Introduction

Production of food and fiber is one of the principal ways humans interact with insects. On the one hand, insect pests, such as the northern corn rootworm, Diabrotica barberi Smith & Lawrence (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), the pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), and the red sunflower seed weevil, Smicronyx fulvus LeConte (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), reduce crop yields and quality, necessitating the use of insecticides or other control measures (Pimentel et al., Reference Pimentel, Acquay, Biltonen, Rice, Silva, Nelson, Lipner, Giordano, Horowitz and D’Amore1992; Charlet, Brewer and Fanzmann, Reference Charlet, Brewer, Fanzmann, Schneiter, Bartels, Hatfield, Baenziger and Bigham1997; Edde, Reference Edde2022). On the other hand, control measures may interfere with beneficial insects, including pollinators and natural enemies (predators and parasitoids), which provide services that support agriculture (Pimentel et al., Reference Pimentel, Acquay, Biltonen, Rice, Silva, Nelson, Lipner, Giordano, Horowitz and D’Amore1992; Khalifa et al., Reference Khalifa, Elshafiey, Shetaia, El-Wahed, Algethami, Musharraf, AlAjmi, Zhao, Masry, Abdel-Daim, Halabi, Kai, Al Naggar, Bishr, Diab and El-Seedi2021). The use of integrated pest management (IPM) programs is an approach that aims (among several goals) to balance the need to limit losses from pests while conserving beneficial species in agriculture.

IPM is considered the dominant pest management paradigm in agriculture, with nations including Australia, Canada, the European Union, and the United States having national IPM initiatives (Brier et al., Reference Brier, Murray, Wilson, Nicholas, Miles, Grundy and McLennan2008; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Cass, Vincent, Olfert, Peshin and Pimentel2014; Barzman et al., Reference Barzman, Bàrberi, Birch, Boonekamp, Dachbrodt-Saaydeh, Graf, Hommel, Jensen, Kiss, Kudsk, Lamichhane, Messéan, Moonen, Ratnadass, Ricci, Sarah and Sattin2015; USDA, 2018; Barrera, Reference Barrera2020). The US government estimates suggest IPM adoption includes 70% of US cropland (USGAO, 2001). However, the USGAO (2001) report also acknowledges that adoption of IPM sometimes fails to reduce insecticide use and adoption estimates can change from greater than 70% to less than 20%, depending upon the metrics used to define IPM. Implementation of IPM could be considered complete if it creates a resilient system by employing techniques, such as biological control, crop rotation, multi-crop interactions, reduced tillage, resistant cultivars, properly timed plantings, use of selective insecticides, and application only in specific areas in addition to the use of economic thresholds (Puente, Darnall and Forkner, Reference Puente, Darnall and Forkner2011; Barzman et al., Reference Barzman, Bàrberi, Birch, Boonekamp, Dachbrodt-Saaydeh, Graf, Hommel, Jensen, Kiss, Kudsk, Lamichhane, Messéan, Moonen, Ratnadass, Ricci, Sarah and Sattin2015). At a minimum, IPM should use pest scouting, economic thresholds, crop rotations, and selective insecticides (Kogan, Reference Kogan1998). However, there is a misalignment between the IPM ideal and how IPM is practiced, with many growers considering rotating pesticides with different modes of action to be IPM (Ehler, Reference Ehler2006; Dara, Reference Dara2019). With over 67 definitions of IPM (from academia, government agencies, and NGOs, among others), it is not surprising that confusion exists as to what qualifies as IPM (Bajwa and Kogan, Reference Bajwa and Kogan2002).

Even when an IPM program is reduced to its most fundamental core, the use of scouting and economic thresholds for decision-making (Kogan, Reference Kogan1998; Dara, Reference Dara2019), implementation can be complex and tedious because of detailed methods and context-dependent factors. For example, scouting for the red sunflower seed weevil (RSSW), S. fulvus, in North American sunflowers includes recommendations that sampling should take place at least 23 meters in from the field’s edge, start at the R5 (i.e., anthesis) growth stage, continue every 4–7 days until R5.7 (i.e., the stage when 70% of florets have shed pollen; for more detailed information, see Schneiter and Miller, Reference Schneiter and Miller1981), include examination of five heads at five locations within each field, and use of DEET-based repellent to facilitate counting (Weiss and Brewer, Reference Weiss and Brewer1988; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Brewer, Charlet and Glogoza1997; Michaud, Reference Michaud2014; Varenhorst, Reference Varenhorst2021). Recommended thresholds for using insecticides against the RSSW in oilseed sunflowers generally range from 4 to 12 weevils per head (Michaud, Reference Michaud2014; Varenhorst, Reference Varenhorst2021; Manitoba, Reference Manitoba2023), but thresholds change based on the estimated crop value and cost of management.

Adding to this complexity, non-chemical management methods are often needed due to factors such as insecticide resistance, as is seen for the RSSW (Varenhorst et al., Reference Varenhorst, Wagner, Rozeboom and Knodel2020). In the case of RSSW, these practices may include tillage, early planting, selection of early-maturing hybrids, and other decisions to support natural biological control (Prasifka et al., Reference Prasifka, Marek, Lee, Thapa, Hahn and Bradshaw2016; Cluever et al., Reference Cluever, Bradshaw, Varenhorst, Knodel, Beauzay and Prasifka2025). Unfortunately, there appears to be skepticism among stakeholders as to the efficacy of early planting (JRP Pers. Obs.).

Modern agriculture is typified by large-scale operations that are heavily knowledge-dependent (Samy, Swanson and Sofranko, Reference Samy, Swanson and Sofranko2003; Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2023). For instance, the average 2022 farm size is 400, 622, 605 hectares for Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota, respectively (USDA-NASS, 2024), with some operations exceeding 20000 hectares (JRP Pers. Obs). This large scale may mean that many farmers do not have time for tasks such as scouting (Cluever, Unpublished). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that growers are not as familiar with pest identification and other facets of IPM when compared to advisors (Flint, Reference Flint2012; Archibald et al., Reference Archibald, Bradshaw, Golick, Wright and Peterson2018).

The complexity and time-consuming nature of tasks, such as pest management, encourage many growers to use crop advisors to assist with decision-making (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Luschei, Boerboom and Nowak2006; Brodt et al., Reference Brodt, Goodell, Krebill-Prather and Vargas2007; Arbuckle, Reference Arbuckle2014; Eanes et al., Reference Eanes, Singh, Bulla, Ranjan, Prokopy, Fales, Wickerham and Doran2017; Petrzelka et al., Reference Petrzelka, Ulrich-Schad, Yost and Barnett2024). In an Iowa survey, 90% of corn and soybean farmers identified crop advisors as their primary source of information (Tylka, Wintersteen and Meyer, Reference Tylka, Wintersteen and Meyer2005). This is not only so in the United States but in other countries as well. For instance, approximately half of the farmland in the UK is looked after by advisors associated with the Association of Independent Crop Consultants (UK Parliament, 2020). Similarly, in a survey of 1003 Australian farmers, Nettle et al. (Reference Nettle, Morton, McDonald, Suryana, Birch, Nyengo, Mbuli, Ayre, King, Paschen and Reichelt2021) found that 64% use fee-for-service advisors. Furthermore, so important are advisors that the European Commission issued a directive that member states are to ‘set up systems of both initial and additional training for distributors, advisors and professional users of pesticides…’ (EC, 2009).

To be a certified crop advisor (CCA) in North America, one must pass two exams, have at least 2 years of experience providing advice to growers (more if a bachelor’s degree or higher is not obtained), and abide by a code of ethics (ASA, 2023). Forty hours of continuing education are required every 2 years to maintain certification (ASA, 2023). Crop advisors may be independent or work for a consultancy company, a local cooperative, a commodity organization (e.g., dry bean processors), or an agrochemical company (Lambur, Kazmierczak and Rajotte, Reference Lambur, Kazmierczak and Rajotte1989; CCA, 2020; Dentzman, Reference Dentzman2023). Ultimately, the expertise and close relationships with growers make CCAs a potential conduit for improved IPM adoption.

Though governmental policies recognize IPM as a key method to attain specific goals (e.g., reduced pesticide use and improved environmental health), scrutiny continues to show incomplete success and areas where improvements are needed (USDA, 2018; Deguine et al., Reference Deguine, Aubertot and Flor2021). Farmer reliance on CCAs to guide crop management decisions provides one route to influence on-farm practices. However, CCAs’ willingness to use various IPM strategies or new technologies may be influenced by their professional affiliation (Eanes et al., Reference Eanes, Singh, Bulla, Ranjan, Prokopy, Fales, Wickerham and Doran2017), education (Ryan and Gross, Reference Ryan and Gross1950), or other knowledge and beliefs. Surveys are common for collecting demographic data and analyzing how experiences influence practices (Lambur et al., Reference Lambur, Kazmierczak and Rajotte1989; Dentzman, Reference Dentzman2023). To learn more about the background and perceptions of North American CCAs, a survey was distributed. Sunflower IPM was chosen as a focus of survey questions because of a recent RSSW pest outbreak caused (and able to be addressed) by on-farm choices related to pest management (Cluever et al., Reference Cluever, Bradshaw, Varenhorst, Knodel, Beauzay and Prasifka2025).

Materials and methods

A 37-question survey was created to obtain information from CCAs in three subject areas: (1) demographics and general information, (2) sources of information and outlook on alternative pest management practices (e.g., biological and cultural), and (3) sunflower IPM. Question formats were multiple choice with single entry, multiple choice with multiple entry, drop-down, and text box. The survey was created and administered in Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The timing tool was used to determine how long it took CCAs to correctly identify an RSSW from a set of four images. The North Dakota State University Institutional Review Board determined this survey to be exempt on 8 January 2024 (IRB0005012).

In 2024, links to the survey were sent via email to distribution lists of the Minnesota Independent Crop Advisors (MNICCA; 10 January), National Alliance of Independent Crop Advisors (NAICC; 10 January), Nebraska Independent Crop Consultant Association (NICCA; 10 January), the Wisconsin Association of Professional Agricultural Consultants (WAPAC; 2 February), and the Independent Agricultural Consultants of Colorado (IACC; 9 February). These were chosen as they are representative of the Midwest/Great Plains region of North America. As Dillman, Smyth and Christian (Reference Dillman, Smyth and Christian2009) recommend, reminders were sent approximately 2 weeks later for NAICC and NICCA (24 January) and MNICCA (2 February). Additionally, a quick response code was made available to attendees of the Sunflower University presentations held in Rothsay, MN, on 15 February.

Statistical analyses of data from some survey questions were limited by low frequency of responses (i.e., less than the minimum expected cell frequency for a chi-square test), leading to reporting of simple means (± standard deviation) or frequencies for categorical responses. Work habits (i.e., number of hectares scouted and time budgets) were contrasted for independent advisors and those working for a consulting company using untransformed data in SAS PROC TTEST using the Satterthwaite method (SAS Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Because respondent data on the number of hectares (acres) scouted for various crops used ranges, estimates of total hectares were approximated using the midpoint of each category except for the lowest (<101 hectares) and highest (>2024 hectares), where the indicated number was used. The self-reported IPM definitions of CCAs were analyzed by cutting and sorting responses into themes as recommended by Ryan and Bernard (Reference Ryan and Bernard2003).

Results and discussion

Demographics

Although 122 responses were received, only 114 were usable. A large share of our respondents were responsible for advising growers in the Great Plains region of North America, which is characterized by a predominance of corn and soybean (USDA-NASS, 2024; Fig. 1). Thus, it should not be surprising that corn was the most frequently scouted crop among our respondents followed by soybean, wheat, alfalfa, dry bean, and sunflower (similar to the findings of Wright, DeVries and Kamble, Reference Wright, DeVries and Kamble1997; Table 1) with each respondent stating that he/she was responsible for 5.1 (±2.1 SD) different crops (N = 113) and approximately 5914 (±2945) hectares (N = 111).

Figure 1. Number of crop advisors scouting each state (also 1 advisor in Ontario and 1 in Manitoba). AI-based software ‘RTutor2.00’ was used to compile the ‘R’ code that produced this figure.

Table 1. Size of each crop (in hectares) that respondents advised on for nine selected categories (number of respondents; N = 114)

Of the top 10 crop categories, alfalfa, sunflower, and vegetables were relatively minor crops, with an average of fewer than 405 hectares (1000 acres) scouted by each advisor (Table 1). Most of the sunflower respondents in this survey (N = 29) scouted in North Dakota (17), Minnesota (five), or Colorado (six) with few representatives from Kansas (three), Manitoba (one), Nebraska (one), and South Dakota (four); thus, results should be interpreted with caution as significant pests like RSSW are currently more problematic in South Dakota (Cluever et al., Reference Cluever, Bradshaw, Varenhorst, Knodel, Beauzay and Prasifka2025).

The distribution of years of experience for survey non-retired respondents was left-skewed. Most respondents (N = 113) had over 20 years of experience with the distribution being: 4.2% 1–5 years; 7.1% 6–10 years; 15.0% 11–15 years; 7.1% 16–20 years; 15.9% 21–25 years; 15.0% 26–30 years; and 35.4% >30 years. A similar bias to very experienced (>20 years) crop consultants was reported by Archibald et al. (Reference Archibald, Bradshaw, Golick, Wright and Peterson2018). The CCA program (CCA, 2020) reports that the median age of its members has slightly declined from 50 (2013) to 48 (2020). However, as with the farmers they advise, a high median age (58 in 2022; USDA-NASS, 2024) has implications for the future supply of crop advisors (as many may be near retirement), which is supported by a comment from one of our respondents, ‘I employ seasonal crop scouting. It is getting harder and harder to find good help…’ Fortunately, technology such as sensors, drones, and artificial intelligence may ameliorate a future shortfall of crop advisors. For instance, unmanned aerial and ground systems may be used to detect plant stress (e.g., water stress, nutrient deficiency, insect feeding, and disease presence) and weed presence (Pinter et al., Reference Pinter, Hatfield, Schepers, Barnes, Moran, Daughtry and Upchurch2003; Hassler and Baysal-Gurel, Reference Hassler and Baysal-Gurel2019; Wilson, Reference Wilson2022).

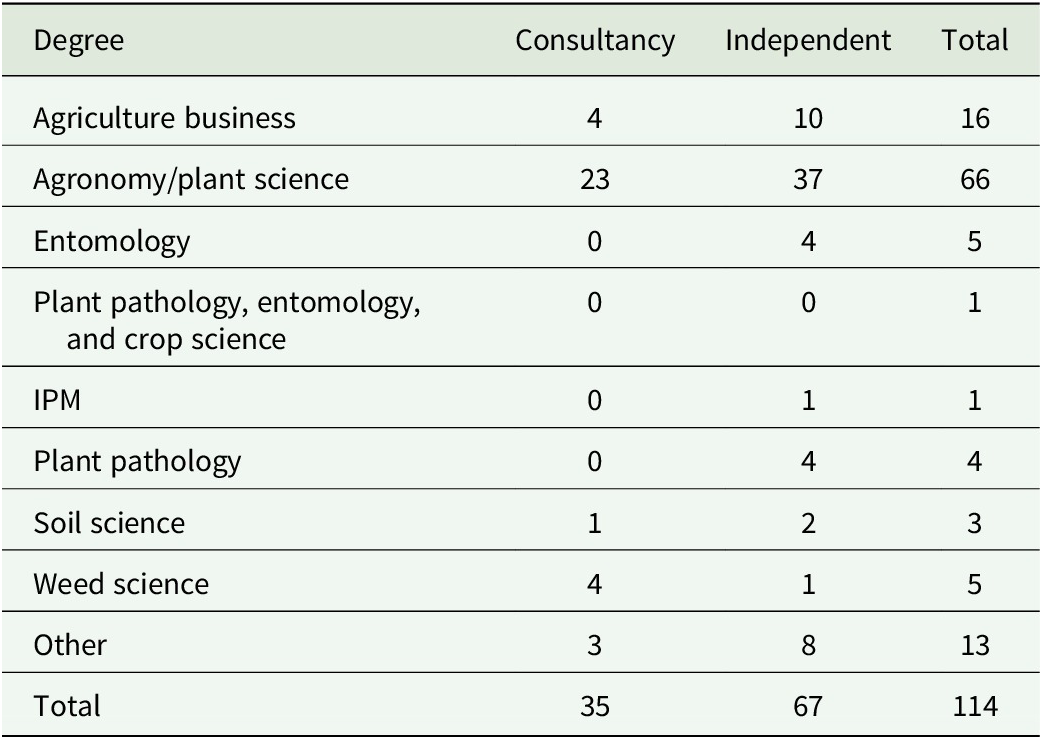

Most respondents (N = 114) had at least a bachelor’s degree (65.8%), 19.3% had a graduate degree, 9.6% had some graduate education, 3.5% had a technical degree, and 1.8% had some college. The majority (57.9%) had a degree in agronomy or plant science, and only 6.1% had a degree in entomology or IPM (Table 2). The low frequency of CCAs with entomology degrees likely reflects the fact that few (16 of 57) of the 1862 land-grant universities offer undergraduate majors in entomology (ESA, 2025).

Table 2. Self-described education (i.e., degree) of respondents

The entomological training of those who did not have a degree in entomology (N = 107) consisted of on-the-job training (82.2%) and a few college courses (79.4%). Other training (10.3%) included industry update meetings, seminars, university short courses, and life experience. Independent advisors tended to have more postbaccalaureate education (35.8%) than those working for a consultancy (8.6%), though data are insufficient for a formal analysis. Overall, while agronomy and plant science can provide a good foundation for CCA work, the low frequency of degrees in entomology or IPM suggests that some aspects of insect pest management may be a weakness for some advisors.

Unlike data collected by CCA (2020), over half (58.8%) of the respondents in our survey were independent crop advisors, which may be an artifact of the lists used to distribute this survey. The remainder were employed by a consultancy company (30.7%), a single producer (3.5%), industry (3.5%), or university extension/other (3.5%). Because of the greater representation of independent crop advisors, our respondents may be less likely to make insecticide recommendations than the broader population of CCAs, which includes more industry personnel (Ingram, Reference Ingram2008; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Nielsen, Christensen, Ørum and Martinsen2019).

Most respondents believed IPM to be very or extremely important (105 out of 110) and considered themselves very or extremely knowledgeable about IPM (93 out of 111). However, from 99 (open-ended text box) respondent definitions of IPM, a minority stressed the use of multiple tactics (45), that IPM is knowledge-based (21), or has a goal of reducing harm from pesticides (15). For instance, one respondent stated that IPM is ‘a science-based form of managing pests (including weeds, insects, pathogens, mollusks, mammals, etc) that reduced risk to envt [sic], human health, and economics’. Another said, ‘Make decisions that are beneficial for environment, productivity, and wellbeing [sic] of all people’. Seven respondents gave answers that were either meaningless or not in line with the principles of IPM. For instance, one respondent answered, ‘Reviewing alternates to improve crop health’, another stated ‘bugs, diseases, and weeds’, and yet another stated that IPM is ‘a process that has been eliminated by younger generations’. However, a sizable plurality (47) stressed the economic aspects of IPM. From the 26 responses specific to sunflower IPM, a minority of CCAs considered natural enemies to be very or extremely important (11), but over half (17) considered insect pollination in sunflower to be very or extremely important. Consequently, CCAs’ beliefs in the importance of pollinators to sunflower yields could help support the adoption of practices that would improve IPM quality.

Work habits and attitudes

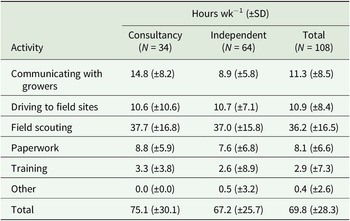

Crop advisors working for a consultancy company were responsible for more hectares than independent advisors (t = 3.31; df = 49.453; P = 0.0017), which should not be surprising as they likely have more resources (i.e., field scouts) than independent advisors. Advisors (N = 108) stated they worked at least (69.8 h ± 28.3 SD) hours per week during the field season. Most of the time was spent scouting (36.2 ± 16.5 h), driving to field sites (10.9 ± 8.4 h), and communicating with growers (Table 3), with no statistical difference between independent advisors and those working for a consultancy for total hours worked (t = 1.29; df = 59.002; P = 0.202). Additionally, there was no difference for the time spent scouting (t = 0.21; df = 64.203; P = 0.836), driving to field sites (t = −0.02; df = 49.092; P = 0.982), or training (t = 0.51; df = 92.407; P = 0.609). However, the time communicating with growers was greater for advisors employed by consultancies (14.8 ± 8.2 h compared to 8.9 ± 5.8 h for independent advisors) (t = 3.71; df = 50.747; P < 0.001). Though training and scouting can be conducted simultaneously (as can driving and communicating with growers), the large difference in time spent communicating with growers between advisors employed by consultancies and independent advisors was unexpected and may warrant further investigation.

Table 3. Time budget of respondents

Sunflower pests

Sunflower CCAs (N = 28) rated weeds (nine), birds (seven), and insects (seven) as their greatest production problems. For their second-greatest problem, advisors listed weeds (11), insects (10), and diseases (four). The focus on weeds is understandable, as weeds can dramatically decrease yields and are becoming more difficult to control. For instance, kochia, Kochia scoparia L. (Caryophyllales: Amaranthaceae), a common weed in sunflowers, can reduce yield by 61.9 kg ha−1 for every plant row-meter−1 (Durgan, Dexter and Miller, Reference Durgan, Dexter and Miller1990; Bortolon et al., Reference Bortolon, Nathew, Prasifka and Wagner2024). Additionally, herbicide resistance (e.g., Acetolactate synthase [group 2 herbicides] resistant kochia) is becoming more widespread, making adequate management more difficult (Lawrence and Beiermann, Reference Lawrence and Beiermann2018; Heap, Reference Heap2024). Herbicide drift and harvest issues (e.g., lodging) were rated among the top three by only one and three respondents, respectively. It seems possible that infrequent CCA concerns about harvest issues come from problems like lodging occurring later in the season after scouting is finished.

For insects, respondents (N = 28) consistently rated RSSW as the greatest insect problem (13), followed by the sunflower moth (Hulst) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) (five) and the banded sunflower moth, Cochylis hospes (Walsingham) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) (three). Advisors stated that the second-greatest pest was the banded sunflower moth (10), grasshoppers (seven), and RSSW (five). There was a general trend toward considering RSSW as more of a pest in the Dakotas (16 out of 19) than in Colorado and Kansas (three out of eight), though this should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample size. It should come as no surprise that the RSSW ranks among the top insect pests, as issues with management have arisen in the Dakotas (Cluever et al., Reference Cluever, Bradshaw, Varenhorst, Knodel, Beauzay and Prasifka2025). Pests like the dectes stem borer, Dectes texanus LeConte (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and the sunflower beetle, Calligrapha exclamationis (Fab.)(Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), may be considered minor pests as they were only rated among the top three by three and one advisor, respectively. Though crop advisors identified RSSW as the top sunflower insect pest, acknowledgment of several other insects as primary or secondary concerns has implications for management. Specifically, though early planting is being recommended for management of RSSW, there are several insect pests for which late planting is a suggested cultural method to reduce frequency or severity of damage (e.g., stem-boring insects [Rogers, Reference Rogers1985; Charlet et al., Reference Charlet, Aiken, Meyer and Gebre-Amlak2007] and banded sunflower moth [Oseto, Charlet and Busacca, Reference Oseto, Charlet and Busacca1989]). Thus, in areas where RSSW is severe and resistance to pyrethroid insecticides is present (Cluever et al., Reference Cluever, Bradshaw, Varenhorst, Knodel, Beauzay and Prasifka2025), early planting should be the first option to limit damage and reduce weevil populations as RSSW is likely to cause more damage than stem-boring insects or banded sunflower moth (Prasifka et al., Reference Prasifka, Varenhorst, Simons, Cluever, Wagner and Ireland2024).

Scouting

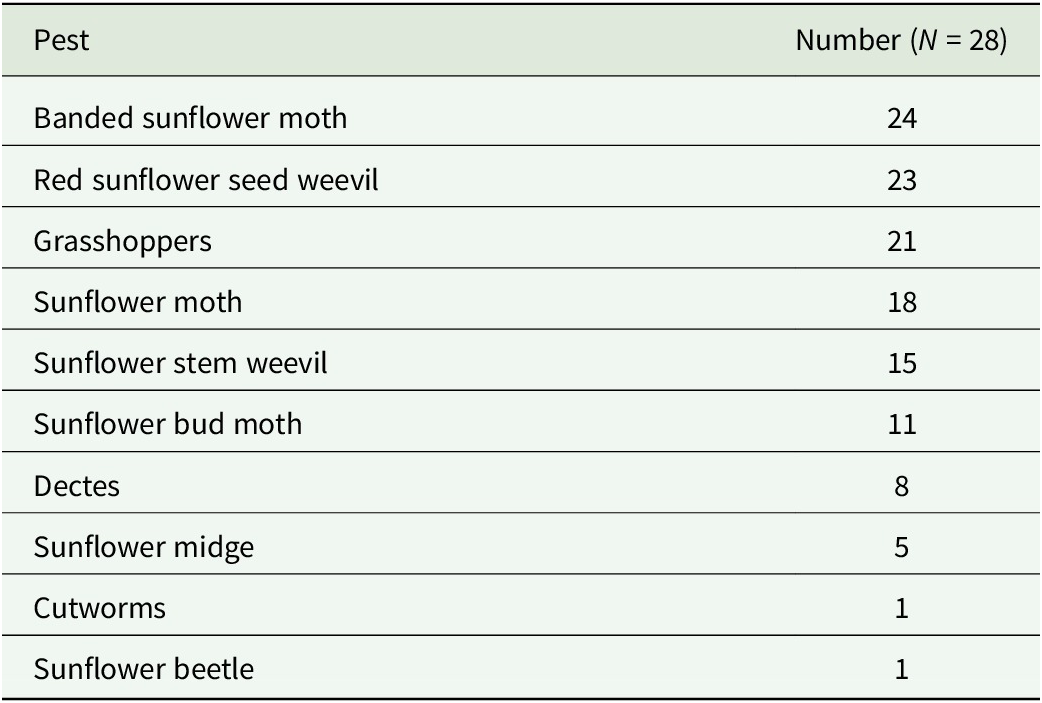

In sunflower (N = 28), advisors scouted for an average of (4.5 ± 1.6) different insect pests. The most frequently scouted pests were the banded sunflower moth, followed by RSSW, and grasshoppers (Table 4). Some of those who did not scout for RSSW indicated that ‘Red sunflower seed weevil is never an issue’ or ‘Very little problem here’. For RSSW scouting, the majority of advisors (N = 23) scouted each field, began scouting at the R4 stage and continued every 5-7 days, examined at least five heads at five locations within each field, and used a DEET-based repellent to aid in scouting (Table 5). However, only a minority (10) walked at least 23 meters into the field before scouting, which may cause the threshold to be reached artificially as RSSW tend to be more concentrated at the field edges (Charlet and Oseto, Reference Charlet and Oseto1982). One of those who did not walk at least 23 meters into the field stated that he checks the headlands of the field before going to the center, and another stated that he checks the margins and if no weevils are found, he moves to the next field. Only a few (five) took samples in an ‘x’ or ‘z’ pattern. Similarly, Archibald et al. (Reference Archibald, Bradshaw, Golick, Wright and Peterson2018) noted that crop advisors in Nebraska tended to use most of the recommended scouting practices for western bean cutworm; however, most did not use pheromone traps to time the start of scouting as is recommended (Archibald et al., Reference Archibald, Bradshaw, Golick, Wright and Peterson2018; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Difonzo, Baute, Michel and Krupke2019). Of those who scouted for RSSW (N = 23), a plurality (10) indicated that they used a threshold of 2–5 weevils per head; two advisors indicated that they recommended application regardless of population, two used a threshold of one weevil or a threshold of 6–10 weevils. Of those who indicated ‘other,’ three indicated that the timing of another pest/disease dictates application, which may indicate that there is a philosophy of ‘let us just throw it in’. This contrasts with a western bean cutworm survey where many advisors used a lower threshold than recommended (Cluever, unpublished). Three others specified that the threshold for confection is one per head, likely due to the low tolerance for injury. However, there is no threshold for confection sunflowers as contracts often dictate that confection flowers be sprayed regardless of pest pressure (Cluever et al., Reference Cluever, Bradshaw, Varenhorst, Knodel, Beauzay and Prasifka2025). Overall, crop advisors working in sunflowers showed an incomplete adoption of recommended scouting practices, suggesting that insecticide applications may be made against IPM guidelines. For instance, RSSW populations may be overestimated as they are more concentrated at field edges (Charlet and Oseto, Reference Charlet and Oseto1982).

Table 4. Sunflower insect pests scouted for by respondents

Table 5. Red sunflower seed weevil, Smicronyx fulvus, scouting practices of respondents

Competence and networks

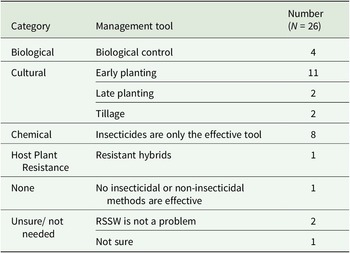

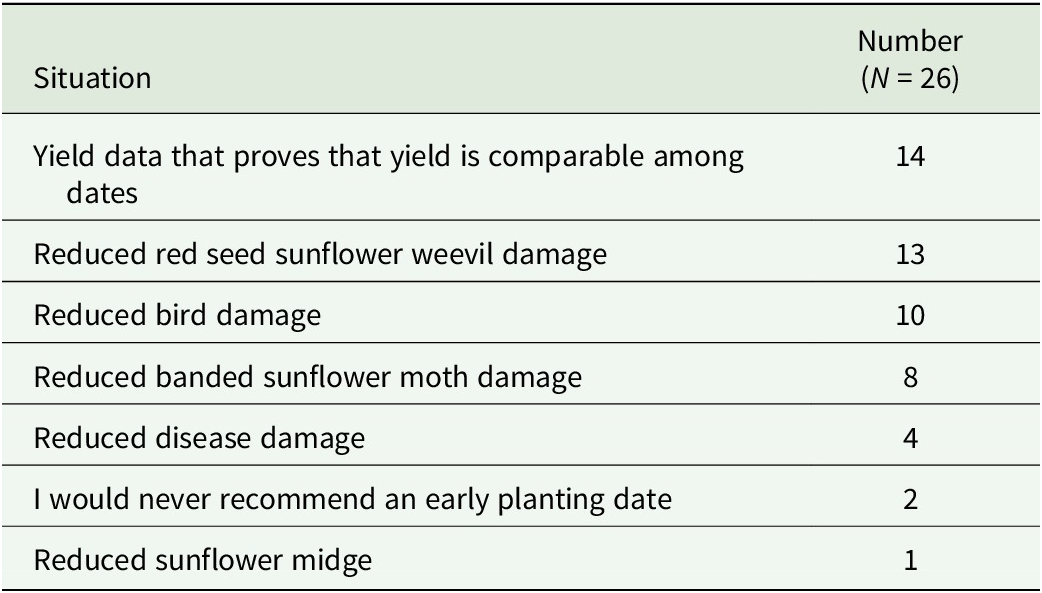

All crop advisors (N = 27) correctly identified an RSSW in (37.0 ± 37.3) seconds. This is in line with Archibald et al. (Reference Archibald, Bradshaw, Golick, Wright and Peterson2018), who found that most CCAs successfully identified the western bean cutworm, Striacosta albicosta ((Smith); Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Of 26 respondents, a plurality (11) believed that early planting is an effective means of reducing RSSW damage, eight believed insecticides were the only effective tool, and one believed there were no effective tools (Table 6). Most crop advisors (14) stated that comparable yield data would make them more likely to recommend a modified planting date, followed by reduced RSSW damage (13), and reduced bird damage (10) (Table 7). This suggests that these key points should be included in messaging to CCAs regarding the recommended, but largely unused (Prasifka, Pers. Obs.), cultural control practice of early planting to manage RSSW. Two respondents stated that they would never recommend early planting. This reticence may stem from a lack of willingness on the part of the grower, as noted by one of our respondents: ‘The best you can do with farmers is to convince them to use all tools available to them. They will not spend extra money… Nor will they try things like cover crops without being paid. You just have to get them to consider all the options and point them the right direction’.

Table 6. Management tools that advisors believed are effective for the red sunflower seed weevil, Smicronyx fulvus

Table 7. Situations that would make the recommendation of early planting (of sunflowers) more likely among respondents

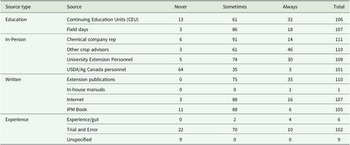

Information sources most used by survey respondents were other crop advisors, extension publications, university extension personnel, Continuing Education Units (CEU), and field days. Trial and error and federal government personnel were the least used (Table 8). Responses suggest that crop advisors rely heavily on their own networks to acquire information. It also indicates that while extension services are still a trusted source of information, their perceived value may be declining, as evidenced by a comment from one of our respondents, who noted, ‘20 years ago academia was very important in agriculture but to day there [sic] a very limited source of information’. This is further supported by Iowa State University studies, which indicated that extension was the first information source for 42% of farmers in 1985 and only 12% in 2005 (Al-Kaisi et al., Reference Al-Kaisi, Elmore, Miller and Kwaw-Mensah2015). This sentiment that academia (which includes land-grant universities and extension programs) may be less relevant than in the past and the near total absence of USDA/Ag Canada personnel as CCA resources is concerning, as new techniques and updates to existing practices are more likely to come from research specialists than from generalists.

Table 8. Information sources used by respondents

This declining relevance could be due to funding and staffing cuts (Serenari et al., Reference Serenari, Peterson, Bardon and Brown2013; Wang, Reference Wang2014). For instance, the number of extension faculty at University of Illinois dropped from 92 to 16 between 1986 and 2013 (Al-Kaisi et al., Reference Al-Kaisi, Elmore, Miller and Kwaw-Mensah2015). Similarly, before 1992, Iowa had an extension educator trained in agriculture in all 99 counties; whereas today there are only 20 regional directors, 12 of whom are trained in agriculture (Al-Kaisi et al., Reference Al-Kaisi, Elmore, Miller and Kwaw-Mensah2015). Overall, the number of FTEs per 1000 farms is highly variable with over 20 in North Dakota and fewer than five in Minnesota and South Dakota (Wang, Reference Wang2014). Additionally, a shift to larger farming and agribusiness operations may have facilitated a move to private information sources (Al-Kaisi et al., Reference Al-Kaisi, Elmore, Miller and Kwaw-Mensah2015).

Overall, CCA communication in this study appeared to have homophilous and heterophilous elements (Rogers, Reference Rogers2003). As to the former, crop advisors in this study appear to be little different from farmers who are heavily influenced by their own peer networks (Lubell, Niles and Hoffman, Reference Lubell, Niles and Hoffman2014; Skaalsveen, Ingram and Urquhart, Reference Skaalsveen, Ingram and Urquhart2020), which should come as no surprise, as most communication is homophilous in nature (Rogers, Reference Rogers2003). As to the latter, university extension is still among advisors’ top information sources in this study and that of Tylka et al. (Reference Tylka, Wintersteen and Meyer2005). Thus, extension services could exploit CCA peer networks in a ‘train the trainer’ approach with the intent of creating a multiplier effect (Lubell et al., Reference Lubell, Niles and Hoffman2014; Warner et al., Reference Warner, Harder, Wichman and Dowdle2014). This approach has already been adopted by Iowa State University (Tylka et al., Reference Tylka, Wintersteen and Meyer2005), Nebraska’s Urban Tree Care Workshops (Skelton and Josiah, Reference Skelton and Josiah2003), and Florida’s Master Gardener Program (Warner et al., Reference Warner, Harder, Wichman and Dowdle2014). Potential limitations of this study include coverage errors and geographic limitations. Our choice of listservs may have biased the results to independent crop consultants at the expense of those working for the industry. Additionally, full-time agronomists employed by large farming operations may have been excluded. Lastly, the results were more biased toward the Great Plains region of North America, which is dominated by row crop agriculture. Results may not be transposable to regions like California that are dominated by smaller fruit and vegetable operations.

Conclusions

Despite its ubiquity, the quality of IPM adoption is mixed; thus, better stakeholder outreach is needed. Crop advisors may be a good conduit for such outreach, as growers often rely on them to make pest management decisions. From our survey, CCAs appear to be well-trained and equipped to conduct scouting and make recommendations. However, CCAs’ formal education in entomology and knowledge of IPM appear to be limited, and advisors still need convincing to recommend new practices such as early planting of sunflowers. Furthermore, work conducted by government agencies may not be reaching end users as intended, as some CCAs prefer not to use them as sources of information. Thus, efforts to implement new practices could focus on educating the extension personnel (or other crop advisors) whom CCAs seem to trust. Additionally, the efforts of the extension services to demonstrate benefits or effects indirectly related to pest management strategies could be increased. With these changes, we may see a greater degree of adoption of sustainable practices among the end users.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge CCA organizations and other industry professionals, including Alison Pokrzywinski (Nuseed USA), for their assistance in obtaining survey results. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: J.C., D.P.-V., P.K., J.P.; Formal analysis: J.C.; Funding acquisition: D.P.-V., J.P.; Methodology: J.C., D.P.-V., P.K., J.P.; Software: J.C.; Writing—original draft: J.C., J.P.; Writing—reviewing and editing: J.C., D.P.-V, P.K., J.P.

Funding statement

This project was funded by U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service through project 3060-21000-047-000-D.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Ethics statement

The North Dakota State University Institutional Review Board determined this survey to be exempt on 8 January 2024 (IRB0005012).