Management scholars have long touted the impact of developing and nurturing cooperative relations with stakeholders (Bacq & Aguilera, Reference Bacq and Aguilera2022; Barnett, Reference Barnett2007; Bridoux & Stoelhorst, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2022; Dorobantu, Henisz, & Nartey, Reference Dorobantu, Henisz and Nartey2017; Freeman & Evan, Reference Freeman and Evan1990; Jones & Wicks, Reference Jones and Wicks1999; Kaul & Luo, Reference Kaul and Luo2018; Markman, Waldron, Gianiodis, & Espina, Reference Markman, Waldron, Gianiodis and Espina2019). From a strategic standpoint, allowing stakeholders to benefit and even capture rents enables companies to develop bundles of unique resources that competitors can hardly imitate (Barney, Reference Barney2018; Mahoney, Reference Mahoney, Costa and Marti2012; McGahan, Reference McGahan2021). This argument echoes the instrumental view of stakeholder management (Donaldson & Preston, Reference Donaldson and Preston1995; Jones, Harrison, & Felps, Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018): close cooperative relations emerge because they generate superior organizational outcomes, which can be expressed as superior profitability and even firm-specific rents that might not be easily replicated and competed away.

While acknowledging the relevance of such instrumental arguments, this study draws from previous work emphasizing the role of normative (morally informed) principles influencing how stakeholders effectively engage in performance-enhancing organizational effort. In other words, this article departs from the perspective that the instrumental and normative views are deeply intertwined and can jointly explain the adoption of stakeholder-oriented strategies (Freeman, Reference Freeman1994; Jones & Wicks, Reference Jones and Wicks1999). For instance, Freeman, Dmytriyev, and Phillips (Reference Freeman, Dmytriyev and Phillips2021: 1761) point out that developing rent-creating stakeholder relations requires assumptions about how agents develop implicit contracts based on “social and moral norms,” whereas Weitzner and Deutsch (Reference Weitzner and Deutsch2019: 695) submit that a normative emphasis supports the pursuit of broad stakeholder gains, which can be limited if companies try to avoid the imitation or replication of the proposed strategies. Some also argue that clear normative guidelines can support a more authentic and committed social orientation, especially in cases where stakeholder-oriented strategies do not yield immediate gain and might even require financial sacrifice (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2020; Rangan, Reference Rangan and Rangan2018).

Yet, even though the literature has recognized the potential complementarity of instrumental and normative arguments, there is relatively less work on how those arguments can jointly explain organizational efforts to engage critical stakeholders. This article examines this question by studying the case of open stakeholder strategies, whereby companies engage and even sponsor stakeholders who are free to transact with multiple actors, including competitors who might imitate those strategies. Focusing on how firms engage suppliers as critical stakeholders (Eskandarpour, Dejax, Miemczyk, & Péton, Reference Eskandarpour, Dejax, Miemczyk and Péton2015; Markman & Krause, Reference Markman and Krause2016; Soundararajan, Brown, & Wicks, Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019), this article conducts an in-depth examination of Natura, a multinational cosmetics company that originated from Brazil. Natura has developed an open web of relations with suppliers to procure natural (“biodiversity”) inputs from the Amazon region, which are used in its products. The company has provided suppliers with training, organizational support, and infrastructure investments promoting sustainable practices. However, there is no exclusivity agreement requiring them to transact only with Natura. Suppliers are free to engage with other firms and even competitors that have flocked to the region to procure similar inputs.

Although previous work has assessed Natura’s stakeholder-oriented strategy (Boehe, Pongeluppe, & Lazzarini, Reference Boehe, Pongeluppe, Lazzarini, Liberman, Garcilazo and Stal2014; Gatignon & Capron, Reference Gatignon and Capron2023; Lopez‐Vega & Lakemond, Reference Lopez‐Vega and Lakemond2022; McGahan & Pongeluppe, Reference McGahan and Pongeluppe2023), the specific objective of this research is to use the case of Natura and its open relational strategy as an opportunity to understand how firms pursue long-term instrumental outcomes supported by a solid normative (morally informed) orientation. In other words, this study explains how instrumental and normative arguments can jointly explain open stakeholder strategies. The combined instrumental and normative logic draws from Freeman’s (Reference Freeman1994: 413) concept of normative core: “the way that corporations should be governed and the way that managers should act.” In the case of Natura, the normative core—expressed as a set of philosophical beliefs and values advanced by its founders and percolating the whole organization—emphasizes that the company should pursue broad and balanced stakeholder gains beyond economic returns (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013) and that managers should consider a wide set of stakeholders beyond its set of close, recurring partners. In other words, the normative core has fostered a more interconnected, systemic view of stakeholder relations (Crane, Reference Crane2020).

Analyzing the case of Natura, this article proposes that the normative core was critical at moments when the future outcomes of the relational strategy were highly uncertain for the involved stakeholders (Packard, Clark, & Klein, Reference Packard, Clark and Klein2017), thereby supporting not only the creation of the open strategy but also its subsequent expansion. Over time, as the relational strategy crystallized, Natura could reap long-term instrumental gains via deepened relational attachments with suppliers—who continued interacting with Natura even if approached by other buyers—as well as a substantive (as opposed to symbolic) stakeholder orientation differently from competitors (e.g., Marquis & Qian, Reference Marquis and Qian2014; Nardi, Reference Nardi2022; Perez-Batres, Doh, Miller, & Pisani, Reference Perez-Batres, Doh, Miller and Pisani2012). Such instrumental outcomes, in turn, helped validate and reinforce the importance of the normative core as a key feature of the open strategy, thereby allowing for the expansion of the strategy in other locations.

The study’s emphasis on the mutual interplay of instrumental and normative arguments contributes to a broad debate on the foundations of stakeholder engagement (Bacq & Aguilera, Reference Bacq and Aguilera2022; Dorobantu & Odziemkowska, Reference Dorobantu and Odziemkowska2017; Garcia‐Castro & Aguilera, Reference Garcia‐Castro and Aguilera2015; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018; Kaul & Luo, Reference Kaul and Luo2018; Mahoney, Reference Mahoney, Costa and Marti2012; McGahan, Reference McGahan2021). In his resource-based theory of stakeholder relations, Barney (Reference Barney2018: 3321) argues that it “takes less of a normative perspective, and much more of a positive perspective” and is not based on “a moral standard against which to judge a firm’s actions.” However, emphasizing a complementary view of instrumental and normative arguments (Freeman, Reference Freeman1994; Jones & Wicks, Reference Jones and Wicks1999), this study proposes that instrumental outcomes require a normative commitment to stakeholders—especially in the case of strategies that might be rife with financial trade-offs and with uncertain outcomes in their initial stages. The presence of a strong normative core, this study argues, is crucial when pursuing stakeholder relations is not perceived to confer clear instrumental benefits; and the subsequent emergence of clear instrumental outcomes helps reinforce the importance of the normative core. The research’s focus on supplier relations also deepens the understanding of suppliers as critical stakeholders and the broad benefits that their engagement can generate (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013). It also connects with recent work discussing how supplier engagement can increase supply chains’ resilience and societal impact (e.g., Gualandris et al., Reference Gualandris, Branzei, Wilhelm, Lazzarini, Linnenluecke, Hamann, Dooley, Barnett and Chen2024; Markman & Krause, Reference Markman and Krause2016).

The analysis of Natura also indicates that shareholders can have a critical role in fostering the normative core. Although stakeholder-based arguments have challenged the notion that organizations should unequivocally follow the interests of shareholders (e.g., Stout, Reference Stout2012), this work shows that shareholders’ influence may be positive and even crucial when they have preferences aligned with the general objective of promoting open relations and broad socio-environmental gains—which, in the case of Natura, is also reinforced by its multiple stakeholder goals and organizational choices (e.g., the company is a B Corp). In particular, this research demonstrates the importance of understanding who holds critical corporate control rights and how those actors might have preferences aligned with the general objective of promoting open stakeholder relations generating broad systemic societal gains.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Strategic Stakeholder Relations as a Nexus of Externalities

After decades of research on how firm-level strategies explain heterogeneous economic performance, scholars have been increasingly interested in how these strategies affect multiple stakeholders—expressed as positive or negative externalities that their operations generate to the environment, to the well-being of exchange partners and society in general (Battilana & Lee, Reference Battilana and Lee2014; Durand, Hawn, & Ioannou, Reference Durand, Hawn and Ioannou2019; Luo & Kaul, Reference Luo and Kaul2019; Mahoney, McGahan, & Pitelis, Reference Mahoney, McGahan and Pitelis2009; Quelin, Kivleniece, & Lazzarini, Reference Quelin, Kivleniece and Lazzarini2017). Dealing with environmental issues, for instance, usually involves curbing negative externalities such as pollution or carbon emissions (Bansal & DesJardine, Reference Bansal and DesJardine2014; Berry, Kaul, & Lee, Reference Berry, Kaul and Lee2021). Positive externalities, in turn, can occur when private investments promote broad stakeholder gains and local development, often transcending the activities of the focal firms (Lazzarini, Reference Lazzarini2020; Mahoney & Qian, Reference Mahoney and Qian2013; Santos, Reference Santos2012).

Although governmental regulation and even public ownership are often invoked as potential remedies to deal with externalities (Tirole, Reference Tirole2017), scholars such as Coase (Reference Coase1960) and Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) forcefully argued that their presence is not a necessary condition for public involvement. It all depends on the ability of private actors to manage formal or informal arrangements that allow for an appropriation of the gains or losses their activities can generate to multiple stakeholders. In other words, managing multiple externalities can be a core element of a firm’s strategy (Cabral, Mahoney, McGahan, & Potoski, Reference Cabral, Mahoney, McGahan and Potoski2019; Kaul & Luo, Reference Kaul and Luo2018; Porter & Kramer, Reference Porter and Kramer2011; Vasudeva & Teegen, Reference Vasudeva, Teegen, Marcus, Shrivastava, Sharma and Pogutz2011)—which corresponds to the strategic management of a web of relationships with potential external impact on diverse stakeholders.

A critical question, therefore, is to examine ways in which firms can internalize positive outcomes that accrue to myriad actors. The following section discusses potential instrumental outcomes emanating from stakeholder relations, with a particular emphasis on suppliers as critical stakeholders (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013) and the mechanisms through which supplier relations can generate broad societal benefits (Gualandris et al., Reference Gualandris, Branzei, Wilhelm, Lazzarini, Linnenluecke, Hamann, Dooley, Barnett and Chen2024; Markman & Krause, Reference Markman and Krause2016). The research focuses on the interplay between the instrumental and normative views of stakeholder theory, even though the subsequent analysis of empirical data is also consistent with what Donaldson and Preston (Reference Donaldson and Preston1995: 66) refer to as descriptive stakeholder analysis, that is, “a model describing what the corporation is.”

Instrumental Stakeholder Relations

The instrumental view proposes that “corporations practicing stakeholder management will, other things being equal, be relatively successful in conventional performance terms (profitability, stability, growth, etc.)” (Donaldson & Preston, Reference Donaldson and Preston1995: 67). In this view, nurturing engaged and cooperative relations with stakeholders allows companies to implement and sustain strategies that yield positive outcomes, especially expressed as economic gains (Khan, Serafeim, & Yoon, Reference Khan, Serafeim and Yoon2016; Seo, Luo, & Kaul, Reference Seo, Luo and Kaul2021; Zhang, Wang, & Zhou, Reference Zhang, Wang and Zhou2020). Such economic gains come from distinct channels but fundamentally involve long-lasting rents by creating and tapping into unique stakeholder resources (Garcia‐Castro & Aguilera, Reference Garcia‐Castro and Aguilera2015; McGahan, Reference McGahan2021; Odziemkowska & Dorobantu, Reference Odziemkowska and Dorobantu2021). Thus, Barney (Reference Barney2018) argues that companies can create a competitive advantage and sustain economic rents by promoting cospecialized resource development with key stakeholders. In turn, stakeholders will be incentivized to invest in such cospecialized resources if they can reap part of their associated rents. Given the cospecialized nature of these investments, they should also protect the firm from imitation or replication.

Indeed, this type of cospecialized stakeholder engagement has long been discussed in the relational strategy literature. Scholars examining supplier relations have emphasized that cospecialized, relationship-specific investments enhance long-term cooperation benefits and create unique rents accruing to the exchange partners (Dyer & Singh, Reference Dyer and Singh1998; Mesquita, Anand, & Brush, 2008). Similarly, Jones, Harrison, and Felps (Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018) argue that close relationships with key stakeholders can limit opportunistic behavior, enhance cooperation, and generate instrumental outcomes for firms engaged in stakeholder-oriented strategies. In their words, close stakeholder relations involve “general, implicit, and open-ended commitments to cooperate voluntarily and generously with partners in joint wealth creation efforts” (2018: 375). Unique stakeholder relations, in turn, lead to gains that competitors cannot easily replicate without the ability to develop such relational strategies (Barney & Hanson, Reference Barney and Hanson1995). Therefore, with close, cospecialized relations, the focal firm not only generates and internalizes the externalities that emanate from partners and their unique resources but also creates barriers to replication and imitation.

Relational cooperation, however, may also emerge in situations where actors remain permeable to new opportunities outside their close, recurring exchanges (Burt, Opper, & Holm, Reference Burt, Opper and Holm2022). Open relations involve a broad set of stakeholders that may be relatively free to interact with alternative partners and whose externalities may reach well beyond the domain of the focal firm managing these relations. Building on Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) conceptualization of polycentric governance, Gatignon and Capron (Reference Gatignon and Capron2023) discuss how companies can forge open institutional infrastructures whereby parties self-enforce action standards and broadly share their exchange gains. Open relations are also consistent with Crane’s (Reference Crane2020: 265) view of interconnected stakeholders “within a system,” in which “the actions of a firm toward one stakeholder can influence the perceptions of trustworthiness of other stakeholders.”

Therefore, open relational strategies might promote instrumental outcomes for the transacting parties and generate externalities to other actors in similar exchange contexts. This creates potential financial trade-offs for the companies implementing such open relations. They will have to deploy or develop costly resources that are broadly shared and may not necessarily lead to higher appropriated rents. If the future value of those exchanges is uncertain (Elfenbein & Zenger, Reference Elfenbein and Zenger2013), it will be difficult to estimate and even identify future instrumental outcomes. In addition, open relational strategies may become prone to imitation and replication. For instance, a focal company may be less incentivized to invest in supplier training if partners may eventually work with competitors and share part of their knowledge (Dyer & Hatch, Reference Dyer and Hatch2006). In other words, investing in open relations might not lead to sustained competitive advantage if the focal firm may not sufficiently capture the gains those investments generate (Teodorovicz, Lazzarini, Cabral, & McGahan, Reference Teodorovicz, Lazzarini, Cabral and McGahan2024).

A possibility to circumvent this dilemma of open relations is to consider that, over time, parties may progressively develop recurring exchanges due to evolving routines and transaction-specific learning. In other words, open relations may become increasingly close and even restricted to a few buyer-supplier exchange circles (Uzzi, Reference Uzzi1997). This mechanism echoes Williamson’s (Reference Williamson1985) argument that exchanges tend to develop cospecialized assets and processes in the long run, thereby restricting the exchange to a few players. In other words, developing open relations can also be consistent with an instrumental emphasis on capturing rents from ongoing exchanges as long as those exchanges progressively become more or less exclusive ties.

Normative Stakeholder Relations

Beyond the instrumental outcomes that close relations can generate, companies might also generate externalities to a broader set of stakeholders based on principles of stakeholder engagement. The normative strand of stakeholder management theory tries to identify the moral underpinnings of stakeholder-oriented strategies (Donaldson & Preston, Reference Donaldson and Preston1995; Evan & Freeman, Reference Evan, Freeman, Beuchamp and Bowie1993). In this view, nurturing positive stakeholder relations may emerge even when financial trade-offs are involved or when the appropriation of economic gains is uncertain (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2020; Rangan, Reference Rangan and Rangan2018; Singer, Reference Singer2018). A normative emphasis on partner development and inclusion may support open relations. For instance, the “fair trade” movement has argued for a more equitable distribution of economic gains and exchange opportunities, especially when vulnerable suppliers are involved (Renard, Reference Renard2003). Some have also proposed that sustainable supply arrangements require prioritizing the environment and society above economic returns (Markman & Krause, Reference Markman and Krause2016).

Freeman (Reference Freeman1994), in particular, argued that stakeholder-centered theories have a normative core specifying guidelines for corporate and managerial action. In his view, the normative core defines how firms should be governed and how managers are supposed to act. As such, the core is expected to vary across firms based on their “business and moral terms” (Freeman, Reference Freeman1994: 414). Notably, instead of treating instrumental and normative arguments as separated, Jones and Wicks (Reference Jones and Wicks1999) argued that distinct normative cores could also support instrumental relational strategies; for instance, firms capitalizing on their unique relational strategy to generate positive firm-level outcomes can follow the normative orientation that “relationships characterized by mutual trust and cooperation are morally desirable” (Jones & Wicks, Reference Jones and Wicks1999: 218). This could support a normative core where firms are expected to develop relationships based on mutual trust, and managers are supposed to nurture such trust-based cooperative relations. In other words, as Freeman et al. (Reference Freeman, Dmytriyev and Phillips2021: 1761) emphasize, social and moral norms bolster implicit contracts with stakeholders, thus suggesting that instrumental theories on how firms exchange with and access valuable stakeholder resources (such as Barney, Reference Barney2018) “must adopt normative theorizing” (emphasis in the original).

Even though previous work in stakeholder theory has underscored the role of reciprocity norms and trust in ongoing exchanges (Bosse, Phillips, & Harrison, Reference Bosse, Phillips and Harrison2009; Bridoux & Stoelhorst, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2022; Bundy, Vogel, & Zachary, Reference Bundy, Vogel and Zachary2018; Jones, Reference Jones1995), normative considerations become particularly relevant in the context of open relations with a broad set of partners, which might benefit from the externalities that the focal firm generates without any expectation of reciprocal action. Even if open strategies became progressively close over time, developing open relations requires organizational commitment because their instrumental outcomes will take time to be realized, and they generate a host of external gains, including to actual or potential competitors. Furthermore, different from the relational norms that might support close relations, some firms may want to generate broad benefits beyond their set of close, recurring partners and might even stimulate other firms to pursue similar actions (Weitzner & Deutsch, Reference Weitzner and Deutsch2019). Therefore, a normative core emphasizing the pursuit of broad stakeholder gains (beyond the set of recurring actors supported by reciprocity norms) can be a way in which firms develop and nurture open stakeholder relations.

Where does the normative core come from? Scholars have increasingly relaxed the assumption that firms care solely about the generation of economic rents and consider how distinct business objectives may affect the development of stakeholder-oriented strategies (Barnett, Reference Barnett2007; Battilana, Obloj, Pache, & Sengul, Reference Battilana, Obloj, Pache and Sengul2022; Nicholls, Reference Nicholls2009). Those objectives can be gradually developed by managers and relevant stakeholders but ultimately depend on the preferences of those who hold critical decision rights (Foss & Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2018; Hansmann, Reference Hansmann1996). In for-profit corporations, shareholders have decision rights and might delegate those rights to professional representatives, such as independent board members (Fama & Jensen, Reference Fama and Jensen1983). Although stakeholder-based arguments challenged the emphasis on strategies conceived with the sole purpose of increasing shareholder wealth (Stout, Reference Stout2012), recent work has considered the possibility that shareholders themselves might have pro-social preferences and value actions that generate societal externalities (Hart & Zingales, Reference Hart and Zingales2017; Mackey, Mackey, & Barney, Reference Mackey, Mackey and Barney2007). Similarly, Morgan and Tumlinson (Reference Morgan and Tumlinson2019) examined theoretical channels through which shareholders incentivize the provision of public goods. However, scant work has been done on how those actors define moral guidelines and stimulate internal or external organizational members to pursue broad externalities.

In the subsequent empirical analysis, this research uses fine-grained information from the longitudinal, in-depth case study of Natura to examine potential mechanisms through which companies might commit to open relational strategies based on the interplay of instrumental and normative arguments outlined above.

METHOD AND DATA COLLECTION

Methods

The research team employs an in-depth case study methodology and intentionally chooses an extreme case—warranted when research seeks to challenge existing world views and inductively unearth new ideas or theoretical relationships (Siggelkow, Reference Siggelkow2007). In line with the primary goal of this paper, which is to theorize on how normative guidelines support instrumental outcomes, the research team primarily uses an extreme case to “build and compare explanations” (Yin, Reference Yin1981: 61). Accordingly, using the focal case, the study starts by describing how open relational strategies work and then goes on to assess potential mechanisms underpinning the company’s open relational model since its inception. In fact, single cases are particularly useful for analyzing phenomena spanning an extended period (Langley, Reference Langley1999; Pratt, Reference Pratt2000); in this case, interviews extend over eleven years, with relevant facts spanning 20–40 years.Footnote 1 Eisenhardt, Graebner, and Sonenshein (Reference Eisenhardt, Graebner and Sonenshein2016: 1118) argued that extreme cases are appropriate to address challenging themes because “they can also facilitate the novel insights that grand challenges require” and because “extremeness makes their insights more transparent.” Therefore, due to the possibility of studying the phenomenon of open relations in a longitudinal setting and the explanatory purpose of this study, the extreme case analysis is employed in two complementary ways: description and explanation.

The chosen case, Natura, fits these criteria well. The company has a strong and historical emphasis on sustainable strategies. Natura Co., the largest Latin American cosmetics manufacturer with net revenue of over US$5.36 billion in 2023, has repeatedly been awarded distinctions and been ranked as one of the ten most innovative companies in the world by Forbes in 2013, “the World’s largest B Corp”—that is, a company that combines profitability and socio-environmental objectives (Marquis, Reference Marquis2020)—the United Nations’ “Champion of the Earth” in 2015 “for unparalleled commitment to trailblazing sustainable business models,” and part of the top fifteen most sustainable corporations in the world by Corporate Knights in 2019.Footnote 2

Importantly, previous evidence indicates that Natura has managed a complex array of stakeholders. The company has established nonexclusive vertical relations with suppliers in the Amazon region who are themselves horizontally connected via supplier cooperatives and associations—thus characterizing what Lazzarini, Chaddad, and Cook (Reference Lazzarini, Chaddad and Cook2001) referred to as a netchain (a complex mix of vertical and horizontal ties in procurement relations). In this context, Natura promoted several investments in training and infrastructure that can, in principle, benefit other players and even competitors. Initially established in the city of Benevides, State of Pará, the company progressively pursued new supplier communities in the rainforest area. By 2019, Natura’s supplier relations covered around sixty-nine counties, fifty-six of which are in the Brazilian Amazon region (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Geographical Distribution of Natura’s Suppliers

These suppliers are usually indigenous Amazonian communities living on the shores of Amazonian rivers and organized in cooperatives or producer associations. During the study period, Natura had ongoing contracts with thirty-eight different cooperatives and associations, thirty-three of which were based in the Amazon region, and nineteen of them had processing plants in their location. On average, each association had 140 member families, with an average of four individuals per family unit. Among the inputs produced, Natura sourced fourteen different Amazonian fruits, berries, nuts, and seeds. Some of these inputs come from large-sized Amazonian trees which contribute to forest preservation (e.g., ucuuba, castanha or Brazil nut, andiroba). In contrast, others come from medium-sized trees (e.g., cocoa and cupuaçu) as well as palm trees (e.g., açaí, murumuru, and babaçu), all of which contribute to forest regeneration. Many of these Amazonian products do not have regular established markets; as the study explains in the next section, Natura, the local communities, nonprofit organizations, and civil society organizations jointly act to cocreate and structure the entire supply-chain for these products.

Data Collection

The empirical investigation unfolded over three phases in eleven years (Table 1) and used three main data collection strategies: open-ended interviews, overt participant observation, and archival data. The research team used several triangulation strategies to mitigate potential biases (e.g., holistic fallacy) and to validate the conclusions emerging from the analyses. The authors collected primary and secondary data at different moments in time, at various hierarchical levels, on a wide range of stakeholders (Pratt, Reference Pratt2000). Distinct primary data collection methods were also used, as described later. Researcher triangulation occurred naturally as three authors visited the research sites independently and at different times over the eleven years. The authors shared, compared, and extensively discussed their observations, interpretations, and notes until divergent interpretations were clarified.

Table 1: Phases of Data Collection and Analysis

In addition, the research team compared and contrasted information to uncover conflicting meanings and alternative explanations for Natura’s open relational model; for instance, the team sought to understand why some supplier cooperatives sold their harvest to competitors while others did not, despite identical coordination mechanisms. The authors shared transcripts and case study write-ups with informants and incorporated their feedback at several stages over the whole period of the project. Finally, the researchers designated one team member to question the results and review the case independently. This approach helped scrutinize the extent to which the findings hold in different contexts (Pratt, Kaplan, & Whittington, Reference Pratt, Kaplan and Whittington2019). Altogether, the study counts on information from sixty individuals, ranging from suppliers and supply chain managers to C-level executives and shareholders.Footnote 3

Phases

The initial phase of inductive inquiry, 2011–2013, unearthed the above-mentioned open feature of Natura’s relational strategy and culminated in a preliminary write-up to register the initial data. Guided by theoretical frameworks such as the bottom-of-the-pyramid, resource-based view, and the netchain literature, the authors inferred explanations for this open relational strategy from interview data. In the second phase, 2014–2017, the research team sought to expand the findings, explore possible alternative interpretations that were not given initially, and validate the findings from the first phase and up to a saturation point (Kaplan & Orlikowski, Reference Kaplan and Orlikowski2013). The final phase, 2018–2021, adopted a predominantly abductive posture, expanded data collection, and sought to understand how and why Natura has committed to its open relations and search for the best-educated explanation for the emergence of these open relationships. This longitudinal design also resulted from three idiosyncrasies of the study’s object: (i) the time it takes to develop supplier communities essentially “from scratch” in regions without supporting infrastructure and of difficult access; (ii) the seasonality of biodiversity supplies and the three-year terms of Natura’s supply agreements; and (iii) the lengthy period required to reliably verify to what extent supply chains are in fact open. Drawing from the relevant literature and cues that emerged during interviews, the researchers sought to explain Natura’s open relations and, even more importantly, its determinants. Thus, the scope of questions evolved from an emphasis on the mechanisms of how the open relational model operates to why Natura has committed to this model for a long time.

Open-ended Interviews

The authors conducted open-ended interviews (in Portuguese) with informants from Natura and representatives of its supply chain. These included Natura’s suppliers in the Amazon region, representatives of supplier cooperatives, local and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Natura’s supply-chain managers both in the Amazon region (Pará State) and at Natura’s headquarters (São Paulo State), Natura’s competitors, C-level executives, Natura’s board members, and its cofounders/controlling shareholders. The study’s initial interview guide included questions derived from a literature review on businesses targeting low-income segments (e.g., London & Hart, Reference London and Hart2004; Prahalad, Reference Prahalad2004), cooperative buyer-supplier relationships, and stakeholder involvement, among other aspects. As the investigation shifted from how the model operates to why Natura implemented it, some questions were either dropped or added over time.

Overt Participant Observation

The research team conducted overt participant observations (Pratt & Kim, Reference Pratt and Kim2012) in two moments, first in phase I and second in phase II. In the first case, the authors conducted an “observer-as-participant” overt observation (Pratt & Kim, Reference Pratt and Kim2012) aiming at an in-depth understanding of the perspective of key informants (the supplier communities) at the supply negotiation roundtables. Natura managers collectively organize these roundtables with Amazon supplier communities, cooperatives, and other relevant stakeholders such as local and international NGOs—on this particular occasion, representatives from the OCB (Brazilian Cooperatives Organization) and the GIZ (German Corporation for International Cooperation) were present. These roundtables occurred yearly, following the production cycle of Amazonian natural inputs. One research team member participated as an observer in a three-day negotiation roundtable at Altamira (Pará State) from January 30 to February 1, 2013. Audio recordings, photos, and notes were taken during the entire event. The observations allowed us to understand how the negotiation process happened in reality and thus enabled a more authentic explanation of Natura’s strategy.

In the second phase, the research team conducted a “participant-as-observer” overt observation (Pratt & Kim, Reference Pratt and Kim2012) with twenty Natura’s supply-chain managers at Natura’s headquarters on April 3, 2014. On this occasion, two researchers performed a dynamic exercise with supply-chain managers assigning different “roles for them to play” in the supply chain. The researchers assigned subgroups of managers to the following roles: an Amazon supplier community, a local NGO, a government agency, Natura supply-chain managers, and Natura’s clients. Through this exercise, the research team elicited meaning and sensemaking (Pratt, Reference Pratt2009) regarding Natura’s open approach. For example, during the exercise, some managers described the benefits of sharing part of the value with the supplier communities to generate value for final consumers of Natura’s cosmetics products. As in the previous phase, this process also contributed to gaining trust and facilitated open-ended follow-up interviews.

Archival Data

The authors analyzed two main sets of archival information, one private to Natura and another from publicly available sources. The Natura archives consist of internal presentations, video recordings, qualitative and quantitative data documents, supply agreements from different years, and photos. These materials helped to understand the backbone of the relational model. For example, the supply agreements between Natura and suppliers described prices, volumes, quality standards, and duration; however, they did not include any exclusivity clauses, indicating the open character of Natura’s relations. The research team further triangulated other primary and secondary information sources with publicly available archives, such as government legislations, government authorizations to bioprospection, Natura’s annual and sustainability reports, as well as newspaper or business magazine articles from several countries (e.g., Brazil, France, Germany, and the USA).

Analysis

Because the traditional instrumental explanations were not sufficient to explain Natura’s open strategy, in phase III, the study followed recommendations made by Miles and Huberman (Reference Miles and Huberman1994) and derived relevant analytical categories from previously discussed conceptual frameworks, to which the research team added new codes that emerged from interviews conducted in phases I and II. These analytical categories informed the study’s interview guide, which thus included questions on externalities, relational strategies, stakeholders, and the intertwined instrumental and normative arguments.

Two members of the research team independently coded all interview transcripts using NVivo to analyze the collected information. The authors discussed the consistency of the coding at different stages of the analysis. The team revised the coding and interview guides before and after the interviews. The researchers created memos with thoughts, associations, and preliminary propositions that emerged during the coding process. After the initial coding, the team sought to identify relationships among codes and aggregated them into higher-level concepts and categories (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009). To the initial list of codes, the authors added in vivo codes for repeatedly used expressions or phrases mentioned by the interviewees and added new codes for relevant events or practices not contemplated in the study’s original framework. This approach thus allowed the research team to account for unanticipated, emerging theoretical mechanisms leading to an evolving interpretation of how the open model operates and why it exists.

To assess alternative explanations for Natura’s adoption of the open relational model, the authors employed the alternate templates strategy (Bitektine, Reference Bitektine2008; Langley, Reference Langley1999), a falsification technique that goes back to Allison’s seminal work on the Cuban missile crisis (Allison & Zelikow, Reference Allison and Zelikow1971). Two alternative interpretations emerged from the data and crystallized into coherent theoretical mechanisms as the team contrasted data with the extant literature. Below, the study describes the main findings in detail, briefly explaining the key features of Natura’s open relational model. Next, the document examines potential instrumental explanations of how the model evolved. Finally, the study describes how Natura’s normative core was crucial for creating and implementing the open relational strategy model and its emergent instrumental outcomes.

NATURA’S OPEN RELATIONAL MODEL: STRUCTURE

Before explaining the instrumental and normative arguments supporting Natura’s relational model, the study briefly reports baseline findings describing the main structure of open stakeholder relations. The research draws from interview data as well as previous work on Natura’s strategy (Boehe et al., Reference Boehe, Pongeluppe, Lazzarini, Liberman, Garcilazo and Stal2014; Gatignon & Capron, Reference Gatignon and Capron2023; Lopez‐Vega & Lakemond, Reference Lopez‐Vega and Lakemond2022; Nasalay, Pongeluppe, & Light, Reference Nasalay, Pongeluppe and Light2015). The open relational strategy employed by Natura is part of what Gatignon and Capron (Reference Gatignon and Capron2023) refer to as an open institutional structure, even though the analysis is more specialized at the level of supply networks and procurement (buyer-supplier) relations and, as discussed before, seeks to investigate the complementarity of instrumental and normative arguments explaining the open relational strategy. The open procurement strategy’s key explanatory attributes come from the interviewers’ coding. The study unearthed four distinctive design features of Natura’s open relational strategy, which are described below.

Balanced Performance Objectives

The first essential characteristic of Natura’s open relational strategy is that it is consistent with a broader mission to generate socio-environmental gains beyond profits. Reflecting this orientation, the company is certified as a B Corp (Marquis, Reference Marquis2020) and has pursued a multiplex, “quadruple bottom line” approach emphasizing environmental, social, human, and economic performance dimensions in its interactions with the suppliers of biodiversity products. In addition, as illustrated in Figure 1, the impact of Natura’s strategy was not only circumscribed to a few developed communities but also involved a progressive increase of its reach in multiple areas.

Nonexclusive Engagement with Suppliers

The company proactively searches for suppliers in the Amazon rainforest region to foster this expansion. It supports suppliers with training modules, organizational support, investments in input processing plants, and storage facilities. Natura also provides suppliers with technical guidance on extracting biodiversity products sustainably via forest management practices. The company educates suppliers on the risks of an excessive exploration of biodiversity inputs. It demonstrates the extra income they can generate using the forest as a long-term resource. These actions are often supported by local, horizontal ties between suppliers (via cooperatives and associations) in a vertical supply chain. Investments are generally implemented as unconditional donations—for example, a supplier cooperative can receive support to build a processing plant without obligation to reimburse Natura. Importantly, even though a formal contract specifies some target quantities to be purchased by Natura, the contract does not include exclusivity clauses, and there is no explicit penalty if suppliers fail to sell the specified output. Moreover, the contracts formally establish the commitment to the ethical use of biodiversity inputs in tandem with transparent and fair relationships with the supplier communities.Footnote 4 The supply infrastructure built and maintained by Natura is open for competitors and buyers from other industries to purchase the same biodiversity inputs. As explained in more detail below, Natura even incentivizes the entry of potential competitors or communities selling to competitors.

Legitimacy Building

Historically, the Amazon region has been a source of conflict and extractive practices. Preserving the forest was traditionally seen as a hurdle to economic progress, and a range of natural resources from the Amazon have been exploited and depleted, often via illegal business activity (Alston, Libecap, & Mueller, Reference Alston, Libecap and Mueller2000). Therefore, to increase the legitimacy of its operations and foster relational supply strategies, Natura nurtured plural partnerships with social movement organizations which are active stakeholders in the region (King & Pearce, Reference King and Pearce2010; Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009), some of which, paradoxically, expressed conflicting views on whether for-profit business activities should be developed in the Amazon. Thus, Natura partnered with FASE,Footnote 5 a Marxist-oriented NGO, to contact potential communities in the region. It even hired former FASE employees to work on its supply operations. Similarly, Natura partnered with Chico Mendes Memorial,Footnote 6 an NGO founded in honor of the homonymous environmentalist and rubber tapper murdered by large-scale ranchers’ sicarios. Natura also develops horizontal relations with industry peers, via activities that seek to set common and collective industry standards. These standards are primarily self-regulated via standard-setting groups (such as the Union for Ethical BioTrade [UEBT]Footnote 7) and pursued even beyond what is dictated by local government laws. Although the commercial access to biodiversity products was regulated by an executive order issued in 2001, the final legislation was only approved in 2015. Natura has acted proactively, advocating the importance of improved sustainability practices and promoting their implementation in the Amazon region.

Market-spanning Rent Creation and Sharing

Natura uses rents generated in final customer markets to support cooperative strategies in downstream supply markets. Recurring interactions with supplier associations and cooperatives promote supply market cocreation for previously unknown inputs for which no organized market exists. These efforts, in turn, support the development of differentiated cosmetic products for which final customers are willing to pay a price premium. Consequently, rents stemming from differentiated products in high-end customer markets help compensate for Natura’s investments in the supplier communities and are partially shared with its Amazonian suppliers. Even though this rent-sharing mechanism became a legal requirement with the promulgation of biodiversity legislation in 2015, as mentioned before, Natura had already fully implemented the model since the early 2000s, and some have even argued that Natura’s benefit-sharing program inspired the new legislation.

The next step is to explain how their strategy derives from the interplay of instrumental and normative arguments emerging from the case analysis.

INSTRUMENTAL ARGUMENTS FOR NATURA’S OPEN RELATIONAL MODEL: KEY FINDINGS

In this section, the study describes key findings suggesting instrumental explanations for Natura’s open relational strategy. The coding and data analysis revealed fundamental instrumental mechanisms, partly derived from the desire to create a unique value proposition based on differentiated products with an environmentally friendly image. Although Natura initially focused on the Brazilian domestic market, its strategy seems to have anticipated fair trade and sustainability principles, which became progressively relevant in discussions on the role and impact of multinational corporations (London & Hart, Reference London and Hart2004). Accordingly, in the late 2010s, the company engaged in a more aggressive global expansion by acquiring Aesop, The Body Shop, and Avon. Therefore, if one applies standard value creation and appropriation logic (Brandenburger & Stuart, Reference Brandenburger and Stuart1996), instrumental outcomes emanating from Natura’s strategy can be described as tapping customers with a greater willingness to pay for sustainability-linked products, using its distinct operations in the Amazon rainforest as an attribute of differentiation. As put by a controlling shareholder:

We dreamed of the long term and noticed that what differentiates us was having an Amazon brand, having legitimacy, having a rootedness, being transparent; this was our passport to internationalize. I remember that even then, we used to say: “our best public relations person will be a journalist from the Financial Times, from the New York Times, to visit the communities regardless of our monitoring and follow-up, and they say what they think” (anonymized, cofounder and shareholder, personal communication).

In other words, by being a first mover in its effort to develop its unique sourcing operations and differentiated products, Natura could leverage its operations not only in the domestic but also in the global market. Natura’s willingness to invest in supplier communities and share rents with suppliers (discussed in the previous section) is also consistent with the argument that unique stakeholder engagement increases when stakeholders can appropriate part of the residual economic value generated in the transaction (e.g., Barney, Reference Barney2018). Yet the open nature of Natura’s strategy implies that stakeholders are, a priori, free to interact with several other partners, including competitors. Over time, entrants could possibly replicate Natura’s differentiated products or compete for similar supplier inputs, reducing the firm’s ability to sustain distinct economic rents.

However, the nature of an ongoing exchange is expected to evolve and change over time. Even though Natura’s relations are, in principle, open, they are subject to social complexity and path-dependent processes, all of which create imperfect or costly imitability by competitors (Barney, Reference Barney1991). As Natura developed continuous interactions with suppliers, the company may have created idiosyncratic knowledge, personal trust, and customized routines, leading to a transaction-specific relational capital (Dyer & Singh, Reference Dyer and Singh1998; McEvily, Perrone, & Zaheer, Reference McEvily, Perrone and Zaheer2003; Mesquita et al., Reference Mesquita, Anand and Brush2008), unavailable to other firms interested in procuring biodiversity products. Given the presence of pressure groups advocating supplier independence and fair-trade principles (such as FASE and Chico Mendes Memorial, discussed before), a new entrant would need to engage in successive and time-consuming interactions to demonstrate its intentions and commitment to supplier development. And because of Natura’s willingness to share rents (in the form of higher prices and community-level investments), suppliers and their cooperatives seemed to prefer interacting with the company vis-à-vis other competitors:

We always work together with Natura, you know, for the longest time, that is our closest partner …, but we also sell a little bit to other firms … but the preference until today is still Natura because Natura’s demand is highest, you know, and the price is also better than those of other firms (anonymized, Amazon Biodiversity Supplier, personal communication).

However, suppliers’ preference for Natura as a buyer is not solely related to the volumes and prices paid. According to the president of an Amazonian grassroots NGO, when asked about his perception of Natura as a buyer:

Natura is different; they were always together, negotiating with the community, saying that this product was for them. Natura was always there for them, so we knew who the recipient was. … there are several other [companies] that we don’t know about. Here, in the case of Juruá, we had a case of Coca-Cola, which launched a product using Açaí and ended up purchasing products not directly. At no point did Coca-Cola discuss commercial conditions with the community. This is very bad, you understand? (anonymized, president of an Amazonian grassroots NGO, personal communication).

In other words, suppliers’ attachment to Natura, although influenced by the company’s willingness to share rents, also seems to derive from a distinct relational approach of the company fostering dialogue and personal interaction. This approach has apparently increased suppliers’ willingness to continue interacting with Natura despite other options. Therefore, nonexclusive relations can become progressively recurring and cospecialized over time, thus creating entry barriers and allowing the company to appropriate rents differently from competitors that may fail to access similar resources. Even in the absence of a formal (exclusive) contract, this has led to a continuing implicit contract with suppliers (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Dmytriyev and Phillips2021).

Although this is essentially an instrumental outcome, four critical issues require additional explanation. First, suppose there are potential long-term gains from establishing open procurement relations. In that case, other firms should also be expected to start similar open strategies and then harness future instrumental gains when exchanges become cospecialized. However, the examination of the presence of corporations in the Amazon revealed that this does not seem to be the case. As seen in the following quotes, companies apparently prefer to buy biodiversity inputs indirectly (via third parties) instead of pursuing direct, personal, relational engagement:

There are companies such as Beraca [a Brazilian company commercializing natural ingredients] that sold to L’Oréal, L’Occitane, and other large cosmetics manufacturers around the world. But it’s known that these companies do not go directly to the Amazon to buy inputs, but rather prefer to deal with local intermediaries for supplies (anonymized, Biodiversity Communities’ Relation Manager, personal communication).

I don’t know any other firm that establishes this kind of relationship at such a high level, you know? This is such a basic thing, but it is very … very difficult to happen, you know? (anonymized, Amazonian NGO President, personal communication).

Second, interviews indicate that barriers to entry may have been reduced over time. More recently, the importance of pressure groups has diminished with the progressive development and dissemination of sustainable practices in the region. For instance, FASE has expanded into other Brazilian states and has diversified its activities to other themes, such as urban inequality and gender disparity. That is, even though Natura’s relations with its ongoing suppliers may have become more cospecialized over time, this does not seem to have prevented other companies from progressively acquiring differentiated inputs from the Amazon rainforest without having to incur substantial supplier development costs. For instance, Beraca Ingredientes Naturais S.A.,Footnote 8 a prominent business-to-business (B2B) player in the natural ingredients industry, has long worked with Natura’s competitors (such as L’Oréal, L’Occitane) and has exported natural ingredients to many countries. Similarly, Germany’s Symrise has supplied fragrances based on those natural ingredients to a broad range of cosmetics firms. Like Natura, both Beraca and Symrise were certified for sustainable and ethical sourcing (e.g., the UEBT certification issued by the nonprofit Union for Ethical BioTrade). In other words, those certifications did not seem to create a strong entry barrier.Footnote 9

Third, if a focal firm starting with open relations ends up with a group of recurring partners providing a bundle of cospecialized resources, that firm should not be expected to keep pushing for open relations in future iterations if its sole emphasis is to generate and sustain economic rents. The firm would simply use its cospecialized relations as a barrier to entry and imitation. Yet, even in this new scenario with new entrants and improved access to biodiversity inputs, Natura continued investing in supplier development and generic infrastructure. For instance, by 2019, Natura funded processing plants in eleven local cooperatives without explicitly requiring the cooperative to sell only to the company.

Even though those infrastructure investments directly benefit Natura (e.g., suppliers are encouraged to diversify their production with biodiversity inputs), they also benefit competitors who might appreciate local suppliers’ expansion. A firm simply trying to expand its own set of recurring suppliers is, therefore, not expected to invite other companies and competitors to tap into similar resources. Conversely, Natura has continuously incentivized the entry of new firms as suppliers of biodiversity inputs. For instance, the company has invested in an “Eco Park” in the State of Pará, Brazil, inviting other companies that also use and benefit from biodiversity products (such as Symrise, mentioned before). Thus, even if Natura’s initial operations in the region may have created unique rents, new entrants could subsequently more easily access local procurement channels:

We arrived here through this partnership, you know; Natura had this operation already in another location … and when [Natura] came to the Eco Park, it invited [firm procuring similar biodiversity inputs] to be part of this supply chain, at an intermediate stage, processing the seeds (anonymized, managers working for an intermediary firm selling to other cosmetics competitors, personal communication).

Finally, and crucially, even if Natura’s strategy was instrumentally devised to harness future rents, the long-term outcomes of the company’s relational approach were far from clear in its initial stages, as the following quotes underscore:

When we began to more strongly approach this supply chain, around 1998 or 1999, we didn’t have an exact understanding of what we would encounter ahead. In fact, it was the first time we moved away from a traditional supply, where there’s a supplier who issues invoices, you can call them, and they have a phone to answer [laughs] (anonymized, cofounder and shareholder, personal communication).

So, we made a heartfelt yet strategic choice and said, “we are going to invest in the sustainable use of Brazilian biodiversity as the basis for the development of the next decade.” And here comes something important: we had to make a decision, and it was our collective decision to invest in the long term. I remember that we used to say: “we don’t know how to do it, there’s no legislation, the legislation,” as [one of the cofounders] mentioned, it was chaotic. I’ve heard more than one Minister of the Environment saying, “you are very courageous, I don’t know how you have managed to do this” (anonymized, cofounder and shareholder, personal communication).

Thus, Natura’s open relational strategy was conceived and implemented when future outcomes and the specific actions to generate those outcomes were largely unknown to its key decision-makers, characterizing a situation of high uncertainty (Dequech, Reference Dequech2011; Packard et al., Reference Packard, Clark and Klein2017). In addition, despite increased entry and competition, Natura remained committed to the open relational model and even encouraged new entrants—which could arguably undermine the strategy’s instrumental outcomes. The study proposes that Natura’s normative core is crucial to understanding and explaining its initial and continuous commitment to the open relational strategy.

THE ROLE AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NORMATIVE CORE IN NATURA’S OPEN RELATIONAL MODEL: KEY FINDINGS

The Normative Core of Natura’s Open Relational Strategy

The final key findings elucidate how Natura conceived and implemented its normative core. Interviews consistently indicate that Natura’s open relational strategy was based on its general objective to develop valuable supplier relations. Still, its distinct long-term commitment was supported by a set of moral principles guiding its engagement with key stakeholders—which is consistent with Freeman’s (Reference Freeman1994) aforementioned notion of the normative core specifying how to govern and manage stakeholder relations. The beliefs and values that guide Natura’s strategy are explicitly stated in a corporate code that still permeates several internal and external communications:

Nothing in the universe exists for itself alone, everything is interdependent. We deeply believe that from perceiving the importance of relationships arises the opportunity for a great human revolution in search of peace, harmony, and the beauty of being. … The firm is a dynamic set of relationships. Its value and continuation are connected to its capacity of contributing to the improvement of society. Firms exist to address the needs of individuals and of the society, through products, services, and actions that contribute to an economic, environmentally sustainable, and more socially equitable development. We believe that its [the firm’s] value broadens proportionally to its capacity to establish quality relationships with consumers, direct sales consultants, employees, suppliers, shareholders, and the entire community, promoting its material, emotional and spiritual improvement (Natura’s statement of “beliefs and values”).Footnote 10

A question, however, is where this code comes from and whether this code is effectively translated into actual organizational practices. In line with the study’s previous theoretical discussion, data also strongly indicate that the origin of the code and Natura’s managerial commitment to its normative principles derive from actors holding critical decision rights, namely its controlling shareholders.

Natura was founded by Antônio Luiz Seabra, who has remained as a controlling shareholder of the company, jointly with Guilherme Leal and Pedro Passos—together, via their own shares and family investment vehicles, they held around 50.4 percent of Natura’s shares as of 2019.Footnote 11 Natura’s self-declared set of beliefs and values rests on the notion of interconnected relationships that, according to Luiz Seabra, emanate from the writings of the ancient philosopher Plotinus and extends to all stakeholders. As a founder and key shareholder, Seabra has publicly stressed principles of managerial action based on philosophical grounds:

Life is a chain of relationships … This concept originates in my youth. When I read Plotinus, one phrase touched me: ‘The one is in the whole, the whole is in the one’. … This phrase inspired my conviction that everything in life is interconnected (Luiz Seabra, cofounder and shareholder).Footnote 12

By emphasizing interconnectedness, this philosophy, now part of Natura’s culture, is very aligned with the overall objective to pursue improved sustainability practices, cooperative engagement with workers and suppliers, and local development in the areas where the company operated—hence the quadruple-bottom line approach that the company established over the years. A controlling shareholder corroborates this view, pointing out that:

In 1992, we wrote it down, it’s there [Natura’s statement of beliefs and values]. … we had this process of two years of revelation, of organizing what we truly believed in. And therein, the elements that defined what was right were actually laid out. It was that systemic vision … you can’t take care of one part if you don’t take care of the whole. A world that melts, a Brazil that melts, an Amazon that melts, you melt too. We’re all in this together (anonymized, cofounder and shareholder, personal communication).

I believe that there is an obsession … of having a balanced posture in the relationship with all stakeholders, with society, and the environment (anonymized, cofounder and shareholder, personal communication).

External partners and competitors also perceive the importance of controlling shareholders in building the company’s normative core. In the words of a manager working for a competitor in the cosmetics industry, when asked why the entire hierarchy responds to the objectives and values of the controlling shareholders:

[Natura] has a king. It is a kingdom that has a king (anonymized, manager working for a Natura’s competitor, personal communication).

Yet one might argue that all these developments may also yield instrumental outcomes: create a positive corporate image and increase profits. Indeed, as discussed in the previous section, the open relational strategy is consistent with Natura’s positioning as a sustainable company, which became particularly relevant as the firm expanded in global markets. Yet several interviewees also indicated that generating economic rents via differentiation is not seen as a single corporate goal, and other objectives specified in Natura’s quadruple bottom line are equally important. In addition, Natura’s generic investments in the supplier communities and its proactive effort to promote superior sustainability standards are actions that do not seem to yield immediate returns and may even require financial sacrifice. In the words of a board member:

I think that in this case [operations] generate lower profitability. The ROE [return on equity] could be higher. … On the other hand, this is for real, it comes from the shareholders, it is part of corporate values (anonymized, member of the board of directors, personal communication).

The data indicate that accepting such financial trade-offs reflected the more balanced preferences of Natura’s shareholders, with objectives beyond profit maximization. As stated by one of the shareholders:

I want to be proud of Natura, not just because it is profitable but because it has social impact, because it is at the vanguard pushing a change in the agenda … being a testing laboratory on its own …. (anonymized, cofounder and shareholder, personal communication).

In sum, the moral philosophical beliefs of the founders crystallized into a normative core, indicating that the company should generate broad stakeholder gains beyond profits and that managers should embrace a wide set of stakeholders beyond existing, recurring partners. Below, the study discusses how the shareholders built their intended normative core throughout the years and progressively specified principles of managerial action.

Building and Leveraging Natura’s Normative Core

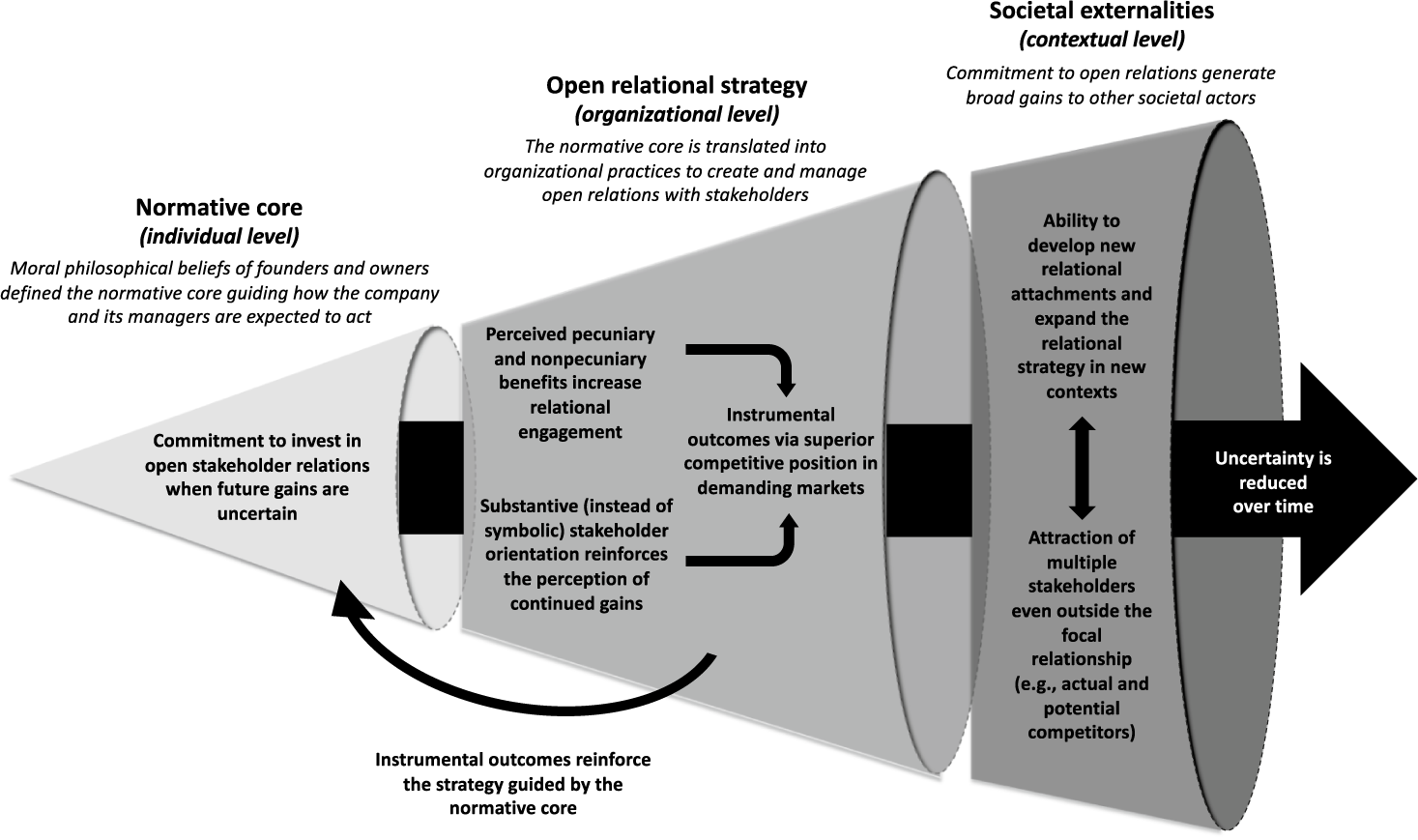

Based on the coding of interviews, Table 2 and Figure 2 describe the sequential steps adopted by Natura’s controlling shareholders and their executives to create a normative core and translate it as a supporting element of the open relational strategy. Inspired by Islam (Reference Islam2020), the study differentiates between individual, organizational, and contextual processes. The initial conception of the moral core began from the individual action and mindset of controlling shareholders, later being implemented via relationships occurring at the external and internal organizational levels, and finally diffused in the context where Natura operates (initially, in the Amazon region and their relevant stakeholders, and more recently worldwide).

Table 2: Building and Leveraging Natura’s Normative Core

Figure 2: Building and Leveraging a Normative Core Supporting Natura’s Open Relational Strategy

Individual Level

As documented before, the initial stage involved the central participation of controlling shareholders, defining initial beliefs and values, and guiding the company’s operations. The normative core was initially proposed by founder Antônio Luiz Seabra circa 1969, later reinforced with the attraction of Guilherme Leal and Pedro Passos, completing the trio of controlling shareholders (see item 1, “Controlling shareholders’ values and beliefs in the interconnectedness of relationships [1969–1990]” in Table 2 and Figure 2). A central element of their beliefs has been the notion of interconnectedness, which is also a defining element of corporate sustainability (Bansal & Song, Reference Bansal and Song2017), and thus establishes sustainability early on as a core element of Natura’s strategy:

Seeing life as an enchainment of relationships prepares us for thinking and feeling in an integrated manner, which is the origin of my beliefs and the reason for the existence of Natura. Footnote 13

Organizational Level

A crucial part of this process, documented in the previous section, is the creation of an explicit set of beliefs and values in the early 1990s, which became a salient and formalized manifestation of the normative (moral) core (see item 2, “Making values and beliefs explicit [1990–1992]” in Table 2 and Figure 2). These values were meant to stay—as two of the founders and controlling shareholders underscored many years later, responding to a journalist’s question of why they shared the chairman of the board position after several years of absence: “when there is a relevant shareholder present, this is very good to maintain certain values strong in the firm.”Footnote 14

A critical aspect indicating how the company should be governed was the adoption of broad socio-environmental goals, as evidenced by the aforementioned quadruple bottom line. The company has made the quadruple bottom line an integral part of its business strategy with ramifications for functional areas ranging from human resources and marketing to its supply chain. These internal developments, which then specified how organizational members should act, roughly occurred between 1993 and 1998 (see item 3, “Alignment of goals and processes consistent with the relational strategy [1993–1998]” in Table 2 and Figure 2).

Natura has achieved this internal alignment by developing and tracking related socio-environmental indicators, which it uses in diverse areas ranging from product development to its compensation and incentive policy. These goals permeated the whole organization and reinforced its strategy among consumers, employees, and suppliers, including those in the Amazon region. They were also tied with managerial evaluation and incentives; for instance, financial bonuses require meeting minimal targets on all socio-environmental performance dimensions. In 2011, despite sizeable profits, executives did not receive part of their variable compensation (linked to these profits) because they failed to meet some socio-environmental targets (Sendin, Reference Sendin2013). As put by a top executive:

They earned no bonus, it is as simple as that. No bonus was paid because they did not achieve their environmental goals. A company that manages a business like this, I believe, sends the clearest message of the importance that this matter has for the organization (anonymized, Vice President of Sustainability and Institutional Affairs, personal communication).

Pursuing those aligned goals, the company then started implementing the open relational business model in the Amazon in the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s (see item 4, “Implementation of the relational business model [1998–2000s]” in Table 2 and Figure 2). Positions relevant to the implementation of Natura’s open relational strategy—such as members of the stakeholder relations team at the Amazon region and headquarters executives dealing with community relationships up to the vice presidency of sustainability—have been filled with former NGO representatives and managers with previous experience in sustainable practices. As mentioned before, Natura eventually recruited personnel from FASE, which had a suspicious view of corporations operating in the region, and attracted technical personnel with sustainability and community relations backgrounds. Such an approach facilitated cocreating sustainable supply chain relationships through dialogue with a broad group of stakeholders—a way of translating the controlling shareholders’ philosophy of life being a chain of relationships and their belief that life manifests itself through diversity into practice.

There were also informal efforts to indicate a preoccupation with the execution and the local implementation of the normative core. Illustrating the presence and influence of controlling shareholders in the individual lives of Natura’s managers, some interviewees noted that Luiz Seabra has annually called all managers to congratulate them on their birthdays. Over time, with these actions, the company managed to internalize organizational values that appeared to be highly oriented towards the well-being of supplier communities and their natural environment. The interviews with Natura employees and supplier community representatives reflect how the controllers’ preferences have trickled down to supply chain managers:

The human factor is in the very relationship, in the day by day [of our operations] … the engagement process with a very strong human relationship, very present …. When going to the field, you end up going to these regions that do not have a hotel, you get involved with a community …. [Our] team ends up being an advocate of its suppliers of biodiversity (anonymized, director of Benevides Industrial Plant, personal communication).

Contextual Level

Since 2010, Natura has generated broad societal externalities with the “Expansion and diffusion of the model in multiple localities and attraction of new entrants (2010s and on)” (see item 5 in Table 2 and Figure 2). Natura’s expansion of open relational practices within the Brazilian Amazon region (see Figure 1) has produced a measurable impact well beyond Natura’s supply operations. A recent study using satellite data for a quasi-experimental estimation strategy has shown that from 2000 to 2018, municipalities within the Amazon region where Natura decided to establish a supply chain have preserved almost 50 percent more forested areas than locations in which Natura does not operate (McGahan & Pongeluppe, Reference McGahan and Pongeluppe2023). Moreover, the firm expanded its model to Amazon regions in neighboring countries, such as Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru. The study thus argues that the open relational model has generated societal externalities in a way that is consistent with the encompassing nature of the normative core, emphasizing stakeholder interconnectedness and broad societal gains.

Beyond the Amazon region, Natura is diffusing and spreading its principles industry-wide. The firm has contributed to creating a global standard and certification for ethical sourcing endorsed by the United Nations (UEBT, previously mentioned). And, since the acquisition of Australia-based Aesop, critical features of Natura’s open relational practices, such as benefit sharing with supplier communities, have been reproduced in the Australian context in aboriginal communities that provide sandalwood oil from Australia’s outback. The local and global diffusion processes demonstrate positive externalities beyond the firm’s core operations (Lazzarini, Reference Lazzarini2020; Mahoney & Qian, Reference Mahoney and Qian2013; Santos, Reference Santos2012). The more recent global expansion and diffusion are aligned with and arguably seem to be supported by the company’s normative core:

With the acquisitions of Avon, Body Shop, and Aesop … what motivated us was the perception of the positive impact that we could have … by this vision of cooperation, not competition, by this vision of interdependence, by this vision of shared prosperity. … We believe that the firm is an instrument of transformation, that life is a network of relationships … We believe that we can have an important positive large-scale impact, and that we can be successful in business with this and help transform business culture… (anonymized, cofounder and shareholder, personal communication).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The Entangled Instrumental and Normative Stakeholder Views

This section offers a consolidated discussion proposing how instrumental and normative arguments are deeply intertwined and can jointly explain stakeholder-oriented relational strategies building on previously reported empirical findings (see Figure 3, which conceptually expands Figure 2 to depict the interplay between the instrumental and normative mechanisms). A crucial determinant of those strategies is the presence of a solid normative core defined by those who hold critical decision rights on broad corporate strategies. Drawing from Freeman’s (Reference Freeman1994) conceptualization of the normative core, the open relational model departs from the normative directive that companies should be governed to balance complex (and potentially conflicting) stakeholder claims, while managers should manage broad, interdependent relationships between the firm and its key stakeholders. Those principles of action can be derived from the preferences of individuals holding critical decision rights, such as shareholders or their representatives (Hart & Zingales, Reference Hart and Zingales2017; Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Mackey and Barney2007).

Figure 3: Interplay between Normative and Instrumental Mechanims

The normative core, in turn, generates principles of action supporting strong organizational commitment to implement open relational strategies, both internally (managers implementing those strategies) and externally (partners, advocacy groups, and supporting organizations). Increased commitment is expressed, for instance, by the company’s willingness to accept financial trade-offs (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2019, Reference Kaplan2020; Rangan, Reference Rangan and Rangan2018): invest in stakeholder welfare even if this benefits other players and entrants, and at a moment where the future instrumental outcomes of such open relational strategies are largely uncertain. This costly commitment at uncertain times signals the firm’s genuine commitment to its stakeholders (Clark, Kofford, Jones Christensen, & Barney, Reference Clark, Kofford, Jones Christensen and Barney2024). Namely, the firm allocates critical resources to build open relations with a broad set of players (beyond recurring exchanges) and invites other players, including competitors, to be part of the open strategy.

Importantly, as seen in Figure 3, while the normative core can put the open relational strategy in motion under highly uncertain conditions, the emergent instrumental outcomes can subsequently help reinforce the strategy supported by the normative core (illustrated by the white arrow feeding back from instrumental outcomes to the normative commitment to open stakeholder relations). In other words, there is a mutual, two-way interplay between the instrumental and normative mechanisms.