Suicide among adolescents and young adults represents a global mental health crisis in the early 21st century.Reference Cavelti and Kaess 1 -Reference Chen, Su, Hsu and Tsai 3 According to World Health Organization mortality data spanning 2010 to 2016, the estimated suicide rate for individuals aged 10–19 years is 3.8 per 100 000 people.Reference Cavelti and Kaess 1 , Reference Glenn, Kleiman and Kellerman 2 In Taiwan, the suicide rate increased annually from 6.1/100000 in 2008 to 9.1/100000 in 2019, making suicide the second most prevalent cause of death among Taiwanese people aged 15–24 years in 2019.Reference Spinney 4 , Reference Chang, Lin and Liao 5 A 2021 nationwide community-based telephone interview study reported that among Taiwanese adolescents aged 15–19 years, the prevalences of lifetime and 1-week suicidal ideation (SI) were 11.4% and 2.8%, respectively.Reference Pan, Lee, Wu, Liao, Chan and Chen 6 Chou et al. indicated that approximately 12% and 9% of female and male Taiwanese college students, respectively, had attempted suicide at least once in the preceding 12 months.Reference Chou, Ko, Wu and Cheng 7

Several neuroimaging studies regarding adult suicide samples have highlighted the crucial role of functional dysconnectivity in reward-related circuits (ie, nucleus accumbens [NAc], ventral tegmental area [VTA]) and executive control–related circuits (ie, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [DLPFC]) in the pathophysiology of suicide.Reference Kim, Bartlett, DeLorenzo, Parsey, Kilts and Caceda 8 -Reference Pu, Nakagome and Yamada 13 Kim et al. observed that adult individuals who had attempted suicide within the preceding 3 days showed increased gray matter volume in the NAc compared with nonsuicidal patients with depression.Reference Kim, Bartlett, DeLorenzo, Parsey, Kilts and Caceda 8 Misaki et al. examined the NAc responses to gain and loss anticipations in the monetary incentive delay task in 44 adults with major depression (MD) and 45 healthy controls and revealed that both hyperactivity and suppressed activity in the NAc were associated with SI.Reference Misaki, Suzuki, Savitz, Drevets and Bodurka 9 A single-photon emission computed tomography imaging study demonstrated that decreases in regional cerebral blood flow in the VTA and bilateral superior frontal cortex were associated with resistance to antidepressants and suicide among patients with MD.Reference Willeumier, Taylor and Amen 10 Wang et al. employed graph theory analysis based on resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) data and revealed that individuals with a history of attempted suicide (SA) had lower nodal strength in the NAc and subgenual anterior cingulate cortex compared with both patients without SA and healthy controls.Reference Wang, Zhu and Dai 11 A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study involving 17 adults with MD and SI (MDSI), 34 with MD without SI, and 34 healthy controls demonstrated that the patients in the MDSI group, but not those with MD without SI, had lower activation in the right DLPFC compared with the healthy controls during an emotional autobiographical memory task.Reference Zheng, Da and Pan 12 Pu et al. reported that SI was associated with reduced DLPFC activation during a verbal fluency task in patients with MD.Reference Pu, Nakagome and Yamada 13 However, given the developmental disparities between the adolescent brain and the adult brain in terms of structure and function, whether the aforementioned neuroimaging findings related to suicidality can be generalized to adolescent patients with MDSI remains uncertain.

In the present study, we analyzed rs-fMRI data by using the bilateral NAc, VTA, and bilateral DLPFC as seeds. Our aim was to determine the functional connectivity (FC) within reward-related and executive control–related circuits among three groups: adolescents with MDSI, those with MD without SI, and healthy controls. We hypothesized that adolescents with MDSI would exhibit greater functional dysconnectivity in the reward-related and executive control–related circuits compared with those with MD without SI and healthy controls.

Methods

Participants

The Taipei Veterans General Hospital Institutional Review Boards approved this research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were provided by all adolescent participants as well as their parents. In all, 21 adolescents aged 12–17 years with MDSI, 33 with MD without SI, and 48 age- and sex-matched healthy adolescents were enrolled in the present study. MD diagnosis was given by board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). SI was defied based on scores of ≥2 (wishes he/she were dead or any thoughts of possible death to self) on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS) item 3, while no SI was defined as HDRS item 3 scores ≤1.Reference Hamilton 14 , Reference Vuorilehto, Valtonen, Melartin, Sokero, Suominen and Isometsa 15 SI was operationalized as HDRS item 3 ≥ 2 (vs. ≤ 1 = no SI) in the present study, consistent with prior validation showing moderate concordance with alternative SI assessments (κ ≤ 0.64).Reference Vuorilehto, Valtonen, Melartin, Sokero, Suominen and Isometsa 15 Furthermore, adolescents with intellectual disability, neurodevelopmental disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance/alcohol use disorder, eating disorder, organic mental disorder, pregnancy or breastfeeding, severe autoimmune diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, epilepsy, and unstable physical illnesses were excluded. Depressive symptoms were measured using the HDRS.Reference Hamilton 14 Healthy adolescents had no DSM-5 diagnosis and denied any family history of a DSM-5 diagnosis. All adolescents fulfilled the self-reported Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS),Reference Soloff, Lynch and Moss 16 and their parents fulfilled the parent-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).Reference Hannesdottir and Einarsdottir 17 The sum of subscale scores for anxious/depressed, aggressive behavior, and attention problems of CBCL was used as the clinical marker of emotional regulation (Dysregulation Profile, CBCL-DP).Reference Biederman, Spencer and Petty 18

Image acquisition

MRI images were obtained using a 3-Tesla scanner (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK) with a quadrature head coil at the Taipei Veterans General Hospital. Anatomical whole-brain T1-weighted images were captured using a magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo three-dimensional T1-weighted sequence with the following parameters: TR = 12.2 ms, TE = 5.2 ms, 168 axial slices, flip angle = 12°, FOV = 256 × 256 mm, matrix size = 256 × 256, and slice thickness = 1 mm. The rs-MRI was procured using a T2*-weighted gradient-echo approach, echo-planar sequence with the following parameters: TR = 2500 ms, TE = 30 ms, 43 axial slices, flip angle = 90°, and voxel size = 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 mm. Each subject underwent the acquisition of 200 MRI volumes while maintaining closed eyes, a state of mental neutrality, and refraining from any movement or falling asleep.

Image data preprocessing

The preprocessing of the functional and anatomical data was conducted through a comprehensive pipeline using the CONN toolbox.Reference Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon 19 The initial step involved realignment using the SPM12 (Statistical Parametric Mapping, https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) realign & unwarp procedure. All scans were co-registered to a reference image (the first scan of the first session) using a least squares approach and a six-parameter (rigid body) spatial transformation. Subsequently, b-spline interpolation was employed for resampling to correct for motion. Temporal misalignment between different slices of the functional data, which were acquired in an interleaved bottom-up order, was rectified using the SPM slice-timing correction procedure. This involved sinc temporal interpolation to resample each slice blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) time series to a common mid-acquisition time. Outlier scans were identified using artifact detection tools (ART) Reference Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon 19 as acquisitions with framewise displacement above 0.9 mm or global BOLD signal changes above five standard deviations.Reference Power, Mitra, Laumann, Snyder, Schlaggar and Petersen 20 A reference BOLD image was computed for each subject by averaging all scans excluding outlier images. The functional and anatomical data were then normalized into standard MNI space, segmented into gray matter, white matter, and CSF tissue classes, and resampled to 2 mm isotropic voxels. This was achieved using a direct normalization procedureReference Calhoun, Wager and Krishnan 21 that employed the SPM unified segmentation and normalization algorithm with the default IXI-549 tissue probability map template.Reference Ashburner and Friston 22 , Reference Ashburner 23 Finally, the functional data were smoothed using spatial convolution with a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm full-width half-maximum. This comprehensive preprocessing pipeline ensured that the data were optimally prepared for subsequent analysis. Moreover, a standard denoising pipelineReference Nieto-Castanon 24 was applied to the functional data. This involved regressing out potential confounding effects represented by motion parameters and their first-order derivatives,Reference Friston, Williams, Howard, Frackowiak and Turner 25 outlier scans,Reference Power, Mitra, Laumann, Snyder, Schlaggar and Petersen 20 session effects and their first-order derivatives, and linear trends within each functional run. Subsequently, bandpass frequency filtering of the BOLD time series was conducted, limiting the frequency range between 0.009 Hz and 0.08 Hz.

Seed-based connectivity

Seed-based connectivity (SBC) maps were generated to characterize the spatial pattern of FC with a seed region. The analysis involved the bilateral NAc, VTA, and bilateral DLPFC serving as seed regions. FC strength was quantified using Fisher-transformed bivariate correlation coefficients derived from a weighted general linear model (GLM).Reference Nieto-Castanon 24 This model was separately estimated for each seed area and target voxel, capturing the association between their respective BOLD signal time series. The Harvard–Oxford atlases were used to anatomically label the peak voxels of significant FC clusters.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY; Version 25). To evaluate differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, continuous variables were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, while nominal variables were assessed using Fisher’s chi-square tests. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the examination of significant differences in SBC among the three groups, group-level analyses were executed using GLM with age and sex as covariates of no interest. Inferences were drawn at the cluster level, based on parametric statistics from Gaussian random field theory.Reference Worsley, Marrett, Neelin, Vandal, Friston and Evans 26 Results were thresholded using a combination of a cluster-forming p < 0.001 voxel-level threshold and a corrected p-FDR < 0.05 cluster-size threshold. For the exploration of correlations between identified FCs and clinical measurements, the z-scores of significant peaks from individual SBC maps were extracted for group comparisons. A correlation analysis with the adjustment for age and sex was used to assess the association between the identified FCs and HDRS item 3 scores. Correlation analyses were also performed to evaluate the associations of total HDRS scores, total BIS scores, and CBCL-DP scores with the FCs of these regions by partial correlation coefficients adjusted for group, age, and sex, with the significance level set at α = 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Taiwan’s clinical trial ethical regulation but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

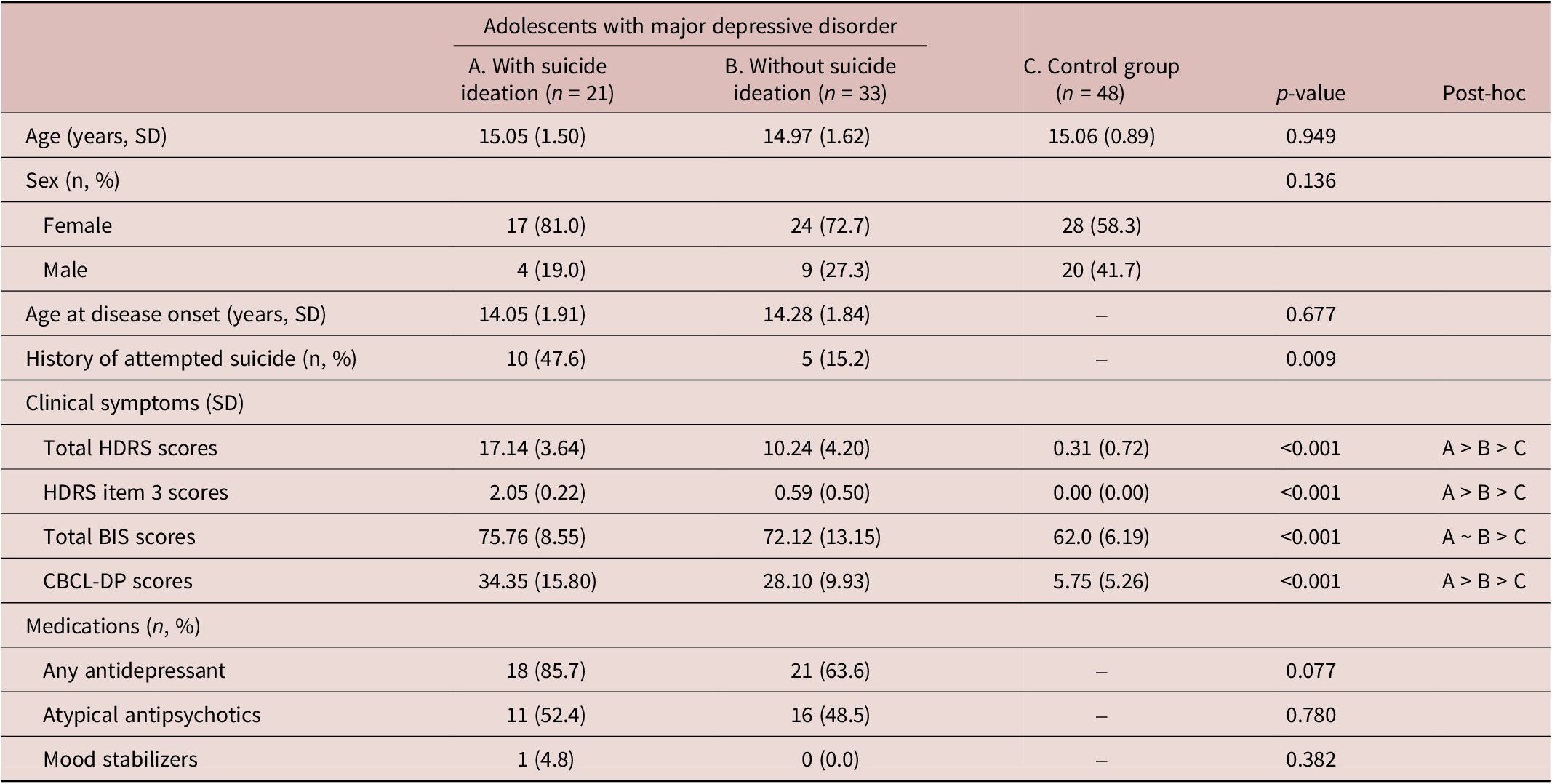

Table 1 shows our analysis sample, with a mean age of 15 years and a female predominance, revealing no significant difference in age at disease onset (p = 0.830) between the two patient groups. Total HDRS scores and CBCL-DP scores were highest (p < 0.001) among adolescents with MDSI (Table 1). Adolescents in two depression groups had higher total BIS scores (p < 0.001) than did the control individuals (Table 1). Adolescents with MDSI showed a significantly higher prevalence of a prior history of SA compared with those with MD without SI (p = 0.009) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Groups

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; HDRS, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BIS, 30-item Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; CBCL-DP, Child Behavior Checklist Dysregulation Profile.

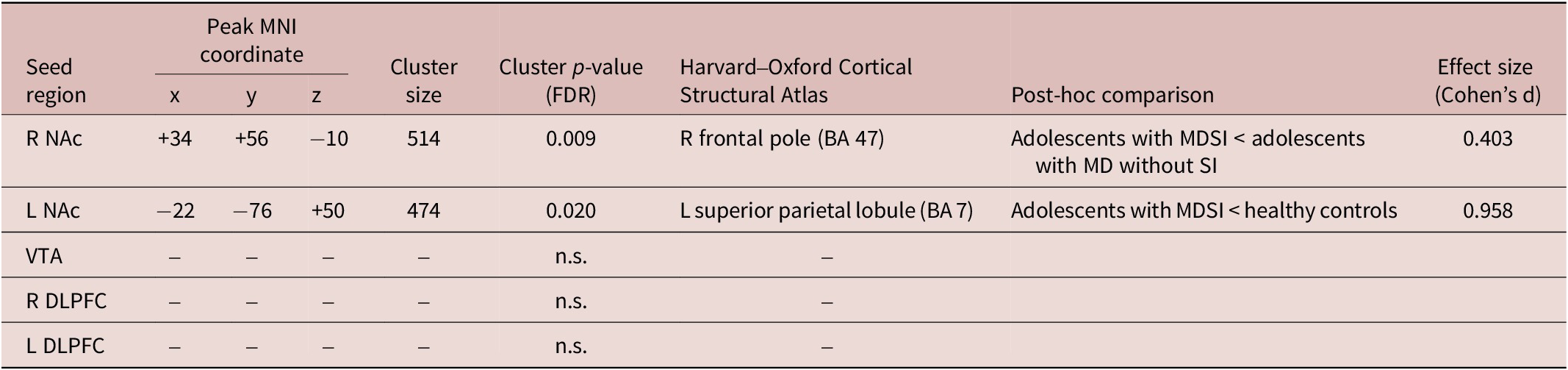

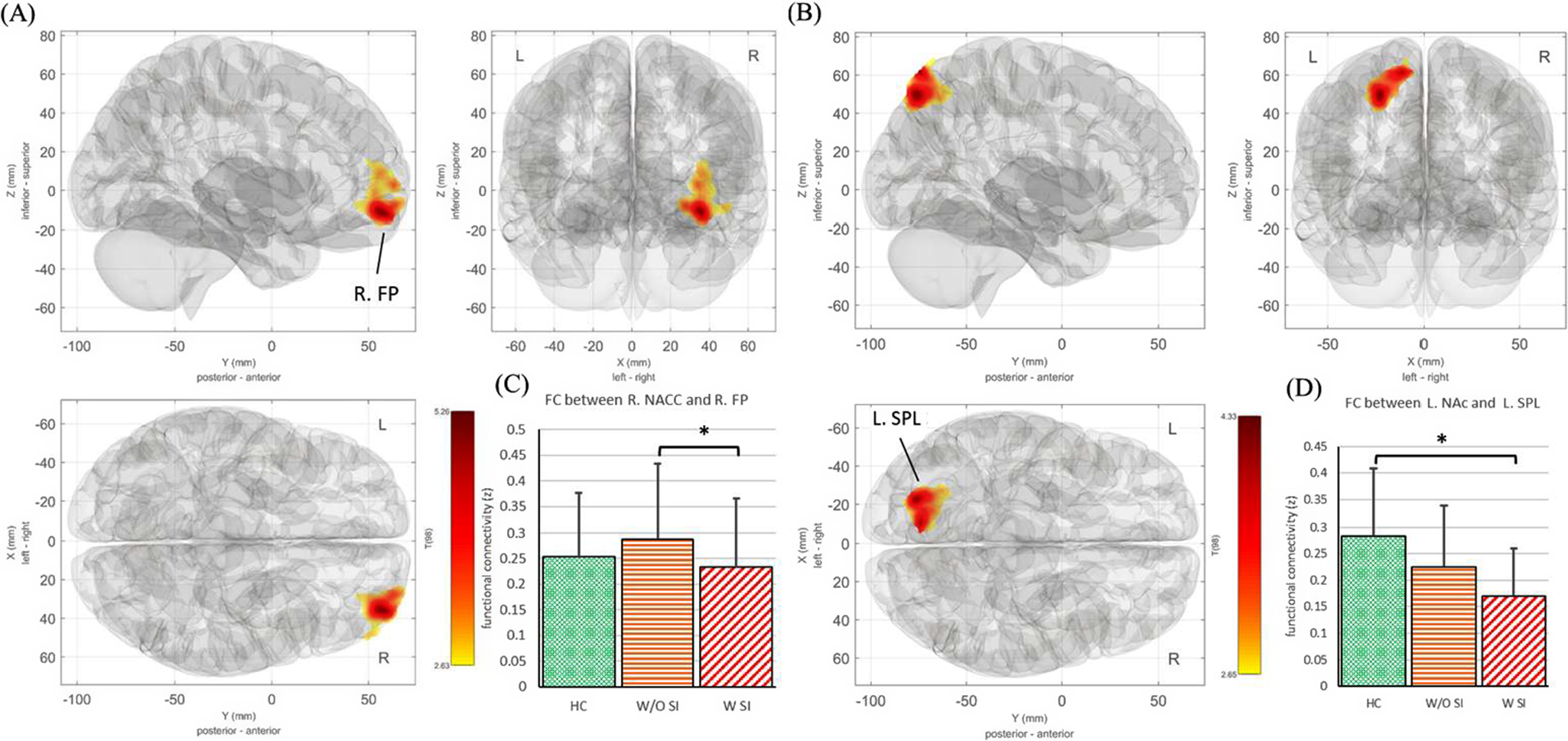

The SBC analysis indicated that adolescents with MDSI showed decreased FC between the right NAc and the right frontal pole (BA 47) compared with those with MD without SI (corrected p-FDR < 0.05) (Table 2, Figure 1A, B). In addition, adolescents with MDSI showed reduced FC between the left NAc and the left superior parietal lobule (BA 7) compared with those in the control group (corrected p-FDR < 0.05) (Table 2, Figure 1C,D). No significant differences in SBC, seeded from the VTA and bilateral DLPFC, were observed among the three groups.

Table 2. Significant Differences in Seed-Based Functional Connectivity among Groups (p < 0.05)

Abbreviations: R, right; L, left; NAc, nucleus accumbens; VTA, ventral tegmental area; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; MD, major depression; SI, suicidal ideation.

Figure 1. (A) The FC seeded from the R NAc revealed a significant difference among the three groups. (B) The FC seeded from the L NAc revealed a significant difference among the three groups. (C) The FC between R NAc and R FP was post-hoc analyzed between groups. (D) The FC between L NAc and L SPL was analyzed across the three subject groups. FC: functional connectivity; R: right; L: left; NAc: nucleus accumbens; FP: frontal pole; SPL: superior parietal lobule; HC: healthy control; W/O SI: adolescents with depression without suicidal ideation; W SI: adolescents with depression with suicidal ideation.

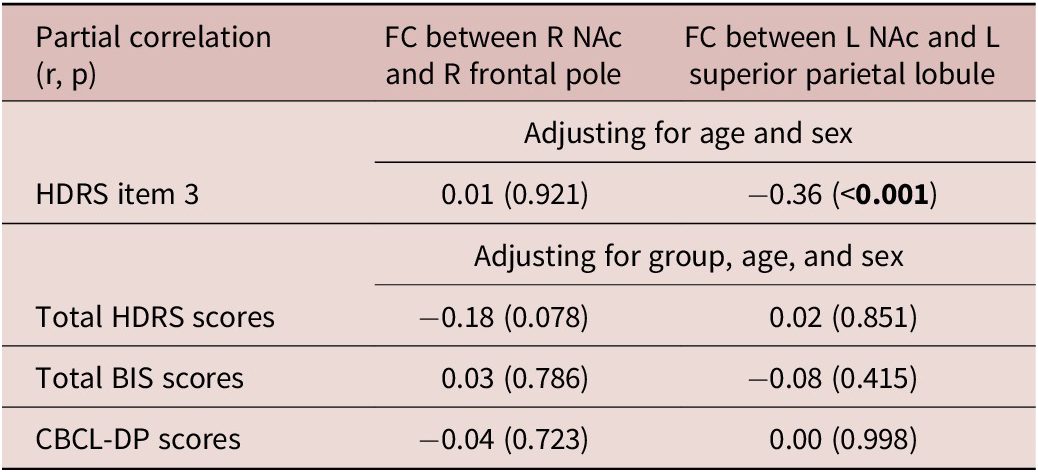

Finally, we explored the correlations between the identified FCs and clinical measurements (Table 3). HDRS item 3 scores were negatively related to the FC between the left NAc and the left superior parietal lobule (r = −0.36, p < 0.001) (Table 3). After adjusting for groups, age, and sex, no statistically significant correlation was observed between the FC of the right NAc and the right frontal pole, as well as the FC of the left NAc and the left superior parietal lobule, with clinical measurements (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation Analyses between FCs and Psychological Measurements

Bold type indicates the statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Abbreviations: FC, functional connectivity; R, right; L, left; NAc, nucleus accumbens; HDRS, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BIS, 30-item Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; CBCL-DP, Child Behavior Checklist Dysregulation Profile.

Discussion

Our findings partially support the study hypothesis that adolescents with MDSI show greater functional dysconnectivity seeded from the NAc compared with those with MD without SI and healthy controls. In particular, reduced FC between the left NAc and the left superior parietal lobule (BA 7) was observed in adolescents with MDSI compared with healthy controls. Additionally, reduced FC between the right NAc and the right frontal pole (BA 47) was observed in adolescents with MDSI compared with those with MD without SI. Against our expectations, no differences in DLPFC-seeded FC were identified among the three groups.

Our neuroimaging findings revealed crucial roles of NAc-related functional dysconnectivity with both the frontal pole and the superior parietal lobule in the MDSI pathomechanism in the present adolescent population. These findings align with the existing evidence highlighting dysregulation in the reward system as a contributing factor to suicidality.Reference Swann, Lijffijt, O’Brien and Mathew 27 -Reference Schmaal, van Harmelen and Chatzi 29 The frontal pole (BA 47) is associated with language processing, comprehension, and emotional recognition, particularly negative emotions such as fear, disgust, and anger.Reference Sprengelmeyer, Rausch, Eysel and Przuntek 30 , Reference Snow 31 Furthermore, Snow et al. proposed that the frontal pole (BA 47) is a cognitive hub responsible for practical intelligence in humans, thereby emphasizing its role in the elaboration and communication of practical reasoning.Reference Snow 31 They described the “material mind” as a prefrontal system supporting practical intelligence, such as perceiving and acting on the physical, object-based world, chiefly localized to BA 47.Reference Snow 31 A postmortem study of 15 matched brain pairs, including one from an adolescent who had died of suicide, identified lower neuron density in BA 47 in the suicide brains compared with the control brains.Reference Underwood, Kassir, Bakalian, Galfalvy, Mann and Arango 32 Myung et al. established an association between reduced structural connectivity in regions involved in executive function (ie, the superior parietal cortex and frontal pole) and total scores on the Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI) in patients with MD.Reference Myung, Han and Fava 33 Additionally, Kim et al. revealed that young adults aged approximately 20 years with high suicidality (total Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised [SBQ-R] score > 7) showed reduced FC between the right frontal pole and bilateral inferior frontal cortex compared with those with low suicidality (total SBQ-R score ≤ 7).Reference Kim, Farabaugh and Vetterman 34 This finding is consistent with the present findings, suggesting that adolescents with MDSI show reduced FC between the right NAc and right frontal pole compared with those with MD without SI. The findings of both Kim et al. and the present study suggest that dysfunction in material mind processing is associated with suicidality among adolescents with depression.

Evidence has highlighted the crucial role of the superior parietal lobule (BA 7) in processes such as visuospatial and attentional processing, as well as working memory.Reference Koenigs, Barbey, Postle and Grafman 35 , Reference Wang, Yang and Fan 36 Specifically, Koenigs et al. identified that damage to the superior parietal lobule (BA 7) was associated with deficits in mental manipulation and the rearrangement of information within working memory.Reference Koenigs, Barbey, Postle and Grafman 35 In adults with MDSI, van Heeringen et al. observed hypometabolism in the middle frontal cortex and superior parietal lobule compared with those with MD without SI.Reference van Heeringen, Wu, Vervaet, Vanderhasselt and Baeken 37 Cao et al. further indicated that prefrontal-parietal (superior parietal lobule) dysconnectivity was associated with SI and levels of impulsivity in young people with depression with a prior history of suicide attempts.Reference Cao, Chen and Chen 38 Consistent with this finding, in another study, dysconnectivity related to the superior parietal lobule was associated with executive dysfunction as well as the total SSI score in patients with MD.Reference Myung, Han and Fava 33 The present study identified reduced FC between the left NAc and left superior parietal lobule (BA 7) in adolescents with MDSI compared with healthy controls.

Additionally, we observed an inverse association between HDRS item 3 scores and FC in the left NAc and left superior parietal lobule. However, no association was observed between FC in the left NAc or the left superior parietal lobule and impulsivity or emotional dysregulation in adolescents with depression.

Notably, our investigation revealed no differences in bilateral DLPFC-seeded FC among the three adolescent groups. This outcome contrasts with the findings of prior studies that have underscored the importance of such dysconnectivities in adult patients with MDSI.Reference Zheng, Da and Pan 12 , Reference Pu, Nakagome and Yamada 13 A potential explanation for this variance lies in the incomplete development of DLPFC by the age of approximately 25 years. This developmental distinction in our adolescent sample might have contributed to the disparity between our findings and those derived from adult populations.Reference Arain, Haque and Johal 39 Our findings suggest that although reward-related functional dysconnectivity plays a pivotal role in the pathomechanisms of adolescent suicidality, executive control–related functional dysconnectivity may not exhibit the same prominence. Tailoring suicidal prevention strategies to target reward regulation could be highly effective for treating at-risk adolescents with depression.Reference Schleider, Mullarkey and Fox 40 For example, a behavioral activation intervention for depressed adolescents, which was designed to enhance motivation for change and develop a structured activity “action plan,” reduced depressive symptoms at 3 months and lowered hopelessness both post-intervention and at 3-month follow-up.Reference Schleider, Mullarkey and Fox 40

Several limitations of the present study warrant consideration. First, this study did not require adolescents with MDSI and those with MD without SI to discontinue their medications. This feature of the study design was deemed ethically appropriate for high-risk adolescents and would offer data that were relatively naturalistic. Additionally, no significant differences in the usage patterns of psychotropic drugs—including antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and atypical antipsychotics—were observed between the two adolescent groups with depression. Second, the mean age of the adolescents in our study was approximately 15 years. Thus, considering the ongoing developmental changes in the adolescent brain, the generalizability of our findings to older adolescents, particularly those aged ≥17 years, warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, our study revealed that adolescents with MDSI showed reduced FC between the right NAc and right frontal pole (BA 47) compared with those with MD without SI. Furthermore, adolescents with MDSI demonstrated reduced FC between the left NAc and left superior parietal lobule (BA 7) compared with their healthy counterparts. These findings suggest that functional dysconnectivity in the reward-related circuit, specifically that involving the FC between the NAc and both the frontal pole and the superior parietal lobule, may play a crucial role in the pathomechanisms of suicidality in adolescents with depression.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr I-Fan Hu for his support and friendship.

Author contribution

Drs MHC, LCC, and JWH designed the study; Drs LKC and PCT analyzed the neuroimaging data; Drs WSH, JWH, and LKC drafted the manuscript; Prof LFC and Dr YMB performed the literature reviews; all authors reviewed the final manuscript and agreed to the publication. JWH and WSH contributed equally to this work.

Financial support

The study was supported by grants from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V113C-039, V113C-011, V113C-010, V114C-089, V114C-064, V114C-217); Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation (CI-113-32, CI-113-30, CI-114-35); Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST111–2314-B-075 -014 -MY2, MOST 111–2314-B-075 -013, NSTC113–2314-B-075-042, NSTC 114–2628-B-A49–008 -MY3, NSTC114–2314-B-075-022, NSTC114–2314-B-075-023); Taipei, Taichung, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Tri-Service General Hospital, Academia Sinica Joint Research Program (VTA112-V1–6-1, VTA114-V1–4-1); Veterans General Hospitals and University System of Taiwan Joint Research Program (VGHUST112-G1–8-1, VGHUST114-G1–9-1); and Cheng Hsin General Hospital (CY11402–1, CY11402–2). The funding source had no role in any process of our study.

Disclosures

None of the authors in this study had any conflict of interest to declare.