1. Introduction

Open jet flows are ubiquitous in technological processes such as fuel injection, thermal plasma spraying and electronics cooling. Researchers (Batchelor & Gill Reference Batchelor and Gill1962; Huerre & Monkewitz Reference Huerre and Monkewitz1990; Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2012 ; Drazin & Reid Reference Drazin and Reid2004) have examined their spatiotemporal stability and have established, through numerical and experimental investigations, that round jets with thin shear layers are convectively unstable to both the axisymmetric mode (

![]() $m=0$

) and the helical modes (

$m=0$

) and the helical modes (

![]() $m=\pm 1,\pm 2,\ldots$

) (Mattingly & Chang Reference Mattingly and Chang1974; Strange & Crighton Reference Strange and Crighton1983; Cohen & Wygnanski Reference Cohen and Wygnanski1987a

,Reference Cohen and Wygnanski

b

; Drubka, Reisenthel & Nagib Reference Drubka, Reisenthel and Nagib1989; Raman, Rice & Reshotko Reference Raman, Rice and Reshotko1994). Past studies have shown that the

$m=\pm 1,\pm 2,\ldots$

) (Mattingly & Chang Reference Mattingly and Chang1974; Strange & Crighton Reference Strange and Crighton1983; Cohen & Wygnanski Reference Cohen and Wygnanski1987a

,Reference Cohen and Wygnanski

b

; Drubka, Reisenthel & Nagib Reference Drubka, Reisenthel and Nagib1989; Raman, Rice & Reshotko Reference Raman, Rice and Reshotko1994). Past studies have shown that the

![]() $m=0$

mode dominates the near field, while the helical modes become prominent towards the end of the potential core (Michalke Reference Michalke1984; Cohen & Wygnanski Reference Cohen and Wygnanski1987b

; Corke, Shakib & Nagib Reference Corke, Shakib and Nagib1991; Corke & Kusek Reference Corke and Kusek1993). These modes generate large-scale coherent structures that are distributed either axisymmetrically (for

$m=0$

mode dominates the near field, while the helical modes become prominent towards the end of the potential core (Michalke Reference Michalke1984; Cohen & Wygnanski Reference Cohen and Wygnanski1987b

; Corke, Shakib & Nagib Reference Corke, Shakib and Nagib1991; Corke & Kusek Reference Corke and Kusek1993). These modes generate large-scale coherent structures that are distributed either axisymmetrically (for

![]() $m=0$

) or non-axisymmetrically (for

$m=0$

) or non-axisymmetrically (for

![]() $m\neq 0$

) with respect to the jet centreline, and they drive the spatiotemporal dynamics of the jet, including its mixing and entrainment (Becker & Massaro Reference Becker and Massaro1968; Crow & Champagne Reference Crow and Champagne1971; Winant & Browand Reference Winant and Browand1974; Brown & Roshko Reference Brown and Roshko1974; Yule Reference Yule1978; Rogers & Moser Reference Rogers and Moser1992; Moser & Rogers Reference Moser and Rogers1993). While these structures enhance mass, momentum and heat transport, they can prove detrimental when coupled with other system modes.

$m\neq 0$

) with respect to the jet centreline, and they drive the spatiotemporal dynamics of the jet, including its mixing and entrainment (Becker & Massaro Reference Becker and Massaro1968; Crow & Champagne Reference Crow and Champagne1971; Winant & Browand Reference Winant and Browand1974; Brown & Roshko Reference Brown and Roshko1974; Yule Reference Yule1978; Rogers & Moser Reference Rogers and Moser1992; Moser & Rogers Reference Moser and Rogers1993). While these structures enhance mass, momentum and heat transport, they can prove detrimental when coupled with other system modes.

Most open jets are convectively unstable and therefore behave as spatial amplifiers of extrinsic perturbations through shear layers instabilities (Freymuth Reference Freymuth1966; Michalke Reference Michalke1984). However, when the jet density is sufficiently below that of its surroundings, a region of local absolute instability develops in the near field (Monkewitz & Sohn Reference Monkewitz and Sohn1988). If this region is sufficiently large, then global instability arises, transforming the jet from a spatial amplifier of extrinsic perturbations to a self-excited oscillator with

![]() $m=0$

axisymmetric oscillations at a discrete natural frequency (Sreenivasan, Raghu & Kyle Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Yu & Monkewitz Reference Yu and Monkewitz1990; Monkewitz et al. Reference Monkewitz, Bechert, Barsikow and Lehmann1990; Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993; Jendoubi & Strykowski Reference Jendoubi and Strykowski1994; Chomaz Reference Chomaz2005; Lesshafft & Huerre Reference Lesshafft and Huerre2007; Coenen, Sevilla & Sánchez Reference Coenen, Sevilla and Sánchez2008; Lesshafft & Marquet Reference Lesshafft and Marquet2010; Srinivasan, Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Srinivasan, Hallberg and Strykowski2010; Coenen & Sevilla Reference Coenen and Sevilla2012). The onset of global instability in low-density axisymmetric jets is concomitant with the periodic roll-up of thin laminar shear layers into coherent vortical structures (Hallberg et al. Reference Hallberg, Srinivasan, Gorse and Strykowski2007), which advect downstream, grow, and undergo time-periodic vortex pairing through coalescence (Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993; Lesshafft, Huerre & Sagaut Reference Lesshafft, Huerre and Sagaut2007; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022). Compared with convectively unstable jets, globally unstable jets are less sensitive to low-amplitude perturbations, but their dynamics can still be controlled through forced synchronisation using high-amplitude time-periodic forcing applied around their natural global frequency (Chomaz Reference Chomaz2005; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013a

,Reference Li and Juniper

c

; Coenen et al. Reference Coenen, Lesshafft, Garnaud and Sevilla2017; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022). Studies to date have primarily focused on axial forcing with only temporal measurements, leaving the spatiotemporal dynamics under axisymmetric and non-axisymmetric forcing largely unexplored.

$m=0$

axisymmetric oscillations at a discrete natural frequency (Sreenivasan, Raghu & Kyle Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Yu & Monkewitz Reference Yu and Monkewitz1990; Monkewitz et al. Reference Monkewitz, Bechert, Barsikow and Lehmann1990; Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993; Jendoubi & Strykowski Reference Jendoubi and Strykowski1994; Chomaz Reference Chomaz2005; Lesshafft & Huerre Reference Lesshafft and Huerre2007; Coenen, Sevilla & Sánchez Reference Coenen, Sevilla and Sánchez2008; Lesshafft & Marquet Reference Lesshafft and Marquet2010; Srinivasan, Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Srinivasan, Hallberg and Strykowski2010; Coenen & Sevilla Reference Coenen and Sevilla2012). The onset of global instability in low-density axisymmetric jets is concomitant with the periodic roll-up of thin laminar shear layers into coherent vortical structures (Hallberg et al. Reference Hallberg, Srinivasan, Gorse and Strykowski2007), which advect downstream, grow, and undergo time-periodic vortex pairing through coalescence (Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993; Lesshafft, Huerre & Sagaut Reference Lesshafft, Huerre and Sagaut2007; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022). Compared with convectively unstable jets, globally unstable jets are less sensitive to low-amplitude perturbations, but their dynamics can still be controlled through forced synchronisation using high-amplitude time-periodic forcing applied around their natural global frequency (Chomaz Reference Chomaz2005; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013a

,Reference Li and Juniper

c

; Coenen et al. Reference Coenen, Lesshafft, Garnaud and Sevilla2017; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022). Studies to date have primarily focused on axial forcing with only temporal measurements, leaving the spatiotemporal dynamics under axisymmetric and non-axisymmetric forcing largely unexplored.

Globally unstable jets exhibit modal complexity: they are globally unstable to the axisymmetric mode (

![]() $m=0$

), but convectively unstable to the helical modes (

$m=0$

), but convectively unstable to the helical modes (

![]() $m=\pm 1,\pm 2,\ldots$

) (Monkewitz & Sohn Reference Monkewitz and Sohn1988; Jendoubi & Strykowski Reference Jendoubi and Strykowski1994; Lesshafft & Huerre Reference Lesshafft and Huerre2007; Coenen et al. Reference Coenen, Sevilla and Sánchez2008). The

$m=\pm 1,\pm 2,\ldots$

) (Monkewitz & Sohn Reference Monkewitz and Sohn1988; Jendoubi & Strykowski Reference Jendoubi and Strykowski1994; Lesshafft & Huerre Reference Lesshafft and Huerre2007; Coenen et al. Reference Coenen, Sevilla and Sánchez2008). The

![]() $m=0$

mode dominates the self-excited behaviour, yet the helical modes remain susceptible to external perturbations. Transverse forcing can preferentially excite these helical modes, breaking the natural axisymmetry by altering the topology of the vortical structures (Urbin & Métais Reference Urbin and Métais1997; Suzuki, Kasagi & Suzuki Reference Suzuki, Kasagi and Suzuki2004; Worth et al. Reference Worth, Mistry, Berk and Dawson2020; Æsøy et al. Reference Æsøy, Aguilar, Worth and Dawson2021). This motivates the study of how different forcing orientations (i.e. axial versus transverse) influence the spatiotemporal dynamics of globally unstable jets via their distinct modal interactions.

$m=0$

mode dominates the self-excited behaviour, yet the helical modes remain susceptible to external perturbations. Transverse forcing can preferentially excite these helical modes, breaking the natural axisymmetry by altering the topology of the vortical structures (Urbin & Métais Reference Urbin and Métais1997; Suzuki, Kasagi & Suzuki Reference Suzuki, Kasagi and Suzuki2004; Worth et al. Reference Worth, Mistry, Berk and Dawson2020; Æsøy et al. Reference Æsøy, Aguilar, Worth and Dawson2021). This motivates the study of how different forcing orientations (i.e. axial versus transverse) influence the spatiotemporal dynamics of globally unstable jets via their distinct modal interactions.

In the present experimental study, we adopt a classical vortex dynamics approach to exploring the evolution of a globally unstable self-excited jet under axial and transverse acoustic forcing applied around its natural global frequency over a wide range of forcing amplitudes. Before presenting our methodology (§ 2) and results (§ 3), we briefly review the concepts of synchronisation and its suppression mechanisms (§ 1.1), discuss previous work on the axial (§ 1.2) and transverse (§ 1.3) forcing of axisymmetric jets, using examples with global instability whenever possible, and review the application of complex networks for the analysis of vortical structures (§ 1.4).

1.1. Forced synchronisation as an open-loop control strategy

Forced synchronisation, also known as lock-in in fluid mechanics, occurs when a self-excited system oscillating at its natural frequency

![]() $f_n$

synchronises with external forcing applied at frequency

$f_n$

synchronises with external forcing applied at frequency

![]() $f_{\!f}$

, which is necessarily different from

$f_{\!f}$

, which is necessarily different from

![]() $f_n$

(Pikovsky, Rosenblum & Kurths Reference Pikovsky, Rosenblum and Kurths2003; Balanov et al. Reference Balanov, Janson, Postnov and Sosnovtseva2008). At lock-in, the applied forcing dictates the overall dynamics of the self-excited system, with minimal signs of the natural mode at

$f_n$

(Pikovsky, Rosenblum & Kurths Reference Pikovsky, Rosenblum and Kurths2003; Balanov et al. Reference Balanov, Janson, Postnov and Sosnovtseva2008). At lock-in, the applied forcing dictates the overall dynamics of the self-excited system, with minimal signs of the natural mode at

![]() $f_n$

(Sreenivasan et al. Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993). In recent years, this phenomenon has been exploited as an open-loop control strategy in various flow systems, including low-density jets (Sreenivasan et al. Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2008; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013a

,

Reference Li and Juniperc

; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022), jet diffusion flames (Juniper, Li & Nichols Reference Juniper, Li and Nichols2009; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013b

; Balusamy et al. Reference Balusamy, Li, Han, Juniper and Hochgreb2015), cylinder wakes (Provansal, Mathis & Boyer Reference Provansal, Mathis and Boyer1987; Baek & Sung Reference Baek and Sung2000) and thermoacoustic devices (Guan et al. Reference Guan, Gupta, Wan and Li2019; Mondal, Pawar & Sujith Reference Mondal, Pawar and Sujith2019). Depending on the forcing conditions, external actuation can either suppress the oscillation amplitude – sometimes to less than

$f_n$

(Sreenivasan et al. Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993). In recent years, this phenomenon has been exploited as an open-loop control strategy in various flow systems, including low-density jets (Sreenivasan et al. Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2008; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013a

,

Reference Li and Juniperc

; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022), jet diffusion flames (Juniper, Li & Nichols Reference Juniper, Li and Nichols2009; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013b

; Balusamy et al. Reference Balusamy, Li, Han, Juniper and Hochgreb2015), cylinder wakes (Provansal, Mathis & Boyer Reference Provansal, Mathis and Boyer1987; Baek & Sung Reference Baek and Sung2000) and thermoacoustic devices (Guan et al. Reference Guan, Gupta, Wan and Li2019; Mondal, Pawar & Sujith Reference Mondal, Pawar and Sujith2019). Depending on the forcing conditions, external actuation can either suppress the oscillation amplitude – sometimes to less than

![]() $20\,\%$

of the unforced levels – through asynchronous quenching (Guan et al. Reference Guan, Gupta, Wan and Li2019; Mondal et al. Reference Mondal, Pawar and Sujith2019; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022), or increase the amplitude through resonant amplification of the actuation signal (Keen & Fletcher Reference Keen and Fletcher1969; Abel, Ahnert & Bergweiler Reference Abel, Ahnert and Bergweiler2009; Guan et al. Reference Guan, Gupta, Wan and Li2019; Mondal et al. Reference Mondal, Pawar and Sujith2019; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that it is possible to manipulate the self-excited oscillations of globally unstable flows through a judicious choice of the applied forcing.

$20\,\%$

of the unforced levels – through asynchronous quenching (Guan et al. Reference Guan, Gupta, Wan and Li2019; Mondal et al. Reference Mondal, Pawar and Sujith2019; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022), or increase the amplitude through resonant amplification of the actuation signal (Keen & Fletcher Reference Keen and Fletcher1969; Abel, Ahnert & Bergweiler Reference Abel, Ahnert and Bergweiler2009; Guan et al. Reference Guan, Gupta, Wan and Li2019; Mondal et al. Reference Mondal, Pawar and Sujith2019; Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that it is possible to manipulate the self-excited oscillations of globally unstable flows through a judicious choice of the applied forcing.

It is worth noting that in globally unstable flows, the spatial location where velocity fluctuations reach maximum amplitude (the direct mode maximum) does not necessarily coincide with where the instability mechanism originates (the wavemaker region), nor does it identify the region most receptive to external forcing (Qadri, Chandler & Juniper Reference Qadri, Chandler and Juniper2018). The wavemaker region is determined by the overlap of the direct and adjoint modes (structural sensitivity), while receptivity is determined by the adjoint mode alone. Owing to convective amplification, the direct mode amplitude typically peaks downstream of the wavemaker region, a distinction that becomes important when interpreting spatially resolved measurements and when designing distributed control strategies (Lesshafft et al. Reference Lesshafft, Huerre, Sagaut and Terracol2006; Coenen et al. Reference Coenen, Lesshafft, Garnaud and Sevilla2017).

1.2. Response of jets to axial forcing

Axisymmetric jets generate large-scale coherent vortical structures in their near field (Becker & Massaro Reference Becker and Massaro1968; Brown & Roshko Reference Brown and Roshko1974; Laufer & Monkewitz Reference Laufer and Monkewitz1980). Axial forcing at the jet base controls the formation of these structures by influencing the vortex spacing and pairing dynamics (Crow & Champagne Reference Crow and Champagne1971; Zaman & Hussain Reference Zaman and Hussain1980; Hussain & Zaman Reference Hussain and Zaman1980; Ho & Huang Reference Ho and Huang1982; Gohil, Saha & Muralidhar Reference Gohil, Saha and Muralidhar2013; Boguslawski, Wawrzak & Tyliszczak Reference Boguslawski, Wawrzak and Tyliszczak2019). The forcing parameters impose distinct effects on vortex formation in convectively unstable jets. Specifically, higher forcing amplitudes produce larger vortex rings with enhanced circulation, while frequency variations control nonlinear phenomena such as vortex pairing and ring fragmentation (Aydemir, Worth & Dawson Reference Aydemir, Worth and Dawson2012; Gohil et al. Reference Gohil, Saha and Muralidhar2013). Previous studies (O’Connor & Lieuwen Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012a

; Lespinasse, Baillot & Boushaki Reference Lespinasse, Baillot and Boushaki2013; Malanoski et al. Reference Malanoski, Aguilar, Acharya and Lieuwen2013) have demonstrated that axial forcing preferentially excites the

![]() $m=0$

mode, resulting in axisymmetric roll-up of the shear layers into concentrated ring vortices. However, most studies have focused on convectively unstable jets, which respond to perturbations across a broad range of frequencies, whereas globally unstable jets exhibit fundamentally different responses.

$m=0$

mode, resulting in axisymmetric roll-up of the shear layers into concentrated ring vortices. However, most studies have focused on convectively unstable jets, which respond to perturbations across a broad range of frequencies, whereas globally unstable jets exhibit fundamentally different responses.

Recently, Kushwaha et al. (Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022) investigated an axially forced globally unstable jet in the framework of synchronisation across a range of frequencies (

![]() $0.8\leqslant f_{\!f}/f_n \leqslant 1.18$

) and amplitudes, revealing various nonlinear phenomena: (i) quasi-periodic behaviour when the jet is forced below the lock-in amplitude with its response at both

$0.8\leqslant f_{\!f}/f_n \leqslant 1.18$

) and amplitudes, revealing various nonlinear phenomena: (i) quasi-periodic behaviour when the jet is forced below the lock-in amplitude with its response at both

![]() $f_{\!f}$

and

$f_{\!f}$

and

![]() $f_n$

; (ii) a transition from quasi-periodic oscillations to periodic oscillations at

$f_n$

; (ii) a transition from quasi-periodic oscillations to periodic oscillations at

![]() $f_{\!f}$

when the forcing amplitude is above the critical lock-in threshold; (iii) an increase in the minimum forcing amplitude required for lock-in with an increase in frequency detuning, forming a V-shaped Arnold tongue centred at

$f_{\!f}$

when the forcing amplitude is above the critical lock-in threshold; (iii) an increase in the minimum forcing amplitude required for lock-in with an increase in frequency detuning, forming a V-shaped Arnold tongue centred at

![]() $f_{\!f}/f_n=1$

; (iv) synchronisation to

$f_{\!f}/f_n=1$

; (iv) synchronisation to

![]() $f_{\!f}$

via either a saddle-node bifurcation (the phase-locking route) or a torus-death bifurcation (the suppression route), depending on the proximity of

$f_{\!f}$

via either a saddle-node bifurcation (the phase-locking route) or a torus-death bifurcation (the suppression route), depending on the proximity of

![]() $f_{\!f}$

to

$f_{\!f}$

to

![]() $f_n$

(Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013a

). Similar synchronisation phenomena have been observed across other globally unstable flows, including low-density jets (Sreenivasan et al. Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2008), bluff-body wakes (Koopmann Reference Koopmann1967; Stansby Reference Stansby1976; Provansal et al. Reference Provansal, Mathis and Boyer1987; Van Atta & Gharib Reference Van Atta and Gharib1987; Karniadakis & Triantafyllou Reference Karniadakis and Triantafyllou1989), capillary jets (Olinger Reference Olinger1992), cross-flow jets (Davitian et al. Reference Davitian, Getsinger, Hendrickson and Karagozian2010a

,

Reference Davitian, Hendrickson, Getsinger, M’Closkey and Karagozianb

; Karagozian Reference Karagozian2010; Shoji et al. Reference Shoji, Harris, Besnard, Schein and Karagozian2020) and jet diffusion flames (Juniper et al. Reference Juniper, Li and Nichols2009; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013b

). However, the spatiotemporal dynamics and coherent structure evolution during these nonlinear transitions remain largely unexplored.

$f_n$

(Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013a

). Similar synchronisation phenomena have been observed across other globally unstable flows, including low-density jets (Sreenivasan et al. Reference Sreenivasan, Raghu and Kyle1989; Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2008), bluff-body wakes (Koopmann Reference Koopmann1967; Stansby Reference Stansby1976; Provansal et al. Reference Provansal, Mathis and Boyer1987; Van Atta & Gharib Reference Van Atta and Gharib1987; Karniadakis & Triantafyllou Reference Karniadakis and Triantafyllou1989), capillary jets (Olinger Reference Olinger1992), cross-flow jets (Davitian et al. Reference Davitian, Getsinger, Hendrickson and Karagozian2010a

,

Reference Davitian, Hendrickson, Getsinger, M’Closkey and Karagozianb

; Karagozian Reference Karagozian2010; Shoji et al. Reference Shoji, Harris, Besnard, Schein and Karagozian2020) and jet diffusion flames (Juniper et al. Reference Juniper, Li and Nichols2009; Li & Juniper Reference Li and Juniper2013b

). However, the spatiotemporal dynamics and coherent structure evolution during these nonlinear transitions remain largely unexplored.

1.3. Response of jets to transverse forcing

Only a handful of researchers, including O’Connor & Lieuwen (Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012) and Kushwaha et al. (Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022), have experimentally explored the forced response of a globally unstable jet to pure transverse forcing. They applied transverse forcing by positioning the jet at the pressure node of planar acoustic standing waves, where antisymmetric perturbations selectively excite the odd-

![]() $m$

helical hydrodynamic modes (

$m$

helical hydrodynamic modes (

![]() $m = \pm 1, \pm 3,\ldots$

) and induce transverse flapping motion through the superposition of counter-rotating

$m = \pm 1, \pm 3,\ldots$

) and induce transverse flapping motion through the superposition of counter-rotating

![]() $m = \pm 1$

modes of equal amplitude (O’Connor & Lieuwen Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012a

,

Reference O’Connor and Lieuwenb

; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Emerson, Proscia and Lieuwen2018)

$m = \pm 1$

modes of equal amplitude (O’Connor & Lieuwen Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012a

,

Reference O’Connor and Lieuwenb

; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Emerson, Proscia and Lieuwen2018)

O’Connor & Lieuwen (Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012) applied transverse forcing to a swirling annular jet wherein the global mode manifests as a central vortex breakdown bubble. While transverse forcing caused mode switching between

![]() $m=-1$

and

$m=-1$

and

![]() $m=-2$

by altering their relative amplitudes without affecting the axisymmetric

$m=-2$

by altering their relative amplitudes without affecting the axisymmetric

![]() $m=0$

mode, it did not give rise to lock-in or asynchronous/synchronous quenching, even at higher forcing amplitudes. In contrast to swirling jets, Kushwaha et al. (Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022) demonstrated that transverse forcing of a globally unstable axisymmetric jet leads to fundamentally different behaviour: (i) a transition from a periodic state to a quasi-periodic state at low amplitudes; and (ii) when forced above a critical amplitude, a transition from quasi-periodicity to lock-in via the suppression route, regardless of the proximity of

$m=0$

mode, it did not give rise to lock-in or asynchronous/synchronous quenching, even at higher forcing amplitudes. In contrast to swirling jets, Kushwaha et al. (Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022) demonstrated that transverse forcing of a globally unstable axisymmetric jet leads to fundamentally different behaviour: (i) a transition from a periodic state to a quasi-periodic state at low amplitudes; and (ii) when forced above a critical amplitude, a transition from quasi-periodicity to lock-in via the suppression route, regardless of the proximity of

![]() $f_{\!f}$

to

$f_{\!f}$

to

![]() $f_n$

. Unlike that of a swirling jet, transverse forcing of an axisymmetric jet disrupts the natural axisymmetry, yielding substantial amplitude reduction via asynchronous quenching without resonant amplification. These contrasting responses highlight how the forcing symmetry influences the modal excitation and nonlinear dynamics that depend critically on the jet configuration.

$f_n$

. Unlike that of a swirling jet, transverse forcing of an axisymmetric jet disrupts the natural axisymmetry, yielding substantial amplitude reduction via asynchronous quenching without resonant amplification. These contrasting responses highlight how the forcing symmetry influences the modal excitation and nonlinear dynamics that depend critically on the jet configuration.

Over the past few years, Lieuwen and co-workers (O’Connor et al. Reference O’Connor, Natarajan, Malanoski and Lieuwen2010, Reference O’Connor, Acharya and Lieuwen2015; O’Connor & Lieuwen Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2011, Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012a , Reference O’Connor and Lieuwenb ; Blimbaum et al. Reference Blimbaum, Zanchetta, Akin, Acharya, O’Connor, Noble and Lieuwen2012; Malanoski et al. Reference Malanoski, Aguilar, Acharya and Lieuwen2013; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Emerson, Proscia and Lieuwen2018; Acharya & Lieuwen Reference Acharya and Lieuwen2018) and several other researchers, including Parekh, Leonard & Reynolds (Reference Parekh, Leonard and Reynolds1988), Corke & Kusek (Reference Corke and Kusek1993), Da Silva & Métais (Reference Da Silva and Métais2002), Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Parekh, Juvet and Lee2003), Sadeghi & Pollard (Reference Sadeghi and Pollard2012), Tyliszczak & Geurts (Reference Tyliszczak and Geurts2014) and Gohil, Saha & Muralidhar (Reference Gohil, Saha and Muralidhar2015), have extensively studied the effects of transverse forcing on the mixing, entrainment and spreading characteristics of convectively unstable jets and flames. Unlike globally unstable jets, convectively unstable jets act as spatial amplifiers, making their coherent structures readily susceptible to external forcing (Urbin & Métais Reference Urbin and Métais1997; Danaila & Boersma Reference Danaila and Boersma2000; Worth et al. Reference Worth, Mistry, Berk and Dawson2020; Douglas et al. Reference Douglas, Emerson, Hemchandra and Lieuwen2021), including combinations of axial and transverse forcing applied at a common frequency (Æsøy et al. Reference Æsøy, Aguilar, Worth and Dawson2021) or at two distinct frequencies (Da Silva & Métais Reference Da Silva and Métais2002). These studies collectively indicate that transverse forcing induces out-of-phase roll-up of the shear layers on both sides of the jet centreline, resulting in the formation of staggered vortical structures in the near field (Hauser, Lorenz & Sattelmayer Reference Hauser, Lorenz and Sattelmayer2010; O’Connor & Lieuwen Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012; Saurabh & Paschereit Reference Saurabh and Paschereit2017, Reference Saurabh and Paschereit2018; Saurabh, Moeck & Paschereit Reference Saurabh, Moeck and Paschereit2017). Most non-axisymmetric forcing studies (Juniper Reference Juniper2012; O’Connor & Lieuwen Reference O’Connor and Lieuwen2012; Tammisola & Juniper Reference Tammisola and Juniper2016) have focused on convectively unstable jets, leaving the effects of transverse forcing on globally unstable jets largely unexplored.

1.4. Complex network analysis of vortical structures

The vortical structures in the near field of a jet nonlinearly interact during vortex merging. These dynamics are influenced by the spatial symmetry of external forcing. Network-based analysis can aid in characterising these interactions through complex networks, in which nodes represent vortical structures and edges represent their interactions (Nair & Taira Reference Nair and Taira2015; Krishnan et al. Reference Krishnan, Sujith, Marwan and Kurths2021). This approach has been applied across various scientific disciplines to uncover insights into the collective behaviour of complex systems. Recent applications include epidemics (Morris Reference Morris1993; Lloyd-Smith et al. Reference Lloyd-Smith, Schreiber, Kopp and Getz2005), climatology (Tsonis & Roebber Reference Tsonis and Roebber2004; Donges et al. Reference Donges, Zou, Marwan and Kurths2009, Reference Donges, Petrova, Loew, Marwan and Kurths2015), sociology (Arenas et al. Reference Arenas, Díaz-Guilera, Kurths, Moreno and Zhou2008), economics (Namatame, Kaizouji & Aruka Reference Namatame, Kaizouji and Aruka2006), thermoacoustics (Murugesan & Sujith Reference Murugesan and Sujith2015; Murayama et al. Reference Murayama, Kinugawa, Tokuda and Gotoda2018; Krishnan et al. Reference Krishnan, Sujith, Marwan and Kurths2021; Guan et al. Reference Guan, Moon, Kim and Li2022; Tandon & Sujith Reference Tandon and Sujith2023) and hydrodynamics (Nair & Taira Reference Nair and Taira2017; Iacobello et al. Reference Iacobello, Scarsoglio, Kuerten and Ridolfi2018; Meena, Nair & Taira Reference Meena, Nair and Taira2018; Nair, Brunton & Taira Reference Nair, Brunton and Taira2018). Using the framework of network-based analysis, Nair & Taira (Reference Nair and Taira2015) and Krishnan et al. (Reference Krishnan, Sujith, Marwan and Kurths2021) have demonstrated that targeting the primary hub vortices can provide an effective means of controlling the flow dynamics and suppressing self-excited instabilities. In the present study, we use the Biot–Savart law to construct time-resolved weighted spatial networks, with the aim of uncovering any hidden spatiotemporal patterns in the near field and exploring how vortical networks yield distinct dynamics under different forcing conditions.

1.5. Contributions of the present study

It is now well known that globally unstable axisymmetric jets exhibit periodic vortex formation at their natural frequency

![]() $f_n$

. When axially forced, these jets undergo forced synchronisation, and can experience substantial amplitude reduction through asynchronous quenching when

$f_n$

. When axially forced, these jets undergo forced synchronisation, and can experience substantial amplitude reduction through asynchronous quenching when

![]() $f_{\!f}$

deviates sufficiently from

$f_{\!f}$

deviates sufficiently from

![]() $f_n$

. Although these nonlinear transitions are well-characterised, the underlying spatiotemporal evolution of the coherent structures remains largely unexplored. Furthermore, the influence of transverse forcing on globally unstable jets and the resulting topological variations in their vortical structures have received limited attention compared to the influence of axial forcing. To address these knowledge gaps, we use time-resolved particle image velocimetry (PIV) to investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of a globally unstable jet under axial and transverse acoustic forcing. Specifically, we aim to answer the following research questions.

$f_n$

. Although these nonlinear transitions are well-characterised, the underlying spatiotemporal evolution of the coherent structures remains largely unexplored. Furthermore, the influence of transverse forcing on globally unstable jets and the resulting topological variations in their vortical structures have received limited attention compared to the influence of axial forcing. To address these knowledge gaps, we use time-resolved particle image velocimetry (PIV) to investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of a globally unstable jet under axial and transverse acoustic forcing. Specifically, we aim to answer the following research questions.

-

(i) While axial forcing can either amplify or attenuate oscillations depending on the frequency detuning, transverse forcing consistently suppresses oscillations through asynchronous quenching. What are the underlying physical mechanisms responsible for the distinct amplitude responses observed under axial versus transverse forcing?

-

(ii) How does the spatiotemporal evolution of vortical structures differ between axial and transverse forcing as the jet transitions through different dynamical states? Specifically, how do different forcing symmetries and amplitudes affect vortex formation and the spatial organisation of coherent structures during transitions from an unforced periodic state through quasi-periodicity to forced synchronisation at lock-in?

-

(iii) How do different forcing orientations redistribute energy among the modal structures and modify the vortical interaction patterns to influence the global flow response?

2. Experimental methodology

2.1. Jet set-up and characterisation

The experimental set-up consists of two primary components: (i) a hydrodynamic system that generates a globally unstable axisymmetric jet, and (ii) a rectangular enclosure housing the acoustic forcing system. The coordinate system defines the streamwise, transverse (radial) and cross-stream directions as

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

, respectively, as shown in figure 1. The hydrodynamic system comprises an axisymmetric convergent nozzle (exit diameter

$z$

, respectively, as shown in figure 1. The hydrodynamic system comprises an axisymmetric convergent nozzle (exit diameter

![]() $D = 6$

mm) with an upstream settling chamber equipped with a honeycomb flow straightener. Pure helium is supplied from a compressed gas cylinder and regulated using a mass flow controller (Alicat MCR-500), producing a low-density jet with density ratio

$D = 6$

mm) with an upstream settling chamber equipped with a honeycomb flow straightener. Pure helium is supplied from a compressed gas cylinder and regulated using a mass flow controller (Alicat MCR-500), producing a low-density jet with density ratio

![]() $S \equiv \rho _{\!j}/\rho _{\infty } = 0.14$

, which is sufficiently below the upper limit for global instability (Monkewitz et al. Reference Monkewitz, Bechert, Barsikow and Lehmann1990; Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993). The nozzle features an area contraction ratio of 34 : 1, with its wall profile defined by a fifth-order polynomial to prevent flow separation. The nozzle outlet protrudes

$S \equiv \rho _{\!j}/\rho _{\infty } = 0.14$

, which is sufficiently below the upper limit for global instability (Monkewitz et al. Reference Monkewitz, Bechert, Barsikow and Lehmann1990; Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993). The nozzle features an area contraction ratio of 34 : 1, with its wall profile defined by a fifth-order polynomial to prevent flow separation. The nozzle outlet protrudes

![]() $1.67D$

into the enclosure to minimise wall effects, and can be repositioned along the transverse direction to adjust the jet position relative to the acoustic standing wave.

$1.67D$

into the enclosure to minimise wall effects, and can be repositioned along the transverse direction to adjust the jet position relative to the acoustic standing wave.

Figure 1. Schematic of the experimental set-up, whose key components consist of a nozzle with exit diameter 6 mm, a rectangular enclosure of dimensions

![]() $L \times W \times H =0.96 \times 0.22 \times 0.59\ \text{m}^3$

in which a standing wave acoustic field is set up, and a pair of loudspeakers fitted with resonance tubes mounted on the movable end-walls of the enclosure. The measurement diagnostics include a high-speed Nd:YLF laser, a set of sheet-forming optics, a pair of high-speed monochrome cameras, and four microphones mounted on the side-walls of the enclosure. MFC: mass flow controller. DAQ: data acquisition system.

$L \times W \times H =0.96 \times 0.22 \times 0.59\ \text{m}^3$

in which a standing wave acoustic field is set up, and a pair of loudspeakers fitted with resonance tubes mounted on the movable end-walls of the enclosure. The measurement diagnostics include a high-speed Nd:YLF laser, a set of sheet-forming optics, a pair of high-speed monochrome cameras, and four microphones mounted on the side-walls of the enclosure. MFC: mass flow controller. DAQ: data acquisition system.

Before examining the jet dynamics, we first characterise the velocity field using hot-wire anemometry (HWA) across Reynolds numbers

![]() $700 \leqslant \textit{Re} \equiv U_{\!j}\rho _{\!j}D/\mu _{\!j}\leqslant 3990$

, where

$700 \leqslant \textit{Re} \equiv U_{\!j}\rho _{\!j}D/\mu _{\!j}\leqslant 3990$

, where

![]() $U_{\!j}$

,

$U_{\!j}$

,

![]() $\rho _{\!j}$

and

$\rho _{\!j}$

and

![]() $\mu _{\!j}$

are the jet centreline velocity, density and dynamic viscosity, respectively. We acquire the time-averaged streamwise velocity and its local fluctuations as functions of radial position at

$\mu _{\!j}$

are the jet centreline velocity, density and dynamic viscosity, respectively. We acquire the time-averaged streamwise velocity and its local fluctuations as functions of radial position at

![]() $x/D \approx 0.1$

. Figure 2(a) shows radial profiles of the normalised time-averaged streamwise velocity

$x/D \approx 0.1$

. Figure 2(a) shows radial profiles of the normalised time-averaged streamwise velocity

![]() $\overline {u}/\overline {u}_{\textit{max}}$

, revealing a top-hat profile characterised by thin shear layers. While these velocity profiles contribute to a quiet mean flow, sufficiently weak velocity fluctuations in the jet core (

$\overline {u}/\overline {u}_{\textit{max}}$

, revealing a top-hat profile characterised by thin shear layers. While these velocity profiles contribute to a quiet mean flow, sufficiently weak velocity fluctuations in the jet core (

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}/\overline {u} \lt 0.35 \,\%$

), as observed in figure 2(b), indicate that the shear layers are laminar (Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2006). This flow state facilitates the detection of global instability at low

$u_{\textit{rms}}/\overline {u} \lt 0.35 \,\%$

), as observed in figure 2(b), indicate that the shear layers are laminar (Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2006). This flow state facilitates the detection of global instability at low

![]() $\textit{Re}$

, restricting amplification of inherent disturbances by convective modes (Hallberg et al. Reference Hallberg, Srinivasan, Gorse and Strykowski2007). The transverse curvature

$\textit{Re}$

, restricting amplification of inherent disturbances by convective modes (Hallberg et al. Reference Hallberg, Srinivasan, Gorse and Strykowski2007). The transverse curvature

![]() $D/\theta _0$

, which is an inverse non-dimensional form of the momentum thickness of the initial shear layers

$D/\theta _0$

, which is an inverse non-dimensional form of the momentum thickness of the initial shear layers

![]() $\theta _0$

, scales linearly with

$\theta _0$

, scales linearly with

![]() $\sqrt {\textit{Re}}$

, as per figure 2(c). This linear dependence suggests that the initial shear layers are indeed laminar (Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993; Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2006), aiding the detection of global instability.

$\sqrt {\textit{Re}}$

, as per figure 2(c). This linear dependence suggests that the initial shear layers are indeed laminar (Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993; Hallberg & Strykowski Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2006), aiding the detection of global instability.

Figure 2. Characterisation of the flow: (a) normalised time-averaged streamwise velocity and (b) its local fluctuation, both as functions of the radial position. (c) Transverse curvature as a function of the square root of

![]() $\textit{Re}$

. (d) Normalised amplitude and (e) PSD of the HWA velocity fluctuations in the unforced jet across a range of

$\textit{Re}$

. (d) Normalised amplitude and (e) PSD of the HWA velocity fluctuations in the unforced jet across a range of

![]() $\textit{Re}$

, with (e) showing the forward path only. The selected operating point (regime IV,

$\textit{Re}$

, with (e) showing the forward path only. The selected operating point (regime IV,

![]() $\textit{Re} = 800$

) corresponds to conditions where the jet is dominated by global hydrodynamic instability, producing self-excited axisymmetric oscillations (

$\textit{Re} = 800$

) corresponds to conditions where the jet is dominated by global hydrodynamic instability, producing self-excited axisymmetric oscillations (

![]() $m = 0$

) as confirmed by schlieren visualisation (see inset). Measurements were acquired using a hot-wire anemometer (Dantec 55P11) positioned at

$m = 0$

) as confirmed by schlieren visualisation (see inset). Measurements were acquired using a hot-wire anemometer (Dantec 55P11) positioned at

![]() $x/D \approx 0.1$

, as per our previous work (Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022), establishing the baseline flow characteristics for subsequent forcing experiments.

$x/D \approx 0.1$

, as per our previous work (Kushwaha et al. Reference Kushwaha, Worth, Dawson, Gupta and Li2022), establishing the baseline flow characteristics for subsequent forcing experiments.

The rectangular enclosure (length

![]() $L = 0.96{-}1.35$

m, width

$L = 0.96{-}1.35$

m, width

![]() $W = 0.22$

m, height

$W = 0.22$

m, height

![]() $H = 0.59$

m) is used to generate planar transverse acoustic standing waves through two loudspeakers mounted at either end. The adjustable length of the enclosure enables resonance between the chamber acoustics and the loudspeaker forcing at a specified frequency:

$H = 0.59$

m) is used to generate planar transverse acoustic standing waves through two loudspeakers mounted at either end. The adjustable length of the enclosure enables resonance between the chamber acoustics and the loudspeaker forcing at a specified frequency:

![]() $0.8\lt f_{\!f}/f_n\lt 1.18$

. A signal generator (Aim-TTi TGA1244) connected to power amplifiers (200 W Crown CE1000) drives the two loudspeakers (Monacor KU-516) to produce the desired acoustic forcing. The loudspeakers are fitted with resonance tubes mounted on the movable end-walls of the enclosure. We apply both axial and transverse forcing at

$0.8\lt f_{\!f}/f_n\lt 1.18$

. A signal generator (Aim-TTi TGA1244) connected to power amplifiers (200 W Crown CE1000) drives the two loudspeakers (Monacor KU-516) to produce the desired acoustic forcing. The loudspeakers are fitted with resonance tubes mounted on the movable end-walls of the enclosure. We apply both axial and transverse forcing at

![]() $f_{\!f}/f_n = 1.09$

across a wide range of forcing amplitudes. Four flush-mounted microphones (Brüel and Kjær 4939-A-011), installed along the side-wall of the enclosure, capture the pressure field, enabling reconstruction of the acoustic mode shape using the multiple microphone method, which estimates the magnitudes of the incident (

$f_{\!f}/f_n = 1.09$

across a wide range of forcing amplitudes. Four flush-mounted microphones (Brüel and Kjær 4939-A-011), installed along the side-wall of the enclosure, capture the pressure field, enabling reconstruction of the acoustic mode shape using the multiple microphone method, which estimates the magnitudes of the incident (

![]() $p_i$

) and reflected (

$p_i$

) and reflected (

![]() $p_r$

) plane waves (Jang & Ih Reference Jang and Ih1998). The quality of the standing wave generated can be quantified by the spin ratio

$p_r$

) plane waves (Jang & Ih Reference Jang and Ih1998). The quality of the standing wave generated can be quantified by the spin ratio

![]() $\textit{SR} = (|p_i| - |p_r|)/(|p_i| + |p_r|)$

, where

$\textit{SR} = (|p_i| - |p_r|)/(|p_i| + |p_r|)$

, where

![]() $\textit{SR} \rightarrow 0$

indicates a perfect standing wave (Bourgouin et al. Reference Bourgouin, Durox, Moeck, Schuller and Candel2013). In our experiments, a high-quality standing wave is consistently maintained with

$\textit{SR} \rightarrow 0$

indicates a perfect standing wave (Bourgouin et al. Reference Bourgouin, Durox, Moeck, Schuller and Candel2013). In our experiments, a high-quality standing wave is consistently maintained with

![]() $\textit{SR} = \pm 0.01$

. Pure axial and pure transverse forcing are achieved by positioning the jet nozzle at the pressure antinode and pressure node of the standing wave, respectively. The nozzle position relative to the acoustic mode shape is adjusted by moving both end-walls in the same direction, while maintaining a constant enclosure length, ensuring that the acoustic resonance condition is preserved.

$\textit{SR} = \pm 0.01$

. Pure axial and pure transverse forcing are achieved by positioning the jet nozzle at the pressure antinode and pressure node of the standing wave, respectively. The nozzle position relative to the acoustic mode shape is adjusted by moving both end-walls in the same direction, while maintaining a constant enclosure length, ensuring that the acoustic resonance condition is preserved.

2.2. Natural jet dynamics

Before examining the spatiotemporal dynamics of the forced jet, we first identify an operational state for applying external forcing. This involves systematically varying

![]() $\textit{Re}$

and searching for potential hysteresis and bistability regimes. Figures 2(d) and 2(e) show the amplitude and power spectral density (PSD) of the HWA velocity fluctuations in the unforced jet at different

$\textit{Re}$

and searching for potential hysteresis and bistability regimes. Figures 2(d) and 2(e) show the amplitude and power spectral density (PSD) of the HWA velocity fluctuations in the unforced jet at different

![]() $\textit{Re}$

values. The jet amplitude is defined as the root mean square velocity fluctuation normalised by the time-averaged velocity:

$\textit{Re}$

values. The jet amplitude is defined as the root mean square velocity fluctuation normalised by the time-averaged velocity:

![]() $\gamma _{\textit{rms}}/\overline {\gamma }$

. By examining the jet amplitude and PSD, we uncover four distinct jet regimes.

$\gamma _{\textit{rms}}/\overline {\gamma }$

. By examining the jet amplitude and PSD, we uncover four distinct jet regimes.

In regime I (

![]() $148 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 400$

), the jet is globally stable but convectively unstable, as indicated by the low oscillation amplitudes in figure 2(d) and a lack of a distinct spectral peak in figure 2(e). This suggests that the amplification of background disturbances by local convective modes is insufficient to overcome the stabilising effect of viscosity.

$148 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 400$

), the jet is globally stable but convectively unstable, as indicated by the low oscillation amplitudes in figure 2(d) and a lack of a distinct spectral peak in figure 2(e). This suggests that the amplification of background disturbances by local convective modes is insufficient to overcome the stabilising effect of viscosity.

In regime II (

![]() $400 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 562$

), the jet exhibits hysteresis: as

$400 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 562$

), the jet exhibits hysteresis: as

![]() $\textit{Re}$

increases along the forward path, the jet amplitude exhibits an abrupt increase (figure 2

d) at a critical Reynolds number (

$\textit{Re}$

increases along the forward path, the jet amplitude exhibits an abrupt increase (figure 2

d) at a critical Reynolds number (

![]() $\textit{Re} = 474$

), coinciding with the emergence of a sharp peak in the PSD (figure 2

e). This marks a sudden transition from a globally stable state (a fixed-point attractor) to a globally unstable state (a self-excited limit cycle). Conversely, along the backward path achieved by decreasing

$\textit{Re} = 474$

), coinciding with the emergence of a sharp peak in the PSD (figure 2

e). This marks a sudden transition from a globally stable state (a fixed-point attractor) to a globally unstable state (a self-excited limit cycle). Conversely, along the backward path achieved by decreasing

![]() $\textit{Re}$

, the jet remains globally unstable throughout the entire regime; the PSD depicted in figure 2(e) pertains to the forward path only. These differences between the forward and backward paths are indicative of a subcritical Hopf bifurcation.

$\textit{Re}$

, the jet remains globally unstable throughout the entire regime; the PSD depicted in figure 2(e) pertains to the forward path only. These differences between the forward and backward paths are indicative of a subcritical Hopf bifurcation.

In regime III (

![]() $562 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 695$

), the jet amplitude initially rises sharply before decreasing as

$562 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 695$

), the jet amplitude initially rises sharply before decreasing as

![]() $\textit{Re}$

increases, while the dominant frequency in the PSD remains relatively constant. This non-monotonic amplitude behaviour suggests that the global hydrodynamic mode of the jet has synchronised with the natural acoustic mode of the nozzle. This hydroacoustic resonance at a fixed Helmholtz number renders this regime unsuitable for forcing experiments, as the jet dynamics is no longer governed by global hydrodynamic instability alone.

$\textit{Re}$

increases, while the dominant frequency in the PSD remains relatively constant. This non-monotonic amplitude behaviour suggests that the global hydrodynamic mode of the jet has synchronised with the natural acoustic mode of the nozzle. This hydroacoustic resonance at a fixed Helmholtz number renders this regime unsuitable for forcing experiments, as the jet dynamics is no longer governed by global hydrodynamic instability alone.

In regime IV (

![]() $695 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 888$

), the jet amplitude and frequency resume increasing trends with further increases in

$695 \lt \textit{Re} \lt 888$

), the jet amplitude and frequency resume increasing trends with further increases in

![]() $\textit{Re}$

, indicating that the global hydrodynamic mode is no longer synchronised with the nozzle acoustic modes. In regimes II and IV, the dominant frequency scales with

$\textit{Re}$

, indicating that the global hydrodynamic mode is no longer synchronised with the nozzle acoustic modes. In regimes II and IV, the dominant frequency scales with

![]() $\textit{Re}$

, a trend consistent with the viscous diffusion time scaling proposed by Hallberg & Strykowski (Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2006).

$\textit{Re}$

, a trend consistent with the viscous diffusion time scaling proposed by Hallberg & Strykowski (Reference Hallberg and Strykowski2006).

2.3. Stereoscopic PIV

We perform planar time-resolved stereoscopic PIV measurements to examine the spatiotemporal dynamics of the jet. The system comprises a high-speed Nd:YLF laser (LDY303HE-PIV) operating at 527 nm wavelength with 5

![]() $\text{mJ}\ \text{pulse}^{-1}$

energy at 10 kHz repetition rate, sheet-forming optics (Thorlabs), and two high-speed monochrome cameras (Photron FASTCAM SA1.1) with maximum frame rate 5.1 kHz at 1 megapixel resolution. Both cameras are equipped with Scheimpflug adapters and 180 mm lenses, with optical axes positioned

$\text{mJ}\ \text{pulse}^{-1}$

energy at 10 kHz repetition rate, sheet-forming optics (Thorlabs), and two high-speed monochrome cameras (Photron FASTCAM SA1.1) with maximum frame rate 5.1 kHz at 1 megapixel resolution. Both cameras are equipped with Scheimpflug adapters and 180 mm lenses, with optical axes positioned

![]() $12.5^\circ$

relative to the measurement plane normal for stereoscopic reconstruction. The measurement plane bisects the nozzle in the

$12.5^\circ$

relative to the measurement plane normal for stereoscopic reconstruction. The measurement plane bisects the nozzle in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane, illuminated by a laser sheet of 1 mm thickness. Both the ambient air in the enclosure and the jet flow are seeded with olive oil droplets produced by a Laskin nozzle, ensuring sufficient particle density throughout the measurement domain.

$y$

plane, illuminated by a laser sheet of 1 mm thickness. Both the ambient air in the enclosure and the jet flow are seeded with olive oil droplets produced by a Laskin nozzle, ensuring sufficient particle density throughout the measurement domain.

We acquire time-resolved image pairs at

![]() $768 \times 512$

pixel resolution and

$768 \times 512$

pixel resolution and

![]() $5442$

Hz frame rate, capturing six instantaneous snapshots per forcing cycle. The inter-frame time delay is set to

$5442$

Hz frame rate, capturing six instantaneous snapshots per forcing cycle. The inter-frame time delay is set to

![]() $\delta t = 12$

microseconds, maintaining a maximum pixel displacement below 7 pixels. The recorded images span a field of view

$\delta t = 12$

microseconds, maintaining a maximum pixel displacement below 7 pixels. The recorded images span a field of view

![]() $4.44D \times 2.96D$

, with

$4.44D \times 2.96D$

, with

![]() $4000$

image pairs acquired at each experimental condition. Image processing is performed using DaVis 8.2.2 software (LaVision) following established protocols. Initially, a self-calibration routine corrects any misalignment between the laser sheet and calibration plate. Next, the image pairs are preprocessed using a sliding background subtraction filter with a 32 pixel kernel and a particle intensity normalisation filter with an 8 pixel filter kernel to enhance particle contrast and reduce background noise. Velocity vectors are computed using multi-pass stereo cross-correlation: an initial pass with

$4000$

image pairs acquired at each experimental condition. Image processing is performed using DaVis 8.2.2 software (LaVision) following established protocols. Initially, a self-calibration routine corrects any misalignment between the laser sheet and calibration plate. Next, the image pairs are preprocessed using a sliding background subtraction filter with a 32 pixel kernel and a particle intensity normalisation filter with an 8 pixel filter kernel to enhance particle contrast and reduce background noise. Velocity vectors are computed using multi-pass stereo cross-correlation: an initial pass with

![]() $64 \times 64$

pixel interrogation windows with square weighting,

$64 \times 64$

pixel interrogation windows with square weighting,

![]() $50 \,\%$

overlap, followed by two refinement passes with

$50 \,\%$

overlap, followed by two refinement passes with

![]() $32 \times 32$

pixel windows with elliptical 2 : 1 weighting,

$32 \times 32$

pixel windows with elliptical 2 : 1 weighting,

![]() $75 \,\%$

overlap. The final interrogation window dimensions correspond to

$75 \,\%$

overlap. The final interrogation window dimensions correspond to

![]() $1.11 \times 1.11$

mm

$1.11 \times 1.11$

mm

![]() $^2$

in physical coordinates. Each subsequent pass uses the velocity estimates from the previous iteration to improve the accuracy of the final vector field through a refinement process. Upon completion of the cross-correlation analysis, velocity vectors undergo post-processing through vector validation routines incorporating three rejection criteria: (i) velocity vectors exceeding 30 m s

$^2$

in physical coordinates. Each subsequent pass uses the velocity estimates from the previous iteration to improve the accuracy of the final vector field through a refinement process. Upon completion of the cross-correlation analysis, velocity vectors undergo post-processing through vector validation routines incorporating three rejection criteria: (i) velocity vectors exceeding 30 m s

![]() $^{-1}$

are discarded as unphysical; (ii) a median filter removes spurious vectors whose root-mean-square magnitude exceeds twice the local neighbourhood average; and (iii) isolated clusters containing more than five erroneous vectors are eliminated. These validation procedures collectively result in the rejection of fewer than

$^{-1}$

are discarded as unphysical; (ii) a median filter removes spurious vectors whose root-mean-square magnitude exceeds twice the local neighbourhood average; and (iii) isolated clusters containing more than five erroneous vectors are eliminated. These validation procedures collectively result in the rejection of fewer than

![]() $6 \,\%$

of total vectors, with empty locations subsequently filled through interpolation using neighbouring data points. The final velocity fields have spatial resolution

$6 \,\%$

of total vectors, with empty locations subsequently filled through interpolation using neighbouring data points. The final velocity fields have spatial resolution

![]() $\Delta x = \Delta y = 0.046D$

, yielding

$\Delta x = \Delta y = 0.046D$

, yielding

![]() $4000$

instantaneous vector fields per experimental condition. These velocity measurements yield three orthogonal components

$4000$

instantaneous vector fields per experimental condition. These velocity measurements yield three orthogonal components

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $w$

corresponding to the streamwise (

$w$

corresponding to the streamwise (

![]() $x$

), transverse (

$x$

), transverse (

![]() $y$

) and cross-steam (

$y$

) and cross-steam (

![]() $z$

) directions, respectively. The magnitude of the total velocity vector is given by

$z$

) directions, respectively. The magnitude of the total velocity vector is given by

![]() $V \equiv |U(x,y,z)| = \sqrt {u^2+v^2+w^2}$

.

$V \equiv |U(x,y,z)| = \sqrt {u^2+v^2+w^2}$

.

2.4. Triple decomposition for phase-resolved analysis

Following Hussain & Reynolds (Reference Hussain and Reynolds1970), we decompose the instantaneous velocity field

![]() $U(x,y,t)$

into three components,

$U(x,y,t)$

into three components,

![]() $U(x,y,t) = \overline {U}(x,y) + \tilde {U}^\prime (x,y,\phi (t)) + U^{\prime \prime }(x,y,t)$

, where

$U(x,y,t) = \overline {U}(x,y) + \tilde {U}^\prime (x,y,\phi (t)) + U^{\prime \prime }(x,y,t)$

, where

![]() $\overline {U}(x,y) = (\overline {u},\overline {v})$

denotes the time-averaged mean,

$\overline {U}(x,y) = (\overline {u},\overline {v})$

denotes the time-averaged mean,

![]() $\tilde {U}^\prime (x,y,\phi (t))$

denotes phase-coherent fluctuations,

$\tilde {U}^\prime (x,y,\phi (t))$

denotes phase-coherent fluctuations,

![]() $U^{\prime \prime }(x,y,t)$

denotes phase-incoherent random fluctuations, and

$U^{\prime \prime }(x,y,t)$

denotes phase-incoherent random fluctuations, and

![]() $\phi (t)$

is the instantaneous phase of the periodic fluctuations. The phase-averaged velocity field, computed as

$\phi (t)$

is the instantaneous phase of the periodic fluctuations. The phase-averaged velocity field, computed as

![]() $U^{\!p}(x,y,\phi (t))= \overline {U}(x,y)+\tilde {U}^\prime (x,y,\phi (t))$

, isolates the coherent structures associated with the global mode while suppressing phase jitter induced by small-scale turbulence. This approach effectively highlights the dominant phase-locked dynamics in the near field of the jet. While phase-averaged fields are readily obtained for purely periodic oscillations, complexities arise under quasi-periodicity where the jet evolves at multiple incommensurate frequencies. Phase identification can be achieved through external reference signals (synchronised pressure or HWA measurements) or signals extracted from velocity fields (Perrin et al. Reference Perrin, Braza, Cid, Cazin, Barthet, Sevrain, Mockett and Thiele2007). External methods provide localised phase information but suffer from sensitivity to phase jitter and require prior knowledge for optimal probe placement (Pan, Wang & Wang Reference Pan, Wang and Wang2013). Conversely, internal flow-based methods use the global flow features, including cross-correlation techniques (Konstantinidis, Balabani & Yianneskis Reference Konstantinidis, Balabani and Yianneskis2005), pattern recognition (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Lee, Yoon, Boo and Chun2002) and proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) (Van Oudheusden et al. Reference Van Oudheusden, Scarano, Van Hinsberg and Watt2005), all of which enable robust phase extraction in flows exhibiting complex spatiotemporal dynamics.

$U^{\!p}(x,y,\phi (t))= \overline {U}(x,y)+\tilde {U}^\prime (x,y,\phi (t))$

, isolates the coherent structures associated with the global mode while suppressing phase jitter induced by small-scale turbulence. This approach effectively highlights the dominant phase-locked dynamics in the near field of the jet. While phase-averaged fields are readily obtained for purely periodic oscillations, complexities arise under quasi-periodicity where the jet evolves at multiple incommensurate frequencies. Phase identification can be achieved through external reference signals (synchronised pressure or HWA measurements) or signals extracted from velocity fields (Perrin et al. Reference Perrin, Braza, Cid, Cazin, Barthet, Sevrain, Mockett and Thiele2007). External methods provide localised phase information but suffer from sensitivity to phase jitter and require prior knowledge for optimal probe placement (Pan, Wang & Wang Reference Pan, Wang and Wang2013). Conversely, internal flow-based methods use the global flow features, including cross-correlation techniques (Konstantinidis, Balabani & Yianneskis Reference Konstantinidis, Balabani and Yianneskis2005), pattern recognition (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Lee, Yoon, Boo and Chun2002) and proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) (Van Oudheusden et al. Reference Van Oudheusden, Scarano, Van Hinsberg and Watt2005), all of which enable robust phase extraction in flows exhibiting complex spatiotemporal dynamics.

In the present study, phase averaging is performed using a global phase identification method based on POD analysis. This approach leverages the entire spatial velocity field, reducing the sensitivity to phase jitter and small-scale fluctuations compared to localised reference methods (Van Oudheusden et al. Reference Van Oudheusden, Scarano, Van Hinsberg and Watt2005; Stöhr et al. Reference Stöhr, Sadanandan and Meier2011). The first two POD modes capture the majority of the kinetic energy and characterise the dominant coherent structures, enabling robust phase identification (Oberleithner et al. Reference Oberleithner, Sieber, Nayeri, Paschereit, Petz, Hege, Noack and Wygnanski2011). Snapshot POD analysis is performed on the complete dataset of

![]() $N = 4000$

instantaneous velocity fields, yielding temporal coefficients

$N = 4000$

instantaneous velocity fields, yielding temporal coefficients

![]() $a_i(t)$

for each mode (see Appendix A for details). The phase angle

$a_i(t)$

for each mode (see Appendix A for details). The phase angle

![]() $\phi _i$

for each snapshot is determined by expressing the temporal coefficients of the first two POD modes as

$\phi _i$

for each snapshot is determined by expressing the temporal coefficients of the first two POD modes as

![]() $a_1^i = r_i\sin (\phi _i)$

and

$a_1^i = r_i\sin (\phi _i)$

and

![]() $a_2^i(t) = r_i\cos (\phi _i)$

, from which the phase angle is computed as

$a_2^i(t) = r_i\cos (\phi _i)$

, from which the phase angle is computed as

![]() $\phi _i =\tan ^{-1}(a_1^i/a_2^i)$

. Based on the computed phase angles, the velocity fields are sorted into seven evenly spaced phase bins spanning a complete oscillation cycle. These phase-averaged fields are obtained by ensemble-averaging the velocity fields within each bin, reconstructing the dominant phase-locked jet dynamics.

$\phi _i =\tan ^{-1}(a_1^i/a_2^i)$

. Based on the computed phase angles, the velocity fields are sorted into seven evenly spaced phase bins spanning a complete oscillation cycle. These phase-averaged fields are obtained by ensemble-averaging the velocity fields within each bin, reconstructing the dominant phase-locked jet dynamics.

2.5. Vorticity field and vortex tracking

The out-of-plane vorticity component (

![]() $\omega _z$

) is computed from phase-averaged velocity fields acquired in the

$\omega _z$

) is computed from phase-averaged velocity fields acquired in the

![]() $x{-}y$

plane:

$x{-}y$

plane:

![]() $\omega _z = {\partial v}/{\partial x } - {\partial u}/{\partial y }$

, where

$\omega _z = {\partial v}/{\partial x } - {\partial u}/{\partial y }$

, where

![]() $u$

and

$u$

and

![]() $v$

are the axial and transverse velocity components, respectively. The required spatial derivatives are computed using a second-order accurate least squares finite-difference scheme (Raffel et al. Reference Raffel, Willert, Scarano, Kähler, Wereley and Kompenhans2018):

$v$

are the axial and transverse velocity components, respectively. The required spatial derivatives are computed using a second-order accurate least squares finite-difference scheme (Raffel et al. Reference Raffel, Willert, Scarano, Kähler, Wereley and Kompenhans2018):

The resulting vorticity field is non-dimensionalised as

![]() $\omega _z^* \equiv \omega _z D/V_e$

, where

$\omega _z^* \equiv \omega _z D/V_e$

, where

![]() $V_e$

is the exit velocity at the nozzle lip. Although the vorticity magnitude provides a measure of local fluid rotation, it cannot inherently distinguish between coherent vortical structures and regions dominated by strong shear. To address this limitation, we identify vortical structures using the

$V_e$

is the exit velocity at the nozzle lip. Although the vorticity magnitude provides a measure of local fluid rotation, it cannot inherently distinguish between coherent vortical structures and regions dominated by strong shear. To address this limitation, we identify vortical structures using the

![]() $\lambda _2$

criterion (Jeong & Hussain Reference Jeong and Hussain1995), which isolates regions of high vorticity concentration indicative of vortices – which are bounded regions of vorticity in a flow where the vortex lines form closed loops (Lim & Nickels Reference Lim and Nickels1995) – from those arising from strong shear. The algorithm computes the eigenvalues of the symmetric tensor

$\lambda _2$

criterion (Jeong & Hussain Reference Jeong and Hussain1995), which isolates regions of high vorticity concentration indicative of vortices – which are bounded regions of vorticity in a flow where the vortex lines form closed loops (Lim & Nickels Reference Lim and Nickels1995) – from those arising from strong shear. The algorithm computes the eigenvalues of the symmetric tensor

![]() $S^2 + \varOmega ^2$

, where

$S^2 + \varOmega ^2$

, where

![]() $S_\textit{ij} = ({1}/{2})(\partial u_i/\partial x_{\!j} + \partial u_{\!j}/\partial x_i)$

and

$S_\textit{ij} = ({1}/{2})(\partial u_i/\partial x_{\!j} + \partial u_{\!j}/\partial x_i)$

and

![]() $\varOmega _\textit{ij} = ({1}/{2})(\partial u_i/\partial x_{\!j} - \partial u_{\!j}/\partial x_i)$

are the symmetric and antisymmetric components of the velocity gradient tensor, respectively. After sorting the eigenvalues (

$\varOmega _\textit{ij} = ({1}/{2})(\partial u_i/\partial x_{\!j} - \partial u_{\!j}/\partial x_i)$

are the symmetric and antisymmetric components of the velocity gradient tensor, respectively. After sorting the eigenvalues (

![]() $\lambda _1 \geqslant \lambda _2 \geqslant \lambda _3$

) by magnitude, we identify the vortical structures as connected regions where

$\lambda _1 \geqslant \lambda _2 \geqslant \lambda _3$

) by magnitude, we identify the vortical structures as connected regions where

![]() $\lambda _2 \lt 0$

. This criterion effectively isolates coherent vortical structures from background shear, providing the foundation for subsequent tracking analysis.

$\lambda _2 \lt 0$

. This criterion effectively isolates coherent vortical structures from background shear, providing the foundation for subsequent tracking analysis.

Besides tracking vortex positions, quantifying their strength provides crucial insight into how external forcing affects vortex formation and evolution. The strength of evolving vortices is quantified via circulation analysis, as per Gharib, Rambod & Shariff (Reference Gharib, Rambod and Shariff1998). This analysis enables the identification of pinch-off timing – when vortical structures cease entraining vorticity from the shear layers – and comparison of the vortex strength across different forcing conditions. The dimensionless circulation is computed by integrating the vorticity above a threshold value

![]() $|\omega _{z}|^{*}\geqslant 1$

contained in the region of interest at each time step:

$|\omega _{z}|^{*}\geqslant 1$

contained in the region of interest at each time step:

where the integration domain

![]() $S$

encompasses the bounded vortex region at each time step.

$S$

encompasses the bounded vortex region at each time step.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Jet response en route to forced synchronisation

We begin by examining the response of a globally unstable jet as it approaches synchronisation under axial and transverse forcing. We apply time-periodic acoustic forcing at a frequency close to the natural global frequency (

![]() $f_{\!f}/f_n = 1.09$

), with the forcing amplitude

$f_{\!f}/f_n = 1.09$

), with the forcing amplitude

![]() $A_{\!f}$

systematically varying across five different values. We quantify the response amplitude through

$A_{\!f}$

systematically varying across five different values. We quantify the response amplitude through

![]() $V^\prime _{\textit{rms}}$

, the root mean square of the fluctuating velocity magnitude

$V^\prime _{\textit{rms}}$

, the root mean square of the fluctuating velocity magnitude

![]() $V^\prime \equiv V-\overline {V}$

, evaluated within the jet potential core. To characterise synchronisation, we examine the relative amplitudes of the PSD peaks at

$V^\prime \equiv V-\overline {V}$

, evaluated within the jet potential core. To characterise synchronisation, we examine the relative amplitudes of the PSD peaks at

![]() $f_{\!f}$

and

$f_{\!f}$

and

![]() $f_n$

as the forcing strengthens. We identify the onset of synchronisation when the spectral peak at

$f_n$

as the forcing strengthens. We identify the onset of synchronisation when the spectral peak at

![]() $f_n$

disappears and the spectral peak at

$f_n$

disappears and the spectral peak at

![]() $f_{\!f}$

becomes dominant. This spectral signature provides a robust indicator of phase-locked limit-cycle oscillations, indicating forced synchronisation.

$f_{\!f}$

becomes dominant. This spectral signature provides a robust indicator of phase-locked limit-cycle oscillations, indicating forced synchronisation.

3.1.1. Forced response to transverse forcing

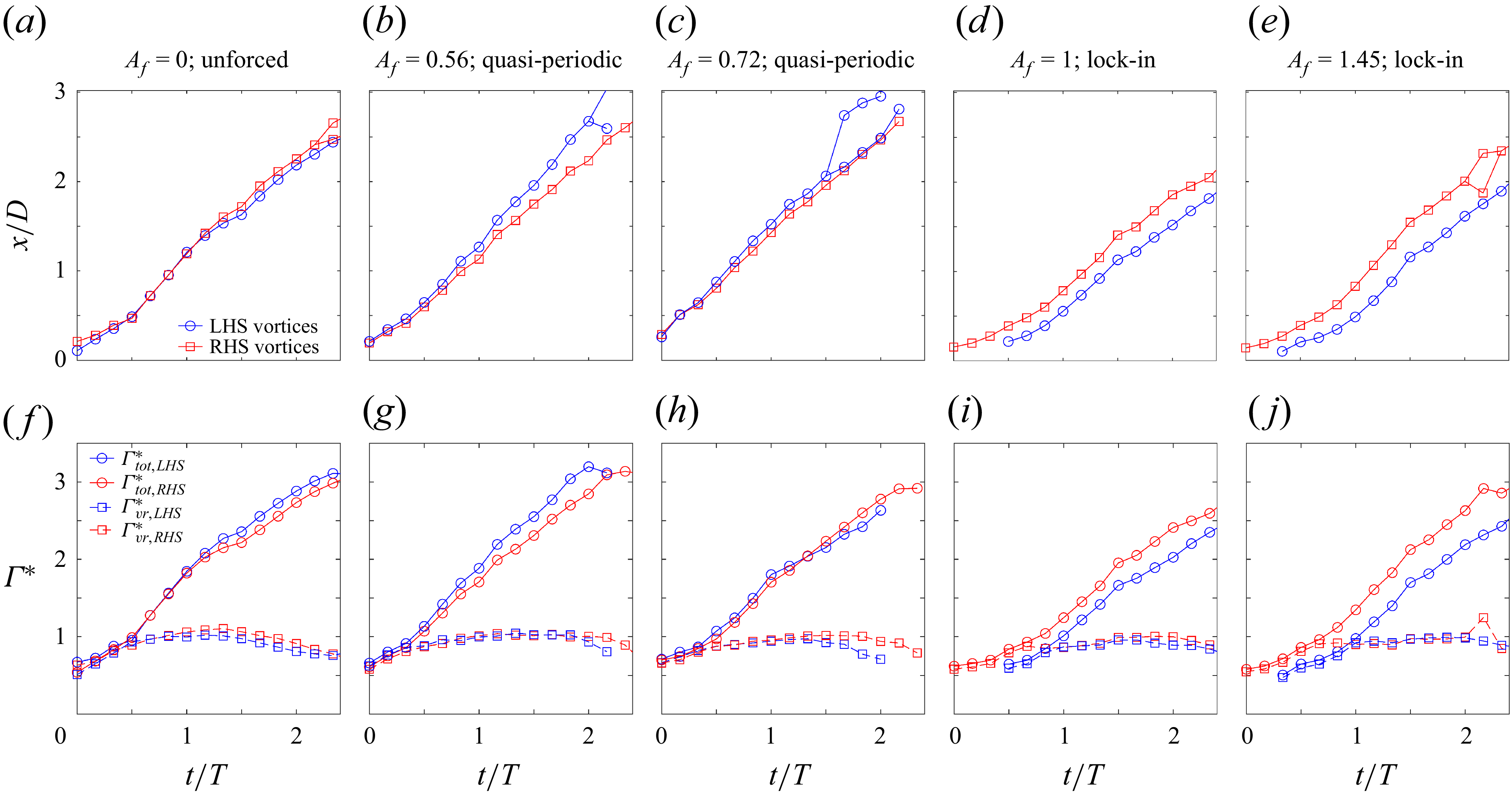

Figures 3(a–e) show spatial maps of

![]() $V^\prime _{\textit{rms}}$

for the jet when forced transversely at five different amplitudes. The black line marks the potential core boundary, defined as the region where the mean velocity

$V^\prime _{\textit{rms}}$

for the jet when forced transversely at five different amplitudes. The black line marks the potential core boundary, defined as the region where the mean velocity

![]() $\overline {V}$

exceeds

$\overline {V}$

exceeds

![]() $95\,\%$

of its value at the nozzle outlet centreline.

$95\,\%$

of its value at the nozzle outlet centreline.

Figure 3. Spatial maps of (a–e) the velocity fluctuations and (f–j) their spectra for a globally unstable jet forced transversely at

![]() $f_{\!f}/f_n=1.09$

. Root mean square velocity fluctuations

$f_{\!f}/f_n=1.09$

. Root mean square velocity fluctuations

![]() $V_{\textit{rms}}^\prime$

for five forcing amplitudes: (a) unforced, (b) low-amplitude forcing, (c) moderate-amplitude forcing, (d) critical amplitude at lock-in, and (e) above the lock-in threshold. (f–j) The PSDs of the centreline velocity fluctuations (

$V_{\textit{rms}}^\prime$

for five forcing amplitudes: (a) unforced, (b) low-amplitude forcing, (c) moderate-amplitude forcing, (d) critical amplitude at lock-in, and (e) above the lock-in threshold. (f–j) The PSDs of the centreline velocity fluctuations (

![]() $V_{c}^\prime$

) along

$V_{c}^\prime$

) along

![]() $x/D$

for the corresponding forcing conditions. The unforced jet (a, f) exhibits strong periodic oscillations at a well-defined natural frequency (

$x/D$

for the corresponding forcing conditions. The unforced jet (a, f) exhibits strong periodic oscillations at a well-defined natural frequency (

![]() $f_n$

). Below lock-in, asynchronous oscillations occur with spectral broadening around

$f_n$

). Below lock-in, asynchronous oscillations occur with spectral broadening around

![]() $f_{\!f} /f_n = 1$

in the PSD in (g,h), and the oscillation amplitudes gradually decrease with

$f_{\!f} /f_n = 1$

in the PSD in (g,h), and the oscillation amplitudes gradually decrease with

![]() $A_{\!f}$

in (b,c). At lock-in and beyond, the jet is synchronised to

$A_{\!f}$

in (b,c). At lock-in and beyond, the jet is synchronised to

![]() $f_{\!f}$

in (i,j), with a substantial drop in its oscillation amplitude in (d,e).

$f_{\!f}$

in (i,j), with a substantial drop in its oscillation amplitude in (d,e).

The unforced jet exhibits low-amplitude oscillations at the nozzle outlet (

![]() $x/D \approx 0$

). With downstream development, the jet amplitude

$x/D \approx 0$

). With downstream development, the jet amplitude

![]() $V^\prime _{\textit{rms}}$

grows and reaches a local peak within the potential core at

$V^\prime _{\textit{rms}}$

grows and reaches a local peak within the potential core at

![]() $1 \lt x/D \lt 2$

, as seen in figure 3(a). The corresponding PSD (figure 3

f) shows the fundamental frequency of the natural global mode (

$1 \lt x/D \lt 2$

, as seen in figure 3(a). The corresponding PSD (figure 3

f) shows the fundamental frequency of the natural global mode (

![]() $f_n$

) as the dominant spectral feature, evidenced by a sharp peak at

$f_n$

) as the dominant spectral feature, evidenced by a sharp peak at

![]() $f_n$

. Farther downstream (

$f_n$

. Farther downstream (

![]() $x/D \gt 2.3$

), a dominant spectral peak emerges at

$x/D \gt 2.3$

), a dominant spectral peak emerges at

![]() $f_n/2$

. This subharmonic dominance coincides with large

$f_n/2$

. This subharmonic dominance coincides with large

![]() $V_{\textit{rms}}^\prime$

values outside the potential core, typically associated with vortex pairing (Kyle & Sreenivasan Reference Kyle and Sreenivasan1993).

$V_{\textit{rms}}^\prime$