Response

By 2050, two-thirds of the global older adult population could reside in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs), also home to an estimated 71% of the world’s dementia cases. Reference Tan1 This paper is a commentary on the published Indonesian dementia prevalence estimates developed using the Strengthening Responses to Dementia in Developing Countries (STRiDE) methodologies. Reference Farina, Jacobs, Turana, Fitri, Schneider and Theresia2

The lack of national data for dementia prevalence in many LMICs means that estimates must rely on regional statistical modelling, less powerful than using local data. Reference Farina, Jacobs, Turana, Fitri, Schneider and Theresia2 Current dementia prevalence estimates in Indonesia are >20% for the over-60s: two to three times higher than that of most countries included in the 2015 estimates from the World Alzheimer’s Report, e.g. Europe and the USA, with estimates between 4 and 9% for those aged over 60 years. Reference Prince, Wimo, Guerchet, Ali, Wu and Prina3–Reference Suriastini, Turana, Supraptilah, Wicaksono and Mulyanto5 STRiDE methodologies were used to estimate dementia prevalence in Indonesia. Reference Farina, Jacobs, Turana, Fitri, Schneider and Theresia2 Recruitment of 2216 older people occurred in rural and urban Jakarta and North Sumatra, and who were assessed using the screening instruments 10/66 Short Dementia Diagnostic Schedule, Dementia Severity Rating Scale and Lawton Activities of Daily Living Scale. Nationwide estimates for dementia prevalence in this cohort were 27.9% in the over-60s, but only five individuals had a formal dementia diagnosis. These estimates are consistent with other Indonesian dementia prevalence estimates, ranging from 20 to 33%. Reference Ong, Annisafitrie, Purnamasari, Calista, Sagita and Sofiatin4–Reference Handajani, Hogervorst, Schröder-Butterfill, Turana and Hengky6

A possible explanation for these high Indonesian dementia prevalence estimates could be that the diagnostic instruments used were too sensitive. Earlier research in 2006 showed lower estimated dementia prevalence in Indonesia (between 6 and 8%), which was similar to that in European countries using slightly different, perhaps more culturally adapted, dementia screening tests. Reference Hogervorst, Rahardjo and Bandelow7 The 10/66 instruments were applied in other LMICs and were reported to have good sensitivity for dementia. Reference Prina, Mayston, Wu and Prince8 The prevalence in South Africa using these instruments was 12.5% in those aged over 60 years, Reference Farina, Jacobs, Turana, Fitri, Schneider and Theresia2 almost double that in most Western countries and in our earlier Indonesian estimates.

In the STRiDE Indonesian study, men were less likely to have dementia, with an estimated prevalence of 21%, compared with women with 31%, and they were 2.5 times more likely to be literate, Reference Farina, Jacobs, Turana, Fitri, Schneider and Theresia2 a protective factor for dementia. In our earlier study, Reference Hogervorst, Rahardjo and Bandelow7 dementia risk was double in rural areas, explained by education, poor health and, independently, older age. Gender was not a significant factor in these analyses, possibly because it was very closely associated with having had little education. Reference Hogervorst, Rahardjo and Bandelow7,Reference Hogervorst, Schröder-Butterfill, Handajani, Kreager and Rahardjo9 Our earlier study showed the highest dementia estimates (16–21%) in Borobudur, a rural Javanese district, similar to the 2020 published estimates in that region for the over-60s (20%). Reference Suriastini, Turana, Supraptilah, Wicaksono and Mulyanto5,Reference Hogervorst, Rahardjo and Bandelow7 This district had the oldest, but also poorest, population of those studied, who had little access to medical facilities and many without formal education.

While education affects cognitive reserve, Reference Stern, Arenaza-Urquijo, Bartrés-Faz, Belleville, Cantilon and Chetelat10 it is also associated with reading, Reference Chang, Wu and Hsiung11 both shown to reduce dementia risk. Reference Hogervorst, Schröder-Butterfill, Handajani, Kreager and Rahardjo9 According to national data, older Indonesian women were found to have lower education and engaged less in reading than older men. Reference Arifin, Braun and Hogervorst12 This lack of formal education could be associated with the delegation of roles within households and cultural attitudes towards girls. Lack of education, especially among older women in rural areas, could also cause difficulty in accurate dementia testing. Illiterate or poorly educated people may not be accustomed to formal examination environments, and anxiety surrounding their performance could affect the validity and reliability of cognitive assessments. The specificity of the 10/66 instrument was not reported, and could have been affected by such false positives. Reference Farina, Jacobs, Turana, Fitri, Schneider and Theresia2

Many cognitive tests have been developed for Western, literate participants and must be cross-culturally adapted for LMICs, which may not have been carried out sufficiently. Reference Farina, Jacobs, Turana, Fitri, Schneider and Theresia2,Reference Hogervorst, Rahardjo and Bandelow7 Farina et al suggested that the 10/66 Short Schedule was education fair, but their false-positive rate was 5.5%; perhaps rather than dementia, the algorithm detected mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In our previous studies, the culturally modified Mini-Mental Status Examination (mMMSE) and the modified Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (mHVLT) both showed good dementia and MCI sensitivity and specificity in both UK and Indonesian cohorts. Reference Hogervorst, Rahardjo and Bandelow7,Reference Hogervorst, Combrinck, Lapuerta, Rue, Swales and Budge13 The mHVLT had dementia cut-off scores similar to the UK sample and mMMSE had high sensitivity (100%), also with a similar cut-off. For better specificity, the mMMSE needed a lower cut-off score and was modified by education, unlike the mHVLT.

Despite these issues, modifiable risk factors for dementia and MCI are similar in both high-income countries (HICs) and LMICs. Reference Mukadam, Sommerlad, Huntley and Livingston14,Reference Livingston, Huntley, Sommerlad, Ames, Ballard and Banerjee15 In earlier studies investigating dementia risk in Indonesia, Reference Ong, Annisafitrie, Purnamasari, Calista, Sagita and Sofiatin4 risk reduction was associated with engagement in psychosocial activities such as physical activity and attending community activities. Reference Hogervorst, Schröder-Butterfill, Handajani, Kreager and Rahardjo9 In urban Jakarta (but not in the rural cohorts), higher engagement in sports, better diets and frequent reading were associated with lower dementia risk, Reference Hogervorst, Schröder-Butterfill, Handajani, Kreager and Rahardjo9 suggesting engagement in multiple, available protective activities. Nevertheless, for both urban and rural areas, attending community activities was associated with lower dementia risk, Reference Hogervorst, Schröder-Butterfill, Handajani, Kreager and Rahardjo9 consistent with other Indonesian analyses. Reference Ong, Annisafitrie, Purnamasari, Calista, Sagita and Sofiatin4,Reference Juniarti, Aladawiyah Mz, Sari and Haroen16 In STRiDE, only smoking was assessed as a lifestyle factor and was associated with increased dementia risk. Reference Fitri, Farina, Turana, Theresia, Sani and Ika17

Health-related dementia risk factors are the same in both HICs and LMICs, such as stroke and diabetes. Reference Suriastini, Turana, Supraptilah, Wicaksono and Mulyanto5,Reference Setyopranoto, Bayuangga, Panggabean, Alifaningdyah, Lazuardi and Dewi18,Reference Gong, Harris, Peters and Woodward20 These preventable morbidities (through medication, diet and exercise) and their high prevalence in Indonesia could also partly explain the high dementia prevalence. In our earlier study, Reference Hogervorst, Rahardjo and Bandelow7 the prevalence of these morbidities was lower but people may have also died before developing dementia. With a lack of specialist medical care in rural areas, such illnesses can go untreated or undetected. Reverse causality could also play a role, whereby individuals are potentially forgetting to seek medical treatment because of cognitive decline.

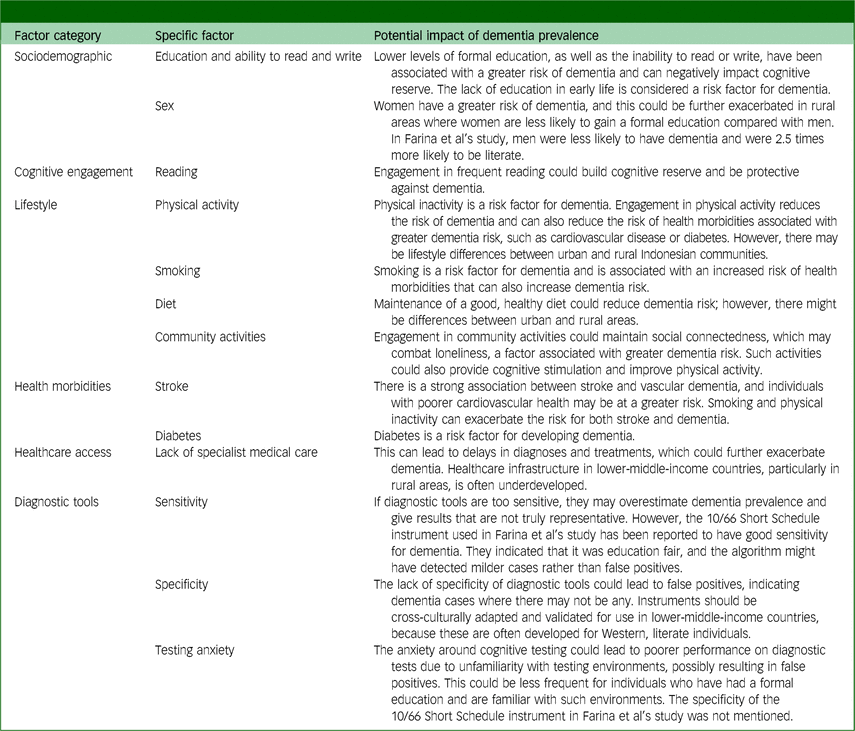

Modifiable factors, such as education, psychosocial activities and preventable or treatable morbidities, are involved in the compression of dementia risk, as demonstrated in the Compression of Needs model. Reference Hogervorst, Schröder-Butterfill, Handajani, Kreager and Rahardjo9 This model suggests that good physical/material resources (e.g. healthy lifestyle, access to good healthcare and physical activity) and psychosocial resources (e.g. good educational attainment, continued education and skill development, social engagement and technology use), as well as supportive public health policies, can compress and reduce the likelihood of risk factors associated with dementia health morbidities that increase dementia risk (e.g. stroke, diabetes and cardiovascular disease). This model underpins prevention, allowing individuals to address risk and enact change to reduce this risk (Table 1).

Table 1 Factors explaining the high dementia prevalence in Indonesia

Overall, Farina et al have contributed to increasing evidence suggesting Indonesian dementia estimates of approximately 20% in older adult populations. Possible explanations for these high estimates thus lie in (a) the challenges in ethnic or cultural differences in adapting cognitive assessments to LMICs, (b) a lack of exposure to previous examinations and testing, (c) issues with specificity and false positives possibly related to inadequately adapted cognitive tests and (d) the role of a greater magnitude of potentially preventable risk and protective factors, such as the lack of available psychosocial engagement, education, stroke and diabetes (Table 1). There may also be contributions to dementia risk from non-assessed communicable (infectious) diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis, which are still important factors in LMICs.

With the increasing migration of young people to urban areas, alternative care and prevention for dementia in vulnerable older people become more important. With many risk factors and few medical specialists, dementia in LMICs is perhaps not treated or prevented well. Such issues need to be addressed at policy levels, given that future estimates predict that the fastest increasing dementia rates will be from LMICs.

Author contribution

Both authors contributed equally to the final manuscript.

Funding

M.J.’s PhD studentship is funded by the Dunhill Medical Trust and Loughborough University.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.