $

is not contained in

![]() $Y_i$

. By Claim 3, we obtain that

$Y_i$

. By Claim 3, we obtain that

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

via g with the Solovay constant

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

via g with the Solovay constant

![]() $2^{i+2}$

, which implies (11) directly by definition of

$2^{i+2}$

, which implies (11) directly by definition of

![]() ${\le }_{\mathrm {S}} $

.

${\le }_{\mathrm {S}} $

.

It remains to construct the finite test

![]() $T_i^n$

uniformly in i and n and to check that Claims 1–3 are fulfilled.

$T_i^n$

uniformly in i and n and to check that Claims 1–3 are fulfilled.

Outline of the construction and some properties of the finite test

$T_i^n$

$T_i^n$

Fix

![]() $n,i\geq 0$

. We describe the construction of the finite test

$n,i\geq 0$

. We describe the construction of the finite test

![]() $T_i^n$

, which is a reworked version of a construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.1] in connection with left-c.e. reals.

$T_i^n$

, which is a reworked version of a construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.1] in connection with left-c.e. reals.

Recall that

![]() $p_0,\dots ,p_n$

are the first

$p_0,\dots ,p_n$

are the first

![]() $n+1$

elements of the fixed effective enumeration of the domain of g, and let

$n+1$

elements of the fixed effective enumeration of the domain of g, and let

![]() $\{q_0 < \cdots < q_n\}$

where

$\{q_0 < \cdots < q_n\}$

where

![]() $\{p_0,\dots ,p_n\}$

is equal to

$\{p_0,\dots ,p_n\}$

is equal to

![]() $\{q_0,\dots ,q_n\}$

. For technical reasons, let

$\{q_0,\dots ,q_n\}$

. For technical reasons, let

![]() $q_{n+1} = 1$

. In the remainder of this proof, every index refers to a number in the range between

$q_{n+1} = 1$

. In the remainder of this proof, every index refers to a number in the range between

![]() $0$

and n, unless stated otherwise. For indices k and l, where

$0$

and n, unless stated otherwise. For indices k and l, where

![]() $k < l$

, let

$k < l$

, let

and call the pair

![]() $(k,l)$

expanding if, first,

$(k,l)$

expanding if, first,

![]() $k<l$

and, second,

$k<l$

and, second,

$$\begin{align*}q_k + \delta(k,l)> q_l, \quad \text{ or, equivalently, } \quad \frac{g(q_l) - g(q_k)}{q_l - q_k} > 2^{i+1}, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}q_k + \delta(k,l)> q_l, \quad \text{ or, equivalently, } \quad \frac{g(q_l) - g(q_k)}{q_l - q_k} > 2^{i+1}, \end{align*}$$

and nonexpanding, otherwise. For further use, observe that, since g is nondecreasing, by definition, the relations of being an expanding pair and of being a nonexpanding pair are both transitive in the sense that, if the pairs

![]() $(k,l)$

and

$(k,l)$

and

![]() $(l,m)$

are expanding, then the pair

$(l,m)$

are expanding, then the pair

![]() $(k,m)$

is expanding, and the latter implication remains valid with “expanding” replaced by “nonexpanding”. The following somewhat technical observation is also straightforward.

$(k,m)$

is expanding, and the latter implication remains valid with “expanding” replaced by “nonexpanding”. The following somewhat technical observation is also straightforward.

Claim 4. For a nonexpanding pair

![]() $(k,l)$

and an index

$(k,l)$

and an index

![]() $m>l$

, it holds that

$m>l$

, it holds that

![]() ${q_k + \delta (k,m) \leq q_l + \delta (l,m)}$

.

${q_k + \delta (k,m) \leq q_l + \delta (l,m)}$

.

Further, for all indices k and m, define the interval

$$ \begin{align} I[{k},{m}] = \begin{cases} [q_m, q_k+ \delta(k,m) ],&\text{ if } (k,m) \text{ is an expanding pair}, \\ \emptyset, &\text{ otherwise}. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} I[{k},{m}] = \begin{cases} [q_m, q_k+ \delta(k,m) ],&\text{ if } (k,m) \text{ is an expanding pair}, \\ \emptyset, &\text{ otherwise}. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

Note that the interval

![]() $I[{k},{m}] $

has nonzero length

$I[{k},{m}] $

has nonzero length

![]() $\delta (k,m) - (q_m - q_k)$

in case

$\delta (k,m) - (q_m - q_k)$

in case

![]() $(k,m)$

is an expanding pair and is empty otherwise; the latter includes the case

$(k,m)$

is an expanding pair and is empty otherwise; the latter includes the case

![]() $m \le k$

.

$m \le k$

.

For all pairs

![]() $(k,m)$

of indices such that the interval

$(k,m)$

of indices such that the interval

![]() $I[{k},{m}] $

is nonempty, put the intersection of this interval with the unit interval

$I[{k},{m}] $

is nonempty, put the intersection of this interval with the unit interval

![]() $[0,1]$

into the test

$[0,1]$

into the test

![]() $T_i^n$

.

$T_i^n$

.

The following inclusion property of particular intervals can easily be implied from the construction.

Claim 5. For an expanding pair

![]() $(k,l)$

and all m, it holds that

$(k,l)$

and all m, it holds that

![]() ${I[{k},{m}] \supseteq I[{l},{m}] }$

.

${I[{k},{m}] \supseteq I[{l},{m}] }$

.

Preliminaries for the proof of Claim 1

Let

![]() $0=z_0<z_1<\dots <z_s$

be the indices in the range

$0=z_0<z_1<\dots <z_s$

be the indices in the range

![]() $0,\dots ,n$

such that

$0,\dots ,n$

such that

and, for every

![]() $j\in \{0,\dots ,s-1\}$

,

$j\in \{0,\dots ,s-1\}$

,

Further, for technical reasons, we fix an additional index

![]() $z_{s+1} = n+1$

(hence

$z_{s+1} = n+1$

(hence

![]() $z_{s+1}-1 = n$

) and set

$z_{s+1}-1 = n$

) and set

![]() $q_{n+1} = 1$

and

$q_{n+1} = 1$

and

![]() $g(q_{n+1}) = 1$

, so (13) means just (15) for

$g(q_{n+1}) = 1$

, so (13) means just (15) for

![]() $j = s$

.

$j = s$

.

Since, for every

![]() $j<s$

, the pair

$j<s$

, the pair

![]() $(z_j,z_{j+1})$

is nonexpanding by definition, the transitivity of nonexpanding property implies that

$(z_j,z_{j+1})$

is nonexpanding by definition, the transitivity of nonexpanding property implies that

Claim 6. For every

![]() $j\in \{0,\dots ,s\}$

and every real

$j\in \{0,\dots ,s\}$

and every real

![]() ${x\in (q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1}), q_{z_{j+1}})}$

, it holds that

${x\in (q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1}), q_{z_{j+1}})}$

, it holds that

![]() $x\notin I[{k},{l}] $

for all k and l in the range

$x\notin I[{k},{l}] $

for all k and l in the range

![]() $0,\dots ,n$

.

$0,\dots ,n$

.

Remark. Note that, in case

![]() $j<s$

, it holds by (14) that

$j<s$

, it holds by (14) that

![]() ${q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1})\leq q_{z_{j+1}}}$

, hence the interval

${q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1})\leq q_{z_{j+1}}}$

, hence the interval

![]() ${(q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1}), q_{z_{j+1}})}$

used in the Claim 6 is well-defined.

${(q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1}), q_{z_{j+1}})}$

used in the Claim 6 is well-defined.

In case

![]() $j = s$

, it may occur that

$j = s$

, it may occur that

![]() $q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1})> q_{z_{j+1}}$

, so, for every two reals

$q_{z_j} + \delta (z_j,z_{j+1})> q_{z_{j+1}}$

, so, for every two reals

![]() $a>b$

, let

$a>b$

, let

![]() $[a,b]$

conventionally denote an empty set.

$[a,b]$

conventionally denote an empty set.

Proof. By contradiction: assume that

![]() $x\in I[{k},{m}] $

for some

$x\in I[{k},{m}] $

for some

![]() $k,m$

where

$k,m$

where

![]() ${k<m}$

.

${k<m}$

.

First, we fix the index

![]() $h\in \{0,\dots ,s\}$

such that

$h\in \{0,\dots ,s\}$

such that

![]() $z_h\leq k<z_{h+1}$

. In case

$z_h\leq k<z_{h+1}$

. In case

![]() $k\neq z_j$

, we know from

$k\neq z_j$

, we know from

![]() $k<z_{h+1}$

that

$k<z_{h+1}$

that

![]() $(z_h,k)$

is an expanding pair. For that pair, Claim 5 implies that

$(z_h,k)$

is an expanding pair. For that pair, Claim 5 implies that

In case

![]() $k = z_h$

, (17) holds trivially.

$k = z_h$

, (17) holds trivially.

On the other hand, it holds that

Here, the second inequality is straightforward in case

![]() $h=j$

and follows from Claim 4 (since the pair

$h=j$

and follows from Claim 4 (since the pair

![]() $(z_h,z_j)$

is nonexpanding by (16)) in case

$(z_h,z_j)$

is nonexpanding by (16)) in case

![]() $h<j$

.

$h<j$

.

The contradiction follows because

![]() $q_{z_h} + \delta (z_h,m)$

in (18) is the right point of the interval

$q_{z_h} + \delta (z_h,m)$

in (18) is the right point of the interval

![]() $I[{z_h},{m}] $

, which contains x by (17).

$I[{z_h},{m}] $

, which contains x by (17).

The proof of Claim 1

Then, due to

$$\begin{align*}Y_i^n = \bigg( \bigcup_{k,l\in\{0,\dots,n\}}I[{k},{l}] \bigg) \cap [0,1],\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}Y_i^n = \bigg( \bigcup_{k,l\in\{0,\dots,n\}}I[{k},{l}] \bigg) \cap [0,1],\end{align*}$$

Claim 6 implies that

Hence we obtain that

with the measure

Therefore, by

where

![]() $A\overset {\cdot }{\cup } B$

denotes the union of two disjoint intervals A and B, we obtain an upper bound for the measure of

$A\overset {\cdot }{\cup } B$

denotes the union of two disjoint intervals A and B, we obtain an upper bound for the measure of

![]() $Y_i^n$

:

$Y_i^n$

:

$$ \begin{align*} \mu(Y_i^n) = \sum_{j=0}^s \mu\big(Y_i^n\cap (q_{z_j},q_{z_{j+1}})\big) \leq \sum_{j=0}^s \frac{g(q_{z_{j+1}})-g(q_{z_j})}{2^{i+1}} = \frac{g(q_{z_{s+1}}) - g(q_{z_0})}{2^{i+1}} \leq \frac{1}{2^{i+1}}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mu(Y_i^n) = \sum_{j=0}^s \mu\big(Y_i^n\cap (q_{z_j},q_{z_{j+1}})\big) \leq \sum_{j=0}^s \frac{g(q_{z_{j+1}})-g(q_{z_j})}{2^{i+1}} = \frac{g(q_{z_{s+1}}) - g(q_{z_0})}{2^{i+1}} \leq \frac{1}{2^{i+1}}. \end{align*} $$

Here, the first inequality follows from (19) applied for all j from

![]() $0$

to s, and the second one is implied by

$0$

to s, and the second one is implied by

![]() $g(q_0)\geq 0$

and

$g(q_0)\geq 0$

and

![]() $g(q_{z_{s+1}}) = g(q_{n+1}) = 1$

.

$g(q_{z_{s+1}}) = g(q_{n+1}) = 1$

.

The proof of Claim 2

Let

![]() $n,i\geq 0$

.

$n,i\geq 0$

.

The finite test

![]() $T_i^n$

is a subset of the finite test

$T_i^n$

is a subset of the finite test

![]() $T_i^{n+1}$

since every intersection of an interval

$T_i^{n+1}$

since every intersection of an interval

![]() $I[{k},{m}] $

, where

$I[{k},{m}] $

, where

![]() $0\leq k < m\leq n$

with

$0\leq k < m\leq n$

with

![]() $[0,1)$

added into the test

$[0,1)$

added into the test

![]() $T_i^n$

will also be added into the test

$T_i^n$

will also be added into the test

![]() $T_i^{n+1}$

as well. Hence we directly obtain that

$T_i^{n+1}$

as well. Hence we directly obtain that

$$\begin{align*}Y_i^n = \bigcup\limits_{I\in T_i^n} I \subseteq \bigcup\limits_{I\in T_i^{n+1}} I = Y_i^{n+1}.\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}Y_i^n = \bigcup\limits_{I\in T_i^n} I \subseteq \bigcup\limits_{I\in T_i^{n+1}} I = Y_i^{n+1}.\end{align*}$$

The proof of Claim 3

Fix an index i such that

![]() $\beta \notin Y_i$

. By Claim 2, it means inter alia that

$\beta \notin Y_i$

. By Claim 2, it means inter alia that

![]() $\beta \notin Y_i^n$

for every natural n.

$\beta \notin Y_i^n$

for every natural n.

We aim to show that

![]() $\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

via g with the Solovay constant

$\alpha {\le }_{\mathrm {S}} \beta $

via g with the Solovay constant

![]() $c = 2^{i+2}$

by contradiction: fixing a rational

$c = 2^{i+2}$

by contradiction: fixing a rational

![]() $q\in LC(\beta )$

such that

$q\in LC(\beta )$

such that

we can, by

![]() $\mathrm {dom}(g)\supseteq LC(\beta )$

, fix an index K such that

$\mathrm {dom}(g)\supseteq LC(\beta )$

, fix an index K such that

![]() $q = p_K$

. We know by definition of translation function that

$q = p_K$

. We know by definition of translation function that

![]() ${\lim \limits _{p\nearrow \beta }\big (g(p) - g(p_K)\big ) = \alpha - g(p_K)}$

, hence there exists

${\lim \limits _{p\nearrow \beta }\big (g(p) - g(p_K)\big ) = \alpha - g(p_K)}$

, hence there exists

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

such that

$\varepsilon>0$

such that

Fix an index

![]() $M>K$

such that

$M>K$

such that

![]() $p_M\in (\beta -\varepsilon ,\beta )$

. Note that (20) implies in particular that

$p_M\in (\beta -\varepsilon ,\beta )$

. Note that (20) implies in particular that

![]() $g(p_M)-g(p_K)>0$

, hence

$g(p_M)-g(p_K)>0$

, hence

![]() $p_K<p_M$

because the function g is nondecreasing.

$p_K<p_M$

because the function g is nondecreasing.

Let

![]() $\{q_0 < \cdots < q_M\}$

be the set

$\{q_0 < \cdots < q_M\}$

be the set

![]() $\{p_0,\dots ,p_M\}$

sorted increasingly, and let

$\{p_0,\dots ,p_M\}$

sorted increasingly, and let

![]() ${k,m\in \{0,\dots ,M\}}$

denote two indices such that

${k,m\in \{0,\dots ,M\}}$

denote two indices such that

![]() $q_k = p_K$

and

$q_k = p_K$

and

![]() $q_m = p_M$

. In particular, we have

$q_m = p_M$

. In particular, we have

![]() ${q_k=p_K<p_M=q_m}$

, hence

${q_k=p_K<p_M=q_m}$

, hence

![]() ${k<m}$

.

${k<m}$

.

To obtain a contradiction with

![]() $\beta \notin Y_i^M$

and conclude the proof of Claim 3, and thus also of (11), it suffices to show that

$\beta \notin Y_i^M$

and conclude the proof of Claim 3, and thus also of (11), it suffices to show that

![]() $\beta $

lies within one of the intervals of the finite test

$\beta $

lies within one of the intervals of the finite test

![]() $T_i^M$

, namely, in

$T_i^M$

, namely, in

![]() ${I[{k},{m}] \cap [0,1)}$

.

${I[{k},{m}] \cap [0,1)}$

.

Indeed,

![]() $\beta \in [0,1)$

holds obviously, and

$\beta \in [0,1)$

holds obviously, and

![]() $\beta \in I[{k},{m}] $

holds by (12) since

$\beta \in I[{k},{m}] $

holds by (12) since

where the right inequality is implied by (20) for

![]() $p=q_m$

.

$p=q_m$

.

2.2 The left limit exists

In this section, we show that, for q converging to

![]() $\beta $

from below, the fraction

$\beta $

from below, the fraction

![]() $\frac {\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}$

converges, i.e., that

$\frac {\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}$

converges, i.e., that

$$ \begin{align} \exists\lim_{q\nearrow \beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \exists\lim_{q\nearrow \beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}, \end{align} $$

by contradiction. For all

![]() $q\in LC(\beta )$

, the fraction

$q\in LC(\beta )$

, the fraction

![]() $\frac {\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}$

is obviously positive and, by the previous section, bounded; consequently, supposing that the left limit in (21) does not exist, we can fix two rational constants c and d where

$\frac {\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}$

is obviously positive and, by the previous section, bounded; consequently, supposing that the left limit in (21) does not exist, we can fix two rational constants c and d where

$$ \begin{align} c<d, \quad d-c <1, \text{ and } \liminf\limits_{q\nearrow \beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}<c<d<\limsup\limits_{q\nearrow \beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} c<d, \quad d-c <1, \text{ and } \liminf\limits_{q\nearrow \beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}<c<d<\limsup\limits_{q\nearrow \beta}\frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} \end{align} $$

and the rational

For a given finite subset Q of the domain of g, we will construct a finite test

![]() $M(Q) $

by an extension of a construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.2] in the left-c.e. case (the extension is needed since the original Miller’s construction may not satisfy Claim 9 stated below if the enumeration of the domain of g is not increasing). The construction is effective in the sense that it always terminates and yields the test

$M(Q) $

by an extension of a construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.2] in the left-c.e. case (the extension is needed since the original Miller’s construction may not satisfy Claim 9 stated below if the enumeration of the domain of g is not increasing). The construction is effective in the sense that it always terminates and yields the test

![]() $M(Q) $

in case it is applied to a finite subset of

$M(Q) $

in case it is applied to a finite subset of

![]() $\mathrm {dom}(g)$

.

$\mathrm {dom}(g)$

.

Further, for every finite subset Q of the domain of g and every real p, we define two functions

![]() ${\tilde {k}_{Q}({p})} $

and

${\tilde {k}_{Q}({p})} $

and

![]() ${K_{Q}({p})} $

from

${K_{Q}({p})} $

from

![]() $[0,1]$

to

$[0,1]$

to

![]() $\mathbb {N}$

by

$\mathbb {N}$

by

That is, for a given real p and a given finite subset Q of

![]() $\mathrm {dom}(g)$

, the function

$\mathrm {dom}(g)$

, the function

![]() ${\tilde {k}_{Q}({p})} $

returns the number of intervals containing p in the finite test

${\tilde {k}_{Q}({p})} $

returns the number of intervals containing p in the finite test

![]() $M(Q) $

defined on Q, and the function

$M(Q) $

defined on Q, and the function

![]() ${K_{Q}({p})} $

returns the maximal number of intervals containing p among the finite tests

${K_{Q}({p})} $

returns the maximal number of intervals containing p among the finite tests

![]() $M(H) $

defined on all possible subsets H of Q.

$M(H) $

defined on all possible subsets H of Q.

The desired contradiction can be obtained from the following three claims.

Claim 7. Let

![]() $Q_0 \subseteq Q_1 \subseteq \cdots $

be a sequence of finite sets that converges to the domain of g. Then it holds that

$Q_0 \subseteq Q_1 \subseteq \cdots $

be a sequence of finite sets that converges to the domain of g. Then it holds that

Claim 8. For every finite subset Q of the domain of g, it holds that

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits _0^1 {\tilde{k}_{Q}({x})} dx = \mu\big(M(Q) \big) \leq g(\max Q) - g(\min Q). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits _0^1 {\tilde{k}_{Q}({x})} dx = \mu\big(M(Q) \big) \leq g(\max Q) - g(\min Q). \end{align} $$

Claim 9. For every finite subset Q of the domain of g and for every nonrational real p in

![]() $[0,e]$

, it holds that

$[0,e]$

, it holds that

Remind that

![]() $p_0, p_1, \dots $

is an effective enumeration without repetition of the domain of g and

$p_0, p_1, \dots $

is an effective enumeration without repetition of the domain of g and

![]() $Q_n = \{p_0, \dots , p_n\}$

for

$Q_n = \{p_0, \dots , p_n\}$

for

![]() $n=0,1, \dots $

. We consider a special type of step function with domain

$n=0,1, \dots $

. We consider a special type of step function with domain

![]() $[0,1]$

that is given by a partition of the unit interval into finitely many intervals with rational endpoints such that the function is constant on the corresponding open intervals but may have arbitrary values at the endpoints. For the scope of this proof, a designated interval of such a step function is an interval that is the closure of a maximum contiguous open interval on which the function attains the same value. That is, the designated intervals form a partition of the unit interval except that two designated intervals may share an endpoint. Observe that, for every finite subset H of the domain of g, the corresponding cover function

$[0,1]$

that is given by a partition of the unit interval into finitely many intervals with rational endpoints such that the function is constant on the corresponding open intervals but may have arbitrary values at the endpoints. For the scope of this proof, a designated interval of such a step function is an interval that is the closure of a maximum contiguous open interval on which the function attains the same value. That is, the designated intervals form a partition of the unit interval except that two designated intervals may share an endpoint. Observe that, for every finite subset H of the domain of g, the corresponding cover function

![]() ${\tilde {k}_{H}({\cdot })} $

is such a step function with values in the natural numbers, and the same holds for the function

${\tilde {k}_{H}({\cdot })} $

is such a step function with values in the natural numbers, and the same holds for the function

![]() ${K_{Q_n}} (\cdot )$

since

${K_{Q_n}} (\cdot )$

since

![]() $Q_n$

has only finitely many subsets. Furthermore, for given n, the designated intervals of the function

$Q_n$

has only finitely many subsets. Furthermore, for given n, the designated intervals of the function

![]() ${K_{Q_n}({\cdot })} $

together with the endpoints and function value of every interval are given uniformly effective in n because g is computable and the construction of

${K_{Q_n}({\cdot })} $

together with the endpoints and function value of every interval are given uniformly effective in n because g is computable and the construction of

![]() $M(Q_n)$

is uniformly effective in n.

$M(Q_n)$

is uniformly effective in n.

For all natural numbers i and n, consider the step function

![]() ${K_{Q_n}} $

and its designated intervals. For every such interval, call its intersection with

${K_{Q_n}} $

and its designated intervals. For every such interval, call its intersection with

![]() $[0, e]$

its restricted interval. Let

$[0, e]$

its restricted interval. Let

![]() $X^n_i$

be the union of all restricted designated intervals where on the corresponding designated interval the function

$X^n_i$

be the union of all restricted designated intervals where on the corresponding designated interval the function

![]() ${K_{Q_n}} $

attains a value that is strictly larger than

${K_{Q_n}} $

attains a value that is strictly larger than

![]() $2^{i+2}$

. Let

$2^{i+2}$

. Let

![]() $X_i$

be the union of the sets

$X_i$

be the union of the sets

![]() $X^0_i, X^1_i, \dots $

.

$X^0_i, X^1_i, \dots $

.

By our assumption that the values of g are in

![]() $[0,1)$

and by (23), for all n, the integral of

$[0,1)$

and by (23), for all n, the integral of

![]() ${\tilde {k}_{Q_n}({p})} $

from

${\tilde {k}_{Q_n}({p})} $

from

![]() $0$

to

$0$

to

![]() $1$

is at most

$1$

is at most

![]() $1$

, hence by (24), the integral of

$1$

, hence by (24), the integral of

![]() ${K_{Q_n}({p})} $

from

${K_{Q_n}({p})} $

from

![]() $0$

to e is at most

$0$

to e is at most

![]() $2$

. Consequently, each set

$2$

. Consequently, each set

![]() $X^n_i$

has Lebesgue measure of at most

$X^n_i$

has Lebesgue measure of at most

![]() $2^{-(i+1)}$

. The latter upper bound then also holds for the Lebesgue measure of the set

$2^{-(i+1)}$

. The latter upper bound then also holds for the Lebesgue measure of the set

![]() $X_i$

for every i since, by the maximization in the definition of

$X_i$

for every i since, by the maximization in the definition of

![]() ${K_{Q_n}} $

and

${K_{Q_n}} $

and

By construction, for all i and

![]() $n>0$

, the difference

$n>0$

, the difference

![]() $X^n_i \setminus X^{n-1}_i$

is equal to the union of finitely many intervals that are mutually disjoint except possibly for their endpoints, and a list of these intervals is uniformly computable in i and n since the functions

$X^n_i \setminus X^{n-1}_i$

is equal to the union of finitely many intervals that are mutually disjoint except possibly for their endpoints, and a list of these intervals is uniformly computable in i and n since the functions

![]() ${K_{Q_n}} $

are uniformly computable in n. Accordingly, the set

${K_{Q_n}} $

are uniformly computable in n. Accordingly, the set

![]() $X_i$

is equal to the union of a set

$X_i$

is equal to the union of a set

![]() $U_i$

of intervals with rational endpoints that is effectively enumerable in i and where the sum of the measures of these intervals is at most

$U_i$

of intervals with rational endpoints that is effectively enumerable in i and where the sum of the measures of these intervals is at most

![]() $2^{-(i+1)}$

. By the two latter properties, the sequence

$2^{-(i+1)}$

. By the two latter properties, the sequence

![]() $U_0, U_1, \dots $

is a Martin-Löf test. By Claim 7, the values

$U_0, U_1, \dots $

is a Martin-Löf test. By Claim 7, the values

![]() ${K_{Q_n}({e {{\beta }}})} $

tend to infinity, where

${K_{Q_n}({e {{\beta }}})} $

tend to infinity, where

![]() $e {{\beta }}< e$

, hence for all i, the Martin-Löf random real

$e {{\beta }}< e$

, hence for all i, the Martin-Löf random real

![]() $e {{\beta }}$

is contained in some interval in

$e {{\beta }}$

is contained in some interval in

![]() $U_i$

, a contradiction. This concludes the proof that Claims 7–9 together imply that the left limit (21) exists.

$U_i$

, a contradiction. This concludes the proof that Claims 7–9 together imply that the left limit (21) exists.

It remains to construct the finite test

![]() $M(Q) $

for a given finite subset Q of the domain of g and to check that Claims 7–9 are fulfilled.

$M(Q) $

for a given finite subset Q of the domain of g and to check that Claims 7–9 are fulfilled.

The intervals that are used

First, we define two partial computable functions

![]() $\gamma $

and

$\gamma $

and

![]() $\delta $

that have the same domain as g:

$\delta $

that have the same domain as g:

Due to

![]() $c < d$

, the following claim is immediate.

$c < d$

, the following claim is immediate.

Claim 10. Whenever

![]() $g(q)$

is defined, we have

$g(q)$

is defined, we have

In particular, the partial function

![]() $\gamma - \delta $

is strictly increasing on its domain, hence, for every sequence

$\gamma - \delta $

is strictly increasing on its domain, hence, for every sequence

![]() $q_0 < q_1 < \dots $

of rationals on

$q_0 < q_1 < \dots $

of rationals on

![]() $[0,\beta )$

that converges to

$[0,\beta )$

that converges to

![]() $\beta $

, the values

$\beta $

, the values

![]() $g(q_i)$

are defined, and, therefore, the values

$g(q_i)$

are defined, and, therefore, the values

![]() $\gamma (q_i) - \delta (q_i)$

converge strictly increasingly to

$\gamma (q_i) - \delta (q_i)$

converge strictly increasingly to

![]() $(d-c)\beta $

.

$(d-c)\beta $

.

Now, for given rationals p and q, we define the interval

From this definition and the definitions of

![]() $\gamma $

and

$\gamma $

and

![]() $\delta $

, the following claim is immediate. Note that Assertion (iii) in the claim relates to expanding an interval at the right endpoint.

$\delta $

, the following claim is immediate. Note that Assertion (iii) in the claim relates to expanding an interval at the right endpoint.

Claim 11.

-

(i) Any interval of the form

$R[{p},{q}] $

has the left endpoint

$R[{p},{q}] $

has the left endpoint

$e {{p}}$

.

$e {{p}}$

. -

(ii) Consider an interval of the form

$R[{p},{q}] $

. In case

$R[{p},{q}] $

. In case

$\gamma (p) \le \gamma (q)$

, the interval has length

$\gamma (p) \le \gamma (q)$

, the interval has length

$\gamma (q)- \gamma (p)$

, otherwise, the interval is empty. In particular, any interval of the form

$\gamma (q)- \gamma (p)$

, otherwise, the interval is empty. In particular, any interval of the form

$R[{p},{p}] $

has length

$R[{p},{p}] $

has length

$0$

.

$0$

. -

(iii) Let

$R[{p},{q}] $

be a nonempty interval, and assume

$R[{p},{q}] $

be a nonempty interval, and assume

$\gamma (q) \le \gamma (q^{\prime })$

. Then the interval

$\gamma (q) \le \gamma (q^{\prime })$

. Then the interval

$R[{p},{q}] $

is a subset of the interval

$R[{p},{q}] $

is a subset of the interval

$R[{p},{q^{\prime }}] $

, both intervals have the same left endpoint

$R[{p},{q^{\prime }}] $

, both intervals have the same left endpoint

$e {{p}}$

, and they differ in length by

$e {{p}}$

, and they differ in length by

$\gamma (q^{\prime }) - \gamma (q)$

.

$\gamma (q^{\prime }) - \gamma (q)$

.

By choice (22) of c and d, the real

![]() $\beta $

is an accumulation point of both the sets

$\beta $

is an accumulation point of both the sets

$$ \begin{align} S &= \{q < \beta \colon \frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}> d \} = \{q < \beta \colon \delta(q) < \alpha - d\beta \}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} S &= \{q < \beta \colon \frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q}> d \} = \{q < \beta \colon \delta(q) < \alpha - d\beta \}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} T &= \{q < \beta \colon \frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} < c \} \; = \{q < \beta \colon \gamma(q)> \alpha - c\beta \}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} T &= \{q < \beta \colon \frac{\alpha - g(q)}{\beta - q} < c \} \; = \{q < \beta \colon \gamma(q)> \alpha - c\beta \}. \end{align} $$

The following properties of sets S and T, which have already been used in the left-c.e. case [Reference Barmpalias and Lewis-Pye1, Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9], will be crucial in the proof of Claim 7.

Claim 12.

-

1. The sets S and T are disjoint.

-

2. For all

$q\in S$

and

$q\in S$

and

$q^{\prime }\in T$

, the interval

$q^{\prime }\in T$

, the interval

$R[{q},{q^{\prime }}] $

contains

$R[{q},{q^{\prime }}] $

contains

$e {{\beta }}$

.

$e {{\beta }}$

.

Proof. The first statement is straightforward from the left parts of (25) and (26), respectively. By definition, the interval

![]() $R[{q},{q^{\prime }}] $

has the left endpoint

$R[{q},{q^{\prime }}] $

has the left endpoint

![]() $e {{q}}$

and the right endpoint

$e {{q}}$

and the right endpoint

![]() $\gamma (q^{\prime })-\delta (q)$

. By definition of the sets S and T, on the one hand, we have

$\gamma (q^{\prime })-\delta (q)$

. By definition of the sets S and T, on the one hand, we have

![]() $q < \beta $

, hence

$q < \beta $

, hence

![]() $e {{q}}<e {{\beta }}$

, on the other hand, we have

$e {{q}}<e {{\beta }}$

, on the other hand, we have

Outline of the construction of the finite test

$M(Q) $

$M(Q) $

We fix a nonempty finite subset

![]() ${Q=\{q_0 < \cdots < q_n\}}$

of the domain of g. Here, the notation used to describe Q has its obvious meaning, i.e.,

${Q=\{q_0 < \cdots < q_n\}}$

of the domain of g. Here, the notation used to describe Q has its obvious meaning, i.e.,

![]() $Q =\{q_0, \dots , q_n\}$

, and

$Q =\{q_0, \dots , q_n\}$

, and

![]() $q_i < q_{i+1}$

for all i. Note that—in contrast to Section 2.2—

$q_i < q_{i+1}$

for all i. Note that—in contrast to Section 2.2—

![]() $q_0,\dots ,q_n$

do not need to be the first

$q_0,\dots ,q_n$

do not need to be the first

![]() $n+1$

elements of the effective enumeration of

$n+1$

elements of the effective enumeration of

![]() $\mathrm {dom}(g)$

. We describe the construction of the finite test

$\mathrm {dom}(g)$

. We describe the construction of the finite test

![]() $M(Q) $

, which is an extended version of a construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.2] in connection with left-c.e. reals. Using the notation defined in the previous paragraphs, for all i in

$M(Q) $

, which is an extended version of a construction used by Miller [Reference Miller, Day, Fellows, Greenberg, Khoussainov, Melnikov and Rosamond9, Lemma 1.2] in connection with left-c.e. reals. Using the notation defined in the previous paragraphs, for all i in

![]() $\{0, \dots , n\}$

, let

$\{0, \dots , n\}$

, let

$$ \begin{align*} \delta_{{i}} &= \delta(q_i) = g(q_i) - d q_i, \\ \gamma_{{i}} &= \gamma(q_i) = g(q_i) - cq_i, \\ J[{i},{j}] &= R[{q_i},{q_j}] = [\gamma(q_i) - \delta(q_i), \gamma(q_j) - \delta(q_i)] = [e {{q_i}}, \gamma_{{j}} - \delta_{{i}}]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \delta_{{i}} &= \delta(q_i) = g(q_i) - d q_i, \\ \gamma_{{i}} &= \gamma(q_i) = g(q_i) - cq_i, \\ J[{i},{j}] &= R[{q_i},{q_j}] = [\gamma(q_i) - \delta(q_i), \gamma(q_j) - \delta(q_i)] = [e {{q_i}}, \gamma_{{j}} - \delta_{{i}}]. \end{align*} $$

The properties of the intervals of the form

![]() ${R[{p},{q}] }$

extend to the intervals

${R[{p},{q}] }$

extend to the intervals

![]() ${J[{i},{j}] }$

: for example, any two nonempty intervals of the form

${J[{i},{j}] }$

: for example, any two nonempty intervals of the form

![]() ${J[{i},{j}] }$

and

${J[{i},{j}] }$

and

![]() ${J[{i},{j^{\prime }}] }$

have the same left endpoint, i.e.,

${J[{i},{j^{\prime }}] }$

have the same left endpoint, i.e.,

![]() ${\min J[{i},{j}] }$

and

${\min J[{i},{j}] }$

and

![]() ${\min J[{i},{j'}] }$

are the same for all i, j, and

${\min J[{i},{j'}] }$

are the same for all i, j, and

![]() $j'$

.

$j'$

.

The test

![]() $M(Q) $

is constructed in successive steps

$M(Q) $

is constructed in successive steps

![]() $j=0, 1, \dots , n$

, where, at each step j, intervals

$j=0, 1, \dots , n$

, where, at each step j, intervals

![]() $U_{0}^{j} , \dots , U_{n}^{j} $

are defined. Every such interval has the form

$U_{0}^{j} , \dots , U_{n}^{j} $

are defined. Every such interval has the form

for some index

![]() $k\in \{0, \dots , n\}$

, where

$k\in \{0, \dots , n\}$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol {r}^{j}({\cdot }) $

is an index-valued function that maps every index i to such index k that

$\boldsymbol {r}^{j}({\cdot }) $

is an index-valued function that maps every index i to such index k that

![]() $J[{i},{k}] = U_{i}^{j} $

.

$J[{i},{k}] = U_{i}^{j} $

.

At step

![]() $0$

, for

$0$

, for

![]() $i=0, \dots , n$

, we set the values of the function

$i=0, \dots , n$

, we set the values of the function

![]() $\boldsymbol {r}^{0}({i}) $

by

$\boldsymbol {r}^{0}({i}) $

by

and initialize the intervals

![]() $U_{i}^{0} $

as zero-length intervals

$U_{i}^{0} $

as zero-length intervals

In the subsequent steps, every change of an interval amounts to an expansion at the right end in the sense that, for all indices i, the intervals

![]() $U_{i}^{0} , \dots , U_{i}^{n} $

share the same left endpoint, while their right endpoints are nondecreasing. More precisely, as we will see later, for