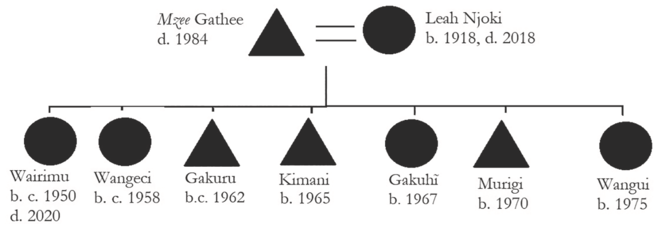

When I returned to Ituura in 2019, the neighbourhood had noticeably changed. Walking around with Mwaura once more, I found that the distinctive red earth of the road that cut through the neighbourhood had been overlaid with stones in preparation for it to become asphalt. At the roadside, we found a group of men, neighbours from Ituura households, finishing their day’s work filling ditches made during the road’s construction. ‘Peter! We’ve become an estate!’ (Tumekuwa estate), one of them remarked, surveying the new road (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Building the new road in Ituura, 2019

Figure 6.1Long description

In the foreground, a man with a trowel stands next to a dirt-covered road, reinforced with stone. Behind him, the road continues through houses and walled compounds. Other figures stand there, moving building materials in a wheelbarrow. Trees loom in the distance.

Ironic reflections on Ituura ‘becoming an estate’ evoked transformations taking place across southern Kiambu – the construction of gated communities of newly built houses catering to those Mwaura identified as Nairobi’s ‘working class’, office workers with reliable salaries. But Ituura was also changing because residents were building rental ‘plots’, as they were called, concrete housing units, on their own freehold land.Footnote 1 Back in 2017, only one or two homesteads played host to these one- or two-storey rows of ‘bedsitters’– single rooms, primarily aimed at young Nairobi commuters and informal economy workers. But in 2019, Ituura looked noticeably less rural than it had, even in 2018 when the construction of these newer plots had begun. It really was beginning to look like an estate. Every homestead, it seemed, was making plans for the future through investment in plots.

Land Disputes at Home

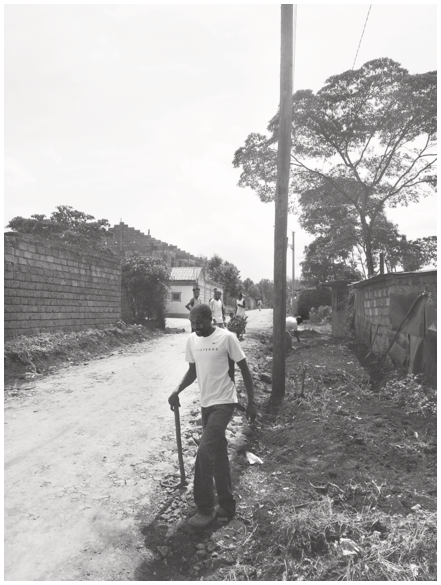

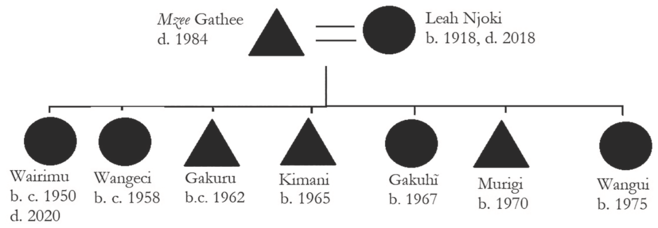

If the wider neighbourhood was becoming ‘more of Nairobi’, as Mwaura had once described this process of urbanisation, things in his family were not as I had left them either. The death of Kimani’s elderly mother Leah Njoki at the astonishing age of 100 had reconfigured the strip of land that had been divided between him and his siblings (Figure 6.2). Dispute had ensued.

Figure 6.2 Kimani’s family tree

Figure 6.2Long description

The family tree indicates that Mzee Gathee, Kimani's father, died in 1984 and was married to Leah Njoki who was born in 1918 and died in 2018. They had seven children. They are, Wairimu, a girl, born around 1950, and who died in 2020, Wangeci, a girl, who was born around 1958, Gakuru, a boy, who was born around 1962, Kimani, a boy, who was born in 1965, Gakuhi, a girl, who was born in 1967, Murigi, a boy, who was born in 1970, and Wangui, a girl, born in 1975.

The dispute hinged around Kimani’s attempt to repatriate his older sister Wangeci to the family homestead. A divorced single mother in her forties, Wangeci had been living in Chungwa Town during my fieldwork between January 2017 and July 2018. During that time, we had never met, but in 2019, Mwaura proudly introduced me to his aunt, whose house he was helping to build on a small piece of land allocated to her behind the wooden house where his family continued to live. As in 2018, Kimani’s ‘stone’ (mawe) house stood unroofed and unfinished further towards the road on his own plot, separated by tall hedges, still a concrete shell, and an obdurate symbol of his failure as a provider and a patriarch.

Kimani himself had been central to Wangeci’s return home, arguing, in the wake of his mother’s death, that Wangeci deserved a place to live at the patrilineal homestead as a rightful daughter of his father Gathee. Kimani’s brother Murigi had objected. ‘Kimani said she should be given land. Murigi didn’t want this’, Catherine told me in Kiswahili, recounting the discussions that had taken place after Leah’s burial (her mother-in-law).Footnote 2 I tried to ask Kimani about the dispute, suggesting to him that John had refused. ‘Why will he refuse? (Atakataa kwanini)’, Kimani answered in anger. ‘She’s already been given (Ameshapewa)’, he said, insisting that her return to the homestead was his final word on the matter.

During my stay, these simmering tensions became an open dispute. Murigi sent news to Kimani and Catherine that he intended the land apportioned to Wangeci to be re-divided. He argued that neither of his younger sisters, Gakuhĩ and Wangui, had been given land at the family homestead. Throughout my fieldwork, the land of Kimani’s mother, Leah Njoki, continued to provide a home for his youngest sister Wangui, who had never married. Of the other sisters, Gakuhĩ had married a man living in another neighbourhood, and had left the family homestead in her twenties, foregoing claims to family land. Wangui was expected to inherit her elderly mother’s house directly, and nothing larger. For Wangeci, redividing the land boundaries would have jeopardised the foundations of her house, likely resulting in their removal. But more than that, it was a signal that she was not wanted back at the family homestead, at least not by Murigi. In the days that followed, Mwaura found Wangeci in tears.

‘I don’t know what’s come over them’, Mwaura told me, speaking of his uncle Murigi and his aunts Gakuhĩ and Wangui. Murigi had always used the land given to Wangeci – land that previously belonged to his elderly mother – to grow maize. Wangeci’s return to the homestead had deprived Murigi of this informal extension of his own land. Mwaura could therefore see the reasons for Murigi’s evident dislike of Wangeci’s return. ‘She is the only one who will have maize’, he explained. But Mwuara believed that more was at stake, and speculated that Murigi wanted to purchase the land from either Wangui or Gakuhĩ and then sell it. ‘There is something!’, Catherine suggested when the news arrived of Murigi’s desire to have the land re-divided amongst his sisters. ‘Imagine!’, she asked in an exaggerated tone of shock. ‘She is your sister!’ Catherine was determined that Murigi’s’s dispute would not dampen their determination to welcome Wangeci home. ‘We will finish that house’, she insisted. ‘God will provide.’

The news of Murigi’s intention to have the land re-divided also came with a threat of eviction to Kimani. Murigi warned him to leave the temporary wooden house, since the land it was on in theory had belonged to Leah Njoki and would therefore pass to either Gakuhĩ or Wangui with his proposed re-division. As a warning, he blocked access to the borehole on his land through which Wangeci was accessing water. The pressure grew on Kimani to complete his house, whilst Mwuara and Catherine continued to wonder if they would ever relocate down the hill to their prospective new home.

Intimate Exclusions

The two observations that begin this chapter demonstrate Ituura’s status as a site of new urban development through the construction of rental plots upon ‘ancestral’ land, but also of the complex kin-based claims to which this land, highly limited as we have seen, is subject. At the cusp of an expanding city, this chapter explores how these two processes have become entangled.

This book has already observed the way landholdings in Kiambu have shrunk across generations with sub-division amongst multiple heirs. In Ituura, as with other such pockets of smallholders, a family may have barely half an acre on which to grow food, hardly enough to cover subsistence. Yet, through the possibility of rent and speculation, land across Nairobi’s metropolitan outskirts has become more valuable than ever. Media commentators have spoken about a ‘gold rush’ on land, provoked by a growing appreciation of its potential to generate future value, its ‘capacity for development as yet unrealised’ (Strathern Reference Strathern1996: 17). The problem most Kiambu residents face is that because of low wages relative to the (rising) price of land, purchasing it is extremely difficult.Footnote 3 With wages generally low, spent on subsistence and other household commitments such as school fees for children, land acquired at the juncture of inheritance is a vital resource, inheritance itself a golden opportunity. With the stakes high, conflicts about who gets what at the window of inheritance evince a politics of inclusion and exclusion. Arguments coalesce around the question of who is in and who is out of the family.

This chapter develops the book’s inquiry into the nature of land contestation in an urbanising Africa as the city expands into its formerly rural hinterlands. It does so by drawing upon the insights of scholars who have studied the effects of agrarian land reform in rural settings that have been shaped by colonial-era expropriation and land reform (see, e.g., Haugerud Reference Haugerud1989; Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie1989; Berman and Lonsdale Reference Berman, Berman and Lonsdale1992; Berry Reference Berry2002; Peters Reference Peters2002; Shipton Reference Shipton2009; Amanor Reference Amanor2010; Boone Reference Boone2014). We have already observed the way ownership of land in Kiambu was concentrated within the hands of senior men through the distribution of freehold title deeds (Chapter 1), and begun to explore its consequences in terms of land sale (Chapter 3). But such reforms have also shaped the character of land disputes on Nairobi’s urbanising frontier. Catherine Boone’s (Reference Boone2014) survey of land politics in Africa has shown how the legacies of land reform in western Kenya have focused struggles over land ‘within extended families and are fought over attempts to narrow the boundaries of the family’ (Boone Reference Boone2014: 189). As we have already seen, the fault-lines of such conflicts are deeply gendered. Murigi’s attempt to disrupt the inheritance of his sister speaks to the way land’s limited yet highly prized status interacts with ideas about women’s status as rightful inheritors within a setting like Ituura, where land no longer passes on exclusively from fathers to sons but still remains prone to claims of patrilineal exclusivity. While Wangeci’s return was supported by her senior male kin like Kimani, Murigi saw his own claims to patrilineal land curtailed. Within central Kenya’s landscape of patrilineal plots, women have typically been the losers of land conflicts, forced to leave their natal homes or to purchase land elsewhere as insurance against eviction (Boone Reference Boone2014: 62, 189; cf. Maas Reference Maas1986; Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie1989).

Such exclusions are enabled by the ambiguities that surround ownership, its complex subterranean histories in the post-land-tenure-reform era. As Angelique Haugerud and Caroline Mwangi (Reference Haugerud and Mwangi2024) have recently illustrated, the very introduction of title deeds conceals the multi-temporal narratives and cross-cutting claims to which land is subject in practice rather than in law. In Ituura, as across Kiambu and central Kenya’s landscape of peasant plots, fathers often pass land to their children without formally transferring title. Entire families can live on their parents’ freehold land without legal right. Such informal arrangements continue to persist within the era of freehold land, and it is precisely these ambiguities that become fraught in the context of inheritance. As zero-sum conflicts break out within families over scarce land, comfort with these customary arrangements becomes subject to question. Inheritors come to regret that they had not had title deeds transferred into their own names sooner.

Throwing these ambiguities into relief, this chapter explores the junctures of conflict created by the deaths of parents, the way kin members seek to exclude each other’s access to land in the context of land scarcity, what Derek Hall, Philip Hirsch, and Tanya Murray Li (Reference Hall, Hirsch and Li2011: 21, 166) have described as practices of ‘intimate exclusion’ or ‘enclosure from below’. In the cases I explore here, claiming land as personal property, formally or informally, resembles what Hannah Elliott calls ‘propertying’ – ‘material practices of claiming exclusive ownership to plots of land’Footnote 4 that she argues characterises the very anticipation of land’s future value. In a changing Kiambu, it is precisely anxieties about other claims that might trump one’s own, which structure a desire for title deeds through which property can be permanently ‘fixed’ through the promise of official paper (Guyer Reference Guyer2004: 155), at least in theory (cf. Bolt Reference Bolt2021).

Observing a gendered politics of intimate exclusion, I explore the way male fears about the loss of land manifest in desperate and sometimes violent attempts to enclose property against female inheritors within their families. Fuelling these fears are male anxieties about downward mobility, their own expectations that they would inherit land exclusively from their fathers, and the assertion that women are likely to sell inherited land because of their mobility in marriage. Both older and younger men are shown to be anxious about their economic status, and fear that their own sisters can ‘go ahead’ of them by exploiting their capacity to both inherit land and acquire it through marriage. Inheritance conflicts are thus not only ones of exclusion, but conflicts of class-based futures yet to come, ones borne of anticipated divergences in life chances that relative access to land is thought to bring. Attitudes towards women’s inheritance reflect the desperate position of men with which this book’s wider narrative arc has been concerned.

Against the backdrop of these conflicts, I explore the strategies Ituura residents adopt to contain these tensions, strategies that both anticipate conflict, and which are composed in the immediacy of it. I draw attention to their use by women who are forced to act strategically – hiding documents from men and seeking support from influential family members – in order to cement their rootedness and positions within the patriline. Tacitly, their rights to land are also claimed against the backdrop of male destitution, where addiction and poverty is seen to have rendered men poor guardians of the land.

‘A little investment’

‘Just a little investment.’ That was how Mama Janice had described it in 2018 speaking about the new rental plots she was constructing in her garden, adjacent to her house. Her late husband’s state pension had afforded her the chance to build. I was curious about what had motivated her to build in her back garden, practically next to her house on a plot that was barely half an acre.

By the time I spoke to her, Mama Janice’s plots were already a topic of discussion in the neighbourhood, and seen as evidence of her family’s economic progress. But the act of building had caused rifts within her social circle of influential neighbourhood women. Mwaura recounted the meeting where Mama Janice announced her construction project, held at his house, between Catherine, Mama Nyambura, and Mama Janice. ‘Mama Nyambura wasn’t happy when she heard the news’, he explained. As a response, Mama Nyambura had set out to construct her own, in Mwaura’s view, ‘just so for Mama Janice not to be better than them’. Mwaura felt that when he had listened to Mama Nyambura question whether Mama Janice needed to build plots, he detected ‘jealousy’ (wivu).

We encountered Mwaura’s commentaries about the significance of wivu in Chapter 5, where he cast Ituura as a highly competitive environment, one where families are conscious of each other’s successes and failures. As Julie Soleil Archambault (Reference Archambault2018) has argued in the case of the rapidly expanding city of Maputo, concrete constitutes a powerful indicator of middle-class security through its associations of durability: an upgrade from wood and corrugated iron. Rental plots were no exception. Beyond the associations of concrete, they telegraphed that a homestead now had an extra source of income, reducing its reliance upon wages.

The new plots of Mama Nyambura and Mama Janice therefore captured the growing feeling in Ituura that generating rent was a reliable source of income. Consider the words of one Ituura resident who had constructed rental buildings in 2019:

Rental plots built 100 years ago might still be here today. I could have bought a matatu (minivan) and the following day it gets into an accident. What if I invest in agriculture and my harvest gets damaged by bad weather or lack of market? There’s no loss in rental plots.

A few weeks after Mama Janice had begun building, Mama Nyambura invited Mwaura and I her to her homestead, proudly showing us the construction under way. The new units stood next to her own home, a row of one-story bedrooms with adjoined bathrooms. According to Mwaura, one would need to be ‘someone’ to rent such high-end rooms, and it was noticeable that these rentals were far larger than Mama Janice’s. He and I both knew that his family would have been unable to undertake such a project. The effect of these constructions was to further the felt economic distance between Mwaura’s family and Mama Nyambura and Mama Janice’s.

However, as we are about to see, the transformation of one’s land into housing was not a straightforward matter but one that required the careful demarcation of one’s property within the family. When locally influential women such as Mama Nyambura were building and quite literally cementing their status within an ostensibly patrilineal neighbourhood, they fell foul of male claims to exclusive inheritance and were drawn into disputes of intimate exclusion.

Gendered Jealousy

‘When our father dies that’s when all of this trouble starts’, said Jata. Together with Feye, we had been walking back from church on the backstreets behind houses and farms that lead from Chungwa Town towards Ituura on a Sunday morning in April 2018. Gradually, the sprawl of Chungwa gave way to the maize fields of the peri-urban neighbourhood, and the blocks of rental plots under construction on some of the homesteads we passed. Our conversation had turned towards the tensions that surround land in the context of a dispute playing out in Mama Nyambura’s family. Jata had been reflecting upon the deaths of parents as the starting gun on such conflicts, intensifying ambiguities over who would receive what of the family land, taking what was once collectively held though limited goods into private ownership.

In December 2017, months before she had constructed her plots, Mama Nyambura’s father Njohi had passed away. Two months later, her eldest living brother Gicheha also died. This left Mama Nyambura with two surviving male siblings – the young Mũrakaru (twenty-eight) and Joseph, her older brother in his late forties who was disabled due to an impaired leg caused by a car accident in his youth.

On the day of Gicheha’s funeral, at the time when family traditionally meets to discuss affairs of inheritance, Mũrakaru and Mama Nyambura had argued. Mũrakaru asserted his right to take control of his father’s assets – a pickup truck and a block of rental accommodation – as ‘the man of the house’ (mũndũ rũme). After being told of the events by Mama Nyambura herself, Catherine narrated them in our house, giving Mũrakaru’s statement a demanding tone when he had apparently instructed his older sister to bring the documents such as the title deed and accounts information to him.Footnote 5 ‘I’m the one who has been left the man of the house. I’m the one who will be overseeing dad’s property’, he had insisted.Footnote 6

However, together with her mother, wa Njambi, Mama Nyambura refused Mũrakaru’s claims. Wa Njambi herself pointed towards the wife of the late Gicheha, arguing that she now embodied the male rights over the property her brother had possessed in life.Footnote 7 ‘Only if she dies would you oversee the documents. There is no way you can overtake her’, wa Njambi insisted. Meanwhile, Mama Nyambura had concealed the documents that Mũrakaru demanded, and he struggled to find them in his mother’s house.

What happened next confounded many of Ituura’s residents. In anger at his mother and elder sister’s decision and his failure to find the papers, Mũrakaru broke into the family compound at night and set alight to the pickup truck and his mother’s home where Joseph also stayed. Fortunately, the family woke up in time to ensure the house did not burn down, though the vehicle was destroyed. Mũrakaru was taken to the police station but eventually released. No charges were brought.

Inheritance Denied

Mũrakaru’s attempt on the lives of his mother and brother, or at the very least to destroy their house, speaks to the frustration of what he thought was a valid claim to his father’s land and pickup truck. He had failed in his bid for what he saw as his right to patriarchal authority over his father’s property as the ‘man of the house’. Denied that, he took matters into his own hands. Like Murigi, Mũrakaru saw his own prosperity to be threatened by his female relatives – his mother, his sister, and sisters-in-law – who had denied him what he saw as his rightful inheritance. Given the rising value of land and the long-standing primacy of patrilineal inheritance amongst only male heirs, Mũrakaru and Murigi’s pursuit of their patrilineal inheritance, and their insistence on the primacy of their rights over that of their sisters, was not surprising. But the very failure of Mũrakaru’s attempt to seize control of his father’s property captures the nature of changing inheritance patterns in central Kenya, and the increasing ‘customary’ recognition of women’s rootedness.

Kenya’s Law of Succession, commenced in 1981, has provided a point of contention ever since its introduction when it made provision for all ‘dependents’ (including wives and daughters) to inherit property from their fathers. But it has been described as a ‘dead letter’, in the words of Maria Maas (Reference Maas1986). Her study of women’s groups in Kiambu highlighted their attempts to purchase land as insurance against failed marriage in the knowledge that one would never be able to return home to the parental homestead and claim land there. Fiona Mackenzie (Reference Mackenzie1989) observed this gendered pattern of land conflict in central Kenya at that same moment: ‘Where pressure on the land is severe, the possibility of a sister obtaining land is likely to be the source of dispute’ (104).

However, in 2019, towards the end of my fieldwork, Justice Lucy Waithaka of the High Court in Nyeri ruled in a case brought by a group of women seeking to inherit land from their late father that married women could indeed inherit property from their parents. The ruling kicked off fierce debate in central Kenya about the status of daughters. Conservatives were quick to reiterate the mobile status of women – that they essentially did not belong on their father’s land since their fate was to marry into another family. They insisted that women were ‘in between’, to borrow Marilyn Strathern’s description of women’s liminal status in patriarchal Melpa (Reference Strathern1972: 142; cf. Gregory Reference Gregory1997: 29). Wachira Kiago, chair of the Kikuyu Council of Elders, made the point thus:

When a woman gets married, she moves from her father’s clan to her husband’s clan, where she belongs henceforth. She can only be dependent on the clan of her husband. Coming to claim property from her father’s family is like her clan of marriage demanding property from where she came from.

As Jack Goody (Reference Goody and Hann1998: 205, his emphasis) once wrote, ‘Women with property are the opposite of women as property.’ Women’s inheritance promised a subversion of patrilineal kinship in which women moved between families in this way.

Kiago’s words captured the fears of male inheritors – that women would accumulate twice, both as wives (acquiring land from their husband) and daughters (acquiring land at the patrilineal homestead). Not only was such a possibility viewed as unfair by men but economically disastrous, especially if women sold family land that they believed ought to have been theirs. The perspectives of some of my young male interlocutors from the Star Boyz team reflected Kiago’s concern.

Our customs don’t support women inheriting lands. Not unless the land is so big, and the father agrees to give a piece of land to the girl though I don’t support this. They [women] stay with what their husbands have not what our fathers have. Our fathers’ properties belong to us men.

In my case I will be against it [his sisters inheriting] cause in the end they end up selling the land since they have another where they are married yet men are left with no land to give to their children to inherit. It’s an issue on our side considering we [are a family of] three guys. There ain’t any land left when it’s divided.

These tensions mirror other contexts where inheritance is thought of as patrilineal in male ideology but has been challenged by changing legal frameworks that introduce women’s right to inherit. Scholars studying farming families in Europe have noted that ‘suspicion now pervades attitudes towards women in the patriarchal ideology of the farming way of life’ (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2004; Price and Evans Reference Price and Evans2006). Women who are ‘good as gold’ do not pursue their legal rights and ‘remain silent partners in the farm economy’ (Price and Evans Reference Price and Evans2006: 289), providing farm labour but without gaining legal ownership to the farms of their husbands, nor taking farming decisions independently. Nyita Rao (Reference Rao2018) has shown in her ethnography of Santal women in Jharkhand, India, that women faced similar reputational dilemmas in their pursuit of heritable land (see also, Rao Reference Rao2005: 737–8). Usually, women were encouraged not to inherit and allow land to pass into the hands of male agnates (Rao Reference Rao2018: 248). Local discourse emphasised that ‘a good woman’ is supposed to do precisely this (Rao Reference Rao2018). By contrast, there is the figure of the dain, a witch or witch-like figure, ‘presented in opposition to this image of a “good woman” – one who is assertive and sexually free, not a good mother or a good wife, and a threat to processes of both production and reproduction’ (Rao Reference Rao2018: 300).

Rao insists that growing levels of conflict over land in Jharkhand were a sign of women asserting their rights to own land. The ascription of the dain label to such women was used by men to police their increasing assertiveness. Underlying this growing tension, Rao notes, is the economic precarity faced by both genders. As in Kiambu, men felt women should give way to their land claims in the context of dwindling landholdings, sub-divided over generations.Footnote 8 ‘While both sides are now in a precarious position, struggling to survive, neither side is prepared to give in’ (Reference Rao2018: 248).

Yet, the reality in Ituura, as across Kiambu, is that women have become rooted within their patrilineal homesteads as inheritors not because of legal provision but because of parental, and specifically paternal, will – what we might call ‘customary’ authority. Hidden in the Wathuta High Court case record was the testimony of the deceased’s elderly neighbour Kanyiri Ndehu. Ostensibly summoned to confirm that the deceased indeed had four daughters who stood to be legitimate inheritors, the ninety-two-year-old Ndehu added an intriguing detail, ‘that in Kikuyu culture married daughters get no inheritance from their father; [but] that this was in the past and that he would gladly divide his land to his daughters’.

The instability of marriages has long been recognised by father figures from rural patrilines. Typically, in rural Kenya, when a woman bore a child out of wedlock, her father tended to reserve a share of his land for her (Kershaw Reference Kershaw1997). Mackenzie noted (Reference Mackenzie1989: 105) in her Murang’a research from 1984, a growing willingness amongst fathers to allocate land to their daughters. She speculated it would only become prominent amongst households with larger landholdings, but my research suggests that, in central Kenya today, a growing recognition of women’s rights is informing a new approach to women’s inheritance of property.

In practice, fathers are recognising their obligations towards daughters because marriages are gauged as unstable. Customary ‘come-we-stay’ marriages are widely viewed as uncertain prospects (cf. Neumark Reference Neumark2017: 750), and women regularly return ‘home’ to the land of their fathers, requiring a place to stay. On this basis, even the conservative Kiago argued that unmarried women should be able to inherit.

These trends have to be understood within the wider dynamics noted in this book: the growing significance of women within their natal patrilines against the backdrop of male poverty (Chapter 5). Women like Mama Nyambura have become powerful proprietors of patrilineal land, entrusted by their parents in contrast to their brothers, who are seen as liable to sell land. In short, she had invested in the patriline of her father in a way that, normatively speaking, followed the life pattern of sons rather than daughters. Mama Nyambura had been able to create economic networks throughout the neighbourhood and leverage the wages of her daughter to further her prosperity (Chapter 4). Mũrakaru, meanwhile, held the status of a pauper. Mwaura saw him as a social failure who was likely to sell the family land if he could acquire it. That Mũrakaru destroyed the pickup truck he coveted is significant here too. Mũrakaru planned to sell it. While Mama Nyambura and her mother also planned to sell it, this was specifically to purchase a small shop space for their younger brother Joseph in Ituura.

In our household, it was clear that Catherine and Mwaura empathised with Mama Nyambura as a dutiful protector of family land and for doing things that ‘made sense’ economically. In spite of his claims to customary authority as the ‘man of the house’, economically speaking, Mũrakaru was in a weaker position. He lacked allies within the family and without. As Fiona Mackenzie (Reference Mackenzie1989: 103) has put it, following Okoth-Ogendo (Reference Okoth-Ogendo1989), the ‘degree of power which may be actualised through the deployment of customary practices of inheritance’ can vary, depending on the life history and social capital of the parties deploying those customary arguments. Mũrakaru’s tarnished reputation and lack of allies within the family had been critical to his loss of authority and his loss of face.

In practical terms, however, Mama Nyambura had won in her attempts to retain control of her father’s plots, not through recourse to law but through ‘informal’ means – deployed notions about the authority of widows and the covert strategies she had used, the concealment of documents, for instance. Catherine saw Mama Nyambura as being clever (mũgi) in her decision to keep essential paperwork such as her father’s title deed to herself, rather than leave it in the house of Gicheha’s widow, where Mũrakaru might have found it. But such conduct was also seen as justified as a response to the dangers of allowing property to pass to Mũrakaru. ‘He will just waste it’, Mwaura argued, suggesting that Mũrakaru would sell the pickup for alcohol money.

Ugly Emotions and the Practice of Intimate Exclusion

The shock of dispute confounded the expectations of rootedness held by Wangeci and Mama Nyambura respectively. That such events were shocking suggests that their expectations of rootedness were hardly unusual. But insofar as inheritance disputes created shock and dismay within families, they also became mechanisms for the further alienation of their individual members from one another.

Characterised as unruly and individualistic, Murigi and Mũrakaru (and others like them) were seen to transgress values of kin-based solidarity by asserting their own specific rights above the inclusion of others. Theirs was aggression beyond reason. If Kimani and Murigi’s brotherly friendship had not exactly been warm in the past, the latter’s attempt to evict the former was utterly appalling. ‘Even me, I’m shocked!’, said Mwaura when he first told me of Murigi’s gambit to redivide the land in 2019. Mũrakaru’s destruction of the pickup had been just as disturbing in Mama Nyambura’s family. ‘Me? They wanted to burn me so they could eat my things when I’m not there? But they’re not lucky’,Footnote 9 Catherine reported the elderly wa Njambi as saying when she realised what her son had tried to set her house aflame. Exaggerating somewhat, Mwaura suggested that Mũrakaru should have been beaten ‘until crippled’ (ũcio agĩrĩirwo ahũrwo onje).

I had only one vantage point on each of these respective disputes, but in the partiality of this vantage point, one can observe the way ambiguities over inheritance are seen to foment unruly and greedy intent. The case of Mũrakaru’s failed gambit for taking control of his father’s property illuminates not only shifting gendered patterns of patrilineal inheritance, but also ideas about the need to anticipate and diffuse the ‘ugly emotions’ (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Mehtta, Bresciani and Strange2019) that arise from inequality within the family, not least the ‘jealousy’ (wivu) that land conflicts are seen to create. We have already explored the dynamics of wivu in Chapter 4, where we saw how economically weaker figures who attempt to become dependents are cast as envious by ‘well-up’ persons. The very force of envy itself was seen to be a pathway to potential violence. Mama Nyambura had concealed her daughter’s return to China out of fear that Mwaura would have somehow attempted to harm them. As we are about to see, a similar construction of family members as unreasonable, greedy, and potentially violent helped to justify their exclusion and the formal enclosure of land – a defence mechanism against these anticipated emotions breaking forth when property was at stake

Reasons for Enclosure

After the incident at the homestead, the disgruntled Mũrakaru accepted defeat in his attempt to take control of his father’s property. But Mama Nyambura’s travails upon her father’s death did not end with her brother’s destruction of the pickup. A few weeks after Mama Nyambura had begun constructing her rental accommodation, Catherine was shocked to find her in tears. I found out through conversations with Catherine that one of Mama Nyambura’s sisters, wa Mukina, who had married a man who lived in Chungwa Town, had decided to bring a case to the local chief that the land of their late father ought to be sub-divided again. In short, this sister claimed she had never been given a portion of her father’s land under the Law of Succession Act. The deaths of her father and elder brother had apparently renewed this sister’s impetus to stake a claim on what she saw as her inheritance.

According to Catherine, now newly reinstated as Mama Nyambura’s friend, the ‘case’ had been brought not out of the sister’s desire for justice but from a place of jealousy. Catherine, usually one to laugh at the misfortune of others, was appalled that Mama Nyambura had been reduced to calling at her house in a state of tears because of her sister’s threats. Catherine saw them as brought about by jealousy (wivu) latent in the distinction between Mama Nyambura’s stone house and her sister’s corrugated iron dwelling where she lived with her husband. ‘Ako na nyumba ya mabati, lazima ukuwe na wivu!’, Catherine told me – ‘She has a house made of corrugated iron, of course you’d be jealous!’

However, it was also wa Mukina’s alleged pernicious attitude that incensed Catherine, provoking her to wax lyrical at home about Mama Nyambura’s misfortune. As it turned out, the anticipated sub-division was likely to affect Mama Nyambura’s newly built rental accommodation, and possibly her own house. The sister was quoted by Catherine as saying that she wanted the rentals ‘torn down’, a statement taken to be a sign of wa Mukina’s jealousy of Mama Nyambura’s capacity to build.

The dispute turned upon Mama Nyambura’s lack of formal title deed for her homestead and her reliance upon the wishes of her father passed on by oral will. Her father had simply told her where to build her house. The title deed had remained in his name, even when she had begun to construct her plots. The informal nature of Mama Nyambura’s land tenure created the conditions for her sister wa Mukina to make a claim that the land ought to be re-divided amongst all siblings in the wake of her father’s death.

Catherine’s reflections on Mama Nyambura’s predicament are illuminating.

Us, we were alert. They’re the ones who refused to be alert to be given the inheritance … They relaxed. When they were given the land, that land, they should have taken the title deeds. At the time they were given the inheritance and they did nothing. They thought they’d arrived [i.e., the situation was fine, and no problems would arise]. Us, we were portioned [already, a long time ago]. And I told Mama Nyambura because you’re sitting on the shamba, request [from the government] the title deed. Ah! ‘It is not necessary’ [she said]. ‘My dad has said where to build the house.’ Title, it is very important! Now she’s running when things are what [i.e., the whole situation is chaotic]. And that’s why even wa Mukina can beat them. Now, if they had the title deed!Footnote 10

Catherine emphasised that Mama Nyambura’s father’s words were little help to her, and as we have seen, even to the extent that fathers plan for events after their death, inheritance disputes promise to rear their heads because of the possibility that not all siblings will play along.

A similar problem had beset Kimani’s family in 2019. Murigi was seen as already having had reasons to covet the land of his sister. When Gathee’s land was originally divided between Kimani and his siblings, they drew lots to see who would get which parcel of land. This was a crucial event, since some parcels of the land were far closer to the main road and would thus become more valuable and conducive to the construction of rental plots and roadside businesses. Kimani had drawn one such lot, and Murigi a lot that placed him further up the hill away from the road. Mwaura told me that when this took place, Murigi was far from happy with his lot.

Mwaura also speculated that what had provoked Murigi to deny his sister her land at the family homestead was her very status as a family member to begin with. Unlike Wangui or Gakuhĩ, Wangui and Wairimu, Kimani’s two eldest sisters had ‘arrived with Shosh’, as Mwaura put it. In other words, they were not Gathee’s daughters by blood, but had been incorporated into the family after Gathee and Leah Njoki had married in the 1950s. Nonetheless, Mwaura insisted his aunts were family, and always referred to them as such. ‘I mean, they have his names which means he took them as his.’ Murigi’s actions, Mwaura told me, suggested he had rejected their membership of the family. This appalled Mwaura.

Kimani and Mama Nyambura’s families argued that they were upholding a more fundamental standard of moral behaviour – the commitment to kinship itself – that the other parties had threatened. Catherine, who had been badly ill with a chest infection during 2018 before eventually recovering in hospital, put her own spin on the situation, one informed not only by her own brush with mortality but by the recent death due to cancer of Joyce Laboso, the governor of Bomet County, at the age of fifty-eight. We had been watching the burial broadcast on television together earlier that day, prompting her further reflection. ‘When you die you leave all these things behind, shamba, what what [i.e., ‘this and that’]. See Laboso has left everything. Land is not important.’ In this respect, Catherine suggested that the dispute was not merely over Wangeci’s right to land pitted against that of Murigi’s, but about a broader moral question of fairness, of how the family ought to provision its most vulnerable kin members with land at the patrilineal homestead.

Kimani’s defence of Wangeci’s interests viewed alongside Mama Nyambura, and her family’s defence of their right to control their fathers’ assets, directs us to consider the role of consensus-making in the apportioning of land after the death of a parent or senior kin member. In the ‘sitting’ that takes place after burials, Elizabeth Cooper (Reference Cooper2012) has described the way Luo families in western Kenya resolve conflicts and actualise unity as a characteristic of kin relations. But in a Kiambu defined by land poverty, and amongst siblings whose lands verge on each other, inheritance disputes (aided by the legal change that has given women equal power to inherit) implicate siblings as agents who have the capacity to fracture social relationships simply by pursuing their own interests. The situation of inheritance becomes such a high-stakes one that even the voicing of claims is viewed as problematic. They are seen as acts of self-interest that have to be headed off. This is a context wherein the balance of harmony is easily tipped.

It is here that we observe the fragility of patrilineal authority in making provision for inheritance. In general, agreements between kin about inheritance rarely outlast the lifetime of parents who fix these agreements in place with their authority. Oral wills are ambiguous. They are treated as such under Kenyan law, where they require two witnesses and are only valid if the testator dies within three months of it having been made, in order to avoid the danger of details being forgotten or misreported over a longer period (National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General 2012). In Kimani’s case, when his father Gathee died in 1984, Wangeci was married and residing in Chungwa. No provision was made for her, and his death pre-dated the de facto introduction of the Land Succession Act in the mid-1980s (cf. Maas Reference Maas1986: 17). At that point, all of Kimani’s sisters were married and residing elsewhere, save for Wangui, the youngest, who continued living in her mother’s house. Nothing in his family had been revised since. But by the time Kimani’s mother Leah Njoki died, she had become senile and was unable to make a will, oral or otherwise. It fell to Kimani and his elder brother Gakuru to intervene on Wangeci’s behalf and apportion her land at her father’s homestead. Kimani’s insistence on Wangeci inheriting land was thus something of a novelty for the family – a sister who had married elsewhere returning to claim inheritance. If Murigi contested Wangeci’s capacity to inherit, he did so because it did not appear so much as his father’s wish, but rather Kimani’s. Why should his brother deprive him of land he otherwise would have used?

If Kimani’s case reveals the difficulties of creating consensus between siblings where no higher authority is recognised, then the changing events of Mama Nyambura’s case also show us the fragility of patriarchal instruction on who should be apportioned what land once they have died. The weakness of patriarchal authority, and its incapacity to contain distinct interests, can be underscored via comparison with other forms of customary authority. Consider, for instance, Max Gluckman’s (Reference Gluckman1965) writing on Barotse (Lozi) judges as they attempted to resolve disputes between kin in what is today western Zambia. Gluckman’s wider project was to explore how Lozi judges used notions of customary obligation and conduct in a rather flexible way to gauge the conduct of persons disputing cases in court. Gluckman wrote about a particular dispute in which members of a family had quarrelled, and two men had had their gardens seized by a cousin. In resolving the case, Gluckman showed how judges appealed to ‘ultimate values’ and ‘norms’ characteristic of how the social relationships between the parties in question ought to be – that children and cousins ought to love and help their parents, for instance, and each other – iterating these norms to those involved (Gluckman Reference Gluckman1965: 49). Gluckman described the success of the judges in this case. ‘Nine years later I heard by letter that these disputants were living in amity’ (Gluckman Reference Gluckman1965).

In central Kenya, few trusted authorities could mete out justice of this sort, in a way that could permanently resolve or fix social relationships, particularly where land was concerned. As it happens, claims proved easier to resolve than relationships. Mama Nyambura was ultimately forced to pay money to the local chief to support her dispute against wa Mukina. But the dispute was finally resolved by a contingent revelation. Wa Mukina had, it turned out, been given 1 million KSh by her father as a loan. Wa Mukina had her debts cancelled, in exchange for dropping her ‘case’ against Mama Nyambura. None of this resolved the financial damage and stress the case had caused for Mama Nyambura, nor did it heal her relationship with her sister.

Even where consensus was achieved, situated interests continued to simmer below the surface. Consider, for instance, how the dispute amongst Kimani’s siblings ended. Eventually, Kimani’s eldest sister, Wairimu, condemned Murigi and Gakuhĩ’s actions. Mwaura explained to me, after my return to Cambridge, how Wairimu had died in 2020 feeling ‘very bitter’ about their attempt to deprive Wangeci of her land, and to throw Paul Kimani out of his temporary residence. Her death, amidst those bitter feelings, had apparently led to the end of the dispute, and Wangeci was continuing to build her house in 2020. ‘Things have been quiet since’, was how Mwaura described the situation. Their interest in Wangeci’s land had not gone anywhere, merely its outward expression.

The challenge Kiambu inheritors face, to follow Jane Guyer (Reference Guyer2004: 155), is thus to ‘fix’ land claims when inheritance creates uncertainty about them. Where local consensus could be made, wider processes stood to interrupt and disturb it – not least the growing value of inherited land due to Nairobi’s expansion. Local authorities were viewed as subject to manipulation and ‘corruption’, offering little in the way of reconciliation. But some avenues towards fixing land were seen as more durable than others.

Title was viewed as the ultimate answer, even if faith in this may be misplaced in the long run due to the widespread practice in Kenya of grabbing land through manipulating documents.Footnote 11 For Catherine, the achievement of a mutually agreed enclosure was at least preferable to tenurial ambiguity. She was not alone. ‘Better the surveyor come’, Feye had once told me when I asked her what would happen to her family’s land in the future. Throughout my fieldwork, her family had kept a communal field and clustered their dwellings together. The land had not been formally sub-divided between families. Splitting land under the auspices of the state was the preferable means of coming to a fair conclusion to the rivalries over land that threatened to tear families asunder.

The formalisation afforded by legal texts, writes Jane Guyer (Reference Guyer2004: 155), creates ‘a permanent reduction to a particular system logic’ rather than a more ambiguous ‘performative moment to be re-created at every transaction’. It offers the semblance of legal permanence where before there was none. But as Guyer notes, the history of formality in African states has been an ambiguous and piecemeal one. ‘Formality is experienced by the population in its plural and concrete forms, as “papers”; rather than as an enduring generalizable principle’ (Guyer Reference Guyer2004: 158; cf. Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson1996: 285–8). Guyer’s words capture Catherine’s emphasis on ‘title’ not simply as a legal document, but as a ward against relatives who might seek to covet one’s own land, were it held informally. It evokes what Maxim Bolt (Reference Bolt2021) has called ‘fluctuating formality’ in the context of South Africa, where the efficacy of documents is to be found not necessarily in the realm of law but in their deployment in everyday life and social process, functioning as ‘stabilizing rituals and scripts that maintain the impression of a coherent and distinct formal register’ (990). Such desires for formality evince the promise of stability title deeds are seen to entail, their symbolic life rather than their official role.

In Kiambu, the pursuit of these documents dovetails with other ‘informal’ modes of enclosing land, especially those that involve displays of power and tacit compromises that can hardly said to be ‘customary’ in nature since they play out in the process of everyday life and are not fixed in formal terms but produced by contingency. As we saw earlier, Mũrukaru abandoned his claim and accepted defeat. There was no judicial resolution – formal or informal – simply a glum recognition on his part that he could acquire neither the documents he wanted nor the power within the family he believed he ought to possess.

Pursuing title deeds, however, required ‘alertness’ to the possibility of disputes manifesting ahead of time, the knowledge that they were likelier than not. Catherine contrasted her savviness with Mama Nyambura’s naïve reliance on her father’s words of instruction on where to build her home. For Catherine, title deeds were utterly necessary fixes to the problem of competing claims on land between kin, the solution to ambiguity created by an informal or customary tenurial system made through transient words and claims.

Anticipating Future Dispute

As will be clear by now, in my hosts’ household, the debacle surrounding Mama Nyambura’s inheritance had provoked their own reflections on the problem of inheritance. At home one evening, Mwaura had asked his mother why land was fought over in such a manner. ‘Hey! Lands are not a joke!’, Catherine responded (Weee! Mĩgũnda ndĩrĩ itherũ). Mwaura then began to complain in a half-joking style about the land his father had allocated his sister Njoki. ‘Do you hear the place she’s been allocated? That land is huge like a dog!’ (nĩ ũraigua nginya harĩa aragaĩrwo. Mũgũnda ũcio ũkĩrĩ mũnene ta ngui), he told his mother in an alarmist tone. Responding bluntly, Catherine told Mwaura that he had been told ‘nicely’ (wega) what land he would inherit. In other words, he should not try and push his luck. Their conversation soon began to shift, towards a discussion of where Njoki’s land would ‘reach’ (gũkinya) in her absence. Mwaura’s father Kimani had already shown him where he should ‘build’, and in his view, Njoki’s portion was far too large. Telling his mother precisely what area Njoki’s land encompassed, Mwaura annoyedly announced the unfairness he saw in the situation. ‘The whole land! It’s like the Devil’ (Mũgũnda ũcio wothe. Nĩ ta ngoma). Catherine told Mwaura to stop with his ‘devil talk’, maintaining a defence of Njoki that had stopped sounding like joking by this point. ‘I’m the eldest’ (Atĩ na nĩ niĩ mũkũrũ), said Mwaura. ‘It’s a must that we revisit [the matter of inheritance]’ (Hau no nginya tũkarevist).

It was at this point that I began to wonder whether Mwaura was doing what I had come to know was characteristic of him – exaggerating a state of alarm or despondency to make a point.

And the way Njoki loves money! I know she can give it away! She has no brains.Footnote 12

Rather unlike Wangeci, a Kikuyu farming woman in her middle age, Mwaura wondered if Njoki embodied precisely the sort of new mobile Kikuyu womanhood evoked by the ‘slay queen’ epithet that we observed in Chapter 5. Mwaura sensed the danger this would pose, that Njoki would expropriate the land in order to live the lifestyle of someone who had ‘made it’. It was imperative to secure as much land in his own name as possible.

However, despite his extreme language, Catherine had begun laughing at her son’s frustrations, seeing them as precisely that, rather than intentions to encroach upon Njoki’s land. Mwaura was recalling a time in which his father had been ill and become ‘serious’ about the need to allocate land to his children, to pre-empt conflict before his death. Catherine continued to laugh, but Mwaura was bullish:

God! It’s a waste! How do you think she does her calculation? That land is big like that. She’ll get married. You and Dad I’ll lock you inside here. The rest, I’ll have a field day.Footnote 13

Mwaura imagined a day in which his mother would be elderly and his sister powerless, and he would be able ‘to really enjoy himself’ (kũĩgang’ara). The land would be his to monetise in the way he imagined in our conversations – building real estate that would facilitate a better life, one far removed from the one in which he was when he spoke. The rains of 2018 had badly affected his mother’s health, and the availability of work for his father. The wooden home in which the family dwelt was regularly flooding with the heavy rains due to its location at the bottom of a slope. Moreover, his university education was in jeopardy, and it looked as though he might have to finish his studies at a later date if his father’s wages failed to transpire. His words trailed off as he wished his family had money so that they could have bought some of the land being sold in the local area.

Conclusion

In Peter Geschiere’s Witchcraft, Intimacy, and Trust (Reference Geschiere2013), a central tenet is that witchcraft accusations can emerge from within the household. Witchcraft suspicions and accusations are the ‘other side’ of the intimacy that prevails within families and extended families across African contexts. Geschiere illustrates how the extension of families across space and the diverse fortunes of social mobility (upward and downward) within these families have stretched social relations, fomenting tensions over limited resources and expectations of ‘just distribution’ within them. While poorer relations make claims on wealthier kin’s earnings, the wealthy withdraw, enclosing themselves in fine houses that may well exist in the very same villages as their low-earning relations.

This chapter has illuminated a very different way in which social tensions emerge from within the family, as a result not only of the ‘stretching’ of kin relations across space and economic distance, but also the combination of such stratification with the pressure-cooker-like status of family land. Family members dwell together on dwindling plots that, at the very same time, skyrocket in value, causing intense competition when their ownership becomes ambiguous. Kiambu’s history of titling has not been consistently followed in subsequent generations. That even successful figures like Mama Nyambura were residing on their land ‘informally’ throws into relief the complexities of ownership that persist in Kiambu, and which burst into conflict as the urban frontier approaches and ‘ancestral’ family land accrues value.

The narratives of envy and ill-intent through which these conflicts are lived obscures their colonial roots – the history of expropriation and land reform (Chapter 1) that has transformed the region into one of workers with plots, struggling amongst each other to hold on to inherited wealth. As plots dwindle to 50 × 100 metres, or 50 × 50 metres in some cases in Ituura, it is no wonder that men like Mũrukaru and Mwaura worry about the consequences of women’s inheritance for their futures. Even a more successful senior man like Murigi clearly worried about the loss of farmland that would result from incorporating women. Contemplating grim economic futures in Kiambu informed these disputes and their very anticipation. Years ahead of inheriting land for himself, Mwaura anticipated his sister’s intentions. Unsure of them, speculating they were against his own by dint of her being a woman, he already thought about enclosing as much family land for himself. As we have seen throughout this book, men were highly aware of their precarity, a recognition that undoubtedly shaped their anxieties over family land and property, as well as their attempts to accrue as much of it as possible at inheritance, sometimes violently and at the direct expense of their sisters.

This ‘politics’ of intimate exclusion is, as Catherine Boone (Reference Boone2014) has put it, a ‘sub-politics’ – a micro-politics of contestation taking place against the backdrop of colonial legacies of land tenure reform and more recent processes of land’s commodification. As Theodor Zidaru-Bărbulescu (Reference Zidaru-Bărbulescu2019) has put it, this is a politics driven by ‘forms of authority, domination and contestation with a quotidian space of collective habitation’, one where notions of greed and desires injurious to others are attached to those deemed to disturb harmonious family relations, requiring urgent resolution and containment. Such ‘ugly emotions’ (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Mehtta, Bresciani and Strange2019) were viewed as justification for strategies designed to curtail the rights of others within land conflicts, part of an intimate politics of ‘winners and losers’ playing out over the immensely valuable, though small, chunks of land held within Kiambu families. The consequence is not only the mutual alienation of family members, but deeper stratification as certain family members are excluded from patrilineal property. As this chapter has shown, rather unusually for central Kenya’s history, economically successful women have been able to cement their status as rooted landowners in patrilineal neighbourhoods, though hardly with ease and, as we have seen, at great financial and emotional cost. Mama Nyambura’s land claims were viewed as legitimate by Catherine and Mwaura precisely because of her economic success, the cause of the ‘jealous’ claims put forward by her brother and sister respectively.

There is, however, another dimension to these family conflicts that I have not discussed in this chapter but which I mentioned in Chapter 5, one which is a consistent source of debate in Kenya: when landowning men remarry after widowerhood or divorce and have children from two distinct marriages. Tensions regularly arise, especially between children from the first marriage and the new stepmother, and anxieties over inheritance flare up if the former feel their father has been preyed upon by a ‘slay queen’, keen to have a child and seize inheritance through the logic of descent. Until November 2021, Kenya’s constitution allowed women to claim men’s land through their children, including those born out of wedlock. Uhuru Kenyatta’s Law of Succession Amendment spoke to these anxieties, narrowing inheritance to legally recognised wives (The East African 2021). As one newspaper put it, ‘The law further slams the brakes on secret partners who have a penchant for popping up when a person dies to demand recognition and a share of the departed person’s property.’

However, anxieties over land caused by extra-marital affairs have not disappeared. Neither have feelings that the immense value of land itself will animate all sorts of chicanery in order to claim it, especially by untrusted and unknown relations. In this regard, this chapter sets the scene for the closing one, where we see how Catherine’s death and Kimani’s remarriage left Mwaura anxious and alone at home, wondering about his future and whether it might lie elsewhere.