Introduction

Ethnicity is one of the largest cleavages in British voting behaviour. Ethnic minority groups are overwhelmingly likely to vote for Labour and particularly unlikely to vote for the Conservative Party (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Fisher, Rosenblatt, Sanders and Sobolewska2013). At the same time, after decades of almost no gender differences in vote choice, since the 2017 general election, women have been more likely to vote for Labour and men for the Conservatives (Campbell and Shorrocks Reference Campbell and Shorrocks2021), a shift linked to both austerity policies and Brexit. Despite the importance of both ethnic and gender cleavages to recent electoral outcomes in Britain, they have so far been studied in isolation from each other. In this letter, we use data from Understanding Society informed by intersectional approaches (for example, Hancock Reference Hancock2007) to analyse gender vote gaps among ethnic minority voters in Britain.

Whether gender intersects with ethnicity in political behaviour matters for three reasons. Firstly, the study of either ethnic minorities or women voters should avoid homogenising either group. Secondly, parties like Labour, whose electoral support comes disproportionately from women and ethnic minorities, can better understand their electoral coalition if they appreciate that many voters belong to both these groups. Thirdly, both ethnic minorities and women (and women from ethnic minorities) are under-represented in political institutions, which has ramifications for the possibility of substantive and symbolic representation if there are gender by ethnicity political cleavages.

Studies in the USA and Canada have demonstrated that women from African-American, Latina, and Indigenous backgrounds tend to be more supportive of parties of the left than men of their ethnic group or White women (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014; Harell and Panagos Reference Harell and Panagos2010; Philpot Reference Philpot2018). However, this approach to understanding voting behaviour informed by intersectional perspectives has rarely been applied in other post-industrial democracies with majority White populations. Britain is a useful case to expand our knowledge; ethnic minority participation in elections is high and electorally consequential (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Fisher, Rosenblatt, Sanders and Sobolewska2013). For example, despite an overall disastrous result in 2019, Labour still won 90 per cent of the fifty-eight seats in 2019, where at least half of residents belonged to an ethnic minority. A further advantage of this case is that there is high-quality representative data collected on ethnic minorities.

We find that among Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnicity voters, women are more supportive of Labour than men, and this gap is larger than that found among White British voters. However, we see no statistically significant gender gap for Indian, Black Caribbean, or Black African voters. Controlling for socio-economic characteristics or political attitudes (including Brexit) does not change the magnitude of this gender gap among minority voters – but reduces it to 0 among White British voters. Our findings highlight that while some minority women in Britain are particularly supportive of the left, this is not uniformly the case. This suggests we should pay more attention to the different migration, economic, and cultural characteristics of these groups to fully understand their gendered voting behaviour. In the next part of this paper, we discuss intersectional approaches and how they have been applied to electoral behaviour before outlining some key arguments supporting a general expectation that women ethnic minority voters should be more supportive of Labour than men of their ethnic group.

Ethnicity, Gender, and Vote Choice

Intersectional approaches are increasingly influential in political science, although they have been adopted unevenly across subfields. Emerging first from Black feminist scholarship in the USA (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Hill Collins Reference Hill Collins1990), intersectional approaches see social identities – like gender, race, class, sexuality, and age – as multiple and intersecting. Interactions between these social groupings, for example, between gender and race, can create categories of individuals who experience societal disadvantage, which is greater than the sum of their gender and their ethnicity. Feminist researchers have begun in recent decades to analyse political science questions – especially with respect to the descriptive and substantive representation of women – with an intersectional lens (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel and Mügge2015; Ewig Reference Ewig2018; Folke et al. Reference Folke, Freidenvall and Rickne2015; Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019). While much of this focuses on the USA, studies have also been conducted using an intersectional approach to understand representation in Bolivia (Ewig Reference Ewig2018), Sweden (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Freidenvall and Rickne2015), the Netherlands (Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019), Britain (Siow Reference Siow2023), and Germany (Abels et al. Reference Abels, Ahrens, Jenichen and Och2022). In line with the origins of intersectionality in Black feminism, the majority of this scholarship focuses on the intersection between gender and race.

The application of intersectionality to political behaviour has been comparatively limited. In the USA, scholars have pointed out that women voters are highly divided by race, with Black women in particular much more supportive of the Democrats than White women. Philpot (Reference Philpot2018) emphasizes the political marginalization of Black women to explain their high Democratic support, as well as how Obama’s election raised the salience of race, mobilizing African American women but also drawing White men towards the Republican Party in higher numbers. Similarly, Bejarano (Reference Bejarano2014) finds that Latinas born in the USA are more liberal and supportive of the Democrats than Latinos or first-generation Latinas, which she interprets as supporting Inglehart and Norris’ ‘developmental’ theory of the gender gap (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2000), where younger women in post-industrial democracies become more supportive of the left.

A handful of studies examine the interaction of race and gender in electoral behaviour outside the USA. For example, Harell and Panagos (Reference Harell and Panagos2010) found that Indigenous women in Canada were more supportive of the New Democratic Party than Indigenous men. They locate this difference in gendered experiences of colonialism and anti-colonial struggles. This mirrors Philpott’s argument in the US that the interaction between gender and race creates politically marginalized groups of women from ethnic minority backgrounds who strongly support the left. Others have studied the political participation of ethnic minority groups in Canada (Harell Reference Harell2017) and gender-affinity voting among Muslim voters in Belgium (Azabar and Thijssen Reference Azabar and Thijssen2022). In the British case, however, studies have investigated the intersection of gender with age/generation and education (Campbell and Shorrocks Reference Campbell and Shorrocks2021; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Pattie, Jones and Manley2020; Sanders and Shorrocks Reference Sanders and Shorrocks2019), but there remains a lacuna in our understanding of how gender differences in vote choice compare across different ethnic groups.

This is an important gap given the strength of ethnicity as a voting cleavage in Britain and the emergence of a gender vote gap in recent elections; Labour’s electoral coalition in 2019 relied on younger women voters and ethnic minorities, but the extent to which these categories overlap is surely crucial for understanding the likely political demands of each intersecting group of voters. We thus examine, in this letter, the gender gaps in vote choice for the five largest ethnic minority groups in the British context: Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black African, and Black Caribbean. These ethnic groups are long established in the UK, initially due to post-war labour shortages and post-colonial migration, followed by later family reunification and continued present-day migration. We are informed by intersectional approaches, which encourage researchers to analyse categories of difference in conjunction rather than separately. In particular, we follow Hancock (Reference Hancock2007) and see the relationship between gender and ethnicity as an ‘open empirical question’ (Hancock Reference Hancock2007, 251), appreciate diversity within gender and ethnic groups, and acknowledge that both the individual and institutional levels are important for understanding categories of difference and within-group diversity. With this third element in mind, we now describe the British context and the elements which may be important for shaping gender gaps within these five ethnic groups.

The British Context

Since 2015, young women in Britain have been more likely to vote for Labour than young men or older men and women, and from 2017, this became an aggregate-level gender gap where women have been more supportive of Labour and less supportive of the Conservatives than men (Campbell and Shorrocks Reference Campbell and Shorrocks2021). The gender gap among younger age groups in 2015 and 2017 has been attributed to women’s greater concern for their financial situation, the country’s economic situation, and the state of public services under the governing Conservative Party (Sanders and Shorrocks Reference Sanders and Shorrocks2019), whereas in the 2019 election it was particularly associated with Brexit (Campbell and Shorrocks Reference Campbell and Shorrocks2021).

Ethnic minority voters have been particularly likely to vote for the Labour Party since at least the 1980s, and this pattern was sustained in 2017 and 2019 (Martin and Sobolewska Reference Martin and Sobolewska2023). According to Understanding Society data, 85–92 per cent of voters from Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Black Caribbean or Black African ethnic groups voted for Labour in 2017 or 2019, and only 6–13 per cent for the Conservatives. Even among Indian ethnicity voters – seen as more pro-Conservative due to rising affluence – just over a third (36 per cent) voted Conservative in 2019, but half (53 per cent) voted for Labour. It follows that women from ethnic minority groups are substantially more likely to vote Labour compared to both White women and men, but we further expect that they should be more likely to vote Labour (rather than Conservative) when compared to men of their ethnic group. Ethnic minority women, especially British Bangladeshis and Pakistanis, are more likely to be in poverty, unemployed, or in households with dependent children compared to White women, and they have been disproportionately affected by austerity policies enacted by the Conservatives since 2010, even when compared to men of their ethnic group. (Bassel and Emejulu Reference Bassel and Emejulu2017; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Mcintosh, Neitzert, Pottinger, Sandhu, Stephenson, Reed, Taylor and Reed2017; Nandi and Platt Reference Nandi and Platt2010). Given the association between financial concerns and gender gaps in vote choice in recent elections, this leads us to expect ethnic minority women to be more supportive of Labour than ethnic minority men.

Gendered ethnic discrimination may also motivate gender gaps among ethnic minority voters. Voting for Labour among ethnic minorities is associated with perceiving discrimination against ethnic minorities, as Labour is seen as the party that has done the most to fight racial discrimination in Britain (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Fisher, Rosenblatt, Sanders and Sobolewska2013). Research has suggested that Muslim women who wear a hijab may experience greater discrimination (Mason-Bish and Zempi Reference Mason-Bish and Zempi2018), and so this might increase their support for Labour relative to men of their ethnic group. For reasons related to economic vulnerability and experiences of racism, we therefore expect women across the main ethnic minority groups in Britain to be more supportive of Labour and less supportive of the Conservatives than men of the same ethnicity. This is the main expectation we test in our analysis below.

Britain is a good case in which to consider ethnic gender gaps in vote choice. Due to high voter eligibility (through either UK or Commonwealth citizenship) and residential concentration in urban areas, ethnic minority voters are a key electoral constituency for the Labour Party. The five main ethnic minority groups studied here have their origins in post-colonial labour and family reunification migration to the UK, as well as refugee and later waves of migration (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Fisher, Rosenblatt, Sanders and Sobolewska2013). Small gaps in electoral participation notwithstanding, around one in ten voters in 2017 were from one of the five ethnic groups studied here (Martin and Khan Reference Martin and Khan2019). However, these voters are much more important for Labour, making up around one in five of their 2017 voters, compared to one in twenty of the Conservatives (Martin and Khan Reference Martin and Khan2019). Historically, this has been attributed to the Conservative’s position as the more ethnocentric and anti-immigration party, although slightly greater support for the Conservatives among British Indian voters points to potentially greater voter fragmentation than this picture allows (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Fisher, Rosenblatt, Sanders and Sobolewska2013).

A final point on the British context is that attitudes towards Brexit were particularly relevant for vote choice in the 2019 election. In studies of White voters, younger women were less Eurosceptic and less supportive of Leave than young men (Fowler Reference Fowler2022), and women were less supportive of a ‘hard’ Brexit than men (Campbell and Shorrocks Reference Campbell and Shorrocks2021), leading to some of the observed gender gap in that election. However, while a substantial minority of ethnic minority voters supported Brexit, they remained very unsupportive of the Conservatives in 2019, suggesting a smaller ‘Brexit realignment’ among ethnic minority voters than among White voters (Martin and Sobolewska Reference Martin and Sobolewska2023). Moreover, we do not have evidence or a convincing theory suggesting that there was a gender gap in Brexit preferences among ethnic minority voters specifically. As a result, it is unclear what this context will mean for gender gaps in vote choice among ethnic minority voters.

Data and Methods

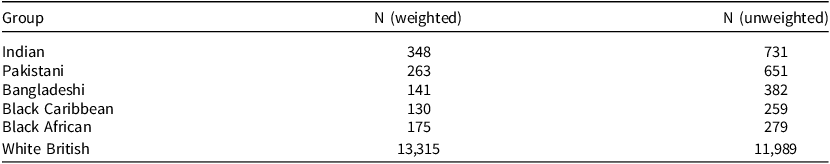

We use Understanding Society, a large household panel study in the UK. The study uses a representative probability-based sample and includes ethnic minority respondents from areas of both high and low ethnic minority density through two specific boost samples. Data is collected on vote choice after general elections, and after the 2019 election a broader set of political questions were included. For this reason, we focus on the 2019 election. The sample size per group is given in Table 1 below. These numbers reflect the number of observations where a respondent voted for either Labour or the Conservatives in 2019.

Table 1. Sample size, Labour or Conservative voters only

Our dependent variable is vote choice. We first describe the gender gap in Labour voting within each ethnic group. Results are weighted. We then model Labour vote choice for each ethnic group individually, compared to Conservative, using bivariate logistic regression, with the independent variable of respondent gender.Footnote 1 Next, we add a series of socio-economic variables to the model, and, finally, we include political attitudes. This approach allows us to explore whether observed differences in these characteristics change the size of the gender gap that we observe (or not) within each group. We include economic values, social liberal-authoritarian values, attitudes towards immigration, and support for Brexit in this final model. These attitudes have been shown to be important for vote choice in recent British elections. Socio-economic control variables are: age, country of birth (UK/elsewhere), education level, economic activity, marital status, number of children, household poverty status, housing tenure, and region (London/elsewhere). Since this is the first analysis of gender gaps within ethnic minorities in Britain, we do not have strong expectations about how these variables are associated with gender gaps within ethnic groups, and our analysis here is exploratory.

Results

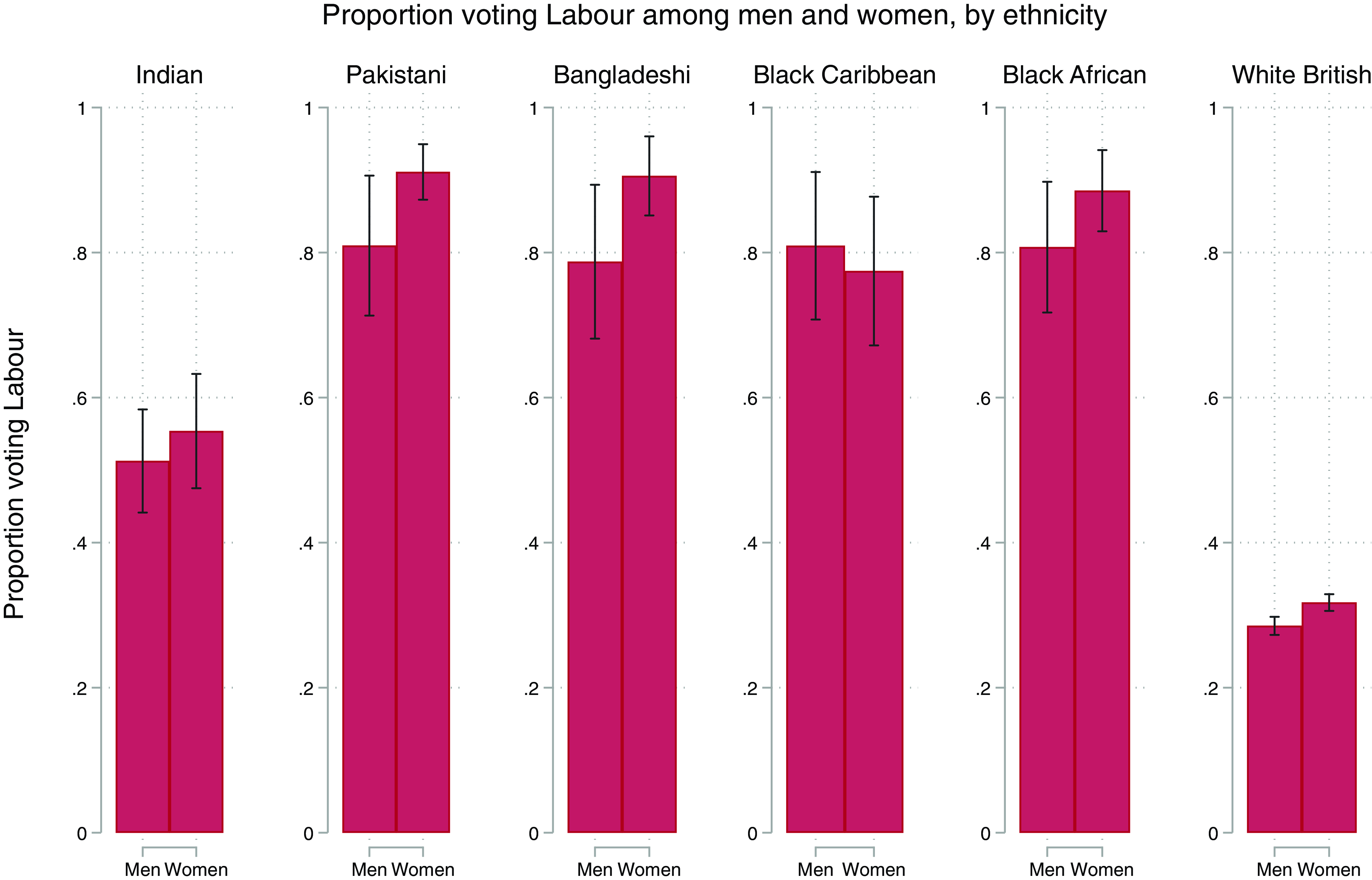

Are there gender gaps in Labour support among different ethnic minority groups? Figure 1 shows the proportion of men and women in each ethnic group that voted for Labour in the 2019 general election. We can see that women are indeed more likely than men in the same ethnic group to vote for Labour: Pakistani (91 per cent of women v. 81 per cent of men), Bangladeshi (91 per cent of women v. 79 per cent of men) and White British (32 per cent of women v. 29 per cent of men) ethnic groups; all other differences between men and women are not statistically significant.Footnote 2 We also note, though, that the gender gap in all ethnic minority groups is of a comparable size to that estimated for White British voters or greater – but smaller sample sizes mean that there is much more uncertainty around the estimates for ethnic minorities.

Figure 1. Labour vote choice among men and women by ethnic group in the 2019 general election.

Base: all voters. Data: Understanding Society

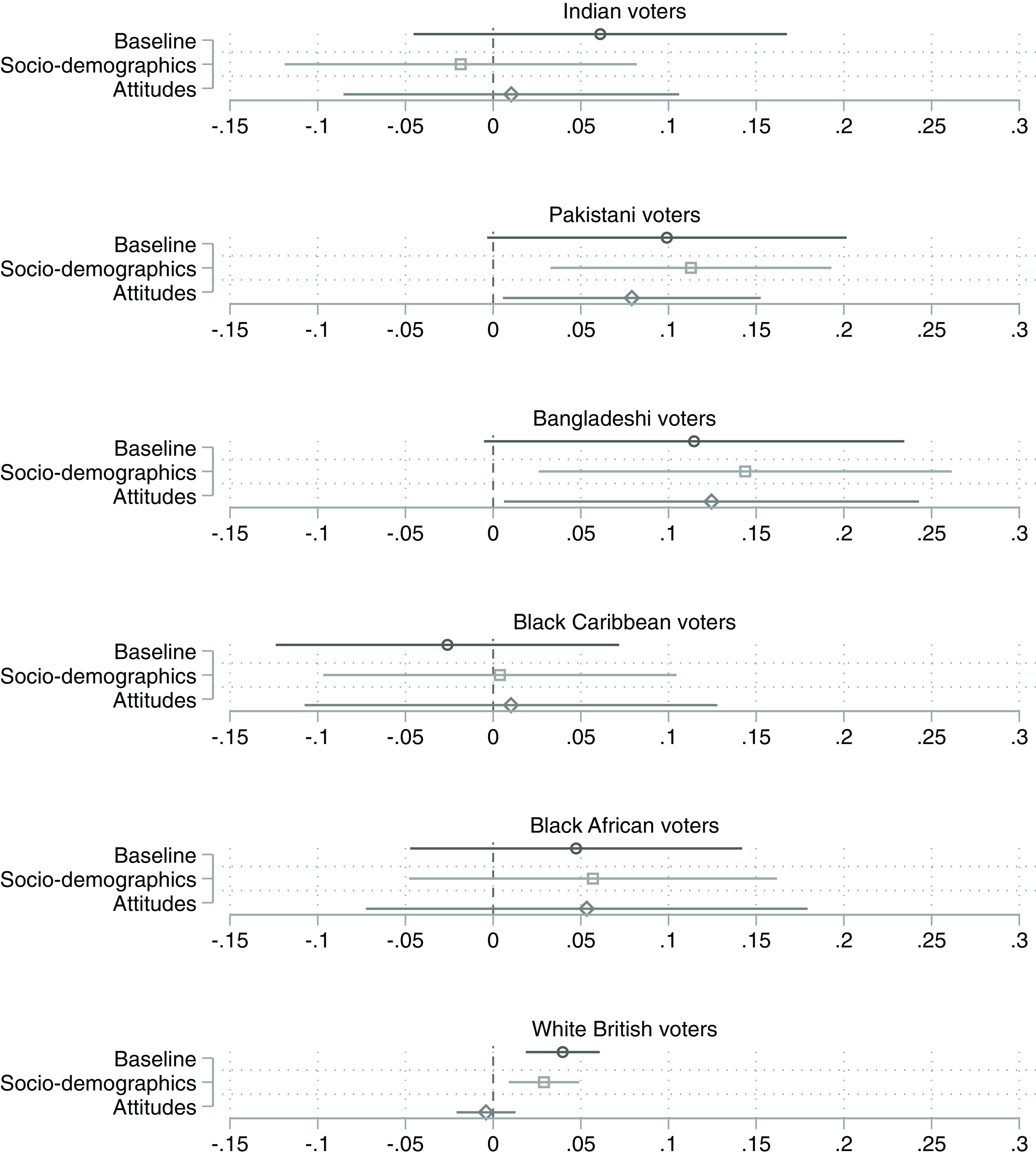

We now present the results of logistic regression models of Labour vote choice among Labour and Conservative voters for each ethnic group, which include a covariate for gender (1 = woman). The results are plotted as marginal effects in Figure 2.Footnote 3 A positive gender gap means that women are more likely than men to support Labour. The first model plots the baseline difference. The second controls for socio-demographic characteristics: age, whether the respondent was born in the UK or elsewhere, education level, economic activity, marital status, number of children, household poverty status, housing tenure, and whether the respondent lives in London or elsewhere. The third also controls for political attitudes – left-right economic attitudes, social liberal-authoritarianism, immigration attitudes, and whether the respondent thought the UK should leave the EU in 2016/17. Figure 2 displays for each ethnic group: (i) the gender gap with no controls, (ii) the gender gap controlling for socio-demographic factors, and (iii) the gender gap controlling for socio-demographic factors and political attitudes.

Figure 2. Gender gaps in Labour-Conservative vote choice in the 2019 general election, before and after controlling for socio-demographic factors and political attitudes.

Base: Labour and Conservative voters. Data: Understanding Society

For voters of Indian, Black Caribbean or Black African ethnicity, controlling for socio-demographic factors or political attitudes does not change that there is no significant gender gap in 2019. However, the positive gender gap among voters of Pakistani ethnicity remains positive (eight points) and significant when socio-demographic attributes and/or political attitudes are controlled for. This is also the case for Bangladeshi voters when only socio-demographic factors are controlled for (fourteen points) and when political attitudes are added to the model (eleven points). While including political attitudes reduces the gender gap in 2019 among White British voters to 0, these independent variables do not have the same predictive power among any ethnic minority group. This suggests that the observed gender gap is driven by other factors.

Conclusion

This letter investigated whether there are gender gaps in vote choice among the main ethnic minority groups in Great Britain. Using data from a probability-sample survey, we show that there is indeed a gender gap among Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnicity voters, with women being roughly 10 percentage points more likely to support Labour than men from the same ethnic groups. This is noteworthy for two reasons. Firstly, it is larger than the gender gap observed for White British voters in this sample. Secondly, this is observed in a group where over 80 per cent of voters already supported the Labour Party, so we might have expected ceiling effects on Labour support to limit the possibility for any gender gap. However, we did not observe a statistically significant gender gap among the other minority groups covered in this study, that is, among voters from Indian, Black Caribbean, or Black African ethnic groups.

Controlling for socio-demographic and attitudinal factors which might explain the gender gap also had no effect on the predicted size of the gender gap among the groups studied. This is particularly notable in the case of attitudinal factors since the gender gap among White voters in 2019 was associated with different Brexit preferences (Campbell and Shorrocks Reference Campbell and Shorrocks2021). This suggests that other factors may explain the gender gap – or lack of it – among ethnic minority voters. It is not possible to investigate these gender gaps further without an election study of ethnic minority voters, including specialized questions on items that are likely to matter particular to ethnic minorities like identity, racism, and within-group mobilization. We are also unable to consider participation here, as Understanding Society does not have validated turnout data. We, therefore, hope that this letter is a starting point to motivate future research on intersectional gender gaps in political behaviour in Great Britain.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425000341. Replication materials are available from the BJPS Dataverse site at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LWOHOA.

Data availability statement

Replication data can be found on the BJPS Dataverse site at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LWOHOA.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to participants in the Gender and Politics workshop at King’s College London 2019, as well as audience members at the 2019 Political Studies Association conference at the University of Nottingham, and the 2019 Elections, Public Opinion and Parties conference at the University of Strathclyde, where this work was initially presented.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Funding

This work was supported by the ESRC (ES/N00812X/1); additional funding for a 2019 General and European Elections Research Programme as part of Understanding Society: The UK Household Longitudinal Study: Waves 9-11.