Introduction

At the center of research on affective polarization is the question of how citizens think about and evaluate members of in- and out-groups. This research has shown that interpersonal affective evaluations, i.e., whether individuals in a society like or dislike each other, strongly depend on whether individuals share political values and group identities (Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). These affective evaluations have important societal implications, leading to stereotyping, bias, and prejudice (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019), which can in turn influence real-world behavior such as hiring (Gift and Gift Reference Gift and Gift2015; Michelitch Reference Michelitch2015). There may also be a negative effect on democratic norms (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Kingzette, Druckman, Klar et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021), but this is still debated in recent research (Broockman, Kalla, and Westwood Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2023; Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro et al. Reference Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro, Mernyk, Redekopp, Pink, Druckman, Rand and Willer2023).

The dominant accounts of the political characteristics that determine these affective evaluations focus on partisanship in the United States. Building on a social identity perspective (West and Iyengar Reference West and Iyengar2022), researchers present consistent evidence that Americans view those with a shared partisanship more positively and those with an opposing one more negatively (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). Moreover, researchers have also shown that negative outpartisan affect, i.e., the dislike and hostility individuals feel towards people who support and feel close to opposing parties, has been increasing in the US over recent decades (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015).

Yet, applying this framework to Europe is less straightforward. On the one hand, research indeed finds that levels of affective polarization in Europe and the United States are not vastly different (Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner Reference Wagner2021; Garzia, Ferreira da Silva, and Maye Reference Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Maye2023), even if the negative trends found in the US are less pronounced there. Experimental research also finds that partisanship matters for affective evaluations to a similar degree in Europe and the US, and that this effect is stronger than for demographic groups (Huddy, Bankert, and Davies Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018; Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, et al. Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018; Helbling and Jungkunz Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Hahm, Hilpert, and König Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024). On the other hand, partisan identification has been found to be less central to political conflict in Europe than social groups, policy divides, and ideological divisions (Lipset et al. Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024). Survey reports indicate that partisanship is generally declining (Dalton and Wattenberg Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2002; Oscarsson and Holmberg Reference Oscarsson and Holmberg2020). The smaller role for partisan identities may stem from the fact that many European party systems are characterized by impermanence and flux, limiting the development of strong attachment to partisan groups. In addition, voters in Europe often switch between parties quite happily but tend to do so within broader ideological blocs (Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair2007; Rahat, Hazan, and Ben-Nun Bloom Reference Rahat, Hazan and Ben-Nun Bloom2016). Accordingly, citizens see most multiparty systems as divided into a smaller number of two or three ‘camps’ (Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021; Bantel Reference Bantel2023), with parties forming clusters in terms of how citizens feel about them and choose between them.

This creates an important puzzle. Empirically, the effects of partisanship on interindividual affect are similar to those in the US, with voters reacting strongly to these group labels (Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018; Helbling and Jungkunz Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024). Yet, there are clear reasons to doubt the applicability of a strongly partisan lens to European politics, as partisan identities have been declining and ideological divides remain relevant.

We argue that, to fully understand how politics influences the affect citizens feel towards each other, we need to go beyond partisan social identities. We build on recent research that has emphasized that social identities can also form around opinion-based divisions, such as Brexit, regionalism, Covid, or European integration (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021; Rodon Reference Rodon2022; Balcells and Kuo Reference Balcells and Kuo2023; Hahm, Hilpert, and König Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2023; Wagner and Eberl Reference Wagner and Eberl2024). However, we focus on a more general and long-lived type of opinion-based identity centered around ideology and ideological labels (Levitin and Miller Reference Levitin and Miller1979; Conover and Feldman Reference Conover and Feldman1981; Ellis and Stimson Reference Ellis and Stimson2012; Devine Reference Devine2015; Mason Reference Mason2018). These ideological identities are what Ellis and Stimson (Reference Ellis and Stimson2012) call ‘symbolic ideology’, i.e., how one sees and defines oneself in relation to others; this is distinct from ‘operational ideology’, i.e., the policy preferences one holds. In the United States, the most relevant ideological identities are Conservative and Liberal/Progressive, while in many other contexts, these identities are based on the labels Left and Right. In many European party systems, ideological identities could provide stable anchors in a volatile political world: even if the parties that defend left- or right-wing views merge, splinter, or disappear, a voter’s ideological home can stay the same for decades. Given the importance that ideological identities likely play for citizens in many countries, these should also impact our affective evaluations of other individuals (Comellas and Torcal Reference Comellas and Torcal2023).

In this paper, we therefore explore whether ideological identities shape political affect between citizens in Europe. Specifically, we test whether individuals react to ideological identities in ways that mirror reactions to partisan identities (Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020). We also assess whether ideological identities still matter when we include key additional information relating to not just partisanship but also policy stances and political engagement (Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022). We also examine whether those with stronger ideological identities react more to ideological labels than those with weaker such identities. We carry out our study in Germany, which is a particularly useful case to test the influence of ideological identities on affective evaluations, as both partisan and ideological identities are potentially relevant (Neundorf Reference Neundorf2011; Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2017).

Empirically, we carry out a variation of the standard conjoint analysis survey experiment (Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins et al. Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, Yamamoto, Druckman and Green2021), in a design that follows that used by Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020) in varying the number of attributes different respondents see. Participants are asked how warmly they feel towards hypothetical individuals that randomly vary in a set of political and non-political characteristics. Importantly, these vignettes vary not just in the levels of the attributes shown but also in the number of attributes presented to respondents. This allows us to eliminate problems of masking and estimate the controlled direct effect (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018), thereby enabling us to examine whether specific attributes remain relevant when other characteristics are known. While this design builds directly on recent work by Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020), our paper is innovative in three aspects: we clearly measure reactions to explicitly specified ideological labels commonly used in everyday conversation; we assess how individuals’ own ideological identities matter for how they react to these labels; and we implement an experimental design that allows us to assess the relevance of ideological labels even when other information is present.

Our findings are clear: ideological identities matter to German citizens. Many individuals in our survey possess an ideological affiliation, and the average strength of ideological identities is similar to that of partisanship. In our experiment, respondents also base their feelings towards individuals on their ideological leanings, and this reaction is strongest for those who themselves have deep-seated ideological identities. The impact of information on ideological affiliation is similar in size to that for partisanship and remains relevant even when we include extensive other information for which ideological identities may act as a heuristic. Information on ideological identification also reduces reactions to partisanship. Nevertheless, we also show that shared policy stances are more important than shared identities, be it partisanship or ideology. In the conclusion, we discuss how our evidence on the importance of ideological identities should inform future research.

Political identities

Social identities are central to the study of political behavior (Huddy Reference Huddy2001). Individuals’ identities are based on self-categorization, i.e., the extent to which individuals see themselves as being part of a specific group or category (Malka and Lelkes Reference Malka and Lelkes2010). While to date, two types of social identities dominate political science research – based on parties and on social groups (Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024) – most current work has focused specifically on partisan social identities (Greene Reference Greene1999; Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004; Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015; Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018). While the study of partisanship has a long history across democratic systems (Oscarsson and Holmberg Reference Oscarsson and Holmberg2020), these identities have returned to the center of scholarly attention as part of the broader research agenda on affective polarization (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; West and Iyengar Reference West and Iyengar2022). Many voters, especially in the United States, develop strong, stable in-party social identities (Greene Reference Greene1999; Green et al. Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004). Despite initial critiques that suggest that these identities are mere ‘running tallies’ of party evaluations (Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981), there is now extensive evidence that partisanship functions as a social identity for many citizens (Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015; West and Iyengar Reference West and Iyengar2022).

Yet, the importance of partisanship remains debated, especially outside the United States (Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024). European party systems are characterized by more varied ties to social cleavages and are generally larger and more volatile, creating a more complex setting where partisan social identities may be less relevant. In Europe, key political divisions have primarily emerged bottom-up from social cleavages (Lipset et al. Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967): societal divisions based on ethnicity, race, religion, or class create identities, and political parties channel representation of these groups (Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair2007; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024). In contrast, analyses from the US emphasize how identities can be shaped top-down by partisan conflict that extends to the social sphere.

Second, the larger European party systems also likely create less social and ideological sorting, with more cross-cutting issues and allegiances (Dassonneville Reference Dassonneville2023). Moreover, party systems in Europe are more volatile. Overall, European citizens often have a large and varying menu of options to choose from, with less opportunity for long-lasting identities to form along party lines (Franklin and Van Spanje Reference Franklin and Van Spanje2012). Indeed, in multiparty systems citizens can also feel positive affect towards more than one party (Garry Reference Garry2007).

We argue that a more complete understanding of social identities in Europe needs to move beyond partisan and cleavage-based social identities to also consider ideological identities.

Ideological identities

In Europe, citizens often hold non-partisan political identities, centered around highly salient, divisive issues such as Brexit (Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021), Covid (Wagner and Eberl Reference Wagner and Eberl2025), territorial divisions (Rodon Reference Rodon2022; Balcells and Kuo Reference Balcells and Kuo2023), or European integration (Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2023). Such opinion-based identity groups may, however, be rather short-lived, declining once the motivating issue loses salience. However, a related but potentially more enduring form of opinion-based identity will be centered around ideologies. Following Ellis and Stimson (Reference Ellis and Stimson2012), we distinguish operational ideology – i.e., policy preferences – from symbolic ideology – i.e., whether one identifies as a Liberal/Conservative or Left/Right.

Operational ideology is the sum of the policy positions people take, and these positions are usually tied together by some ideological constraint based on ‘what goes with what’ (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964). Operational ideology refers to the familiar, rational-choice notion that individuals hold policy preferences over different issues and that these patterns of preferences can then be simplified to a smaller set of ideological dimensions, usually one or two.

In contrast, symbolic ideology refers to how individuals themselves describe themselves and what they identify as. Symbolic ideologies are thus social identities (Comellas and Torcal Reference Comellas and Torcal2023) and capture the fact that people see themselves and others as belonging to an ideological group. Ideological labels are used to situate oneself politically and socially and to categorize others. Following Mason (Reference Mason2018) and Oshri, Yair, and Huddy (Reference Oshri, Yair and Huddy2022), we use the term ‘ideological identities’ to refer to such symbolic ideology.

The social identities that form around ideologies do not form in a vacuum. In the United States, they are closely linked to the social groups associated with different ideological labels (Conover and Feldman Reference Conover and Feldman1981; Popp and Rudolph Reference Popp and Rudolph2011). More generally, other reasons why ideological identities will be adopted are parental and youth socialization (Green et al. Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004). In Europe, ideological identities may be of particular relevance. While in a two-party system, there should be a large overlap between ideological and partisan identities; in multiparty systems, ideological identities can play a more distinct role for two reasons (Oshri et al. Reference Oshri, Yair and Huddy2022; Peffley, Yair, and Hutchison Reference Peffley, Yair and Hutchison2024). First, and as mentioned above, the development and stabilization of partisan identities will be more challenging in volatile, complex party systems. Second, party systems are often characterized by comparatively stable patterns of cooperation, for example, in the form of regular government coalitions that create ideological camps (Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021; Bantel Reference Bantel2023). This within-bloc stability may encourage the formation of ideological identities even when parties are weak. The mixture of larger, volatile party systems coupled with stable patterns of cooperation within blocs of parties means that ideological identities may be more relevant and useful to voters in multiparty systems than partisan identities (Oshri et al. Reference Oshri, Yair and Huddy2022).

The distinction between an opinion-based social group and (symbolic) ideological identities is of degree rather than kind. In Europe, separatism (as in Catalonia) (Balcells and Kuo Reference Balcells and Kuo2023) or, more broadly, particularism-universalism (Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger et al. Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024) may function in the same way as Left and Right. Yet, two differences between opinion-based and ideological identities are important: first, ideological identities refer to a broader set of issue divides, subsumed under a simplifying label (‘Left’ or ‘Liberal’); and second, ideological identities are likely longer-lasting than opinion-based identities, as they are less dependent on the salience of one particular issue.

The relationship between policy stances and ideological identities is likely complex. Ideological labels are clearly associated with specific policy stances (Malka and Lelkes Reference Malka and Lelkes2010), such that the substantive context of Left and Right is largely stable across many countries (Lindqvist and Doernschneider-Elkink Reference Lindqvist and Doernschneider-Elkink2024). As Orr, Fowler, and Huber (Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023) note, ‘people choose their partisan identities for substantive reasons’, and the same is likely to apply to ideological identities. Yet, the causal direction is not one-way: ideological identities will also shape policy stances by helping citizens to know ‘what goes with what’ (Malka and Lelkes Reference Malka and Lelkes2010). Moreover, ideological identities are not solely the result of issue preferences or of operational ideological stances: empirically, symbolic and operational ideology are only modestly correlated (Mason Reference Mason2018), such that ideological identities only imperfectly match issue attitudes (Devine Reference Devine2015). Thus, many Americans with a liberal operational ideology identify as (symbolic) conservatives (Yeung and Quek Reference Yeung and Quek2025). Proponents of a symbolic ideology approach point to the lack of ideological sophistication among many citizens as a reason for this disjuncture (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964). Overall, we do not take a strong position on the knotty problem of the causal order of policy views, partisanship, and ideological identities, a matter of long-standing academic debate (Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020; West and Iyengar Reference West and Iyengar2022). Yet, while ideological identities and issue stances are inherently and endogenously related, we hold that they are nevertheless distinct phenomena. In this, ideological identities are similar to partisanship: they are connected to policy stances, but not coterminous with them.

Ideological identities and affective evaluations

So far, we have argued that citizens often develop social identities based on political divisions and that ideological conflict – such as the one between Left and Right – can provide one source for such identities. Importantly, political identities are not just relevant for how individuals see and think of themselves: they also determine how individuals evaluate each other (Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020; Peffley et al. Reference Peffley, Yair and Hutchison2024). Social identities mean that individuals categorize others into ingroups and outgroups, with the former seen as more virtuous and superior than the latter. While the tendency of ingroup love and outgroup hate to go together is not automatic (Brewer Reference Brewer2001), this is often the case for politics (Miller and Conover Reference Miller and Conover2015; Mason Reference Mason2018; Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020). As a result, social identities lead us to evaluate those who are part of our ingroup more positively and those in the outgroup more negatively (Comellas and Torcal Reference Comellas and Torcal2023; Peffley et al. Reference Peffley, Yair and Hutchison2024). Social identity theory predicts that these identities will lead to biased processing as well as behavior that will maintain ingroup norms and support the interests of the ingroup (Malka and Lelkes Reference Malka and Lelkes2010; Devine Reference Devine2015; Vegetti and Širinić Reference Vegetti and Širinić2019). Hence, our social identities shape our affective evaluations of individuals.

We have two basic expectations about how interpersonal affect changes depending on whether ideological identities are shared or not. Note that the aim of these initial hypotheses is to examine whether individuals adjust their interpersonal affect to information on ideological identities.Footnote 1

H1a: Citizens will have warmer feelings towards individuals who share their ideological identity than towards individuals who have a different ideological identity.

H1b: The effect of sharing ideological identities on affective evaluations will increase with the strength of individuals’ own ideological identities.

These two hypotheses are a first starting point; if they do not hold, then it is not worth investigating the role of ideological identities further. However, if they do, then one important concern is that the impact of ideological identities on affective evaluations merely reflects that these labels are taken as signals of other, more fundamental attributes: their political engagement, their partisan identity, or their policy stances. An individual identifying as part of the left, for example, is more likely to be politically engaged, to feel close to one of the left-wing parties, and to hold specific policy stances that are commonly classified as left-wing. We can therefore think of ideological identities as one of several pieces of relevant, correlated political information about individuals. The reasons underlying the mental association between ideological identities and other attributes will likely be complex. For instance, ideological and partisan identities may be the result of holding certain issue positions, but ideological and partisan identities will also shape issue positions. So, it is not the case that one attribute is the mediator while the other variables are the more fundamental causes. Untangling this causal web is not our aim here, but it is important to acknowledge the challenge posed by these mental associations.

A similar challenge has been identified for assessing the impact of partisan identities on affective evaluations (Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020): when people feel warmly towards their preferred party, and when they react positively or negatively to someone else’s partisanship, this might be due to the policy positions that this partisanship is a proxy for. Put simply, it is a challenge to discern whether people dislike out-party supporters because of their partisan identities or because of the policy views that lead them to develop and take on such identities. This also casts doubt on research that finds strong reactions to partisanship in Europe (Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018; Helbling and Jungkunz Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024), since reactions to partisan labels could emerge because they signify policy stances. This provides an explanation for why people still react strongly to partisan labels in Europe, even in contexts where partisanship is weak. Adding ideological identities to this mix only serves to make this complex web of associations more fraught.

In related, important work, Krupnikov and Ryan (Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022) argue that, for many individuals, it is in fact neither partisanship nor ideology nor policy stances that explain negative outpartisan affect. Instead, many people dislike talking about and discussing politics, instead preferring people who avoid the topic. Hence, part of the reason why people evaluate those with (strong) political views and identities more negatively is because these people are more willing to talk about politics. Dislike for all partisans needs to be distinguished from dislike for some partisans.

A skeptical observer could thus argue that the effect of ideological identities simply captures these other aspects of individuals, with citizens using ideological labels as a useful heuristic. Specifically, the concern is that reactions to ideological labels could in fact mainly reflect other political attributes that these ideological labels imply, most prominently policy positions. Given that the associations between parties, policies, engagement, and ideologies will be at least partly known among the public, the different attributes are likely to act as proxies and heuristics of one another. This ‘aliasing’ (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) or ‘masking’ Acharya et al. (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018) describes a situation where one feature of an individual stands in for another feature. Unfortunately, it is difficult to disentangle the distinct impact of identities and preferences on affective evaluations and provide a clear answer on whether affective evaluations respond to identities, engagement, or policy preferences.

Hypothesis 1b will provide evidence of a distinct impact of ideological identities, as it shows that the strength of ideological identification matters for affective evaluations. However, for additional evidence, we turn to work that examines partisan identities as a driver of affective evaluations. Here, Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020), Dias and Lelkes (Reference Dias and Lelkes2022), and Orr et al. (Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023) provide important advances to addressing the challenge that the various drivers of affective evaluations are often observationally equivalent.

If partisanship affects assessments of other related characteristics, i.e., if voters form inferences about policy preferences based on partisanship, then we cannot think of partisanship as only treating partisanship. Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020) address this issue by considering the effect of partisanship in isolation versus when other factors that one might reasonably infer based on partisanship are also present. When partisanship is the only information about an individual, it has a strong effect on feelings of warmth, but when policy information is also provided, the effect of partisanship is reduced considerably. However, Dias and Lelkes (Reference Dias and Lelkes2022) provide evidence that both partisan identity and policy disagreement independently drive interpersonal affect (though see also Orr et al. Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023). Clearly, distinguishing the effect of partisan labels and policy preferences is theoretically complex and empirically challenging.

In this paper, we build on this debate and expect that ideological identities will overlap with other attributes in similar ways to partisanship. In short, ideological labels and identities will be strongly related to policy preferences, political engagement, and partisanship. Hence, we test whether ideological identities remain relevant if we also provide information about partisanship, policy preferences, and political involvement (H2a–H2c).

In addition, we also examine what happens when ideological identities and policy stances are in conflict. This is another way of thinking about the relative importance of different characteristics: Do people prioritize matches on policy over matches on ideological identity? This hypothesis again builds on work on partisanship in the US, where Orr et al. (Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023) indeed find that respondents give priority to policy matches rather than partisan ones. Such a finding would provide some evidence that policy matters in a more fundamental way for interpersonal affect than ideological identities. Given the results of Orr et al. (Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023), we also expect policy matches to trump those for ideological identities (H3).

Our expectations are thus as follows:

H2a: The effect of sharing ideological identities on affective evaluations will decrease in the presence of information about partisanship.

H2b: The effect of sharing ideological identities on affective evaluations will decrease in the presence of information about policy preferences.

H2c: The effect of sharing ideological identities on affective evaluations will decrease in the presence of information on political engagement.

H3: When matches on ideological identities and policy stances conflict, voters’ affective evaluations of individuals are more strongly determined by the policy match.

Finally, our focus on ideological identities also allows us to reevaluate the emphasis placed on partisanship in existing research. Notably, the exchange between Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020) and Dias and Lelkes (Reference Dias and Lelkes2022) does not take ideological identities into account. In other words, the web of identities and preferences may be even more complex, as ideological identities may also matter. We argue that in many systems, ideological identities may play a role akin to or even larger than partisan identities. We examine whether accounting for ideological identities changes whether partisanship is a source of inter-voter affect and expect that:

H4: The effect of sharing partisanship on affective evaluations will decrease in the presence of information on ideological identity.

Research design

We run our study using left-right identities in Germany. In terms of the strength of ideological identities, Germany is likely to be a moderate case. In terms of affective polarization, Germany is in the middle of the distribution in cross-national comparisons (Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner Reference Wagner2021), and the impact of partisanship on affective polarization is comparable to other countries as well (Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024). While there are no studies examining how and why ideological identities vary in Europe, three sources of variation seem plausible. First, ideological identities should be more relevant when coalitions tend to occur within one ideological bloc (Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021; Bantel Reference Bantel2023), e.g., in Denmark or Sweden. Second, ideological identities should be less relevant in strongly multidimensional systems such as the Netherlands, as simple ideological camps will be harder to form when the underlying issue-based conflicts are more cross-cutting. Finally, ideological identities should be less relevant in systems with very stable party landscapes, such as Switzerland, as partisan identities can play a more central role there. Germany is a moderate case in all aspects: it has clear ideological blocs (with some cross-bloc coalitions), a largely unidimensional party system, and a limited amount of party system change. Moreover, the German case does not stack the deck against partisan identities by choosing a system with weak or transient parties (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2017), and levels of party identification are average in international comparison (Dalton Reference Dalton2021). We chose to examine Left and Right as ideological identities, as the comparatively stable party landscape, with ideologically based coalition formation, means that these are likely to hold meaning for German voters (Neundorf Reference Neundorf2011).

Our experimental design extends that of Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020). The experiment was preregistered at the Open Science Foundation [https://osf.io/3yst2].Footnote 2 Our design differs from that in Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020) in three key ways: first, we explicitly include ideological identities as a potential characteristic; second, we include three dominant policy issues rather than a single policy issue; and third, we follow Krupnikov and Ryan (Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022) and include political involvement as an explicit political characteristic.

In our survey (n = 2152), we present respondents with a single-profile conjoint experiment, with hypothetical individuals that vary in key characteristics (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). Vignettes are introduced with the sentence: ‘We would like to know your feelings toward people you might meet on an everyday basis’. Each respondent evaluated 12 profiles, each on a single screen. Online Appendix E provides evidence of the assumption of no carryover effects between profiles (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014, 8). Respondents rated, on a scale of 0–10, how likable they found each person (Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020). This is a central measure of partisan animosity that captures general attitudes towards a broad target; alternative outcomes, such as trust and trait ratings, tend to produce similar evaluations (Druckman and Levendusky Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019).

The profiles varied in up to nine characteristics: four political characteristics, specifically party support, left-right ideology, three policy stances (immigration, economy, and environment), and political engagement; and name, hobby, religion, music preferences, and home region. A full list of the possible levels of all characteristics is presented in Table 1. We used various ways of phrasing ideological identities, as there is no established way of describing this.Footnote 3 Note that we assigned party identity conditional on the respondent’s own partisanship so that we have enough respondents with matching partisanship.

For example, a vignette with all attributes might read, ‘Andreas lives in Brandenburg and is Catholic. His favorite hobby is hiking, and his favorite music is rap. He is a supporter of the FDP and would describe himself as politically right. He is for lower taxes, wants immigration to be as difficult and as low as possible, and is against a stronger fight against climate change. He rarely talks about politics’. Note that we rotated the order of the political attributes in the vignettes.

One important decision concerns whether to restrict combinations of attributes or not. It might be unlikely to meet someone who is an AfD supporter but sees himself as left-wing; in our sample, 9% of AfD supporters do so (see Online Appendix F, Table F.1). We decided against restricting combinations of our three political attributes (policy stances, ideological affiliation, and partisanship) to those that are most plausible because we start from the assumption that there is no necessary logical connection between all attributes. Empirically, all kinds of combinations do in fact occur (even if rarely). However, as a robustness check, we show and discuss results for analyses that remove the more improbable combinations of attributes (see Online Appendix C, Table C.2).

Additional important decisions relate to how to include policy issues in the vignette. In their similar study, Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020) only include one policy issue per vignette. We find this approach insufficient, as a respondent could infer a myriad of policy positions from an ideological stance. For instance, it is possible that a respondent dislikes a right-wing profile, not because of the stance on economic policy, but because of anti-immigration policies or disregard for the environment. While we cannot possibly cover all potentially relevant issues, we chose the three that we considered most salient to the current political debates in Germany. To avoid overemphasizing policy relative to party and ideology, we keep the policy positions short and within a single sentence.

A key feature of our design is that not all vignettes included information on all nine characteristics. Instead, we follow recent innovations in survey experimental methodology (see e.g., Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018; Clifford Reference Clifford2020; Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020; Nyholt Reference Nyholt2024) and present vignettes with selective aspects in order to uncover how additional information changes how respondents evaluate individuals. Rather than just exploring the effect of ideological labels on interpersonal affect, we aim to see whether there is evidence that the causal effect may flow through one or several mediators on a causal pathway, or whether ideology itself is a mediator for other variables. Our approach follows Acharya et al. (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018): we randomly vary the provision or withholding of the mediator and estimate the controlled direct effect by holding the mediator fixed. However, because we are applying this ‘logic of implicit mediation’ (Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018, 361) within a conjoint analysis, the average component marginal effect (ACME) is equivalent to the controlled direct effect. Of greater interest in this particular study is the eliminated effect, i.e., how the marginal effect of an attribute changes when the mediator is provided or withheld.

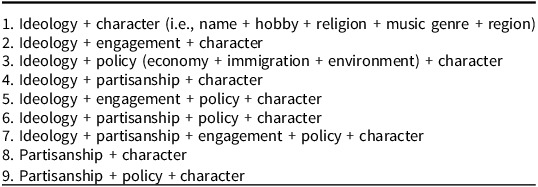

The nine versions of the vignette are presented in Table 2. The vignettes always include the name and other background characteristics of the hypothetical individual but vary in the amount of information they contain about their political characteristics. The simplest version just mentions the ideological affiliation of the individual. Versions 2 to 4 also include one other characteristic (interest, policy stances, or partisanship), while versions 5 and 6 include two further characteristics, and version 7 contains all possible information. Finally, versions 8 and 9 leave out ideology and focus on partisanship instead.

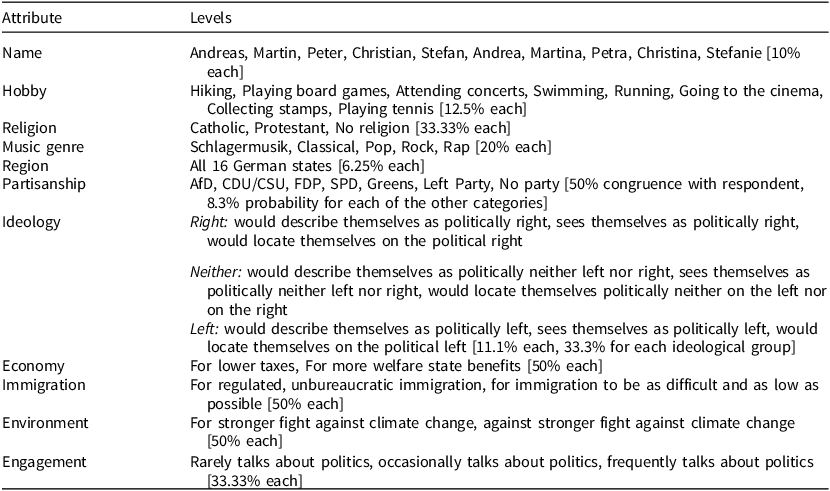

Table 1. Attributes in the full profile

Table 2. Nine variants of information contained in vignettes

Before the experiment, we measured the ideological identification, partisanship, and policy stances of respondents in order to match them to the attributes in the vignette; the order of these questions was randomized.

We measure ideological identification building on standard questions on party identification. We omit a ‘moderate’ category to make it easier to assign people to groups but add ‘leaners’ based on a follow-up question. Specifically, we ask, ‘In politics, people often talk about “left” and “right”. Whom do you feel close to politically, the Left or the Right?’; those who answer ‘Neither’ were then asked, ‘And are you nevertheless closer to the Left or to the Right?’. Only respondents who reiterated that they identified as neither left nor right were coded as neutral. In our main analysis, we code all profiles as either matching or not.

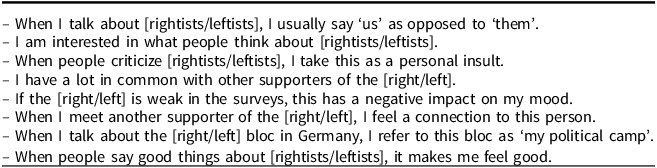

We also measure the strength of ideological identification. Building on Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015), Oshri et al. (Reference Oshri, Yair and Huddy2022) formulated an innovative attachment to an ideological group (AIG) survey scale and applied this to Israel, a context with volatile parties representing long-standing political divisions. We implement this measure here. For those who indicated an ideological identity, including leaners, we followed up with eight agree-disagree statements. We rescale this variable to range from 0 to 1; see Table 3 for the detailed statements. These are used to assess H1b, i.e., whether those with stronger ideological identities evaluate individuals more based on their ideological group. We also ask a more traditional strength of identification question, ranging from ‘very weak’ (0) to ‘very strong’ (3), as an alternative measure, and find that our results remain robust (see Online Appendix B, Table B.3, model 7).

Table 3. Attachment to an ideological group measure

Our further characteristics were measured as follows. For partisanship, we use the standard question asked in the German Longitudinal Election Study: ‘Do you in general feel close to a particular party?’ Again, we code only profiles with exactly the same partisanship as a matching and every other profile as a mismatch. Respondents with no partisan identification were matched with profiles that explicitly state ‘no party’. We also asked eight agree-disagree statements about the strength of partisanship, following Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018). This variable is also rescaled to range from 0 to 1. For partisanship, we also ask the more traditional strength of identification question, ranging from ‘very weak’ to ‘very strong’. The results, available in Online Appendix B (Table B.4, model 10), remain robust.

To measure support for the policy issues we included in the vignettes, we asked direct questions on each policy area, using six-point scales (thus avoiding a neutral midpoint option) so that we can assign respondents to one side of each issue (see Online Appendix A for the full text of these questions). Respondents were required to answer all questions, and there was no ‘don’t know’ option; while this might increase measurement error if respondents are forced to declare a preference where they have none, this also reduces incentives to engage in low-effort responding and survey satisficing.

To measure political engagement, we asked about agreement with four statements, adapted from Krupnikov and Ryan (Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022); from the seven items originally proposed, we selected the four that we thought best apply to the German context. Again, respondents were required to answer all four questions, and there was no ‘don’t know’ option. The four items were ‘It is important to share your political opinions with others’, ‘It is important to share political news stories with other people’, ‘When people tell me that they do not follow politics, it upsets me’, and ‘It is important to correct people’s misperceptions about politics even if they do not want to hear these corrections’. We also asked about political interest directly, asking, ‘How interested are you in general in politics?’ The answer scale was ‘very strongly’, ‘strongly’, ‘moderately’, ‘less strongly’, and ‘not at all’. Responses are rescaled to create a 0–1 political engagement scale.

We test our hypotheses by regressing our outcome variable, interpersonal affect, on dummies indicating whether the ideological attribute of the profile matches that of the respondent. In line with standard conjoint analysis, we interpret this as the average marginal component effect of shared ideology. Furthermore, to test H1b, we interact shared ideology with the Attachment to Ideological Group measure. To test H2a to H2c, we interact with indicators for each of the nine variations of the vignettes.Footnote 4 To test H3, we add interactions between the relevant match variables for vignettes where both attributes are present. Finally, for H4 we perform the same analysis, focusing on a partisan match. Because each respondent evaluated 12 profiles, we use OLS regression with clustered standard errors.

Results

Before we turn to the results of our experimental analysis, we show descriptive results from our survey concerning the distribution of ideological attachment and the other political characteristics it correlates with.

Descriptive patterns

Many German citizens declare an ideological identity. In our survey, 43% of respondents immediately chose to identify with either Left or Right, with another 13% who are ‘leaners’. This is a lower percentage than those who identify with a party: 78% immediately select a party when asked if they feel close to one.

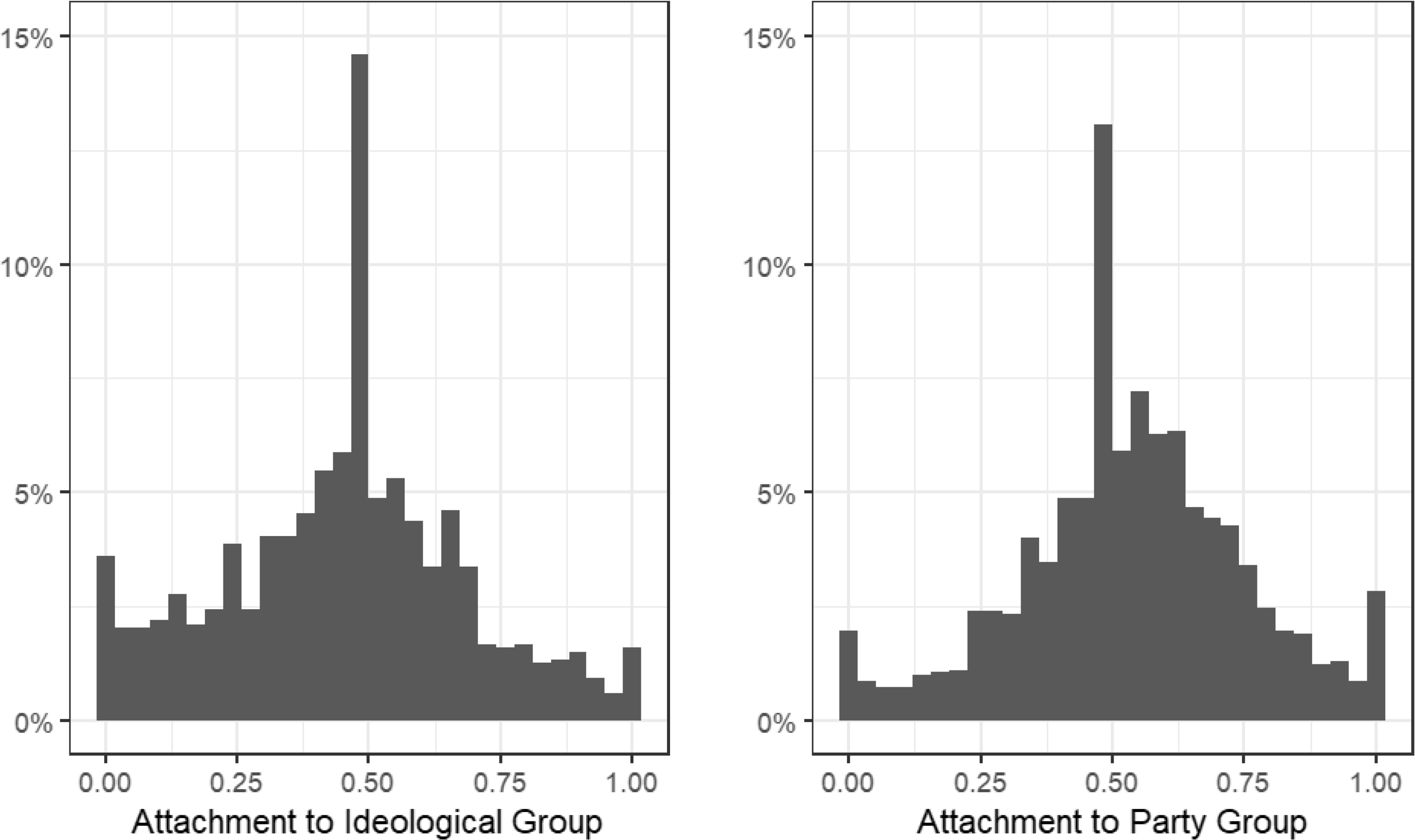

However, among those who do identify with an ideology or a party, the strength of identification is similar. The mean score on the eight-item scale of attachment to ideology is 0.45, compared to 0.54 for partisanship. As Figure 1 shows, there is a moderate level of attachment to ideological groups, while attachment to a party is generally greater. Results for the more traditional measures are similar.

Figure 1. Distribution of attachment to ideological and party groups.

Note: Data: Survey of German citizens. Histogram only for those stating the relevant identity. Survey questions can be found in Appendix A.

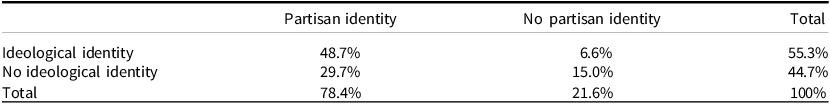

Our survey also shows that our political characteristics are indeed related. Table 4 shows overall proportions of respondents in each group. It is quite common to have both a partisan and an ideological identity, or neither: this applies to over 60% of the sample. Around 30% only have a partisan identity, and around 7% only have an ideological identity. Those who identify with an ideological group are 26.1% more likely to feel close to a party. Among those in our sample who reported both a partisan and an ideological identification, most of the left-identifiers aligned themselves with a left-wing party and vice versa (for details, see Online Appendix F, Table F.1). However, there is a lot of variation: the FDP identifiers are the most divided, with 44% identifying with the left. In contrast, only 4% of Linke identifiers report a right-wing identity. For the two biggest parties, Christlich Demokratische Union/Christlich-Soziale Union (CDU/CSU) and Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), less than 80% are coherent. Finally, as one would expect, ideological identities relate to political engagement: those who have an ideological identity also have higher political engagement (mean of 0.65 versus 0.55 on our 0-1 scale).

Overall, these results indicate that partisan identities are slightly more important to German voters than ideological identities. Moreover, partisan and ideological identities tend to co-vary but are not coterminous: while it often happens that voters have both identities, many voters only have one identity or the other.

Affective evaluations: experimental results

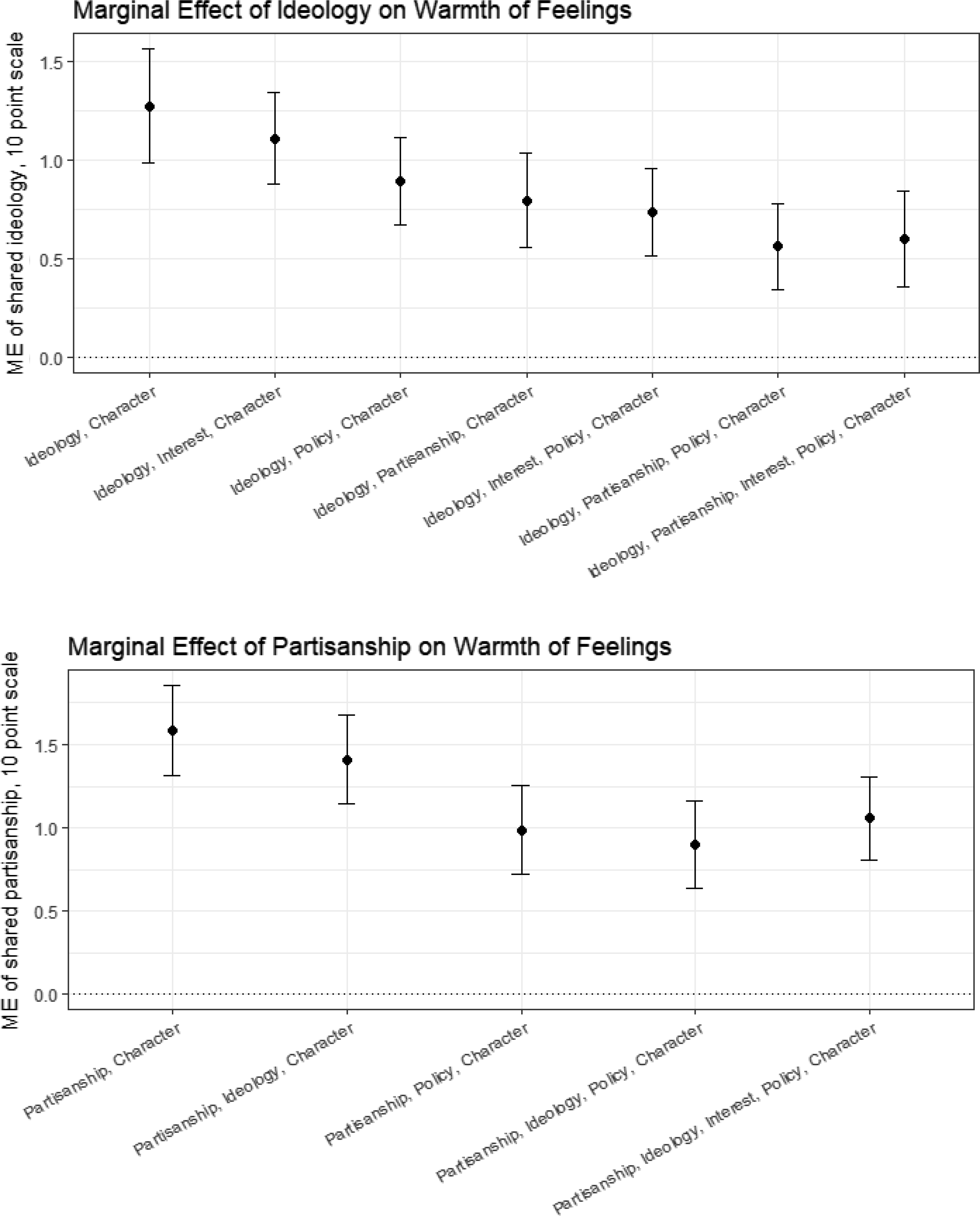

What is the effect of sharing ideological attachment on how warmly respondents feel towards an individual? Recall that our outcome variable here is a 0–10 scale of interpersonal affect, with higher values implying warmer feelings. The two panels in Figure 2 present the ACME for a vignette with a shared ideological group (top panel) and shared partisanship (bottom panel). The reference category for each estimate is a vignette where the ideological group or the partisanship of the individual differs from that of the respondent.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of ideological matches and partisan matches in different treatments.

Note: Estimates are average marginal component effects for shared ideological group and shared partisanship. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The experimental groups correspond to those listed in Table 2. N = 20,112. Full regression tables can be found in Appendix B, Table B.1 and Table B.2.

The leftmost estimate in the top panel of Figure 2 shows the effect of shared ideological attachment compared to not sharing an ideological group for the set of conjoint vignettes where ideological attachment is shown on its own, without the three other relevant political attributes. The estimate shows that affect is 1.27 points higher on the 0–10 scale for vignettes with shared ideological attachment increases compared to vignettes that do not share the respondent’s ideological group. This effect is sizeable, given that the standard deviation of the outcome variable is 2.56. Moreover, the effect is broadly similar to that of shared partisanship, which is 1.59 points (see bottom panel). This confirms H1a: shared ideological attachment positively impacts feelings towards an individual. Hence, the simple labels ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ contain important information that citizens rely on to shape their interpersonal affect.

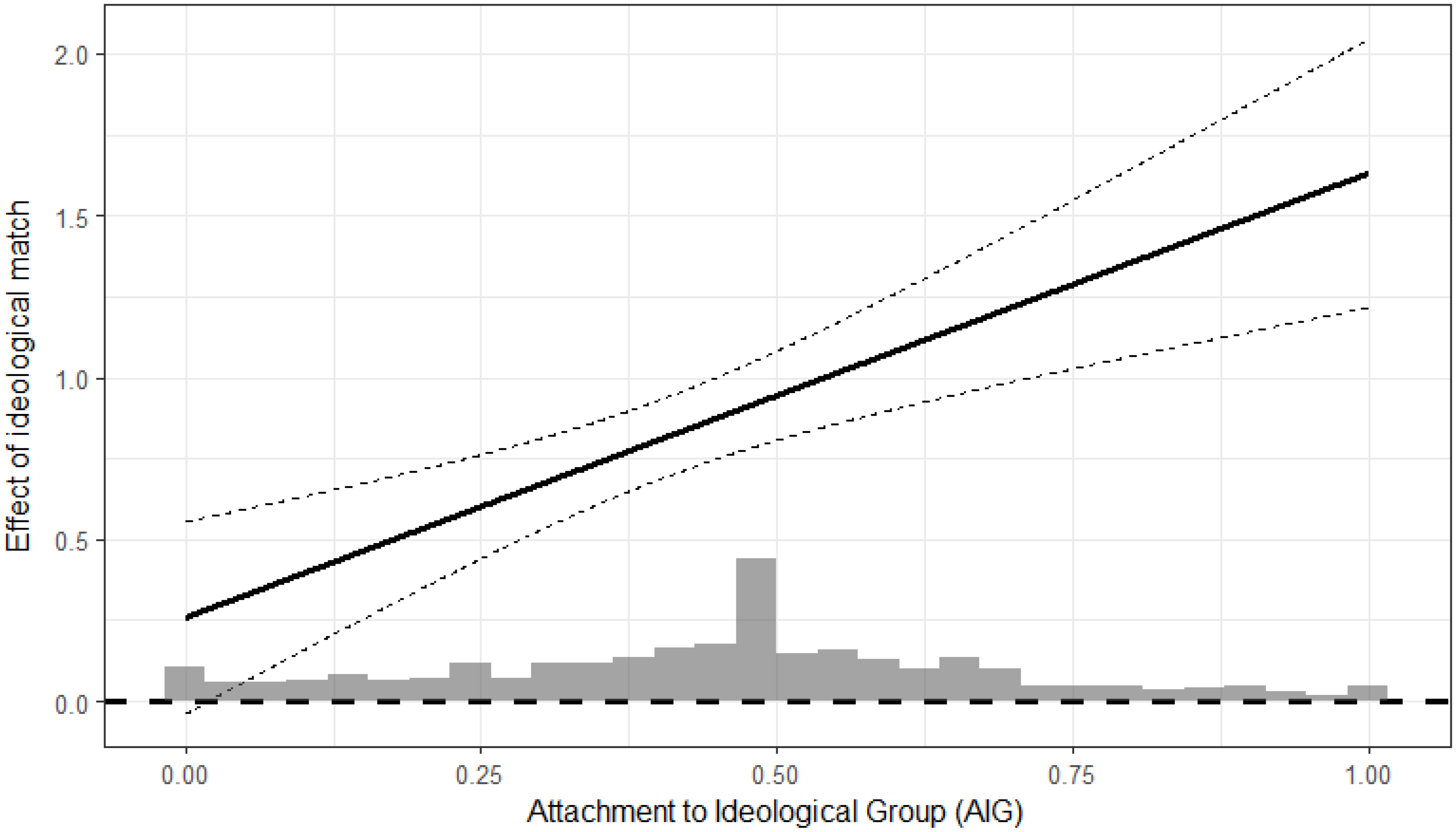

Figure 3 shows that, as expected, those who identify more strongly with an ideological group also tend to use this information more strongly to determine their affect for the hypothetical individual. For those with a strong ideological attachment, a shared ideological identity increases affect by over 1.5 points, compared to just 0.25 points for those with very weak ideological attachment. This interaction effect is strong, positive, and statistically significant, and it is robust to the inclusion of our Attachment to Partisan Group (APG) measure. We also find the same results when interacting with a more traditional measure of strength of ideological attachment (see Online Appendix B, Table B.3). This provides strong support for H1b.

A key motivation for our study is that policies, ideologies, and partisanship are likely correlated in the minds of voters. This implies that when reading an ideological label, our respondents may infer the two other attributes. As outlined in H2a to H2c, if the other political attributes are also present, the impact of sharing ideological attachment should decline. This finding is also shown in the top panel of Figure 2. The effect of sharing ideological attachment declines least if political engagement is mentioned explicitly – this reduction is not statistically significant, and thus we do not find support for H2c. For all other versions of the vignette, there is a significant decrease in the effect of shared ideological attachment. The effect decreases in the presence of both a partisan cue and a policy cue, confirming H2a and H2b. The effect declines most if all other characteristics except engagement are provided.

However, it is important to underline that sharing ideological attachment still has a positive impact on affective evaluations even when respondents are explicitly informed about the individual’s partisanship, policy stances, and political engagement. This effect is statistically different from 0 and also non-negligible. This provides a strong indication that ideological labels contain a lot of information that respondents see as relevant and useful.

Overall, the pattern for partisanship is similar to that for ideological attachment (see bottom panel of Figure 2). Recall that, when included on its own, the effect of partisanship on warmth of feelings is slightly larger (1.59) than the equivalent effect of ideological identity (1.27). As with ideological identities, the effect of sharing partisanship is clearly strongest when present on its own (leftmost estimate), diminishing once other attributes are present. The decline when ideology is also included is in line with Hypothesis 4; however, this decline is not statistically significant. Moreover, the effect of shared partisanship also increases along with respondent strength of partisanship, similar to ideological attachment (see Online Appendix B, Table B.4).

In sum, ideological and partisan identity have similar effects, and these effects respond similarly to the inclusion of additional information. Hence, ideological attachment works in similar ways to partisanship in determining how respondents evaluate individuals.

Profiles with conflicting attributes

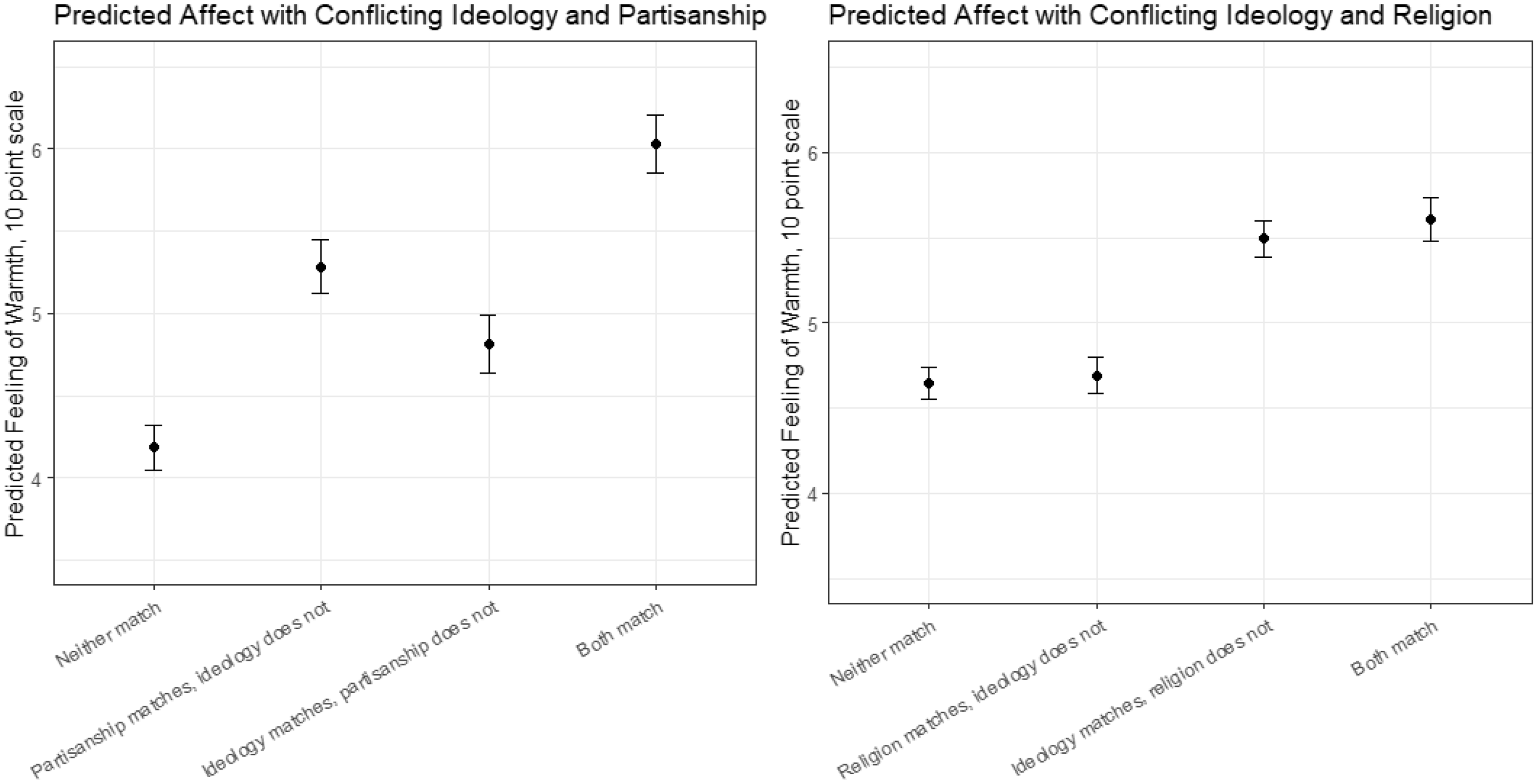

Next, we consider H3, so how respondents react when ideological attachment and partisanship conflict with the explicit policy stances linked to individuals. We hypothesized above that respondents would privilege shared policy stances over shared ideology, and this is indeed the case. The top panel of Figure 4 shows the predicted interpersonal affect for four different potential scenarios: when the respondent agrees with none, one, two, or all three of the policy positions in the profile. If all policy positions match (fourth predicted value in the figure), the respondents feel much warmer about the profile than if only the ideology matches (fifth predicted value). However, adding an ideology match to an already ‘complete’ policy match still has a strong positive effect on the interpersonal affect (eighth predicted value, ‘all match’).

There are different ways of interpreting this. On one hand, a profile that matches on ideology but not on the three salient policies (fifth predicted value) might be interpreted as an individual who is using the ideological labels wrong, who is not true to their ideology, or who is simply unrealistic. Relatedly, Dias and Lelkes (Reference Dias and Lelkes2022) have suggested that a pro-choice Democrat might dislike a pro-life Democrat not because of the policy stance itself, but because the conflict reveals that the co-partisan is disloyal. On the other hand, the ideological label captures a myriad of policy issues. When the effect of one single shared policy position (second predicted value in the figure) is approximately equal to the effect of shared ideological attachment (fifth predicted value in the figure), we take this as evidence that voters do strongly prioritize the policy match in line with H3.

Similar patterns, in fact, also apply to partisanship, which also takes a back seat once policy preferences are known (see bottom panel of Figure 4). Agreeing on all three policies but not partisanship (fourth predicted value) results in a significantly more positive evaluation of the profile compared to the opposite scenario, where the respondent agrees with the hypothetical individual’s partisanship but none of the policy positions (fifth predicted value).

Finally, we also examine patterns when partisanship and ideological attachment conflict. In this scenario, we find that shared partisanship has a stronger effect (0.98) than shared ideology (0.45). In the left panel of Figure 5, we plot the predicted level of affect for different combinations of matching partisanship and ideology, averaging across all other attributes. Here, one can compare the estimated effect of a change in ideology for the partisan outgroup (first and third effect) versus the partisan ingroup (second and fourth effect). There is no significant interaction effect between the two, meaning that the effect of a shared ideological attachment is not conditional on shared partisanship.Footnote 5 The figure clearly shows that the predicted affect towards a profile with a shared partisanship but not ideology is significantly higher than the opposite scenario. In short, we conclude that voters prioritize partisanship over ideological attachment.

To put the size of these effects into perspective, we also tested the effects of shared social characteristics (gender, religion, region, music taste, and hobbies) on interpersonal affect. We find that there is no significant effect of shared gender and region, but a significant positive effect of sharing a religion. However, the right-hand panel of Figure 5 shows that, compared to the political identities, religion plays a negligible role (see Online Appendix B, Table B.6 for full results). The effect of sharing a religion might be underestimated due to the priming of politics in the pre-treatment questions and in the experiment itself; yet, the differences in effects are quite remarkable. Preferences for the profiles’ favorite music and hobby, coded as a continuous 11-point scale, also have a significant positive effect.

Robustness checks: excluding ‘unrealistic’ profiles

In the experiment, we decided against restricting ex ante potentially unrealistic combinations of policy stances, ideological affiliation, and partisanship, as this provides us with some leverage to examine the effects of one attribute in the presence of others. Nevertheless, there might be concerns that some combinations are simply too ‘unrealistic’ and will prevent the respondents from engaging earnestly with the vignettes. To counter this point, we test whether our results hold up when we only analyze a more consistent subset of profiles. In a robustness check, we exclude profiles of vignette individuals that (a) identify as left-wing but support a right-wing party (CDU, CSU, FDP, or AfD) or identify as right-wing but support a left-wing party (SPD, Greens, or Linke) (28%); (b) identify as left-wing but have three right-wing policy stances or vice versa (11%); and (c) support a left-wing party but have three right-wing policy stances or vice versa (9%). Profiles that were ideologically neutral can only be inconsistent if there is a party-policy conflict; similarly, profiles of people who did not support a party can only be inconsistent if there is a policy-ideology conflict. If we remove the more unrealistic profiles, the overall pattern of results remains very similar to the initial analysis (see Online Appendix C, Figure C.1). We also ran a robustness check taking into account that it might be considered ‘unrealistic’ that someone would self-identify as an ideologue or have a strong policy position if they do not engage with politics and rarely talk about it. We found that removing all uninterested profiles with explicit political identities did not change our results substantially (see Online Appendix C, Table C.3).

Finally, we also explored three alternative model specifications. First, we examined whether categorizing ideological attachment based on left-right self-placement affects results; second, we also checked whether restricting the sample to ideological moderates has an impact on our findings. In both cases, we also found a strong positive effect of shared ideological identity on interpersonal affect, with this effect only decreasing significantly in the presence of all the other cues (see Online Appendix C, Table C.1). Lastly, the estimates remain similar if we exclude all respondents without an attachment, i.e., those who are ideologically neutral and report no partisan identification, from the models, though the standard errors increase due to the change in sample size (see Online Appendix C, Table C.4).Footnote 6

Ingroup favoritism or outgroup derogation?

In addition to our pre-registered analyses, we can also examine whether our results are the product of ‘in-group favoritism and out-group derogation’ (Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024, 69). Moreover, we can check whether ideological respondents respond to neutral profiles as negatively as they do to a profile with the opposing ideology. To examine this, we run a set of analyses with three levels of both ideological and partisan matches, rather than the dichotomous indicator we have used thus far (see Appendix G). Specifically, we add a distinction between explicitly neutral profiles and out-group profiles, where the hypothetical individual belongs to the opposing ideological side or identifies with another party. Note that the neutral category is not the absence of an ideological or partisan cue but rather a baseline or control group.

The results reveal that individuals’ two political identities operate in different ways. The effects of partisanship appear to be largely symmetrical (see Online Appendix G, Figure G.1), with the outgroup having a moderate negative effect and the ingroup having a moderate positive effect on interpersonal affect. In contrast, the effects of ideology are largely asymmetrical. There is no statistically significant difference between shared ideology and being ideologically neutral, except in the full version of the vignette. Thus, there is only little evidence that voters feel more warmly towards others who share the same ideological identity as themselves compared to non-ideological neutral citizens. Instead, there is a strong negative effect of belonging to the opposing ideology. This effect decreases significantly as more information is added to the vignette treatments but nevertheless remains strong and significant throughout.

Conclusion

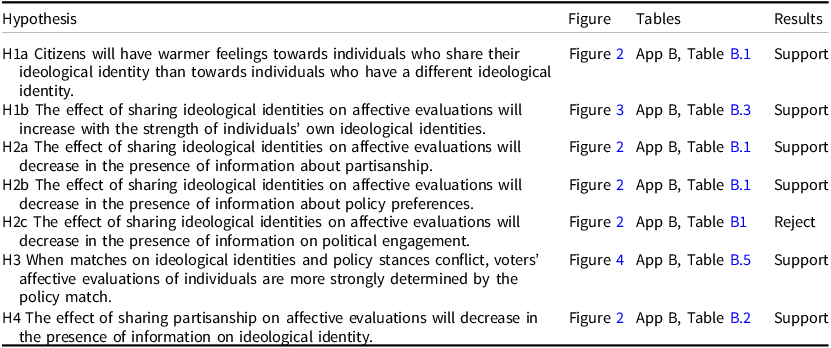

Political characteristics such as people’s policy views or partisan sympathies influence what citizens think of each other and how they treat each other (Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Helbling and Jungkunz Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020). In this paper, we show that ideological identities also matter for how voters see themselves and how they evaluate others. Our findings are summarized in Table 5.

Table 4. Cross-table of respondents with partisan and ideological identities

Data: Survey of German citizens, 2023: cell percentages show. N = 2,152. Survey questions can be found in Appendix A.

Table 5. Summary of results

In Germany, substantial proportions of survey respondents state an ideological identity, and for those who have an ideological identity, this is similar in strength to partisan identities. In our survey experiment, respondents respond positively to shared ideological attachment, taking shared ideological identities into account almost as much as partisanship, and those with strong ideological identities paid particular attention to this information. We also show that ideological identities still matter, if less so, when information on partisanship, policy stances, and political engagement is included. We see this as indicative evidence that ideological labels indeed mean more than the policy stances these imply, so that, like partisan labels, the terms ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ hold meanings that go beyond policy content. Moreover, our results hold if we restrict the analysis to more plausible combinations of characteristics. Our results add to the ongoing debate, sparked in part by Orr and Huber (Reference Orr and Huber2020), on the source of affective evaluations and speak to the broader literature on political social identities (e.g., Mason Reference Mason2018; West and Iyengar Reference West and Iyengar2022; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024).

At the same time, ideological identities matter a little less than other characteristics. Three pieces of evidence are relevant here. First, somewhat fewer people in Germany have ideological identities than partisanship. Second, the effect of ideological identities on affective evaluations is slightly smaller than for partisanship. Finally, when ideological identities conflict with partisanship or policy stances, respondents privilege congruence on the latter characteristics. In addition, we show that, when it comes to ideological identities, out-group derogation seems to matter more than in-group favoritism (Hahm et al. Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024); in contrast, such asymmetric effects are not found for partisan identities.

Despite these important caveats, our overall result clearly underlines that ideological identities are highly relevant for how citizens evaluate each other. When examining politically relevant attributes of citizens, we need to go beyond partisanship and policy and consider a broader range of identities and group memberships. On the one hand, this applies to citizens’ own political identities. While in the US two-party system many potential political identities are subsumed or integrated into partisan divides, in other contexts multiple, overlapping political identities may coexist and hold relevance for individuals. On the other hand, the need to go beyond partisan labels also applies to our understanding of how individuals evaluate others. The affect citizens hold towards others is clearly shaped by political attributes, but these political attributes can encompass more identity-based labels than solely partisanship.

Further research should examine variation in how ideological identities matter. First, ideological identities may matter more in some contexts than in others. We chose a case, Germany, where both partisan and ideological identities were likely to be relevant, and indeed a large percentage state such identities in our survey. In some countries, ideological identities may matter a lot more than partisan identities, especially when parties are ephemeral, but in other countries, partisan identities may play a much larger role than ideological identities. Second, other types of issue- and opinion-based groups may matter more in other contexts, for instance, based on divides such as Brexit or regional nationalism. In addition, future work should consider adding a broader range of policy issues as a part of experimental designs. We included three key issues, but this may only partly account for the policy stances that ideological labels imply. Finally, negative ideological identification could be a parallel to negative partisanship (Bankert Reference Bankert2021; Mayer and Russo Reference Mayer and Russo2024). These comparative findings – across countries and types of ideological identity – will be an important step forward in understanding when and why political characteristics matter for affective evaluations.

Future research should also turn to examining the everyday importance of these characteristics. Our experiment presented respondents with fictitious individuals with clearly defined attributes. An interesting and important question is how citizens tend to define themselves politically. How many reach for ideological, partisan, and policy-based labels when outlining their relationship to politics? How often do citizens spontaneously use ideological or partisan labels to describe themselves? And to what extent and how accurately do we know the political identities and policy views of people we meet? These questions are essential for our understanding of how political characteristics shape our affective evaluations. Our study shows that ideological identities can and do matter when they are known. How these findings transfer to real-world settings is a fascinating task for future work.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S147567652510056X.

Data availability statement

All replication materials, as well as a supplementary online appendix, are available through the EJPR website.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this manuscript have been presented at Royal Holloway, University of London, Koc University, and at the Department of Government internal seminar. The authors would like to thank all participants for their valuable feedback and suggestions. We would also like to thank Maximilian Martin for support in preparing and piloting the survey.

Funding statement

This research is funded as part of the ERC Consolidator Grant PARTISAN.

Competing interests

This paper was submitted prior to co-author Markus Wagner’s appointment as an Editor on the EJPR team. The editorial and review process followed the journal’s standard independent peer review procedures to ensure fairness and transparency.