Introduction

Recent high‐profile scandals around COVID‐19 procurement processes are an important reminder that both grand corruption and everyday graft continue to undermine even the most important government activities in a remarkably broad set of countries. According to Transparency International, there are already documented cases of corruption and malfeasance related to COVID funds in 19 countries across five continents, with a total value more than USD $1 billion (2020). The breadth and depth of this ‘graft pandemic’ has naturally inspired calls for a renewed anti‐corruption drive, in both ‘developing’ countries and their ‘developed’ counterparts (IMF, 2020). These campaigns will almost certainly include an awareness raising element, because this has been central to global efforts to counter corruption over the last 30 years. The United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) (2004), for example, advises that campaigns should seek to raise awareness of the problem posed by corruption and its negative consequences. Partly as a result, supranational bodies and non‐governmental organizations – often supported by international donors – deploy anti‐corruption messaging, through a variety of mechanisms of public communication, including billboards, newspaper advertisements, signs in public buildings and radio messages.

The ‘theory of change’ underpinning this approach is intuitively appealing. There is a growing recognition that the real barriers to dealing with corruption are not technical or administrative, but are rather rooted in politics and the distribution of power (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Andreoni and Roy2019; McLoughlin et al., Reference McLoughlin, Ali, Xie, Cheeseman and Hudson2024). Political leaders who benefit from graft are unlikely to enact tougher anti‐corruption measures unless they are pressured to do so by citizens. In turn, ensuring that citizens understand the prevalence and cost of corruption, gives them the information they need to hold leaders accountable and to play other roles in the fight against graft, such as refusing to pay bribes or reporting instances of corruption. In some cases, as when international donors launch a multi‐million Euro anti‐corruption programme, this messaging is integrated into a wider range of activities and interventions in the expectation that it will boost public support for – and hence the implementation of – the reform process. Often, however, messaging is conducted in isolation, in part because it has become routine and near ubiquitous in developing country contexts (Cheeseman & Peiffer, Reference Cheeeseman and Peiffer2024), with anti‐corruption billboards, posters and signs present all year round, especially in government buildings and locations such as bus stations and airports.

The widespread use of such messaging is particularly significant because research has shown that anti‐corruption awareness raising messages can do more harm than good, triggering a sense that corruption is too widespread to be dealt with, and potentially encouraging individuals to ‘go with the corrupt flow’ rather than fight against it (e.g., Cheeseman & Peiffer, Reference Cheeseman and Peiffer2022; Corbacho et al., Reference Corbacho, Gingerich, Oliveros and Ruiz‐Vega2016). The potential for anti‐corruption messaging to backfire is particularly concerning because corruption scandals and public concern about graft have been cited as key ingredients in the rise of anti‐system and, more specifically, populist leaders around the world (Araújo & Prior, Reference Araújo and Prior2021; Liang, Reference Liang and Liang2016). To understand how fundamental this relationship is to the growth of populist movements, it is important to consider the core claims of populist leaders. Classic populists base their appeal on the idea that they are outsiders who embody the will of the people and offer a genuine alternative to the existing political establishment (Laclau, Reference Laclau and Panizza2005), which is depicted as being inherently flawed and anti‐popular. What distinguishes populism is thus ‘first and foremost a Manichean world view that assumes that society is characterised by a distinction between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite”’ (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2014, p.1).

On the basis of this worldview, the political establishment is inherently corrupt because it is divorced from – and so cannot be expected to serve the interests of – ordinary people. Corruption accusations are therefore not just something populist leaders occasionally manipulate to score a cheap point. Rather, they are fundamental to populist ideology and central to claims that populist leadership is required. Given the centrality of corruption to the construction of populist movements, it is therefore feasible that nationwide campaigns that raise awareness of the extent of corruption play directly into the hands of aspiring anti‐system leaders. By highlighting the problem, anti‐corruption awareness raising may unintentionally nudge people to be more sympathetic towards populist rhetoric.

This is potentially problematic, because while we should not seek to mask the failings of existing political systems, conventional anti‐corruption efforts may be inadvertently encouraging unwanted political trends. The rise to power of figures such as Jair Bolsonaro, former president of Brazil, Rodrigo Duterte, former president of the Philippines, and Donald Trump, former president of the United States (US), undermined democratic checks and balances while infringing on the rights of minority communities (Daly, Reference Daly2020; Pernia, Reference Pernia2019; Putzel, Reference Putzel2020). Populist governments have also – somewhat paradoxically – been argued to have contributed to a significant increase in the level of corruption (Mendilow, Reference Mendilow2021; Zhang, Reference Zhang2023), in part because the focus on an individual ‘man of action’ tends to undermine institutional checks and balances (Kostadinova, Reference Kostadinova2023; Resnick, Reference Resnick2019).

It is therefore critically important that anti‐corruption campaigns identify strategies to reduce graft in ways that do not open the door to anti‐system and populist leaders who have often been associated with even greater levels of corruption while in office. Yet while a large literature documents the relationship between corruption and the rise of populist beliefs and leaders, as set out below, there has been almost no attention to the way in which anti‐corruption campaigns might facilitate the rise of populist parties. In this paper we provide what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first attempt to systematically test the impact of the kinds of narratives used in anti‐corruption awareness raising campaigns on core populist beliefs and attitudes. We do this through an original nationally representative survey‐experiment of 2,002 people that was conducted in Albania in 2022. Albania represents an ideal case in which to conduct this study because it has seen minor breakthroughs by populist parties in the past decade (Bino, Reference Bino2017) and features the kind of political environment – a relatively new democracy with weak institutions and high levels of public concern around corruption – that is often argued to be vulnerable to populist takeover.

To reflect the latest developments in the literature we test three different anti‐corruption messages. First, we test two messages which are designed to raise awareness of the extent and impacts of corruption. As noted earlier, these messages are representative of themes that are typically seen in anti‐corruption awareness raising and UNCAC advises that awareness raising emphasise these themes (United Nations, 2004). Testing these types of messages also reflects a growing amount of work that finds that anti‐corruption messages that raise awareness of the extent and impacts of corruption can backfire. The first, corruption is widespread, describes corruption in Albania as being widely practiced and hampering access to public services. The second, corruption is transnational, focuses on the international nature of high‐level corruption, emphasising how much Albanian wealth and resources are lost to other countries through kleptocratic governance patterns. In contrast, the third message we test – public disapproves of corruption – focusses on the fact that overwhelming majorities of Albanians disapprove of corruption and believe that those who engage in it should be punished. This message was tested as insights from recent literature in social psychology suggests that the risk of messages ‘backfiring’ is much lower when they do not mention how widespread corruption is but instead focus on the strength of popular anti‐graft sentiment. All three messages were produced in consultation with policy makers who play a prominent role in the Albanian context to ensure that they reflected messaging that could be used in practice.

We assess the impact of these messages by dividing our sample into four groups: control, corruption is widespread, corruption is transnational and public disapproves of corruption. Each group (apart from the control group) was first shown a message, and then all groups were asked a series of questions about corruption and their political attitudes and beliefs. Using principal component factor analysis, we capture support for populist ideas and attitudes through the creation of a populist attitudes index, which is constructed based on responses to four questions that tap core aspects of populist ideology. More specifically, these questions ask to what extent individuals agree that: the country is divided between ordinary people and corrupt elites; that the will of the people should always be respected; that it is better to be represented by a fellow citizen than by a career politician; and, that leaders should not face checks and balances when trying to get things done. Using ordinary least squares regression analysis, we estimate the impact of exposure to each anti‐corruption message on an individual's position on the populist attitudes index. We also conduct ordered logistic regression analyses to estimate the impact of exposure to messaging on responses to each of the indicators of populist attitudes individually, as this facilitates an examination of the substantive effects of exposure across the four components.

As expected, we find that exposure to the corruption is widespread message is significantly associated with higher scores on the populist attitudes index and a greater degree of agreement with three of the four indicators of populist attitudes. Meanwhile, exposure to the corruption is transnational message is significantly associated with higher scores on the populist attitudes index and increased agreement with two of the four components. This confirms that messages which emphasise the scale and harms of corruption can have the unintended effect of encouraging their audience to hold anti‐system and populist beliefs. Significantly, recent research has also demonstrated that these kinds of message often also fail to encourage anti‐corruption sentiment (Beesley & Hawkins, Reference Beesley and Hawkins2022). Taken together, this means that there is a significant risk that the kinds of messages used in anti‐corruption campaigns open the door to populist movements without delivering any positive impact in terms of encouraging citizens to support anti‐corruption efforts. We also find that the third treatment, public disapproval of corruption, does not have a significant impact on the populist attitudes index or any of the components we test for. In line with recent literature from social psychologists, this suggests that such messaging may be less likely to cause the unwanted side‐effect of encouraging agreement with populist ideas – although it is important to note that this does not mean that they necessarily encourage citizens to participate in anti‐graft campaigns.

We make this case by first reviewing the literature on the relationship between corruption and populism and anti‐corruption campaigns, before setting out our research design, explaining our treatments and discussing our results. We argue that our analysis serves as an important warning of the potential risks of deploying typical anti‐corruption messages in the current global political environment. It also, however, suggests that it may be possible to avoid these negative consequences by identifying specific types of messaging that are less likely to backfire and have unwanted side effects.

What do know about corruption, populism and anti‐corruption campaigns?

The rise of populist leaders in countries such as Brazil, Hungary and the US has led to a renewed focus on the trends that facilitate the emergence of anti‐system movements. In addition to factors such as economic disruption and falling class mobility (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2021), this literature has shown how ‘corruption becomes an inherent part of populist rhetoric and policies: populist leaders stress the message that the elite works against the interest of the people and denounce corruption in government in order to stylize themselves as outsiders and the only true representatives of the people's interest’ (Kossow, Reference Kossow2019, p.1). In Eastern Europe, for example, ‘populist forces only emerged after the fall of the Berlin Wall’ by positioning themselves as ‘defenders of the revolution’ in a ‘context of rampant corruption’ (Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2019, p.4). Similarly, Liang argues that corruption and the perception that the existing political elite are exploiting power for their own gain was one of the concerns that opportunist political entrepreneurs manipulated in Europe to create a ‘new populist moment’ (Liang, Reference Liang and Liang2016, p.1). Meanwhile, Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris (Reference Inglehart and Norris2016, p.5) have argued that Donald Trump's ‘populism is rooted in claims that he is an outsider to D.C. politics, a self‐made billionaire leading an insurgency movement on behalf of ordinary Americans disgusted with the corrupt establishment, incompetent politicians, dishonest Wall Street speculators’ (emphasis added).

This relationship has not only been identified in Europe and the US. Indeed, there is now a remarkably wide set of cases in which the rise of populist leaders has been associated with corruption scandals, including Brazil (Araújo & Prior, Reference Araújo and Prior2021); Mexico (Bruhn, Reference Bruhn, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012), Romania (Kiss & Székely, Reference Kiss and Székely2022) and Turkey (Onbaşı, Reference Onbaşı2020). Although corruption is only one manifestation of a wider phenomenon in which populist leaders seek to exploit public concern about how those in power violate the rule of law (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2010, pp.132, 160; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Aguilar, Castanho Silva, Jenne, Kocijan and Rovira Kaltwasser2019), it is widely seen as the most important component of this broader agenda. This is no accident but is rather related to the fact that corruption is an issue that is uniquely suited to populist logics. As Ina Kubbe and Miranda Loli have put it (Reference Kubbe, Loli, Mungiu‐Pippidi and Heywood2020, p.118), ‘corruption can be understood as an important aspect of the moral underpinnings of populist ideology’. For Jonathan Mendilow (Reference Mendilow2021, p.1) ‘the protest against elite corruption’ sits ‘at the core of the populist message’. In other words, corruption is not simply an issue the populist entrepreneurs seek to exploit on an ad hoc basis, but a central pillar of the belief system that they propagate.

In a classic populist formulation, it is not just that the existing political class may be corrupt at certain points in time. Rather, the political class is always corrupt in the sense that career politicians are inherently opposed to the interests and needs of the ordinary person, who they cannot hope to understand, and the product of whose labours they exploit for their own benefit. This fundamental claim is essential to the broader populist project: only by framing career politicians as being fundamentally unable to rule in the interests of ordinary citizens can populist leaders make the case that the political establishment must be overthrown in favour of someone who embodies the will of the people.

Evidence of endemic corruption is important precisely because it supports these claims. In the context of election campaigns in Central and Eastern Europe, Sarah Engler (Reference Engler2020, p.643) finds that ‘populists along the ideological spectrum use anti‐corruption claims to highlight the dishonesty of the political elite’. In Italy, meanwhile, ‘local corruption exposure helps the populist parties in national elections and hurts the incumbents as the scandals are revealed’ (Foresta, Reference Foresta2020, p.289). In Albania, the aim of the populist party's Red and Black Alliance was to ‘mobilise citizens against corruption and antidemocratic deeds of the government’ (Bino, Reference Bino2017, p.7). In Slovakia, ‘the success of Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO) led by Igor Matovič in the 2020 parliamentary elections … owed much to the crafting of an anti‐corruption appeal combined with an effective campaign’ (Haughton et al, Reference Haughton, Rybář and Deegan‐Krause2022, p.728).Footnote 1

This raises an important question about when concerns about corruption come to the fore and how they are reported. As Engler points out, it is not only populist parties that seek to play on corruption accusations. Instead, a broader range of parties ‘embed the fight against corruption’ in their campaigns (Reference Engler2020, p.643). Moreover, it is not only political parties that speak to corruption issues. The fight against corruption has been prominent on the global policy agenda since the mid‐1990s, attracting sustained support from international governmental organisations, donors, civil society organisations and national governments (Sampson, Reference Sampson2010, Reference Sampson2015, Reference Sampson and Arvidsson2019). As a result, in many countries fighting corruption has been a politically salient topic for at least 2 decades. Along with inspiring an extensive menu of anti‐corruption policy reforms, campaigners have also advocated for raising the awareness of the public to the dangers of corruption (e.g., United Nations, 2004). While the relationship between perceptions of corruption and the emergence of populist leaders has been well documented, far less has been said about how this wider set of anti‐corruption organizations and initiatives may impact on public opinion. We therefore know little about whether anti‐corruption campaigners, through well‐meaning and sincere efforts to tackle graft, open the door to populist attitudes and leaders by increasing public concern regarding the prevalence of corruption within the political establishment.

What do we know about the impact of anti‐corruption campaigns?

The intimate relationship between corruption and populism is particularly concerning in light of a growing body of work that reveals how raising awareness about corruption can have problematic consequences. Thus far, research on anti‐corruption awareness raising has tended to adopt an experimental approach. Estimates of the impact of exposure to messaging are established by comparing how randomly assigned participants who are exposed to a message (treatment group) respond – to a survey, behave in a simulated ‘bribery game,’ or make a choice to report corruption – as compared to the behaviour or responses of participants who receive no message (control group).

The overwhelming trend among these studies is that anti‐corruption messaging often does not work, and in some cases may even ‘backfire’. For example, a film featuring actors reporting corruption in Nigeria was found to have had no impact on willingness to report graft, but did encourage a sense that corruption, and anger about corruption, was widespread (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Littman and Paluck2019). In a previous study conducted in in Lagos, Nigeria, the authors found that exposure to four different messages made individuals more likely to pay a bribe in a ‘bribery game’ that involved real money (Cheeseman & Peiffer, Reference Cheeseman and Peiffer2021). These messages respectively emphasised that corruption is widely practiced, corruption is immoral, the government's successful anti‐corruption efforts and that corruption represents a theft of tax money. In a similar vein, exposure to a message about the prevalence of petty corruption in Peru reduced institutional trust and had no impact on willingness to donate money to an anti‐corruption organisation (Beesley & Hawkins, Reference Beesley and Hawkins2022).

One notable exception is Matthias Agerberg's (Reference Agerberg2021) study in Mexico, where exposure to a message about citizens being critical of corruption had the ‘intended’ effect – it reduced acceptance that corruption is a basic part of Mexican culture and lowered the likelihood of self‐reported willingness to pay a bribe (Agerberg, Reference Agerberg2021). It is also worth mentioning that Nils Köbis et al.’s (Reference Köbis, Troost, Brandt and Soraperra2019) study in South Africa had mixed results. This research found that posters put up in public places reporting that bribery had decreased reduced the odds of participants who took on the role of a public official in a subsequent game requesting a bribe. The same exposure had no impact on the choice of participants who took on the role of a citizen to bribe, however. As most participants were citizens rather than public officials in real life, these findings offer limited support for the notion that such messages can be relied on to work as intended. The overall findings from this growing literature are therefore concerning, casting doubt on the efficacy of anti‐corruption awareness raising, especially given that most of the messages which have backfired echo themes that are prominent in real‐world anti‐corruption awareness raising.

Given the risk of unintended and unwanted side‐effects, the question we engage with here is whether such messaging may also have a wider set of negative externalities. To the best of our knowledge, only one study so far has looked at another potential unintended impact of anti‐corruption messaging. The aforementioned Lagos research also investigated whether exposure to anti‐corruption messages impacted on willingness to pay tax (Cheeseman & Peiffer, Reference Cheeseman and Peiffer2022), and found that exposure to three of the four tested messages significantly reduced tax morale, with potential implications for government revenue streams. Our paper contributes to this literature by examining whether anti‐corruption messaging encourages agreement with populist ideas, a potential unintended impact of awareness raising campaigns with important implications for contemporary politics.

Why anti‐corruption messages backfire and how that may relate to populism

Anti‐corruption messaging is thought to be most at risk of backfiring when it explicitly emphasises a ‘descriptive norm’. Descriptive norms are based on beliefs about how others behave (Cialdini et al., Reference Cialdini, Reno and Kallgren1990; Legros & Cislaghi, Reference Legros and Cislaghi2020). A message that describes how much corruption there is in a given country and emphasises its negative consequences – which is what the UNCAC advises its signatory states to do (United Nations, 2004 – would invariably signal that many in society engage in corruption. In emphasising the extent of the problem, such messaging may trigger or embolden a sense of ‘corruption fatigue’ – the belief that corruption is too pervasive to ever be eradicated (Baez‐Camargo & Schönberg, Reference Baez‐Camargo and Schönberg2023; Bauhr & Grimes, Reference Bauhr and Grimes2014). Indeed, using complementary logic, previous research has found a positive association between government transparency in highly corrupt countries with higher rates of resignation to the corrupt system amongst citizens (Bauhr & Grimes, Reference Bauhr and Grimes2014), suggesting that evidence of far‐reaching corruption encourages individuals to believe that graft cannot be defeated (Hoffmann & Patel, Reference Hoffmann and Patel2017; Smith, Reference Smith2008). Importantly, almost all the messages tested in the literature for which exposure is associated with an unwanted impact on corruption attitudes, behaviour, or tax morale emphasise a ‘negative’ descriptive norm.

Precisely because descriptive norm‐based messages tend to reduce confidence that corruption can be effectively tackled by the existing political system, we expect them to increase support for populist and anti‐system beliefs and leaders. Such messaging certainly supports claims often made by populist leaders about the corrupt state of affairs. Moreover, a wide range of literature has drawn a causal connection between evidence of corruption, public attitudes towards the status quo, and the rise of populist leaders in the last 2 decades. This includes research on Brazil, Italy and the US (for a thorough discussion see Curini, Reference Curini2017). A study conducted by Gianmarco Daniele and colleagues (Reference Daniele, Aassve and Le Moglie2023, p.468), for example, found that ‘young first‐time voters exposed to the corruption scandal and its political consequences in the early 1990s still today have significantly lower institutional trust and were more likely to choose populist parties at the 2018 national elections’. Given that descriptive anti‐corruption messages raise awareness of the extent of graft within the existing political system, they are likely to have the same effect.

This gives rise to our first hypothesis:

H1: Messages that raise awareness of corruption through descriptive norms will increase support for populist/anti‐system ideas and attitudes.

Partly because of the problems that have been identified with descriptive norm‐based messages, some researchers have examined whether messages that instead emphasise what is known as an injunctive norm might be more impactful while having lower risks of backfiring (Agerberg, Reference Agerberg2021; Cialdini et al., Reference Cialdini, Demaine, Sagarin, Barrett, Rhoads and Winter2006, Reference Cialdini, Reno and Kallgren1990; Legros & Cislaghi, Reference Legros and Cislaghi2020; Widner & Roggenbuck, Reference Widner and Roggenbuck2000). Injunctive norm messaging does not focus on how widespread an issue is, but rather on whether people approve/disapprove of the issue. Our anti‐corruption injunctive norm message, for example, stresses the high percentage of citizens who wish to live in a graft free country. One potential benefit of such messages is that because they do not emphasise the extent of corruption, they are less likely to induce ‘corruption fatigue’ (Agerberg, Reference Agerberg2021). Moreover, because they inform citizens about the strength of public feeling against corruption, injunctive messages may be effective in reframing the perceived dominant social norms, challenging the idea that there is widespread support for and/or engagement with corruption (Agerberg, Reference Agerberg2021; Schultz et al., Reference Schultz, Nolan, Cialdini, Goldstein and Griskevicius2007; Tankard & Paluck, Reference Tankard and Paluck2016).

For these reasons, there is an emerging consensus within the social norms literature that these kinds of injunctive narratives are less likely to have the problematic consequences associated with conventional – descriptive – messages when raising awareness to social bads. For example, a well‐known study by Cialdini et al. (Reference Cialdini, Demaine, Sagarin, Barrett, Rhoads and Winter2006) examined the impact of different normative messaging designed to prevent the theft of wood from the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, USA. Messages that communicated injunctive norms discouraged such theft, while descriptive norm messaging had the opposite impact. Similarly, injunctive norm‐based messaging has been found to counteract the harmful impacts of descriptive norm messaging in studies of COVID‐19 protocol adherence (Ryoo & Kim, Reference Ryoo and Kim2021), cheating (Gino et al., Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2009) and even signing up to being an organ donor (Habib et al., Reference Habib, White and Hoegg2021).

With respect to anti‐corruption messaging, the Agerberg study introduced above is the only one to test an injunctive norm anti‐corruption message so far.Footnote 2 As noted, in that paper, Agerberg finds that exposure to a message about the fact that most people think bribery is never justifiable reduced agreement that corruption is an integral part of Mexican culture and lowered the likelihood of self‐reported willingness to pay a bribe. These are promising findings, but given that it is the only study to focus on injunctive anti‐corruption messaging, further research is required to explore whether this approach works as intended in other contexts. We therefore test an injunctive norm message, anticipating that this treatment will be less likely to prime the kinds of beliefs that Daniele et al. (Reference Daniele, Aassve and Le Moglie2023) find align with populist narratives, and hence to encourage the sense that corruption as an overwhelming problem that cannot be resolved within the existing political system. This reasoning gives rise to our second hypothesis:

H2: Messages that raise awareness of corruption through injunctive norms will not increase support for populist/anti‐system ideas and attitudes.

Research design

The data used in this study come from an original survey‐experiment that was conducted in Albania from 15 January to 27 February 2022. We worked with IDRA, an experienced research firm based in Albania, to conduct the survey‐experiment. Albania was a good location because corruption is widely recognised to be a serious problem there and it is also not a socially taboo topic to discuss. Where populism is concerned, Albania represents a suitable case study because it has seen the emergence of populist parties, and features many of the conditions often argued to be facilitative of populism, but does not currently feature a strong populist partisan divide. This is valuable, because it means that populist ideas are not seen to imply support for a particular political party in the way that it might do in, say, Brazil or the US, and so there is no risk that participants simply responded to our treatments on the basis of existing partisan lenses.

Other conditions that make Albania a relevant case, in that they are often seen to facilitate the emergence of an anti‐system party, include a series of economic crises driven by a range of factors such as failed pyramid schemes and, most recently, the challenges generated by COVID‐19, and democratic fragility. Moreover, despite holding regular multiparty elections, Albania scores just 0.4 on the Varieties of Democracy's (2023) 0–1 Liberal Democracy Index, in which higher scores reflect greater democracy, while Freedom House (2023) characterises Albania as a ‘partly free’ country characterised by the ‘intermingling of powerful business, political, and media interests’. In line with this, Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index (2023) ranks Albania as one of the more corrupt countries in the world (110 out of 180).

In 2012, this context inspired the emergence of the Red and Black Alliance, a populist movement with ‘anti‐establishment feelings at its core’ that sought to channel popular frustration with corruption and economic difficulties, along with a nationalist/far right message (Bino, Reference Bino2017, p.1). The new political movement initially looked like it might make inroads through high profile policies and statements, such as denouncing law enforcement agencies and politicians for failing to do their jobs and ‘anti‐national’ behaviour. As Blerjana Bino argues, however, the Alliance performed poorly in the 2013 general elections as a result of ‘the inability of the populist contender to present itself as a viable and credible contender against the established political parties in Albania with a persuasive, clear, consistent and simple message, strong leadership and sound organisation’ (Reference Bino2017, p.24–25). Thereafter, the Alliance faded, with some of its populist ideas being adopted by other more mainstream Albanian parties (Reference Bino2017, p.19). As a result of this process, populist attitudes are not currently identified solely with any one political party.

This situation is beneficial to our research agenda, because it means that participants had no reason to think that our project was designed to benefit or damage any current political leader, thus encouraging both engagement and frankness. It is important to note that the failure of the Red and Black Alliance was not rooted in popular antipathy to populist claims, but rather in the contingent factors identified by Bino (Reference Bino2017), most notably the movement's particular organizational and leadership limitations relative to more established rivals. Albania is therefore a particularly suitable case because while it features a society that appears to be susceptible to populism, this has not yet been fully exploited, allowing us to generate more reliable results in a country in which there is a genuine prospect of a trend towards more populist politics in the coming years. Given this context, our findings are therefore most likely to be relevant for cases in a similar position – messages may therefore have less effect in countries where populist parties dominate, for example, or where existing support for such beliefs is so high there is little scope for further increases.

When conducting our survey we used a multi‐stage stratified cluster sampling strategy to ensure that our 2,002‐person sample was nationally representative of Albanian adults.Footnote 3 This is significant, as most awareness raising survey experiments are restricted to urban only samples. All interviews were conducted in Albanian, face to face. We provide details on the demographic characteristics of the sample in the Supporting Information Appendix A.

We randomly assigned participants to one of four groups: control, corruption is widespread, corruption is transnational or public disapproval of corruption (n = 500 to 501 in each).Footnote 4 To start, all participants were asked the same set of demographic questions. If assigned to a treatment group, respondents were then asked to read their group's respective treatment paragraph (message).Footnote 5 Following exposure to the treatment (or not for those in the control group, which proceeded to the next set of questions), participants were asked a series of survey questions to gauge their attitudes towards corruption, reporting corruption, as well as their attitudes towards the government and towards populist or antisystem sentiments, which is what we focus on in this paper.

Treatments

A further advantage of conducting the research in Albania was that we were able to work with high level policy makers to design the messages we tested. More specifically, we liaised with the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) programme team in Albania to develop the treatments used. In collaboration with Albanian counterparts, the UK government has supported a range of anti‐corruption efforts and strategies designed to counter serious and organised crime. In 2021, for example, the UK and Albanian governments signed an agreement to deepen their cooperation to tackle organised crime, with their joint efforts to fight corruption viewed as an essential piece of this work given the close relationship between corruption and organized criminal activity (UK Government, 2021). Our engagement with the FCDO programme team strengthened the study because it meant that we were able to design messages that would be well suited to test the hypotheses set out above, while also ensuring they reflected content that could be used in a real communications campaign and resonated with the Albanian context. The suitability and external validity of the messages was also assessed through interviews with civil society leaders and experts working on corruption to ensure that they were realistic and similar to the kinds of messages likely to be used in the Albanian context.Footnote 6

Two descriptive‐norm messages were designed. The corruption is widespread message described corruption in Albania as being widely practiced and hampering access to public services. It also described recent high‐profile corruption scandals and the fact that most Albanians believed that corruption often occurs in the government. This message was designed to emphasise the descriptive norm of corruption being widely practiced at all levels of the Albanian government. The second descriptive‐norm message – corruption is transnational – focused on the transnational nature of high‐level corruption; it emphasised the fact that Albanian wealth and resources are lost to other countries through kleptocratic governance patterns. This message was tested because of a growing interest in raising awareness around the damage done by kleptocracy, but also because a message that invoked wounded national pride and potential losses to other countries has yet to be tested in the literature, and it was thought that it might be particularly effective at encouraging criticism of corrupt behaviours. As noted earlier, these types of descriptive norm messages are the ones most likely to be deployed in practice. Indeed, UNCAC (2004) advises that signatory states raise awareness of the problem posed by corruption and its negative consequences, with the assumption that doing so will encourage people to reject corruption and support anti‐corruption efforts. In contrast, the injunctive norm treatment, public disapproval of corruption, was designed to highlight public rejection of corrupt behaviours. This message reported that overwhelming majorities of Albanians disapproved of different forms of corruption, felt that corruption was unacceptable, and believed that certain acts of corruption should be punished. All three treatments were a paragraph long, which is consistent with the most recent literature on this topic (e.g., Agerberg, Reference Agerberg2021; Cheeseman & Peiffer, Reference Cheeseman and Peiffer2021, Reference Cheeseman and Peiffer2022; see Supporting Information Appendix B for the full text of each treatment).Footnote 7

Dependent variables

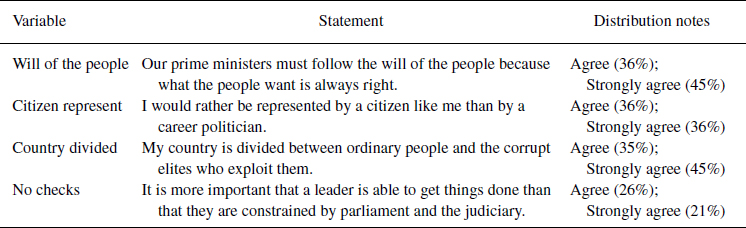

Populist or anti‐system attitudes are measured by indicated agreement with four statements in our survey. These statements (Table 1) were arrived at by considering the growing literature on measuring populist attitudes (Schultz et al, Reference Schulz, Müller, Schemer, Wirz, Wettstein and Wirth2019; Castanho Silva et al, Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020), and a contextualised understanding of the kind of populist beliefs that emerged in Albania. In particular, we build on the work of Agnes Akkerman and colleagues (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014), whose Populist Attitudes Index draws on a wide range of previous studies to set out a series of questions that tap populist attitudes. We follow Akkerman et al., both because their study is one of the most influential so far conducted, and because it has recently been found to be one of the best performing populist scales (Castanho Silva et al, Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020, p.421).

Table 1. Dependent variable statements

Our populist attitudes index includes three items included by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014, p.1329), and one additional item whose importance is suggested by recent developments in populist scholarship, as set out in Table 1. The will of the people question proposes that the will of the people should always be followed because the people cannot be wrong and is the equivalent of Akkerman et al.’s first question (‘Politicians should follow the will of the people’). The citizen representation question asks whether citizens would prefer to be represented by another citizen or a career politician, and is the same as Akkerman et al.’s fourth question (‘I would rather be represented by a citizen than a politician’). The country divided question addresses the extent to which individuals believe society is divided between elites and the people, and is in line with the third item proposed by Akkerman et al. (‘The political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people’). Following reflections on the evidence provided by focus groups and country experts, however, we modified the wording because the question used by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) was thought to be somewhat complicated and prone to misinterpretation.

Finally, in response to the recent call of Castanho Silva et al. (Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020, p.421) to go beyond existing scales in order to respond to their ‘lack of … conceptual breadth at capturing more than anti‐elitism’, our no checks question captures the degree to which participants are willing to sacrifice institutional checks on power to effect change. This question – which has often gone untested despite being central to contemporary discussions of populism – speaks both to the highly personalised nature of populist movements (Levitsky & Roberts, Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011, p.6–7; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004, p.543), and growing concern about the willingness of citizens operating within a populist belief system to tolerate – and even approve of – attacks on checks and balances institutions (Ren et al., Reference Ren, Carton, Dimant and Schweitzer2022). Such concerns have a long history but have become particularly acute following the attack on the US Capitol by Trump supporters in January 2021 (Keenan & de Zavala, Reference Keenan and de Zavala2021).

Theoretically, the will of the people and citizen representation are questions that most directly signal a desire for a form of populist leadership, because they reify the popular will and imply a distaste for professional politicians and traditional forms of governmental decision‐making. The country divided question does not directly imply support for populist leadership but rather for a populist understanding of politics and society (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). Meanwhile, the no checks question is the one that most clearly tracks undemocratic attitudes, as the removal of constraints on a given leader directly undermines a core feature of democratic government, at least when understood from a Madisonian perspective. It therefore presents perhaps the strongest evidence that corruption can encourage demands for a broader set of far‐reaching changes, including to the political system itself. Taken together, the four questions therefore provide a set of different but complementary perspectives on the question of whether anti‐corruption messaging encourages individuals to hold classic populist beliefs, support populist leadership and tolerate moves to undermine democratic accountability.

The same five‐point Likert‐scale was used to measure agreement with all four statements, with possible responses ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Table 1 displays the exact wording of each statement. Amongst the full sample, there was considerable agreement with these populist sentiments. Just under half agreed that it is more important for a leader to get things done, than have institutional constraints on their power (no checks), three‐fourths agreed that they would rather be represented by a citizen than a career politician (citizen represent) and a striking four‐fifths agreed that the country is divided between ordinary people and corrupt elites (country divided), as well as that the prime minister should follow the will of the people because it is always right (will of people).

A principal component factor analysis (PCFA) was used to extract the maximum common variance from responses to all four questions so as to create a singular populism attitudes index. The PCFA found that the four items loaded on a single dimension with an eigen value over the standard threshold of 1.0 (1.81), which supports the notion that responses to these four questions are articulating a shared, latent measure of ‘populist attitudes.’ The continuous index ranges from −3.77 to 1.45, with a higher score indicating greater agreement with populist sentiments.

Estimation strategy

To evaluate the impact of messaging in an experiment like this, pair‐wise difference in means (DIM) tests can be used as long as it is fair to assume that the only difference between respondent groups is that they were exposed to different messages or were not exposed to a message at all (control group). DIM tests with basic demographic indicators across groups showed that the corruption is widespread group had a significantly higher percentage of rural dwellers than the control, public disapproval of corruption, and corruption is transnational treatment groups.Footnote 8 There were, however, no significant (i.e., p‐value < 0.05) differences among the four groups with respect to the other demographic variables tested (i.e., age, gender, education, and socio‐economic status).Footnote 9

We therefore conducted regressions rather than DIM tests when examining what impact exposure to each message had on agreement with populist sentiments in order to control for the potential impact of urban/rural locale, ensuring that any differences in responses we detect across groups are not due to any variations in the composition of our groups. An ordinary least squares (OLS) regression examined the impact of exposure on the populist attitudes index, created using factor analysis. For ease of exposition and interpretation, four additional ordered logistic regressions examined the impact of exposure on agreement with each of the four statements, individually. These analyses helped us to also estimate the substantive impacts of exposure to the treatments with regards to the response options of the original four survey questions that we use to form the populism index.

Our three treatments are substantially different to one another, because descriptive and injunctive messages follow very different logics, and so our aim is to test what impact exposure to each of our messages has on agreement with the populist sentiments scrutinised. This is different to some messaging experiments, which aim to compare the impact that a subtle difference in messaging makes. For this reason, we focus our analyses on estimating the influence of exposure to each message by comparing responses to those who did not receive a message (control). As such, in all analyses, the baseline group is the control group, and all reported messaging impacts represent these comparisons – between those exposed to a message and those who were not.

The impact of anti‐corruption messages on populist sentiment

As a reminder, H1 suggests that exposure to the two descriptive norm messages which describe the scale of the problem and the harms corruption causes – corruption is widespread and corruption is transnational – will result in greater agreement with the dependent variable statements, while H2 suggests that exposure to the injunctive norm message, public disapproval of corruption, will not impact on agreement with the populist sentiments, captured by our dependent variable statements.

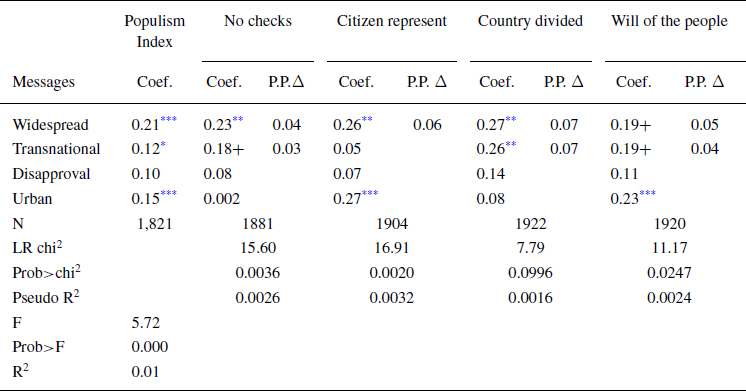

The effects associated with exposure to the corruption is widespread message provides considerable support for H1 (Table 2). Being shown this message is significantly associated with a greater degree of agreement with the populism index (p‐value < 0.01, two‐tailed test). In analysis of the index's constituent terms, it is therefore no surprise that exposure to this message is similarly associated with greater agreement with all four dependent variable statements. Specifically, using a two‐tailed test, exposure is associated with greater agreement that a participant would rather be represented by a citizen than a career politician (citizen represent), that the country is divided between ordinary people and corrupt elites (country divided), and that it is more important for a leader to get things done than have institutional constraints on their power (no checks) at the p‐value < 0.05 level. It is worth noting here that our no checks variable is distinctive in capturing an unequivocally undemocratic sentiment, and so this latter finding represents the strongest evidence that the corruption is widespread message works to undermine attachment to core democratic principles. Exposure is also associated with greater agreement with the final statement – that the prime minister should follow the will of the people because it is always right (will of the people). It is worth noting, however, that in this instance the impact of exposure is significant at the p‐value < 0.05 level, using a less strict one‐tailed hypothesis test.Footnote 10

Table 2. Impact of messaging on populist sentiments

Notes: Level of significance indicated by: *** for p‐value < 0.01, ** for p‐value < 0.05; *for p‐value < 0.10 (two‐tailed); + for p‐value < 0.10 (one‐tailed). Coefficients are reported in the left column for each of the constituent dependent variables. In the right column, predicted probability changes are displayed, which are the estimated change in the probability of responding with ‘strongly agree’ to the statement associated with exposure to messaging. These predictions were only calculated for those instances where messaging was found to have had a likely impact on response patterns (p‐value < 0.05).

As noted earlier, the four models in which we use the index's constituent terms as dependent variables facilitates an exploration into the substantive impact of exposure. For this reason, we display the estimated shifts in predicted probability of strongly agreeing with each statement associated with exposure to the treatments. These shifts show that the corruption is widespread message likely has the largest impact on agreement with the country divided and citizen represent statements. In these instances, exposure is associated with a seven and six‐percentage point increase in the predicted probability of strongly agreeing with these respective statements. For the will of people and no checks questions, exposure is predicted to have increased the probability of strong agreement by 5 and 4 percentage points, respectively.Footnote 11

These estimated shifts should also be considered in light of the already high levels of agreement with these statements in Albania. An examination of our control group is instructive, as their responses were not impacted by exposure to messaging. Two fifths of control group participants strongly agreed with the country divided and will of people statements (41 and 42 per cent, respectively), while almost a fifth (19 per cent) and about a third (32 per cent) strongly agreed with the no checks and citizen represent statements, respectively. These figures show that, in the absence of messaging, there is already a significant level of populist sentiment in Albania. Thus, for a significant percentage of our participants, exposure to messaging would not have been able to nudge greater agreement because their agreement levels (at least in the way we have measured it) had already peaked. It is therefore striking that we find that the corruption is widespread message has encouraged agreement to the extent it has across a range of indicators for which there tends to already be high levels of agreement.

The results also provide some support for H1 when considering the impact of exposure to the other descriptive norm message: corruption is transnational. In this case, exposure is associated with higher scores on the populism index (p‐value < 0.10, two‐tailed test). When examining its impact across the index's constituent variables, a similar picture emerges. This message is associated with a greater degree of agreement with the country divided statement (p‐value < 0.05, two‐tailed test). Specifically, exposure is estimated to have a seven‐percentage point increase in the predicted probability of having strong agreement with this statement. We also find weaker support for the notion that exposure to the transnational message increased agreement with the no checks and will of people statements in the form of one‐tailed tests (p‐value < 0.05 one tailed test). In these cases, exposure is estimated to have a more modest three and four‐percentage point increase in the predicted probability of strong agreement with these respective statements. In contrast, exposure to the transnational message is not found to be associated with changes in agreement with the citizen represent statement.

There are two plausible explanations for the fact that this message did not encourage populist ideas as much as the corruption is widespread treatment. First, it may be that by mentioning a number of different actors in a range of contexts and countries, the corruption is transnational treatment spreads the blame for corruption more widely that the corruption is widespread treatment. Respondents may perceive that foreign nationals and interests are partly responsible, for example, making it less likely that they will be moved to reject the current national political class. Second, and relatedly, by emphasising transnational networks the treatment may encourage individuals to think about the organized crime networks that play a prominent role in discourse about Albania, which – again – may deflect attention away from the Albanian government. While many Albanians suspect that serious and organized crime (SOC) networks are connected to and tolerated by the government (Bino, Reference Bino2017), this relationship is less direct and explicit than examples of corruption within government ministries.

The results in Table 2 also provide consistent support for H2. As expected, exposure to the injunctive norm treatment, public disapproval of corruption, is not found to have significantly (p‐value < 0.05) impacted scores on the populism index or agreement with any of the constituent dependent variable statements. These ‘null’ findings are important for two reasons. First, they represent an important caveat to the idea that any message that mentions corruption will prime respondents to think of the scale of the problem and so have unwanted effects. Second, they add to the very small evidence base on the impact of injunctive norm anti‐corruption messaging (Agerberg, Reference Agerberg2021). More specifically, our results in this area suggest that by emphasising the extent of popular opposition to corruption rather than focusing on the scale of the problem, injunctive norm messaging campaigns can avoid having the unwanted side‐effect of encouraging populist attitudes. This is encouraging, especially given that exposure to the descriptive norm messaging we tested was largely found to have this undesired externality.

While our findings suggest that injunctive norms may do less harm than their descriptive counterparts, however, it is worth noting that we do not find that they are likely to have compelling positive effects in the areas they are intended to change, namely anti‐corruption sentiment. We conducted further tests (Supporting Information Appendix C) to examine how exposure to all three messages impacts on beliefs about the acceptability of bribery and willingness to engage in anti‐corruption protests or report corruption. As it relates to the injunctive message, these analyses were largely inspired by Agerberg's (Reference Agerberg2021) findings, which showed that exposure to an injunctive norm anti‐corruption message had a positive effect on anti‐corruption sentiments. By contrast, all three of our messages – including public disapproval of corruption – were largely found not to have impacted perceptions of how acceptable bribery was, or willingness to engage in anti‐corruption civic activities (p‐values > 0.05).Footnote 12

Taken together, our two sets of analyses thus suggest that while injunctive norm anti‐corruption messaging may avoid the negative externality that descriptive norm messaging risks of encouraging agreement with populist ideas or undermining anti‐corruption sentiment, it is no silver bullet. Thus, our results indicate that both injunctive norm messaging and descriptive norm messaging are unlikely to work as intended.Footnote 13

Conclusion: How to respond to the pandemic of graft in the age of populism

The findings of this paper suggest that policy makers, civil society groups, journalists and politicians need to be careful in the way that they seek to address the ‘pandemic of graft’. Indeed, the classic strategy of raising awareness to the extent and impact of corruption may generate negative consequences with implications for both corruption and democracy. While the existing literature suggests that conventional ‘descriptive norm’ narratives have little impact or can even backfire, our research demonstrates that they may also have the unwanted side‐effect of encouraging citizens to adopt populist beliefs and attitudes.

As with all experimental studies, it is important to be careful about generalizing our findings. As noted above, Albania represents a particular political context, in which populist ideas resonate but do not at present structure the party system in a low‐quality democracy. While many countries around the world fall into this category, it is feasible that our findings would be weaker in states where: there is a higher level of democracy; populist ideas have lower resonance; and/or populist leaders have risen to office. Moreover, anti‐corruption messages are sometimes part of a wider set of anti‐corruption interventions, whereas in our study messaging was not integrated into a multifaceted campaign. It is feasible that other aspects of a broader anti‐corruption programme could mediate the way in which citizens respond to messages, enhancing their effectiveness. Our findings are therefore most generalizable to anti‐corruption messaging that is not clearly embedded within a high profile set of initiatives and interventions. Significantly, however, such messaging is considerably more common, especially in countries in which corruption is seen to be a major challenge to development and anti‐corruption adverts and posters are ubiquitous.Footnote 14 Finally, our study focuses on the immediate impact of receiving anti‐corruption messages, and it may be that their effect falls or, indeed, changes over time. We therefore need further research to better understand these relationships and the durability of their effect on political behaviour.

These caveats notwithstanding, there are good reasons for thinking that the cumulative impact of the effects that we find could create a more facilitative environment for the rise of populist leaders. In countries as diverse as Brazil and the US, scholars have shown how concerns over corruption drove support for populist anti‐system leaders. Moreover, a large literature has demonstrated that political affiliation is shaped by how close a leader or parties’ beliefs and policies are to those of the voter (Green et al, Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004; Lenz, Reference Lenz2012), and that individual‐level populist attitudes drive support for populist parties (see, for example Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Kaltwasser and Andreadis2020). This suggests that by nudging individuals towards more populist beliefs, descriptive norm based anti‐corruption campaigns reduce barriers to populists’ electoral success.

If anti‐corruption narratives shape vote choice, in one sense this is not necessarily problematic: stale and corrupt political establishments may benefit from being challenged, especially if populist movements channel popular desires for more responsive and accountable government. Outlandish populist leaders may be distasteful to the status quo, but if their success is based on building popular support – as it was for figures such as Zambia's Michael Sata, whose government subsequently increased spending on education and instituted a national minimum wage (Siachiwena, Reference Siachiwena2016) – it clearly rests at least partly on democratic foundations.

Given the track record of populists where corruption is concerned, however, anti‐graft campaigners have good reason to beware of bringing populists to power, even if they are not concerned they will be divisive and exclusionary in office. As noted above, despite campaigning vigorously against the ‘corrupt elite’, populists have a remarkably poor record of managing graft in office (Daly, Reference Daly2020; Putzel, Reference Putzel2020). One reason for this is that populists tend to undermine institutional checks and balances and weaken mechanisms of accountability as part of their determination to ‘get things done’ (Kostadinova, Reference Kostadinova2023; Zhang, Reference Zhang2023). In turn, this weakens what barriers to corruption exist within a political system, facilitating a deterioration in governance standards. In some cases, such as the Trump presidency in the US, this process resulted in an almost immediate series of scandals and controversies, coupled with the decline in the country's score on the Corruption Perception Index, and later led to prosecutions of some of the administration (Zhang, Reference Zhang2023).Footnote 15

This reality raises the thorny question of how to respond to an increase in corruption without actually making the situation worse. Injunctive norm messages offer one possible solution to ‘do no harm’, but the one we tested did not have the intended effect of strengthening public anti‐corruption attitudes. This outcome suggests that campaigns based on this kind of message may not represent good value for money, and that more research is required to see how and to what extent our negative finding – as opposed to the positive results presented by Agerberg (Reference Agerberg2021) – represent the norm.

These red flags should not mean that anti‐corruption messaging campaigns should all be halted, however, as this course of action would also have downsides, such as declining public concern about the issue. It is therefore important to identify new ways to develop narratives that do no harm, and to test messages before they are deployed to assess their impact. One avenue for future research to explore, for example, is whether exposure to injunctive normative information about corruption could nullify any unwanted impact that exposure to descriptive normative information might have. This kind of research may help policy makers to strike the right balance between exposing corruption and avoiding the negative effects of doing so.

An additional factor that may influence the efficacy of messages – and of anti‐corruption campaigns more generally – is the actual performance of the government. Bo Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2021) has argued that citizens are most likely to be encouraged to join the fight against corruption when governments make credible commitments to challenge the corrupt status quo. This implies that individuals are unlikely to be moved by messages if they are not matched with concrete change that gives citizens confidence those in power share their concerns. This is an interesting insight but it hinges on the question of what counts as a credible commitment, and under what circumstances citizens view the statements and actions of their leaders as embodying a genuine desire to effect change. In many of the countries in which populist leaders came to the fore, they did so because their appeals seemed to be more credible than those of incumbents – despite their own often disputed characters. As Heinisch has argued (Reference Heinisch2003), this is partly because, coming from the opposition, aspiring populists do not have a track record in government against which they can be evaluated and found wanting.

Applying Rothstein's (Reference Rothstein2021) insight more broadly, we also might expect anti‐corruption messaging to be more impactful where prior anti‐corruption campaigns have been more successful. One challenge with effectively assessing the impact of prior success and government commitment, however, is that effective interventions are relatively rare occurrences in countries where corruption remains a major issue – at least in so far as they generate approval across party lines. In many countries – including China, Nigeria and the US – anti‐corruption campaigns become mired in accusations that they are a ‘witch‐hunt’ designed to purge rival leaders either inside (Wedeman, Reference Wedeman2017) or outside (Ogundiya et al., Reference Ogundiya, Ogundiya, Olutayo and Amzat2011) the ruling party, and so fail to build a broad base of public confidence in anti‐corruption efforts. In future research, we hope to conduct comparative studies to better understand how this kind of variation in past performance shapes the impact of anti‐corruption messaging in the future.

If perceptions of the success of past campaigns are critical to shaping the impact of anti‐corruption messaging today, our findings become even more worrying. When awareness raising messages reduce the perceived credibility of the government, while also encouraging citizens to believe that only populist leaders can deal with the challenges they face, they are likely to contribute to public scepticism of anti‐corruption activities and institutions. In other words, anti‐corruption awareness raising campaigns may not only facilitate support for anti‐system parties but also make it harder for governments that are interested in strengthening accountability institutions to persuade citizens to support their efforts. If so, the need to find more effective and less damaging ways to fight graft is more urgent than ever.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by UK Foreign, Commonwealth, & Development Office, through the Serious Organised Crime & Anti‐Corruption Evidence (SOC ACE) research programme. We are grateful to the FCDO‐Albania programme team for working with us on the design of this research, and to the team at IDRA for assisting us with conducting the fieldwork. We also thank Niheer Dasandi and Heather Marquette for reviewing previous drafts and providing helpful feedback. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the UK Government's official policies.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: