Introduction

Loiasis, also known as African eye worm, is a disease caused by infection with the filarial worm Loa loa. It is endemic in Central Africa, particularly in forested areas that provide natural habitats for its primary vectors, Chrysops dimidiata and Chrysops silacea. Humans become infected through the bite of day-biting Chrysops, which inoculates infective third-stage larvae (L3) into the subcutaneous tissues (Whittaker et al., Reference Whittaker, Walker, Pion, Chesnais, Boussinesq and Basáñez2018). These L3 subsequently develop into fourth-stage larvae and then adult worms. Once inseminated, females produce millions of microfilariae that migrate into the peripheral blood.

In experimental studies on animals injected with specific doses of filarial infective larvae, the microfilarial density is generally assumed to be proportional to the number of adult worms (Ansari, Reference Ansari1964; Abraham, Reference Abraham1985; McKenzie and Starks, Reference McKenzie and Starks2008). In humans, however, the relationship between adult worm burden and microfilaraemia remains unclear. Some L. loa-infected individuals, although presenting ocular passage of adult worms, have few or no detectable microfilariae in the peripheral blood (Dupont et al., Reference Dupont, Zue-n’dong and Pinder1988; Bouyou Akotet et al., Reference Bouyou Akotet, Owono-Medang, Mawili-Mboumba, Moussavou-Boussougou, Nzenze Afène, Kendjo and Kombila2016). This observation raises the question of whether such cases correspond to infection with a single fecund female worm. To date, no reports have shown whether L. loa infections are mono- or polyparasitic. The ‘worm burden’ i.e. the number of adult parasites present in the host, has recently been documented for other human filarial species, such as Onchocerca volvulus, Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi, and these studies suggest high levels of polyinfection (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Sands, Opoku, Debrah, Batsa, Pfarr, Klarmann-Schulz, Hoerauf, Specht, Scandale, Ranford-Cartwright and Lamberton2023; Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Fischer, Méité, Koudou, Fischer and Mitreva2024; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Choi, Fischer, Hedtke, Kode, Opoku, Gankpala, Ukety, Mande, Anderson, Grant, Fischer and Mitreva2025).

In loiasis, direct estimation of adult worm burden is challenging because the adult stage of L. loa resides in deeper subcutaneous tissues. By contrast, microfilariae circulating in the blood are more accessible, and genetic information contained in the offspring’s DNA can be used for parentage analysis (Neves et al., Reference Neves, Webster and Walker2019; Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Sands, Opoku, Debrah, Batsa, Pfarr, Klarmann-Schulz, Hoerauf, Specht, Scandale, Ranford-Cartwright and Lamberton2023; Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Fischer, Méité, Koudou, Fischer and Mitreva2024). In nearly all eukaryotes, including filarial nematodes, the mitochondrial genome of offspring is inherited only from the female parent (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Chilton and Gasser2004). Consequently, microfilariae originating from the same female parent have identical or near-identical mitochondrial genomes and are considered as maternal siblings (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Sands, Opoku, Debrah, Batsa, Pfarr, Klarmann-Schulz, Hoerauf, Specht, Scandale, Ranford-Cartwright and Lamberton2023). Parentage analysis based on mitochondrial microfilariae DNA has often been used to estimate the number of fecund adult females in filarial worms (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Sands, Opoku, Debrah, Batsa, Pfarr, Klarmann-Schulz, Hoerauf, Specht, Scandale, Ranford-Cartwright and Lamberton2023; Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Fischer, Méité, Koudou, Fischer and Mitreva2024).

In this context, the present study aims to determine whether individuals with loiasis were infected with one or more reproducing female parasites. To achieve this goal, we analysed mitochondrial polymorphism in the genome of a pool of L. loa microfilariae offspring to estimate the female parent burden in the host. The potential limitations of this analytical approach were also discussed.

Materials and methods

Samples origin

Dried thick blood smears and venous blood samples were collected during two different previous studies (Kamgno et al., Reference Kamgno, Pion, Chesnais, Bakalar, D’Ambrosio, Mackenzie, Nana-Djeunga, Gounoue-Kamkumo, Njitchouang, Nwane, Tchatchueng-Mbouga, Wanji, Stolk, Fletcher, Klion, Nutman and Boussinesq2017; Campillo et al., Reference Campillo, Pakat-Pambou, Sahm, Pion, Hemilembolo, Lebredonchel, Boussinesq, Missamou and Chesnais2025), and these samples were used to measure the microfilarial density in the blood of individuals with loiasis. In 2015, Giemsa-stained blood smears were prepared using 50 µL of blood collected by finger prick from individuals living in the Okola Health District, Cameroon, as part of a 'Test-and-not-treat' project designed to identify individuals with high L. loa microfilaraemia before onchocerciasis treatment with ivermectin (Kamgno et al., Reference Kamgno, Pion, Chesnais, Bakalar, D’Ambrosio, Mackenzie, Nana-Djeunga, Gounoue-Kamkumo, Njitchouang, Nwane, Tchatchueng-Mbouga, Wanji, Stolk, Fletcher, Klion, Nutman and Boussinesq2017). Dried blood smears from 12 subjects have been stored at room temperature since collection and used for the present study. In 2021, dried blood smears and venous blood samples were collected from individuals living in villages near Sibiti, in the Republic of Congo, as part of the 'MorLo' project (Campillo et al., Reference Campillo, Hemilembolo, Pion, Lebredonchel, Dupasquier, Boullé, Rancé, Boussinesq, Missamou and Chesnais2023). The latter samples, including one tube of venous blood stored at −20°C from one individual and dried blood smears from three others, were tested for the present study.

Study design

Microfilariae were collected from dried blood smears and venous blood samples. An initial step focused on optimizing DNA extraction from the archived dried blood smears collected from 12 different subjects during the 'Test-and-not-treat' project, to maximize DNA yield. Subsequently, the protocol was optimized to reduce human host contamination and enrich parasites in the samples collected during the 'MorLo' project, using 3 and 5 µm pore size microfilters. DNA was sequenced and raw reads were analysed to determine the Loa parasite/human ratio after DNA extraction optimization and microfilariae L. loa enrichment.

The second step consisted of analysing sequence polymorphisms in the mitochondrial genome. We hypothesized that the individuals were infected with more than one fertile female when polymorphic Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) were detected in the mitochondrial DNA of a pool of microfilariae from the same individual. Polymorphic SNPs were assigned as a specific position in the genome that showed the presence of two or more different nucleotides, indicating a multiallelic variation (e.g. A/C/T). Lastly, we estimated the number of mitochondrial haplotypes for six loci to determine the minimum number of female parent worms present in the host.

Protocol optimization of DNA extraction from dried blood smears

Dried blood smears were scraped off the slides with a sterile scalpel and transferred into Eppendorf DNA LoBind tubes containing a lysis buffer. Two protocols were performed to evaluate DNA extraction efficiencies.

The first approach used the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit protocol (catalog number 69504). The scraped material was lysed in 180 μL of ATL buffer and 20 μL of proteinase K (Qiagen), and incubated at 56°C for 1 h, with gentle agitation at 300 rpm. A second incubation was performed at 56°C for 10 min, after adding 300 µL of buffer AL. Then, 150 µL of ethanol 100% was introduced and the mixture was put in a silica-membrane spin column that was centrifuged for 1 min at 8000 rpm. Column membranes were successively washed with 500 μL of buffer AW1 then AW2, followed by a centrifugation step, respectively, for 1 min and 3 min at 14 000 rpm. DNA was eluted with 200 μL of buffer AE Qiagen solution and stored at −20°C.

The second method consisted of extracting DNA using a chloroform-isoamyl based method often used in DNA extraction from dried blood smears (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Poljak and Seme1998; Bisht et al., Reference Bisht, Hoti, Thangadurai and Das2006). The scraped material was digested in 1 mL of lysis buffer composed of 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH = 8), 100 mm NaCl, 20 mm EDTA, proteinase K (2 mg/mL), SDS (1%), 1 m DTT and H2O (RNase/DNase free) up to the desired volume, and incubated at 56°C during 2 h and 30 min. One volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (1:1) was added for DNA purification and the mixture was centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 20 min at 15°C. Supernatant was transferred to a new tube and incubation was performed at room temperature for 1 h, after adding 5 µL of RNase A (Macherey-Nagel). After that, DNA was precipitated in 0.6 volume of cold isopropanol and 0.1 volume of sodium acetate (3 m pH = 5), and centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatant was removed and DNA precipitate was washed with 1 mL of ethanol 70%, followed by centrifugation at 10 000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. This washing step was repeated a second time. After centrifugation, DNA pellet was air dried at room temperature and resuspended with 50 μL of Tris-EDTA buffer, and stored at −20°C before use.

Concentration of extracted DNA was measured with a Qubit Flex Fluorometer using the 1x dsDNA HS assay kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, France) and the purity was assessed with spectrophotometric measurement using a Nanodrop One (Thermo Fisher Scientific, France), for estimating the A260/A280 and A260/A230 absorbance ratios. DNA yield was compared to determine the most efficient method. To assess the proportion of parasitic DNA in the extracted samples, a test-sequencing run on an Illumina HiSeq-1000 platform (PE 2 × 150 bp) was performed by Novogene Europe (Cambridge, UK) (see below for details of library preparation), and we then estimated the percentage of parasite reads mapped to the L. loa reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_039623295.1/).

Protocol optimization to minimize human contamination using different pore size microfilters

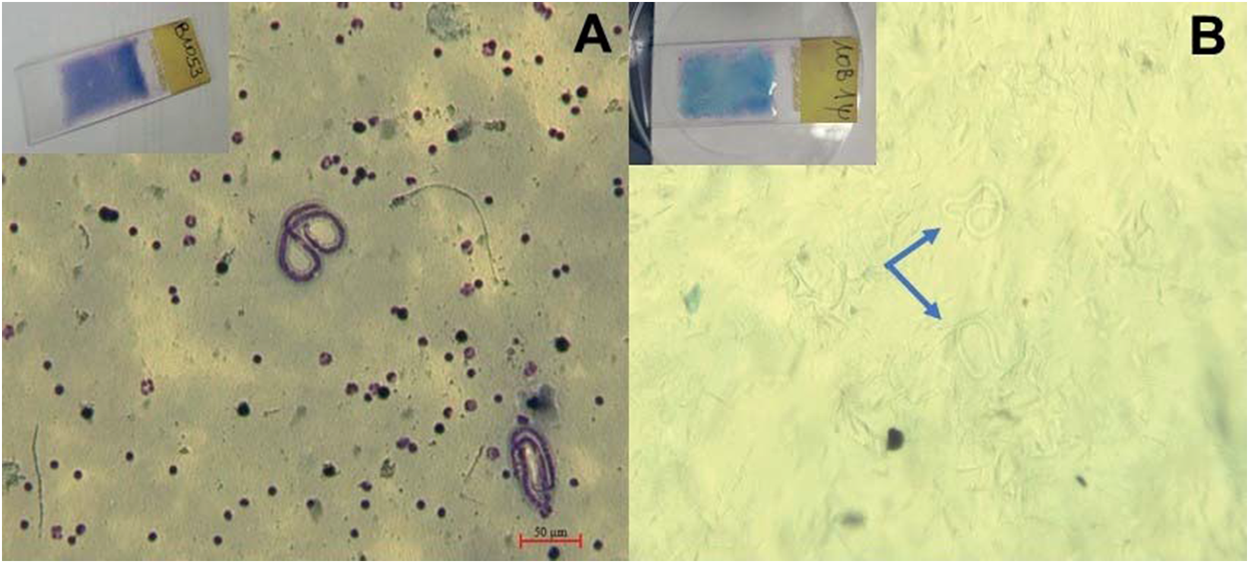

Filtration of microfilariae from dried blood smears requires dissolution of the blood film, and we adapted for that purpose a method previously used on W. bancrofti (Bisht et al., Reference Bisht, Hoti, Thangadurai and Das2006). Stained smear slides (Figure 1A) were covered with 500 μL of lysis buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH = 8), 100 mm NaCl, 20 mm EDTA, proteinase K (2 mg/mL), SDS (1%) and H2O (RNase/DNase free)], and heated at 56°C for 6 min while gently mixed. Once the blood film was completely dissolved (Figure 1B), the solution was filtered through microfilters. Microfilters with pore sizes of 3 and 5 µm (Pluriselect, Germany) were tested on two different samples to determine the most effective for parasite enrichment. This was followed by washing steps with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) to remove the remaining human cells and debris. Filters were immediately cut and placed into tubes containing Qiagen ATL lysis buffer and proteinase K, for DNA extraction with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (catalog number 69504, Qiagen). Unfiltered samples were treated and used as controls.

Figure 1. Observation of L. loa microfilariae on May-Grünwald Giemsa stained smear (A) and after dissolution of the blood film (B) under light microscope Zeiss Axio Zoom v.16 (magnification × 100).

A total of 500 µL of venous blood was diluted with 500 µL of PBS and the same method as described above was performed for filtration of 100 µL of blood to isolate microfilariae.

Extracted DNA concentrations were too low to be accurately measured with Qubit and Nanodrop measurements. Thus, we performed real-time PCR targeting LLMF72 (62 bp) (Fink et al., Reference Fink, Kamgno and Nutman2011) and β-actine (171 bp) (Fotso Fotso et al., Reference Fotso Fotso, Angelakis, Mouffok, Drancourt and Raoult2015) genes, respectively, for relative quantification of L. loa DNA versus human DNA. Volume of the mixture was 20 μL and composed of: 10 μL of 2x Master Mix using Luna Universal Probe for Loa-qPCR and QuantiTect Probe for human-qPCR; 0.4 μm of each reverse and forward primers; 0.2 μm Probe and 8 μL of extracted DNA. Amplification conditions steps were as follows: an activation step (95°C for 60 sec) was followed by 45 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15 sec) and an extension step (60°C for 45 sec). PCR thermal cycling was terminated by a final extension step (37°C for 30 sec).

DNA extracts were also sequenced using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) to confirm the real-time PCR results. Forty µL of the DNA input, ranging from < 0.05 to 1 ng/µL, were added in 10 µL of TE 1x (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA), and sheared with the Bioruptor Pico (dried blood smears: 3 cycles of 30 sec on/30 sec off; venous blood: 6 cycles of 30 sec on/30 sec off). Library preparations were conducted following the manufacturer’s protocol using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Prep kit (E7645, New England Biolabs). The libraries were quantified with the Qubit Flex Fluorometer, and the post-shearing pattern was assessed using the Qiaxcel system to check that fragment sizes were within the expected range, i.e. between 150 and 350 bp. Indexed libraries were paired-end sequenced using the Illumina iSeq-100 platform (2× 150 bp). Additional sequencing was performed by Novogene Europe (Cambridge, UK) on the Illumina HiSeq-1000 platform (PE 2 × 150 bp), to analyse mitochondrial genomes from dried blood smears and venous blood samples that had the highest Loa DNA/human DNA ratios.

Performance of microfilters in microfilariae L. loa enrichment was evaluated based on Ct value in real-time PCR and proportion of reads mapped.

Bioinformatic analysis of DNA sequences

Qualities of the raw and cleaned sequencing reads obtained from the Illumina platform were evaluated using fastqc software v.0.11.9 (Andrews, Reference Andrews2010). Adaptor sequences, reads containing residual sequencing errors, e.g. poly-G tails, short and low-quality reads, were trimmed or removed with fastp v.0.20.1 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Chen and Gu2018) and cutadapt v.3.1, considering a minimum Qphred quality score of 30 and a minimum size of 50 bp (Martin, Reference Martin2011). The resulting cleaned reads were paired using a custom Perl script and aligned to the L. loa reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_039623295.1/) using bwa-mem2 v.2.2.1 (Vasimuddin et al., Reference Vasimuddin, Misra, Li and Aluru2019) with default conditions. The alignment files were then sorted and indexed with samtools v.1.10 (Danecek et al., Reference Danecek, Bonfield, Liddle, Marshall, Ohan, Pollard, Whitwham, Keane, McCarthy, Davies and Li2021), and filtered to retain only properly mapped in-pair reads. SNPs were called with bcftools v.1.9 using the 'multiallelic' option (-m option; Danecek et al., Reference Danecek, Bonfield, Liddle, Marshall, Ohan, Pollard, Whitwham, Keane, McCarthy, Davies and Li2021). A range of quality filters was applied to ensure high-confidence variant calls, including quality of variant (QUAL ≥ 120), mapping quality (MQ ≥ 50) and genotype depth of coverage (DP ≥ 60). These filters were applied based on the value of the transition/tranversion (TS/TV) ratio, with an ideal value of at least 2 (Purvis and Bromham, Reference Purvis and Bromham1997; Aloqalaa et al., Reference Aloqalaa, Kowalski, Błażej, Wnetrzak, Mackiewicz and Mackiewicz2019) to reduce false positives i.e. potential artifacts. Only variants located on the mitochondrial genome were further analysed with bcftools view to extract the total number of SNPs (all detailed commands are available in the supplementary material).

Estimation of mitochondrial haplotypes

Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files containing properly sequenced reads aligned to the mitochondrial reference genome were manually inspected using Tablet software v.1.21.02.08 (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Stephen, Bayer, Cock, Pritchard, Cardle, Shaw and Marshall2013). We targeted six polymorphic regions (150 bp), each located in a different gene, namely: NADH dehydrogenase 2 (ND2), cytochrome oxidase 1 (cox1), cytochrome B (cytB), ND1, cox2 and ND5, distributed throughout the 13 590 bp mitochondrial DNA. Sequences in the regions of interest were extracted using bedtools v.2.31.1 (Quinlan and Hall, Reference Quinlan and Hall2010), then repaired and paired-end reads (R1 and R2) were merged using flash v.1.2.11 (Magoc and Salzberg, Reference Magoc and Salzberg2011). The merged reads were mapped to the L. loa mitochondrial reference genome using bowtie2 v.2.5.4 (Langmead and Salzberg, Reference Langmead and Salzberg2012) in Geneious Prime v.2025.0.3 (https://www.geneious.com/). We then extracted an aligned region that was fully covered by reads without gaps, with a length ranging from 70 to 150 bp, depending on the sequencing depth. The number of haplotypes was determined using DnaSP software v.6.12.03 (Rozas et al., Reference Rozas, Ferrer-Mata, Sánchez-Delbarrio, Guirao-Rico, Librado, Ramos-Onsins and Sánchez-Gracia2017) by counting the number of reads differing by at least 2 SNPs. The number of haplotypes identified is referred to as the minimum number of reproductive females. Only haplotypes represented by at least two sequences were considered, whereas singletons that were found in one copy were excluded because they may be due to a sequencing error rather than indicating biological variation.

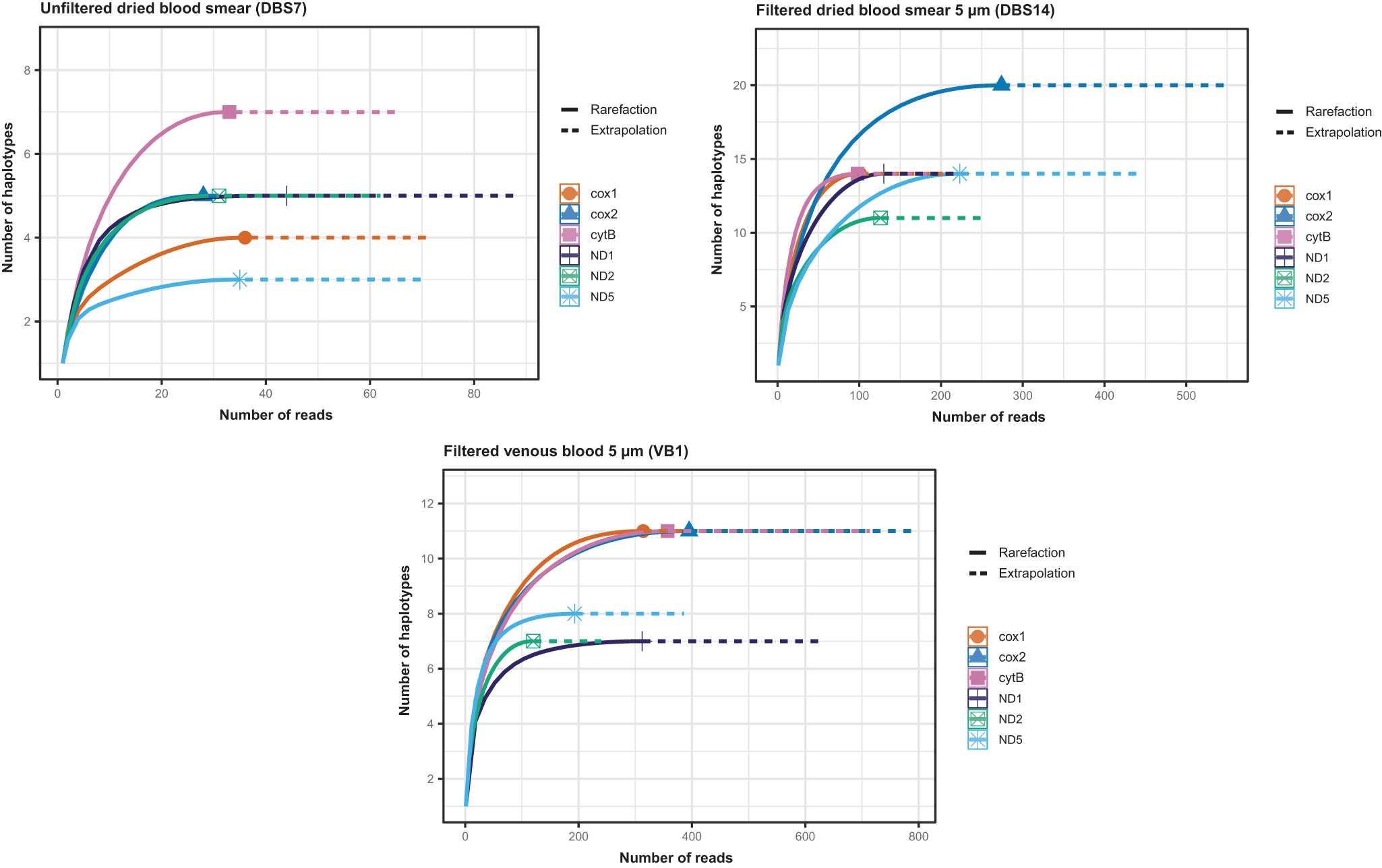

Statistical analysis

We compared the DNA yield obtained from the two extraction protocols using a Student’s t-test. Rarefaction curves were generated using the ‘iNEXT’ R package v.3.0.0 (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Ma and Chao2016) to assess if the estimated number of mitochondrial haplotypes depends on the sequencing depth of the microfilariae pool. Analyses were performed in R software v.4.4.0 (R Core Team, 2025).

Results

Protocol optimization of DNA extraction from dried blood smears

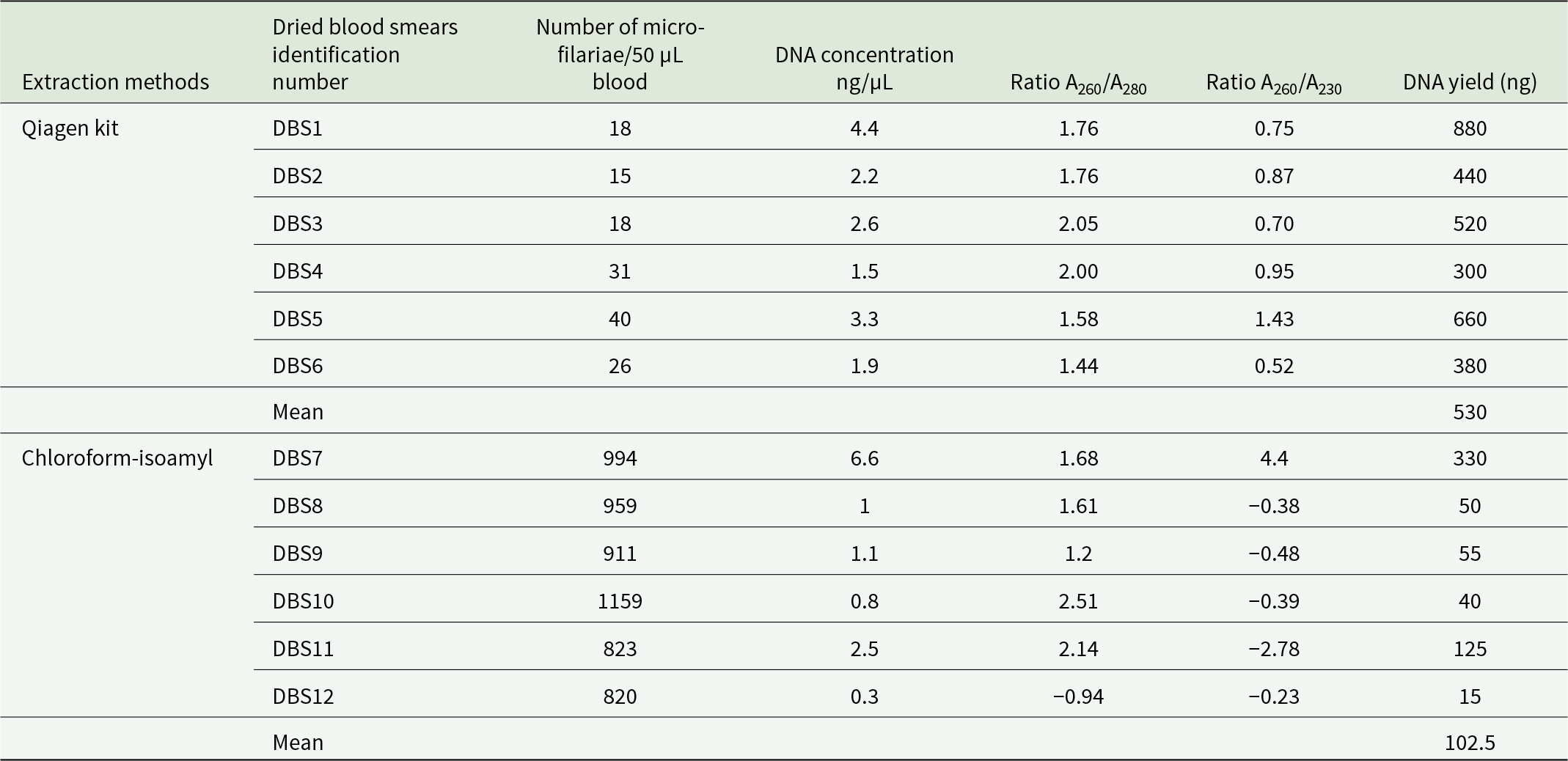

We extracted DNA from archived dried blood smears collected from 12 different individuals during the 'Test-and-not-treat' project conducted in 2015, using two different DNA extraction protocols. The first protocol followed the manufacturer’s instructions for the commercial Qiagen kit, and the second used the chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) approach. A significant difference in DNA yield was observed between the two extraction protocols (Student’s t-test: t = 4.33, P = 0.002). The method that yielded the best results in DNA extraction from archived dried blood smears (mean: 530 ng; SD = 211; Table 1) was the one using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen). The mean of DNA yield using the chloroform-isoamyl protocol was lower (102.5 ng; SD = 118; Table 1). Most of the DNA extracted from the different protocols showed low ratios at A260/A280 and A260/A230, indicating the presence of aromatic amino acid contaminants as well as organic contaminants or salts, respectively, making quantification based on absorbance unreliable.

Table 1. Comparison of yield and quality of DNA extracted from dried blood smears using two different protocols

As this was the first time that L. loa DNA had been sequenced from archived dried blood smears, we used a sample (DBS7) with a high concentration of DNA (>5 ng/µL) for successful sequencing. To ensure sufficient reads for analysis, we individually sequenced eight replicates, which represented separate library constructions from the same extracted DNA. Each replicate produced between 40 and 80 million raw reads, resulting in a total of 518 174 870 reads when merged. After removing low-quality reads and repairing, we retained 504 451 484 reads, of which 34.73% successfully mapped to the L. loa reference genome.

Protocol optimization to minimize human contamination using different pore size microfilters

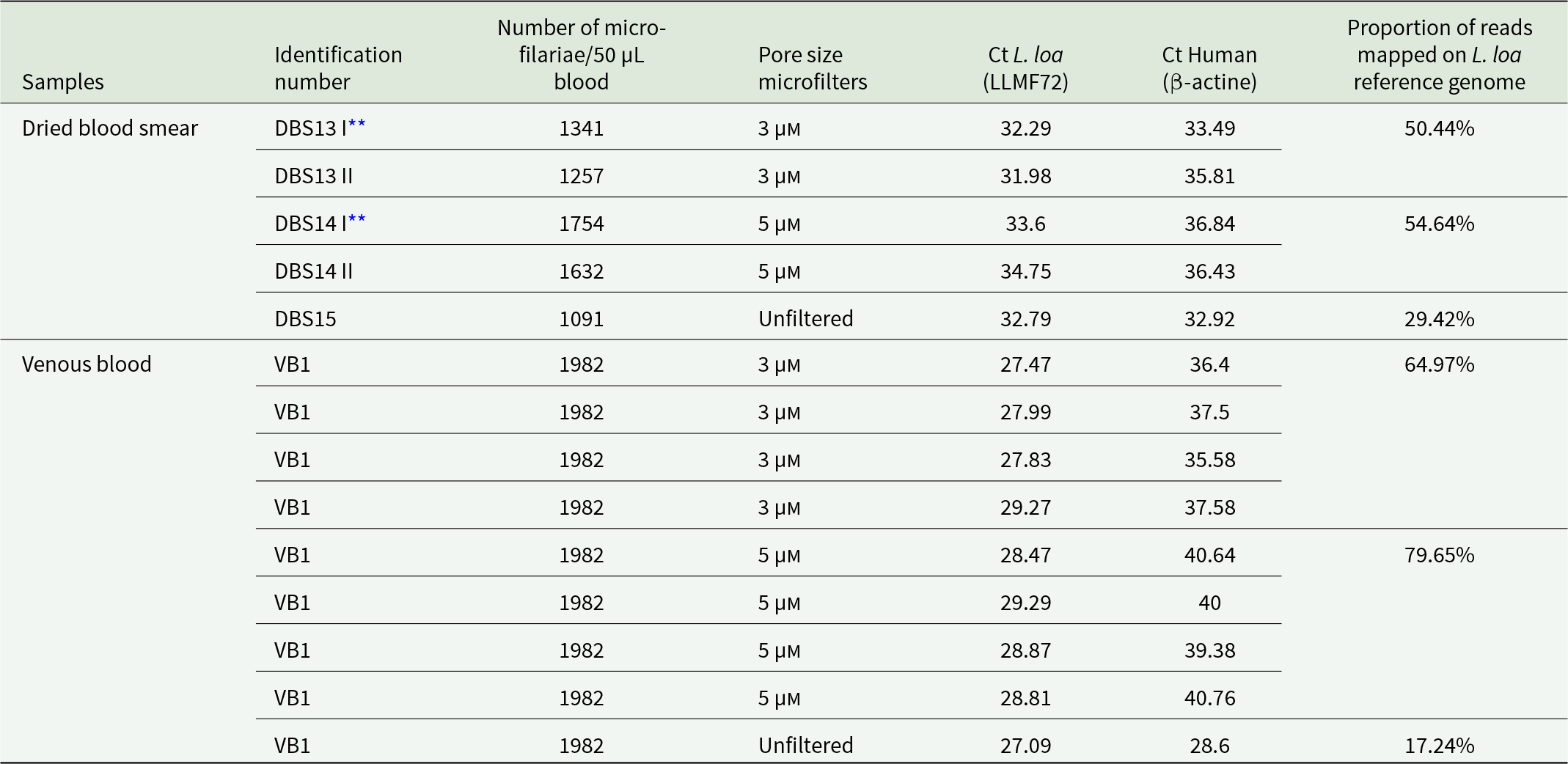

We tested the performance of 3 and 5 µm pore size microfilters using dried blood smears from three different subjects and venous blood from another individual. These samples were collected during the 'MorLo' project in 2021. When comparing the effect of different microfilter pore sizes using a qPCR targeting the β-actine gene, blood samples (dried blood smears and venous blood) filtered with 3 µm pores showed lower Ct values than those with 5 µm pores, indicating a higher presence of human host sequences (Table 2). Higher Ct values were found in samples filtered with 5 µm pores, suggesting reduction of human DNA and enrichment of L. loa parasites. Illumina sequencing results obtained from unfiltered samples using the iSeq-100 platform showed that 17.24% and 29.42% of reads mapped to the L. loa reference genome (Table 2). Although there were no replicates, a better mapping rate ranging from 54.64% to 79.65% was observed respectively when the slide elution and venous blood were filtered with 5 µm pore size microfilters, which is significantly higher than that obtained with unfiltered samples.

Table 2. Efficiency of microfilariae L. loa enrichment as a function of microfilter pore size

** DBS I and II means that the blood was collected twice from the same individual to make two different dried blood smears.

Analysis of polymorphism in the mitochondrial genome

We analysed raw reads from three samples sequenced on the HiSeq platform to obtain high-coverage genomic sequences, which enhance the reliability of identified variants. These samples included: a dried blood smear, initially sequenced to determine the Loa parasite/human ratio after DNA extraction optimization (DBS7), as well as an elution slide (DBS14) and venous blood (VB1) samples filtered with 5 µm microfilters, which showed L. loa parasite enrichment.

Identification of mitochondrial SNPs

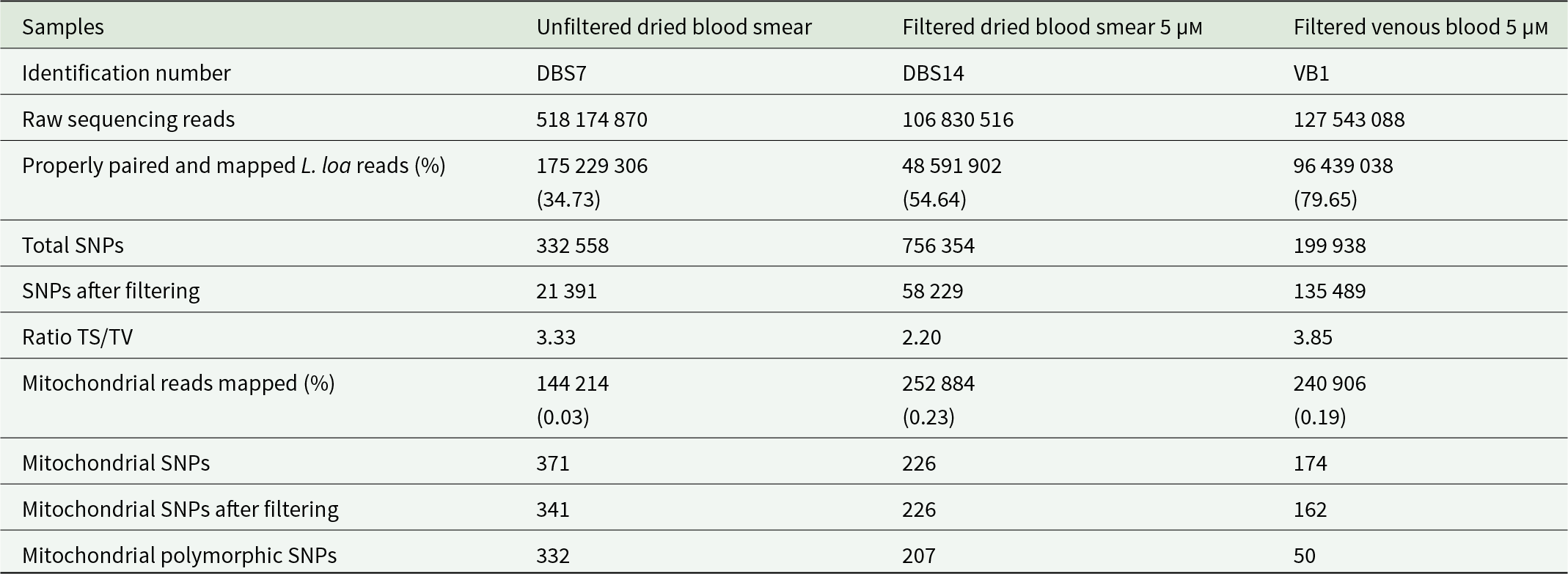

HiSeq sequencing produced 106, 127 and 518 million raw reads for filtered dried blood smear, filtered venous blood and unfiltered dried blood smear, respectively. As expected, the percentage of mapped mitochondrial reads was lower in the unfiltered dried blood sample (0.03%) and approximately 6 times higher in the 5 µm filtered samples (Table 3). After filtering, the number of SNPs per sample identified in the mitochondrial genome varied from 162 to 341. A higher number of polymorphic variants was observed in the unfiltered dried blood smears (332), while the lowest mitochondrial polymorphic SNPs were counted in filtered venous blood samples (50) (Table 3). Analysis of the pooled data from the three samples identified 364 SNPs in the mitochondrial genome, of which 97.53% (355) were polymorphic.

Table 3. L. loa whole genome variant statistics

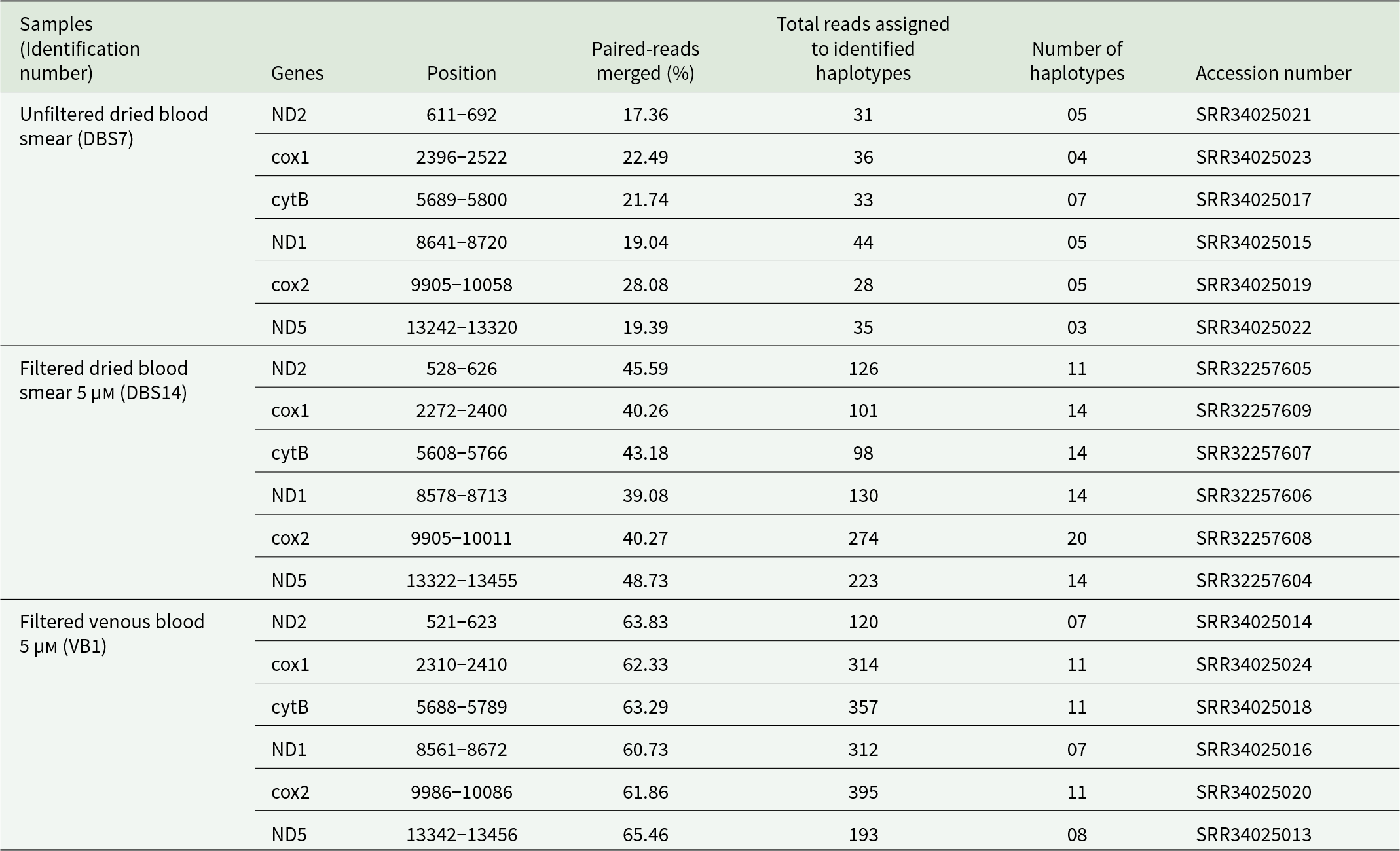

Estimation of mitochondrial haplotypes

We estimated the number of haplotypes in polymorphic regions (70 ∼ 150 bp) located in six genes, namely ND2, cox1, cytB, ND1, cox2 and ND5, distributed across the 13 590 bp mitochondrial genome. The number of reads in the filtered venous blood (mean: 282) and filtered dried sample (mean: 159) was higher than in the unfiltered dried blood spot (mean: 34.5) (Table 4). The rarefaction curves showed that deeper sequencing contributed to the identification of additional haplotypes (Figure 2). For each sample and each marker, the curves reached a plateau (Figure 2), indicating that the sequencing depth was sufficient.

Figure 2. Rarefaction curves showing the number of mitochondrial haplotypes detected as a function of sequencing depth across six mitochondrial genes.

Table 4. Number of microfilariae L. loa mitochondrial haplotypes estimated per individual in polymorphic regions located in six genes

Fewer mitochondrial haplotypes were observed in the unfiltered dried blood spot, ranging from 3 to 7 across six polymorphic regions. The venous blood and dried blood spots filtered with 5 µm pore size microfilters showed ranges of 7–11 and 11–20 haplotypes, respectively, depending on the genes (Table 4). Therefore, the number of mitochondrial haplotypes considered as the minimum number of female parents was 7 for unfiltered dried blood. It was higher for filtered venous blood and filtered dried samples: 11 and 20, respectively.

Discussion

Protocol optimization of DNA extraction from dried blood smears and enrichment of L. loa microfilariae

Dried blood smears are routinely used for filarial diagnosis in the medical setting to identify and detect the presence of microfilariae (Rosenblatt, Reference Rosenblatt2009). Yields for DNA extraction from dried blood smears are generally low, ranging from 15 to 880 ng, whereas a good amount of DNA (up to 10 µg) can be obtained using fresh venous blood samples (Dieki et al., Reference Dieki, Eyang-Assengone, Makouloutou-Nzassi, Bangueboussa, Emvo and Akue2022). Smear slides are made up of a small quantity of blood (∼50 µL), limiting the number of parasites and DNA amount (Paisal et al., Reference Paisal, Haryati, Arianti, Ridha and Annida2019). The integrity of microfilariae may also have been altered during a long storage period at room temperature, leading to the structure of microfilariae being more easily damaged and to a decrease in microfilarial material. The method that yielded the best results in DNA extraction from archived dried blood smears was the approach using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen), which has already been previously reported as the most efficient protocol (Gulas-Wroblewski et al., Reference Gulas-Wroblewski, Kairis, Gorchakov, Wheless and Murray2021; Dieki et al., Reference Dieki, Eyang-Assengone, Makouloutou-Nzassi, Bangueboussa, Emvo and Akue2022). The mean of DNA yield when using the chloroform-isoamyl protocol was lower: one possible explanation for this lower DNA retrieval is that there are several steps in the chloroform-isoamyl extraction method, and the tubes have to be changed each time, resulting in a loss of DNA (Dedhia et al., Reference Dedhia, Tarale, Dhongde, Khadapkar and Das2007; Dieki et al., Reference Dieki, Eyang-Assengone, Makouloutou-Nzassi, Bangueboussa, Emvo and Akue2022). However, using filtration columns as in the Qiagen kit could also lead to the loss of very small DNA fragments, thus resulting in sub-optimal yield.

Despite the low yield of DNA input, we were able to successfully sequence microfilarial DNA using a commercial library preparation protocol capable of processing samples with very low DNA input. Sequencing of unfiltered samples showed a low percentage of L. loa parasite reads. It thus appeared necessary to develop an optimized approach for reducing human contamination and enrichment for parasites before sequencing to maximize useful sequencing reads. Filtering would theoretically isolate microfilariae, and thus minimize the presence of human material in L. loa-infected blood samples (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Atkinson, Ramzy, Helmy, Farid, Bockarie, Susapu, Laney, Williams and Weil2006; Passos et al., Reference Passos, Barbosa, Almeida, Ogawa and Camargo2012). Using pore size 5 µm seems to be appropriate for isolation of L. loa microfilariae and is often used in other filarial parasites such as W. bancrofti (Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson, Eberhard and Lammie1990; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Atkinson, Ramzy, Helmy, Farid, Bockarie, Susapu, Laney, Williams and Weil2006), Dirofilaria immitis (Sungpradit, Reference Sungpradit2010) and B. malayi (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Reaves, Giguère, Coates, Rada and Wolstenholme2017). In fact, the size of L. loa microfilariae is approximately 250–300 μm long and 5–8 μm wide (Chunda et al., Reference Chunda, Fombad, Gandjui, Wanji and Akue2023). The diameter of human blood cells varies between 7 and 20 µm (Schmid-Schönbein et al., Reference Schmid-Schönbein, Shih and Chien1980), but these cells can be deformed by the action of lysis buffer during the elution of blood film and the washing steps during filtration. It is then assumed that microfilters with a pore size of 5 µm should be large enough to allow some human cells to pass through, while a pore size of 3 µm allows blood cells to be retained.

Polymorphism in the mitochondrial genome and female fertile polyinfection

Genetic analysis of microfilariae isolated from archived dried blood smears is poorly documented (Bisht et al., Reference Bisht, Hoti, Thangadurai and Das2006; Ramasamy et al., Reference Ramasamy, Laxmanappa, Sharma and Das2011; Mahakalkar et al., Reference Mahakalkar, Sapkal and Baig2017; Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Zendejas-Heredia, Graves, Sheridan, Sheel, Fuimaono, Lau and Grant2021) and no information was available for L. loa before the present study. Data on the burden of adult L. loa in humans are still scarce, as adult stages are very difficult to capture. However, occasional subconjunctival migration allows for surgical extraction and direct observation of L. loa adult parasites (Gawade and Patil Reference Gawade and Patil2018). Five female adult worms were extracted from an European traveler while they migrated subcutaneously after implementing courses of diethylcarbamazine treatment (Fain and Maertens Reference Fain and Maertens1973). This result is consistent with our data highlighting female adult worm polyinfection in loiasis individuals.

Indeed, analysis of polymorphism in the microfilariae mitochondrial genome from three individuals revealed 50, 207 and 332 polymorphic SNPs, respectively. In a study conducted on O. volvulus, 320 polymorphic variants were found in the 13 744 bp mitochondrial genome from a pool of 436 microfilariae (Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023). We analysed the mitochondrial genome from a pool of microfilariae and the presence of polymorphic SNPs reflected the variation of mitochondrial sequences within the population of microfilariae collected from the same individual, likely indicating infection with more than one fertile female parent. Indeed, Dennis et al. (Reference Dennis, Sands, Opoku, Debrah, Batsa, Pfarr, Klarmann-Schulz, Hoerauf, Specht, Scandale, Ranford-Cartwright and Lamberton2023) demonstrated that O. volvulus microfilariae dissected from the same adult female uterus showed high mitochondrial sequence similarity, with a maximum difference of only three SNPs to one another.

In the present study, we identified that the minimum number of female parent worms infecting individuals with loiasis varied from 7 to 20. In a similar study on W. bancrofti, the number of breeding females within the human host varied from 3 to 9 (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Fischer, Méité, Koudou, Fischer and Mitreva2024). In onchocerciasis, the number of haplotypes calculated from the combined variants called in the mitochondrial genome of microfilariae varied between 2 and 26 per individual (Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023). The number of estimated haplotypes is associated with the number of SNPs in mitochondrial DNA sequences as well as with the read depth of the genome. Indeed, a large number of microfilariae successfully sequenced is essential to accurately estimate the number of available haplotypes and to capture the diversity of the parent worms within the host (Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023).

In some experimental studies on animals injected with specific doses of filarial infective larvae, an increase in microfilariae density with adult worm burden has been demonstrated (Ansari Reference Ansari1964; Abraham Reference Abraham1985; McKenzie and Starks Reference McKenzie and Starks2008). In this study, a direct correlation between the minimum number of parental females, as inferred from mitochondrial haplotypes, and the initial microfilariae counts in blood samples could not be established. Microfilariae are subject to losses at different steps of the laboratory preparation, including scraping, where some microfilariae remain attached to the slide. In addition, physical pressure can damage microfilarial DNA (Paisal et al., Reference Paisal, Haryati, Arianti, Ridha and Annida2019), dissolution of the dried blood film with the lysis buffer can lead to the disintegration of some microfilariae (Ramasamy et al., Reference Ramasamy, Laxmanappa, Sharma and Das2011), and some microfilariae can pass through the pores during the filtration process (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Lambourne and Monteil1982). These losses are difficult to measure and reduce the number of microfilariae successfully sequenced.

Limitations of the analytic approach

This study aimed to determine whether mitochondrial genetic variation in L. loa microfilariae allowed for differentiation of infections with one reproductive female from polyinfection. For this purpose, the minimum number of female parents was estimated from the number of unique mitochondrial haplotypes across six polymorphic regions. While informative, our method has inherent limitations. Mitochondrial DNA-based approaches cannot distinguish sibling females carrying identical haplotypes and likely underestimate the minimum female worm population. The use of a short fragment (∼150 bp), although polymorphic, may not have fully captured the genetic diversity present across the entire mitochondrial genome. As a result, two distinct females might appear to share identical mitochondrial sequences when analysing a short region, despite differing at other positions of the genome. Previous studies (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Sands, Opoku, Debrah, Batsa, Pfarr, Klarmann-Schulz, Hoerauf, Specht, Scandale, Ranford-Cartwright and Lamberton2023; Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Fischer, Méité, Koudou, Fischer and Mitreva2024) have estimated the number of fecund females using whole-genome sequencing of individual microfilariae, allowing more accurate mitochondrial haplotype resolution. However, obtaining high-quality sequencing data from pooled microfilarial DNA extracted from archived blood smears remains challenging, and has limited the full genomic analysis. In addition, we acknowledge that a precise estimation of the number of reproductive females would require a series of sampling over time because the production of microfilariae by different females is unlikely to be synchronous.

In conclusion, our study provides the first evidence of female worm polyinfection in individuals with loiasis. Notably, we identified the minimum number of fertile female worms per individual, ranging from 7 to 20 and presented the first approach to estimate the L. loa female worm burden. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies on other filarial species (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Sands, Opoku, Debrah, Batsa, Pfarr, Klarmann-Schulz, Hoerauf, Specht, Scandale, Ranford-Cartwright and Lamberton2023; Hedtke et al., Reference Hedtke, Choi, Kode, Chalasani, Sirwani, Jada, Hotterbeekx, Mandro, Siewe Fodjo, Amambo, Abong, Wanji, Kuesel, Colebunders, Mitreva and Grant2023). Analysing the relationship between the estimated adult worm burden and clinical signs in patients diagnosed with loiasis may help to determine the impact of infecting adult worm parents on the disease severity. From a public health perspective, comparing the adult parasite load before and after treatment is of utmost importance. This will allow the identification of treatment failures and the detection of new infections, which indicate ongoing exposure. Given the approach of using short regions of the mitochondrial genome to estimate haplotypes, sequencing with nanopore technologies, which generate long reads, are recommended for precise assessment. Using such a tool requires fresh blood samples, rather than dried blood smears, which can be inappropriate as DNA can be damaged, leading to failed nanopore sequencing.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi/org.10.1017/S0031182025101285.

Data availability statement

Sequence data are available at the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1220113/

Acknowledgements

We thank Leane Fornies for her technical assistance during an undergraduate internship. We acknowledge the ISO 9001 certified IRD i-Trop HPC (South Green Platform) at IRD Montpellier for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper (https://bioinfo.ird.fr/-https://www.southgreen.fr/).

Author’s contribution

SDSP and FS conceived, supervised the study and obtained the funding. CBC, JTC and MB collected the clinical data, JAR and CM defined the laboratory methodology. JAR and NL performed the laboratory analysis. JAR carried out the bioinformatic and statistical analysis. JAR wrote the original draft. All co-authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), France through the LoaGen project (grant number ANR-21-CE17-0008-01).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Congolese Foundation for Medical Research (No. 036/CIE/FCRM/2022), the Congolese Ministry of Health and Population (No. 376/MSP/CAB/UCPP-21) and the National Ethics Committee of Cameroon (No. 2013/11/370/L/CNERSH/SP). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.